Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to investigate the efficacy of bevacizumab (Bev) in reducing peritumoral brain edema (PTBE) after stereotactic radiotherapy (SRT) for lung cancer brain metastases.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted on 44 patients with lung cancer brain metastases (70 lesions) who were admitted to our oncology and Gamma Knife center from January 2020 to May 2022. All patients received intracranial SRT and had PTBE. Based on treatment with Bev, patients were categorized as SRT + Bev and SRT groups. Follow‐up head magnetic resonance imaging was performed to calculate PTBE and tumor volume changes. The edema index (EI) was used to assess the severity of PTBE. Additionally, the extent of tumor reduction and intracranial progression‐free survival (PFS) were compared between the two groups.

Results

The SRT + Bev group showed a statistically significant difference in EI values before and after radiotherapy (p = 0.0115), with lower values observed after treatment, but there was no difference in the SRT group (p = 0.4008). There was a difference in the distribution of EI grades in the SRT + Bev group (p = 0.0186), with an increased proportion of patients at grades 1–2 after radiotherapy, while there was no difference in the SRT group (p > 0.9999). Both groups demonstrated a significant reduction in tumor volume after radiotherapy (p < 0.05), but there was no difference in tumor volume changes between the two groups (p = 0.4089). There was no difference in intracranial PFS between the two groups (p = 0.1541).

Conclusion

Bevacizumab significantly reduces the severity of PTBE after radiotherapy for lung cancer. However, its impact on tumor volume reduction and intracranial PFS does not reach statistical significance.

Keywords: bevacizumab, brain metastases, lung cancer, peritumoral brain edema, radiotherapy

Our findings show that bevacizumab significantly reduces peritumoral brain edema after radiotherapy for lung cancer brain metastases, but it does not show significant improvement in tumor reduction or intracranial progression‐free survival.

INTRODUCTION

Peritumoral brain edema (PTBE) is a common complication of intracranial tumors, such as meningiomas, metastases, and gliomas. The etiology involves a convergence of factors, including vascular origin leakage, the influx of fluid and serum proteins into the tissue interstitium, cellular damages, and imbalance in ion concentrations. 1 Radiation therapy can also cause PTBE, primarily attributable to vascular leakage. The space‐occupying effect of PTBE can exacerbate neurological symptoms and lead to increased intracranial pressure, which can cause headaches, seizures, focal neurological deficits, and encephalopathy. Furthermore, uncontrolled brain edema can lead to fatal brain herniation due to the confinement of brain tissue within a rigid cranial bone.

The current treatment options for PTBE are limited. The symptomatic management of PTBE mainly centers on the systemic administration of corticosteroids, which can suppress inflammation, reduce blood–brain barrier (BBB) damage, decrease vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression, improve peritumoral microcirculation, and stabilize lysosomal membranes. Additional interventions may also be used to alleviate intracranial pressure, such as the administration of hypertonic saline and mannitol. Since VEGF plays a crucial role in the development of PTBE, anti‐VEGF monoclonal antibodies have the potential to alleviate edema, promote vascular normalization, and preserve BBB integrity. 2 In 2007, Gonzalez et al. 3 were pioneers in reporting the use of bevacizumab to treat radiation‐induced brain necrosis. In recent years, several studies have confirmed the efficacy of bevacizumab in the treatment of radiation‐induced brain necrosis. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 A comprehensive meta‐analysis involving 12 studies showed that bevacizumab is effective in treating radiation‐induced brain edema, leading to improved clinical symptoms and superior outcomes in comparison to the corticosteroid treatment. 12 However, the majority of these studies were conducted with limited sample sizes, 13 , 14 , 15 leaving several questions unanswered. For example, the ideal duration and optimal dosage of bevacizumab remain uncertain. More research is needed to answer these questions and establish the role of bevacizumab in the treatment of PTBE.

The primary objective of this study was to conduct the first head‐to‐head comparative analysis, assessing the therapeutic efficacy of combining bevacizumab with radiotherapy for the treatment of PTBE in patients with lung cancer brain metastases. This analysis intended to provide clinical evidence to support the utilization of antiangiogenic agents to treat PTBE induced by stereotactic radiotherapy (SRT).

METHODS

Study subjects and treatment methods

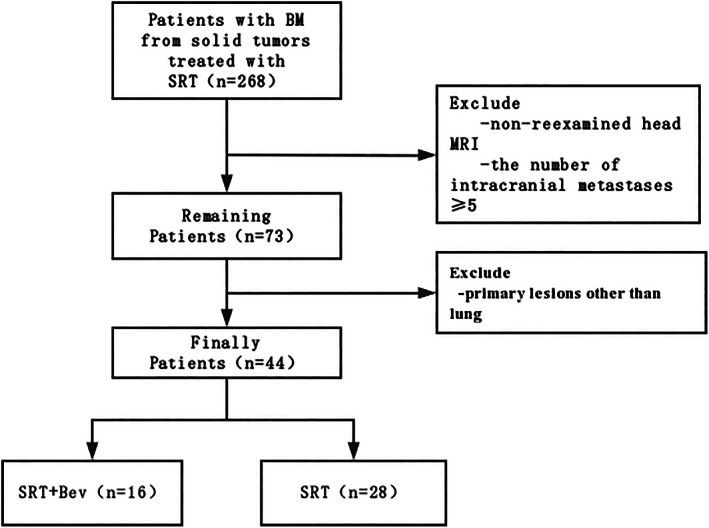

This was a retrospective analysis of pertinent data related to patients with brain metastasis from lung cancer who underwent SRT treatment at the Department of Oncology and Gamma Knife Center at Beijing Tiantan Hospital from January 2020 to May 2022. The exclusion criteria included the absence of undergoing a head‐enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) re‐examination within 1–3 months following radiotherapy, the presence of ≥5 intracranial metastases, and having a primary tumor situated outside the lungs. A total of 44 patients with 70 lesions were included in this study. The SRT + Bev group included 16 patients with 25 lesions, and the SRT group included 28 patients with 45 lesions (Figure 1). Out of the 16 patients, some were prescribed bevacizumab due to the requirement for systemic treatment, while others needed bevacizumab due to the presence of PTBE symptoms. This decision was not based on the initial EI value. Among these 16 cases, 10 individuals initially exhibited PTBE symptoms, which included symptoms such as dizziness, headaches, nausea, vomiting, blurred vision, and hearing difficulties. Demographic information such as age, sex, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, and other essential information were recorded. Clinical pathological data, imaging materials, and treatment regimens (systemic anticancer protocols, number of SRT treatments, use of mannitol and dexamethasone, and prior history of SRT or whole brain radiation therapy [WBRT]) were also documented. In two cases, mannitol was not used. One patient had kidney issues that precluded mannitol use, and another patient had an allergy to mannitol. Also, a patient with uncontrolled high blood pressure and diabetes did not receive dexamethasone treatment. General data comparison revealed no statistically significant differences between the two groups (p > 0.05), indicating that the two groups were comparable (Table 1). This study was approved by the hospital's ethics committee, and all patients voluntarily signed informed consent forms.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart.

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics.

| Characteristics n (%) | SRT + Bev (n = 16) | SRT (n = 28) | p‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | 0.44 | ||

| <65 | 8 (50.0) | 11 (39.3) | |

| ≥65 | 8 (50.0) | 17 (60.7) | |

| Gender | 0.543 | ||

| Female | 8 (50.0) | 18 (64.3) | |

| Male | 8 (50.0) | 10 (35.7) | |

| ECOG PS | 0.836 | ||

| 0–1 | 11 (68.8) | 17 (60.7) | |

| ≥2 | 5 (31.2) | 11 (39.3) | |

| SRT number | 1 | ||

| 1–2 | 2 (12.5) | 3 (10.7) | |

| 3–4 | 14 (87.5) | 25 (89.3) | |

| Histopathology | 1 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 12 (75.0) | 21 (75.0) | |

| Nonadenocarcinoma | 4 (25.0) | 7 (25.0) | |

| Systemic treatment | 0.223 | ||

| TKI | 7 (43.8) | 6 (21.4) | |

| Others | 9 (56.2) | 22 (78.6) | |

| Mannitol | 0.245 | ||

| Yes | 14 (87.5) | 28 (100.0) | |

| No | 2 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Dexamethasone | 0.774 | ||

| Yes | 15 (93.8) | 28 (100.0) | |

| No | 1 (6.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Previous SRT | 1 | ||

| Yes | 2 (12.5) | 4 (14.3) | |

| No | 14 (87.5) | 24 (85.7) | |

| Previous WBRT | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1 (6.2) | 1 (3.6) | |

| No | 15 (93.8) | 27 (96.4) |

Abbreviations: Bev, bevacizumab; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; SRT, stereotactic radiotherapy; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; WBRT, whole brain radiotherapy.

All patients received SRT treatment, with a peritarget dose ranging from 10 to 24 Gy. The median target dose was approximately 13 Gy (Table S1). Patients in the SRT + Bev group were given bevacizumab treatment within 1 to 7 days after radiotherapy. Within this time frame, there were two patients on the first day, five on the second day, four on the third day, two on the fourth day, one on the sixth day, and two on the seventh day. The bevacizumab dosage was calculated based on the patients' bodyweight, ranging from 100 to 400 mg/kg. Bevacizumab was dissolved in 100 mL of normal saline and administered through intravenous infusion over a 90‐min period.

Treatment response evaluation

Each patient underwent head MRI both before and within 1–3 months after the SRT treatment. The MRI images were processed using the Gamma‐plan workstation. The volumes of edema plus tumor (T2WI) and tumor (T1 + C) were outlined and delineated. Following the method described by Bitzer et al., 16 the edema index (EI) was calculated using the formula: EI = (edema volume + tumor volume)/tumor volume. The EI values were used to classify the degree of edema into four radiographic grades: Grade 1 (EI = 1, indicating no edema), grade 2 (EI = 1–1.5, representing mild edema), grade 3 (EI = 1.5–3, indicating moderate edema), and grade 4 (EI >3, indicating severe edema).

The changes in the tumor volume before and after radiotherapy were compared between the SRT group and the SRT + Bev group, and differences between the groups were assessed.

Tumor response evaluation was performed in accordance with the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.1 criteria, and the intracranial progression‐free survival (PFS) was monitored throughout the follow‐up period. Intracranial PFS was defined as the duration from the initiation of the SRT treatment to the occurrence of disease progression or the last follow‐up visit for the intracranial lesions that underwent the SRT treatment. Disease progression refers to the occurrence of disease advancement in brain metastases that have undergone SRT treatment, rather than the overall brain control. This assessment excluded new intracranial lesions.

Statistical analysis

The Wilcoxon rank‐sum test was used to assess the association between changes in tumor volume and EI values in relation to bevacizumab administration. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the changes in tumor volume between the SRT and SRT + bevacizumab groups. Categorical variables were compared using either the chi‐square test or Fisher's exact test. The Kaplan–Meier method and the log‐rank test were used to compare the survival outcomes between the treatment groups. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism and R (version 3.4.4). A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was applied to determine statistical significance.

RESULTS

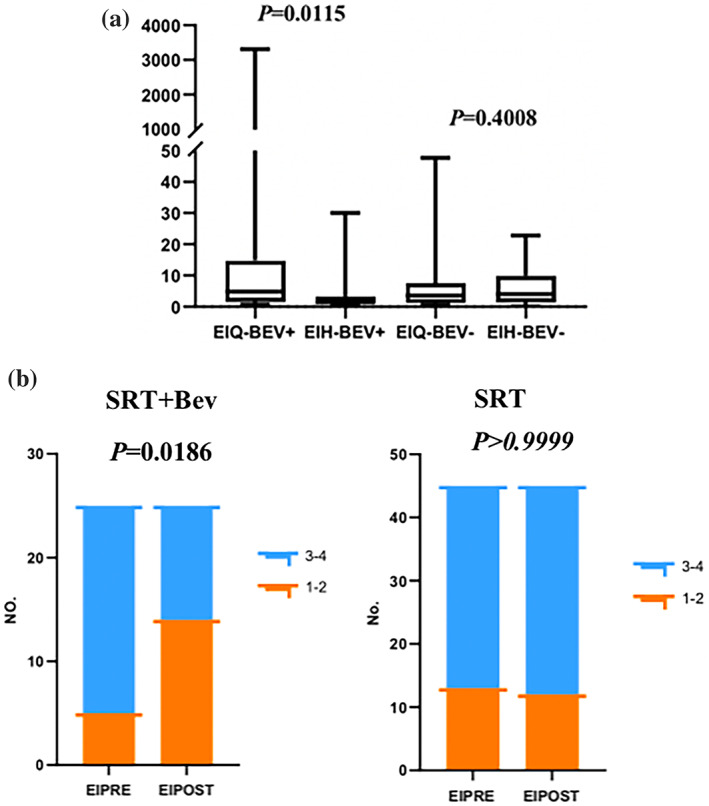

The median EI value in the SRT + Bev group prior to radiotherapy was 4.80, and following radiotherapy, it decreased to 1.48, with corresponding means of 181.28 and 3.78. The Wilcoxon signed‐rank test showed a statistically significant difference in the EI values before and after radiotherapy (p = 0.0115), with lower values observed after the treatment. In the SRT group, the median EI value was 3.56 before radiotherapy and 4.00 after radiotherapy, with respective means of 7.39 and 5.89. The Wilcoxon signed‐rank test did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference in the EI values before and after radiotherapy (p = 0.4008). These findings suggest that SRT + Bev can reduce the EI values and mitigate the risk of peritumoral edema (Figure 2a).

FIGURE 2.

(a) The values of EI (edema index) before and after radiotherapy in the SRT + Bev group and the SRT group. (b) The grades of EI before and after radiotherapy in the SRT + Bev group and the SRT group. EIH, the value of edema index EI after SRT; EIPOST, grading of edema index EI after SRT; EIQ, the value of edema index EI before SRT; EIPRE, grading of edema index (EI) before SRT; No., number of patients.

This study included a cohort of 44 patients with 70 lesions, among which 25 lesions were in the SRT + Bev group and 45 were in the SRT group. In the SRT group, 28.89% (13 patients) of patients had edema grade 1–2, and 71.11% (32 patients) of patients had edema grade 3–4 before radiotherapy. After radiotherapy, the percentage of patients with edema grade 1–2 was 26.67% (12 patients), and 73.33% (33 patients) of patients had edema grade 3–4. Due to the limited sample size in the SRT group, Fisher's exact test was used to compare the difference in edema grade before and after radiotherapy. The test did not show a statistically significant difference (p > 0.9999). In the SRT + Bev group, 20.0% (5 patients) of patients had edema grade 1–2, and 80.0% (20 patients) of patients had edema grade 3–4 before radiotherapy. After radiotherapy, the percentage of patients with edema grade 1–2 increased to 56.0% (14 patients), while that of those with edema grade 3–4 decreased to 44.0% (11 patients). Fisher's exact test indicated a significant difference in the edema grade before and after radiotherapy in the SRT + Bev group (p = 0.0186), with an increase in patients with grade 1–2 edema and a decrease in patients with grade 3–4 edema after treatment. This suggests that SRT + Bev can reduce the severity of edema and mitigate the risk associated with peritumor edema (Figure 2b).

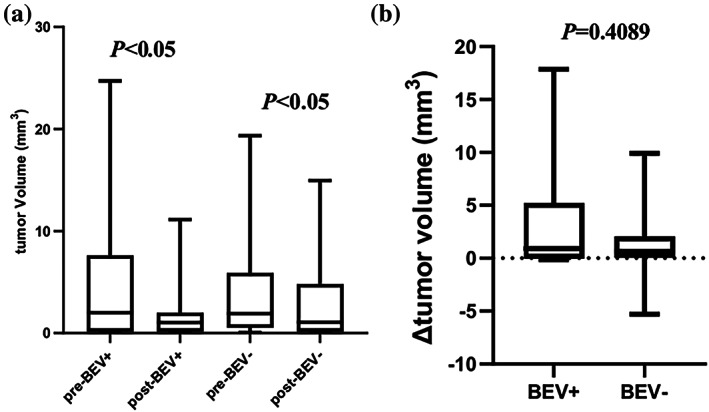

Before radiotherapy, the median tumor volume in the SRT group was 1.91 mm3, with a mean of 4.11 mm3. After radiotherapy, the median tumor volume was 0.893 mm3, with a mean of 2.79 mm3. This reduction associated with radiotherapy was statistically significant, as confirmed by the Wilcoxon signed‐rank test (p < 0.05). In the SRT + Bev group, the median tumor volume was 2 mm3 before radiotherapy, with a mean of 5.03 mm3. Following radiotherapy, the median tumor volume dropped to 1.054 mm3, with a mean of 1.87 mm3. Similar to the SRT group, the Wilcoxon signed‐rank test also demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in tumor volume after radiotherapy in the SRT + Bev group (p < 0.05). These findings collectively suggest a substantial reduction in tumor volume in both groups after radiotherapy, as depicted in Figure 3a.

FIGURE 3.

(a) Changes in tumor volume before and after radiotherapy in SRT + Bev group and SRT group. (b) Difference in tumor volume between SRT + Bev group and SRT group. Δ tumor volume = pretreatment – post‐treatment tumor volume.

The Mann–Whitney U test was used to assess the differences in tumor volume before and after radiotherapy between the two groups. The histogram exhibited a similar distribution of tumor volume changes in both cohorts. The calculated median difference in tumor volume for the SRT + Bev group was 0.9100 mm3, while for the SRT group, it was 0.6600 mm3. The Mann–Whitney U test indicated no statistically significant difference in the changes of tumor volume between the two groups (U = 494.5, p = 0.4089) (Figure 3b).

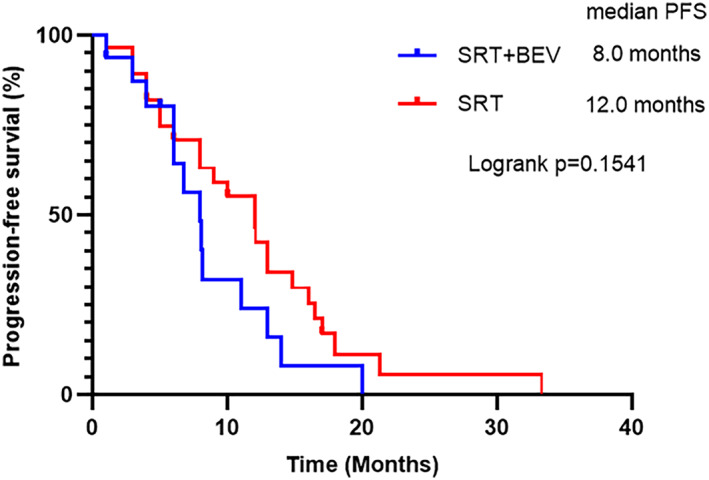

The median intracranial PFS for the SRT + Bev group was 8.0 months, compared to 12.0 months for the SRT group. Nevertheless, statistical analysis revealed no significant difference in the intracranial PFS between the two groups (p = 0.1541) (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Intracranial mPFS in SRT + Bev group and SRT group. mPFS, median progression‐free survival.

DISCUSSION

Radiation‐induced edema is the most common complication following radiotherapy for central nervous system tumor. It primarily originates from vascular damages caused by radiation therapy. The damage leads to increased expression of VEGF. Furthermore, the radiation induced tissue damage leads to hypoxia, which activates hypoxia‐inducible factor (HIF)‐1α. This transcription factor, in turn, triggers reactive astrocytes to secrete more VEGF. The elevated level of VEGF promotes the formation of abnormal and fragile new blood vessels that are highly permeable, allowing fluid to leak into the surrounding tissues and facilitating the development of radiation‐induced brain edema. 17

Antiangiogenic therapy can inhibit the VEGF signaling pathway, preventing the formation of abnormal neovascular structures and restoring the integrity of the blood–brain barrier (BBB). This, in turn, can help control tumor growth and minimize the occurrence of surrounding edema. Bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds to VEGF and blocks its interaction with its receptors present on the surface of endothelial cells, thereby exerting a role in vascular repair and regulation of vascular permeability 18 , 19 and consequently alleviating brain edema. Other newer small‐molecule multitargeted antiangiogenic drugs can also effectively inhibit VEGF receptors. Studies have demonstrated that anlotinib significantly improves brain edema and related symptoms caused by brain metastasis or SRT. Bevacizumab is often favored over this class of drugs due to its longer‐lasting effectiveness owing to its extended half‐life.

This retrospective study conducted an analysis on a cohort of 44 patients who developed brain metastases originating from lung cancer. Those patients underwent the SRT treatment for a total of 70 brain lesions. One group received a combination therapy involving bevacizumab after undergoing the SRT treatment, while the other group received the SRT without the addition of bevacizumab. Both groups of patients were administered a dehydration treatment with mannitol and dexamethasone. The group that received the combination therapy with bevacizumab exhibited a significant reduction in peritumoral edema, as indicated by both the EI values and the edema grading. On the other hand, the group that did not receive bevacizumab exhibited no significant changes in peritumoral edema. In the SRT + Bev group, an increased number of patients exhibited mild to moderate edema (grade 1–2) after radiotherapy. However, this trend was not observed within the SRT group. This finding further suggests that the combined therapy with bevacizumab can reduce the severity of the peritumoral edema. This reduction helps mitigate the series of adverse effects caused by peritumoral edema, offering temporary relief to patients' clinical symptoms. However, it is important to mention that this study only compared and analyzed the regression of edema within 1–3 months after the SRT treatment. There was no extensive long‐term follow‐up or comprehensive analysis conducted regarding intracranial edema beyond this initial time frame. It is yet to be determined whether a singular administration of bevacizumab can have prolonged effects in reducing edema. Nevertheless, the dehydrating impact of bevacizumab has the potential to reduce the administration of hormone intervention, thereby mitigating the associated side effects. Additionally, this approach could circumvent the potential influence of hormone therapy on the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs).

Due to the sensitivity of brain metastases to radiation therapy, both groups showed significant reduction in tumor volume following radiotherapy, regardless of bevacizumab administration. However, no statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups. This implied that although bevacizumab monotherapy has a significant therapeutic effect on PTBE, its direct impact on the metastatic tumors themselves is less pronounced. Such findings may appear contradictory to previous studies, as bevacizumab's blockade of the VEGF signaling pathway indicated normalization of tumor vasculature. 20 Ideally, this normalization effect should synergize with chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Our results showed no significant difference in progression‐free survival between the two groups. Therefore, the significance of bevacizumab treatment for radiation‐induced brain necrosis in this study seems to be more focused on symptom relief and enhancing the quality of life, rather than extending survival. The reason for these two unfavorable outcomes could potentially be attributed to the retrospective nature of this study. One plausible explanation was the diverse systemic antitumor treatment regimens that patients received, including small‐molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), which could penetrate the BBB effectively. This penetration could potentially lead to a synergistic reduction of tumor when combined with SRT to treat intracranial metastases. Although the systemic antitumor treatment regimens were consistent between the SRT and SRT + Bev groups at baseline, variations in these regimens could potentially influence the timing of tumor recurrence.

It is worth noting that this study had several limitations. Our study focused on patients with brain metastases from lung cancer, mostly adenocarcinoma. There were limited numbers of patients with other lung cancer subtypes, such as squamous cell carcinoma, small cell lung cancer, and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Different pathological types of lung cancer may exhibit varying effects on peritumoral brain edema after radiation therapy. Clinical observations indicate that brain edema associated with adenocarcinoma may manifest more pronounced severity. The increased risk of bleeding in brain metastases from squamous cell carcinoma is a serious concern that must be considered when using antiangiogenic drugs, such as bevacizumab. Currently, there is no clear consensus on the optimal timing, dosing frequency, or dosage of bevacizumab application in this patient population. Previous studies used varying doses of bevacizumab, ranging from 2.5 to 10 mg/kg 21 , 22 , 23 ; however, a standardized recommendation is yet to be established. A study analyzed 30 case reports detailing bevacizumab treatment for radiation‐induced brain necrosis since 2007. They found that a minimum dose of 7.5 mg/kg, administered every 3 weeks over a 12‐week period, effectively prevented further progression of radiation necrosis and relieved associated symptoms. 24 However, in the context of clinical practice, practical considerations including cost often result in patients receiving bevacizumab treatment at lower doses (e.g., 5 mg/kg). Moreover, the usage of bevacizumab was commonly discontinued once brain edema relief was achieved. Given the retrospective nature of this study, the dosages and timing of bevacizumab administration exhibited variability, with each dosage category having a limited sample size, which made it challenging to conduct effective statistical analysis. Hence, a more extensive exploration of the dosing regimen of bevacizumab is warranted, necessitating larger sample size and prospective randomized controlled, multicenter studies.

In summary, the utilization of bevacizumab can significantly reduce PTBE in patients with lung cancer brain metastases after radiation therapy. However, its impact on reducing intracranial tumor size and improving patients' PFS is not statistically significant.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, Yi‐Chun Hua; methodology, Yi‐Chun Hua; software, Yi‐Chun Hua; validation, Yu‐Bin Li, De‐Zhi Gao, Xiao‐Sheng Ding; formal analysis, De‐Zhi Gao; investigation, Yu‐Bin Li; resources, De‐Zhi Gao, Kuan‐Yu Wang; data curation, Kuan‐Yu Wang; writing—original draft preparation, Yi‐Chun Hua; writing—review and editing, Yi‐Chun Hua; visualization, Yi‐Chun Hua; supervision, Wei‐Ran Xu; project administration, Xiao‐Sheng Ding; funding acquisition, Xiao‐Yan Li, Shi‐Bin Sun, Wei‐Wei Shi. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Supplementary Table S1. Peritarget dose for each SRT‐treated lesion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81974361); Beijing Municipal Education Commission‐Beijing Natural Science Foundation Union Program (KZ2020100250460). We thank all the members of department of medical oncology in our hospital that participated in this research. We also thank Xinying for his advice on statistical analysis.

Hua Y‐C, Gao D‐Z, Wang K‐Y, Ding X‐S, Xu W‐R, Li Y‐B, et al. Bevacizumab reduces peritumoral brain edema in lung cancer brain metastases after radiotherapy. Thorac Cancer. 2023;14(31):3133–3139. 10.1111/1759-7714.15106

Yu‐Bin Li, Wei‐Wei Shi, and Shi‐Bin Sun contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Wei‐Wei Shi, Email: shiweiwei301@sina.com.

Shi‐Bin Sun, Email: ssbwyl@vip.sina.com.

Xiao‐Yan Li, Email: lixiaoyan@bjtth.org.

REFERENCES

- 1. Michinaga S, Koyama Y. Pathogenesis of brain edema and investigation into anti‐edema drugs. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(5):9949–9975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Miyatake S, Nonoguchi N, Furuse M, Yoritsune E, Miyata T, Kawabata S, et al. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of radiation necrosis in the brain. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2015;55(1):50–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gonzalez J, Kumar AJ, Conrad CA, Levin VA. Effect of bevacizumab on radiation necrosis of the brain. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67(2):323–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carl CO, Henze M. Reduced radiation‐induced brain necrosis in nasopharyngeal cancer patients with bevacizumab monotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol. 2019;195(3):277–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tijtgat J, Calliauw E, Dirven I, Vounckx M, Kamel R, Vanbinst AM, et al. Low‐dose bevacizumab for the treatment of focal radiation necrosis of the brain (fRNB): a single‐center case series. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(9):2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dahl NA, Liu AK, Foreman NK, Widener M, Fenton LZ, Macy ME. Bevacizumab in the treatment of radiation injury for children with central nervous system tumors. Childs Nerv Syst. 2019;35(11):2043–2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Panagiotou E, Charpidou A, Fyta E, Nikolaidou V, Stournara L, Syrigos A, et al. High‐dose bevacizumab for radiation‐induced brain necrosis: a case report.CNS. Oncologia. 2023;4:CNS98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhuang H, Zhuang H, Shi S, Wang Y. Ultra‐low‐dose bevacizumab for cerebral radiation necrosis: a prospective phase II clinical study. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:8447–8453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xu Y, Rong X, Hu W, Huang X, Li Y, Zheng D, et al. Bevacizumab monotherapy reduces radiation‐induced brain necrosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;101(5):1087–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dashti SR, Kadner RJ, Folley BS, Sheehan JP, Han DY, Kryscio RJ, et al. Single low‐dose targeted bevacizumab infusion in adult patients with steroid‐refractory radiation necrosis of the brain: a phase II open‐label prospective clinical trial. J Neurosurg. 2022;137(6):1676–1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li H, Rong X, Hu W, Yang Y, Lei M, Wen W, et al. Bevacizumab combined with corticosteroids does not improve the clinical outcome of nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients with radiation‐induced brain necrosis. Front Oncol. 2021;11:746941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Delishaj D, Ursino S, Pasqualetti F, Cristaudo A, Cosottini M, Fabrini MG, et al. Bevacizumab for the treatment of radiation‐induced cerebral necrosis: a systematic review of the literature. J Clin Med Res. 2017;9(4):273–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Climans SA, Ramos RC, Jablonska PA, Shultz DB, Mason WP. Bevacizumab for Cerebral Radionecrosis: A Single‐Center Experience. Can J Neurol Sci. 2023;50(4):573–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li L, Feng M, Xu P, Wu YL, Yin J, Huang Y, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery with whole brain radiotherapy combined with bevacizumab in the treatment of brain metastases from NSCLC. Int J Neurosci. 2023;133(3):334–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Voss M, Wenger KJ, Fokas E, Forster MT, Steinbach JP, Ronellenfitsch MW. Single‐shot bevacizumab for cerebral radiation injury. BMC Neurol. 2021;21(1):77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bitzer M, Opitz H, Popp J, Morgalla M, Gruber A, Heiss E, et al. Angiogenesis and brain oedema in intracranial meningiomas: influence of vascular endothelial growth factor. Acta Neurochir. 1998;140(4):333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nonoguchi N, Miyatake S, Fukumoto M, Furuse M, Hiramatsu R, Kawabata S, et al. The distribution of vascular endothelial growth factor‐producing cells in clinical radiation necrosis of the brain: pathological consideration of their potential roles. J Neurooncol. 2011;105(2):423–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ali FS, Arevalo O, Zorofchian S, Patrizz A, Riascos R, Tandon N, et al. Cerebral radiation necrosis: incidence, pathogenesis, diagnostic challenges, and future opportunities. Curr Oncol Rep. 2019;21(8):66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jiang X, Engelbach JA, Yuan L, Cates J, Gao F, Drzymala RE, et al. Anti‐VEGF antibodies mitigate the development of radiation necrosis in mouse brain. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(10):2695–2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hong S, Tan M, Wang S, Luo S, Chen Y, Zhang L. Efficacy and safety of angiogenesis inhibitors in advanced non‐small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2015;141(5):909–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sadraei NH, Dahiya S, Chao ST, Murphy ES, Osei‐Boateng K, Xie H, et al. Treatment of cerebral radiation necrosis with bevacizumab: the Cleveland clinic experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 2015;38(3):304–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dashti SR, Spalding A, Kadner RJ, Yao T, Kumar A, Sun DA, et al. Targeted intraarterial anti‐VEGF therapy for medically refractory radiation necrosis in the brain. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015;15(1):20–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sanborn MR, Danish SF, Rosenfeld MR, O'Rourke D, Lee JY. Treatment of steroid refractory, gamma knife related radiation necrosis with bevacizumab: case report and review of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2011;113(9):798–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Matuschek C, Bölke E, Nawatny J, Hoffmann TK, Peiper M, Orth K, et al. Bevacizumab as a treatment option for radiation‐induced cerebral necrosis. Strahlenther Onkol. 2011;187(2):135–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1. Peritarget dose for each SRT‐treated lesion.