Abstract

Introduction

There is little research on the triage of patients who are not yet in cardiac arrest when the emergency call is initiated, but who deteriorate and suffer a cardiac arrest during the prehospital phase of care. The aim of this study was to investigate Emergency Operation Centre staff views on ways to improve the early identification of patients who are at imminent risk of cardiac arrest, and the barriers to achieving this.

Methods

A qualitative interview and focus group study was conducted in two large Emergency Medical Services in England, United Kingdom. Twelve semi-structured interviews and one focus group were completed with Emergency Operations Centre staff. Data were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis.

Results

Three main themes were identified: The dispatch protocol and call-taker audit; Identifying and responding to deteriorating patients; Education, knowledge and skills. Barriers to recognising patients at imminent risk of cardiac arrest include a restrictive dispatch protocol, limited opportunity to monitor a patient, compliance auditing and inadequate education. Clinician support is not always optimal, and a lack of patient outcome feedback restricts dispatcher learning and development. Suggested remedies include improvements in training and education (call-takers and the public), software, clinical support and patient outcome feedback.

Conclusions

Emergency Operation Centre staff identified a multitude of ways to improve the identification of patients who are at imminent risk of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during the Emergency Medical Service call. Suggested areas for improvement include education, triage software, clinical support redesign and patient outcome feedback.

Keywords: Emergency medical service, Emergency Medical Dispatch, Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

Introduction

Emergency Medical Services (EMS) triage emergency calls to allocate healthcare resources appropriately. EMS triage is based on the severity and urgency of health care need.1 In England (UK), patients who are identified during the EMS call as having suffered an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA), and those who are critically unwell and at imminent risk of OHCA, should always be allocated the fastest ambulance response (Category 1; target response time 7 minutes).2

Studies indicate that EMS call triage may trigger a suboptimal response to some patients with life threatening conditions.3 Triage of emergency calls is an important element of the “Chain of Survival” in OHCA and in the recognition of deteriorating patients.4 Our previous research has indicated that patients who are not yet in OHCA when the EMS call is initiated, but who deteriorate and suffer an OHCA during the prehospital phase of care receive a lower priority response and as a result have significantly longer EMS response times. These patients often present to EMS with cardiac symptoms and difficulties in breathing.

There has been little research on the EMS triage of this patient group.5 Previous research6 has investigated call-takers’ views on managing patients already in OHCA when the EMS call is made. Research is required to understand what enables or inhibits a call-taker to recognise the necessity for the highest priority EMS response to patients not yet in OHCA, but at imminent risk of OHCA.5 The aim of this study was to investigate Emergency Operation Centre staff views on the barriers to early identification of patients who are at imminent risk of cardiac arrest, and how to improve this.

Methods

This was a qualitative interview and focus group study. Two UK EMS (EMS 1, EMS 2) participated in this research. At the time of the study, EMS1 covered 10,000 square miles, included two Emergency Operation Centres managing around 4000 EMS calls per day. EMS2 covered 6500 square miles, included two Emergency Operation Centres and handled around 2500 EMS calls per day. In the UK, non-clinically trained call-takers based in the Emergency Operation Centre triage EMS calls using automated protocol-based call-taking. Advanced Medical Priority Dispatch System (AMPDS7) was the triage software used by both EMS participating in this study. AMPDS licensing requires call-takers to be audited for compliance with the AMPDS script as part of a quality assurance programme8. In each participating EMS there are clinicians whose role includes supporting call-takers with call triage, where required.

Ethics

The NHS Health Research Authority approved the study, 19/HRA/4437 and University of the West of England, Bristol provided ethics committee approval, UWE REC REF No: HAS.20.05.182.

Recruitment

We aimed to recruit up to 20 participants using purposive sampling. The sample size was pre-determined based on information power for studies with a narrow aim and clearly defined participant population.9 Eligible participants were employed in the Emergency Operation Centre in one of the two participating EMS and had experience in managing emergency calls. The study was advertised through social media, participating EMS research teams, EMS internal advertising and key Emergency Operation Centre team members. Participants were invited to express an interest to the research team. Following an expression of interest eligible persons were sent a participant information sheet and a consent form and encouraged to ask any questions. On receipt of a signed consent form and prior to interview participants were sent a link to a short film describing our preceding work. On completion of the interviews, participants were invited to take part in an additional focus group.

Procedure

A predefined set of four overarching themes were developed from our preceding research5 (Table 1). A semi-structured interview guide based on these themes was developed by the study team (Supplementary file). Areas for exploration were identified from the interviews and used to guide the focus group discussion (Table 2).

Table 1.

Predefined overarching themes.

| Theme One | Theme Two | Theme Three | Theme Four |

|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulties adhering to the dispatch protocol | Managing hysterical callers | The assessment of clinical signs | Experiences of Call-taker education |

Table 2.

Key areas to guide interview discussion.

| Caller’s agenda/call-taker agenda – Interactional misalignment |

| The focus on breathing in Pre-Triage Questions and risk of lost information |

| How to improve the interaction |

| Call-taker intuition |

| Clinical support |

| Monitoring breathing |

KK conducted interviews and facilitated the focus group virtually via MS Teams (Microsoft Corporation, Washington, United States). Interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim and anonymised. Reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) was used to analyse the interview and focus group data.10 The main researcher (KK) recognised that their role in the process was central to the knowledge produced11 and their interpretations of the data could be different to another researcher’s interpretations.12 During the research process KK kept a reflexive diary to document any personal beliefs and judgements that may have incidentally affected the research.13

A combined deductive and inductive approach was used during the RTA.12 Data were deductively coded into themes and inductively analysed generating new themes and sub themes, using NVivo Software version 12.14 KK completed the coding and analysis and met regularly with SV to discuss the overarching narrative and organisation of themes. The deductive and inductive analyses were combined into the final overarching themes and sub themes.

The phases of reflexive thematic analysis used are detailed below10:

-

I.

Familiarisation with the data

-

II.

Generating initial codes

-

III.

Generating themes

-

IV.

Reviewing potential themes

-

V.

Defining and naming themes

-

VI.

Producing the report

Results

Twelve semi-structured interviews were completed between July and September 2021. The mean duration of the individual interviews was 54 minutes (minimum 51 minutes and maximum 66 minutes). Four participants also took part in a focus group in September 2021, lasting 67 minutes. Participant demographics are detailed in Table 3. The mean age of participants was 31 years old (range 20–59 years), and mean years of Emergency Operation Centre experience was 7 years (range 1.5–19 years).

Table 3.

Participant demographics.

| Interviews N = 12 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | Age | Years EMS Experience | Job role(s) |

| P01 (Trust 1) | 31 | 3 | Call-taker auditor |

| P02 (Trust 1) | 47 | 13 | Emergency Care Assistant, Call-taker |

| P03 (Trust 1) | 24 | 3.5 | Call-taker, Special Operations Dispatcher |

| P04 (Trust 1) | 59 | 17 | Emergency Care Assistant Ambulance Technician Paramedic Clinical MentorClinical Advisor (EoC) |

| P05 (Trust 1) | 46 | 14 | Paramedic 111 clinicianSenior Manager (Emergency Operation Centre) |

| P06 (Trust 1) | 21 | 1.5 | Call-taker |

| P07 (Trust 1) | 20 | 0.5 | Community First Responder Call-taker |

| P08 (Trust 1) | 20 | 2 | Call-takerCall-taker & Floor Walker (supervisor) |

| P09 (Trust 2) | 23 | 5 | Call-taker |

| P10 (Trust 2) | 20 | 3 | 111 Health Advisor Call-taker |

| P11 (Trust 2) | 23 | 1.5 | Call-taker Ambulance Technician |

| P12 (Trust 2) | 42 | 19 | Call-taker Team leader |

| Focus Group | P04,P08,P11,P12 | ||

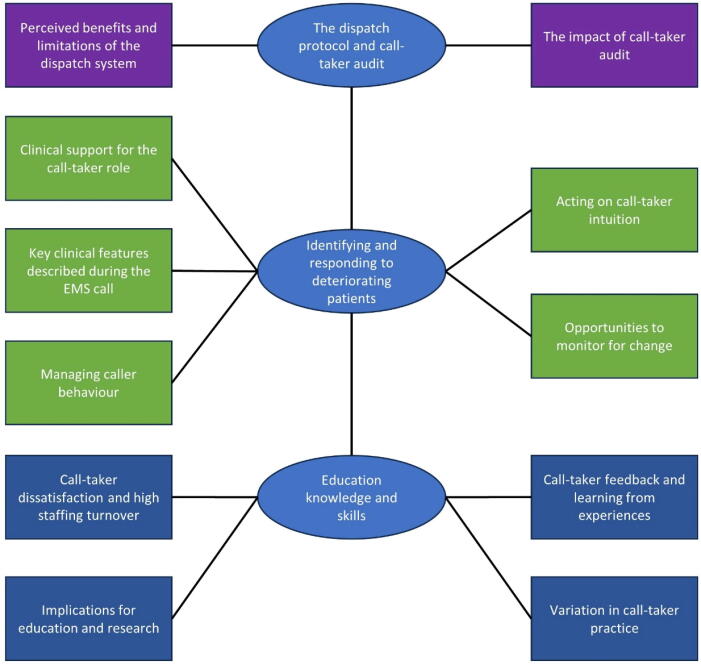

Following the interviews and focus group there was rich data and ‘information power’9 and further recruitment of participants was unnecessary. Three main themes were identified comprising: The dispatch protocol and call-taker audit; Identifying and responding to deteriorating patients; Education, knowledge and skills. Each theme consisted of sub-themes, and these are illustrated in Fig. 1 and described below. Illustrative quotes are displayed in Table 4, Table 5, Table 6.

Fig. 1.

Thematic Map.

Table 4.

Illustrative Quotes Theme One Nb quotes have been condensed for readability.

|

Theme One: The dispatch protocol and audit Sub Theme – Perceived benefits and limitations of the dispatch system | ||

|---|---|---|

| Q1 | P11 | “I think (it) (AMPDS) does a really, really good job. Sticking to it can be quite tricky because people don’t understand the instructions or the questions sometimes…”. |

| Q2 | P02 | “I don’t think there’s anybody in the control room that likes (A)MPDS because it’s so restrictive in your ability to be able to interrogate”. |

| Q3 | P08 | “…we put our faith in the PROQA system and that is very much it. You are not allowed outside the remit of PROQA. You ask the questions exactly as they are written”. |

| Q4 | P07 | “… I've had other calls as well where…if I’d been able to have a bit more freedom from the protocol, it would have made it a cat 1 so much quicker….”. |

| Q5 | P02 | “…one of the issues with (A)MPDS is it doesn’t recognise peri-arrest. They’re either in cardiac arrest, or they’re not. One … of the benefits … of my background and my clinical training is the fact that I can pick up on those red flags that say to me this person’s going to arrest very, very quickly”. |

| Q6 | P04 | “… the protocol is too robotic, and it doesn't account for what's actually happening…by stepping away, sometimes, the call taker will probably fail that audit, but they will probably… and sometimes… and evidentially, … saved a life a lot better because … they've stepped away from it”. |

| Q7 | P01 | “An experienced EMD (call-taker) knows that you've got to trust the protocol, trust the protocol as best you can, and you should stick to it. But it can be to the point of, “I don't think this is right,” like, …“I think this person needs a cat two ambulance when it's a cat three.”… you can't change that as an EMD (call-taker) …”. |

| Q8 | P08 | “However there are definitely situations where as EMDs (call-takers) we feel they (the dispatch protocols) don’t necessarily fit the situation correctly. We don’t have a lot of scope to move around … which is why the hub has our clinicians, our paramedics, doctors and nurses to ask for further advice”. |

| Q9 | P03 | “…there are more trigger words for abnormal or ineffective breathing which … probably makes it easier now … you could get stuck at your pre-triage question for … maybe 10–15 seconds because they … haven't said the right word …”. |

|

Theme One: The dispatch protocol and audit Sub Theme – The impacts of call-taker audit | ||

| Q10 | P07 | “Did I miss something there that could have told me that patient was going to go into cardiac arrest? … no, according to (A)MPDS rules, you did everything right…”. |

| Q11 | P02 | “… your audit performance has a big impact on whether or not you can progress within the hub… Or even actually doing overtime…”. |

| Q12 | P04 | “Yeah, I think the inexperienced ones are scared to do that because they know that they will fail the audit for whatever reason. But I know the experienced ones go, hmm, meh, okay … I’m doing a deviation”. |

| Q13 | P04 | “… what they need to do is start deciding if their deviation from protocol has had the right effect… don't penalise them for stepping off the line, making a decision and a good call”. |

Table 5.

Illustrative Quotes Theme Two. Nb quotes have been condensed for readability.

|

Theme 2: Identifying and responding to deteriorating patients Sub Theme – Clinical support for the call-taker role | ||

|---|---|---|

| Q14 | P02 | “… any concerns … we’re supposed to flag to either a floor walker or a team leader first, and then ask permission if we can flag it to … a clinician… now they go into what’s called a clinical [hunt], and if one’s available they’ll answer… But quite often they’re not available… So, you’re then told put a warning on, but that doesn’t help if the patient is potentially in cardiac arrest. You’ve got a crew that’s on a category two call that’s nearby but aren’t going to get diverted because this isn’t as high a priority because it’s still a cat two as well”. |

| Q15 | P10 | “…and then it goes back to what we said earlier about having to raise somebody (get the attention of a floor walker, or supervisor), them not knowing what you mean and then having to get a clinician, and then … at least a 15 minute period there when potentially you might get a duplicate call, “Oh, yeah, patient’s not breathing now.” |

| Q16 | FGP12 | “Yeah, I think it's definitely something that we ought to look into because it is too hard for us to try and get hold… (of the) clinicians…”. |

| Q17 | FGP12 | “The difficulty is, though, I mean I don't know what it's like at ****, but … the clinicians really don't like communicating with the EMDs (call-takers). We have no direct line of communication…”. |

|

Theme 2: Identifying and responding to deteriorating patients Sub Theme – Key clinical features described during the EMS call | ||

| Q18 | P07 | “…the biggest thing that comes to mind is the ineffective breathing problem (patients contacting EMS with difficulty breathing that then proceed to OHCA and the difficulty assessing ineffective breathing), … that's the call that I've always had go to a cardiac arrest…the most common thing that changes, is ineffective breathing goes to unconscious and that's CPR”. |

| Q19 | P09 | “…when someone's agonal breathing they really do tell you, … he's had this God-awful noises, it's something that they will bring up, not something that you have to ask of them”. |

| Q20 | P08 | “…so assessing breathing for us is probably one of the biggest challenges there are, as EMDs (call-takers). It’s one of the hardest things”. |

| Q21 | P02 | “If they’re predominantly conscious and keep passing out, they’re awake…. If they’re predominantly unconscious and wake up occasionally before passing out again, I just leave it unconscious…”. |

| Q22 | P04 | “…unconscious isn't always dangerous unless it's blocking an airway. So people faint”. |

| Q23 | P02 | “quite often a patient that’s going into cardiac arrest, the caller will give a description of a colour change. “He’s not conscious, he’s barely breathing, and he’s going blue.” |

|

Theme 2: Identifying and responding to deteriorating patients Sub Theme – Acting on call-taker intuition | ||

| Q24 | P06 | “We all seem to have gut feelings of when things don’t quite sit right… a caller will say something and it’s just like, that’s not quite right. So then you have to seek clinician advice for it”. |

| Q25 | P08 | “…I said earlier, when you can hear the little catch in the back of someone’s throat when they’re explaining something to you that makes you feel like the person is very scared”. |

| Q26 | P09 | “…it's like this gut instinct that you get, which is a bit difficult to try and like get everyone to get on the same page”. |

|

Theme 2: Identifying and responding to deteriorating patients Sub Theme – Opportunities to monitor for change | ||

| Q27 | P05 | “So if you're looking at someone's conscious level gradually deteriorating, or the respiratory effort going down, it's things like that that the system isn't very well set up for”. |

| Q28 | P06 | “I tend to use … unconscious protocol when you’re dealing with an unconscious patient. And one of the instructions is, “Look at them very carefully and tell me exactly what you see and hear them doing.” So I tend to use that even if I’m not in that part of the protocol, just to see what they’re going to say. Because sometimes they’ll say something and you’re a bit like, “I need more information there.” But you can’t ask for it. So I tend to use that, because it is scripted somewhere else.” |

| Q29 | P11 | “once you’ve coded the call, as long as there’s no instructions to be delivered but you have to stay on the line, it’s then more freelance…if you had a burning question that you needed to get in but weren’t allowed at the time, you can then get it in then in that sort of discussion at the end…” |

| Q30 | P07 | “…with a patient that's got breathing problems … Once I've gone through my instructions and before I consider putting the phone down, I’ll just check in again and be like … how is their breathing? And if at that point they go, oh well, it’s got so much worse, then okay, that's where I'm going to consider staying on the line or making a cat warning (upgrading) if that's necessary…”. |

| Q31 | FGP11 | “it's not a requirement for them (call-taker) to check in, that's a really good point, maybe it should be a requirement to check in more often or really that skill of knowing to check in more often should be taught…”. |

| Q32 | P12 | “…I try to concentrate on each call as they come through, and, regardless of whether there’s calls waiting, you know, if I need to stay on the phone for a little bit longer then… then I do…”. |

| Q33 | P12 | “…EMDs (call-takers) need to be brave enough to upgrade something to a cat. one, if they think it needs a cat. one without worry that they're going to be [complianced] (fail an audit) or that the dispatcher's going to come down on them or whatever … it's not very nice when you've been on the phone with somebody for 20 minutes and they've taken a turn for the worst and you have to cat. one it and then … they've not been able to arrive within time (target times) but at the end of the day we've got to take care of the patient we've got, so…”. |

|

Theme 2: Identifying and responding to deteriorating patients Sub Theme – Managing caller behaviour | ||

| Q34 | FGP12 | “..they want to tell you what they want to tell you, they're not always listening to the question and they sometimes panic answer. I've had quite a few that will say no, the patient's not breathing when it becomes quite clear when they tell you what the problem is that the patient is breathing or they could actually be the patient themselves”. |

| Q35 | P01 | “… how to calm that caller and how to deal with that caller is all down to you, you know?” |

Table 6.

Illustrative Quotes Theme Three. Nb quotes have been condensed for readability.

|

Theme 3: Education, knowledge and skills Sub Theme – Cal-taker dissatisfaction and high staffing turnover | ||

|---|---|---|

| Q36 | P11 | “they leave because of stress or shifts or lack of fulfilment or the job’s not been what they expected, they go elsewhere. Yeah, we have a massive turnover of staff. …So it’s scary. It means that lots of people are within the first few months or years…”. |

| Q37 | P06 | “…the ones that are good at it get experienced with it, they sort of get a bit sick of it because nothing seems to change no matter what you do. So then they end up leaving to go and do other stuff”. |

| Q38 | P11 | ”… more senior staff and management don't seem to listen to any advice that… or ideas that we might have … there's no platform for EMDs' (call-takers) thoughts …” |

|

Theme 3: Education, knowledge and skills Sub Theme – Implications for education and research | ||

| Q39 | P07 | “… like our first aid training was one day … only four weeks of training, and most of that is learning the system of how to use the computers and how to use all the different systems and protocols and everything”. |

| Q40 | P05 | “…if we can get something, if we can move to a position where we’re more intimately understand the sort of correlation between kind of red flags or red flag phrases or, you know, what are those early warning signs…” |

| Q41 | P02 | “..by the time they get to week four, I think they need to be using actual calls to triage through the system because no call is ever simple. Nobody ever phones up about one thing. It’s generally three or four things by the time they come to phoning 999. The patient’s been unwell for several weeks and their abdo… dominal pain is worse, and they’ve now got chest pain…”. |

| Q42 | P06 | “There’s no training on that at all really. They’d play you hysterical callers, but they (trainers) [never] tell you how to deal with it.” |

| Q43 | P10 | “… public awareness of what will happen on a 999 call is really important… “Okay, you’re going to get through to somebody that, you know, is quite skilled and that he’s going to be able to triage you and look after you and, you know, the help’s already started from that point.” I think public awareness of that is massively important …”. |

| Q44 | FGP12 | “I think educating people is the way forwards, really. We really ought to educate more than what we do: you know, educating people why they should be ringing 999, educating people what happens when they ring 999”. |

|

Theme 3: Education, knowledge and skills Cal-taker feedback and learning from experiences | ||

| Q45 | P07 | “So yeah, like getting the feedback on especially ones that suddenly go to arrest, I think is really important, at least so that I've got the chance to go, actually, can I listen back to that? Actually, is there something I did wrong?”. |

| Q46 | P11 | Absolutely, yeah. Yeah, it could highlight faults in AMPDS or, like I said, our allocation of categories to each code. That could highlight a problem as well”. |

|

Theme 3: Education, knowledge and skills Variation in call-taker practice | ||

| Q47 | P08 | “I feel like although you can develop communication skills, emotionally being in tune with someone, is something unfortunately some people don’t have and you can’t really, you know I think it does come into play quite a lot. I think that’s why it’s such a hard job”. |

| Q48 | P01 | “…then that's when the EMD (call-taker) has to make their first proper decision about which protocol do they then select. So this is when the knowledge or the experience or the skill of the EMD (call-taker) makes a big difference, and can make a big difference to those patients…”. |

| Q49 | P09 | “… a lot of people are just wanting to tick a box and move on and if you actually just take the time to listen and like focus on what's going on around them you might pick it up more.” |

Theme One: The dispatch protocol and audit (Table 4)

Theme one consisted of two sub themes: Perceived benefits and limitations of the dispatch system; The impacts of call-taker audit.

Perceived benefits and limitations of the dispatch system

Participants had mixed views concerning the benefits and limitations of the dispatch protocol. Some found it helpful for identifying patients who are in OHCA or at imminent risk of OHCA as detailed in Quote 1 (Q1). However, some participants expressed the opposite view (Q2) describing restrictions from the dispatch protocol on the call-taker’s capacity to triage the EMS call (Q3-Q4).

Participants discussed instances where peri-arrest would not be identified through use of the scripted dispatch protocol. Therefore, they felt a need to take further action (Q5) or deviate from the script, and fail their compliance audit, to calm the caller or obtain further information (Q6). However, some participants reported that they rely on and adhere to the dispatch protocol because they are not clinically trained (Q7). Clinical support can be accessed where call-takers are concerned that the outcome from the dispatch protocol is inadequate or inaccurate (Q8). The addition into the system of ‘trigger words’ was reported to support identification of critically unwell patients (Q9).

The impacts of call-taker audit

Call-takers are regularly audited on their protocol adherence for quality assurance. Audit is sometimes perceived as positive as it can confirm that the call-taker has followed procedure correctly (Q10). However, an individual’s performance is rated according to audit scores, and this can impact on whether they can do overtime and apply for promotion (Q11). Consequently, participants expressed that less experienced call-takers are highly focused on adhering to the dispatch protocol, whereas more experienced call-takers will deviate from the protocol where they think it is in the best interests of the patient(Q12). One participant felt that the audit process should consider whether a deviation from the scripted protocol resulted in a more appropriate outcome for the patient (Q13).

Theme Two: Identifying and responding to deteriorating patients (Table 5)

The theme ‘identifying and responding to deteriorating patients’ comprised five sub-themes: Clinical support for the call-taker role; Key clinical features described during the EMS call; Acting on call-taker intuition; Opportunities to monitor for change; Managing caller behaviour.

Clinical support for the call-taker role

Timely access to clinical support was viewed as a major issue, with call-takers reporting that there were insufficient clinicians to meet demand (Q14). Participants expressed concerns about delays in obtaining advice, the implications for patients and associated frustration caused to call-takers (Q15). Participants acknowledged that the system of accessing clinical support was inadequate as they often could not access support when required (Q16), and described a disconnect between the call-takers and the clinical support available to them (Q17).

Key clinical features described during the EMS call

Participants discussed the key clinical features described during the EMS call concerning patients that were at imminent risk of OHCA and the importance of recognising deteriorating breathing, unconsciousness and any facial colour change.

Participants cited abnormal breathing as an important indication (“red flag”) of potential OHCA (Q18). Recognition of agonal breathing was described by one participant as being straightforward (Q19). However, other participants described assessing a patient’s breathing as very challenging (Q20). Assessment of consciousness was described as difficult because consciousness can fluctuate, and the call-takers must make a judgement call on the information received (Q21). In addition, a participant stated how unconsciousness by itself might not be indicative of a seriously unwell patient (Q22). The most definitive feature described was facial colour change, which was considered binary (either there was a colour change or there was not), whereas consciousness and breathing were felt to be variable and more difficult to assess (Q23).

Acting on call-taker intuition

All participants described intuition concerning certain callers who they felt were calling about a patient at imminent risk of OHCA. The call-takers discussed not being able to clearly identify what it was about the call that triggered this intuitive feeling. Some call-takers suggested it was something about the caller’s voice that relayed how scared they were (Q24-25). One participant described how an intuition that something is not right created a challenge for the call-takers because it is difficult to articulate what they are concerned about (Q26).

Opportunities to monitor for change

Participants discussed how the AMPDS protocol is not suited to monitoring deteriorating patients; the design of the software means that questions are not usually revisited once they have been answered (Q27). Participants had experience of managing calls where the patient had deteriorated during the call, but the call-taker had not been able to ascertain that this had occurred using the dispatch protocol. One participant described navigating the system and sometimes using a breathing tool designed to be used with an unconscious patient in cases where the patient was conscious in order to support triage (Q28).

Once call-takers have completed the scripted questions in the dispatch protocol and given advice to the caller there is an option to monitor the patient (Q29). A participant described how they use this opportunity to monitor patients who have issues with their breathing (Q30). Participants suggested that changing the triage process so that call-takers must complete an element of monitoring during the scripted triage might improve recognition of patients at imminent risk of OHCA (Q31). There can be pressure for call-takers to be available to take another EMS call, a participant expressed their duty of care to the patient and the importance of monitoring when indicated, regardless of demand on the system (Q32). The same participant indicated that pressures for UK EMS to meet time targets can be a barrier to EMDs upgrading calls in circumstances where re-categorisation will shorten the time target and result in time targets being missed (Q33).

Managing caller behaviour

Callers do not always behave in a way that allows the call-taker to triage the call effectively. Participants described how callers do not expect to be asked a question about breathing immediately; they tend to persist with saying what they want to say, or mishear the opening questions (Q34). Participants also described managing emotionally distressed callers, and how they don’t always feel adequately prepared to manage callers who are distraught (Q35).

Theme Three: Education, knowledge and skills (Table 6)

Theme three comprised four sub themes: call-taker dissatisfaction and high staffing turnover; Implications for education and research; call-taker feedback and learning from experiences; Variation in call-taker practice.

Call-taker dissatisfaction and high staffing turnover

There is a high turnover of call-taker staff in the Emergency Operation Centre, and call-takers often leave the role and obtain promotion within the service or outside of EMS. Participants felt that the role didn’t reflect expectations and the result was an inexperienced workforce (Q36-Q37). Call-takers also expressed a lack of empowerment in their role. Call-takers were aware of barriers to the recognition of patients at imminent risk of OHCA, but felt that senior staff did not always listen to their views and suggestions for improvement (Q38).

Implications for education and research

Participants identified that call-taker training had a focus on IT systems. Call-takers recognised that they did not need extensive clinical training, but believed additional education concerning the clinical signs and symptoms of patients who are deteriorating and at imminent risk of OHCA would help them to identify this patient group (Q39–Q40).

Participants thought that call-taker training could be improved by listening to recordings of real-life calls. Participants discussed how callers often describe more than one condition and the call-takers must make a choice concerning which protocol to choose, which then determines the questions asked (Q41). Participants also recognised the benefits of additional communications training to help them to manage emotional callers, or those who struggled to follow the dispatch protocol (Q42).

Participants hypothesised that if the public were educated about the structure of an EMS call, callers might understand that the questions are being asked because the call-taker is crucial to the first link in the chain of survival (Q43–Q44).

Call-taker feedback and learning from experiences

A dominant finding was the call-takers’ desire for the opportunity to receive feedback on some incidents, specifically to know where a patient had gone on to suffer an OHCA after the EMS call had been disconnected to promote learning (Q45). Where patient outcomes do not reflect an appropriate category of call this information could be used to formulate a picture of how well the dispatch protocol is working and to make changes based on evidence (Q46).

Variation in call-taker practice

Participants recognised variability in call-taker performance, with some call-takers skilled at detecting nuances in the interaction that identify a patient who is very unwell (Q47). The experience of the call-taker is reflected in how they use the dispatch software to triage the patient. Call-takers will select different protocols depending on experience and this will affect triage outcomes (Q48). A participant highlighted a tendency for some call-takers to focus on the system rather than on what the caller is saying which might lead to missed opportunities to recognise a deteriorating patient (Q49).

Discussion

This research with Emergency Operation Centre staff aimed to understand the barriers to improving early identification of patients contacting EMS who are at imminent risk of cardiac arrest and identified three main themes; The dispatch protocol and call-taker audit; Identifying and responding to deteriorating patients; Education, knowledge and skills.

Theme one, ‘The dispatch protocol and call-taker audit’ identified that EMS auditing of call-taker performance in adhering to the dispatch protocol constrains call-takers and compels them to focus on protocol adherence over acting on any intuition concerning a patient’s presentation. A study that has previously explored call-taker decisions to override the dispatch system found that call-takers do not always appropriately override the dispatch protocol, and that the dispatch protocol is more accurate and consistent than the subjective intuitions of dispatch staff.15 There is a clear discrepancy between the call-taker views presented here on improving the recognition of critically unwell patients and the existing literature.

Theme two, ‘Identifying and responding to deteriorating patients’ indicated that clinical support for the call-taker role could be improved if more clinicians were available in Emergency Operation Centres, or with different models of working to allow more effective use of clinician time. Recently published research by Moller and colleagues16 recognised the requirement for teamwork between stakeholders in Emergency Medical Dispatch. Call-takers expressed how they have an intuition concerning certain patients and that explaining this to senior staff was challenging. Previous research has demonstrated that call-takers’ decision-making depends on both vocal expressions and the intensity of expression, and found that call-takers are particularly tuned in to expressions of ‘fear’ with the strongest influence on decision-making being when a case is severe.17 There is a significant evidence gap concerning emotion in EMS calls for OHCA18 which translates to those patients at imminent risk of OHCA and a better understanding of this phenomenon would be useful to inform practice.

Theme three, ‘Education, knowledge and skills’ indicated that the high staffing turnover of call-takers contributes to the loss of knowledge and skills as call-takers progress into different roles or leave to work elsewhere. In relation to call-taker retention and dissatisfaction, a systematic review in 201719 identified call-taking as a stressful job with a significant proportion of call-takers reporting negative effects on their psychological health. Research by Wennlund and colleagues20 investigated call-taker experience of managing EMS calls. The team identified a main category to be call-taker management of a multifaceted, interactive task with results useful for designing call-taker training programmes.

Teaching call-takers to recognise agonal breathing has had positive results and increased telephone cardiopulmonary resuscitation21 and there is potential to investigate simulation training and the recognition of clinical signs of deterioration in a patient who is at imminent risk of OHCA. A quality improvement programme concentrated on education, audit and a visual reminder built into the dispatch system to consider OHCA during every EMS call had positive impact.22 Riou and colleagues23 proposed that call-taker training in the interactional differences in the call could help to identify patients in OHCA and studies have noted the desire for call-takers to receive more clinical and communications training.24 Research by Gerwing and colleagues25 found that communication training could improve the call-taker and caller interaction without abandoning index-driven questioning, whilst also reducing decision-making time.

Currently call-takers do not routinely receive clinical outcome feedback and participants welcomed the opportunity to receive feedback on patients they had triaged. A lack of call-taker feedback has been reported previously26 with participants noting that the lack of feedback negatively impacted call-taker well-being. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association identified the importance of recognition and feedback to call-takers in response to OHCA,27 but again the focus appears to be on patients already in OHCA, and not the deteriorating patient at imminent risk of OHCA.

Further research is indicated to understand the most appropriate ways of educating call-takers in effective communication strategies and linguistic analysis has shown potential in enhancing understanding in this area.28 Future research should seek to understand what additional clinical education would benefit call-takers in recognising patients at imminent risk of OHCA; educate the public concerning the structure of the EMS call; investigate optimal models for clinical support for call-taker roles; investigate call-taker intuition and patient outcome feedback.

This study has provided an in-depth insight into an under-researched area of EMS and has produced new understanding and identified areas for future research. Limitations of this study are that the study was based in the UK and was limited to EMS using a single triage software system (AMPDS) and the findings of this study may not be generalisable to other EMS, triage and dispatch models.

Conclusions

Three main themes were identified: The Dispatch Protocol and Audit; Identifying and Responding to Deteriorating Patients; Education, Knowledge and Skills. Participants identified barriers to recognising patients at imminent risk of OHCA that included the restrictive dispatch protocol, lack of opportunity to monitor a patient during scripted triage, compliance auditing and inadequate clinical and communication education. Clinician support for the call-taker role was not always adequate, or timely. A high staff turnover in Emergency Operation Centre leads to inexperience as well as a focus on the system rather than the caller. Callers are unaware of the structure of the EMS call which leads to initial confusion, and a lack of patient outcome feedback restricts call-taker learning and development. Suggested improvements included further training and education (call-takers and the public), improvements in software, clinical support redesign and opportunities for patient outcome feedback.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Kim Kirby: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Sarah Voss: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Jonathan Benger: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge South Western Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust for sponsoring this research and for both South Western Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust and East Midlands Ambulance Service NHS Trust for participating in the research and their participating staff. The lead author, Dr Kim Kirby, has completed a Clinical Doctoral Research Fellowship funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research in the UK (ICA-CDRF-2018-04-ST2-007). This manuscript is an output from this fellowship funding.

Footnotes

Supplementary material to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resplu.2023.100490.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary material to this article:

References

- 1.Snooks H., Watkins A.J., Bell F., et al. Call volume, triage outcomes, and protocols during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom: Results of a national survey. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021;2:e12492. doi: 10.1002/emp2.12492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NHS England. Ambulance-response-programme-review.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed April 27, 2021. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/ambulance-response-programme-review.pdf.

- 3.Snooks H., Nicholl J. Sorting patients: the weakest link in the emergency care system. Emerg Med J EMJ. 2007;24:74. doi: 10.1136/emj.2006.038596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bobrow B.J., Panczyk M., Subido C. Dispatch-assisted cardiopulmonary resuscitation: the anchor link in the chain of survival. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2012;18:228–233. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e328351736b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirby K., Voss S., Bird E., Benger J. Features of Emergency Medical System calls that facilitate or inhibit Emergency Medical Dispatcher recognition that a patient is in, or at imminent risk of, cardiac arrest: a systematic mixed studies review. Resusc Plus. 2021;8 doi: 10.1016/j.resplu.2021.100173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perera N., Birnie T., Whiteside A., Ball S., Finn J. “If you miss that first step in the chain of survival, there is no second step”–Emergency ambulance call-takers’ experiences in managing out-of-hospital cardiac arrest calls. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0279521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0279521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.International Academies of Emergency Dispatch. Medical Priority Dispatch System – IAED. Published 2022. Accessed September 28, 2022. https://www.emergencydispatch.org/what-we-do/emergency-priority-dispatch-system/medical-protocol.

- 8.International Academy of Emergency Dispatch. APRIL 2018: Standards 10 is our latest set of performance requirements for police, fire, and medical emergency calltaking – IAED. Published 2018. Accessed September 9, 2023. https://www.emergencydispatch.org/in-the-news/performance-standards/33f81d37-bd1a-4e0a-a292-19ea6537bb05.

- 9.Malterud K., Siersma V.D., Guassora A.D. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26:1753–1760. doi: 10.1177/1049732315617444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braun V., Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2019;11:589–597. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byrne D. A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Quant [Published online June 26, 2021]. 10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y. [DOI]

- 13.Delve. The importance of reflexivity in qualitative research. Delve. Accessed December 17, 2021. https://delvetool.com/blog/reflexivity.

- 14.Lumivero (2017) NVivo (Version 12). www.lumivero.com.

- 15.Clawson J., Olola C.H.O., Heward A., Scott G., Patterson B. Accuracy of emergency medical dispatchers’ subjective ability to identify when higher dispatch levels are warranted over a Medical Priority Dispatch System automated protocol’s recommended coding based on paramedic outcome data. Emerg Med J EMJ. 2007;24:560–563. doi: 10.1136/emj.2007.047928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Møller T.P., Jensen H.G., Viereck S., Lippert F., Østergaaard D. Medical dispatchers’ perception of the interaction with the caller during emergency calls – a qualitative study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2021;29:45. doi: 10.1186/s13049-021-00860-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Svensson M., Pesämaa O. How does a caller’s anger, fear and sadness affect operators’ decisions in emergency calls? Int Rev Soc Psychol. 2018;31:7. doi: 10.5334/irsp.89. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ngo H., Birnie T., Finn J., Ball S., Perera N. Emotions in telephone calls to emergency medical services involving out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a scoping review. Resusc Plus. 2022;11 doi: 10.1016/j.resplu.2022.100264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golding S.E., Horsfield C., Davies A., et al. Exploring the psychological health of emergency dispatch centre operatives: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3735. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wennlund K.T., Kurland L., Olanders K., et al. Emergency medical dispatchers’ experiences of managing emergency calls: a qualitative interview study. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e059803. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bohm K., Stålhandske B., Rosenqvist M., Ulfvarson J., Hollenberg J., Svensson L. Tuition of emergency medical dispatchers in the recognition of agonal respiration increases the use of telephone assisted CPR. Resuscitation. 2009;80:1025–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gram K.H., Præst M., Laulund O., Mikkelsen S. Assessment of a quality improvement programme to improve telephone dispatchers’ accuracy in identifying out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resusc Plus. 2021;6 doi: 10.1016/j.resplu.2021.100096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riou M., Ball S., Williams T.A., et al. ‘She’s sort of breathing’: What linguistic factors determine call-taker recognition of agonal breathing in emergency calls for cardiac arrest? Resuscitation. 2018;122:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2017.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Operators’ experiences of emergency calls. J Telemed Telecare. 2004;10(5):290–7. 10.1258/1357633042026323. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Gerwing J., Steen-Hansen J.E., Mjaaland T., et al. Evaluating a training intervention for improving alignment between emergency medical telephone operators and callers: a pilot study of communication behaviours. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2021;29:107. doi: 10.1186/s13049-021-00917-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leonardsen A.C., Ramsdal H., Olasveengen T.M., et al. Exploring individual and work organizational peculiarities of working in emergency medical communication centers in Norway- a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:545. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4370-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lerner E.B., Rea T.D., Bobrow B.J., et al. Emergency medical service dispatch cardiopulmonary resuscitation prearrival instructions to improve survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:648–655. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ee5fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perera N., Finn J., Bray J. Can emergency dispatch communication research go deeper? Resusc Plus. 2022;9 doi: 10.1016/j.resplu.2021.100192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.