Abstract

Objectives

To explore clustering of comorbidities among patients with a new diagnosis of OA and estimate the 10-year mortality risk for each identified cluster.

Methods

This is a population-based cohort study of individuals with first incident diagnosis of OA of the hip, knee, ankle/foot, wrist/hand or ‘unspecified’ site between 2006 and 2020, using SIDIAP (a primary care database representative of Catalonia, Spain). At the time of OA diagnosis, conditions associated with OA in the literature that were found in ≥1% of the individuals (n = 35) were fitted into two cluster algorithms, k-means and latent class analysis. Models were assessed using a range of internal and external evaluation procedures. Mortality risk of the obtained clusters was assessed by survival analysis using Cox proportional hazards.

Results

We identified 633 330 patients with a diagnosis of OA. Our proposed best solution used latent class analysis to identify four clusters: ‘low-morbidity’ (relatively low number of comorbidities), ‘back/neck pain plus mental health’, ‘metabolic syndrome’ and ‘multimorbidity’ (higher prevalence of all studied comorbidities). Compared with the ‘low-morbidity’ cluster, the ‘multimorbidity’ cluster had the highest risk of 10-year mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [HR]: 2.19 [95% CI: 2.15, 2.23]), followed by the ‘metabolic syndrome’ cluster (adjusted HR: 1.24 [95% CI: 1.22, 1.27]) and the ‘back/neck pain plus mental health’ cluster (adjusted HR: 1.12 [95% CI: 1.09, 1.15]).

Conclusion

Patients with a new diagnosis of OA can be clustered into groups based on their comorbidity profile, with significant differences in 10-year mortality risk. Further research is required to understand the interplay between OA and particular comorbidity groups, and the clinical significance of such results.

Keywords: epidemiology, OA, comorbidities, clustering

Rheumatology key messages.

Patients with newly diagnosed osteoarthritis can by classified into different clusters by their comorbidity patterns.

The main patient sub-groups were ‘low-morbidity’, ‘back/neck pain plus mental health’, ‘metabolic syndrome’ and ‘multimorbidity’.

Such classification can help identify ‘high-risk’ patients who require more intense attention from healthcare providers.

Introduction

OA is a common chronic condition affecting about 250 million people worldwide [1]. The progressive degenerative nature of the disease causes functional impairment, often severe pain, and loss of quality of life [2]. Given its chronic nature, OA often coexists alongside other chronic conditions (i.e. comorbidities). A systematic review has shown that patients with OA are more likely to have multiple conditions compared with patients without OA [3], and further studies have shown that this increased likelihood exists both in the years preceding a diagnosis of OA and in the years after [4].

The co-existence of two or more chronic conditions or comorbidities is termed multimorbidity [5], and is estimated to affect between 19 and 27% of the UK general population [6–8]. Studies have shown that increasing multimorbidity is associated with lower socioeconomic status [7, 8] and increasing age [7], and that it can drive higher healthcare utilization including primary care usage, prescription costs and hospitalization [8, 9]. There is a growing realization of the need to better understand multimorbidity, both in clinical practice and in the development of clinical guidelines [10, 11].

Within the context of multimorbidity, there is increasing recognition of the concept of comorbidities existing in groups or ‘clusters’ [12]. Examining the exact conditions that co-exist within an individual, rather than simply the number of comorbidities, would allow us to understand whether a patient’s chronic comorbid conditions are ‘concordant’ (may be treated with a unified approach) or ‘discordant’ (may worsen or compete with treatments for individual conditions) [13], with important repercussions for the treatment of that individual, including polypharmacy [14].

Clustering of comorbidities among individuals with OA through routinely collected data has only recently started to be explored. Studies examining general multimorbidity have shown that musculoskeletal problems including OA are very common among people with multimorbidity [15], and often cluster with cardiovascular disease [16, 17]. OA is a particularly common contributor to multimorbidity among the elderly [17]. Such multimorbidity involving OA not only leads to further negative effects on quality of life, but also complicates treatment and increases requirements for analgesia [18]. With respect to the clustering of comorbidities specifically in individuals with OA, one large scale study in the UK has recently demonstrated five distinct clusters of comorbidities that predicted general practice (GP) consultation rates and mortality [19].

In this study we used clustering techniques to examine large-scale, routinely collected data from patients with OA to further explore clustering of comorbidities in primary care patients with OA in the Spanish population.

Methods

Study design, setting and data sources

We conducted a population-based cohort study using the Information System for Research in Primary Care (SIDIAP) healthcare database, which collects de-identified patient records from 279 primary care providers in Catalonia, Spain, covering around 80% of the Catalan population, or 5.8 million people [20]. Diagnosis of conditions in the primary care system in Catalonia, and therefore in SIDAP data as well, are based on the International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10 codes), and has been internationally validated [21]. This study forms part of the Comorbidities in Osteoarthritis (ComOA) project, the protocol for which has been published previously [22].

Participants and study size

We included all participants aged ≥18 years with at least one physician-recorded diagnosis of OA of the hip, knee, ankle/foot, wrist/hand, general or ‘unspecified’ site between 1 January 2006 and 31 June 2020, using ICD-10 codes. The index date (date of their first incidence diagnosis of OA) was identified for each participant, and participants were followed from this date. Participants were excluded if they did not have at least one year of data recorded prior to their index date, or if they had a specific non-OA diagnosis (soft-tissue disorders, other bone/cartilage diseases) at the same joint in the 12 months prior to or after the index OA/joint pain date.

Outcomes

The outcomes of interest were (i) clusters of comorbidities in people with OA and (ii) risk of mortality in 10 years. For mortality follow-up: individuals were followed from the date of OA diagnosis until the earliest of (i) date of death or (ii) date of transfer out of catchment area or end-date of data availability in SIDIAP.

Variables

Baseline Characteristics

A set of baseline characteristics from individuals at index date was used to describe the population (Table 1) but not included in the cluster model: recorded site of OA diagnosis (hip, knee, ankle/foot, wrist/hand, general or ‘unspecified’), sex, age, body mass index (BMI), socioeconomic status, smoking (categorized into never, ex- or current smoker) and alcohol risk (categorized into none/low, moderate or high/alcoholic drinker). BMI was classified into four categories: 1 (underweight, BMI < 18.5), 2 (healthy weight, 18.5 ≤ BMI < 25), 3 (overweight, 25 ≤ BMI <30), and 4 (obese, BMI ≥ 30). Socioeconomic status of the individuals was measured using of the MEDEA deprivation index [23]: urban areas are represented as quintiles (i.e. from U1 to U5), where U1 is the less deprived areas and U5 is the most deprived, and rural areas (R) are differentiated [24].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients

| Characteristic | Value (n = 633 330) |

|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 425 826 (67.2) |

| Male | 207 504 (32.8) |

| Age, mean (s.d.), years | 67.3 (13.0) |

| Body mass index, mean (s.d.), kg/m2 | 29.3 (5.3) |

| NA | 541 318 |

| Body mass index by category, n (%) | |

| <18.5 | 524 (0.57) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 17791 (19.3) |

| 25–29.9 | 36998 (40.2) |

| 30+ | 36699 (39.9) |

| NA | 541 318 |

| QMEDEA deprivation index, n (%) | |

| Urban area 1 (less deprived area) | 85 843 (13.6) |

| Urban area 2 | 87 071 (13.8) |

| Urban area 3 | 90 159 (14.2) |

| Urban area 4 | 89 832 (14.2) |

| Urban area 5 (more deprived area) | 82 812 (13.1) |

| Unknown urban area | 72 498 (11.5) |

| Rural area | 124 629 (19.7) |

| NA | 486 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |

| Never smoker | 340 834 (64.8) |

| Current smoker | 79 004 (15.0) |

| Ex-smoker | 106 546 (20.2) |

| NA | 106 946 |

| Risk of alcoholism, n (%) | |

| None/low | 60 794 (61.7) |

| Moderate | 36 523 (37.1) |

| High/alcoholic | 1198 (1.2) |

| NA | 534 815 |

| Type/location of osteoarthritis, n (%) | |

| Ankle/foot | 54 (0.01) |

| Hip | 94 720 (15.0) |

| Knee | 256 687 (40.5) |

| Wrist/hand | 41 192 (6.50) |

| Generalized | 81 648 (12.9) |

| Other | 159 029 (25.1) |

QMEDEA: deprivation quintile index MEDEA, which includes urban areas from 1 (the less deprived) to 5 (the most deprived), and rural area. NA: not available.

Comorbidities

A comprehensive initial list of 58 comorbidities was informed by a literature review and by expert opinion (Table 2). The extraction of comorbidity diagnoses from individuals was performed at the time of OA diagnosis using ICD-10 codes. Comorbidities were included in the cluster model.

Table 2.

Prevalence of individual comorbidities at baseline

| Comorbidity (total = 58) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Prevalence of ⩾1% | |

| Allergy | 80 449 (12.70) |

| Anaemia | 48 281 (7.62) |

| Anxiety | 80 554 (12.70) |

| Arrythmia | 32 605 (5.15) |

| Asthma | 15 960 (2.52) |

| Back and neck pain | 212 986 (33.60) |

| Benign prostate hypertrophy | 33 560 (5.30) |

| Coronary heart disease | 34 300 (5.42) |

| Chronic heart failure | 15 850 (2.50) |

| Chronic Kidney disease | 36 098 (5.70) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 23 961 (3.78) |

| Dementia | 12 467 (1.97) |

| Depression | 48 757 (7.70) |

| Diabetes | 57 498 (9.08) |

| Eczema | 21 924 (3.46) |

| Fatigue | 16 852 (2.66) |

| Fibromyalgia | 10 008 (1.58) |

| Gall bladder stone | 21 346 (3.37) |

| Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease | 6474 (1.02) |

| Gout | 12 388 (1.96) |

| Hearing impairment | 41 563 (6.56) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 11 602 (1.83) |

| Hypertension | 14 9092 (23.5) |

| Hypothyroidism | 22 153 (3.50) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 14 810 (2.34) |

| Insomnia | 44 278 (6.99) |

| Migraine | 10 401 (1.64) |

| Obesity | 80 387 (12.70) |

| Osteoporosis | 45 261 (7.15) |

| Other vessel diseases | 9621 (1.52) |

| Psoriasis | 8179 (1.29) |

| Solid malignancy | 23 946 (3.78) |

| Stroke | 20 986 (3.31) |

| Substance abuse | 40 423 (6.38) |

| Vitamin D deficiency | 7569 (1.20) |

| Prevalence of <1% | |

| AS | 550 (0.09) |

| Autism | 24 (0.00) |

| Cataracts | 0 (0) |

| Epilepsy | 2671 (0.42) |

| Hepatitis | 455 (0.07) |

| HIV/AIDs | 252 (0.04) |

| Hyperthyroidism | 4789 (0.76) |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 4520 (0.71) |

| Leukaemia | 915 (0.14) |

| Liver | 2336 (0.37) |

| Lymphoma | 948 (0.15) |

| Multiple sclerosis | 248 (0.04) |

| Parkinson | 3872 (0.61) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 2773 (0.44) |

| PMR | 3408 (0.54) |

| PsA | 580 (0.09) |

| RA | 3250 (0.51) |

| Schizophrenia | 985 (0.16) |

| Sinusitis | 2675 (0.42) |

| SS | 2070 (0.33) |

| SLE | 504 (0.08) |

| Thrombotic diseases | 823 (0.13) |

| Tuberculosis | 1321 (0.21) |

Comorbidities with a prevalence of <1% were excluded from final cluster analyses.

Statistical methods

The external characteristics of participants and the prevalence of each comorbidity were described at the index date. Comorbidities found in <1% of the study population were excluded: their inclusion in the cluster algorithms increases the running times and the sample noise rather than driving to specific cluster solutions. Individuals were then classified into different clusters using k-means and latent class analysis (LCA) algorithms.

k-means is a type of ‘hard’ clustering approach, where individuals can only belong to one group in a binary fashion [25, 26]. In order to identify the optimal number of clusters (k), we used internal and external criteria to evaluate the clusters: internally, using within-cluster sum of squares (WCSS) and externally, by validating the clusters based on the external characteristics of the participants within each cluster. We selected the three cluster solutions from the WCSS before their change became lower than ±1 s.d. (compared with the prior value); and then we explored them by assessing the prevalence of the comorbidities in each of the clusters and the external variables.

In contrast to ‘hard’ clustering approaches, ‘soft’ approaches such as LCA [27, 28] yield the probability of an individual belonging to a particular group/cluster. To identify the potential optimal k, we compared the performance of the models from k = 1 to k = 10, using a number of metrics: entropy of the R-squared [29, 30], goodness of fit tests [31–33], and log-likelihood ratio. Participants were assigned to the cluster with the higher posterior probability and then internally and externally validated using the same strategy as k-means, except for the initial selection of k clusters, which in this case depended on the lack of change (>±1 s.d.) of entropy and goodness of fit tests and likelihood values. For an easier understanding of the results, both k-means and LCA resulting clusters were assigned to a tag/identifier that clinically represents the grouped patients.

To calculate the 10-year mortality risk for each cluster, we performed survival analysis [34] and plotted the unadjusted curve of mortality in each cluster through a Kaplan–Meier graph. Hazard ratios (HRs) were estimated through Cox regression. The assumption of proportional hazards was verified. We report the HRs with 95% CI, both unadjusted and adjusted for age and sex. All statistical analyses were conducted using R 4.1.1 for Windows (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Ethics statement

In this study, all participants’ records were previously collected and anonymized by SIDIAP. Thus, no direct participant recruitment was done.

Results

A total of 633 330 patients were identified with a diagnosis of OA between 1 January 2006 and 31 June 2020. Our cohort was predominantly female (67.2%), with a mean age of 67.3 years. A large proportion of participants were either overweight (40.2%) or obese (39.9%). The baseline characteristics of the cohort is given in Table 1.

After exclusion of comorbidities with a prevalence of <1% (Table 2), a total of 35 comorbidities were included in the cluster analysis. The most common comorbidities were back/neck pain (33.6%) and hypertension (23.5%).

Clustering by k-means

Internal clustering criteria evaluation using WCSS showed that the largest reduction of the within-clusters distance occur up to k = 4, and solutions initially selected as potentially optimal were k = 4, k = 5 and k = 6 (representative of the number of groups that participants could be clustered into, i.e. 4-cluster, 5-cluster and 6-cluster solutions, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. S1A, available at Rheumatology online). However, no significant improvement was observed in 5- and 6- cluster solutions after assessing the distribution of comorbidity patterns within each cluster solution and the external variables. Thus, the 4-cluster solution was selected as the best k-means solution (Table 3).

Table 3.

Survival analysis for 10-year mortality in 4-cluster solutions of k-means and latent class analysis

| Cluster number | Cluster name | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (A) k-means | |||

| 3 | Low-morbidity | Ref. | Ref. |

| 1 | Back and neck pain | 0.72 (0.70, 0.73) | 0.93 (0.91, 0.95) |

| 4 | Mental health | 0.87 (0.84, 0.89) | 1.21 (1.18, 1.24) |

| 2 | Metabolic syndrome | 1.62 (1.60, 1.65) | 1.18 (1.16, 1.20) |

| — | Age | — | 1.14 (1.14, 1.14) |

| — | Sex (male) | — | 1.73 (1.71, 1.76) |

| (B) Latent class analysis | |||

| 3 | Low-morbidity | Ref. | Ref. |

| 2 | ‘Back and neck pain’ plus ‘mental health’ | 0.85 (0.83, 0.87) | 1.12 (1.09, 1.15) |

| 4 | Metabolic syndrome | 1.70 (1.67, 1.74) | 1.24 (1.22, 1.27) |

| 2 | Multimorbidity | 5.71 (5.61, 5.81) | 2.19 (2.15, 2.23) |

| — | Age | — | 1.13 (1.13, 1.13) |

| — | Sex (male) | — | 1.68 (1.66, 1.70) |

HR: hazard ratio; Ref.: reference group.

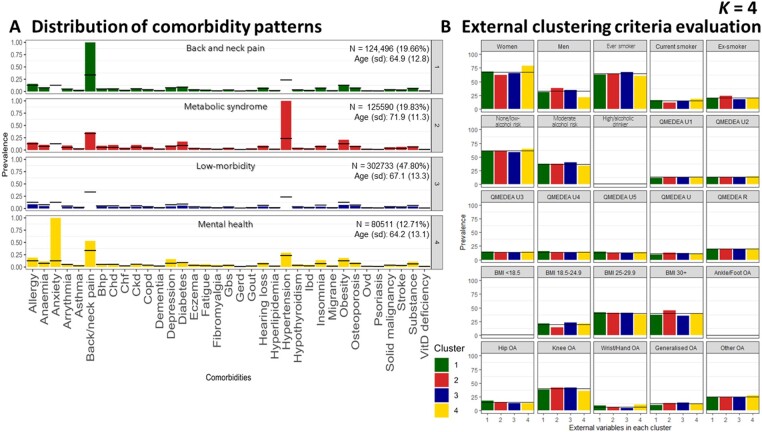

For k = 4, the distribution of comorbidity patterns led to identification of the following clusters (ordered from the largest to the lowest size): ‘low-morbidity’ (n = 302 733, 47.8%), ‘metabolic syndrome’ (n = 125 590,19.8%), ‘back and neck pain’ (n = 124 496, 19.7%) and ‘mental health’ (n = 80 511, 12.7%) (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

k-means cluster solution 4. Distribution of comorbidity patterns (A) and External clustering criteria evaluation (B). Substance: substance abuse; QMEDEA: deprivation quintile index MEDEA where U is urban area (U1 is the less deprived and U5 the most) and R is rural area. BHP: benign prostate hypertrophy; CHD: coronary heart disease; CKD: chronic kidney disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GBS: gall bladder stone; GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; OVD: other vessel diseases

The cluster labelled as ‘low-morbidity’ was defined as including individuals with a lower prevalence of other comorbidities compared with the general OA population. In contrast, the cluster label ‘multimorbidity’ refers to the cluster of individuals with a higher prevalence of all the listed comorbidities compared with the general OA population. The cluster of ‘metabolic syndrome’ was characterized by the presence of hypertension in all individuals, plus above average prevalence of obesity and diabetes. This group presented a higher ratio of males (37.80%) and obese individuals (44.9% had BMI ≥30) (Fig. 1B). The ‘back and neck pain’ cluster was characterized by the 100% prevalence of this condition in all the cluster members. The ‘mental health’ label was assigned due to a significant proportion of anxiety and depression, notably all participants with anxiety were classified into this cluster. In addition, the ‘mental health’ group had the highest ratio of females (78.60%). Supplementary Figs S2 and S3 (available at Rheumatology online) display the 5- and 6-cluster solutions, respectively.

Clustering by LCA

After clustering by LCA, internal clustering criteria evaluation (Supplementary Fig. S1B, available at Rheumatology online) using ABIC, BIC, CAIC and the likelihood ratio did not show a statistically optimal model. However, the decline ratio of the different parameters allowed us to exclude the cluster solutions equal to or higher than k = 6, since those did not improve model fit substantively. Evaluation of the mean posterior probability values showed better discrimination for 4-cluster than 5-cluster models (Supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online). Hence, we selected the 4-cluster solution as our preferred model.

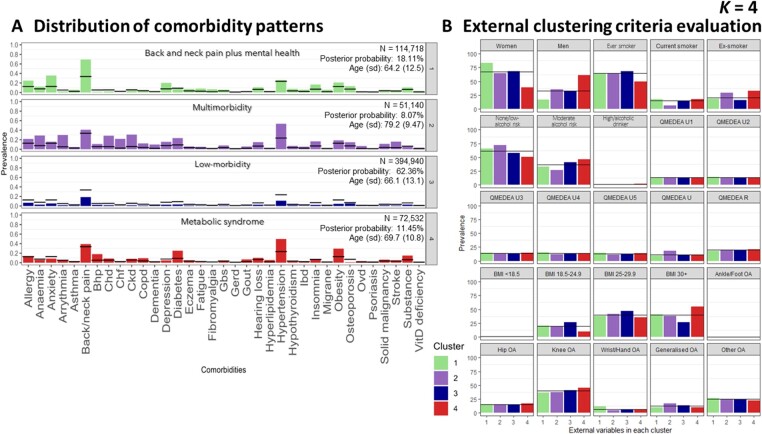

When k = 4, we identified the following clusters: ‘back and neck pain plus mental health’, ‘multimorbidity’, ‘low-morbidity’ and ‘metabolic syndrome’. Again, ‘low-morbidity’ refers to individuals with a lower prevalence of other comorbidities and ‘multimorbidity’ refers to individuals with a higher prevalence of all the listed comorbidities, compared with the general OA population.

The cluster with the highest proportion of participants was the ‘heathier’ (n = 394 940, 62.36%), followed by ‘back and neck pain plus mental health’ (n = 114 718, 18.11%), ‘metabolic syndrome’ (n = 72 532, 11.45%) and ‘multimorbidity’ (n = 51 140, 8.07%). While our overall cohort was predominantly female (67.20%), females only made up 39.00% of the ‘metabolic syndrome’ cluster, which had the highest proportion of men. Conversely, the ‘back and neck pain plus mental health’ cluster had a remarkable proportion of women (83.30%) and the youngest population (mean age 64.2 [s.d. 12.5] years). In contrast, the ‘multimorbidity’ cluster had the oldest population (mean age 79.20 [s.d. 9.47] years) (Fig. 2). Supplementary Figs S4 and S5 (available at Rheumatology online) report the 5- and 6-cluster solutions, respectively.

Figure 2.

Latent class analysis cluster solution 4. Distribution of comorbidity patterns (A) and external clustering criteria evaluation (B). Cluster colours are consistent in both sub-plots. Substance: substance abuse; QMEDEA: deprivation quintile index MEDEA where U is urban area (U1 is the less deprived and U5 the most), and R is rural area. BHP: benign prostate hypertrophy; CHD: coronary heart disease; CKD: chronic kidney disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GBS: gall bladder stone; GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; OVD: other vessel diseases

Survival analyses

OA patients were followed up a median of 6.75 years [interquartile range: 3.47–10.33]. Most of the clusters identified by k-means and LCA when k = 4 had >50% of individuals alive at 10 years. Individuals identified in the ‘multimorbidity’ by LCA had a median time to death of 7.15 years [95% CI: 7.06, 7.25]. Survival curves for 10-year mortality between the 4-clusters identified using k-means and LCA are reported in Supplementary Figs S7 and S8, respectively (available at Rheumatology online). Survival analyses for 10-year mortality (HR, 95% CI adjusted for sex and age) revealed differences between the 4-clusters in k-means (Table 3A) and LCA (Table 3B). The ‘low-morbidity’ cluster was used as the reference group in both analyses.

For k-means, the ‘back and neck pain’ cluster had a reduced risk of 10-year mortality (adjusted HR 0.93 [95% CI: 0.91, 0.95]), while the ‘mental health’ (adjusted HR 1.21 [95% CI: 1.18, 1.24]) and ‘metabolic syndrome’ (adjusted HR 1.18 [95% CI: 1.16, 1.20]) clusters had an increased risk.

In our LCA results, all clusters, including ‘back and neck pain plus mental health’ (adjusted HR 1.12 [95% CI: 1.09, 1.15]), ‘metabolic syndrome’ (adjusted HR 1.24 [95% CI: 1.22, 1.27]) and ‘multimorbidity’ (adjusted HR 2.19 [95% CI: 2.15, 2.23]), had increased risk of mortality.

Supplementary Table S2 and S3, available at Rheumatology online, report the survival analysis for 5- and 6-cluster solutions in k-means and LCA, respectively.

Discussion

Our study of 633 330 individuals with OA from the SIDIAP database is, to our knowledge, the largest to date exploring the clustering of comorbidities among individuals with a diagnosis of OA. We found that individuals with OA can be clustered based on their comorbidity patterns into groups with significantly different risks of 10-year mortality.

While we explored clustering using two separate methods, and three different cluster solutions in each of them, a number of patterns emerged: in all solutions the larger group was the ‘low-morbidity’ cluster, where patients with a new diagnosis of OA had the lowest prevalence of comorbid conditions; the ‘back and neck pain plus mental health’ groups tended to have the highest proportion of females; those designated as ‘metabolic syndrome’ groups had the highest proportion of males and the highest BMI; and the ‘multimorbidity’ groups had high mean age. While age and sex varied between groups, socioeconomic status remained relatively stable. Nonetheless, the preferred solution for both clustering methods was the 4-cluster.

When k-means and LCA 4-cluster results are compared, k-means differentiates individuals who had back and neck pain from those who had mental health comorbidities and does not show the ‘multimorbidity’ cluster unless we include one more group (i.e. k = 5). Soft classification of LCA allows higher flexibility to detect more complex patterns using a smaller number of clusters (i.e. k = 4), such as the interaction between back and neck pain along with mental health comorbidities, or the ‘multimorbidity’ cluster. Thus, clusters obtained by LCA better represented the behaviour and interaction within the different comorbidities (i.e. the comorbidity patterns). In addition, differences in 10-year mortality were most marked in the outgoing clusters from the LCA analyses, which may therefore be of more use when risk-stratifying patients in clinical practice.

With the caveat that more studies using different populations may shed further light on an optimal clustering solution in the future, we propose the 4-clusters identified by the LCA algorithm: ‘low-morbidity’, ‘back/neck pain plus mental health’, ‘metabolic syndrome’ and ‘multimorbidity’. Baseline characterization of individuals diagnosed with OA may offer clinicians the opportunity to assess potential concordance within the derived groups with regards to their comorbidities.

Comparison with other literature and interpretation

A number of general patterns of multimorbidity have previously been established. Systematic reviews have identified ‘mental health’, ‘cardiovascular/metabolic’ and ‘musculoskeletal’ as common clusters of comorbid conditions [35, 36], and have found that OA with cardiovascular and/or metabolic disease is a common multimorbidity profile presenting in primary care [37]. Despite our study focusing specifically on patients with OA diagnoses, rather than the wider population, we nevertheless observed these established clusters of comorbidities in most of our analyses.

The association between cardiovascular disease and OA is established [38, 39], but whether they simply co-exist or share a common aetiology, perhaps due to age-related, inflammatory, hormonal or drug-related mechanisms, remains unclear [40]. Metabolic syndrome, classically characterized by both obesity and diabetes, is a risk factor for the development of OA through metabolic changes that affect joint function [41]. The level of obesity is also associated with the clinical severity of the disease [42], and management guidelines therefore frequently recommend physical activity and weight loss as first-line treatment strategies in an effort to halt or slow the progression of the disease [43]. The association between musculoskeletal (especially back and neck) pain and mental health is also established [44] and studies have shown that this link can commence early in life [45], which may contribute to our observation that our ‘back and neck pain with mental health’ have low mean ages.

A previous study used LCA to cluster 221 807 OA patients from the UK into five groups [19]. The five groups identified were ‘low-morbidity’, ‘cardiovascular’, ‘musculoskeletal and mental health’, ‘cardiovascular and mental health’ and ‘metabolic’, which, despite differences in the specific comorbidities used for analysis, reflect our own LCA k = 5 results.

Several systematic reviews have explored links between OA and mortality with varied results, likely due to underlying methodological differences between them [46–48]. In order to address some of the issues intrinsic to meta-analyses and shed further light on mortality risk in OA, a recent study used large-scale individual patient-level data from six geographically diverse cohorts and found that patients with OA-related pain, or pain and radiographic OA, had between a 35% and 37% increased association with reduced time to death when compared with people without OA [49]. Our data revealed that among patients with OA, their 10-year mortality risk may vary widely depending on their particular comorbidities. The largest difference seen, when compared with patients with OA who were otherwise ‘low-morbidity’, was among our ‘multimorbidity’ groups, who in some cases had almost three times the risk of 10-year mortality.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Our study has several strengths. Firstly, we used a large established database that gathers information from >80% of its target population, allowing us to extract baseline characteristics as well as information surrounding diagnoses from a large number of participants. Secondly, our exploration of different clustering methods has allowed us to assess a variety of potential clustering results for translational potential and clinical utility. Our approach to internal and external criteria evaluation, as well as assessment of mortality risk, helps to improve both the reliability and the usefulness of our findings.

Our study also has limitations. Despite the inclusion of a large number of participants, we cannot be sure that our findings are generalizable to populations in other geographic regions. Secondly, the diagnosis of OA in primary care is predominantly clinical (i.e. there is no requirement for radiographic confirmation) [43], so there is a lack of validation of individual OA diagnoses. However, we attempted to partially mitigate this by excluding participants who had other soft tissue or bone related pathology. Furthermore, the recording of knee and hip OA within SIDIAP has previously been validated, both through comparison with self-reported physician diagnosed OA [50] and through the analysis of free text records [51]. Potential differences in clusters of comorbidities across site-specific OA were not explored. Despite not capturing site-specific patterns, our approach has the benefit of finding patterns that are independent of the joint affected and has the advantage of minimizing risk of type error 2. On the other hand, this analysis focuses on identifying different profiles of OA patients at the time of OA diagnosis, so we cannot ignore the possibility that we may be observing different stages of OA, where low morbidity would represent an earlier stage of the diseases and multimorbidity the other end of the spectrum. Changes in comorbidity patterns and cluster membership in individuals diagnosed with OA over time are plausible. To unravel this, further work analysing patients’ trajectories is necessary.

Conclusions

The comorbidity clusters we established in our study for patients with a new diagnosis of OA reflect established multimorbidity patterns and are similar to those reported in a previous study using a different patient population. Such classification of patients may in the future be useful to help guide specific treatment strategies for particular groups of patients, to address both their OA and their other comorbidities, and may help identify ‘high-risk’ patients who require more intense input from healthcare providers. Furthermore, clustering may provide insight into shared underlying pathophysiological mechanisms between different comorbid conditions. There is a need to further validate our results in other patient cohorts, as well as for research to investigate the underlying pathological mechanisms that may link the comorbidities we see in our clusters, and trials to determine the optimal treatment strategies for different groups of patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Patient Research Participants (PRP) members Jenny Cockshull, Stevie Vanhegan, and Irene Pitsillidou for their involvement since the beginning of the project. We would like to thank the FOREUM for financially supporting the research.

Contributor Information

Marta Pineda-Moncusí, Centre for Statistics in Medicine, Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences (NDORMS), University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Francesco Dernie, Centre for Statistics in Medicine, Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences (NDORMS), University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Andrea Dell’Isola, Clinical Epidemiology Unit, Department of Clinical Sciences Lund, Orthopedics, Lund University, Lund, Sweden.

Anne Kamps, Department of General Practice, Erasmus MC University Medical Center Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Jos Runhaar, Department of General Practice, Erasmus MC University Medical Center Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Subhashisa Swain, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Weiya Zhang, Academic Rheumatology, School of Medicine, University of Nottingham, UK; Pain Centre Versus Arthritis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK.

Martin Englund, Clinical Epidemiology Unit, Department of Clinical Sciences Lund, Orthopedics, Lund University, Lund, Sweden.

Irene Pitsillidou, EULAR Patient Research Partner (PRP), Executive Secretary of Cyprus League Against Rheumatism, Nicosia, Cyprus.

Victoria Y Strauss, Centre for Statistics in Medicine, Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences (NDORMS), University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Danielle E Robinson, Centre for Statistics in Medicine, Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences (NDORMS), University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Daniel Prieto-Alhambra, Centre for Statistics in Medicine, Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences (NDORMS), University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Sara Khalid, Centre for Statistics in Medicine, Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences (NDORMS), University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Rheumatology online.

Data availability

Data that support the findings of this study were provided by SIDIAP database by permission: availability of data is subject to protocol approval by SIDIAP’s Scientific Committee and Clinical Research Ethics Committee of IDIAPJGol. Data access is limited to researchers from public institutions, and collaboration with private organizations is only allowed for studies required by a regulatory agency or for non-commercial studies within a European project financed by the European Commission. Data will be shared on request to the corresponding author with permission of SIDIAP’s Scientific Committee and Clinical Research Ethics Committee of IDIAPJ Gol.

Funding

This research was funded by the Foundation for Research in Rheumatology (FOREUM) grant (2019–2022).

Disclosure statement: D.P.-A. receives funding from the UK National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) in the form of a senior research fellowship and from the Oxford NIHR Biomedical Research Centre. D.P.-A.’s research group has received research grants from the European Medicines Agency; the Innovative Medicines Initiative; and Amgen, Chiesi, and UCB Biopharma; and consultancy or speaker fees from Astellas, Amgen, AstraZeneca, and UCB Biopharma. A.K.’s Institute received/receives FOREUM grant for the contributions of the (co)authors of this institution to the entire project. J.R. and S.S.’s research group receives FOREUM research grant. W.Z. received European Foundation of Research for Rheumatology FOREUM grant to support the project, NIHR-BRC Centre for infrastructure support and Pain Centre Versus Arthritis centre grant for infrastructure support and also received consulting fees from Eli Lily and Regeneration in the form of advisory board, speakers fees from Harbin Rheumatology, and Shenzhen Rheumatology and Infection Summit and also received payment/honoraria for lectures, presentation, manuscript writing/educational events. V.S. is a full-time employee in Boehringer-Ingelheim since February 2022 and receives payment from Pfizer for lectures. S.K. receives grant from Health Data Research UK, the Alan Turing Institute and Amgen BioPharma. A.D., I.P., D.R., M.P.M., F.D. and M.E. have nothing to declare.

References

- 1. Hunter DJ, Bierma-Zeinstra S.. Osteoarthritis. Lancet 2019;393:1745–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martel-Pelletier J, Barr AJ, Cicuttini FM. et al. Osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016;2:16072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Swain S, Sarmanova A, Coupland C, Doherty M, Zhang W.. Comorbidities in osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2020;72:991–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Swain S, Coupland C, Mallen C. et al. Temporal relationship between osteoarthritis and comorbidities: a combined case control and cohort study in the UK primary care setting. Rheumatology 2021;60:4327–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boyd CM, Fortin M.. Future of multimorbidity research: how should understanding of multimorbidity inform health system design? Public Health Rev 2010;32:451–74. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zemedikun DT, Gray LJ, Khunti K, Davies MJ, Dhalwani NN.. Patterns of multimorbidity in middle-aged and older adults: an analysis of the UK Biobank data. Mayo Clinic Proc 2018;93:857–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M. et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012;380:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cassell A, Edwards D, Harshfield A. et al. The epidemiology of multimorbidity in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 2018;68:e245–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Soley-Bori M, Ashworth M, Bisquera A. et al. Impact of multimorbidity on healthcare costs and utilisation: a systematic review of the UK literature. Br J Gen Pract 2021;71:e39–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Whitty CJM, MacEwen C, Goddard A. et al. Rising to the challenge of multimorbidity. BMJ 2020;368:l6964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Guthrie B, Payne K, Alderson P, McMurdo MET, Mercer SW.. Adapting clinical guidelines to take account of multimorbidity. BMJ 2012;345:e6341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chudasama YV, Khunti K, Davies MJ.. Clustering of comorbidities. Future Healthcare J 2021;8:e224–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Magnan EM, Palta M, Johnson HM. et al. The impact of a patient's concordant and discordant chronic conditions on diabetes care quality measures. J Diabetes Complications 2015;29:288–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maher RL, Hanlon J, Hajjar ER.. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2014;13:57–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Duffield SJ, Ellis BM, Goodson N. et al. The contribution of musculoskeletal disorders in multimorbidity: implications for practice and policy. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2017;31:129–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Simões D, Araújo FA, Monjardino T. et al. The population impact of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases in relation to other non-communicable disorders: comparing two estimation approaches. Rheumatol Int 2018;38:905–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Collerton J, Jagger C, Yadegarfar ME. et al. Deconstructing complex multimorbidity in the very old: findings from the Newcastle 85+ study. BioMed Res Int 2016;2016:8745670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Muckelt PE, Roos EM, Stokes M. et al. Comorbidities and their link with individual health status: a cross-sectional analysis of 23,892 people with knee and hip osteoarthritis from primary care. J Comorb 2020;10:2235042X20920456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Swain S, Coupland C, Strauss V. et al. Clustering of comorbidities and associated outcomes in people with osteoarthritis – a UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2022;30:702–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. García-Gil Mdel M, Hermosilla E, Prieto-Alhambra D. et al. Construction and validation of a scoring system for the selection of high-quality data in a Spanish population primary care database (SIDIAP). Inform Prim Care 2011;19:135–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Recalde M, Rodriguez C, Burn E. et al. Data Resource Profile: the information system for research in primary care (SIDIAP). Int J Epidemiol 2022;51:e324–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Swain S, Kamps A, Runhaar J. et al. Comorbidities in osteoarthritis (ComOA): a combined cross-sectional, case–control and cohort study using large electronic health records in four European countries. BMJ Open 2022;12:e052816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dominguez-Berjon MF, Borrell C, Cano-Serral G. et al. [Constructing a deprivation index based on census data in large Spanish cities (the MEDEA project)]. Gac Sanit 2008;22:179–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nolasco A, Moncho J, Quesada JA. et al. Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in preventable mortality in urban areas of 33 Spanish cities, 1996–2007 (MEDEA project). Int J Equity Health 2015;14:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pinedo-Villanueva R, Khalid S, Wylde V. et al. Identifying individuals with chronic pain after knee replacement: a population-cohort, cluster-analysis of Oxford knee scores in 128,145 patients from the English National Health Service. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2018;19:354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Khalid S, Prieto-Alhambra D.. Machine learning for feature selection and cluster analysis in drug utilisation research. Curr Epidemiol Rep 2019;6:364–72. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Naldi L, Cazzaniga S.. Research techniques made simple: latent class analysis. J Invest Dermatol 2020;140:1676–80.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lanza ST, Rhoades BL.. Latent class analysis: an alternative perspective on subgroup analysis in prevention and treatment. Prev Sci 2013;14:157–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Celeux G, Soromenho G.. An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. J Classif 1996;13:195–212. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Boeschoten L, Oberski D, de Waal T.. Estimating classification errors under edit restrictions in composite survey-register data using Multiple Imputation Latent Class Modelling (MILC). J Offic Stat 2017;33:921–62. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bozdogan H. Model selection and Akaike's information criterion (AIC): the general theory and its analytical extensions. Psychometrika 1987;52:345–70. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gideon S. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat 1978;6:461–4. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sclove SL. Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika 1987;52:333–43. [Google Scholar]

- 34. George B, Seals S, Aban I.. Survival analysis and regression models. J Nucl Cardiol 2014;21:686–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Busija L, Lim K, Szoeke C, Sanders KM, McCabe MP.. Do replicable profiles of multimorbidity exist? Systematic review and synthesis. Eur J Epidemiol 2019;34:1025–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Prados-Torres A, Calderón-Larrañaga A, Hancco-Saavedra J, Poblador-Plou B, van den Akker M.. Multimorbidity patterns: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:254–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Violan C, Foguet-Boreu Q, Flores-Mateo G. et al. Prevalence, determinants and patterns of multimorbidity in primary care: a systematic review of observational studies. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e102149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang H, Bai J, He B, Hu X, Liu D.. Osteoarthritis and the risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Sci Rep 2016;6:39672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hall AJ, Stubbs B, Mamas MA, Myint PK, Smith TO.. Association between osteoarthritis and cardiovascular disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prevent Cardiol 2016;23:938–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fernandes GS, Valdes AM.. Cardiovascular disease and osteoarthritis: common pathways and patient outcomes. Eur J Clin Invest 2015;45:405–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Courties A, Sellam J, Berenbaum F.. Metabolic syndrome-associated osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2017;29:214–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Raud B, Gay C, Guiguet-Auclair C. et al. Level of obesity is directly associated with the clinical and functional consequences of knee osteoarthritis. Sci Rep 2020;10:3601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Osteoarthritis: care and management. Clinical Guideline CG177. London: NICE. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg177 (11 may 2022, date last accessed).

- 44. Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Lee S. et al. Mental disorders among persons with chronic back or neck pain: results from the World Mental Health Surveys. Pain 2007;129:332–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rees CS, Smith AJ, O'Sullivan PB, Kendall GE, Straker LM.. Back and neck pain are related to mental health problems in adolescence. BMC Public Health 2011;11:382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xing D, Xu Y, Liu Q. et al. Osteoarthritis and all-cause mortality in worldwide populations: grading the evidence from a meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2016;6:24393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Veronese N, Cereda E, Maggi S. et al. Osteoarthritis and mortality: a prospective cohort study and systematic review with meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016;46:160–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Han X, Liu Z, Kong L, Wang L, Shen Y.. Association between osteoarthritis and mortality: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med 2017;10:1094–110. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Leyland KM, Gates LS, Sanchez-Santos MT. et al. ; PCCOA Steering Committee. Knee osteoarthritis and time-to all-cause mortality in six community-based cohorts: an international meta-analysis of individual participant-level data. Aging Clin Exp Res 2021;33:529–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Prieto-Alhambra D, Nogues X, Javaid MK. et al. An increased rate of falling leads to a rise in fracture risk in postmenopausal women with self-reported osteoarthritis: a prospective multinational cohort study (GLOW). Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:911–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Prieto-Alhambra D, Judge A, Javaid MK. et al. Incidence and risk factors for clinically diagnosed knee, hip and hand osteoarthritis: influences of age, gender and osteoarthritis affecting other joints. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1659–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data that support the findings of this study were provided by SIDIAP database by permission: availability of data is subject to protocol approval by SIDIAP’s Scientific Committee and Clinical Research Ethics Committee of IDIAPJGol. Data access is limited to researchers from public institutions, and collaboration with private organizations is only allowed for studies required by a regulatory agency or for non-commercial studies within a European project financed by the European Commission. Data will be shared on request to the corresponding author with permission of SIDIAP’s Scientific Committee and Clinical Research Ethics Committee of IDIAPJ Gol.