Abstract

Aims

Guidelines on the management of atrial fibrillation (AF) have evolved significantly during the past two decades, but the concurrent developments in real-life management and prognosis of AF are unknown. We assessed trends in the treatment and outcomes of patients with incident AF between 2007 and 2017.

Methods and results

The registry-based nationwide FinACAF (Finnish AntiCoagulation in Atrial Fibrillation) cohort covers all patients with AF in Finland from all levels of care. We determined the proportion of patients who were treated with oral anticoagulants (OACs) or rhythm control therapies, experienced an ischaemic stroke or bleeding event requiring hospitalization, or died within 1-year follow-up after AF diagnosis. We identified 206 909 patients (mean age 72.6 years) with incident AF. During the study period, use of OACs increased from 43.6 to 76.3%, and the increase was most evident in patients with at least moderate stroke risk. One-year mortality decreased from 13.3 to 10.6%, and the ischaemic stroke rate from 5.3 to 2.2%. The prognosis especially improved in patients over 75 years of age. Concurrently, a small increase in major bleeding events was observed. Use of catheter ablation increased continuously over the study period, but use of other rhythm-control therapies decreased after 2013.

Conclusion

Stroke prevention with OACs in patients with incident AF improved considerably from 2007 to 2017 in Finland. This development was accompanied by decreasing 1-year mortality and the reduction of the ischaemic stroke rate by more than half, particularly among elderly patients, whereas there was only slight increase in severe bleeding events.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Trends, Treatment, Outcomes, Oral anticoagulant therapy, Ischemic stroke, Mortality

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia, with an overall prevalence as high as 4.1% in Finland.1,2 Due to its rising incidence, AF imposes an increasing burden on the population and healthcare systems, largely driven by the long-term disability and mortality associated with ischaemic strokes.1,3,4 Stroke prevention with oral anticoagulants (OACs), either with vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), is the cornerstone of contemporary treatment of AF. Additionally, a variety of rhythm- and rate-control therapies are often needed to relieve symptoms related to AF.5

During the past two decades, active research has led to major developments in stroke-risk stratification and treatment modalities for AF, which have been rapidly included in clinical practice guidelines.6–8 There is, however, limited information regarding the extent to which the increased knowledge and guideline changes have been integrated into the real-life management of AF and whether the developments in guidelines have been accompanied by improved outcomes. Therefore, to assess these treatment and outcome trends, we conducted a nationwide descriptive cohort study covering all AF patients from 2007 to 2017 in Finland.

Methods

Study population

The Finnish AntiCoagulation in Atrial Fibrillation (FinACAF) Study (ClinicalTrials Identifier: NCT04645537; ENCePP Identifier: EUPAS29845) is a nationwide retrospective cohort study that includes all patients with a recorded AF diagnosis in Finland from 2004 to 2018.9 Patients were identified using all the available national healthcare registers (hospitalizations and outpatient specialist visits: HILMO; primary healthcare: AvoHILMO; and National Reimbursement Register upheld by Social Insurance Institute: KELA). The inclusion criterion for the cohort was an International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis code of I48 (including atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter, together referred to as AF) recorded between 2004 and 2018 and a cohort entry on the date of the first recorded AF diagnosis. The exclusion criteria were permanent emigration abroad before 31 December 2018 and age <20 years at AF diagnosis. Follow-up continued until death or 31 December 2018, whichever occurred first. The current sub-study was conducted within a cohort of patients with incident AF between 2007 and 2018, which was established in previous studies of the FinACAF cohort.10,11 For this cohort, to include only patients with newly diagnosed AF, a washout period was applied by excluding those with a recorded AF diagnosis from 2004 to 2006. Additionally, to ensure capturing the true initiation of OAC therapy and the exclusion of patients with prior AF, those with a filled OAC prescription from 2004 to 2006 or within a year prior to the first AF diagnosis were excluded. Patients entering the cohort during 2018 had <1 year of follow-up and were therefore discarded from the analyses. In the analyses of the use of catheter ablation, patients entering the cohort before the introduction of AF specific ablation codes in 2010 were excluded. The patient collection process is summarized in Supplementary material online, Figure S1, and the codes used for the baseline comorbidities are summarized in Supplementary material online, Table S1.

Treatment and outcome measures

Treatments and outcomes were measured as the proportion of patients with events of interest within the first year after AF diagnosis. We measured the proportion of patients initiated on OAC (warfarin, apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, or rivaroxaban) therapy. Additionally, we calculated the share of DOAC initiations of all OAC initiations each year. As an indicator of the pursuit of rhythm-control strategy, we measured the share of patients receiving any antiarrhythmic therapy (AAT) within the first year of follow-up, including recorded cardioversions [Nordic Classification of Surgical Procedure (NCSP) codes: TPF20, WVA50, WX904], catheter ablations (NCSP codes: TPF44, TPF45, TPF46), and filled AAD prescriptions (ATC code C01B antiarrhythmics class I and III, plus ATC code C07AA07 sotalol). Thereafter, we separately analysed the proportions of patients with filled AAD prescriptions, as well as those who underwent cardioversion or catheter ablation procedures.

Similarly, as outcome events of interest, we determined the rates of death and ischaemic strokes, as well as gastrointestinal, intracranial, or any severe bleeding within 1 year of follow-up after the AF diagnosis date separately for each cohort entry year. In patients without prior events of interest, the event was considered to occur on the first recorded diagnosis code. In patients with prior events of interest, the event was considered to occur in the case of a new hospitalization with the event code as the main diagnosis when the event occurred at least 90 days after the prior event, which had occurred before cohort entry. Only outcome diagnoses from the aforementioned HILMO hospital register were included to ensure that the event of interest was truly major and clinically relevant (Supplementary material online, Table S1). Dates of death were retrieved from the National Death Register.

Study ethics

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of Helsinki University, Helsinki, Finland (nr. 15/2017), and granted research permission from the Helsinki University Hospital (HUS/46/2018). Respective permissions were obtained from the Finnish register holders (KELA 138/522/2018; THL 2101/5.05.00/2018; Population Register Centre VRK/1291/2019-3; Statistics Finland TK-53-1713-18/u1281; and Tax Register VH/874/07.01.03/2019). Patients’ identification numbers were pseudonymized, and the research group received individualized but unidentifiable data. Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective registry nature of the study. The study conforms to the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2013.

Statistical analysis

A linear-by-linear χ2 test was used to assess the correlation between year of AF diagnosis and categorical variables, and the Spearman's correlation test was used to analyse continuous variables. The presence of linear temporal trends in the treatment and outcome measures was assessed first, visually and, subsequently, statistically by computing risk ratios for each cohort entry year using the Poisson regression. Additionally, we calculated adjusted risk ratios by fitting the Poisson regression with a CHA2DS2-VASc score, including congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75 years, diabetes, history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack, vascular disease, age 65–74 years, and sex category. Thereafter, we further adjusted the mortality analyses with prior ischaemic stroke during follow-up to assess the impact of possible changes in the rate of ischaemic stroke on all-cause mortality. Statistical analyses were performed with the IBM SPSS Statistics software (Version 27.0, SPSS, Inc., Armonk, NY).

Results

Patient characteristics

We identified 206 909 patients [50.1% female; mean age 72.6 (SD 13.3) years] with incident AF from 2007 to 2017. The annual number of patients with a new AF diagnosis, as well as the mean age of patients and the overall prevalence of comorbidities at the time of AF diagnosis increased steadily during the study decade. Likewise, continuous increases were observed in both the mean HAS-BLED and CHA2DS2-VASc scores (Table1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with incident atrial fibrillation

| Year of diagnosis | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Correlation P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 16 503 | 16 526 | 16 222 | 16 259 | 18 806 | 19 228 | 19 787 | 19 799 | 20 053 | 21 599 | 22 127 | <0.001 |

| Demographics | ||||||||||||

| Mean age, years | 71.6 | 71.7 | 71.8 | 71.8 | 72.4 | 72.6 | 72.5 | 72.9 | 73.2 | 73.5 | 73.8 | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 50.7 | 50.6 | 51.0 | 51.1 | 50.1 | 50.0 | 49.7 | 50.4 | 50.0 | 49.3 | 49.3 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||||||

| Diabetes | 15.5 | 16.8 | 17.6 | 18.7 | 19.2 | 21.0 | 21.9 | 22.8 | 24.2 | 25.0 | 25.4 | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 33.3 | 36.8 | 40.6 | 41.9 | 45.4 | 47.7 | 49.1 | 51.0 | 52.4 | 53.2 | 55.2 | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 16.7 | 17.7 | 18.6 | 19.1 | 17.6 | 17.6 | 17.6 | 17.8 | 17.2 | 16.6 | 16.2 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 65.5 | 68.1 | 69.2 | 71.0 | 72.9 | 74.4 | 74.9 | 75.8 | 77.1 | 77.5 | 78.6 | <0.001 |

| Any vascular disease | 25.8 | 26.3 | 27.9 | 26.8 | 27.2 | 28.6 | 28.1 | 28.9 | 28.6 | 28.3 | 29.2 | <0.001 |

| Prior ischaemic stroke | 5.0 | 6.2 | 7.4 | 8.8 | 10.2 | 11.2 | 11.4 | 11.9 | 12.1 | 12.0 | 12.1 | <0.001 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 7.2 | 7.7 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 7.9 | 8.6 | 8.5 | 9.2 | 9.0 | 9.3 | 9.8 | <0.001 |

| Prior bleeding | 6.8 | 7.7 | 8.6 | 9.8 | 9.7 | 10.4 | 10.6 | 11.4 | 11.9 | 12.7 | 12.8 | <0.001 |

| Abnormal liver function | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | <0.001 |

| Abnormal renal function | 1.9 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 4.4 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 5.3 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 1.9 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 4.8 | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 3.8 | 4.0 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 5.4 | 5.7 | 5.4 | 6.2 | <0.001 |

| Risk scores | ||||||||||||

| Mean CHA2DS2-VASc score | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.6 | <0.001 |

| Mean modified HAS-BLED score | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.7 | <0.001 |

Values denote % unless otherwise specified. CHA2DS2-VASc, congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75 years, diabetes, history of stroke or TIA, vascular disease, age 65–74 years, sex category (female); modified HAS-BLED score, hypertension, abnormal renal or liver function, prior stroke, bleeding history, age > 65 years, alcohol abuse, concomitant antiplatelet/NSAIDs (no labile INR, max score 8).

Treatments

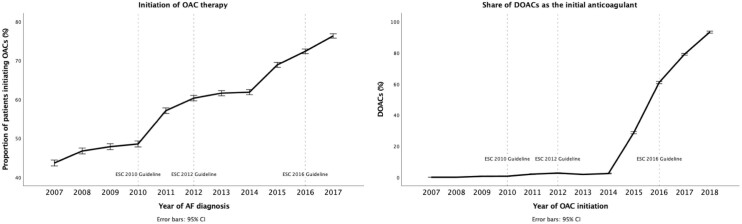

The initiation of OAC therapy increased progressively over the observation period (Figure1, Table2, Supplementary material online, Tables S2 and S3). The increase in OAC use was targeted at patients with a moderate or high risk of stroke and reached an initiation rate of 80% in high-risk patients in 2017 (Supplementary material online, Figure S2). One third of low-risk patients used OAC during the entire study period, but 1 quarter of these low-risk patients filled only 1 OAC prescription (Supplementary material online, Figure S3). A rapid increase in the share of DOACs as the initial anticoagulant was observed from 2015 onward (Figure1).

Figure 1.

Initiation of oral anticoagulation (OAC) within 1-year follow-up after atrial fibrillation diagnosis (left panel) and the share of direct oral anticoagulation (DOAC) as the initial anticoagulant (right panel), with 95% confidence intervals.

Table 2.

Risk ratios of treatment and outcome events within 1-year follow-up according to the year of atrial fibrillation diagnosis

| Year of diagnosis | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | |||||||||||

| OAC therapy | Reference | 1.07 (1.04–1.11) | 1.10 (1.06–1.13) | 1.11 (1.08–1.15) | 1.31 (1.27–1.35) | 1.38 (1.34–1.42) | 1.41 (1.38–1.46) | 1.42 (1.38–1.46) | 1.58 (1.53–1.62) | 1.66 (1.61–1.71) | 1.75 (1.70–1.80) |

| Any AAT | Reference | 1.05 (0.99–1.11) | 1.11 (1.05–1.17) | 1.09 (1.04–1.16) | 1.13 (1.07–1.19) | 1.20 (1.14–1.26) | 1.26 (1.20–1.33) | 1.23 (1.17–1.29) | 1.17 (1.11–1.23) | 1.17 (1.11–1.23) | 1.09 (1.04–1.15) |

| Cardioversion | Reference | 1.10 (1.03–1.18) | 1.25 (1.17–1.34) | 1.21 (1.13–1.30) | 1.32 (1.24–1.41) | 1.45 (1.36–1.55) | 1.60 (1.51–1.70) | 1.52 (1.43–1.62) | 1.44 (1.35–1.53) | 1.43 (1.34–1.52) | 1.36 (1.28–1.45) |

| AADs | Reference | 0.96 (0.88–1.04) | 0.94 (0.86–1.02) | 1.01 (0.93–1.09) | 0.91 (0.83–0.98) | 0.89 (0.82–0.97) | 0.84 (0.78–0.92) | 0.84 (0.78–0.92) | 0.76 (0.69–0.82) | 0.74 (0.68–0.81) | 0.71 (0.65–0.77) |

| Catheter ablation | N/A | N/A | N/A | Reference | 2.92 (1.80–4.76) | 4.51 (2.83–7.19) | 6.30 (4.00–9.93) | 7.82 (4.99–12.26) | 8.57 (5.48–13.41) | 11.58 (7.45–13.41) | 9.87 (6.33–15.37) |

| Outcomes | |||||||||||

| Death | Reference | 0.97 (0.91–1.03) | 0.96 (0.91–1.02 | 0.96 (0.91–1.02) | 0.86 (0.81–0.91) | 0.86 (0.81–0.91) | 0.82 (0.77–0.87) | 0.85 (0.80–0.90) | 0.82 (0.78–0.87) | 0.81 (0.76–0.86) | 0.80 (0.75–0.85) |

| Ischaemic stroke | Reference | 0.78 (0.70–0.86) | 0.71 (0.64–0.79) | 0.72 (0.65–0.80) | 0.59 (0.53–0.66) | 0.48 (0.43–0.53) | 0.46 (0.41–0.51) | 0.41 (0.37–0.46) | 0.41 (0.37–0.46) | 0.41 (0.37–0.46) | 0.42 (0.38–0.47) |

| Any bleeding | Reference | 1.01 (0.89–1.14) | 1.02 (0.90–1.16) | 1.06 (0.94–1.20) | 1.04 (0.92–1.17) | 1.12 (1.00–1.26) | 1.04 (0.92–1.17) | 1.20 (1.07–1.35) | 1.27 (1.14–1.43) | 1.32 (1.18–1.48) | 1.31 (1.17–1.47) |

| GI bleeding | Reference | 0.93 (0.79–1.10) | 1.00 (0.85–1.18) | 1.09 (0.92–1.28) | 0.89 (0.75–1.05) | 0.99 (0.85–1.17) | 0.86 (0.73–1.02) | 1.05 (0.90–1.17) | 1.02 (0.87–1.19) | 1.18 (1.02–1.37) | 1.01 (0.87–1.18) |

| IC bleeding | Reference | 0.99 (0.80–1.24) | 1.04 (0.83–1.29) | 1.05 (0.85–1.31) | 1.10 (0.90–1.36) | 1.20 (0.98–1.47) | 1.12 (0.91–1.37) | 1.19 (0.98–1.46) | 1.27 (1.04–1.54) | 1.15 (0.94–1.41) | 1.05 (0.86–1.28) |

Risk ratios estimated with Poisson regression. Ninety-five % confidence intervals in parenthesis. AAD, antiarrhythmic drugs; AAT antiarrhythmic therapy; GI, gastrointestinal; IC, intracranial; OAC, oral anticoagulant.

Nonlinear temporal trends were observed in the use of rhythm-control therapies. The use of any AAT increased until 2013, but thereafter, AAT use showed a decreasing trend (Table2, Supplementary material online, Tables S2 and S3, Supplementary material online, Figure S4). This change was driven mainly by the more infrequent use of cardioversions, especially among patients over 65 years of age (Supplementary material online, Figure S5). A decreasing trend in the use of AADs was observed during the entire study period while the proportion of patients undergoing catheter ablation during the first year of AF increased steadily after 2010 (Table2, Supplementary materials online, Tables S2 and S3, Supplementary material online, Figure S4).

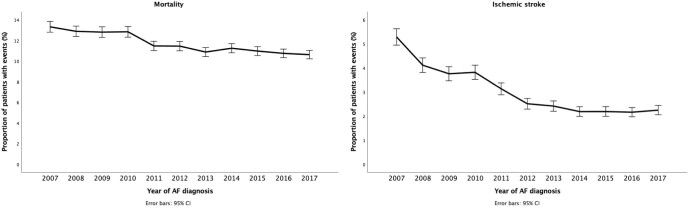

Outcomes

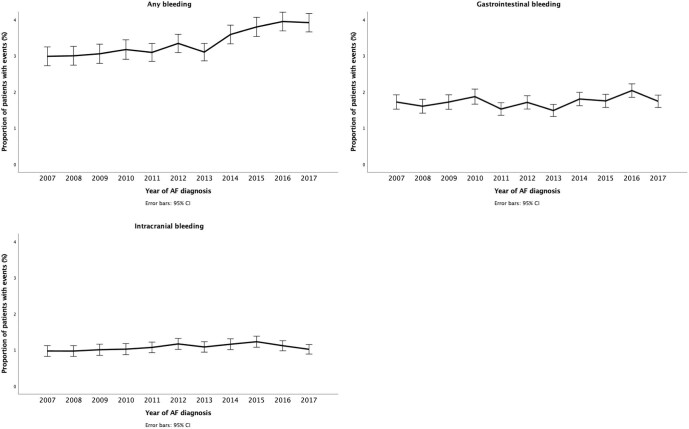

Decreasing trends were observed for mortality and the occurrence of ischaemic stroke within the year after AF diagnosis in both the adjusted and adjusted analyses (Table2, Supplementary material online, Tables S2 and S3, Figure 2). The decreases in mortality and ischaemic stroke rates were most evident among patients aged over 75 years (Supplementary material online, Figure S6). On the other hand, a small concomitant increase in the rate of any bleeding events was observed during the study period but not in the rates of gastrointestinal bleeding and intracranial bleeding (Table2, Supplementary material online, Tables S2 and S3, and Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Mortality (left panel) and ischaemic stroke (right panel) within 1-year follow-up after atrial fibrillation diagnosis, with 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 3.

Bleeding events within 1-year follow-up after atrial fibrillation diagnosis, with 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

This nationwide study documented major temporal changes in the treatment and outcomes of patients with incident AF in Finland from 2007 to 2017. Stroke prevention with OACs increased continuously during the study period, and the rapid adoption of DOACs as the initial anticoagulant was observed from 2015 onward. The increase in OAC use was accompanied by considerable reductions in mortality and ischaemic stroke rates, as well as a marginal increase in bleeding events.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study describing temporal trends in AF treatments and outcomes in a nationwide study sample covering all patients with AF from all levels of care.9 Previous studies on this topic may have been prone to selection and information biases due to the selected patient populations and the inclusion of only hospital-level data.12,13 Moreover, patients treated solely in primary care are typically older high-risk individuals, and the lack of primary-care data may significantly compromise the general interpretation of these findings. Importantly, the observation period in most previous studies did not cover the DOAC era.12,14 Therefore, the findings of the current study substantially increase our understanding of the real-life implementation of the clinical practice guidelines and concomitant changes in the prognosis for AF on a nationwide level.

The underuse of OAC therapy was common in the beginning of our study period, which is in agreement with reports from the early 2000s, when less than half of high-risk patients were using OACs.12,15 After the introduction of the CHADS2 score into the AHA/ACC/ESC Guidelines in 2006, a continuous increase in OAC coverage was observed, in concordance with trends from several other countries.12 After the introduction of the CHA2DS2-VASc score into the 2010 ESC Guidelines to broaden the use of anticoagulation, especially in the age 65–75 age group, the increase in OAC use accelerated and became concentrated in patients with a moderate or high risk of ischaemic stroke, and up to 80% of high-risk patients were using OAC in 2017. These findings show that the guideline recommendations for OAC therapy were implemented into clinical practice relatively quickly, especially when considering that patients treated solely in primary care were also included in our study. The observed OAC coverage in 2017 seems favourable when compared with a systematic review of stroke prevention in AF cases reporting that only 50–70% of patients at a high stroke risk were treated with OACs during the same time period.12 DOACs were favoured over VKA in the 2012 ESC guidelines, and thus, the emergence of DOACs into the mainstream of stroke prevention in Finland seems somewhat late and was hastened only after a number of decisions raising reimbursement rates for DOACs in patients with AF from 2013 to 2015 in Finland.6 One alarming observation was that almost 30% of low-risk patients received OACs, with no decreasing trend over time, although missing information on existing stroke risk factors in our data may have contributed to this figure. This finding is, however, in accordance with a previous report from the early 2000s showing that the futile use of OAC was common, especially in middle-aged men with AF.16 Nevertheless, 1 quarter of these low-risk OAC initiators filled only 1 prescription, likely due to cardioversion or another temporary indication for anticoagulation.

The overall use of rhythm-control therapies reached its peak in 2013, with a decreasing trend thereafter. This trend was largely driven by the decreasing use of cardioversion in elderly patients. Varying trends regarding the utilisation of the rhythm-control strategy have also been described in earlier studies assessing patterns in AF treatment.17–19 In the early 2000s, the AFFIRM and RACE trials observed no outcome benefits from rhythm control as compared with the rate-control strategy, and subsequently, decreasing trends regarding the use of cardioversion were reported.18,20,21 Thereafter, in 2010, European Society of Cardiology guidelines recommended rate control as the initial approach in elderly AF patients with minor symptoms, particularly in the presence of comorbidities that would hamper the success of the rhythm-control strategy.8 This approach was also endorsed by the national guidelines on AF management published in 2011.22 Indeed, the decreasing use of AATs in patients older than 65 years of age after 2013 is likely due to the implementation of these guidelines in the aging patient population, with an increasing prevalence of comorbidities. On the other hand, we observed a clear increase in the use of catheter ablation during the first year after AF diagnosis, which is in concordance with trends in other countries and reflects the mounting evidence regarding the efficacy of the procedure, as well as technological advances and increasing availability, during the study period.7,8,19,23 Although the proportion of patients receiving rhythm control therapies decreased toward the end of our study period, due to the increasing number of patients with incident AF, the number of treated patients remained unchanged, indicating that the healthcare resources used for the maintenance of sinus rhythm have not meaningfully changed during the last years of our observation period (Supplementary material online, Table S2).

The prognosis for patients with AF seems to have improved dramatically in Finland during the study period. Indeed, notwithstanding the rising age and baseline risk scores of the patients with newly diagnosed AF, their 1-year mortality decreased by 20%, and their ischaemic stroke risk was more than halved. The improvements in prognosis were most profound among elderly patients, that is, those over 75 years of age. These findings are likely, at least in part, explained by the increased use of OAC therapy among the high-risk patients. The decline in the mortality risk estimates attenuated, but remained clearly significant, after controlling for ischaemic stroke events during follow-up, indicating that the decrease in the all-cause mortality is partly, but not entirely, mediated by the reduction in ischaemic stroke rate (Supplementary material online, Table S3). Moreover, the treatment of other cardiovascular comorbidities in patients with AF has most likely improved concurrently. Furthermore, improvements in diagnostics may have led to earlier detection of AF, allowing for earlier initiation of stroke prevention and other interventions endorsed by the clinical practice guidelines.24 The findings regarding an improved prognosis for AF patients are in line with the previous literature.25–28 Interestingly, since the rapid adoption of DOACs in 2015, the risk of ischaemic stroke has remained static. Importantly, despite rising bleeding risk scores and the higher use of OAC therapy, only a marginal increase in bleeding events was observed, with no significant increase in intracranial bleeds, suggesting a clear net benefit for increased OAC utilisation.

The most important limitations of our study are related to its retrospective registry-based study design. Thus, our results represent temporal associations, not necessarily causal relationships between patient characteristics, treatments, and outcomes. Additionally, since the ICD-10 codes specifying AF subtypes were implemented into clinical practice in Finland only after our observation period, we were unable to distinguish patients with different AF subtypes or atrial flutter in our study cohort.29 This limits especially the interpretation of the trends in the use of rhythm control therapies. Moreover, information bias may be present due to unmeasured or inappropriately recorded data, although the healthcare registries used are well-validated and have relatively high diagnostic accuracy, especially regarding cardiovascular diseases.30,31 Increasing trends regarding baseline comorbidities may be partly related to developments in diagnostics, as well as differences in the available timespan of the medical records prior to AF diagnosis. A major strength of our study is the complete nationwide study sample covering all patients diagnosed with AF in Finland from all levels of care. The used Finnish national healthcare registers are mandatory and, therefore, provide virtually complete data on healthcare visits and filled prescriptions.

In conclusion, this retrospective cohort study documented that the utilisation of OAC therapy in patients with newly diagnosed AF has improved considerably between 2007 and 2017 in Finland. This development in stroke prevention has been accompanied by an improved prognosis in terms of decreasing 1-year mortality and ischaemic stroke rates, especially among elderly patients. Furthermore, the increase in OAC use seems not to have resulted in a meaningful increase in adverse bleeding events.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Konsta Teppo, Heart Centre, Turku University Hospital and University of Turku, Turku, Finland.

K E Juhani Airaksinen, Heart Centre, Turku University Hospital and University of Turku, Turku, Finland.

Jussi Jaakkola, Heart Centre, Turku University Hospital and University of Turku, Turku, Finland.

Olli Halminen, Department of Industrial Engineering and Management, Aalto University, Espoo, Finland.

Miika Linna, Department of Industrial Engineering and Management, Aalto University, Espoo, Finland; University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio, Finland.

Jari Haukka, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland.

Jukka Putaala, Department of Neurology, Helsinki University Hospital, and University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland.

Pirjo Mustonen, Heart Centre, Turku University Hospital and University of Turku, Turku, Finland.

Janne Kinnunen, Department of Neurology, Helsinki University Hospital, and University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland.

Juha Hartikainen, University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio, Finland; Heart Centre, Kuopio University Hospital, Kuopio, Finland.

Aapo L Aro, Heart and Lung Centre, Helsinki University Hospital and University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland.

Mika Lehto, Heart and Lung Centre, Helsinki University Hospital and University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland; Jorvi Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine, Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District, Espoo, Finland.

Funding

This work was supported by the Aarne Koskelo Foundation, The Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research, and Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District research fund (TYH2019309).

Conflict of interest

K.T.: The Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research. J.J.: none. O.H.: none. J.K.: none. J.P.: Dr Putaala reports personal fees from Boehringer-Ingelheim, personal fees and other from Bayer, grants and personal fees from BMS-Pfizer, personal fees from Portola, other from Amgen, personal fees from Herantis Pharma, personal fees from Terve Media, other from Vital Signum, personal fees from Abbott, outside the submitted work. P.M.: Consultant: Roche, BMS-Pfizer-alliance, Novartis Finland, Boehringer Ingelheim, MSD Finland. J.H.: Consultant: Research Janssen R&D; Speaker: Bayer Finland. M.L.: Speaker: BMSPfizer-alliance, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim. J.H.: Research grants: The Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research, EU Horizon 2020, EU FP7. Advisory Board Member: BMS-Pfizer-alliance, Novo Nordisk, Amgen. Speaker: Cardiome, Bayer. K.E.J.A.: Research grants: The Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research; Speaker: Bayer, Pfizer and Boehringer-Ingelheim. Member in the advisory boards: Bayer, Pfizer and AstraZeneca. M.L.: Consultant: BMS-Pfizer-alliance, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and MSD; Speaker: BMS-Pfizer- alliance, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, MSD, Terve Media and Orion Pharma. Research grants: Aarne Koskelo Foundation, The Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research, and Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District research fund, Boehringer-Ingelheim. A.L.A.: Research grants: Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research; Speaker: Abbott, Johnson&Johnson, Sanofi, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim.

Data availability

Because of the sensitive nature of the data collected for this study, requests to access the dataset from qualified researchers trained in human subject confidentiality protocols may be sent to the Finnish national register holders (KELA, Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare, Population Register Center and Tax Register) through Findata (https://findata.fi/en/).

References

- 1. Wang L, Ze F, Li J, Mi L, Han B, Niu Het al. Trends of global burden of atrial fibrillation/flutter from Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Heart 2021;107:881–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lehto M, Haukka J, Aro A, Halminen O, Putaala J, Linna Met al. Comprehensive nationwide incidence and prevalence trends of atrial fibrillation in Finland. Open Heart 2022;9:e002140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ball J, Carrington MJ, McMurray JJV, Stewart S.. Atrial fibrillation: profile and burden of an evolving epidemic in the 21st century. Int J Cardiol.2013;167:1807–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dai H, Zhang Q, Much AA, Maor E, Segev A, Beinart Ret al. Global, regional, and national prevalence, incidence, mortality, and risk factors for atrial fibrillation, 1990–2017: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2021;7:574–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomström-Lundqvist Cet al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2021;42:546–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. John Camm A, Lip GYH, Caterina R de, Savelieva I, Atar D, Hohnloser SHet al. 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2012;33:1385–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, Ahlsson A, Atar D, Casadei Bet al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J.2016;37:2893–2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GYH, Schotten, U, Savelieva, I, Ernst, Set al. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the task force for the management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2010;31:2369–2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lehto M, Halminen O, Mustonen P, Putaala J, Linna M, Kinnunen Jet al. The nationwide Finnish anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation (FinACAF): study rationale, design, and patient characteristics. Eur J Epidemiol 2022;37:95–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jaakkola J, Teppo K, Biancari F, Halminen O, Putaala J, Mustonen Pet al. The effect of mental health conditions on the use of oral anticoagulation therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation: the FinACAF Study. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2021.8:269–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Teppo K, Jaakkola J, Airaksinen KEJ, Biancari F, Halminen O, Putaala Jet al. Mental health conditions and adherence to direct oral anticoagulants in patients with incident atrial fibrillation: a nationwide cohort study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2022;74:88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lowres N, Giskes K, Hespe C, Freedman B.. Reducing stroke risk in atrial fibrillation: adherence to guidelines has improved, but patient persistence with anticoagulant therapy remains suboptimal. Korean Circ J 2019;49:883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pilote L, Eisenberg MJ, Essebag V, JV Tu, Humphries KH, Leung Yinko SSLet al. Temporal trends in medication use and outcomes in atrial fibrillation. Can J Cardiol 2013;29:1241–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Collet JP, Thiele H, Barbato E, Bauersachs J, Dendale P, Edvardsen Tet al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Palomäki A, Mustonen P, Hartikainen JEK, Nuotio I, Kiviniemi T, Ylitalo Aet al. Underuse of anticoagulation in stroke patients with atrial fibrillation - the FibStroke Study. Eur J Neurol 2016;23:133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bah A, Nuotio I, Palomäki A, Mustonen P, Kiviniemi T, Ylitalo Aet al. Inadequate oral anticoagulation with warfarin in women with cerebrovascular event and history of atrial fibrillation: the FibStroke study. Ann Med 2021;53:287–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bezabhe WM, Bereznicki LR, Radford J, Salahudeen MS, Garrahy E, Wimmer BCet al. Ten-year trends in prescribing of antiarrhythmic drugs in Australian primary care patients with atrial fibrillation. Intern Med J 2021;51:1732–1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Alegret JM, Viñolas X, Romero-Menor C, Pons S, Villuendas R, Calvo Net al. Trends in the use of electrical cardioversion for atrial fibrillation: influence of major trials and guidelines on clinical practice. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 2012;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hosseini SM, Rozen G, Saleh A, Vaid J, Biton Y, Moazzami Ket al. Catheter ablation for cardiac arrhythmias: utilization and in-hospital complications, 2000 to 2013. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2017;3:1240–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van Gelder IC, Hagens VE, Bosker HA, Kingma JH, Kamp O, Kingma Tet al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with recurrent persistent atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1834–1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1825–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Duodecimin Suomalaisen Lääkäriseuran, Työryhmä Suomen Kardiologisen Seuran Asettama. Käypä hoito -suosituksen päivitystiivistelmä: eteisvärinä. Duodecim; lääketieteellinen aikakauskirja. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kneeland PP, Fang MC.. Trends in catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation in the United States. J Hosp Med 2009;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Staerk L, Sherer JA, Ko D, Benjamin EJ, Helm RH. Atrial fibrillation: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical outcomes. Circ Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lane DA, Skjøth F, Lip GYH, Larsen TB, Kotecha D.. Temporal trends in incidence, prevalence, and mortality of atrial fibrillation in primary care. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e005155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vinter N, Huang Q, Fenger-Grøn M, Frost L, Benjamin EJ, Trinquart L.. Trends in excess mortality associated with atrial fibrillation over 45 years (Framingham Heart Study): community based cohort study. The BMJ 2020;370:m2724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schnabel RB, Yin X, Gona P, Larson MG, Beiser AS, McManus DDet al. 50 year trends in atrial fibrillation prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and mortality in the Framingham Heart Study: a cohort study. Lancet North Am Ed 2015;386: 154–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Forslund T, Komen JJ, Andersen M, Wettermark B, von Euler M, Mantel-Teeuwisse AKet al. Improved stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation after the introduction of non-Vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants: the Stockholm experience. Stroke 2018;49: 2122–2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos . ICD-10 Koodistopalvelin https://koodistopalvelu.kanta.fi/codeserver/pages/classification-view-page.xhtml?classificationKey=23&versionKey=58 (13 December 2022).

- 30. Tolonen H, Salomaa V, Torppa J, Sivenius J, Immonen-Räihä P, Lehtonen A.. The validation of the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register and Causes of Death Register data on stroke diagnoses. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2007;14:380–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sund R. Quality of the Finnish hospital discharge register: a systematic review. Scand J Public Health 2012;40;505–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Because of the sensitive nature of the data collected for this study, requests to access the dataset from qualified researchers trained in human subject confidentiality protocols may be sent to the Finnish national register holders (KELA, Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare, Population Register Center and Tax Register) through Findata (https://findata.fi/en/).