Summary

Background

The prevention of sexual violence (SV) occurring shortly after arrival in host countries towards female asylum seekers requires knowledge about its incidence. We aimed to determine the incidence of SV and its associated factors during the past year of living in France among asylum-seeking females who had arrived more than one year earlier but less than two years.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using a life-event survey of asylum-seeking females who had been registered in southern France by the Office for Immigration for more than one year but less than two. The primary outcome was the occurrence of SV during the past year, weighted by the deviation in age and geographical origin of our sample from all females registered. The nature of SV was noted, and associated factors were explored by a logistic regression model.

Findings

Between October 1, 2021, and March 31, 2022, 273 females were included. Eighty-four females experienced SV during the past year of living in France (26.3% weighted [95% CI, 24–28.8]), 17 of whom were raped (4.8% weighted [95% CI, 3.7–6.1]). Being a victim of SV prior to arrival in France (202, 75.7%) was associated with the occurrence of SV after arrival (OR = 4.6 [95% CI, 1.8–11.3]). Lack of support for accommodation was associated with se.xual assault (OR = 2.6 [95% CI, 1.3–5.1]).

Interpretation

The months following arrival in a European host country among asylum-seeking females appear to be a period of high incidence of SV; even higher for those who previously experienced SV prior to arrival. Reception conditions without support for accommodation seem to increase exposure to sexual assault.

Funding

DGOS-GIRCI.

Keywords: Sexual violence, Asylum seekers, Europe, Incidence

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

In December 2020, we searched the Science Direct and PubMed databases for articles on sexual violence experienced by female asylum seekers (AS) in their host countries using the terms “sexual violence,” “rape,” “sex offenses,” “violence,” “migration,” “female asylum seekers,” and “refugees”. These databases contain since 2012 results concerning the past year incidence of sexual violence among female asylum seekers (AS), but the sample sizes are either small or limited to asylum seekers included in asylum reception facilities. Additionally, the designs do not describe the total number of female AS living in the study area during the study period, so the proportions presented are based on an undescribed target population size. Qualitative studies conducted to investigate similar populations in Europe have suggested that the months following arrival in the host country represent a period of exposure to SV. Ultimately, the ANRS-Parcours study conducted in France and published in 2018 revealed a prevalence of forced sex postmigration ranging from 4% for females without HIV to 15% for females who acquired HIV after migration. However, this study did not specify the level of risk or the incidence of SV shortly after arrival in the host country. Moreover, the population studied was restricted to sub-Saharan African migrant females, not necessarily asylum seekers, who visited healthcare facilities, although the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends distinguishing among the different legal statuses of migrants when designing research programmes. All previous studies agree with the WHO that stopping sexual violence requires a public health approach with the expansion of the knowledge base and dissemination of existing information to improve programmes and strategies.

Added value of this study

Our study provides an estimate of SV incidence during the past year of living in France exclusively among asylum-seeking females who have recently arrived in that country without restriction to those who are living in asylum reception facilities. SV occurred for 84 women (26.3% weighted [95% CI, 24–28.8]); 17 of whom were raped (4.8% weighted [95% CI, 3.7–6.1]). Having experienced SV prior to arrival in France and not having a couple partner in France were associated with the occurrence of SV and rape after arrival, respectively. Females from West Africa were subjected to attempted rape more frequently than females from other geographic origins. Concerning the living conditions in the host country, we found an association between the lack of a support system that provides accommodations and sexual assault (OR = 2.6 [95% CI, 1.3–5.1]).

Implications of all the available evidence

Female asylum seekers are overexposed to sexual violence in their countries of origin, and the prevention of this violence in their host countries is a public health issue. The months following their arrival in a European host country seem to be a period of high exposure to SV with a notable role of reception conditions. Compared to data drawn from the extant literature, our findings indicate that female AS are exposed to SV more frequently than the general population of French women. Our findings provide valuable information for making public policies to prevent the occurrence of SV among asylum-seeking females in European host countries and to detect them if they could not be prevented.

Introduction

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimated that in 2020, over 82 million people worldwide were forcibly displaced and that women constituted 47% of this population.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) maintains that the heterogeneity of these displaced persons in terms of legal status (asylum seeker, refugee) must be considered to improve knowledge of the health of these individuals.2 In this context, asylum seekers (AS) are displaced persons who have recently arrived in their host country and whose administrative situation is under examination. In 2021, in Europe, there were 535,000 first time asylum applicants, of whom nearly 31% were females.3 In France, 18.768 females over the age of 18 years filed their first asylum application in 2021.4

This population faces several issues. The prevention of sexual violence (SV) towards asylum-seeking females and the need to care for victims have been prioritized by the UNHCR,5 particularly because of the morbidities induced by this phenomenon.6, 7, 8, 9 The WHO also reported that females undergoing forced displacement to escape war or persecutions are particularly vulnerable to SV2 shortly after their arrival in their host country to an extent that has not yet been described in the literature.

A study conducted in the United States and published in 2020 revealed the lifetime prevalence of SV among AS to be 88.2% and the prevalence of rape to be 50.3%.10 However, this study did not provide any information concerning the proportion of asylum-seeking females who experienced SV after they arrived in their host country. The first European data on post-arrival sexual violence against asylum-seeking females were published in 2012. It was reported that, among events of violence involving a population of refugees, undocumented migrants or AS, 40.4% of the reported cases of SV concerned AS both sexes. This study highlighted the vulnerability of female AS to sexual violence after arrival in the host country, which should be studied in more specific research.11 One Greek study conducted in 2020, limited to asylum-seeking females who had experienced SV, found that 5% of this population experienced violence in the host country.12 This study, which limited its population to victims of SV, did not provide data concerning the prevalence of post arrival SV among asylum-seeking females. A French study conducted in 2018 revealed that the prevalence of forced sex after migration varied from 4% to 15% depending on whether HIV was contracted after migration.13 This study showed an association between a lack of stable housing and forced sex. However, this study did not specify the level of risk or the incidence of SV early after arrival in the host country. Moreover, these findings focused exclusively on the population of sub-Saharan African women migrants, not necessarily asylum seekers, consulting in healthcare facilities. A Belgian study reported in 2022 that 61.3% of AS of all sexes living in Belgium had experienced SV during the past year; most of them since their arrival.14 The SV-related events reported in this study did not necessarily occur in the host country. Additionally, these results were based from a randomly selected sample of only 15 females among 62 AS and all were recruited from reception structures responsible for organizing the reception facilities for AS. Regarding the factors associated with the SV experienced by refugees, AS and migrants living in European asylum reception facilities (EARF), one study conducted in 2014 focused mainly on accommodations and living conditions.15 This study revealed a past-year incidence of SV of 37.8% among females. However, only 60.3% of the sample of this study had AS status, and it was restricted to individuals living in EARF. A United Kingdom survey published in 2009 that was limited to unaccompanied asylum-seeking minors who were sexually abused in the UK, revealed that three-quarters of SV events occurred within the first 12 months after arrival in the host country.16 Because this study was restricted to victims of SV, rather than to female AS specifically, it did not provide information regarding the incidence and level of risk of post-arrival SV among female AS.

Preventing SV towards asylum-seeking females in host countries requires knowledge of its incidence and the factors associated with such violence. Existing studies in the literature17,18 agree with the WHO on the need to expand the knowledge base about post-arrival SV and disseminate existing information to improve programmes and strategies.19

The main objective of our study was to assess, during the past year of living in France, the incidence proportion of SV experienced by asylum-seeking females who had arrived less than two years earlier and who were not necessarily living in a asylum system facilities. The secondary objectives of this study were to clarify the nature and circumstances of the SV suffered by these females and explore the links between SV and the potential explanatory factor.

The period of the past year was chosen so that the incidence proportions could be compared with similar studies in the literature that have studied the past-year incidence of SV. The limit of 2 years of presence was chosen specifically to study the first months of life in the host country and limit memory bias. Conversely, the sample was not restricted to asylum-seeking females with strictly one year of presence to provide a large sample with a better level of evidence in this “hard to reach”14 population.

Methods

Study design and participants

For 6 months, we conducted a retrospective questionnaire-based cohort study among asylum-seeking females of SV that occurred during the past year of living in France. The source population included females registered by the prefecture of one of the twelve French regions (the southern region) when they applied for asylum. This file was held by the French Office of Immigration and Integration (OFII), a partner in the study, which organises the reception of asylum seekers in France.20 We did not restrict our source population to women who consulted a care centre or lived in asylum-seeker reception facilities to limit selection bias. Upon their arrival in France, females over the age of 18 years who had a registered application for asylum in France for more than one year and less than two years, and who were recorded in the administrative region of southern France were eligible. The gender classification was identified by OFII at the time of their registration (female at birth).

Trained female interviewers called (3 times at most) eligible females to present the study and propose an appointment at one of the partner hospitals. It was explained that this survey was designed to study the living conditions of asylum seekers in their host country and their possible exposure to sexual violence. Participants were reimbursed for their travel expenses. If an asylum-seeking female wanted to participate in the study but did not wish to travel, a telephone interview was offered instead. In case of a telephone interview, they had to take place with the participant concerned directly and only, who had to be in a confidential place. The investigators had access to professional telephone interpreters to ensure the delivery of clear and appropriate information and to collect appropriate consent and reliable data. These professional interpreters were experienced in interviewing AS and worked with most medico-social establishments catering to AS in the southern region of France. All females who were contacted were offered health care according to the WHO and UNHCR recommendations for dealing with SV among this population from experienced primary care services close to where they lived and participants who wished to were offered protective measures in collaboration with OFII.

This study was approved by one of the French Research Ethics committees under the authority of the Ministry of Research on 18 June, 2021 (approval number 21.04.02.59049) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05007431). All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki in terms of ethical aspects, information, and the consent of subjects with regard to participation and data publication. The study protocol applied the WHO (Ellsberg and Heise 2005) and UNHCR (UNHCR 2003) ethical and safety guidelines in researching violence. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Data collection

A questionnaire was administered face-to-face or by phone, when appropriate. The professional interviewers were experienced and trained in research on SV. This questionnaire covered the following sociodemographic data: age, dependent children, couple relationship with a partner in France at the time of the survey, geographical origin (West Africa, Maghreb, rest of Africa, Europe, South America, Middle East, or Asia), level of education (never attended school, below, equivalent to or above high school), income source (none, legal or undeclared work, state aid, or other aid) and accommodation during most of the past year. Females who did not have a single dwelling with a legal lease were classified and we used the European Typology of Homelessness and Housing Exclusion (ETHOS)21: Emergency housing support (ETHOS 2 or 3), National Asylum Support System22 (ETHOS 5) and lack of support system (ETHOS 1 or 8). The identification of threatening or resourceful people and the use of care during the past year were also collected. Four questions focused on the occurrence of sexual exhibitions, sexual assault, rape and attempted rape during the past year. Anyone who answered yes to one of these four questions was considered a victim of SV during the past year (primary outcome). To limit ranking bias, we used the same definitions and phrases to classify SV as those already used to measure SV in the French general population.23 This categorization is described in supplementary material. In the case of reported violence, details of the circumstances (location, number of events, perpetrator, help sought) were collected. To identify other risky situations, occurrences of enduring blackmail (with regard to food, housing, clothing, etc.) in exchange for sexual favours or instances of prostitution were also collected. We considered living in the host country the exposure factor. The exposure period studied was the past year and all recorded new events occurred in France because all included females had been present in France for at least one year. Whether the participants had suffered SV before their arrival in France, most notably rape or female genital mutilation, was noted.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were expressed in terms of means with standard deviation, and categorical variables were reported in terms of counts and percentages. Both types of these variables were expressed with 95% confidence intervals (CI); thus, the corresponding figures for all AS living in France could be estimated from the results. Incidence proportions were expressed with 95% CI. Weighted incidence proportions were calculated to consider age and geographical deviation from the overall source population (OFII file). Comparisons of mean values between these two groups were performed using Student’s t test or the Mann‒Whitney U test. Comparisons of percentages were performed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate for the situation at hand. ‘Sexual exhibition', ‘sexual assault', ‘rape', ‘attempted rape', ‘rape or attempted rape', ‘blackmail', ‘prostitution', ‘female genital mutilation', ‘SV before arrival in France' and ‘rape before arrival in France' were all secondary outcomes and were considered in univariate/multivariate analysis. Multivariate analyses were conducted using multiple logistic regression. The logistic model for post arrival SV included variables described a priori in the literature as risk factors for sexual violence15,23,24 (prior victimization, level of education, accommodation status, and low socioeconomic status) as well as all variables that were significant (p < 0.05) a posteriori in the univariate analysis for at least one of the outcomes. This same model was used for each of the outcomes concerning post arrival SV. The prearrival SV univariate analysis focused only on sociodemographic variables related to the country of origin, i.e., geographical origin and education level. The other sociodemographic variables that were related to sociodemographic characteristics in France were excluded. The logistic model for prearrival violence included these two variables. Calibration of the logistic model was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test to evaluate the discrepancy between the observed and expected values. Odds ratios were expressed with 95% confidence intervals. All the tests were two-sided, with statistical significance defined as p < 0.05.

Role of the funding source

The study received funding from the Ministry of Health in the amount of 50,000 Euros, which was used to cover the costs of professional interpreters, human resources for data collection, and translation costs. The budget was collected and managed by the public research department of the public assistance hospitals of Marseille.

Results

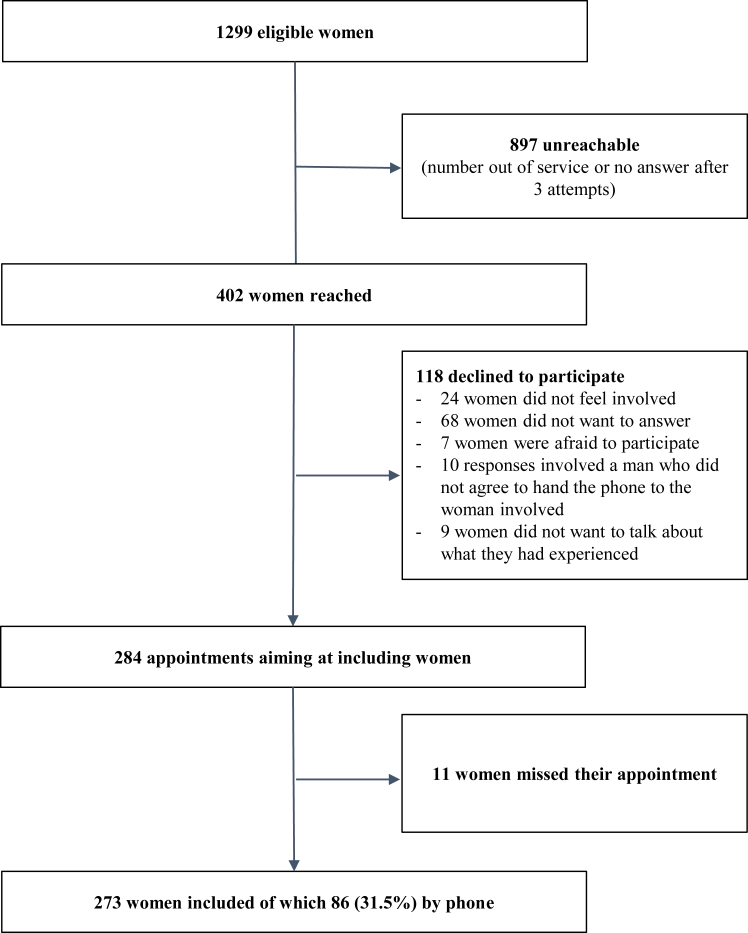

Between 1 October 2021 and 31 March 2022, 1299 females from the OFII file were identified as eligible for participation n in this study. A total of 897 (69.1%) of these females were unreachable, 118 (9.1%) declined to participate, and 11 (0.8%) missed the inclusion appointment. Two hundred seventy-three (21%) females were ultimately included in the study (Fig. 1). Eighty-six interviews (31.5%) were conducted by phone. Sociodemographic characteristics and sexual violence history prior to arrival in France are reported in Table 1. Almost half of the participants were between 26 and 35 years old (131, 48%), from West Africa (153/272, 56.3%), in a couple relationship with a partner present in France (154/273, 56.4%) and receiving state financial (151/269, 56.1%) or accommodation asylum aid (153/270, 56.7%). In the OFII file, the proportions of females from West Africa (409/1299, 31.5%; lower proportion), Europe (440/1299, 33.9%; higher proportion) and the Middle East (180/1299, 13.9%; higher proportion) varied significantly from those found in our sample. The 18- to 25-year-old age group in our sample (67/273, 24.5%) represented a significantly smaller proportion than in the population of all eligible females (413/1299, 31.8%), while the 26–to-35-year-old age group was more represented (132/273, 48.4% vs. 461/1299, 35.5% for all eligible females). The weighted proportions take into account these deviations.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics and sexual violence history prior to arrival in France.

| Na | n (%) | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 273 | ||

| 18- to 25-year-old | 66 (24.2%) | (19.5–29.6) | |

| 26- to 35-year-old | 131 (48%) | (42.1–53.9) | |

| 36- to 45-year-old | 48 (17.6%) | (13.5–22.5) | |

| >46-year-old | 28 (10.3%) | (7.2–14.4) | |

| Number of dependent children | 271 | ||

| 0 | 44 (16.2%) | (12.3–21.1) | |

| 1 | 81 (29.9%) | (24.8–35.6) | |

| >1 | 146 (53.9%) | (47.9–59.7) | |

| Geographical origin | 272 | ||

| West Africa | 153 (56.3%) | (50.1–61.8) | |

| Maghreb | 15 (5.5%) | (3.4–8.9) | |

| Rest of Africa | 26 (9.6%) | (6.6–13.6) | |

| South America | 16 (5.9%) | (3.6–9.3) | |

| Middle East | 20 (7.4%) | (4.8–11.1) | |

| Europe | 25 (9.2%) | (6.3–13.2) | |

| Asia | 17 (6.3%) | (3.9–9.8) | |

| Couple relationship with partner present in France | 273 | ||

| Yes | 154 (56.4%) | (50.5–62.2) | |

| No | 119 (43.6%) | (37.7–49.7) | |

| Accommodation most of the time during the past year | 270 | ||

| Lack of a support system | 75 (27.8%) | (22.8–33.4) | |

| Single dwelling with legal lease | 22 (8.1%) | (5.4–12.0) | |

| National Asylum Support System | 153 (56.7%) | (50.7–62.5) | |

| Emergency housing support | 20 (7.4%) | (4.9–11.2) | |

| Level of education | 269 | ||

| Never been to school | 60 (22.3%) | (17.7–27.6) | |

| Less than high school | 52 (19.3%) | (15.1–24.5) | |

| High school | 71 (26.4%) | (21.5–32.0) | |

| More than high school | 86 (32.0%) | (26.7–37.8) | |

| Financial resources | 269 | ||

| State financial aid | 151 (56.1%) | (50.5–61.9) | |

| None | 21 (7.8%) | (5.2–11.9) | |

| Undeclared work | 39 (14.5%) | (10.8–19.2) | |

| Family, friend or associate support | 35 (13.0%) | (9.5–17.6) | |

| Work with legal contract | 23 (8.6%) | (5.8–12.5) | |

| Any type of sexual violence prior to arrival in France | 267 | ||

| Yes | 202 (75.7%) | (70.2–80.4) | |

| No | 65 (24.3%) | (19.6–29.8) | |

| Rape prior to arrival in France | 203b | ||

| Yes | 139 (68.5%) | (61.8–74.5) | |

| No | 64 (31.5%) | (25.5–38.2) | |

| Female genital mutilation prior to arrival in France | 199b | ||

| Yes | 80 (40.2%) | (33.6–47.1) | |

| No | 119 (59.8%) | (52.9–66.4) |

Data are n (%) or mean (SD).

N: number of data available after excluding missing data.

The approval of the ethics committee for the collection of these 2 variables was specifically given after the start of the first evaluations, which explains the high number of missing data. 95% CI corresponding figures for all AS living in France.

In our sample, 75.7% (202/267) of females had experienced SV prior to arrival in France, 139 of whom had been raped (68.5% of a sample of 203 females after excluding missing data for rape). Regarding female genital mutilation, 40.2% (80/199) had suffered from this violence; all of whom were from Africa. Therefore, 56.3% (80/142) of African women had undergone this mutilation.

The incidence of sexual violence during the past year of living in France are reported in Table 2. Sexual violence occurred during the past year of living in France for 84 females (26.3% weighted [95% CI, 24–28.8]), 17 of whom were raped (incidence proportion weighted, 4.8% [95% CI, 3.7–6.1]) and 15 of whom were raped more than once. Recourse to prostitution occurred during the past year of living in France for 10 females (incidence proportion weighted, 2.1% [95% CI, 1.4–3]). For post-arrival SV, sexual assault and exhibition, face-to-face interviews revealed significantly more events than telephone interviews (p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Incidence proportions of sexual violence during the past year of living in France.

| Na | n | Unweighted incidence proportions over one year of exposure to the host territory (%)b | Weighted incidence proportions over one year of exposure to the host territory (%)b | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any type of sexual violence during the past year | 273 | ||||

| Yes | 84 | 30.8 | 26.3 | (24–28.8) | |

| Including | |||||

| 1 | 51 | 18.7 | |||

| >1 | 33 | 12.1 | |||

| Rape during the past year | 266 | ||||

| Yes | 17 | 6.4 | 4.8 | (3.7–6.1) | |

| Including | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 0.7 | |||

| >1 | 15 | 5.5 | |||

| Attempted rape during the past year | 248 | ||||

| Yes | 30 | 12.1 | 8.8 | (7.4–10.4) | |

| Including | |||||

| 1 | 23 | 8.4 | |||

| >1 | 7 | 2.6 | |||

| Rape or attempted rape during the past year | 266 | ||||

| Yes | 47 | 17.7 | 12.9 | (11.2–14.8) | |

| Sexual assault during the past year | 264 | ||||

| Yes | 57 | 21.6 | 18.9 | (16.8–21.1) | |

| Including | |||||

| 1 | 24 | 8.8 | |||

| >1 | 33 | 12.1 | |||

| Sexual exhibition during the past year | 264 | ||||

| Yes | 22 | 8.3 | 8.5 | (7.1–10.1) | |

| Including | |||||

| 1 | 8 | 2.9 | |||

| >1 | 14 | 5.1 | |||

| Prostitution during the past year | 266 | ||||

| Yes | 10 | 3.8 | 2.1 | (1.4–3) | |

| Blackmail during the past year | 263 | ||||

| Yes | 86 | 32.7 | 27.9 | (25.6–30.5) |

N: number of data available after excluding missing data. 95% CI estimate from the results of our sample the corresponding figures for all female asylum seekers living in France.

The unweighted incidence proportions are the raw results from our database. The weighted incidence proportions correspond to an adjustment for our age and geographical deviation from the overall source population (OFII file).

Table 3 presents the circumstances surrounding the occurrence of SV. More than 9 out of 10 females in our sample had consulted a doctor during the past year (i.e., more than 6 out of 10 general practitioners) but less than 1 out of 10 consulted care or police services when the violence occurred. More than half of the females who experienced violence did not seek assistance at all. Thirty-four events took place in the accommodation (40.5%) and the perpetrator were mostly unknown.

Table 3.

Life context and circumstances surrounding the occurrence of sexual violence.

| N | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| During the past year, among the people who lived with you, were there any individual(s) with whom you felt insecure? | 272 | |

| No | ||

| Yes | 170 (62.5) | |

| Including | 102 (37.5) | |

| Friend | 12 (4.4) | |

| Family | 2 (0.7) | |

| Intimate partner | 10 (3.7) | |

| Individuals sharing the accommodation | 44 (16.2) | |

| Unknown | 34 (12.5) | |

| During the past year, when you had a personal problem, who did you confide in? (Several answers possible) | 272 | |

| Friend/intimate partner/family | 150 (55.1) | |

| A health care or social professional | 95 (34.9) | |

| Spiritual resources | 5 (1.8) | |

| No one | 48 (17.6) | |

| During the past year, have you visited a doctor? | 273 | |

| No | 9 (3.3) | |

| Yes | ||

| Including (Several answers possible) | 264 (96.7) | |

| Emergency department | 67 (24.5) | |

| General practitioner | 179 (65.6) | |

| Psychiatrist or psychologist | 65 (23.8) | |

| Gynaecologist | 166 (60.8) | |

| Doctor of other specialties | 57 (20.9) | |

| Among women who had been exposed to any type of sexual violence during the past year (n = 84) | ||

| Sexual violence occurring in the accommodation | 84 | |

| No | 50 (59.5) | |

| Yes | 34 (40.5) | |

| Accommodation at the time of the occurrence of sexual assault or exhibition | 79 | |

| Single dwelling with legal | 4 (5.1) | |

| National Asylum Support System | 28 (35.4) | |

| Emergency housing support | 6 (7.6) | |

| Lack of a support system | 41 (56.9) | |

| Accommodation at the time of the occurrence of rape or attempted | 47 | |

| Single dwelling with legal | 0 (0) | |

| National Asylum Support System | 15 (31.9) | |

| Emergency housing support | 8 (17) | |

| Lack of a support system | 24 (51.1) | |

| Individual who committed the sexual assault or exhibition | 79 | |

| Employer | 2 (2.5) | |

| Intimate partner | 1 (1.3) | |

| Friend | 4 (5.1) | |

| Individual sharing the accommodation | 4 (5.1) | |

| Unknown | 68 (86.1) | |

| Individual who committed or attempted the rape | 47 | |

| Intimate Partner | 8 (17) | |

| Friend | 9 (19) | |

| Prostitution client | 3 (6.4) | |

| Individual sharing the accommodation | 5 (10.6) | |

| Employer | 2 (4.3) | |

| Unknown | 20 (42.6) | |

| Assistance requested when the violence occurred? | 84 | |

| No | 45 (53.6) | |

| Yes | 39 (46.4) | |

| If assistance requested | ||

| Type of assistance (several answers possible) | ||

| Surroundings (friend/family/Intimate partner) | 23 (27.4) | |

| Social worker or lawyer | 16 (19) | |

| Police services | 5 (6) | |

| A professional caregiver | 6 (7.1) | |

| Reasons for not seeking assistance (Several answers possible) | ||

| Did not know who to contact | 23 (27.4) | |

| Fear of retaliation | 12 (14.3) | |

| Shame | 10 (11.9) | |

| Did not see the point | 20 (23.8) | |

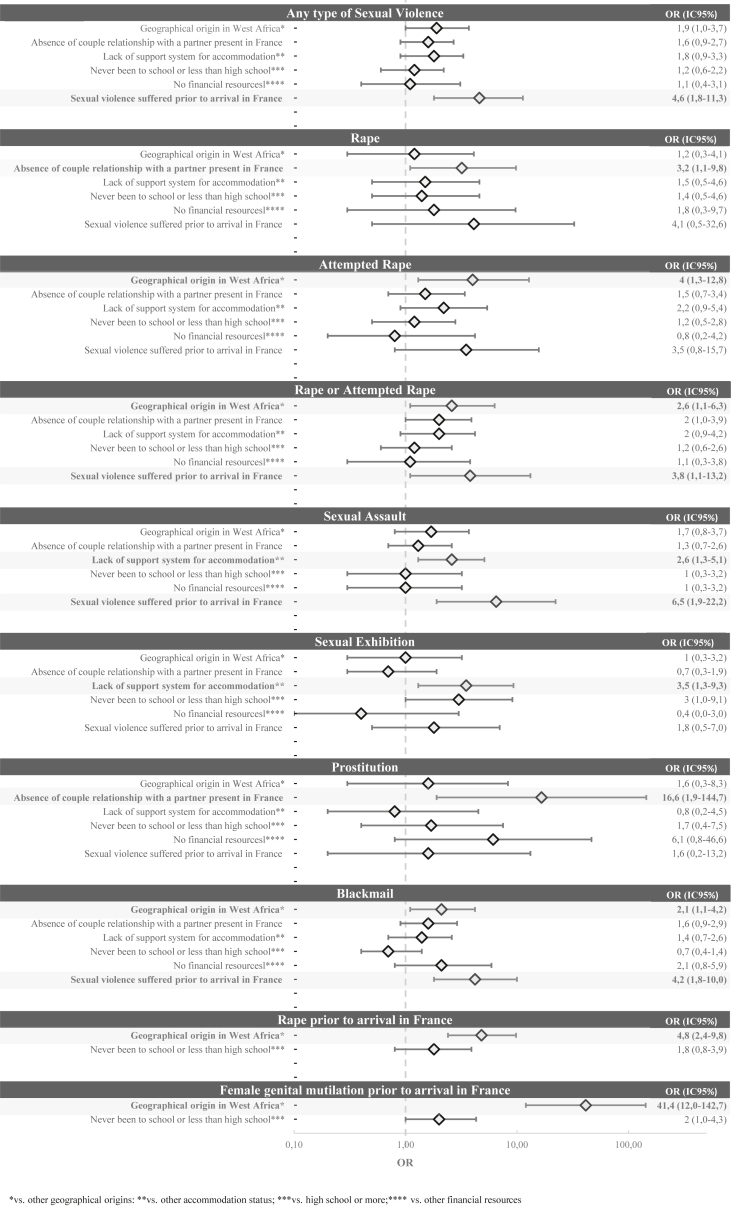

The factors associated with sexual violence are reported in Table 4 (univariate analysis), Table 5 and Fig. 2 (multivariate analysis). According to the multivariate analysis, the occurrence of SV, rape and attempted rape in France varied according to geographic origin, couple relationship status and experience with SV prior to arrival in France. Females who had experienced SV before arriving in France were significantly (p < 0.05) more likely to experience SV, rape or attempted, sexual assault and black mail after they arrived in France, with ORs ranging from 3.8 to 4.6. Females from West Africa were subjected to attempted rape more frequently than females from other geographic origins (OR = 4.0 [95% CI, 1.3–12.8; p = 0.02]), while females who did not have a relationship with a partner in France were more likely to experience rape than those who had a partner in France (OR = 3.2 [95% CI, 1.1–9.8; p = 0.04]).

Table 4.

Factors associated with sexual violence according to the results of univariate analysis.b

| Any type of sexual violence in France |

Rape or attempted rape in France |

Rape |

Attempted rape |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N | Yes n (%) | OR | 95% CI | Total N | Yes n (%) | OR | 95% CI | Total N | Yes n (%) | OR | 95% CI | Total N | Yes n (%) | OR | 95% CI | |

| Age | 273 | 266 | 266 | 248 | ||||||||||||

| 18- to 25-year-old | 23 (34.8) | 1 | 14 (21.9) | 1 | 3 (4.7) | 1 | 11 (18.0) | 1 | ||||||||

| 26- to 35-year-old | 42 (32.1) | 0.9 | (0.5–1.6) | 22 (17.2) | 0.7 | (0.4–1.6) | 9 (7.0) | 1.5 | (0.4–5.9) | 13 (10.9) | 0.6 | (0.2–1.3) | ||||

| 36- to 45-year-old | 11 (22.9) | 0.6 | (0.2–1.3) | 8 (16.7) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.9) | 4 (8.3) | 1.8 | (0.4–8.7) | 4 (9.3) | 0.5 | (0.1–1.6) | ||||

| > 46-year-old | 8 (28.6) | 0.7 | (0.3–2.0) | 3 (11.5) | 0.5 | (0.1–1.8) | 1 (3.8) | 0.8 | (0.1–8.2) | 2 (8.0) | 0.4 | (0.1–1.9) | ||||

| Number of dependent children | 271 | 266 | 266 | 284 | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 10 (22.7) | 1 | 6 (14.0) | 1 | 3 (7.0) | 1 | 3 (7.5) | 1 | ||||||||

| 1 | 29 (35.8) | 1.9 | (0.8–4.4) | 15 (18.8) | 1.4 | (0.5–4.0) | 5 (6.3) | 0.9 | (0.2–3.9) | 10 (13.3) | 1.9 | (0.5–7.3) | ||||

| >1 | 45 (30.8) | 1.5 | (0.7–3.3) | 26 (18.2) | 1.4 | (0.5–3.6) | 9 (6.3) | 0.9 | (0.2–3.5) | 17 (12.8) | 1.8 | (0.5–6.5) | ||||

| Geographical origin | 272 | 266 | 266 | 248 | ||||||||||||

| West Africa | 58 (37.9) | 1 | 36 (24.0) | 1 | 11 (7.3) | 1 | 25 | 1 | ||||||||

| Maghreb | 5 (33.3) | 0.8 | (0.3–2.5) | 3 (21.4) | 0.9 | (0.2–3.3) | 2 (14.3) | 2.1 | (0.4–10.6) | 1 | 0.4 | (0.1–3.4) | ||||

| Rest of Africa | 9 (34.6) | 0.9 | (0.4–2.1) | 6 (24.0) | 1 | (0.4–2.7) | 3 (12) | 1.7 | (0.4–6.7) | 3 | 0.8 | (0.2–2.8) | ||||

| South America | 4 (25.0) | 0.5 | (0.2–1.8) | 0 (0.0) | NR | NR | 0 (0) | 0.0 | NR | 0 | NR | NR | ||||

| Middle East | 2 (10.0) | 0.2 | (0.0–0.8) | 0 (0.0) | NR | NR | 0 (0) | 0.0 | NR | 0 | NR | NR | ||||

| Europe | 5 (20.0) | 0.4 | (0.1–1.2) | 2 (8.3) | 0.3 | (0.1–1.3) | 1 (4.2) | 0.5 | (0.1–4.5) | 1 | 0.2 | (0.0–1.6) | ||||

| Asia | 1 (5.9) | 0.1 | (0.0–0.8) | 0 (0.0) | NR | NR | 0 (0) | 0.0 | NR | 0 | NR | NR | ||||

| Couple relationship with partner present in France | 273 | 266 | 266 | 248 | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 41 (26.6)) | 1 | 21 (14.0) | 1 | 5 (3.3) | 1 | 16 (11.1) | 1 | ||||||||

| No | 43 (36.1) | 1.6 | (0.9–2.6) | 26 (22.4) | 1.8 | (0.9–3.3) | 12 (10.3) | 3.3 | (1.1–9.8) | 14 (13.5) | 1.2 | (0.6–2.7) | ||||

| Accommodation most of the time during the past year | 265 | 265 | 265 | 248 | ||||||||||||

| National Asylum Support System | 46 (30.1) | 1 | 26 (17.2) | 1 | 9 (6.3) | 1 | 17 (12.0) | 1 | ||||||||

| Lack of a support system | 27 (36.0) | 1.3 | (0.7–2.3) | 16 (22.2) | 1.4 | (0.7–2.8) | 6 (9.1) | 1.4 | (0.5–4.2) | 10 (15.4) | 1.3 | (0.6–3.1) | ||||

| Single dwelling with legal lease | 3 (13.6) | 0.4 | (0.1–1.3) | 0 (0) | NR | NR | 0 (0) | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||

| Emergency housing support | 7 (35.0) | 1.3 | (0.5–3.3) | 4 (20.0) | 1.2 | (0.4–3.9) | 1 (5.3) | 0.8 | (0.1–6.9) | 3 (15.8) | 1.4 | (0.4–5.2) | ||||

| Level of education | 269 | 264 | 264 | 246 | ||||||||||||

| Never been to school | 21 (35.0) | 1 | 13 (23.2) | 1 | 7 (12.5) | 1 | 6 (12.2) | 1 | ||||||||

| Less than high school | 21 (40.4) | 1.3 | (0.6–2.7) | 13 (25.0) | 1.1 | (0.5–2.7) | 2 (3.8) | 0.3 | (0.1–1.4) | 11 (22.0) | 2.0 | (0.7–6.0) | ||||

| High school | 24 (33.8) | 1.0 | (0.5–2.0) | 16 (22.5) | 1.0 | (0.4–2.2) | 7 (9.8) | 0.8 | (0.3–2.3) | 9 (14.0) | 1.2 | (0.4–3.5) | ||||

| More than high school | 17 (19.8) | 0.5 | (0.2–1.0) | 5 (5.9) | 0.2 | (0.1–0.7) | 1 (1.2) | 0.1 | (0.0–0.7) | 4 (4.8) | 0.4 | (0.1–1.4) | ||||

| Financial resources | 269 | 265 | 265 | 248 | ||||||||||||

| State financial aid | 53 (35.1) | 1 | 29 (19.6) | 1 | 10 (6.7) | 1 | 19 (13.9) | 1 | ||||||||

| None | 8 (38.1) | 1.1 | (0.4–2.9) | 5 (25.0) | 1.4 | (0.5–4.1) | 2 (10) | 1.5 | (0.3–7.6) | 3 (16.7) | 1.2 | (0.3–4.7) | ||||

| Undeclared work | 11 (28.2) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.6) | 7 (17.9) | 0.9 | (0.4–2.2) | 2 (5.1) | 0.8 | (0.2–3.6) | 5 (13.5) | 1.0 | (0.3–2.8) | ||||

| Family, friend or associate support | 6 (17.1) | 0.4 | (0.2–1.5) | 0 (0) | NR | NR | 0 (0) | NR | NR | 0 (0) | NR | NR | ||||

| Work with legal contract | 5 (21.7) | 0.5 | (0.2–1.5) | 5 (21.7) | 1.1 | (0.4–3.3) | 2 (8.7) | 1.3 | (0.3–6.4) | 3 (14.3) | 1.0 | (0.3–3.9) | ||||

| Sexual assault |

Sexual exhibition |

Prostitution |

Blackmail |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N | Yes N (%) | OR | 95% CI | Total N | Yes | OR | 95% CI | Total N | Yes | OR | 95% CI | Total N | Yes | OR | 95% CI | |

| Age | 264 | 264 | 266 | 263 | ||||||||||||

| 18- to 25-year-old | 14 (22.2) | 1 | 5 (7.8) | 1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 | 20 (31.7) | 1 | ||||||||

| 26- to 35-year-old | 35 (27.1) | 1.3 | (0.6–2.6) | 12 (9.4) | 1.2 | (0.4–3.6) | 5 (3.9) | 5.8a | (0.3–109.4) | 45 (35.2) | 1.2 | (0.6–2.2) | ||||

| 36- to 45-year-old | 4 (8.7) | 0.3 | (0.1–11) | 2 (4.3) | 0.5 | (0.1–2.9) | 4 (8.5) | 13.6a | (0.7–264.2) | 14 (30.4) | 0.9 | (0.4–2.1) | ||||

| > 46-year-old | 4 (15.4) | 0.6 | (0.2–2.2) | 3 (11.5) | 1.5 | (0.3–7.0) | 1 (3.8) | 7.7a | (0.3–202.2) | 7 (26.9) | 0.5 | (0.3–2.2) | ||||

| Number of dependent children | 264 | 264 | 266 | 263 | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 8 (18.6) | 1 | 3 (7.0) | 1 | 0 (0) | 1 | 15 (35.7) | 1 | ||||||||

| 1 | 22 (28.2) | 1.7 | (0.7–4.3) | 9 (11.5) | 1.7 | (0.4–6.8) | 1 (1.3) | 1.72a | (0.1–44.6) | 24 (31.2) | 0.8 | (0.4–1.8) | ||||

| >1 | 27 (18.9) | 1.0 | (0.4–2.4 | 10 (7.0) | 1.0 | (0.3–3.8) | 9 (6.3) | 6.24a | (0.3–112.9) | 47 (32.6) | 0.9 | (0.4–1.8) | ||||

| Geographical origin | 264 | 264 | 266 | 263 | ||||||||||||

| West Africa | 39 (26.0) | 1 | 14 (9.4) | 1 | 7 (4.7) | 1 | 59 (39.9) | 1 | ||||||||

| Maghreb | 5 (35.7) | 1.6 | (0.5–5.0) | 1 (7.1) | 0.7 | (0.1–6.1) | 0 (0.0) | NR | NR | 4 (30.8) | 0.7 | (0.2–2.3) | ||||

| Rest of Africa | 3 (12.5) | 0.4 | (0.1–1.4) | 3 (12.5) | 1.4 | (0.4–5.2) | 2 (7.7) | 1.7 | (0.3–8.6) | 9 (36.0) | 0.9 | (0.4–2.0) | ||||

| South America | 4 (25.0) | 0.9 | (0.3–3.1) | 1 (6.3) | 0.6 | (0.1–5.2) | 1 (6.3) | 1.4 | (0.2–11.7) | 6 (37.5) | 0.9 | (0.3–2.6) | ||||

| Middle East | 1 (5.0) | 0.1 | (0.0–1.1) | 1 (5.0) | 0.5 | (0.1–4.1) | 0 (0.0) | NR | NR | 2 (10.0) | 0.2 | (0.0–0.7) | ||||

| Europe | 4 (16.7) | 0.6 | (0.2–1.8) | 2 (8.3) | 0.9 | (0.2–4.1) | 0 (0.0 | NR | NR | 5 (20.8) | 0.4 | (0.1–1.1) | ||||

| Asia | 1 (5.9) | 0.2 | (0.0–1.4) | 0 (0.0) | NR | NR | 0 (0.0) | NR | NR | 1 (5.9) | 0.1 | (0.0–0.7) | ||||

| Couple relationship with partner present in France | 264 | 264 | 266 | 263 | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 28 (18.8) | 1 | 13 (8.7) | 1 | 1 (0.7) | 1 | 43 (28.5) | 1 | ||||||||

| No | 29 (25.2) | 1.4 | (0.8–2.6) | 9 (7.9) | 0.9 | (0.4–2.2) | 9 (7.9) | 12.9 | (1.6–103.7) | 43 (38.4) | 1.6 | (0.9–2.6) | ||||

| Accommodation most of the time during the past year | 263 | 263 | 266 | 266 | ||||||||||||

| National Asylum Support System | 27 (17.9) | 1 | 10 (6.6) | 1 | 6 (3.9) | 1 | 54 (35.8) | 1 | ||||||||

| Lack of a support system | 23 (31.9) | 2.2 | (1.1–4.1) | 10 (13.9) | 2.3 | (0.9–5.7) | 3 (4.2) | 1.1 | (0.3–4.4) | 26 (36.6) | 1.0 | (0.6–1.9) | ||||

| Single dwelling with legal lease | 3 (13.6) | 0.7 | (0.2–2.6) | 0 (0) | NR | NR | 0 (0) | NR | NR | 2 (9.1) | 0.2 | (0.0–0.8) | ||||

| Emergency housing support | 4 (22.2) | 1.3 | (0.4–4.3) | 2 (11.1) | 1.8 | (0.4–8.8) | 1 (5.0) | 1.3 | (0.1–11.2) | 4 (21.1) | 0.5 | (0.2–1.5) | ||||

| Level of education | 262 | 262 | 264 | 261 | ||||||||||||

| Never been to school | 13 (22.8) | 1 | 6 (10.5) | 1 | 2 (3.5) | 1 | 22 (38.6) | 1 | ||||||||

| Less than high school | 14 (28.0) | 1.3 | (0.5–3.2) | 7 (14.3) | 1.4 | (0.4–4.6) | 4 (7.7) | 2.3 | (0.4–13.1) | 16 (30.8) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.6) | ||||

| High school | 13 (18.6) | 0.8 | (0.3–1.8) | 5 (7.1) | 0.7 | (0.2–2.3) | 3 (4.3) | 1.2 | (0.2–7.6) | 24 (35.3) | 0.9 | (0.4–1.8) | ||||

| More than high school | 17 (20.0) | 0.8 | (0.4–1.9) | 3 (3.5) | 0.3 | (0.1–1.3) | 1 (1.2) | 0.4 | (0.0–3.7) | 23 (27.4) | 0.6 | (0.3–1.2) | ||||

| Financial resources | 263 | 263 | 266 | 263 | ||||||||||||

| State financial aid | 35 (23.6) | 1 | 16 (10.8) | 1 | 5 (3.4) | 1 | 50 (34.0) | 1 | ||||||||

| None | 5 (26.3) | 1.2 | (0.4–3.4) | 1 (5.3) | 0.5 | (0.1–3.7) | 2 (9.5) | 3.0 | (0.5–16.7) | 9 (45.0) | 1.6 | (0.6–4.1) | ||||

| Undeclared work | 9 (23.7) | 1.0 | (0.4–2.3) | 1 (2.6) | 0.2 | (0.0–1.7) | 3 (7.7) | 2.4 | (0.5–10.5) | 14 (35.9) | 1.1 | (0.5–2.3) | ||||

| Family, friend or associate support | 6 (17.1) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.7) | 2 (5.7) | 0.5 | (0.1–2.3) | 0 (0.0) | NR | NR | 6 (17.6) | 0.4 | (0.1–1.1) | ||||

| Work with legal contract | 2 (8.7) | 0.3 | (0.1–1.4) | 2 (8.7) | 0.8 | (0.2–3.7) | 0 (0.0) | NR | NR | 7 (30.4) | 0.8 | (0.3–2.2) | ||||

| Sexual violence prior to arrival in France |

Rape prior to arrival in Franc |

Female genital mutilation prior to arrival in France |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N | Yes N (%) | OR | 95% CI | Total N | Yes | OR | 95% CI | Total N | Yes | OR | 95% CI | |

| Geographical origin | 267 | 203 | 199 | |||||||||

| West Africa | 132 (88.0) | 1 | 101 (84.2) | 1 | 77 (66.4) | 1 | ||||||

| Maghreb | 9 (64.3) | 0.2 | (0.1–0.8) | 4 (44.4) | 0.2 | (0.0–0.6) | 1 (11.1) | 0.1 | (0.0–0.5) | |||

| Rest of Africa | 20 (76.9) | 0.5 | (0.2–1.3) | 13 (76.5) | 0.6 | (0.2–2.1) | 2 (11.8) | 0.1 | (0.0–0.3) | |||

| South America | 9 (60.0) | 0.2 | (0.1–0.6) | 6 (46.2) | 0.2 | (0.0–0.5) | 0 (0) | NR | NR | |||

| Middle East | 12 (60.0) | 0.2 | (0.1–0.6) | 4 (30.8) | 0.1 | (0.0–0.3) | 0 (0) | NR | NR | |||

| Europe | 14 (56.0) | 0.2 | (0.1–0.4) | 6 (33.3) | 0.1 | (0.0–0.3) | 0 (0) | NR | NR | |||

| Asia | 6 (35.3) | 0.1 | (0.0–0.2) | 5 (38.5) | 0.1 | (0.0–0.4) | 0 (0) | NR | NR | |||

| Level of education | 264 | 201 | 197 | |||||||||

| Never been to school | 53 (91.4) | 1 | 42 (85.7) | 1 | 31 (67.4) | 1 | ||||||

| Less than high school | 41 (80.4) | 0.4 | (0.1–1.2) | 27 (79.4) | 0.6 | (0.2–2.0) | 19 (57.6) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.7) | |||

| High school | 56 (78.9) | 0.4 | (0.1–1.0) | 43 (76.8) | 0.6 | (0.2–1.5) | 24 (42.9) | 0.4 | (0.2–0.8) | |||

| More than high school | 50 (59.5) | 0.1 | (0.1–0.4) | 26 (41.9) | 0.1 | (0.0–0.3) | 6 (9.7) | 0.1 | (0.0–0.1) | |||

Data are effective (n). Significance variables are indicated in bold (p < 0.05).

Due to limited effectives for these data, OR and CI has been calculated using a penalized likelihood method.

N: number of data available after excluding missing data. NR: Not reached.

Table 5.

Factors associated with sexual violence according to the results of multivariate analysis.

| Any type of sexual Violence |

Rape |

Attempted rape |

Rape or attempted rape |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Geographical origin in West Africa (vs. other geographical origins) | 1.9 | (1.0–3.7) | 0.07 | 1.2 | (0.3–4.1) | 0.79 | 4.0 | (1.3–12.8) | 0.02 | 2.6 | (1.1–6.3) | 0.03 |

| Absence of couple relationship with a partner present in France | 1.6 | (0.9–2.7) | 0.13 | 3.2 | (1.1–9.8) | 0.04 | 1.5 | (0.7–3.4) | 0.35 | 2.0 | (1.0–3.9) | 0.05 |

| Lack of support system for accommodation (vs. other accommodation status) | 1.8 | (0.9–3.3) | 0.07 | 1.5 | (0.5–4.6) | 0.51 | 2.2 | (0.9–5.4) | 0.09 | 2.0 | (0.9–4.2) | 0.08 |

| Never been to school or less than high school (vs. high school or more) | 1.2 | (0.6–2.2) | 0.64 | 1.4 | (0.5–4.6) | 0.54 | 1.2 | (0.5–2.8) | 0.73 | 1.2 | (0.6–2.6) | 0.56 |

| No financial resources (vs. other financial resources) | 1.1 | (0.4–3.1) | 0.89 | 1.8 | (0.3–9.7) | 0.51 | 0.8 | (0.2–4.2) | 0.80 | 1.1 | (0.3–3.8) | 0.90 |

| Sexual violence suffered prior to arrival in France | 4.6 | (1.8–11.3) | <0.01 | 4.1 | (0.5–32.6) | 0.19 | 3.5 | (0.8–15.7) | 0.11 | 3.8 | (1.1–13.2) | 0.03 |

|

Sexual assault |

Sexual exhibition |

Prostitution |

Blackmail |

|||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Geographical origin in West Africa (vs. other geographical origins) | 1.7 | (0.8–3.7) | 0.17 | 1.0 | (0.3–3.2) | 0.97 | 1.6 | (0.3–8.3) | 0.58 | 2.1 | (1.1–4.2) | 0.03 |

| Absence of couple relationship with a partner present in France | 1.3 | (0.7–2.6) | 0.33 | 0.7 | (0.3–1.9) | 0.52 | 16.6 | (1.9–144.7) | 0.01 | 1.6 | (0.9–2.9) | 0.09 |

| Lack of support system for accommodation (vs. other accommodation status) | 2.6 | (1.3–5.1) | 0.01 | 3.5 | (1.3–9.3) | 0.01 | 0.8 | (0.2–4.5) | 0.84 | 1.4 | (0.7–2.6) | 0.32 |

| Never been to school or less than high school (vs. high school or more) | 1.0 | (0.3–3.2) | 0.95 | 3.0 | (1.0–9.1) | 0.05 | 1.7 | (0.4–7.5) | 0.51 | 0.7 | (0.4–1.4) | 0.31 |

| No financial resources (vs. other financial resources) | 1.0 | (0.3–3.2) | 1.00 | 0.4 | (0.0–3.0) | 0.34 | 6.1 | (0.8–46.6) | 0.08 | 2.1 | (0.8–5.9) | 0.16 |

| Sexual violence suffered prior to arrival in France | 6.5 | (1.9–22.2) | <0.01 | 1.8 | (0.5–7.0) | 0.38 | 1.6 | (0.2–13.2) | 0.71 | 4.2 | (1.8–10.0) | <0.01 |

|

Rape prior to arrival in France |

Female genital mutilation prior to arrival in France |

|||||||||||

| OR 95% CI p value | OR 95% CI p value | |||||||||||

| Geographical origin in West Africa (vs. other geographical origins) | 4.8 | (2.4–9.8) | <0.001 | 41.4 | (12.0–142.7) <0.001 | |||||||

| Never been to school or less than high school (vs. high school or more) | 1.8 | (0.8–3.9) | 0.14 | 2.0 | (1.0–4.3) | 0.07 | ||||||

Significance variables are indicated in bold (p < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Multivariate analysis.

For other types of SV, significantly higher ORs for instances of sexual assault and exhibition were found among females without support systems that provided them accommodation (2.6 [95% CI, 1.3–5.1; p = 0.01] and 3.5 [95% CI, 1.3–9.3; p = 0.01], respectively). A strong specific influence of the absence of a couple relationship with a partner in France was found in the case of prostitution (OR = 16.6 [95% CI, 1.9–144.7] p = 0.01). With regard to sexual blackmail, females from West Africa (OR = 2.1, [95% CI, 1.1–4.2; p = 0.03]) seemed to be more at risk.

Regarding documented episodes of rape prior to arriving in France, geographical origin in West Africa was found to be associated with rape (OR = 4.8 [95% CI, 2.4–9.8; p < 0.001]) and female genital mutilation (OR = 41.4, [95% CI, 12.0–142.7; p < 0.001]).

Discussion

This study expanded data on the incidence of SV during the past year of living in a European host region among recently arrived asylum-seeking females. The results highlight a high incidence proportion of SV in these females in the period following their arrival in Southern France. In France, 0.26% of females report having experienced rape in the past year,25 which is more than 18 times lower than the occurrence reported by the asylum-seeking females included in our study. Similarly, the yearly occurrences of SV (2.9%)25 and rape or attempted rape (0.31%)25 in the general population are at least 9 times lower than those found in our study. Thus, our findings seem to indicate that asylum-seeking females are exposed to SV in this European host region more frequently than the host population. These findings raise the question of how host countries can prevent such violence in their territories, particularly towards this specific population of females, which seems to be overexposed to SV. Our findings highlight the role of accommodation in this context; the importance of this factor has been reported by the ANRS-Parcours study among female migrants.13 These factors should be considered in light of the fact that nearly one in three females included in our sample did not receive accommodation support most of the time during the past year. Previous work by Keygnaert et al. has shown that exposure to sexual violence is significant, even in reception centres for asylum seekers.11,14,15 The integration of our findings points to an overexposure of female asylum seekers to sexual violence in their host country, regardless of the type of accommodation. This overexposure seems to be even higher among females without partner in France, who are from West Africa or who have experienced SV prior to their arrival. As is the case for humanitarian emergencies, an interinstitutional report and plan to stop SV against asylum-seeking females in their host country should be developed.

The known worldwide lifetime prevalence of non-partner SV is 7.2%6; this rate is nearly 10 times lower than the prevalence of rape in our study population prior to their arrival in France. These findings raise questions for the health systems of the host countries concerning whether and how to organize screening and care for these females to prevent the known health consequences of such violence6,23,24 and to limit its costs.26 In particular, we consider the rare use of healthcare services by these women when SV occurs, which we found. Future data could study care experiences after SV among AS, as has been explored in this population in other situations.27 This situation also raises the question of the possibility of granting international protection to females who are fleeing SV. In 2021, the French Office for the Protection of Refugees and Stateless Persons (OFPRA) accepted 26.4% of female asylum applications from Africa,4 whereas 56.3% of the African females included in our sample had undergone genital mutilation. Therefore, it seems that France does not grant international protection to all females who have undergone this form of mutilation.

Females who were sexually abused before their arrival in France were more likely to be sexually abused again in their host country. This association with prior victimization has already been described in the literature.28,29 The overexposure to SV exhibited by females from West Africa both in France and prior to their migration is consistent with the trafficking networks that affect Nigerian populations identified by OFPRA in France.4 However, no association was found between geographical origin and prostitution. One possible explanation for this finding is that trafficking victims are afraid to report this phenomenon.

Limitations

The main limitation of our study is the number of non-responding females. It is possible that SV in our study was overestimated by the greater participation of victims of SV, who may have felt more concerned. On the other hand, we could not include some females who did not wish to participate and reported that they did not want to discuss their history of violence. Some females could not even be reached directly because their partners were opposed to our team interacting with them directly. This situation could contribute to an underestimation of SV among AS, as has already been described in the literature.13,17 Asylum seekers have unstable living conditions (residence permit, work, housing) which make them hard to reach,14 and partly explains this limitation of our study. We attempted to reach the entirety of this population; however, many phone numbers were wrong. We can hypothesize that these profiles correspond to females who have encountered more difficulties in social integration since their arrival and are probably more vulnerable. We finally know the rate of non-respondents because we chose a design that allowed us to describe the size of our target population, which was not limited to accommodation and care facilities. The high level of occurrence of SV may also have been overestimated due to the significantly higher proportion of females from West Africa included in our sample than in the source population. We also found an association between this geographical origin and certain forms of SV suffered before and after arrival in France. The association between West Africa and certain types of SV may explain the difference in nationality between our sample and the source population. Indeed, females from West Africa appear to be victims of SV more frequently, so they may have been more concerned about this issue and therefore more inclined to participate. Additionally, the list of countries considered safe by OFPRA30 includes 9 European countries. Conversely, we can hypothesize that females from these countries, which are considered safer and associated with less exposure to SV, felt less concerned about the survey and therefore were less likely to participate, potentially explaining the underrepresentation of European females in our sample. This may have led to an overestimation of sexual violence in our sample. To limit this bias, we presented adjusted incidence proportions that take this age and geographical origin deviation from the OFII file into account. Ultimately, we included only asylum-seeking females from one of the 12 regions of France, the south. Statistics on the distribution of sexual violence in France reveal disparities between regions but our study area does not appear to have an over-representation of sexual violence compared with other regions of France.31 In addition, urban areas have higher rates than rural municipalities,31 but we did not collect the current municipality of the females included. It is therefore possible that our findings were influenced by female's place of residence in a way that we cannot describe. That's why national inference should be treated with caution. The proportions of female victims of rape or attempted rape in French territories in our study were very similar to those found among female migrants from Africa in the ANRS-Parcours study (8). The lifetime prevalence of SV among AS that we found was close to that found in 2020 in the USA.10 These facts reinforce the external consistency of our findings, and we can hypothesize that the occurrence of SV would remain very high even if better geographical representation was achieved. The design of our study was also constructed following the WHO's recommendations for research on sexual violence: “It is usually more important to have high-quality data that are not vulnerable to criticism on methodological (…) rather than expending extra effort to make a study “national”32

Slightly more than a third of our interviews were conducted by phone, and an association was found between the events reported and the face-to-face process. This underestimation is linked to an underrevelation according to the conditions of the interview and has already been described in the literature.14,15 Additionally, the events reported are declarative and subject to desirability and recall bias. However, the studies referenced concerning the occurrence of SV among AS10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 are based on declarative data. To limit the effects of the method used to detect and define SV, we used the same definitions and phrases to classify SV as the reference survey in France that quantified SV in the general population.25 Ultimately, our findings are limited to individuals declared female at birth and did not determine the incidence of sexual violence among asylum-seeking males or transgender people and unaccompanied asylum-seeking minors. The recommendations for migrant research programmes state that the study population should be well defined to be homogeneous and comparable. We therefore chose asylum-seeking females. Similar study specifically on males or unaccompanied minors would be relevant. Especially considering that previous studies have suggested that victimization of asylum seekers seemed more gender balanced then what was previously found and in the general population.14 With regard to the partner present in France, we did not distinguish between those met in France and the others, nor did we identify “partner's income” as a source of income.

The retrospective design of our study does not allow us to establish causal links. However, the strength of the statistical associations we found and the consistency with the literature could allow our study to be considered a source of insights concerning SV among asylum-seeking females and a means to prevent this phenomenon.

Conclusion

Our regional retrospective cohort study reveals a high incidence of sexual violence during the past year of living in France among asylum-seeking females who recently arrived in Southern Region. The months following their arrival in this European host region was a period of high exposure to sexual violence. The reception conditions provided by the host country played a role in the occurrence of sexual assaults. A particular vulnerability was identified among asylum-seeking females and even more so among those who had experienced sexual violence prior to arrival in France, those from West Africa, and those who did not have a couple partner in the host country. These vulnerabilities should be considered when developing strategies to prevent and detect such violence.

Contributors

JK, PA and MJ conceived and designed the study, wrote the protocol, conducted the analysis, and wrote the manuscript. ML, RCB, and ST conducted the literature search, wrote the protocol, and participated in data collection and analysis. AB and GG critically reviewed the report for important intellectual content. MV and AD participated in the development of the questionnaire and data collection. AL conducted the analysis.

Data sharing statement

Deidentified participant collected data, including individual participant data, will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics committee approval

This study was approved by one of the French Research Ethics committees under the authority of the Ministry of Research on June 18, 2021 (approval number 21.04.02.59049). Its registration number on ClinicalTrials.gov is NCT05007431. All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki regarding ethical aspects, information, and consent of subjects to participate and data publication. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to give special thanks to the OFII agents, Me Grandmottet and her team, who made it possible to identify all the females eligible for this study. Additionally, we thank the OFII management staff, particularly Me Le-Luong, for authorizing this study and Drs. Crocq and Sebille for their comments on the manuscript. The authors thank Mr Nardini for his help in constructing Fig. 2 and Mrs Lepine for supporting our investigators. Finally, the authors are very grateful to the reviewers for all their comments which improved the quality of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2023.100731.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.High Commissioner for Refugees . United Nations; 2020. UNHCR global report - forced displacement in 2020; p. 123.https://www.unhcr.org/flagship-reports/globaltrends/ URL: [Google Scholar]

- 2.World health organisation . 2018. The health of refugees and migrants in the WHO European region; p. 114.https://www.euro.who.int/fr/publications/html/report-on-the-health-of-refugees-and-migrants-in-the-who-european-region-no-public-health-without-refugee-and-migrant-health-2018/en/index.html URL: [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eurostat . 2022. Annual asylum statistics.https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Annual_asylum_statistics URL: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Office Francais de protection des refugiés et des apatrides. Rapport d’activité. 2021:140. https://www.ofpra.gouv.fr/publications/les-rapports-dactivite URL: [Google Scholar]

- 5.High Commissioner for Refugees . 2020. UNHCR policy on the prevention of, risk mitigation and response to gender-based violence; p. 24.https://www.unhcr.org/5fa018914/unhcr-policy-prevention-risk-mitigation-response-gender-based-violence URL: [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organisation . 2021. Global, regional and national estimates for intimate partner violence against females and global and regional estimates for non-partner sexual violence against females.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564625 URL: [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sardinha L., Maheu-Giroux M., Stöckl H., Meyer S.R., García-Moreno C. Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against females in 2018. Lancet. 2022;399(10327):803–813. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02664-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nesterko Y., Haase E., Schönfelder A., Glaesmer H. Suicidal ideation among recently arrived refugees in Germany. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):183. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-03844-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams A.C., Peña C.R., Rice A.S.C. Persistent pain in survivors of torture: a cohort study. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2010;40(5):715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aguirre N.G., Milewski A.R., Shin J., Ottenheimer D. Gender-based violence experienced by females seeking asylum in the United State: a lifetime of multiple traumas inflicted by multiple perpetrators. J Forensic Leg Med. 2020;72 doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2020.101959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keygnaert I., Vettenburg N., Temmerman M. Hidden violence is silent rape: sexual and gender-based violence in refugees, asylum seekers and undocumented migrants in Belgium and The Netherlands. Cult Health Sex. 2012;14(5):505–520. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.671961. Epub 2012 Apr 2. PMID: 22468763; PMCID: PMC3379780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belanteri R.A., Hinderaker S.G., Wilkinson E., et al. Sexual violence against migrants and asylum seekers. The experience of the MSF clinic on Lesvos Island, Greece. PLoS One. 2020;15(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pannetier J., Ravalihasy A., Lydié N., Lert F., Desgrées du Loû A., Parcours study group Prevalence and circumstances of forced sex and post-migration HIV acquisition in sub-Saharan African migrant females in France: an analysis of the ANRS-PARCOURS retrospective population-based study. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3(1):e16–e23. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Schrijver L., Nobels A., Harb J., et al. Victimization of applicants for international protection residing in Belgium: sexual violence and help-seeking behavior. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(19) doi: 10.3390/ijerph191912889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keygnaert I., Dias S.F., Degomme O., et al. Sexual and gender-based violence in the European asylum and reception sector: a perpetuum mobile? Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(1):90–96. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku066. Epub 2014 May 29. PMID: 24876179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lay M., Papadopoulos I. Sexual maltreatment of unaccompanied asylum-seeking minors from the Horn of Africa: a mixed method study focusing on vulnerability and prevention. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33(10):728–738. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Araujo J.O., de Souza F.M., Proença R., Bastos M.L., Trajman A., Faerstein E. Prevalence of sexual violence among refugees: a systematic review. Rev Saude Publica. 2019;53:78. doi: 10.11606/s1518-8787.2019053001081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalt A., Hossain M., Kiss L., Zimmerman C. Asylum seekers, violence and health: a systematic review of research in high-income host countries. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(3):e30–e42. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization . 2012. Understanding and addressing violence against women: overview; p. 8.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-RHR-12.35 URL: [Google Scholar]

- 20.Office Français de l'Immigration et de l'Intégration . 2021. Rapport d’activité annuel; p. 114.https://www.ofii.fr/wpcontent/uploads/2022/07/HR_RA_OFII_2021_21x297_p3_p114_compressed.pdf URL: [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amore K., Baker M., Howden-Chapman P. The ETHOS definition and classification of homelessness: an analysis. Eur J Homelessness. 2011;5 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ministère de l'Intérieur - Direction générale des étrangers en France - Direction de l’asile . 2020. Schéma national d’accueil des demandeurs d’asile et d’intégration des réfugiés 2021-2023; p. 24.https://www.immigration.interieur.gouv.fr/Asile/Schema-national-d-accueil-des-demandeurs-d-asile-et-d-integration-des-refugies-2021-2023 URL: [Google Scholar]

- 23.SÖChting I., Fairbrother N., Koch W.J. Sexual assault of females: prevention efforts and risk factors. Violence Against Women. 2004;10(1):73–93. [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization . 2014. Violence against females: intimate partner and sexual violence against females: intimate partner and sexual violence have serious short- and long-term physical, mental and sexual and reproductive health problems for survivors: fact sheet.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/112325 Report No.: WHO/RHR/14.11. URL: [Google Scholar]

- 25.Debauche A., Lebugle A., Brown E., et al. 2017. Présentation de l’enquête Virage et premiers résultats sur les violences sexuelles; p. 67.https://www.ined.fr/fr/publications/editions/document-travail/enquete-virage-premiers-resultats-violences-sexuelles/ Report No: 229. URL: [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borumandnia N., Khadembashi N., Tabatabaei M., Alavi Majd H. The prevalence rate of sexual violence worldwide: a trend analysis. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1835. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09926-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taffin M., Boudet Girard A., Gentile G., Khouani J., Jego-Sablier M. Représentations et attentes autour de la consultation avec le médecin généraliste par les demandeurs d’asile. Exercer. 2022;182:155–160. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nesterko Y., Schönenberg K., Glaesmer H. Sexual violence and mental health in male and female refugees newly arrived in Germany. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2021;118(8):130–131. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reese Masterson A., Usta J., Gupta J., Ettinger A.S. Assessment of reproductive health and violence against females among displaced Syrians in Lebanon. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14(1):25. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-14-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Office français de protection des refugies et des apatrides. Liste des pays d’origine sûrs. https://www.ofpra.gouv.fr/liste-des-pays-dorigine-surs URL:

- 31.Ministerial Statistical service of the French internal security Les violences sexuelles hors cadre familial enregistrées par les services de sécurité en. 2021. https://www.interieur.gouv.fr/Interstats/Actualites/Les-violences-sexuelles-hors-cadre-familial-enregistrees-par-les-services-de-securite-en-2021-Interstats-Analyse-n-52 URL:

- 32.World health organization . 2005. Researching Violence against Women; a practical guide for researchers and activists; p. 259.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42966 URL: [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.