Abstract

Early sexual intercourse is associated with sexually transmitted infections, pregnancy, and depressive symptoms, and delay of intercourse allows adolescents opportunities to practice relationship skills (Coker et al., 1994; Kugler et al., 2017; Spriggs & Halpern, 2008; Harden, 2012). Thus, understanding predictors of early sexual intercourse is crucial. Prior research has suggested that violence exposure is associated with early initiation of sexual intercourse in adolescence (Abajobir et al., 2018; Orihuela et al., 2020). However, most studies have looked only at a single type of violence exposure. In addition, little research has examined longitudinal patterns of violence exposure in order to determine whether there are particular periods when the violence exposure may have the strongest impact on sexual behavior. Guided by life history and cumulative disadvantage theories, we use longitudinal latent class analysis and data from the Future of Families and Child Well-being Study (N = 3,396; 51.1% female, 48.9% male) to examine how longitudinal patterns of multiple types of violence exposures across ages 3 to 15 are associated with early sexual initiation in adolescence. Findings suggest that experiencing persistent physical and emotional abuse across childhood is associated with the greatest prevalence of early sexual initiation. Early exposure to violence was not consistently associated with greater likelihood of sexual initiation; instead, early abuse was more strongly associated with sexual initiation for boys, while late childhood abuse was more strongly associated for girls. These findings suggest that gender-sensitive programs are highly needed to address unique risk factors for boys and girls’ sexual behaviors.

Keywords: violence exposure, adolescent sexual behavior, latent class analysis

INTRODUCTION

Engaging in early sexual intercourse relative to peers (defined as before between ages 13 to 16, depending on the study) is associated with a number of negative health outcomes, including sexually transmitted infections, pregnancies, and higher depressive symptoms in adolescence (Coker et al., 1994; Kaestle et al., 2005; Kugler et al., 2017; Meier 2007; Spriggs & Halpern, 2008; Vasilenko et al., 2016). Delaying early sexual intercourse also helps adolescents to practice relationship skills to gain better romantic relationship experiences (Harden, 2012) and avoid negative impacts on school performance due to challenges in romantic relationships (McCarthy & Grodsky, 2011). Thus, a major goal of many sexuality education programs is the delay of first intercourse (Chin et al., 2012; Kirby, 2007). Gaining a better understanding of what childhood risk factors are associated with sexual behavior can help researchers develop interventions that are tailored and targeted to those at greatest risk. Prior research has suggested that exposure to violence is one factor that is associated with early sexual initiation and other risky sexual behavior in adolescence (Abajobir et al., 2018; Tsuyuki et al., 2019; Wilson et al., 2012; Wilson & Widom, 2008). However, prior research on this topic has been limited by not examining the concurrent impact of multiple types of violence exposure or the impact of the timing of violence exposure. Thus, in this study we applied longitudinal latent class analysis to four waves of data from the U.S. the Future of Families and Child Well-being Study to examine how longitudinal patterns of multidimensional violence exposure across ages 3-15 are associated with early initiation of sexual intercourse in adolescence.

Theoretical Framework

Several theoretical frameworks suggests ways in which violence exposure may be associated with early sexual initiation. For example. Life History Theory (LHT) is one theoretical perspective that can be used to explain potential associations between violence exposure and adolescent early sexual initiation. From an evolutionary perspective, LHT posits that humans make trade-offs among competing life functions (e.g., bodily maintenance, growth, and reproduction) due to finite time and energy (Zhang et al., 2022). Given that those life functions cannot be simultaneously maximized, natural selection favors humans who can make the best trade-offs to adapt to their living environments (Zhang et al., 2022). The first 5-7 years of life experience is a critical developmental stage to inform individual’s decision on allocating their limited resources. Violence exposure, such as child maltreatment or family conflicts, conveys a life-course message that the world is unsafe and other people cannot be counted upon (Belsky, 1991). Thus, being reared in a harsh environment makes prioritizing certain life functions an optimal strategy. Specifically, children reared in stressful family context, such as experiencing harsh parenting, tend to develop a fast reproductive strategy featured by early sex debut, more sexual partners, and more offspring. In contrast, individuals raised in a nourished and supportive childhood environment demonstrate the opposite pattern of reproductive strategies, a slow reproductive strategy, to prioritize individual growth before reproduction (Belsky et al., 2012).

Likewise, attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969) provides another foundation linking violence exposure with risky sexual behavior. For example, experiencing family violence (i.e., child maltreatment) results in insecure attachment with caregivers (Pickreign Stronach et al., 2011). According to Bowlby (1969), an insecure attachment with caregivers shapes a specific internal working model reflected by individuals viewing the self as unlovable, others as irresponsive, and interpersonal relationships as unreliable (Bowlby, 1969). Research also suggests that individuals with insecure attachment (e.g., anxious attachment) have low self-esteem (Collins & Feeney, 2004) and a tendency to have early sexual initiation (Paulk & Zayac, 2013).

These theoretical perspectives suggest the importance of early violence exposure in influencing adolescents’ sexual behaviors. According to the LHT, there are several different facets of early stressful environment which may uniquely contribute to individuals’ later developmental outcomes (Ellis et al., 2009). Two important aspects are harshness, which refers to externally caused “levels of morbidity-mortality” and unpredictability or the “spatial-temporal variation in harshness” (Ellis et al., 2009). As evolving mechanisms, children can detect the features of harsh and unpredictable early life rearing environment, based on which they predict the nature of their living conditions into which they will mature and develop strategies to respond to these conditions (Boyce & Ellis, 2005). Specifically, being reared in the harsh and unpredictable environment may condition individuals to predict their future social and physical world as unsafe and resource unavailable in which they may die early, thereby starting sexual initiation as early as possible to maximize the reproduction chances could be the most adaptive strategy (Belsky et al., 2012). Therefore, both harshness and unpredictability are predicted to be associated with a fast reproductive style in which individuals initiate sexual behavior early and engage in behaviors that can be seen as developmentally “risky” but may be “adaptive” in the sense of maximizing reproductive potential in the midst of a difficult and unpredictable environment (Simpson et al., 2012). Thus, LHT would suggest that exposure to harsh violence (e.g., physical violence victimization), as well as unpredictable violence exposure that occurs sporadically during different periods are likely to lead to a fast reproductive strategy marked by early sexual initiation.

However, other theoretical perspectives challenge the idea that early or unpredictable exposure to violence would lead to earlier sexual initiation. For example, cumulative risk theory (Rutter, 1983) suggests that the accumulation of multiple risk factors over time has a dose-dependent association with compromised developmental outcomes. Drawing from this perspective, polyvictimization theory (Finkelhor et al., 2007) suggests that individuals who experience multiple types of violence are more likely to have negative health outcomes. This perspective would suggest that persistent exposure to violence, rather than sporadic or early exposures, would be most likely to lead to early sexual initiation. Empirical studies that make use of longitudinal data are needed to test these two competing theories to deepen the understanding of violence exposure on adolescent sexual behaviors.

Literature Review: Violence Exposure and Sexual Behavior

Prior research has generally supported the LHT suggestion that stressful environments, such as those marked by exposure to violence, are associated with factors characteristic of a fast reproductive style, such as early initiation, more sexual partners, and inconsistent condom use (Tsuyuki et al., 2019; Wilson et al., 2012). Based on a sample of low-income, urban African American adolescent girls, Wilson and colleagues (2012) found neighborhood violence exposure a significant predictor for adolescent girls’ unprotected sex, larger numbers of partners, and inconsistent condom use. Though relatively few studies examine the link between violence exposure and adolescent early sexual initiation, existing research presents solid evidence showing the adverse consequences of child maltreatment histories on adolescent early sexual initiation (Abajobir et al., 2018, Hillis et al., 2001, Wilson & Widom, 2008). Using information from female members of a managed care organization, Hillis et al. (2001) showed that experiencing childhood physical abuse, verbal abuse, sexual abuse, and witnessing mother experiencing domestic violence all significantly increased the chance of early onset of intercourse (<15 years old). Later, Tsuyuki et al.’s study (2010) on Black women seeking public funded STD services in Baltimore suggested that participants’ childhood emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and witnessing maternal abuse were significantly associated with their very early sexual initiation (11-12 years). Finally, based on an Australian birth cohort sample of both men and women, Abajobir et al (2018) found that each type of child maltreatment was significantly associated with early sexual initiation (<15 years old).

Much of the extant research has examined the impact of violence exposure on early sexual initiation in adolescent girls, although some research has suggested that ACEs may be associated with early sexual initiation in both boys and girls (Abajobir et al., 2018) and that there may be differences in how violence exposure differentially impacts boys’ and girls’ health behaviors (Almuneef et al., 2017). For example, there may be stronger associations between experiencing adversity in childhood and mental health outcomes for women compared to men (Haatainen et al., 2003). However, there is relatively little research that has examined gender differences in the impact of violence exposure on early sexual initiation. One study found no significant gender differences in the associations between child maltreatment and early sexual initiation, although maltreatment was more strongly associated with having a larger number of lifetime sexual partners for male compared to female adolescents (Negriff et al., 2015). However, given the limited research, it is important to better understand how violence exposure may differentially impact male and female adolescents’ sexual behaviors. In particular, research that untangles differences in types, timing, and persistence of violence exposure may show gender differences in associations with sexual behavior.

Although prior research has suggested links between multiple types of violence exposure and early sexual initiation, less is known about the effects of the timing of these exposures and the potential effects of different and co-occurring types. In one study that did examine the impact of early versus late exposure to stressful environments, Simpson and colleagues (2012) found that it was the stressful rearing environment during the early 5 years of life, but not ages 6-16, that was significantly associated with having more sexual partners at age 23. However, this study examined socioeconomics (SES) and changes in parent employment, romantic partner, and residence rather than exposure to violence, so it is unclear whether these trends would also emerge in studies of violence exposure. In regard to the effects of different types of violence, although several studies did examine multiple types of violence exposures (e.g., emotional abuse, physical abuse, witnessing maternal abuse; Hillis et al., 2001; Tsuyuki et al., 2018), they used a variable oriented approach in which the impact of each violence exposure is estimated separately (controlling for the others), making it unclear whether particular combinations of exposures would be associated with greater risk. However, understanding the links between different multidimensional patterns of exposures and adolescent sexual behaviors is necessary to answer questions suggested by LHT and cumulative disadvantage theory, such as whether experiencing an accumulation of multiple types of violence exposure is associated with more negative outcomes than experiencing a single, but harsh, type of exposure alone.

A Person-Centered Approach to Violence Exposure

In contrast to variable-centered studies, in which individual predictors are assessed separately, person-centered studies aim to identify different groups of people marked by unique patterns of characteristics, such as the co-occurrence of different types of violence exposure. In recent years, studies have increasingly used person-centered analyses like latent class analysis (LCA) to characterize violence exposure, due to a recognition that multiple types and contexts of violence may have differing effects in different combinations (Clarke et al., 2016; Gaylord-Harden et al., 2015; Siller et al., 2022). However, apart from a few studies that have examined profiles of violence exposure in adolescent perpetrators of sexual violence (e.g., Alexander et al., 2021; Baglivio & Wolff, 2021; Barra et al., 2018), few person-centered studies of violence exposure have examined associations with sexual risk behaviors. One exception is a study by Walsh and colleagues (2012) which examined profiles of violence exposure and their associations with sexual risk behavior among female patients at a sexually transmitted disease clinic. They identified four distinct violence exposure profiles: Low Violence, Predominantly Child Maltreatment, Primarily Exposure to Community Violence, and Multiply Victimized. Women in the Multidimensionally Victimized and Exposure to Community Violence had higher prevalence of multiple sexual risk outcomes (Walsh et al., 2012). This study shows the potential for examining how profiles of violence exposure are associated with sexual behaviors.

In addition, extending latent class analysis to longitudinal data can help researchers determine not only which types of violence exposure are associated with sexual behaviors, but the impact of the timing of these exposures. Longitudinal latent class analysis (LLCA) applies LCA to data collected across multiple waves, in order to identify profiles marked by differing longitudinal patterns on multiple variables (Feldman et al., 2009). In the example of violence exposure, we can examine subgroups of adolescents who were exposed to violence in early childhood, middle childhood, and adolescence to uncover groups marked by early exposure, late exposure, and consistent exposures. This would allow us to test competing theories about the timing, harshness, and unpredictability of violence exposures. For example, if an early exposure class showed a high prevalence of early sexual initiation, this would provide evidence for LHT’s emphasis on the early childhood period. However, a persistent exposure class having high prevalence would be stronger evidence for the cumulative disadvantage and polyvictimization theories.

The Current Study

In the current study we apply LLCA to secondary data from the U.S. national the Future of Families and Child Well-being Study (FFCWS) to examine how longitudinal patterns of violence exposure across childhood are associated with early initiation of sexual behavior in adolescence. We have three primary aims:

To uncover profiles of multidimensional violence exposure (mother physical and emotional IPV, child physical and emotional abuse, neighborhood violence) experienced by children across ages 3, 5, 9, and 15.

To examine demographic predictors of class membership.

To test how longitudinal violence exposure class membership is associated with engaging in early initiation of sexual intercourse (i.e., before age 15 assessment).

To test whether there are gender differences in the association between longitudinal violence exposure latent class membership and early initiation of sexual intercourse.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were from the Future of Families and Child Well-being Study (FFCWS). FFCWS collected data from a longitudinal birth cohort study of parent-child dyads (N = 4,898) in 20 large U.S. cities, starting at the child’s birth and following with waves at ages one, three, five, nine, and 15 years of the child’s age. Because the original research purpose of FFCWS was to understand how non-marital childbearing influences child development, FFCWS oversampled children to unmarried mothers by a ratio of 3 to 1 (see Reichman et al., 2001 for sample design details). This sampling strategy produced a racially diverse study sample (48% Black, 27% Latine, 21% White) that also experienced socioeconomic disadvantage and parental relationship instability. For this analysis, we restricted the sample to individuals who had data on the primary outcome (sexual behavior by the Age 15 assessment) and at least some data on the Age 3-15 violence exposure variables, as LCA uses Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) to account for missingness in LCA indicators. Thus, our analytic sample consisted of 3,396 individuals (51.1% male, 48.9% female; 48.9% black, 25.0% Latine, 18.1% White, 2.7% other race/ethnicity, 5.3% multiracial; Mchildage3 = 2.96, SD = 0.20, Mchildage15 = 15.59, SD = 2.43; Mmotherage3 = 28.11, SD = 6.01).

Measures

We used data primarily from the Age 3, 5, 9, and 15 assessments. These were based on both parent and child reports. Recoding was performed using R 4.1 (R Development Core Team, 2017).

Longitudinal Exposure to Violence Indicators

We included measures of four types of violence, most of which were measured at all four waves of interest.

Mother Physical IPV.

We included four items that were developed for the FFCWS to measure mother physical IPV for waves of age three, five, and nine: “How often father slaps or kicks you?” “How often current partner slaps or kicks you?” “How often does father hit you with a fist or an object that could hurt you?” “How often does current partner hit you with a fist or an object that could hurt you?” Mothers were responded as “often,” “sometimes,” and “never.” We coded the value of the indicator of mother physical IPV as 1 if mothers reported “often” or “sometimes” for any of the four items. In the wave of age 15, we used only one item “had physical fight with spouse/partner in front of youth in past year?” to measure mother physical IPV. We coded the indicator of mother physical IPV at age 15 as 1 if the mother’s response was “yes.”

Mother Emotional IPV.

We included two items that were developed for the FFCWS for assessing mother emotional IPV for the wave of age three: “How often does father insult or criticize you or your ideas?” “How often does current partner insult or criticize you?” In the waves of ages five and nine, two items were included in addition to those two items: “how often father insult or criticize you for not taking good care of child/home?” “How often does current partner insult or criticize you for not taking good care of child/home?” The indicator of mother emotional IPV was coded as 1 if the mother’s responses were “often” and “sometimes,” and 0 if “never” was the response. This construct was not measured in the wave of age 15.

Physical Abuse by Parent.

We included five items from the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scale (PC-CTS; Straus et al., 1998) to measure physical abuse by parents in the waves of ages three, five, and nine: “How many times in the past year did primary caregiver shook child?” “How many times in the past year did primary caregiver hit child on the bottom with belt or hard object?” “How many times in the past year did primary caregiver spank child on bottom with care hand?” “How many times in the past year did primary caregiver slap child on the hand, arm, or leg?” “How many times in the past year did primary caregiver pinch child?” The primary caregivers’ responses were “never,” twice, “3-5 times,” “6-10 times,” “11-20 times,” “more than 20 times.” We first recoded the responses by the midpoint of the frequency (e.g., recoded 6-10 times as 8 times) as recommended by the scale developer (Straus et al., 1998). We then summed up the frequencies of those five items and identified participants whose scores of frequencies were high in top 10 percentile of the entire study sample, consistent with coding in prior work (e.g., Jimenez et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020). For those cases, we assigned the value of 1 to the indicator of physical abuse by parent because their behaviors could be viewed as extremely harsh parenting. The remaining participants were assigned with the value of 0 for this indicator. For the wave of age 15, we used one question “did your primary caregivers hit or slap you” that reported by youth themselves to measure physical abuse by parent. We coded the indicator of physical abuse by parent at age 15 as 1 when the response was “yes,” and 0 if the response was “no.”

Emotional Abuse by Parent.

We included five items also from the PC-CTS to measure emotional abuse by parent in the waves of ages three, five, and nine: “How many times in the past year did primary caregiver shout, yell, or scream at child?” “How many times in the past year did primary caregiver swear or curse at child?” “How many times in the past year did primary caregiver say they would send child away or kick out of house?” “How many times in the past year did primary caregiver threaten to spank/hit child but did not?” “How many times in the past year did primary caregiver call child dumb or lazy or similar name?” Followed the same way we coded the indicator of physical abuse by parent, for the indicator of emotional abuse by parent, we assigned the value of 1 to participants whose scores of frequencies of emotional abuse as high in top 10 percentile of the entire study sample and the remaining participants would be assigned with the value of 0. For the wave of age 15, we used one question “did parents shout or swear at youth in past year”. The indicator of emotional abuse by parents at age 15 was coded as 1 if the response was “yes” and 0 if the response was 0.

Neighborhood Violence.

Neighborhood violence was measures through a series of questions that were developed for the FFCWS. We used one question “How often does gang activity happen” reported by primary caregivers in the wave of age three to measure neighborhood violence. The indicator was coded as 1 when participants reported “rarely,” “sometimes,” and “frequently.” We coded 0 for the neighborhood violence at age 3 if the response was “never.” During waves of ages five and nine, we used two questions “Have you ever been afraid to let child go outside because of violence in your neighborhood?” “Gangs are a problem in this neighborhood?” The indicators of neighborhood violence at ages five and nine were coded as 1 if either the response of the first question was “Yes” or the responses of the second question was “strongly agree” or “agree.” In the wave of age 15, we included two questions reported by youth themselves in addition to those two questions from waves of ages five and nine: “I feel unsafe walking around my neighborhood during the day.” “I feel unsafe walking around my neighborhood at night.” The indicator of neighborhood violence at age 15 was coded as 1 if either primary caregiver responded that they “were afraid to let youth outside because of neighborhood violence”, or youth reported that “they strongly agree or agree that gangs are a problem in this neighborhood,” or youth reported that they strongly agree or somewhat agree or somewhat disagree that “I feel unsafe walking around my neighborhood during the day” or “I feel unsafe walking around my neighborhood during the night.”

Correlates of Class Membership

We included six variables as predictors of latent class membership and as controls in the model with violence latent classes predicting sexual intercourse. Child race was from an Age 15 assessment that indicated whether the child identified as Black, White, Hispanic/Latino, Other race, or mixed race. Child gender indicated whether the child was a boy or girl, reported at birth. Mother Poverty was assessed with an indicator the mother's self-report of the total household income, further divided by that year’s official federal poverty threshold with consideration of family size. FFCWS originally coded this variable as the following categories: 1 = 0 – 49%, 2 = 50 – 99%, 3 = 100 – 199%, 4 = 200 – 299%, and 5 = 300%+. In the current study, we combined the first three categories to reflect the “poor” groups and the fourth and fifth categories as “non-poor groups”, consistent with prior research (e.g., Burchinal et al., 2008). Marital Status was a measure of whether the mother was married or single, self-reported at baseline. Mother Age at Age 3 wave indicated how old the mother was during the child Age 3 assessment. Child Age at Age 15 wave indicated how old the child was at the Age 15 assessment.

Outcome: Sexual Intercourse by Age 15 Assessment

Our outcome was a dichotomous measure of whether or not participants reported ever engaging in sexual intercourse in the Age 15 assessment, as this is currently the only adolescent wave in FFCW and the only wave in which information on sexual behavior was collection. However, sexual intercourse by age 15 is consistent with definitions of early sexual intercourse occurring before age 16 used in other studies (e.g., Spriggs & Halpern, 2008; Vasilenko et al., 2016). This was derived from two items. The first asked participants who had reported being in a romantic relationship whether they had engaged in sexual intercourse with this current partner. The second asked participants who did not report a current partner or who had not had sex with this romantic partner whether they had engaged in sexual intercourse with anyone in their lifetime. Participants were coded as ever having intercourse if they reported sex with a current partner or any partner (21.2%, N = 720).

Analytic Plan

Our analysis proceeded in three steps. First, we modeled classes of longitudinal violence exposure using Latent Gold 5.1 (Vermunt & Magidson, 2015). We ran models with 1-10 classes and selected the model with the optimal number of latent classes based on information criteria (AIC: Akaike Information Criterion and BIC: Bayesian Information Criterion) and interpretability. Second, we examined correlates of class membership using the 3-step command that implements the BCH approach (Bolck et al., 2004). This method weights analyses by each individuals’ probability of being in a given latent class, which provides less biased results than classify-analyze approaches (Bolck et al., 2004; Vermunt, 2010). We first used this approach to examine the prevalence of membership in each latent class by child race/ethnicity, child gender, mother poverty, parents married, mother age, and child age by running a 3-step model with the Covariate analysis option. Analyses of the effects of these factors on class membership use a latent class probability-weighted multinomial regression model, which examines how each predictor is associated with membership in a particular class compared to a reference group. Third, we examined how latent class membership was associated with sexual intercourse by the age 15 waves using the BCH approach with the Dependent analysis option, controlling for demographic covariates. Finally, we added an interaction term to our BCH analysis in described in step 3 in order to test whether there are gender differences in the association between violence exposure latent class membership and early sexual intercourse.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents fit statistics for the 1-10 class models of longitudinal violence exposure. The BIC suggested a 4-class model, while the AIC continued to get smaller through the 10-class model. The BLRT also was significant through models with 10-classes. Due to the conflicting fit statistics, as well as our desire to choose an interpretable model that uncovers conceptually distinct classes across different ages, we further examined and attempted to interpret the 4 through 10 class models. Based on the interpretation of the classes, we selected the 9-class model, as it had conceptually distinct classes that were important to understanding our theoretical questions (e.g., child abuse occurring at different ages, a persistent abuse class, etc).

Table 1.

Fit Statistics for LCA Models of Longitudinal Exposure to Violence

| # of Classes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| BIC | AIC | BLRT | |

| 1 | 45380.48 | 45264.00 | <.001 |

| 2 | 44167.13 | 43928.05 | <.001 |

| 3 | 43723.19 | 43361.50 | <.001 |

| 4 | 43531.99 | 43047.69 | <.001 |

| 5 | 43569.05 | 42962.14 | <.001 |

| 6 | 43609.42 | 42879.91 | <.001 |

| 7 | 43655.66 | 42803.54 | <.001 |

| 8 | 43739.34 | 42764.62 | <.001 |

| 9 | 43812.19 | 42714.86 | <.001 |

| 10 | 43912.18 | 42692.24 | <.001 |

Note. AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion; BLRT = Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test. The selected class is in bold.

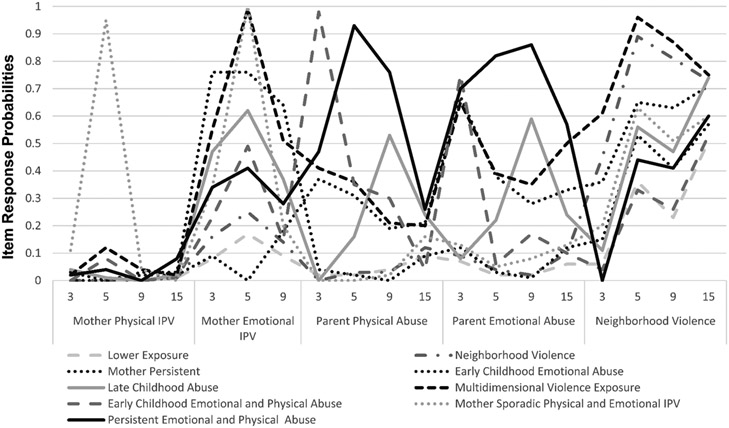

Item-response probabilities for the nine-class model are presented in Table 2 and Figure 1. Note that all classes had relatively high probabilities of neighborhood violence exposure at most ages, likely due to the nature of this higher-risk sample. Thus, all classes can be seen as high neighborhood violence exposure classes, and to create more short and conceptually distinct class names, we only include neighborhood violence exposure in the class names when it results in a distinct interpretation (e.g., a class marked by neighborhood violence and no other types of violence exposures) and focus our interpretation on the other types of violence exposure indicators. The largest class, Lower Exposure (Class 1; 34.79%), was made up of individuals with a low probability of all violence exposures, with the exception of relatively high (but lower than the sample average) neighborhood violence at Age 15. The Neighborhood Violence (Class 2; 23.76%) class was marked by high probabilities of neighborhood violence at all ages, but low probabilities of all other types of violence exposure. Mother Persistent Emotional IPV (Class 3; 14.34%) was marked by high probabilities of the mother reporting emotional IPV victimization at all waves, with low probabilities of all other exposures, with the exception of moderate probabilities of neighborhood violence. Early Childhood Emotional Abuse (Class 4; 9.34%) was marked by a much higher probability of both physical and emotional abuse victimization at age 3, which declined over time. Late Childhood Abuse (Class 5; 6.01%) was marked by high probabilities of physical and emotional abuse victimization at age 9. Multidimensional Violence Exposure (Class 6; 3.67%) was marked by high probabilities of mother emotional IPV victimization and neighborhood violence at all ages. In addition, this class was marked by relatively high probabilities of physical and emotional abuse, which were highest at ages 3 and 5. Early Childhood Emotional and Physical Abuse (Class 7; 3.2%) was marked by high probabilities of both physical and emotional abuse victimization at age 3. Mother Sporadic Physical and Emotional IPV (Class 8; 2.68%) was marked by a high probability of mother physical and emotional IPV victimization at child age 5. Finally, Persistent Emotional and Physical Abuse (Class 9; 2.2%), was marked by relatively high probabilities of child physical and emotional abuse victimization at all ages.

Table 2.

Item Response Probabilities for Nine Class Latent Class of Longitudinal Violence Exposure

| Overall | 1. Lower Exposure (34.79%) |

2. Neighborhood Violence (23.76%) |

3. Mother Persistent Emotional IPV (14.34%) |

4. Early Childhood Emotional Abuse (9.34%) |

5. Late Childhood Abuse (6.01%) |

6. Multi- dimensional Violence Exposures (3.67%) |

7. Early Childhood Emotional and Physical Abuse (3.2%) |

8. Mother Sporadic Physical and Emotional IPV (2.68%) |

9. Persistent Emotional and Physical Abuse (2.2%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother Physical IPV | ||||||||||

| Age 3 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.02 |

| Age 5 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.95 | 0.04 |

| Age 9 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| Age 15 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.08 |

| Mother Emotional IPV | ||||||||||

| Age 3 | 0.26 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.76 | 0.09 | 0.47 | 0.55 | 0.23 | 0.34 | 0.34 |

| Age 5 | 0.35 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.76 | 0.00 | 0.62 | 0.99 | 0.49 | 1.00 | 0.41 |

| Age 9 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.64 | 0.18 | 0.37 | 0.51 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.28 |

| Physical Abuse | ||||||||||

| Age 3 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 0.41 | 0.98 | 0.00 | 0.47 |

| Age 5 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.31 | 0.16 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 0.93 |

| Age 9 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.53 | 0.21 | 0.30 | 0.02 | 0.76 |

| Age 15 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.26 |

| Emotional Abuse | ||||||||||

| Age 3 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.67 | 0.08 | 0.65 | 0.75 | 0.13 | 0.70 |

| Age 5 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.38 | 0.22 | 0.39 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.82 |

| Age 9 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.59 | 0.35 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.86 |

| Age 15 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.24 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.57 |

| Neighborhood Violence | ||||||||||

| Age 3 | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.45 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.11 | 0.61 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.00 |

| Age 5 | 0.58 | 0.36 | 0.89 | 0.53 | 0.65 | 0.56 | 0.96 | 0.33 | 0.63 | 0.44 |

| Age 9 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0.81 | 0.41 | 0.63 | 0.47 | 0.87 | 0.26 | 0.51 | 0.41 |

| Age 15 | 0.62 | 0.51 | 0.73 | 0.57 | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.53 | 0.60 | 0.60 |

Note. Item response probabilities greater than .50 in bold to facilitate interpretation.

Figure 1.

Item response probabilities for 9-class model of longitudinal violence exposure.

Table 3 shows probabilities of being in each class by demographic characteristics (categorical variables) and the mean ages within each class for the mother and child age variables. Overall χ2 tests were significant for all demographic predictors, apart from child age. White participants were most likely to be in the Lower Exposure class, whereas Black and Latine participants were about equally likely to be in the Lower Exposure and Neighborhood Violence classes. More female than male participants were in the Mother Persistent Emotional IPV class, with more male than female in the Early Childhood Emotional and Physical Abuse class. Participants with mothers not in poverty were more likely to be in the Lower Exposure and Mother Persistent Emotional IPV class, and less likely to be in the Neighborhood violence, Early Childhood Emotional Abuse, and Late Childhood Abuse classes. Children with parents who were nor married were overrepresented in the Neighborhood Violence, and Early Childhood Emotional Abuse classes and underrepresented in the Lower Exposure and Mother Persistent Emotional IPV classes. Mothers in the Mother Persistent Emotional IPV class had the highest mean age, and those in the Persistent Emotional and Physical Abuse class had the lowest mean age at Child Age 3. Child Age at the Age 15 waves was not a significant predictor of class membership; however, it was also included as a control in subsequent models because prevalence of sexual behavior increases with age across adolescence (Vasilenko, 2017).

Table 3.

Demographic Characteristics of Latent Classes of Longitudinal Violence Exposure

| 1. Lower Exposure |

2. Neighborhood Violence |

3. Mother Persistent Emotional IPV |

4. Early Childhood Emotional Abuse |

Late Childhood Abuse |

Multi- dimensional Violence Exposures |

Early Childhood Emotional and Physical Abuse |

Mother Sporadic Physical and Emotional IPV |

Persistent Emotional and Physical Abuse |

χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Race | ||||||||||

| White | 0.57 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 5340171*** |

| Black | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| Latine | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | |

| Other | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.31 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.00 | |

| Multiracial | 0.30 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 | |

| Child Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 25.57** |

| Female | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | |

| Mother Poverty | ||||||||||

| Poor | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 109.40*** |

| Not Poor | 0.44 | 0.09 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| Marital Status | ||||||||||

| No | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 122.27*** |

| Yes | 0.43 | 0.06 | 0.30 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.01 | |

| Mother Age | 28.55 | 26.94 | 31.31 | 26.13 | 27.40 | 27.70 | 26.59 | 28.21 | 25.55 | 99.56*** |

| Child Age | 15.57 | 15.69 | 15.61 | 15.59 | 15.41 | 15.50 | 15.54 | 15.50 | 15.53 | 13.81 |

Note. For categorical variables, values indicate the probability of being in a particular latent class for each subgroup. For continuous items, values indicate the mean for individuals in a given latent class.

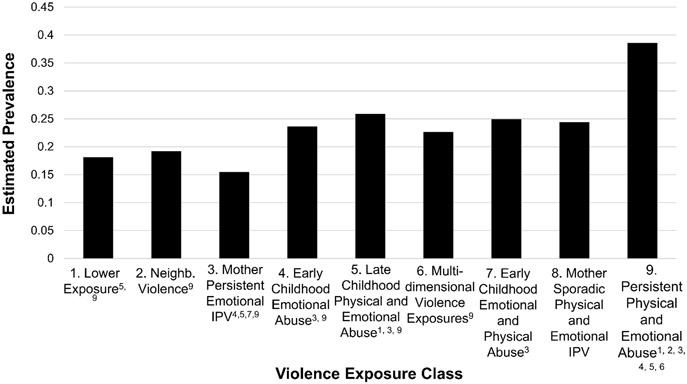

Table 4 presents results of a class membership-probability weighted model examining how violence exposure class membership was associated with sexual intercourse at Age 15 wave, controlling for demographic characteristics. The overall χ2 test for class membership was significant, suggesting that odds of initiating intercourse differed by latent class. Figure 2 shows estimated prevalence of sexual intercourse by class, as well as results of post hoc tests indicating which classes had significantly differing prevalences. Individuals in the Persistent Physical and Emotional Abuse class had the highest prevalence of sexual intercourse (38.6%), which differed significantly from most other classes (i.e., Lower Exposure, Neighborhood Violence, Mother Persistent IPV, Early Childhood Emotional Abuse, Late Childhood Abuse, and Multidimensional Violence Exposures), which had prevalences of sexual intercourse ranging from about 15-25%. The second highest prevalence was in the Late Childhood Physical and Emotional Abuse class (25.9%), which was significantly higher than the Lower Exposure (18.1%) and Mother Persistent Emotional IPV classes (15.5%), but lower than the Persistent Physical and Emotional Abuse class (38.6%). The lowest prevalence was the Mother Persistent Emotional IPV class (15.5%), which was significantly lower than the Early Childhood Emotional Abuse (23.6%), Late Childhood Physical and Emotional Abuse (25.9%), Early Childhood Emotional and Physical Abuse (24.9%), and Persistent Physical and Emotional Abuse (38.6%) classes. The second lowest prevalence was in the Lower Violence Exposure class (18.1%), which differed from the Late Childhood Physical and Emotional Abuse (25.9%) and the Persistent Physical and Emotional Abuse (38.6%) classes.

Table 4.

Violence Exposure Class Membership Predicting Engaging in Sex by Age 15 Wave

| Main Effect | Gender Interaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | χ 2 | OR | χ 2 | |

| Intercept | 0.00 | 283.01*** | 0.00 | 271.11*** |

| Class Membership | 24.69** | 17.22* | ||

| Neighborhood Violence | 1.09 | 0.98 | ||

| Mother Persistent Emotional IPV | 0.79 | 0.75 | ||

| Early Emotional Childhood Abuse | 1.53 | 1.56 | ||

| Late Childhood Abuse | 1.78 | 1.13 | ||

| Multidimensional Violence Exposures | 1.42 | 1.59 | ||

| Early Childhood Emotional and Physical Abuse | 1.67 | 2.37 | ||

| Mother Sporadic Physical and Emotional IPV | 1.61 | 0.98 | ||

| Persistent Emotional and Physical Abuse | 3.80 | 3.25 | ||

| Child Race | 29.11*** | 28.90*** | ||

| Black | 1.47 | 1.49 | ||

| Latine | 0.79 | 0.73 | ||

| Other | 0.61 | 0.70 | ||

| Multiracial | 1.67 | 1.71 | ||

| Child Gender (Female) | 0.38 | 79.68*** | 0.29 | 19.67*** |

| Mother SES (Not Poor) | 0.56 | 20.52*** | 0.55 | 18.02*** |

| Parent Marriage | 0.50 | 21.48*** | 0.48 | 20.08*** |

| Mother Age | 1.02 | 4.52* | 1.01 | 1.42 |

| Child Age | 3.30 | 271.19*** | 5.53 | 268.41*** |

| Class Membership | 15.51* | |||

| Neighborhood Violence X Gender | 1.22 | |||

| Mother Persistent Emotional IPV X Gender | 1.04 | |||

| Early Emotional Childhood Abuse X Gender | 1.00 | |||

| Late Childhood Abuse X Gender | 3.61 | |||

| Multidimensional Violence Exposures X Gender | 0.88 | |||

| Early Childhood Emotional and Physical Abuse X Gender | 0.10 | |||

| Mother Sporadic Physical and Emotional IPV X Gender | 5.24 | |||

| Persistent Emotional and Physical Abuse X Gender | 1.84 | |||

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Figure 2.

Estimated prevalence of sexual intercourse by Age 15 assessment by longitudinal violence exposure latent class. Superscripts after each class name indicate classes that are significantly different from this class.

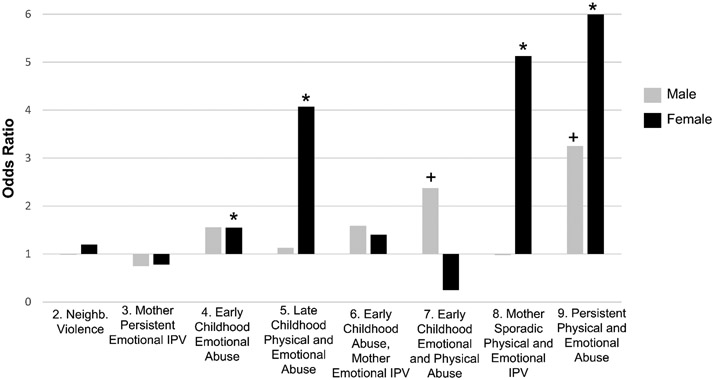

Finally, we examined gender differences in the association between class membership and early sexual intercourse (Table 4). The overall χ2 test for class membership and for the gender interaction were significant, suggesting that odds of initiating intercourse differed by latent class, and these associations differed by gender. Figure 3 presents estimated odds ratios derived from this model that show the change in odds of early sexual intercourse for individuals in a given latent class compared to the reference (Lower Exposure) class, by gender. Odds ratios for male participants were generally higher than for female in classes marked by early abuse. For example, male participants in the Early Childhood Physical and Emotional Abuse class had 2.4 times greater odds of engaging in sexual intercourse compared to those in the lower exposure class; this difference was not significant for female adolescents. In contrast, odds ratios were higher for female participants in classes marked by late childhood abuse and early mother physical IPV. For example, female adolescents in the Late Childhood Physical and Emotional Abuse class had 4.1 times greater odds of engaging in sexual intercourse compared to adolescent girls in the Lower Exposure class; there was no significant difference between these two classes for male adolescents. Similarly, female adolescents in the Mother Sporadic Physical and Emotional IPV class had 5.1 greater odds of sexual intercourse than those in the Lower Exposure class, and there were no significant differences between these classes for male adolescents. However, for both male and female adolescents, individuals in the Persistent Physical and Emotional Abuse class were the most likely to engage in sexual intercourse, thought the associations were stronger for female adolescents. Female adolescents in this class were 6 times more likely to have engaged in sexual intercourse compared to the Lower Exposure class, whereas male adolescents in the this class had 3.25 times greater odds compared to the Lower Exposure class.

Figure 3.

Odds ratios representing the difference in odds of early sexual intercourse for individuals in a given latent class compared to the reference group (lower exposure). + indicates a significant difference between the given class and the reference group for males. * indicates a significant difference between the given class and the reference group for females.

DISCUSSION

Using a person-centered approach, this study identified nine distinctive pattens of longitudinal violence exposure and examined how these different patterns of violence exposure were associated with adolescent early sexual initiation in a high-risk population. Our findings suggested that participants in the lower violence exposure, marked by low probabilities of violence exposure, had a relatively low prevalence of sexual initiation, compared to other classes, whereas several classes marked by violence exposure had higher prevalence. These findings are broadly supportive of LHT, which suggests that individuals’ reproductive strategy could be profoundly shaped by the stressful environment. At the same time, we were able to identify classes with differing patterns of violence exposure over time and examine how these different profiles were associated with early sexual initiation, allowing us to answer nuanced questions about the type, timing, and persistence of violence exposure that are suggest by differing theoretical perspectives. Below we discuss some of our findings that provide particular insights into aspects of these theories.

The Persistent Physical and Emotional Abuse Class.

We found that the class with the highest probability of early sexual initiation was the persistent physical and emotional abuse class. This finding aligns with previous research suggesting a positive association between child maltreatment histories and sexual risk behaviors, including early sexual initiation (Hillis et al., 2001; Wilson & Widom, 2008; Abajobir et al., 2018). This can be viewed as providing support for LHT’s emphasis on the harshness of stressors playing an important role in health outcomes, as this class was marked by the most instances of victimization against the child. From an evolutionary perspective, LHT posits that children are sensitive to important environmental cues from their rearing conditions, which later may profoundly influence their reproduction strategies. Experiencing persistent physical and emotional abuse sends the message that your living environment is characterized by high mortality and morbidity (Ellis et al., 2009), thus those people who delay reproduction would be selected against (Belsky, 1991). There are a number of potential neurobiological mechanisms that may underlie the associations between violence exposure and a fast reproductive style described by life history theory. For example, psychological dysregulation, including the deficits in behavioral self-regulation and emotion self-regulation, could be an important mechanism to link childhood maltreatment histories and early sexual initiation (Noll et al., 2011). Evolutionarily, developing the capacity of self-regulation might not be an adaptive response to the environment featured by child abuse because those children need to develop instant fight or flight response (Nakazawa, 2015).Research shows that childhood maltreatment victims experienced disruptions in the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis that were responsible for behavioral and affect regulation (Trickett et al., 2010; De Bellis & Kuchibhatla, 2006). Adolescents experiencing childhood maltreatment may have difficulties in behavioral self-regulation (Sprague & Walker, 2000), such as the inability to control impulsivity and delay gratification, which may contribute to early sexual initiation. At the same time, childhood maltreatment survivors may also suffer from deficits in emotion self-regulation such as modulating internal negative emotions. For example, Black et al.’s study (2009) suggested that youth exposed to childhood maltreatment showed more emotional distress than their counterparts without maltreatment histories, which in turn was associated with maltreated youth’s higher probability of engaging sexual intercourse by 14.

However, we found little evidence to support LHT’s emphasis on the unpredictability of stressors. In addition to the Persistent Physical and Emotional Abuse class, which was marked by persistent, harsh violence victimization, we identified patterns that included different ages of violence exposures. For example, we found profiles showing early and late child abuse victimization, as well as groups with a mother experiencing sporadic physical and emotional IPV. These classes can be viewed as experiencing “unpredictable” stressors, as opposed to classes with more persistent exposure across time. The highest prevalence of early sexual initiation among the persistent physical and emotional abuse class suggest the importance of harshness, as described in LHT, in predicting sexual behavior, but also that persistent, rather than unpredictable exposures are associated with greater risk of early initiation.

Mother Persistent Emotional IPV.

Surprisingly, we found the group of adolescents having a mother who experienced persistent emotional IPV showed the lowest prevalence of early sexual initiation compared to other groups. A potential mechanism for this association comes from attachment theory. Levendosky et al (2012) pointed out that the internal working model (e.g., the relational self and others) of mother IPV survivors were profoundly changed, causing disruptions in mother-child bonding and child attachment insecurity. Compared to physical IPV, mother experiencing emotional IPV might have a more pronounced effect on transferring attachment insecurity to their children. For example, based on a Japanese sample, Park (2021) found that mothers’ emotional IPV was positively associated with mothers’ lack of affect and anger/rejection bonding with their child. Given that children whose mothers are emotional IPV survivors are more likely to form insecure attachment, we speculate that they may avoid building intimate relationships or having intimate contact with romantic partners, and thus have a lower prevalence of early sexual initiation. At the same time, there might be other alternative factors to explain the lower prevalence of early sexual initiation for children whose mothers experiencing persistent IPV. For example, these children are more likely to form a negative impression of building intimacy with others; thus, they will try to avoid sexual relationships to protect themselves from being hurt. However, our finding should be interpreted cautiously because we did not find significant different outcomes between low violence exposure group and mother persistent emotional IPV group; the association between mothers’ emotional IPV and child later sexual behavior needs further exploration.

Neighborhood violence.

Though prior studies identified neighborhood violence as an important predictor for adolescent sexual risk behaviors (Wilson et al., 2012), we did not find a significant difference between the low violence exposure group and neighborhood violence only group. This finding partially aligned with Orihuela et al.’s work (2020) showing an interacting effect between neighborhood disorder and family functioning on adolescent sexual initiation. We speculate that family-level violence exposure may play a more important role in sexual imitation than neighborhood violence. At the same time, evidence shows that poverty and neighborhood violence tend to co-occur and interactively influence child developmental outcomes (Graif & Matthews, 2017). Given that our research scope focused on examining the impacts of violence, we only included poverty as a covariate in our analysis. However, future studies should consider the effects of both neighborhood- and family- level violence exposure, as well as other non-violent types of adverse childhood experiences, on adolescent sexual behavior.

Gender differences.

We found a number of notable gender differences in the associations between violence exposure latent class and early sexual intercourse. First, we found that for both boys and girls, experiencing persistent physical and emotional abuse was the biggest risk factor, though compared to boys, girls’ risk of early sexual initiation was more strongly affected by this type of violence. This is consistent with prior research suggesting that girls may be more influence by childhood adversity than boys (Haatainen et al., 2003). Additionally, girls were also more likely to be affected by early mother physical and emotional IPV, than boys with the same experience. In the framework of LHT, this finding could be interpreted as girls’ reproductive strategies are more sensitive to the cues of their childhood environmental harshness, and in particular violence directed against their mother, who they may identify more strongly with as the same-gender parent. Second, we also found that timing of abuse matters differently for boys and girls; girls’ risk of early sexual initiation was more likely to be affected by late abuse, while boys’ risk was more susceptible to early abuse. The findings on boys support the LHT’s argument of early life as a sensitive period and were partially aligned with the findings from Simpson’s study (2012) showing that early, but not late life experiences are associated with a faster life history. Though our findings on gender differences were coherent with other studies suggesting that males and females may react differently to adverse childhood experiences (Almuneef et al., 2017), the current LHT framework does not propose a mechanism to explain this difference. It is possible that by age 9, some girls are already starting to experience pubertal changes, and may be experiencing physical or verbal violence that is related to their physical appearance or sexualized, which may be associated with unique developmental outcomes. Future research is needed to better understand the different impacts of timing of victimization on sexual behaviors of boys and girls.

Implications.

Our findings provide important implications for the current practice on improving adolescent reproductive health. First, it is important to adopt a trauma-informed lens to incorporate the treatment of past violence victimization into sex education and intervention. Understanding how adolescents’ past violence victimization (particularly persistent child abuse) would influence the way they view themselves, others, and the world, and how these personal perceptions may influence their reproductive decisions can effectively help program and policy designers create tailored interventions. Second, the impacts of timing of violence victimization differ by gender, so it is important to design gender-sensitive programs to address unique risks of violence victimization for boys and girls. In particular, it may make sense to target boys who are exposed to violence in early childhood and girls who are exposed in middle childhood, along with those who experience persistent abuse.

There are a number of limitations to this study that suggest directions for future research. First, although child sexual abuse is a form of violence that has been found to predict early sexual behavior (Jones et al., 2013), there were no measures of this construct available in the data. It is possible that sexual abuse could occur in tandem with the other violence exposures in the study and subsequently drive some of the findings. However, compared to other types of child maltreatment, childhood sexual abuse was the least likely to co-occur with another form of victimization (Tourigny et al., 2008). However, future studies should also include measures of childhood sexual abuse. Second, the data is based on caregiver and child self-reports, and individuals may not accurately report their violence exposure or perpetration. The data included measures from only four ages across childhood, and thus are a snapshot of different age periods and may not be a comprehensive measure of all violence exposures. Relatedly, although exposures at only some of these ages can be seen as a form of “unpredictability,” our measures of this construct are limited as they don’t assess unpredictability within a wave. Due to our focus on the timing and accumulation of violence exposures we did not include all types of violence, including ones like peer bullying, violence by police and adolescent IPV exposure, which were only assessed at later waves. In addition, it is likely that violence exposure co-occurs with other challenges that children and their families face, and future research should further study this topic to attempt to determine causal pathways. Finally, although our use of FFCW gives an insight into a population which may be at higher risk of some forms of violence exposure, it is not a representative sample of the population and this may be more limited in its generalizability.

Despite these limitations, this study provides insight into how differing longitudinal patterns of violence exposure are associated with sexual behavior. In particular, our findings suggest that experiencing harsh and persistent physical and emotional abuse is associated with a higher prevalence of early sexual initiation. However, contrary to predictions from LHT, we did not find an effect of early exposure to violence, as these classes had lower rates of early initiation than those in classes marked by persistent or middle childhood exposures. These findings provide information about the processes theorized by LHT and cumulative disadvantage theory and suggest particular groups of young people who may be an important target of intervention efforts.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding. This work was funded by a David B. Falk College of Sport and Human Dynamics Tenure-track Assistant Professor Research Seed Grant and by NICHD grant R03 HD096101.

Footnotes

Ethical approval. The data used in this study received institution review board approval, and all procedures involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflicts of Interest. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Availability of data and materials. Data from this project is available at: https://fragilefamilies.princeton.edu/.

Code availability. This study uses Latent Gold software. Code for the distal outcomes analysis is available as an appendix.

REFERENCES

- Abajobir AA, Kisely S, Williams G, Strathearn L, & Najman JM (2018). Risky sexual behaviors and pregnancy outcomes in young adulthood following substantiated childhood maltreatment: findings from a prospective birth cohort study. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(1), 106–119. 10.1080/00224499.2017.1368975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander AA, McCallum KE, & Thompson KR (2021). Poly-victimization among adolescents adjudicated for illegal sexual behavior: A latent class analysis. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 30(3), 347–367. 10.1080/10926771.2020.177469 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almuneef M, ElChoueiry N, Saleheen HN, & Al-Eissa M (2017). Gender-based disparities in the impact of adverse childhood experiences on adult health: findings from a national study in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. International Journal for Equity in Health, 16(1), 1–9. 10.1186/s12939-017-0588-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baglivio MT, & Wolff KT (2021). Adverse childhood experiences distinguish violent juvenile sexual offenders’ victim typologies. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(21), 1–14. 10.3390/ijerph182111345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barra S, Bessler C, Landolt MA, & Aebi M (2018). Patterns of adverse childhood experiences in juveniles who sexually offended. Sexual Abuse, 30(7), 803–827. 10.1177/1079063217697135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Steinberg L, & Draper P (1991). Childhood experience, interpersonal development, and reproductive strategy: An evolutionary theory of socialization. Child development, 62(4), 647–670. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01558.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Schlomer GL, & Ellis BJ (2012). Beyond cumulative risk: distinguishing harshness and unpredictability as determinants of parenting and early life history strategy. Developmental psychology, 48(3), 662–673. 10.1037/a0024454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MM, Oberlander SE, Lewis T, Knight ED, Zolotor AJ, Litrownik AJ, … & English DE (2009). Sexual intercourse among adolescents maltreated before age 12: A prospective investigation. Pediatrics, 124(3), 941–949. 10.1542/peds.2008-3836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolck A, Croon M, & Hagenaars J (2004). Estimating latent structure models with categorical variables: One-step versus three-step estimators. Political Analysis, 12(1), 3–27. 10.1093/pan/mph001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Attachment (Vol. 1). Basic books. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WT, & Ellis BJ (2005). Biological sensitivity to context: I. An evolutionary-developmental theory of the origins and functions of stress reactivity. Development and Psychopathology, 17(2), 271–301. 10.1017/S0954579405050145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal M, Vernon-Feagans L, Cox M, & Key Family Life Project Investigators. (2008). Cumulative Social Risk, Parenting, and Infant Development in Rural Low-Income Communities. Parenting: Science and Practice, 8(1), 41–69. 10.1080/15295190701830672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin HB, Sipe TA, Elder R, Mercer SL, Chattopadhyay SK, Jacob V,. . . Santelli J (2012). The effectiveness of group-based comprehensive risk reduction and abstinence education interventions to prevent or reduce the risk of adolescent pregnancy, human immunodeficiency virus, and sexually transmitted infections: Two systematic reviews for the guide to community preventive services. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 42, 272–294. 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke K, Patalay P, Allen E, Knight L, Naker D, & Devries K (2016). Patterns and predictors of violence against children in Uganda: a latent class analysis. BMJ open, 6(5), e010443. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Richter DL, Valois RF, McKeown RE, Garrison CZ, & Vincent ML (1994). Correlates and consequences of early initiation of sexual intercourse. Journal of School Health, 64, 372–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, & Feeney BC (2004). An attachment theory perspective on closeness and intimacy. In Handbook of closeness and intimacy (pp. 173–198). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Bellis MD, & Kuchibhatla M (2006). Cerebellar volumes in pediatric maltreatment-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological psychiatry, 60(7), 697–703. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Figueredo AJ, Brumbach BH, & Schlomer GL (2009). Fundamental dimensions of environmental risk. Human Nature, 20(2), 204–268. 10.1007/s12110-009-9063-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman BJ, Masyn KE, & Conger RD (2009). New approaches to studying problem behaviors: a comparison of methods for modeling longitudinal, categorical adolescent drinking data. Developmental psychology, 45(3), 652. 10.1037/a0014851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, & Turner HA (2007). Polyvictimization and trauma in a national longitudinal cohort. Development and psychopathology, 19(1), 149–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden KP (2012). True love waits? A sibling-comparison study of age at first sexual intercourse and romantic relationships in young adulthood. Psychological Science, 23(11), 1324–1336. 10.1177/0956797612442550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, & Marchbanks PA (2001). Adverse childhood experiences and sexual risk behaviors in women: a retrospective cohort study. Family planning perspectives, 206–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord-Harden NK, Dickson D, & Pierre C (2016). Profiles of community violence exposure among African American youth: An examination of desensitization to violence using latent class analysis. Journal of interpersonal violence, 31(11), 2077–2101. 10.1177/0886260515572474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graif C, & Matthews SA (2017). The Long Arm of Poverty: Extended and Relational Geographies of Child Victimization and Neighborhood Violence Exposures. Justice Quarterly, 34(6), 1096–1125. 10.1080/07418825.2016.1276951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haatainen KM, Tanskanen A, Kylmä J, Honkalampi K, Koivumaa-Honkanen H, Hintikka J, Antikainen R, & Viinamäki H (2003). Gender differences in the association of adult hopelessness with adverse childhood experiences. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 38(1), 12–17. 10.1007/s00127-003-0598-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez ME, Wade R Jr, Schwartz-Soicher O, Lin Y, & Reichman NE (2017). Adverse childhood experiences and ADHD diagnosis at age 9 years in a national urban sample. Academic pediatrics, 17(4), 356–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DJ, Lewis T, Litrownik A, Thompson R, Proctor LJ, Isbell P, … & Runyan D (2013). Linking childhood sexual abuse and early adolescent risk behavior: The intervening role of internalizing and externalizing problems. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 41(1), 139–150. 10.1007/s10802-012-9656-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaestle CE, Halpern CT, Miller WC, & Ford CA (2005). Young age at first sexual intercourse and sexually transmitted infections in adolescents and young adults. American journal of epidemiology, 161(8), 774–780. 10.1093/aje/kwi095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D. (2007). Emerging answers 2007: Research findings on programs to reduce and prevent teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases. Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. [Google Scholar]

- Kugler KC, Vasilenko SA, Butera NM, & Coffman DL (2017). Long-term consequences of early sexual initiation on young adult health: A causal inference approach. Journal of Early Adolescence, 37(5), 662–676. 10.1177/0272431615620666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levendosky AA, Lannert B, Yalch M (2012). The effects of intimate partner violence on women and child survivors: An attachment perspective. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 40, 397–433. 10.1521/pdps.2012.40.3.397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy B, & Grodsky E (2011). Sex and school: Adolescent sexual intercourse and education. Social Problems, 58(2), 213–234. 10.1525/sp.2011.58.2.213 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meier AM (2007). Adolescent first sex and subsequent mental health. American Journal of Sociology, 112(6), 1811–1847. 10.1086/512708 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa DJ (2015). Childhood disrupted: How your biography becomes your biology, and how you can heal. Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Negriff S, Angeles L, Schneiderman JU, Angeles L, Trickett PK, & Angeles L (2015). Child maltreatment and sexual risk behavior: Maltreatment types and gender differences Sonya. Journal of Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, 36(9), 708–716. 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll JG, Haralson KJ, Butler EM, & Shenk CE (2011). Childhood maltreatment, psychological dysregulation, and risky sexual behaviors in female adolescents. Journal of pediatric psychology, 36(7), 743–752. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orihuela CA, Mrug S, Davies S, Elliott MN, Tortolero Emery S, Peskin MF, … & Schuster MA (2020). Neighborhood disorder, family functioning, and risky sexual behaviors in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(5), 991–1004. 10.1007/s10964-020-01211-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Greene MC, Melby MK, Fujiwara T, & Surkan PJ (2021). Postpartum depressive symptoms as a mediator between intimate partner violence during pregnancy and maternal-infant bonding in Japan. Journal of interpersonal violence, 36(19–20), NP10545–NP10571. 10.1177/0886260519875561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulk A, & Zayac R (2013). Attachment style as a predictor of risky sexual behavior in adolescents. Journal of Social Sciences, 9(2), 42–47. 10.3844/jssp.2013.42.47 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pickreign Stronach E, Toth SL, Rogosch F, Oshri A, Manly JT, & Cicchetti D (2011). Child maltreatment, attachment security, and internal representations of mother and mother-child relationships. Child maltreatment, 16(2), 137–145. 10.1177/1077559511398294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. (2017). R Core Team. [Google Scholar]

- Reichman NE, Teitler JO, Garfinkel I, & McLanahan SS (2001). Fragile families: Sample and design. Children and Youth Services Review, 23(4-5), 303–326. 10.1016/S0190-7409(01)00141-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. (1983). Statistical and personal interactions: Facets and perspectives. Human development: An interactional perspective, 295–319. [Google Scholar]

- Siller L, Edwards KM, & Banyard V (2022). Violence typologies among youth: A latent class analysis of middle and high school youth. Journal of interpersonal violence, 37(3-4), 1023–1048. 10.1177/0886260520922362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Griskevicius V, Kuo SI, Sung S, & Collins WA (2012). Evolution, stress, and sensitive periods: the influence of unpredictability in early versus late childhood on sex and risky behavior. Developmental psychology, 48(3), 674–686. 10.1037/a0027293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague J, & Walker H (2000). Early identification and intervention for youth with antisocial and violent behavior. Exceptional Children, 66(3), 367–379. 10.1177/001440290006600307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spriggs AL, & Halpern CT (2008). Sexual debut timing and depressive symptoms in emerging adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(9), 1085–1096. 10.1007/s10964-008-9303-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, & Runyan D (1998). Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child abuse & neglect, 22(4), 249–270. 10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00174-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourigny M, Hébert M, Joly J, Cyr M, & Baril K (2008). Prevalence and co-occurrence of violence against children in the Quebec population. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 32(4), 331–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuyuki K, Al-Alusi NA, Campbell JC, Murry D, Cimino AN, Servin AE, & Stockman JK (2019). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are associated with forced and very early sexual initiation among Black women accessing publicly funded STD clinics in Baltimore, MD. PLoS One, 14(5), e0216279. 10.1371/journal.pone.0216279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett PK, Noll JG, Susman EJ, Shenk CE, & Putnam FW (2010). Attenuation of cortisol across development for victims of sexual abuse. Development and psychopathology, 22(1), 165–175. 10.1017/S0954579409990332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt JK (2010). Latent class modeling with covariates: Two improved three-step approaches. Political Analysis, 18(4), 450–469. 10.1093/pan/mpq025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt JK, & Magidson J (2016). Upgrade manual for Latent GOLD 5.1. Belmont, MA: Statistical Innovations. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilenko SA (2017). Age-varying associations between nonmarital sexual behavior and depressive symptoms across adolescence and young adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 53(2), 366–378. 10.1037/dev0000229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilenko SA, Kugler KC, & Rice CE (2016). Timing of First Sexual Intercourse and Young Adult Health Outcomes. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(3), 291–297. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh JL, Senn TE, & Carey MP (2012). Exposure to Different Types of Violence and Subsequent Sexual Risk Behavior Among Female Sexually Transmitted Disease Clinic Patients : A Latent Class Analysis. Psychology of Violence, 2(4), 339–354. 10.1037/a0027716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Maguire-Jack K, Barnhart S, Yoon S, & Li Q (2020). Racial differences in the relationship between neighborhood disorder, adverse childhood experiences, and child behavioral health. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 48(3), 315–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HW, & Widom CS (2008). An examination of risky sexual behavior and HIV in victims of child abuse and neglect: a 30-year follow-up. Health Psychology, 27(2), 149–158. 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HW, Woods BA, Emerson E, & Donenberg GR (2012). Patterns of violence exposure and sexual risk in low-income, urban African American girls. Psychology of violence, 2(2), 194–207. 10.1037/a0027265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Schlomer GL, Ellis BJ, & Belsky J (2022). Environmental harshness and unpredictability: Do they affect the same parents and children?. Development and Psychopathology, 34(2), 667–673. 10.1017/S095457942100095X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.