Abstract

Background

Longitudinal cohort data of patients with tuberculosis (TB) and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) are lacking. In our global study, we describe long-term outcomes of patients affected by TB and COVID-19.

Methods

We collected data from 174 centres in 31 countries on all patients affected by COVID-19 and TB between 1 March 2020 and 30 September 2022. Patients were followed-up until cure, death or end of cohort time. All patients had TB and COVID-19; for analysis purposes, deaths were attributed to TB, COVID-19 or both. Survival analysis was performed using Cox proportional risk-regression models, and the log-rank test was used to compare survival and mortality attributed to TB, COVID-19 or both.

Results

Overall, 788 patients with COVID-19 and TB (active or sequelae) were recruited from 31 countries, and 10.8% (n=85) died during the observation period. Survival was significantly lower among patients whose death was attributed to TB and COVID-19 versus those dying because of either TB or COVID-19 alone (p<0.001). Significant adjusted risk factors for TB mortality were higher age (hazard ratio (HR) 1.05, 95% CI 1.03–1.07), HIV infection (HR 2.29, 95% CI 1.02–5.16) and invasive ventilation (HR 4.28, 95% CI 2.34–7.83). For COVID-19 mortality, the adjusted risks were higher age (HR 1.03, 95% CI 1.02–1.04), male sex (HR 2.21, 95% CI 1.24–3.91), oxygen requirement (HR 7.93, 95% CI 3.44–18.26) and invasive ventilation (HR 2.19, 95% CI 1.36–3.53).

Conclusions

In our global cohort, death was the outcome in >10% of patients with TB and COVID-19. A range of demographic and clinical predictors are associated with adverse outcomes.

Tweetable abstract

In 778 TB/COVID-19 co-infected patients, 77% TB treatment success and 11% TB mortality was observed, with 71% recovering from COVID-19 and 13% COVID-19-associated mortality. Mortality was higher in those diagnosed with COVID-19 before/during TB treatment. https://bit.ly/3PQSw17

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has significantly affected tuberculosis (TB) services worldwide [1]. Globally, national TB programmes struggled to provide care, resulting in an unprecedented interruption of essential services. Studies have demonstrated that access to TB care has worsened during the pandemic [2–6]. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported an overall decrease in TB notifications, from 7.1 million in 2019 to 5.8 million in 2020, with a partial recovery in 2021, and an additional 100 000 TB deaths between 2019 and 2020 [1].

Since the beginning of the pandemic, TB and COVID-19 co-infected cases have been described: they can occur concomitantly, or COVID-19 can precede TB or occur in patients with TB sequelae. Both diseases primarily affect the lungs and share similar symptoms, such as fever and cough, posing diagnostic challenges and delayed diagnosis [7]. COVID-19 and TB co-infection may lead to severe acute illness [8–11]. Studies have demonstrated that concomitant TB and COVID-19 increase mortality and chronic lung sequelae [12, 13].

Despite studies suggesting synergistic amplification of mortality related to co-infection, no cohort studies have evaluated the effects of COVID-19 on long-term TB outcomes or vice versa, particularly since TB treatment outcomes were generally not reported in previous publications [9, 10, 14]. The first published report from the Global TB–COVID-19 cohort did not provide final TB outcomes, because many patients were still undergoing anti-TB treatment [10]. The objectives of this study were to evaluate the long-term outcomes and risk factors for the mortality of TB–COVID-19 patients in a global cohort.

Methods

We conducted a prospective, multicountry study. In collaboration with the WHO, invitations were sent to 174 centres in 31 countries from all continents [10]. The centres and countries providing data are listed in figure 1 and the supplementary material. Patients of any age, with either active or previous TB disease and COVID-19 were enrolled from 1 March 2020 and followed up until 30 September 2022. Both hospitalised and community-treated patients were included. All TB patients were included at the time of COVID-19 diagnosis and COVID-19 patients were included when TB diagnosis was made. TB and COVID-19 case definitions follow WHO classification [1, 15]. We define previous TB patients as those who had TB and completed anti-TB treatment at any time in the past before the diagnosis of COVID-19. The coordinating centre (Istituti Clinici Scientifici Maugeri, Tradate, Italy) and the participating clinics had ethics clearance in accordance with their institutional regulations.

FIGURE 1.

Global distribution of the countries/states/regions participating in the study. The following states/territories are covered in the study update: Australia (New South Wales); Canada (Ontario state); China (Wenzhou and Luzhou regions); India (New Delhi, Mumbai and Maharashtra states); Russian Federation (Arkhangelsk, Moscow and Volvograd oblasts); Switzerland (Vaud county); USA (Virginia state). 29 out of 34 countries participating in the first global study [10] provided treatment outcome updates and two countries (Nigeria and Libya) were enrolled in the study at a later stage, providing data with treatment outcomes.

Clinical data were collected via a standardised electronic form. Previously validated WHO TB outcomes were used [1]. The causes of death were attributed to TB; to TB+COVID-19; to TB+COVID-19+other cause; to COVID-19; or any other cause. COVID-19 outcomes were categorised as recovery; non-recovery (e.g. patients still in the acute phase or still with a positive test and/or symptoms); or death [16]. Recovered cases were stratified as discharged; never hospitalised for COVID-19; hospitalised for reasons other than TB and/or COVID-19; or unknown hospitalisation (e.g. when it is not known whether the patient was hospitalised or not). Non-recovered cases were subcategorised as discharged; never hospitalised for COVID-19; diagnosis during hospitalisation for other reasons; still hospitalised for COVID-19 non-recovered; or unknown hospitalisation.

The proportions of death from TB, from COVID-19 and for any reason were calculated by geographical regions as follows: Latin America (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Honduras, Mexico, Paraguay and Peru); North America, Western and Central Europe plus Oman in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (Canada, France, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Oman, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Spain, Switzerland, UK and USA); Eastern Europe (Belarus and Russian Federation); Africa (Guinea, Libya, Nigeria and South Africa); and Asia (China, India and Singapore).

Geographic groupings were chosen with consideration for epidemiological similarities, as validated in the previous study of the Global TB–COVID-19 cohort [1, 10].

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 22.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Data were presented as number of cases, mean±sd or median and interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed data. Categorical comparisons were performed by Chi-squared test using Yates's correction, or Fisher's exact test. Continuous variables were compared using the t-test or Wilcoxon test. Kaplan–Meier curves were used for cumulative survival analyses, and the log-rank test was used to compare the survival of TB, COVID-19 and TB+COVID-19. Survival analysis was performed using Cox proportional risk-regression models: 1) events were defined as death from TB or COVID-19; 2) we censored data if no events occurred at the end of the follow-up period (30 September 2022). All statistically significant variables in the univariate analysis were selected to be included in the Cox regression. We did a stepwise variable selection procedure in order to find the best model. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals are presented. A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered significant for all analyses.

Results

Overall, 788 patients with TB and COVID-19 were enrolled from 31 countries; 29 of the 34 countries which participated in the first global treatment outcome study provided updates and two additional countries were included (Libya and Nigeria; suplementary material). The mean±sd age was 45.5±18.3 years; 533 (67.8%) patients were male; 83 (10.7%) were HIV co-infected; and 80 (11.9%) had drug-resistant TB. 303 (38.5%) patients needed hospitalisation due to TB and 349 (44.3%) due to COVID-19; 16 (2.0%) patients needed mechanical ventilation due to TB and 35 (4.4%) due to COVID-19; 87 (11.0%) patients needed supplemental oxygen due to TB and 151 (19.2%) due to COVID-19.

Out of 788 patients, information on the time of TB and COVID-19 diagnosis was available in 777 (98.6%) (table 1). For 282 (36.3%) out of 777 patients, the diagnosis of COVID-19 followed the end of TB treatment. Of them, 204 (72.3%) had completed TB treatment >1 year earlier (range 1–79 years), while for the remaining 78 (27.7%) patients the median (IQR) time from the end of TB treatment to COVID-19 diagnosis was 5 (3–8) months.

TABLE 1.

Summary of anti-tuberculosis (TB) treatment outcomes in 788 patients, stratified by time of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) diagnosis after the end of TB treatment versus before or during TB treatment

| TB patients | COVID-19 diagnosis# | p-value | ||

| After the end of TB treatment | Before or during TB treatment | |||

| Cured | 284 (36) | 109 (38.7) | 172 (34.7) | 0.311 |

| Treatment completed | 324 (41.1) | 147 (52.1) | 173 (34.9) | <0.0001 |

| Treatment successful | 608 (77.2) | 256 (90.8) | 345 (69.7) | <0.0001¶ |

| Died | 85 (10.8) | 83 (16.8) | ||

| Cause of death | ||||

| TB | 17/85 (20) | 15/83 (18.1) | ||

| TB+COVID-19 | 46/85 (54.1) | 46/83 (55.4) | ||

| TB+COVID-19+other | 4/85 (4.7) | 4/83 (4.87) | ||

| COVID-19 | 9/85 (10.6) | 9/83 (10.8) | ||

| Other | 9/85 (10.6) | 9/83 (10.8) | ||

| Failure | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | 0.620 |

| Lost to follow-up | 92 (11.7) | 25 (8.9) | 65 (13.1) | 0.094 |

| Total | 788 | 282/777 | 495/777 | |

Data are presented as n (%), n/N (%) or n, unless otherwise stated. #: for 11 out of 788 patients, data were unavailable on timing of COVID-19 diagnosis in relation to TB treatment; ¶: baseline TB treatment success was significantly higher when the diagnosis of COVID-19 occurred after the end of TB treatment (90.8%), in comparison with cases where the diagnosis was made before or during TB treatment (69.7%) (p<0.0001).

Among the 495 patients who had COVID-19 diagnosed before or during TB treatment, 125 (25.3%) had both diseases diagnosed within the same week; 296 (59.8%) had COVID-19 diagnosed before the start of TB treatment (median 3 months, IQR 1.4–4.9 months) and 74 (14.9%) had COVID-19 diagnosed during TB treatment (median time from TB treatment start 1.1 months, IQR 0.5–1.6 months).

TB and COVID-19 outcomes are shown in relation to COVID-19 diagnosis (if COVID-19 diagnosis was after the end of anti-TB treatment, or before or during anti-TB treatment) in tables 1 and 2. TB outcomes were available for all patients (table 1) and COVID-19 outcomes were available for 778 patients (table 2).

TABLE 2.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outcomes (known in 778 patients) stratified by time of COVID-19 diagnosis (after the end of anti- tuberculosis (TB) treatment versus before or during anti-TB treatment)

| COVID-19 patients | COVID-19 diagnosis# | p-value | ||

| After the end of TB treatment | Before or during TB treatment | |||

| Recovered | 551 (70.8) | 166 (60.1) | 377 (76.3) | <0.0001 |

| Discharged | 261 (47.4) | 77 (46.4) | 183 (48.5) | |

| Never hospitalised for COVID-19 | 164 (29.8) | 49 (29.5) | 108 (28.6) | |

| Diagnosis during hospitalisation for other reasons | 74 (13.4) | 3 (1.8) | 71 (18.8) | |

| Unknown hospitalisation | 52 (9.4) | 37 (22.3) | 15 (4.0) | |

| Non-recovered | 125 (16.1) | 74 (26.8) | 51 (10.3) | <0.0001 |

| Discharged¶ | 24 (19.2) | 20 (27.0) | 4 (7.8) | |

| Never hospitalised for COVID-19 | 10 (8.0) | 3 (4.1) | 7 (13.7) | |

| Diagnosis during hospitalisation for other reasons | 2 (1.6) | 2 (3.9) | ||

| Still hospitalised for COVID-19 | 4 (3.2) | 1 (1.4) | 3 (5.9) | |

| Unknown hospitalisation | 85 (68.0) | 50 (67.6) | 35 (68.6) | |

| Cause of death | 102 (13.1) | 36 (13.0) | 66 (13.4) | 0.980 |

| TB | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.5) | ||

| TB+COVID-19 | 46 (45.1) | 46 (69.7) | ||

| TB+COVID-19+other | 4 (3.9) | 4 (6.1) | ||

| COVID-19 | 38 (37.3) | 29 (80.6) | 9 (13.6) | |

| COVID-19+other | 6 (5.9) | 6 (16.7) | ||

| Other | 7 (6.9) | 1 (2.8) | 6 (9.1) | |

| Total+ | 778/788 | 276/770 | 494/770 | |

Data are presented as n (%) or n/N, unless otherwise stated. #: for eight out of 778 patients, data were unavailable on timing of COVID-19 diagnosis in relation to TB treatment; ¶: one patient with voluntary discharge; +: 10 patients had unknown COVID-19 outcomes.

Recovery from COVID-19 was more frequent when COVID-19 diagnosis was before or during TB treatment than when it was after the end of TB treatment (76.3% versus 60.1%; p<0.0001). Non-recovery of COVID-19 cases was higher among patients with COVID-19 diagnosis after the end of TB treatment (26.8%) than in those with COVID-19 diagnosis before or during TB treatment (10.3%) (p<0.0001).

The factors associated with TB mortality (table 3) in univariate analysis were older age (HR 1.04, 95% CI 1.03–1.04; p<0.0001), HIV infection (HR 2.92, 95% CI 1.65–5.18; p<0.0001), COPD (HR 2.66, 95% CI 1.39–5.06; p=0.004), diabetes mellitus (HR 2.25, 95% CI 1.37–3.67; p=0.002), renal failure (HR 3.26, 95% CI 1.64–6.45; p=0.001), liver disease (HR 2.31, 95% CI 1.17–4.58; p=0.025), supplemental oxygen needed during COVID-19 (HR 7.31, 95% CI 3.86–13.83; p<0.0001) and invasive ventilation (HR 7.02, 95% CI 3.52–13.99; p<0.0001). In Cox regression analysis, the variables independently associated with TB mortality were age (HR 1.05, 95% CI 1.03–1.07; p<0.0001), HIV infection (HR 2.29, 95% CI 1.02–5.16; p=0.044) and invasive ventilation (HR 4.28, 95% CI 2.34–7.83; p<0.0001).

TABLE 3.

Univariate analysis of factors associated with tuberculosis (TB) and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) mortality

| TB deaths | COVID-19 deaths | Overall deaths | |||||||

| Yes | No | p-value | Yes | No | p-value | Yes | No | p-value | |

| Age years | 57.0±18.9 | 44.1±17.8 | <0.0001 | 61.6±18.4 | 42.9±17.0 | <0.0001 | 60.2±18.3 | 42.8±17.0 | <0.0001 |

| Male | 63 (74.1) | 470 (67.0) | 0.232 | 78 (76.5) | 446 (66.2) | 0.050 | 91 (75.2) | 442 (66.5) | 0.074 |

| BCG vaccinated | 31 (93.9) | 290 (89.8) | 0.757 | 36 (92.3) | 285 (89.9) | 0.782 | 43 (93.5) | 278 (89.7) | 0.597 |

| Alcohol abuse | 14 (20.3) | 95 (14.9) | 0.315 | 13 (14.8) | 95 (15.5) | 0.976 | 15 (15.2) | 94 (15.5) | 0.999 |

| Active smoker | 18 (28.1) | 168 (28.1) | 0.999 | 21 (25.9) | 164 (28.4) | 0.744 | 23 (24.7) | 163 (28.6) | 0.513 |

| Intravenous drug user | 1 (1.5) | 6 (1.0) | 0.516 | 1 (1.1) | 6 (1.0) | 0.999 | 1 (1.0) | 6 (1.0) | 0.999 |

| HIV | 19 (22.9) | 64 (9.2) | <0.0001 | 16 (15.8) | 67 (10.1) | 0.116 | 21 (17.9) | 62 (9.4) | 0.010 |

| COPD | 14 (16.7) | 49 (7.0) | 0.004 | 16 (15.8) | 47 (7.0) | 0.004 | 20 (16.9) | 43 (6.4) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 28 (32.9) | 126 (17.9) | 0.002 | 36 (35.3) | 114 (16.9) | <0.0001 | 43 (35.5) | 111 (16.7) | <0.0001 |

| Renal failure | 13 (16.5) | 36 (5.7) | 0.001 | 20 (20.4) | 28 (4.7) | <0.0001 | 23 (20.5) | 26 (4.3) | <0.0001 |

| Liver disease | 12 (15.4) | 46 (7.3) | 0.025 | 11 (11.3) | 47 (7.8) | 0.331 | 14 (12.6) | 44 (7.4) | 0.096 |

| Pulmonary TB | 76 (89.4) | 579 (83.3) | 0.197 | 87 (87.0) | 558 (83.3) | 0.427 | 104 (87.4) | 551 (83.4) | 0.332 |

| Extrapulmonary TB | 20 (25.0) | 188 (27.4) | 0.751 | 23 (24.5) | 184 (27.8) | 0.586 | 27 (24.5) | 181 (27.5) | 0.589 |

| Drug-resistant TB# | 11 (17.5) | 69 (11.3) | 0.216 | ||||||

| COVID-19 signs and symptoms | 89 (93.7) | 465 (78.0) | 0.001 | 104 (94.5) | 452 (77.5) | <0.0001 | |||

| Supplemental oxygen during COVID-19 | 40 (74.1) | 147 (28.1) | <0.0001 | 70 (88.6) | 117 (23.5) | <0.0001 | 72 (81.8) | 115 (23.5) | <0.0001 |

| Invasive ventilation | 16 (27.6) | 28 (5.1) | <0.0001 | 32 (40.0) | 12 (2.3) | <0.0001 | 32 (34.8) | 12 (2.4) | <0.0001 |

| Antivirals | 8 (14.0) | 54 (21.3) | 0.288 | ||||||

| Immunomodulators | 2 (3.5) | 3 (1.2) | 0.229 | ||||||

Data are presented as mean±sd or n (%), unless otherwise stated. BCG: bacille Calmette–Guérin. #: even analysing only patients with active TB, there was no difference between groups (11 (16.2%) died versus 59 (14.6%) who did not die; p=0.885).

Risk factors associated with COVID-19 mortality (table 3) in univariate analysis were older age (HR 1.03, 95% CI 1.02–1.04; p<0.0001), male sex (HR 1.66, 95% CI 1.02–2.69; p=0.050), COPD (HR 2.51, 95% CI 1.36–4.63; p=0.004), diabetes mellitus (HR 2.68, 95% CI 1.71–4.22; p<0.0001), renal failure (HR 5.26, 95% CI 2.83–9.78; p<0.0001), having COVID-19 signs and symptoms (HR 4.18, 95% CI 1.79–9.77; p=0.001), supplemental oxygen needed during COVID-19 (HR 25.33, 95% CI 12.28–52.26; p<0.0001) and invasive ventilation (HR 28.28, 95% CI 13.68–58.47; p<0.0001). In Cox regression analysis, the factors independently associated with COVID-19 mortality were age (HR 1.03, 95% CI 1.02–1.04; p<0.0001), male sex (HR 2.21, 95% CI 1.24–3.91; p=0.007), supplemental oxygen needed during COVID-19 (HR 7.93, 95% CI 3.44–18.26; p<0.0001) and invasive ventilation (HR 2.19, 95% CI 1.36–3.53; p=0.001).

The factors associated with overall mortality (table 3) in the univariate analysis were older age (HR 1.03, 95% CI 1.02–1.03; p<0.0001), HIV infection (HR 2.06, 95% CI 1.20–3.53; p=0.010), COPD (HR 2.89, 95% CI 1.64–5.12; p<0.0001), diabetes mellitus (HR 2.76, 95% CI 1.80–4.21; p<0.0001), renal failure (HR 5.54, 95% CI 3.03–10.13; p<0.0001), having COVID-19 signs and symptoms (HR 5.02, 95% CI 2.16–11.70; p<0.0001), supplemental oxygen needed during COVID-19 (HR 14.64, 95% CI 8.19–26.16; p<0.0001) and invasive ventilation (HR 22.13, 95% CI 10.82–45.27; p<0.0001). In the Cox regression analysis, the factors independently associated with overall mortality were age (HR 1.03, 95% CI 1.02–1.05; p<0.0001), supplemental oxygen needed during COVID-19 (HR 3.77, 95% CI 1.98–7.17; p<0.0001) and invasive ventilation (HR 2.28, 95% CI 1.39–3.72; p=0.001).

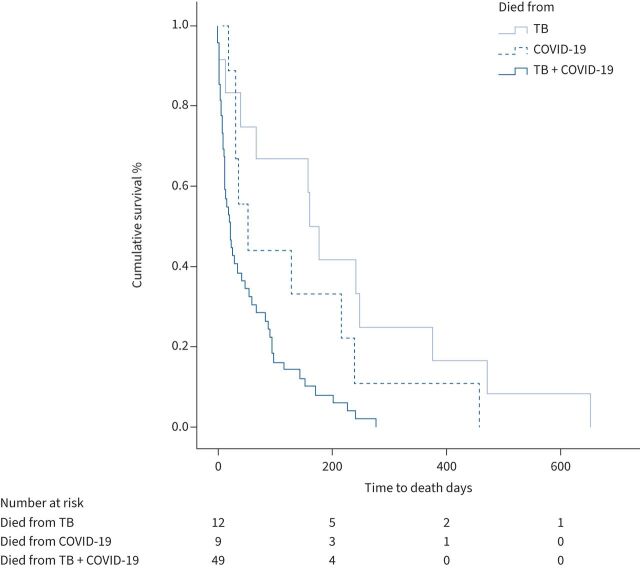

Figure 2 shows the comparison of Kaplan–Meier survival curves of patients whose death was attributed to TB alone (median time to death 168.0 days, IQR 45.3–342.8 days), COVID-19 alone (median time to death 52.0 days, IQR 30.5–227.5 days) or a combination of TB and COVID-19 (median time to death 21.0 days, IQR 8.0–90.0 days). The log-rank test for the comparison of the three groups was statistically significant (p=0.001).

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves of tuberculosis (TB) deaths, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) deaths and TB+COVID-19 deaths. Log-rank test: p=0.001.

In total, 341 patients from Latin America, 289 from North America, Western Europe and the Middle East, 59 from Eastern Europe, 35 from Africa and 64 from Asia were included. Table 4 shows patient characteristics according to the geographical region. Patients from North America, Western Europe and the Middle East were older, had a lower percentage of HIV and invasive ventilation and a higher rate of hospitalisation. Latin America had a higher percentage of HIV, and lower percentages of drug-resistant TB and hospitalised patients. Asia had higher percentage of males, drug-resistant TB and hospitalised patients, and lower percentages of HIV and use of supplemental oxygen during COVID-19. Africa had a lower percentage of hospitalised patients.

TABLE 4.

Deaths from tuberculosis (TB), coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and deaths for any reason (overall deaths) according to the geographical region

| Latin America | North America, Western Europe and the Middle East | Eastern Europe | Africa | Asia | p-value | |

| Age years | 41.7±17.7 | 51.7±18.8 | 44.6±16.1 | 42.5±16.1 | 39.8±14.4 | <0.0001 |

| Male | 224 (66.1) | 193 (66.8) | 43 (72.9) | 20 (57.1) | 53 (82.8) | 0.045 |

| HIV | 55 (16.6) | 15 (5.2) | 9 (15.3) | 4 (12.1) | 0 | <0.0001 |

| Drug-resistant TB | 17 (5.3) | 22 (9.8) | 27 (45.8) | 2 (8.7) | 12 (26.7) | <0.0001 |

| Hospitalised patients | 127 (37.2) | 226 (78.2) | 59 (100) | 11 (31.4) | 49 (76.6) | <0.0001 |

| Supplemental oxygen during COVID-19 | 67 (37.4) | 95 (35.7) | 9 (15.3) | 5 (55.6) | 11 (17.2) | <0.0001 |

| Invasive ventilation | 21 (11.7) | 13 (4.8) | 3 (5.2) | 0 | 7 (10.9) | 0.020 |

| Deaths from TB | 38 (11.1) | 38 (11.1) | 5 (8.5) | 7 (20.0) | 4 (6.3) | 0.112 |

| Deaths from COVID-19 | 43 (12.6) | 45 (15.9) | 4 (6.8) | 2 (6.3) | 8 (12.5) | 0.247 |

| Overall deaths | 51 (15.0) | 48 (16.6) | 7 (11.9) | 7 (20.0) | 8 (12.5) | 0.749 |

Data are presented as mean±sd or n (%), unless otherwise stated.

Discussion

In our global cohort, we evaluated death and other long-term outcomes of patients with TB and COVID-19. Among all included patients, we found a TB treatment success rate of 77.2%, and a 10.8% mortality. Conversely, most COVID-19 cases (70.8%) recovered, with 13.1% deaths. TB treatment success and completion of treatment was greater when the diagnosis of COVID-19 occurred after the end of TB treatment; that is, when the diagnosis of the two diseases was not concomitant. Conversely, most patients who died were in the group in which the COVID-19 diagnosis was before/during TB treatment, underscoring that concomitant TB and COVID-19 is associated with greater severity and worse outcomes and faster median time to death (figure 2). We have already shown that TB and COVID-19 co-infection may be associated with more severe clinical conditions than either disease alone [9, 10, 12] and with a T-cell impairment to in vitro response to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 [17, 18]. Boulle et al. [12] demonstrated that patients with TB and COVID-19 have a mortality risk up to 2.7 times higher compared to patients with COVID-19 without TB. Our mortality rate is similar to those found in our previous cohorts of patients co-infected with TB and COVID-19, of 11% [10] and 12.3% [9]. In addition, older age, male gender and invasive ventilation were also associated with COVID-19 mortality in other studies [9, 10, 19].

The risk factors for TB mortality found in the present report (i.e. older age, HIV infection and invasive ventilation) are similar to other studies [20–24]; however, our cohort provides more detailed description and quantification of risk. Müller et al. [20] reported that the mortality among TB patients was higher in older subjects, and in those with a high comorbidity index. In addition, HIV infection remains a major risk factor for TB mortality in our COVID-19 co-infected cohort [21, 22]. As expected, the likelihood that a person with TB would die was significantly higher if they needed invasive ventilation [24]. This illustrates the importance of early recognition and treatment of COVID-19 and TB, respectively, to avoid worsening of the condition of the patient, requiring the need for ventilation. Clinical risk scores, as developed and validated by several groups, may be usefully employed to identify those at higher risk of more severe disease and support early intervention to improve outcomes in future [19, 25].

A higher number of recovered cases of COVID-19 was recorded when COVID-19 diagnosis occurred before/during TB treatment; however, in almost 20% of patients the diagnosis emerged during hospitalisation for other reasons. These may have been mild or asymptomatic COVID-19 cases detected by increased systematic screening in this patient cohort, or possibly the result of hospital transmission [26]. It is likely that the outcomes seen in our cohort are at least in part explained by early oligosymptomatic COVID-19 cases, with a better prognosis in this group. Conversely, those who were diagnosed with COVID-19 after the end of TB treatment appeared to have a poorer prognosis with a higher number and proportion of “non-recovery” COVID-19 cases. This observation suggests that people with pre-existing lung disease due to TB have worse outcomes and might recover more slowly than those affected during acute illness. At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals faced a shortage of beds, with priority given to hospitalisation of critically ill patients [5, 6, 27]. Furthermore, we did not find statistically significant difference between patients who used and those who did not use antivirals and immunomodulators for COVID-19. In addition to the relatively small sample size, rifampicin, affecting most antivirals and Janus kinase inhibitors in a negative way, might potentially reduce the therapeutic effect of these drugs [7, 28].

Our longitudinal study reports on the early and medium-term TB- and COVID-19-related mortality observed in the cohort. There is recent evidence suggesting added mortality as an attributable consequence of post-TB lung disease. Even after treatment, the long-term mortality rate of TB patients is almost three times higher than in the general population, with deaths occurring mostly during the first year after the end of treatment [29]. Additionally, there are emerging reports [30, 31] suggesting that the increased COVID-19 mortality risk is not limited to the acute episode of COVID-19, but rather to post-COVID-19/long COVID processes [32–34] and that risk is closely linked to clinical risk and progression, including hospitalisation and intensive care. Mainous et al. [30] demonstrated that the 12-month adjusted all-cause mortality risk was significantly higher for patients with a COVID-19 hospitalisation, compared to mild COVID-19 and those without COVID-19. There is good evidence [33] that COVID-19 carries a substantially increased risk of death, which remains high over the year following the initial episode.

Considering that post-TB lung disease is identified in >50% of patients [32–36], and post-COVID-19 sequelae are thought to affect between 10% and 35% of COVID-19 survivors and up to 85% of those COVID-19 patients who required hospitalisation [37], it is extremely important to follow-up these patients in the long term, to establish strategies to avoid excess mortality associated with each of these two diseases and particularly with co-infection, and to define the need and plan for pulmonary rehabilitation, which appears to have emerging evidence in its support. TB should be considered prior to start or continuation of immunosuppressive medication, including high-dose corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive agents used in intensive care for severe COVID-19. When prioritising COVID-19 vaccination access, TB survivors should be included in at-risk populations, regardless of their age group.

Our study has some limitations. First, there were some missing data, as some centres were unable to provide all the requested information (e.g. on COVID-19 outcomes, date of COVID-19 diagnosis or causes of death other than TB and/or COVID-19). Approximately half of the countries (18 out of 34) provided representative data from their TB/COVID-19 cohorts; although large in sample size and having a global perspective, we cannot exclude that selection and/or survival bias exists, as the patients’ inclusion was not randomised. Second, the number of paediatric participants was limited, probably as a combined effect of the low prevalence of co-infection in children and of the predominance of adult-oriented TB services among participating centres (i.e. although they are open to patients of any age, children tend to report to paediatric services, not much represented in the cohort). Furthermore, in the analysis of mortality by region, we have low numbers from Asia and Africa, which might explain why no statistically significant difference have been found. We have not used the classification of countries as per WHO regions in order to support epidemiological similarities among groups, which may limit comparison with other published data.

Despite these concerns, we included a large dataset from all continents, which contains population-based data from more than half (although not from all) the countries/states/territories included in the study. The present report benefits from observation of longitudinal outcomes, and, to our knowledge, this is the largest study describing long-term outcomes of TB and COVID-19 co-infected patients.

In conclusion, death was reported as an outcome in >10% of patients co-infected with TB and COVID-19. A range of demographic and clinical predictors are associated with adverse outcomes, including age, clinical course including hospitalisation or invasive ventilation and immunosuppression. Some of these risk factors have been described previously, and our study quantifies this risk in a longitudinal study, to enable clinicians and policy-makers to improve care planning. Conversely, in our cohort, >70% of surviving patients had favourable outcomes (i.e. recovered COVID-19 and successful TB treatment). Future studies should evaluate the long-term pulmonary sequelae of these patients and elicit the effectiveness of and establish the need for pulmonary rehabilitation, as well as the protective role of anti-COVID-19 vaccination, and potentially of other available vaccines [38].

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material ERJ-00925-2023.Supplement (256.9KB, pdf)

Shareable PDF

Acknowledgements

The contributors of the Global Tuberculosis Network and TB/COVID-19 Global Study Group are: Nicolas Casco (Instituto de Tisioneumonología Prof. Dr R. Vaccarezza, Buenos Aires, Argentina); Alberto Levi Jorge (Instituto de Tisioneumonología Prof. Dr R. Vaccarezza, Buenos Aires, Argentina); Domingo Juan Palmero (Instituto de Tisioneumonología Prof. Dr R. Vaccarezza, Buenos Aires, Argentina); Jan-Willem Alffenaar (Sydney Institute for Infectious Diseases, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia; School of Pharmacy, The University of Sydney Faculty of Medicine and Health, Sydney, Australia; Westmead Hospital, Sydney, Australia); Greg J. Fox (Sydney School of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia); Wafaa Ezz (Sydney School of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia); Jin-Gun Cho (Parramatta Chest Clinic, Parramatta, Australia; Westmead Hospital, Westmead, Australia; Sydney Institute for Infectious Diseases, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia); Justin Denholm (Victorian Tuberculosis Program, Melbourne Health, Victoria, Australia; Department of Infectious Diseases at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia); Alena Skrahina (Republican Research and Practical Center for Pulmonology and Tuberculosis, Minsk, Belarus); Varvara Solodovnikova (Republican Research and Practical Center for Pulmonology and Tuberculosis, Minsk, Belarus); Marcos Abdo Arbex (Universidade de Araraquara, Faculdade de Medicina, Área temática de Pneumologia, Araraquara, Brazil); Tatiana Alves (Universidade Federal da Bahia, Salvador, Brazil); Marcelo Fouad Rabahi (Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, Brazil); Giovana Rodrigues Pereira (Laboratório Municipal de Alvorada, Secretaria Municipal de Saúde, Alvorada, Brazil); Roberta Sales (Divisao de Pneumologia, Instituo do Coracao, Hospital das Clinicas HCFMUSP, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil); Denise Rossato Silva (Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Porto Alegre, Brazil); Muntasir M. Saffie (Division of Respirology, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada); Nadia Escobar Salinas (Programa Nacional de Tuberculosis, Ministerio de Salud de Chile); Ruth Caamaño Miranda, Catalina Cisterna, Clorinda Concha, Israel Fernandez, Claudia Villalón, Carolina Guajardo Vera and Patricia Gallegos Tapia (Servicio de Salud Metropolitano Central, Chile); Viviana Cancino, Monica Carbonell, Arturo Cruz, Eduardo Muñoz, Camila Muñoz, Indira Navarro, Rolando Pizarro, Gloria Pereira Cristina Sánchez, Maria Soledad Vergara Riquelme, Evelyn Vilca and Aline Soto (Servicio de Salud Metropolitano Sur, Chile); Ximena Flores, Ana Garavagno, Martina Hartwig Bahamondes, Luis Moyano Merino, Ana María Pradenas, Macarena Espinoza Revillot and Patricia Rodriguez (Servicio de Salud Metropolitano Oriente, Chile); Angeles Serrano Salinas and Carolina Taiba (Servicio de Salud Metropolitano Occidente, Chile); Joaquín Farías Valdés (Servicio de Salud Iquique, Chile); Jorge Navarro Subiabre (Servicio de Salud Valparaíso San Antonio, Valparaíso, Chile); Carlos Ortega (Servicio de Salud Concepción, Chile); Sofia Palma (Hospital DIPRECA, Chile); Patricia Perez Castillo (Servicio de Salud Antofagasta, Chile); Mónica Pinto (Servicio de Salud Magallanes, Chile); Francisco Rivas Bidegain (Servicio de Salud Talcahuano, Chile); Margarita Venegas and Edith Yucra (Servicio de Salud Arica, Chile); Yang Li (Department of Infectious Diseases, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai China); Andres Cruz (Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Colombia); Beatriz Guelvez (Secretaria de Salud Departamental, Cauca, Colombia); Regina Victoria Plaza (Grupo de Investigación en Tuberculosis, Departamento de Medicina Interna, Universidad del Cauca, Popayán, Colombia); Kelly Yoana Tello Hoyos (Secretaria de Salud Departamental, Cauca, Colombia); José Cardoso-Landivar (Catholic University of Cuenca, Ecuador); Martin Van Den Boom (WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean Region, Cairo, Egypt); Claire Andréjak (Respiratory Department, CHU Amiens Picardie, Amiens, France; UR 4294, AGIR, Picardie Jules Verne University, Amiens, France); François-Xavier Blanc (Service de Pneumologie, l'institut du thorax, Nantes Université, CHU Nantes, Nantes, France); Samir Dourmane (Service de Pneumologie, Groupe hospitalier sud île de France (GHSIF), Melun, France); Antoine Froissart (Department of Internal Medicine, Intermunicipal Hospital Center of Créteil, Créteil, France); Armine Izadifar (Pneumology Department of the North Cardiology Center, Saint-Denis, France); Frédéric Rivière (Department of Pneumology, Hôpital d'Instruction des Armées Percy, Clamart, France); Frédéric Schlemmer (AP-HP, Hôpitaux Universitaires Henri Mondor, Unité de Pneumologie, Créteil, France; Université Paris Est Créteil, Faculté de Santé, INSERM, IMRB, Créteil, France); Katerina Manika (Pulmonary Department, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece); Boubacar Djelo Diallo (Faculté des Sciences et Techniques de la Santé, Université Gamal Abdel Nasser de Conakry, Service de Pneumo-Phtisiologie, CHU Conakry and Hôpital National Ignace Deen, Conakry, Guinée); Souleymane Hassane-Harouna (Damien Foundation, Conakry, Guinea); Norma Artiles (National Tuberculosis Programme, Secretaria de Salud de Honduras, Tegucigalpa, Honduras); Licenciada Andrea Mejia (Unidad de Vigilancia de la Salud, Secretaria de Salud de Honduras, Tegucigalpa, Honduras); Nitesh Gupta (Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Vardhman Mahavir Medical College and Safdarjung Hospital, New Delhi, India); Pranav Ish (Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Vardhman Mahavir Medical College and Safdarjung Hospital, New Delhi, India); Gyanshankar Mishra (Department of Respiratory Medicine, Indira Gandhi Government Medical College, Nagpur, India); Jigneshkumar M. Patel (Department of Respiratory Medicine, P.D. Hinduja National Hospital and Medical Research Centre, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India); Rupak Singla (Department of Respiratory Medicine, National Institute of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases, New Delhi, India); Zarir F. Udwadia (Department of Respiratory Medicine, P.D. Hinduja National Hospital and Medical Research Centre, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India); Francesca Alladio (Infectious Diseases Unit, Amedeo di Savoia Hospital, Department of Medical Sciences, University of Turin, Turin, Italy); Fabio Angeli (Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Insubria, Varese, Italy; Divisions of Cardiac Rehabilitation and General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine and Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation, Maugeri Care and Research Institutes, IRCCS Tradate, Varese, Italy); Andrea Calcagno (Infectious Diseases Unit, Amedeo di Savoia Hospital, Department of Medical Sciences, University of Turin, Turin, Italy); Rosella Centis (Servizio di Epidemiologia, Clinica delle Malattie Respiratorie, Istituti Clinici Scientifici Maugeri, IRCCS, Tradate, Italy); Luigi Ruffo Codecasa (Regional TB Reference Centre, Villa Marelli Institute, Niguarda Hospital, Milan, Italy); Angelo De Lauretis (Department of Pneumology, ASST Dei Sette Laghi, Varese, Italy); Susanna M.R. Esposito (Pediatric Clinic, Pietro Barilla Children's Hospital, University of Parma, Parma, Italy); Beatrice Formenti (Dept of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, University of Brescia, ASST Spedali Civili, Brescia, Italy); Alberto Gaviraghi (Infectious Diseases Unit, Amedeo di Savoia Hospital, Department of Medical Sciences, University of Turin, Turin, Italy); Vania Giacomet (Paediatric Infectious Disease Unit, Ospedale L. Sacco, Milan, Italy); Delia Goletti (Translational Research Unit, Department of Epidemiology and Preclinical Research, National Institute for Infectious Diseases L. Spallanzani, IRCCS, Roma, Italy); Gina Gualano (Respiratory Infectious Diseases Unit, National Institute for Infectious Diseases ‘L. Spallanzani’, IRCCS, Rome, Italy); Alberto Matteelli (Department of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, University of Brescia, ASST Spedali Civili, Brescia, Italy; WHO Collaborating Centre for TB/HIV and TB Elimination, Brescia, Italy); Giovanni Battista Migliori (Servizio di Epidemiologia, Clinica delle Malattie Respiratorie, Istituti Clinici Scientifici Maugeri, IRCCS, Tradate, Italy); Ilaria Motta (Infectious Diseases Unit, Amedeo di Savoia Hospital, Department of Medical Sciences, University of Turin, Turin, Italy); Fabrizio Palmieri (Respiratory Infectious Diseases Unit, National Institute for Infectious Diseases ‘L. Spallanzani’, IRCCS, Rome, Italy); Emanuele Pontali (Department of Infectious Diseases, Galliera Hospital, Genoa, Italy); Tullio Prestileo (Infectious Diseases Unit, ARNAS, Civico-Benfratelli Hospital, Palermo, Italy); Niccolò Riccardi (Department of Infectious Diseases, Tropical Medicine and Microbiology, IRCCS Ospedale Sacro Cuore Don Calabria, Negrar, Italy); Laura Saderi (Clinical Epidemiology and Medical Statistics Unit, Dept of Medical, Surgical and Experimental Sciences, University of Sassari, Sassari, Italy); Matteo Saporiti (Regional TB Reference Centre, Villa Marelli Institute, Niguarda Hospital, Milan, Italy); Giovanni Sotgiu (Clinical Epidemiology and Medical Statistics Unit, Dept of Medical, Surgical and Experimental Sciences, University of Sassari, Sassari, Italy); Antonio Spanevello (Division of Pulmonary Rehabilitation, Istituti Clinici Scientifici Maugeri, IRCCS, Tradate, Italy; Department of Medicine and Surgery, Respiratory Diseases, University of Insubria, Varese-Como, Italy); Claudia Stochino (Phthisiology Unit, Sondalo Hospital, ASST Valtellina e Alto Lario, Sondrio, Italy); Marina Tadolini (Infectious Diseases Unit, IRCCS Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Bologna, Bologna, Italy; Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, Alma Mater Studiorum University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy); Alessandro Torre (Department of Infectious Diseases, University of Milan, L. Sacco Hospital, Milan, Italy); Simone Villa (Centre for Multidisciplinary Research in Health Science (MACH), Università di Milano, Milan, Italy); Dina Visca (Division of Pulmonary Rehabilitation, Istituti Clinici Scientifici Maugeri, IRCCS, Tradate, Italy; Department of Medicine and Surgery, Respiratory Diseases, University of Insubria, Varese-Como, Italy); Xhevat Kurhasani (UBT-Higher Education Institution Prishtina, Kosovo); Mohammed Furjani (National Center for Disease Control, Tuberculosis Programme, Tripoli, Libya); Najia Rasheed (National Center for Disease Control, Tuberculosis Programme, Tripoli, Libya); Edvardas Danila (Clinic of Chest Diseases, Immunology and Allergology of Faculty of Medicine of Vilnius University, Vilnius, Lithuania; Center of Pulmonology and Allergology of Vilnius University Hospital Santaros Klinikos, Vilnius, Lithuania); Saulius Diktanas (Tuberculosis Department, Republican Klaipeda Hospital, Klaipeda, Lithuania); Ruy López Ridaura (National Center of Preventive Programs and Disease Control, Ministry of Health, Mexico City, Mexico); Fátima Leticia Luna López (National Center of Preventive Programs and Disease Control, Ministry of Health, Mexico City, Mexico); Marcela Muñoz Torrico (Clínica de Tuberculosis y Enfermedades Pleurales, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias (INER), Mexico City, México); Adrian Rendon (Universidad Autonoma de Nuevo Leon, Facultad de Medicina, Servicio de Neumologia, CIPTIR, Monterrey, Mexico); Onno W. Akkerman (TB Center Beatrixoord, Haren, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands; Department of Pulmonary Diseases and Tuberculosis, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands); Onyeaghala Chizaram (University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Port Harcourt, Nigeria); Seif Al-Abri (Directorate General for Disease Surveillance and Control, Ministry of Health, Muscat, Oman); Fatma Alyaquobi (TB and Acute Respiratory Diseases Section, Department of Communicable Diseases, Directorate General of Disease Surveillance and Control, Ministry of Health, Muscat, Oman); Khalsa Althohli (TB and Acute Respiratory Diseases Section, Department of Communicable Diseases, Directorate General of Disease Surveillance and Control, Ministry of Health, Muscat, Oman); Sarita Aguirre (Programa Nacional de Tuberculosis, Ministerio de Salud Pública y Bienestar Social (MSPBS), Asunción, Paraguay); Rosarito Coronel Teixeira (National Institute of Respiratory Diseases and the Environment (INERAM), Asunción, Paraguay; Radboud University Medical Center, TB Expert Center Dekkerswald, Department of Respiratory Diseases, Nijmegen – Groesbeek, the Netherlands); Viviana De Egea (Dirección de Vigilancia de enfermedades Transmisibles, Ministerio de Salud Pública y Bienestar Social (MSPBS), Asunción, Paraguay); Sandra Irala (Dirección de Información Epidemiológica y Vigilancia de la Salud, Ministerio de Salud Pública y Bienestar Social (MSPBS), Asunción, Paraguay); Angélica Medina (Programa Nacional de Tuberculosis, Ministerio de Salud Pública y Bienestar Social (MSPBS), Asunción, Paraguay); Guillermo Sequera (Dirección General de Vigilancia de la Salud, Ministerio de Salud Pública y Bienestar Social (MSPBS), Asunción, Paraguay); Natalia Sosa (Programa Nacional de Tuberculosis, Ministerio de Salud Pública y Bienestar Social (MSPBS), Asunción, Paraguay); Fátima Vázquez (Dirección de Información Epidemiológica y Vigilancia de la Salud, Ministerio de Salud Pública y Bienestar Social (MSPBS), Asunción, Paraguay); Félix K. Llanos-Tejada (Hospital Nacional Dos de Mayo, Lima, Peru); Selene Manga (Ministry of Health, Direccion General de Gestion de Riesgos en y desastres en salud, Lima, Peru); Renzo Villanueva-Villegas (Hospital Nacional Dos de Mayo, Lima, Peru); David Araujo (Department of Pneumology, Centro Hospitalar São João, Porto, Portugal); Raquel Duarte (EPIUnit, Institute of Public Health, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal; Laboratory of Health Community, Department of Population Studies, School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences (ICBAS), University of Porto, Porto, Portugal; Department of Pulmonology, Hospital Center Vila Nova de Gaia/Espinho, Vila Nova de Gaia, Portugal; Clinical Research Unit of the Northern Regional Health Administration, Porto, Portugal); Tânia Sales Marques (Pulmonology Department, Centro Hospitalar de Vila Nova de Gaia/Espinho, Vila Nova de Gaia, Portugal); Victor Ionel Grecu (Pneumophtisiology Department, “Victor Babes” Clinical Hospital Of Infectious Diseases and Pneumophtisiology, Craiova, Romania); Adriana Socaci (Clinical Hospital for Infectious Diseases and Pneumology “Dr Victor Babes”, Ambulatory Pneumology, Timisoara, Romania); Olga Barkanova (Tuberculosis Department, Volgograd State Medical University, Volgograd, Russian Federation); Maria Bogorodskaya (Moscow Research and Clinical Center for Tuberculosis Control, Moscow, Russian Federation; I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), Moscow, Russian Federation); Sergey Borisov (Moscow Research and Clinical Center for Tuberculosis Control Moscow, Russian Federation); Andrei Mariandyshev (Northern State Medical University, Arkhangelsk, Russian Federation); Anna Kaluzhenina (Tuberculosis Department, Volgograd State Medical University, Volgograd, Russian Federation); Tatjana Adzic Vukicevic (School of Medicine, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia); Maja Stosic (TB Programme and Surveillance Unit, Public Health Institute of Serbia “Dr Milan Jovanovic Batut”, Belgrade, Serbia); Darius Beh (Division of Infectious Diseases, National University Health System, Singapore); Deborah Ng (Infectious Diseases, National Centre for Infectious Diseases, Singapore); Catherine W.M. Ong (Infectious Diseases Translational Research Programme, Department of Medicine, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore City, Singapore; Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, National University Hospital, Singapore City, Singapore; Institute for Health Innovation and Technology (iHealthtech), National University of Singapore, Singapore City, Singapore); Ivan Solovic (National Institute for Tuberculosis, Lung Diseases and Thoracic Surgery and Catholic University Ruzomberok, Vyšné Hágy, Slovakia); Keertan Dheda (Faculty of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Department of Immunology and Infection, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK; Centre for Lung Infection and Immunity, Division of Pulmonology, Department of Medicine and UCT Lung Institute, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa; Institute of Infectious Diseases and Molecular Medicine, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa); Phindile Gina (Centre for Lung Infection and Immunity, Division of Pulmonology, Department of Medicine and UCT Lung Institute, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa); José A. Caminero (Pneumology Department, Universitary Hospital of Gran Canaria “Dr Negrin”, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain; ALOSA TB Academy, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain); Maria Luiza De Souza Galvão (Unitat de Tuberculosi de Drassanes, Hospital Universitari Vall D'Hebron, Barcelona, Spain); Angel Dominguez-Castellano (Infectious Diseases and Microbiology Department, Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Macarena, Sevilla, Spain); José-María García-García (Tuberculosis Research Programme (PII-TB), Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR), Barcelona, Spain); Israel Molina Pinargote (Serveis Clínics, Unitat Clínica de Tractament Directament Observat de La Tuberculosi, Barcelona, Spain); Sarai Quirós Fernandez (Pneumology Department, Tuberculosis Unit, Hospital de Cantoblanco – Hospital General Universitario La Paz, Madrid, Spain); Adrián Sánchez-Montalvá (International Health Unit Vall d'Hebron-Drassanes, Infectious Diseases Department, Vall d'Hebron University Hospital, PROSICS Barcelona, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Infecciosas, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain); Eva Tabernero Huguet (Pulmonology Department, Cruces University Hospital, Barakaldo, Spain); Miguel Zabaleta Murguiondo (Pulmonology Service, Hospital Valdecilla, Santander, Spain); Pierre-Alexandre Bart (Division of Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, Lausanne University Hospital and University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland); Jesica Mazza-Stalder (Division of Pulmonology, Department of Medicine, Lausanne University Hospital, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland); Lia D'Ambrosio (Public Health Consulting Group, Lugano, Switzerland); Phalin Kamolwat (Bureau of Tuberculosis, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi, Thailand); Freya Bakko (Department of Infectious Diseases, Ealing Hospital, London North West University Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK); James Barnacle (Department of Infectious Diseases, Ealing Hospital, London North West University Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK); Sophie Bird (Department of Infectious Diseases, Ealing Hospital, London North West University Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK); Annabel Brown (Department of Infectious Diseases, Ealing Hospital, London North West University Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK); Shruthi Chandran (Department of Infectious Diseases, Ealing Hospital, London North West University Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK); Kieran Killington (Department of Infectious Diseases, Ealing Hospital, London North West University Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK); Kathy Man (Department of Infectious Diseases, Ealing Hospital, London North West University Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK); Padmasayee Papineni (Department of Infectious Diseases, Ealing Hospital, London North West University Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK); Flora Ritchie (Department of Infectious Diseases, Ealing Hospital, London North West University Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK); Simon Tiberi (Blizard Institute, Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK); Natasa Utjesanovic (Division of Infection, Royal London Hospital, Barts Health NHS Trust, London, UK); Dominik Zenner (Faculty of Population Health Sciences, University College London, UK; Wolfson Institute of Population Health, Queen Mary University London, UK); Jasie L. Hearn (Division of Clinical Epidemiology, Virginia Department of Health, Richmond, VA, USA); Scott Heysell (Division of Infectious Diseases and International Health, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA); Laura Young (Division of Clinical Epidemiology, Virginia Department of Health, Richmond, VA, USA).

Footnotes

This article has an editorial commentary: https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01881-2023

This study is part of the scientific activities of the Global Tuberculosis Network (GTN).

We thank the GREPI (Groupe de Recherche et d'Enseignement en Pneumo-Infectiologie), a working group from SPLF (Société de Pneumologie de Langue Française), for gathering information.

Ethics statement: Ethical approval was obtained by the coordinating centre and in each country as per national regulations in force.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Support statement: This work was partially funded by the “Ricerca Corrente” scheme of the Ministry of Health, Italy.

Contributor Information

Global Tuberculosis Network and TB/COVID-19 Global Study Group:

Nicolas Casco, Alberto Levi Jorge, Domingo Juan Palmero, Jan-Willem Alffenaar, Greg J. Fox, Wafaa Ezz, Jin-Gun Cho, Justin Denholm, Alena Skrahina, Varvara Solodovnikova, Marcos Abdo Arbex, Tatiana Alves, Marcelo Fouad Rabahi, Giovana Rodrigues Pereira, Roberta Sales, Denise Rossato Silva, Muntasir M. Saffie, Nadia Escobar Salinas, Ruth Caamaño Miranda, Catalina Cisterna, Clorinda Concha, Israel Fernandez, Claudia Villalón, Carolina Guajardo Vera, Patricia Gallegos Tapia, Viviana Cancino, Monica Carbonell, Arturo Cruz, Eduardo Muñoz, Camila Muñoz, Indira Navarro, Rolando Pizarro, Gloria Pereira Cristina Sánchez, Maria Soledad Vergara Riquelme, Evelyn Vilca, Aline Soto, Ximena Flores, Ana Garavagno, Martina Hartwig Bahamondes, Luis Moyano Merino, Ana María Pradenas, Macarena Espinoza Revillot, Patricia Rodriguez, Angeles Serrano Salinas, Carolina Taiba, Joaquín Farías Valdés, Jorge Navarro Subiabre, Carlos Ortega, Sofia Palma, Patricia Perez Castillo, Mónica Pinto, Francisco Rivas Bidegain, Margarita Venegas, Edith Yucra, Yang Li, Andres Cruz, Beatriz Guelvez, Regina Victoria Plaza, Kelly Yoana Tello Hoyos, José Cardoso-Landivar, Martin Van Den Boom, Claire Andréjak, François-Xavier Blanc, Samir Dourmane, Antoine Froissart, Armine Izadifar, Frédéric Rivière, Frédéric Schlemmer, Katerina Manika, Boubacar Djelo Diallo, Souleymane Hassane-Harouna, Norma Artiles, Licenciada Andrea Mejia, Nitesh Gupta, Pranav Ish, Gyanshankar Mishra, Jigneshkumar M. Patel, Rupak Singla, Zarir F. Udwadia, Francesca Alladio, Fabio Angeli, Andrea Calcagno, Rosella Centis, Luigi Ruffo Codecasa, Angelo De Lauretis, Susanna M.R. Esposito, Beatrice Formenti, Alberto Gaviraghi, Vania Giacomet, Delia Goletti, Gina Gualano, Alberto Matteelli, Giovanni Battista Migliori, Ilaria Motta, Fabrizio Palmieri, Emanuele Pontali, Tullio Prestileo, Niccolò Riccardi, Laura Saderi, Matteo Saporiti, Giovanni Sotgiu, Antonio Spanevello, Claudia Stochino, Marina Tadolini, Alessandro Torre, Simone Villa, Dina Visca, Xhevat Kurhasani, Mohammed Furjani, Najia Rasheed, Edvardas Danila, Saulius Diktanas, Ruy López Ridaura, Fátima Leticia Luna López, Marcela Muñoz Torrico, Adrian Rendon, Onno W. Akkerman, Onyeaghala Chizaram, Seif Al-Abri, Fatma Alyaquobi, Khalsa Althohli, Sarita Aguirre, Rosarito Coronel Teixeira, Viviana De Egea, Sandra Irala, Angélica Medina, Guillermo Sequera, Natalia Sosa, Fátima Vázquez, Félix K. Llanos-Tejada, Selene Manga, Renzo Villanueva-Villegas, David Araujo, Raquel DuarteTânia Sales Marques, Adriana Socaci, Olga Barkanova, Maria Bogorodskaya, Sergey Borisov, Andrei Mariandyshev, Anna Kaluzhenina, Tatjana Adzic Vukicevic, Maja Stosic, Darius Beh, Deborah Ng, Catherine W.M. Ong, Ivan Solovic, Keertan Dheda, Phindile Gina, José A. Caminero, Maria Luiza De Souza Galvão, Angel Dominguez-Castellano, José-María García-García, Israel Molina Pinargote, Sarai Quirós Fernandez, Adrián Sánchez-Montalvá, Eva Tabernero Huguet, Miguel Zabaleta Murguiondo, Pierre-Alexandre Bart, Jesica Mazza-Stalder, Lia D'Ambrosio, Phalin Kamolwat, Freya Bakko, James Barnacle, Sophie Bird, Annabel Brown, Shruthi Chandran, Kieran Killington, Kathy Man, Padmasayee Papineni, Flora Ritchie, Simon Tiberi, Natasa Utjesanovic, Dominik Zenner, Jasie L. Hearn, Scott Heysell, and Laura Young

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Global Tuberculosis Report 2022. www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2022. Date last accessed: 1 March 2023.

- 2.Migliori GB, Thong PM, Alffenaar JW, et al. . Gauging the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on tuberculosis services: a global study. Eur Respir J 2021; 58: 2101786. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01786-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Migliori GB, Thong PM, Akkerman O, et al. . Worldwide effects of coronavirus disease pandemic on tuberculosis services, January–April 2020. Emerg Infect Dis 2020; 26: 2709–2712. doi: 10.3201/eid2611.203163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Migliori GB, Thong PM, Alffenaar JW, et al. . Country-specific lockdown measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on tuberculosis control: a global study. J Bras Pneumol 2022; 48: e20220087. doi: 10.36416/1806-3756/e20220087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodrigues I, Aguiar A, Migliori GB, et al. . Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on tuberculosis services. Pulmonology 2022; 28: 210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.pulmoe.2022.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alves A, Aguiar A, Migliori GB, et al. . COVID-19 related hospital re-organization and trends in tuberculosis diagnosis and admissions: reflections from Portugal. Arch Bronconeumol 2022; 58: 66–68. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2021.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ong CWM, Migliori GB, Raviglione M, et al. . Epidemic and pandemic viral infections: impact on tuberculosis and the lung. Eur Respir J 2020; 56: 2001727. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01727-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Motta I, Centis R, D'Ambrosio L, et al. . Tuberculosis, COVID-19 and migrants: preliminary analysis of deaths occurring in 69 patients from two cohorts. Pulmonology 2020; 26: 233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.pulmoe.2020.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tadolini M, Codecasa LR, García-García J-M, et al. . Active tuberculosis, sequelae and COVID-19 co-infection: first cohort of 49 cases. Eur Respir J 2020; 56: 2001398. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01398-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.TB/COVID-19 Global Study Group . Tuberculosis and COVID-19 co-infection: description of the global cohort. Eur Respir J 2022; 59: 2102538. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02538-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Visca D, Ong CWM, Tiberi S, et al. . Tuberculosis and COVID-19 interaction: a review of biological, clinical and public health effects. Pulmonology 2021; 27: 151–165. doi: 10.1016/j.pulmoe.2020.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boulle A, Davies MA, Hussey H, et al. . Risk factors for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) death in a population cohort study from the Western Cape province, South Africa. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73: E2005–E2015. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sy KTL, Haw NJL, Uy J. Previous and active tuberculosis increases risk of death and prolongs recovery in patients with COVID-19. Infect Dis 2020; 52: 902–907. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2020.1806353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stochino C, Villa S, Zucchi P, et al. . Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 and active tuberculosis co-infection in an Italian reference hospital. Eur Respir J 2020; 56: 2001708. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01708-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization . WHO COVID-19 Case Definition. www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Surveillance_Case_Definition-2022.1. Date last updated: 22 July 2022.

- 16.European Parliament . Assessment of COVID-19 Surveillance Case Definitions and Data Reporting in the European Union. www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/IPOL_BRI(2020)652725. Date last accessed: 1 March 2023.

- 17.Petrone L, Petruccioli E, Vanini V, et al. . Coinfection of tuberculosis and COVID-19 limits the ability to in vitro respond to SARS-CoV-2. Int J Infect Dis 2021; 113: Suppl. 1, S82–S87. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.02.090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Najafi-Fard S, Aiello A, Navarra A, et al. . Characterization of the immune impairment of patients with tuberculosis and COVID-19 coinfection. Int J Infect Dis 2023; 130: Suppl. 1, S34–S42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2023.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crocker-Buque T, Williams S, Brentnall AR, et al. . The Barts Health NHS Trust COVID-19 cohort: characteristics, outcomes and risk scoring of patients in East London. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2021; 25: 358–366. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.20.0926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Müller AM, Osório CS, Figueiredo RV, et al. . Post-discharge mortality in adult patients hospitalized for tuberculosis: a prospective cohort study. Brazilian J Med Biol Res 2023; 56: e12236. doi: 10.1590/1414-431x2023e12236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicholson TJ, Hoddinott G, Seddon JA, et al. . A systematic review of risk factors for mortality among tuberculosis patients in South Africa. Syst Rev 2023; 12: 23. doi: 10.1186/s13643-023-02175-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heunis JC, Kigozi NG, Chikobvu P, et al. . Risk factors for mortality in TB patients: a 10-year electronic record review in a South African province. BMC Public Health 2017; 17: 38. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3972-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oursler KK, Moore RD, Bishai WR, et al. . Survival of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis: clinical and molecular epidemiologic factors. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 34: 752–759. doi: 10.1086/338784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silva DR, Menegotto DM, Schulz LF, et al. . Factors associated with mortality in hospitalized patients with newly diagnosed tuberculosis. Lung 2010; 188: 33–41. doi: 10.1007/s00408-009-9224-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta RK, Harrison EM, Ho A, et al. . Development and validation of the ISARIC 4C Deterioration model for adults hospitalised with COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9: 349–359. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30559-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma Q, Liu J, Liu Q, et al. . Global percentage of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections among the tested population and individuals with confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4: e2137357. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.37257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sen-Crowe B, Sutherland M, McKenney M, et al. . A closer look into global hospital beds capacity and resource shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Surg Res 2021; 260: 56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2020.11.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drug Interaction Report: Tofacitinib and Rifampin. www.drugs.com/interactions-check.php?drug_list=3429-0,2012-0. Date last accessed: 24 May 2023.

- 29.Selvaraju S, Thiruvengadam K, Watson B, et al. . Long-term survival of treated tuberculosis patients in comparison to a general population in south India: a matched cohort study. Int J Infect Dis 2021; 110: 385–393. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.07.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mainous AG, Rooks BJ, Wu V, et al. . COVID-19 post-acute sequelae among adults: 12 month mortality risk. Front Med 2021; 8: 778434. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.778434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uusküla A, Jürgenson T, Pisarev H, et al. . Long-term mortality following SARS-CoV-2 infection: a national cohort study from Estonia. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2022; 18: 100394. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pontali E, Silva DR, Marx FM, et al. . Breathing back better! A state of the art on the benefits of functional evaluation and rehabilitation of post-tuberculosis and post-COVID lungs. Arch Bronconeumol 2022; 58: 754–763. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2022.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Migliori GB, Marx FM, Ambrosino N, et al. . Clinical standards for the assessment, management and rehabilitation of post-TB lung disease. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2021; 25: 797–813. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.21.0425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Visca D, Centis R, Pontali E, et al. . Clinical standards for diagnosis, treatment and prevention of post-COVID-19 lung disease. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2023; 27: 729–741. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.23.0248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nightingale R, Carlin F, Meghji J, et al. . Post-TB health and wellbeing. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2023; 27: 248–283. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.22.0514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silva DR, Mello FCQ, Migliori GB. Diagnosis and management of post-tuberculosis lung disease. J Bras Pneumol 2023; 49: e20230055. doi: 10.36416/1806-3756/e20230055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hellemons ME, Huijts S, Bek L, et al. . Persistent health problems beyond pulmonary recovery up to 6 months after hospitalization for COVID-19: a longitudinal study of respiratory, physical and psychological outcomes. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2022; 19: 551–561. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202103-340OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nasiri MJ, Silva DR, Rommasi F, et al. . Vaccination role in post-tuberculosis lung disease management: a review of the evidence. Pulmonology 2023; in press [ 10.1016/j.pulmoe.2023.07.002]. doi: 10.1016/j.pulmoe.2023.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material ERJ-00925-2023.Supplement (256.9KB, pdf)

This one-page PDF can be shared freely online.

Shareable PDF ERJ-00925-2023.Shareable (233.2KB, pdf)