Abstract

Background

Direct KRASG12C inhibitors are approved for patients with non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC) in the second-line setting. The standard-of-care for initial treatment remains immune checkpoint inhibitors, commonly in combination with platinum-doublet chemotherapy (chemo-immunotherapy). Outcomes to chemo-immunotherapy in this subgroup have not been well described. Our goal was to define the clinical outcomes to chemo-immunotherapy in patients with NSCLC with KRASG12C mutations.

Patients and Methods

Through next-generation sequencing, we identified patients with advanced NSCLC with KRAS mutations treated with chemo-immunotherapy at 2 institutions. The primary objective was to determine outcomes and determinants of response to first-line chemo-immunotherapy among patients with KRASG12C by evaluating objective response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS). We assessed the impact of coalterations in STK11/KEAP1 on outcomes. As an exploratory objective, we compared the outcomes to chemo-immunotherapy in KRASG12C versus non-G12C groups.

Results

One hundred and thirty eight patients with KRASG12C treated with first-line chemo-immunotherapy were included. ORR was 41% (95% confidence interval (CI), 32-41), median PFS was 6.8 months (95%CI, 5.5-10), and median OS was 15 months (95%CI, 11-28). In a multivariable model for PFS, older age (P = .042), squamous cell histology (P = .008), poor ECOG performance status (PS) (P < .001), and comutations in KEAP1 and STK11 (KEAP1MUT/STK11MUT) (P = .015) were associated with worse PFS. In a multivariable model for OS, poor ECOG PS (P = .004) and KEAP1MUT/STK11MUT (P = .009) were associated with worse OS. Patients with KRASG12C (N = 138) experienced similar outcomes to chemo-immunotherapy compared to patients with non-KRASG12C (N = 185) for both PFS (P = .2) and OS (P = .053).

Conclusions

We define the outcomes to first-line chemo-immunotherapy in patients with KRASG12C, which provides a real-world benchmark for clinical trial design involving patients with KRASG12C mutations. Outcomes are poor in patients with specific molecular coalterations, highlighting the need to develop more effective frontline therapies.

Keywords: non-small cell lung cancer, KRASG12C, combination therapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy

This study aimed to define the clinical outcomes of first-line chemo-immunotherapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer with KRASG12C mutations and to examine the significance of PD-L1 tumor proportion score and comutation status (KEAP1 and STK11) on outcomes.

Implications for Practice.

KRASG12C alterations are the most common subgroup of KRAS alterations and inhibitors of KRASG12C are now approved, yet outcomes remain suboptimal. The most used first-line treatment regimen remains chemo-immunotherapy, for which real-world outcomes are unknown. We define the outcomes to first-line chemo-immunotherapy in patients with KRASG12C mutations, which provides a real-world benchmark for clinical trial design involving patients with KRASG12C mutations. Outcomes are particularly poor in patients with specific molecular co-occurring mutations including KEAP1 and STK11, highlighting the unmet need to develop more effective first-line therapies for this patient population.

Introduction

Somatic KRAS mutations are observed in approximately 25% of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Mutations in KRASG12C are the most common KRAS molecular subtype in NSCLC, occurring in 13% of cases. Identification of the binding pocket of the mutant G12C protein led to the development of G12C inhibitors,1 which have been widely adopted in the care of patients with KRASG12C-mutant NSCLC.

Sotorasib and adagrasib are both irreversible inhibitors of KRASG12C which bind to the inactive GDP-bound state of the mutant protein. Both agents are now FDA-approved for patients with KRASG12C-mutated advanced NSCLC who have been treated with at least one prior systemic therapy. In patients treated with sotorasib, 32% of patients experienced an objective response, with a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 6.3 months.2 For adagrasib, objective response was observed in 43% of patients, with a median PFS of 6.5 months.3 The activity of these agents in the later-line setting has generated significant interest in exploring these therapies in the first-line setting, and numerous clinical trials are currently underway to evaluate this approach.4-7

The standard-of-care first-line therapy for patients with NSCLC-harboring KRASG12C mutations remains regimens incorporating immune checkpoint inhibitors either as monotherapy or in combination with platinum doublet chemotherapy (hereafter referred to as chemo-immunotherapy).8,9 We have previously described the outcomes of patients with KRASG12C-mutant NSCLC treated with single-agent immune checkpoint inhibitors.6 Furthermore, we have demonstrated that STK11 and KEAP1 mutations confer worse outcomes to single-agent immune checkpoint inhibitors among patients with mutations in KRAS. However, outcomes for patients KRASG12C-mutant NSCLC treated with combination chemo-immunotherapy, as well as impact of baseline coalterations on outcomes, have not been described outside of small subset analyses of prospective clinical trials.10 Herein, our goal was to define the clinical outcomes to first-line chemo-immunotherapy in patients with NSCLC with KRASG12C mutations and examine the significance of PD-L1 tumor proportion score and comutation status (KEAP1 and STK11) on outcomes.

Methods

Patients

Patients with advanced NSCLC from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) and Dana Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) were included in this retrospective analysis. All patients with KRAS mutations treated with first-line chemo-immunotherapy between June 2017 and November 2020 were identified. Baseline pretreatment characteristics were obtained for patients including previously reported prognostic and predictive features. This study was approved by Institutional Review Boards at MSK and DFCI.

Genomic Sequencing

Biopsies from patients treated at MSK underwent next-generation sequencing (NGS) using the MSK-IMPACT platform as previously described.11 Briefly, DNA was extracted from tumors and patient-matched blood samples. Bar-coded libraries were generated and sequenced and targeted all exons and select introns of a custom gene panel of 341 (version1), 410 (version 2), or 468 (version 3) genes. Samples were run through a custom pipeline to identify somatic mutations.

At DFCI, targeted exome NGS was carried out using the validated OncoPanel assay in the Center for Cancer Genome Discovery at the DFCI for 277 (POPv1), 302 (POPv2), or 447 (POPv3) cancer-associated genes. Variants were filtered to remove potential germline variants as previously published and annotated using Oncotractor as previously described. To remove additional germline noise, variants that were annotated as benign/likely benign in ClinVar or were present at a population maximum allele frequency of 0.1% were excluded. Variants were retained in either case if they were annotated as confirmed somatic in at least 2 samples in COSMIC as previously described.12

PD-L1 Testing

Tumoral PD-L1 expression (tumor proportion score [TPS]) was reported as the percentage of tumor cells with membranous staining. Antibodies used for this analysis included 22C3, 28-8, and E1L3N in accordance with institutional practices.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the analysis population. Differences in baseline characteristics by group were evaluated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, Fisher’s exact test, or Pearson’s chi-squared test as appropriate. An α of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. PFS was assessed from the date the patient began immunotherapy to the date of progression as previously described as per RECIST v1.1 (blinded independent radiologic review using RECIST v1.1, or investigator assessed as appropriate).13-15 Overall survival (OS) was calculated from treatment start date. Patients who did not die were censored for survival at the date of last contact. Overall response rate was defined as the rate of partial response (PR) or complete response (CR) using RECIST v1.1, or investigator assessed as appropriate.13-15

Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank test statistics were computed to compare OS time and PFS between patient groups. Cox proportional hazards models were fitted to investigate univariable/multivariable associations between covariates and OS and PFS. Covariates that were statistically significant in univariable analysis were included in subsequent multivariable analysis. Cox models for both OS and PFS were stratified by site, in order to address variations of patient population and sequencing platforms across institutions. All time to event calculations incorporated the NGS report date, such that the patients were counted in the at-risk set at the time of having available NGS data.16 In order to account for left truncation bias (bias occurring when subjects who otherwise meet entry criteria do not remain observable for a later start of follow-up),17 patients with a NGS report date after their OS date were excluded from PFS and OS analysis. Patients with NGS report date after their progression date were excluded from the PFS analysis.

For the exploratory analysis comparing KRASG12C versus non-G12C, a piece-wise structure was used to describe the OS hazard ratio (HR) between KRASG12C and non-G12C groups to satisfy the proportional hazards assumption. Specifically, we assumed the log HR between KRASG12C and non-G12C groups is β1 between 0-6 months and β2 after 6 months.

All analyses were conducted using R version 4.1.1 with the tidyverse (v1.3.1),18 gtsummary (v1.6.0),19 survival (v3.3.1),20 and survminer (v0.4.9) packages.21

Results

Patients

A total of 138 patients with KRASG12C mutations treated with first-line chemo-immunotherapy were eligible for outcome analysis (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S1). Median age was 67, interquartile range (IQR 60, 74) and 89 patients (64%) were female (Table 1). Almost all patients with KRASG12C mutations were current or former smokers (Table 1), with a median smoking history of 30 pack years (IQR 20, 40) (Table 1). The most frequent chemo-immunotherapy treatment regimen was pembrolizumab, carboplatin, and pemetrexed (Supplementary Table S1). Thirty-one (23%) of patients with KRASG12C were treated with second-line KRASG12C inhibitors (Table 1). Median PD-L1 TPS was 1 (IQR 0, 30), and 62 patients (49%) had PD-L1 TPS of <1% (Table 1). Frequencies of comutations in either KEAP1 (KEAP1MUT/STK11WT), STK11 (KEAP1WT/STK11MUT), or presence of both (KEAP1MUT/STK11MUT) are shown in Table 1. KEAP1WT/STK11WT were the most frequent phenotype in 57% (95%CI, 49-66), followed by KEAP1WT/STK11mut in 20% (95%CI, 14-28) of patients with KRASG12C mutations.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Characteristic | Overall, N = 3231 | KRAS G12C, N = 1381 | Non-G12C, N = 1851 | P-value2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 67 (60, 73) | 67 (60, 72) | 68 (60, 74) | .4 |

| Gender | .2 | |||

| Female | 194 (60%) | 89 (64%) | 105 (57%) | |

| Male | 129 (40%) | 49 (36%) | 80 (43%) | |

| Site | .009 | |||

| DFCI | 179 (55%) | 88 (64%) | 91 (49%) | |

| MSK | 144 (45%) | 50 (36%) | 94 (51%) | |

| Consolidated smoking history | <.001 | |||

| Current or former | 300 (93%) | 136 (99%) | 164 (89%) | |

| Never | 23 (7.1%) | 2 (1.4%) | 21 (11%) | |

| Pack years smoked | 30 (15, 45) | 30 (20, 40) | 30 (15, 49) | .2 |

| Unknown | 25 | 6 | 19 | |

| ECOG PS | .3 | |||

| 0 | 86 (27%) | 37 (27%) | 49 (27%) | |

| 1 | 194 (61%) | 88 (64%) | 106 (59%) | |

| 2-3 | 37 (12%) | 12 (8.8%) | 25 (14%) | |

| Unknown | 6 | 1 | 5 | |

| Histology | .7 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 297 (92%) | 128 (93%) | 169 (91%) | |

| Other | 18 (5.6%) | 6 (4.3%) | 12 (6.5%) | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 8 (2.5%) | 4 (2.9%) | 4 (2.2%) | |

| Baseline PD-L1 status | .2 | |||

| <1 | 145 (48%) | 62 (49%) | 83 (48%) | |

| 1-49 | 105 (35%) | 39 (31%) | 66 (38%) | |

| ≥50 | 49 (16%) | 26 (20%) | 23 (13%) | |

| Unknown | 24 | 11 | 13 | |

| Baseline percent PD-L1 | 1 (0, 20) | 1 (0, 30) | 1 (0, 10) | .3 |

| Unknown | 26 | 11 | 15 | |

| Treated with second-line KRASG12C inhibitor | 31 (9.6%) | 31 (23%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| STK11 and KEAP1 mutations | >.9 | |||

| KEAP1MUT/STK11MUT | 34 (11%) | 14 (10%) | 20 (11%) | |

| KEAP1MUT/STK11WT | 37 (11%) | 17 (12%) | 20 (11%) | |

| KEAP1WT/STK11MUT | 71 (22%) | 28 (20%) | 43 (23%) | |

| KEAP1WT/STK11WT | 181 (56%) | 79 (57%) | 102 (55%) |

Statistically significant P-values <.05.

1Median (IQR); n (%).

2Wilcoxon rank sum test; Pearson’s chi-squared test; Fisher’s exact test.

Abbreviations: KEAP1WT/STK11WT: wild type for both KEAP1 and STK11; KEAP1MUT/STK11WT: KEAP1-mutant, wild type for STK11; KEAP1WT/STK11MUT: wild type for KEAP1, STK11-mutant; KEAP1MUT/STK11MUT: mutant in both KEAP1 and STK11; DFCI: Dana Farber Cancer Institute; MSK: Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; PS: performance status.

Outcomes to First-Line Chemo-Immunotherapy in Patients With KRASG12C Mutations

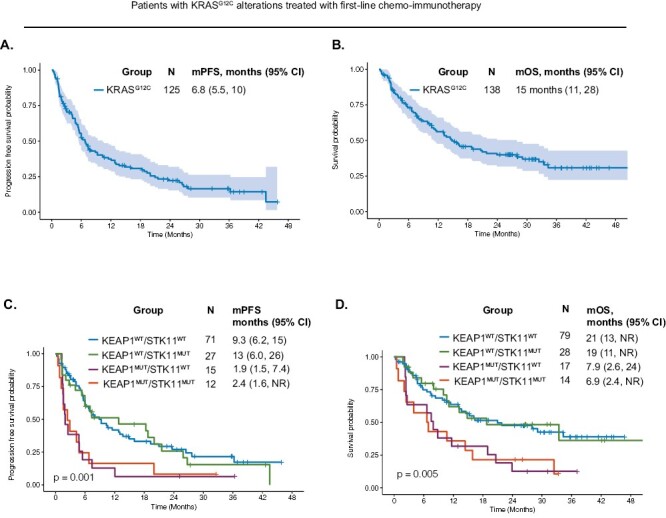

We first sought to describe the clinical outcomes to first-line chemo-immunotherapy among patients with KRASG12C mutations. Fifty-six patients experienced either a CR or PR for an overall response rate of 41%. Median PFS was 6.8 months (95%CI, 5.5-10) (Fig. 1A). Median OS was 15 months (95%CI, 11-28) (Fig. 1B). We performed univariate analyses to determine individual factors associated with outcome to chemo-immunotherapy in patients with KRASG12C mutations. Individual factors associated with worse PFS were older age (P = .034), squamous cell histology (P = .006), poor ECOG PS (P < .001), and coalterations in both KEAP1 and STK11 (KEAP1MUT/STK11MUT) (P = .023) or coalterations in KEAP1 (KEAP1MUT/STK11WT) (P = .001) (Table 2). Consistent with these results, compared to the KEAP1WT/STK11WT subgroup (median PFS: 9.3 months), patients with mutations in KEAP1mut/STK11WT had the shortest median PFS (1.9 months), followed by KEAP1MUT/STK11MUT (2.4 months) (Fig. 1C). Response rate data by mutation subgroups are shown in Supplementary Fig. S2, with KEAP1MUT/STK11MUT exhibiting a response rate of 21%. There was no difference in PFS according to PD-L1 TPS (P = .377; Supplementary Fig. S3A).

Figure 1.

Clinical outcomes to first-line chemo-immunotherapy in patients with KRASG12C mutations. (A). Progression-free survival and (B). Overall survival to first-line chemo-immunotherapy among patients with mutations in KRASG12C. (C). Progression-free survival and (D). Overall survival among patients with KRASG12C mutations with coalterations in KEAP1 and/or STK11. Abbreviations: KEAP1WT/STK11WT: wild type for both KEAP1 and STK11; KEAP1MUT/STK11WT: KEAP1-mutant, wild type for STK11; KEAP1WT/STK11MUT: wild type for KEAP1, STK11-mutant; KEAP1MUT/STK11MUT: mutant in both KEAP1 and STK11; mPFS: median progression-free survival; mOS: median overall survival.

Table 2.

Univariable analysis for progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with KRASG12C mutations.

| Covariate1 | N | Event N | HR | 95%CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 125 | 91 | 1.02 | 1.00-1.04 | .034 |

| Gender | 125 | 91 | .5 | ||

| Female | — | — | |||

| Male | 1.16 | 0.75-1.78 | .5 | ||

| Consolidated smoking history | 125 | 91 | .5 | ||

| Current or former | — | — | |||

| Never | 0.51 | 0.07-3.69 | .5 | ||

| Pack years smoked | 120 | 86 | 1.01 | 1.00-1.02 | .3 |

| Performance status (grouped) | 124 | 90 | <.001 | ||

| 0 | — | — | |||

| 1 | 1.33 | 0.81-2.20 | .3 | ||

| 2-3 | 4.72 | 2.10-10.6 | <.001 | ||

| Histology | 125 | 91 | .023 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | — | — | |||

| Other | 1.17 | 0.46-2.99 | .7 | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 4.40 | 1.53-12.7 | .006 | ||

| Baseline PD-L1 status | 114 | 84 | .5 | ||

| <1 | — | — | |||

| 1-49 | 0.74 | 0.44-1.26 | .3 | ||

| ≥50 | 0.74 | 0.38-1.41 | .4 | ||

| STK11 and KEAP1 mutations | 125 | 91 | .003 | ||

| KEAP1WT/STK11WT | — | — | |||

| KEAP1MUT/STK11MUT | 2.19 | 1.12-4.29 | .023 | ||

| KEAP1MUT/STK11WT | 2.79 | 1.49-5.24 | .001 | ||

| KEAP1WT/STK11MUT | 1.02 | 0.60-1.75 | >.9 |

Statistically significant P-values <.05.

1Adjusted for site stratification.

Abbreviations: KEAP1WT/STK11WT: wild type for both KEAP1 and STK11; KEAP1MUT/STK11WT: KEAP1-mutant, wild type for STK11; KEAP1WT/STK11MUT: wild type for KEAP1, STK11-mutant; KEAP1MUT/STK11MUT: mutant in both KEAP1 and STK11; PS: performance status; HR: hazard ratio, CI: confidence interval.

For the univariate analysis for OS, poor ECOG PS (P < .001), KEAP1MUT/STK11MUT (P = .009), and KEAP1MUT/STK11WT (P = .010) were associated with worse OS (Table 3). The co-mutation subgroups of KRASG12C patients had significantly different OS (P = .005) (Fig. 1D). Compared to the KEAP1WT/STK11WT subgroup (median OS: 21 months), patients with mutations in both KEAP1MUT/STK11MUT had the shortest median OS (6.9 months), followed by KEAP1mut/STK11WT (7.9 months). There was no difference in OS according to PD-L1 TPS (P = .766; Supplementary Fig. S3B).

Table 3.

Univariable analysis for overall survival (OS) in patients with KRASG12C mutations.

| Covariate1 | N | Event N | HR | 95%CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 138 | 72 | 1.01 | 0.98-1.03 | .6 |

| Gender | 138 | 72 | .6 | ||

| Female | — | — | |||

| Male | 1.14 | 0.71-1.85 | .6 | ||

| Consolidated smoking history | 138 | 72 | .8 | ||

| Current or former | — | — | |||

| Never | 0.77 | 0.11-5.62 | .8 | ||

| Pack years smoked | 132 | 68 | 1.00 | 0.99-1.01 | .7 |

| Performance status (grouped) | 137 | 71 | .001 | ||

| 0 | — | — | |||

| 1 | 1.31 | 0.74-2.29 | .4 | ||

| 2-3 | 4.63 | 1.99-10.8 | <.001 | ||

| Histology | 138 | 72 | .6 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | — | — | |||

| Other | 1.48 | 0.53-4.13 | .5 | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 1.76 | 0.42-7.31 | .4 | ||

| Baseline PD-L1 status | 127 | 67 | .9 | ||

| <1 | — | — | |||

| 1-49 | 0.86 | 0.47-1.56 | .6 | ||

| ≥50 | 0.94 | 0.46-1.95 | .9 | ||

| STK11 and KEAP1 mutations | 138 | 72 | .006 | ||

| KEAP1WT/STK11WT | — | — | |||

| KEAP1MUT/STK11MUT | 2.51 | 1.25-5.01 | .009 | ||

| KEAP1MUT/STK11WT | 2.34 | 1.22-4.46 | .010 | ||

| KEAP1WT/STK11MUT | 0.94 | 0.49-1.79 | .8 |

Statistically significant P-values <.05.

1Adjusted for site stratification.

Abbreviations: KEAP1WT/STK11WT: wild type for both KEAP1 and STK11; KEAP1MUT/STK11WT: KEAP1-mutant, wild type for STK11; KEAP1WT/STK11MUT: wild type for KEAP1, STK11-mutant; KEAP1MUT/STK11MUT: mutant in both KEAP1 and STK11; PS: performance status; HR: hazard ratio, CI: confidence interval.

In multivariable analysis for PFS, older age (P = .042), squamous cell histology (P = .008), poor ECOG PS (P < .001), and KEAP1MUT/STK11MUT (P = .015) or KEAP1MUT/STK11WT (P = 002) status were associated with worse PFS (Table 4). In multivariable analysis for OS, poor ECOG PS (P = .004) and KEAP1MUT/STK11MUT (P = .009) were associated with worse OS (Table 5). These results provide a real-world description of response rate, PFS, and OS to first-line chemo-immunotherapy in patients with KRASG12C mutations and show that coalterations in KEAP1 or STK11 were independently associated with worse survival.

Table 4.

Multivariable analysis for progression-free survival (PFS) for patients with KRASG12C mutations.

| Covariate1 | Event N | HR | 95%CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 90 | 1.02 | 1.00-1.05 | .042 |

| ECOG PS | 90 | .002 | ||

| 0 | — | — | ||

| 1 | 1.32 | 0.80-2.20 | .3 | |

| 2-3 | 4.32 | 1.87-9.99 | <.001 | |

| Histology | 90 | .028 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | — | — | ||

| Other | 0.92 | 0.34-2.51 | .9 | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 4.49 | 1.49-13.6 | .008 | |

| STK11 & KEAP1 mutations | 90 | .003 | ||

| KEAP1WT/STK11WT | — | — | ||

| KEAP1MUT/STK11MUT | 2.35 | 1.18-4.68 | .015 | |

| KEAP1MUT/STK11WT | 2.88 | 1.49-5.58 | .002 | |

| KEAP1WT/STK11MUT | 1.08 | 0.60-1.92 | .8 |

Statistically significant P-values <.05.

1Adjusted for site stratification.

Abbreviations: KEAP1WT/STK11WT: wild type for both KEAP1 and STK11; KEAP1MUT/STK11WT: KEAP1-mutant, wild type for STK11; KEAP1WT/STK11MUT: wild type for KEAP1, STK11-mutant; KEAP1MUT/STK11MUT: mutant in both KEAP1 and STK11; PS: performance status; HR: hazard ratio, CI: confidence interval.

Table 5.

Multivariable analysis for overall survival (OS) for patients with KRASG12C mutations.

| Covariate1 | Event N | HR | 95%CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECOG PS | 71 | .016 | ||

| 0 | — | — | ||

| 1 | 1.37 | 0.78-2.39 | .3 | |

| 2-3 | 3.71 | 1.51-9.10 | .004 | |

| STK11 and KEAP1 mutations | 71 | .020 | ||

| KEAP1WT/STK11WT | — | — | ||

| KEAP1MUT/STK11MUT | 2.52 | 1.26-5.02 | .009 | |

| KEAP1MUT/STK11WT | 1.90 | 0.95-3.84 | .072 | |

| KEAP1WT/STK11MUT | 0.90 | 0.46-1.75 | .8 |

1Adjusted for site stratification.

Abbreviations: KEAP1WT/STK11WT: wild type for both KEAP1 and STK11; KEAP1MUT/STK11WT: KEAP1-mutant, wild type for STK11; KEAP1WT/STK11MUT: wild type for KEAP1, STK11-mutant; KEAP1MUT/STK11MUT: mutant in both KEAP1 and STK11; PS: performance status; HR: hazard ratio, CI: confidence interval.

Comparative Outcomes to First-Line Chemo-Immunotherapy in Patients With KRASG12C Mutations Versus Non-G12C Mutations

As an exploratory objective, we next compared outcomes to chemo-immunotherapy between the KRASG12C and non-G12C KRAS subtypes. As previously described, patients in the KRASG12C group more frequently had a history of current or former smoking (P < .001) (Table 1). There were no other statistically significant differences between the KRASG12C and non-G12C groups (Table 1). Patient characteristics between the KRASG12C and non-G12C groups were similarly distributed across the MSK and DFCI sites (Supplementary Table S2). There was no significant difference in overall response rate between the KRASG12C and non-G12C groups (P = .13; Supplementary Fig. S4A). Patients treated with chemo-immunotherapy with KRASG12C mutations had significantly improved PFS (median PFS of 6.8 [95%CI, 5.5-10] vs 5.4 [95%CI, 4.6-6.3] months, P = .006) (Supplementary Fig. S4B) and OS compared to non-G12C KRAS subtypes (median OS 15 [95%CI, 11-28] vs 12 months [95%CI, 10-14], P = .012). (Supplementary Fig. S4C). This was no longer significant when analyzing outcomes among the different non-G12C subgroups. (objective response rate; Supplementary Fig. S4D) (PFS and OS; Supplementary Fig. S4E-4F). After adjusting for factors significant in the univariate analysis, KRASG12C mutation was not significantly associated with improved PFS (HR 0.82, 95%CI, 0.61-1.11, P = .2) (Supplementary Table S3), or OS (HR 0.55, 95%CI, 0.30-1.01, P = .053) (Supplementary Table S4).

Discussion

In this multicenter study of patients with KRASG12C alterations, we show that first-line chemo-immunotherapy can be beneficial for patients; however, clinical benefit derived from these therapies is heterogeneous. In patients with tumors-harboring KRASG12C mutations, concurrent KEAP1 and STK11 alterations were associated with worse outcomes after adjusting for other factors.

Two KRASG12C inhibitors are now FDA approved for use in patients who have been previously treated with at least one prior systemic therapy, representing a significant advance for the management of this disease. Owing to the early success of these agents in clinical trials, multiple first-line studies are now in development. Understanding anticipated benefit from current widely adopted first-line regimens in this patient population, as well as subgroups that may have particularly poor outcomes with available therapies is critical for success of these clinical trials. To date, there has been limited prospective data regarding chemo-immunotherapy outcomes in patients with tumors-harboring KRASG12C mutations. Previously presented subgroup analysis of the landmark KEYNOTE-189 study reported outcomes of 26 patients with KRASG12C alterations showing PFS of 11 months.10 The larger sample size presented here shows more modest outcomes in this patient population overall, however, highlights the nonuniformity of this group owing to comutation status and stratification for relevant comutations in first-line randomized studies should be considered to account for these differences.

While not a regimen included in our current study, the POSEIDON study evaluated combination chemotherapy with durvalumab and tremelimumab in patients with newly diagnosed NSCLC.17 Recently, a post hoc analysis was performed according to KRAS, STK11, and KEAP1 mutational status demonstrated durable benefit in the chemotherapy with durvalumab and tremelimumab group even among patients with STK11 and KEAP1 alterations,17 with similar findings from the Checkmate-9LA study evaluating chemotherapy, ipilimumab, and nivolumab combination.13

Our study found that concurrent KEAP1 and STK11 mutation was significantly associated with worse PFS and OS in KRASG12C patients, highlighting the need to develop more effective therapies in this high-risk subgroup. KEAP1 mutations lead to the activation of NFE2L2 pathway, protecting cells from the effects of numerous cytotoxic chemotherapies and, therefore, leading to chemoresistance.14 Although STK11 and KEAP1 alterations frequently co-occur, KEAP1 without concurrent STK11 mutations have been associated with worse outcomes to therapy in KRAS-driven malignancies and have been associated with a “colder” immune microenvironment within the tumor.6,15,16,18 Although we found a strong association with dual KEAP1 and STK11 or KEAP1 alterations alone, associations were not as strong for STK11 mutations alone. It is unclear if this is specific to chemotherapy-immunotherapy treatment, or if this finding was limited by sample size and further study on the specific role of STK11 alterations will be required. Moreover, given the sample size, we were limited the amount genetic mutations to explore with regard to association with outcome, and therefore, chose to focus on STK11 and KEAP1 mutations in an a priori hypothesis. For example, future work may examine impact of TP53 and other mutations and their implications in larger cohorts. Our relatively small sample size also hindered our ability to make definitive conclusions for subgroup analyses, such as with PDL1 subgroups, which will be of interest in larger prospective trials.

Given the modest activity of sotorasib, combination therapy may be the optimal path to incorporate G12C inhibitors for initial therapy. Currently, clinical trials of combinations of KRASG12C inhibitors with chemotherapy and others with immunotherapy are underway. It is known that KRASG12C inhibitors modulate the tumor microenvironment through activation of the interferon pathway,19 whether the addition of immunotherapy to these direct inhibitors upfront can transform these more hostile tumor microenvironments to those more amendable to immune activation remains to be seen. Initial reports from clinical trials suggest that while this approach may lead to durable responses, there is potential for significant toxicity which may limit the feasibility of this approach,20 though this may be more specific to sotorasib than other agents such as adagrasib.21 Combination of targeted therapy with chemotherapy is another potential approach, as the addition of cytotoxic therapy may prevent the emergence of persistor cells and emergence of subclonal populations with secondary RAS mutations driving resistance.5,22

We have previously shown that patients with KRASG12C alterations had nonsignificant trend toward lower rates of durable response to single-agent checkpoint blockade in patients with KRASG12C mutations (40% vs 56%, P = .07).6 Although the comparative effectiveness of chemo-immunotherapy in KRASG12C versus non-G12C was not the primary endpoint of our study, it is important to note that differing results from this study could be due to larger sample size, or the effect may not be as pronounced with the addition of chemotherapy. Prospective studies are awaited to clarify whether there is truly no difference in outcomes between patients with KRASG12C versus non-G12C in patients treated with chemo-immunotherapy. Our current study shows that patients with KRASG12C mutations are deriving benefit from chemo-immunotherapy regimens and further reinforces the potential for this active treatment in this subgroup of patients.

As data from prospective studies have been limited thus far, our study is the first to describe outcomes to chemo-immunotherapy in patients with KRASG12C alterations in the real-world setting; despite this, our study has several limitations inherent to retrospective studies. Although broad NGS testing was used at both academic institutions included in the analysis, differences in panels resulted in limited ability to incorporate tumor mutational burden into our analysis, a challenge that is not unique to our effort.23 KRASG12C inhibitors were not yet widely adopted for patients in this retrospective cohort, and future work will need to assess the impact of such therapies on OS and natural history of this disease particularly in a real-world setting.

In summary, we provide outcome data to chemo-immunotherapy in patients with advanced NSCLC with KRASG12C alterations, which will be useful in future clinical trial designs for patients with KRASG12C mutations. Careful consideration and randomized prospective clinical trials will be required to fully identify the optimal first-line therapy for patients with NSCLC-harboring KRASG12C mutations with potentially different approaches for patients with specific adverse prognostic features and concurrent mutations such as KEAP1 or STK11.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Arielle Elkrief, Department of Medicine, Thoracic Oncology Service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA; Human Oncology and Pathogenesis Program, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA; Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA.

Biagio Ricciuti, Lowe Center for Thoracic Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA.

Joao V Alessi, Lowe Center for Thoracic Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA.

Teng Fei, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA.

Hannah L Kalvin, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA.

Jacklynn V Egger, Department of Medicine, Thoracic Oncology Service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA.

Hira Rizvi, Department of Medicine, Thoracic Oncology Service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA.

Rohit Thummalapalli, Department of Medicine, Thoracic Oncology Service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA.

Giuseppe Lamberti, Lowe Center for Thoracic Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA.

Andrew Plodkowski, Department of Medicine, Thoracic Oncology Service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA.

Matthew D Hellmann, Department of Medicine, Thoracic Oncology Service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA; Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, USA.

Mark G Kris, Department of Medicine, Thoracic Oncology Service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA; Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, USA.

Maria E Arcila, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA.

Marina K Baine, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA.

Charles M Rudin, Department of Medicine, Thoracic Oncology Service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA; Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, USA.

Piro Lito, Human Oncology and Pathogenesis Program, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA; Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, USA.

Marc Ladanyi, Human Oncology and Pathogenesis Program, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA; Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA.

Adam J Schoenfeld, Department of Medicine, Thoracic Oncology Service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA; Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, USA.

Gregory J Riely, Department of Medicine, Thoracic Oncology Service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA; Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, USA.

Mark M Awad, Lowe Center for Thoracic Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA.

Kathryn C Arbour, Department of Medicine, Thoracic Oncology Service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA; Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, USA.

Funding

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health grants (cancer center grant P30-CA008748 and P01-129243 to MSKCC) and philanthropy (grants from John and Georgia DallePezze to MSKCC, The Ning Zhao & Ge Li Family Initiative for Lung Cancer Research and New Therapies, and the James A. Fieber Lung Cancer Research Fund). K.C.A. is supported by the LUNGevity Foundation. A.E. effort was funded by Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Royal College of Surgeons and Physicians of Canada Detweiler Travelling Fellowship, and the Henry R. Shibata Cedar’s Cancer Fellowship. M.M.A. effort was funded by V Foundation, Elva J. and Clayton L. McLaughlin Fund for Lung Cancer Research.

Conflict of Interest

Biagio Ricciuti has served on the advisory board for Regeneron. Matthew D. Hellman reported that A patent filed by Memorial Sloan Kettering related to the use of tumor mutational burden to predict response to immunotherapy (PCT/US2015/062208) is pending and licensed by PGDx; subsequent to the completion of this work, Dr. Hellman began as an employee (and equity holder) at AstraZeneca. Mark G. Kris reports honoraria from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Merus, and BerGenBio. Maria E. Arcila reported consulting for Janssen Global Services, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Roche, and Merck, honoraria/speaker fees from Biocartis, Invivoscribe, Physician Educational Resources, Peerview Institute for Medical Education, Clinical Care Options, and RMEI Medical Education. Adam J. Schoenfeld reports consulting/advising role to J&J, KSQ Therapeutics, BMS, Merck, Enara Bio, Perceptive Advisors, Oppenheimer and Co, Umoja Biopharma, Legend Biotech, Iovance Biotherapeutics, Prelude Therapeutics, Lyell Immunopharma, Amgen, and Heat Biologics, and research funding to institution from GSK, PACT Pharma, Iovance Biotherapeutics, Achilles Therapeutics, Merck, BMS, Harpoon Therapeutics, and Amgen. Gregory J. Riely reports that he has been an uncompensated consultant to Daiichi, Lilly, Pfizer, Merck, Verastem, Novartis, Flatiron Health, and Mirati, and institutional research support from Mirati, Lilly, Takeda, Merck, Roche, Pfizer, and Novartis. Mark M. Awad reports that he was a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Genentech, AstraZeneca, Mirati, Novartis, Blueprint Medicine, Abbvie, Gritstone, NextCure, and EMD Serono, and received research funding (to institute) from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Genentech, AstraZeneca, and Amgen. Kathryn C. Arbour has served as a consultant for AstraZeneca and Sanofi-Genzyme and has received institutional research support from Mirati, Revolution Medicines, and Genentech. The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: A.E., B.R., J.V.A., M.M.A., K.C.A. Provision of study material or patients: A.E., B.R., J.V.A., J.V.E., H.R., R.T., G.L., A.P., M.D.H., M.G.K., M.E.A., M.K.B., C.M.R., P.L., M.L., A.J.S., G.J.R., M.M.A., K.C.A. Collection and/or assembly of data: A.E., B.R., J.V.A., J.V.E., H.R., M.M.A., K.C.A. Data analysis and interpretation: A.E., B.R., J.V.A., T.F., M.M.A., K.C.A. Manuscript writing: A.E., B.R., J.V.A., T.F., H.L.K., M.M.A., K.C.A. Final approval of manuscript: all authors.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Ostrem JM, Peters U, Sos ML, Wells JA, Shokat KM.. K-Ras(G12C) inhibitors allosterically control GTP affinity and effector interactions. Nature. 2013;503(7477):548-551. 10.1038/nature12796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Skoulidis F, Li BT, Dy GK, et al. Sotorasib for lung cancers with KRAS p.G12C mutation. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(25):2371-2381. 10.1056/nejmoa2103695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Spira AI, Riely GJ, Gadgeel SM, et al. KRYSTAL-1: activity and safety of adagrasib (MRTX849) in patients with advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring a KRASG12C mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(16_suppl):9002-9002. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kim D, Xue JY, Lito P.. Targeting KRAS(G12C): from inhibitory mechanism to modulation of antitumor effects in patients. Cell. 2020;183(4):850-859. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Awad MM, Liu S, Rybkin II, et al. Acquired resistance to KRASG12C inhibition in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(25):2382-2393. 10.1056/nejmoa2105281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arbour KC, Rizvi H, Plodkowski AJ, et al. Treatment outcomes and clinical characteristics of patients with KRAS-G12C-mutant non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(8):2209-2215. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-4023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Arbour KC, Lito P.. Expanding the arsenal of clinically active KRAS G12C inhibitors. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(23):2609-2611. 10.1200/jco.22.00562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1–positive non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1823-1833. 10.1056/nejmoa1606774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gandhi L, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2078-2092. 10.1056/nejmoa1801005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gadgeel S, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Felip E, et al. LBA5-KRAS mutational status and efficacy in KEYNOTE-189: pembrolizumab (pembro) plus chemotherapy (chemo) vs placebo plus chemo as first-line therapy for metastatic non-squamous NSCLC. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(11):xi64-xi65. 10.1093/annonc/mdz453.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cheng DT, Prasad M, Chekaluk Y, et al. Comprehensive detection of germline variants by MSK-IMPACT, a clinical diagnostic platform for solid tumor molecular oncology and concurrent cancer predisposition testing. BMC Med Genomics. 2017;10(1):33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Garcia EP, Minkovsky A, Jia Y, et al. Validation of OncoPanel: a targeted next-generation sequencing assay for the detection of somatic variants in cancer. Arch Path Lab Med. 2017;141(6):751-758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paz-Ares L, Ciuleanu T-E, Cobo M, et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab combined with two cycles of chemotherapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 9LA): an international, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(2):198-211. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30641-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jeong Y, Hellyer JA, Stehr H, et al. Role of KEAP1/NFE2L2 mutations in the chemotherapeutic response of patients with non–small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(1):274-281. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-19-1237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Heist RS, Yu J, Donderici EY, et al. Impact of STK11 mutation on first-line immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) outcomes in a real-world KRAS G12C mutant lung adenocarcinoma cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(15_suppl):9106-9106. 10.1200/jco.2021.39.15_suppl.9106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aredo JV, Padda SK, Kunder CA, et al. Impact of KRAS mutation subtype and concurrent pathogenic mutations on non-small cell lung cancer outcomes. Lung Cancer. 2019;133:144-150. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brown S, Lavery JA, Shen R, et al. Implications of selection bias due to delayed study entry in Clinical Genomic Studies. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(2):287-291. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.5153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wickham H, Averick M, Bryan J, et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J Open Source Softw. 2019;4(43):1686. 10.21105/joss.01686 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sjoberg DD, KW, Curry M, Lavery JA, Larmarange J. Reproducable summary tables with the gtsummary package. R J. 2021;13(1):570-580. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Therneau TM, Grambsch PM.. Modeling survival data: Extending the Cox model. Springer, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kassambara A, Kosinski M, Biecek P.. survminer: Drawing Survival Curves using ‘ggplot2’ . R package version 0.4.9. 2021. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survminer

- 22. Zhao Y, Murciano-Goroff YR, Xue JY, et al. Diverse alterations associated with resistance to KRAS(G12C) inhibition. Nature. 2021;599(7886):679-683. 10.1038/s41586-021-04065-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vokes NI, Liu D, Ricciuti B, et al. Harmonization of tumor mutational burden quantification and association with response to immune checkpoint blockade in non-small-cell lung cancer. JCO Precis Oncol. 2019;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.