Key Points

Question

How have the patterns of e-cigarette use changed after the initial disruption from the COVID-19 pandemic?

Finding

In this cross-sectional study of 414 755 respondents to the 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey, a high prevalence of e-cigarette use was observed among US adults, particularly among young adults aged 18 to 24 years (18%). Within the group aged 18 to 20 years, 72% of those who reported current e-cigarette use had no history of combustible cigarette use.

Meaning

These findings highlight the importance of continuous surveillance of tobacco consumption patterns given their dynamic and evolving characteristics, and they underscore the potential implications for policy formulation and regulation, especially concerning young adults.

This cross-sectional study uses data from the 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey to assess recent patterns in current and daily e-cigarette use among US adults.

Abstract

Importance

After the initial disruption from the COVID-19 pandemic, it is unclear how patterns of e-cigarette use in the US have changed.

Objective

To examine recent patterns in current and daily e-cigarette use among US adults in 2021.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study used data from the 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) database. The BRFSS is the largest national telephone-based survey of randomly sampled adults in the US. Adults aged 18 years or older, residing in 49 US states (all except Florida), the District of Columbia, and 3 US territories (Guam, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands), were included in the data set. Data analysis was performed in January 2023.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcome was age-adjusted prevalence of current and daily e-cigarette use overall and by participant characteristics, state, and territory. Descriptive statistical analysis was conducted, applying weights to account for population representation.

Results

This study included 414 755 BRFSS participants with information on e-cigarette use. More than half of participants were women (51.3%). In terms of race and ethnicity, 0.9% of participants were American Indian or Alaska Native, 5.8% were Asian, 11.5% were Black, 17.3% were Hispanic, 0.2% were Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, 62.2% were White, 1.4% were of multiple races or ethnicities, and 0.6% were of other race or ethnicity. Individuals aged 18 to 24 years comprised 12.4% of the study population. The age-standardized prevalence of current e-cigarette use was 6.9% (95% CI, 6.7%-7.1%), with almost half of participants using e-cigarettes daily (3.2% [95% CI, 3.1%-3.4%]). Among individuals aged 18 to 24 years, there was a consistently higher prevalence of e-cigarette use, with more than 18.6% reporting current use and more than 9.0% reporting daily use. Overall, among individuals reporting current e-cigarette use, 42.2% (95% CI, 40.7%-43.7%) indicated former combustible cigarette use, 37.1% (95% CI, 35.6%-38.6%) indicated current combustible cigarette use, and 20.7% (95% CI, 19.7%-21.8%) indicated never using combustible cigarettes. Although relatively older adults (aged ≥25 years) who reported current e-cigarette use were more likely to report former or current combustible cigarette use, younger adults (aged 18-24 years) were more likely to report never using combustible cigarettes. Notably, the proportion of individuals who reported current e-cigarette use and never using combustible cigarettes was higher in the group aged 18 to 20 years (71.5% [95% CI, 66.8%-75.7%]) compared with those aged 21 to 24 years (53.0% [95% CI, 49.8%-56.1%]).

Conclusion and Relevance

These findings suggest that e-cigarette use remained common during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly among young adults aged 18 to 24 years (18.3% prevalence). Notably, 71.5% of individuals aged 18 to 20 years who reported current e-cigarette use had never used combustible cigarettes. These results underscore the rationale for the implementation and enforcement of public health policies tailored to young adults.

Introduction

E-cigarettes are the second most commonly used tobacco product among US adults.1,2 Over the past 5 years, prevalence estimates of e-cigarette use have fluctuated across various surveys. However, these estimates have consistently remained greater than 3%, as demonstrated by data from both the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS).1,3,4,5,6 A concerning trend observed in 2 publications based on prior BRFSS data is the increasing proportion of individuals using e-cigarettes daily among those who reported use in the past 30 days over the same period. This finding suggests a potential shift from experimental to established use.5,6

Recent reports from the NHIS and the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) indicate that in 2021, the prevalence of e-cigarette use in the past 30 days was 4.5% and 6.0%, respectively.2,7 Across these surveys, adults aged younger than 35 years showed a notably higher prevalence of e-cigarette use. Similarly, National Youth Tobacco Survey data have consistently reported high e-cigarette use among middle and high school students for the past decade.8 Taken together, these findings suggest that adolescents who initiate e-cigarette use may continue into adulthood, leading to a potentially higher prevalence in young adults.

Although some studies suggest that e-cigarettes could serve as a smoking cessation aid for adults who use combustible cigarettes, their increased use among youths, young adults, and those with no prior exposure to combustible cigarettes continues to be a public health concern.6,9,10 The allure of and the increased use of e-cigarettes among these groups raise concerns about the potential risks of nicotine addiction, gateway effects, and long-term health implications of e-cigarette use, which have not been fully elucidated.11,12 Consequently, close monitoring of recent shifts in e-cigarette use within these populations is of importance.

The trajectory of e-cigarette use among US adults may have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. This health crisis, marked by an intensified focus on personal health and safety, may have contributed to changes in attitudes and behaviors relating to e-cigarette use.13 Psychological stress and isolation that may have arisen from lockdown measures also may have prompted some individuals to increasingly depend on e-cigarettes and other tobacco products as a coping mechanism.14,15 In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the conduct of surveys, especially those that relied on in-person data collection. As a result, surveys such as the NHIS transitioned from in-person to online interviews.16 Because the BRFSS is an online-based survey, its data collection was not notably affected by the lockdown measures implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic.17

It is important to provide up-to-date and comprehensive data on e-cigarette use, particularly among susceptible population groups. To address this need, we used the 2021 BRFSS to examine recent patterns of e-cigarette use among US adults. Our study analyzed recent e-cigarette use patterns among US adults to monitor existing policies and guide the development of strategies to address potential health risks and improve public health.

Methods

Study Population, Study Sample, and Study Design

The BRFSS is an extensive, nationally representative data set of health-related telephone survey data of noninstitutionalized US adults aged 18 years or older. The survey uses iterative proportional fitting for weighting, adjusting for demographic differences, noncoverage, and nonresponse to ensure data representativeness.18 For this cross-sectional study, we used data from the 2021 BRFSS survey, with a survey response rate of 44.0%.19 Verbal consent was obtained during initial contact and screening. In 2021, 50 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands collected data via landline and cellular telephones.17 However, Florida did not collect data for sufficient months in 2021 to meet the inclusion criteria for the annual aggregate data set.17 We analyzed data from 414 755 participants (94.6% of the surveyed population) who provided information on e-cigarette use. Johns Hopkins School of Medicine deemed our study exempt from review because deidentified publicly available BRFSS data were used consistent with the Common Rule. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Assessment of E-Cigarette and Combustible Cigarette Use

E-cigarette use was assessed with this question: “Do you now use e-cigarettes or other electronic vaping products every day, some days, or not at all?” Participants who responded “every day” or “some days” were considered to be currently using e-cigarettes. Individuals who were currently using e-cigarettes and responded “every day” were classified as using e-cigarettes daily.

Combustible cigarette use was determined using 2 questions: “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” and “Do you now smoke cigarettes every day, some days, or not at all?” Respondents answering “yes” to the first question but “no” to the second were classified as having formerly used combustible cigarettes. If they answered “yes” to both questions, they were categorized as currently using combustible cigarettes. A “no” response to the first question indicated they had never used combustible cigarettes.

Other Study Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics included age, sex, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation (heterosexual, lesbian or gay, or bisexual), transgender identity (yes or no), marital status (married, divorced, widowed, single, or member of an unmarried couple), education level (less than high school, high school or some college, or college graduate), employment status (employed, unemployed, student, or retired), area of residence (rural or urban), and pregnant (yes or no). Race and ethnicity were reported as American Indian or Alaska Native, Hispanic, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic Asian (hereinafter, Asian), non-Hispanic Black (hereinafter, Black), non-Hispanic White (hereinafter, White), multiple races or ethnicities, or other race or ethnicity (specific groups in the last category were not itemized in the 2021 BRFSS data set). Household income level was based on the 2021 federal poverty line.20 Weight and height were self-reported; body mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Chronic health conditions assessed included cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer (excluding skin cancer), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (yes or no), and depression (yes or no). Cardiovascular disease was defined as a composite of myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease, or stroke. All measures were self-reported.

Statistical Analysis

We summarized participant sociodemographics and chronic health conditions using proportions for the entire sample and for those reporting current and daily e-cigarette use. We calculated the age-standardized prevalence of current and daily e-cigarette use overall, within subgroups including combustible cigarette use categories (never, former, or current), and across age groups.

To understand tobacco use patterns, we analyzed the prevalence of combustible cigarette use among those reporting current and daily e-cigarette use. In addition, we explored different patterns of current e-cigarette and combustible use, including sole e-cigarette use, dual use, and exclusive combustible cigarette use. Finally, we estimated the age-standardized prevalence of e-cigarette use by state, allowing for comparisons while adjusting for variations in age distribution.

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata, version 16 (StataCorp LLC). We calculated weighted prevalence estimates using the BRFSS analytic recommendations.21 We used the BRFSS complex sampling design and participant weights for population-representative estimates. The weighted sample sizes ensured that our results mirrored population trends. Age standardization used the 2010 US Census for groups aged 18 to 24 through 55 to 59 years and 60 years or older, aiding in identifying age-standardized prevalence of e-cigarette use by participant attributes. We employed the survey command svy to account for the complex weighting method used by the BRFSS. Statistical significance was set at a 2-sided P < .05. Data analysis was performed in January 2023.

Results

Study Population

This study included 414 755 adults; 48.7% were men and 51.3% were women. Individuals aged 18 to 24 years comprised 12.4% of the study population. A total of 0.9% of participants identified as American Indian or Alaska Native, 5.8% as Asian, 11.5% as Black, 17.3% as Hispanic, 0.2% as Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, 62.2% as White, 1.4% as multiple races or ethnicities, and 0.6% as other race or ethnicity (Table 1). In the overall study sample, the proportion of individuals who reported current and daily e-cigarette use was higher among male, bisexual, transgender, and single individuals (Table 1).

Table 1. Participant Characteristics Overall and Among Those Who Reported Current and Daily E-Cigarette Use, 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

| Variable | No. (weighted %) of participants | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 414 755) | Current e-cigarette use (n = 19 346) | Daily e-cigarette use (n = 9050) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 192 435 (48.7) | 10 563 (57.0) | 5002 (57.3) |

| Female | 222 328 (51.3) | 8783 (43.0) | 4735 (42.7) |

| Age, y | |||

| 18-20 | 9774 (5.6) | 1948 (15.3) | 896 (14.0) |

| 21-24 | 14 824 (6.8) | 2828 (19.2) | 1341 (20.0) |

| 25-29 | 20 397 (7.8) | 2573 (15.9) | 1235 (15.7) |

| 30-34 | 24 206 (9.8) | 2266 (13.6) | 1093 (13.5) |

| 35-39 | 26 841 (7.8) | 1961 (8.4) | 899 (8.3) |

| 40-44 | 27 661 (8.6) | 1563 (7.9) | 777 (8.5) |

| 45-49 | 26 840 (6.5) | 1191 (4.4) | 556 (4.4) |

| 50-54 | 32 128 (8.2) | 1125 (4.6) | 531 (4.8) |

| 55-59 | 35 980 (7.8) | 1067 (3.8) | 483 (4.0) |

| ≥60 | 188 084 (31.1) | 2606 (7.0) | 1145 (6.8) |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 6838 (0.9) | 411 (1.2) | 151 (0.8) |

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 10 514 (5.8) | 521 (4.9) | 212 (3.2) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 30 150 (11.5) | 1085 (9.1) | 356 (6.7) |

| Hispanic | 35 929 (17.3) | 1930 (15.2) | 751 (11.8) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1846 (0.2) | 4.9 (3.3-7.2) | 50.3 (33.4-67.1) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 307 582 (62.2) | 13 862 (66.2) | 6884 (74.1) |

| Multiple | 8760 (1.4) | 778 (2.4) | 358 (2.4) |

| Othera | 3599 (0.6) | 185 (0.5) | 77 (0.5) |

| Sexual orientation | |||

| Heterosexual | 214 530 (92.4) | 9212 (82.3) | 4373 (80.1) |

| Lesbian or gay | 4303 (2.0) | 398 (3.9) | 202 (4.6) |

| Bisexual | 6569 (3.7) | 1024 (10.6) | 493 (11.6) |

| Other | 3388 (1.8) | 313 (3.3) | 174 (3.7) |

| Transgender | |||

| No | 231 762 (99.2) | 10 860 (98.3) | 5153 (97.8) |

| Yes | 1453 (0.8) | 180 (1.7) | 93 (2.2) |

| BMI | |||

| <18.5 | 6111 (1.9) | 561 (3.7) | 296 (4.5) |

| ≥18.5 to <25 | 112 883 (30.6) | 6322 (36.7) | 2889 (35.0) |

| ≥25 to <30 | 135 644 (34.4) | 5796 (30.4) | 2641 (29.9) |

| ≥30 | 128 782 (33.1) | 5767 (29.2) | 2810 (30.6) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 215 226 (50.4) | 5728 (27.3) | 2859 (29.8) |

| Divorced or separated | 60 789 (12.8) | 3129 (12.4) | 1452 (12.1) |

| Widowed | 45 030 (0.9) | 776 (2.4) | 321 (2.6) |

| Single | 65 309 (24.7) | 7655 (47.6) | 3382 (43.6) |

| Highest education level | |||

| Less than high school | 24 227 (11.9) | 1383 (11.7) | 585 (10.8) |

| High school or some college | 218 749 (57.8) | 13 360 (72.6) | 6504 (75.1) |

| College graduate | 169 978 (30.3) | 4543 (15.7) | 1937 (14.0) |

| Income, poverty line, % | |||

| <100 | 34 517 (11.0) | 2444 (12.8) | 957 (9.6) |

| 100-200 | 67 367 (17.2) | 4353 (21.8) | 2086 (22.0) |

| >200 | 308 410 (71.8) | 12 345 (65.4) | 5911 (68.4) |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 212 866 (57.2) | 12 410 (66.1) | 6134 (70.0) |

| Unemployed | 61 437 (17.9) | 3957 (19.9) | 1707 (18.6) |

| Student | 10 217 (5.1) | 1216 (9.4) | 452 (6.7) |

| Retired | 126 605 (19.9) | 1595 (4.7) | 684 (4.7) |

| Area of residence | |||

| Rural | 59 348 (6.5) | 2203 (6.3) | 1018 (6.6) |

| Urban | 348 554 (93.5) | 16 913 (93.7) | 7937 (93.4) |

| Combustible cigarette use | |||

| Never | 245 395 (62.9) | 5322 (32.8) | 1848 (24.8) |

| Former | 112 749 (23.7) | 7310 (36.1) | 4846 (50.9) |

| Current | 53 547 (13.4) | 6552 (31.1) | 2282 (24.4) |

| Pregnant | |||

| No | 75 227 (96.6) | 5984 (98.1) | 2798 (97.2) |

| Yes | 2297 (3.4) | 91 (1.9) | 47 (2.8) |

| Chronic health condition | |||

| CVDb | |||

| No | 365 624 (91.6) | 17 868 (95.0) | 8432 (94.8) |

| Yes | 44 714 (8.4) | 1284 (5.0) | 553 (5.2) |

| Cancer | |||

| No | 373 099 (92.9) | 18 257 (96.4) | 8557 (96.2) |

| Yes | 40 507 (7.1) | 1023 (3.6) | 462 (3.8) |

| COPD | |||

| No | 380 259 (93.5) | 17 451 (93.1) | 8216 (93.3) |

| Yes | 32 636 (6.5) | 1786 (6.9) | 793 (6.7) |

| Asthma | |||

| No | 354 658 (85.3) | 15 336 (79.0) | 7208 (78.8) |

| Yes | 58 564 (14.7) | 3903 (21.0) | 1790 (21.2) |

| Depression | |||

| No | 330 584 (80.1) | 11 814 (62.4) | 5279 (59.7) |

| Yes | 81 959 (19.9) | 7378 (37.6) | 3698 (40.3) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Specific groups within the other race and ethnicity category were not itemized in the 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data set.

Composite of myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease, and/or stroke.

Patterns of E-Cigarette Use Among US Adults Overall and by Sociodemographic Characteristics

The age-standardized prevalence of current and daily e-cigarette use was 6.9% (95% CI, 6.7%-7.1%; weighted sample approximately 15 million) and 3.2% (95% CI, 3.1%-3.4%; weighted sample approximately 7 million), respectively (Table 2). Among individuals who reported current e-cigarette use, the proportion of daily use, as a measure of established use and possible nicotine addiction, was 46.6% (95% CI, 45.3%-48.0%) (Table 2 and eTable 1 in Supplement 1).

Table 2. Age-Standardized Weighted Prevalence of E-Cigarette Use (Current and Daily) Among US Adults, 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

| Variable | Age-standardized weighted prevalence, % (95% CI) | Daily-to-current use ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current e-cigarette use | Daily e-cigarette use | ||

| Total population (N = 414 755) | 6.9 (6.7-7.1) | 3.2 (3.1-3.4) | 46.6 (45.3-48.0) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 7.8 (7.6-8.1) | 3.7 (3.5-3.9) | 46.9 (45.1-48.7) |

| Female | 6.0 (5.7-6.2) | 2.8 (2.6-2.9) | 46.3 (44.1-48.4) |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 8.7 (7.4-10.1) | 2.9 (2.3-3.7) | 33.6 (26.8-41.2) |

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 4.7 (3.9-5.6) | 1.5 (1.1-2.0) | 30.3 (23.4-38.3) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 5.5 (5.0-6.0) | 1.9 (1.6-2.2) | 34.3 (30.0-38.9) |

| Hispanic | 4.6 (4.3-5.0) | 1.7 (1.5-1.9) | 36.2 (32.0-40.5) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 10.7 (7.8-14.6) | 4.9 (3.3-7.2) | 50.3 (33.4-67.1) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 8.2 (8.0-8.5) | 4.3 (4.1-4.5) | 52.1 (50.6-53.6) |

| Multiple | 9.5 (8.2-10.9) | 4.2 (3.5-5.1) | 45.5 (38.9-52.3) |

| Othera | 6.9 (5.4-8.8) | 2.8 (2.0-3.9) | 42.4 (30.9-54.7) |

| Sexual orientation | |||

| Heterosexual | 6.8 (6.6-7.1) | 3.2 (3.0-3.3) | 46.1 (44.2-48.1) |

| Lesbian or gay | 10.7 (9.1-12.6) | 5.7 (4.4-7.5) | 55.8 (46.4-64.7) |

| Bisexual | 12.2 (11.0-13.7) | 6.5 (5.4-7.8) | 52.0 (46.8-57.1) |

| Other | 10.5 (8.4-13.2) | 5.9 (4.0-8.6) | 53.5 (42.9-63.9) |

| Transgender | |||

| No | 7.1 (6.9-7.4) | 3.4 (3.2-3.5) | 47.1 (45.3-48.9) |

| Yes | 12.3 (9.3-16.3) | 7.2 (4.6-11.1) | 61.5 (48.1-73.3) |

| BMI | |||

| <18.5 | 9.8 (8.3-11.5) | 4.9 (4.0-5.9) | 56.6 (48.4-64.4) |

| ≥18.5 to <25 | 7.2 (6.9-7.6) | 3.2 (3.0-3.5) | 44.4 (41.9-46.8) |

| ≥25 to <30 | 7.1 (6.7-7.4) | 3.2 (3.0-3.5) | 45.8 (43.4-48.3) |

| ≥30 | 7.0 (6.7-7.4) | 3.4 (3.2-3.6) | 48.7 (46.3-51.1) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 5.3 (4.9-5.7) | 2.8 (2.5-3.1) | 51.0 (48.4-53.5) |

| Divorced or separated | 10.0 (8.6-11.5) | 4.5 (3.9-5.3) | 45.6 (42.2-49.0) |

| Widowed | 11.8 (8.7-15.8) | 7.8 (5.1-11.7) | 50.4 (42.0-58.8) |

| Single | 7.6 (7.2-8.0) | 3.2 (2.9-3.4) | 42.7 (40.7-44.8) |

| Highest education level | |||

| Less than high school | 7.3 (6.7-8.0) | 3.2 (2.7-3.7) | 43.2 (38.6-48.0) |

| High school or some college | 8.3 (8.0-8.5) | 4.0 (3.8-4.2) | 48.3 (46.7-49.9) |

| College graduate | 4.2 (4.0-4.5) | 1.7 (1.5-1.8) | 41.6 (39.1-44.3) |

| Income, poverty line, % | |||

| <100 | 7.1 (6.6-7.7) | 2.5 (2.2-2.8) | 35.0 (31.4-38.9) |

| 100-200 | 8.3 (7.9-8.8) | 3.9 (3.6-4.2) | 46.9 (44.3-49.6) |

| >200 | 7.7 (6.6-9.0) | 3.2 (2.5-4.1) | 48.7 (47.0-50.5) |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 7.2 (7.0-7.4) | 3.6 (3.4-3.7) | 49.4 (47.7-51.1) |

| Unemployed | 8.0 (7.5-8.5) | 3.5 (3.1-3.9) | 43.6 (40.6-46.7) |

| Student | 9.1 (6.6-12.4) | 4.2 (2.4-7.3) | 33.6 (29.4-38.1) |

| Retired | 13.9 (9.3-20.3) | 9.4 (5.0-16.8) | 46.8 (40.8-53.0) |

| Area of residence | |||

| Rural | 7.9 (7.2-8.7) | 3.9 (3.3-4.5) | 48.8 (44.2-53.4) |

| Urban | 6.9 (6.7-7.1) | 3.2 (3.1-3.4) | 46.5 (45.1-48.0) |

| Combustible cigarette use | |||

| Never | 2.9 (2.8-3.1) | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | 35.2 (32.9-37.7) |

| Former | 17.2 (16.5-18.0) | 11.6 (10.9-12.3) | 65.8 (63.4-68.1) |

| Current | 17.9 (17.1-18.7) | 6.9 (6.3-7.4) | 36.5 (34.2-38.8) |

| Pregnant | |||

| No | 8.8 (8.4-9.3) | 4.0 (3.8-4.3) | 45.6 (43.1-48.1) |

| Yes | 5.4 (3.1-9.2) | 2.8 (1.6-4.7) | 67.1 (50.7-80.2) |

| Chronic health condition | |||

| CVDb | |||

| No | 6.8 (6.6-7.0) | 3.2 (3.1-3.3) | 46.7 (45.3-48.1) |

| Yes | 10.7 (8.9-12.9) | 5.5 (3.9-7.6) | 48.3 (42.4-54.3) |

| Cancer | |||

| No | 6.9 (6.7-7.1) | 3.2 (3.1-3.3) | 46.5 (45.1-47.9) |

| Yes | 9.8 (7.9-12.2) | 5.8 (4.0-8.3) | 49.4 (43.2-55.7) |

| COPD | |||

| No | 6.7 (6.5-6.9) | 3.1 (3.0-3.3) | 46.8 (45.4-48.3) |

| Yes | 11.7 (10.5-12.9) | 5.1 (4.4-6.0) | 45.1 (40.8-49.4) |

| Asthma | |||

| No | 6.5 (6.4-6.7) | 3.0 (2.9-3.2) | 46.5 (44.9-48.0) |

| Yes | 8.8 (8.3-9.3) | 4.1 (3.8-4.5) | 47.1 (44.3-50.0) |

| Depression | |||

| No | 5.6 (5.4-5.8) | 2.5 (2.4-2.6) | 44.6 (42.9-46.3) |

| Yes | 11.7 (11.2-12.2) | 5.8 (5.5-6.2) | 50.1 (47.8-52.4) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Specific groups within the other race and ethnicity category were not itemized in the 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data set.

Composite of myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease, and/or stroke.

Compared with heterosexual individuals, persons who identified as bisexual had a higher prevalence of current e-cigarette use (12.2% [95% CI, 11.0%-13.7%] vs 6.8% [95% CI, 6.6%-7.1%]) and daily e-cigarette use (6.5% [95% CI, 5.4%-7.8%] vs 3.2% [95% CI, 3.0%-3.3%]). Similarly, compared with cisgender individuals, those who identified as transgender reported a higher prevalence of current e-cigarette use (12.3% [95% CI, 9.3%-16.3%] vs 7.1% [95% CI, 6.9%-7.4%]) and daily e-cigarette use (7.2% [9.5% CI, 4.6%-11.1%] vs 3.4% [95% CI, 3.2%-3.5%]). Compared with individuals without the respective comorbid condition, the prevalence of current e-cigarette use was higher among those with cardiovascular disease (10.7% [95% CI, 8.9%-12.9%] vs 6.8% [95% CI, 6.6%-7.0%]), cancer (9.8% [95% CI, 7.9%-12.2%] vs 6.9% [95% CI, 6.7%-7.1%]), asthma (8.8% [95% CI, 8.3%-9.3%] vs 6.5% [95% CI, 6.4%-6.7%]), and depression (11.7% [95% CI, 11.2%-12.2%] vs 5.6% [95% CI, 5.4%-5.8%]) (Table 2).

Among individuals who reported current e-cigarette use (daily-to-current use ratio), the proportion who used e-cigarettes daily was considerably higher among non-Hispanic White, lesbian or gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals, as well as among those who formerly smoked combustible cigarettes, compared with their respective comparison groups (Table 2).

The age-standardized prevalence of current e-cigarette use among individuals who reported never using combustible cigarettes was 2.9% (95% CI, 2.8%-3.1%). The prevalence was higher among individuals who reported former combustible cigarette use, at 17.2% (95% CI, 16.5%-18.0%), and current combustible cigarette use, at 17.9% (95% CI, 17.1%-18.7%). The age-standardized prevalence of daily e-cigarette use by smoking status showed similar patterns (Table 2).

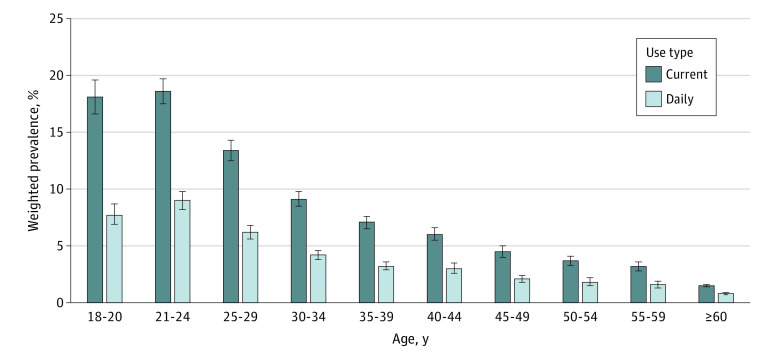

Table 3 demonstrates the prevalence of current and daily e-cigarette use across age groups and by combustible cigarette use. The prevalence of current e-cigarette use decreased with increasing age and was highest among young adults aged 18 to 20 years (18.1% [95% CI, 16.6%-19.6%]) and 21 to 24 years (18.6% [95% CI, 17.5%-19.7%]) (Figure and Table 3).

Table 3. Weighted Prevalence of E-Cigarette Use (Current and Daily) by Combustible Cigarette Use (Never, Former, and Current) Across Age Groups, 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

| Age group, y | Weighted prevalence, % (95% CI) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | Never combustible cigarette use | Former combustible cigarette use | Current combustible cigarette use | |||||

| Current | Daily | Current | Daily | Current | Daily | Current | Daily | |

| 18-20 | 18.1 (16.6-19.6) | 7.7 (6.9-8.7) | 13.9 (12.7-15.3) | 5.5 (4.8-6.4) | 63.1 (52.3-72.7) | 36.0 (26.7-46.6) | 67.4 (59.7-74.4) | 29.5 (23.6-36.2) |

| 21-24 | 18.6 (17.5-19.7) | 9.0 (8.2-9.8) | 11.8 (10.9-12.9) | 4.5 (3.9-5.2) | 53.8 (49.0-58.5) | 39.8 (35.1-44.6) | 45.3 (40.6-50.1) | 20.2 (17.0-23.9) |

| 25-29 | 13.4 (12.5-14.3) | 6.2 (5.6-6.8) | 5.9 (5.2-6.7) | 1.6 (1.3-1.9) | 33.7 (30.6-36.9) | 21.8 (19.4-24.4) | 30.3 (27.0-33.8) | 13.1 (10.6-16.1) |

| 30-34 | 9.1 (8.5-9.8) | 4.2 (3.8-4.6) | 2.6 (2.2-3.1) | 0.8 (0.6-1.1) | 22.1 (20.1-24.2) | 13.8 (12.2-15.4) | 19.2 (17.1-21.4) | 6.4 (5.4-7.7) |

| 35-39 | 7.1 (6.5-7.6) | 3.2 (2.9-3.6) | 1.6 (1.2-2.1) | 0.4 (0.3-0.6) | 15.1 (13.5-16.7) | 10.0 (8.7-11.4) | 16.5 (14.6-18.5) | 5.0 (3.8-6.5) |

| 40-44 | 6.0 (5.5-6.6) | 3.0 (2.6-3.5) | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) | 0.4 (0.2-0.7) | 12.4 (10.9-14.1) | 8.5 (7.3-9.9) | 13.8 (12.1-15.8) | 4.3 (3.2-5.8) |

| 45-49 | 4.5 (4.0-5.0) | 2.1 (1.8-2.4) | 0.9 (0.6-1.2) | 0.2 (0.1-0.4) | 8.4 (7.3-9.7) | 6.2 (5.2-7.3) | 12.7 (10.7-15.0) | 3.5 (2.5-4.8) |

| 50-54 | 3.7 (3.3-4.1) | 1.8 (1.5-2.2) | 0.5 (0.3-0.7) | 0.1 (0.1-0.2) | 8.0 (6.6-9.5) | 5.5 (4.3-6.9) | 10.1 (8.6-11.8) | 3.4 (2.5-4.7) |

| 55-59 | 3.2 (2.8-3.6) | 1.6 (1.3-1.9) | 0.4 (0.3-0.6) | 0.1 (0.1-0.2) | 6.3 (5.3-7.4) | 4.0 (3.2-5.1) | 8.2 (6.9-9.6) | 2.8 (2.1-3.9) |

| ≥60 | 1.5 (1.4-1.6) | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | 0.4 (0.3-0.5) | 0.1 (0.2-0.4) | 2.0 (1.7-2.2) | 1.1 (1.0-1.3) | 5.2 (4.6-5.9) | 1.8 (1.4-3.9) |

Figure. Weighted Prevalence of E-Cigarette Use Among US Adults, 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Distribution of Combustible Cigarette Use Among Individuals Who Reported Current and Daily E-Cigarette Use

Among individuals who reported current e-cigarette use, 20.7% (95% CI, 19.7%-21.8%) reported never using combustible cigarettes, 42.2% (95% CI, 40.7%-43.7%) reported former combustible cigarette use, and 37.1% (95% CI, 35.6%-38.6%) reported current combustible cigarette use (Table 4). These proportions varied widely by age group. Notably, the proportion who reported never using combustible cigarettes among those who reported current e-cigarette use was highest among individuals aged 18 to 20 years (71.5% [95% CI, 66.8%-75.7%]), followed by individuals aged 21 to 24 years (53.0% [95% CI, 49.8%-56.1%]) (Table 4 and eFigure 1 in Supplement 1). Similarly, the proportion of individuals reporting never using combustible cigarettes among those who reported daily e-cigarette use was highest among young adults aged 18 to 20 years (66.5% [95% CI, 61.2%-71.4%]) (Table 4).

Table 4. Distribution of Combustible Cigarette Use (Never, Former, and Current) Among Individuals Who Use E-Cigarettes (Current and Daily) Across Age Groups, 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

| Age group, y | Weighted prevalence of combustible cigarette use, % (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Never combustible cigarette use | Former combustible cigarette use | Current combustible cigarette use | |

| Current e-cigarette use | |||

| Total population | 20.7 (19.7-21.8) | 42.2 (40.7-43.7) | 37.1 (35.6-38.6) |

| 18-20 | 71.5 (66.8-75.7) | 13.2 (9.5-18.2) | 15.3 (12.9-18.1) |

| 21-24 | 53.0 (49.8-56.1) | 26.0 (23.2-29.0) | 21.0 (18.6-23.6) |

| 25-29 | 32.0 (28.8-35.4) | 37.6 (34.2-41.1) | 30.4 (27.0-34.0) |

| 30-34 | 18.5 (15.8-21.7) | 45.9 (42.4-49.6) | 35.5 (32.1-39.1) |

| 35-39 | 14.0 (10.9-17.8) | 44.6 (40.6-48.7) | 41.4 (37.3-45.5) |

| 40-44 | 10.0 (7.3-13.6) | 49.0 (44.3-53.8) | 41.0 (36.4-45.7) |

| 45-49 | 12.0 (9.0-15.8) | 41.3 (36.2-46.5) | 46.7 (41.3-52.3) |

| 50-54 | 8.1 (5.6-11.7) | 47.5 (41.6-53.5) | 44.4 (38.7-50.2) |

| 55-59 | 8.1 (6.0-10.7) | 49.0 (43.3-54.6) | 43.0 (37.5-48.7) |

| ≥60 | 14.5 (12.0-17.5) | 46.9 (42.9-51.0) | 38.6 (34.6-42.6) |

| Daily e-cigarette use | |||

| Total population | 14.7 (13.6-16.0) | 58.1 (55.8-60.4) | 27.2 (25.0-29.4) |

| 18-20 | 66.5 (61.2-71.4) | 17.8 (14.0-22.2) | 15.7 (12.4-19.7) |

| 21-24 | 41.2 (36.6-45.9) | 39.6 (35.0-44.4) | 19.3 (16.2-22.8) |

| 25-29 | 18.6 (15.3-22.4) | 52.9 (47.8-57.9) | 28.5 (23.7-33.9) |

| 30-34 | 12.4 (9.4-16.2) | 61.9 (57.1-66.4) | 25.7 (21.9-30.0) |

| 35-39 | 8.5 (6.0-11.8) | 64.2 (57.9-70.0) | 27.4 (21.8-33.8) |

| 40-44 | 7.8 (4.4-13.4) | 66.7 (59.5-73.2) | 25.5 (19.7-32.4) |

| 45-49 | 7.4 (4.3-12.5) | 65.2 (57.1-72.5) | 27.3 (20.5-35.5) |

| 50-54 | 4.1 (2.5-6.6) | 65.8 (56.9-73.8) | 30.1 (22.5-39.1) |

| 55-59 | 4.8 (2.6-8.7) | 64.5 (55.7-72.5) | 30.7 (23.1-39.5) |

| ≥60 | 9.5 (6.8-13.3) | 60.2 (53.8-66.3) | 30.2 (24.4-36.8) |

Patterns of E-Cigarette and Combustible Cigarette Use

The prevalence of sole e-cigarette, exclusive combustible cigarette, and dual e-cigarette and combustible cigarette use was 4.7% (95% CI, 4.6%-4.9%), 11.7% (95% CI, 11.4%-11.9%), and 2.2% (95% CI, 2.1%-2.3%), respectively. The prevalence differed across age groups, with a higher prevalence of sole e-cigarette use among younger age groups (18-20 years: 15.2% [95% CI, 13.9%-16.7%]; and 21-24 years: 14.6% [95% CI, 13.6%-15.6%]) (eTable 2 and eFigure 2 in Supplement 1). Similarly, the prevalence of dual e-cigarette and combustible cigarette use was higher in younger age groups, with the highest prevalence seen among individuals aged 25 to 29 years (4.0% [95% CI, 3.5%-4.6%]), followed by individuals aged 21 to 24 years (3.9% [95% CI, 3.4%-4.4%]). In contrast, the prevalence of exclusive combustible cigarette use was higher among the older age groups aged 55 to 59 years (15.5% [95% CI, 14.7%-16.3%]) compared with those aged 18 to 20 years (1.3% [95% CI, 1.0%-1.8%]) (eTables 2 and 3 in Supplement 1).

Prevalence of E-Cigarette Use by State

eTable 3 and eFigure 3 in Supplement 1 show the state-specific age-standardized prevalence of e-cigarette use. Southern, western, and midwestern states generally had a higher prevalence of current e-cigarette use compared with other states, except for California (5.2% [95% CI, 4.5%-5.9%]) and Minnesota (5.7% [95% CI, 5.2%-6.2%]). Northeastern states generally had a lower prevalence of current e-cigarette use, except for Delaware (6.1% [95% CI, 5.1%-7.4%]), New Jersey (6.0% [95% CI, 5.2%-6.8%]), Pennsylvania (6.1% [95% CI, 5.3%-7.0%]), and Rhode Island (6.2% [95% CI, 5.1%-7.4%]). In the US territories, the prevalence varied widely from 2.0% (95% CI, 1.5%-2.7%) in Puerto Rico to 11.1% in Guam (95% CI, 8.8%-14.0%).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study using a large, nationally representative sample of the US population, we report the prevalence and distribution of e-cigarette use among adults aged 18 years or older in 2021, providing national and state-level prevalence estimates. Overall, 6.9% of participants reported current e-cigarette use, whereas 3.2% reported daily e-cigarette use. Among individuals who reported current e-cigarette use, almost half (46.6%) reported daily e-cigarette use. The prevalence of current e-cigarette use was highest among young adults aged 18 to 20 and 21 to 24 years, with 71.5% of the former group having no history of combustible cigarette use. E-cigarette use was more prevalent among men; persons who identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender; individuals who lived in rural areas; and those with a chronic health condition. Similar to prior studies, state-level prevalence estimates remained heterogenous, with the southern and western states generally having a higher prevalence of e-cigarette use compared with other regions.22

The age-standardized prevalence estimates of e-cigarette use from this study differed from that reported in the 2021 NHIS. According to the NHIS data, the prevalence of e-cigarette use among adults aged 18 years or older was 4.5%.23 This variation in estimates may likely be attributed to differences in survey methodologies, sampling variability, and timing of data collection between data sets. Whereas the BRFSS is solely an online survey, the NHIS involves in-person interviews and physical examinations.16,24 However, the COVID-19 pandemic prompted the NHIS to shift from in-person to online interviews. This sudden methodological change, along with sampling variability and timing, might explain the discrepancies in e-cigarette use prevalence estimates.25

Our data suggest that the prevalence of current e-cigarette use is higher than that reported in prior years. Based on BRFSS data, the prevalence of current e-cigarette use varied between 4.6% to 5.4% between 2016 and 2018.5,6 The higher prevalence of e-cigarette use observed in 2021 may have been due to changes that occurred during the pandemic, such as increased online sales, which facilitated easy accessibility and concomitant stockpiling.26,27 Moreover, the heightened psychosocial stress experienced during the pandemic may have resulted in more individuals turning to e-cigarettes as a coping mechanism.28,29

We observed a high proportion (71.5%) of individuals aged 18 to 20 years who reported current e-cigarette use without concurrent use of combustible cigarettes. This proportion is numerically higher than those observed in prior BRFSS years (63.3% in 2017, 66.1% in 2018, and 70.4% in 2020).5,6 Perceived reduced harm, easy access, and social preference for e-cigarettes over other tobacco products may explain the high e-cigarette prevalence among young adults.30,31,32,33 Also, with nearly one-half of individuals (46.6%) currently using e-cigarettes reporting daily use, there is an implication of a shift from experimental to established use. This observation aligns with patterns observed in prior BRFSS years (34.5% in 2017, 37.3% in 2018, and 44.4% in 2020),5,6 albeit with numerically higher findings in our study.

Daily e-cigarette use is linked to nicotine dependence and initiating combustible smoking in tobacco-naive adolescents34,35 while also increasing quit rates and reducing cigarette use among established smokers.10,36 The dual nature of the effects of e-cigarette use, influencing both initiation and cessation of combustible cigarettes, may help contextualize the importance of the limited overall total population-wide prevalence (<1%) yet substantial number of young adults using e-cigarettes daily without prior combustible cigarette use. It is, however, conceivable that in the absence of e-cigarettes, some young adults may have taken up or continued to use combustible cigarettes.

The observed variation in e-cigarette use prevalence across different states might potentially stem from a range of state-specific factors. Such factors may encompass the timing and response to the COVID-19 pandemic, socioeconomic conditions, stringency of tobacco regulatory policies, and the degree to which excise taxes on e-cigarette devices are enforced in these jurisdictions.37 These aspects are not isolated; they interact and may influence each other, potentially accounting for the heterogeneity in the prevalence rates across states.

There seem to be many implications of our data for policy and public health, particularly for those aged 18 to 20 years. Some researchers have viewed data such as ours as a reflection of mental health, considering the interplay of stress and substance use, and as a call for tighter regulation of existing policies, such as Tobacco 21 legislation and the e-cigarette flavor ban, considering the high prevalence of e-cigarette use among young adults.29,38 Others have suggested that tighter control of online purchases may limit e-cigarette use among young adults.26 Furthermore, our study highlights the importance of collecting and analyzing data continuously, as they play a vital role in monitoring epidemiologic shifts and informing policies.39 These data should be consistently repeated and compared across surveys to ensure accurate and up-to-date information.39

Limitations

This study has certain limitations. First, it relied on self-reported data, which introduces the potential for misclassification or recall bias. In addition, social desirability and recall bias may have resulted in underreporting of both e-cigarette use and smoking status. It is important to note that these data provide a snapshot of e-cigarette use specifically in 2021, and assessing the overall impact of the entire COVID-19 pandemic on e-cigarette use presents challenges. Although COVID-19 affected our findings, its exact association with the prevalence of e-cigarette use is unclear. Future studies should assess pandemic-specific factors, such as lockdown effects on e-cigarette availability and use. Longitudinal data during the pandemic can provide insights into evolving behaviors.

Conclusions

This cross-sectional study highlights a high prevalence of e-cigarette use among adults in the US, particularly among young adults, in 2021. A striking finding is that 71.5% of those aged 18 to 20 years who reported e-cigarette use had no prior history of combustible cigarette use—this number is numerically higher compared with prior BRFSS data. Another notable observation was the high proportion of daily use among persons who reported current e-cigarette use, indicating a possible transition toward established use and potential nicotine dependence. These findings are of value to the tobacco regulatory science community and to policy makers, and they underscore the rationale for the implementation and enforcement of public health policies tailored to young adults.

eTable 1. Weighted Sample Size by Participant Characteristics

eTable 2. Weighted Prevalence of Current Sole E-Cigarette, Dual (E-Cigarette and Combustible Cigarette), and Exclusive Combustible Cigarette Use Across Age Groups, 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

eTable 3. Age-Standardized Weighted Prevalence of E-Cigarette Use (Current and Daily) Across US States, 2019 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

eFigure 1. Proportion of Current E-Cigarette Use Among Individuals With No Smoking History

eFigure 2. Patterns of E-Cigarette and Combustible Cigarette Use by Age, 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

eFigure 3. Prevalence of Current E-Cigarette Use by State, 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Wang TW, Jamal A, Homa DM. Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(11):397-405. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7111a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Jamal A, et al. Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(18):475-483. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7218a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Creamer MR, Wang TW, Babb S, et al. Tobacco product use and cessation indicators among adults—United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(45):1013-1019. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6845a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornelius ME, Wang TW, Jamal A, Loretan CG, Neff LJ. Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(46):1736-1742. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6946a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boakye E, Osuji N, Erhabor J, et al. Assessment of patterns in e-cigarette use among adults in the US, 2017-2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(7):e2223266. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.23266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obisesan OH, Osei AD, Uddin SMI, et al. Trends in e-cigarette use in adults in the United States, 2016-2018. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(10):1394-1398. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . 2021 NSDUH detailed tables: CBHSQ data. January 4, 2023. Accessed September 5, 2023. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2021-nsduh-detailed-tables

- 8.Jebai R, Osibogun O, Li W, et al. Temporal trends in tobacco product use among US middle and high school students: National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2011-2020. Public Health Rep. 2023;138(3):483-492. doi: 10.1177/00333549221103812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dai H, Leventhal AM, Dunn S, et al. Prevalence of e-cigarette use among adults in the United States, 2014-2018. JAMA. 2019;322(18):1824-1827. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.15331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasza KA, Edwards KC, Kimmel HL, et al. Association of e-cigarette use with discontinuation of cigarette smoking among adult smokers who were initially never planning to quit. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(12):e2140880. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glantz S, Jeffers A, Winickoff JP. Nicotine addiction and intensity of e-cigarette use by adolescents in the US, 2014 to 2021. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2240671. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.40671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie W, Kathuria H, Galiatsatos P, et al. Association of electronic cigarette use with incident respiratory conditions among US adults from 2013 to 2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2020816. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.20816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merz W, Magraner J, Gunge D, Advani I, Crotty Alexander LE, Oren E. Electronic cigarette use and perceptions during COVID-19. Respir Med. 2022;200:106925. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2022.106925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adzrago D, Sulley S, Mamudu L, Ormiston CK, Williams F. The influence of COVID-19 pandemic on the frequent use of e-cigarettes and its association with substance use and mental health symptoms. Behav Sci (Basel). 2022;12(11):453. doi: 10.3390/bs12110453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cabral P. E-cigarette use and intentions related to psychological distress among cigarette, e-cigarette, and cannabis vape users during the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychol. 2022;10(1):201. doi: 10.1186/s40359-022-00910-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . About the National Health Interview Survey. Updated March 3, 2022. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/about_nhis.htm

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System—overview: BRFSS 2021. July 22, 2022. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2021/pdf/Overview_2021-508.pdf

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Weighting calculated variables in the 2021 data file of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. 2021. Accessed May 1, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2021/pdf/2021-weighting-description-508.pdf

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System—2021 Summary Data Quality Report. August 9, 2022. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2021/pdf/2021-dqr-508.pdf

- 20.Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation . 2021 poverty guidelines. Accessed May 1, 2023. https://aspe.hhs.gov/2021-poverty-guidelines

- 21.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Weighting calculated variables in the 2021 data file of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Accessed May 1, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2021/pdf/2021-weighting-description-508.pdf

- 22.El-Shahawy O, Park SH, Duncan DT, et al. Evaluating state-level differences in e-cigarette and cigarette use among adults in the United States between 2012 and. findings from the National Adult Tobacco Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(1):71-80. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nty013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kramarow EA, Elgaddal N. QuickStats: percentage distribution of cigarette smoking status among current adult e-cigarette users, by age group—National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(10):270. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7210a7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . About BRFSS. Updated May 16, 2014. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/about/index.htm

- 25.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Health Interview Survey—2021 survey description. August 2022. Accessed May 16, 2023. https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2021/srvydesc-508.pdf

- 26.Gaiha SM, Lempert LK, Halpern-Felsher B. Underage youth and young adult e-cigarette use and access before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2027572. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.27572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soule EK, Mayne S, Snipes W, Guy MC, Breland A, Fagan P. Impacts of COVID-19 on electronic cigarette purchasing, use and related behaviors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):6762. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennett M, Speer J, Taylor N, Alexander T. Changes in e-cigarette use among youth and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: insights into risk perceptions and reasons for changing use behavior. Nicotine Tob Res. 2023;25(2):350-355. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntac136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erhabor J, Boakye E, Osuji N, et al. Psychosocial stressors and current e-cigarette use in the youth risk behavior survey. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1080. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-16031-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelsh S, Ottney A, Young M, Kelly M, Larson R, Sohn M. Young adults’ electronic cigarette use and perceptions of risk. Tob Use Insights. 2023;16:X231161313. doi: 10.1177/1179173X231161313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aly AS, Mamikutty R, Marhazlinda J. Association between harmful and addictive perceptions of e-cigarettes and e-cigarette use among adolescents and youth—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Children (Basel). 2022;9(11):1678. doi: 10.3390/children9111678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fadus MC, Smith TT, Squeglia LM. The rise of e-cigarettes, pod mod devices, and JUUL among youth: factors influencing use, health implications, and downstream effects. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;201:85-93. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sapru S, Vardhan M, Li Q, Guo Y, Li X, Saxena D. E-cigarettes use in the United States: reasons for use, perceptions, and effects on health. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1518. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09572-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harlow AF, Stokes AC, Brooks DR, Benjamin EJ, Barrington-Trimis JL, Ross CS. E-cigarette use and combustible cigarette smoking initiation among youth: accounting for time-varying exposure and time-dependent confounding. Epidemiology. 2022;33(4):523-532. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000001491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morean ME, Krishnan-Sarin S, S O’Malley S. Assessing nicotine dependence in adolescent E-cigarette users: the 4-item Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Nicotine Dependence Item Bank for electronic cigarettes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;188:60-63. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.03.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pearson JL, Zhou Y, Smiley SL, et al. Intensive longitudinal study of the relationship between cigalike e-cigarette use and cigarette smoking among adult cigarette smokers without immediate plans to quit smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23(3):527-534. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Du Y, Liu B, Xu G, et al. Association of electronic cigarette regulations with electronic cigarette use among adults in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1):e1920255. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Agaku IT, Nkosi L, Agaku QD, Gwar J, Tsafa T. A rapid evaluation of the US Federal Tobacco 21 (T21) law and lessons from statewide T21 policies: findings from population-level surveys. Prev Chronic Dis. 2022;19:E29. doi: 10.5888/pcd19.210430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boakye E, Erhabor J, Obisesan O, et al. Comprehensive review of the national surveys that assess e-cigarette use domains among youth and adults in the United States. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2023;23:100528. doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2023.100528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Weighted Sample Size by Participant Characteristics

eTable 2. Weighted Prevalence of Current Sole E-Cigarette, Dual (E-Cigarette and Combustible Cigarette), and Exclusive Combustible Cigarette Use Across Age Groups, 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

eTable 3. Age-Standardized Weighted Prevalence of E-Cigarette Use (Current and Daily) Across US States, 2019 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

eFigure 1. Proportion of Current E-Cigarette Use Among Individuals With No Smoking History

eFigure 2. Patterns of E-Cigarette and Combustible Cigarette Use by Age, 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

eFigure 3. Prevalence of Current E-Cigarette Use by State, 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

Data Sharing Statement