Abstract

Background

Adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD) is a rare systemic autoinflammatory condition characterized by a classical triad of symptoms that include prolonged fever, polyarthritis, and a characteristic salmon-pink skin rash. It can affect a variety of organ systems resulting in many different clinical presentations and is usually a diagnosis of exclusion. Myocarditis complicated by cardiogenic shock is a rare and life-threatening manifestation of AOSD, typically affecting younger patients. There is a limited experience and evidence in how best to manage this challenging patient cohort.

Case summary

A previously fit and well 22-year-old male presented with fever, arthralgia, and general malaise. On clinical examination, he was pyrexial and hypotensive, requiring vasopressor support for presumed septic shock. Subsequent transthoracic echocardiography and cardiac MRI findings were in keeping with fulminant myocarditis. Further septic and auto-immune screens were negative although he responded well to high-dose intravenous corticosteroids. Attempts to wean immunosuppression were unsuccessful, and his ferritin was markedly elevated (20 233 μg/L). A diagnosis of AOSD was suspected after exclusion of other possible causes. The successful addition of tocilizumab (an interleukin-6 receptor antagonist) therapy allowed for gradual de-escalation of steroid therapy and disease remission, with on-going remission at 18 months on maintenance therapy.

Discussion

This case highlights the importance of considering AOSD as a rare cause for myocarditis, especially when fever is present, or disease is severe. Failure to improve with first-line therapy involving high-dose corticosteroids, or inability to wean that therapy, should prompt consideration for escalation of therapy, with tocilizumab seemingly an effective treatment option.

Keywords: Case report, Myocarditis, Adult-onset Still’s disease, Tocilizumab, Hyperferritinaemia

Learning points.

Adult-onset Still’s disease is a rare cause of severe myocarditis and is more common in younger patients.

Adult-onset Still’s disease is associated with a markedly elevated serum ferritin, and the classic clinical triad of fever, rash, and arthritis.

Diagnosis and initial management of myocarditis in this population does not differ from myocarditis of other causes.

Consider tocilizumab in patients who do not respond to, or fail to wean, high-dose corticosteroids.

Introduction

Adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD) is a rare systemic autoinflammatory condition with an estimated prevalence of <1 case per 100 000 person years.1–3 It commonly affects younger people with an equal sex distribution, and bimodal age distribution (ages 15–25 and 36–46).4 It is characterized by a triad of symptoms—prolonged fever, polyarthritis, and a characteristic salmon-pink rash.1–3,5–8 It can manifest in many ways affecting multiple organ systems. Diagnosis is made by exclusion and less commonly by comparison to Yamaguchi’s criteria.1,2,8–10 Cardiopulmonary manifestations of AOSD are well documented, and include pericarditis, myocarditis, and pleuritis.1–3,8–11 Myocarditis is a rare clinical manifestation of AOSD, with a prevalence of roughly 7% in these patients.1,2,11 This presents both diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. As AOSD typically affects younger people, it should be considered as a differential when managing patients with myocarditis.1,2

Summary figure

| Day 0 | Patient presented to hospital with a 4-day history of fever, myalgia, arthralgia, and sore throat, alongside a 2-day history of vomiting and diarrhoea. |

| Day 1 | Intensive care admission due to worsening shock. Commenced high-dose intravenous steroids. Transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrates severe global left ventricular impairment. Troponin elevated. Likely diagnosis of myocarditis considered. |

| Day 5 | Cardiac MRI consistent with myocarditis. |

| Day 10 | Attempt to de-escalate intravenous to oral steroid therapy unsuccessful with clinical and biochemical deterioration. |

| Day 12 | Iron studies reveal a markedly elevated ferritin. |

| Day 14 | Re-attempt to de-escalate intravenous to oral steroid therapy unsuccessful. |

| Day 15 | Rheumatology review with strong suspicion for diagnosis of Adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD). |

| Day 16 | New maculopapular rash, consistent with AOSD diagnosis. |

| Day 17 | Commencement of pulsed i.v. methylprednisolone and initial infusion of tocilizumab (4 mg/kg). |

| Day 18 | First signs of sustained clinical and biochemical improvement noted. |

| Day 23 | Transitioned to oral prednisone 100 mg once daily. |

| Day 25 | Discharged home on tapering oral prednisone course. |

| Day 37 | Signs of clinical and biochemical relapse. |

| Day 41 | Second infusion of tocilizumab (4 mg/kg). |

| Day 63 | Tocilizumab dose escalated to 8 mg/kg for third infusion due to recurrent symptoms prior to second infusion. |

| Day 69 | First repeated blood tests after tocilizumab dose escalation demonstrate biochemical remission. |

| 6 months | Ceased prednisone. Clinical and biochemical remission on continued monthly tocilizumab infusions (8 mg/kg). |

| 10 months | Transitioned to fortnightly subcutaneous adalimumab. |

| 18 months | Repeat cardiac MRI shows no evidence of on-going inflammation. |

The mainstay of treatment for AOSD is immunosuppression with high-dose corticosteroids.3,5–7,9 However, in cases where there is cardiac involvement, first-line therapy may fail.1,10 In such cases, there is increasing evidence that supports the use of agents that suppress the activity of interleukin-1 (IL-1) and interleukin-6 (IL-6).3,6,7,10

Here, we present a case of refractory, fulminant myocarditis as a rare manifestation of adult-onset Still’s disease, requiring escalating immunosuppression therapy. This case builds on the limited existing experience in managing such patients providing further evidence supporting the use of tocilizumab (an IL-6 receptor antagonist) in a patient with refractory disease.

Case presentation

A 22-year-old male presented with a 4-day history of fever, myalgia, arthralgia, and sore throat, alongside a 2-day history of vomiting and diarrhoea. He was a non-smoker, with no regular medications or past medical history. There was no recreational drug history or family history of note.

Clinical examination revealed a fever of 38.4°C. His pulse was 89 beats per minute, blood pressure 77/34 mmHg, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturations 98% on room air. He was noted as having a regular pulse with cool peripheries, normal heart sounds with no added sounds, and no evidence of fluid overload. Clinical examination with otherwise unremarkable.

Full blood count demonstrated a normal haemoglobin (148 g/L, n = 130–175) with mild thrombocytopaenia (146×10⁹/L, n = 150–400), and a leukocytosis (22.87×10⁹/L, n = 4.0–11.0) with predominant neutrophilia (13.61×10⁹/L, n = 1.9–7.5), monocytosis (2.88×10⁹/L, n = 0.2–1.0), lymphopaenia (0.82×10⁹/L, n = 1.0–4.0), and normal eosinophils (0.17×10⁹/L, n < 0.6) and basophils (0.04×10⁹/L, n = 0.0–0.2). Other laboratory findings included an acute kidney injury [creatinine 333 μmol/L (n = 60–105), urea 22.2 mmol/L (n = 3.2–7.7)], mildly deranged liver function tests [bilirubin 22 μmol/L (n < 25), AST 123 U/L (n < 45), ALT 46 U/L (n < 45), GGT 19 U/L (n = 0–60), ALP 154 U/L (n = 40–110)], high-sensitivity troponin T (hsTnT) of 4550 ng/L (n < 15), and elevated NT-proBNP (1485 pmol/L, n < 35). C-reactive protein was markedly elevated (415 mg/L, n < 5), and lactate raised (3.6 mmol/L, n < 1.9). There was mild hyponatraemia (129 mmol/L, n = 135–145), while potassium (3.7 mmol/L, n = 3.5–5.2) was within normal limits. Electrocardiogram demonstrated sinus rhythm with right-axis deviation and diffuse ST-segment elevation. Chest radiograph was unremarkable.

Initial impression was of septic shock from a presumed viral illness complicated by myocarditis, acute kidney injury, and metabolic acidosis. Due to worsening shock, he was transferred to the intensive care unit for vasopressor support, initially with noradrenaline and then dobutamine. He was commenced on empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics, and high-dose intravenous (i.v.) dexamethasone (10 mg four times daily). He responded well to therapy with clinical and biochemical improvement.

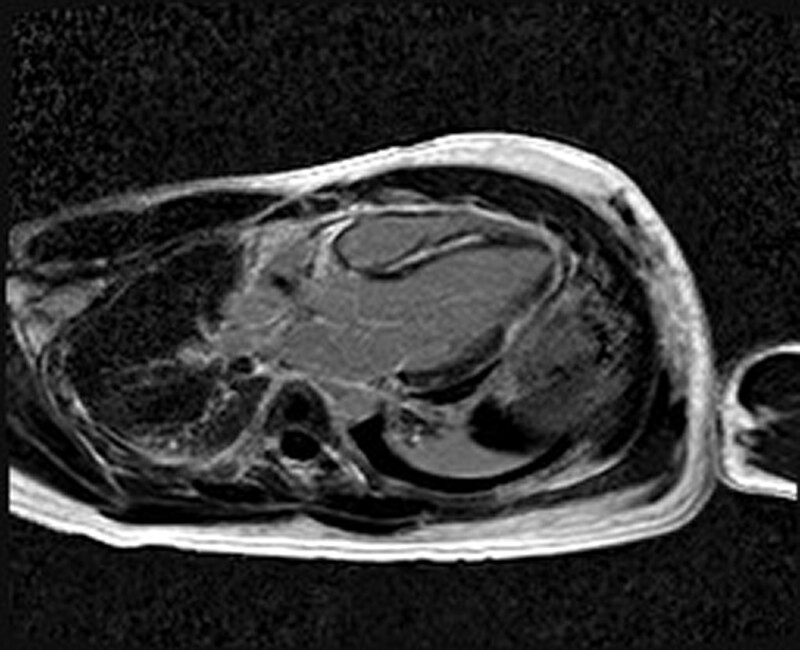

Transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated severe global left ventricular (LV) systolic impairment (ejection fraction 35%), with normal LV size and wall thickness. The right ventricle had moderate systolic impairment. There was no significant valvular pathology or pericardial effusion. Endomyocardial biopsy demonstrated features of subtle interstitial lymphocytes and oedema, without associated myonecrosis. There were no giant cells, eosinophils, granulomas, or fibrosis, while stains for amyloid and iron were negative. Overall, this was felt to represent possible myocarditis without any specific features. Cardiac MRI performed on Day 4 after steroid commencement showed improved cardiac function (without having received any heart failure therapy), with high myocardial T2 signal indicative of myocardial oedema, as well as extensive circumferential late gadolinium enhancement in a subepicardial distribution, consistent with acute myocarditis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cardiac MRI demonstrating extensive subepicardial LGE consistent with myocarditis.

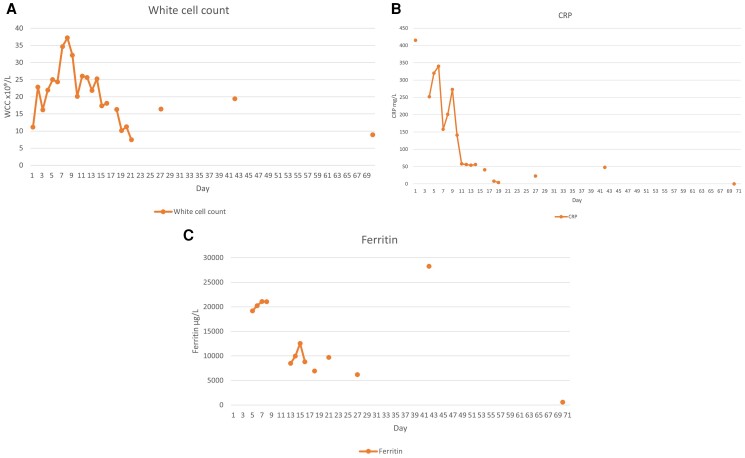

Two attempts were made to transition to oral steroid therapy (Day 10, Day 14). Both were unsuccessful, with clinical and biochemical deterioration noted within 12 h of steroid de-escalation. This manifested as mild hypotension, fever, chest pain, and rising inflammatory markers (Figure 2A–C). In both cases, this resolved with reinstatement of i.v. steroid.

Figure 2.

(A) Graph representing course of white blood cell count during illness. (B) Graph representing course of C-reactive protein during illness. (C) Graph representing course of ferritin during illness.

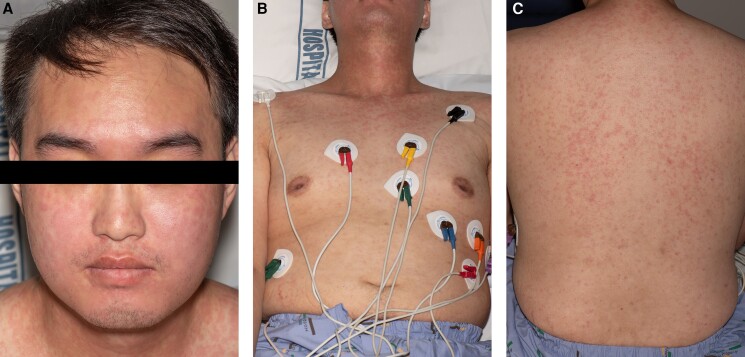

Extensive testing excluded infectious and immunological causes of myocarditis (Table 1). The patient’s ferritin was markedly elevated at 20 233 μg/L (n = 20–320) with a low glycosylated ferritin percentage of 5% (n = 50–80%). Haematology review and bone marrow biopsy did not support a diagnosis of haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Given the markedly elevated ferritin levels with low glycosylated ferritin, failure to wean i.v. steroids, absence of infection, low/negative antinuclear antibody (ANA) and rheumatoid factor, the diagnosis of AOSD was considered following Rheumatology review. Bedside USS revealed mild extensor tendon oedema of both ankles, as well as bilateral knee joint effusions with synovial thickening supporting the diagnosis of AOSD. He developed a new maculopapular rash over his neck, face, and back; gradually progressing to his arms and trunk. There was no skin peeling or involvement of the oral mucosa. Skin biopsy was consistent with the cutaneous manifestation of Still’s disease and not of a delayed drug reaction (Figure 3A–C). No lymphadenopathy or organomegaly was noted at any point.

Table 1.

Investigations performed to rule out infectious and auto-immune causes of myocarditis

| Infectious—all test results negative | |

|---|---|

| Atypical pneumonia polymerase chain reaction (PCR) | Blood culture |

| Cytomegalovirus (CMV) serology | Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) serology |

| SARS-CoV-2 PCR and serology | Enterovirus PCR |

| Gastrointestinal bacteria PCR | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serology |

| Hepatitis serology | Legionella serology |

| Human Herpes Virus (HHV) 6 and 8 serology | Leptospirosis PCR |

| Mycoplasma PCR and serology | QuantiFERON-TB gold testing |

| Parvovirus PCR | Rickettsia serology |

| Q-fever serology | |

| Extended Respiratory Viral Panel: | |

| – Adenovirus, Coronavirus (229E, HKU1, NL63, CC43), MERS coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, Human Metapneumovirus, Human Rhino/enterovirus, Influenza A/B, Parainfluenza (1,2,3,4), Respiratory Syncytial Virus, Bordetella parapertussis, Bordetella pertussis, Chlamydophila pneumonia | |

| Auto-immune—all test results negative | |

| Anti-double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid antibodies (dsDNA Abs) | Anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA) |

| Antinuclear antibody (ANA) | Extractible nuclear antibody (ENA) |

| Rheumatoid factor (RF) | Myositis Panel |

Figure 3.

(A) Rash involving face and neck. (B) Rash involving trunk. (C) Rash involving back.

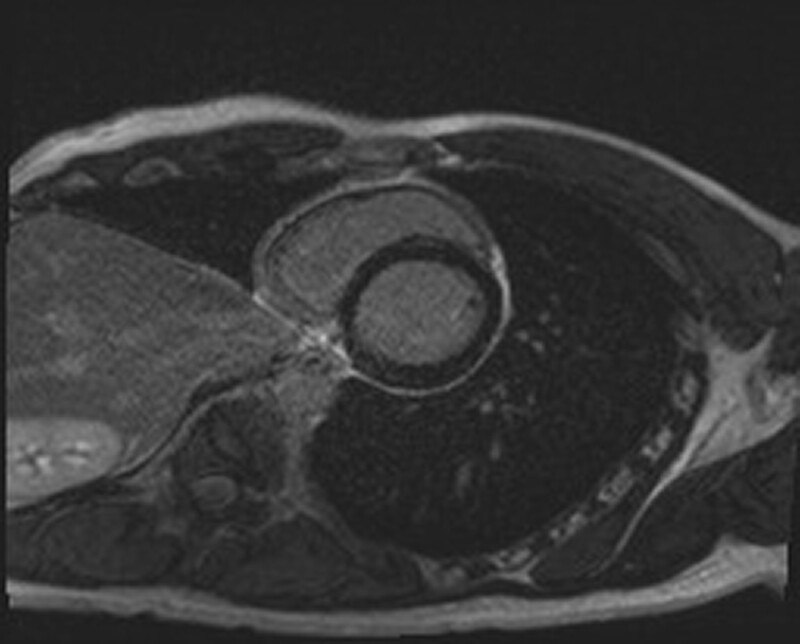

The patient received pulsed methylprednisolone for 6 days and given an infusion of tocilizumab (4 mg/kg), with early signs of clinical and biochemical improvement within 1 day (Figure 2A–C). He was then transitioned to oral prednisone 100 mg once daily. At Day 25, he was discharged home on a tapering regimen of oral prednisone with monthly tocilizumab infusions. Signs of clinical and biochemical relapse on Day 37, just prior to his second infusion, prompted tocilizumab dose escalation to 8 mg/kg for his third infusion, given on Day 63, with immediate improvement (Figure 2A–C). Six months on, he had weaned off prednisone and continued tocilizumab infusions without any clinical or biochemical signs of active disease (hsTnT 16 ng/L, WCC 3.8×10⁹/L, ferritin 360 μg/L, C-reactive protein < 1 mg/L, and creatinine 96 μmol/L) (see Supplementary material online Figures). Due to a global tocilizumab shortage during the COVID-19 pandemic, he was transitioned to fortnightly subcutaneous adalimumab 40 mg, an anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) agent, with continued disease control. Repeat cardiac MRI at 18 months showed no evidence of on-going inflammation (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cardiac MRI demonstrating subepicardial expansion consistent with fibrosis due myocarditis without active inflammation.

Discussion

Adult-onset Still’s disease patients with cardiac involvement generally demonstrate more marked leukocytosis, and neutrophilia, as well as higher levels of ferritin and C-reactive protein when compared to those without cardiac involvement.2,10 Furthermore, myocardial involvement tends to confer a worse prognosis, and is associated with higher rates of intensive care admission.1,3,10,11 Pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1, IL-6, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), and TNF-α are involved in the pathogenesis of AOSD, and thus remain potential targets for future therapies.6,7,12

Diagnosis and management of myocarditis and heart failure in AOSD do not differ from management of myocarditis and heart failure in other conditions, involving suppression of the underlying disease, along with guideline directed medical therapy for those with systolic dysfunction.2,11 It is variably associated with high-sensitivity troponin elevations, non-specific T-wave and ST-segment ECG changes, impaired left ventricular ejection fraction on echocardiography, and myocardial inflammation on cardiac MRI.1,2,9 Endomyocardial biopsy may be required to exclude other causes.1,2

First-line therapy is with high-dose corticosteroids.3,5–7,9,10 Adult-onset Still’s disease with cardiac involvement is more likely to be refractory to first-line therapy, as was seen in our case.1,10 Failing first-line treatment, methotrexate may be considered for patients with predominant arthritis. However, in patients with severe systemic inflammation and cardiac involvement consideration should be given to the use of agents that suppress the activity of IL-1 and IL-6.3,6,10

Several cases have been published demonstrating the efficacy of anakinra (an IL-1 receptor antagonist) in AOSD patients with myocarditis refractory to corticosteroids.10 Seemingly less evidence exists in relation to tocilizumab.10 A recent multi-centre retrospective study documented myocarditis as a rare cardiac complication of AOSD, describing two out of four patients with disease refractory to treatment with corticosteroids alone or with methotrexate.10 Both were successfully treated with anakinra, while none received tocilizumab for this indication.10 A small randomized-controlled trial suggested efficacy of tocilizumab in 27 AOSD patients with various manifestations who were refractory to glucocorticoid therapy.5 Similarly, a retrospective review published in 2021 further demonstrated tocilizumab as an efficacious treatment among 39 patients with treatment resistant AOSD.13 However, neither of these articles specifically detail myocarditis as a complication of AOSD, nor the severity of disease. A case report from 2014 did describe the successful use of tocilizumab in a patient with fulminant myocarditis and macrophage activation syndrome as a consequence of AOSD.12 Here, they observed worsening cardiac failure despite i.v. corticosteroids and anakinra, eventually demonstrating clinical improvement with tocilizumab.12

In summary, while rare, AOSD should be considered as an underlying cause for myocarditis, especially when fever is present, or disease is refractory. Diagnosis can be aided by assessment of serum ferritin (elevated in 70% of patients), and application to the Yamaguchi criteria.10,14 Failure to improve with first-line therapy, or inability to wean corticosteroid therapy, should prompt urgent consideration for escalation of therapy. While there is increasing evidence for the use of anakinra in this population, tocilizumab also seems to be an effective treatment option.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Michael Dick, Department of Cardiology, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Road, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand; Cardiology Services, Tauranga Hospital, 829 Cameron Road, Tauranga South, Tauranga 3112, New Zealand.

Kyra Innes-Jones, Cardiology Services, Tauranga Hospital, 829 Cameron Road, Tauranga South, Tauranga 3112, New Zealand.

Satpal Arri, Department of Cardiology, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Road, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand.

Lead author biography

Michael is a Cardiology Advanced Trainee Registrar, currently based at Tauranga Hospital, having previously worked at Auckland City Hospital under the supervision of co-author Dr Satpal Arri. He has a broad range of interests within cardiology as he continues his general cardiology training. Outside of work, Michael loves to travel whenever he can. He is also a keen runner and general sports fanatic.

Michael is a Cardiology Advanced Trainee Registrar, currently based at Tauranga Hospital, having previously worked at Auckland City Hospital under the supervision of co-author Dr Satpal Arri. He has a broad range of interests within cardiology as he continues his general cardiology training. Outside of work, Michael loves to travel whenever he can. He is also a keen runner and general sports fanatic.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal – Case Reports online.

Consent: Informed written patient consent has been obtained, in line with the COPE best practice guidelines, and the individual who is being reported on is aware of the possible consequences of that reporting.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research and authorship of this publication.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material. Any additional readers require relating to this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Gracia-Ramos AE, Contreras-Ortíz JA. Myocarditis in adult-onset Still’s disease: case-based review. Clin Rheumatol 2020;39:933–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gerfaud-Valentin M, Sève P, Iwaz J, Gagnard A, Broussolle C, Durieu I, et al. Myocarditis in adult-onset Still disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93:280–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fauter M, Gerfaud-Valentin M, Delplanque M, Georgin-Lavialle S, Sève P, Jamilloux Y. [Adult-onset Still’s disease complications]. Rev Med Interne 2020;41:168–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Magadur-Joly G, Billaud E, Barrier JH, Pennec YL, Masson C, Renou P, et al. Epidemiology of adult Still’s disease: estimate of the incidence by a retrospective study in west France. Ann Rheum Dis 1995;54:587–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kaneko Y, Kameda H, Ikeda K, Ishii T, Murakami K, Takamatsu H, et al. Tocilizumab in patients with adult-onset Still’s disease refractory to glucocorticoid treatment: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:1720–1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Efthimiou P, Georgy S. Pathogenesis and management of adult-onset Still’s disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2006;36:144–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Castañeda S, Martínez-Quintanilla D, Martín-Varillas JL, García-Castañeda N, Atienza-Mateo B, González-Gay MA. Tocilizumab for the treatment of adult-onset Still’s disease. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2019;19:273–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gupta D, Jagani R, Mendonca S, Rathi KR. Adult-onset Still’s disease with myocarditis and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: rare manifestation with fatal outcome. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2016;59:84–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vandergheynst F, Gosset J, Van De Borne P, Decaux G. Myopericarditis revealing adult-onset Still’s disease. Acta Clin Belg 2005;60:205–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bodard Q, Langlois V, Guilpain P, Le Quellec A, Vittecoq O, Noel D, et al. Cardiac involvement in adult-onset Still’s disease: manifestations, treatments and outcomes in a retrospective study of 28 patients. J Autoimmun 2021;116:102541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kumar M, Tandun V, Lia NL, Jain S. Still’s disease and myopericarditis. Cureus 2019;11:e4900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Savage E, Wazir T, Drake M, Cuthbert R, Wright G. Fulminant myocarditis and macrophage activation syndrome secondary to adult-onset Still’s disease successfully treated with tocilizumab. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53:1352–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kir S, Özgen M, Zontul S. Adult-onset Still’s disease and treatment results with tocilizumab. Int J Clin Pract 2021;75:e13936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ohta A, Yamaguchi M, Tsunematsu T, Kasukawa R, Mizushima H, Kashiwagi H, et al. Adult Still’s disease: a multicenter survey of Japanese patients. J Rheumatol 1990;17:1058–1063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material. Any additional readers require relating to this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.