Abstract

Highlights

Increased fluoroquinolone resistance in the two most common non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) serotypes among travellers returning to the Netherlands.

Resistant Salmonella Enteritidis infections are most likely to be acquired abroad, specifically outside Europe.

This study highlights the importance of travel history when patients with NTS infections require empiric antimicrobial treatment.

Keywords: Enteric fever, AMR, fluoroquinolones, water sanitation, food hygiene, traveller’s diarrhoea

Non-typhoidal salmonellosis is the second most reported zoonosis in the European Union (EU) and European Economic Area (EEA). Approximately 91 000 human salmonellosis cases are reported annually in the EU/EEA despite long-standing harmonized Salmonella-control programmes in livestock. Moreover, in recent years, the incidence of human salmonellosis has stopped declining in the EU/EEA.1 In the Netherlands, Salmonella enterica serotypes Enteritidis (SE) and Typhimurium (ST), including its monophasic variant (STM), are the most common ones among human cases, with ST/STM showing higher antimicrobial resistance (AMR) levels than SE.2

International travel increases non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) infection risk among European travellers, especially when returning from relatively less industrialized countries with generally higher AMR levels.3,4 Some high-income countries reported increased AMR in travel-related NTS infections.5–7 However, the focus is often limited to one particular antimicrobial and NTS serotype. A broad overview of resistance levels to multiple antimicrobials provides insights for treating patients with travel-related NTS infection. Here, we assessed the prevalence of resistance to ten antimicrobials and their trends in SE and ST/STM isolates from international travellers returning to the Netherlands over a qw-year (pre-COVID19) period. Furthermore, we assessed associations between AMR and travel destination (within or outside the EU/EEA).

Culture-confirmed SE and ST/STM records with corresponding patient metadata from 2008 to 2019 were obtained from the Dutch national laboratory surveillance for Salmonella. Serotyping was performed using pre-screening with Luminex technique (Xmap Salmonella Serotyping Assay), followed by confirmation with classical agglutination according to the White-Kauffmann-Le Minor scheme. Further details about the surveillance were presented elsewhere.8 Patient metadata included sex (female/male), age (years), sampling date and international travel history (unknown, within or outside the EU/EEA). The ‘unknown’ travel history group included cases with infection acquired domestically (in the Netherlands) plus those with missing travel history. Thus, we could not differentiate between travel-related and domestic cases when travel history was unavailable. Season was defined as winter (December–February), spring (March–May), summer (June–August) or autumn (September–November) in the Netherlands.

AMR testing was performed as described previously.9 Briefly, broth microdilution was used to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). The MICs were interpreted as resistant/susceptible according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) epidemiological cut-offs (ECOFFs). Only those antimicrobials tested consistently over the study period were included: ampicillin, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, gentamicin, tetracycline, trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole. The overall annual resistance proportion per serotype was calculated as the total number of isolates resistant to at least one tested antimicrobial divided by the total number of isolates with that serotype tested for AMR.

Inter-annual trends in AMR among travellers and associations between AMR and travel history were tested using logistic regression with resistance proportion as a response variable. For the trend analysis, the sampling year was used as an explanatory variable and the annual number of reported isolates as offset to account for temporal changes in the number of isolates tested for AMR per serotype (the number of reported isolates did not decrease over the study period). Associations between AMR and travel history were first examined using univariable models. Significant associations (P < 0.05) were then selected for multivariable regression with adjustment for year, season, age, and sex. Relevance of adjustment was assessed by building multivariable models in a backward stepwise fashion where covariates with P > 0.20 were excluded.10 Only antimicrobials with more than five travel-related resistant isolates were assessed. Analyses were performed by antimicrobial and serotype. A Bonferroni correction for multiple testing was applied. Unless stated otherwise (i.e. Bonferroni correction), a 5% significance level was used.

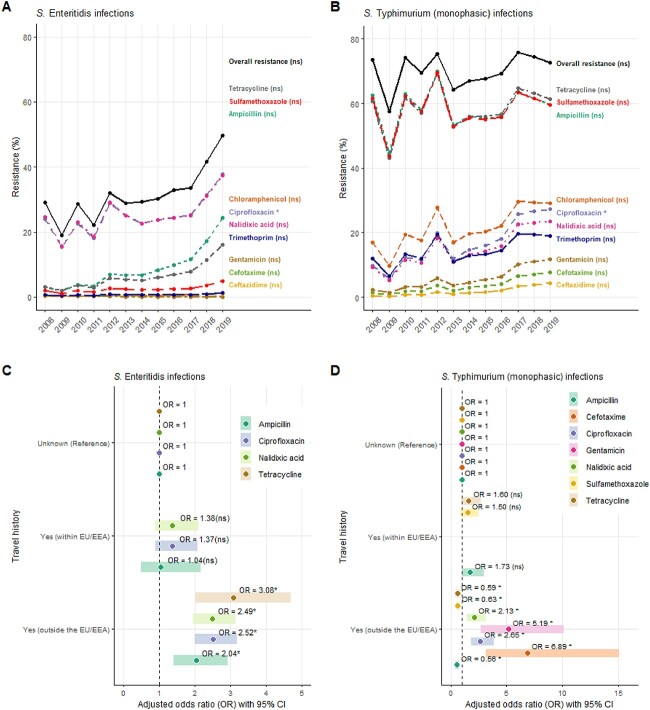

In total, 4069 SE and 5336 ST/STM isolates were included, 18 and 6% of which were travel-related, respectively (SE: 5% within and 13% outside EU/EEA; ST/STM: 2% within and 4% outside EU/EEA). Figure 1(A-B) shows the annual AMR trends among travel-related SE and ST/STM infections, overall and per antimicrobial. In general, AMR levels were higher among travellers with ST/STM than SE infection. Furthermore, AMR in travellers with SE infection increased by 13%, on average, every year (OR: 1.13; 95% CI: 1.08–1.18). This increase was driven by resistance to (fluoro)quinolones (ciprofloxacin and nalidixic acid), ampicillin, and tetracycline. As for ST/STM, AMR increased by 3%, on average, every year, but this was not significant (OR: 1.03; 95% CI: 0.95–1.12). This increase was driven by ciprofloxacin (OR: 1.16; 95% CI: 1.05–1.28) (available as Supplementary data at JTM online, Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

Annual trends of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in Salmonella Enteritidis (SE), Salmonella Typhimurium (ST) and S. monophasic Typhimurium (STM) infections among international travellers returning to the Netherlands, overall resistanceǂ and per antimicrobial (A, B). Associations between antimicrobial resistance in SE and ST/STM infections and international travel history in the Netherlands per antimicrobial (C, D). ǂOverall annual resistance proportion: calculated as the total number of isolates resistant to at least one tested antimicrobial divided by the total number of isolates tested for AMR per year. (C, D) Adjusted for year, season, age and sex. (C) Not possible to assess the association between tetracycline resistance in travel history (within EU/EEA) as well as cefotaxime, gentamicin and sulfamethoxazole resistance in travel history (within and outside EU/EEA) due to less than five counts (available as Supplementary data at JTM online, Supplementary Table 2). (D) Not possible to assess the association between nalidixic acid, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin and cefotaxime resistance in travel history (within EU/EEA) due to less than five counts (available as Supplementary data at JTM online, Supplementary Table 2). EU/EEA: European Union/European Economic Area. ns, not significant (references for P-values in Supplementary Tables 1 and 3. *Statistically significant

Travelling outside the EU/EEA was significantly associated with resistance to ampicillin, (fluoro)quinolones and tetracyclines in both SE and ST/STM, and with cefotaxime, gentamicin, and sulfamethoxazole resistance in ST/STM only (Figure 1C–D). For SE, resistance to ampicillin, (fluoro)quinolones, and tetracyclines was significantly higher among travellers returning from outside the EU/EEA compared with those with unknown travel history, which were assumed to be mostly domestic cases. However, these associations were not statistically significant among those travelling within the EU/EEA. Similarly, among ST/STM infections, resistance to (fluoro)quinolones, cefotaxime and gentamicin was significantly higher among those travelling outside the EU/EEA. In contrast to SE, resistance to ampicillin, tetracyclines and sulfamethoxazole in ST/STM infections was significantly lower among travellers returning from outside the EU/EEA compared with those with unknown travel history. These associations were not significant for those travelling within the EU/EEA (available as Supplementary data at JTM online, Supplementary Table 3). A major limitation of these analyses is the potential of misclassification bias in travel history, as the ‘unknown’ group may also contain some patients that did travel prior to symptoms onset. Moreover, whether such misclassification was constant over the study period is unknown. This might result in an underestimation of the associations towards the null.

In conclusion, we observed increased AMR levels among SE infections in international travellers returning to the Netherlands, particularly for ampicillin, (fluoro)quinolones and tetracycline. Our results also suggest that AMR among SE infections is significantly more likely to occur abroad, specifically outside the EU/EEA, whereas AMR levels among ST/STM infections have relatively less pronounced differences associated with travel history. This is largely consistent with previous reports in high-income countries5,7 and stresses the importance of considering travel history when patients with NTS infection require empiric antimicrobial treatment.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Linda Chanamé-Pinedo, Centre for Infectious Disease Control, National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), Bilthoven 3721 MA, the Netherlands; Institute for Risk Assessment Sciences, Utrecht University, Utrecht 3508 TC, the Netherlands.

Eelco Franz, Centre for Infectious Disease Control, National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), Bilthoven 3721 MA, the Netherlands.

Maaike van den Beld, Centre for Infectious Disease Control, National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), Bilthoven 3721 MA, the Netherlands.

Kees Veldman, Wageningen Bioveterinary Research (WBVR), Lelystad 8200 AB, the Netherlands.

Roan Pijnacker, Centre for Infectious Disease Control, National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), Bilthoven 3721 MA, the Netherlands.

Lapo Mughini-Gras, Centre for Infectious Disease Control, National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), Bilthoven 3721 MA, the Netherlands; Institute for Risk Assessment Sciences, Utrecht University, Utrecht 3508 TC, the Netherlands.

Funding

This study was supported by the research project ‘Assessing Determinants Of the Non-Decreasing Incidence of Salmonella’ (ADONIS) funded through the One Health European Joint Programme by the European Union’s Horizon-2020 Research and Innovation Programme (grant nr: 773830), and by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) with the project ‘Effects of decreaSing AntiBiotic use in animaLs on antibiotic reSistance in Human infections (EStABLiSH)’ (Grant number 541003002).

Author’s contribution

Linda Chanamé Pinedo (L.C.P.), Eelco Franz (E.F.) and Lapo Mughini-Gras (L.M.G.) conceived and designed the study. Maaike van den Beld (M.v.d.B.) and Kees Veldman (K.V.) produced the laboratory data. L.C.P. performed the statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. All authors have substantially contributed to critically reviewing the manuscript and approved it as submitted.

Conflict of Interest statement

None declared.

Data Availability

Further data can be obtained upon formal request and under strict supervision by the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) in the Netherlands.

Code availability

The code used for data analysis can be obtained upon request.

CRediT author statement

Linda Ernestina Chanamé Pinedo (Conceptualization-Equal, Formal analysis-Lead, Investigation-Equal, Methodology-Lead, Visualization-Lead, Writing—original draft-Lead, Writing—review and editing-Lead), Eelco Franz (Conceptualization-Equal, Formal analysis-Supporting, Funding acquisition-Lead, Investigation-Equal, Methodology-Supporting, Supervision-Equal, Writing—original draft-Supporting, Writing—review and editing-Supporting), Maaike van den Beld (Investigation-Supporting, Methodology-Supporting, Visualization-Supporting, Writing—review and editing-Equal), Kees Veldman (Funding acquisition-Equal, Investigation-Supporting, Methodology-Supporting, Supervision-Supporting, Visualization-Supporting, Writing—review and editing-Supporting), Roan Pijnacker (Formal analysis-Supporting, Investigation-Supporting, Methodology-Supporting, Supervision-Supporting, Visualization-Supporting, Writing—review and editing-Supporting), Lapo Mughini-Gras (Conceptualization-Equal, Formal analysis-Supporting, Funding acquisition-Equal, Investigation-Equal, Methodology-Equal, Supervision-Lead, Visualization-Supporting, Writing—original draft-Equal, Writing—review and editing-Equal).

References

- 1. European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Salmonella 2022. Available at: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/salmonella.

- 2. de Greeff S, Schoffelen A, Verduin C. NethMap 2021. Consumption of antimicrobial agents and antimicrobial resistance among medically important bacteria in the Netherlands in 2020 / MARAN 2021. Monitoring of Antimicrobial Resistance and Antibiotic Usage in Animals in the Netherlands in 2020. Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu (RIVM), 2021. 10.21945/RIVM-2021-0062. [DOI]

- 3. Manesh A, Meltzer E, Jin C et al. Typhoid and paratyphoid fever: a clinical seminar. J Travel Med 2021; 28:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Forster DP, Leder K. Typhoid fever in travellers: estimating the risk of acquisition by country. J Travel Med 2021; 28:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gunell M, Aulu L, Jalava J et al. Cefotaxime-resistant Salmonella enterica in travelers returning from Thailand to Finland. Emerg Infect Dis 2014; 20:1214–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rodríguez I, Rodicio MR, Guerra B, Hopkins KL. Potential international spread of multidrug-resistant invasive Salmonella enterica serovar enteritidis. Emerg Infect Dis 2012; 18:1173–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. O'Donnell AT, Vieira AR, Huang JY, Whichard J, Cole D, Karp BE. Quinolone-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis infections associated with international travel. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:e139–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Duijkeren E, Wannet WJ, Houwers DJ, van Pelt W. Serotype and phage type distribution of Salmonella strains isolated from humans, cattle, pigs, and chickens in the Netherlands from 1984 to 2001. J Clin Microbiol 2002; 40:3980–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van Pelt W, de Wit MA, Wannet WJ et al. Laboratory surveillance of bacterial gastroenteric pathogens in The Netherlands, 1991-2001. Epidemiol Infect 2003; 130:431–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mickey RM, Greenland S. The impact of confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. Am J Epidemiol 1989; 129:125–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Further data can be obtained upon formal request and under strict supervision by the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) in the Netherlands.