Abstract

Objectives

Parakinesia brachialis oscitans (PBO) is the involuntary movement of an otherwise paretic upper limb triggered by yawning. We describe the first case of PBO in a patient with a first manifestation of tumefactive multiple sclerosis (MS).

Methods

A 35-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a first episode of generalized seizure. Neurologic examination revealed left-sided spastic hemiparesis, predominantly affecting his upper limb. Brain MRI showed a tumefactive right hemisphere lesion consistent with demyelination. CSF did not document unmatched oligoclonal bands.

Results

Two weeks after admission and, despite being unable to voluntarily raise his left arm, the patient noticed a repeated and reproducible involuntary raise of this limb upon yawning, consistent with PBO. In the following weeks, the phenomenon diminished both in frequency and movement amplitude alongside motor recovery. An MRI performed 2 months later showed progression of the demyelinating lesion load and confirmed a diagnosis of MS.

Discussion

PBO is an example of autonomic voluntary motor dissociation and reflects the interplay between loss of cortical inhibition of the cerebellum in the setting of functional spinocerebellar pathways. Clinicians should be aware of this transient phenomenon which should not be mistaken as a chronic movement disorder or focal epileptic seizures.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

Recognizing the pattern of limb movement in the context of yawning as its predicable trigger is key in diagnosing PBO and sets it apart from potential confounders such as focal epileptic seizures. PBO may arise from any structural lesion disrupting descending cortico-ponto-cerebellar tracts in the setting of preserved spinocerebellar pathways.

Introduction

In some cases of hemiplegia, the initiation of yawning is associated with an involuntary upward movement of the otherwise paralyzed arm, a phenomenon described in the medical literature as parakinesia brachialis oscitans.

Previously, this rare phenomenon has been essentially reported in the context of stroke, namely those affecting the internal capsule region. We report a case of parakinesia brachialis oscitans in a patient presenting with a pseudotumoral form of multiple sclerosis.

Case Report

A 35-year-old man with a medical history of autism spectrum disorder and mild learning difficulties was brought to the hospital by ambulance after a first episode of generalized tonic-clonic seizure. The patient recalled noticing brief spells of intermittent left arm twitching in the 3 days leading up to hospital admission, followed by brief spells of transient left arm weakness, particularly affecting his grip and dexterity.

He denied concurrent headaches or any other symptoms suggestive of acute neurologic change. His family denied any change in his behavior or increased cognitive difficulties. On initial examination, he was alert and complained of severe back pain.

Neurologic examination revealed left-sided spastic hemiparesis, predominantly affecting his upper limb with a Medical Research Council (MRC) grade 3 weakness noted in left shoulder abduction and grade 2 in left wrist dorsiflexion. Reflexes were pronounced on the left, with extensor plantar response. The sensory and cerebellar examination results were normal, as was the cranial nerve examination. No involuntary movements or signs of epileptic activity were noted at this stage.

Because of the rapid onset of left-sided hemiparesis, stroke was suspected, and he was referred for acute CT of the head. This revealed an ill-defined right hemispheric supratentorial hypodensity with mild rim enhancement after contrast administration (Figure, A). A brain tumor or abscess was suspected, and the patient was immediately referred for a brain MRI. An EEG demonstrated focal right-sided frontal and temporal slowing with no epileptiform discharges.

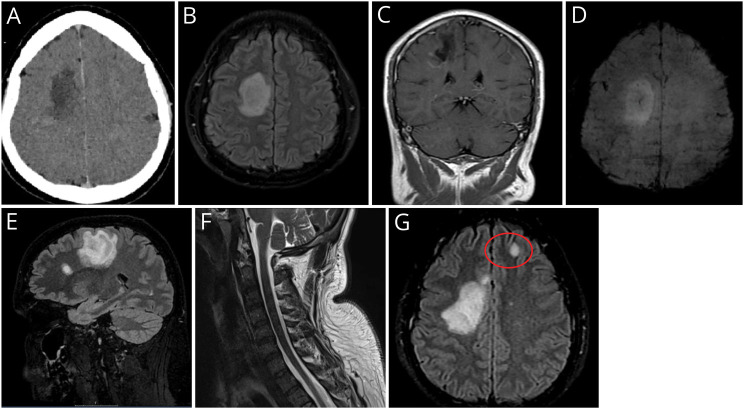

Figure. Imaging.

(A) Brain CT Scan Showing Ill-Defined Right Side Supratentorial Hypodensity With Marginal Contrast Enhancement. (B) T2/FLAIR-weighted axial sequence with a large oval-shaped hyperintensity in the subcortical frontal white matter of the right hemisphere, (C) with a peripheral incomplete rim enhancement seen in T1-weighted coronal section; (D) axial susceptibility-weighted sequence showing a classical central vein sign typical of primary demyelination; (E) sagittal T2/FLAIR-weighted sequence showing an additional oval-shaped demyelinating lesion perpendicular to the corpus callosum axis; (F) unremarkable cervical spinal cord appearances seen in sagittal STIR sequence; (G) follow-up MRI T2/FLAIR-weighted axial sequence displaying a new left frontal juxtacortical lesion (highlighted in red circle).

MRI confirmed a 47-mm oval-shaped hyperintense lesion in the right centrum semiovale on T2-weighted scans, with incomplete (C-shaped) peripheral enhancement after gadolinium-diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid injection (Figure, B and C). The lesion exerted subtle mass effect on the adjacent ventricular system. In addition, a smaller frontal juxtacortical lesion with the same characteristics was noted, both sharing a typical “central vein sign” visible on the susceptibility-weighted sequences (Figure, D and E). Both diffusion-weighted imaging and apparent diffusion coefficient sequences were negative for brain ischemia. Spinal MRI imaging showed no signal changes within the cord (Figure, F). CSF studies revealed <1 white blood cells/mm3. Glucose (3.8 mmol/L) and protein (279 mg/L) were within normal range. Testing for oligoclonal bands (OCB) was negative in the serum and CSF. The CSF neurofilament light (NfL) chain level was significantly elevated to 2527 pg/mL (age-adjusted reference <380 pg/mL). Serum AQP4 and MOG antibodies were negative. The presentation and findings at this stage were deemed compatible with a fulminant first manifestation of inflammatory demyelination not fulfilling McDonald 2017 criteria for a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (MS).

A diagnosis of clinically isolated syndrome of demyelination was made, and the patient was given oral methylprednisolone 500 mg for 5 days. He was subsequently enrolled into Attack MS, a placebo-controlled clinical trial of natalizumab within 14 days of symptom onset (NCT05418010).

Two weeks after symptom onset and shortly after discharge from inpatient admission, the patient reported that, despite being unable to hold up is left arm voluntarily, this would occur spontaneously on yawning (Video 1). He described that each episode of yawning would predictably produce an abduction movement of the arm with associated distal high amplitude postural left hand tremor, followed by a return to the resting position on yawning cessation. There was no associated left lower limb movement during these episodes. The patient was unable to reproduce the phenomenon of parakinesia brachialis oscitans (PBO) voluntarily by simulating yawning.

Left upper limb patterned movements triggered by yawning consistent with parakinesia brachialis oscitans, in a patient with tumefactive demyelination.Download Supplementary Video 1 (1.9MB, mp4) via http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/200204_Video_1

Over the following weeks, the patient noticed a gradual reduction in the frequency and amplitude of PBO, concurrent with an improvement of voluntary movements with his left-sided limbs. However, in the context of subacute worsening of his neurologic symptoms, PBO re-emerged. Follow-up brain MRI performed 2 months after clinical onset demonstrated new lesions accrual in a periventricular and juxtacortical distribution (Figure, G) in keeping with a diagnosis of MS. The original large right hemispheric lesion had reduced in size. The patient continues to be followed up in the context of his trial participation.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of PBO in a patient with MS. Involuntary raising of an otherwise paretic arm during yawning has been described in case reports dating back to 1844. However, the term parakinesia brachialis oscitans was only coined by Walusinski in 2005, in a study describing 4 patients presenting with ischemic strokes, all affecting the internal capsular region.1

Our patient had several presenting features unusual for MS, including epileptic seizures at presentation, the tumefactive nature of brain lesions detected, and the absence of OCB in the CSF. These are, however, not uncommon in patients with MS presenting with tumefactive demyelination, as previously described elsewhere.2,3 Further clinical and MRI follow-up in the context of a controlled clinical trial eventually ruled out potential differential diagnoses while fulfilling the McDonald 2017 diagnostic criteria for this condition.

PBO may occur within the first day after cerebral infarction or as late as 4 months after stroke onset2 and has been observed in paretic limbs during both the flaccid and spastic stages of poststroke recovery. These involuntary and patterned movements usually include a combination of abduction of the shoulder, flexion of the elbow, and extension of the fingers. Variants include lower limb involvement3 and associated tremor4 such as in our case. Some patients can deliberately suppress their PBO,5 which tends to disappear with recovery of motor function in the affected limb, usually within 6 months, although persistence of PBO beyond this point has been observed.3

The pathophysiology of PBO remains unclear.6,7 The most widely accepted explanation is that PBO reflects a proprioceptive loop activation, whereby the strong contraction of respiratory muscles during yawning generates a proprioceptive signal through the spinocerebellar tract that reaches the medullary lateral reticular nucleus. This in turn induces a motor signal through extrapyramidal pathways to cervical anterior horn cells, resulting in the involuntary movement of the affected upper limb. The interruption of the cortico-pontocerebellar pathway is thought to be essential for the manifestation of PBO because it enables proprioceptive loop disinhibition.

Although previously reported in the context of stroke only, our case demonstrates that PBO may also occur with large inflammatory demyelinating lesions. Mechanistically, we hypothesize that our patient's tumefactive lesion in the right hemisphere temporarily disrupted cortico-ponto-cerebellar and corticospinal pathways releasing subcortical structures from cortical inhibition, thereby enabling the proprioceptive loop disinhibition necessary for the spontaneous yawning-associated upper limb movement to be initiated through intact spinocerebellar pathways.

PBO is clinically relevant because it can potentially be mistaken for a focal epileptic seizure, particularly in an acute setting. Recognizing the highly stereotyped limb movement pattern in the context of yawning as its predicable trigger is key in diagnosing this condition.

Supplementary Material

Appendix. Authors

| Name | Location | Contribution |

| Manuel Salavisa, MD | Centre for Neuroscience, Surgery and Trauma, The Blizard Institute, Queen Mary University of London; Clinical Board Medicine (Neuroscience), The Royal London Hospital, Barts Health NHS Trust, United Kingdom; Neurology Department, Hospital Egas Moniz, Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Ocidental, Portugal | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Bader Mohamed, MD | Centre for Neuroscience, Surgery and Trauma, The Blizard Institute, Queen Mary University of London; Clinical Board Medicine (Neuroscience), The Royal London Hospital, Barts Health NHS Trust, United Kingdom | Major role in the acquisition of data |

| Kimberley Allen-Philbey | Centre for Neuroscience, Surgery and Trauma, The Blizard Institute, Queen Mary University of London; Clinical Board Medicine (Neuroscience), The Royal London Hospital, Barts Health NHS Trust, United Kingdom | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design |

| Andrea M. Stennett | Clinical Board Medicine (Neuroscience), The Royal London Hospital, Barts Health NHS Trust, United Kingdom | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Thomas Campion, MD | Clinical Board Medicine (Neuroscience), The Royal London Hospital, Barts Health NHS Trust, United Kingdom | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Klaus Schmierer, MD, PhD | Centre for Neuroscience, Surgery and Trauma, The Blizard Institute, Queen Mary University of London; Clinical Board Medicine (Neuroscience), The Royal London Hospital, Barts Health NHS Trust, United Kingdom | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

Study Funding

The authors report no targeted funding.

Disclosure

M. Salavisa has been generously funded by a 2022 European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS) fellowship grant. All other authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.Walusinski O, Quoirin E, Neau JP. La parakinésie brachiale oscitante [Parakinesia brachialis oscitans]. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2005;161(2):193-200. doi: 10.1016/s0035-3787(05)85022-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li J-Y, Wu L, Sun L-Q, Xiong J-M. Clinical and radiological characteristics of hemiplegic arm raising related to yawning in stroke patient. Med J Chin PLA. 2018;43(3):229-233. doi: 10.11855/j.issn.0577-7402.2018.03.09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Lima PM, Munhoz RP, Becker N, Teive HA. Parakinesia brachialis oscitans: report of three cases. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18(2):204-206. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farah M, Barcellos I, Boschetti G, Munhoz RP. Parakinesia brachialis oscitans: a case report. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2015;2(4):436-437. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.12234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chowdhury A, Datta AK, Biswas S, Biswas A. Parakinesia brachialis oscitans – a rare post-stroke phenomenon. Tremor Other Hyperkinetic Mov (N Y). 2022;12(1):6. doi: 10.5334/tohm.680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Töpper R, Mull M, Nacimiento W. Involuntary stretching during yawning in patients with pyramidal tract lesions: further evidence for the existence of an independent emotional motor system. Eur J Neurol. 2003;10(5):495-499. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2003.00599.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walusinski O, Neau JP, Bogousslavsky J. Hand up! Yawn and raise your arm. Int J Stroke 2010;5(1):21-27. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00394.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Left upper limb patterned movements triggered by yawning consistent with parakinesia brachialis oscitans, in a patient with tumefactive demyelination.Download Supplementary Video 1 (1.9MB, mp4) via http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/200204_Video_1