Introduction

In this chapter we review approaches to studying the epidemiology of NTM pulmonary disease (NTM-PD), and update advances in the field since the last review published in 2015 1.

The importance of epidemiology: surveillance and research

Defining the NTM-PD disease burden is critical for justifying the need for resource allocation, both for clinical resources such as health care, as well as for the development of new therapeutics. A fuller understanding of the risk factors which contribute to changes in disease frequency is important for guiding and evaluating interventions, at either the individual-level through modification of behaviors, or through structural interventions beyond the individual. Epidemiologic surveillance is key for estimating the burden of disease (prevalence) as well as the frequency of new cases (incidence) in a given population 2, which in turn can lead to developing hypotheses regarding individual or general environmental risk factors for infection and disease 3, 4.

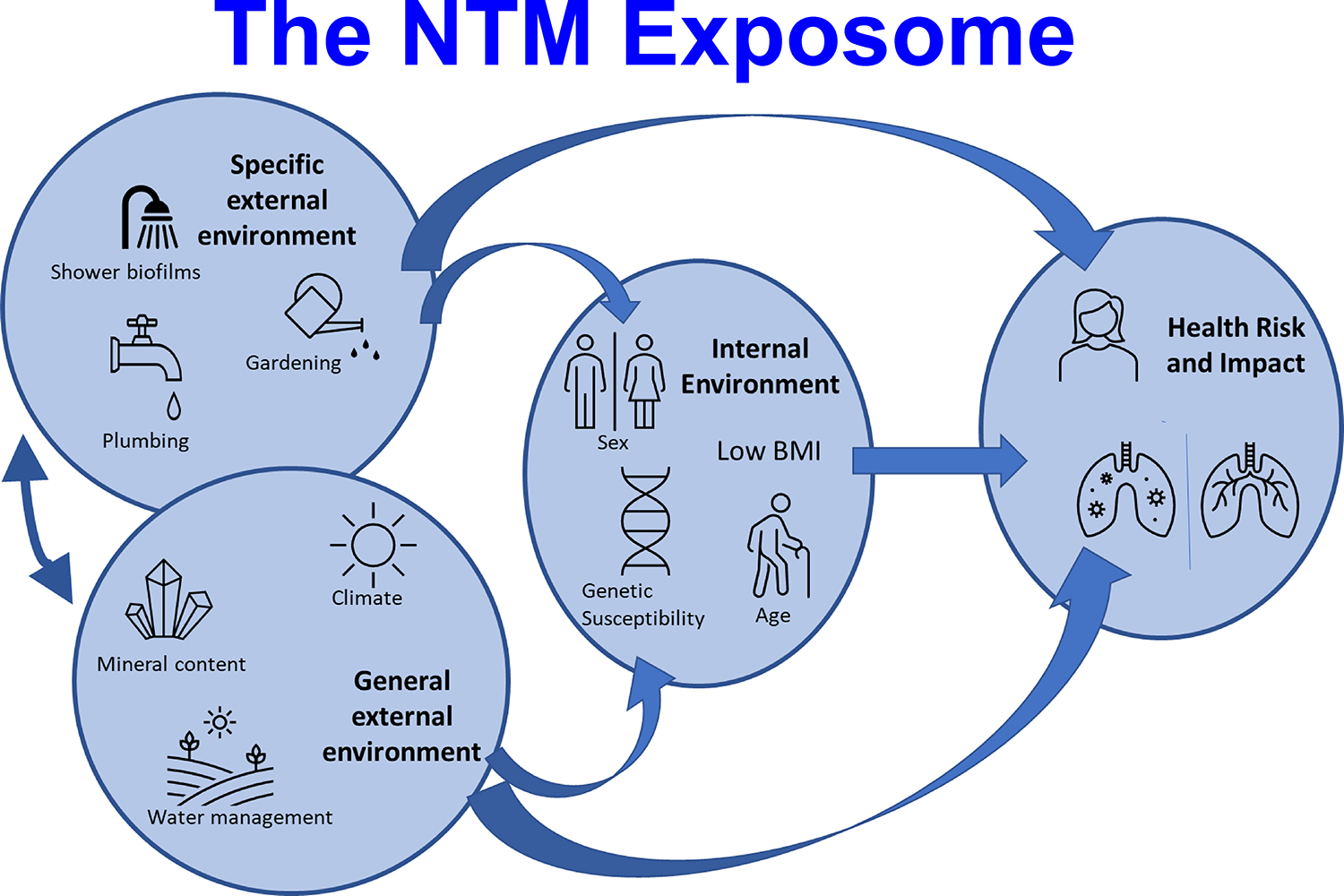

We here present a new approach for understanding the external and internal exposures which may lead to increased risk of NTM disease 5 (Figure 1). This paradigm is adapted from the fields of environmental epidemiology 5 and cancer epidemiology 6, whereby cumulative exposures to a variety of types of exposures will increase the risk of infection and disease. With respect to NTM-PD, specific environmental factors include those in an individual’s environment, such as those exposures from high-risk activities such as gardening, with aerosolization of soil. General environmental exposures include those beyond the control of a single individual which impact an entire population. Both factors interact with the human host, and host susceptibility, including biologic response, will influence the risk of developing NTM-PD 5 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

NTM exosome framework. Adapted from The exposome: a new paradigm to study the impact of environment on health, Vrijheid M., 69, 876–8, 2014 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Methodologic challenges

A key methodologic challenge is the lack of a global surveillance system with standard case definitions that would allow comparison within and across countries and regions. The NTM-PD case definition which includes microbiologic, radiographic, and clinical criteria, was developed by ATS/IDSA in 2007 for diagnostic and treatment purposes 7, and endorsed in the more recent ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA guidelines 8. In this review we will use the simplified term “ATS-criteria” acknowledging the equal contribution of the other societies. However, different case definitions may be used for epidemiologic purposes of monitoring infection rates and risk factor identification, as the decision about whether and when to treat is different from the surveillance goal of identifying patterns of infection and disease.

Ascertaining the radiographic and clinical criteria for NTM-PD is generally time consuming and costly, and therefore not feasible at the scale needed to study national and regional patterns, particularly in areas with a higher disease burden. Therefore, microbiology data from centralized public health laboratory systems, as well as administrative claims data with International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes have been increasingly used to better understand the epidemiology of NTM-PD. Each approach has strengths and limitations. Microbiologic data provide an indicator of exposure from the environment, but will overestimate the true disease prevalence, as not all isolates from respiratory secretions are clinically significant. In this review we use the term “isolation” or “isolates” to refer to culture positivity of respiratory specimens for NTM without necessarily attributing these isolates to a disease status in a specific patient. We therefore also avoid the term “colonization” which suggests “no disease”, a status which has not been well studied. Although the term “NTM infection” has often been used to refer to cases which satisfy the ATS microbiologic criteria 9–14 we generally avoid use of this term as the definition of this term has not been standardized.

The microbiologic component of the ATS criteria, as well as ICD codes (9 or 10) have been evaluated and found to have a high predictive value for NTM-PD (meeting the full ATS diagnostic criteria). In a large, population-based cohort from a centralized provincial laboratory in Ontario, Canada, 46% of those with an isolate of NTM met the microbiologic component of the ATS disease diagnostic criteria 14. Within the subset of patients being followed in a clinic setting, 73% of the patients who fulfilled the ATS microbiologic criteria met the full ATS disease criteria, indicating a high predictive value 14. Similarly, in a large national study using NTM isolates from the national referral laboratory in Denmark, among a small subset with isolates meeting ATS microbiologic criteria (termed “possible NTM disease”), 90% met the full ATS disease criteria 13. In a study in North Carolina, USA, based on mycobacterial isolation and full chart review, 55.7% of those with an isolate met the ATS microbiologic criteria, and 60.9% of these met the full criteria including microbiologic, clinical, and radiographic criteria 15. Thus, although analysis of isolates is important for understanding patterns and trends, case definitions based on 1 or 2 isolates will usually overestimate the burden of ATS defined NTM-PD.

ICD codes provide a more useful indicator of true disease, although they will tend to underestimate true disease prevalence, as administrative codes tend to lack sensitivity for rare disease. The sensitivity of the ICD codes relative to the ATS microbiologic criteria has been found to range from 27% 16 in a general population to 50% among persons with rheumatoid arthritis 17 and up to 69% among persons with bronchiectasis 18; the positive predictive value across various studies has ranged from 77% to 100% 17–19. Although these codes may underestimate true disease rates, the direction of this bias is unlikely to change substantially across time and populations, such that these codes are useful tools for epidemiologic purposes.

Two noteworthy examples of implementation of NTM-PD surveillance are from Queensland, Australia, and the state of Oregon, USA. In Queensland, laboratory-based notification of NTM isolates has been mandated since the inception of the Tuberculosis control program in the 1950’s, and all cases of NTM isolation are notifiable under the Public Health Act 3. Data from this surveillance system has since facilitated the characterization of NTM-PD epidemiology, particularly with respect to geographic distribution, environmental risk factors, and increasing burden 3. In the state of Oregon, USA, a pilot surveillance program was implemented from 2005–2006 and provided important insights regarding NTM epidemiology 4, 19. Currently, in the United States, only 4 states have mandated notification of NTM-PD, as part of a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) through an Emerging Infections Network (EIN) pilot program 20, 21.

Despite the known limitations of death certificate data, in the United States, recent data have shown an increase in non-HIV associated NTM-related deaths from 1999–2014, during a period in which both HIV-associated NTM-related mortality decreased, and TB-associated mortality also decreased significantly 22. In Japan, in the absence of nationally representative data, mortality data were useful for providing insight into patterns by age, sex, and region, and for estimating prevalence 23. Several studies have identified the increased risk of mortality associated with NTM-PD 24, 25 In one study, persons with NTM-PD had a fourfold increased risk of death after adjusting for all other factors (HR=3.64) 26.

Risk factors: Environment

General and specific environmental risk factors identified to date are summarized in Table 1. Specific exposures refer to those estimated from studies which associate individual behaviors or household factors with human NTM pulmonary isolation or disease. General exposures refer to those not unique to a single individual but rather which affect the broader population.

Table 1:

Host and Environmental Risk factors for NTM infection and disease

| Risk Factor | Relative risk, Odds ratio, Relative Prevalence, or other measure | Case Definition |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Environmental: specific individual exposures | ||

|

| ||

| NTM isolation from shower aerosols, Oregon, USA | 4.0 [OR]27 | MAC-PD, case-control study |

|

| ||

| Use of spray bottle to spray house plants, Oregon, USA | 2.7 [OR]29 | MAC-PD, case-control study |

|

| ||

| Use of Public Baths ≥ 1/week, S Korea | 4.0 [OR]30 | MAC-PD, case-control study |

|

| ||

| Indoor swimming pool use (in the past four months), USA | 5.9 [OR]31 | Incident pulmonary isolation persons with CF (pwCF) |

|

| ||

| Soil exposure, Japan (bronchiectasis with MAC vs bronchiectasis with no MAC) | 5.9 [OR]33 | MAC-PD, case-control study |

|

| ||

| Environment- general exposures, measured at population level: climate, soil, and water- related | ||

|

| ||

| Relative abundance of NTM in showerhead biofilm and population prevalence | Significant correlation, p<0.000135 | NTM-PD and NTM pulmonary isolation (Medicare with ICD codes; CF ≥ 1 pulmonary isolate) |

|

| ||

| Higher average annual precipitation, FL, USA | 1.34130 | Incident pulmonary isolation (≥ 1 isolate) among persons with CF |

|

| ||

| Increased soil sodium, FL, USA | 1.92130 | Incident pulmonary isolation (≥ 1 isolate) among persons with CF |

|

| ||

| Increased soil manganese | 0.59130 | Incident pulmonary isolation (≥ 1 isolate) among persons with CF |

|

| ||

| Increased molybdenum concentrations in source water | 1.4112 | M. abscessus incident pulmonary isolation (≥2 isolates), non-CF |

| 1.7911 | M. abscessus pulmonary isolation in persons with CF (≥1 isolate) | |

|

| ||

| Increased vanadium concentrations in source water | 1.4912 | Incident MAC isolation (≥2 isolates), non-CF |

| 1.2236 | Incident MAC pulmonary isolation, non-CF (≥2 isolates) | |

|

| ||

| Percent hydric soil in census blocks, NC, USA | 26.838 | NTM pulmonary isolation (≥ 1 isolate), non-CF |

|

| ||

| Proportion of area as surface water | 4.639 | NTM-PD (ICD codes) |

|

| ||

| Mean daily potential evapotranspiration | 4.039 | NTM-PD (ICD codes) |

|

| ||

| Copper soil levels, per 1 ppm increase | 1.239 | NTM-PD (ICD codes) |

|

| ||

| Sodium soil levels, per 0.1 ppm increase | 1.939 | NTM-PD (ICD codes) |

|

| ||

| Manganese soil levels, per 100 ppm increase | 0.739 | NTM-PD (ICD codes) |

|

| ||

| Increased average topsoil depth | 0.87 (M. intracellulare)42 | NTM isolation (≥ 1 isolate), non-CF |

|

| ||

| Soil bulk density | 1.8 (M. kansasii)42 | NTM isolation (≥ 1 isolate), non-CF |

Estimated from data in paper

Hazard ratio, fully adjusted for age, sex, income, rurality, and comorbidities for NTM (HIV, COPD, asthma, and GERD)

Comparison of patients with NTM/TB with uninfected anti-TNF users

risk decreased with increasing duration since use; see full paper for specific estimates

Case-control studies in the United States, South Korea, and Japan have identified individual factors related to water and soil exposure. A recent study in Oregon, United States, found that the NTM isolation in the household shower aerosols was significantly associated with NTM-PD 27, but that other home water and soil exposure were not. This finding is supported by a study in Queensland, Australia which found genetic matches between patient isolates and species identified from shower aerosols and household water supplies 28. In the initial Oregon study, the only household-level factors significantly associated with NTM-PD risk was spraying plants with a spray bottle [OR=2.7] 29. In South Korea, use of public baths at least weekly was associated with a fourfold increased risk of NTM-PD 30. In the United States, a national study of NTM-PD among persons with CF found that indoor swimming pool use at least monthly was significantly associated with incident NTM isolation 31 (Table 1), and that other behavioral factors, including showering frequency, were not. A study among children with CF in Florida found that those who lived in households which were within 500 meters of a body of water had a significant 9.4-fold increased odds of having NTM pulmonary isolation 32. In Japan, exposure to soil more than twice weekly was significantly associated with the NTM-PD 33. The high risk associated with frequent soil exposure is consistent with a population-based study of agriculture workers in Florida, which found that cumulative occupational exposure was significantly associated with infection, as defined by M. avium skin test sensitivity 34. The risk associated with any given behavior will depend on the intensity of the exposure and the NTM abundance in environmental exposure source–generally soil or water. The risk associated with household NTM isolation from shower aerosols in the NTM-PD study in Oregon is supported by a national study of shower biofilms, which found a significant correlation between the relative abundance of NTM in showerhead biofilms and state-level NTM-PD prevalence in both the CF population and the US Medicare beneficiary population aged ≥65 years 35.

Ecologic epidemiologic studies have found water, soil, and climate factors associated with an increased risk of NTM-PD; these studies have been conducted primarily in the United States and Australia (Table 1). In several studies conducted in the United States from 2020–2022, a consistently significant and strong association has been found between concentrations of molybdenum and M. abscessus infection, and vanadium and MAC infections in natural water sources (ground or surface) supplying municipal water systems: for every log increase in molybdenum concentrations the risk of M. abscessus isolation increased by 41% 12 to 79% 11; for every log increase in the concentration of vanadium, the risk of MAC isolation (≥ 2 isolates) increased 22% 36 to 49% 12 (Table 1). Interestingly, a case-control study in South Korea found NTM-PD patients had significantly higher median blood serum concentrations of molybdenum than controls 37.

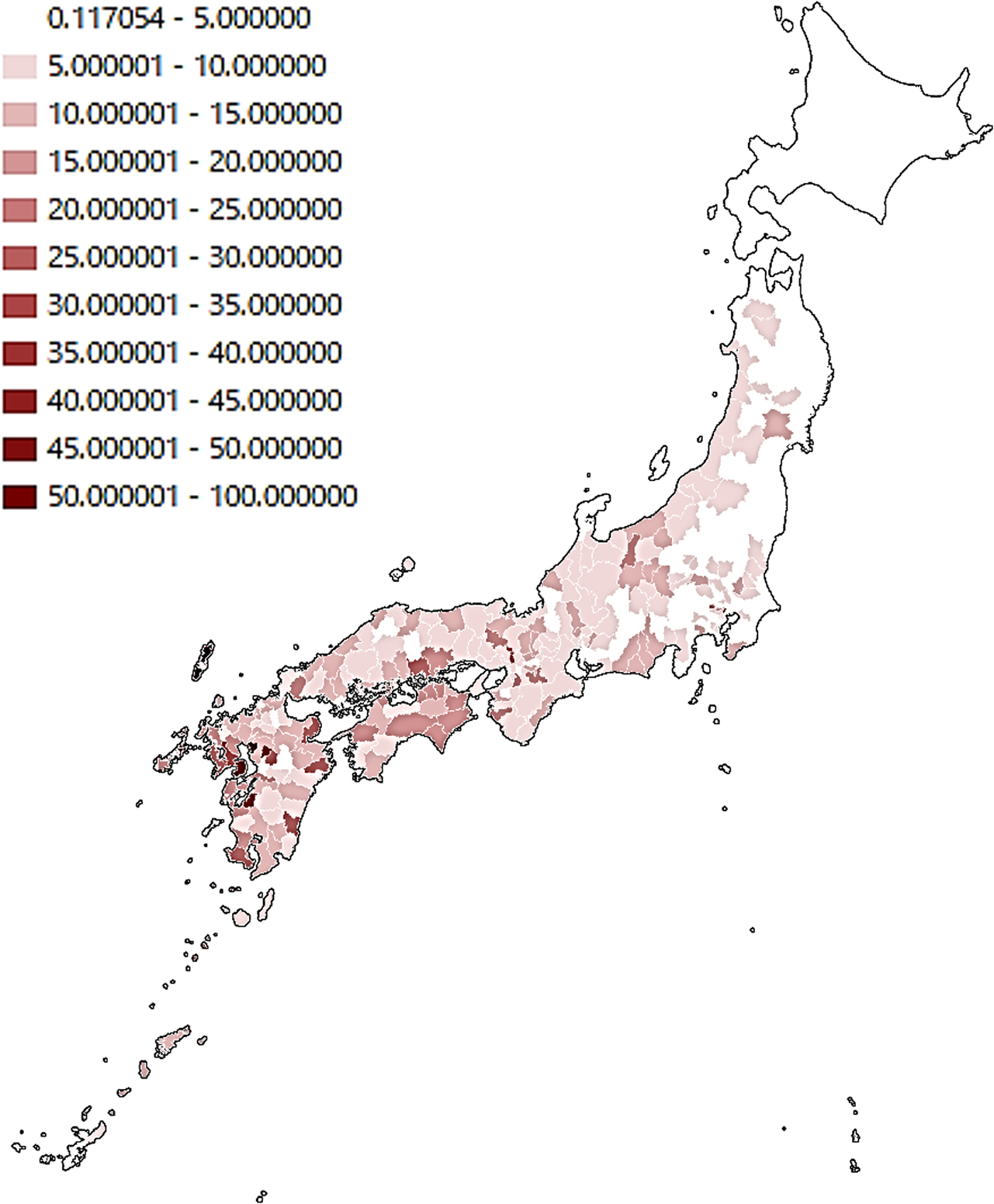

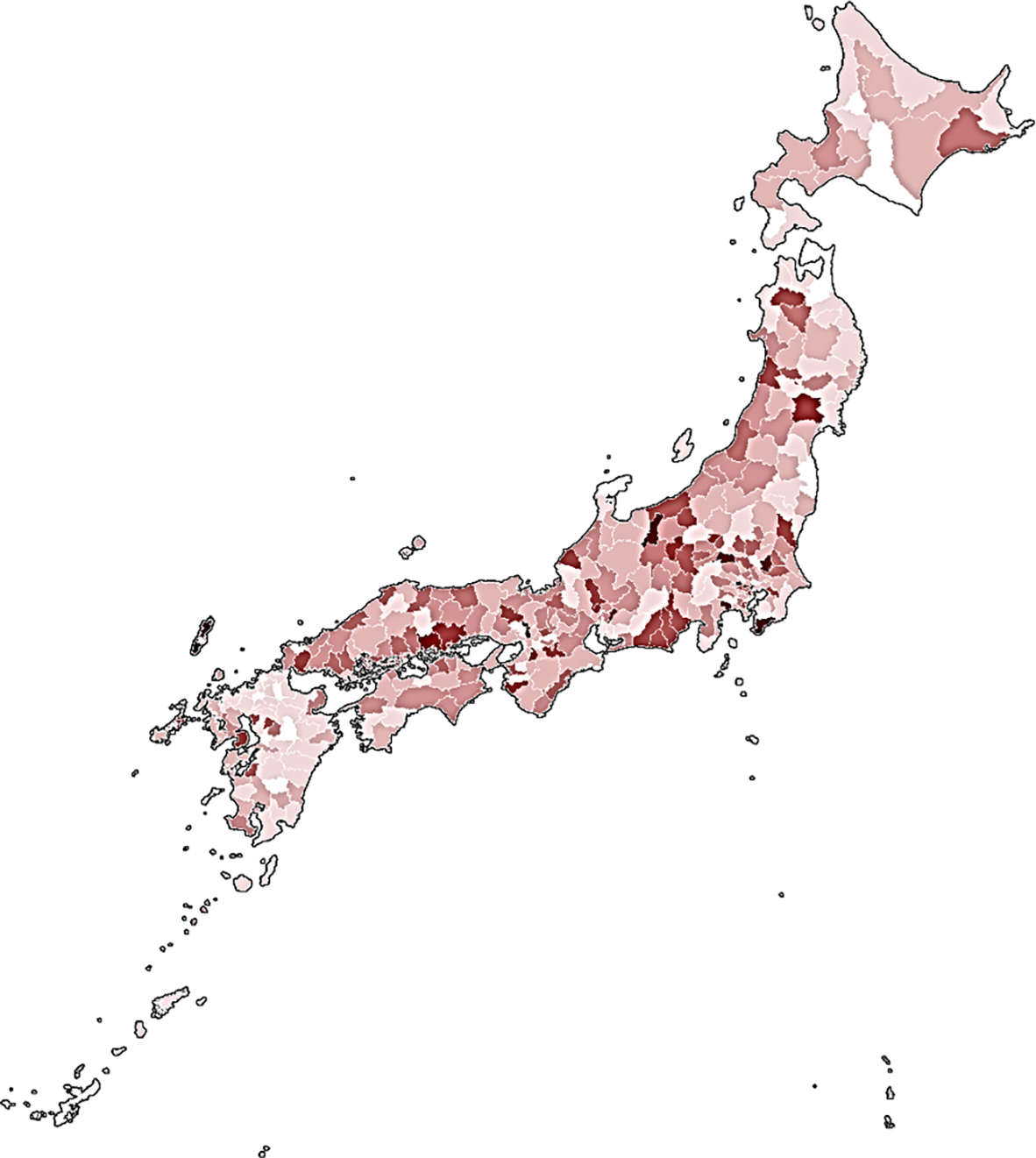

Several other studies have identified risks related to soil, land use, and other climate factors. In North Carolina, USA, the percent hydric soil in census blocks was significantly associated with NTM isolation: census blocks with >20% hydric soils had a significant 26.8% increased adjusted mean patient count relative to those with ≤20% hydric soils 38. In Florida, in the CF population, increased soil sodium in the zip code of residence was associated with an increased risk of incident NTM isolation, whereas increased soil manganese was protective 39. In the same study, persons living in counties with above average annual levels of precipitation were also at increased risk of incident infection 39. In two national studies in the United States, vapor pressure (a measure of the water in the atmosphere at a given temperature) was predictive of disease prevalence among CF patients 31 as well as Medicare beneficiaries aged ≥65 years 31, 40. In addition, in the national Medicare study, evapotranspiration (the potential of the atmosphere to absorb water), and the proportion of the area as surface water were predictive of high-risk areas 39. In the Medicare study, higher manganese soil levels in the county were associated with lower incidence of NTM-PD, whereas higher copper and sodium levels in soil were associated with increased risk 39. In Queensland, Australia, an effect of temperature and rainfall was observed, but this varied by region: cyclic incidence patterns were associated with temperature and rainfall 41. In a prior study in Australia, increased average topsoil depth was protective against M. intracellulare, while increased soil bulk density was positively associated with M. kansasii disease 42. In Japan, NTM-PD mortality, a surrogate measure for disease prevalence and distribution, was higher in the warmer and more humid coastal areas and in an area with a large amount of surface water (lake) 23. A recent study found dust bioaerosols as a source of NTM, with higher relative abundance in East Asian inland cities in Japan and China than in desert areas 43.

Epidemiology of NTM Isolation and Disease by Global Region

In our review of epidemiological data of NTM-PD, we strive to include the highest quality data published since 2014. Ideal studies comprise population-based investigations including both clinical and microbiologic data and encompassing an adequate temporal period to best capture the burden of infection in the population. However, because these types of data are often not available, other data sources are used as described previously.

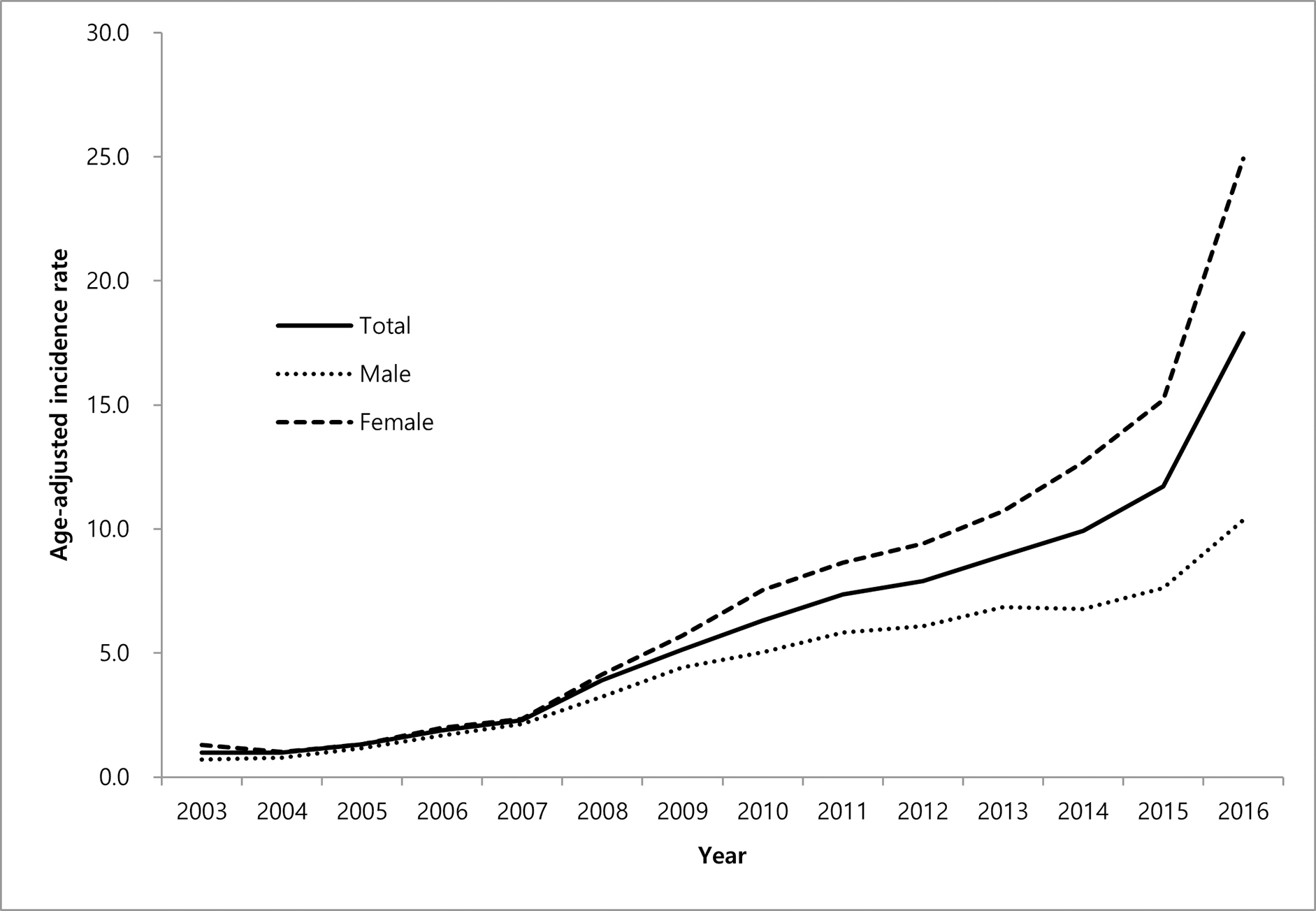

Systematic Review and Meta-analysis – Global

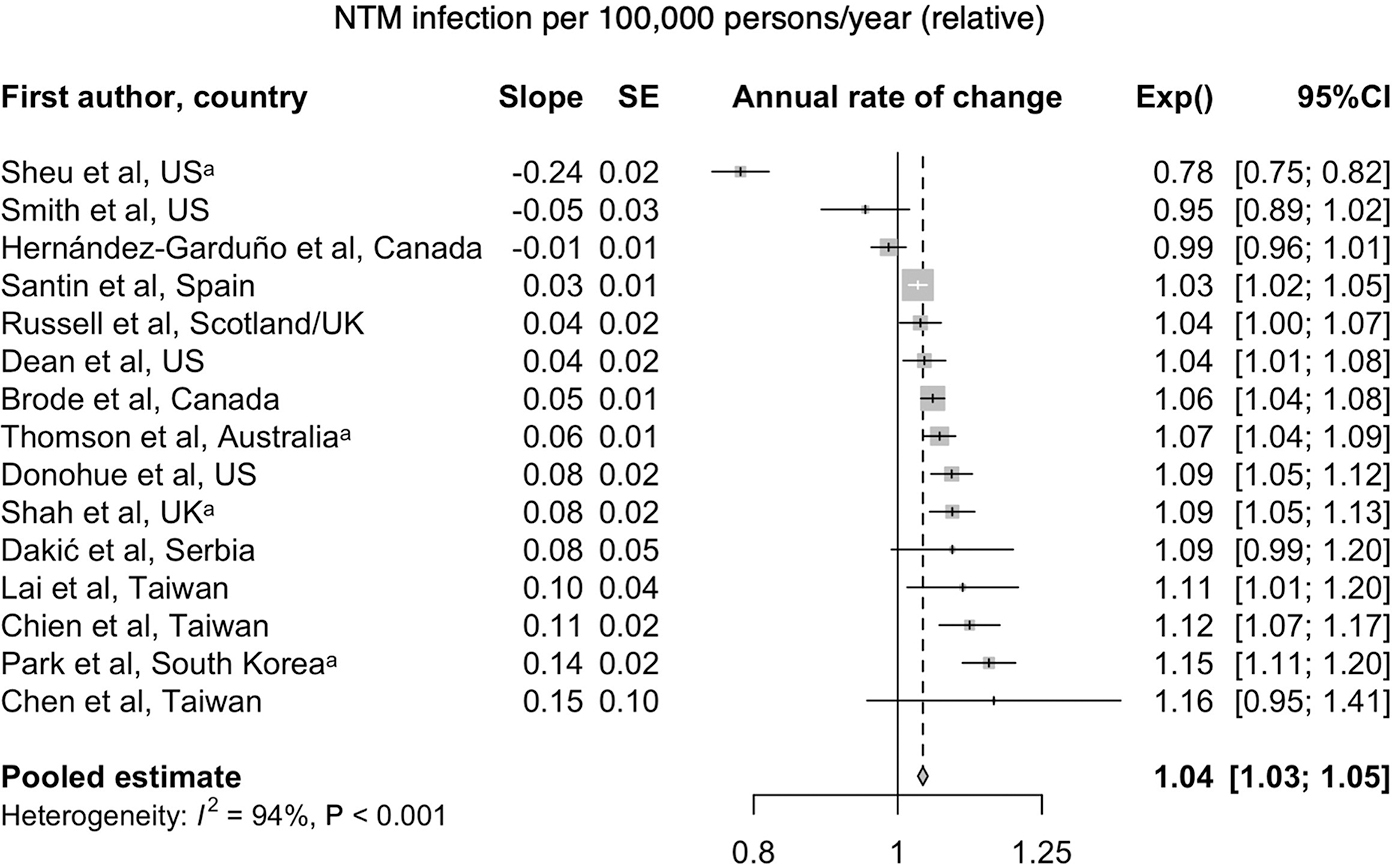

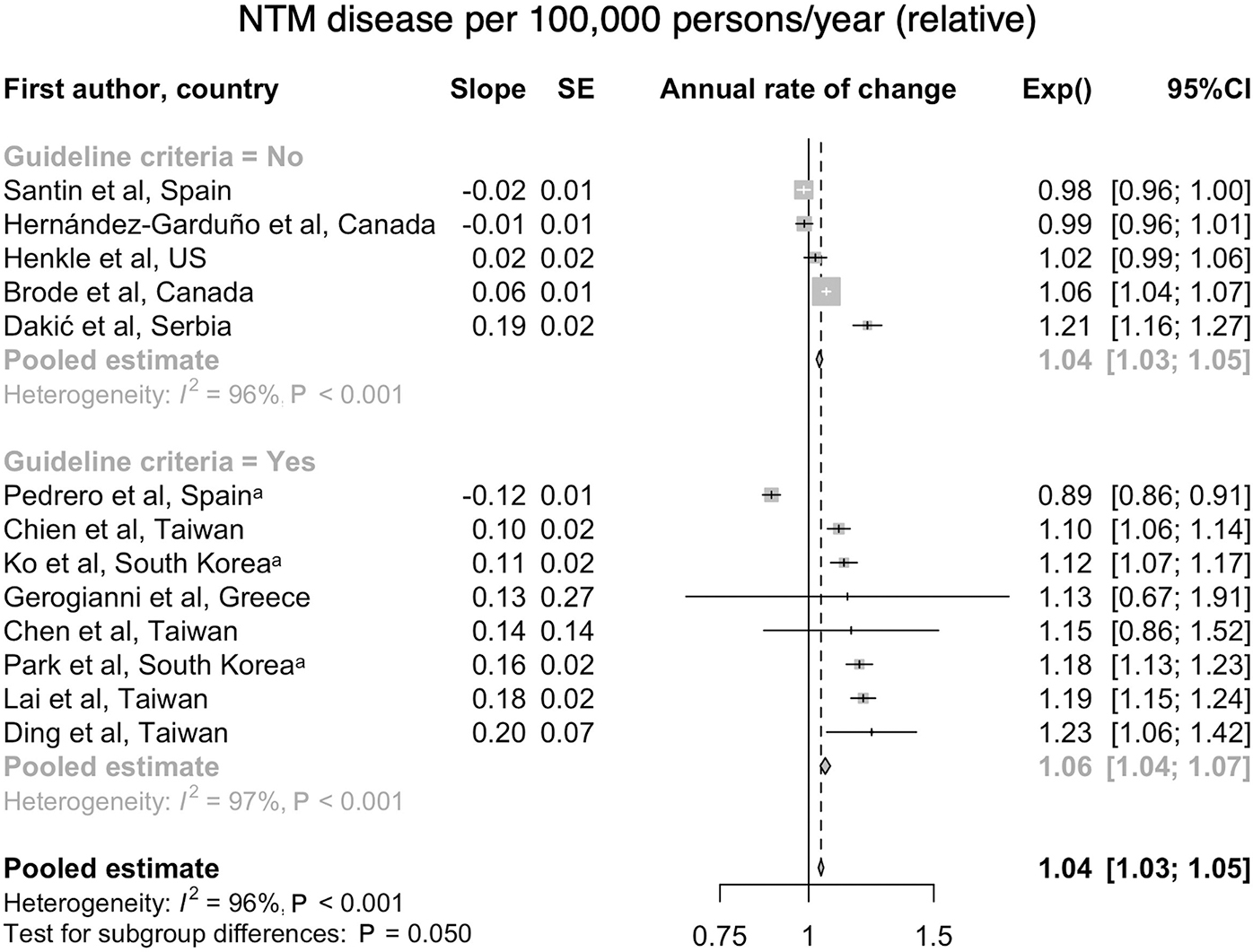

A systematic review and meta-analysis was recently conducted for global culture-based microbiologic data, indicating an overall increase worldwide in the frequency of isolation, including that which satisfies the ATS microbiologic criteria9. This review included only those studies with culture-based data for at least three years, and with at least 200 samples, representing findings from 47 publications in more than 18 countries. Overall, 82% of studies reported increasing isolation, and 66.7% reported increasing disease, using either the adapted ATS microbiologic criteria or the full radiographic and clinical criteria. The overall rate of increase was 4% (3.2–4.8) per year for isolation and 4.1% (3.2–5) per year for disease, which was most often defined using the ATS microbiologic criteria. Most of these studies focused on MAC, the predominant species, and to a lesser degree the M. abscessus group9 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

a. Forest plot of annual change of NTM infection per 100,000 persons/year. From Dahl VN, Mølhave M, Fløe A, et al. Global trends of pulmonary infections with nontuberculous mycobacteria: a systematic review. Int J Infect Dis. Oct 13 2022;125:120–131. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2022.10.013; with permission. (Figure 3 in original) b. Forest plot of annual change of NTM disease per 100,000 persons/year (Dahl et al., 2022); with permission. (Figure 6 in original)

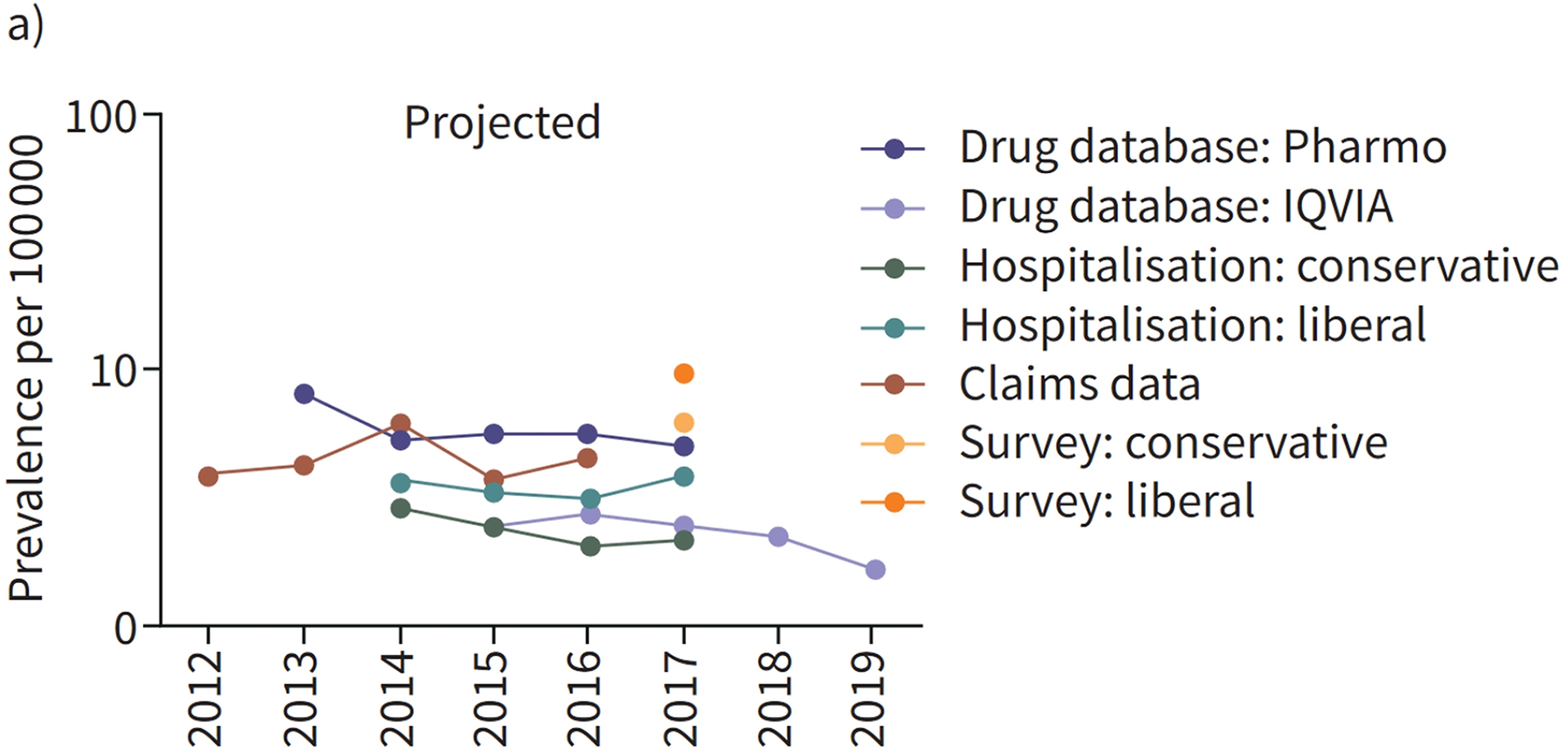

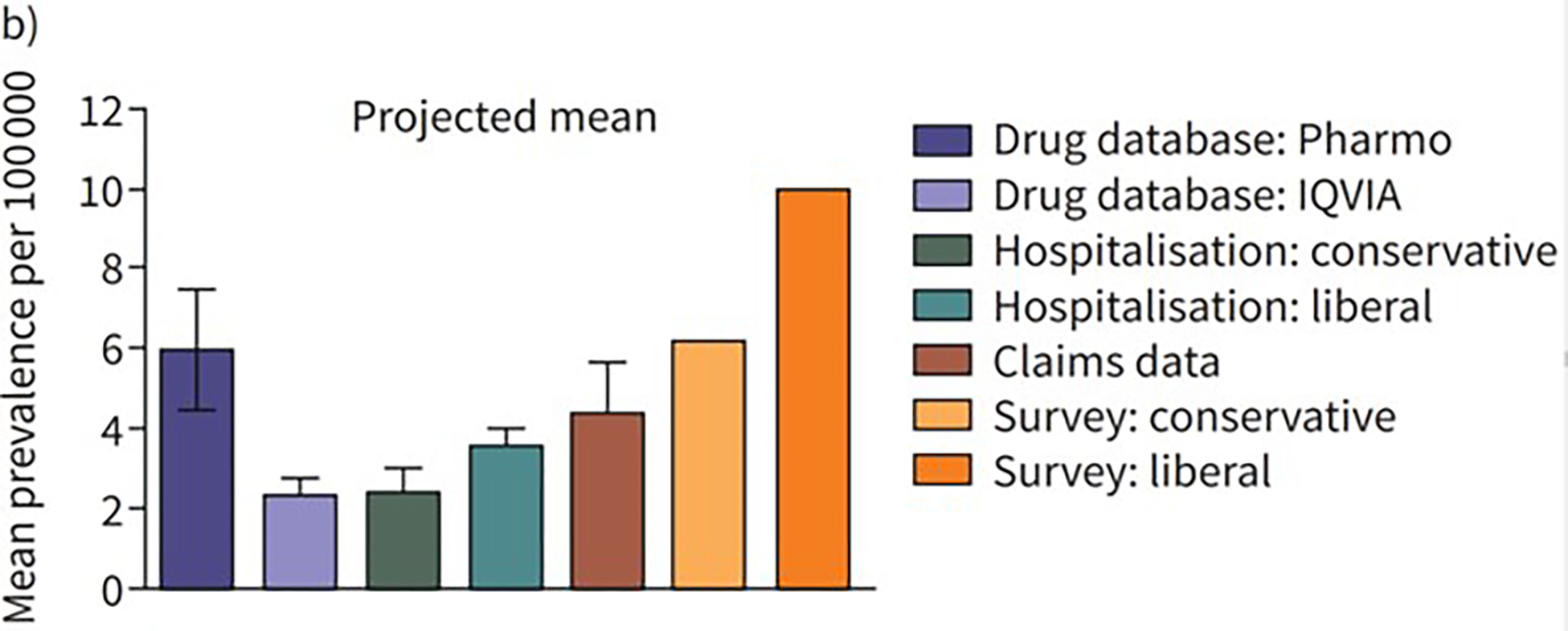

A recent Delphi survey including a physician survey as well as chart review allowed comparison of prevalence rates across 4 European countries (France, Germany, Spain, UK) and Japan, and found a remarkably similar prevalence of NTM-PD of 6.1/100,000 to 6.6/100 000 across European countries, but with a fourfold increased prevalence in Japan, suggesting true differences in prevalence 44.

North America

In North America, national and subnational studies indicate increasing prevalence and incidence, and continue to demonstrate geographic heterogeneity in NTM isolation and disease. This section is based on five national studies from the United States, one provincial level study from Ontario, and nine state or territorial level studies in the United States. The national studies include three based on ICD codes to define disease, and two based on microbiologic data. The heterogeneity of methodologic approaches makes comparisons difficult, but overall, these studies indicate a picture of increasing prevalence dominated by MAC infections.

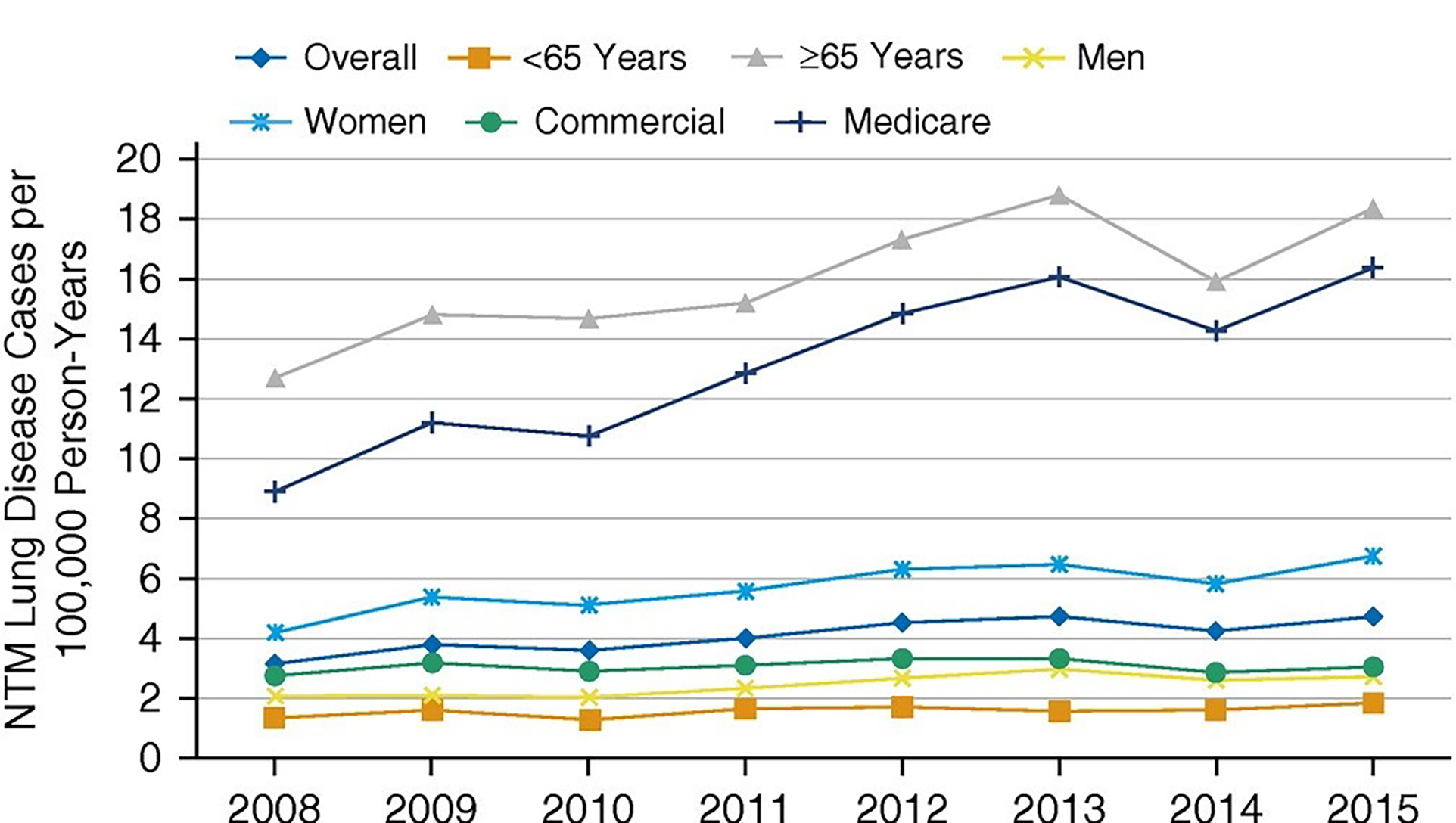

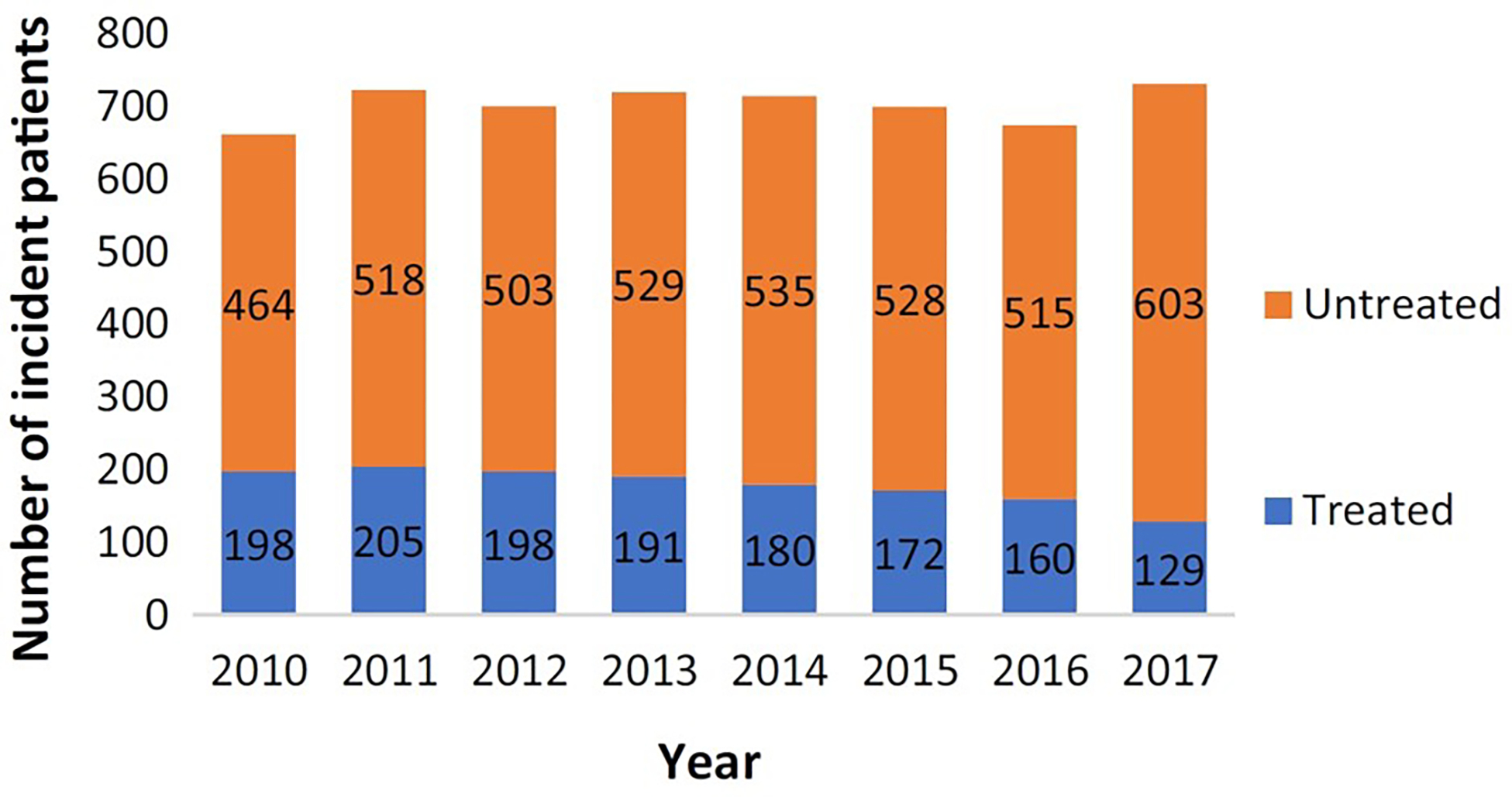

In the United States, a national study to estimate prevalence and incidence of NTM-PD defined this as two claims with NTM-PD ICD codes separated by 30 days. This study estimated a prevalence of 6.8/100,000 in 2008, increasing to 11.7/100,000 in 2015, with an estimated annual incidence from 3.1/100,000 to 4.7/100,000 during the same time period 45 (Figure 3). A separate study which estimated prevalence using a single ICD code for NTM to define a case estimated a prevalence of 27.9/100,000 in 2010, with a projected estimate of 181,037 cases in 2014, assuming a continued 8% annual prevalence increase 46. The discrepancy in estimates between the two studies for a similar year (2014/2015) is due to the more specific case definition in the former study. The geographic heterogeneity across states was consistent with prior reports and historic patterns, with the highest prevalence in the warm, humid areas in the Southeast and Southwest 46. A study in a high risk population, among veterans with COPD, also used two ICD codes for NTM-PD to define disease and found an increasing incidence and prevalence NTM-PD from 2001 to 2015, with incidence increasing from 34.2/100,000 to 70.3/100,000 and prevalence from 93.1/100,000 to 277.6/100,000 patients 47.

Figure 3.

Annual incidence of NTM-PD in national U.S. health insurance plan (Optum EHR database) 2008–2015. Reprinted with permission of the American Thoracic Society. Copyright © 2023 American Thoracic Society. All rights reserved. Cite: Winthrop KL, Marras TK, Adjemian J, Zhang H, Wang P, Zhang Q./2020/Incidence and Prevalence of Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Lung Disease in a Large U.S. Managed Care Health Plan, 2008–2015/Ann Am Thorac Soc./17/178–185. Annals of the American Thoracic Society is an official journal of the American Thoracic Society. (Figure 2 in original)

Two national microbiologic studies based on electronic health records demonstrated geographic variation in NTM species as well as increasing trends in AFB testing and NTM isolation prevalence in high-risk groups 48, 49. Among 5 million unique patients of whom 7,812 had at least one isolate, MAC was the most common species, ranging from 61 to 91% of isolates, and was most frequent in the South and Northeast regions; M. abscessus/M. chelonae ranged from 2% to 18% of isolates and were most frequent in the West. A separate national study using microbiology data from a different large EHR system to study frequency of AFB testing and pulmonary NTM isolation during 2009–2015 found an overall AFB testing rate of 45/10,000 population with an increasing annual percent change (APC) of 3.2% 49. The isolation rate for pathogenic NTM also increased with an APC of 4.5% and was highest among persons with CF and those with bronchiectasis 49.

One subnational study used population-based surveillance data from 2014 in four states (Mississippi, Missouri, Ohio, and Wisconsin) to describe NTM isolation. Overall prevalence was 13.3/100,000 population (after excluding M. gordonae), with a predominance of MAC, at a prevalence of 8.5/100,000 50. An earlier study which estimated trends from 2008–2013 in the same four states plus Maryland found an increasing trend, with an APC of 9.9% 51.

Hawaii and Florida have been identified as a ‘hotspots’ for NTM in the United States. In Hawaii, microbiologic data from a large, linked health care system were used to associate microbiologic data with demographic and clinical factors for the period 2005 and 2013. Isolation was based on at least one pulmonary isolate, and the ATS microbiologic criteria were used to define NTM-PD 52. Isolation prevalence increased significantly during the study period, from 20/100,000 in 2005 to 44/100,00 in 2013, with an APC of 6% and a period prevalence of 122/100,000; MAC was the most commonly isolated species, comprising 64% of isolates. NTM-PD (ATS microbiologic criteria) increased from 9/100,000 in 2005 to 19/100,000 in 2013 (Table 2). NTM isolation prevalence varied by ethnic group, with NTM isolation rates approximately twofold higher among persons who identified as Chinese, Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese relative to those who identified as white, and the prevalence was twofold lower among Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander (NHOPI) relative to whites 52 (Table 3). Another study used KPH data to estimate NTM infection incidence by ethnic group during the period 2005–2019 (Table 2) 53. Cases were defined as ≥ 1 pulmonary isolate. Average annual isolation incidence was 44.8 cases/100,000 beneficiaries, with a cumulative incidence of 247 cases/100,000 over the study period. Beneficiaries who self-identified with only Asian ethnic groups had the highest NTM pulmonary isolation incidence (46 cases/100,000 person-years) and had a 30% increased risk after controlling for all other clinical and demographic factors 53. A separate study from the US Affiliated Pacific Islands (USAPI), based on samples submitted to the Diagnostic Laboratory Services in Hawaii, typically for evaluation of suspected TB, found a significantly increasing rate of NTM isolation, increasing from 0.5% of isolates screened in 2007 to 11.3% in 2011, corresponding to an NTM isolation prevalence increase of 2/100,000 to 48/100,000. MTB isolation remained stable during the same period 54.

Table 2:

Studies of Rates of Pulmonary NTM Isolation and Disease by Region

| North America | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location (dates) | Case Definition | Data Source/Cohort | Annual Prevalence (per 100,000 population) | Period Prevalence | Incidence (per 100,000 population) | ||

| Isolation (dates) | Disease (dates) | Period Duration (years) | Prevalence (per 100,000 population) | ||||

| Canada | |||||||

| Ontario, Canada (1998–2010)131 | Isolation: ≥ 1 isolate Disease: ATS microbiologic criteria |

Public Health Ontario Laboratory Database | 11.4–22.2 (1998–2010) (APC: 6.3%); Annual Change (MAC: 0.291, M. xenopi: 0.059, M. abscessus: 0.019) | 4.65 – 9.08 (1998–2010) (APC: 8.0%)+** | - | - | - |

| United States | |||||||

| U.S. (2008–2015)45 | ICD-9/ICD-10 | Optum Clinformatics Data Mart Care Claims database | - | 6.78–11.70 (APC: 7.5%) (2008–2015) | 8 | - | 3.13–4.73 (2008–2015) (APC: 5.2%) (D) |

| Florida (2012–2018)55 | ICD-9-CM/ICD-10 | OneFlorida Clinical Research Consortium database | - | 14.3–22.6 (2012–2018) | 7 | - | 6.5–5.4 (2012–2018) (D) |

| Hawaii (2005–2013)52 | Isolation: ≥ 1 isolate Disease: ATS microbiologic criteria |

Kaiser Permanente Hawaii databases | 20–44 (2005–2013) (APC: 6%)** | 9–19 (2005–2013)+** | 9 | Range by Ethnic group: 50–300 (I)** | - |

| Hawaii (2005–2019)53 | ≥ 1 isolate | Kaiser Permanente Hawaii EHR databases | - | - | 15 | - | Overall Annualized: 44.8 (I)**, Range by Ethnic group: 17–63 (I)**, Cumulative: 247 (I)** |

| Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, Ohio, Wisconsin (2008–2013)51 | ≥ 1 isolate | Surveillance data from Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, Ohio, Wisconsin | Overall: 8.7–13.9 (2008–2013)§# (APC: 9.9%)§#, Maryland: 9.5–9.29 (2008–2013)§# Mississippi:10.2–13.69 (2008–2013)§#, Missouri: 5.5–13.39 (2008–2013)§#, Ohio: 5.8–11.39 (2008–2013)§#, Wisconsin: 15.4–24.69 (2008–2013)§# | - | - | - | - |

| North Carolina (2006–2010)58 | ≥ 1 isolate | All labs that test for NTM in 3 counties (hospital, commercial, public health) | Overall: 9.4** | - | - | - | - |

| North Carolina (2006–2010)38 | ≥ 1 isolate | All labs that test for NTM in 3 counties (hospital, commercial, publica health | - | - | 5 | - | Cumulative: 8.8 (I) |

| Oregon (2007–2012)10 | ATS microbiologic criteria | All laboratories that test for NTM in Oregon | - | 5.9 (2011–2012)+ | 6 | - | 5.0 (APC: 2.2%) (D)+; 3.8 (D)§+ |

| U.S.–Affiliated Pacific Island Jurisdictions (2007–2011)54 | ≥ 1 isolate | Diagnostic Laboratory Services data | 2–48 (2007–2011) (adjusted rate ratio 1.65) | - | 4 | Overall: 106 (I); American Samoa (22) (I), Federated States of Micronesia (164) (I) | - |

| Central and South America | |||||||

| Location (dates) | Case Definition | Data Source/Cohort | Annual Prevalence (per 100,000 population) | Period Prevalence | Incidence (per 100,000 population) | ||

| Isolation (dates) | Disease (dates) | Period Duration (years) | Prevalence (per 100,000 population) | ||||

| French Guiana (2008–2018)61 | Isolation: ≥ 1 isolate Disease: Full ATS criteria |

Three general hospitals EHR data | - | - | 11 | - | 6.17 (I); 1.07 (D) |

| Mexico City, Mexico (2001–2017)62 | Full ATS criteria | Tertiary care referral medical center EHR data | - | - | 17 | - | SGM: 0.6/1000 admissions (2001–2011)–1.9 (2012–2017) (D)#; RGM: 0.3/1000 (2001–2011)−1.1/1000 (2012–2017) (D)# |

| Uruguay (2006–2018)67 | ≥ 1 isolate | National tuberculosis reference laboratory EHR data | 0.33 – 1.57 (2006–2018) (4.79-fold increase)# | - | - | - | - |

| Europe | |||||||

| Location (dates) | Case Definition | Data Source/Cohort | Annual Prevalence (per 100,000 population) | Period Prevalence | Incidence (per 100,000 population) | ||

| Isolation (dates) | Disease (dates) | Period Duration (years) | Prevalence (per 100,000 population) | ||||

| Czech Republic (2012–2018)81 | Full ATS criteria | Public Health Institute Ostrava database for Moravian and Silesian Regions | - | - | 7 | - | 1.1 (D)# |

| Denmark (1991–2015)68 | Isolation: ≥ 1 isolate Disease: Modified ATS microbiologic criteria |

International Reference Laboratory data | - | - | 25 | - | 2.14 (I); Definite and Possible NTM-PD: 1.10 (D)+# |

| England, Wales and Northern Ireland (January 2007–July 2012)77 | ≥ 1 isolate | Public Health England database | - | - | 6 | - | 3.4–5.0 (2007–2012) (I)** |

| France (2010–2017)69 | ICD-10 or suggestive medication | National Health System database | - | - | 8 | 5.92 (D) | 1.025–1.096 (2010–2017) (D) |

| Germany (2009–2014)72 | ICD-10 | Health Risk Institute health services research database | - | 2.3–3.3 (2009–2014)§ | - | - | - |

| Germany (2010–2011)26 | ICD-10 | German statutory health insurances claims database | - | - | 2 | - | 1.12–1.48 (2010–2011) (D); Cumulative: 2.6 (D) |

| Germany (2011–2016)71 | ICD-10 (German modification) | InGef research database of statutory health insurances claims | - | ICD-10 coded: 3.79§; Predicted: 19.05§ | 5 | - | ICD-10 coded: 1.56 (D)§; Predicted: 15.33 (D)§ |

| Greece (January 2007 - May 2013)84 | Isolation: ≥ 1 isolate Disease: Full (12 pts) ATS criteria and ATS microbiologic criteria (56 pts) |

Sismanoglio-A. Fleming General Hospital of Attiki EHR data | - | - | 7 | - | Cumulative:18.9 (I); Cumulative: 8.8 (D)++ |

| Portugal (2002–2012)73 | Treatment for NTM-PD | National Tuberculosis Surveillance System database | - | - | 11 | - | 0.54 (D)# |

| Scotland (2000–2010)86 | ATS microbiologic criteria | Scottish Mycobacteria Reference Laboratory data | - | - | 11 | - | 2.43 (D)+**# |

| Serbia (2010–2015)74 | Isolation: 1 isolate Disease: ATS microbiologic criteria |

The National Reference Laboratory of Serbia database | - | 0.31 (2011–2012)–0.47 (2014–2015)+** | 6 | - | 1.3 (I); 0.29 (D)+** |

| Spain (1994 –2014)75 | Isolation: ≥ 1 isolate Disease: ≥2 positive cultures or antimicrobial chemotherapy |

Referral Hospital (Bellvitge University Hospital) Laboratory data | - | - | 21 | 113.2 (I)**; 42.8 (D)+++ ** | - |

| Spain (1994–2015)76 | Isolation: ≥ 1 isolate Disease: Full ATS criteria (only RGM) |

Referral Hospital (Bellvitge University Hospital) Laboratory data | - | - | 22 | - | 0.34–1.73 (2003–2015) (APC: 8.3%) (I)# |

| Spain (1997–2016)78 | Full ATS criteria | Microbiology Laboratory of Cruces University Hospital data | - | - | 20 | - | 10.6–1.8 (2016) (APC: 3.3% (MAC), −6.5% (M. kansasii)) (D) |

| The United Kingdom (2006–2016)79 | ‘Strict Cohort’, highly likely to have NTM-PD; ‘Expanded Cohort’ possible NTM-PD++++ | Clinical Practice Research Datalink | - | Strict Cohort: 7.68–4.70 (2006–2016)# | 10 | Strict Cohort: 6.38 (D)# | Strict Cohort: 3.85–1.28 (2006–2016) (D)#; Expanded Cohort: 22.9–40.9 (2006–2016) (D)# |

| The Netherlands (2012–2019)70 | Drug combination in drug dispensing database, ICD-10 | IQVIA’s Real-World Data Longitudinal Prescription database, Outpatient Pharmacy Database of the PHARMO Database Network, IQVIA’s health insurance claims database, Hospitalization Database of the PHARMO Database Network | - | 2.3–5.9 (databases); 6.2–9.9 (pulmonologist survey) | - | - | - |

| East Asia | |||||||

| Location (dates) | Case Definition | Data Source/Cohort | Annual Prevalence (per 100,000 population) | Period Prevalence | Incidence (per 100,000 population) | ||

| Isolation (dates) | Disease (dates) | Period Duration (years) | Prevalence (per 100,000 population) | ||||

| Japan (2001–2009)132 | Full ATS criteria | Microbiological database of 11 hospitals in Nagasaki prefecture | - | - | 9 | - | 4.6–10.1 (2001–2009) (D) |

| Japan (2004–2006)23 | ICD-8–10, estimated from Death Statistics | Vital Statistics of Japan database | - | 33–65 (2005)§ | - | - | - |

| Japan (2009–2014) 107 | ICD-10 | The Japanese National Database of Health Insurance Claims | - | 29 (2011) | 6 | - | 8.6 (2011) (D) |

| Japan (2012–2013)105 | ATS microbiologic criteria | 3 major laboratories (SRL, Inc., LSI Medience Corporation, BML, Inc.) | - | 12 (2012–2013)+** | 2 | 24 (D)+** | - |

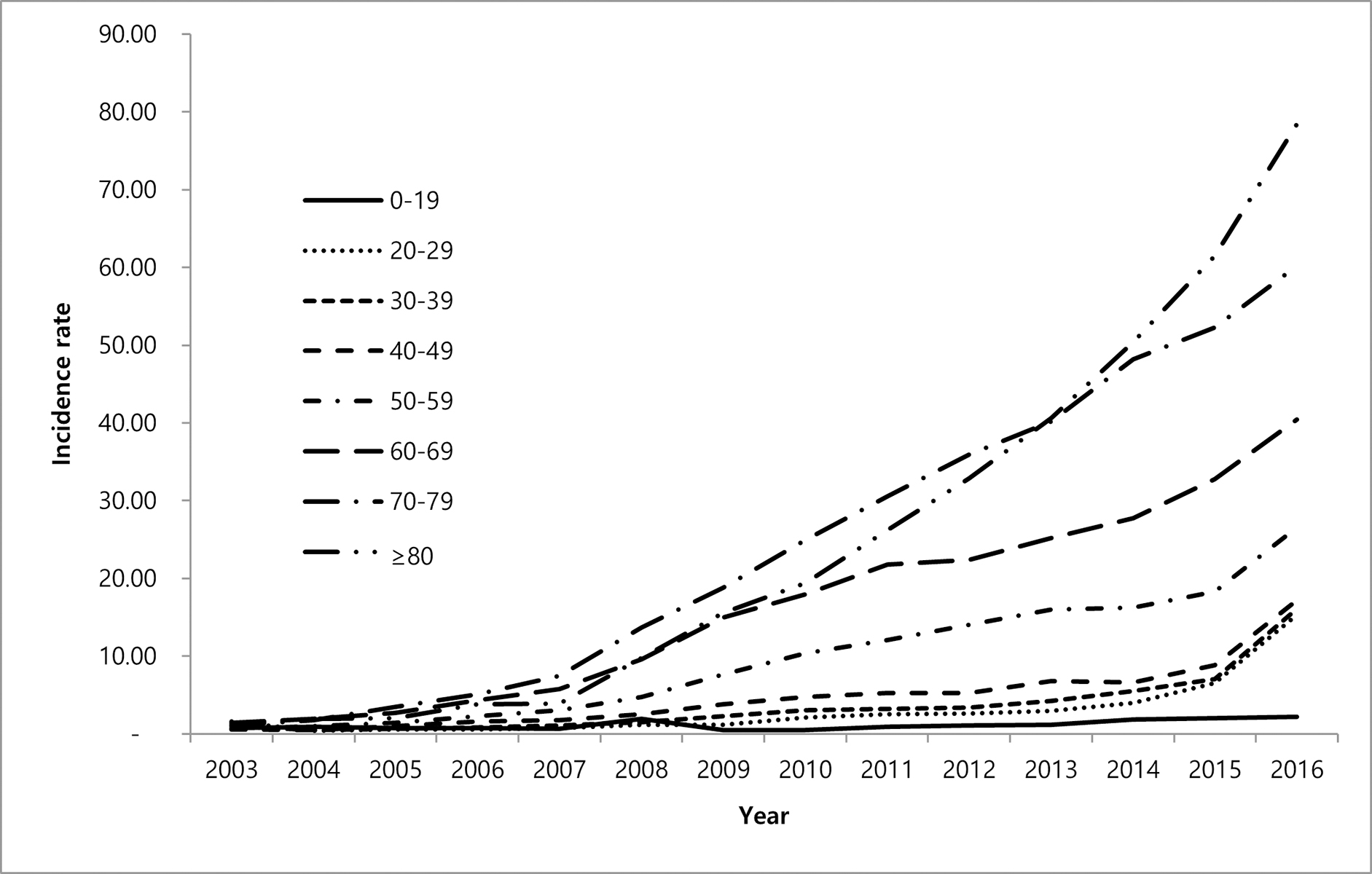

| South Korea (2001–2015)104 | Full ATS criteria | NTM Registry of Tertiary Referral Hospital (Samsung Medical Center) | - | - | 15 | - | 7.0–55.6 (2001–2015) (D) |

| South Korea (2003–2016)98 | ICD-10 | National Health Insurance Service database | - | 1.2–33.3§ | 14 | - | 1.0–17.9 (2003–2019) (D)§ |

| South Korea (2006–2016)100 | Full ATS criteria | Tertiary Referral Hospital (Severance Hospital) EHR data | - | - | 11 | - | 4.6–19.6 (2006–2016) (I); 1.2–4.8 (2006–2016) (APC: 14%) (D) |

| South Korea (2007–2018)99 | ICD-10 | Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service database | - | 5.3–41.7 | 12 | - | Diagnostic-based: 3.5–18.0 (2008–2018) (APC: 16.7%) (D); Clinically-refined: 2.9–12.3 (2008–2018) (APC: 13.2%) (D) |

| South Korea (2009–2015)133 | ICD-10 | Health Insurance Review and Assessment service database | - | - | 7 | - | 6.6–26.6 (2009–2015) (D) |

| South Korea (2009–2015)103 | Full ATS criteria | Tertiary care Hospitals (Pusan National University, Pusan National University Yangsan) EHR data | - | - | 7 | - | 6.8–12.9 (2009–2015) (D)# |

| Taiwan (2000–2012)115 | Full ATS criteria | Tertiary Medical Center (National Taiwan University) data | - | - | - | - | 3.4–13 (D) |

| Taiwan (2003–2018)113 | ICD-9-CM, treatment | National Health Insurance Research database | - | 0.68–7.17# (Treatment Case) | - | - | 0.54–3.35 (2003–2018) (D) (Treatment Case)# |

| Taiwan (2005–2013)112 | ICD-9-CM, ≥ 2 cultures, treatment | National Health Insurance Research database | - | - | - | - | 5.3–14.8 (2005–2013) (D)§# |

| Taiwan (2007–2010)114 | ≥ 1 isolate | National TB Registry of Taiwan CDC | - | - | - | - | 8.6 (I) |

| Taiwan (2010–2014)116 | Full ATS criteria | 6-Hospital EHR database | - | - | - | - | 46 (D) |

| West and Central Asia | |||||||

| Location (dates) | Case Definition | Data Source/Cohort | Annual Prevalence (per 100,000 population) | Period Prevalence | Incidence (per 100,000 population) | ||

| Isolation (dates) | Disease (dates) | Period Duration (years) | Prevalence (per 100,000 population) | ||||

| Iran (1990–2014)134 | - | - | - | - | 25 | 9.6–10.6 (D)# | - |

| Oceania | |||||||

| Location (dates) | Case Definition | Data Source/Cohort | Annual Prevalence (per 100,000 population) | Period Prevalence | Incidence (per 100,000 population) | ||

| Isolation (dates) | Disease (dates) | Period Duration (years) | Prevalence (per 100,000 population) | ||||

| Australia (2001–2016)41 | ≥ 1 isolate | Queensland Notifiable Conditions database | - | - | 16 | - | 11.1–25.88 (I)# |

| Australia (2012–2015)3 | ≥ 1 isolate | Queensland Notifiable Conditions database | - | - | 4 | - | 25.9 (I)# |

Rates expressed as annual rates per 100,000 population, averaged over study period unless otherwise specified

Studies which excluded M. gordonae

ICD-9 – International diagnostic classification of diseases – ninth revision

ICD-10 – International diagnostic classification of diseases – tenth revision

SGM – slow-growing mycobacteria

RGM – rapid-growing mycobacteria

EHR – electronic health records

APC – annual percent change

NTM-PD is defined using ATS microbiologic criteria

NTM-PD is defined using ATS microbiologic criteria and full ATS criteria

NTM-PD is defined ≥2 positive cultures or antimicrobial chemotherapy

‘Strict Cohort’ is defined using evidence of treatment and/or monitoring of NTM-PD and ‘expanded cohort’ is defined using NTM disease clinical terminology codes

Included patients with NTM isolated from extrapulmonary sites/specimens from extrapulmonary sites

Adjusted

Table 3:

NTM isolations from respiratory specimen (I) and NTM pulmonary disease (D) by species and region

| North America | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Location (dates) | N | Most Common Species (%) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Canada | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Ontario, Canada (1998–2010)131 | I: 2631 | MAC (50.5) | M. xenopi (21.6) | M. gordonae (12.8) | M. fortuitum (5.0) |

M. abscessus (2.2) M. chelonae (1.5) |

|

| ||||||

| Toronto, Ontario, Canada (2003–2019)60 | D: 252 | M. avium (87.3) | M. xenopi (12.7) | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| United States | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Florida (2011–2017)56 | I: 396 |

M. abscessus subsp. abscessus (31.8), M. abscessus subsp. bolletii (<1) M. abscessus subsp. massiliense (4.5) M. chelonae (1.8) |

M. gordonae (18.7) |

M. avium (1.6) M. chimaera (4.7) M. intracellulare (1.8) |

M. kansasii (4.7) | M. szulgai (3.9) |

|

| ||||||

| Hawaii (2005–2013)52 | 455 (I: 201, D: 254+) | MAC (63.7) | M. fortuitum (24.0) | M. abscessus (19.1) | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Hawaii (2005–2019)53 | I: 739 | MAC (69) | M. fortuitum group (24) | M. abscessus (21) | M. kansasii (2) | - |

|

| ||||||

| Illinois, U.S. (2000–2012)135 | I: 448 |

M. avium (54) M. chimera (28) M. intracellulare (18) |

- | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Iowa (1996–2017)136 | D: 185 | MAC (68.6) | M. kansasii (8.1) |

M. abscessus (7.6) M. chelonae (5.4) |

M. fortuitum (2.2); M. xenopi (2.2) | - |

|

| ||||||

| North Carolina (2006–2010)58 | I: 750 | MAC (50.9) | M. gordonae (20.4) | M. abscessus complex (13.6) | M. fortuitum (5) | M. mucogenicum (3.9) |

|

| ||||||

| Oregon (2007–2012)10 | I: 806 | M. avium/intracellulare complex (82.8) |

M. abscessus/chelonae complex (4.1) M. chelonae (<1) |

M. fortuitum complex (2.9) | M. lentiflavum (1.0) | M. kansasii (<1) |

| D: 1146+ | M. avium/intracellulare complex (85.7) |

M. abscessus/chelonae complex (5.9) M. chelonae (1.2) |

M. kansasii (1.2) | M. lentiflavum (1.0) | M. fortuitum complex (<1) | |

|

| ||||||

| U.S. (2009–2013)48 | I: 487 | MAC (77) | M. abscessus/M. chelonae (9) | M. kansasii (6) | M. fortuitum (5) | - |

|

| ||||||

| US-Affiliated Pacific Island Jurisdictions (2007–2011)54 | I: 35‡ | MAC (31.4) | M. fortuitum (20.0) | M. gordonae (14.3) | M. abscessus/ chelonae (5.7); M. parascrofulace um/M. fortuitum (5.7) | M. florentinum (2.9); M. kansasii (2.9); M. mucogenicum (2.9); M. paraffinicum (2.9); M. simiae (2.9); M. terrae (2.9) |

|

| ||||||

| Central and South America | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Location (dates) | N | Most Common Species (%) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Ceará, Brazil (2005–2016)65 | I: 42 | M. abscessus (4.8); M. avium (4.8); M. fortuitum (4.8) | M. kansasii (2.4); M. szulgai (2.4) | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| French Guiana (2008–2018)61 | I: 147 |

M. fortuitum (23) M. avium (52) |

M. avium (12) M. intracellulare (17) |

M. gordonae (5); M. scrofulaceum (5) | M. abscessus (3); M. smegmatis (3) | M. interjectum (2); M. kansasii (2) |

| D: 31 | M. intracellulare (29) | M. abscessus (16) | M. genavense (3) | - | - | |

|

| ||||||

| Mexico City, Mexico (2001–2017)62 | D: 66 | MAC (47) | M. abscessus (27.3); M. fortuitum (27.3) | M. kansasii (7.6); M. scrofulaceum (7.6) | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Panama (2012–2014)66 | I: 7 | M. avium (57.1) | M. haemophilum (28.6) | M. tusciae (14.3) | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (2003–2013)63 | D: 100 |

M. avium (26) M. intracellulare (9) |

M. kansasii (17) | M. abscessus (12) | M. fortuitum (4) | M. gordonae (3) |

|

| ||||||

| São Paulo, Brazil (2011–2014)64 | I: 2843 |

M. avium (18.3) M. intracellulare (14.9) |

M. kansasii (15.9) | M. gordonae (13.2) | M. fortuitum (10.9) |

M. abscessus (7.7) M. chelonae (3.4) |

| D: 448+ | M. kansasii (29.2) |

M. avium (20.8) M. intracellulare (19.6) |

M. abscessus (17.2) M. chelonae (<1) |

M. gordonae (4.5) | M. fortuitum (3.6) | |

|

| ||||||

| Uruguay (2006–2018)67 | I: 255† |

M. avium (23.9) M. intracellulare (33.7) |

M. kansasii (8.2) | M. gordonae (5.9) | M. peregrinum (4.7) |

M. abscessus (1.2) M. chelonae (3.1); M. fortuitum (3.1) |

|

| ||||||

| Europe | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Location (dates) | N | Most Common Species (%) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Belgium (2015–2018)137 | I: 264 |

M. avium (12.1) M. chimaera/M. intracellulare (20.8) |

M. abscessus (12.9) M. chelonae (6.1) |

M. gordonae (3.4) | M. fortuitum (1.9); M. xenopi (1.9) | M. paragordonae (1.5) |

|

| ||||||

| Belgium (2010–2017)138 | I: 384 |

M. avium (25) M. chimaera (4.4) M. intracellulare (16.7) M. marseillense (<1) |

M. gordonae (14.6) | M. xenopi (7.6) | M. fortuitum (3.9) |

M. abscessus (3.1) M. chelonae (2.9) |

| D: 165 |

M. avium (31.5) M. chimaera (4.2) M. intracellulare (24.8) M. marseillense (<1) |

M. xenopi (8.5) |

M. abscessus (6.7) M. chelonae (<1) |

M. kansasii (4.2) | M. malmoense (3.6) | |

|

| ||||||

| I: 1926 | M. gordonae (42.6) | M. xenopi (15.3) | M. fortuitum (11.4) | M. terrae (6.6) | M. abscessus (2.1) | |

|

| ||||||

| Croatia (2006–2015)139 | D: 137 | M. xenopi (39.4) |

M. avium (22.6) M. chimaera (1.5) M. intracellulare (14.6) |

M. kansasii (5.8) | M. abscessus (4.4) |

M. chelonae (5.0) M. fortuitum (1.5); M. gordonae (1.5) |

|

| ||||||

| Czech Republic (2012–2018)81 | I: 2176† | M. xenopi (36.4) | M. avium-intracellulare complex (17.7) | M. gordonae (15.7) | M. fortuitum (9.7) | M. kansasii (6.2) |

| D: 303† | M. avium-intracellulare complex (47.2) | M. kansasii (23.8) | M. xenopi (18.2) |

M. abscessus (1.3) M. chelonae (2.3) |

M. fortuitum (2); M. malmoense (2) | |

|

| ||||||

| England, Wales and Northern Ireland (January 2007-July 2012)77 | I: 16294 | MAC (35.6) | M. gordonae (16.7) |

M. abscessus (5.0) M. chelonae (9.7) |

M. fortuitum (8.2) | M. kansasii (5.9); M. xenopi (5.9) |

|

| ||||||

| France (2002–2013)140 | D: 92 |

M. avium (29.3) M. intracellulare (29.3) |

M. kansasii (17.4) | M. xenopi (16.3) | M. abscessus (2.2) | M. fortuitum (1.1) |

|

| ||||||

| France (2009–2014)141 | D: 477 |

M. avium (31.2) M. intracellulare (28.1) |

M. xenopi (19.7) | M. kansasii (5.7) |

M. abscessus complex (3.8) M. chelonae (<1) |

M. fortuitum (2.7) |

|

| ||||||

| Germany (2006–2016) 142 | I: 216 | MAC (33.3) | M. gordonae (23.6) | M. xenopi (15.2) | M. abscessus complex (9.3) | - |

|

| ||||||

| Greece (January 2007-May 2013)84 | I: 122 | M. gordonae (13.9) |

M. avium (13.1) M. intracellulare (9.8) |

M. fortuitum (12.2) | M. lentiflavum (4.9); M. peregrinum (4.9) |

M. abscessus (1.6) M. chelonae (2.4); M. xenopi (2.4) |

| D: 12 |

M. avium (25) M. intracellulare (25) |

M. abscessus (8.3); M. fortuitum (8.3); M. gordonae (8.3); M. xenopi (8.3) | - | - | - | |

|

| ||||||

| Ireland (January 2007-July 2012)143 | I: 37 |

M. avium (59.5) M. intracellulare (10.8) |

M. gordonae (10.8) |

M. abscessus (5.4) M. chelonae (5.4); M. szulgai (5.4) |

M. malmoense (2.7) | - |

|

| ||||||

| The Netherlands (2008 – 2013)144 | D: 63 |

M. avium (36.5) M. chimera (4.8) M. intracellulare (12.7) |

M. malmoense (11.1) | M. kansasii (9.5) | M. abscessus (6.3) | M. simiae (4.8) |

|

| ||||||

| Poland (2010–2015)145 | I: 73 |

M. avium (22) M. intracellulare (8); M. kansasii (22) |

M. gordonae (19) | M. xenopi (11) | M. fortuitum (6) | M. abscessus (3) |

| D: 36 | M. kansasii (36) |

M. avium (28) M. intracellulare (11) |

M. xenopi (8) | M. abscessus (6) | M. gordonae (3) | |

|

| ||||||

| Poland (2013–2017)146 | I: 2799† | M. kansasii (27.2) |

M. avium (22) M. intracellulare (6.2) |

M. xenopi (16) | M. gordonae (14.5) | M. fortuitum (5.9) |

|

| ||||||

| Portugal (2005–2014)147 | I: 365 | MAC (48.2) | M. gordonae (13.7) | M. peregrinum (11) |

M. abscessus (1.6) M. chelonae (7.9) |

M. kansasii (5.8) |

|

| ||||||

| Scotland (2000–2010)86 | I: 933 | MAC (44.8) | M. malmoense (21.7) |

M. abscessus (13.7) M. chelonae (2.6) |

M. xenopi (4.5) | M. kansasii (3.9) |

|

| ||||||

| Serbia (2009–2016)148 | I: 296† | M. gordonae (22.3) | M. fortuitum (21.3) | M. xenopi (13.5) | M. peregrinum (12.2) | MAC (9.8)) |

| D: 83 | MAC (30.1) | M. xenopi (24.1) | M. kansasii (18.1) | - | - | |

|

| ||||||

| Serbia (2010–2015)74 | I: 565 | M. xenopi (17.3) | M. gordonae (12.9) | M. fortuitum (11.3) |

M. abscessus (4.6) M. chelonae (4.1) |

M. kansasii (4.2) |

| D: 126+ | M. xenopi (28.6) |

M. abscessus (15.1) M. chelonae (2.4) |

M. kansasii (11.1) | M. fortuitum (10.3) |

M. avium (7.9) M. intracellulare (6.3) |

|

|

| ||||||

| Spain (1994–2014)75 | I: 680 | M. kansasii (28.5) | MAC (20.4) | M. xenopi (14.1) | M. abscessus (2.5) | - |

| D: 257** | M. kansasii (59.9) | MAC (26.1) | M. xenopi (6.2) | M. abscessus (4.3) | - | |

|

| ||||||

| Spain (1994–2015)76 (only RGM) | I:116 | M. fortuitum (45.7) |

M. abscessus (5.2) M. chelonae (33.6) |

M. mucogenicum (8.6) | M. mageritense (1.7); M. peregrinum (1.7) | - |

| D: 15 |

M. abscessus (40) M. chelonae (26.7) |

M. fortuitum (26.7) | M. mucogenicum (6.7) | - | - | |

|

| ||||||

| Spain (1997–2016)78 | D: 327 | M. kansasii (83.8) | MAC (13.1) | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Spain (2007–2013)149 | I: 156 D: 34+ |

MAC (64.1) MAC (79.4) |

M. gordonae (12.2) M. genavense (8.8) |

M. abscessus (1.9) M. chelonae (8.3) M. abscessus (2.9) M. chelonae (5.9) |

M. fortuitum (5.8) M. malmoense (2.9); M. xenopi (2.9) |

M. lentiflavum (4.5); M. scrofulaceum (4.5) - |

|

| ||||||

| Spain (2013–2017)150 | I: 314 |

M. avium (48.4) M. intracellulare (16.6) |

M. fortuitum (12.1) | M. gordonae (8.0) | M. lentiflavum (4.1) |

M. abscessus (<1) M. chelonae (3.2) |

|

| ||||||

| Switzerland (2015–2020)151 | I: 236† | M. gordonae (24.6) |

M. avium (23.3) M. chimera (3.4) M. intracellulare (6.8) |

M. xenopi (11.9) |

M. abscessus subsp. abscessus (6.4) M. chelonae (4.2) |

M. fortuitum (4.2) |

|

| ||||||

| The United Kingdom (2007–2014)152 | I: 853 |

M. avium (21.2) M. intracellulare (31.3) |

M. gordonae (15.2) |

M. abscessus (8.4) M. chelonae (8.4) |

M. xenopi (7.9) | M. malmoense (4.7) |

|

| ||||||

| Africa | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Location (dates) | N | Most Common Species (%) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Botswana (Aug 2012–Nov 2014) (HIV–infected)89 | I: 228 |

M. avium (2.2) M. intracellulare (47.8) |

M. gordonae (7) | M. malmoense (3.9) | M. simiae (3.5) | M. asiaticum (2.6); M. fortuitum (2.6); M. scrofulaceum (2.6) |

|

| ||||||

| Ethiopia (2017)93 | I: 35 | M. simiae (42.9) | M. abscessus complex (14.3) | M. fortuitum (11.4) |

M. avium complex (5.7) M. intracellulare (8.6); M. gordonae (8.6) |

M. kansasii (2.9); M. scrofulaceum (2.9); M. szulgai (2.9) |

|

| ||||||

| Gabon (Jan 2018–Dec 2020)97 | I: 137 |

M. avium (5.1) M. intracellulare (54) |

M. fortuitum (21.9) |

M. abscessus (6.6) M. chelonae (2.2) |

M. kansasii (4.4) | M. mucogenicum (1.5) |

|

| ||||||

| Ghana (2012–2014)90 | I: 43 |

M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis (30.2); M. colombiense (7); M. intracellulare (41.9) |

M. abscessus (11.3) | M. mucogenicum (7) | M. simiae (2.3) | - |

|

| ||||||

| Ghana (Jan 2013– Mar 2014)91 |

I: 38 | MAC (23.7) | M. chelonae complex (7.9); M. simiae (7.9) | M. fortuitum complex (5.3) | M. arupense (2.6); M. flavescens (2.6); M. kansasii (2.6); M. terrae (2.6) | - |

|

| ||||||

| Kenya (2020)94 | I: 146 | MAC (31) | M. fortuitum complex (20) | M. abscessus complex (14) | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Mali (2006–2013)92 | I:41 | M. avium (24.4) | M. specie (7.3) | M. simiae (4.9) | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Nigeria, Cameroon, Ghana (Jan-Dec 2017)153 | I: 14 | M. fortuitum (35.7) |

M. engbaekii (14.3); M. avium (7.1) M. colombiense (7.1) M. intracellulare (14.3) |

M. gordonae (7.1); M. paraense (7.1); M. peregrinum (7.1) | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Tanzania (Nov 2012–Jan 2013)95 | I: 36 | M. gordonae (16.7); M. interjectum (16.7) |

M. avium (5.5) M. colombiense (2.8) M. intracellulare (11.1) |

M. scrofulaceum (8.3) | M. fortuitum (5.5); M. kumamotonense (5.5) | - |

|

| ||||||

| Tanzania (Nov 2019 - Aug 2020)154 | I: 24 |

M. avium (8.3) M. intracellulare (16.7) |

M. abscessus subsp. abscessus (12.5) M. abscessus subsp. bolletii (4.2) |

M. fortuitum group (8.3) |

M. kansasii (4.2); M. simiae (4.2); M. szulgai (4.2) | - |

|

| ||||||

| Tunisia (2002–2016)88 | I: 30 | M. kansasii (23.3) | M. fortuitum (16.7); M. novocastrense (16.7) | M. chelonae (10) | M. gadium (6. 6); M. gordonae (6. 6) | M. flavescens (3.3); M. peregrinum (3.3); M. porcinum (3.3) |

|

| ||||||

| East Asia | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Location (dates) | N | Most Common Species (%) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| China (2008–2012)155 | I: 616 | M. kansasii (45) |

M. avium (3.6) M. intracellulare (20.8) |

M. chelonae-abscessus complex (14.9) | M. fortuitum (4.5) | - |

|

| ||||||

| China (2009–2019)156 | I: 1102 |

M. avium (13.2) M. intracellulare (54.8) |

M. chelonae-abscessus complex (16.5) | M. kansasii (8.2) | M. gordonae (3.3) | M. fortuitum (<1) |

|

| ||||||

| China (2010–2015)120 | I: 232 |

M. avium (4.7) M. intracellulare (40.5) |

M. abscessus (28.4) | M. kansasii (9.9) | M. fortuitum (8.6) | M. gordonae (4.3) |

| D: 72* |

M. avium (2.8) M. intracellulare (52.8) |

M. abscessus (33.3) | M. kansasii (9.7) | M. szulgai (1.4) | - | |

|

| ||||||

| China (2013–2016)157 | D: 607 |

M. avium (16.3) M. intracellulare (28.2) |

M. abscessus subsp. abscessus (23.9) M. abscessus subsp. massiliense (16.6) |

M. kansasii (10.0) | M. fortuitum (2.8) | M. gordonae (1.0) |

|

| ||||||

| China (2014–2021)119 | I: 1755 |

M. avium (7.8) M. intracellulare (51.6) |

M. abscessus (22.2) | M. kansasii (8.3) | M. fortuitum (2.1); M. gordonae (2.1) | M. paragordonae (1.3) |

|

| ||||||

| China (2015–2020)118 | I: 789 | M. abscessus (35.1) |

M. avium (6.8) M. intracellulare (12.8) |

M. fortuitum (10.1) | M. kansasii (10.0) | M. gordonae (9.4) |

|

| ||||||

| China (2017–2018)158 | D: 87 |

M. avium (11.5) M. intracellulare (70.1) |

M. chelonae-abscessus complex (11.5) | M. kansasii (7.5) | M. gordonae (1.1) | - |

|

| ||||||

| China (2018)159 | I: 24 |

M. avium (4.2) M. intracellulare (66.7) |

M. abscessus (12.5) | M. kansasii (8.3) | M. fortuitum (4.2); M. szulgai (4.2) | - |

|

| ||||||

| China (2019–2020)117 | D: 458 |

M. avium (8.5) M. intracellulare (52.6) |

M. abscessus complex (23.1) | M. kansasii (8.1) | M. szulgai (2.6) | - |

|

| ||||||

| Japan (2000–2013)108 | D: 592+ |

M. avium (70.6) M. intracellulare (22.3) |

- | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Japan (2001–2009)132 | D: 975 |

M. avium (42.6) M. intracellulare (44.3) |

M. abscessus (3.1) M. chelonae (<1) |

M. gordonae (2.1); M. kansasii (2.1) | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Japan (2006–2016)109 | I: 3620 | MAC (82.2) |

M. abscessus complex (4.5) M. chelonae (<1) |

M. kansasii (3.7) | M. fortuitum (2.1) | M. peregrinum (<1) |

| D: 2155+ | MAC (87.2) | M. abscessus complex (5.5) | M. kansasii (3.9) | M. fortuitum (1.3) | - | |

|

| ||||||

| Japan (2009–2015)160 | I: 416 |

M. abscessus (31) M. chelonae (11) |

M. avium (5) M. intracellulare (20) |

M. gordonae (18) | M. fortuitum (11) | - |

| D: 114 |

M. abscessus (36) M. chelonae (10) |

M. avium (6) M. intracellulare (27) |

M. fortuitum (10) | M. gordonae (6) | - | |

|

| ||||||

| Japan (2012–2013)105 | I: 26059 |

M. avium (61.8) M. intracellulare (31.1) |

M. kansasii (2.1) |

M. abscessus (2.0) M. chelonae (<1) |

M. fortuitum (1.1) | M. terrae (<1) |

| D: 7167+ |

M. avium (65.1) M. intracellulare (32.4) |

M. kansasii (3.4) | M. abscessus (2.7) | - | - | |

|

| ||||||

| South Korea (2001–2015)104 | D: 2329 | MAC (75) | M. abscessus (22) | M. kansasii (3) | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| South Korea (2006–2016)100 | D: 1017 | MAC (63.6) | M. abscessus complex (10.8) | M. fortuitum (2.1); M. kansasii (2.1) | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| South Korea (2007–2019)102 | I: 2807 |

M. avium (19.2) M. intracellulare (50.6) |

M. fortuitum complex (4.7) |

M. abscessus (4.5) M. chelonae (1.0) |

M. gordonae (3.5) | M. kansasii (1.1) |

|

| ||||||

| South Korea (2009–2015)103 | I: 5558 |

M. avium (23.1) M. intracellulare (38.9) |

M. abscessus (8.4) | M. kansasii (7.7) | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| South Korea (2014–2019)101 | I: 4962 |

M. avium (17.5) M. intracellulare (42.3) |

M. abscessus (7.0) M. chelonae (3.3) |

M. fortuitum (5.5) | M. kansasii (3.6) | M. mucogenicum (2.7) |

|

| ||||||

| Taiwan (2000–2012)115 | D: 3317 | MAC (41.5) |

M. abscessus (21.4) M. chelonae (9.4) |

M. fortuitum (13.4) | M. kansasii (7.1) | M. gordonae (5.0) |

|

| ||||||

| Taiwan (2007–2010)114 | I: 894 | MAC (32.4) |

M. abscessus complex (9.2) M. chelonae complex (17.6) |

M. fortuitum complex (17) | M. kansasii (9.8) | M. gordonae (7.0) |

|

| ||||||

| Taiwan (2010–2014)116 | D: 1674 | MAC (34.4) | M. abscessus (24.3) | M. kansasii (11) | M. fortuitum (9.8) | M. gordonae (4.7) |

|

| ||||||

| South & Southeast Asia | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Location (dates) | N | Most Common Species (%) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| India (1981–2020)161 | I: 2071 | MAC (18.9) |

M. abscessus (8.8) M. chelonae (10.3) |

M. fortuitum (9.8) | M. gordonae (6.9) | M. terrae (6.3) |

|

| ||||||

| India (2013–2015)126 | I: 209 |

M. abscessus (31.1) M. chelonae (8.1) |

M. fortuitum (20.6) |

M. avium (8.1) M. intracellulare (13.4) |

M. interjectum (4.3); M. simiae (4.3) | M. gordonae (3.3) |

|

| ||||||

| India (2014–2015)127 | I: 164 | M. chelonae (26.8) | M. fortuitum (12.8) | M. gordonae (9.1) | M. kansasii (6.1) | M. simiae (4.9) |

|

| ||||||

| India (2015–2020)125 | I: 43 |

M. abscessus complex (37.2) M. chelonae (2.3) |

M. fortuitum (23.3) |

M. chimaera (2.3) M. colombiense (2.3) M. intracellulare (7.0) M. marseillense (2.3) |

M. parascrofulace um (4.7); M. simiae (4.7) | - |

|

| ||||||

| Pakistan (2016–2019)122 | I: 169 | MAC (61) | M. abscessus (24) | M. fortuitum (5.5); M. kansasii (5.5) | M. gordonae (1.8); M. szulgai (1.8) | - |

|

| ||||||

| Singapore (2011–2012)162 | I: 511 |

M. abscessus (39.5) M. chelonae (1.8) |

M. fortuitum (16.6) | M. kansasii (15.5) | M. avium (15.1) | M. gordonae (7.0) |

|

| ||||||

| Singapore (2012–2016)163 | I: 2026† | M. chelonae-abscessus complex (49.9) | M. fortuitum (17) | MAC (15.4) | M. kansasii (11.5) | M. haemophilum (2.0) |

| D: 352 | M. chelonae-abscessus complex (56) | MAC (28.1) | M. fortuitum group (25.9) | M. kansasii (20.2) | M. scrofulaceum (2.3) | |

|

| ||||||

| West and Central Asia | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Location (dates) | N | Most Common Species (%) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Iran (2011–2017)124 | I: 236 | M. abscessus (19.1) | - | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Iran (2016–2018)123 | I: 95 | M. fortuitum (48.4) | M. simiae (16.8) | M. kansasii (15.7) | M. abscessus (7.3) | M. thermoresistibile (4.2) |

|

| ||||||

| Turkey (2015–2019)121 | I: 45† | M. fortuitum (24.4) |

M. abscessus (17.7) M. chelonae (8.9) |

M. lentiflavum (11.1); M. simiae (11.1) |

M. avium (4.4) M. intracellulare (8.9) |

M. gordonae (6.7) |

|

| ||||||

| Saudi Arabia (2006–2012)164 | I: 142 | MAC (35) | M. fortuitum (24) | M. chelonae-abscessus complex (17) | M. gordonae (6) | M. kansasii (4) |

| D: 40 | MAC (47.5) | M. abscessus (25) | M. kansasii (10) | M. fortuitum (7.5) | M. szulgai (5) | |

|

| ||||||

| Oceania | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Location (dates) | N | Most Common Species (%) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Australia (2001–2016)41 | I: 12219† |

M. avium (9.8) M. intracellulare (39.1) |

M. abscessus (8.5) M. chelonae (3.3) |

M. fortuitum (8.3) | M. kansasii (2.4) | - |

|

| ||||||

| French Polynesia (2008–2013)128 | I: 87† |

M. fortuitum (11.5) M. porcinum (18.4) M. senegalense (13.8) |

M. abscessus (29.9) M. bolletii (1.1) M. massiliense (1.1) |

M. mucogenicum complex (9.2) |

M. avium (1.1) M. chimaera (3.4) M.intracellular e (1.1) |

- |

|

| ||||||

| Papua New Guinea (2010–2012)129 | I: 9 |

M. avium (33.3) M. intracellulare (22.2); M. fortuitum (33.3) |

M. terrae (22.2) | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||

MAC – Mycobacterium avium complex

RGM – rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacterial species

Included only patients whose radiographic disease pattern could be classified as cavitary, bronochiectatic, or consolidative

≥2 positive cultures or antimicrobial chemotherapy

M. avium and M. intracellulare concurrently isolated

Included patients with NTM isolated from extrapulmonary sites/specimens from extrapulmonary sites

Sub-analysis of study population

NTM-PD defined using ATS microbiologic criteria

In Florida, a study using the statewide clinical network and defining cases based on a single ICD code found an increasing disease prevalence, from 14.3/100,000 in 2012 to 22.6/100,000 in 2018 55. A second study in Florida at a single large academic medical center with NTM defined by pulmonary isolation found that M. abscessus was the predominant species, representing 39.1% of pulmonary isolates 56 (Table 3). The finding of a predominance of M. abscessus in Florida is consistent with a recent study showing that the South had the highest proportion of M. abscessus isolates, and Florida had the highest 5-year period prevalence of M. abscessus (17%) 57.

A population-based study in three counties of North Carolina (Durham, Wake, and Orange) estimated the prevalence of NTM isolation from 2006 through 2010 using primarily laboratory reports, for an average annual isolation prevalence of 9.4/100,000 (excluding M. gordonae; 11.5 including M. gordonae)58. MAC comprised 50.9% of isolates, followed by M gordonae (20.4%) and M. abscessus complex (13.6) (Table 3) 58. Cumulative incidence of NTM isolation was 8.8/100,000 across Durham County, Orange County, and Wake County (Table 2) 38. A statewide study in Oregon from 2007 to 2012 used the ATS microbiologic criteria to define NTM-PD and found an average annual incidence of 5/100,000, ranging from 4.8/100,000 in 2007 to 5.6/100,000 in 2012 10. The predominant species were MAC (85.7%), followed by rapidly growing mycobacteria (8.1%: M. abscessus/chelonae complex; M. chelonae; M. fortuitum complex) 10 (Table 2, Table 3).

Ontario, Canada

A prior report59 showed a significant increase in NTM isolation and disease (ATS microbiologic criteria) from 1998–2010, based on analysis of isolates from the Public Health Ontario Laboratory, which represents approximately 95% of NTM isolates in Ontario. A more recent analysis in a subset of patients being treated for NTM-PD in a tertiary care center and who met the full ATS NTM disease diagnostic criteria found a significant increase in M. avium-PD between the periods 2009–2012 and 2015–2018 and no significant change in non-M. avium species in the same period, demonstrating that the increase in NTM-PD is being driven by M. avium 60.

Central and South America

We identified six studies published between 2014 and 2022 from French Guiana 61, Mexico 62, Brazil 63–65, and Panama 66. All studies, apart from one, were single-center studies. The results of these studies may be impacted by referral bias. In addition, many studies lack a denominator in a defined population, which the limits the comparability of results.

In French Guiana, a retrospective, observational study of three hospitals during the period 2008–2018, identified 178 patients with NTM positive sputum cultures and 31 patients with NTM-PD. Incidence of NTM isolation and disease was 6.17/100,000 and 1.07/1000,000. This study defined disease using the full ATS diagnostic criteria. M. avium (52%) was the most common species among patients with NTM-PD, followed by M. intracellulare (29%), and M. abscessus (16%). Among patients with NTM isolates, M. fortuitum (23%) was most commonly identified, followed by M. intracellulare (17%), and M. avium (12%) 61.

A single center, retrospective study in Mexico City identified 158 patients that met the ATS criteria. The average annual isolation incidence increased for slow growing species from 0.6/1,000 admissions (2001–2011) to 1.9/1,000 admissions (2012–2017) and for rapidly growing species from 0.3/1,000 admissions (2001–2011) to 1.1/1,000 admissions (2012–2017) (Table 2). From these patients, the most common species were MAC (47%), M. abscessus (27.3%), and M. fortuitum (27.3%) (Table 3) 62.

Many studies on NTM in Brazil occur at the state-level and evaluate patient records at large, state referral hospitals that treat TB and NTM-related diseases. A retrospective, single institution study of patients in the state of Rio Grande do Sul identified 100 patients that met the full ATS criteria for NTM-PD (2003– 2013). The most common NTM species were M. avium (26%), M. kansasii (17%), M. abscessus (12%), and M. intracellulare (9%) (Table 3) 63. In the state of São Paulo, 448 patients were identified as NTM-PD using the ATS microbiologic criteria. From these patients, M. kansasii (29.2%), M. avium (20.8%), M. intracellulare (19.6%), and M. abscessus (17.2%) were the most common species (Table 3) 64. In the state of Ceará, NTM was isolated from pulmonary samples from 42 patients between 2005 and 2016. A high proportion of isolates were not sent to the National Reference Laboratory for identification (81%). Of the species that were identified, the most common were M. avium (4.8%), M. fortuitum (4.8%), and M. abscessus (4.8%) (Table 3) 65.

A study at the national tuberculous laboratory in Montevideo, Uruguay identified 255 NTM isolates from 204 TB suspects during 2006–2018; 210 were collected from pulmonary samples. Most NTM isolates were identified as MAC species (57.6%), followed by M. kansasii (8.2%), M. gordonae (5.9%), and M. peregrinum (4.7%) (Table 3) 67.

Europe

Studies from ten European countries published between 2014 and 2022 have calculated the incidence or prevalence of NTM isolation and/or NTM-PD (Table 2). Data sets, study populations and identification methods of NTM-PD patients differed significantly, thus comparison of the incidence or prevalence is difficult. Some of these studies have also calculated trends over the respective study period: either a stable (Denmark 68, France 69, The Netherlands 70) or increasing NTM-isolation or NTM-PD incidence or prevalence (Germany 26, 71, 72, Portugal 73, Serbia 74, Spain 75, 76, UK 77) was seen. Decreasing incidences for NTM isolation as reported in one study from Spain 78 and one from UK 79 are explained by the dominating decrease in M. kansasii isolation and PD in the Bilbao region 78 and by the selection of the data source, e.g. primary care records, where the decrease of the incidence and prevalence of the strictly defined NTM-PD cases probably represented a shift of management of NTM-PD towards secondary care 79. Species isolated from respiratory secretions or causing NTM-PD varies widely among countries and even within countries (Table 3); of note are the high percentages of NTM-PD caused by M. xenopi in Croatia, Czech Republic and Serbia, by M. kansasii in Poland and some Spanish regions, and by M. malmoense in Scotland and The Netherlands, resembling isolation data published by the NTM-NET 80. A changing epidemiology of species causing NTM-PD over time is also noted in some regions 78, such that analysis of aggregate trends may obscure species-specific changes. In Europe COPD often is a concomitant disease, with a mean age around 60 years and a generally similar overall male: female sex distribution with some exceptions (Table 4).

Table 4:

Age and Sex distribution of NTM isolations from respiratory specimen (I) and NTM pulmonary disease (D) by Region

| North America | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Location (dates) | N | Mean Age (years) | Female (%) | COPD (%)/ Bronchiectasis (%)/History of TB (%) | Other Pulmonary Disease (%) |

|

| |||||

| Florida, U.S. (2011–2017)56 | I: 271 | 60.5 | 28.5 | 20.8/2.2/2.2 | Asthma (2.8), CF (11.1),ILD (3.6), Lung Cancer (7.5) |

|

| |||||

| Florida, U.S. (2012–2018)55 | D: 7963 (ICD-9/10) | - | 54 | 27.7/ 30.7/10.6 | CF (4.1) |

|

| |||||

| Hawaii, U.S. (2005– 2013)52 | I: 201 | 65.2 | 50 | 39.8/27.9/- | Lung Cancer (12) |

| D: 254+ | 66 | 57 | 43/44/- | Lung Cancer (11) | |

|

| |||||

| Hawaii, U.S. (2005–2019)53 | I: 739 | Median: 63 | 54 | -/-/- | - |

|

| |||||

| Illinois, U.S. (2000–2012)135 | I: 448 | 63.0 | 63 | 11–22#/-/5–9# | - |

|

| |||||

| Iowa, U.S. (1996–2017)136 | D: 185 | Median: 63 | 55 | 30.3/26.5/- | CF (7.6), ILD (5.9), Structural Lung Disease (60.5) |

|

| |||||

| North Carolina, U.S. (2006– 2010)58 | I: 750 | - | 41.2 | -/-/- | - |

|

| |||||

| North Carolina, U.S. (2006– 2010)38 | I: 507 | 60 | 51.8 | -/-/- | - |

|

| |||||

| Oregon, U.S. (2007–2012)10 | I: 806 | Median: 66 | 49.6 | -/-/- | - |

| D: 1146+ | Median: 69 | 55.7 | -/-/- | - | |

|

| |||||

| U.S. (2001– 2015)47 | I: 4676 (ICD-9/ICD-10) | - | 0.13 | 100/2.5/2.6 | Asthma (12.2), ILD (12.8), Lung Cancer (3.1) |

|

| |||||

| U.S. (2008– 2015)45 | D: 6280 (ICD-9/ICD-10) | 69 | 67.6 | 52.6/37/7 | Aspergillosis (3.0), Asthma (23.2), CF (1.7) |

|

| |||||

| U.S.-Affiliated Pacific Island Jurisdictions (2007–2011)54 | I: 35‡ | Median: 34.8 | 49.2 | 27.6/-/44.8 | - |

|

| |||||

|

| |||||

| Central & South America | |||||

|

| |||||

| Location (dates) | N | Mean Age (years) | Female (%) | COPD (%)/ Bronchiectasis (%)/History of TB (%) | Other Pulmonary Disease (%) |

|

| |||||

| Ceará, Brazil (2005–2016)65 | I: 69† | 38.6 | 26.1 | 11.9/-/73.8 | All (13)* |

|

| |||||

| French Guiana (2008–2018)61 | 178 (D: 31, I: 147) | 49 | 39.3 | 17/5/16 | Chronic Pulmonary Disease (33) |

|

| |||||

| Mexico City, Mexico (2001–2017)62 | D: 67 | Median: 52–61## | 48–50## | -/-/- | Any (13)* |

|

| |||||

| Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (2003–2013)63 | D: 100 | 54.6 | 49 | 17/22/85 | CF (1), Silicosis (1) |

|

| |||||

|

| |||||

| Europe | |||||

|

| |||||

| Location (dates) | N | Mean Age (years) | Female (%) | COPD (%)/ Bronchiectasis (%)/History of TB (%) | Other Pulmonary Disease (%) |

|

| |||||

| Belgium (2010–2017)138 | D: 165 | Median: 64 | 43 | 41.8/20/7.3 | Aspergillosis (4.2), CF (6.1), Prior NTM-PD (13.9) |

|

| |||||

| Croatia (2006–2015)139 | D: 137 | Median: 66 | 47.5 | 45.3/29.2/27.7 | Asthma (2.2), Prior NTM-PD (5.1) |

|

| |||||

| France (2002–2013)140 | D: 92 | Median: 61.5 | 42.4 | 14.1/17.4/12 | All (46.7)* |

|

| |||||

| France (2009–2014)141 | D: 477 | Median: 65 | 29.6–56.2# | -/-/31.4 | All (68)* |

|

| |||||

| France (2010–2017)69 | D: 5628 (ICD–10 or suggestive medication) | 60.9 | 47.1 | 18.8/10.6/14.1 | CF (3.2), Lung Cancer (5.7) |

|

| |||||

| Germany (2009–2014)72 | D: 85–126 per year (ICD-10) (2009–2014) | 55–61 (2009–2014) | 43.4–52.9 (2009–2014) | 62.4–79.2 (2009–2014)/6.6–18.3 (2009–2014)/13.5–24 (2009–2014) | Asthma (20.8–29.2) (2009–2014), Lung Cancer (3.5–10.3) (2009–2014) |

|

| |||||

| Germany (2010–2011)26 | D: 125 (ICD–10) | 49.8 | 50.4 | - | - |

|

| |||||

| Germany (2011–2016)71 | D: 218 (ICD-10, German modification) | 61.4 | 41.3 | 46.3/10.1/17 | Asthma (25.2). ILD (3.7) |

|

| |||||

| Greece (January 2007–May 2013)84 | I: 62 | – | – | 42/35/13 | Asthma (6.4) CF (1.6) |

| D: 12 | - | - | 50/25/41 | Asthma (8.3) | |

|

| |||||

| The Netherlands (2008–2013)144 | D: 63 | 60.8 | 50.8 | 66.7–71.4#/-/10.5–14.3# | Asthma (1.6–15.8#), Lung Cancer (5.3–14.3#) |

|

| |||||

| Poland (2010–2015)145 | D: 36 | 58.5 | 83.3 | 19/33/28 | Asthma (6), CF (8), ILD (28), Lung Cancer (16.7) |

|

| |||||

| Portugal (2002–2012)73 | D: 632 (NTM–PD treatment)† | Median: 54 | 39.7 | 6.3/-/- | ILD (3.3) |

|

| |||||

| Serbia (2009–2016)148 | D: 85† | 59.2 | 34.1 | 40/10/13 | - |

|

| |||||

| Serbia (2010–2015)74 | D: 126+ | 65.4 | 47.6 | - | - |

|

| |||||

| Spain (1997–2016)78 | D: 327 | 56.8 | 28.8 | 30.1/29.3/- | Any (56)* |

|

| |||||

| The United Kingdom (2007–2014)152 | D: 112 | 65 | 51.8 | 44.5/38.4/9.8 | Asthma (16.9), ILD (5.4) |

|

| |||||

|

| |||||

| East Asia | |||||

|

| |||||

| Location (dates) | N | Mean Age (years) | Female (%) | COPD (%)/ Bronchiectasis (%)/History of TB (%) | Other Pulmonary Disease (%) |

|

| |||||

| China (2010–2015)120 | D: 72 | 54.1 | 47.2 | 8.3/6.9/15.3 | Silicosis (2.8) |

|

| |||||

| China (2013–2016)157 | D: 607 | - | 56.2 | 4.1/58.6/59.6 | - |

|

| |||||

| China (2014–2021)119 | I: 1755 | - | 53.6 | -/-/- | - |

|

| |||||

| China (2015–2020)118 | I: 789 | Median: 36 | 39.0 | -/-/22.4 | - |

|

| |||||

| China (2017–2018)158 | D: 87 | Median: 60 | 41.4 | 6.9/19.5/64.4 | - |

|

| |||||

| China (2019–2020)117 | D: 458 | - | 34.9 | 9.2/26.2/45.6 | Asthma (2.2) |

|

| |||||

| Japan (2004–2006)23 | D: 309 (ICD-8–10, estimated from Death Statistics) | 67 | 64.7 | 3.2/4.2/19.1 | Asthma (3.2), ILD (1.3), Lung Cancer (1.3) |

|

| |||||

| Japan (1999–2010)165 | D: 782 | 68.1 | 68.5 | 4.3/-/11.6 | ILD (3.5) |

|

| |||||

| Japan (2000–2013)108 | D: 592+ | 66.0 | 61.1 | 6.4/-/9.5 | Asthma (6.3), ILD (6.6) |

|

| |||||

| Japan (2001–2009)132 | D: 975 | 71.2 | 69.7 | 5.8/0.3/13.5 | Asthma (1.8), ILD (4.0), Lung Cancer (5.5), Silicosis (1.3) |

|

| |||||

| Japan (2006–2016)109 | D: 2155+ | Median: 69 | 66.5 | -/-/- | - |

|

| |||||

| Japan (2009–2014)107 | D (Incident):11034 (2011) (ICD-10) | 69.3 | 69.6 | 6.9/23.5 /6.3 | Aspergillosis (6.1), ILD (9.9), Lung Cancer (5.3) |

|

| |||||

| Japan (2009–2015)160 | D: 114 | Median: 74–78.5# | 59–68# | (5–24)#/(11–15)#/(16–17)# | Asthma (8–17)#, ILD (5–8)# |

|

| |||||

| Japan (2013–2015)166 | D: 184++ | 69.5 | 75.5 | -/5.4/8.2 | - |

|

| |||||

| Japan (2012–2013)105 | D: 7167+ | 73.6** | 65.5** | -/-/- | - |

|

| |||||

| Japan (2014)167 | D: 419 (ICD–10) | Median: 59 | 68 | 3.1/-/- | Aspergillosis (1.9), Asthma (18.3), DPB (1.6), ILD (6.0), Lung Cancer (4.5) |

|

| |||||

| South Korea (2001–2015)104 | D: 2329 | Median: 60 | 59 | -/-/- | - |

|

| |||||

| South Korea (2003–2016)98 | D: 46194 (ICD–10) | 55.8 | 61.1 | -/-/- | - |

|

| |||||

| South Korea (2006–2016)100 | D: 1017 | 62.7 | 58.8 | 13.5/83.9/48.3 | Asthma (7.3), Lung Cancer (4.0) |

|

| |||||

| South Korea (2007–2018)99 | D: 45321 (ICD–10) | - | 56.9 | -/-/- | - |

|

| |||||

| South Korea (2007–2019)102 | I: 2984† | - | 42.3 | -/-/- | - |

|

| |||||

| South Korea (2009–2015)133 | D: 52551 (ICD-10)† | 53.0 | 57.2 | 25.6/21.9/33.7 | Asthma (33.2), ILD (2.6), Lung Cancer (5.8) |

|

| |||||

| Taiwan (2000–2012)115 | D: 3317 | - | 42.3 | -/-/- | - |

|

| |||||

| Taiwan (2003–2018)113 | D(treatment case): 558 (ICD-9-CM)† | 62.5 | 42.5 | -/-/- | Chronic Lung Disease (42.8) |

|

| |||||

| Taiwan (2005–2013)112 | D: 450 (ICD-9-CM)† | - | 38 | -/-/- | - |

|

| |||||

| Taiwan (2007–2010)114 | I: 894 | - | 44.4 | -/-/- | - |

|

| |||||

| Taiwan (2010–2014)116 | D: 1674 | - | 44.3 | 23.4/15.6/25.4 | Asthma (5.2), ILD (6) |

|

| |||||

|

| |||||

| South-Southeast Asia | |||||

|

| |||||

| Location (dates) | N | Mean Age (years) | Female (%) | COPD (%)/ Bronchiectasis (%)/History of TB (%) | Other Pulmonary Disease (%) |

|

| |||||

| India (1981–2020)161 | D: 365 | - | 44 | -/3/65 | - |

|

| |||||

| India (2013–2015)126 | I: 263† | Median: 48 | 39.5 | -/-/- | - |

|

| |||||

| India (2015–2020)125 | I: 105† | - | 50.5 | 5.7/-/16.2 | - |

|

| |||||

| Pakistan (2016–2019)122 | I: 169 | Median: 45 | 39 | -/-/65 | - |

|

| |||||

| Singapore (2011–2012)162 | I: 485 | Median: 70 | 37.9 | 14.2/28.7/34.4 | Asthma (6.6); ILD (3.7) |

|

| |||||

| Singapore (2012–2016)163 | D: 352 | Median: 67 | 48.3 | 13.1/36.4/27.6 | Asthma (4.0) |

|

| |||||

|

| |||||

| Central & West Asia | |||||

|

| |||||

| Location (dates) | N | Mean Age (years) | Female (%) | COPD (%)/ Bronchiectasis (%)/History of TB (%) | Other Pulmonary Disease (%) |

|

| |||||

| Iran (2016–2018)123 | I: 95 | 47.4 | 42.1 | -/-/- | - |

|

| |||||

| Saudi Arabia (2006–2012)164 | D: 40 | 54 | 42 | 7.5/15/12 | Asthma (15), CF (2.5), ILD (10) |

|

| |||||

|

| |||||

| Oceania | |||||

|

| |||||

| Location (dates) | N | Mean Age (years) | Female (%) | COPD (%)/ Bronchiectasis (%)/History of TB (%) | Other Pulmonary Disease (%) |

|

| |||||

| Australia (2001–2016)41 | I: 12219† | Median: 66 | 50.1 | -/-/- | - |

|

| |||||

| Australia (2012–2015)3 | I: 1222† | Median: 66 | 51 | -/-/- | - |

|

| |||||

| Papua New Guinea (2010–2012)129 | I: 9 | 35.7 | 88.9 | -/-/- | - |

ICD-9 – International diagnostic classification of diseases – ninth revision

ICD-10 – International diagnostic classification of diseases – tenth revision

COPD – Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

TB – Tuberculosis

SGM – slow-growing nontuberculous mycobacteria

RGM – rapid-growing nontuberculous mycobacteria

ILD – Interstitial lung disease

DPB – Diffuse panbrochiolitis

CF – Cystic Fibrosis

All pulmonary comorbidities, including COPD, Bronchiectasis, History of TB

MAC patients only

Included patients with NTM isolated from extrapulmonary sites/specimens from extrapulmonary sites

NTM-PD defined using ATS microbiologic criteria

NTM-PD defined using full ATS criteria or 2008 Japanese Society for Tuberculosis/Japanese Respiratory Society Guidelines for the diagnosis of NTM pulmonary infection

Range by NTM species

Range by RGM and SGM

Sub-analysis of study population

Czech Republic

NTM isolates from the Public Health Institute Ostrava representing the Moravian and Silesian Regions from eastern Czech Republic were classified according to ATS diagnostic criteria and the incidence of each NTM species presented as average annual incidence in the studied period 2012–2018: The average incidence of NTM-PD patients was 1.10/100,000 (1.33/100,000 in men and 0.88/100,000 in women) during the study period, with MAC-PD patients predominantly women and M. kansasii-PD and M. xenopi-PD predominantly men, with distinct epidemiology in local districts 81.

Denmark