Abstract

Background

This study explored the risk mitigation practices of multidisciplinary oncology health-care personnel for the nonmedical use of opioids in people with cancer.

Methods

An anonymous, cross-sectional descriptive survey was administered via email to eligible providers over 4 weeks at The Ohio State University’s Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital. The survey asked about experiences and knowledge related to opioid use disorders.

Results

The final sample of 773 participants included 42 physicians, 213 advanced practice providers (APPs consisted of advanced practice nurses, physician assistants, and pharmacists), and 518 registered nurses. Approximately 40% of participants responded feeling “not confident” in addressing medication diversion. The most frequent risk reduction measure was “Checking the prescription drug monitoring program” when prescribing controlled medications, reported by physicians (n = 29, 78.4%) and APPs (n = 164, 88.6%).

Conclusion

People with cancer are not exempt from the opioid epidemic and may be at risk for nonmedical opioid use (NMOU) and substance use disorders. Implementing risk reduction strategies with every patient, with a harm reduction versus abstinence focus, minimizes harmful consequences and improves. This study highlights risk mitigation approaches for NMOU, representing an opportunity to improve awareness among oncology health-care providers. Multidisciplinary oncology teams are ideally positioned to navigate patients through complex oncology and health-care journeys.

Keywords: opioid use disorders, nonmedical use of opioids, oncology health-care personnel, harm reduction

This study explored the risk mitigation practices of multidisciplinary oncology health-care personnel for the nonmedical use of opioids in people with cancer.

Implications for Practice.

A cancer diagnosis represents another opportunity to recognize, prevent, and assist patients in negotiating the challenges associated with nonmedical substance use. Risk reduction strategies improve safety and support patients through cancer treatment completion and into survivorship.

Introduction

The opioid epidemic is a public health crisis, recently leading to more attention on addiction in patients living with cancer and their support systems.1-4 Substance use disorders, including opioid use disorders (OUDs), are complex and multifactorial. Opioids are the gold standard for patients with cancer-related pain, and exposure may increase the risk of developing an OUD.5-7 The prevalence of nonmedical opioid use (NMOU), broadly defined as the use of opioids differently than as prescribed, is not well understood in people with cancer.8 Reasons for NMOU vary, ranging from preventing withdrawal symptoms to coping with trauma, such as a cancer diagnosis, and even motives, such as boredom or sleep.9 While not all NMOU is harmful or problematic, ranging from “normal” opioid adherence, to maladaptive use, to OUDs and addiction, this is a slippery slope.10 Continued use of opioids may cause changes to brain circuitry. These changes may result in both reward activation, as well as inhibition of self-control, with the potential for experiencing serious adverse events such as neurotoxicity, OUDs, overdose, or even death.8,10,11

The prevalence of NMOU, broadly defined as the use of opioids differently than as prescribed, is not well understood in people with cancer.8 These behaviors occur on a continuum, varying from “normal” opioid adherence to maladaptive to OUDs. While not all NMOU is harmful, this is a slippery slope for patients with cancer, with the potential for experiencing complications related to substance use and nonadherence to cancer treatment such as missed or delayed therapy, which may ultimately result in suboptimal treatment, leading to disease progression, increased symptoms, and even death.1-4,8 A systematic review of 21 articles looking at substance use in people with cancer recognized several challenges, including using different terminology, definitions, and different assessment tools, which complicated the synthesis of data.4 Changes in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders (DSM) from DSM-IV to DSM-5 may be partly responsible.10 The review included 7 articles examining opioid use and reported a median of 18%.4 Another article reported abnormal urine toxicology results in 34% of patients with oncologic pain (n = 840).12 Abnormal results included detected-not-prescribed (n = 439, 52%), tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) (n = 438, 52%), prescribed-not-detected (n = 60, 7%), and illicit substances (n = 44, 5%) such as cocaine, heroin, and fentanyl.

Harm reduction focuses on risk reduction versus abstinence, minimizing the harmful consequences of drug use, and should be offered in all practice environments.9,13 The intent of the harm reduction model is to reduce stigma by coordinating care around nonjudgmental interactions.13 This approach may be more realistic for oncology providers to begin recognizing NMOU and managing these behaviors through risk mitigation in their patient population.14 Stigma and lack of knowledge are significant provider-identified barriers to people receiving evidence-based care for an OUD.15 Gabbard et al16 recommend the universal training of all personnel, including oncology, to care for people with nonmedical substance use. In addition, a recent study of oncology health-care professionals concluded that there is an urgent need to address knowledge gaps related to opioid safety and practices in oncology clinicians.17

A hospital-wide, multidisciplinary survey was conducted among oncology health-care providers at the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital (The James) in Columbus, OH, USA. The James serves central and southern Ohio, as well as Northern West Virginia, areas hit hard by the opioid epidemic.18 The specific aim was to identify experiences and knowledge with substance and OUDs among oncology health-care providers. This article focuses on mitigation strategy use, emphasizing risk reduction approaches for every patient to improve safety and health outcomes while decreasing stigma.

Methods

Sample and Data Collection

This study, a cross-sectional, descriptive survey of multidisciplinary health-care providers, was anonymous and determined to be exempt by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). Invitations to participate in the survey were distributed via email to all eligible health-care providers employed at the James Comprehensive Cancer Center (n = 2580), including the satellite ambulatory sites. Eligible providers included physicians (~900), advanced practice providers (APPs consisted of advanced practice nurses (APN), physician assistants (PA), and pharmacists) (~480), and registered nurses (~1200). Advanced practitioners in oncology include nurse practitioners, physician assistants, clinical nurse specialists, advanced degree nurses, and pharmacists (Advanced Practitioners Society for Hematology and Oncology, N.D.). The invitation email included a link to participate in an online survey anytime during a 4-week time period in January and February 2020. Potential participants also received weekly reminder emails.

The consent and administration of the survey used REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a software toolset and workflow system for electronic data collection, storage, and management of clinical and research data.19,20 Once informed consent was obtained, interested participants could proceed with the survey. Participation was voluntary, and identifiers (email addresses) were removed from the dataset to deidentify respondents. Once the survey (discussed below) was completed, participants could voluntarily include an email address to receive a 5-dollar gift card to the hospital coffee shop. Data were collected using REDCap and analyzed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Before beginning the study, a sample size estimation was not conducted because a large number of all health-care providers described were invited to participate.

Measures

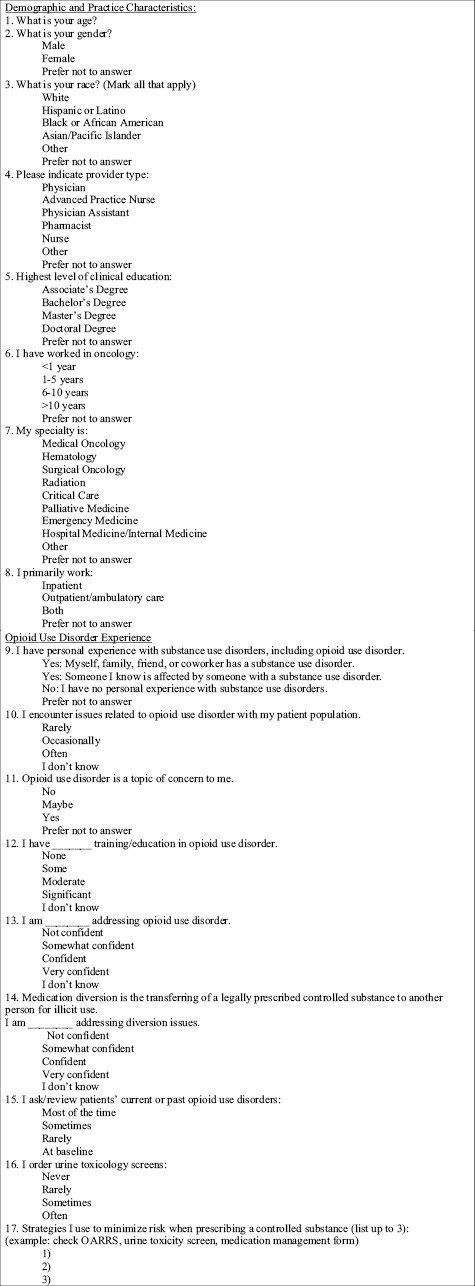

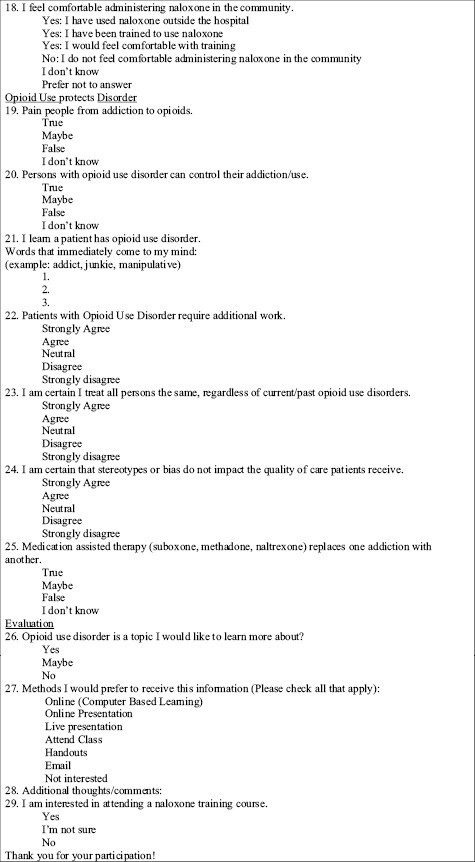

The complete survey, OUD Experiences and Knowledge, consisting of 29 questions, including demographic and clinical practice information, was administered in English and took less than 10 minutes to complete. The authors created the survey based on their clinical experience. Content validity of the OUD Experiences and Knowledge tool was created using the authors’ clinical experience, as well as from feedback provided by 3 addiction medicine physicians and a public health professor. The findings reviewed here will focus on providers’ experiences with patients and risky opioid use in the oncology setting. The complete survey can be found in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Complete survey.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses of the survey were conducted. First, responses were summarized using appropriate descriptive statistics: mean and SD (for continuous and normal data), the median, and first to third quartiles (for skewed data) or counts (for categorical variables). Next, the responses were compared across different oncology health-care providers (physicians, APPs, and nurses) using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical data, with a significance level of .05. Finally, for significant results (P≤.05), additional pairwise comparisons were made between the 3 health-care provider groups using the appropriate method (Chi-square tests, Fisher’s exact tests), with a Bonferroni corrected significance level of .017.

Results

Sample Characteristics

There were 847 surveys completed, with 74 participants excluded (provider type could not be determined). The final sample was 773 and included 42 physicians, 213 APPs (180 APNs/PAs and 33 pharmacists), and 518 nurses. The response rates were 5% for physicians, 50% for APNs and PAs, 28% for pharmacists, and 43% for nurses. Nurses and APPs accounted for the majority of the respondents (>90%). The sample was predominantly female (n = 676, 87.8%) and White (n = 679, 89.6%), with an overall mean age of 38.8 years (SD of 11 years). More physicians were male (n = 23, 54.8%) and White (n = 28, 66.7%). Table 1 summarizes the participant characteristics.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

| Variable | Physicians (n = 42) | Advanced practice providers (n = 213) | Nurses (n = 518) | All response (n = 773) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, (SD) | 41.8 (9.7) | 39.3 (9.9) | 38.4 (11.4) | 38.8 (11.0) |

| n (%) | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 19 (45.2) | 175 (82.9) | 482 (93.2) | 676 (87.8) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 28 (66.7) | 190 (90.9) | 461 (90.6) | 679 (89.6) |

| Education | ||||

| ≤Bachelor’s degree | 0 (0) | 3 (1.4) | 437 (86.4) | 440 (58.2) |

| ≥Master’s degree | 42 (100) | 205 (98.6) | 69 (13.6) | 316 (41.8) |

| Oncology experience | ||||

| 0-5 years | 17 (40.5) | 88 (41.5) | 255 (49.8) | 360 (47.0) |

| 6-10 years | 9 (21.4) | 55 (25.9) | 110 (21.5) | 174 (22.7) |

| 10 years | 16 (38.1) | 69 (32.6) | 147 (28.7) | 232 (30.3) |

| Specialty | ||||

| Medical oncology | 8 (19.0) | 43 (20.9) | 124 (24.5) | 175 (23.2) |

| Hematology | 14 (33.3) | 62 (30.1) | 153 (30.2) | 229 (30.3) |

| Surgical oncology | 10 (23.8) | 27 (13.1) | 104 (20.5) | 141 (18.7) |

| Other | 10 (23.8) | 74 (35.9) | 126 (24.9) | 210 (27.8) |

| Work location | ||||

| Inpatient | 3 (7.1) | 85 (39.9) | 273 (53.3) | 361 (47.1) |

| Ambulatory | 8 (19.0) | 87 (40.9) | 195 (38.1) | 290 (37.8) |

| Both | 31 (73.8) | 41 (19.3) | 44 (8.6) | 116 (15.1) |

| I encounter issues related to OUDs with my patient population: | ||||

| Rarely/occasionally | 32 (78.1) | 126 (63.6) | 369 (75.6) | 527 (72.5) |

| Often | 9 (22.0) | 72 (36.4) | 119 (24.4) | 200 (27.5) |

Advanced practice providers: advanced practice nurses, physician assistants, or pharmacists.

Abbreviation: OUDs: opioid use disorders.

Risk Mitigation Strategy Use by Oncology Providers

Respondents were asked about specific risk reduction measures, for example, if they reviewed the patient’s past or present history of OUD. A greater percentage of physicians assessed OUD history “sometimes or most of the time” (n = 34, 82.9%), in comparison to APPs (n = 148, 72.9%) and nurses (n = 238, 48.3%) (P < .001). The definition of medication diversion, transferring a legally prescribed controlled substance to another person for illicit use, was included in the survey. Approximately 40% of all participants answered that they were not confident in addressing diversion, although this varied by provider type (P < .001). More nurses (n = 213, 44.8%) responded that they were not confident in addressing diversion issues, compared to physicians (n = 14, 35%) and APPs (n = 59, 29.1%).

Providers were asked via the survey about conducting urine toxicology of their patients. More than half physicians and APPs “never” or “rarely” ordered urine toxicology screens (n = 101, 56.5%). A larger proportion of physicians answered that they ordered urine toxicology screens “sometimes” or “often” (n = 19, 46.3%) compared to APPs (n = 82, 40.2%). As expected, significantly more nurses (n = 436, 89.2%) reported that they “never” or “rarely” ordered toxicology screens, as this is not in their scope of practice.

Participants were asked to provide 3 strategies that minimized risk when prescribing controlled substances. The most common response was “checking the prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP)” for physicians (n = 29, 78.4%) and APPs (n = 164, 88.6%). “Limiting the prescription, including the amount, duration, or dose” was the second most common response (physicians: n = 10, 27%; APPs: n = 48, 25.9%). Many nurses responded with “Not applicable” or “Do not prescribe as part of their duties ”; however, 34 nurses (11.9%) reported checking the PDMP. Complete results are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Risk reduction responses.

| Statement | Response | Physicians (n = 42) | Advanced practice providers (n = 213) | Registered nurses (n = 518) | All respones (n = 773) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I ask/review patients’ current or past history of OUDs | At baseline/rarely | 7 (17.1) | 55 (27.1) | 255 (51.7) | 317 (43.0) | <.001*,# |

| Sometimes/most of the time | 34 (82.9) | 148 (72.9) | 238 (48.3) | 420 (57.0) | ||

| I order urine toxicology screens | Never/rarely | 22 (53.7) | 122 (59.8) | 436 (89.2) | 580 (79.0) | <.001*,# |

| Sometimes/often | 19 (46.3) | 82 (40.2) | 53 (10.8) | 154 (21.0) | ||

| I am addressing diversion issues | Not confident | 14 (35.0) | 59 (29.1) | 213 (44.8) | 286 (39.8) | <.001# |

| Somewhat confident/confident/very confident | 26 (65.0) | 144 (70.1) | 263 (55.3) | 433 (60.2) | ||

| Strategies I use to minimize risk when prescribing a controlled substance (list up to 3): (eg, check PDMP, urine toxicity screen, medication management form) | Prescription Drug Monitoring Program | 29 (78.4) | 164 (88.6) | 34 (11.9) | 227 (44.8) | N/A |

| Review patient/medication History | 4 (10.8) | 36 (19.5) | 19 (6.7) | 59 (11.6) | ||

| Education (safe storage, disposal, etc.) | 3 (8.1) | 33 (17.8) | 8 (2.8) | 44 (8.7) | ||

| Limit Rx: amount, duration, dose | 10 (27) | 48 (25.9) | 11 (3.9) | 69 (13.6) | ||

| Referral (palliative, SW, PT etc) | 7 (18.9) | 16 (7.6) | 5 (1.8) | 28 (5.5) | ||

| Medication Agreement Form (contract) | 6 (16.2) | 22 (11.9) | 9 (3.2) | 37 (7.3) | ||

| Urine toxicology | 7 (18.9) | 14 (7.6) | 6 (2.1) | 27 (5.3) | ||

| Alternatives/nonopioid/multimodal | 3 (8.1) | 22 (11.9) | 6 (2.1) | 31 (6.1) | ||

| N/A, do not prescribe | 1 (2.7) | 16 (8.6) | 230 (80.7) | 247 (48.7) | ||

| No strategies | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.1) | 4 (0.8) | ||

| Response left blank | 5 | 28 | 233 | 266 |

Because of missing data, numbers may not be equal the number of total respondents. Because many nurses left the response to the strategies used question blank, the number of blank responses is reported, and percentages are calculated out of providers who gave a response. It is possible that these nurses would have responded similarly to the high number of nurses who indicated they do not have the ability to prescribe medications as part of their duties.

Advanced practice providers: advanced practice nurses, physician assistants, or pharmacists.

No physician versus APP comparisons were significant at P < .017.

*Physicians versus nurses significant at P < .017.

#APPs versus nurses significant at P < .017.

Abbreviations: MAT: medication assisted therapy; OUDs: opioid use disorders; SUDs: substance use disorders; Rx: prescription; N/A: not applicable.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting on clinician knowledge and self-reported practice of opioid risk reduction strategies among people with cancer. Despite the recent increased attention in oncology, guidelines are lacking for managing substance use and nonmedical use of opioids in patients with cancer. Our results are similar to Tedesco et al,17 suggesting oncology health-care team members may not be prepared to manage coexisting OUDs, with gaps in knowledge and practice leading to under-recognition. Incorporating harm reduction and risk mitigation approaches as universal precautions into routine oncology care likely reduces both stigma and risk, subsequently optimizing safety while improving treatment adherence and cancer outcomes.3,21-25 This study identifies harm reduction as an opportunity to reduce risk, enhance patient safety, and improve outcomes.

Nearly half of our study participants reviewed substance use history rarely or only at baseline. Some interventions for these patients might include: All oncology patients should be screened for substance use, including nonmedical use of medications. Recognition of patients with possible substance use provides the opportunity to receive appropriate, life-saving interventions.3 Standard screening tools could be used, or providers can ask about substance use directly, with a neutral, nonjudgmental question. Patients should be asked about all substances used, including use specifics such as frequency and date of last use. One example is, “in the past year, have you used any drugs such as cocaine or heroin, or have you used any prescription medications not as prescribed? Can you tell me more about your use of X drugs?” It is important to have patients define frequencies such as “occasionally” or “sometimes,” as this may vary significantly among individuals. Identifying the method(s) of administration assists in determining complication risk. For example, intravenous injection is a risk factor for tissue and bloodstream infections.26

Prescribers are responsible for recognizing and preventing drug diversion with their patients. Diversion occurs when prescription medications are used by someone other than the prescription is intended.27 Respondents were asked about confidence addressing diversion, with a noteworthy amount admitting to being “not confident.” Our results are similar to Tedesco et al,17 who reported 55% of oncology clinicians having limited confidence in identifying and managing aberrant behaviors. Health-care personnel should be knowledgeable of necessary precautions to minimize risky use and diversion, especially as prescription opioids for nonmedical use are most often obtained from someone they know.28,29 Informal caregivers and family members are often responsible for the medication diversion in people with cancer.30 This means support systems may also be at risk; for example, the teenager with access to their mother’s opioids for her cancer-related pain. Because of the teenager’s potential exposure to their mother’s opioids, the possibility exists for developing a lifelong OUD. Utilizing a harm reduction philosophy decreases the risk of diversion, potentially increasing safety for the community, including non-oncology patients.

Participants were asked to provide strategies for minimizing the risk of prescribing controlled substances (ie, diversion or nonmedical use). The most common response was “checking the PDMP.” The PDMP is an electronic database that provides important prescription data on controlled substances, such as the date the prescription was filled, how many tablets were dispensed, and who the prescriber of each medication was. In addition, the PDMP may indicate if patients receive controlled substance prescriptions from multiple provider sources. Many institutions have integrated the PDMP into the electronic medical record, making it easier to use.8 Recommendations include reviewing the PDMP at least every 3 months, if not every time, before prescribing opioids, benzodiazepines, or other medications considered high risk for nonmedical use, such as gabapentin.14,23

“Placing limitations on the prescription,” such as limiting the dose, duration, or amount dispensed, was the second most common response. This includes using a single prescriber or team, and only using one pharmacy. Weekly prescriptions decrease the dispense quantity, and reducing the number of available pills available. Limitations on prescriptions may be warranted for patients determined to be higher risk and should not be misinterpreted as underrecognizing or undertreating cancer-related pain, which may be considered unethical. In addition, refills may be dated, ie, do not fill before [date], and no early refills are provided.14,23,30 Safer prescribing increases safety and effectiveness of cancer pain control, while decreasing opioid-related risks and reducing the number of unused prescription opioids available for diversion, nonmedical use, addiction, and overdose.14,23,27,30

Other mitigation strategies participants provided included using a medication management agreement (contract), patient education, referrals, and alternatives, such as nonopioid and multimodal therapies for pain control. For example, education improves proper opioid use, storage and disposal, reducing diversion, and accidental ingestion.29 Patients may share medications with family members or friends and should be told that “Your medication is for you alone.” Unsafe storage and disposal of opioid medications is a concern for households with children. Controlled substance agreements, also known as “contracts,” may be well intentioned; however, controversy exists as the language may be mistrustful, accusatory, and even confrontational, stigmatizing the patient.31,32 Failing to abide by a contract may be shameful. Preserving trust and the therapeutic relationship between patients and oncology providers are critical. For example, people should not be “fired” or discharged from care in response to deviation from the medication agreement, this does not convey a reciprocal, balanced, compassionate relationship.31,32Examples of referrals include palliative medicine, integrative medicine, social work, and physical therapy. Refer to Table 3 for a complete list of suggested harm reduction strategies.

Table 3.

Harm and risk reduction strategies for EVERY/ALL patients.

| Review substance use history |

| ◦ Current/past use of drugs or misuse of prescription medication |

| ■ If yes: |

| • When (now or previously) |

| • What (alcohol, cocaine, opioid, prescription, etc.) |

| • How (oral, IV, smoke, snort, etc.) • Frequency (how many times a day/week/month/year) |

| • Last use |

| ◦ Family history of substance use (same as above) |

| Safe(r) prescribing practices |

| Controlled substances: |

| • Determine risk for misuse |

| • Risk factors |

| • Personal/family history |

| • Psychiatric history |

| • Consider Screening Questionnaire |

| • Minimize risk: |

| • Check Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) |

| • Single prescriber (individual/team) |

| • Single pharmacy |

| • Electronic prescriptions |

| • Urine toxicology screens |

| • Limit prescription quantity (ie, weekly) |

| • Decrease “Pill load” (sustained vs. immediate release; fewer/less pills) |

| • QID/TIDprn vs. q4hprn |

| • Monitor adherence |

| • Monitor aberrant behaviors |

| Limit IV access |

| • Alternative treatment options available? |

| • If requires central line: |

| ◦ No mediport |

| ◦ Peripherally inserted central line catheter |

| • Placed or removed at each treatment visit or |

| • Admission |

| Patient/support system education |

| • Proper medication use |

| ◦ Check health literacy, ie, able to read the prescription label |

| • Storage |

| • Disposal |

| Referrals |

| • Social work |

| • Addiction medicine |

| • Mental health |

| • Primary care |

| Naloxone |

| • Prescription with every opioid prescription |

| • Educate patients and support systems on opioid overdose recognition and naloxone administration |

| Buprenorphine |

| • Increasingly preferred initial opioid for pain management |

| • Low-dose initiation |

| • Education patients and support systems to eliminate stigma and misconceptions |

“Pill counting,” a strategy for recognizing medication diversion, was not mentioned. A comprehensive review by Gill et al33 focused on pill counting as an intervention to increase adherence and decrease adverse outcomes. Several limitations to the review were noted, including little data, and pill counting was poorly defined and inconsistently implemented across studies. Feasibility concerns exist, and patients may not be able to come in for random pill counts or may forget to bring medications in for verification.33

Not surprisingly, more than half of our sample’s physicians and APPs never or rarely ordered urine toxicology. Urine toxicology may be underused in people with cancer, specifically related to managing cancer-related pain, because there are no current guidelines.3,8,34 Toxicology screening may identify unexpected findings, including NMOU and concerns for diversion.34 The interpretation of the results is also challenging. Accuracy is critical to prevent false interpretation of nonadherence or nonmedical use. Results, both expected and unexpected, should be discussed with the patient openly and nonjudgmentally.14,23,34 Concerns exist with the unexpected absence of prescribed medications, as well as the presence of other drugs or substances in tested samples. Although patients may offer excuses for unexpected results, providers should clearly identify the concern; for example, providers should openly state they are worried about the patients’ potential risky use or addiction and provide the reason for their apprehension. The intent should be to reduce stigma through nonjudgmental interactions, using appropriate clinical language when reviewing urine toxicology results and expressing care for the patient’s wellbeing. Providers should express their commitment and nonabandonment while validating patients’ suffering, regardless of nonmedical use, addiction, or diversion.3

Harm reduction strategies not mentioned in the survey include naloxone and buprenorphine. The Food and Drug Administration is encouraging health professionals to discuss and prescribe naloxone, a harm reduction strategy, when prescribing opioid medications.35 Naloxone is administered intranasally in the community; it rapidly displaces opioids from their receptors, quickly reversing opioid overdoses. There is no harm from administering naloxone if opioids are not present.36All patients and their support systems should be trained on how to administer naloxone safely. Buprenorphine, a partial mu-opioid receptor agonist, is increasingly used as the initial preferred analgesia in people with cancer, including those with nonmedical substance use or concomitant OUD.37,38 Previously providers completed additional training to obtain an X-waiver to prescribe buprenorphine for the outpatient treatment of OUD; however, an X-waiver is no longer required.37 Buprenorphine is safe and effective to treat both OUD and cancer-related pain. Low-dose initiation of buprenorphine, small, gradually increasing doses, prevents the need to stop full agonist opioids to avoid withdrawal.38 Health-care providers are key to eliminating misconceptions and stigma about buprenorphine.

Limitations

Some limitations to this study should be addressed in future research. This study was potentially limited by implementation at a single institution, an urban, comprehensive cancer center with more OUD education and resources than other institutions may have. Although face and content validity were established, the authors created the survey and did not have formal testing for validity and reliability. Differences in response rates among the health-care provider types existed, resulting in disproportionate representation. For example, the response rate among physicians was only 5%. The authors recognize that all providers have a role in identifying and addressing NMOU; however, this role varies between provider type and practice location. The questions of our survey may not have been applicable to every participant. Future studies should include more diverse settings and participants and concentrate recruiting efforts to yield a more balanced representation by provider type.

Conclusion

People with cancer may have a current or past history of addiction or may be at an increased risk of NMOU and developing an addiction. Harm and risk reduction strategies can be implemented into routine oncology care, utilizing a standard precautions approach. Applying mitigation approaches to every person improves safety while decreasing stigma. This is the first study to our knowledge examining multidisciplinary oncology clinicians self-reported opioid risk reduction techniques. Many participants lacked confidence addressing diversion; methods to improve safety include reviewing the history of substance use, ordering urine toxicology, checking the PDMP, and placing limitations on the prescription, among other approaches. Naloxone education and prescriptions can be provided with every opioid analgesic and to people at risk for an opioid overdose. Elimination of the X-waiver, in combination with the additional training requirements, not only removes a major barrier but also encourages clinicians in oncology to prescribe buprenorphine to patients with concomitant OUD.39 Our findings support the need for additional education, tailored for individual team members, to improve safety while delivering high quality, person-centered cancer care. Integrating appropriate clinical and nonjudgmental language into everyday oncology practice strengthens empathy, compassion, and understanding and improve health outcomes for this population.

Acknowledgments

A sincere thank you to Kris Kipp, MSN, RN, and the James Cancer Hospital for their continuous support to positively impact the opioid epidemic, as well as Julie Teater, Peggy Williams, Emily Kaufman, and Pam Salsberry for providing face and content validity for the questionnaire. The authors also are very appreciative of Carlton Brown for proofreading and providing constructive feedback of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Gretchen A McNally, Department of Nursing, James Cancer Hospital, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA.

Eric M McLaughlin, Center for Biostatistics, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA.

Emily Ridgway-Limle, Department of Nursing, James Cancer Hospital, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA.

Robin Rosselet, College of Nursing, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA.

Robert Baiocchi, Division of Hematology, College of Medicine, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA.

Funding

This study was funded in part by internal funds from the James Cancer Hospital Department of Nursing and The Ohio State University Center for Clinical and Translational Science grant support (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant no. UL1TR002273).

Conflict of Interest

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: G.A.M., R.R., and R.B. Provision of study material or patients: G.A.M., R.R., and R.B. Collection and/or assembly of data: G.A.M., E.M.M., and E.R.-L. Data analysis and interpretation: G.A.M., E.M.M., and E.R.-L. Manuscript writing and final approval of manuscript: all authors.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Arthur J, Bruera E.. Balancing opioid analgesia with the risk of nonmedical opioid use in patients with cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16(4):213-226. 10.1038/s41571-018-0143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Magee D, Bachtold S, Brown M, Farquhar-Smith P.. Cancer pain: where are we now?. Pain Manag. 2019;9(1):63-79. 10.2217/pmt-2018-0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sager Z, Childers J.. Navigating challenging conversations about nonmedical opioid use in the context of oncology. Oncologist. 2019;24(10):1299-1304. 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yusufov M, Braun IM, Pirl WF.. A systematic review of substance use and substance use disorders in patients with cancer. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2019;60:128-136. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2019.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Amaram-Davila J, Davis M, Reddy A.. Opioids and cancer mortality. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2020;21(3):22. 10.1007/s11864-020-0713-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Chou R.. CDC clinical practice guideline for prescribing opioids for pain - United States, 2022. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022;71(3):1-95. 10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pinkerton R, Hardy JR.. Opioid addiction and misuse in adult and adolescent patients with cancer. Intern Med J. 2017;47(6):632-636. 10.1111/imj.13449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ulker E, Del Fabbro E.. Best practices in the management of nonmedical opioid use in patients with cancer-related pain. Oncologist. 2020;25(3):189-196. 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sue KL, Fiellin DA.. Bringing harm reduction into health policy - combating the overdose crisis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(19):1781-1783. 10.1056/NEJMp2103274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11. American Society of Addiction Medicine. American Society of Addiction Medicine Releases New Definition of Addiction to Advance Greater Understanding of the Complex, Chronic Disease. ASAM; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leap KE, Chen GH, Lee J, Tan KS, Malhotra V.. Identifying prevalence of and risk factors for abnormal urine drug tests in cancer pain patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;62(2):355-363. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kapadia SN, Griffin JL, Waldman J, et al. A harm reduction approach to treating opioid use disorder in an independent primary care practice: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(7):1898-1905. 10.1007/s11606-020-06409-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McNally GA, Sica A, Wiczer T.. Managing addiction: guidelines for patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2019;23(6):655-658. 10.1188/19.CJON.655-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mackey K, Veazie S, Anderson J, Bourne D, Peterson K.. Barriers and facilitators to the use of medications for opioid use disorder: a rapid review. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(Suppl 3):954-963. 10.1007/s11606-020-06257-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gabbard J, Jordan A, Mitchell J, et al. Dying on hospice in the midst of an opioid crisis: what should we do now?. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019;36(4):273-281. 10.1177/1049909118806664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tedesco A, Brown J, Hannon B, Hutton L, Lau J.. Managing opioids and mitigating risk: a survey of attitudes, confidence and practices of oncology health care professionals. Curr Oncol. 2021;28(1):873-878. 10.3390/curroncol28010086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. MacKinnon NJ, Privitera E.. Addressing the opioid crisis through an interdisciplinary task force in Cincinnati, Ohio, USA. Pharmacy (Basel). 2020;8(3). 10.3390/pharmacy8030116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gourlay DL, Heit HA, Almahrezi A.. Universal precautions in pain medicine: a rational approach to the treatment of chronic pain. Pain Med. 2005;6(2):107-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Paice JA. Managing pain in patients and survivors: challenges within the United States opioid crisis. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(5.5):595-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Paice JA. Risk assessment and monitoring of patients with cancer receiving opioid therapy. Oncologist. 2019;24(10):1294-1298. 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Paice JA, Portenoy R, Lacchetti C, et al. Management of chronic pain in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(27):3325-3345. 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.5206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jones KF, Merlin JS.. Approaches to opioid prescribing in cancer survivors: lessons learned from the general literature. Cancer. 2022;128(3):449-455. 10.1002/cncr.33961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thakarar K, Rokas KE, Lucas FL, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and cardiac surgery in Injection Drug Use (IDU)-associated versus non-IDU infective endocarditis: the need to expand substance use disorder treatment and harm reduction services. PLoS One. 2019;14(11):e0225460-e0225415. 10.1371/journal.pone.0225460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schäfer WLA, Johnson JK, Wafford QE, Plummer SG, Stulberg JJ.. Primary prevention of prescription opioid diversion: a systematic review of medication disposal interventions. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2021;47(5):548-558. 10.1080/00952990.2021.1937635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Milani SA, Lloyd SL, Serdarevic M, Cottler LB, Striley CW.. Gender differences in diversion among non-medical users of prescription opioids and sedatives. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2020;46(3):340-347. 10.1080/00952990.2019.1708086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Reddy A, de la Cruz M.. Safe opioid use, storage, and disposal strategies in cancer pain management. Oncologist. 2019;24(11):1410-1415. 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ware OD, Cagle JG, McPherson ML, et al. Confirmed medication diversion in hospice care: qualitative findings from a national sample of agencies. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61(4):789-796. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Philpot LM, Ramar P, Elrashidi MY, et al. Controlled substance agreements for opioids in a primary care practice. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2017;10(29):1-7. 10.1186/s40545-017-0119-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tobin DG, Keough Forte K, Johnson McGee S.. Breaking the pain contract: a better controlled-substance agreement for patients on chronic opioid therapy. Cleve Clin J Med. 2016;83(11):827-835. 10.3949/ccjm.83a.15172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gill B, Obayashi K, Soto VB, Schatman ME, Abd-Elsayed A.. Pill counting as an intervention to enhance compliance and reduce adverse outcomes with analgesics prescribed for chronic pain conditions: a systematic review. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2022;26(12):883-887. 10.1007/s11916-022-01091-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Arthur JA. Urine drug testing in cancer pain management. Oncologist. 2020;25(2):99-104. 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. FDA. FDA Recommends Health Care Professionals Discuss Naloxone with All Patients When Prescribing Opioid Pain Relievers or Medicines to Treat Opioid Use Disorder. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chan CA, Canver B, McNeil R, Sue KL.. Harm reduction in health care settings. Med Clin North Am. 2022;106(1):201-217. 10.1016/j.mcna.2021.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ho JJ, Jones KF, Merlin JS, Sager Z, Childers J.. Buprenorphine initiation: low-dose methods #457. J Palliat Med. 2023;26(6):867-869. 10.1089/jpm.2023.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Neale KJ, Weimer MB, Davis MP, et al. Top ten tips palliative care clinicians should know about buprenorphine. J Palliat Med. 2023;26(1):120-130. 10.1089/jpm.2022.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. US Department of Justice. Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023. US Department of Justice Drug Enforcement Administration; 2023. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.