Abstract

Rationale & Objective

Stigma contributes to ineffective treatment for pain among individuals with kidney failure on dialysis, particularly with buprenorphine pain treatment. To address stigma, we adapted a Design Sprint, an industry-developed structured exercise where an interdisciplinary group works over 5 days to clarify the problem, identify and choose a solution, and build and test a prototype.

Study Design

Adapted Design Sprint which clarified the problem to be solved, proposed solutions, and created a blueprint for the selected solution.

Settings & Participants

Five individuals with pain and kidney disease receiving dialysis, 5 physicians (nephrology, palliative care, and addiction medicine) and 4 large dialysis organization leaders recruited for specific expertise or experience. Conducted through online platform (Zoom) and virtual white board (Miro board).

Analytical Approach

Descriptions of the Design Sprint adaptations and processes.

Results

To facilitate patient comfort, a patient-only phase included four 90-minute sessions over 2-weeks, during which patient participants used a mapping process to define the critical problem and sketch out solutions. In a physician-only phase, consisting of two 120-minute sessions, participants accomplished the same tasks. During a combined phase of two 120-minute sessions, patients, physicians, and large dialysis organization representatives vetted and developed solutions from earlier phases, leading to an intervention blueprint. Videoconferencing technology allowed for geographically diverse representation and facilitated participation from patients experiencing medical illness. The electronic whiteboard permitted interactive written contributions and voting on priorities instead of only verbal discussion, which may privilege physician participants. A skilled qualitative researcher facilitated the sessions.

Limitations

Challenges included the time commitment of the sessions, absences owing to illness or emergencies, and technical difficulties.

Conclusions

An adapted Design Sprint is a novel method of efficiently and rapidly incorporating multiple stakeholders to develop solutions for clinical challenges in kidney disease.

Plain Language Summary

Stigma contributes to ineffective treatment for pain among individuals with kidney failure on dialysis, particularly when using buprenorphine, an opioid pain medicine with a lower risk of sedation used to treat addiction. To develop a stigma intervention, we adapted a Design Sprint, an industry-developed structured exercise where an interdisciplinary group works over 5 days to clarify the problem, identify and choose a solution, and build and test a prototype. We conducted 3 sprints with (1) patients alone, (2) physicians alone, and (3) combined patients, physicians, and dialysis organization representatives. This paper describes the adaptations and products of sprints as a method for gathering diverse stakeholder voices to create an intervention blueprint efficiently and rapidly.

Index Words: Stigma, dialysis, pain, buprenorphine, human-centered design

Treating painful conditions among individuals with kidney failure treated by dialysis involves multiple challenges, including complex physiological states,1 specific medication management considerations,2 unique painful states associated with comorbid conditions, and a fragmented health care system that separates dialysis care from other forms of health care.3 Individuals receiving dialysis may be prescribed opioids to manage painful conditions,4 even though observational studies show a dose-response correlation between full agonist opioids and increased morbidity and mortality.5,6 A potentially safer medication, buprenorphine, is a partial opioid agonist that is metabolized in the liver and not removed by dialysis. With less sedation than full agonist opioids, buprenorphine is attractive for individuals with multiple comorbid conditions. Recent veterans administration clinical guidelines include buprenorphine for pain as a first-line option.7 However, adoption of buprenorphine for therapy among individuals with kidney failure receiving dialysis faces numerous barriers, such as unfamiliarity with the medication, the need for a special Drug Enforcement Agency waiver to prescribe it, and its frequent absence from the insurance formularies for pain. Another barrier is stigma, a social process characterized by labeling, stereotyping, and separation, leading to status loss and discrimination. It can manifest with internalized shame, fear, and guilt and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.8,9

This paper describes a protocol for a novel method to develop an intervention—in this case, an intervention to lower the stigma against using buprenorphine to treat pain in individuals with kidney failure treated by dialysis. We adapted human-centered design methods developed in industry to create a blueprint for developing a stigma reduction intervention for this unique population. The key principle in human-centered design is to find the right problem and then design solutions that meet human needs. The human-centered design process involves 4 activities—discover (understand the problem and context), define (clarify exactly the problem to be solved), design (create possible solutions), and validate (build prototypes and test them in the target environment).10 Human-centered design acknowledges that these tasks can only be achieved by engaging the stakeholders experiencing the problem.

Stakeholder engagement around kidney disease research methods has been employed successfully. The patient-centered outcomes research institute has incorporated patients as equal partners in the design, execution, and dissemination of results of research studies examining decision-making with kidney failure, care coordination in hemodialysis, and treatments for depression.11 Furthermore, patient advocates are key members of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK)’s kidney precision medicine project, contributing to every facet of the project and ensuring patient voices are represented in all committees, meetings and communications.12 However, meaningful stakeholder engagement in developing interventions themselves is uncommon. Use of human-centered design strategies, like Design Sprints, offers an opportunity to involve key stakeholders in intervention development and ensure usable, clinically relevant outcomes.13

We modified the Design Sprint14, 15, 16 process, a human-centered design approach developed by Google Ventures, to structure the stakeholder-driven development of a blueprint to address stigma in buprenorphine use for pain treatment in patients on dialysis. A traditional Design Sprint consists of 5 consecutive 6-hour to 8-hour days in which 6-10 company employees with complementary skills and viewpoints take part in a series of activities that foster creative design thinking and decision-making to define the design question and then develop and test a solution. Participants complete the following 5 tasks: day 1: map (place the problem in context); day 2: sketch (create potential solutions); day 3: decide (narrow down the solutions); day 4: prototype (build a prototype); and day 5: test (test the prototype). Although the Design Sprint methods were originally aimed at commercial digital and technological solutions, many industries have adapted these methods more broadly. This paper describes the adaptation and process of carrying out the Design Sprint as an example for others designing impactful health care research and clinical innovations. To illustrate the methods, we include visual results of the sprint activities.

Methods

The University of Pittsburgh institutional review board approved this study (IRB approval number 21010208). All participants gave informed consent.

Design Sprint Adaptations

We modified the Design Sprint to maximize participation, leverage mobile technology to assess needs across a national audience, and meet the specific challenges of developing solutions within health care. Such modifications allowed us to create a unique application of human-centered design for use in health care settings. Key adaptations are described below and summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Design Sprint Adaptations

| Adaptation | Reason | Impacts |

|---|---|---|

| Shortened Sprint | Both patients and clinicians face numerous time constraints that made the traditional sprint structure of five 6-h days infeasible. |

|

| Remote Sprint | The COVID-19 pandemic rendered conditions unsafe to host an in-person design sprint. |

|

| Three phases | Synchronous sessions that include clinicians and patients at the same time may be negatively affected by power dynamics and conflicting viewpoints. |

|

| No user testing | The end goal of the Sprint was to create a plan for the intervention. The plan itself could not be user tested because of its intangible nature, whereas testing the intervention would require IRB approval and many resources that could not be conducted effectively and ethically within the timeline. |

|

IRB, Institutional Review Board.

Stakeholder-Related Adaptations: Time Constraints

Crucial stakeholders for this design sprint included patients receiving dialysis, nephrologists, primary care providers, pain (palliative care) specialists, and organizational representatives from dialysis treatment facilities. From a patient perspective, barriers to participating in the traditional 6-hour sessions conducted over consecutive days include the lengthy commitment to in-center, 4-hour dialysis sessions spread over 3 days each week and fatigue and other symptoms related to underlying conditions or dialysis itself.17 Clinicians and organizational representatives also face time constraints with ongoing clinical and administrative responsibilities.

Resulting Adaptation

Our Design Sprint included asynchronous preparatory work (1-2 hours) and 13 hours of interactive sessions (see Table 2). We felt this modification was more feasible in the health care context while still allowing for rich data gathering in the interactive sessions. All sessions were conducted remotely, which alleviated travel burdens and allowed for the collection of national perspectives.

Table 2.

Logistics for Each Sprint

| Participants | Sessions | Total time | Schedule | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Patient Sprint | 5 | 4 | 360 min | Tuesday/Thursday 4 PM-5:30 PM EST over 2 wk |

| 2 Clinician Sprint | 5 | 2 | 240 min | Monday/Thursday 4 PM -6 PM EST same wk |

| 3 Combined Sprint | 11 | 2 | 240 min | Monday/Thursday 4 PM-6 PM EST same wk |

EST, Eastern Standard Time.

Stakeholder-Related Adaptations: Power Differential

Mixed-participant groups, although critical to integrating perspectives from diverse stakeholders, pose challenges. Power differentials exist between patients and clinicians, given that clinicians hold significant social status and medical control (eg, prescribing, access to health care services, and referrals). Patients may be reluctant to challenge clinician perspectives and disrupt perceived hierarchies, especially when discussing negative encounters with clinicians and health care systems. Similarly, clinicians may be less likely to discuss complex, stressful, or problematic patient care issues in the presence of patients and may use medical jargon that patients do not easily understand. Our intervention target dealt directly with a sensitive topic: buprenorphine and associated addiction stigma. By nature, stigmatizing experiences are difficult to discuss, and we felt a mixed-group idea-generating phase may exacerbate reluctance to disclose. Thus, it was particularly important for us to adapt the Design Sprint to accommodate separate, safe, idea-generating, and intervention-sketching phases so that each participant group could share their experiences freely.

Resulting Adaptation

We grouped the Design Sprint into 3 phases. Phases 1 (patient-only) and 2 (clinician-only) were designed with a parallel structure. In the third phase, we intentionally created a mixed-group sprint (patients, clinicians, and organizational representatives) to review the intervention sketches. With the guidance of a skilled facilitator, we anticipated that the mixed-group phase (decide and prototype activities) would ensure maximum feasibility, applicability, and potential impact of proposed interventions.

Health Research-Related Adaptations: Implementation and User Testing

Whereas a traditional Design Sprint incorporates user testing into the fifth day, the complex nature of health care and ethical considerations in human subject research can make the direct transition from ideation to testing infeasible for health care studies.

Resulting Adaptation

Our sprint focused on the first 4 tasks of a traditional Design Sprint (map, sketch, decide, prototype), with the fifth task—user-testing—to be conducted as a follow-up study to evaluate the solution in a scientifically rigorous and safe manner. We emphasized activities from the map, sketch, and decide days because these are most applicable to designing an intervention. The 1-2 hours of out-of-session work helped to introduce key scientific and health content crucial to addressing the target problem, which allowed the sprint sessions to focus on the interactive and creative processes involved in developing a solution.

Interactive Digital Communication

Although Design Sprints are typically conducted in person, the COVID-19 pandemic required this sprint to be conducted over the Zoom telecommunications platform, where participants could also use the chat function to access technical support. Participants, the facilitator, and technical support team members also accessed Miro, a virtual whiteboard software, throughout the sprint. The sprint team predesigned each activity and made available a framework and directions for participants unfamiliar with the software. The facilitator used the share screen function to display the Miro board to the group when introducing activities and facilitating further discussion with already-completed activities. The facilitator could easily show previously completed activities at any time during the sprint because the Miro board continuously saves work onto an extensive digital canvas. Sprint participants used either laptops or desktops and were asked to turn their cameras on, if comfortable. The sessions were recorded for future analysis. Participants used Miro functions to annotate board notes.

Phase 1: Patient Participant Sprint: October 2021

Participants

The target recruitment was 5-8 individuals who were receiving in-center hemodialysis either at the time or previously and who reported chronic pain (pain that impaired activities for at least 3 months). Recruitment was from a convenience sample. A member of the research team who belonged to an NIDDK stakeholder advisory group of patients with kidney failure reached out to other members of the group, who then passed on information about the study to their networks.

Of the 5 patient participants, the ages were 26-65 years old, and 2 were female.

Procedures

Each participant completed pre-work before the first sprint, which consisted of 2 components, as follows: (1) 6 brief videos (total of 40 minutes) to introduce key concepts, such as the sprint method, stigma, kidney failure and pain, buprenorphine, the Behavior Change Wheel, a framework for designing interventions aimed at changing behavior,18 and using Miro software; and (2) an icebreaker activity to ensure they could access and use basic functions in Miro.

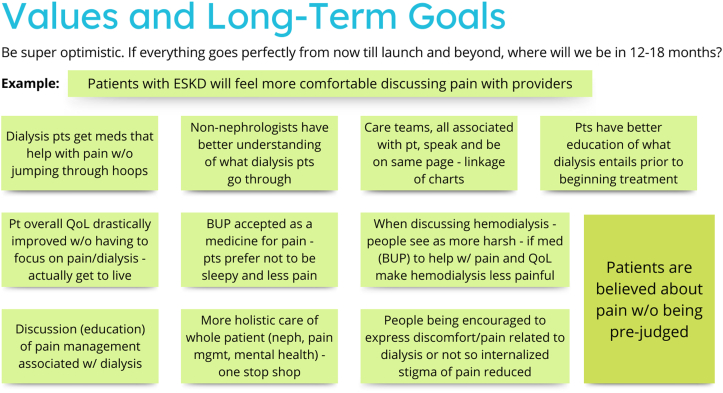

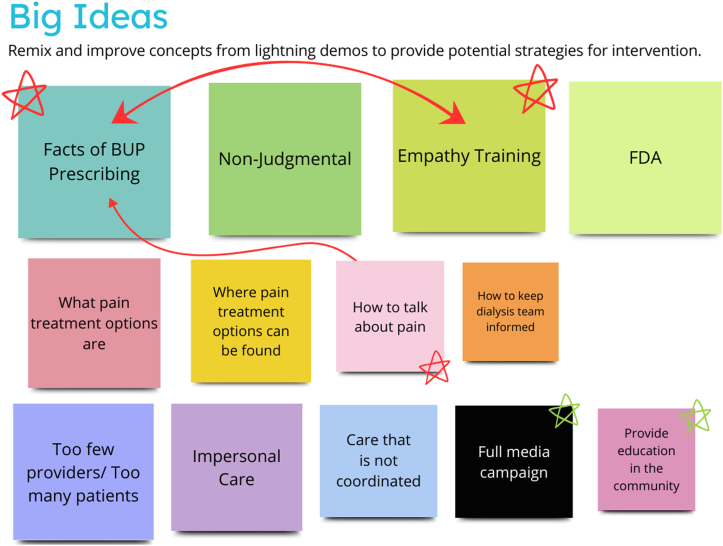

The first sprint consisted of four 90-minute sessions held over 2 weeks. During these sessions, a facilitator (M.H.) with extensive experience leading and analyzing focus groups guided the participants through a series of activities derived from the Design Sprint methodologies to identify target areas for the intervention and sketch ideas for potential interventions (see Table 3). All activities involved putting sticky notes on the virtual blackboard, either by the group facilitators (with verbal direction from the participants) or the participants themselves. The first session began with a brief introduction of the study team and overall goals for the sprint, while the remaining sessions began with a short recap of the previous session. To help them think about targets for the intervention, the research team created a map of the environmental influences for a patient on dialysis experiencing pain, which the participants refined (Fig 1). After identifying values and long-term goals (Fig 2), the group then created “how might we” questions that, if answered or solved, might move toward a solution to the predefined values and goals. The participants sorted these questions into categories (public education, patient education, physician education, institutional education, and miscellaneous) and used dots to vote on their top choices to continue to pursue (Fig 3). Once the top questions were identified (“how might we diminish the stigma of prescribing buprenorphine to patients receiving dialysis?”, “how might we help patients receiving dialysis discuss their pain issues with their health care professionals?”, “how might we encourage more health care professionals to recommend buprenorphine to patients receiving dialysis?”, and “how might we train pharmacists to help with pain?”). The participants then created lightning demonstrations, or suggestions for elements of solutions to the top questions. They presented them to each other and then added big ideas important to include with the solutions (Figs 4 and 5). The final steps included creating sketches of proposed solutions, followed by group discussion and voting on key elements for the next step (Fig 6). At the conclusion of phase 1, participants had selected 2 top sketches, which were included in phase 3 (providers and participants combined sprint).

Table 3.

Phase 1 and 2 Sprint Activities14

| Activitya | Description | Phase 1 Session | Phase 2 Session | Purpose of Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Map | The study team developed a preliminary process map of the typical experience of an ESRD patient with pain attempting to get that pain addressed. Participants reflected on the map to identify anything that could be added to the map and identify how stigma may be enacted in the interactions shown on the map. | 1 | N/A | To establish an agreed upon pathway by which users (patients, clinicians, finance, and delivery systems) will interact with the intervention, so that all future activities are contextualized within the path of the intended user. |

| Goals and values | Using the sticky notes tool on Miro, participants wrote goals that describe the outcomes they would like to see if an intervention worked perfectly and values that they would like to see enacted in the intervention. | 1 | 1 | To create a clear target to guide the remaining discussions throughout the sprint. |

| “How might we” notes | For 5 minutes, participants used the sticky notes tool in Miro to write as many topical “how might we…” questions as they could that related to addressing stigma and pain treatment for patients with ESRD. Once the notes had been written, the facilitator helped participants categorize the notes into broad topics and worked to clarify the meaning of notes. Participants voted on the top 3 “how might we” notes, to establish a focus for the intervention sketches. | 2 | 1 | To establish a consistent format for identifying opportunities to improve on the problems identified. The voting process prioritizes the opportunities that the group will focus on throughout the remaining steps. |

| Lightning demonstrations | Each participant created a collage of notes describing products, programs, and strategies that they have seen used in other contexts that may be useful for developing the current intervention. Each participant was given 3 minutes to describe their ideas and how they could be useful for designing an intervention. | 3 | N/A | To collect comparable examples of relevant solutions and techniques that have been used by competitors or other organizations to inspire ideas for a new solution. |

| Remix and improve | The facilitator guided a discussion of the ideas shared in the lightening demonstrations and worked with participants to create a list of key ideas representing common ideas apparent among the lightening demonstrations. | 3 | N/A | To break down the lightening demonstrations into individual components that can be assessed for relevance, reconfigured, and recombined to create entirely new solutions that will inspire the sketches. |

| Sketches | Participants used the design sprint sketching methods to create a 3-panel sketch of an idea for an intervention with the left side of each panel containing a picture of the step and the right side of each panel containing a brief textual description. | 4 | 2 | For each participant to independently draw on each of the previous steps to brainstorm a possible solution and present the solution in a simple way by drawing it with 3 simple panels. |

| Art museum | Participants displayed their sketches on the Miro board, and each participant was given 4 minutes to describe the sketch. | 4 | 2 | To present all sketches side by side, with the narration to enhance legibility and understandability. |

| Heat map | Each participant received 5 dots on the Miro board, which they could move to their favorite individual panels among all the sketches. | 4 | 2 | To create a heat map image that calls attention to the ideas the group finds intriguing. |

| Critique | The facilitator guided a brief critique, calling attention to panels that received many votes during the heat map stage and allowing participants to explain what they appreciated about these ideas. | 4 | 2 | To ensure brevity and focused conversation while allowing for further discussion on the standout ideas identified in the heat map exercise to explain the strengths and identify any concerns and questions. |

| Straw poll | Each participant received a single dot to vote on their favorite sketch on the Miro board. After voting, each participant received 1 minute to explain why they voted for their selected sketch. | 4 | 2 | To gauge the group’s stance toward the sketches after the discussions had during the speed critique and allow each participant the chance to explain the reasoning from the perspective of their unique expertise. |

| Super vote | To establish the top 2 sketches to review during the third phase of the sprint, each participant received 2 dots, which they used to vote on their 2 favorite sketches. The 2 sketches with the most votes were selected to proceed to phase 3. | 4 | 2 | To decisively establish which sketches will proceed forward into the prototyping phase. |

Abbreviation: ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

Activities are listed in the table in the order that they were performed during the sprint.

Figure 1.

Map of the environmental influences for a patient receiving dialysis experiencing pain, after refinement by patient sprint participants.

Figure 2.

Values and long-term goals proposed by patient Sprint participants for what an intervention would accomplish for patients receiving dialysis experiencing pain.

Figure 3.

“How might we” questions to move toward a solution to the values and long-term goals, sorted into categories by patient participants and prioritized by votes (indicated by the red dot).

Figure 4.

Lightning demonstrations: ideas for practical action to contribute to an intervention that are presented by each participant.

Figure 5.

Big ideas: identifying big picture ideas from the lightning demonstrations, with prioritization and linkage to include in the final intervention.

Figure 6.

Patient sketches of what an intervention would look like, including voting on which elements should be included (dots, stars, squiggles as part of the discussion, and prioritization).

Phase 2: Providers Sprint: January 2022

Participants

The target recruitment was for 5-8 individuals who represented a mix of physicians (nephrologists, primary care providers, and addiction medicine physicians), pharmacists, and large dialysis organization representatives. The physicians were recruited as a snowball sample through professional networks from the research team members.

The 5 participants in phase 2 included 1 addiction medicine physician, 2 primary care physicians, and 2 nephrologists. Three additional participants (1 pharmacist and 2 dialysis organization representatives) consented to the study but did not show up for the sprint.

Procedures

Phase 2 of the sprint paralleled phase 1 in focusing on identifying the target for the intervention and developing initial ideas for the intervention. Because of time constraints for clinicians, phase 2 took place over two 120-minute sessions. Participants completed the same pre-work as the patients in phase 1. Activities completed during the sprint were carried out in the same manner as during phase 1, although 2 activities from phase 1 were not included owing to time constraints (Table 3).

Instead of including the full mapping phase, participants in phase 2 briefly reviewed the map of the process flow for a patient with kidney failure. Many of these participants were highly familiar with this process, as they play key roles in the care network for patients with kidney failure. Participants also reflected on potentially relevant products, programs, and strategies used in other contexts before the sketching exercise on day 2 of the sprint. Although participants in phase 2 were aware that a previous sprint with patient participants had occurred, they were not informed of the ideas that resulted from phase 1 until phase 2 had concluded. The values and long-term goals suggested by the clinicians were similar to those of the patient sprint (see Fig 2) with additional systemic goals (eg, removal of any insurance or previous approval barriers for buprenorphine acquisition) and a focus on provider confidence (eg, less fear among prescribers about buprenorphine). The clinicians then grouped their “how might we” questions into 7 categories (education, patient-focused, provider-focused, clinic-within-the clinic, logistic, policy or guideline-level and empowerment; Fig 7). In the end, the final single question was how might we assess and manage pain within the context of kidney care for dialysis patients? At the conclusion of phase 2, participants had selected their top 2 sketches.

Figure 7.

“How might we” questions to move toward a solution to the values and long-term goals, sorted into categories by clinician participants and prioritized by votes (indicated by the red dots for specific and yellow stars for categories).

Phase 3: Combined Sprint: March 2022

Participants

All participants in phases 1 and 2 were invited to participate in phase 3. In addition, individuals from large dialysis organizations who were not represented in phase 2 were invited. Eleven patients, providers, and organizational representatives were recruited for the third phase of the sprint—3 patients from phase 1, 4 of the 5 clinicians from phase 2 (1 of the nephrologists was unable to join), and 4 representatives (including medical director, social worker, and quality manager) from large dialysis organizations.

Procedures

Phase 3 was conducted over two 3-hour sessions during a single week. Participants who had not been a part of phases 1 or 2 were asked to watch the pre-work videos before the first session, and all participants engaged in an icebreaker exercise to practice using the Miro board. The facilitator guided the participants through several activities from the deciding and prototyping phases of Design Sprints as described in Table 4. Although the initial focus was on buprenorphine stigma, the group chose a more basic goal of assessing and managing pain within the context of kidney care for individuals receiving dialysis. Before deciding on a final design, a member of the study team described the APEASE criteria (acceptability, practicability, effectiveness, affordability, side effects, and equity). The group then reviewed the final sketches from both the patient and clinician sprints. See Figure 8 for the clinician sprint final sketches and examples of critiques. The top 2 clinician sprint sketches included a menu of pain treatment options that each program could refer patients to and a system where a multidisciplinary team would be educated on pain and would then work with the patient to assess their pain and create a treatment plan. The study team then presented the Behavior Change Wheel. At the culmination of phase 3, the participants had created a storyboard of how the intervention would be structured and a list of ideas for possible steps and practical components of the intervention. Details of the final storyboard and qualitative analysis of group discussions that led to the final product will be presented in a separate manuscript.

Table 4.

Phase 3 Sprint Activities

| Activitya | Description | Phase 3 Session |

|---|---|---|

| APEASE criteriab | The facilitator and a domain expert explained how APEASE criteria (acceptability, practicability, effectiveness, affordability, side-effects, and equity) can be used to evaluate and critique interventions and asked that participants consider these criteria as they engage in critiquing exercises.18 | 1 |

| Speed critique | The facilitator presented and described the top 2 sketches from phases 1 and 2. As each of the 4 sketches were presented one at a time, participants shared their feedback, critiques, and questions and allowed participants to provide critiques and pose questions about the sketches, whereas the technical support team recorded these comments. Once comments had been collected, the original creator of the sketch worked to answer any questions, and the facilitator guided a brief discussion to summarize the group’s thoughts and reflections for each sketch. Ultimately, the group found that the top scenes from each sketch (as determined by the heat maps in phases 1 and 2) fit well with each other and could be combined into 1, multi-step intervention. | 1 |

| Behavior Change Wheel discussionb | The facilitator and a domain expert reviewed the Behavior Change Wheel as a framework for designing effective interventions, and participants identified the sources of behavior, intervention functions, and policy categories through which their intervention would act.18 | 1 |

| Storyboarding | Participants selected a decider who would make the ultimate decisions as they moved through the storyboarding exercise. During the storyboarding exercise, participants identified an opening scene for where a patient with end-stage renal disease and pain would encounter their proposed intervention. From there, participants suggested next steps, also referred to as scenes, that the patient would go through as they moved through the intervention. The decider made the final decision for scenes during which the group struggled to meet consensus. Technical support recorded each step of the storyboard on a series of linked sticky notes on the Miro board. | 2 |

Activities are listed in the table in the order that they were performed during the sprint.

Activity focused on domain expertise and not derived from traditional Design Sprint methodologies.

Figure 8.

Combined patient and professionals sprint sketches of what an intervention would look like, including critiques to be solved in final intervention.

Discussion

This paper describes key adaptations that made it possible to carry out a Design Sprint aimed at meeting the specific challenges of developing solutions within health care. We changed the scope of the project (eg, dropping the pilot testing), added new technology, shortened the time commitment, and adopted a phased approach to successfully develop several intervention prototypes. The adapted Design Sprint methodology provided the research team with sample interventions and, equally importantly, detailed information about what each group of participants viewed as most important and why.

Adapting a Design Sprint to develop a clinical innovation blueprint afforded several benefits. First, the abbreviated nature of the sprint and the fact that it occurred virtually allowed more people from diverse locations and professions to participate than would have been possible with a traditional 30-hour, in-person sprint. The inclusion of patients from several states and physicians from multiple institutions allowed for discussion of regional and institutional variations in care. Second, the invitation to co-create interventions through Design Sprints was highly engaging to the participants. Although the significant health challenges faced by the patient participants sometimes prevented them from attending, they were highly motivated to participate; 1 called in from a dialysis session and another from the hospital after major surgery. Third, the group nature of co-creation allowed for real-time debate between participants as they responded to each other’s ideas. Fourth, the completed Miro boards and Zoom-recorded session provided a rich documentation of Design Sprint results.

However, this approach was not without challenges. Foremost among the challenges were technical difficulties, as participants sometimes struggled to use Miro despite previous instruction, or because of the device they used to join the meeting. These required technical support in real time, which may have distracted from the sprint activities. Second, even the abbreviated sprint time frame required substantial time commitment from participants, and personal and medical challenges prevented some participants from attending all sessions. Third, the facilitator, a qualitative methodologist with 10 years’ experience facilitating focus groups and who has completed human-centered design facilitator training, noted that keeping the sprints on track while allowing exploration of ideas as they arose was challenging, particularly in a context in which not all participants could use the Miro platform. The sheer amount of facilitation time required and the knowledge of multiple activities gave the facilitator considerably more to manage than is the case in a focus group or traditional brainstorming session. Fourth, participants with different backgrounds occasionally experienced a clash of perspectives. For example, in phase 3, providers described a particular care plan meeting as a good place to discuss patient pain, but none of the patients were aware that such a meeting occurred, despite being assured by providers that it was legally required to happen. Skilled facilitation was needed to get back to working on the intervention design.

On the basis of our experience, we suggest the following for future Design Sprints. (1) Allow extensive preparation time for the sprint—both for those facilitating and those participating. The more practice everyone has with the technology and the sprint methodology, the less likely the sprint will be derailed by problems. Facilitators should familiarize themselves with the different exercises and consider doing a dry run of the sprint with collaborators to identify potential challenges. For participants, preparation might consist of practicing using the whiteboard technology and becoming familiar with the types of exercises in the sprint. (2) Choose a skilled, knowledgeable facilitator—someone with extensive experience in facilitating group activities. In addition, the facilitator should have some content knowledge or knowledge of the goals of the project, to best direct the exercises while keeping the end goals in mind. (3) Be prepared for the technology to fail completely. Have a plan to continue with the sprint if there are technological problems—either with the platform itself not behaving as you expect it to or with participants being unable to use the technology at all. Include technical facilitators who can troubleshoot problems for participants in real time and who can fill in or describe the board to participants who cannot edit or see it. (4) Carefully consider group dynamics for each part of the sprint. Power differentials among the sprint participants may stymie creativity and the free flow of information and ideas and even exacerbate emotional issues. Potential solutions would include ensuring that no single sprint includes patients of the clinicians, nor any clinicians from the same clinical practice or institutional setting. Setting ground rules for group behavior can ensure a safe space for participants to share their own experiences. (5) Do not expect the end result to be a directly implementable intervention or product. Researchers should understand that although the sprint may result in several prototypes, those prototypes may still require substantial consideration, revision, and testing. However, the prototypes—and what they say about the problems and values of the participants—are useful data in and of themselves.

In conclusion, the industry-developed Design Sprint can be a novel approach to integrating perspectives from a variety of key stakeholders to identify and create solutions to health care problems in kidney failure. The roadmap for adapting a Design Sprint presented here can also be used to identify solutions for scenarios in other fields of health care.

Article Information

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Allison Michalowski, BA, Kerri L. Cavanaugh, MD, MHS, Megan Hamm, PhD, Caroline Wilkie, BA, Donna M. Olejniczak, MPS, MBA, Nwamaka D. Eneanya, MD, MPH, Jason Colditz, PhD, Manisha Jhamb, MD, MPH, Hailey W. Bulls, PhD, Jane M. Liebschutz, MD, MPH

Authors’ Contributions

Research idea and study design: AM, KLC, MH, NDE, MJ, HWB, JML, and CW ; data acquisition: AM, MH, DO, and JC; data analysis/interpretation: MH , KLC, JML, MJ, and HB; supervision or mentorship: KLC, NDE, MJ, and JML. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Support

NIDDK Grants # 3U01DK123812-01S1, U01DK123821. The funders of this study had no role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication.

Financial Disclosure

Dr. Liebschutz consults for Biomotivate, Inc. Dr Jhamb consults for Boehringer Ingelheim and has research support from Pfizer. Dr Eneanya is employed by Fresenius Medical Care. The remaining authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is dedicated to the memory of Robert Grindstaff, MD, who was a member of the research team up until his untimely death. We also acknowledge the following study participants who dedicated their time and effort to the project: Lynn Bowlby, Samantha Gelfand, Ginger Fuller, John Hosford , Raagini Jawa, Jennifer Jones, Eduardo Lacson, Jane Schell, Bjorg Thorsteinsdottir, Quenton Turner-Gee, and Joel Williams.

Peer Review

Received February 19, 2023. Evaluated by 3 external peer reviewers, with direct editorial input from an Associate Editor and the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form July 10, 2023.

Footnotes

Complete author and article information provided before references.

References

- 1.Davison S.N. Pain in hemodialysis patients: prevalence, cause, severity, and management. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(6):1239–1247. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Claxton R.N., Blackhall L., Weisbord S.D., Holley J.L. Undertreatment of symptoms in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39(2):211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jhamb M., Tucker L., Liebschutz J. When ESKD complicates the management of pain. Semin Dial. 2020;33(3):286–296. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daubresse M., Alexander G.C., Crews D.C., Segev D.L., McAdams-DeMarco M.A. Trends in opioid prescribing among hemodialysis patients, 2007-2014. Am J Nephrol. 2019;49(1):20–31. doi: 10.1159/000495353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kimmel P.L., Fwu C.W., Abbott K.C., Eggers A.W., Kline P.P., Eggers P.W. Opioid prescription, morbidity, and mortality in United States dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(12):3658–3670. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017010098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muzaale A.D., Daubresse M., Bae S., et al. Benzodiazepines, Codispensed opioids, and mortality among patients initiating long-term in-center hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(6):794–804. doi: 10.2215/CJN.13341019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sandbrink F., Murphy J.L., Johansson M., et al. The use of opioids in the management of chronic pain: synopsis of the 2022 updated U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2023;176(3):388–397. doi: 10.7326/M22-2917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Link B.G., Phelan J.C. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27(1):363–385. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatzenbuehler M.L., Phelan J.C., Link B.G. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):813–821. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melles M., Albayrak A., Goossens R. Innovating health care: key characteristics of human-centered design. Int J Qual Health Care. 2021;33(suppl 1):37–44. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzaa127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cukor D., Cohen L.M., Cope E.L., et al. Patient and other stakeholder engagement in Patient-centered Outcomes Research Institute funded studies of patients with kidney diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(9):1703–1712. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09780915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tuttle K.R., Bebiak J., Brown K., et al. Patient perspectives and involvement in precision medicine research. Kidney Int. 2021;99(3):511–514. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erwin K., Krishnan J.A. Redesigning healthcare to fit with people. BMJ. 2016;354:i4536. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knapp J., Zeratsky J., Kowitz B. Simon and Schuster; 2016. Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robles M.C., Newman M.W., Doshi A., et al. A physical activity just-in-time adaptive intervention designed in partnership with a predominantly black community: virtual, community-based participatory design approach. JMIR Form Res. 2022;6(3) doi: 10.2196/33087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salim H., Lee P.Y., Sharif-Ghazali S., et al. Developing an asthma self-management intervention through a web-based design workshop for people with limited health literacy: user-centered design approach. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(9) doi: 10.2196/26434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caplin B., Kumar S., Davenport A. Patients’ perspective of haemodialysis-associated symptoms. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(8):2656–2663. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michie S., van Stralen M.M., West R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]