Abstract

Background

Pharmacists are increasingly incorporated into general practice teams globally and have been shown to positively impact patient outcomes. However, little research to date has focused on determining general practitioners’ (GPs’) perceptions of practice-based pharmacist roles in countries yet to establish such roles.

Objectives

To explore GPs’ perceptions towards integrating pharmacists into practices and determine if any significant associations were present between GPs’ perceptions and their demographic characteristics.

Methods

In June 2022, a survey was disseminated to GPs in Ireland via post (n = 500 in Munster region), Twitter, WhatsApp, and an online GP support and education network. Quantitative data were captured through multiple option and Likert-scale questions and analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Qualitative data were captured via free-text boxes, with the open comments analysed using reflexive thematic analysis.

Results

A total of 152 valid responses were received (24.6% response to postal survey). Overall, GPs welcomed the role of practice-based pharmacists and perceived that they would increase patient safety. Most agreed with practice pharmacists providing medicine information (98%) vs. 23% agreeing with practice pharmacists prescribing independently. Most agreed they would partake in a practice pharmacist pilot (78.6%). The free-text comments described current pressures in general practice, existing relationships with pharmacists, funding and governance strategies, potential roles for pharmacists in general practice, and anticipated outcomes of such roles.

Conclusion

This study provides a deeper understanding of GPs’ perceptions of integrating pharmacists into practices and the demographic characteristics associated with different perceptions, which may help better inform future initiatives to integrate pharmacists into practices.

Keywords: Pharmacist, general practice, general practitioners, survey, primary health care

KEY MESSAGES

GPs were welcoming and optimistic towards the role of a general practice-based pharmacist.

GPs were concerned about the impact of pharmacists in practices on workloads, indemnification, and potentially weakening patient-GP relationships.

GPs perceived advisory roles for pharmacists (e.g. medication reviews) as more acceptable than skills-based roles like independent pharmacist prescribing.

Introduction

General practice is under increasing pressure due to ageing populations, increasing multimorbidity, initiatives to move care from hospitals to primary care, and rising public expectations [1]. These challenges have been further compounded by difficulties with recruitment and retention of general practice staff [1]. To combat the rising tide of pressure in general practice, pharmacist integration into practice teams has occurred in several countries like Australia, but most notably in the United Kingdom [2,3].

Outcomes stemming from pharmacists’ interventions in general practices are shown in a systematic review from Tan et al., who conclude that they lead to improvements in patients’ blood pressure, glycosylated haemoglobin, cholesterol, and cardiovascular risk [4]. Furthermore, a systematic review from Hayhoe et al. concluded that pharmacists’ presence in practices had a positive impact on several healthcare utilisation outcomes, such as reduced emergency department visits, reduced visits to general practitioners (GPs), yet overall increased utilisation of primary care due to visits to pharmacists in practices [5]. Lastly, a recent review from Croke et al. showed that integrating pharmacists into practices, to optimise prescribing and health outcomes in patients with polypharmacy, probably reduces potentially inappropriate prescribing and the number of medications, appears to be cost-effective, but there is no apparent effect on patient outcomes [6].

In primary care in Ireland, most pharmacists currently work in community pharmacies, where they dispense medication and provide healthcare advice; they are mainly funded by the sale of products rather than provision of services [7]. GPs work in practices either by themselves or with other GPs or other allied healthcare professionals, and interact with community pharmacists by telephone or email to optimise patients’ pharmacotherapy [8]. GPs in Ireland also have access to drug interaction alerts as part of their practice computers’ software systems to increase prescribing safety [9]. Despite what is known of the outcomes of practice-based pharmacists, the role in Ireland – like many countries worldwide – is currently not established. There is a scarcity of studies that aim to explore GPs’ perceptions before attempts to integrate pharmacists into practices to pre-empt the concerns and considerations of GPs [10]. It is also unknown if there are any characteristics of GPs or their practices that affect GPs’ perceptions towards pharmacists’ roles that could be considered to tailor a practice-based pharmacist’s role to individual GPs and their practices. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to (1) explore GPs’ perceptions around integrating pharmacists into practices utilising a theory-informed mixed-methods survey and (2) determine if any significant associations were present between GPs’ perceptions and their demographic characteristics.

Methods

Study design and participants

A cross-sectional study utilising an electronic and paper-based survey sent to general practitioners in Ireland. GPs were eligible to partake in the study if they were currently practising as a GP in Ireland and had not previously worked with a pharmacist in general practice before or trained as a pharmacist before becoming a GP.

Ethics

Ethics approval to conduct this study was granted by the Social Research Ethics Committee, University College Cork. Participants gave their consent to partake before completing the anonymous survey.

Construction of the survey

The survey (Supplementary File 1) was initially constructed based on the findings from a qualitative evidence synthesis [10] and a semi-structured interview study that utilised the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) as part of its methods [11,12]. The survey was then reviewed and further developed by consensus discussion amongst research team members, which consisted of three pharmacists (two practising) and two practising GPs. The survey was then piloted for face validity and time to complete by five independent practising GPs, after which slight modifications to the survey were made. The final survey consists of several demographic, Likert Scale, multiple choice, ranking, binary, and open comment questions across four sections.

Survey dissemination

The survey was disseminated in June 2022 through multiple channels. A postal survey was sent to a random sample of 500/842 GPs in Munster, Ireland, on the 5th of June 2022. The survey was converted to an electronic version on Microsoft® Forms. A link to the survey was then distributed to members of GP Buddy (a national online GP support and educational network – https://www.gpbuddy.ie) via a post on the forum, GP fora on WhatsApp, and Twitter over the proceeding days (Supplementary File 2). A QR code linking to an electronic version of the survey was also placed on the front of the postal survey to give GPs the option to return their survey electronically by the 29th of July 2022.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterise the sample. Chi-squared (χ2) and Fisher’s Exact tests for independence were used to compare groups on categorical data. The survey items and demographics/other factors that were analysed in the independence tests are specified in Supplementary File 3. Post-hoc analysis was performed using the z-test to compare column proportions; adjustment for multiple testing using the Bonferroni method was also conducted. Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05. IBM® SPSS version 28 was used to perform descriptive and inferential statistics. Statistics were calculated based on the valid response for each question if data were missing.

Analysis of qualitative data from open-ended questions

Responses to the open-ended questions were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis [13,14]. This involved six steps: (1) familiarising ourselves with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing the report [13]. Open-ended question data were exported from the survey platform to a Microsoft® Excel spreadsheet before being transferred to Microsoft® Word, where the comment function was used to code participants’ responses. These six steps were carried out by one researcher (EH). Another team member (KD) also coded participants’ responses to offer an additional perspective on patterns of meaning within the data. EH then reviewed KD’s coding to reflect on any potential other interpretations of the data that may not have occurred to him while coding.

Reporting guidelines

This study was reported in compliance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement.

Results

A total of 152 GPs responded to the survey, with participant characteristics presented in Table 1. Of the 500 postal surveys distributed, 123 GPs completed and returned the survey (24.6%), with four completing via the QR code. A further 25 participants completed the survey via the links on Twitter (n = 19), GP Buddy (n = 5), and WhatsApp (n = 1). The main characteristics of the sample corresponded to a recent report from the Irish College of General Practitioners and suggest a good representation of the group across gender, age, practice size, and location [8].

Table 1.

Respondent demographics.

| Descriptor | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 77 (51.7%) |

| Male | 70 (47%) |

| Prefer not to say | 2 (1.3%) |

| Age range (in years) | |

| 30–39 | 24 (16.9%) |

| 40–49 | 48 (33.8%) |

| 50–59 | 42 (29.6%) |

| 60–69 | 24 (16.9%) |

| 70–79 | 4 (2.8%) |

| Experience range (in years) | |

| 0–9 | 22 (14.5%) |

| 10–19 | 43 (28.3%) |

| 20–29 | 41 (27%) |

| 30–39 | 34 (22.4%) |

| 40+ | 12 (7.9%) |

| Number of sessions* worked (per week) | |

| 1–2 | 2 (1.4%) |

| 3–4 | 8 (5.6%) |

| 5–6 | 33 (22.9%) |

| 7–8 | 63 (43.8%) |

| 9–10 | 38 (26.4%) |

| GMS± contractor | |

| Yes | 126 (85.7%) |

| No | 21 (14.3%) |

| GP partner | |

| Yes | 112 (75.7%) |

| No | 36 (24.3%) |

| Practice location | |

| Inner city | 16 (10.8%) |

| City suburb | 34 (23%) |

| Town | 72 (48.6%) |

| Village | 26 (17.6%) |

| Practice part of a primary care centre+ | |

| Yes | 34 (23.3%) |

| No | 112 (76.7%) |

| Size of your practice | |

| Small (<3000 patients) | 29 (19.7%) |

| Medium (3000–10,000 patients) | 98 (66.7%) |

| Large (>10,000 patients) | 20 (13.6%) |

| Number of GPs working in practice | |

| 1 GP | 28 (19%) |

| 2 GPs | 38 (25.9%) |

| 3 GPs | 43 (29.3%) |

| 4 GPs | 18 (12.2%) |

| ≥5 GPs | 20 (13.6%) |

| GP registrar in practice | |

| Yes | 51 (35.7%) |

| No | 92 (60.5%) |

| Nurse in practice | |

| Yes | 138 (96.5%) |

| No | 5 (3.5%) |

| Other HCP in practice | |

| Yes | 27 (18.9%) |

| No | 116 (81.1%) |

*Session: A 4-h block of work.

±GMS: General Medical Services scheme is a means/income-tested state-run programme that provides access to medical and surgical services for persons for whom acquiring such services would present undue hardship in Ireland [34].

+Primary care centre: purpose-built buildings that house several health and social care services from one site (e.g. GP, public health nurse, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, and a range of other services) [35].

Quantitative results of the survey

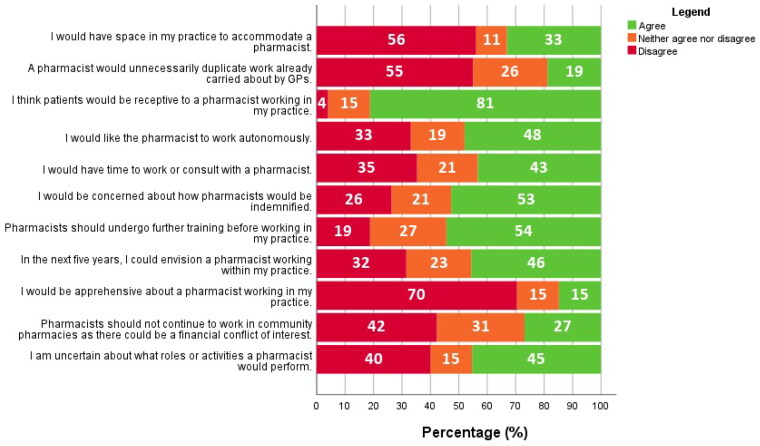

Preconceptions and planning for the role

Figure 1 shows GPs’ responses to Likert statements concerning preconceptions and planning for the role. GPs working in primary care centres were significantly more likely to agree that they would have space to accommodate a pharmacist in their practices (p < 0.05). A significant association was found between age and the response to ‘I am familiar with the training/education that pharmacists undergo’, with disagreements from 14% aged ≥60 years vs. 52% aged 30–39 years (p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

GPs’ responses to Likert statements concerning preconceptions and planning for pharmacists’ roles in general practices (percentage agreement shown in white figures).

When asked about funding, 84.6% thought the role being fully funded by the government was most feasible, 12.1% felt the role would only have to be partly funded by the government and 0.7% said it could be patient contribution. Most respondents (74.5%) agreed that if the government funded the role, the government-employed pharmacist should be shared between multiple practices, rather than practices hiring pharmacists and the government providing a grant for their salary (25.5%).

Regarding the frequency of pharmacist presence on site, 48.3% thought pharmacists should work in practices 1–2 days per week, 39.3% chose 1–2 days per month, 11.2% chose daily, and 1.1% were unsure of the optimal frequency. There was a significant association between practice size and optimal frequency of pharmacist presence in practices; 70% of GPs in large practices agreed pharmacists should be present 1–2 days per week compared to 45% and 40% in medium-sized and small practices, respectively (p < 0.05).

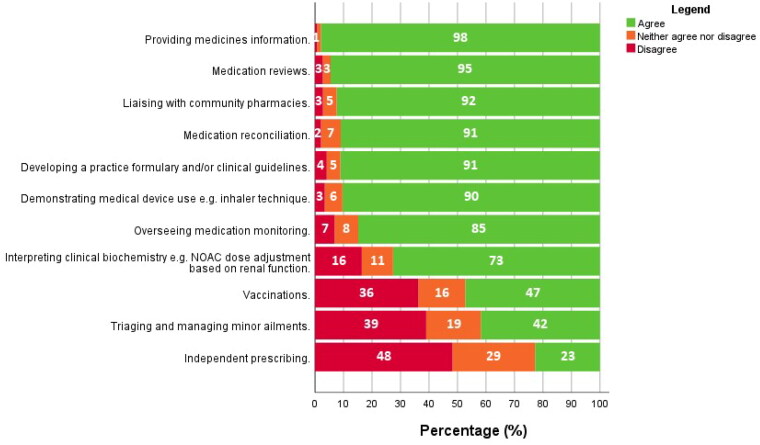

Roles and activities for pharmacists in general practice

Responses to Likert statements concerning the roles and activities of pharmacists in general practice are shown in Figure 2. There was a significant association between practice size and agreement with the role of pharmacists conducting medication reviews; 11.5% of those in smaller practices disagreed, vs. 0 and 1% in large and medium-sized practices, respectively (p < 0.05). There was a similar significant association between practice size and agreement with the role of ‘liaising with community pharmacies’; 12% in small practices disagreed with this role compared to 0% and 1.1% in large and medium-sized practices, respectively (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

GPs’ responses to Likert statements concerning potential roles or activities for pharmacists in general practices (percentage agreement shown in white figures).

There was a significant association between GPs’ experience and agreement with pharmacists developing practice guidelines/practice formularies; 63% of GPs with ≥40 years of experience agreed with pharmacists conducting this role compared to 93% of GPs with <40 years’ experience (p < 0.05). Not having a practice nurse was significantly associated with GPs’ views on pharmacists vaccinating in practices; 0% of those without a practice nurse agreed to this role compared to 50% with a practice nurse (p < 0.05).

GPs’ responses to the perceived impact on the roles and relationships of others in general practice are shown in Table 2. When GPs were asked what experience they would most like to see a pharmacist come to their practice with, 59.4% ranked experience in general practice first, 35.3% in community pharmacy first, and 5.3% in hospital pharmacy first. The mean number of years of experience GPs said they would like to see pharmacists coming to general practice with was three years minimum (range 0–10 years).

Table 2.

GPs’ responses to Likert statements concerning the potential impact on the role and relationships of others in practices.

| The role of the GP | The role of the practice nurse | The role of administrative staff | The role of the community pharmacist | GPs’ relationships with patients | Practice nurses’ relationships with patients | Community pharmacists’ relationships with patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Negative impact | 11 (7.6) | 9 (6.3) | 8 (5.6) | 15 (10.4) | 8 (5.5) | 7 (4.8) | 12 (8.5) |

| No impact | 17 (11.7) | 34 (23.8) | 55 (38.2) | 18 (12.5) | 56 (38.6) | 69 (47.6) | 45 (31.7) |

| Positive impact | 117 (80.7) | 100 (69.9) | 81 (56.3) | 111 (77.1) | 81 (55.9) | 69 (47.6) | 85 (59.9) |

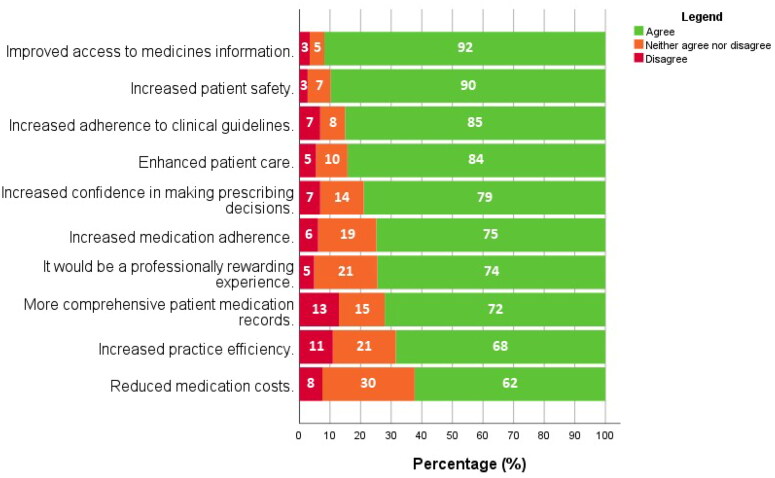

Potential outcomes of pharmacists in general practice

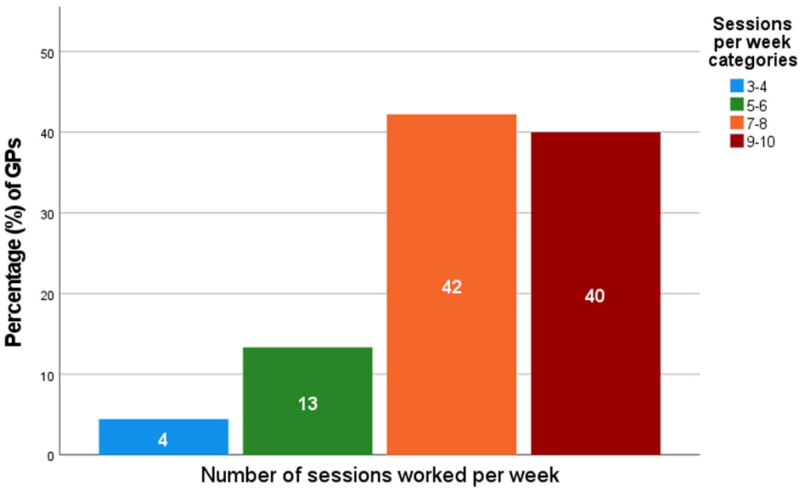

GPs’ responses to the perceived outcomes of pharmacists working in practices are shown in Figure 3. GPs’ perceived impact on the workloads of others is shown in Table 3. Practice (i) location in a primary care centre and (ii) size were significantly associated with perceived impact on administrative staff workloads (p < 0.05); (i) 40% not in a primary care centre felt administrative staff workloads would be increased compared to 14% based in primary care centres; (ii) 50% in small practices felt there would be an increase compared to 16% in large practices (p < 0.05). Single-handed GPs were significantly more likely to predict an increase in administrative staff workload compared to GPs in group practices (p < 0.05). GPs who work more sessions anticipated an increase in their workloads more often than GPs who work fewer sessions per week (p < 0.05), as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

GPs’ perceptions of potential outcomes of pharmacists in general practices (percentage agreement shown in white figures).

Table 3.

GPs’ perceived impact on the workloads of others.

| GPs n (%) |

Practice nurses n (%) |

GP admin staff n (%) |

Community pharmacists n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decreased workload | 67 (46.5) | 47 (32.4) | 45 (31.0) | 87 (61.7) |

| Increased workload | 48 (33.3) | 18 (12.4) | 50 (34.5) | 11 (7.8) |

| No effect on workload | 29 (20.1) | 80 (55.2) | 50 (34.5) | 43 (30.5) |

Figure 4.

Number of sessions worked per week by GPs (n = 45), who anticipate pharmacists in practices will increase their workloads (percentage agreement shown in white figures). Note: Two GPs reported working 1–2 sessions per week but neither anticipated an increase in their workloads.

When GPs were asked if the potential outcomes of pharmacists in practices justified the theoretical cost of employing them, 48.6% of GPs agreed, 24.7% disagreed, and 26.7% neither agreed nor disagreed. GPs were significantly more likely to agree that having pharmacists in practices would provide value for money if they agreed with pharmacists prescribing independently (p < 0.05), were not concerned about pharmacist indemnification (p < 0.05), and if they expected patients to be receptive to pharmacists (p < 0.05). Most GPs (78.6%) agreed they would participate in a future pilot study with a general practice-based pharmacist. Nearly all GPs with <10 years of experience (96%) agreed to partake in a trial compared to just 54.5% of those with >40 years’ experience (p < 0.05). GPs who approved of pharmacists performing independent prescribing were significantly more likely to agree to partake in a pilot (p < 0.05). Furthermore, GPs who agreed with the pharmacist interpretation of clinical biochemistry in practices were significantly more likely to participate in a pilot (p < 0.05).

Qualitative results of the survey

Comments in free text boxes were provided by 49.3% of survey participants (75/152). Reflexive thematic analysis of responses to open-comment questions led to the development of five overarching themes, described below and supported by representative quotations. Additional quotations are available in Supplementary File 4.

Theme 1 – Irish primary healthcare is suboptimal, and change is needed

GPs spoke about the extraordinary pressure faced in general practice in Ireland currently. They attributed this to several factors, including practice staff shortages, time constraints, increasing variety and complexity of medications, medication shortages, and the bureaucracy of the public health system. GPs believe that combining all those factors creates a challenging work environment that makes achieving optimal prescribing in practices difficult. GPs believe the change to the current suboptimal primary care system in Ireland is necessary and inevitable, but is unlikely to occur shortly.

‘GPs do not have adequate time to go through medications’ effects or potential effects when prescribing.’ [GP 12]

‘Our problem is that there are not enough GPs.’ [GP 76]

‘We have a lot to go to get there…’ [GP 23]

Theme 2 – Pharmacists are a useful resource and their role in primary care should be expanded

GPs cited the usefulness of close doctor-pharmacist collaborations in other practice settings and jurisdictions, e.g. in hospitals and the UK’s National Health Service. They also referred to their positive, mutually beneficial relationships with community pharmacists who regularly provide helpful pharmaceutical care input to enhance patient care. GPs were overall very willing in the future to engage with a general practice-based pharmacist role, where pharmacists should fully utilise their skills, and expressed interest in participating in a pilot study of placing pharmacists in general practice.

‘Would think it is a great initiative, have seen it working very well in a hospital setting.’ [GP 53]

‘Huge wealth of knowledge which may be untapped.’ [GP 89]

‘I think it’s worth a pilot study and seems like a worthwhile idea to pursue.’ [GP 6]

Theme 3 – Funding and governance of pharmacist roles in general practice

GPs were adamant they alone cannot fund pharmacist roles. The government should fund pharmacist roles in practices because they will benefit financially. Most GPs wanted to be autonomous and work with the pharmacist independently of the bureaucracy of the public health system; at the same time, GPs do not want to shoulder the additional responsibilities that come with employing another staff member (e.g. paying their salary and professional indemnity, organising maternity leave cover, and increased paperwork).

‘I would not under any circumstance entertain paying a pharmacist to work in my practice. It would certainly have to be funded by the Health Service Executive if it was to roll out.’ [GP 84]

‘I am already overburdened (and underpaid) with the work of a small business owner and would like to be a doctor.’ [GP 145]

‘I wish to maintain autonomy over who works in my surgery.’ [GP 99]

Theme 4 – What the role of a pharmacist in general practice would look like

GPs gave several examples of the roles they would expect pharmacists in practices to perform, including medication reviews, providing medicines information, medication monitoring, chronic disease management, and addiction services. GPs said they particularly see a role for pharmacists in high-risk areas, for which they gave examples of hospital discharge prescriptions and repeat prescribing. Role logistics were debated in the comments, with GPs weighing up the benefits of full-time vs. part-time roles, having a dedicated pharmacist working in a single practice or a pharmacist shared between practices, and having a pharmacist working remotely for practices were all raised as possibilities. Some felt general practice-specific training may be required for pharmacists to work in practices. GPs also said they would value evidence or examples of where the role was already working well to give them an idea of what the role looks like and its potential outcomes.

‘Pharmacist very helpful part of team for CDM reviews/medication review.’ [GP 38]

‘Repeat prescribing/hospital prescriptions are higher risk; help would be great.’ [GP 19]

‘Access to advice re medications needs to be full time.’ [GP 66]

‘Would need specific training,’ [GP 72]

Theme 5 – Anticipated outcomes from the role: Generally positive, with some unknowns

GPs surmised about potential outcomes associated with pharmacists working in practices. For patients, GPs felt pharmacist presence would encourage patient adherence and improve patient outcomes. GPs thought that pharmacists would rationalise and standardise current prescribing practices and, therefore, save money spent on medications by the government. With respect to practices, GPs felt pharmacists may improve practice efficiency and improve the reputations of GPs. Although outcomes were broadly anticipated as positive, GPs still wondered about potential negative impacts on practice staff workloads, increased litigation, and potentially weakened GP-patient relationships.

‘I would love to see primary care pharmacy formalised as a role to support both GPs + community pharmacists to better patient care and safety.’ [GP 76]

‘The monetary benefit would be to the Health Service Executive [Ireland’s publicly funded healthcare system] medications bill.’ [GP 17]

‘Working with a pharmacist would initially increase our workload because adjustments needed to be made.’ [GP 151]

‘This develops over time over many ‘low stake’ consultations. Delegate these away to give us more time for the ‘high stake’ consultations and we don’t have ‘the relationship’ which is often the ‘secret sauce’ in why GP works.’ [GP 107]

Discussion

Main findings

This novel mixed-methods survey study is the first to explore GPs’ perceptions of working with pharmacists in practices without having previously worked alongside them. This study reveals that GPs in Ireland were broadly welcoming and optimistic about the future role of a general practice-based pharmacist. GPs felt the role should be government-funded. While most GPs found advisory roles for pharmacists related to medication optimisation acceptable, they were less keen on independent pharmacist prescribing, vaccinating, or managing and triaging minor ailments in practices. While generally optimistic and welcoming towards the role, GPs had concerns regarding the potential impact of pharmacists in practices on the workloads of others, indemnification, and potential disruption to their relationships with patients.

Strengths and limitations

The survey content was based on the results of a qualitative evidence synthesis [10] and a TDF-informed interview study [12]; therefore, this study was able to explore the causal determinants of GPs’ perceptions of pharmacist integration into general practice to inform future interventions better. While the survey utilised a multi-modal dissemination approach to enhance its reach and response rate, responses received via electronic routes could have been more extensive in number. The postal survey also included a novel element of a QR code on its front page to allow GPs to respond electronically to the survey, which is a strategy we are not aware has been previously employed. While the postal survey’s response rate of 24.6% is somewhat low, this is still within the range of reported response rates (18–78%) from other GP surveys in Ireland [15–17]. Lastly, while Ireland’s primary care system does appear similar across several domains to multiple other European countries [18], the results may not be as generalisable or transferable to some regions.

Comparison with existing literature

The positive perception of the pharmacist’s role in practices reported by GPs in this study was mirrored in a recent survey of GPs in Northern Ireland, who currently work with practice-based pharmacists (PBPs) [19]. However, the reticence of GPs towards practice pharmacists independently prescribing in our study is surprising given that 62.4% of the surveyed GPs in Northern Ireland reported that their PBPs were qualified as independent prescribers, and 76.2% were prescribing for patients in general practices. GP reticence towards pharmacist prescribing has also been described elsewhere in the literature; for example, GPs working in private practices in a study by Saw et al. tended to view pharmacists as ‘medicines suppliers’ and were less comfortable with expanded pharmacist roles like prescribing [20]. Despite pharmacists with additional accreditation prescribing medications under GP supervision since 2003 (supplementary prescribing) and independently since 2006 in the UK [21], no legislative changes or additional accreditations have been enacted in Ireland. Furthermore, it has been shown that pharmacist prescribers prescribe safely, appropriately, and improve service accessibility [22,23]. GPs’ reticence towards pharmacist prescribing may negatively impact the potential clinical benefit of pharmacist roles in Irish general practices.

Concerns around funding pharmacists’ roles in practices are common in the literature, namely in Malaysia and Australia [20,24]. These concerns were apparent amongst our sample, who preferred the role to be fully government-funded. GPs were adamant in open comment responses about not funding the role. GPs in Ireland already report fears about the financial viability of general practice, so it is doubtful they can support the salary of an additional healthcare professional [25]. Moreover, as the GP respondents outlined, the government would likely be the primary financial benefactor of the role, as there would be reduced expenditure on medications resulting from deprescribing or medication optimisation. To date, cost-effectiveness analyses of the role show that the cost of deprescribed medications is the main financial justification for the role so far [26,27]. In the UK, where pharmacists have been successfully integrated into practices, government funding has been utilised to initiate and maintain pharmacist presence in practices [28]. Perhaps other countries seeking to establish the role should therefore model this UK funding strategy given the evidence that GPs are not the main financial benefactors of the role [26,27].

GPs’ willingness to partake in a pilot study was a welcome finding, given the current GP workforce and workload issues in Ireland [29]. Two initiatives, the iSIMPATHY project, and a Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI) pilot study have demonstrated the potential for a high return on investment, resolution of medication-related problems, effective interprofessional relationships, and significant acceptability to patients, practice staff, and GPs [26,27,30]. The qualitative evaluation of RCSI’s pilot study also showed GPs’ concern regarding funding, infrastructure, and potential impact on workload, which is akin to this study’s findings [30]. However, RCSI’s pilot study was small and included just four practices, while the iSIMPATHY project has been confined to select parts of the country. Given that most practices in Ireland remain unexposed to general practice pharmacists, it would be prudent to consider how a similar national pilot would be implemented at a national level, akin to the UK’s successful pilot in 2015 [2].

Implications

The potential workload impact of integrating pharmacists into practices must be more clearly deciphered in future research studies. Akhtar et al. have recently suggested that both qualitative and quantitative key performance indicators should be utilised to evaluate the overall impact of practice-based pharmacists, including reduced GP workload measured by their free hours, number and quality of medication reviews, reduced medication wastage, clinical audits, and patient satisfaction surveys [31]. In addition, GPs in this study needed to be more convinced of the value for money of the role. To date, studies in Ireland that have examined the cost-effectiveness of the role have done so to a limited extent, focusing on attributing cost savings of the role solely to deprescribed medications [26,27]. Future cost-effectiveness analyses should also consider cost savings associated with potentially improved prescribing, such as avoiding preventable adverse drug events and hospitalisations [32]. More definitive evidence of such cost savings may make it a more attractive endeavour for policymakers, GPs, and pharmacists.

Given that pharmacists in general practices may be potentially constrained by an inability to alter or initiate medications, policymakers, legislators, and higher education institutions in countries like Ireland should consider the development of pharmacist prescribing and the training thereof to better facilitate such roles in the future – perhaps similar to the 6-month training for a certificate in prescribing that nurses in Ireland have been able to undertake since 2007 [33]. In a recent Irish study exploring pharmacists’ perceptions of such integration into general practices, pharmacists have also identified the need for a pharmacist prescribing course to facilitate their prescribing in general practices [18]. The GPs’ reticence to pharmacist prescribing identified in this study must also be explored further. A phased introduction of pharmacist prescribing would be more acceptable to GPs in Ireland (e.g. similar to the UK’s approach: before independent prescribing, having supplementary prescribing dependent on a prior diagnosis and an agreed pharmacist-GP clinical management plan [21]). Policymakers should also be cognisant of the need for adequate funding to support pharmacists’ roles in practices and ensure an adequate pharmacist workforce is available to support these general practice roles through liaising with pharmacist regulatory bodies and higher education institutions.

Conclusion

GPs surveyed in this study were mostly optimistic and welcoming towards pharmacists working in practices. However, this study also reveals GPs’ concerns about how pharmacist roles will be funded, indemnified, and impact the workloads of others. This research has created a greater understanding of how GP and general practice characteristics impact GPs’ perceptions of integrating pharmacists into practices. This may help better inform future initiatives to integrate pharmacists into practices – ultimately to enhance patient care, support GPs, and utilise the pharmacists’ skillsets to deliver the highest quality primary care models possible.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Dr. Michael Cronin (University College Cork) for input into the sampling strategy of the postal survey. Dr. Duncan Babbage for providing us with a Microsoft Word macro to facilitate reflexive thematic analysis of our open comment data.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Irish Research Council PhD Scholarship (Grant code: IRC GOIPG/2020/1070).

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Baird B, Charles A, Honeyman M, et al. Understanding pressures in general practice. Lond Kings Fund. 2016;4–6. [cited 2021 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/Understanding-GP-pressures-Kings-Fund-May-2016.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyd M, Mann C, Anderson C, et al. Evaluation of the NHS England phase 1 pilot: clinical pharmacists in general practice. Int J Pharm Pract. 2019;27:4–5. [cited 2021 Sep 1]. Available from: https://nottingham-repository.worktribe.com/output/1835734/evaluation-of-the-nhs-england-phase-1-pilot-clinical-pharmacists-in-general-practice [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan ECK, Stewart K, Elliott RA, et al. Stakeholder experiences with general practice pharmacist services: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2013;3:1–8. [cited 2021 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&id=L369994456&from=export [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan ECK, Stewart K, Elliott RA, et al. Pharmacist services provided in general practice clinics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2014;10(4):608–622. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayhoe B, Cespedes JA, Foley K, et al. Impact of integrating pharmacists into primary care teams on health systems indicators: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(687):e665–e674. doi: 10.3399/bjgp19X705461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croke A, Cardwell K, Clyne B, et al. The effectiveness and cost of integrating pharmacists within general practice to optimize prescribing and health outcomes in primary care patients with polypharmacy: a systematic review. BMC Prim Care. 2023;24(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s12875-022-01952-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore T, Kennedy J, McCarthy S.. Exploring the general practitioner–pharmacist relationship in the community setting in Ireland. Int J Pharm Pract. 2014;22(5):327–334. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Kelly M, Teljeur C, O’Kelly F, et al. Structure of General Practice in Ireland [Internet]. Trinity College Dublin; 2016. p. 52. [cited 2022 Aug 26]. Available from: https://www.tcd.ie/medicine/public_health_primary_care/assets/pdf/structure-of-general-practice-2016.pdf

- 9.Medical Protection Society . Prescribing. GP Trainee. 2012;5:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurley E, Gleeson LL, Byrne S, et al. General practitioners’ views of pharmacist services in general practice: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Fam Pract. 2022;39(4):735–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S.. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurley E, Walsh E, Foley T, et al. General practitioners’ perceptions of pharmacists working in general practice: a qualitative interview study. Fam Pract. 2023;40(2):377–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braun V, Clarke V.. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braun V, Clarke V.. Thematic analysis: a practical guide. 1st ed. Los Angeles, CA; London; New Delhi; Singapore; Washington (DC); Melbourne: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Power B, Bury G.. A survey of general practitioner’s opinion on the proposal to introduce “treat and referral” into the Irish emergency medical service. Ir J Med Sci. 2020;189(4):1457–1463. doi: 10.1007/s11845-020-02224-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Somal K, Foley T.. General practitioners’ views of advance care planning: a questionnaire-based study. Ir J Med Sci. 2022;191(1):253–262. doi: 10.1007/s11845-021-02554-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ciblis AS, Butler M-L, Bokde ALW, et al. The use of neuroimaging in dementia by Irish general practitioners. Ir J Med Sci. 2016;185(3):597–602. doi: 10.1007/s11845-015-1315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kringos D, Boerma W, Bourgueil Y, et al. The strength of primary care in Europe: an international comparative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(616):e742–e750. doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X674422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasan Ibrahim AS, Barry HE, Hughes CM.. General practitioners’ experiences with, views of, and attitudes towards, general practice-based pharmacists: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Prim Care. 2022;23(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s12875-021-01607-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saw PS, Nissen L, Freeman C, et al. Exploring the role of pharmacists in private primary healthcare clinics in Malaysia: the views of general practitioners. Pharm Pract Res. 2017;47(1):27–33. doi: 10.1002/jppr.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baqir W, Miller D, Richardson G.. A brief history of pharmacist prescribing in the UK. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2012;19(5):487–488. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2012-000189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Latter S, Smith A, Blenkinsopp A, et al. Are nurse and pharmacist independent prescribers making clinically appropriate prescribing decisions? An analysis of consultations. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2012;17(3):149–156. doi: 10.1258/JHSRP.2012.011090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Latter S, Blenkinsopp A, Smith A, et al. Evaluation of nurse and pharmacist independent prescribing. Keele: University of Southampton & Keele University; 2010. p. 389. [cited 2023 Oct 12]. Available from: https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/184777/3/ENPIPfullreport.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan ECK, Stewart K, Elliott RA, et al. Integration of pharmacists into general practice clinics in Australia: the views of general practitioners and pharmacists. Int J Pharm Pract. 2014;22(1):28–37. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins C, O’Riordan M. The future of Irish general practice: Irish College of General Practitioners; 2015. p. 21. [cited 2023 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.icgp.ie/go/research/reports_statements/6E57DF46-F169-6861-F80D10841ABFAD72.html

- 26.Cardwell K, Smith SM, Clyne B, et al. Evaluation of the general practice pharmacist (GPP) intervention to optimise prescribing in Irish primary care: a non-randomised pilot study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e035087. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Health Service Executive (HSE) iSIMPATHY Project Management Team . iSIMPATHY Interim Report April 2022 [Internet]; 2022. p. 1–21. Report No.: 1. [cited 2022 May 3]. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10147/631776

- 28.NHS England and NHS Improvement . Network Contract Directed Enhanced Service: additional roles reimbursement scheme guidance [Internet]; 2019. p. 27. Report No.: 1. [cited 2022 Aug 29]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/network-contract-des-additional-roles-reimbursement-scheme-guidance-december2019.pdf

- 29.Health Service Executive (HSE) . Medical workforce planning future demand for general practitioners [Internet]; 2015. p. 1–52. [cited 2022 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.hse.ie/eng/staff/leadership-education-development/met/plan/gp-medical-workforce-planning-report-sept-2015.pdf

- 30.James O, Cardwell K, Moriarty F, et al. Pharmacists in general practice: a qualitative process evaluation of the general practice pharmacist (GPP) study. Fam Pract. 2020;37(5):711–718. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmaa044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akhtar N, Hasan SS, Babar Z-U-D.. Evaluation of general practice pharmacists’ role by key stakeholders in England and Australia. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2022;13(1):31–40. doi: 10.1093/jphsr/rmac002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deeks LS, Kosari S, Naunton M.. Clinical pharmacists in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2018;68(672):320–320. doi: 10.3399/bjgp18X697625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Health Service Executive (HSE) , Department of Health & Children , An Bord Altranais, et al. The introduction of nurse and midwife prescribing in Ireland: an overview [Internet]; 2007. p. 23. [cited 2022 Oct 4]. Available from: https://www.pna.ie/images/ncnm/Intro_prescribing_oct07.pdf

- 34.Keane C, Regan M, Walsh B.. Failure to take-up public healthcare entitlements: evidence from the medical card system in Ireland. Soc Sci Med. 2021;281:114069. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Health Service Executive (HSE) . Primary care centers [Internet]. HSE.ie. [cited 2022 May 12]. Available from: https://www2.hse.ie/apps/services/primarycarecenters.aspx

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.