Abstract

Germline mutations are the ultimate source of genetic variation and the raw material for organismal evolution. Despite their significance, the frequency and genomic locations of mutations, as well as potential sex bias, are yet to be widely investigated in most species. To address these gaps, we conducted whole-genome sequencing of 12 great reed warblers (Acrocephalus arundinaceus) in a pedigree spanning 3 generations to identify single-nucleotide de novo mutations (DNMs) and estimate the germline mutation rate. We detected 82 DNMs within the pedigree, primarily enriched at CpG sites but otherwise randomly located along the chromosomes. Furthermore, we observed a pronounced sex bias in DNM occurrence, with male warblers exhibiting three times more mutations than females. After correction for false negatives and adjusting for callable sites, we obtained a mutation rate of 7.16 × 10−9 mutations per site per generation (m/s/g) for the autosomes and 5.10 × 10−9 m/s/g for the Z chromosome. To demonstrate the utility of species-specific mutation rates, we applied our autosomal mutation rate in models reconstructing the demographic history of the great reed warbler. We uncovered signs of drastic population size reductions predating the last glacial period (LGP) and reduced gene flow between western and eastern populations during the LGP. In conclusion, our results provide one of the few direct estimates of the mutation rate in wild songbirds and evidence for male-driven mutations in accordance with theoretical expectations.

Keywords: de novo mutation, CpG sites, sex bias, demographic history, bird

Significance.

Mutations in germline cells are inherited across generations and provide the raw material for organismal evolution. Studying mutations used to be technically very challenging, but this is now changing, thanks to recent biotechnology and analytical developments that facilitate generating and screening whole-genome data. We have been using these new methodologies to study the germline mutation rate in a wild songbird that breeds across a large part of Eurasia, the great reed warbler. We uncovered that more mutations occurred in males than in females and on specific dinucleotides with cytosine and guanine bases, that is, CpG sites. Moreover, we applied the estimated mutation rate to profile the demographic history of this widespread songbird around the last glacial period.

Introduction

Mutations constitute the raw material for evolution by fueling genetic variation that selection can act upon to drive adaptations to changing environments (Loewe and Hill 2010; Lynch et al. 2016). This key role of mutations in ecology and evolution has made understanding mutagenesis, and describing the frequency, types, chromosomal distribution, and fitness effects of mutations, important goals in evolutionary biology research (Eyre-Walker and Keightley 2007; Seplyarskiy and Sunyaev 2021).

Mutations come in different forms and effects, from changes at single nucleotides to large-scale chromosomal alterations and from detrimental to positive effects on proteins, phenotypes, and fitness (Eyre-Walker and Keightley 2007; Loewe and Hill 2010). When occurring in protein-coding genes, mutations may alter the amino acid composition and thus impact the function of the protein. For example, most cases of sickle cell anemia are caused by abnormal hemoglobin due to a change of amino acids resulting from a single-nucleotide point mutation in the β-globin gene (Rees et al. 2010). The list of mutations with described effects is continuously expanding and comprises single point mutations inducing chilling sensitivity in Arabidopsis (Wang et al. 2013) and sex determination in the tiger pufferfish (Takifugu rubripes; Kamiya et al. 2012), as well as large-scale chromosomal rearrangements such as inversions associated with plumage and behavioral morphs of the ruff (Philomachus pugnax; Lamichhaney et al. 2016) and mimicry in Heliconius butterflies (Joron et al. 2011). The frequency and persistence of a mutation depend on its functional and selective properties, and mutations may invade, spread, and eventually become fixed in a population due to advantages that individuals acquire when carrying them. However, most nonsynonymous mutations are (partially) deleterious and thus selectively unfavorable, which result in very low frequencies in the population (Glémin 2003; Whitlock and Agrawal 2009).

The germline mutation rate is a key parameter in evolutionary and population genetic studies, being used for rescaling the coalescence-based estimation of effective population size (Ne) into real time and dating phylogenetic trees. However, due to the rarity of mutations, mutation rates are notoriously difficult to accurately estimate. A classical genetic approach to estimate the mutation rate is by calculating equilibrium frequencies of fully penetrant dominant monogenic Mendelian disorders with major phenotypic effects in pedigrees (Haldane 1935; Kondrashov 2003). Alternatively, phylogenetic estimation has been carried out using data of putatively neutral regions, such as pseudogenes or at 4-fold degenerate sites (Nachman and Crowell 2000; De Maio et al. 2021). However, both these approaches for estimating mutation rates are susceptible to problems in their methodology (e.g., dependence on major phenotypic effects or complicated sequence alignments) and underlying assumptions (e.g., selective neutrality and constant population sizes). The advancement of next-generation sequencing technology now enables direct detection of de novo mutations (DNMs) by comparing the full genome sequence of inbred lines from mutation accumulation experiments (Halligan and Keightley 2009) and relatives in shallow pedigrees, such as fullsibs, parent–offspring trios, or three-generation pedigrees (Keightley et al. 2014; Smeds et al. 2016). Facilitated by well-developed genome assemblies also for nonmodel organisms, pedigree-based genome-wide methods are increasingly implemented for estimating mutation rates in natural populations of mammals, fish, and birds (Smeds et al. 2016; Feng et al. 2017; Koch et al. 2019; Bergeron et al. 2023). This is a positive development as direct detection of mutations in pedigrees in natural populations generates estimates of mutation rates that are not biased by genetic drift and long-term selection and allows quantifying different mutation types (e.g., transitions [Ts] and transversions [Tv], or enrichment at certain nucleotide sites) without assumptions of the ancestral states.

Point mutations arise spontaneously by erroneous base incorporation during replication of nondamaged DNA or by failure of repairing damaged DNA and can in theory occur anywhere in the genome (Seplyarskiy and Sunyaev 2021). Direct detection of mutations in pedigrees has, however, revealed that mutations are not entirely randomly distributed. For example, mutations are more frequently occurring near recombination locations, possibly because the recombination process is tightly associated with the DNA break and repair system (Seplyarskiy and Sunyaev 2021). From this observation, mutation rate and recombination rate would be expected to covary along chromosomes. However, such a chromosome-wide association between mutation and recombination has received inconsistent support (Spencer et al. 2006; Kessler et al. 2020). In contrast, at the fine-scale level, data from both mammals and birds indicate that CpG sites (i.e., a cytosine followed by a guanine) have substantially higher mutation frequencies than other sites in the genome (Kong et al. 2012; Smeds et al. 2016; Bergeron et al. 2021). CpG sites are commonly methylated, and it has been suggested that this modification of the DNA molecule interferes with the polymerase to induce mismatches during DNA replication and consequently result in higher mutation frequencies (Seplyarskiy and Sunyaev 2021).

Mutation rates vary across species, which is evident in mammals where rates span from 4.5 to 16.6 × 10−9 mutations per site per generation (m/s/g) (Besenbacher et al. 2019; Koch et al. 2019). This divergence among species potentially relates to differences in metabolic rate, body size, and the environment they inhabit (Fontanillas et al. 2007). Additionally, in line with the widely acknowledged drift–barrier hypothesis, mutation rates across species may negatively correlate with the effective population size (Lynch et al. 2016). The mutation rate can also exhibit variation within species. For instance, it has been predicted that males possess higher mutation rates than females due to ongoing continuous cell division throughout spermatogenesis, in contrast to the limited number of cell divisions occurring during oogenesis, which is confined to the postnatal development phase (Haldane 1946; Miyata et al. 1987; Shimmin et al. 1993; Li et al. 2002; Zhang et al. 2022). This hypothesis has received support from data showing strongly male-biased mutation rates in several studies of primates and humans (Kong et al. 2012; Venn et al. 2014; Thomas et al. 2018; Gao et al. 2019). When only weak male biases have been observed, other confounding factors were suspected, particularly age (Smeds et al. 2016; Campbell et al. 2021). Age can influence the mutation rate as the efficacy of DNA repair mechanisms diminishes over time (Kong et al. 2012; Seplyarskiy and Sunyaev 2021). Furthermore, age and sex may interact, as seen in humans, where males exhibit a notably stronger age-related effect on the mutation rate than females (Kong et al. 2012; Wong et al. 2016).

Birds have long been a focal system for the study of ecology and evolution. For a long period of time, the only available direct estimate of the germline mutation rate in birds was for the collared flycatcher (Ficedula albicollis), where a whole-genome comparison of parents and offspring in a three-generation pedigree recorded a rate of 4.6 × 10−9 m/s/g (Smeds et al. 2016). However, a recent study expanded the list of avian mutation rates with another 18 species using parent–offspring trios (Bergeron et al. 2023). Notably, the estimated mutation rates in these species showed a large variation (range: 1.0–39.8 × 10−9 m/s/g), but there was also substantial within-species variation in the mutation rate (e.g., a range between 4.1 and 10.6 × 10−9 m/s/g among different pedigrees in the herring gull, Larus argentatus; Bergeron et al. 2023). This raises the question of the ultimate cause of this within- and between-species variation in mutation rates but also about the robustness of mutation rate estimation in single or few parent–offspring trios (c.f., Yoder and Tiley 2021). Here, to provide an additional robust mutation rate estimate in birds, we identify genome-wide single-nucleotide DNMs in a three-generation pedigree of the great reed warbler (Acrocephalus arundinaceus). This species is a long-distance migrant that breeds in lakes and marshes over most of Eurasia and winters in sub-Saharan Africa (Koleček et al. 2016; Dyrcz 2020). We sequenced the genomes of parents and offspring in a randomly selected three-generation pedigree from our long-term study population of the great reed warbler in Sweden (Bensch et al. 1998; Hansson et al. 2018). We aligned the sequence reads to our reference genome assembly of the species (Sigeman et al. 2021) and detected DNMs in the pedigree by applying highly stringent filtering of the data. This allowed us to evaluate whether mutations occur randomly along the chromosomes, whether they are enriched at certain nucleotide sites, and to test the prediction that germline mutations are male-driven in birds (Ellegren and Fridolfsson 1997; Smeds et al. 2016; Bergeron et al. 2023). We estimated the mutation rate on autosomes and the Z chromosome separately and used simulations to estimate the false negative rate (FNR). Finally, to demonstrate the usefulness of species-specific mutation rates, we applied our autosomal mutation rate in models reconstructing the demographic history of the great reed warbler. We were particularly interested in evaluating signs of a population bottleneck with two refugia populations during the last glacial period (LGP) previously suggested for the great reed warbler (Bensch and Hasselquist 1999; Hansson et al. 2008).

Results

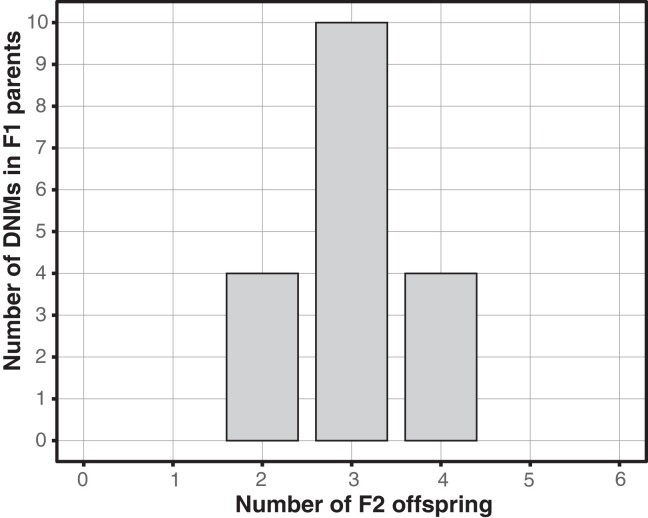

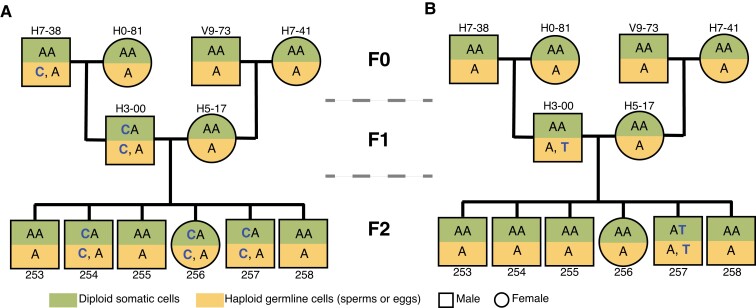

Number of DNMs and the Mutation Rate

In total, we detected 82 DNMs, 18 in the 2 individuals in the F1 generation (n = 13 and 5 DNMs, respectively) and 64 in the 6 offspring in the F2 generation (7–17 DNMs; table 1, supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online). Of the 18 DNMs identified in the F1 generation, 4 were transmitted to 2 offspring, 10 to 3 offspring, and 4 to 4 offspring (fig. 1). This pattern is consistent with the expected transmission probability of 0.5 for germline mutations, supporting the notion that the identified DNMs indeed are germline mutations, as opposed to somatic mutations.

Table 1.

Summary of the DNMs Identified in the Great Reed Warbler

| Generation | ID | Sex | Father | Mother | Agea | DNMb | Typec | Origind |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F0 | H7-38 | Male | ≥3 | |||||

| F0 | H0-81 | Female | 3 | |||||

| F0 | V9-73 | Male | 2 | |||||

| F0 | H7-41 | Female | ≥6 | |||||

| F1 | H3-00 | Male | H7-38 | H0-81 | 4 | 12 A, 1 Z | 12 Ts, 1 Tv | 6 P, 2 M, 5 NA |

| F1 | H5-17 | Female | V9-73 | H7-41 | 2 | 4 A, 1 Z | 5 Ts, 0 Tv | 4 P, 0 M, 1 NA |

| F2 | 253 | Male | H3-00 | H5-17 | 6 A, 1 Z | 5 Ts, 2 Tv | 3 P, 3 M, 1 NA | |

| F2 | 254 | Male | H3-00 | H5-17 | 11 A, 0 Z | 7 Ts, 4 Tv | 3 P, 0 M, 8 NA | |

| F2 | 255 | Male | H3-00 | H5-17 | 12 A, 0 Z | 8 Ts, 4 Tv | 3 P, 3 M, 6 NA | |

| F2 | 256 | Female | H3-00 | H5-17 | 10 A, 0 Z | 6 Ts, 4 Tv | 5 P, 1 M, 4 NA | |

| F2 | 257 | Male | H3-00 | H5-17 | 7 A, 0 Z | 5 Ts, 2 Tv | 3 P, 1 M, 3 NA | |

| F2 | 258 | Male | H3-00 | H5-17 | 16 A, 1 Z | 12 Ts, 5 Tv | 6 P, 1 M, 10 NA | |

| Total | 78 A, 4 Z | 60 Ts, 22 Tv | 33 P, 11 M, 38 NA |

aAge at reproduction, years.

bA, autosomal; Z, Z-linked.

cTs, transition; Tv, transversion.

dP, paternal; M, maternal; NA, not available.

Fig. 1.

Histogram of the number of F2 offspring inheriting each DNM detected in F1 parents (n = 18 DNMs). Note that a germline mutation detected in an F1 parent is expected to be transmitted with a probability of 0.5 (i.e., it is expected to occur on average in three of the six offspring), whereas a somatic mutation is not expected to be transmitted to any offspring.

With respect to chromosome types, 78 DNMs were located on autosomes and 4 on the Z chromosome (table 1, supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online). After filtering genomic regions with low mappability and high repeat content, the number of autosomal callable sites (773.8 Mb) corresponded to 71.57% of the autosomal part of the genome assembly (1,081.2 Mb) and the number of Z-linked callable sites (63.6 Mb) to 71.61% of the Z-linked part of the genome (88.9 Mb). In a χ2 test where we accounted for the size of callable regions and the number of segregating chromosomes in the pedigree (16 for autosomes and 14 for the Z chromosome), the number of identified DNMs did not differ significantly between autosomes and the Z chromosome (χ2 = 0.86, df = 1, P = 0.35). The autosomal mutation rate (µautosome) can be estimated as 78/(16 × 773.8 × 106) = 6.30 × 10−9 m/s/g (95% CI = 4.90–7.70 × 10−9 m/s/g assuming that the mutations are Poisson distributed) and the Z chromosome mutation rate (µchrZ) as 4/(14 × 63.6 × 106) = 4.49 × 10−9 m/s/g (95% CI = 0.09–8.89 × 10−9 m/s/g). The simulation analysis of the FNR showed a recovery of 88 out of 100 simulated DNMs, rendering a FNR of 12% (i.e., 1–88/100). Correcting µ for false negatives (using the formula: µ/(1 – FNR)) resulted in µautosome_corr = 7.16 × 10−9 m/s/g and µchrZ_corr = 5.10 × 10−9 m/s/g. Mutation rate estimates for each individual and calculations of interindividual variation are given in supplementary table S3, Supplementary Material online.

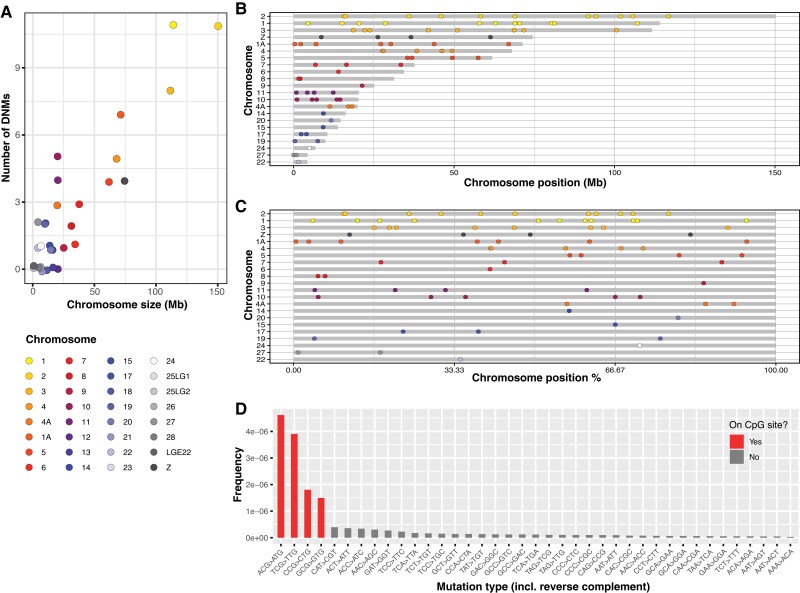

Chromosomal Location and Mutational Spectrum

We managed to assign 80 of the 82 DNMs to specific chromosomes using synteny analyses to the great tit genome (fig. 2A–C). As expected, there was a significant correlation between the number of DNMs and the size of the chromosome (rho = 0.76, n = 32 chromosomes, P = 4.6 × 10−7; fig. 2A). The position of the DNMs on the chromosome (fig. 2B) did not differ from a random pattern (tested by dividing each chromosome in three equally sized parts; χ2 = 0.925, df = 2, P = 0.63; fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

(A) Relationship between the number of DNMs and the size of the chromosomes. (B) Physical chromosomal positions and (C) relative chromosomal positions of the DNMs. (D) Frequency of mutation types for DNMs on CpG sites (red) or non-CpG sites (gray) after normalizing by the abundance of each 3-mer type in the genome. Note that 3-mers without DNMs are not shown.

Of the 82 DNMs, 60 were Ts, whereas 22 were Tv (table 1, supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online), which yielded a Ts/Tv ratio of 2.73 (the observed numbers are significantly different from an expected ratio of 0.5 (Stoltzfus and Norris 2016); χ2 = 58.6, df = 1, P < 2.0 × 10−14). Next, the 82 DNMs were classified into different types based on their trinucleotide (3-mer) category (the DNM site ± 1 bp), and the counts of DNMs in each type were normalized by the abundance of each 3-mer type in the genome. This analysis revealed a highly elevated occurrence of DNMs on CpG sites (fig. 2D), with about 30 times more CpG mutations (18 of 82 DNMs, 21.95%; supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online) than expected from the proportion of CpG sites in the genome (0.72%; exact binomial test of goodness-of-fit, P < 2.2 × 10−16). All the 18 CpG mutations were Ts (C to T or G to A; supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online).

We also tested whether the distribution of mutations differed between intergenic and genic regions, exons and introns, and untranslated region (UTR) and coding sequences (CDS), but found no significant differences (χ2 tests accounting for the proportion of such elements in the genome; P = 0.20, 0.43 and 0.55, respectively).

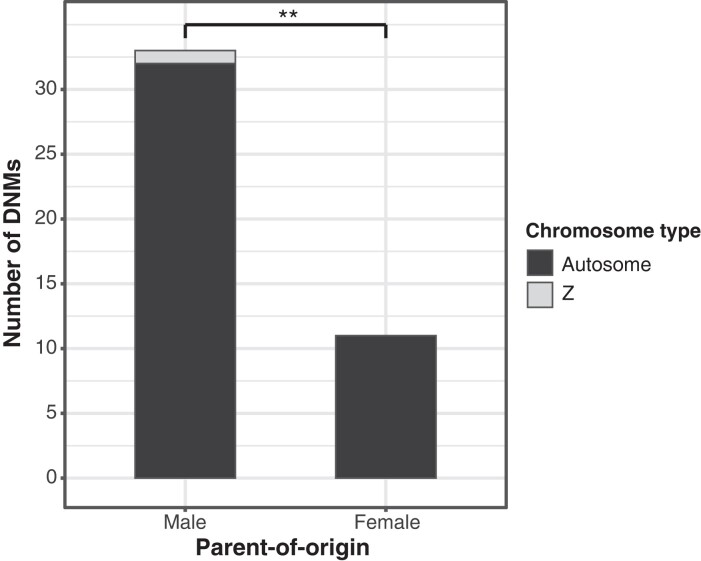

Parent-of-origin

We managed to infer the parent-of-origin for 44 of the 82 DNMs (table 1, supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online). Twelve were traced back to the F0 generation and 32 to the F1 generation. There was a significant sex bias among the DNMs with 33 being assigned to a male parent (including 1 on the Z chromosome) and 11 to a female parent (χ2 = 10.67, df = 1, P = 0.0011; fig. 3). This gives a male-biased mutation rate of 3.0 (33/11).

Fig. 3.

Parent-of-origin for the DNMs (n = 43 autosomal and 1 Z-linked DNM). There were 3.0 times as many DNMs in males (n = 33) than in females (n = 11; **P = 0.0011).

Demographic History of the Western and Eastern Populations of the Great Reed Warbler

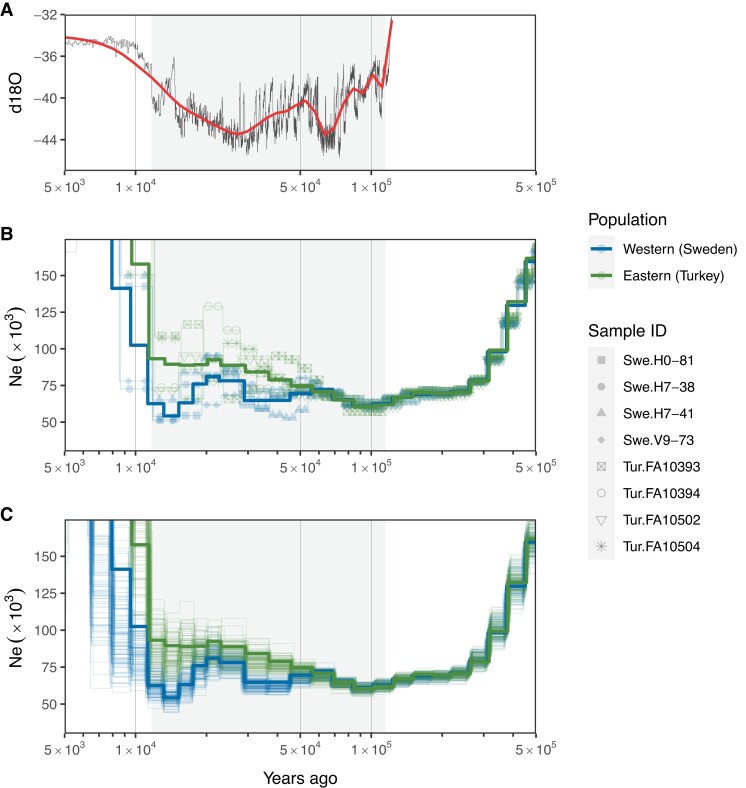

We conducted multiple sequentially Markovian coalescent (MSMC) analyses to investigate the demographic history (Ne) of western (Swedish) and eastern (Turkish) populations and used the corrected autosomal mutation rate (7.16 × 10−9 m/s/g) and the estimated generation time of 2.44 years (supplementary table S4, Supplementary Material online) to rescale the demographic history to real time (fig. 4). The Ne of both populations started a drastic reduction 500 thousand years ago (kya), which is ∼400 kyr before the beginning of LGP (∼115 kya). This was followed by a steady period with similar Ne for the populations from 200 kya, over the initiation of the LGP, to ∼50 kya. After ∼50 kya, the Ne trajectories of the two populations started to deviate with the eastern population showing a steady increase, whereas the western population remained at lower levels. Around 30 kya, the Ne trajectory of the western population showed an increase in size and then a decrease after ∼20 kya. In figure 4, we also show the fluctuation in temperature during LGP as indicated by the oxygen isotope profile (δ18O) in Greenland ice cores (Rasmussen et al. 2014; Seierstad et al. 2014).

Fig. 4.

(A) Fluctuation in temperature during the LGP as indicated by the oxygen isotope profile (δ18O) at North Greenland Ice Core Project (NGRIP) sites over a Greenland Ice Core Chronology 2005 timescale (GICC05modelext; Rasmussen et al. 2014; Seierstad et al. 2014). The red line shows smoothing δ18O-values with the “loess” method. (B, C) Demographic history of the great reed warbler of western (Swedish, blue; individuals Swe.H0-81, Swe.H7-38, Swe.H7-41, and Swe.V9-73) and eastern (Turkish, green; Individuals Tur.FA10393, Tur.FA10394, Tur.FA10502, and Tur.FA10504) populations between 5 × 103 and 5 × 105 years ago showing that both populations experienced a drastic reduction in effective population size (Ne) from 500 kya, followed by a steady period with low Ne in populations from 200 kya, over the start of the LGP (∼115 kya), to ∼50 kya. After ∼50 kya, the Ne trajectories of the two populations started to deviate with the eastern population showing a steady increase, whereas the western population remained at lower levels. Around 30 kya, the Ne trajectory of the western population showed an increase in size and then a decrease after ∼20 kya. Thick lines represent MSMC run on four-individual set-up for each population, whereas (B) thin lines with symbols represent the runs for each individual and (C) thin lines without symbols represent the runs of 100 bootstrapped datasets. All Ne trajectories were scaled to real time using a generation time of 2.44 years and the corrected autosomal mutation rate estimate from this study (7.16 × 10−9 m/s/g). The shaded area indicates the LGP.

Discussion

By sequencing the genomes of 12 great reed warblers in a three-generation pedigree and conducting stringent bioinformatic filtering, we managed to detect 82 DNMs in ∼72% of the genome. The 18 mutations detected in the parents (F1 generation) were transmitted to on average 3 (range 2–4) of the 6 offspring (F2 generation). This is in line with the expectation of random segregation of germline mutations (each mutation is expected to have a 50% chance of being transmitted to each offspring), but in sharp contrast to what is expected for somatic mutations (where no mutation is expected to be transmitted to any of the offspring). Hence, we conclude that the mutations detected in the F1 generation are germline mutations and therefore believe that the same is true also for the 64 DNMs detected in the F2 generation.

The majority of the mutations was Ts, and we found a Ts/Tv ratio of 2.73 in the great reed warbler. Notably, this is almost identical to the Ts/Tv ratio of 2.67 estimated in the collared flycatcher (Smeds et al. 2016) and the mean ratio of 2.80 for 18 other bird species (range: 0.75–5.00; Bergeron et al. 2023). Positive Ts/Tv ratios are expected because transitions are changes between two nucleotides with similar chemical structures (pyrimidine to pyrimidine or purine to purine; Kimura 1980). Another prominent mutational feature in our data was a very strong mutation enrichment at CpG sites (fig. 2D). This seems to be a general pattern in birds and mammals as a similar CpG mutational bias has previously been found in the collared flycatcher (Smeds et al. 2016) and the gray mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus; Campbell et al. 2021). The hypermutability of CpG sites may be explained by such sites frequently being methylated. The suggested underlying mechanisms linking methylation with mutations predict an exceptional rate of transitions at CpG sites (Seplyarskiy and Sunyaev 2021), which is in line with our finding that all CpG mutations were in fact transitions. A bias toward transitions at CpG sites, although not as extreme as in our case, has also been found in other species (Schrider et al. 2013; Venn et al. 2014), including in birds (Smeds et al. 2016).

The GC content is fairly evenly distributed over the chromosomes in the great reed warbler (data for the Z chromosome is given in Ponnikas et al. 2022), which can explain why we did not find that the DNMs clustered on specific parts of the chromosomes. However, although mutations are much more likely to happen on CpG sites than expected from their frequency, such sites are relatively scarce and the absolute number of mutations on CpG sites was moderate (18 of 82 DNMs; supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online). Recombination is another process that generally promotes mutations (Meunier and Duret 2004; Pessia et al. 2012). However, crossovers are heavily skewed toward the chromosome ends in the great reed warbler (Ponnikas et al. 2022; Zhang et al., unpublished) and there was no such skew in the distribution of DNMs. This implies that recombination events resulting in crossovers are not strongly associated with DNMs. This suggests that the location of mutations is dictated by processes that are more widely distributed over the genome, including methylation at CpG sites, gene conversions (i.e., noncrossover recombination events), or other aspects of the DNA repair system (Seplyarskiy and Sunyaev 2021). Notably, we detected a very strong sex bias in terms of the number of DNMs, with 3.0 times as many mutations in males than in females. This is higher than the 1.2 male-to-female mutation rate ratio in the collared flycatcher but lower than the average male bias of 5.4 times recently estimated in 15 other bird species (range 0.6–13.0; Bergeron et al. 2023). The phenomenon of male-driven mutations is suggested to be caused by a continuous cell division in the male germline after birth, which contrasts the case in females where cell divisions are limited to early life stages (Ellegren and Fridolfsson 1997; Makova and Li 2002). However, as this should apply to any species, the considerable range in the strength of the male-biased germline mutation rate among species (Venn et al. 2014; Smeds et al. 2016; Bergeron et al. 2023) suggests additional factors at play. One possibility is that estimates of the male-biased mutation rate are confounded by age, because studies have found that the number of germline mutations can increase with age and in particular so in males (Kong et al. 2012; Wong et al. 2016). In this study, we have three pairs of males and females of various ages, which enable us to disentangle whether the detected mutational male bias in the great reed warbler was confounded by an age effect. One of the three pairs is highly informative, because the male is much younger (2 years) than the female (>6 years) and still shows more mutations (n = 4) than the female (n = 0; table 1). Thus, our results from the great reed warbler support the view that males have more germline mutations compared with females, independent of age effects. However, further analyses of potential interactions between sex and age are warranted to confirm the strength of male-driven mutation rates.

We obtained a corrected autosomal mutation rate of 7.16 × 10−9 m/s/g in the great reed warbler, providing a second estimate of the mutation rate in birds using three-generation pedigrees. The mutation rate of the great reed warbler is higher than in the collared flycatcher (4.6 × 10−9 m/s/g; Smeds et al. 2016) but still in the same order of magnitude as among this and five other passerine species (range 4.6–7.0 × 10−9 m/s/g; Smeds et al. 2016; Bergeron et al. 2023). Nevertheless, substantial interspecific variation of mutation rates has been revealed: in birds, from 1.0 × 10−9 m/s/g in snowy owl (Bubo scandiacus) to 39.8 × 10−9 m/s/g in lesser rhea (Rhea pennata; Bergeron et al. 2023), and in mammals, from 4.5 × 10−9 m/s/g in the gray wolf (Canis lupus; Koch et al. 2019) to 16.6 × 10−9 m/s/g in the Sumatran orangutan (Pongo abelii; Besenbacher et al. 2019; for data of additional mammals, see Bergeron et al. 2023). A comprehensive comparison of the mutation rates between lineages would require more data on the variability of mutations both within and between species.

The mutation rate is a key parameter in many evolutionary and population genetic analyses. Given the wide range of mutation rate estimates between species, having a species-specific mutation rate estimate is important because it allows rescaling results to real time, for example, in models of demographic histories of specific species. In the great reed warbler, previous studies of its demographic history based on mitochondrial DNA suggest that the species went through a population bottleneck during parts of the LGP ∼18–87 kya (Bensch and Hasselquist 1999; Hansson et al. 2008), when it became subdivided into a western Europe and a Middle East/Asia Minor refugia (Hansson et al. 2008). In the present study, we conducted MSMC analyses to evaluate the demographic history of the great reed warbler based on the whole-genome sequence data from birds from the western (Swedish) and eastern (Turkish) populations. To rescale the results to real time, we used the corrected autosomal mutation rate from this study (i.e., 7.16 × 10−9 m/s/g) and a generation time of 2.44 years also estimated in this study (supplementary table S3, Supplementary Material online). In contrast to some other species that show decreasing Ne after the start of LGP ∼115 kya (e.g., the common cuckoo, Cuculus canorus; Nadachowska-Brzyska et al. 2015) and to the temperature fluctuations during LGP estimated by the oxygen isotope profile (δ18O) in Greenland ice cores (fig. 4; Rasmussen et al. 2014; Seierstad et al. 2014), our analyses of the great reed warbler unveiled a drastic decrease in Ne already 300–500 kya and a fairly constant low Ne before and over the start of the LGP. This may suggest that the habitat availability for the great reed warbler, which is a wetland specialist, declined substantially much earlier than the start of the LGP and that it was not directly affected by the onset of the LGP. Similar analyses of other wetland specialists might shed light on this possibility. Alternatively, our rescaling failed to reflect the true timing of the demographic events. However, recalibrating the drastic decrease of Ne at around 500 kya to the beginning of the LGP would require applying unrealistic assumptions, for example, a generation time of only 1 year and doubling the mutation rate. In addition, the two western and eastern populations that were analyzed here showed different Ne trajectories starting from ∼50 kya, which suggests independent demography and thus reduced gene flow (i.e., population separation; Mather et al. 2020) starting ∼65 kyr after the onset of LGP. These results from the MSMC analysis, which are based on genome-wide nuclear sequence data, conform to the previous studies of mitochondrial sequence data that suggested a split into two refugia populations during the LGP (Bensch and Hasselquist 1999; Hansson et al. 2008). A question for future research is whether mixing of the refugia populations in central Europe during the postglacial expansion (Hansson et al. 2008) may have led to an underestimation of when the western and eastern populations separated, so that the reduction in gene flow could possibly have started closer to the onset of LGP.

In conclusion, we have detected DNMs in the great reed warbler and contributed with the second direct estimate of the mutation rate for birds using whole-genome sequencing data of a three-generation pedigree. With respect to the distribution of DNMs, we found that DNMs were not clustered in specific regions of the chromosomes but locally enriched on CpG sites. Most importantly, we found three times as many DNMs in males compared with in females (independent of age effects), which supports the hypothesis that continuous cell divisions during postnatal spermatogenesis result in male-biased germline mutations. We also applied our estimated mutation rate to rescale demographic events to real time and found that western and eastern great reed warbler populations shared a drastic decrease in Ne already before the onset of LGP and showed independent demographic trajectories (i.e., split) during the second half of LGP.

Materials and Methods

Samples and Sequencing

The great reed warbler is a large Acrocephalid warbler breeding in reed lakes and marshes in Europe and western Asia (Helbig and Seibold 1999; Dyrcz 2020). It is a long-distance migrant that spends the winter in sub-Saharan Africa and returns from the end of April onwards to its wide Eurasian breeding range (Lemke et al. 2013; Koleček et al. 2016; Sjöberg et al. 2021). From our long-term study population of great reed warblers at Lake Kvismaren, southern Central Sweden (59°10ʹ N, 15°24ʹ E; Bensch et al. 1998; Hasselquist 1998; Tarka et al. 2014; Asghar et al. 2015; Hansson et al. 2018), we randomly selected a complete three-generation pedigree, including four grandparents (F0 generation; male: H7-38, V9-73; female: H0-81, H7-41), two parents (F1 generation; male: H3-00; female: H5-17), and six offspring (F2 generation; male: 253, 254, 255, 257, 258; female: 256) (fig. 5; supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online).

Fig. 5.

The three-generation pedigree of great reed warblers (Acrocephalus arundinaceus). Shown are generation (F0, F1, and F2), individual ID code (e.g., H7-38), sex (square, male; circle, female), and cell type (green, diploid somatic; yellow, haploid germline), and the two scenarios of the occurrence and fate of germline mutations in a three-generation pedigree. (A) The first scenario involves germline mutations (e.g., A → C) occurring in one individual (H7-38) of F0 generation, detected in one individual (H3-00) of F1 generation, and then present in several individuals (254, 256, and 257) of F2 generations. (B) The second scenario involves the germline mutations (e.g., A → T) occurring in one individual (H3-00) of F1 generation and detected in one individual (257) of F2 generation.

Genomic DNA was extracted from blood samples stored in SET buffer using a phenol–chloroform protocol (Sambrook et al. 1989). The birds were whole-genome sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 (S4 flowcell, v1 sequencing chemistry; Illumina, CA, USA) using a paired-end (2 × 150 bp) set-up and a targeted ∼50× coverage. Libraries for sequencing were prepared with a TruSeq PCR free (Illumina) protocol using a 350 bp insert size. Sequencing was performed by the SNP&SEQ Technology Platform at Uppsala Genome Center, Uppsala, Sweden.

Detection of DNMs

Details of software and commands are given in supplementary S1, Supplementary Material online. In brief, the sequence reads of each individual were trimmed with trimmomatic version 0.39 (Bolger et al. 2014), mapped to the reference genome assembly of the great reed warbler (Sigeman et al. 2021) using bwa mem version 0.7.17 (Li 2013), and read duplicates were removed with Picard Tools version 2.27.5 (Broad Institute 2019). Then, variants were called with freebayes version 1.3.2 (Garrison and Marth 2012), producing a VCF file. Variants in annotated repeat intervals were removed using vcftools version 0.1.16 (Danecek et al. 2011). Only the biallelic variants were kept and decomposed for complex and multinucleotide variants, using vcftools version 0.1.16 (Danecek et al. 2011) and VT decompose_blocksub version 0.5 (Tan et al. 2015). After indels had been removed using vcffilter from vcflib version 2017-04-04 (Garrison et al. 2022), the SNPs were divided into an autosome and a Z-linked data set, and hard filtering on the quality, strandedness, read placement, and genotype coverage (with -f “QUAL > 30 & SAF > 0 & SAR > 0 & RPR > 0 & RPL > 0” and -g “DP > 9” in vcffilter), respectively, was applied for both data sets. After removing SNPs with missing data using vcftools, we obtained DNM candidates by identifying singletons. With the three-generation pedigree, DNMs can be detected under two scenarios. For DNMs occurring in the germline of F0 individuals, DNMs can be detected in the somatic cells of F1 individuals by identifying singletons among the six individuals of the F0 and F1 generations. Furthermore, these DNMs can be passed down and, thus be detected, in F2 individuals. On the other hand, DNMs occurring in the germline of F1 individuals can be detected in the somatic cells of one F2 individual by identifying singletons across all 12 individuals (fig. 5).

For biallelic variants, some reads tentatively supporting the alternate allele (quantified by the alternative allele observation count-value, AO, in the VCF file) can occur also in individuals that have been called as homozygous for the reference allele. For each DNM candidate detected (i.e., a singleton), we counted AOother, which represents the total AO in the other (5 or 11) individuals. Candidate DNMs with AOother ≥ 1 were discarded, leaving the final set of DNMs. The rationale behind this filtering step was to control for false positive DNMs in regions prone to have mapping errors. However, discarding candidate DNMs with AOother ≥ 1 will lead to exclusion of true DNMs if reads supporting the alternate allele resulted from sequencing errors or mapping errors in other individuals. Using AOother ≥ 2 as a cutoff would have included an additional 14 DNMs detected in F1 individuals and 6 DNMs detected in F2 individuals.

To evaluate whether the DNMs were transmitted to offspring as would be expected from a germline mutation, we counted the number of F2 offspring that inherited a DNM detected in an F1 parent. The transmission probability of an autosomal germline DNM is 0.5, implying an expected transmission distribution with a mean of three for six offspring. In contrast, somatic mutations, which are not inherited, are not expected to be detected in any of the F2 offspring.

Estimating the Mutation Rate

Due to our workflow of filtering, candidate DNMs are identifiable only in certain regions, which could have resulted in an underestimation of the mutation rate if we had used the total length of the genome to calculate the per site mutation rate. To address this, we first calculated the number of callable sites per individual after excluding sites overlapping annotated repeat intervals (Sigeman et al. 2021) and with extreme coverage values (falling outside the 0.5–1.5 × median coverage interval) and next only retained the sites called in all 12 individuals for later analysis. Also, the callable sites were calculated separately for autosomal and sex-linked scaffolds. The mutation rate was calculated by dividing the total number of DNMs by the sum of callable sites and numbers of meiosis (two for autosomes and the Z chromosome in males, ZZ, and one for the single Z chromosome in females, ZW). The calculation gives the mutation rate as the number of DNMs per site per generation.

The mutation rate can further be underestimated by failure to detect DNMs in the callable regions. To estimate the FNR for our pipeline to detect DNMs, we conducted simulations (see supplementary S2, Supplementary material online) by replacing 100 sites with artificial DNMs with known mutation type and randomly allocating them in the bam file of each offspring (F2 generation) using Bamsurgeon version 1.3 (GitHub: https://github.com/adamewing/bamsurgeon; last accessed on October 24, 2022; Ewing et al. 2015). Notably, the locations of simulated DNMs were controlled to avoid the positions of the DNMs detected in the real data. Next, we repeated our analysis from variant calling to the detection of DNMs. The FNR was calculated as the proportion of simulated DNMs that we failed to recover, and this value was used to correct the mutation rate estimates.

Modeling Demographic History Using MSMC Analyses

The great reed warbler has a present breeding range across Eurasia that extends from Spain in the west to Mongolia in the east (Dyrcz 2020). However, previous work based on mitochondrial sequence data suggests that the species went through a population bottleneck and was subdivided into two refugia approximately between 18 and 87 kya (Bensch and Hasselquist 1999; Hansson et al. 2008), one located in western Europe and one in the Middle East/Asia Minor (Hansson et al. 2008). To demonstrate an application of our estimated mutation rates, we investigated the demographic history of two different breeding populations of great reed warblers: Sweden and Turkey. We refer to these populations as the western (Sweden) and eastern (Turkey) populations, respectively. For the western population, we used the sequence data of the four grandparents from the pedigree in this study, and for the eastern population, we used four individuals sampled close to Bafra, Turkey (41°39ʹ N, 36°02ʹ E; unpublished data). Reads were mapped and SNPs were called as previously described (above). Next, we used getStats from msmc-tools (GitHub: https://github.com/stschiff/msmc-tools; last accessed on October 24, 2022) to confirm that all individuals were unrelated. We followed the suggested workflow from the MSMC tutorial (https://github.com/stschiff/msmc-tools/blob/master/msmc-tutorial/guide.md; last visit on September 30, 2022) to prepare the input files and run the analysis (detailed commands in supplementary S3, Supplementary Material online). Basically, we used MSMC2 version 2.1.1 (Schiffels and Wang 2020) to run the Ne estimation with the following set-ups: 1) for each population, a separate run was done using four individuals, and 2) for each individual, a separate run was performed. Specifically, we ran 20 iterations and used a 40-parameter pattern, “1*4 + 12*2 + 24*4 + 1*4 + 1*6 + 1*10”, which spans 144 time-intervals. In addition, we performed 100 bootstrapping for the first set-up (see supplementary S3, Supplementary Material online).

The time of the Ne trajectories was rescaled to real time with the corrected autosomal mutation rate estimated in this study and with an estimate of the generation time of the great reed warbler that we calculated following the approach described in Thompson and Post (2020) and by using survival and reproductive data collected between 1983 and 2019 in the breeding population at Lake Kvismaren (Bensch et al. 1998; Hasselquist 1998; Tarka et al. 2014; Asghar et al. 2015; Hansson et al. 2018). The two key parameters for calculating the generation time are the survival rates and the mean number of daughters of females of different age classes. First-year survival, that is, the survival rate of age class 1 year (between year 0 and 1), was estimated as 0.236 based on data of the return rates of nestlings from the Lake Kvismaren population and the dispersal rate from previous studies (Hansson et al. 2002a, 2002b).The survival rates of age classes 2, 3, … 10 years were estimated from data of females with estimated age using the survfit function from the survival R package (Therneau 2023), which handles data that contain individuals with absent records among years. The mean number of daughters of females of different age classes was estimated from data of the number of offspring of each female each breeding year and, as most offspring are not sexed, by randomly assigning offspring sex as male or female according to the sex ratio (i.e., 51.2% males) calculated from 304 nestlings sexed with molecular methods (Bensch et al. 1999; Westerdahl et al. 2000). This random assignment of offspring sex was repeated 1,000 times, and for each data set, we calculated 1) the mean number of daughters of females of different age classes and 2) the generation time by combining this (i.e., 1) with the survival rates of different age classes. The distribution of generation time estimates was normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk test, W = 1.00, P = 0.64) with a mean (±SE) of 2.44 (±0.001) years (supplementary table S3, Supplementary Material online).

Characterizing DNMs

We characterized the detected DNMs in the following aspects: chromosome position, Ts/Tv ratio, occurrence on CpG sites, location in relation to gene features (intergenic, intron, exon, UTR, and CDS), and parent-of-origin.

As a chromosome-level genome assembly of great reed warbler is yet to be available, we inferred the chromosomal positions of the DNMs on the great tit (Parus major) genome assembly version 1.1 (National Center for Biotechnology Information [NCBI] accession: PRJNA208335). First, we used lastal version 963 (Kiełbasa et al. 2011) to search for all alignments of genomic intervals between the great reed warbler and the great tit. Next, we selected >500 bp alignments that harbor one or more DNMs and had a single match to the genome assembly of the great tit. The last method can fail to infer reliable alignments for some of the DNMs. Therefore, we additionally used blastn version 2.12.0+ (Altschul et al. 1990) to search 2.5, 5, and 10 kb flanking regions of DNMs to the genome assembly of the great tit and retained the hit with the maximum Bit-score. After inferring the chromosomal positions with the “last” and “blast” methods, we assigned the chromosomes with the most frequent assignments across the “last” and all “blast” analyses. The chromosomal positions were obtained by averaging the middle positions of the alignments for both last and blast methods.

We plotted both the actual and the relative position of the DNMs on each of the chromosomes in the great tit assembly. We evaluated the correlation between the number of DNMs and chromosome size (Spearman's rank test) and tested whether the DNMs were randomly distributed along the chromosomes. For the latter analysis, each chromosome was divided into three segments of equal proportion, the number of DNMs in each segment across chromosomes was summed, and a χ2 goodness-of-fit test was performed.

Whether the DNMs are Ts or Tv can be inferred by comparing the DNM and the reference allele, which means that the Ts/Tv ratio could be directly calculated. We used vcftools with --TsTv option to infer the Ts–Tv category of each DNM. To test whether more mutations occurred at CpG sites, we categorized the DNMs into 3-mer types based and centered on their original base and the ±1 bp flanking nucleotides (e.g., a DNM could be in an “ACG” type which is a CpG site or in a “GCT” type which is a non-CpG site). Categorizing the DNMs into 3-mer reflects more clearly their mutation type and allows straightforward comparison between the DNMs on CpG sites versus the other mutation types. Next, we normalized the count of DNMs in each 3-mer type by the total count of corresponding 3-mer type among all callable sites. To account for the situation where the DNM is at the first or last site of callable sites, we also included ±1 bp flanking nucleotides to the callable site intervals.

We used available genome annotations (Sigeman et al. 2021) in bedtools (Quinlan and Hall 2010) to explore the distribution of DNMs in intergenic, genic, intron, exon, UTR, and CDS regions. We tested whether the number of DNMs differed between the following pairs of annotation features: intergenic versus genic regions, exon versus intron, and UTR versus CDS. Here, we used χ2 goodness-of-fit tests, with the expected number of DNMs calculated from the total length (bp) of each feature, using the rstatix R package (Kassambara 2022).

To infer the parent-of-origin of the DNMs, we manually examined the 50 bp and, if necessary, the 600 bp flanking regions of each DNM in IGV (Robinson et al. 2011). A DNM could be traced to a specific parent when it was located on the same read or read-pair as another SNP that distinguished the parents. An informative SNP further needed to be heterozygous in the DNM individual and be absent from one of the parents (i.e., one parent being homozygous for the other allele). In supplementary figures S1 and S2, Supplementary Material online, we give examples of DNMs for which we could and could not trace the parent-of-origin.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at Genome Biology and Evolution online (http://www.gbe.oxfordjournals.org/).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Blood sample collection was done by puncturing the wing vein and granted with the appropriate permissions from the Linköpings Djurförsöksetiska Nämnd (M 45-14 and 17277-18). Sequencing was performed by the SNP&SEQ Technology Platform at Uppsala Genome Center, which is part of National Genomics Infrastructure (NGI) Sweden, and Science for Life Laboratory (SciLifeLab) supported by the Swedish Research Council (and its Council for Research infrastructure, RFI) and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. Bioinformatics analyses were performed on computational infrastructure provided by the Swedish National Infrastructure for Computing (SNIC) at Uppsala Multidisciplinary Center for Advanced Computational Science (UPPMAX). Fieldwork was supported by the Kvismare Bird Observatory (report number: 206) and Lunds Djurskyddsfond (to M.T.). The research was funded by grants from Jörgen Lindström's foundation (to H.Z.), Kungliga Fysiografiska Sällskapet (to H.Z.), the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (advanced grant 742646 to D.H.), and the Swedish Research Council (grants no. 2020-04658 to M.T., 2016-04391 and 2020-03976 to D.H., and 2016-00689 and 2022-04996 to B.H.).

Contributor Information

Hongkai Zhang, Department of Biology, Lund University, Lund, Sweden.

Max Lundberg, Department of Biology, Lund University, Lund, Sweden.

Maja Tarka, Department of Biology, Lund University, Lund, Sweden.

Dennis Hasselquist, Department of Biology, Lund University, Lund, Sweden.

Bengt Hansson, Department of Biology, Lund University, Lund, Sweden.

Author Contributions

H.Z. and B.H. conceptualized the study. D.H., B.H., and M.T. were responsible for the collection of the samples used in the study. H.Z. conducted the analyses with input from M.L. and B.H. H.Z. and B.H. wrote the manuscript with input from M.L., M.T., and D.H.

Data Availability

All sequence data used for this study are accessible under BioProject ID's PRJNA970100 and PRJNA970800.

Literature Cited

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 215:403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asghar M, et al. 2015. Hidden costs of infection: chronic malaria accelerates telomere degradation and senescence in wild birds. Science 347:436–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensch S, Hasselquist D. 1999. Phylogeographic population structure of great reed warblers: an analysis of mtDNA control region sequences. Biol J Linn Soc. 66:171–185. [Google Scholar]

- Bensch S, Hasselquist D, Nielsen B, Hansson B. 1998. Higher fitness for philopatric than for immigrant males in a semi-isolated population of great reed warblers. Evolution 52:877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensch S, Westerdahl H, Hansson B, Hasselquist D. 1999. Do females adjust the sex of their offspring in relation to the breeding sex ratio? J Evol Biol. 12:1104–1109. [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron LA, et al. 2021. The germline mutational process in rhesus macaque and its implications for phylogenetic dating. GigaScience 10:giab029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron LA, et al. 2023. Evolution of the germline mutation rate across vertebrates. Nature 615:285–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besenbacher S, Hvilsom C, Marques-Bonet T, Mailund T, Schierup MH. 2019. Direct estimation of mutations in great apes reconciles phylogenetic dating. Nat Ecol Evol. 3:286–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30:2114–2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CR, et al. 2021. Pedigree-based and phylogenetic methods support surprising patterns of mutation rate and spectrum in the gray mouse lemur. Heredity (Edinb). 127:233–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danecek P, et al. 2011. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 27:2156–2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Maio N, et al. 2021. Mutation rates and selection on synonymous mutations in SARS-CoV-2. Genome Biol Evol. 13:evab087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyrcz A. 2020. Great Reed Warbler (Acrocephalus arundinaceus), version 1.0. In: del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J, Christie DA, de Juana E, editors. Birds of the World. Ithaca (NY): Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 10.2173/bow.grrwar1.01. [DOI]

- Ellegren H, Fridolfsson A-K. 1997. Male–driven evolution of DNA sequences in birds. Nat Genet. 17:182–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing AD, et al. 2015. Combining tumor genome simulation with crowdsourcing to benchmark somatic single-nucleotide-variant detection. Nat Methods. 12:623–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre-Walker A, Keightley PD. 2007. The distribution of fitness effects of new mutations. Nat Rev Genet. 8:610–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng C, et al. 2017. Moderate nucleotide diversity in the Atlantic herring is associated with a low mutation rate. eLife 6:e23907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanillas E, Welch JJ, Thomas JA, Bromham L. 2007. The influence of body size and net diversification rate on molecular evolution during the radiation of animal phyla. BMC Evol Biol. 7:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z, et al. 2019. Overlooked roles of DNA damage and maternal age in generating human germline mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 116:9491–9500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison E, Kronenberg ZN, Dawson ET, Pedersen BS, Prins P. 2022. A spectrum of free software tools for processing the VCF variant call format: vcflib, bio-vcf, cyvcf2, hts-nim and slivar. PLoS Comput Biol. 18:e1009123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison E, Marth G. 2012. Haplotype-based variant detection from short-read sequencing. Available from: http://arxiv.org/abs/1207.3907

- Glémin S. 2003. How are deleterious mutations purged? Drift versus nonrandom mating. Evolution 57:2678–2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldane JB. 1935. The rate of spontaneous mutation of a human gene. J Genet. 83:235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldane J. 1946. The mutation rate of the gene for haemophilia, and its segregation ratios in males and females. Ann Eugen. 13:262–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halligan DL, Keightley PD. 2009. Spontaneous mutation accumulation studies in evolutionary genetics. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 40:151–172. [Google Scholar]

- Hansson B, et al. 2018. Contrasting results from GWAS and QTL mapping on wing length in great reed warblers. Mol Ecol Resour. 18:867–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson B, Bensch S, Hasselquist D. 2002a. Predictors of natal dispersal in great reed warblers: results from small and large census areas. J Avian Biol. 33:311–314. [Google Scholar]

- Hansson B, Bensch S, Hasselquist D, Nielsen B. 2002b. Restricted dispersal in a long-distance migrant bird with patchy distribution, the great reed warbler. Oecologia 130:536–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson B, Hasselquist D, Tarka M, Zehtindjiev P, Bensch S. 2008. Postglacial colonisation patterns and the role of isolation and expansion in driving diversification in a passerine bird. PLoS One 3:e2794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselquist D. 1998. Polygyny in great reed warblers: a long-term study of factors contributing to male fitness. Ecology 79:2376–2390. [Google Scholar]

- Helbig AJ, Seibold I. 1999. Molecular phylogeny of Palearctic–African Acrocephalus and Hippolais warblers (Aves: Sylviidae). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 11:246–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joron M, et al. 2011. Chromosomal rearrangements maintain a polymorphic supergene controlling butterfly mimicry. Nature 477:203–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya T, et al. 2012. A trans-species missense SNP in Amhr2 is associated with sex determination in the tiger pufferfish, Takifugu rubripes (Fugu). PLoS Genet. 8:e1002798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassambara A. 2022. rstatix: pipe-friendly framework for basic statistical tests. R package version 0.7.1. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rstatix

- Keightley PD, Ness RW, Halligan DL, Haddrill PR. 2014. Estimation of the spontaneous mutation rate per nucleotide site in a Drosophila melanogaster full-sib family. Genetics 196:313–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler MD, et al. 2020. De novo mutations across 1,465 diverse genomes reveal mutational insights and reductions in the Amish founder population. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 117:2560–2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiełbasa SM, Wan R, Sato K, Horton P, Frith MC. 2011. Adaptive seeds tame genomic sequence comparison. Genome Res. 21:487–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. 1980. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol. 16:111–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch EM, et al. 2019. De novo mutation rate estimation in wolves of known pedigree. Mol Biol Evol. 36:2536–2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koleček J, et al. 2016. Cross-continental migratory connectivity and spatiotemporal migratory patterns in the great reed warbler. J Avian Biol. 47:756–767. [Google Scholar]

- Kondrashov AS. 2003. Direct estimates of human per nucleotide mutation rates at 20 loci causing Mendelian diseases. Hum Mutat. 21:12–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong A, et al. 2012. Rate of de novo mutations and the importance of father's age to disease risk. Nature 488:471–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamichhaney S, et al. 2016. Structural genomic changes underlie alternative reproductive strategies in the ruff (Philomachus pugnax). Nat Genet. 48:84–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke HW, et al. 2013. Annual cycle and migration strategies of a trans-Saharan migratory songbird: a geolocator study in the great reed warbler. PLoS One 8:e79209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. 2013. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. ArXiv Prepr. ArXiv13033997.

- Li W-H, Yi S, Makova K. 2002. Male-driven evolution. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 12:650–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewe L, Hill WG. 2010. The population genetics of mutations: good, bad and indifferent. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 365:1153–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, et al. 2016. Genetic drift, selection and the evolution of the mutation rate. Nat Rev Genet. 17:704–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makova KD, Li W-H. 2002. Strong male-driven evolution of DNA sequences in humans and apes. Nature 416:624–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather N, Traves SM, Ho SYW. 2020. A practical introduction to sequentially Markovian coalescent methods for estimating demographic history from genomic data. Ecol Evol. 10:579–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier J, Duret L. 2004. Recombination drives the evolution of GC-content in the human genome. Mol Biol Evol. 21:984–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata T, Hayashida H, Kuma K, Mitsuyasu K, Yasunaga T. 1987. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on quantitative biology. Vol. 52. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. p. 863–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachman MW, Crowell SL. 2000. Estimate of the mutation rate per nucleotide in humans. Genetics 156:297–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadachowska-Brzyska K, Li C, Smeds L, Zhang G, Ellegren H. 2015. Temporal dynamics of avian populations during Pleistocene revealed by whole-genome sequences. Curr Biol. 25:1375–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessia E, et al. 2012. Evidence for widespread GC-biased gene conversion in eukaryotes. Genome Biol Evol. 4:675–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broad Institute . 2019. “Picard Toolkit”, Broad institute, GitHub repository. Picard Toolkit.

- Ponnikas S, Sigeman H, Lundberg M, Hansson B. 2022. Extreme variation in recombination rate and genetic diversity along the Sylvioidea neo-sex chromosome. Mol Ecol. 31:3566–3583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan AR, Hall IM. 2010. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26:841–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen SO, et al. 2014. A stratigraphic framework for abrupt climatic changes during the last glacial period based on three synchronized Greenland ice-core records: refining and extending the INTIMATE event stratigraphy. Quat Sci Rev. 106:14–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rees DC, Williams TN, Gladwin MT. 2010. Sickle-cell disease. Lancet 376:2018–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JT, et al. 2011. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 29:24–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffels S, Wang K. 2020. Statistical population genomics. New York: Humana. p. 147–165. [Google Scholar]

- Schrider DR, Houle D, Lynch M, Hahn MW. 2013. Rates and genomic consequences of spontaneous mutational events in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 194:937–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seierstad IK, et al. 2014. Consistently dated records from the Greenland GRIP, GISP2 and NGRIP ice cores for the past 104 ka reveal regional millennial-scale δ18O gradients with possible Heinrich event imprint. Quat Sci Rev. 106:29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Seplyarskiy VB, Sunyaev S. 2021. The origin of human mutation in light of genomic data. Nat Rev Genet. 22:672–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimmin LC, Chang BH-J, Li W-H. 1993. Male-driven evolution of DNA sequences. Nature 362:745–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigeman H, et al. 2021. Avian neo-sex chromosomes reveal dynamics of recombination suppression and W degeneration. Mol Biol Evol. 38:5275–5291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöberg S, et al. 2021. Extreme altitudes during diurnal flights in a nocturnal songbird migrant. Science 372:646–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeds L, Qvarnström A, Ellegren H. 2016. Direct estimate of the rate of germline mutation in a bird. Genome Res. 26:1211–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer CCA, et al. 2006. The influence of recombination on human genetic diversity. PLoS Genet. 2:e148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltzfus A, Norris RW. 2016. On the causes of evolutionary transition: transversion bias. Mol Biol Evol. 33:595–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan A, Abecasis GR, Kang HM. 2015. Unified representation of genetic variants. Bioinformatics 31:2202–2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarka M, Åkesson M, Hasselquist D, Hansson B. 2014. Intralocus sexual conflict over wing length in a wild migratory bird. Am Nat. 183:62–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therneau TM. 2023. A Package for Survival Analysis in R. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival

- Thomas GWC, et al. 2018. Reproductive longevity predicts mutation rates in primates. Curr Biol. 28:3193–3197.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JN, Post E. 2020. Population ecology. Encycl. Br. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/science/population-ecology

- Venn O, et al. 2014. Strong male bias drives germline mutation in chimpanzees. Science 344:1272–1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang Y, Wang Z, Zhang X, Yang S. 2013. A missense mutation in CHS1, a TIR-NB protein, induces chilling sensitivity in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 75:553–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerdahl H, Bensch S, Hansson B, Hasselquist D, Von Schantz T. 2000. Brood sex ratios, female harem status and resources for nestling provisioning in the great reed warbler (Acrocephalus arundinaceus). Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 47:312–318. [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock MC, Agrawal AF. 2009. Purging the genome with sexual selection: reducing mutation load through selection on males. Evolution 63:569–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong WSW, et al. 2016. New observations on maternal age effect on germline de novo mutations. Nat Commun. 7:10486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder AD, Tiley GP. 2021. The challenge and promise of estimating the de novo mutation rate from whole-genome comparisons among closely related individuals. Mol Ecol. 30:6087–6100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Tao W, Han J-DJ. 2022. 3D chromatin structure changes during spermatogenesis and oogenesis. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 20:2434–2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All sequence data used for this study are accessible under BioProject ID's PRJNA970100 and PRJNA970800.