Abstract

In this quality improvement initiative, we aimed to increase provider adherence with palivizumab administration guidelines for hospitalized infants with hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease. We included 470 infants over four respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) seasons from 11/2017–03/2021 (baseline season: 11/2017–03/2018). Interventions included: education, including palivizumab in the sign-out template, identifying a pharmacy expert, and a text alert (seasons 1 and 2: 11/2018–03/2020) that was replaced by an electronic health record (EHR) best practice alert (BPA) in season 3 (11/2020–03/2021). The text alert and BPA prompted providers to add “Need for RSV immunoprophylaxis” to the EHR problem list. The outcome metric was the percentage of eligible patients administered palivizumab prior to discharge. The process metric was the percentage of eligible patients with “Need for RSV immunoprophylaxis” on the EHR problem list. The balancing metric was the percentage of palivizumab doses administered to ineligible patients. A statistical process control P-chart was used to analyze the outcome metric. The mean percentage of eligible patients who received palivizumab prior to hospital discharge increased significantly from 70.1% (82/117) to 90.0% (86/96) in season 1 and to 97.9% (140/143) in season 3. Palivizumab guideline adherence was as high or higher for those with “Need for RSV immunoprophylaxis” on the problem list than for those without it in most time periods. The percentage of inappropriate palivizumab doses decreased from 5.7% (n=5) at baseline to 4.4% (n=4) in season 1 and 0.0% (n=0) in season 3. Through this initiative, we improved adherence with palivizumab administration guidelines for eligible infants prior to hospital discharge.

Keywords: Respiratory syncytial virus infections, Palivizumab, Quality improvement, Cardiac disease, Provider adherence

INTRODUCTION

Infants and young children with hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease are one of the highest risk groups for morbidity and mortality from respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection[1–3]. They have a 3-fold increase in the odds of requiring intensive care unit admission among children hospitalized for RSV[4]. . Palivizumab, a monoclonal antibody against RSV, decreases RSV-related hospitalizations in high-risk patients by more than 50%[5, 6]. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends monthly administration of palivizumab for high-risk patients during periods of high RSV activity, typically from November to March (the RSV season)[7]. For eligible inpatients, administration is recommended two to three days prior to hospital discharge to minimize morbidity and hospitalizations from community-acquired RSV infection[7]. Patients receiving prophylaxis who undergo cardiopulmonary bypass or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and continue to be eligible are also recommended to receive a dose while inpatient[7].

Provider adherence with the AAP recommendations in the outpatient setting varies considerably, with rates reported between 25 and 100%[8]. Multiple approaches have been successfully implemented in the outpatient setting to improve palivizumab guideline adherence, including increased pharmacist involvement, home administration programs, and electronic clinical decision support[9–12]. Few initiatives have been aimed at improving adherence in the inpatient setting[13–15], and none have focused specifically on cardiac patients[16, 17]. At our center, provider adherence with palivizumab administration guidelines on the inpatient cardiology service, the Cardiac Care Unit (CCU), was found to be low at 70.1%.

We sought to develop a sustainable process to increase adherence with palivizumab administration for eligible inpatients with cardiac disease. Based on the success of various outpatient approaches in the literature, we hypothesized that inpatient adherence could be improved with a multi-faceted approach, including electronic health record (EHR)-based interventions, increased pharmacist involvement, and regular CCU meetings to improve education. Our Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-Bound (SMART) aim was to ensure that 95% of eligible inpatients received a dose of palivizumab prior to discharge from the CCU by March 31, 2021.

METHODS

Context

We conducted this quality improvement (QI) initiative at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and included children aged < 12 months discharged from the CCU. The medical team caring for inpatient cardiology patients consists of an attending physician, a fellow physician, front-line clinicians (nurse practitioners, hospitalists, and residents), and nurses. The CCU has 1300–1500 encounters per year and treats patients with congenital heart disease, heart failure/transplant, arrhythmias, and pulmonary hypertension.

Our center’s operational definition of hemodynamically significant heart disease and indications for receiving palivizumab prophylaxis relating to congenital heart disease include:

- Infants < 1 year of age with documented hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease who are receiving medication OR may require medication after discharge to control pulmonary overcirculation, atrioventricular valve regurgitation, or ventricular dysfunction (maintenance diuretics, digoxin, and/or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors) OR will require cardiac surgical procedures. The following exceptions DO NOT qualify:

- Infants and children with hemodynamically insignificant heart disease (e.g., atrial septal defect, small ventricular septal defect, pulmonic stenosis, uncomplicated aortic stenosis, mild coarctation of the aorta and patent ductus arteriosus)

- Infants without residual lesions after surgical repair unless they continue to require medication for the above reasons. Please NOTE: Certain patients with defects that will require further palliation would continue to qualify for palivizumab even if they are not on cardiac medications (e.g., hypoplastic left heart syndrome).

- Infants with mild cardiomyopathy who are not receiving medical therapy for the condition

Infants with moderate to severe pulmonary hypertension receiving phosphodiesterase inhibitors, endothelin receptor antagonists, or prostacyclins

Infants and children < 2 years of age with congenital heart disease who undergo cardiac transplantation during RSV season

Planning the interventions

Prior to this initiative, there were few systematic methods in place to support adherence with palivizumab administration. When an order for palivizumab was placed in the EHR, the eligibility criteria were displayed. Adherence with palivizumab guidelines was otherwise dependent on individual team member’s recognition of eligibility.

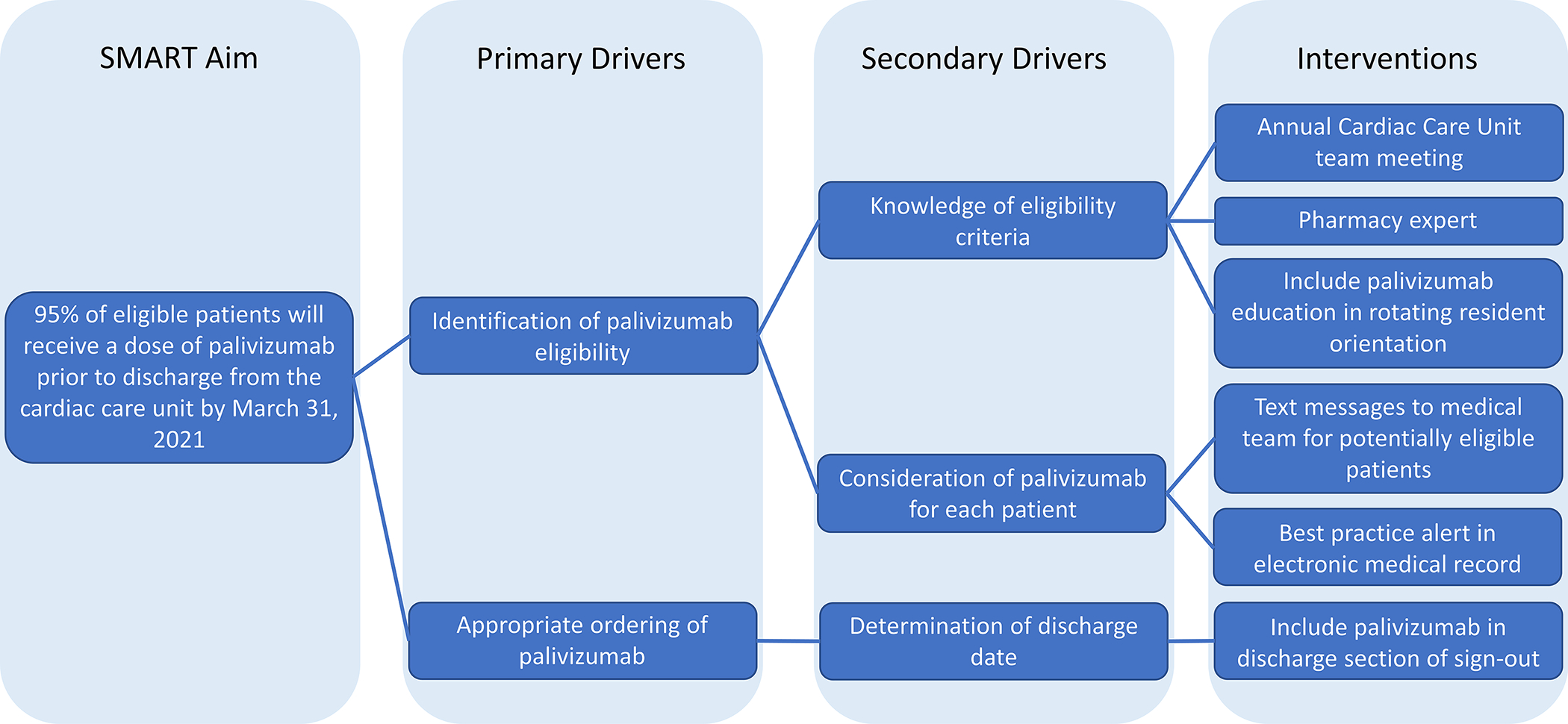

We assembled a multidisciplinary QI team consisting of cardiologists, nurse practitioners from the front-line clinical team, nurses, and pharmacists. The members of the team reviewed and were in agreement regarding the operational definition of hemodynamically significant heart disease, as defined above. We performed a retrospective chart review to assess baseline palivizumab guideline adherence and missed doses during the 2017/2018 RSV season. The QI team evaluated leading factors that influenced the missed doses and determined key drivers based on published data and multi-disciplinary discussions (Fig. 1). The team determined that the primary drivers of palivizumab adherence were identification of eligible patients and appropriate ordering of palivizumab. The team developed interventions to address these key drivers. The team communicated monthly regarding palivizumab adherence in the CCU during the RSV season and met yearly at the beginning of the RSV season to review the prior year and discuss the planned interventions for the upcoming season.

Fig. 1.

Key driver diagram

Interventions

The first primary driver—identification of palivizumab eligibility—was believed to be driven by both knowledge of eligibility criteria and consideration of palivizumab for each patient. In season 1, to increase knowledge of eligibility criteria, we developed a CCU team education meeting to be held at the beginning of each RSV season that included front-line clinicians and nurses to review the AAP criteria for palivizumab administration. We also identified a palivizumab pharmacy expert who was available to the care team for support in complying with the palivizumab guidelines.

To address consideration for individual patients, based on the success of electronic clinical decision support methods to improve palivizumab adherence in the outpatient setting[10, 11] and in the CHOP neonatal intensive care unit (unpublished), we hypothesized that EHR-based interventions would have the largest impact. At our center, all inpatient palivizumab doses are given two to three days prior to discharge, including for those who have undergone bypass or extracorporeal membrane support during admission. Because the order for palivizumab could only be placed once the discharge date was known, we focused our interventions on encouraging providers to use the problem list to document eligibility. The multidisciplinary QI team manually reviewed the EHR to identify current inpatients potentially eligible for palivizumab. Text message alerts were generated by one member of the QI team each week (MJC) and sent to the CCU fellow physician identifying potentially eligible patients and encouraging the addition of “Need for RSV immunoprophylaxis” on the problem list, if appropriate, to serve as a prominent reminder of the indication for monthly palivizumab administration for any provider accessing the EMR (Online Fig. 1).

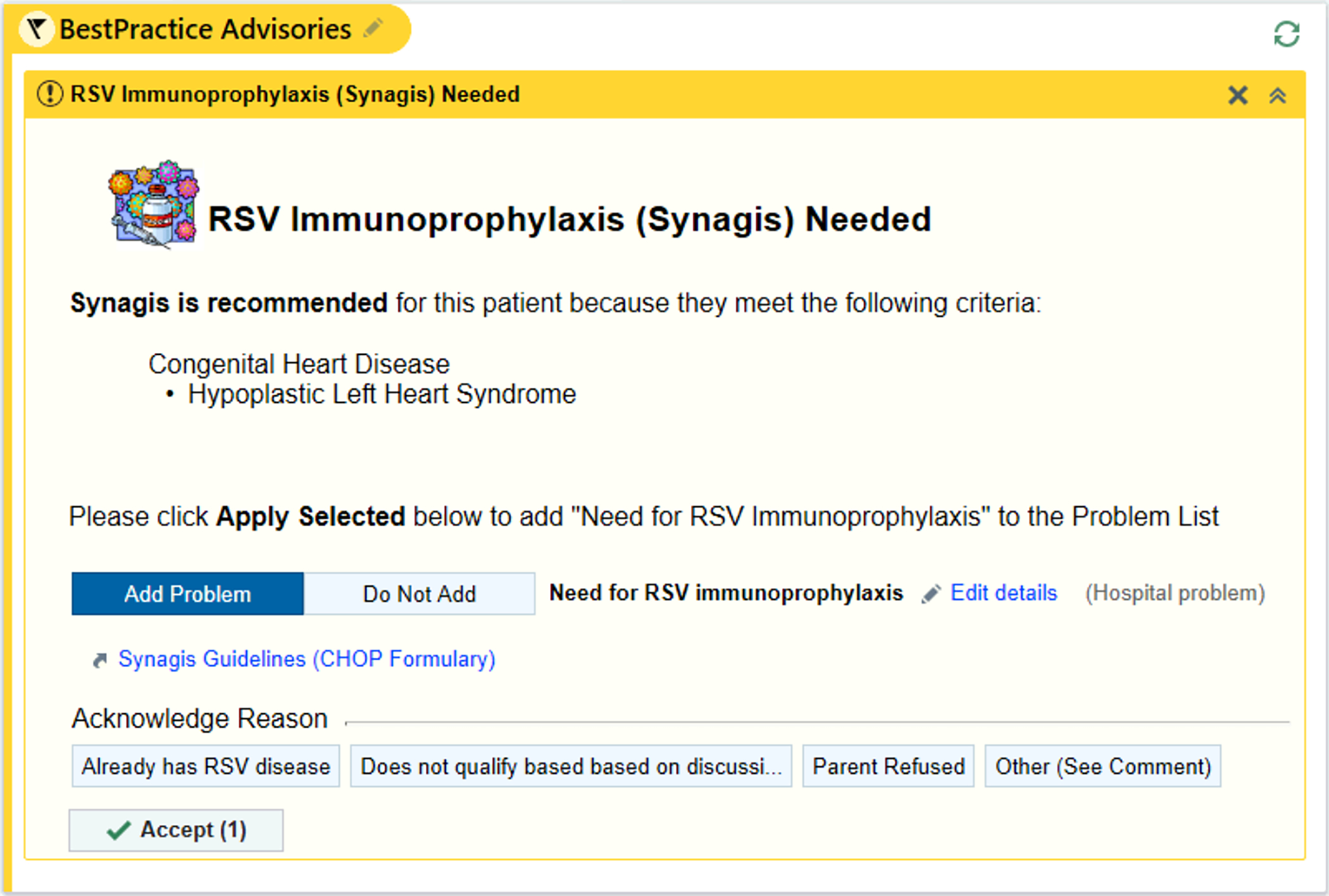

In season 3, to increase knowledge of eligibility criteria, we also included palivizumab education in orientation for pediatric residents at the beginning of their CCU rotation throughout the RSV season. To address consideration of palivizumab for individual patients, an EHR-based best practice alert (BPA) replaced the text message alerts established in season 1 for all patients < 12 months of age based on ICD-10 codes (Fig. 2; Online Table 1). The BPA prompted the clinician to add “Need for RSV immunoprophylaxis” to the problem list if appropriate. The BPA was formatted as a passive BPA that could be dismissed if the clinician was not the appropriate person to determine need for RSV immunoprophylaxis for that patient. The BPA was active year-round to capture patients born outside of RSV season who would be eligible for palivizumab in the first year of life.

Fig. 2.

Best practice alert example for possible eligibility for palivizumab. © 2021 Epic Systems Corporation

The team believed the barrier for the second primary driver—appropriate ordering of palivizumab—was driven by limitations in forethought for the date of discharge. To address this barrier, in season 1, we added a palivizumab line item to the EHR-based sign-out template for each patient used by front-line clinicians to guide their daily work. In this way, front-line clinicians were reminded to order palivizumab as part of the discharge planning process without a change to their workflow.

Interventions were undertaken in phases based on perceived impact and effort and were re-evaluated regularly. Data were collected every two weeks to allow for timely identification of periods of low adherence and adjustment of interventions, if needed. At the end of each season, the data were analyzed in full by the QI team and the interventions for the next season were planned.

Season 1 (November 2018 – March 2019):

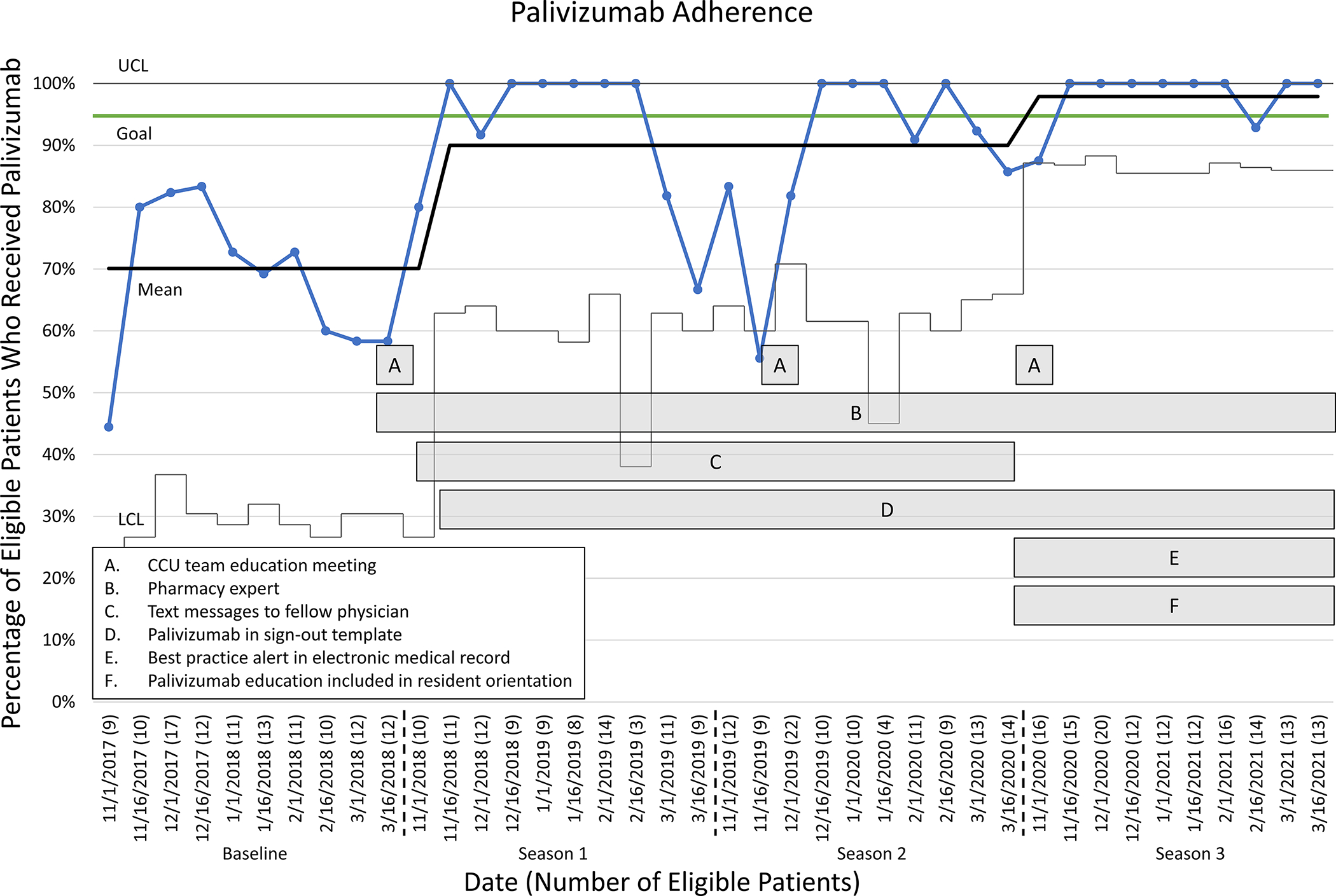

We implemented the CCU team education meeting (A on Fig. 3) and identified a pharmacy expert prior to the start of the 2018/2019 season (B on Fig. 3). Approximately two weeks later, we implemented weekly text message alerts to the CCU fellow physician (C on Fig. 3), and in late November 2018, we added palivizumab to the EHR-based sign-out template (D on Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Statistical Process Control (SPC) chart demonstrating palivizumab guideline adherence and interventions. CCU: Cardiac Care Unit; LCL: lower control limit; UCL: upper control limit.

Season 2 (November 2019 – March 2020):

The interventions from season 1 continued and no further interventions were implemented.

Season 3 (November 2020 – March 2021):

The BPA was implemented to replace the text message alerts to the fellow physician (E on Fig. 3). The resident schedules changed from four-week rotations to two-week rotations in this season and there was concern that the high turnover would affect palivizumab adherence, so palivizumab education was also preemptively incorporated into the resident orientation to the CCU (F on Fig. 3). The other interventions from season 1 continued.

Study of the Interventions

The QI team conducted a retrospective chart review for all patients < 12 months of age at discharge from the CCU and completed a before-after intervention comparison for adherence with palivizumab administration guidelines between the baseline season (11/2017–03/2018) and subsequent RSV seasons during which interventions were implemented (seasons 1 – 3). We reviewed data from the EHR, including patient age, diagnosis, discharge medications, discharge oxygen saturation, and history of RSV infection to determine eligibility for palivizumab based on our center’s operational definition of hemodynamically significant heart disease. We also collected data on addition of “Need for RSV immunoprophylaxis” on the problem list, date of palivizumab administration, and reason for lack of administration for analysis.

Measures

The primary outcome metric was palivizumab guideline adherence, defined as the percentage of patients eligible for palivizumab who received a dose prior to discharge. The primary process metric was the percentage of patients eligible for palivizumab who had “Need for RSV immunoprophylaxis” on their problem list to analyze the impact of the text message alerts and BPA on the primary outcome metric. The balancing metric was the percentage of total doses of palivizumab administered to ineligible patients.

Analysis

A statistical process control (SPC) P-chart was used to analyze the primary outcome metric, and Nelson’s rules for control charts were used to distinguish between common cause and special cause variation[18]. A two-week time interval was chosen for the x-axis to allow for special cause variation to be detectable in one RSV season. A run chart was used to assess the process metric, the rate of “Need for RSV Immunoprophylaxis” on the problem list over time. Due to small sample size, Nelson’s rules were not applied. The balancing metric was compared by RSV season.

Ethical considerations

This Quality Improvement Initiative was reviewed and determined to not meet the criteria for human subjects’ research by the CHOP Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

During the RSV seasons from November 2017 to March 2021, 770 infants under the age of 12 months were discharged from the CCU, 470 of whom were eligible for palivizumab administration. In the baseline season, there were 117 eligible infants. In seasons 1, 2, and 3, there were 96, 114, and 143 eligible patients, respectively. All 470 patients had complete data. The SPC chart demonstrates improvement in palivizumab guideline adherence as interventions were incorporated (Fig. 3). During the baseline season, the mean adherence with palivizumab administration guidelines was 70.1% (82/117). Two instances of special cause variation were identified which resulted in a shift to a new process mean. The first shift, an increase in mean adherence to 90.0% (86/96), occurred at the beginning of season 1 with the initiation of the CCU team education meeting at the beginning of each RSV season, addition of palivizumab to the sign-out template, identification of a pharmacy expert, and text message alerts to the CCU fellow physician. At the beginning of season 1, the adherence for most of the two-week intervals was 100%, although there was a decrease at the end of season 1 to as low as 66.7% (6/9) in the final two weeks that did not meet special cause. At the beginning of season 2, adherence remained low, reaching 55.6% (5/9) between November 16–30, 2019. This point did meet special cause, but did not result in a shift in the mean. The CCU team education meeting was held in late November, 2019, after which adherence increased to greater than 90%. However, toward the end of season 2, adherence decreased to 85.7% (12/14), though the decrease was less severe than what was seen in the prior year and did not meet special cause.

A second shift in the mean occurred at the beginning of season 3. This shift corresponded to the replacement of text message alerts to the CCU fellow physician with the EHR-based BPA and the inclusion of palivizumab education in the resident orientation. Mean palivizumab adherence increased to 97.9% (140/143) during this period, exceeding the goal of 95% adherence. When broken down by weeks, the first two weeks of season 3 again had somewhat lower adherence of 87.5%. However, for most of season 3, adherence was 100%. There was no decrease in adherence at the end of season 3, as had been seen in prior seasons.

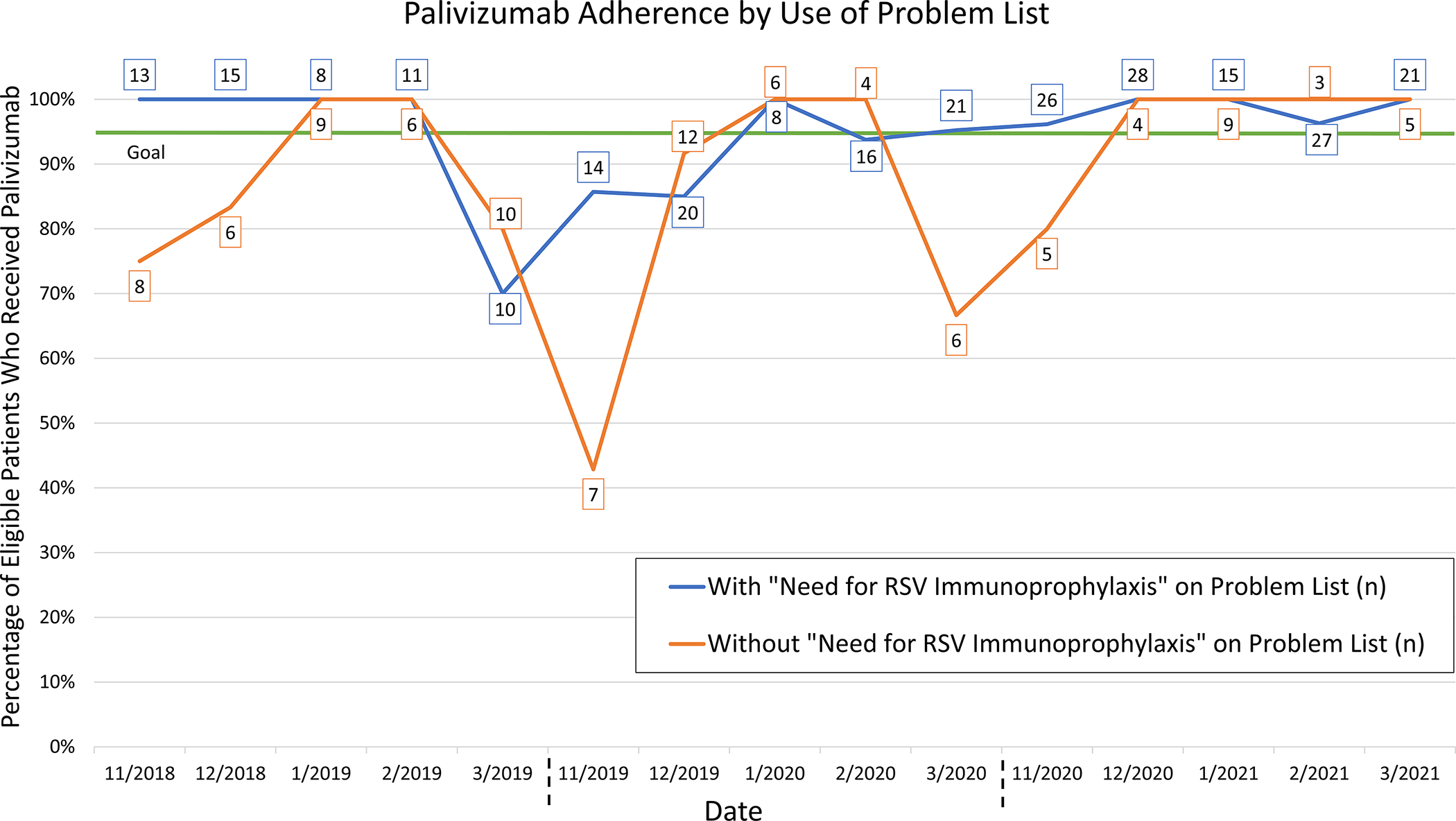

For the process metric, in the baseline RSV season between November 2017 and March 2018, no patients eligible for palivizumab prophylaxis had “Need for RSV immunoprophylaxis” documented on their problem list. With the initiation of text message alerts to the fellow physician in season 1, inclusion on the problem list increased to 58.3% (56/96) for eligible patients. This increased further in season 2 and season 3 to 69.3% (79/114) and 81.8% (117/143), respectively. Fig. 4 demonstrates palivizumab adherence over time by inclusion of “Need for RSV immunoprophylaxis” on the problem list. Overall, the palivizumab administration adherence was as high or higher for those with “Need for RSV immunoprophylaxis” on the problem list than for those without “Need for RSV immunoprophylaxis” on the problem list in most time periods. Over the three years of interventions, eligible patients with “Need for RSV immunoprophylaxis” on their problem list had a prophylaxis rate of 95.2%, compared with a prophylaxis rate of 86.9% among those who did not. Additionally, patients with “Need for RSV immunoprophylaxis” on the problem list had less of a decrease in adherence both at the beginning and end of the RSV seasons.

Fig. 4.

Run chart of monthly palivizumab guideline adherence by inclusion of “Need for RSV immunoprophylaxis” on the problem list. Total number of eligible patients in each group per month displayed in boxes.

Our balancing metric was the percentage of inappropriate doses. In the baseline RSV season between November 2017 and March 2018, 5.7% (5/87) of doses given were inappropriate. In season 1 and season 2, 4.4% (4/90) and 8.3% (9/109) of doses given were inappropriate, respectively. For the duration of season 3, no inappropriate doses were given.

DISCUSSION

This unique QI initiative demonstrated improved adherence with palivizumab administration guidelines for hospitalized infants with hemodynamically significant heart disease on a specialized inpatient cardiology service prior to discharge. We identified key barriers to palivizumab guideline adherence at our center, including some that have been previously identified in the outpatient setting, such as provider unfamiliarity with guidelines[8, 11, 19]. Over the course of three RSV seasons, we implemented multiple interventions that improved and sustained palivizumab administration, ultimately exceeding our SMART am of 95% adherence, while decreasing administration of inappropriate doses to zero.

The text message alerts and BPAs constituted high impact interventions. The primary process metric was the proportion of patients for which “Need for RSV immunoprophylaxis” was entered on the EHR problem list. The rate of palivizumab administration was higher in those patients who followed the text alerts and BPA and had “Need for RSV immunoprophylaxis” on their problem list. Although the initial text message alerts did not directly interface with the EHR, they prompted the use of the EHR problem list as the intermediate step to improve palivizumab adherence at discharge. Interestingly, there was a decrease in the percentage of patients that had their problem list updated both at the beginning and the end of each RSV season. Perhaps these are particularly vulnerable times because of a lack of awareness of palivizumab at the beginning of the season and a lack of perceived benefit of immunoprophylaxis at the end of the season. The patients with “Need for RSV immunoprophylaxis” on the problem list had higher adherence during these times, though small sample size limits statistical comparison between the groups.

We also considered the possibility of alert fatigue with the addition of the BPA to the EHR. The BPA was designed to be passive and easily dismissed in order to combat this possibility. The representatives of the front-line ordering clinicians who were part of the multidisciplinary QI team did not report concern for alert fatigue among their colleagues.

Additionally, although both the BPA and resident education interventions were implemented at the same time at the beginning of season 3, we believe the BPA was primarily responsible for the process mean change at that time to greater than 95%. The resident education targeted a small portion of the care team and only occurred once during the rotation. Additionally, education alone commonly has a low, unsustained impact on adherence. The BPA, on the other hand, targeted all providers on the care team that could view the problem list in the EHR, including attending physicians, fellow physicians, front-line clinicians, nurses, and pharmacists. It was also a consistent part of the workflow. A decrease in adherence was not seen at the end of the 2020/2021 season for either group, which may have been due to the EHR-based notification that did not rely on text message alerts and individual recall. EHR-based interventions for clinical decision-making support have frequently been shown to lead to improvements in the targeted processes of care, specifically regarding palivizumab adherence [10, 11, 20, 21], and in a wide variety of other settings. Our results are consistent with other published initiatives that take advantage of clinical decision support tools that are integrated into the EHR. There were also no inappropriate doses of palivizumab given in season 3, an indication that administration did not increase indiscriminately with the initiation of the BPA.

The CCU team education meeting at the beginning of each season was hypothesized to have a low impact on adherence. However, our data suggest that this education meeting may be important for palivizumab adherence at the beginning of the season. In season 2, palivizumab adherence in the first few weeks of the season was substantially lower than it had been during most of season 1. Once the education meeting occurred, the adherence increased. Additionally, season 2 had the highest percentage of inappropriate doses given, and most of the inappropriate doses of palivizumab (5/8 doses) were given prior to the CCU team education meeting. These observations support the value of educating the care team about this essential aspect of inpatient care for this vulnerable population. While this intervention occurred at only one timepoint during each season, the high adherence throughout season 3 suggested that, together with our other interventions, a yearly meeting was adequate.

The interventions in place at the end of the project represent sustainable modifications that were easily incorporated into the workflow and have likely enabled sustainability of the project. The yearly CCU team education meeting, inclusion of palivizumab on the sign-out template, identification of a pharmacy expert, and inclusion of palivizumab education in the existing resident orientation represented low effort and easily maintainable interventions. The text message alert was high effort, as it was a manual and labor-intensive intervention. The initial implementation of the BPA, which replaced the text message alert, was also high effort. However, it did not need further modification and was automatically incorporated into the EHR for all inpatients, and thus became the most reliable and sustainable intervention. The BPA has an additional advantage in that it will automatically flag in the EHR inpatient context for the first year of life so that “Need for RSV immunoprophylaxis” on the problem list may also serve as a reminder to the outpatient team to administer palivizumab on a monthly basis during the RSV season. Our QI team plans to continue these interventions to maintain excellent palivizumab adherence among cardiology patients at our institution.

We acknowledge limitations to this initiative. First, this initiative was undertaken in a specialized context, specifically a large-volume inpatient cardiology service in a tertiary care center, which may limit generalizability. In this context, the proportion of patients seen who are eligible for palivizumab is relatively high, so there were regular opportunities for reinforcement of eligibility criteria. Clinicians caring for fewer cardiac patients meeting eligibility criteria for palivizumab may require more intensive educational interventions to improve knowledge of eligibility criteria. Additionally, though we attempted to be inclusive, the BPA was developed using ICD-10 codes commonly seen on the cardiology inpatient service at our institution. A different list of ICD-10 codes may be more appropriate at other institutions based on the most common cardiac lesions seen. Finally, given the high number of patients at our center who qualify for palivizumab, dose administration was batched to reduce wasted supply and cost, which may not be possible at other centers.

Despite the relatively high number of palivizumab-eligible patients included in this initiative, the number of patients in each time period is small. This small number limits the ability to detect significant differences in adherence between patients with and without “Need for RSV immunoprophylaxis” on the problem list.

Additionally, though the results from our process metric of adherence with “Need for RSV immunoprophylaxis” on the problem list supports our conclusion that the text message alerts and BPA primarily drove the improved adherence, it was not possible to measure the contribution of each individual intervention. For example, we were unable to track the added contribution of the palivizumab line item in the sign-out template or the added contribution of the identified pharmacy expert. While these interventions were hypothesized to be low impact interventions, we are unable to completely separate their contributions from others implemented at the same time.

Finally, hemodynamically significant heart disease as defined by the AAP remains somewhat unclear in certain situations. The QI team used our institutional operational definition of hemodynamically significant heart disease to determine palivizumab eligibility.

CONCLUSION

This successful QI initiative demonstrates a significant, sustained improvement in palivizumab administration for RSV infection in eligible patients with cardiac disease prior to discharge from the hospital. With the integration of a sustainable EHR-based BPA into clinical care to improve inpatient adherence with palivizumab guidelines, and the addition of other low impact interventions, we met our SMART aim of greater than 95% adherence with palivizumab prophylaxis at hospital discharge over time. While this initiative was successful, the palivizumab dose administered at discharge from an inpatient admission represents a small portion of the recommended prophylaxis course of monthly palivizumab administration throughout the RSV season. This initiative could be spread by integrating the BPA in the outpatient setting, which would likely improve outpatient palivizumab adherence and decrease the morbidity of RSV in this vulnerable patient population with cardiac disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Kristin McNaughton, MHS, for editing assistance, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. No conflicts of interest to report.

Kyle Winser for statistical assistance, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. No conflicts of interest to report.

Sources of Funding:

Dr. Andrea L. Jones was supported by T32-HL007915.

Abbreviations:

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- BPA

Best Practice Alert

- CCU

Cardiac Care Unit

- CHOP

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

- EHR

Electronic health record

- QI

Quality improvement

- RSV

Respiratory syncytial virus

- SPC

Statistical process control

Footnotes

Financial and Non-financial Interests: The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics Approval:

This Quality Improvement Initiative was reviewed and determined to not meet the criteria for human subjects’ research by the CHOP Institutional Review Board.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shi T, et al. , Risk factors for RSV associated acute lower respiratory infection poor outcome and mortality in young children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect Dis, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall CB, et al. , The burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children. N Engl J Med, 2009. 360(6): p. 588–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Resch B and Michel-Behnke I, Respiratory syncytial virus infections in infants and children with congenital heart disease: update on the evidence of prevention with palivizumab. Curr Opin Cardiol, 2013. 28(2): p. 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simon A, et al. , Respiratory syncytial virus infection in 406 hospitalized premature infants: results from a prospective German multicentre database. Eur J Pediatr, 2007. 166(12): p. 1273–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wegzyn C, et al. , Safety and Effectiveness of Palivizumab in Children at High Risk of Serious Disease Due to Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection: A Systematic Review. Infect Dis Ther, 2014. 3(2): p. 133–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andabaka T, et al. , Monoclonal antibody for reducing the risk of respiratory syncytial virus infection in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2013(4): p. CD006602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious, D. and C. American Academy of Pediatrics Bronchiolitis Guidelines, Updated guidance for palivizumab prophylaxis among infants and young children at increased risk of hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection. Pediatrics, 2014. 134(2): p. 415–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frogel MP, et al. , A systematic review of compliance with palivizumab administration for RSV immunoprophylaxis. J Manag Care Pharm, 2010. 16(1): p. 46–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frogel M, et al. , Improved outcomes with home-based administration of palivizumab: results from the 2000–2004 Palivizumab Outcomes Registry. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2008. 27(10): p. 870–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rida NM, Tribble A, and Klein KC, Implementation of a Palivizumab Order Panel to Decrease Inappropriate Use. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther, 2019. 24(1): p. 58–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Utidjian LH, et al. , Clinical Decision Support and Palivizumab: A Means to Protect from Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Appl Clin Inform, 2015. 6(4): p. 769–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chow JW, et al. , Improving Palivizumab Compliance rough a Pharmacist-Managed RSV Prevention Clinic. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther, 2017. 22(5): p. 338–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weaver KL, et al. , Evaluation of Appropriateness and Cost Savings of Pharmacist-Driven Palivizumab Ordering. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther, 2020. 25(7): p. 636–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rostas SE and McPherson C, Pharmacist-driven respiratory syncytial virus prophylaxis stewardship service in a neonatal intensive care unit. Am J Health Syst Pharm, 2016. 73(24): p. 2089–2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zembles TN, et al. , Implementation of American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for palivizumab prophylaxis in a pediatric hospital. Am J Health Syst Pharm, 2016. 73(6): p. 405–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sel K, et al. , Palivizumab compliance in congenital heart disease patients: factors related to compliance and altered lower respiratory tract infection viruses after palivizumab prophylaxis. Cardiol Young, 2020. 30(6): p. 818–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohammed MHA, et al. , Palivizumab prophylaxis against respiratory syncytial virus infection in patients younger than 2 years of age with congenital heart disease. Ann Saudi Med, 2021. 41(1): p. 31–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson LS, The Shewhart Control Chart—Tests for Special Causes. J Qual Technol, 1984. 16(4): p. 237–239. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson KS, et al. , Compliance with RSV prophylaxis: Global physicians’ perspectives. Patient Prefer Adherence, 2009. 3: p. 195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mrosak J, et al. , The influence of integrating clinical practice guideline order bundles into a general admission order set on guideline adoption. JAMIA Open, 2021. 4(4): p. ooab087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwan JL, et al. , Computerised clinical decision support systems and absolute improvements in care: meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. BMJ, 2020. 370: p. m3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.