Abstract

Cocultures of Desulfovibrio desulfuricans and Methanococcus maripaludis grew on sulfate-free lactate medium while vigorously methylating Hg2+. Individually, neither bacterium could grow or methylate mercury in this medium. Similar synergistic growth of sulfidogens and methanogens may create favorable conditions for Hg2+ methylation in low-sulfate anoxic freshwater sediments.

Biomethylation of Hg2+ by sulfidogens in anoxic aquatic sediments (6) produces highly toxic methylmercury pollutants that have a tendency to accumulate in fish (8, 26). Somewhat paradoxically, in high-sulfate estuarine sediments, the rate of Hg2+ methylation is far lower than the rate of Hg2+ methylation in low-sulfate freshwater sediments (4, 7). The reason for this appears to be the generation of H2S by the Hg2+-methylating sulfidogens, although the exact mechanism of the H2S inhibition is uncertain at this time. Most oligotrophic freshwater lakes show no outward evidence of sulfidogenic activity, such as blackening or an H2S odor in their sediments. We measured high rates of Hg2+ methylation in oligotrophic lake sediments that were free of detectable H2S and evolved methane vigorously (19). As inhibition studies have consistently excluded methanogens and implicated sulfidogens in Hg2+ methylation (6, 7), one is led to question how sulfidogens stay active and methylate Hg2+ in environments that, because of likely sulfate limitation, seem to be inhospitable to them. Based on these considerations and on several reports of interspecies hydrogen transfers between sulfidogens and methanogens (1, 5, 20), we decided to explore the potential effect of such transfers on the methylation of Hg2+ under sulfate-limited conditions. We modeled the proposed interaction in vitro by using pure cultures of sulfidogens and a methanogen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Routine anaerobic Hungate techniques were used. Nitrogen gas was passed through a reduced heated copper column to remove traces of oxygen. Desulfovibrio desulfuricans LS was isolated in our laboratory (6). It was repurified by repeatedly picking single colonies from shake tubes containing diagnostic media B and E of Postgate (21) solidified with 1.5% agar. D. desulfuricans ND 132 was kindly donated by C. Gilmour (Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia). It was repurified similarly. The cultures were maintained on medium C of Postgate (21) but were pregrown for experiments in medium D (21) modified by omitting FeSO4. Incubation was at 37°C under oxygen-free 100% N2 with slow shaking. After 24 h, 20-ml suspensions in 50-ml serum bottles were centrifuged at 3,200 × g to pellet the cells. The modified medium D was removed from the inverted bottles with a syringe and replaced by 10 ml of a specially formulated coculture medium. This medium contained (per liter) 0.33 g of KCl, 2.75 g of MgCl2 · 7H2O, 0.25 g of NH4Cl, 0.14 g of CaCl2 · 2H2O, 0.14 g of K2HPO4, 18 g of NaCl, 5 g of NaHCO3, 0.25 g of yeast extract, 0.25 g of cysteine, 1.0 g of resazurin, 0.1 g of sodium ascorbate, 0.1 g of thioglycolate, 6.0 g of sodium lactate, and the trace elements in ATCC medium 1043 (2) modified by replacing the ZnSO4 · 7H2O with 0.1 g of ZnCl2 per liter and adding 0.5 g of ferric ammonium citrate per liter. This coculture medium always contained a 1-μg/ml spike of HgCl2 and was routinely incubated at 37°C under 100% N2 with slow shaking. The D. desulfuricans cell pellets were suspended in 10 ml of this coculture medium with shaking, and 1-ml portions were used to inoculate replicate 50-ml bottles containing 19 ml of coculture medium.

Methanococcus maripaludis ATCC 43000 (2) was kindly provided by W. B. Whitman, University of Georgia, Athens. It was maintained and pregrown for experiments in ATCC medium 1439 (2) under 80% H2–20% CO2 with slow shaking at 37°C. After 24 h, the cells were pelleted and ATCC medium 1439 was replaced with 10 ml of coculture medium, as described above for D. desulfuricans LS. One-milliliter portions of the resuspended cells were used to inoculate a series of 50-ml bottles containing 19 ml of coculture medium. In addition, a series of bottles containing 18 ml of coculture medium were each inoculated with 1 ml of D. desulfuricans and 1 ml of M. maripaludis. All of the bottles were incubated at 37°C under 100% N2 with slow shaking. At appropriate times, bottles were removed from the incubator, 2.0 ml of a 1.0 M CuSO4 solution was added to each bottle to stop the reaction, and the vials were kept at −20°C until analysis.

For experiments performed with resting cells, the D. desulfuricans strains were pregrown in modified (sulfate-free) medium D (21) as described above for the coculture experiments. The cells were sedimented in the serum bottles by centrifugation, washed once with coculture medium, and suspended to the original volume in coculture medium containing 1.0 μg of HgCl2 per ml.

Prior to analysis, the bottles were thawed and mixed by shaking. Five milliliters was removed from each of the bottles, and the cells were centrifuged and used for protein determination (17). The remaining 15 ml was analyzed for methylmercury by the procedure of Longbottom et al. (13) by using a Hewlett-Packard model 5890 gas chromatograph equipped with a macrobore capillary column (inside diameter, 0.53 mm; length, 15 m: type AT-35; Alltech, Deerfield, Ill.). The operating conditions were as follows: the carrier gas was Ar-CH4 (95:5, vol/vol; ultrapure grade; Matheson Gas Products, East Rutherford, N.J.) at a flow rate of 35 ml/min, the injector temperature was 150°C, and the electron capture detector temperature was 250°C. Monomethylmercury peak (retention time, 1.25 min) areas were recorded with a Hewlett-Packard model 3392A integrator that was calibrated by using monomethylmercury (CH3HgI) standards (American Tokyo Kasei, Inc., Portland, Oreg.). The detection limit for monomethylmercury was 1 ng/ml. The procedure of Longbottom et al. (13) analyzes all methylmercury as monomethylmercury, and the synthesis of CH3Hg2+ was plotted over time. In order to make comparisons between experiments easier, the rates of methylmercury synthesis were normalized to the initial protein concentrations of the inocula. The data for time points given below represent single determinations.

Methane determinations in the headspaces of bottles were made with a model 1200 gas partitioner (Fisher Co., Springfield, N.J.) operated at 50°C with helium as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 30 ml/min. The sample volume analyzed was 250 μl, and the instrument was calibrated with methane standards (Fisher). Microscopic observations were made with a Reichert Zetopan microscope at a magnification of ×1,000.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

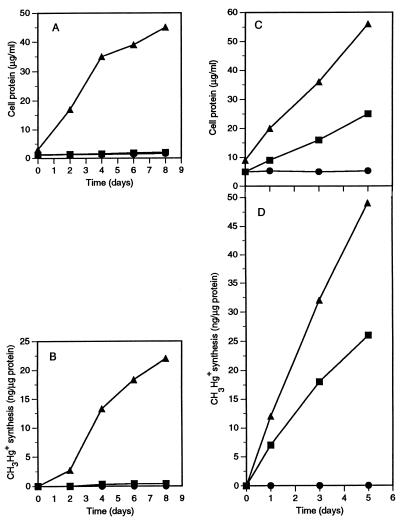

As shown in Fig. 1A, neither D. desulfuricans LS nor M. maripaludis was able to grow individually in the coculture medium, since the organic substrate (lactate) could be used only by the former bacterium and the electron acceptor (carbonate) could be used only by the latter bacterium. However, in the coculture of the two bacteria, the protein level increased 15-fold in 8 days, from 3 to 45 μg/ml.

FIG. 1.

(A and B) Protein contents of D. desulfuricans LS and M. maripaludis cultures and a coculture in lactate-carbonate coculture medium (A) and synthesis of CH3Hg+ (per microgram of initial protein) from a 1-μg/ml HgCl2 spike in the same experiment (B). (C) Protein contents of D. desulfuricans ND 132 and M. maripaludis cultures and a coculture in lactate-carbonate coculture medium (C) and synthesis of CH3Hg+ (per microgram of initial protein) from a 1-μg/ml HgCl2 spike in the same experiment (D). Symbols: ▪, D. desulfuricans culture; •, M. maripaludis culture; ▴, coculture.

The morphologies of the two bacteria are quite distinct. M. maripaludis cells are large cocci that are of 2 to 2.5 μm in diameter, while D. desulfuricans cells are motile curved rods that are 1.0 to 1.5 μm long. Microscopic observations of the coculture showed that the two types of cells multiplied proportionally and roughly equal numbers of the two types were produced (results not shown).

The methylmercury synthesis pattern was similar to the protein production pattern (Fig. 1B). M. maripaludis alone failed to form any methylmercury, and D. desulfuricans LS alone formed only a trace amount, but the coculture synthesized 22 ng of methylmercury per μg of initial protein in 8 days, methylating 2.6% of the available Hg2+. This rate was very similar to the rate of synthesis of methylmercury by D. desulfuricans LS in a sulfate-free pyruvate medium in which this sulfidogen can grow fermentatively without an electron acceptor (6, 19, 21). In this medium the typical D. desulfuricans LS protein yield was 30 μg/ml. M. maripaludis was unable to synthesize any methylmercury even in a complete methanogen medium (2) in which the typical M. maripaludis protein yield is 38 μg/ml (19).

The coculture experiment was also performed with D. desulfuricans ND 132, and the results were only slightly different. This strain was selected for its exceptional ability to methylate mercury. It also appeared to have a limited ability to use lactate fermentatively in the absence of sulfate or to grow on the amino acids in yeast extract, since the protein concentration of the D. desulfuricans ND 132 culture approximately doubled (Fig. 1C). As in the experiment described above, the protein concentration in the coculture increased to about 50 μg/ml. The coculture methylated large amounts of mercury, but, in contrast to D. desulfuricans LS, D. desulfuricans ND 132 alone methylated as much as two-thirds of the mercury methylated by the coculture (Fig. 1D). These experiments were repeated several times to ascertain that the difference observed was strain specific and reproducible.

D. desulfuricans LS and ND-132 belong to the “incomplete oxidizer” subgroup of sulfidogens (21, 25). In the presence of sulfate, they oxidize lactate to pyruvate, and the latter yields CO2, acetate, and reducing equivalents for SO42− reduction. D. desulfuricans strains are unable to use acetate (6), but M. maripaludis, like many other methanogens, can use acetate as a substrate for methanogenesis and growth (2). Thus, D. desulfuricans strains, in addition to transferring lactate hydrogens to M. maripaludis for CO2 reduction, also benefited the methanogen by producing acetate as a methanogenic substrate. In turn, the removal of H2 and acetate by the methanogen allowed D. desulfuricans strains to utilize lactate even in the absence of SO42−.

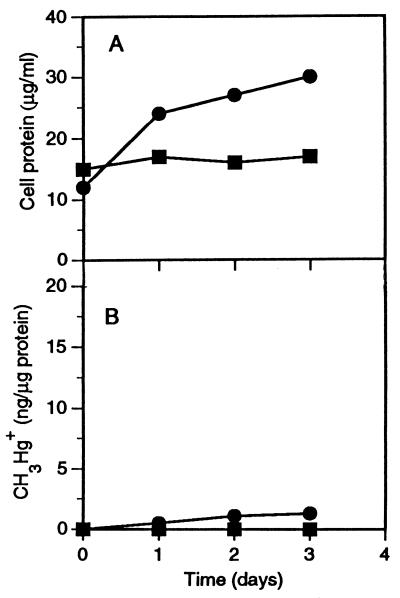

The experiments described above were performed with a 5% inoculum, and mercury methylation occurred during growth. To determine whether preformed D. desulfuricans biomass could methylate mercury under nongrowth conditions, we repeated the control experiments with the two D. desulfuricans strains in coculture medium but with a 100% inoculum. As shown in Fig. 2, D. desulfuricans LS failed to grow or to form any methylmercury under these conditions. The protein content of D. desulfuricans ND 132, which showed a limited ability to grow in the absence of sulfate, doubled, but this organism synthesized only a trace amount of methylmercury. It may be concluded that growth conditions are necessary for mercury methylation.

FIG. 2.

(A) Protein contents of D. desulfuricans LS and D. desulfuricans ND 132 cultures in lactate-carbonate coculture medium without M. maripaludis. (B) Synthesis of CH3Hg+ (per microgram of initial protein) from a 1-μg/ml HgCl2 spike in the same experiment. Note the large inoculum and essentially nongrowth conditions. Symbols: ▪, D. desulfuricans LS culture; •, D. desulfuricans ND 132 culture.

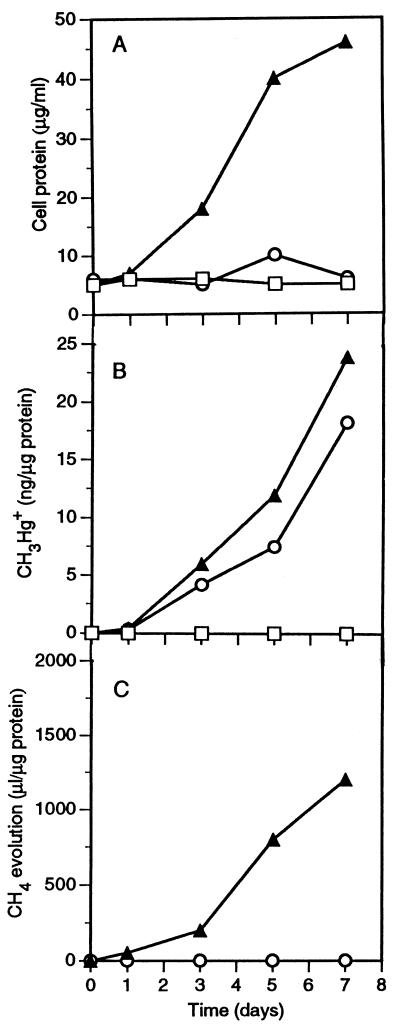

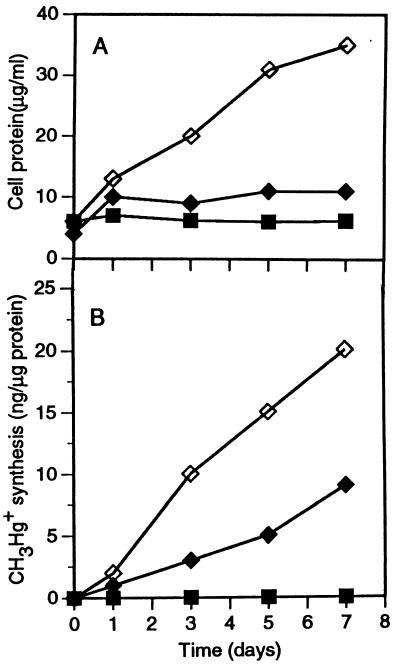

The effects of selective inhibitors of methanogenesis and sulfate reduction (18) on the coculture of D. desulfuricans LS and M. maripaludis are shown in Fig. 3. Bromoethanesulfonic acid (BESA) at a concentration of 0.5 mM allowed only marginal protein synthesis by the coculture (Fig. 3A), but it allowed almost normal mercury methylation by the coculture (Fig. 3B). Molybdate (2 mM) prevented both growth of and mercury methylation by the coculture (Fig. 3A and B). The methylation of mercury observed in the BESA-inhibited coculture was unexpected, since M. maripaludis was completely inhibited by 0.2 mM BESA when it was grown alone in methanogen medium (results not shown). A possible explanation for this apparent paradox is that under sulfate-limited conditions, some sulfidogens are capable of using BESA as alternate electron acceptor (18), making cooperation with the methanogen unnecessary. That M. maripaludis was in fact inhibited by BESA in the coculture was evident from the effect of BESA on methanogenesis (Fig. 3C). Methane evolution was completely suppressed by the inhibitor, while in 7 days the control coculture produced 1,200 μl of methane per μg of initial protein in the inoculum. The results of an experiment to determine whether BESA in fact serves as an electron acceptor for D. desulfuricans LS are shown in Fig. 4. Inoculated alone into coculture medium, this strain failed to grow or to methylate mercury. In the presence of BESA, however, it methylated one-half as much mercury as it methylated when it was grown fermentatively on pyruvate without an electron acceptor. However, the rate of protein synthesis was low when BESA served as an electron acceptor compared to the rate when the organism was grown in medium D. D. desulfuricans ND 132 behaved in a similar manner (results not shown).

FIG. 3.

(A) Protein contents of a D. desulfuricans LS-M. maripaludis coculture in lactate-carbonate coculture medium, in coculture medium containing 0.5 mM BESA, and in coculture medium containing 2.0 mM molybdate. (B) Synthesis of CH3Hg+ (per microgram of initial protein) in the same experiment. (C) Evolution of CH4 (per microgram of initial protein) in the same experiment. Symbols: ▴, coculture medium; ○, coculture medium containing 0.5 mM BESA; □, coculture medium containing 2.0 mM molybdate.

FIG. 4.

(A) Protein contents of D. desulfuricans LS cultures inoculated into lactate-carbonate coculture medium with and without 0.5 mM BESA as the electron acceptor. The protein content of a culture in low-sulfate pyruvate medium D served as a positive control. (B) Synthesis of CH3Hg+ (per microgram of initial protein) in the same experiment. Symbols: ⧫, coculture medium containing 0.5 mM BESA; ▪, coculture medium not containing BESA; ◊, medium D.

The utilization of BESA as an alternate electron acceptor by sulfidogens presents a future methodological challenge for demonstrating interspecies electron transfer-mediated mercury methylation in sulfate-limited sediments. A straightforward approach would be to inhibit methanogens in such sediments by using BESA, expecting this to inhibit mercury methylation. However, since BESA serves as an alternate electron acceptor for sulfidogens, mercury methylation is likely to remain unaffected, even when the methanogens are inhibited.

In anoxic sediments, the microbial community preferentially uses the electron acceptor that maximizes the energy yield from the available electron donors (3). Thus, there is usually little methanogenesis from substrates utilizable by both groups until sulfate becomes limiting to sulfidogenic activity. There is no agreement in the literature concerning the sulfate concentration at which sulfate becomes limiting for the activity of sulfate reducers. On the high end, Ingvorsen et al. (10) described 300 μM as the limiting concentration, while other workers (16, 22, 24) have claimed that levels as low as 20 to 30 μM are limiting. Several authors have reported values between these extremes (23, 27). The way that sulfate reduction is measured (i.e., by spiking sediments with 35SO42−) is relevant to this controversy. In sulfate-rich marine and estuarine sediments, the spike adds an insignificant amount to the total sulfate concentration, but when the sulfate concentration is near the limiting concentration, the spike can significantly alter the sulfate pool (11). If this is the case, the measurement does not reflect the in situ rate accurately but instead gives a value between the actual in situ rate and the in situ potential. In addition to this methodological difficulty, obviously the quantity and quality of the available organic substrates, the temperature, the pH, and other environmental factors may influence the sulfate concentration at which sulfate becomes limiting.

Regardless of the exact inhibitory limit, it may be assumed that at least partial sulfate limitation occurs when anoxic sediments evolve methane vigorously, indicating that much of the energy flow passes through the methanogens. This is typical of many oligotrophic freshwater lakes. Most methanogens can use CO2 as an electron acceptor, but their substrate ranges are extremely limited and they have higher Ks values for H2 and acetate than sulfidogens have (12, 14–16, 27). In sulfate-limited situations, sulfidogens may still have primary access to the organic substrates but can gain energy from them only by passing on hydrogen and acetate to methanogens and in this manner utilize the only remaining electron sink (CO2). Such interspecies hydrogen transfer has been demonstrated previously in several sulfidogen-methanogen cocultures (1, 5, 20). Our contribution explores the potential significance of this phenomenon with respect to mercury methylation.

Hg2+ is methylated principally by sulfidogens (6), yet at sulfate levels above 200 μM the product of the normal metabolism of these organisms (H2S) inhibits mercury methylation (4, 7, 9). Therefore, situations that allow sulfidogens to be active without sulfate reduction are very favorable for Hg2+ methylation. One such situation is the growth of sulfidogens on a fermentable substrate like pyruvate (6, 21). Another one, which has potentially broader ecological and environmental significance, may be the interspecies transfer of hydrogen and acetate from sulfidogens to methanogens.

We do not wish to imply that interspecies hydrogen transfer is an exclusive mechanism for Hg2+ methylation; it merely represents a very favorable opportunity. It has been demonstrated that at concentrations just above the limiting concentration, sulfate additions to a lake sediment increase Hg2+ methylation (9). However, at SO42− concentrations of more than 200 μM, accumulating H2S apparently starts to interfere with CH3Hg+ synthesis. As the window for sulfate-reducing activity without inhibition of Hg2+ methylation by H2S seems to be narrow, there is reason to believe that Hg2+ methylation via interspecies hydrogen and acetate transfer has environmental significance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant 14-08-0000162034 from the U.S. Geological Survey and by New Jersey state funds.

Footnotes

New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station Publication no. D-01408-02-97.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abram J W, Nedwell D B. Inhibition of methanogenesis by sulphate reducing bacteria competing for transferred hydrogen. Arch Microbiol. 1978;117:89–92. doi: 10.1007/BF00689356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Type Culture Collection. Catalogue of bacteria and bacteriophages. 19th ed. 1996. p. 212. and 538. American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atlas R M, Bartha R. Microbial ecology: fundamentals and applications. 3rd ed. Redwood City, Calif: Benjamin Cummings; 1993. pp. 338–341. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blum J, Bartha R. Effect of salinity on the methylation of mercury. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1980;25:404–408. doi: 10.1007/BF01985546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryant M P, Campbell L L, Reddy C A, Crabill M R. Growth of Desulfovibrio in lactate or ethanol media low in sulfate in association with H2-utilizing methanogenic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1977;33:1162–1169. doi: 10.1128/aem.33.5.1162-1169.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Compeau G C, Bartha R. Sulfate-reducing bacteria: principal methylators of mercury in anoxic estuarine sediment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;50:498–502. doi: 10.1128/aem.50.2.498-502.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Compeau G C, Bartha R. Effect of salinity on mercury-methylating activity of sulfate-reducing bacteria in estuarine sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:261–265. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.2.261-265.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilmour C C, Henry E A. Mercury methylation in aquatic systems affected by acid deposition. Environ Pollut Ser B. 1991;71:131–169. doi: 10.1016/0269-7491(91)90031-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilmour C C, Henry E A, Mitchell R. Sulfate stimulation of mercury methylation in freshwater sediments. Environ Sci Technol. 1992;26:2281–2287. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ingvorsen R, Zehnder A J B, Jorgensen B B. Kinetics of sulfate and acetate uptake by Desulfobacter posgatei. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;47:403–408. doi: 10.1128/aem.47.2.403-408.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly C A, Rudd J W M. Epilimnetic sulfate reduction and its relationship to lake acidification. Biogeochemistry. 1984;1:63–77. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kristjansson J K, Schonheit P, Thauer R K. Different Ks values for hydrogen of methanogenic bacteria and sulfate reducing bacteria: an explanation for the apparent inhibition of methanogenesis by sulfate. Arch Microbiol. 1982;131:278–282. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Longbottom J E, Dressman R C, Lichtenberg J J. Metals and other elements: gas chromatographic determination of methylmercury in fish, sediment, and water. J Assoc Off Anal Chem. 1973;56:1297–1303. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lovley D R. Minimum threshold for hydrogen metabolism in methanogenic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;49:1530–1531. doi: 10.1128/aem.49.6.1530-1531.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lovley D R, Dwyer D F, Klug M J. Kinetic analysis of competition between sulfate reduction and methanogens for hydrogen in sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;43:1371–1379. doi: 10.1128/aem.43.6.1373-1379.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lovley D R, Klug M J. Sulfate reducers can outcompete methanogens at freshwater sulfate concentrations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;45:187–192. doi: 10.1128/aem.45.1.187-192.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oremland R S, Capone D G. Use of “specific” inhibitors in biogeochemistry and microbial ecology. Adv Microb Ecol. 1988;10:285–383. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pak K-R, Bartha R. Mercury methylation and demethylation in anoxic lake sediments and by strictly anaerobic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1013–1017. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.3.1013-1017.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phelps T J, Conrad R, Zeikus J G. Sulfate-dependent interspecies H2 transfer between Methanosarcina barkeri and Desulfovibrio vulgaris during coculture metabolism of acetate or methanol. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;50:589–594. doi: 10.1128/aem.50.3.589-594.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Postgate J R. The sulfate-reducing bacteria. 2nd ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1984. pp. 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roden E E, Tuttle J H. Inorganic sulfur turnover in oligohaline estuarine sediments. Biogeochemistry. 1993;22:81–105. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schonheit P, Kristjansson J K, Thauer R K. Kinetic mechanism for the ability of sulfate reducers to out-compete methanogens for acetate. Arch Microbiol. 1982;132:285–288. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urban N R, Brezonik P L, Baker L A, Sherman L A. Sulfate reduction and diffusion in sediments of Little Rock Lake, WI. Limnol Oceangr. 1994;39:797–815. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Widdel F. Microbiology and ecology of sulfate and sulfur-reducing bacteria. In: Zehnder A J B, editor. Biology of anaerobic microorganisms. New York, N.Y: Wiley; 1988. pp. 469–585. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winfrey M R, Rudd J W M. Environmental factors affecting the formation of methylmercury in low pH lakes. Environ Toxicol Chem. 1990;9:853–869. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winfrey M R, Zeikus J G. Effect of sulfate on carbon and electron flow during microbial methanogenesis in freshwater sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1977;33:275–281. doi: 10.1128/aem.33.2.275-281.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]