Abstract

Many biological markers have been explored in multiple sclerosis (MS) to better quantify disease burden and better evaluate response to treatments, beyond clinical and MRI data. Among these, neurofilament light chain (Nf-L), although non-specific for this disease and found to be increased in other neurological conditions, has been shown to be the most promising biomarker for assessing axonal damage in MS, with a definite role in predicting the development of MS in patients at the first neurological episode suggestive of MS, and also in a preclinical phase. There is strong evidence that Nf-L levels are increased more in relapsing versus stable MS patients, and that they predict future disease evolution (relapses, progression, MRI measures of activity/progression) in MS patients, providing information on response to therapy, helping to anticipate clinical decisions in patients with an apparently stable evolution, and identifying patient non-responders to disease-modifying treatments. Moreover, Nf-L can contribute to the better understanding of the mechanisms of demyelination and axonal damage in adult and pediatric MS. A fundamental requirement for its clinical use is the accurate standardization of normal values, corrected for confounding factors, in particular age, sex, body mass index, and presence of comorbidities. In this review, a guide is provided to update clinicians on the use of Nf-L in clinical activity.

Keywords: Biomarkers, Diagnosis, Multiple sclerosis, Neurofilament, Pediatric multiple sclerosis, Prognosis, Treatment response

Key Summary Points

| Neurofilament, a cytoskeletal component of neurons, is a marker of axonal damage and neuronal death. Among biological markers, there is large support from the scientific literature that it is the most promising molecule for assessing axonal damage in multiple sclerosis. |

| Among the three subunits of neurofilaments, neurofilament light chain (Nf-L) has been the most extensively studied, better differentiating changes in MS patients compared to controls and in active compared to inactive MS patients. |

| Nf-L levels have been shown to have a definite role in predicting future disease evolution (relapses, disease progression, MRI measures of activity/progression) in MS patients in early stages of its development. |

| A reduction of Nf-L levels provides evidence of response to therapy, and, conversely, if increasing in spite of a disease-modifying treatment, could help to identify non-responder patients. |

| There is a large body of evidence about the role of Nf-L to assess disease activity and progression in MS. In future, Nf-L should be implemented in clinical practice as a measure of clinical activity in addition to clinical and MRI assessment. |

Biomarkers in Multiple Sclerosis

Many biological markers linked to the inflammatory demyelinating process have been explored in multiple sclerosis (MS), with the aim of providing additional measures to quantify disease burden and activity, to refine diagnosis, and to better evaluate response to treatments [1–3]. In this connection, biological markers could provide additional information on MS status, in addition to the clinical and MRI data that remain the most reliable milestones for MS assessment, and on functional and structural damage in addition to neurophysiological tests and other tools, such as optical coherence tomography [4].

Recently, there have been advances in this field, and many original studies have been published as well as reviews outlining the contributions of biomarkers in clinical assessment of MS patients.

Some of these have a well-recognized role for diagnosis, namely: oligoclonal bands and IgG index (for MS diagnosis), anti-aquaporin-4 (AQP-4)m and anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibodies [for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) and MOG-associated disorder (MOGAD) diagnosis, respectively], antibodies against IFN-β and natalizumab, and the anti-John Cunningham-virus and anti-varicella zooster virus antibodies (for treatment decisions) [1]. These tests are currently and widely used in diagnostic and clinical activity.

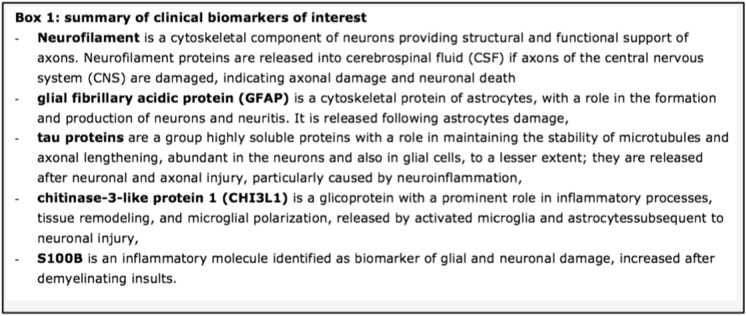

Many other molecules with a potential clinical usefulness have been detected in cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) and plasma/serum in recent years, but only a few have shown clinical relevance. According to recent studies and reviews [1–3], the most relevant are neurofilaments, glial fibrillary acidic protein, tau proteins, chitinase-3-like protein 1, and S100B (see Fig. 1). Among them, neurofilaments, a cytoskeletal component of neuronal axons that increases if axons of the central nervous system (CNS) are damaged, providing a measure of axonal damage and neuronal death, have been of definite clinical interest, becoming the most promising biomarkers for assessing axonal damage related to the demyelinating process. Searching on PubMed, more than 7,500 original papers and reviews have been published up to 2022 on neurofilaments in MS and neurodegenerative disorders. We previously discussed the contribution of neurofilament light chain (Nf-L) to better characterize pediatric MS [5]; here, we provide a more comprehensive review of the topic in both adult and pediatric MS. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Fig. 1.

Summary of clinical biomarkers of interest

Neurofilament Light Chain (Nf-L) in Adult Multiple Sclerosis

Studies on neurofilament proteins began more than 20 years ago, initially limited because of the necessity of obtaining CSF samples. In 2003, the first study was published showing that Nf-L antibodies were correlated with MRI measures of cerebral atrophy, and demonstrating the potential role of neurofilaments as a marker of tissue damage, particularly axonal loss, in MS [6].

Three subunits of neurofilaments can be detected: light (Nf-L), medium (Nf-M), and neurofilament heavy (Nf-H) chain. The most extensively studied subtype is Nf-L [5], performing better at differentiating changes in MS patients compared to controls [8], and at evaluating treatment response compared to Nf-H [9].

Initially performed on CSF samples, studies on Nf-L in MS and other neurological disorders have received a strong boost in the recent years thanks to the introduction of a new technology (SIMOA—single molecule array technology) with the possibility of detecting very low concentrations of Nf-L in serum or plasma [1–12].

The first study including a large cohort of MS patients was published in 2017 [13], providing convincing evidence on the usefulness of Nf-L as a blood biomarker of tissue damage in MS: Nf-L was higher in MS patients (a cross-over cohort of 142 subjects and a prospective cohort of 246 subjects) compared to 254 healthy controls, and higher in patients with focal lesions and gadolinium-enhancing lesions than those without. Moreover, Nf-L levels correlated with disability, the presence of relapses and future relapses and disability, and decreased under disease-modifying treatment (DMT).

By the end of 2022, more than 400 articles have been published on the topic of Nf-L in MS (source: PubMed), and we will summarize the most important studies on the various phenotypes of MS.

Neurofilament Light Chain (Nf-L) in Presymptomatic MS

Nf-L was assessed in the CSF of 23 patients with radiologically isolated syndrome (RIS) and 15 with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), compared with 15 relapsing–remitting (RR), 26 primary progressive MS patients and healthy controls [14], who were also submitted to assessment of progranulin. Both molecules significantly increased in CIS and MS patients whereas only progranulin increased in RIS patients; of note, only MRI and not clinical data were provided during the follow up, different from another study that included a larger group of healthy subjects who were prospectively evaluated after a long-term follow-up to detect those who developed MS [15]. In this study, Nf-L was assessed in samples from US military personnel who have serum samples stored from 2000 to 2011, and the serum Nf-L levels were higher in 60 subjects who later developed MS compared with matched controls, this difference increasing with decreasing time to clinical onset, which was associated with a marked increase in Nf-L levels. The overall results of this study provided evidence that MS may have a prodromal phase lasting several years, and that neuroaxonal damage already occurs during this phase, preceding clinical onset.

The prognostic role of Nf-L, CHI3L1, and oligoclonal bands for conversion to CIS and to MS was investigated in 75 patients with radiologically isolated syndrome showing that Nf-L and oligoclonal bands were independent risk factors for the development of both CIS and MS, with a better performance for oligoclonal bands, whereas CHI3L1 had a poor prognostic value [16]. The effects of high Nf-L levels shortening the time to both CIS and MS were more pronounced in patients ≥ 37 years old compared to younger patients and in those with high versus low Nf-L levels. Serum and CSF Nf-L were confirmed as significant predictors for the conversion to clinical and clinical + MRI activity in 61 patients with RIS, at 2, 3, and 5 years [17].

Neurofilament Light Chain (Nf-L) in Clinically Isolated Syndrome (CIS)

Many studies have addressed the diagnostic and prognostic role of Nf-L, measured in the CSF or serum, in patients presenting with a first neurological episode suggestive of MS. The data are reported in Table 1 and summarized in Table 2, in which the level of evidence of the results was classified according to the criteria described in Ref. [10]. In all studies except one [22], Nf-L levels were increased in CIS patients compared with controls, and correlated at baseline with the number of T2 and Gd + lesions [18, 23, 24], with diffusely abnormal white matter (DAWM) [26] at brain MRI, and expanded disability status scale (EDSS) [18, 24]. Nf-L levels predicted clinically definite MS (CDMS) or CDMS according to 2017 diagnostic criteria in all the studies [18–21, 23–25] except one [22]. The predictive value of Nf-L was higher compared to other blood biomarkers [19, 20], but lower than MRI and CSF examination in one study [19]. Of note, in two studies, Nf-L was compared with other biological markers [19, 20], resulting in the best predictor for MS development.

Table 1.

Summary of results of studies evaluating the prognostic role of Nf-L in patients with CIS

| No. | Follow-up | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disanto et al. [18] | 198 |

110 days in 100 patients who converted to CDMS 6.5 years in 98 patients who remained CIS |

Nf-L levels were higher in the two groups of MS patients compared to controls, particularly in fast converters (24.1 pg/mL vs. 19.3 pg/mL) Increased Nf-L concentration was associated with increasing numbers of T2 MRI lesions, gadolinium-enhancing lesions and higher disability scores at CIS diagnosis |

| Arrambide et al. (CSF) [19] | 68 |

78.8 months in 35 patients who converted to CDMS 57.9 months in 33 patients who remained CIS |

At screening, only Nf-L showed significant differences compared to other biomarkers (neurofascin, semaphorin 3A, fetuin A, glial fibrillary acidic protein, and Nf-H) Nf-L levels presented strong associations with brain parenchymal fraction change and percentage brain volume change at 5 years More Nf-L-positive patients evolved to MS; however, the risk of MS was lower than the presence of oligoclonal bands or T2 lesions |

| Hakansson et al. (CSF) [20] | 41 | 24 months | Nf-L in CSF at baseline is the best predictor compared to other biomarkers (glial fibrillary acidic protein, chitinase-3-like-1, matrix metalloproteinase-9 and osteopontin) |

| Tortorella et al., (CSF) [21] | 41 CIS | – |

CSF Nf-L levels were higher in CIS patients in comparison with controls CSF Nf-L was the independent predictor of MRI measures of damage |

| Tejeda-Velarde et al. (CSF) [22] | 68 (optic neuritis) | 46.4 months |

25 patients (36.7%) developed CDMS during follow-up Abnormal MRI and CSF oligoclonal bands but not Nf-L levels predicted the risk of CDMS |

| Dalla Costa et al. [23] | 222 | 100.6 months |

45 patients (20%) developed CDMS and 141 (63.5%) developed MS at 2 years according to 2017 MS diagnostic criteria Serum Nf-L was increased in patients with a recent relapse, with a high number of T2 and gadolinium-enhancing lesions at baseline MRI |

| Bittner et al. [24] |

369 CIS 445 MS According to 2010 diagnostic criteria |

At least 2 years, up to 4 years in a subgroup of 598 patients |

At baseline and year 2, Nf-L levels were higher in patients with ≥ 9 cranial T2 lesions than in those with 1–8 T2 lesions, and were higher in patients with Gd + lesions; the correlation between sNf-L and EDSS values was weak Patients with at least one relapse in the following 2 years had significantly higher levels at baseline Patients who were reclassified from CIS to RRMS (2017) had elevated Nf-L levels compared to CIS (2010) and patients remaining CIS (2017) |

| Monreal et al. [25] | 578 | 7.1 years |

Levels of Nf-L greater than 10 pg/mL were independently associated with higher risk of 6-month CDMS and an EDSS of 3 in the development cohort Highly effective DMTs were associated with lower risks of 6-month CDMS and an EDSS of 3 in patients with high baseline Nf-L values |

| Vavasour et al. [26] | 20 | – | 35% of CIS patients demonstrated diffusely abnormal white matter (DAWM): they also had decreased cortical thickness, higher lesion load, and a higher concentration of Nf-L compared to CIS without DAWM |

| Fabis Pedrini et al. [27] | 17 | 12 months | Nf-L strongly correlated with T2 and T1 lesion volume at 12 months |

Table 2.

Level of evidence of the role of Nf-L in patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) (A), and level of evidence of the correlation between Nf-L levels and clinical or MRI measures of clinical activity in cross-sectional (B) and longitudinal studies (C))

| (A) Role of Nf-L in CIS patients | Level of evidence |

|---|---|

| Higher Nf-L levels compared to controls [18, 21] | +++ |

| More patients with high Nf-L levels compared to other biomarkers, excluding OBs [19, 20] | +++ |

| Including OBs [20, 22]a | – |

| (B) Cross-sectional correlation of Nf-L levels | |

|---|---|

| With clinical severity [18, 23, 24] | +++ |

| With MRI burden/activity [21, 23, 24, 26] | +++ |

| (C) Longitudinal correlation of Nf-L levels | |

|---|---|

| With development of CDMS [18–20, 23–25] | +++ |

| With MS activity/severity [18, 24] | +++ |

| With MRI measures of activity/progression [18, 19, 27] | +++ |

Level of evidence (from Ref. [10], modified):

− lack of evidence, + results non-replicated or conflicting evidence, ++ observations that have been replicated and/or supported by independent methods, +++ high level of evidence from larger studies, consistently replicated

aOBs better predicted the development of CDMS compared to Nf-L

Neurofilament Light Chain (Nf-L) in Relapsing Remitting and Progressive MS

Many original studies as well as reviews and meta-analysis have provided a strong demonstration of Nf-L's definite role as a measure of axonal damage caused by MS, resulting in an increase in all clinical MS phenotypes [11, 12, 28], although not specific or patognomonic for this condition, as they can also increase in neurodegenerative, traumatic, and vascular disorders of the CNS [7].

Nf-L levels have been correlated with baseline clinical and neuroimaging characteristics in cross-sectional studies, and with clinical and neuroimaging evolution in follow-up series, prospectively or retrospectively collected, to determine their value to assess disease activity in RR-MS [13, 23, 24, 29–70]; some studies also included secondary progressive (SP)-MS patients. The results are summarized in Table 3 using the same scoring system of Table 2. To summarize, we can conclude that, in RR-MS, high Nf-L levels show a strong correlation with relapse rate and with neuroimaging activity (presence of gadolinium-enhancing lesions, number/new T2 lesions) in cross-sectional studies, whereas the correlation with disability is less strong. In prospective studies, the correlation is very strong with the occurrence of relapses and EDSS increasing in the subsequent 1–3 years, with NEDA status, less strong but still present with long-term progression (not confirmed in one study after a mean of 12 years of follow-up [38]), and strong with MRI measures such as brain and spinal cord volume loss in the next 2–5 years. There is a clear evidence that DMTs reduce Nf-L levels, and that they help in clinical decisions such as reducing doses, increasing the intervals of administration for some medications, such as natalizumab or rituximab, or using more aggressive therapies in active patients if highly increased levels of Nf-L are detected [51, 68–70].

Table 3.

Level of evidence (for definition see Table 2) of the correlation between Nf-L levels and clinical or MRI measures of clinical activity in cross-sectional (A) and longitudinal studies (B) in RR-MS patients (some studies also included SP-MS patients)

| (A) Cross-sectional correlation with | Level of evidence |

|---|---|

| Clinical findings | |

| Relapses [13, 23, 24, 29–32] | +++ |

| EDSS [13, 24, 31, 38] | ++ |

| MRI findings | |

| Gd-enhancing lesions [13, 23, 24, 29–32] | +++ |

| T2 lesions [13, 18, 23, 24, 31, 34] | +++ |

| Multiple MRI markers [24, 29, 32–40] | ++ |

| (B) Longitudinal correlation with | |

|---|---|

| NEDA status [41–47] | +++ |

| Relapses and EDSS/disability increase in the next 1–3 years [18, 24, 31, 35, 36, 52, 53] | +++ |

| Long-term progression/disability (> 5 years) [35, 43, 54–56] | ++ |

| Brain/spinal cord volume loss in the next 2–5 years [46, 53, 54, 56, 57] | +++ |

| Measures of MRI progression, new T2/T2 lesion load [46, 48, 54, 58, 59] | +++ |

| Treatment response [49–51, 60–70] | +++ |

The accurate definition of normal values is a fundamental requirement for a reliable patient assessment. This issue has been specifically addressed in a recent paper reporting normative data of normal subjects (5390) with no evidence of CNS disease, taking part in four cohort studies in Europe and North America [71], and demonstrating that sNf-L concentrations increased exponentially with age, particularly in those over 50 years, with a close relationship with body mass index (BMI). This study also included 1313 RR/SP-MS patients, with a median follow-up of 5.6 years, confirming that Nf-L levels were correlated to an increased risk of future clinical or MRI disease activity, and disability-worsening in MS patients. Nf-L levels markedly decreased in MS patients treated with monoclonal antibodies (natalizumab, alemtuzumab, ocrelizumab, rituximab), and slightly in those treated with oral therapies (teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate, fingolimod, siponimod); in contrast, they remained elevated in patients treated with interferons and glatiramer acetate.

The relationship with age has been confirmed by another study, as well as with BMI and comorbidities such as diabetes and impaired renal function [46].

The possibility to better understand and quantify disease progression is particularly relevant in progressive MS, in which the neurodegenerative component plays an important role, and progressive axonal damage greatly contributes to MS progression. The potential usefulness of Nf-L has been investigated in a meta-analysis in which 17 high-quality studies were evaluated, selected form 76 relevant papers on this topic [72]. The results can be summarized as follows:

relationship with current disability (EDSS): a correlation was found in 4 studies including 1874 patients, but not confirmed in 6 studies including 1143 patients (assessed in CSF in 243 of them),

relationship with EDSS progression: a correlation was found in 2 studies including 1757, but not confirmed 3 studies including 1330 patients (assessed in CSF in 70 of them),

relationship with current inflammatory disease activity: a correlation was found in 10 studies including 3533 patients (assessed in CSF in 176 of them), but not confirmed in 3 studies including 1260,

relationship with brain atrophy development: a correlation was found and confirmed in 5 studies including 2337 patients (assessed in CSF in 70 of them),

relationship with DMTs: a correlation was found in all the 4 randomized control trials with DMTs, which included 3020 patients.

Neuroaxonal damage is a factor largely involved in the development of cognitive impairment in MS patients, a symptom that greatly contributes to increasing their disability. Increased Nf-L levels have been found in patients with cognitive impairment at baseline [73, 74], compared to patients cognitively preserved, with an additive role with respect to MRI measures [75], and predicted cognitive decline in the follow-up in both RR and progressive MS patients [72, 74, 76, 77]; in the latter form, independently from changes of T2 and normalized regional volumes.

Neurofilament Light Chain (Nf-L) in Pediatric MS (ped-MS)

Nf-L has been tested in patients with ped-MS and other demyelinating syndromes (ADS) in some recent studies, showing clear evidence of their usefulness in predicting future evolution of the disease, a confirmed usefulness to identify patients with an active form of MS, and strong evidence of their role in monitoring the effect of DMT, so confirming the promising role of this biomarker to also monitor MS evolution in these patients. To summarize:

a significant correlation between serum and CSF Nf-L values was found in a cohort of 102 children with a first episode classified as ADS, particularly in the MS group; higher serum Nf-L values at baseline predicted the risk of a second MS attack [78],

higher serum levels of Nf-L were confirmed in a cohort of 129 children with an ADS episode compared to healthy controls: in children with MS, Nf-L values correlated with cerebral and spinal cord MRI lesions and predicted a higher number of subsequent relapses [79].

a study including 55 children with MS confirmed the strong correlation between clinical and MRI findings: Nf-L levels were significantly higher at baseline in untreated patients compared to controls, relatively low in MS patients without clinical or MRI disease activity, and higher in those with a recent relapse and an high EDSS score. Nf-L significantly decreased after interferon beta-1a/b treatment and after switching to fingolimod [80].

another study of 142 children with MS confirmed the increase of serum Nf-L compared to healthy controls, particularly in patients with a recent relapse and new/enlarging T2 or gadolinium-enhancing MRI lesions [81].

the effect of treatment on Nf-L in ped-MS has been well demonstrated by the TERIKIDS trial [82], in which Nf-L was serially measured in ped-MS patients randomized 2:1 to receive teriflunomide or placebo in a double-blind period. At baseline, Nf-L levels were higher in patients with a shorter disease duration, with higher Gd-enhancing lesion counts and T2 lesion volume, predicting an high MRI activity or clinical relapse during the double-blind period. Nf-L values were lower in patients treated with teriflunomide compared to placebo, confirming the usefulness of this measure to assess treatment response.

Compared to the adult form, ped-MS presents some peculiar aspects [83]: inflammation is more prominent, as suggested by the higher relapse rate and by the higher number of T2 and gadolinium-enhancing lesions on MRI. Since the demyelinating process develops in crucial phases of maturation of the CNS, MS causes a severe brain damage in young patients leading to brain atrophy and a reduced brain growth [84, 85], probably not sufficiently compensated by the possible disappearance of T2 lesions in subsequent scans and by the relatively low number and rate that evolve in hypointense lesions [86–88].

However, in spite of the greater severity of the disease, children with MS show a higher ability to compensate brain damage, as suggested by clinical findings (longer time to reach mild or severe disability, better recovery after relapses [89, 90]), and by the ability to compensate cognitive impairment in the long-term, after its initial decline [91]. Studies with non-conventional MRI in ped-MS patients have shown a less intrinsic degree of involvement of the so-called “normal appearing white matter”, compared to adult MS [92], and a more preserved functional reserve, with a better ability to compensate brain damage, as suggested by the less extensive activation of cortical areas on functional MRI performed during a motor task [93] compared to adult RR/SP-MS patients.

Within the group of patients with ped-MS, those with onset before 11–12 years of age have additional distinct characteristics with respect to older ones: the MS incidence in boys and girls is similar, disease progression is slower, clinical manifestations have a different pattern [86], and the effect to DMTs is more pronounced [94, 95], suggesting that age, hormonal age-related changes, and other unknown factors can differently modulate MS onset and progression in the pediatric group.

Nf-L, accurately standardized in normal controls and assessed in ped-MS patients in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, could help to characterize the different clinical patterns between patients with prepubertal versus postpubertal ped-MS, and in ped-RR-MS versus adult RR-MS, in addition to clinical and neuroimaging data.

Conclusion

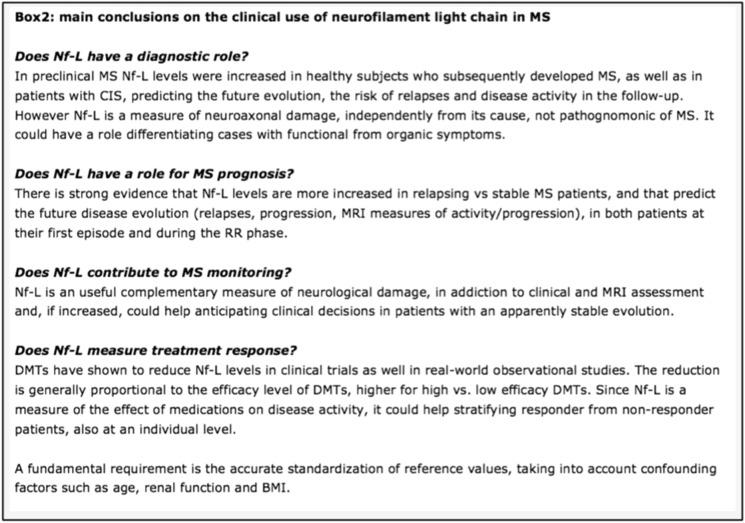

In this review, we have aimed to summarize the many studies on the clinical use of Nf-L in MS (see Fig. 2). To conclude, there is a clear strong evidence that Nf-L has a definite role to provide a reliable measure of neuroaxonal damage caused by the demyelinating process and of the neuroprotective effect of medications.

Fig. 2.

Main conclusions on the clinical use of neurofilament light chain in MS. MS multiple sclerosis, CIS clinically isolated syndrome, NF-L neurofilament light, DMT disease-modifying treatments

This means that the role of neurofilaments will soon change from an interesting biomarker, mainly used in scientific research, to a kind of “neurologist’s C-reactive protein” [96] with many possible implications in clinical activity and research. It is worth mentioning that the test provides a reliable measure of axonal damage, but that it lacks specificity, since Nf-L can also increase in other neurological conditions, and its affordable and appropriate use in clinical activity requires a carefully standardization of normal values.

Acknowledgements

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance

This article did not use medical writing or editorial assistance.

Author Contributions

Angelo Ghezzi and R.F. Neuteboom equally contributed to the preparation of the present manuscript.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Angelo Ghezzi and R.F. Neuteboom both declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Prior Presentation This manuscript provides more comprehensive literature and clinical data on a topic that has been briefly anticipated in a short commentary published in Multiple Sclerosis Journal, 2023, and related to the article published here.

The original online version of this article was revised to correct Reference 25.

Change history

3/18/2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s40120-024-00598-6

References

- 1.Ziemssen T, Yang J, Hamade M, Wu Q, et al. Current and future biomarkers in multiple sclerosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:5877–5885. doi: 10.3390/ijms23115877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Momtazmanesh S, Shobeiri P, Saghazadeh A, et al. Neuronal and glial CSF biomarkers in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Neurosci. 2021;32:573–595. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2020-0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang J, Mohsen KM, Lars FL, et al. Inflammation-related plasma and CSF biomarkers for multiple sclerosis. PNAS. 2020;117(23):12952–12960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1912839117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guerrieri S, Comi G, Leocani L. Optical coherence tomography and visual evoked potentials as prognostic and monitoring tools in progressive multiple sclerosis. Front Neurosci. 2021;5(15):692599. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.692599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghezzi A, Neuteboom RF. The contribution of neurofilament light chain to better characterize pediatric multiple sclerosis (editorial on: Plasma neurofilament light chain in children with relapsing MS receiving teriflunomide or placebo: a post hoc analysis of the randomized TERIKIDS trial) Mult Scler. 2023;29:668–670. doi: 10.1177/13524585231161148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eikelenboom MJ, Petzold A, Lazeron RHC, et al. Multiple sclerosis: neurofilament light chain antibodies are correlated to cerebral atrophy. Neurology. 2003;60:219–223. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000041496.58127.E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varhaug KN, Torkildsen Ø, Myhr KM, et al. Neurofilament light chain as a biomarker in multiple sclerosis. Front Neurol. 2019;10:338. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuhle J, Plattner K, Bestwick JP, et al. A comparative study of CSF neurofilament light and heavy chain protein in MS. Mult Scler. 2013;19:1597–1603. doi: 10.1177/1352458513482374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuhle J, Malmeström C, Axelsson M, et al. Neurofilament light and heavy subunits compared as therapeutic biomarkers in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2013;128:e33–e36. doi: 10.1111/ane.12151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bittner S, Oh J, Havrdová EK, et al. The potential of serum neurofilament as biomarker for multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2021;144:2954–2963. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kölliker Frers RA, Otero-Losada M, Kobiec T, et al. Multidimensional overview of neurofilament light chain contribution to comprehensively understanding multiple sclerosis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:912005. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.912005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferreira-Atuesta C, Reyes S, Giovanonni G, Gnanapavan S. The evolution of neurofilament light chain in multiple sclerosis. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:642384. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.642384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Santo G, Barro C, Benkert P, et al. Serum neurofilament light: a biomarker of neuronal damage in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2017;81:857–870. doi: 10.1002/ana.24954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pawlitzki M, Sweeney-Reed CM, Bittner D, et al. CSF-progranulin and neurofilament light chain levels in patients with radiologically isolated syndrome-sign of inflammation. Front Neurol. 2018;9:1075. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.01075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bjornevik K, Munger KL, Cortese M, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain levels in patients with presymptomatic multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:58–64. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.3238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matute-Blanch C, Villar LM, Álvarez-Cermeño JC, et al. Neurofilament light chain and oligoclonal bands are prognostic biomarkers in radiologically isolated syndrome. Brain. 2018;141:1085–1093. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rival Manon M, Thouvenot E, Du Trieu de Terdonck L, et al. Neurofilament light chain levels are predictive of clinical conversion in radiologically isolated syndrome. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2022;10(1):e200044. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000200044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Disanto G, Adiutori R, Dobson R, International Clinically Isolated Syndrome Study Group et al. Serum neurofilament light chain levels are increased in patients with a clinically isolated syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:126–129. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-309690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arrambide G, Espejo C, Eixarch H, et al. Neurofilament light chain level is a weak risk factor for the development of MS. Neurology. 2016;87:1076–1084. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Håkansson I, Tisell A, Cassel P, et al. Neurofilament light chain in cerebrospinal fluid and prediction of disease activity in clinically isolated syndrome and relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24:703–712. doi: 10.1111/ene.13274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tortorella C, Direnzo V, Ruggieri M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament light levels mark grey matter volume in clinically isolated syndrome suggestive of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2018;24:1039–1045. doi: 10.1177/1352458517711774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tejeda-Velarde A, Costa-Frossard L, Sainz de la Maza S, et al. Clinical usefulness of prognostic biomarkers in optic neuritis. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25:614–618. doi: 10.1111/ene.13553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dalla CG, Martinelli V, Sangalli F, et al. Prognostic value of serum neurofilaments in patients with clinically isolated syndromes. Neurology. 2019;92:e733–e741. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bittner S, Steffen F, Uphaus T, et al. Clinical implications of serum neurofilament in newly diagnosed MS patients: a longitudinal multicentre cohort study. EBioMedicine. 2020;56:102807. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monreal E, Fernández-Velasco JI, García-Sánchez MI, et al. Association of serum neurofilament light chain levels at disease onset with disability worsening in patients with a first demyelinating multiple sclerosis event not treated with high-efficacy drugs. JAMA Neurol. 2021;80(4):397–403. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2023.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vavasour IM, Becquart P, Gill J, et al. Diffusely abnormal white matter in clinically isolated syndrome is associated with parenchymal loss and elevated neurofilament levels. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;57:103422. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2021.103422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fabis-Pedrini M, Kuhle J, Roberts K, et al. Changes in serum neurofilament light chain levels following narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy in clinically isolated syndrome. Brain Behav. 2022;12:e2494. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ning L, Wang B. Neurofilament light chain in blood as a diagnostic and predictive biomarker for multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0274565. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0274565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Varhaug KN, Barro C, Bjornevik K, et al. Neurofilament light chain predicts disease activity in relapsing-remitting MS. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2018;5:e422. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Novakova L, Zetterberg H, Sundstrom P, et al. Monitoring disease activity in multiple sclerosis using serum neurofilament light protein. Neurology. 2017;89:2230–2237. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barro C, Benkert P, Disanto G, et al. Serum neurofilament as a predictor of disease worsening and brain and spinal cord atrophy in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2018;141:2382–2391. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siller N, Kuhle J, Muthuraman M, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain is a biomarker of acute and chronic neuronal damage in early multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2019;25:678–686. doi: 10.1177/1352458518765666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Srpova B, Uher T, Hrnciarova T, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain reflects inflammation-driven neurodegeneration an predicts delayed brain volume loss in early stage of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2021;27:52–60. doi: 10.1177/1352458519901272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uher T, McComb M, Galkin S, et al. Neurofilament levels are associated with blood-brain barrier integrity, lymphocyte extravasation, and risk factors following the first demyelinating event in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2020;27:220–231. doi: 10.1177/1352458520912379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sellebjerg F, Royen L, Soelberg Sorensen P, et al. Prognostic value of cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament light chain and chitinase-3-like-1 in newly diagnosed patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2019;25:1444–1451. doi: 10.1177/1352458518794308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuhle J, Nourbakhsh B, Grant D, et al. Serum neurofilament is associated with progression of brain atrophy and disability in early MS. Neurology. 2017;88:826–831. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jakimovski D, Kuhle J, Ramanathan M, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain levels associations with gray matter pathology: a 5-year longitudinal study. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2019;6:1757–1770. doi: 10.1002/acn3.50872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chitnis T, Gonzalez C, Healy BC, et al. Neurofilament light chain serum levels correlate with 10-year MRI outcomes in multiple sclerosis. Ann Clin Transl Neur. 2018;5:1478–1491. doi: 10.1002/acn3.638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhan A, Jacobsen C, Myhr KM, et al. Neurofilaments and 10-year follow-up in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2018;24:1301–1307. doi: 10.1177/1352458518782005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manouchehrinia A, Stridh P, Khademi M, et al. Plasma neurofilament light levels are associated with risk of disability in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2020;94:e2457–e2467. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thebault S, Abdoli M, Fereshtehnejad SM, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain predicts long term clinical outcomes in multiple sclerosis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:10381. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67504-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leppert D, Kuhle J. Blood neurofilament light chain at the doorstep of clinical application. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2019;6(5):e599. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aloizou AM, Liampas I, Provatas A, et al. Baseline neurofilament levels in cerebrospinal fluid do not correlate with long-term prognosis in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;64:103940. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2022.103940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Revendova K, Starvaggi Cucuzza C, Manouchehrinia A, et al. Demographic and disease-related factors impact on cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament light chain levels in multiple sclerosis. Brain Behav. 2023;13:e2873. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yik J, Becquart P, Gill J, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain correlates with myelin and axonal magnetic resonance imaging markers in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;57:103366. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2021.103366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sotirchos ES, Fitzgerald K, Singh C, et al. Associations of sNfL with clinico-radiological measures in a large MS population. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2023;10:84–97. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Szilasiová J, Mikula P, Rosenberger J, et al. Plasma neurofilament light chain levels are predictors of disease activity in multiple sclerosis as measured by four-domain NEDA status, including brain volume loss. Mult Scler. 2021;27:2023–2030. doi: 10.1177/1352458521998039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steffen F, Uphaus T, Ripfel N, et al. Serum neurofilament identifies patients with multiple sclerosis with severe focal axonal damage in a 6-year longitudinal cohort. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2022;10(1):e200055. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000200055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seiberl M, Feige J, Hilpold P, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain as biomarker for cladribine-treated multiple sclerosis patients in a real-world setting. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;17(24):4067. doi: 10.3390/ijms24044067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walo-Delgado PE, Sainz de la Maza S, Villarrubia N, et al. Low serum neurofilament light chain values identify optimal responders to dimethyl fumarate in multiple sclerosis treatment. Sci Rep. 2021;11:9299. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88624-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uher T, Havrdova E, Benkert P, et al. Measurement of neurofilaments improves stratification of future disease activity in early multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2021;27:2001–2013. doi: 10.1177/13524585211047977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brune S, Høgestøl E, de Rodez BS, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain concentration predicts disease worsening in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J. 2022;28:1859–1870. doi: 10.1177/13524585221097296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Buchmann A, Pirpamer L, Pinter D, et al. High serum neurofilament light chain levels correlate with brain atrophy and physical disability in multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2023;30:1389–1399. doi: 10.1111/ene.15742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lie I, Kaçar S, Kristin Wesnes K, et al. Serum neurofilament as a predictor of 10-year grey matter atrophy and clinical disability in multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2022;93:849–857. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2021-328568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uphaus T, Steffen F, Muthuraman M, et al. NfL predicts relapse-free progression in a longitudinal multiple sclerosis cohort study. EBioMedicine. 2021;72:103590. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tsagkas C, Naegelin Y, Amann M, et al. Central nervous system atrophy predicts future dynamics of disability progression in a real-world multiple sclerosis cohort. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28:4153–4166. doi: 10.1111/ene.15098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lokhande H, Rosso M, Tauhid S, et al. Serum NfL levels in the first five years predict 10-year thalamic fraction in patients with MS. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2022 doi: 10.1177/20552173211069348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Williams T, Heslegrave A, Zetterberg H, et al. The prognostic significance of early blood neurofilament light chain concentration and magnetic resonance imaging variables in relapse-onset multiple sclerosis. Brain Behav. 2022;12:e2700. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bhan A, Jacobsen C, Dalen I, et al. CSF neurofilament light chain predicts 10-year clinical and radiologic worsening in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2021 doi: 10.1177/20552173211060337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Calabresi PA, Arnold D, Sangurdekar D, et al. Temporal profile of serum neurofilament light in multiple sclerosis: Implications for patient monitoring. Mult Scler. 2021;27:1497–1505. doi: 10.1177/1352458520972573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Voskuhl R, Jens Kuhle J, Siddarth P, et al. Decreased neurofilament light chain levels in estriol-treated multiple sclerosis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2022;9:1316–1320. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harris S, Comi G, Cree BAC, et al. Plasma neurofilament light chain concentrations as a biomarker of clinical and radiologic outcomes in relapsing multiple sclerosis: post hoc analysis of phase 3 ozanimod trials. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28:3722–3730. doi: 10.1111/ene.15009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ashkar A, Ali Baig MM, Arif A, et al. Prognostic significance of neurofilament light in fingolimod therapy for multiple sclerosis: a systemic review and meta-analysis based on randomized control trials. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2023;69:104416. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2022.104416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu N, Sun M, Zhang W, et al. Prognostic value of neurofilament light chain in natalizumab therapy for different phases of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Neurosci. 2022;101:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2022.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Paolicelli D, Ruggieri M, Alessia Manni A, et al. Real-life experience of the effects of cladribine tablets on lymphocyte subsets and serum neurofilament light chain levels in relapsing multiple sclerosis patients. Brain Sci. 2022;12:1595. doi: 10.3390/brainsci12121595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Masanneck L, Rolfes L, Regner-Nelke L, et al. Detecting ongoing disease activity in mildly affected multiple sclerosis patients under first-line therapies. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;63:103927. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2022.103927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kuhle J, Daizadeh N, Benkert P, et al. Sustained reduction of serum neurofilament light chain over 7 years by alemtuzumab in early relapsing-remitting MS. Mult Scler. 2022;28:573–582. doi: 10.1177/13524585211032348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Disanto G, Ripellino P, Riccitelli G, et al. De-escalating rituximab dose results in stability of clinical, radiological, and serum neurofilament levels in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2021;27:1230–1239. doi: 10.1177/1352458520952036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Johnsson M, Farman H, Blennow K, et al. No increase of serum neurofilament light in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients switching from standard to extended-interval dosing of natalizumab. Mult Scler. 2022;28:2070–2080. doi: 10.1177/13524585221108080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kuhle J, Disanto G, Lorscheider J, et al. Fingolimod and CSF neurofilament light chain levels in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2015;84:1639–1643. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Benkert P, Meier S, Schaedelin S, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain for individual prognostication of disease activity in people with multiple sclerosis: a retrospective modelling and validation study. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21:246–257. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wiiliams T, Zetterberg H, Chataway J. Neurofilaments in progressive multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. J Neurol. 2021;268:3212–3222. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09917-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barro C, Healy BC, Saxena S, et al. Serum NfL but not GFAP predicts cognitive decline in active progressive multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler. 2023;29:206–211. doi: 10.1177/13524585221137697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jakimovski D, Zivadinov R, Ramanthan M, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain level associations with clinical and cognitive performance in multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal retrospective 5-year study. Mult Scler. 2020;26:1670–1681. doi: 10.1177/1352458519881428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cruz-Gomez AJ, Forero L, Lozano-Soto E, et al. Cortical thickness and serum nfl explain cognitive dysfunction in newly diagnosed patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2021;8:e1074. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000001074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brummer T, Muthuraman M, Steffen F, et al. Improved prediction of early cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis combining blood and imaging biomarkers. Brain Commun. 2022 doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcac153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Williams T, Tur C, Eshaghi A, et al. Serum neurofilament light and MRI predictors of cognitive decline in patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: analysis from the MS-STAT randomised controlled trial. Mult Scler. 2022;28:1913–1926. doi: 10.1177/13524585221114441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wong YYM, Bruijstens AL, Barro C, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain in pediatric MS and other acquired demyelinating syndromes. Neurology. 2019;93:e968–e974. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wendel EM, Bertolini A, Kousoulos L, et al. Serum neurofilament light-chain levels in children with monophasic myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-associated disease, multiple sclerosis, and other acquired demyelinating syndrome. Mult Scler. 2022;28:1553–1561. doi: 10.1177/13524585221081090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Reinert MC, Benkert P, Wuerfel J, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain is a useful biomarker in pediatric multiple sclerosis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2020;7:e749. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ziaei A, Nasr Z, Hart J, et al. High serum neurofilament levels are observed close to disease activity events in pediatric-onset MS and MOG antibody-associated diseases. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2023;74:104704. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2023.104704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kuhle J, Chitnis T, Banwell B, et al. Plasma neurofilament light chain in children with relapsing MS receiving teriflunomide or placebo: a post hoc analysis of the randomized TERIKIDS trial. Mult Scler. 2023;29:385–394. doi: 10.1177/13524585221144742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ghezzi A, Baroncini D, Zaffaroni M, et al. Pediatric versus adult MS: similar or different? Mult Scler Demyelinating Disord. 2017;2:5. doi: 10.1186/s40893-017-0022-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kerbrat A, Aubert-Broche B, Fonov V, et al. Reduced head and brain size for age and disproportionately smaller thalami in child-onset MS. Neurology. 2012;78:194–201. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318240799a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Weier K, Fonov V, Aubert-Broche B, Arnold DL, Banwell B, Collins DL. Impaired growth of the cerebellum in pediatric-onset acquired CNS demyelinating disease. Mult Scler. 2016;22:1266–1278. doi: 10.1177/1352458515615224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chabas D, Castillo-Trivino T, Mowry EM, et al. Vanishing MS T2-bright lesions before puberty: a distinct MRI phenotype? Neurology. 2008;71:1090–1093. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000326896.66714.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ghassemi R, Narayanan S, Banwell B, et al. Quantitative determination of regional lesion volume and distribution in children and adults with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e85741. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Waubant E, Chabas D, Okuda DT, et al. Difference in disease burden and activity in pediatric patients on brain magnetic resonance imaging at time of multiple sclerosis onset vs adults. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:967. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Renoux C, Vukusic S, Mikaeloff Y, et al. Natural history of multiple sclerosiswith childhood onset. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2603–2613. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chitnis T, Aaen G, Belman A, et al. Improved relapse recovery in paediatric compared to adult multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2020;143:2733–2741. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Portaccio E, Bellinvia A, Razzolini L, et al. Long-term cognitive outcomes and socioprofessional attainment in people with multiple sclerosis with childhood onset. Neurology. 2022;98:e1626–e1636. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tortorella P, Rocca MA, Mezzapesa D, et al. MRI quantification of gray and white matter damage in patients with early-onset multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2006;253:903–907. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rocca MA, Absinta M, Ghezzi A, et al. Is a preserved functional reserve a mechanism limiting clinical impairment in pediatric MS patients? Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30:2844–2851. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.De Meo E, Filippi M, Trojano M, et al. Comparing natural history of early and late onset pediatric multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2022;91:483–495. doi: 10.1002/ana.26322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Baroncini D, Zaffaroni M, Moiola L, et al. Long-term follow-up of pediatric MS patients starting treatment with injectable first-line agents: a multicentre, Italian, retrospective, observational study. MSJ. 2019;25:399–407. doi: 10.1177/1352458518754364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Giovannoni G. Peripheral blood neurofilament light chain levels: the neurologist’s C-reactive protein? Brain. 2018;141:2235–2237. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]