Significance

This study elucidates the dynamic collaboration between lipid droplets and peroxisomes, which store and catabolize fats, respectively. We uncovered a role for a ubiquitin-protein ligase, MIEL1, in ubiquitination and timely degradation of lipid droplet coat proteins in the reference plant Arabidopsis thaliana. MIEL1 localized to peroxisomes, providing a mechanism to promote coat protein degradation specifically in peroxisome-proximal lipid droplets. Because PIRH2, the human MIEL1 homolog, also localized to peroxisomes when expressed in plants, these findings suggest a role for PIRH2 beyond transcription factor regulation and provide insights into peroxisome–lipid droplet interactions throughout eukaryotes.

Keywords: Arabidopsis thaliana, E3 ubiquitin ligase, lipid droplet, peroxisome, PIRH2

Abstract

Lipid droplets are organelles conserved across eukaryotes that store and release neutral lipids to regulate energy homeostasis. In oilseed plants, fats stored in seed lipid droplets provide fixed carbon for seedling growth before photosynthesis begins. As fatty acids released from lipid droplet triacylglycerol are catabolized in peroxisomes, lipid droplet coat proteins are ubiquitinated, extracted, and degraded. In Arabidopsis seeds, the predominant lipid droplet coat protein is OLEOSIN1 (OLE1). To identify genes modulating lipid droplet dynamics, we mutagenized a line expressing mNeonGreen-tagged OLE1 expressed from the OLE1 promoter and isolated mutants with delayed oleosin degradation. From this screen, we identified four miel1 mutant alleles. MIEL1 (MYB30-interacting E3 ligase 1) targets specific MYB transcription factors for degradation during hormone and pathogen responses [D. Marino et al., Nat. Commun. 4, 1476 (2013); H. G. Lee and P. J. Seo, Nat. Commun. 7, 12525 (2016)] but had not been implicated in lipid droplet dynamics. OLE1 transcript levels were unchanged in miel1 mutants, indicating that MIEL1 modulates oleosin levels posttranscriptionally. When overexpressed, fluorescently tagged MIEL1 reduced oleosin levels, causing very large lipid droplets. Unexpectedly, fluorescently tagged MIEL1 localized to peroxisomes. Our data suggest that MIEL1 ubiquitinates peroxisome-proximal seed oleosins, targeting them for degradation during seedling lipid mobilization. The human MIEL1 homolog (PIRH2; p53-induced protein with a RING-H2 domain) targets p53 and other proteins for degradation and promotes tumorigenesis [A. Daks et al., Cells 11, 1515 (2022)]. When expressed in Arabidopsis, human PIRH2 also localized to peroxisomes, hinting at a previously unexplored role for PIRH2 in lipid catabolism and peroxisome biology in mammals.

Lipid droplets are cytoplasmic organelles that house neutral lipids in eukaryotes (1–3). Neutral lipids, including sterol esters and fatty acids esterified to triacylglycerol (TAG), are sequestered in lipid droplets to avoid cytotoxicity (4) and to store fixed carbon (5). Lipid droplet biogenesis and catabolism respond dynamically to cellular energy needs. For example, oilseed plants, including the reference plant Arabidopsis thaliana and crops such as canola, catabolize oil stored in seed lipid droplets to fuel growth before photosynthesis begins. Similarly, lipid droplets support pollen tube growth (5) and light-induced stomatal opening (6). Lipid droplets also promote survival following various stresses, likely serving as sinks for cytotoxic fatty acids generated during membrane remodeling (5). Despite the critical importance of lipid droplets in plant and animal biology, the molecular mechanisms controlling lipid droplet dynamics are incompletely understood.

The neutral lipid core of the lipid droplet is encased by a phospholipid monolayer studded with coat proteins that vary among organisms and tissues (2). In mammals, perilipins decorate lipid droplets and regulate lipolysis (7). In plants and some green algae, lipid droplets are studded with oleosins (5, 8), which stabilize the organelle and prevent lipid droplet coalescence (9, 10). Oleosins are small (15 to 25 kDa) proteins (8, 11) with a central hydrophobic hairpin of ~70 residues between two amphipathic regions (12). Interestingly, oleosins are the only lipid droplet–associated proteins with hydrophobic regions long enough to extend into the lipid droplet core (1). Oleosins are the predominant lipid droplet coat proteins in seeds and pollen (3), tissues that can survive desiccation, and comprise 75 to 80% of the protein in seed lipid droplets (13, 14). In Arabidopsis, OLE1 (At4g25140) is the most abundant (13, 14) of the five seed oleosins (OLE1–OLE5). Despite differences in coat proteins, aspects of lipid droplet dynamics are conserved across kingdoms. For example, the fat storage–inducing transmembrane (FIT) protein FIT2, which is essential for lipid droplet biogenesis in mammals, induces lipid droplet biogenesis when expressed in leaves (15).

As fats stored in lipid droplets are catabolized, coat proteins are degraded (5). Mammalian perilipin is degraded predominantly via chaperone-mediated autophagy (16), although some perilipins are ubiquitinated and degraded by the ubiquitin–proteasome system (17, 18). As Arabidopsis seedlings begin mobilizing TAG, oleosins undergo various modifications, including OLE1–OLE4 ubiquitination and OLE5 phosphorylation (19). TAG is mostly catabolized and oleosins are largely degraded by 4 d after sowing (19). OLE1 and OLE2 (At5g40420) are mono- and di-ubiquitinated on the C-terminal amphipathic helix (19), but the responsible ubiquitin-protein ligase has not been reported. Plant UBX-domain containing protein10 (PUX10) binds to ubiquitinated oleosins and recruits the Cell Division Cycle 48A (CDC48A) ATPase for oleosin extraction and subsequent proteasomal degradation in a process resembling endoplasmic reticulum–associated protein degradation (20, 21).

Lipid droplets associate closely with peroxisomes (22). Peroxisomes are membrane-bound organelles that house diverse and often oxidative metabolic reactions (including fatty acid β-oxidation) and enzymes that neutralize hydrogen peroxide (23, 24). In plants, peroxisomes assist in photorespiration and in phytohormone (auxin and jasmonate) production (25, 26). Proteins destined for the peroxisome lumen are synthesized in the cytosol and imported into the organelle with the assistance of peroxins (PEX proteins). PEX5 is a shuttling receptor for peroxisome-targeting signal 1 (PTS1) cargo proteins that associates with the docking complex (26) and accompanies cargo into the peroxisomal lumen (27, 28). After delivering cargo, PEX5 is ubiquitinated near its N terminus by a triad of ubiquitin-protein ligases (PEX2, PEX10, and PEX12) in the Really Interesting New Gene (RING) family that forms a PEX5 retrotranslocation channel (29). This complex collaborates with a peroxisome-tethered ubiquitin-conjugating (UBC) enzyme (PEX4) in plants and yeast (30–32) or a cytosolic UBC in metazoans (33). Monoubiquitinated PEX5 is extracted from the peroxisomal membrane by the retrotranslocation machinery and deubiquitinated in the cytosol to allow reuse in further import cycles (26).

During germination, lipases, including the SUGAR-DEPENDENT1 (SDP1) peroxisome-associated lipase (34, 35), hydrolyze lipid droplet TAG. The released fatty acids are transported into peroxisomes by PXA1 (36, 37), which may facilitate peroxisome–lipid droplet interactions (22, 38). As lipids are β-oxidized, peroxisomes acquire intralumenal vesicles (ILVs) (39), perhaps providing a platform for enzymes β-oxidizing water-insoluble long-chain fatty acids. Despite the importance of regulated lipid release and catabolism in fueling seedling growth, little is known about degradation of the nonlipid components of plant lipid droplets, including oleosin, or how this degradation impacts lipid mobilization.

In this study, we employed forward genetics to identify genes involved in oleosin degradation. We recovered four alleles of MIEL1 (MYB30-interacting E3 ligase 1), which encodes a ubiquitin-protein ligase not previously implicated in lipid droplet or peroxisome dynamics. In miel1 mutants, oleosin ubiquitination was decreased, oleosins were stabilized, and TAG degradation was slowed. When overexpressed, MIEL1 increased oleosin degradation, yielding very large lipid droplets. Moreover, tagged MIEL1 localized to peroxisomes. Our data suggest that MIEL1 ubiquitinates seed oleosins in the vicinity of a peroxisome for proteasomal degradation during germination. The human MIEL1 homolog (PIRH2; p53-induced protein with a RING-H2 domain) regulates p53 and promotes tumorigenesis (40). Like MIEL1, PIRH2 localized to peroxisomes when expressed in Arabidopsis, hinting at previously unexplored roles for PIRH2 in humans.

Results

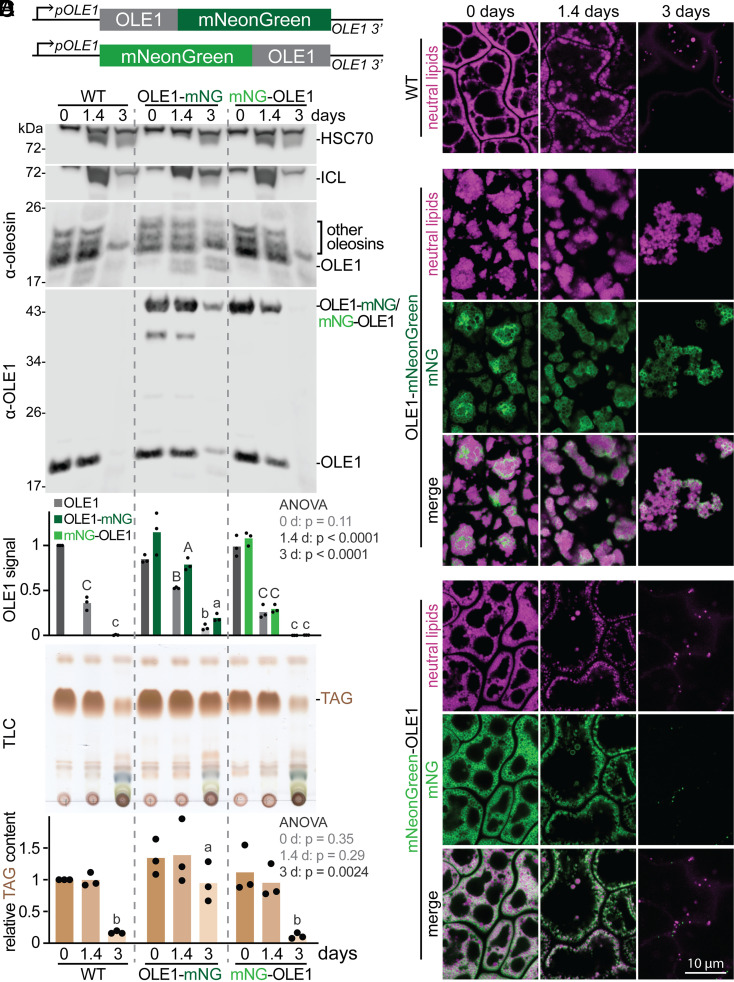

pOLE1:mNeonGreen–OLE1 Is a Biologically Neutral Reporter Line.

As the fats stored in lipid droplets are catabolized to fuel seedling growth (Fig. 1C), the oleosins studding the lipid droplet are degraded (Fig. 1B) (19). To investigate oleosin and lipid droplet dynamics in developing Arabidopsis seedlings, we generated transgenic plants expressing fluorescently tagged OLE1. We fused mNeonGreen to the OLE1 genomic sequence (including the single OLE1 intron) flanked by its native 3′ and 5′ sequences (pOLE1:OLE1–mNeonGreen; Fig. 1A) and transformed wild-type plants. In transgenic seedlings expressing OLE1–mNeonGreen, the reporter was degraded in parallel with untagged OLE1 (Fig. 1B). However, degradation of OLE1, OLE1–mNeonGreen, and other oleosins was delayed compared to OLE1 and other oleosins in wild-type seedlings (Fig. 1B). Along with slowed oleosin degradation, these lines displayed delayed triacylglycerol (TAG) catabolism (Fig. 1C) and aberrant lipid droplet clustering in seeds and seedlings (Fig. 1D). To determine whether the fluorescent protein position elicited these defects, we generated transgenic plants expressing mNeonGreen fused to the OLE1 N terminus (Fig. 1A). These pOLE1:mNeonGreen–OLE1 seedlings displayed normal lipid droplet morphology (Fig. 1D), timely TAG degradation (Fig. 1C), and reporter and endogenous OLE1 degradation resembling wild type (Fig. 1B). We concluded that mNeonGreen fused to the OLE1 C terminus interfered with OLE1 function, whereas mNeonGreen–OLE1 is a biologically neutral reporter of OLE1 localization and levels.

Fig. 1.

A biologically neutral OLE1 reporter. (A) Constructs to express mNeonGreen fused to the OLE1 C (Top) or N (Bottom) terminus flanked by OLE1 5′ and 3′ sequences. (B and C) Seedlings were processed for (B) immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies or (C) TLC of extracted lipids. Graphs indicate relative OLE1 signal relative to HSC70 (B) or TAG content (C) in three biological replicates (including the one shown) normalized to the WT signal at 0 d. Separate one-way ANOVA tests were performed to compare genotypes at each timepoint; letters represent homogenous subsets assigned by Tukey’s posthoc test when the P-value was <0.05. (D) Confocal images (single slices) of cotyledon epidermal cells. Neutral lipids were stained with MDH (magenta); mNeonGreen fluorescence is shown in green.

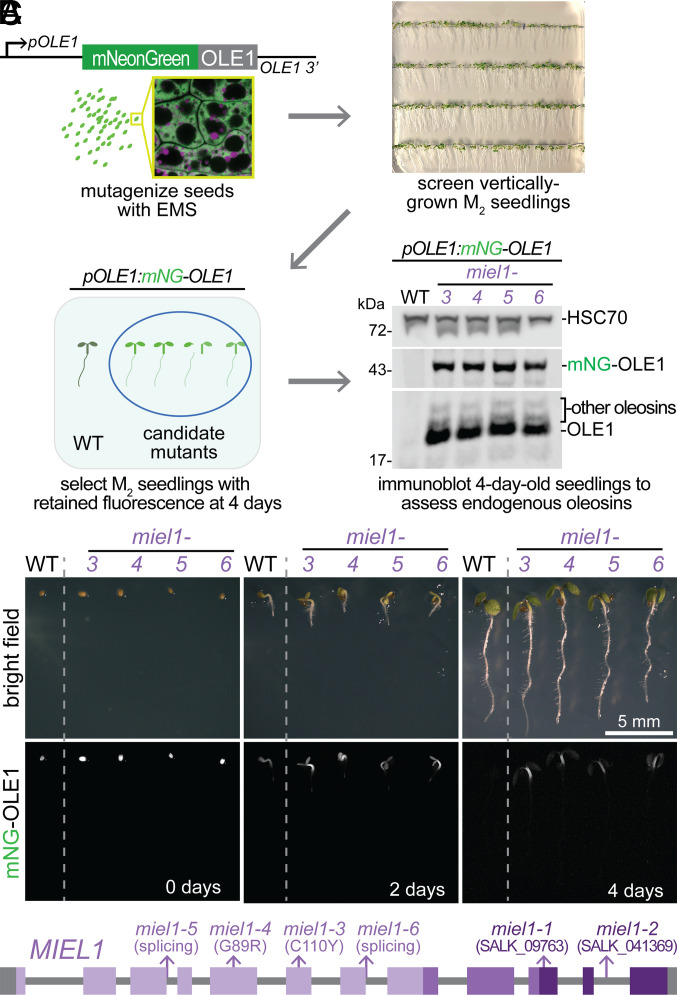

miel1 Mutants Were Isolated via a Screen for Persistent mNeonGreen–OLE1 Fluorescence.

To identify proteins involved in OLE1 degradation, we mutagenized pOLE1:mNeonGreen–OLE1 seeds with ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) and screened the progeny for seedlings with persistent mNeonGreen fluorescence (Fig. 2A). We tested progeny of candidate mutants for stabilized endogenous and tagged OLE1 protein via immunoblotting (Fig. 2A) and fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 2B). We used whole-genome sequencing to identify homozygous EMS-consistent (G-to-A or C-to-T) mutations. By identifying genes with different nonsynonymous mutations in mutants isolated from different mutagenic pools, we identified four unique mutations in MIEL1 (At5g18650) (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Isolation of miel1 mutants in a screen for persistent mNeonGreen–OLE1 fluorescence. (A) pOLE1:mNeonGreen–OLE1 seeds were mutagenized and their progeny was screened for sustained seedling fluorescence following germination. The Lower Right panel shows an immunoblot of 4-d-old unmutagenized pOLE1:mNeonGreen–OLE1 (WT) seedlings and miel1 mutant seedlings. (B) Representative bright field (Top) and mNeonGreen–OLE1 fluorescence (Bottom, grayscale) images of WT and miel1 mutants during germination and seedling development. (C) Gene diagram of MIEL1 showing newly identified (miel1-3 to miel1-6) and previously described (miel1-1 and miel1-2) mutations. Exons (boxes) are connected by introns (lines). Shades of purple denote MIEL1 structural domains depicted in Fig. 3.

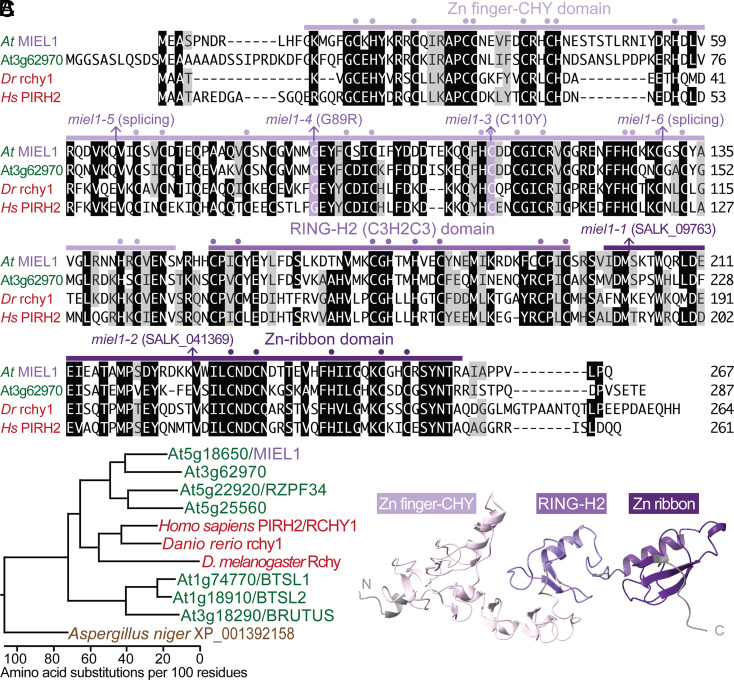

MIEL1 Is a RING Family Ubiquitin-Protein Ligase.

MIEL1 (MYB30-Interacting E3 Ligase 1) is a 267-amino acid ubiquitin-protein ligase acting in the substrate-recognition step of ubiquitination. It is an unusually cysteine-rich protein, with 28 conserved Cys and nine conserved His residues spread over three domains—an N-terminal Zn-finger domain of the CHY class, a central RING-H2 domain typical of ubiquitin-protein ligases, and a C-terminal Zn-ribbon domain (Fig. 3 A and C and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). MIEL1 has homologs in multiple eukaryotes and is 61% identical to its closest Arabidopsis relative (At3g62970) and 43% identical to the closest vertebrate proteins (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B).

Fig. 3.

MIEL1 is a conserved Cys-rich ubiquitin-protein ligase. (A) Alignment of MIEL1 and related proteins generated using the MegAlign (DNAStar) Clustal W method (BLOSUM series protein weight matrix). Identical residues are highlighted in black; chemically similar residues are highlighted in gray. miel1 mutations, conserved Cys and His residues, and MIEL1 domains are indicated above the sequences. (B) Phylogenetic tree including additional MIEL1 relatives constructed using the MegAlign program from the alignment shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S1. (C) Arabidopsis MIEL1 structure predicted by AlphaFold (41, 42) depicting the Zn finger-CHY (light purple), RING-H2 (medium purple), and Zn ribbon (dark purple) domains.

Our miel1 mutants included two missense alleles in the N-terminal Zn finger-CHY domain: miel1-3 changed a conserved Cys at position 110 to Tyr, and miel1-4 altered a conserved Gly at position 89 to Arg (Figs. 2C and 3A). In addition, we recovered two G-to-A mutations expected to disrupt splicing: miel1-5 changed the first nucleotide of intron 3 and miel1-6 changed the first nucleotide of intron 7 (Figs. 2C and 3A). To determine the molecular consequences of the intronic mutations, we reverse-transcribed miel1-5 and miel1-6 seedling RNA and sequenced PCR amplicons spanning the mutations. The predominant miel1-5 transcript was spliced 21 nucleotides upstream of the normal splice site in exon 3 and would encode a protein missing 7 amino acids of the CHY domain. miel1-6 produced a mixture of transcripts, some with unspliced intron 7 and others spliced 5 nucleotides upstream of the normal splice site in exon 7; both would prematurely terminate the protein in the CHY domain. We did not note differences in phenotypic severity in our four alleles (e.g., Fig. 2 A and B), suggesting that all four mutations similarly impede MIEL1 function. Moreover, we found that miel1-2, a previously described T-DNA insertional allele (Fig. 3A) (43, 44), also retained OLE1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), confirming that the miel1 mutations identified in our screen caused the oleosin stabilization phenotype.

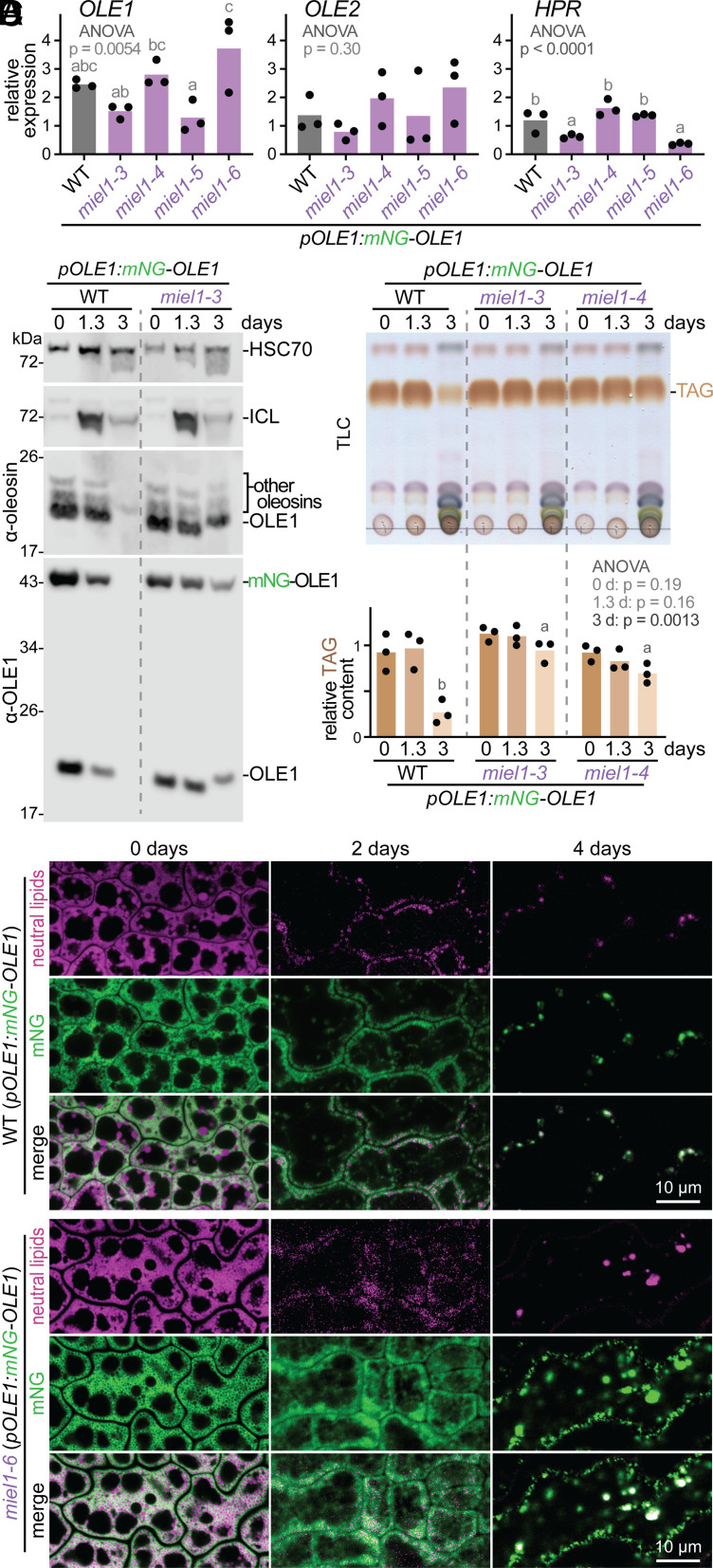

miel1 Mutants Delay Lipid Droplet Mobilization Without Elevating Oleosin Transcript Levels.

MIEL1 is reported to ubiquitinate two Arabidopsis transcription factors, MYB30 and MYB96 (44, 45), but had not been implicated in lipid mobilization. Because the identified MIEL1 targets are transcription factors, we hypothesized that MIEL1 might trigger degradation of a protein that promoted OLE transcription. To test this idea, we quantified transcripts from 2-d-old seedlings. We found that OLE1 and OLE2 mRNA levels resembled wild-type levels in our four miel1 mutants (Fig. 4A), suggesting that MIEL1 did not negatively regulate oleosin transcription. HPR encodes the photorespiratory enzyme hydroxypyruvate reductase, which accumulates as photosynthesis initiates (46). HPR mRNA levels resembled wild type in miel1 mutants (Fig. 4A), suggesting that oleosin persistence in the mutants was not due to delayed development. We concluded that MIEL1 impacts oleosin protein levels posttranscriptionally.

Fig. 4.

miel1 mutants retain oleosins, TAG, and lipid droplets longer than wild-type seedlings but do not display elevated oleosin transcript levels. (A) Relative OLE1,OLE2, and HPR transcript levels in 2-d-old seedlings measured via RT-qPCR. Letters above bars represent homogenous subsets assigned by Tukey’s posthoc test when one-way ANOVA P-values were <0.05. (B) Immunoblot probed with the indicated antibodies. Molecular weight marker positions (in kDa) are at the left. (C) TLC of extracted lipids. The graph shows relative TAG content in three biological replicates (including the one shown) normalized to the WT signal at 0 d and statistically analyzed as in the legend of Fig. 1. (D) Confocal images (single slices) of WT and miel1-6 cotyledon epidermal cells. Neutral lipids were stained with MDH (magenta); mNeonGreen–OLE1 fluorescence is shown in green. In panels B–D, 0-day samples were stratified seeds; other samples were seedlings harvested at the indicated times after sowing.

In wild-type seedlings, oleosins (Figs. 1B, 2A, and 4B and SI Appendix, Fig. S3) and TAG (Figs. 1C and 4C) were at least 75% degraded by 3 d after sowing. In contrast, miel1 mutants displayed delayed degradation of OLE1 (Figs. 2A and 4B and SI Appendix, Fig. S3) and other oleosins (Figs. 2A and 4B) as well as delayed TAG catabolism (Fig. 4C). Moreover, miel1 seed lipid droplets appeared somewhat smaller and persisted longer than wild-type lipid droplets following germination (Fig. 4D). To assess developmental progression, we monitored isocitrate lyase (ICL), a peroxisomal glyoxylate cycle enzyme that accumulates in young seedlings and is degraded as photosynthesis begins (46). ICL dynamics resembled wild type in miel1-3 (Fig. 4B), again indicating that a developmental delay was not slowing oleosin and TAG degradation in miel1 mutants.

The requirement for fatty acid β-oxidation during seedling development can be bypassed by providing an alternative fixed carbon source, such as sucrose (37, 47, 48). Because miel1 seedlings utilized TAG slowly (Fig. 4C), we compared miel1 seedling growth with and without supplemental sucrose. miel1 seedling hypocotyl elongation in the dark appeared to be slightly decreased compared to wild type when sucrose was not present in the medium (SI Appendix, Fig. S4), although miel1 was not as impaired as the peroxisome-defective mutant pex12-1 (49), and this defect did not achieve statistical significance in all biological replicates. In contrast, miel1 seedlings grew similarly to wild type on the auxin precursor indole-3-butyric acid (IBA; SI Appendix, Fig. S4), which inhibits elongation because it is β-oxidized to active auxin in peroxisomes (25). We concluded that MIEL1 promotes TAG utilization but is not required for general peroxisomal β-oxidation.

miel1 Mutants Have Altered Lipid Droplet and Peroxisome Morphology.

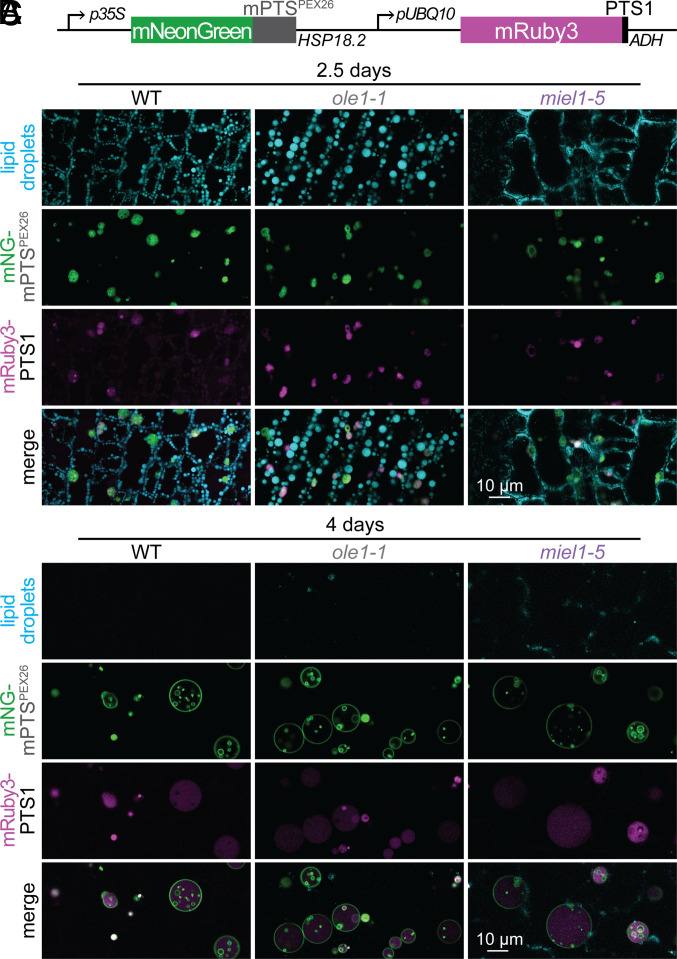

To investigate the MIEL1 impact on lipid droplet morphology in the absence of fluorescently tagged OLE1, we crossed an miel1 mutant to a reporter line marking peroxisome membranes with mNeonGreen and the peroxisome lumen with mRuby3 (Fig. 5A) (39). We isolated an miel1 mutant with labeled peroxisomes but lacking the oleosin reporter and visualized lipid droplets using a neutral lipid dye. Like in the presence of mNeonGreen–OLE1 (Fig. 4D), miel1 seedlings without an oleosin reporter displayed small, dispersed lipid droplets (Fig. 5B and SI Appendix, Fig. S5) that were retained longer than lipid droplets in wild-type or ole1-1 seedlings (Fig. 5C). In addition, 4-d-old miel1 seedlings displayed enlarged peroxisomes with possibly reduced prevalence of ILVs (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

MIEL1 loss appears to decrease lipid droplet size and impact peroxisome morphology. (A) Diagram of constitutively expressed fluorescent reporters marking peroxisomal membranes (mNeonGreen–mPTSPEX26) and lumen (mRuby3–PTS1) (39). (B and C) Confocal images (single slices) of MDH-stained neutral lipids (cyan), peroxisome membranes (green), and peroxisome lumen (magenta) in cotyledon epidermal cells of 2.5- (B) and 4- (C) d-old WT, ole1-1, and miel1-5 seedlings expressing the reporters diagramed in panel A.

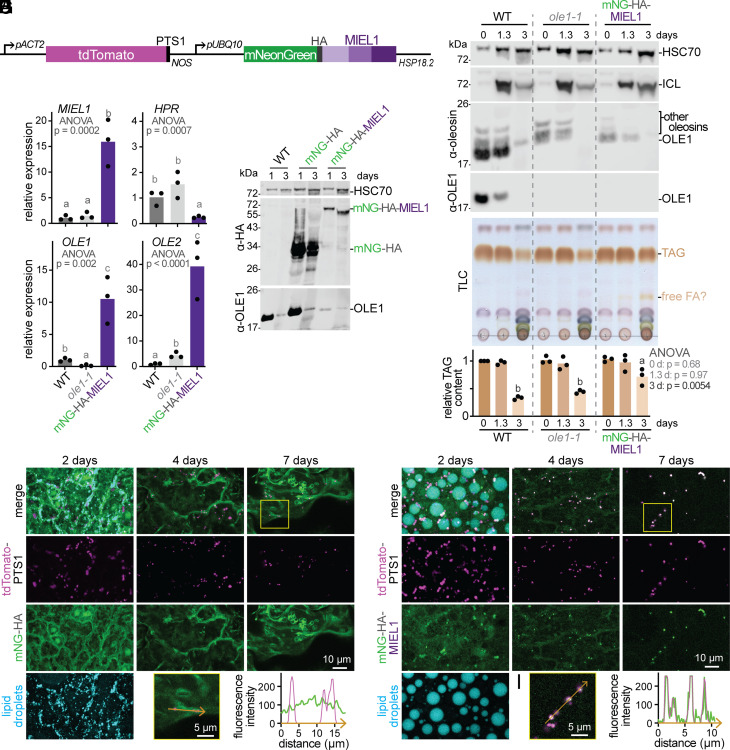

Overexpressed mNeonGreen–MIEL1 Increases Oleosin Degradation, Induces Lipid Droplet Expansion, and Localizes to Peroxisomes.

To evaluate MIEL1 localization and the impact of MIEL1 overexpression on lipid droplet dynamics, we generated constructs to constitutively express a peroxisomal lumen marker (tdTomato–PTS1) together with a fluorescent cytosolic reporter (mNeonGreen–HA) or fluorescently tagged MIEL1 (mNeonGreen–HA–MIEL1; Fig. 6A). MIEL1-overexpressing seedlings accumulated about 15-fold more MIEL1 mRNA than wild-type seedlings (Fig. 6B), and we detected mNeonGreen–HA–MIEL1 of the expected size on immunoblots (Fig. 6C), confirming that the intact fusion protein was produced. We found elevated OLE1 and OLE2 mRNA levels in MIEL1-overexpressing seedlings (Fig. 6B), which is inconsistent with the hypothesis that MIEL1 triggers degradation of a protein promoting OLE1 transcription. Despite substantially elevated OLE1 mRNA levels, immunoblotting revealed that seeds and seedlings expressing mNeonGreen–HA–MIEL1 contained markedly less OLE1 and other oleosins than those of wild type or control lines expressing mNeonGreen–HA (Fig. 6 C and D). Consistent with greatly reduced oleosin levels, MIEL1 overexpression was accompanied by remarkably large lipid droplets in 2-d-old seedlings (Fig. 6H). The opposite effects on oleosin abundance and lipid droplet size that accompany MIEL1 overexpression (Fig. 6) and loss of function (Fig. 4) indicate that MIEL1 is normally limiting for oleosin degradation.

Fig. 6.

Overexpressed mNeonGreen–MIEL1 decreases oleosin levels, slows TAG utilization, enlarges lipid droplets, and localizes to peroxisomes. (A) Diagram of constitutively expressed fluorescent reporters marking peroxisomal lumen (tdTomato–PTS1) and MIEL1 (mNeonGreen–HA–MIEL1). (B) Relative mRNA levels in 2-d-old seedlings were measured via RT-qPCR and statistically analyzed as in the legend of Fig. 4. (C) Immunoblot of seedlings without a reporter (WT), segregating for mNeonGreen–HA, or homozygous for mNeonGreen–HA–MIEL1 probed with the indicated antibodies. (D) Immunoblot probed with the indicated antibodies. (E) TLC of extracted lipids. The graph shows relative TAG content in three biological replicates (including the one shown) normalized to the WT signal at 0 d and statistically analyzed as in the legend of Fig. 1. (F) Confocal images (maximum-intensity projections of twelve 1-µm slices) of hypocotyl epidermal cells showing tdTomato–PTS1 (magenta) and mNeonGreen–HA (green) at the indicated seedling ages. Neutral lipids were stained with MDH (cyan) in 2-d-old seedlings. (G) Magnification of boxed region in 7-d image from panel F. Plot shows tdTomato–PTS1 (magenta) and mNeonGreen–HA (green) fluorescence intensity across multiple peroxisomes (orange arrow). (H) As in panel F, but with mNeonGreen–HA–MIEL1. (I) Magnification of boxed region in 7-d image from panel H. Plot shows tdTomato–PTS1 (magenta) and mNeonGreen–HA–MIEL1 (green) fluorescence intensity across multiple peroxisomes (orange arrow). In panels C–E, 0-d samples were stratified seeds; other samples were seedlings harvested at the indicated times following sowing.

Even though seedlings overexpressing MIEL1 retained less oleosin than wild-type seedlings (Fig. 6 C and D), TAG mobilization was delayed (Fig. 6E), demonstrating that TAG mobilization delays can accompany both increased (Fig. 4 B and C) and decreased (Fig. 6 C–E) oleosin levels.

The mNeonGreen–HA–MIEL1 construct also allowed us to visualize MIEL1 subcellular localization. Unlike mNeonGreen–HA, which was cytosolic (Fig. 6 F and G), mNeonGreen–HA–MIEL1 localized not only to the cytosol, but also to peroxisomes (Fig. 6 H and I). This peroxisomal localization hints that MIEL1 might promote oleosin degradation specifically at peroxisome–lipid droplet contact sites.

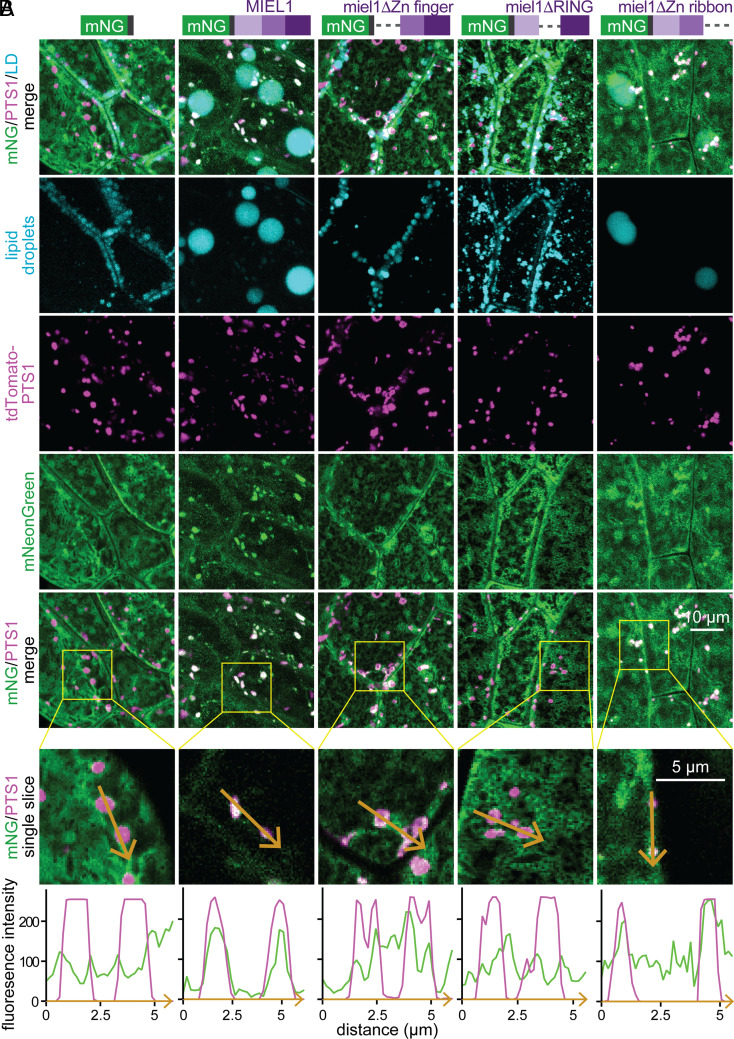

The MIEL1 N-Terminal Zn Ribbon and RING Domains Direct Peroxisomal Localization and Lipid Droplet Enlargement.

To determine which MIEL1 domains were needed for peroxisomal localization and lipid droplet expansion, we transformed wild-type plants with constructs expressing modified mNeonGreen–HA–MIEL1 lacking either the N-terminal Zn-finger domain, the central RING domain, or the C-terminal Zn-ribbon domain. These derivatives accumulated to similar levels as the parent mNeonGreen–HA–MIEL1 protein in seedlings (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). We found that the C-terminal Zn-ribbon deletion protein (miel1ΔZn ribbon), like intact MIEL1, localized to peroxisomes, induced large lipid droplets (Fig. 7), and lowered oleosin levels (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). This finding indicates that the Zn-ribbon domain is not required for MIEL1 localization to peroxisomes, substrate binding, or catalytic activity related to lipid droplets. In contrast, the central RING deletion protein (miel1ΔRING) did not localize to peroxisomes, induce large lipid droplets (Fig. 7), or reduce OLE1 levels (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A), suggesting that OLE1 ubiquitination and degradation are required for MIEL1-driven lipid droplet enlargement. The N-terminal Zn-finger deletion protein (miel1ΔZn finger) was partially peroxisome associated (Fig. 7) and displayed intermediate OLE1 levels (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A) but did not induce large lipid droplets (Fig. 7). These data indicate that peroxisomal localization via the RING domain is necessary but not sufficient for MIEL1-mediated induction of large lipid droplets.

Fig. 7.

The MIEL1 N-terminal and RING domains direct peroxisome localization and lipid droplet enlargement. (A) Lipid droplets (stained with MDH; cyan); peroxisomes (tdTomato–PTS1; magenta); and either mNeonGreen–HA, mNeonGreen–HA–MIEL1, or mNeonGreen–HA–MIEL1 domain deletion derivatives (green) were visualized in hypocotyl epidermal cells of 2-d-old seedlings. Maximum-intensity projections of ten 1-µm slices are shown. (B) Magnification of single slices from the boxed regions in panel A. Plots show tdTomato–PTS1 (magenta) and mNeonGreen (green) fluorescence intensity across multiple peroxisomes (orange arrows).

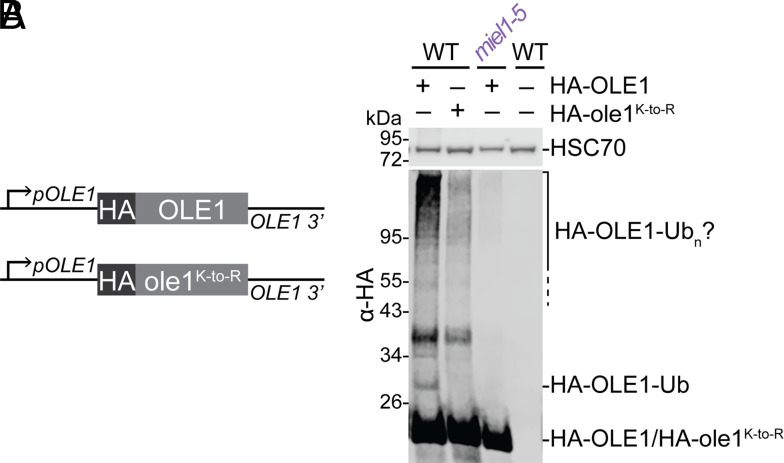

MIEL1 Is Necessary for OLE1 Ubiquitination.

The reciprocal impacts of MIEL1 mutation or overexpression on oleosin protein but not mRNA levels (Figs. 4 and 6) suggested that MIEL1 might directly target oleosins for degradation via ubiquitination. To detect in vivo OLE1 ubiquitination, we generated lines transformed with pOLE1:HA–OLE1 or pOLE1:HA–ole1K-to-R, which has all seven OLE1 Lys residues replaced with nonubiquitinatable Arg residues (Fig. 8A). In addition to HA–OLE1, we detected an HA-positive protein the size of ubiquitinated HA–OLE1 (~28 kDa) in wild-type seedlings expressing HA–OLE1 but not in seedlings expressing HA–ole1K-to-R (Fig. 8B). This finding indicates that the ubiquitin-sized posttranslational modification detected on HA–OLE1 depended on a Lys residue. We crossed the pOLE1:HA–OLE1 transgene into miel1-5 and found that this modified HA–OLE1, as well as higher molecular mass bands that may represent polyubiquitinated HA–OLE1, was not detected in miel1 mutant seedlings (Fig. 8B), suggesting that MIEL1 directly ubiquitinates oleosin.

Fig. 8.

MIEL1 is necessary for OLE1 ubiquitination. (A) Constructs to express HA-tagged OLE1 or ole1K-toR (with Lys residues altered to Arg) flanked by OLE1 5′ and 3′ sequences. (B) Immunoblot of proteins from 1-d-old WT seedlings expressing HA–OLE1 or HA–ole1K-toR, miel1-5 expressing HA–OLE1, or untransformed WT.

The MIEL1 Homolog HsPIRH2 Can Localize to Arabidopsis Peroxisomes.

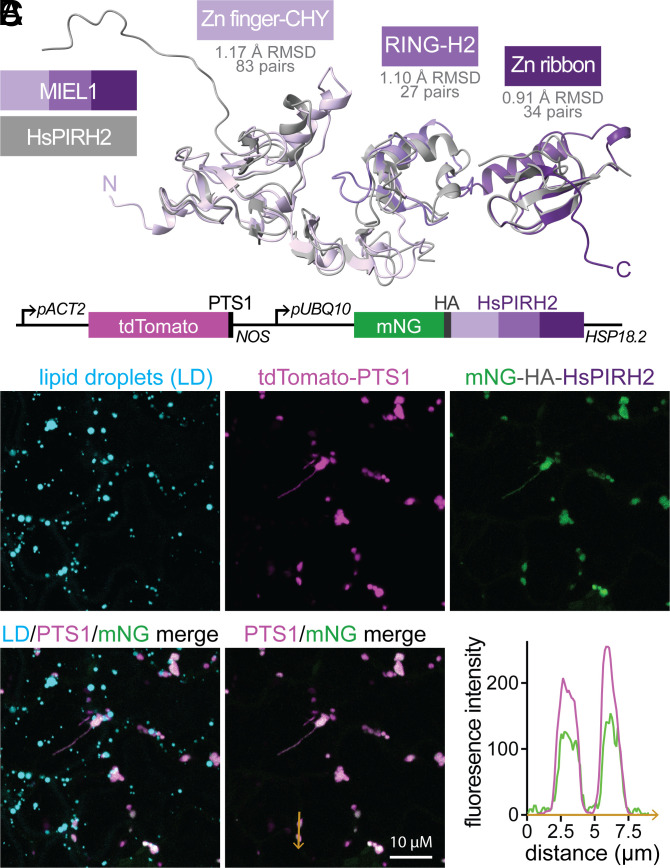

Human (Hs) PIRH2 (p53-induced protein with a RING-H2 domain) is 43% identical to Arabidopsis MIEL1 (Fig. 3 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). We identified HsPIRH2 as a MIEL1 structural homolog (50) with 99.9% confidence; the NMR structures of each PIRH2 domain (51) aligned closely (0.9 to 1.2 Å rmsd) to the Arabidopsis MIEL1 structure predicted by AlphaFold (41, 42) (Fig. 9A). Human PIRH2 can localize to the nucleus and ubiquitinate p53 (52) and c-Myc (53), but has not been implicated in lipid droplet dynamics or activity outside of the nucleus.

Fig. 9.

The human MIEL1 homolog HsPIRH2 localizes to peroxisomes when expressed in Arabidopsis. (A) HsPIRH2 NMR structures (gray) (PDB 2K2C, 2JRJ, and 2K2D) (51) were aligned to the MIEL1 structure (purple) predicted by AlphaFold (41, 42). (B) Diagram of constitutively expressed fluorescent reporters marking peroxisomal lumen (tdTomato–PTS1) and human PIRH2 (mNeonGreen–HA–HsPIRH2). (C) Cotyledon epidermal cells of 4-d-old seedlings transformed with the construct shown in panel B were imaged using confocal microscopy. Maximum-intensity projections (ten 1-µm slices) of neutral lipids stained with MDH (cyan), tdTomato–PTS1 (magenta), and mNeonGreen–HA–HsPIRH2 (green) are shown. The plot shows tdTomato–PTS1 (magenta) and mNeonGreen (green) fluorescence intensity across two peroxisomes (orange arrow).

To test whether HsPIRH2 might function similarly to MIEL1, we generated transgenic Arabidopsis plants constitutively expressing fluorescently tagged HsPIRH2 together with a peroxisomal lumen marker (Fig. 9B). Strikingly, mNeonGreen–HA–HsPIRH2 localized to Arabidopsis peroxisomes (Fig. 9C). In contrast to when MIEL1 was overexpressed (Fig. 6), lipid droplets were not enlarged (Fig. 9C) and OLE1 levels were not diminished (SI Appendix, Fig. S6B) upon HsPIRH2 expression. This difference suggests that oleosins are not targeted by PIRH2 and indicates that the lipid droplet enlargement observed upon mNeonGreen–HA–MIEL1 overexpression did not result from targeting mNeonGreen to peroxisomes.

Discussion

Lipid droplets and peroxisomes are dynamic subcellular compartments that collaborate to control carbon flux in eukaryotes (22). To identify genes modulating lipid droplet and oleosin dynamics during peroxisomal lipid catabolism, we sought to visualize lipid droplets and OLE1 in a near-endogenous context. Fluorescent proteins appended to the oleosin C terminus (54–56) include the widely used FAST (fluorescence-accumulating seed technology) system, which allows visual selection of transformed seeds marked with OLE1-GFP or OLE1-RFP (57). However, expressing OLE1–GFP from the 35S promoter leads to lipid droplet aggregation and delays TAG mobilization (54, 55). Moreover, these OLE1–GFP lipid droplet aggregates are subject to autophagy during extended darkness (58). We also found aberrant lipid droplet clustering and delayed lipid droplet and TAG mobilization when expressing OLE1–mNeonGreen (Fig. 1), even though we used the OLE1 promoter and a monomeric fluorescent protein (59). Perhaps, a C-terminal appendage disrupts the ability of the OLE1 C-terminal α-helix to correctly nestle within the phospholipid monolayer, exposing the hydrophobic face of this amphipathic helix and inducing aggregation of OLE1–mNeonGreen and consequently lipid droplets. Moreover, Lys residues in this C-terminal helix are ubiquitinated before OLE1 extraction and degradation during germination (19–21); a C-terminal fusion might impede access to the ubiquitination or extraction machinery. To avoid these potential problems, we fused mNeonGreen to the OLE1 N terminus. mNeonGreen–OLE1 was degraded in parallel with endogenous OLE1 (Fig. 1B) and did not induce lipid droplet clustering (Fig. 1D), slow endogenous oleosin degradation (Fig. 1B), or impede TAG catabolism (Fig. 1C). Thus, the lipid droplet clustering we observed with OLE1–mNeonGreen was not due to aggregation of the fluorescent protein itself. We expect that N-terminal fusions to OLE1 might similarly reduce artifacts observed with other fluorescent proteins and promoters.

Despite the nonnative behavior of OLE1–GFP fusions, mutant screens based on such reporters have illuminated native lipid droplet dynamics. For example, a screen for mutants with enlarged OLE1–GFP aggregates yielded sdp1 alleles (38), emphasizing the importance of TAG hydrolysis for timely oleosin degradation. Exploiting the observation that p35S:OLE1–GFP plants produce ectopic lipid droplets in mature leaves (55), a screen for reduced ectopic lipid droplets revealed a role for sterol biosynthetic enzymes in lipid droplet biogenesis (60).

Using a forward-genetic screen for persistent mNeonGreen–OLE1, we identified four miel1 mutations that slowed degradation of the reporter, endogenous OLE1, and other oleosins (Figs. 2 and 4B). Thus, even though various seed oleosins are degraded with slightly different kinetics in wild-type seedlings (19), the stabilization mechanism we uncovered was not OLE1 specific or reporter dependent.

MIEL1 is a ubiquitin-protein ligase known to ubiquitinate two transcription factors, MYB30 and MYB96 (44, 45). Arabidopsis MYB30 positively regulates hypersensitive cell death (61). In noninfected plants, MIEL1 ubiquitinates MYB30, triggering proteasomal degradation and preventing cell death in healthy tissue (45). MIEL1 also regulates abscisic acid (ABA) sensitivity by promoting MYB96 turnover (44). Because MIEL1 is nuclear-localized in protoplast bimolecular fluorescence complementation assays (45), and because both identified MIEL1 substrates are transcription factors, we initially hypothesized that MIEL1 might trigger degradation of a transcription factor that promotes OLE1 transcription. If MIEL1 negatively regulated OLE1 transcription, we expected miel1 mutants to have high OLE1 transcript levels and MIEL1 overexpressors to have low OLE1 transcript levels. However, miel1 mutant seedlings displayed wild-type OLE1 and OLE2 transcript levels (Fig. 4A), and overexpressing MIEL1 increased OLE1 and OLE2 transcript levels (Fig. 6B). Moreover, we found mNeonGreen-HA–MIEL1 primarily in the cytosol and peroxisome-associated rather than in nuclei of young seedlings (Fig. 6H). Together, these data suggest that MIEL1 regulates OLE1 posttranscriptionally.

The increased OLE1 and OLE2 mRNA levels (Fig. 6B) in MIEL1-overexpressing seedlings with reduced oleosin protein levels (Fig. 6D) suggest a feedback mechanism to increase OLE transcription (or slow transcript degradation) when oleosin protein levels are low. Indeed, we also noted slightly elevated OLE2 transcripts in the ole1-1 mutant (Fig. 6B), which lacks OLE1 protein.

Mammalian perilipins protect lipids from hydrolysis (7). Seed oleosins prevent lipid droplet coalescence (9, 10), contribute to oilseed freeze tolerance (62), and may function analogously to perilipins by physically occluding lipase access to TAG. Alternatively, or in addition, the oleosin extraction process could uproot TAG buried in the lipid droplet core to promote lipase access. Moreover, oleosins could influence lipid mobilization by docking peroxisomes or peroxisomal lipases (e.g., SDP1) or optimizing lipid droplet curvature or surface-to-volume ratio. miel1 mutants retained oleosins (Fig. 4B) and TAG (Fig. 4C) longer than wild type and appeared slightly sucrose dependent (SI Appendix, Fig. S4), suggesting that oleosin restricts lipase access to TAG.

MIEL1-overexpressing seedlings displayed low oleosin levels (Fig. 6D) but also retained TAG (Fig. 6E). Similarly, ole1 mutants display enlarged lipid droplets (Fig. 5B) and are reported to slow lipid mobilization (9), although to a lesser extent (Fig. 6E). The smaller surface-to-volume ratios of large lipid droplets in MIEL1-overexpressing lines may delay TAG hydrolysis. In addition to TAG, MIEL1-overexpressing seedlings appeared to accumulate a lipid species that comigrated with free fatty acid in thin-layer chromatography (Fig. 6E). Drosophila Pex19 mutants lack peroxisomes and up-regulate lipases, resulting in free fatty acid accumulation and lipotoxicity (63), highlighting the importance of sequestering TAG from lipases when fatty acids cannot be promptly imported into peroxisomes. Perhaps, the large lipid droplets in MIEL1-overexpressing seedlings do not appropriately control lipid release, allowing fatty acids to enter the cytosol and cause lipotoxicity. Our data suggest that, like perilipins, oleosins keep lipids sequestered in lipid droplets to prevent cytotoxicity.

We were surprised to find mNeonGreen–HA–MIEL1 localized to peroxisomes (Figs. 6 H and I and 7). MIEL1 lacks a canonical peroxisome-targeting signal that would direct it to the peroxisome lumen and lacks a predicted transmembrane domain to anchor it in a membrane, suggesting that MIEL1 might localize to the peroxisomal surface through an interaction partner. The MIEL1 RING domain was necessary for MIEL1 peroxisomal localization (Fig. 7), and RING domains typically interact with ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (UBCs) (64). PEX4 is a peroxisome-tethered UBC (30–32) that supplies ubiquitin to a RING peroxin triad that ubiquitinates PEX5 to facilitate lumenal protein delivery (26). Future experiments may reveal which proteins interact with MIEL1 to mediate its peroxisomal localization.

Because MIEL1-dependent lipid droplet expansion required N-terminal Zn-finger domain but not the C-terminal Zn-ribbon domain (Fig. 7), it is tempting to speculate that MIEL1 binds substrates important for this activity through its N-terminal Zn-finger domain. It will be interesting to learn whether our missense alleles in this domain (Fig. 3A) decrease MIEL1-substrate binding.

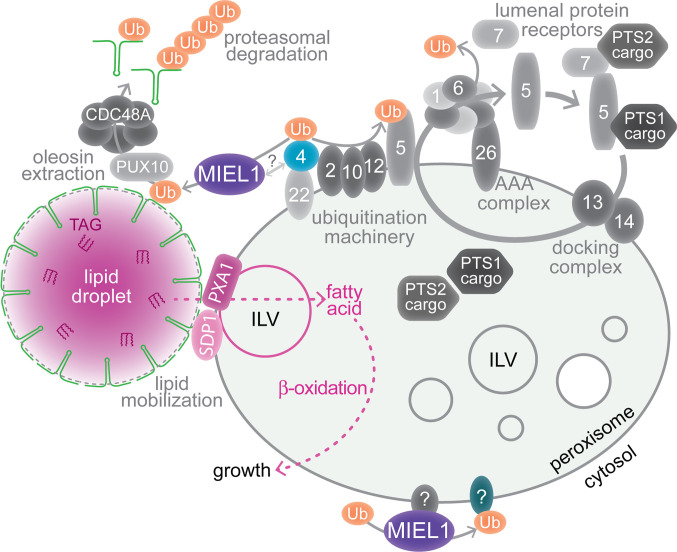

The inverse relationship between MIEL1 activity and oleosin levels/lipid droplet size (Figs. 4–7), the lack of ubiquitinated HA–OLE1 in a miel1 mutant (Fig. 8), and the peroxisomal localization of mNeonGreen–HA–MIEL1 (Fig. 6 H and I) suggest that MIEL1 ubiquitinates OLE1 and other seed oleosins during germination (Fig. 10). Oleosin ubiquitination via MIEL1 would precede extraction for proteasomal degradation by lipid droplet–associated PUX10 and CDC48A (20, 21). MIEL1 is not the only protein localizing to peroxisomes and acting on lipid droplets. The SDP1 lipase, which catalyzes the first step of lipid droplet TAG catabolism (34), also localizes to peroxisomal membranes (35, 65). Perhaps, localizing key enzymes, including SDP1 and MIEL1, to the peroxisome surface constrains TAG mobilization to sites where a peroxisome is positioned to take in and catabolize fatty acids as they are released from a lipid droplet (Fig. 10), thus avoiding the cytotoxicity that would ensue upon free fatty acid release in the cytosol. Indeed, PUX10 and CDC48A localize to a subset of lipid droplets in germinating seedlings (20), and it will be interesting to learn whether these are peroxisome associated.

Fig. 10.

Working model for MIEL1 functions at peroxisomes. MIEL1 is necessary for oleosin (green hairpins) ubiquitination and timely degradation during lipid mobilization. Oleosin ubiquitination allows extraction by PUX10 and CDC48A (20, 21) and proteasomal degradation. MIEL1 localizes at peroxisomes, perhaps via interaction with an organelle surface protein, such as the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme PEX4. PEX4 (blue) and other peroxins (numbered shapes) function in the import of lumenal cargo proteins with PTS1 or PTS2 signals via the PEX7 and PEX7 cycling receptors. MIEL1 may also target proteins on the peroxisome that modulate peroxisome dynamics, such as the formation of ILVs, which are implicated in fatty acid β-oxidation and protein sorting (39). SDP1 is a peroxisome-associated TAG lipase (34, 35), and PXA1 transports fatty acids into the organelle for β-oxidation (36, 37).

Beyond controlling lipid droplet dynamics, MIEL1 may play additional roles at peroxisomes (Fig. 10). Although multiple Arabidopsis peroxisomal proteins are ubiquitinated (66), only a few peroxisome-associated ubiquitin-protein ligases are known (67). miel1 seedlings appeared to have enlarged peroxisomes with few intralumenal vesicles (Fig. 5C). This phenotype resembles β-oxidation mutants (39) and hints at MIEL1 roles in peroxisome dynamics. Further experiments are needed to determine whether altered peroxisome morphology in miel1 seedlings stems from altered lipid mobilization or reflects dysregulation of peroxisomal MIEL1 substrates.

MIEL1 is a RING-H2 ubiquitin-protein ligase. The RING domain family is expanded in plants, with 508 RING proteins in Arabidopsis compared to 45 in humans and 14 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (68). RING domains are categorized by the spacing of Cys and His residues that coordinate two zinc ions to form a protein-interaction domain. The RING-H2 class is common (69), with 258 members in Arabidopsis, 17 in humans (including PIRH2), and six in S. cerevisiae (68). MIEL1 combines the central RING-H2 motif with an N-terminal Zn-finger-CHY motif and a C-terminal Zn-ribbon motif. This domain organization shared with six additional RING-H2 proteins in Arabidopsis (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), including three similarly sized proteins (287 to 308 amino acids) and three much larger proteins (1,254 to 1,259 amino acids) that regulate iron responses by targeting specific transcription factors for degradation (70–75). Among the three closer Arabidopsis MIEL1 homologs, which consist almost entirely of the three Cys/His-rich domains (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), one protein in addition to MIEL1 has been characterized. CHY ZINC-FINGER AND RING PROTEIN 1 (CHYR1)/RZP34 (At5g22920) modulates ABA and drought responses (76) by ubiquitinating phosphorylated WRKY70, a transcription factor involved in pathogen response (77). It will be interesting to learn the localizations and roles of the uninvestigated Arabidopsis MIEL1 homologs.

In contrast to the expansion and diversity of the MIEL1 family in Arabidopsis, humans, zebrafish, and Drosophila each encode a single MIEL1 homolog that is similar in size to MIEL1 (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Human PIRH2 regulates p53 and other transcription factors in the nucleus and is implicated in diseases including cancer (40, 52). Because human PIRH2 displayed high sequence (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1) and structural (Fig. 9A) similarity to MIEL1, we tested for functional conservation. HsPIRH2 localized predominantly to peroxisomes when expressed in Arabidopsis seedlings (Fig. 9C). Unlike MIEL1, however, PIRH2 did not induce large lipid droplets (Fig. 9C), perhaps because human lipid droplet coat proteins (e.g., perilipins) are structurally distinct from oleosins. These data hint at a role for PIRH2 in mammalian peroxisomes and imply that the conserved mechanism of MIEL1 and PIRH2 localization to peroxisomes is independent of oleosin. In the Human Protein Atlas subcellular localization data (78), PIRH2 is annotated as localizing to the nucleus, cytosol, and vesicles (proteinatlas.org/PIRH2). Although some known peroxisomal proteins are annotated as localizing to peroxisomes (e.g., PEX14; proteinatlas.org/PEX14), peroxisomes are often overlooked in subcellular localization studies, and other canonical peroxisomal proteins are annotated as localizing to vesicles (e.g., PEX2; proteinatlas.org/PEX2). It will be interesting to learn if the PIRH2-positive vesicles in human cells are peroxisomes and if PIRH2 modulates lipid droplet or peroxisome function in animals.

Lipid droplets are dynamic organelles involved in energy homoeostasis, membrane remodeling, and signaling (1–3). Excessive lipid droplet accumulation is a hallmark of debilitating metabolic diseases in humans (79, 80), and plant lipid droplets are critical in agriculture and have myriad industrial uses (1, 3). The molecular and functional links between Arabidopsis lipid droplets, peroxisomes, and MIEL1/PIRH2 described here may provide insights applicable across eukaryotes.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Mutant Screening.

Transgenic and mutant lines were in the Col-0 accession of A. thaliana. Untransformed Col-0 and a homozygous, single insertion pOLE1:mNeonGreen–OLE1 line were used as wild-type (WT) controls. miel1-2 (Salk_041369C) and ole1-1 (SM_3_29864) were from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center and the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre, respectively. pex12-1 was previously described (49). Newly identified miel1 mutants (miel1-3–miel1-6) were backcrossed prior to phenotypic analysis, except for Fig. 4D, which was conducted on progeny of original isolates. Plants expressing mNeonGreen–mPTSPEX26 and mRuby3–PTS1 (39) or HA–OLE1 were crossed to ole1-1 and/or miel1-5 to generate the corresponding reporter-expressing mutants. Genotypes were determined via PCR (SI Appendix, Table S1). Plant growth conditions are in SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods.

Inserts for plant transformation plasmids were either synthesized by GenScript (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 A, B, J, and K) or constructed in a pUC57-based entry vector via Gibson assembly (81) following cDNA amplification with Q5 high-fidelity DNA polymerase (NEB) using the primers listed in SI Appendix, Table S2. Assembled inserts were recombined into pMCS:GW destination vector (82) using LR Clonase II (Invitrogen) to generate plant transformation vectors (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 C–I), which were verified by sequencing via assembled Oxford Nanopore reads by Plasmidsaurus (Eugene, OR). Detailed DNA and plant transformation methods are in SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods.

pOLE1:mNeonGreen–OLE1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S7B) seeds were mutagenized with EMS (83) and progeny were screened for persistent mNeonGreen fluorescence using a fluorescence stereomicroscope. Whole-genome sequencing data from pooled M4 seedlings were processed with the Gene Variant Identifier (https://github.com/cp-bioinfo/gene-variant-identifier) (84) software to identify EMS-consistent (G-to-A) mutations, eliminate background mutations, identify shared mutations across mutants from the same pool, and identify allelic mutations across mutants from different pools (85). Detailed methods are in SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods.

Immunoblotting and Lipid Analysis.

Seed and seedling protein extracts were processed for immunoblotting as previously described (31). Detailed immunoblotting methods are in SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods.

Lipids were extracted from stratified seeds and light-grown seedlings grown in liquid medium via Folch extraction and visualized as previously described (60). Samples were normalized by seed or seedling number across genotypes and ages, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and ground in 1.7-mL tubes. Lipids were extracted with chloroform/methanol/formic acid (1:2:0.1, by volume), concentrated with 0.5 volumes of phase separation solution (1 M KCl, 0.2 M H3PO4), and separated on TLC plates (Silica Gel 60, EMD Millipore Corporation) using hexane/diethyl ether/acetic acid (70:30:1, by volume). Lipids were visualized by submerging TLC plates in 5% H2SO4, drying, and heating to develop color.

Confocal Microscopy.

Seeds and light-grown seedlings were imaged by live-cell fluorescence confocal microscopy using an Olympus FV3000RS inverted laser scanning confocal microscope. Detailed microscopy methods are in SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods.

mRNA Quantification.

Total RNA was extracted from 2-d-old seedlings grown in liquid medium using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen; 74904). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 2 µg RNA using the Superscript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Fisher Scientific; 18080-051) with oligo(dT)20 primers. RT-qPCR was performed using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad; 1725120) and the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Target cDNA was amplified with gene-specific primers where one primer spanned an exon–exon junction (SI Appendix, Table S3). Relative expression was compared to the ACT1 control of each sample to account for pipetting and biological variances.

Quantification, Statistical Analyses, and Data Visualization.

Statistical analyses were performed across biological replicates using one-way ANOVA. When P-values were <0.05, Tukey’s posthoc test was used to compare means, and homogenous subsets were assigned. Detailed information on quantification, data normalization, and visualization is in SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Roxanna Llinas and Christopher Phillips for help processing sequencing data, Jae Kim for assistance with a pilot mutant screen, Carol de Groote Tavares for help assessing candidate mutant phenotypes, Zachary Wright and Kathryn Smith for the tdTomato–PTS1 mNeonGreen–mPTSPEX26 plasmid, Anthony Huang for the oleosin antibody, Masayoshi Maeshima for the ICL antibody, and Aryeh Warmflash for RT-qPCR equipment use. We are grateful to Gabrielle Buck, Isabella Kreko, Roxanna Llinas, DurreShahwar Muhammad, Kathryn Smith, Ana Swearingen, Nathan Tharp, and Zachary Wright for critical feedback on the manuscript. This research was supported by the NIH (R35GM130338) and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (C-1309). Whole-genome sequencing was performed by The Genome Technology Access Center at Washington University School of Medicine, which is partially supported by an NIH National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA91842) and the NIH National Center for Research Resources ICTS/CTSA (UL1TR002345). Protein structural graphics and analyses were performed with UCSF ChimeraX, developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, with support from NIH R01GM129325 and the Office of Cyber Infrastructure and Computational Biology, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Author contributions

M.S.T. and B.B. designed research; M.S.T. performed research; M.S.T. and B.B. analyzed data; and M.S.T. and B.B. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

Reviewers: K.C., University of North Texas; and C.X., Brookhaven National Laboratory.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Huang A. H. C., Plant lipid droplets and their associated proteins: Potential for rapid advances. Plant Physiol. 176, 1894–1918 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lundquist P. K., Shivaiah K.-K., Espinoza-Corral R., Lipid droplets throughout the evolutionary tree. Prog. Lipid Res. 78, 101029 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guzha A., Whitehead P., Ischebeck T., Chapman K. D., Lipid droplets: packing hydrophobic molecules within the aqueous cytoplasm. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 74, 195–223 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Listenberger L. L., et al. , Triglyceride accumulation protects against fatty acid-induced lipotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 3077–3082 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ischebeck T., Krawczyk H. E., Mullen R. T., Dyer J. M., Chapman K. D., Lipid droplets in plants and algae: Distribution, formation, turnover and function. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 108, 82–93 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLachlan D. H., et al. , The breakdown of stored triacylglycerols is required during light-induced stomatal opening. Curr. Biol. 26, 707–712 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sztalryd C., Brasaemle D. L., The perilipin family of lipid droplet proteins: Gatekeepers of intracellular lipolysis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1862, 1221–1232 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang M.-D., Huang A. H. C., Bioinformatics reveal five lineages of oleosins and the mechanism of lineage evolution related to structure/function from green algae to seed plants. Plant Physiol. 169, 453–470 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siloto R. M. P., et al. , The accumulation of oleosins determines the size of seed oilbodies in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18, 1961–1974 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miquel M., et al. , Specialization of oleosins in oil body dynamics during seed development in Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Physiol. 164, 1866–1878 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tzen J. T. C., Lai Y.-K., Chan K.-L., Huang A. H. C., Oleosin isoforms of high and low molecular weights are present in the oil bodies of diverse seed species. Plant Physiol. 94, 1282–1289 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Andrea S., Lipid droplet mobilization: The different ways to loosen the purse strings. Biochimie 120, 17–27 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jolivet P., et al. , Protein composition of oil bodies in Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype WS. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 42, 501–509 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jolivet P., et al. , Protein composition of oil bodies from mature Brassica napus seeds. Proteomics 9, 3268–3284 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai Y., et al. , Mouse fat storage-inducing transmembrane protein 2 (FIT2) promotes lipid droplet accumulation in plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15, 824–836 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaushik S., Cuervo A. M., Degradation of lipid droplet-associated proteins by chaperone-mediated autophagy facilitates lipolysis. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 759–770 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu G., et al. , Post-translational regulation of adipose differentiation-related protein by the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42841–42847 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu G., Sztalryd C., Londos C., Degradation of perilipin is mediated through ubiquitination-proteasome pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1761, 83–90 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deruyffelaere C., et al. , Ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation of oleosins is involved in oil body mobilization during post-germinative seedling growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 56, 1374–1387 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deruyffelaere C., et al. , PUX10 is a CDC48A adaptor protein that regulates the extraction of ubiquitinated oleosins from seed lipid droplets in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 30, 2116–2136 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kretzschmar F. K., et al. , PUX10 is a lipid droplet-localized scaffold protein that interacts with CELL DIVISION CYCLE48 and is involved in the degradation of lipid droplet proteins. Plant Cell 30, 2137–2160 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esnay N., Dyer J. M., Mullen R. T., Chapman K. D., Lipid droplet–peroxisome connections in plants. Contact 3, 2515256420908765 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reumann S., Bartel B., Plant peroxisomes: Recent discoveries in functional complexity, organelle homeostasis, and morphological dynamics. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 34, 17–26 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okumoto K., Tamura S., Honsho M., Fujiki Y., “Peroxisome: Metabolic functions and biogenesis” in Peroxisome Biology: Experimental Models, Peroxisomal Disorders and Neurological Diseases, Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, Lizard G., Ed. (Springer International Publishing, 2020), pp. 3–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strader L. C., Bartel B., Transport and metabolism of the endogenous auxin precursor indole-3-butyric acid. Mol. Plant 4, 477–486 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kao Y.-T., Gonzalez K. L., Bartel B., Peroxisome function, biogenesis, and dynamics in plants. Plant Physiol. 176, 162–177 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao Y., Skowyra M. L., Feng P., Rapoport T. A., Protein import into peroxisomes occurs through a nuclear pore–like phase. Science 378, eadf3971 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skowyra M. L., Rapoport T. A., PEX5 translocation into and out of peroxisomes drives matrix protein import. Mol. Cell 82, 3209–3225.e7 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng P., et al. , A peroxisomal ubiquitin ligase complex forms a retrotranslocation channel. Nature 607, 374–380 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koller A., et al. , Pex22p of Pichia pastoris, essential for peroxisomal matrix protein import, anchors the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, Pex4p, on the peroxisomal membrane. J. Cell Biol. 146, 99–112 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Traver M. S., et al. , The structure of the Arabidopsis PEX4-PEX22 peroxin complex—insights into ubiquitination at the peroxisomal membrane. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 838923 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zolman B. K., Monroe-Augustus M., Silva I. D., Bartel B., Identification and functional characterization of Arabidopsis PEROXIN4 and the interacting protein PEROXIN22. Plant Cell 17, 3422–3435 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grou C. P., et al. , Members of the E2D (UbcH5) family mediate the ubiquitination of the conserved cysteine of Pex5p, the peroxisomal import receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 14190–14197 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eastmond P. J., SUGAR-DEPENDENT1 encodes a patatin domain triacylglycerol lipase that initiates storage oil breakdown in germinating Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Cell 18, 665–675 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thazar-Poulot N., Miquel M., Fobis-Loisy I., Gaude T., Peroxisome extensions deliver the Arabidopsis SDP1 lipase to oil bodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 4158–4163 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Footitt S., et al. , Control of germination and lipid mobilization by COMATOSE, the Arabidopsis homologue of human ALDP. EMBO J. 21, 2912–2922 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zolman B. K., Silva I. D., Bartel B., The Arabidopsis pxa1 mutant is defective in an ATP-binding cassette transporter-like protein required for peroxisomal fatty acid β-oxidation. Plant Physiol. 127, 1266–1278 (2001). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cui S., et al. , Sucrose production mediated by lipid metabolism suppresses physical interaction of peroxisomes and oil bodies during germination of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 19734–19745 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wright Z. J., Bartel B., Peroxisomes form intralumenal vesicles with roles in fatty acid catabolism and protein compartmentalization in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 11, 6221 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daks A., et al. , The role of E3 ligase Pirh2 in disease. Cells 11, 1515 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jumper J., et al. , Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Varadi M., et al. , AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D439–D444 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alonso J. M., et al. , Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 301, 653–657 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee H. G., Seo P. J., The Arabidopsis MIEL1 E3 ligase negatively regulates ABA signalling by promoting protein turnover of MYB96. Nat. Commun. 7, 12525 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marino D., et al. , Arabidopsis ubiquitin ligase MIEL1 mediates degradation of the transcription factor MYB30 weakening plant defence. Nat. Commun. 4, 1476 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lingard M. J., Monroe-Augustus M., Bartel B., Peroxisome-associated matrix protein degradation in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 4561–4566 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hayashi M., Toriyama K., Kondo M., Nishimura M., 2,4-dichlorophenoxybutyric acid–resistant mutants of Arabidopsis have defects in glyoxysomal fatty acid β-oxidation. Plant Cell 10, 183–195 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zolman B. K., Yoder A., Bartel B., Genetic analysis of indole-3-butyric acid responses in Arabidopsis thaliana reveals four mutant classes. Genetics 156, 1323–1337 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kao Y.-T., Fleming W. A., Ventura M. J., Bartel B., Genetic interactions between PEROXIN12 and other peroxisome-associated ubiquitination components. Plant Physiol. 172, 1643–1656 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zimmermann L., et al. , A completely reimplemented MPI bioinformatics toolkit with a new HHpred server at its core. J. Mol. Biol. 430, 2237–2243 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sheng Y., et al. , Molecular basis of Pirh2-mediated p53 ubiquitylation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 1334–1342 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leng R. P., et al. , Pirh2, a p53-induced ubiquitin-protein ligase, promotes p53 degradation. Cell 112, 779–791 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hakem A., et al. , Role of Pirh2 in mediating the regulation of p53 and c-Myc. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002360 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hayashi M., et al. , Loss of XRN4 function can trigger cosuppression in a sequence-dependent manner. Plant Cell Physiol. 53, 1310–1321 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fan J., Yan C., Zhang X., Xu C., Dual role for Phospholipid: Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase: Enhancing fatty acid synthesis and diverting fatty acids from membrane lipids to triacylglycerol in Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Cell 25, 3506–3518 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhai Z., Liu H., Shanklin J., Ectopic expression of OLEOSIN 1 and inactivation of GBSS1 have a synergistic effect on oil accumulation in plant leaves. Plants 10, 513 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shimada T. L., Shimada T., Hara-Nishimura I., A rapid and non-destructive screenable marker, FAST, for identifying transformed seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 61, 519–528 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fan J., Yu L., Xu C., Dual role for autophagy in lipid metabolism in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 31, 1598–1613 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shaner N. C., et al. , A bright monomeric green fluorescent protein derived from Branchiostoma lanceolatum. Nat. Methods 10, 407–409 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu L., Fan J., Zhou C., Xu C., Sterols are required for the coordinated assembly of lipid droplets in developing seeds. Nat. Commun. 12, 5598 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vailleau F., et al. , A R2R3-MYB gene, AtMYB30, acts as a positive regulator of the hypersensitive cell death program in plants in response to pathogen attack. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 10179–10184 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shimada T. L., Shimada T., Takahashi H., Fukao Y., Hara-Nishimura I., A novel role for oleosins in freezing tolerance of oilseeds in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 55, 798–809 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bülow M. H., et al. , Unbalanced lipolysis results in lipotoxicity and mitochondrial damage in peroxisome-deficient Pex19 mutants. Mol. Biol. Cell 29, 396–407 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Deshaies R. J., Joazeiro C. A. P., RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 399–434 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huang S., et al. , The plant ESCRT component FREE1 regulates peroxisome-mediated turnover of lipid droplets in germinating Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Cell 34, 4255–4273 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Akhter D., Zhang Y., Hu J., Pan R., Protein ubiquitination in plant peroxisomes. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 65, 371–380 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Muhammad D., Smith K. A., Bartel B., Plant peroxisome proteostasis—Establishing, renovating, and dismantling the peroxisomal proteome. Essays Biochem. 66, 229–242 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jiménez-López D., Muñóz-Belman F., González-Prieto J. M., Aguilar-Hernández V., Guzmán P., Repertoire of plant RING E3 ubiquitin ligases revisited: New groups counting gene families and single genes. PLoS One 13, e0203442 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stone S. L., et al. , Functional analysis of the RING-type ubiquitin ligase gamily of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 137, 13–30 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hindt M. N., et al. , BRUTUS and its paralogs, BTS LIKE1 and BTS LIKE2, encode important negative regulators of the iron deficiency response in Arabidopsis thaliana. Metallomics 9, 876–890 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kobayashi T., et al. , Iron-binding haemerythrin RING ubiquitin ligases regulate plant iron responses and accumulation. Nat. Commun. 4, 2792 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Long T. A., et al. , The bHLH transcription factor POPEYE regulates response to iron deficiency in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell 22, 2219–2236 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rodríguez-Celma J., Chou H., Kobayashi T., Long T. A., Balk J., Hemerythrin E3 ubiquitin ligases as negative regulators of iron homeostasis in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 98 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Selote D., Samira R., Matthiadis A., Gillikin J. W., Long T. A., Iron-binding E3 ligase mediates iron response in plants by targeting basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors. Plant Physiol. 167, 273–286 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Selote D., Matthiadis A., Gillikin J. W., Sato M. H., Long T. A., The E3 ligase BRUTUS facilitates degradation of VOZ1/2 transcription factors. Plant Cell Environ. 41, 2463–2474 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ding S., Zhang B., Qin F., Arabidopsis RZFP34/CHYR1, a ubiquitin E3 ligase, regulates stomatal movement and drought tolerance via SnRK2.6-mediated phosphorylation. Plant Cell 27, 3228–3244 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu H., et al. , CHYR1 ubiquitinates the phosphorylated WRKY70 for degradation to balance immunity in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 230, 1095–1109 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Berglund L., et al. , A genecentric Human Protein Atlas for expression profiles based on antibodies. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 7, 2019–2027 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Krahmer N., Farese R. V., Walther T. C., Balancing the fat: Lipid droplets and human disease. EMBO Mol. Med. 5, 905–915 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gluchowski N. L., Becuwe M., Walther T. C., Farese R. V., Lipid droplets and liver disease: From basic biology to clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14, 343–355 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gibson D. G., et al. , Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat. Methods 6, 343–345 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Michniewicz M., Frick E. M., Strader L. C., Gateway-compatible tissue-specific vectors for plant transformation. BMC Res. Notes 8, 63 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Normanly J., Grisafi P., Fink G. R., Bartel B., Arabidopsis mutants resistant to the auxin effects of indole-3-acetonitrile are defective in the nitrilase encoded by the NIT1 gene. Plant Cell 9, 1781–1790 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Phillips C., Gene variant identifier. Github. https://github.com/cp-bioinfo/gene-variant-identifier Accessed 24 February 2023.

- 85.Llinas R. J., Genetic suppressors reveal varying methods for improving peroxisome function in Arabidopsis peroxin mutants. Rice University (2021), (25 February 2023). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.