Abstract

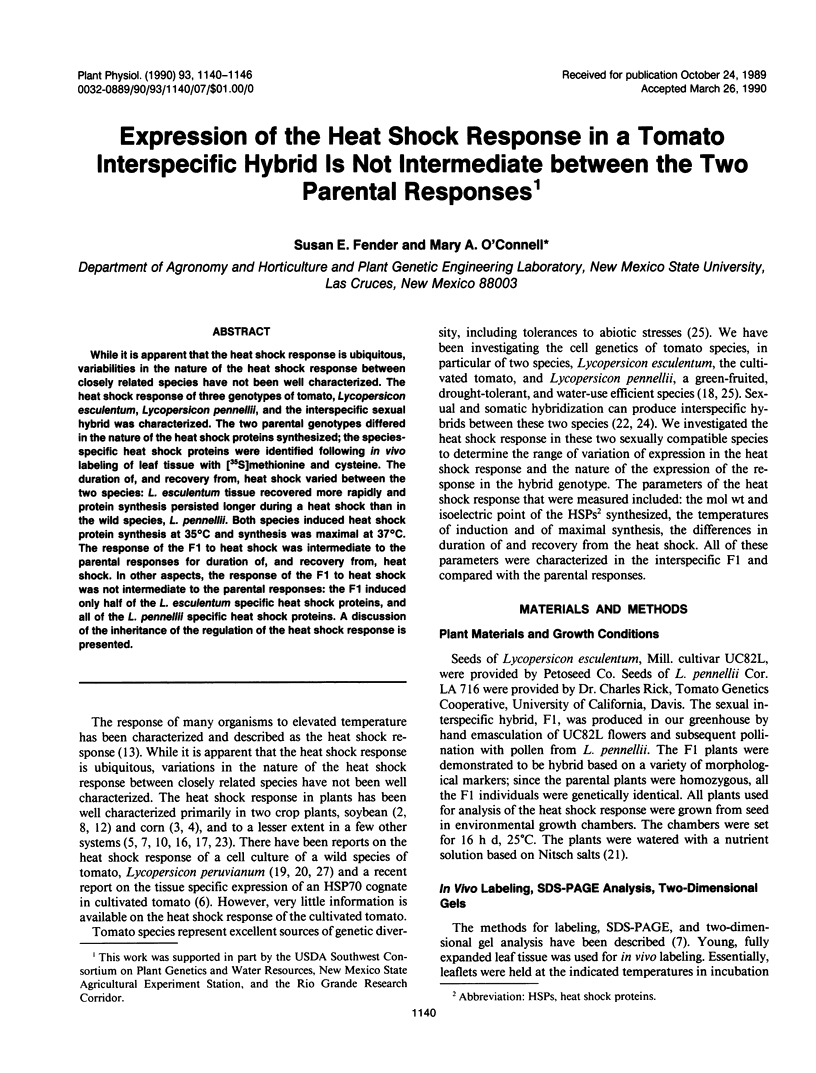

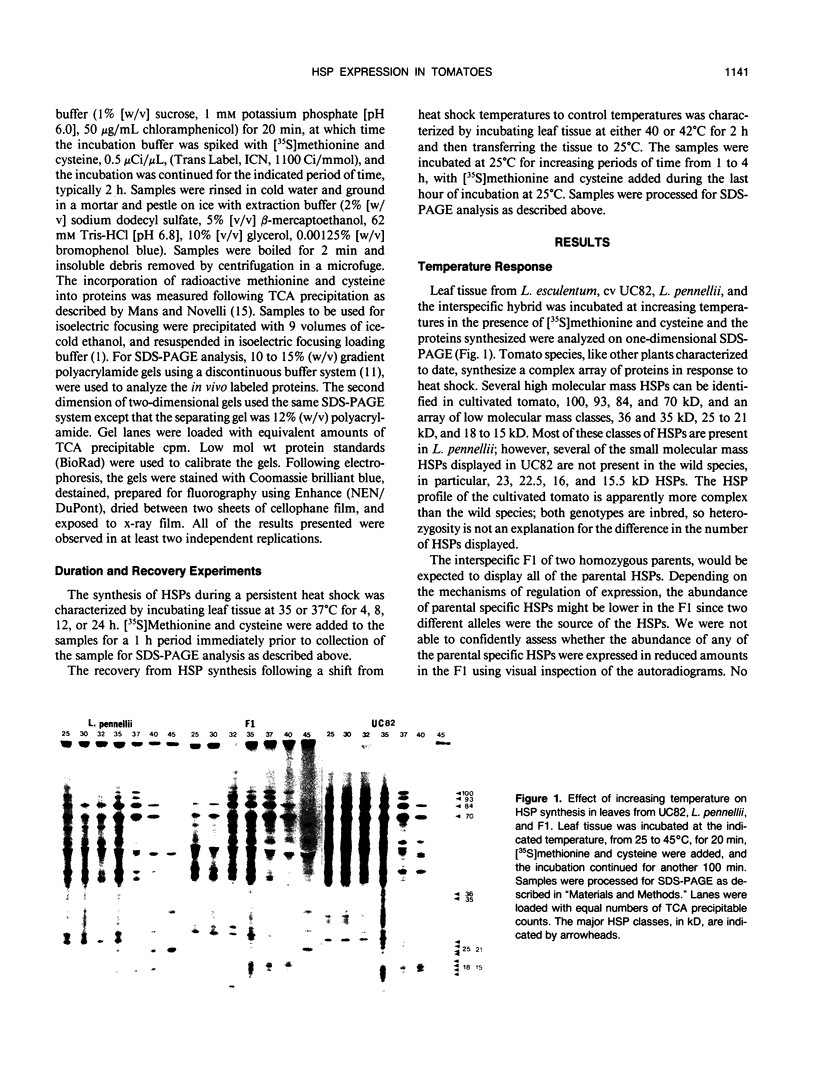

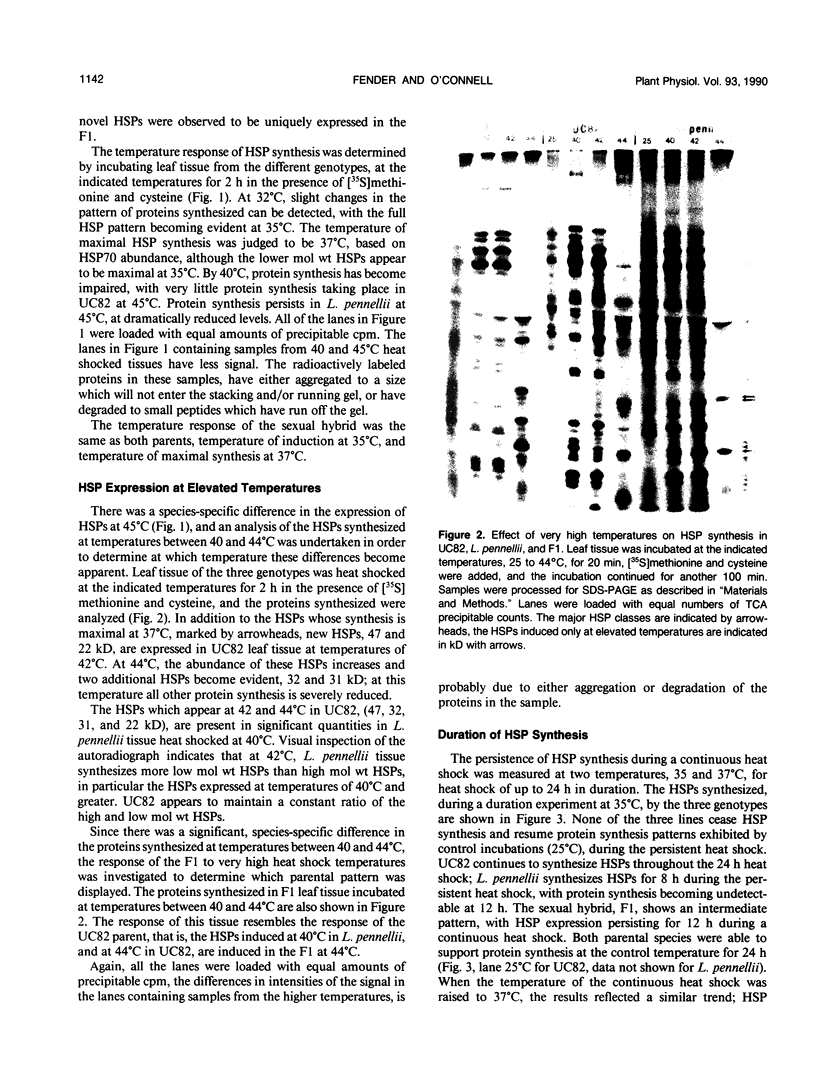

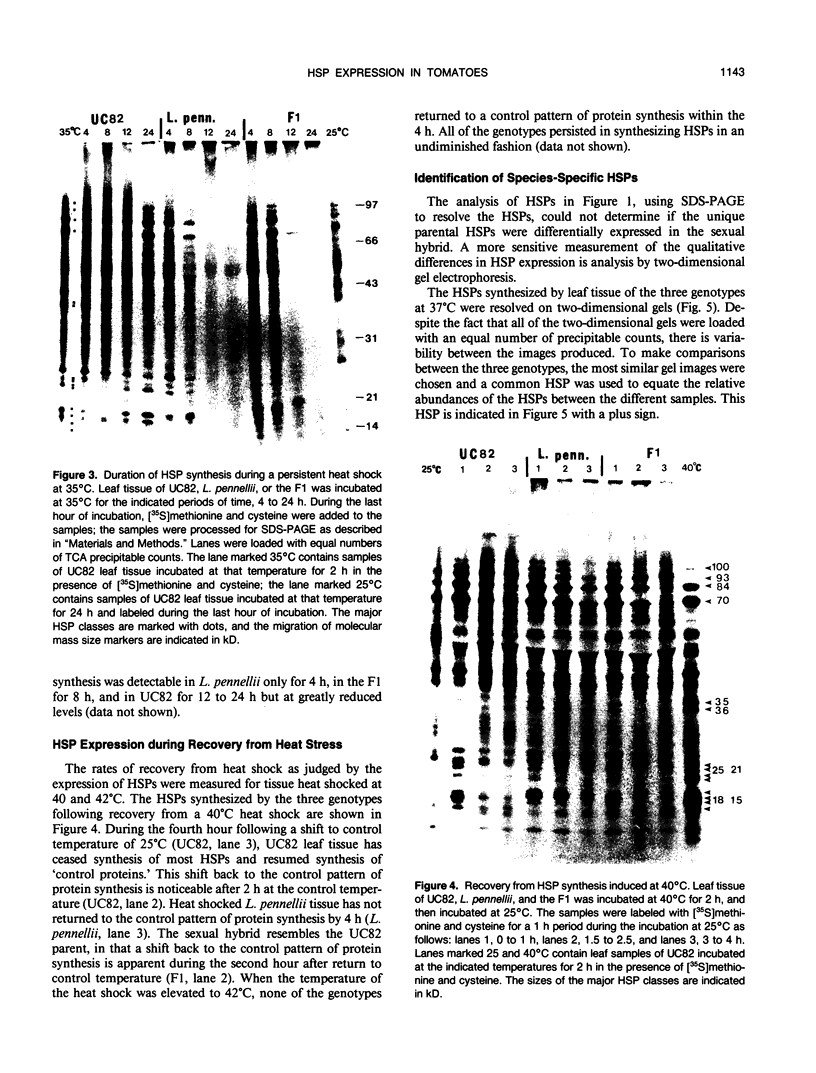

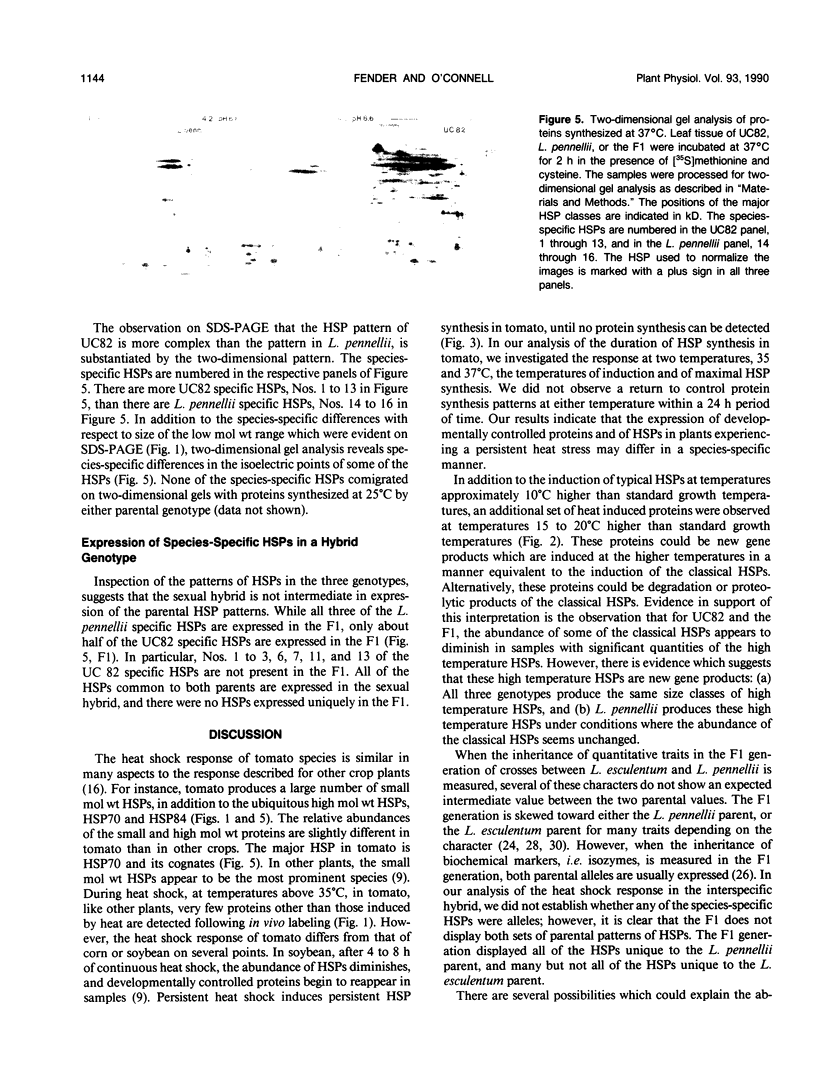

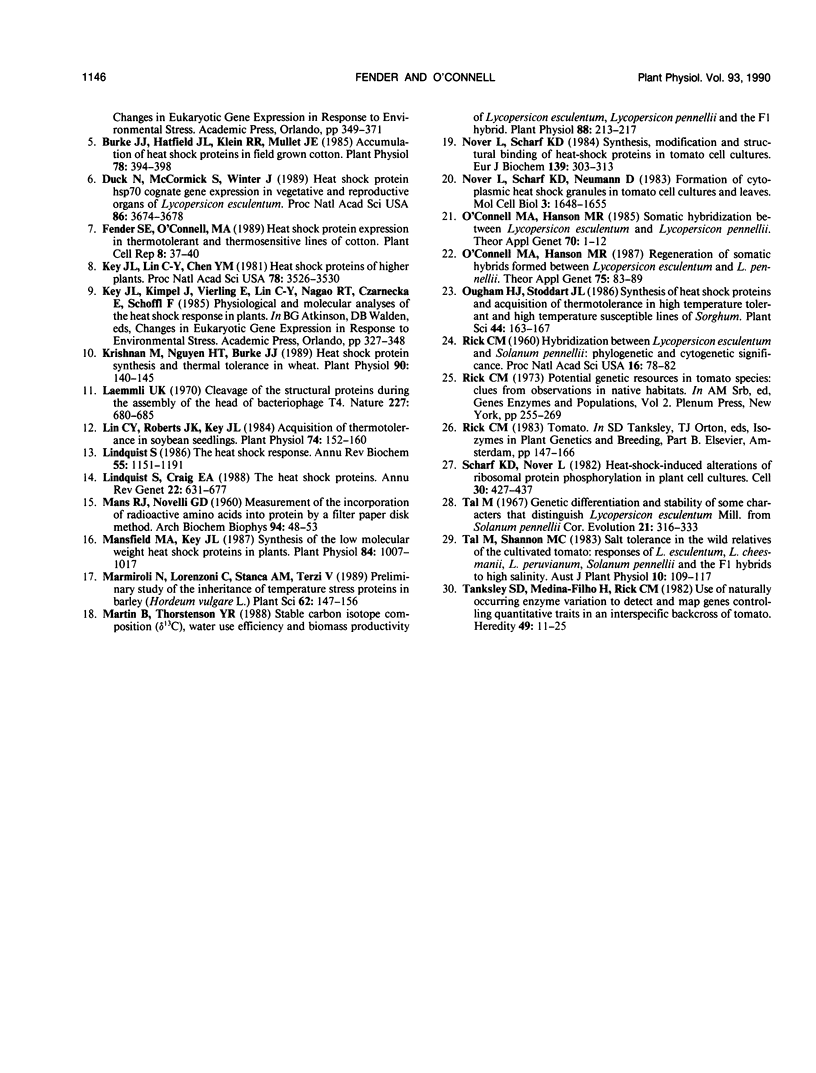

While it is apparent that the heat shock response is ubiquitous, variabilities in the nature of the heat shock response between closely related species have not been well characterized. The heat shock response of three genotypes of tomato, Lycopersicon esculentum, Lycopersicon pennellii, and the interspecific sexual hybrid was characterized. The two parental genotypes differed in the nature of the heat shock proteins synthesized; the speciesspecific heat shock proteins were identified following in vivo labeling of leaf tissue with [35S]methionine and cysteine. The duration of, and recovery from, heat shock varied between the two species: L. esculentum tissue recovered more rapidly and protein synthesis persisted longer during a heat shock than in the wild species, L. pennellii. Both species induced heat shock protein synthesis at 35°C and synthesis was maximal at 37°C. The response of the F1 to heat shock was intermediate to the parental responses for duration of, and recovery from, heat shock. In other aspects, the response of the F1 to heat shock was not intermediate to the parental responses: the F1 induced only half of the L. esculentum specific heat shock proteins, and all of the L. pennellii specific heat shock proteins. A discussion of the inheritance of the regulation of the heat shock response is presented.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baszczynski C. L., Walden D. B., Atkinson B. G. Regulation of gene expression in corn (Zea Mays L.) by heat shock. Can J Biochem. 1982 May;60(5):569–579. doi: 10.1139/o82-070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke J. J., Hatfield J. L., Klein R. R., Mullet J. E. Accumulation of heat shock proteins in field-grown cotton. Plant Physiol. 1985 Jun;78(2):394–398. doi: 10.1104/pp.78.2.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duck N., McCormick S., Winter J. Heat shock protein hsp70 cognate gene expression in vegetative and reproductive organs of Lycopersicon esculentum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 May;86(10):3674–3678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Key J. L., Lin C. Y., Chen Y. M. Heat shock proteins of higher plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981 Jun;78(6):3526–3530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.6.3526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan M., Nguyen H. T., Burke J. J. Heat shock protein synthesis and thermal tolerance in wheat. Plant Physiol. 1989 May;90(1):140–145. doi: 10.1104/pp.90.1.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C. Y., Roberts J. K., Key J. L. Acquisition of Thermotolerance in Soybean Seedlings : Synthesis and Accumulation of Heat Shock Proteins and their Cellular Localization. Plant Physiol. 1984 Jan;74(1):152–160. doi: 10.1104/pp.74.1.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist S., Craig E. A. The heat-shock proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 1988;22:631–677. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.22.120188.003215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist S. The heat-shock response. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:1151–1191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.005443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield M. A., Key J. L. Synthesis of the low molecular weight heat shock proteins in plants. Plant Physiol. 1987 Aug;84(4):1007–1017. doi: 10.1104/pp.84.4.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin B., Thorstenson Y. R. Stable Carbon Isotope Composition (deltaC), Water Use Efficiency, and Biomass Productivity of Lycopersicon esculentum, Lycopersicon pennellii, and the F(1) Hybrid. Plant Physiol. 1988 Sep;88(1):213–217. doi: 10.1104/pp.88.1.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nover L., Scharf K. D., Neumann D. Formation of cytoplasmic heat shock granules in tomato cell cultures and leaves. Mol Cell Biol. 1983 Sep;3(9):1648–1655. doi: 10.1128/mcb.3.9.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nover L., Scharf K. D. Synthesis, modification and structural binding of heat-shock proteins in tomato cell cultures. Eur J Biochem. 1984 Mar 1;139(2):303–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rick C. M. HYBRIDIZATION BETWEEN LYCOPERSICON ESCULENTUM AND SOLANUM PENNELLII: PHYLOGENETIC AND CYTOGENETIC SIGNIFICANCE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1960 Jan;46(1):78–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.46.1.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rick C. M. Potential genetic resources in tomato species: clues from observations in native habitats. Basic Life Sci. 1973;2:255–269. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-2880-3_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf K. D., Nover L. Heat-shock-induced alterations of ribosomal protein phosphorylation in plant cell cultures. Cell. 1982 Sep;30(2):427–437. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]