Abstract

Objectives:

We examine whether police-reported crime is associated with adiposity and examine to what extent the association between crime and adiposity is explained by perceived neighborhood danger with a particular focus on gender differences.

Methods:

Data are drawn from the wave of 2010–2011 National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project merged with information on neighborhood social environment and FBI crime report. We use burglary as a main predictor. Waist circumference (WC) and body mass index (BMI) are used to assess adiposity.

Results:

Living in neighborhoods with higher levels of burglary is associated with a larger WC, a higher BMI, and greater adiposity risk for women, but not for men. These associations are partially explained by perceived danger among women.

Discussion:

Our findings identify neighborhood burglary rates as a contextual risk in later-life adiposity and highlight that perceived neighborhood safety contributes to gender differences in health outcomes.

Keywords: Environmental stress exposure, perceived neighborhood danger, adiposity risk, gender differences

Introduction

Aging takes place within context (Pruchno, 2018). Neighborhood has been considered a critical context that shapes health and well-being in later life (Diez Roux & Mair, 2010). Numerous studies have shown that exposures to unsafe and stressful neighborhood environments are predictive of disease risk in later life (for a review; see Lorenc et al., 2012; Won, Lee, Forjuoh, & Ory, 2016). Recent studies have suggested that, among potential sources of environmental stressors, crime and perceptions of neighborhood safety are considered consequential for older adult health, especially for adiposity. Older adults who live in high crime neighborhoods (Christman, Pruchno, Cromley, Wilson-Genderson, & Mir, 2016; Eisenstein et al., 2011) and in neighborhoods which they perceive as dangerous (Powell-Wiley et al., 2017) appear to be at higher risk for adiposity than those who live in safe neighborhoods.

Despite the contribution of earlier work in expanding our knowledge about how dangerous place affects weight status in older age, previous studies have largely focused on one type of neighborhood danger measure (e.g., either police-reported crime or subjective interpretations of those crime statistics). Although crime (objectively measured) and perceived safety (subjective interpretations) are linked yet distinct constructs, most existing research has interchangeably used them as proxies for environmental stressors and fails to disentangle their interdependent impacts on older adult health including adiposity (Eisenstein et al., 2011; Grafova, Freedman, Kumar, & Rogowski, 2008).

Furthermore, relatively little work has examined the role of gender in the association between crime and adiposity in later life, while there is a theoretical reason to expect that processes may work differently for men and women. For example, previous studies suggest that older women tend to respond to crime more emotionally than men because they fear being victimized (Moore & Shepherd, 2007; Snedker, 2015), while men tend to neutralize and downplay fear of crime due to social pressure not to reveal fear (Pain, 2000). Older women living in such vulnerable contexts may be then more likely to withdraw from public space and less likely to use outdoor space for physical activity, even walking in the neighborhood (Larson, Story, & Nelson, 2009). Less engagement in outdoor physical activity may result in energy imbalance, found to be a key contributor to body fat accumulation, especially in the abdomen (for a review; see Papas et al., 2007). Excessive abdominal fat, in particular, has been related to prolonged exposure to chronic stress among younger adults (Epel et al., 2000; Geiker et al., 2018). The current literature linking environmental stress to later-life adiposity has primarily examined total body fat assessed by BMI; how environmental stress is associated with abdominal fat among older adults remains unclear. A few recent studies have shown a more pronounced effect of neighborhood danger in women than men (Christman et al., 2016; Powell-Wiley et al., 2017), but the results have been based mainly on samples from single cities which limits generalizability to the general population.

In this study, by analyzing a nationally representative sample of older adults, we begin to fill the gap in our knowledge about how crime shapes adiposity, assessed by both waist circumference and BMI, in later life. We seek to investigate the extent to which the association between crime and adiposity is explained by perceptions of neighborhood safety and how this differs by gender.

Background

Crime, Perceived Safety, and Adiposity

“Aging in place” is a critical concept for healthy aging as the immediate environments can provide certain kinds of satisfaction and support—and yet a distressing, disordered environment can also impose stress and high risks of illness among older adults. Several theories in social gerontological work, including the Person-Environment Congruence Model (Kahana, 1982) and the Disability Model (Lawton, 1983), emphasize the effects of the environment in determining the health and well-being of older adults. Building on these theories, numerous studies have indicated that older adults – who tend to remain in the same residential areas as they age – become increasingly vulnerable to environmental stress because they have accumulated a longer duration exposure than young adults to unhealthy features of their environment, and because the changes in biological and psychological functioning associated with normal aging may reduce older adults’ competency to combat stress (Glass & Balfour, 2003).

Among other sources of environmental stressors, objective measures of a dangerous neighborhood such as police-reported crime statistics have been considered important characteristics by which to understand how bad place matters for health in later life. For instance, evidence based on social disorganization theory suggests that neighborhoods with high levels of crime affect later-life health through their impact on worries and danger about the neighborhoods (Browning, Cagney, & Iveniuk, 2012; Kawachi & Berkman, 2003). Research on the built environment indicates that high crime neighborhoods are more likely to be physically disordered, such that residents are presented with visible evidence of the breakdown of physical infrastructure in the local environment (e.g., run-down and abandoned buildings, vandalized physical structures, unkempt and dilapidated properties) (LaGrange, Ferraro, & Supancic, 1992). Exposure to such disorderly built environments may be especially stressful to residents because weakened social order and a lack of social control exacerbate feelings of threat and danger (Burdette & Hill, 2008).

The concentration of neighborhood disorder and decay has also been associated with residents’ reduced access to healthy food options and with a lower likelihood of healthy behaviors such as exercise. For example, Larson and colleagues (2009) suggested that individuals living in low-income neighborhoods have limited access to healthy food options due to a high prevalence of “food deserts” clustered in their neighborhoods, potentially creating obesogenic environments. Lovasi and colleagues (2009) indicated that poorly maintained sidewalks and lacking public parks that are commonly featured in physically disordered neighborhoods may also limit residents’ opportunities for physical activity. Residents living in disadvantaged neighborhoods are more likely to engage in other unhealthy behaviors, such as smoking and drinking, possibly as a means of coping with stress (Diez Roux & Mair, 2010). Physical inactivity, smoking, and heavy drinking have been identified as behavioral risks that have adverse health consequences for older adults including adiposity (Gordon-Larsen, Nelson, Page, & Popkin, 2006; Kruger, Ham, & Prohaska, 2008).

Although overlooked in the literature of “Aging in Place,” a growing body of research has demonstrated that subjective feelings about a neighborhood can also contribute to health. This prior work posits that objective conditions of neighborhood disorder may affect health outcomes through their impact on subjective interpretations of neighborhood safety which may increase fear and vulnerability among residents. For example, recent evidence has found that, relative to objective indicators of neighborhood danger, perceptions of neighborhood safety are more directly associated with depression (Latkin & Curry, 2003; Wilson-Genderson & Pruchno, 2013) and cognition (Lee & Waite, 2018). However, the current literature in the context of adiposity has either used subjective measures of neighborhood safety or objective measures of neighborhood danger interchangeably without distinguishing their independent pathways, direct and indirect, to disease risk (Eisenstein et al., 2011; Grafova, Freedman, Kumar, & Rogowski, 2008), or has collapsed them into one measure which could potentially mask their differential impacts on health (Glass, Rasmussen, & Schwartz, 2006; Powell-Wiley et al., 2015). Because high crime activity in the local area may be a mechanism that results in how people perceive the safety of their neighborhoods and surroundings, it is important to investigate the direct (objective) and potential indirect effects of crime on health through subjective interpretations.

Gender Differences in the Association between Environmental Stressors and Adiposity

Men and women may respond differently to the stress of living in a dangerous and distressing community. First, gender differences in biobehavioral responses to stress may shed light on gender differences in health related to neighborhood crime. According to Taylor (2011; [Taylor et al., 2000]), when women are in stressful conditions they may be more likely than men to adopt a “tend and befriend” strategy in which they manage stressful conditions by creating, maintaining, and relying on social groups for comfort and safety. Threatening circumstances trigger an increase in oxytocin, a hormone that can motivate affiliative behaviors which, with supportive others, can reduce potentially damaging biological stress responses including those that arise from elevated glucocorticoid levels (Taylor, 2011). However, if affiliation occurs with antagonistic and unsupportive others, oxytocin may worsen physiological stress responses (Stafford, Chandola, & Marmot, 2007). Men, on the other hand, typically follow the “fight-or-flight” pattern (Taylor et al., 2000), a behavioral strategy which is supported by the release of adrenaline into the blood stream to increase blood pressure and heart rate. The fight-or-flight response also results in high levels of glucocorticoids which have beneficial effects over the short term (e.g., mobilization of energy reserves) but have cumulative adverse effects on cognitive and physical health over the long term. Second, men and women may use different coping strategies when exposed to stressful circumstances. Evidence suggests that men engage in unhealthy behaviors such as cigarette smoking (Todd, 2004) and binge drinking (Cooper, Russell, Skinner, Frone, & Mudar, 1992) in response to stress, the result of which may be weight loss. Women, on the other hand, are more likely than men to cope with stress by eating (Jackson & Knight, 2006). An empirical study by Reagan and Hersch (2005) showed that, for women, the frequency of binge eating increases with depressive symptoms, and with spending a large fraction of daily life in disadvantaged neighborhoods.

These findings on gender differences in response to stress have led researchers to speculate as to distressing neighborhood conditions and gender differences in adiposity risk. In a community-based sample of older adults, for example, Glass et al. (2006) found that a composite variable of violent crime and other neighborhood disadvantage measures was significantly associated with a higher body mass index (BMI). With an adult sample from the Dallas Heart Study, Powell-Wiley et al. (2015) found an association between moving to more deprived neighborhoods (e.g., indexed by neighborhood-level violence, social cohesion and physical environment) and weight gain. Despite their attempts to expand our understanding about how dangerous neighborhoods shape BMI in later life, neither study examined how these associations differ by gender. Only a couple of studies have focused on gender differences in older age and have found that neighborhood characteristics are more strongly associated with BMI for women than men (Christman et al., 2016; Powell-Wiley et al., 2017). Most of the foregoing studies are based on localized samples (e.g., from single cities), and, as pointed out earlier, fail to differentiate between objective measures of crime activity and subjective interpretations of neighborhood safety. Violent crime has been the predominant measure of crime in past research, although evidence suggests that violent crime tends to be localized and occurs only rarely compared to other types of crime such as burglary. In fact, burglary is more prevalent than most other types of crime (e.g., second only to larceny; see Lauritsen & Rezey, 2013). In contrast to violent crime, burglary is unpredictable in location and timing. The unpredictable nature of burglary and possibilities of home violation are especially disruptive to feelings of safety and security, which may then magnify a sense of fear and vulnerability (Coakley & Woodford-Williams, 1979). This is particularly true for older adults for whom the home becomes increasingly important as mobility and functioning decreases. However, how burglary is associated with later-life health has been largely understudied.

Furthermore, none of these studies considered waist circumference and its association with crime (except for Powell-Wiley et al., 2017). According to Epel et al. (2000), excessive abdominal fat is a greater health risk than is whole-body fat. Abdominal fat serves as an indicator of prolonged exposure to high levels of glucocorticoids that may result from chronic stress exposure (McEwen, 1998, 2003). Although the findings above consider neighborhood context as a risk factor for adiposity, additional research employing both BMI and waist circumference is needed; the significance of neighborhood context on adiposity-related outcomes for older adults will be better understood with a more nuanced approach to adiposity status.

Hypotheses

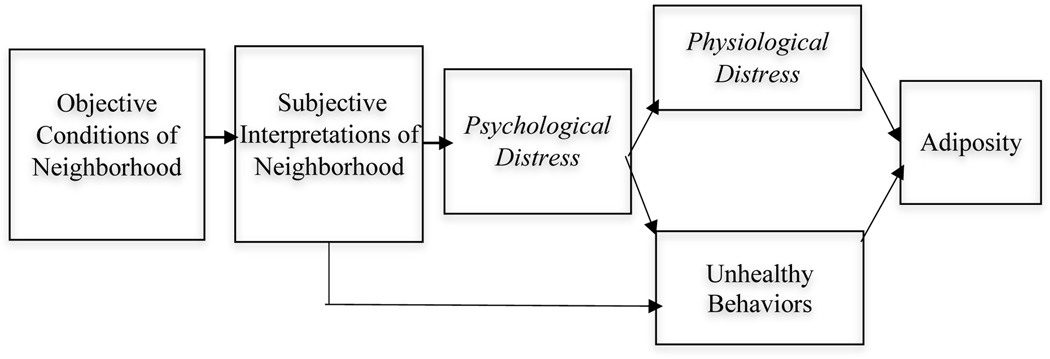

The current study seeks to examine whether crime (burglary) is associated with adiposity in older adults and the extent to which the association between crime and adiposity is explained by neighborhood perceptions. As seen in Figure 1, we consider psychological distress a key mechanism linking environmental stressors with adiposity risk through changes in physiological functioning and adoption of unhealthy behaviors (i.e., physical inactivity, drinking, smoking). We posit that the association between crime and adiposity may differ between men and women in part because women may interpret crime and respond to psychological distress differently than men. Using both BMI and waist circumference as indicators for adiposity, we hypothesize that: (1) the association between police-reported burglary and adiposity will be greater in women than men; and (2) neighborhood perceptions will explain the association between police-reported burglary and adiposity.

Figure 1.

Analytical Framework of a Process by Which Environmental Stressors Shape Adiposity

Note: Italicized font is used for each variable that we did not include in the analytical model due to lack of data but included here to illustrate relationships in the analytical framework; all the variables that were measured in the analytical model are in regular font. Objective conditions of neighborhood disorder include crime, and the measure of subjective interpretations of neighborhood include perceived danger and distrust.

Source: Authors

Data and Methods

Sample

The National Social Life, Health and Aging Project (NSHAP W2) is a population-based study of older community-dwelling Americans. The NSHAP sample is selected using a multistage area probability design, and data collection consists of an in-person interview that includes biomeasure collection, and a leave-behind questionnaire that is returned by postage-paid mail (O’Muircheartaigh, English, Pedlow, & Kwok, 2014). The full sample of respondents available in NSHAP W2 was 2,261. Given that crime is concentrated in densely populated urban areas, we limited our analytic sample to urban dwelling respondents (N=1,708; 75.81%). We identified urban areas as metropolitan areas of more than 50,000 residents based on the 2010 Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) codes 1 through 3 (United States Department of Agriculture, 2016). The analytic sample consisted of 823 males (48.2% of sample) and 885 females.

Adiposity Measures

Two measures of adiposity were investigated as dependent variables: waist circumference and BMI. Waist circumference was measured in inches and converted to centimeters. Height and weight were measured by field interviewers, and BMI was derived by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared. Cases with extreme (unrealistic) BMI and waist values that suggested errors in measurement and/or transcription were dropped from analyses (N=46, or 2.7% of cases). Of the remaining values, statistical outliers (i.e., greater than three standard deviations from the mean) were treated as missing (N=27, or 1.6% of 1,662 retained cases). Sensitivity analyses truncating outlier values to three standard deviations from the mean did not substantively change our findings, so we elected to leave these values coded as missing.

In addition, waist circumference and BMI were dichotomized to generate measures of abdominal and general obesity, respectively. Abdominal adiposity was defined as a waist circumference greater than 102 cm in men and greater than 88 cm in women (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 1998). BMI was used to classify respondents as obese (BMI >29.9) based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines, 2016).

Police-Reported Crime and Perceived Neighborhood Context

County-level geocoded crime data were derived from the FBI Uniform Crime Report (UCR) and purchased from Applied Geographic Solutions (AGS). These data included rates of murder, rape, robbery, assault, burglary, larceny, and motor vehicle theft, standardized to represent county-level rates as a proportion of the national rate (e.g., burglary index = (number of burglary incidents at counties*100)/number of national burglary incidents). This burglary index was right-skewed, so we divided burglary rates into tertiles (e.g., low, medium, and high) for analytic purposes. We chose to model burglary at the county-level because we believe that (1), informed by recent research on “activity space,” older adults may be exposed to a much broader range of space than only their residential location (Cagney, Browning, Jackson, & Soller, 2013) and (2) disorder has a spill-over effect across adjacent neighborhoods (Sampson, 2012; Skogan, 1992). In assessing perceived neighborhood context, we constructed scales for perceived neighborhood danger (alpha = 0.80) and distrust (alpha=0.67) from the NSHAP respondents’ report on their local areas. In NSHAP, local areas were defined as everywhere within a 20-minute walk or within about a mile of respondent’s home. For a scale of perceived neighborhood danger, respondents were asked to indicate, using a 5 point Likert scale (from “strongly disagree” coded as 1 to “strongly agree” coded as 5), how afraid they are to go out at night, how much trouble is expected, and if they are taking a big chance walking alone after dark in local areas. We considered the items used in the scale of perceived neighborhood danger to capture the degree of feelings of fear of individuals’ reactions to community crime. Perceived neighborhood distrust was defined by items that assess whether neighbors can be trusted, get along, share values and help each other, and whether the neighborhood is close-knit, using the same 5 point scale as was used for perceived neighborhood danger. We then reverse-coded the scale so that higher values reflect greater neighborhood distrust and lack of security. The correlation matrix indicates that objective and subjective neighborhood measures were positively correlated with each other, with perceived danger exhibiting a larger correlation with burglary than neighborhood distrust (Supplemental Table 1). Validation of the measurement of neighborhood perceptions has been published elsewhere (Cornwell & Cagney, 2014).

Health Behaviors

Previous research identified physical inactivity, cigarette smoking, and heavy drinking as risk behaviors that have adverse impacts on older adults’ weight status (Kruger et al., 2008; Watson, 2016). Smoking status was assessed as: (1) never (reference group); (2) ever; and (3) currently smoking. To measure daily alcohol consumption (number of drinks per day), we grouped respondents into 3 categories: (1) none (reference group); (2) moderate (1 to 3 drinks/day); and (heavy (+3 drinks/day). Evidence indicates that in older adults, physical inactivity (sedentariness) is associated with excess weight (Gordon-Larsen, Nelson, Page, & Popkin, 2006), and that replacing sedentary time with even light intensity physical activity has been associated with lower BMI (Bann et al., 2015). We therefore compared respondents who reported no activity (coded=1) with those who reported doing any activity (reference group).

Covariates

Baseline demographic characteristics included age, race/ethnicity, living arrangement and education attainment. The range of respondents’ age was 62 to 90 years. We grouped respondents into three age brackets: (1) 62–70, (2) 71–80, and (3) 81– 90, to capture any differences across sub-groups at older ages (i.e., young old, middle old and oldest-old). Race/ethnicity was self-reported as: (1) Non-Hispanic White, (2) Non-Hispanic African American, (3) Hispanic, and (4) Other. Because we believe that living alone may decrease feelings of security and safety, and increase fear of crime and victimization compared to living with someone, we controlled for living arrangement (living alone=1; otherwise=0). Educational attainment was classified into four levels: (1) less than high school, (2) high school or equivalent, (3) some college, and (4) college or more. Previous victimization experiences are highly correlated with fear of crime (Lauritsen & Rezey, 2013), and we therefore included prior victimization (i.e., having been a victim of a violent crime in the past 2 years) as a covariate. Chronic disease burden was also included as a covariate because it may be related to adiposity. The NSHAP comorbidity index includes fifteen prevalent health conditions in older adults. Detailed information on the use of chronic condition data to calculate a comorbidity index has been published elsewhere (Vasilopoulos et al., 2014). Neighborhood disadvantage and physical disorder measures were included as covariates because they have been documented to be related to both crime and adiposity. We constructed the disadvantage measure by standardizing and summing the following items from 2006–2009 American Community Survey: (1) percent households living in poverty; (2) percent households receiving public assistance; (3) percent adults (≥25 years olds) with a high school diploma or less; and (4) percent unemployed (≥ 16 years olds) (alpha=0.63). We measured physical disorder using field interviewers’ responses to two questions about the respondent’s immediate built environment: “How well kept is the building in which the respondent lives?” and “How well kept are most of the buildings on the street (1 block, both sides) where the respondent lives?” Responses ranged from very well kept (=1) to very poorly kept (=4; needs major repairs). Values were averaged across the two items (alpha =0.83), with higher scores indicating greater physical disorder.

Analytic Strategy

Because we expected that multiple neighborhood social contexts produce the ramifications of stress, including older adults’ adiposity, we fit sequential models, beginning by examining adiposity as a function of objective crime, namely burglary (Model 1 in Table 2). In Model 2, we added neighborhood perceptions – neighborhood danger and distrust – to assess the extent to which neighborhood perceptions explain the association between burglary and adiposity measurements. In Model 3, we added health behavior variables to test their explanatory capacity. Waist circumference and BMI are continuous variables, so we fit OLS linear regression models. In the case of dichotomous variables for abdominal and general adiposity, multivariate logit regression models were employed. Because we expected that responses to environmental stressors may differ by gender, all analyses were completed separately for men and women. Because NSHAP respondents are spread out across the United States rather than clustered within counties, multilevel modeling with individuals nested within counties is not feasible. In the current study, descriptive statistics and all analytical models were adjusted for survey design (STATA 14). This procedure corrected for multiple stages of cluster sample design and unequal probability of selection to ensure nationally representative results with unbiased standard errors.

Table 2.

Multivariate Regression Predicting Gender Differences in the Association Between Crime and Waist Circumference/BMI

| Waist Circumference | BMI | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|

| Objective Neighborhood Disorder | ||||||||||||

| Crime (Burglary) | ||||||||||||

| Low (=ref.) | ||||||||||||

| Medium | −0.15 | −0.66 | −0.31 | 1.27 | 1.02 | 0.59 | −0.17 | −0.20 | −0.03 | 0.62 | 0.75 | 0.44 |

| High | −0.15 | −0.66 | −0.31 | 4.55* | 4.44* | 4.05* | −0.31 | −0.35 | −0.36 | 1.42* | 1.29* | 1.07 |

| Subjective Neighborhood Disorder | ||||||||||||

| Perceived Danger | 0.94 | 1.10 | 1.49* | 1.56* | −0.04 | −0.01 | 1.18*** | 1.14*** | ||||

| Perceived Distrust | 0.69 | 0.88 | −0.81 | −1.53 | 0.37 | 0.35 | −0.25 | −0.57 | ||||

| Health Behaviors | ||||||||||||

| Smoking | ||||||||||||

| Never (=ref.) | ||||||||||||

| Ever | 0.61 | 0.10 | −0.47 | −0.34 | ||||||||

| Currently Smoking | −3.17 | −8.01*** | −2.05* | −3.12** | ||||||||

| Drinking | ||||||||||||

| None (=ref.) | ||||||||||||

| Moderate | −0.15 | −0.59 | −0.08 | −0.71 | ||||||||

| Heavy | −6.27* | −3.29 | −0.20 | −3.16* | ||||||||

| No Exercise | −0.21 | 4.90** | 0.12 | 2.28*** | ||||||||

| Covariates a | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

Note:

p<0.05

p<0.01

<0.001

All models are adjusted for covariates including age, race/ethnicity, living arrangement, educational attainment, prior victimization, neighborhood socioeconomic status, physical disorder and NSHAP comorbidity index.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

As shown in Table 1, men, relative to women, had a larger waist (105.5 vs. 94.3) and a higher BMI (29.1 vs. 28.7), and were more likely to be obese (39.3% vs. 36.4%). Women were more likely than men to have abdominal adiposity (64.1% vs. 52.5%). In addition, men were more likely to live in deleterious, distressing neighborhood contexts characterized by higher levels of burglary and perceived neighborhood distrust. Despite a lower exposure to burglary, women were more likely to perceive neighborhoods as dangerous. Notably, men were more likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors. For example, 14.5% and 7.8% of men reported current use of cigarettes and heavy drinking, compared to women (10.8% and 1.4%, respectively). However, approximately 10 percent more women reported that they do not exercise.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Key Variables, Weighted and Adjusted for Survey Design

| Men (N=823) | Women (N=885) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Variable Name | Percent (na) / Mean | (SD) | Percent (n) / Mean | (SD) |

| Outcome Variables | ||||

| Waist circumference (cm) | 105.50 | (14.16) | 94.34 | (15.13) |

| BMI | 29.09 | (5.20) | 28.74 | (6.04) |

| Abdominal adiposity | 52.50% (432) | 64.06% (567) | ||

| General adiposity | 39.29% (323) | 36.42% (332) | ||

| Crime Index | ||||

| Burglary index | 108.62 | (50.78) | 107.93 | (50.83) |

| Neighborhood Characteristics | ||||

| Disadvantage index | 0.16 | (.08) | 0.16 | (.07) |

| Physical disorder index | 0.52 | (.68) | 0.57 | (.67) |

| Perceived danger index | 2.34 | (.91) | 2.46 | (.83) |

| Perceived distrust index | 2.57 | (.52) | 2.50 | (.54) |

| Individual Characteristics | ||||

| Age | ||||

| 62–70 | 52.54% (432) | 44.40% (393) | ||

| 71–80 | 31.47% (259) | 34.51% (305) | ||

| 80 and up | 15.99% (132) | 21.09% (187) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 76.95% (633) | 77.57% (686) | ||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 10.91% (90) | 12.44% (110) | ||

| Hispanic | 8.99% (74) | 8.04% (71) | ||

| Other | 3.15% (26) | 1.95% (18) | ||

| Living alone | 27.39% (225) | 38.69% (342) | ||

| Education | ||||

| < HS | 14.02% (115) | 17.79% (157) | ||

| HS | 20.76% (171) | 25.74% (228) | ||

| Some college | 28.06% (231) | 34.37% (304) | ||

| BA or more | 37.16% (306) | 22.10% (196) | ||

| Prior victimization | 4.19% (35) | 3.27% (29) | ||

| NSHAP comorbidity index | 2.21 | (1.42) | 2.35 | (1.26) |

| Health Characteristics | ||||

| Smoking | ||||

| Never | 24.96% (205) | 49.96% (442) | ||

| Ever | 60.50% (498) | 39.26% (347) | ||

| Currently smoking | 14.54% (120) | 10.78% (96) | ||

| Drinking | ||||

| None | 33.41% (275) | 46.77% (414) | ||

| Moderate | 58.81% (484) | 51.83% (459) | ||

| Heavy | 7.78% (64) | 1.40% (12) | ||

| No exercise | 17.80% (146) | 28.73% (254) | ||

Note:

Values presented in parentheses are raw numbers while we obtain percentages adjusted for survey design.

Multivariate Models

Is the Association Between Burglary and Adiposity Greater in Women than Men?

Results in Table 2 showed that burglary is positively associated with waist circumference for women, not for men. As shown in Model 1s, living in the highest burglary areas increased waist circumference by 4.55 cm (p<0.05) among women controlling for individual socio-demographic factors. Similarly, we found gender differences in the association between burglary and BMI. Women residing in the highest burglary communities were more likely to have a higher BMI, but again, not so for men (β=1.42, p<0.05). Results were strikingly different for men. Among men, Model 1s of Table 2 indicates a negative relationship between living in a high-burglary neighborhood and waist circumference and BMI. However, this relationship was not statistically significant throughout the models.

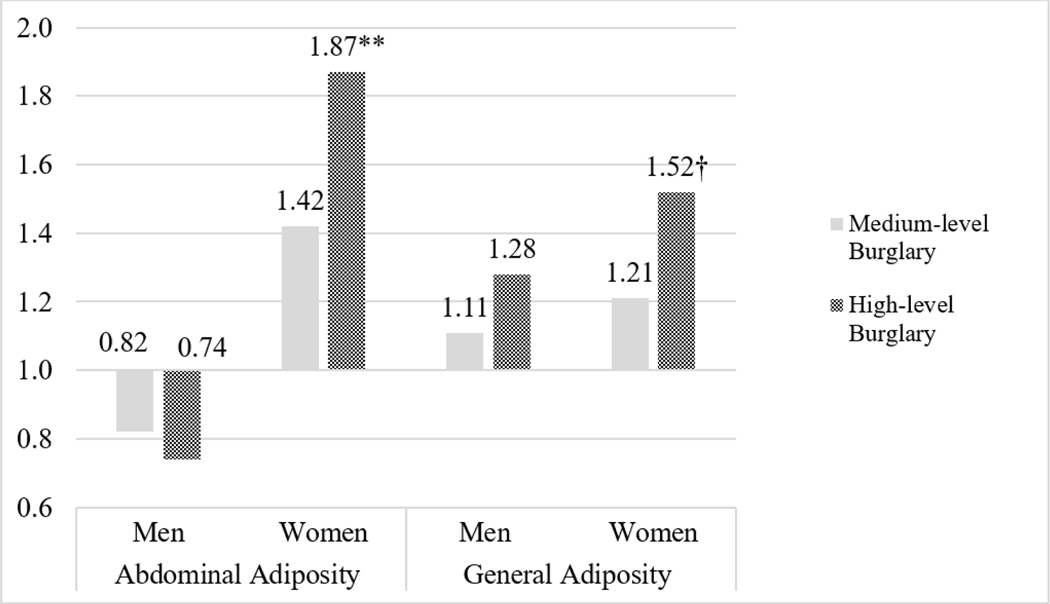

In order to examine whether burglary increases risk for exceeding adiposity thresholds, we fitted the logistic regressions with abdominal and general adiposity as the outcomes (Supplemental Table 2). Consistent with the results from Table 2, we found that living in neighborhoods with high levels of burglary were associated with adiposity only for women. As seen in Figure 2, for women, living in neighborhoods with high burglary rates increased their odds of abdominal adiposity (OR=1.87, p<0.01) and general adiposity, although marginally significant (OR=1.52, p<0.10; results from final Model 3s). We did not see the same pattern in men. To formally evaluate whether the association between burglary and adiposity differed between men and women, we used “seemingly unrelated estimation” and the Paternoster test (Paternoster, Brame, Mazerolle, & Piquero, 1998). Results confirmed that the regression coefficients for burglary coefficients (both Table 2 and Supplemental Table 2) differed significantly between men and women.

Figure 2.

Odds Ratios Predicting Gender Differences in the Association Between Burglary and Abdominal/General Adiposity

Note: † p<0.10, ** p<0.01. Odds ratios are from the final models that control for neighborhood context, health-related behaviors and socio-demographic characteristics.

Do Perceptions of Neighborhood Danger and Distrust Explain the Association Between Burglary and Adiposity?

Results from Model 2s show that inclusion of perceptions of neighborhood danger and distrust decreased the impact of burglary on waist circumference to 4.44 cm (p<0.05). Similarly, the addition of neighborhood perceptions further reduced the relationship between burglary and BMI in women (β=1.29 p<0.05). In large part, these reductions were attributable to the statistically significant impact of perceived danger on waist circumference and BMI (β=1.49 p<0.05 and β=1.18 p<0.001, respectively). This finding also suggests that the impact of high levels of burglary may be overestimated when we do not account for perceptions of neighborhood danger.

We additionally tested whether the associations between environmental stressors and adiposity were persistent after controlling for health behaviors in Model 3s. The relationship between burglary and waist circumference was further reduced but retained statistical significance when health behaviors were added, (β=4.05; p<0.05), while the relationship between burglary and BMI became no longer significant. Among health behaviors, smoking was associated with smaller waist circumference and lower BMI, while sedentariness was associated with wider waist circumference and higher BMI. Among covariates (results not shown), higher comorbidity and older age were associated with larger waist circumference for both men and women. Non-Hispanic Black race/ethnicity and higher comorbidity were associated with a larger BMI among women. Only older age was associated with a smaller BMI for men.

Discussion

Although previous studies have demonstrated that elderly women are more likely than men to express fear of crime and to respond emotionally to stressful environments, the role of gender in conditioning the effects of environmental stressors on health in later life has been understudied. Incorporating insights from social disorganization theory and the tend-and-befriend theory from research in social psychology, this study built on previous research by examining gender differences in the impact of crime on adiposity for urban-dwelling older adults. We aimed to investigate whether one type of crime, burglary, is associated with greater adiposity risk (i.e., larger waist circumference, higher BMI, and higher likelihood of being obese and abdominally obese) in women than men at older ages. We further examined whether neighborhood perceptions explained the association between burglary and adiposity outcomes.

We underscore three main findings. First, largely consistent with social disorganization theory, we found that high (vs. low) levels of burglary were associated with an increased risk of adiposity. Second, only women exhibited this association, consistent with the tend-and-befriend theory which suggests that women may experience and interpret crime differently than men. Third, perceptions of neighborhood danger, indicative of feelings of fear, helped to explain the association between burglary and adiposity risk among women.

Why might levels of burglary affect women but not men? First, men and women may differ in how much psychological stress they experience in structurally disordered and dangerous environments. Women may perceive greater threat and fear in such environments and their perceptions may contribute to differences in adiposity. Further, women who live in a disordered environment may be more fearful, vulnerable and sensitive to burglary because they fear not only loss of property, but also other offenses—homicide, assault, rape—that may accompany burglary (Warr, 1985). Second, women may be socialized to internalize distress, whereas men may be socialized to externalize distress (Horwitz & White, 1987). Thus, women may be more likely to exhibit symptoms of depression and anxiety (Cooper et al., 1992), whereas men may be more likely to engage in maladaptive health behaviors such as smoking cigarettes in response to stressful circumstances (Todd, 2004). In addition, men and women may adopt different coping strategies. Previous studies have demonstrated that women may be more likely than men to engage in binge eating or overeating as a coping mechanism (Jackson & Knight, 2006), for which the results may contribute to excess abdominal fat. Lastly, it also may be the case that the influence of crime on adiposity for women is affected by other social contexts not examined in this study. For example, social participation (i.e., religious group, volunteering) and formal and informal social ties among community members may act to buffer psychological distress related to fear of crime. Evidence suggests that women are less likely than men to go outside if they perceive their neighborhoods as unsafe (Bengoechea, Spence, & McGannon, 2005). It is plausible to expect that crime might have a greater impact on adiposity for women if they avoid social engagement and its potentially stress-buffering benefits due to fear of unsafe and disordered neighborhoods.

One of the strengths of this study is that we examined objective measures (policed-reported crime statistics) and subjective interpretations (perceived neighborhood danger) of neighborhood characteristics as potential mechanisms for the significance of crime on adiposity. Although the adverse associations of crime with adiposity are not new, most existing research has examined actual crime rates and perceived neighborhood crime separately as main contributors (Stafford et al., 2007; Stockdale et al., 2007). Far fewer analyses have explicitly disentangled the potential pathways underlying different impacts of environmental stressors on individual-level health outcomes across various levels of aggregation. Our results suggest that crime operates at a higher level such that county-level criminal activity has health implications for individual-level outcomes primarily through how people perceive their local areas, which in the case of adiposity is found to be salient only for women. We believe this may be partially attributed to the ways in which local crime in news media coverage filters down to how people perceive the area directly around them. For instance, research has shown that women have a greater affinity than men for victims of crime in news reports, and affinity was strongly related to fear of crime, even after adjusting for own perceived safety (Chiricos, Eschholz, & Gertz, 1997). In addition, media coverage of crime in the local area is often exaggerated and may cue people that crime can unexpectedly occur in their own homes (Lowry, Nio, & Leitner, 2003). It is possible that county-level crime rates become a key aspect of a county’s “identity” that is well known to its residents, even if they live in less affected areas of the county. Moreover, the seeming randomness of crime locations outside of high-crime areas may exacerbate fear and increase the vulnerability perceived in individuals’ own communities. This implies that specifying a boundary of crime to a smaller geographic unit such as a census tract may underestimate the impact of perceived crime on health.

An additional strength of our approach is that we examined adiposity-associated objective and subjective neighborhood characteristics in older adults, and separately by gender. The neighborhood context may be particularly important to older adults, as suggested by research showing that attachments to place become stronger in later life subsequent to retirement and loss of confidants (Peace, Kellaher, & Holland, 2005). Yet, studies of the association between neighborhood environment and adiposity among older adults have been relatively rare (Christman et al., 2016; Glass et al., 2006; Powell-Wiley et al., 2015; Wilson-Genderson & Pruchno, 2013). To our knowledge, this is the first study to elucidate the relationship between environmental exposures—both objectively and subjectively measured-- and adiposity with a nationally representative sample of older adults in the United States. Moreover, our finding – that the relationship between burglary and higher adiposity risk among women is partially explained by perceptions of danger – clarifies possible sources of gender differences in adiposity status.

The present study also examines not only BMI but also waist circumference as a marker of physiological processes sensitive to conditions of chronic stress that may prevail in high crime communities. The use of two anthropometric measures of adiposity helps us to better understand the implications of both psychological and physiological pathways on excessive fat deposition, namely that not only total body fat but also abdominal fat may be affected. This is consistent with the known association between chronic stress and abdominal obesity, and reinforces the importance of place in health.

Our analyses are not without limitations. First, the results of the study were based on cross-sectional analyses, and it is not possible to suggest causal effects. NSHAP is an ongoing panel study, and it will be possible in the future to take a more nuanced approach to the question of causality. For instance, will adiposity increase at a faster rate among older women living in high-crime than low-crime counties? Second, although we believe that both the activity space perspective and the potential for disorder to have spillover effects theoretically support our decision to use the crime index at the county-level, in general, we know little about how fear of crime and perceptions are formed, changed or maintained by the more local versus distal environments. This is where data collection methods that rely on activity space tracking and ecological momentary assessment (i.e., real-time social surveys) may contribute, since they would deliver both information on the space traversed and immediate information on perceptions. Lastly, other individual-level mediators such as nutrition and dieting history (i.e., fruit and vegetable consumption, quality of diet) and exposure to media reports of crime may be directly or indirectly related to the adiposity of older adults, but NSHAP does not include these data. Additional research is needed to examine their role in contributing to adiposity in later life.

In conclusion, the present study expands research on adiposity and health to include the influence of neighborhood environmental stressors. Our analyses focused on community crime and perceptions of neighborhood danger as potential sources of health disparities at older ages. Results suggest that the local neighborhood environment may be a highly relevant source of potential stress, to the extent that it shapes perceptions of safety and security that, in turn, produce physiological manifestations of stress. Our findings provide evidence that gendered responses to stress and coping may have consequences for weight status.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Haena Lee, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, 426 Thompson St., #3428, Ann Arbor, MI 48104, USA.

Ann Arbor, MI 48104, USA.

Kathleen A. Cagney, The University of Chicago, IL, USA

Louise Hawkley, NORC at the University of Chicago, IL USA.

References

- Browning CR, Cagney KA, & Iveniuk J. (2012). Neighborhood stressors and cardiovascular health: Crime and C-reactive protein in Dallas, USA. Social Science & Medicine, 75(7), 1271–1279. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdette AM, & Hill TD (2008). An examination of processes linking perceived neighborhood disorder and obesity. Social Science & Medicine, 67(1), 38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagney KA, Browning CR, Jackson AL, & Soller B. (2013). Networks, neighborhoods, and institutions: An integrated “activity space” approach for research on aging. In New direction in the sociology of aging (pp. 117–174). National Research Council of the National Academies. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines. (2016). Defining adult overweight and obesity. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/defining.html

- Chiricos T, Eschholz S, & Gertz M. (1997). Crime, news and fear of crime: Toward an identification of audience effects. Social Problems, 44(3), 342–357. [Google Scholar]

- Christman Z, Pruchno R, Cromley E, Wilson-Genderson M, & Mir I. (2016). A spatial analysis of body mass index and neighborhood factors in community-dwelling older men and women. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 83(1), 3–25. 10.1177/0091415016645350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coakley D, & Woodford-Williams E. (1979). Effects of burglary and vandalism on the health of old people. The Lancet, 314(8151), 1066–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, Skinner JB, Frone MR, & Mudar P. (1992). Stress and alcohol use: Moderating effects of gender, coping, and alcohol expectancies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101(1), 139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell EY, & Cagney KA (2014). Assessment of neighborhood context in a nationally representative study. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(Suppl 2), S51–S63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez Roux AV, & Mair C. (2010). Neighborhoods and health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1186(1), 125–145. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05333.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein AR, Prohaska TR, Kruger J, Satariano WA, Hooker S, Buchner D, … Hunter RH (2011). Environmental correlates of overweight and obesity in community residing older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 23(6), 994–1009. 10.1177/0898264311404557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epel ES, McEwen B, Seeman T, Matthews K, Castellazzo G, Brownell KD, … Ickovics JR (2000). Stress and body shape: Stress-induced cortisol secretion is consistently greater among women with central fat: Psychosomatic Medicine, 62(5), 623–632. 10.1097/00006842-200009000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass TA, & Balfour JL (2003). Neighborhoods, aging, and functional limitations. In Neighborhoods and health (pp. 303–334). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glass TA, Rasmussen MD, & Schwartz BS (2006). Neighborhoods and obesity in older adults: The Baltimore Memory Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 31(6), 455–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Larsen P, Nelson MC, Page P, & Popkin BM (2006). Inequality in the built environment underlies key health disparities in physical activity and obesity. Pediatrics, 117(2), 417–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grafova IB, Freedman VA, Kumar R, & Rogowski J. (2008). Neighborhoods and obesity in later life. American Journal of Public Health, 98(11), 2065–2071. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.127712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz AV, & White HR (1987). Gender role orientations and styles of pathology among adolescents. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 28(2), 158–170. 10.2307/2137129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, & Knight KM (2006). Race and self-regulatory health behaviors: The role of the stress response and the HPA axis in physical and mental health disparities. In Social structures, aging, and self-regulation in the elderly (pp. 189–207). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kahana E. (1982). A congruence model of person-environment interaction. In Aging and the environment: Theoretical approaches (pp. 97–121). Springer Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, & Berkman LF (2003). Neighborhoods and health. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kruger J, Ham SA, & Prohaska TR (2008). Behavioral risk factors associated with overweight and obesity among older adults: the 2005 national health interview survey. Preventing Chronic Disease, 6(1). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaGrange RL, Ferraro KF, & Supancic M. (1992). Perceived risk and fear of crime: Role of social and physical incivilities. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 29(3), 311–334. [Google Scholar]

- Latkin CA, & Curry AD (2003). Stressful neighborhoods and depression: A prospective study of the impact of neighborhood disorder. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 34–44. [PubMed]

- Lauritsen JL, & Rezey ML (2013). Measuring the prevalence of crime with the National Crime Victimization Survey. Bureau of Justice Statistics, US Department of Justice, Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP (1983). Environment and other determinants of weil-being in older people. The Gerontologist, 23(4), 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, & Waite LJ (2018). Cognition in context: The role of objective and subjective measures of neighborhood and household in cognitive functioning in later life. The Gerontologist, 58(1), 159–169. 10.1093/geront/gnx050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenc T, Clayton S, Neary D, Whitehead M, Petticrew M, Thomson H, … Renton A. (2012). Crime, fear of crime, environment, and mental health and wellbeing: Mapping review of theories and causal pathways. Health & Place, 18(4), 757–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovasi GS, Hutson MA, Guerra M, & Neckerman KM (2009). Built environments and obesity in disadvantaged populations. Epidemiologic Reviews, mxp005. 10.1093/epirev/mxp005 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lowry DT, Nio TCJ, & Leitner DW (2003). Setting the public fear agenda: A longitudinal analysis of network TV crime reporting, public perceptions of crime, and FBI crime statistics. Journal of Communication, 53(1), 61–73. 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2003.tb03005.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS (1998). Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 840(1), 33–44. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS (2003). Interacting mediators of allostasis and allostatic load: Towards an understanding of resilience in aging. Metabolism, 52, 10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SC, & Shepherd J. (2007). Gender specific emotional responses to anticipated crime. International Review of Victimology, 14(3), 337–351. 10.1177/026975800701400304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (1998). Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. Obes Res, 6(Suppl 2), 51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pain R. (2000). Place, social relations and the fear of crime: A review. Progress in Human Geography, 24(3), 365–387. [Google Scholar]

- Papas MA, Alberg AJ, Ewing R, Helzlsouer KJ, Gary TL, & Klassen AC (2007). The built environment and obesity. Epidemiologic Reviews, 29(1), 129–143. 10.1093/epirev/mxm009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peace S, Kellaher L, & Holland C. (2005). Environment and identity in later life. McGraw-Hill Education (UK). [Google Scholar]

- Powell-Wiley TM, Cooper-McCann R, Ayers C, Berrigan D, Lian M, McClurkin M, … Leonard T. (2015). Change in neighborhood socioeconomic status and weight gain. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49(1), 72–79. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell-Wiley TM, Moore K, Allen N, Block R, Evenson KR, Mujahid M,…V,A. (2017). Associations of neighborhood crime and safety and with changes in body mass index and waist circumference the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. American Journal of Epidemiology, 186(3), 280–288. 10.1093/aje/kwx082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruchno R. (2018). Aging in context. The Gerontologist, 58(1), 1–3. 10.1093/geront/gnx189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reagan P, & Hersch J. (2005). Influence of race, gender, and socioeconomic status on binge eating frequency in a population-based sample. The International Journal Of Eating Disorders, 38(3), 252–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ (2012). Great American city: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Skogan WG (1992). Disorder and decline: Crime and the spiral of decay in American neighborhoods. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Snedker KA (2015). Neighborhood conditions and fear of crime: A reconsideration of sex differences. Crime & Delinquency, 61(1), 45–70. 10.1177/0011128710389587 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford M, Chandola T, & Marmot M. (2007). Association between fear of crime and mental health and physical functioning. American Journal of Public Health, 97(11), 2076–2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockdale SE, Wells KB, Tang L, Belin TR, Zhang L, & Sherbourne CD (2007). The importance of social context: Neighborhood stressors, stress-buffering mechanisms, and alcohol, drug, and mental health disorders. Social Science & Medicine, 65(9), 1867–1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE (2011). Tend and befriend theory. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology: Collection: Volumes 1 & 2 (pp. 32–49). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Klein LC, Lewis BP, Gruenewald TL, Gurung RAR, & Updegraff JA (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107(3), 411–429. 10.1037/0033-295X.107.3.411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd M. (2004). Daily processes in stress and smoking: Effects of negative events, nicotine dependence, and gender. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18(1), 31–39. 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilopoulos T, Kotwal A, Huisingh-Scheetz MJ, Waite LJ, McClintock MK, & Dale W. (2014). Comorbidity and chronic conditions in the National Social Life, Health and Aging Project (NSHAP), Wave 2. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(Suppl 2), S154–S165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warr M. (1985). Fear of rape among urban women. Social Problems, 32(3), 238–250. [Google Scholar]

- Watson KB (2016). Physical inactivity among adults aged 50 years and older—United States, 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson-Genderson M, & Pruchno R. (2013). Effects of neighborhood violence and perceptions of neighborhood safety on depressive symptoms of older adults. Social Science & Medicine, 85, 43–49. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won J, Lee C, Forjuoh SN, & Ory MG (2016). Neighborhood safety factors associated with older adults’ health-related outcomes: A systematic literature review. Social Science & Medicine, 165, 177–186. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.