Abstract

Myosin 5B (MYO5B) pathogenic variants are associated with microvillus inclusion disease (MVID), a congenital disorder of the enterocyte characterized by intractable diarrhea (5). A subset of MVID patients also have cholestatic liver disease. Conversely, some patients may have isolated cholestasis without gastrointestinal symptoms (2). Such patients have been described to have a progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC)-like phenotype with normal serum gamma-glutamyl transferase. We report a novel case in which MYO5B pathogenic variants were discovered by whole exome sequencing in a post-liver transplant patient who originally presented with PFIC-like cholestasis and chronic intermittent diarrhea without ultrastructural evidence of microvillus inclusion disease.

Case Report

A 19-month-old Caucasian male, born full-term following a normal pregnancy, was referred for evaluation of cholestatic hepatitis, pruritus and diarrhea. At two weeks of life, he began having multiple episodes of vomiting and diarrhea, which improved over time without intervention. He continued to show good weight gain but limited linear growth (height percentile: 4 %, weight percentile: 24 %, weight for length: 90%). Laboratory values at one year [DO YOU MEAN “one month”?? No, it is one year old. He was referred to see us around 1 years old, however he developed pruritis at 3 months old according to mom’s history] of age were notable for alanine aminotransferase (ALT) of 139 units/L, total/direct bilirubin of 2/1.6 mg/dL, and gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) of 20 units/L (Table 1). Viral hepatitis panel was negative. Sweat test and alpha-1 antitrypsin phenotype were normal. Thoracic-lumbar spine x-ray and ophthalmologic exam were normal. He had both normal urine and serum bile acid analysis. Magnetic resonance imaging of abdomen showed normal liver parenchyma without evidence of cirrhosis, hepatic lesions, or intra- or extrahepatic duct dilatation.

Table 1:

Laboratory tests

| Laboratory tests | At time of presentation | At time of liver transplantation | Two-months after liver transplantation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspartate Aminotransferase (units/L) | 122 | 60 | 29 |

| Alanine Aminotransferase (units/L) | 139 | 53 | 23 |

| Gamma-glutamyltransferase (units/L) | 20 | 11 | 26 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (units/L) | 667 | 738 | 179 |

| Total bilirubin/direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2/1.6 | 0.3/0.1 | 0.2/0.1 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.3 | 3.5 | 4.4 |

| Prothrombin time (PT) | 14.5 | 14.9 | 13.7 |

| International normalized ratio (INR) | 1.07 | 1.11 | 1.01 |

Targeted genetic testing was performed utilizing the EGL Cholestasis Panel, which reported two variants of uncertain significance, one in ABCB4 (c.1769G>A (p.R590Q)) and the second one in SMPD1 (c.1058C>T (p.P353L)). A second variant was not found on either gene. Liver biopsy was notable for bland canalicular cholestasis without portal or lobular inflammation. Bile ducts were present in all portal tracts without evidence of ductal plate malformation. The histologic features were determined to be consistent with PFIC (Figure 1). At three months of age, he developed pruritus that was refractory to hydroxyzine, rifampin and ursodiol. He underwent a nasobiliary drainage trial, but due to lack of symptom relief, he ultimately underwent a liver transplantation from a cadaveric donor at two years of age due to intractable pruritus.

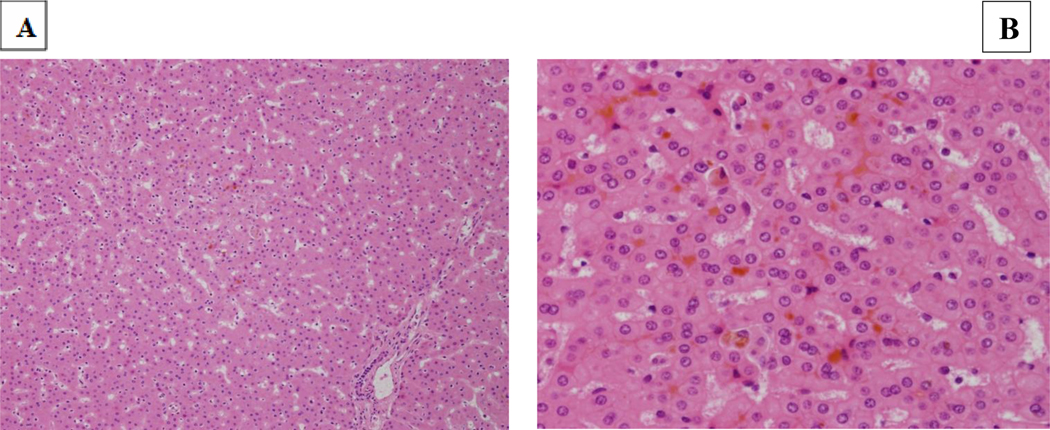

Figure 1: Liver biopsy (1A H&E 200x; 1B, H&E, 600x).

Bland canalicular cholestasis throughout with largely intact architecture, with normal portal tracts and lobules. Bile ducts are present in all portal tracts. The histologic features are consistent with PFIC.

Post-liver transplantation, he continued to have intermittent episodes of severe vomiting and diarrhea resulting in dehydration and electrolyte imbalances requiring hospitalization. Each episode resolved with a short period of total parenteral nutrition and bowel rest. Infectious studies have all been negative. At three years of age, he underwent an esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy, which were both unremarkable. However, his colon biopsy showed a focal area of active colitis with an eosinophilic crypt abscess with negative CMV immunostaining. No histopathologic abnormality was noted in his duodenum, including immunohistochemical staining for brush border component CD10 (a neutral membrane-associated peptidase) and normal ultrastructural findings (Figure 2). Due to the intermittent nature of his symptoms, we suspected intestinal dysmotility associated with intercurrent viral illnesses. In addition, he was started on antibiotic therapy alternating between metronidazole and ciprofloxacin for suspected small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Due to persistent intestinal symptoms, trio whole exome sequencing was performed, utilizing a methodology described elsewhere (1), revealing compound heterozygosity for a paternally-inherited pathogenic variant, denoted c.412dupC, p.(H138Pfs*17) (NM_001080467.2) that is a frameshift variant predicted to result in loss-of-function either through protein truncation or nonsense mediated decay, and a likely pathogenic variant in MYO5B that was a maternally-inherited likely pathogenic variant, denoted c.274C>T, p.(R92C). This missense variant has been previously reported in trans with another MYO5B variant in a patient with cholestasis (2). Furthermore, multiple in silico tools predict that this variant is deleterious. None of these variants had been previously reported in the ExAC database (https://exac.broadinstitute.org/) or in the Genome Aggregation Database (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/; last accessed on 02/14/2020) (3). Therefore, these findings are consistent with an autosomal recessive MYOB5-related disorder.

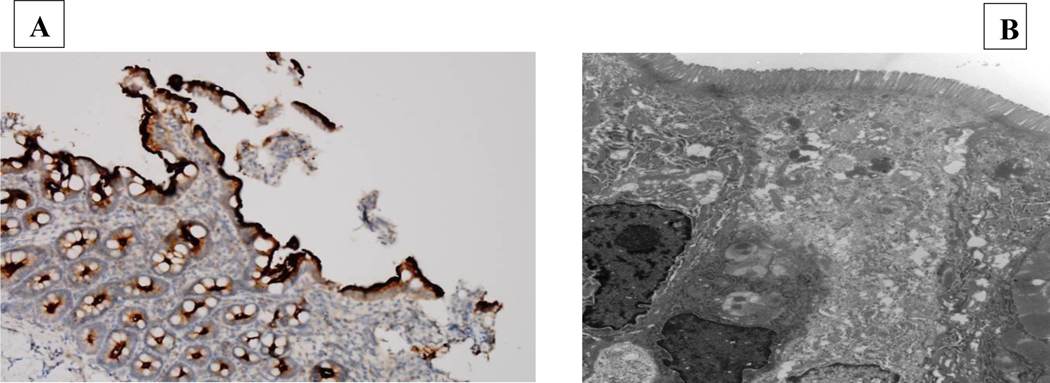

Figure 2:

Duodenal biopsy specimens. (A) Present of immunohistochemistry for brush border components CD10 (a neutral membrane-associated peptidase). (B) Transmission electron microscopy depicting normal microvilli.

Discussion

Pathogenic variants in MYO5B, which encodes the actin-based motor protein myosin Vb, have been found to cause MVID (4), a congenital intestinal disorder characterized by neonatal intractable diarrhea. Diagnostic findings of MVID from histology include villus atrophy, brush border reduction (immunohistochemistry CD10) and increased periodic acid-Schiff staining in light microscopy and shortening or absence of brush border microvilli (microvillus inclusion) in electron microscopy (4). Despite gastrointestinal symptoms and pathogenic and likely pathogenic MYO5B variants, this patient did not display the diagnostic light and electron microscopy hallmarks of MVID.

Typically, other organ systems are not affected by MVID, however cholestatic liver disease and renal Fanconi syndrome have been reported in some individuals (4). Moreover, biallelic variants in MYO5B have been reported in individuals with intrahepatic cholestasis with and without symptoms of MVID (6, 7). Girard et al suggested that the MYO5B pathogenic variants may lead to defective trafficking of the bile acid transporter ABCB11/BSEP to the apical bile canalicular surface of hepatocytes in the liver, thereby blocking the enterohepatic circulation of bile acids (5). Qui et al and Dhekne et al suggested that mild pathogenic variants result in isolated cholestasis while severe variants cause MVID, however more research is needed to clarify genotype-phenotype correlations (6, 7).

This case highlights the importance of genetic testing in patients with PFIC-like cholestasis and chronic diarrhea. Patients with MVID are at risk of developing a PFIC-like cholestasis, possibly resulting in intestinal and/or liver transplantation (4). Gonzales et al reported five patients with MYO5B variants causing cholestasis with normal serum GGT in children without MVID (2). However, none of five patients underwent liver transplantation. If this patient had been diagnosed with MYO5B mutations by whole exome sequencing prior to liver transplantation, his management may have been different. While his indication for liver transplantation was intractable pruritus, it is likely our team would have discussed the utility of a combined liver/intestinal transplantation. However, given the intermittent nature of his intestinal symptoms, good growth, and absence of the need for long term home parenteral nutrition, it is unlikely he would have derived benefit from an intestinal transplant. Thus, whole exome sequencing likely would not have altered the initial decision for liver transplantation.

It is unclear why certain MYO5B variants lead to MVID alone, MVID with cholestatic liver disease, or cholestasis alone without evidence of gastrointestinal disease. Thus, ours is the first report of a child with MYO5B mutation, PFIC-like cholestasis requiring liver transplantation, and chronic, intermittent diarrhea without ultrastructural evidence of microvillus inclusion disease.

What is Known

Myosin 5B (MYO5B) pathogenic variants are associated with microvillus inclusion disease (MVID), a congenital disorder of the enterocyte characterized by intractable diarrhea.

Biallelic variants in MYO5B have been reported in individuals with intrahepatic cholestasis with and without symptoms of MVID.

What is New

Patients with PFIC-like cholestasis and chronic diarrhea may require whole exome sequencing in order to establish an accurate diagnosis.

A patient with MYO5B mutation associated PFIC-like cholestasis can present with intermittent diarrhea and vomiting without ultrastructural evidence of microvillus inclusion disease (MVID).

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank the patient’s family for consenting and allowing them to write and publish this case report.

Abbreviations:

- MYO5B

Myosin 5B

- MVID

microvillus inclusion disease

- PFIC

progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis

- AST

Aspartate Aminotransferase

- ALT

Alanine Aminotransferase

- ALP

Alkaline phosphatase

- GGT

Gamma-glutamyltransferase

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: No financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References:

- 1.Tanaka AJ, Cho MT, Millan F et al. Mutations in SPATA5 Are Associated With Microcephaly, Intellectual Disability, Seizures, and Hearing Loss. Am J Hum Genet. 2015:97(3):457–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonzales E, Taylor SA, Davit-Spraul A, et al. MYO5B mutations cause cholestasis with normal serum gamma-glutamyl transferase activity in children without microvillous inclusion disease. Hepatology. 2017;65(1):164–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV et al. Analysis of Protein-Coding Genetic Variation in 60,706 Humans. Nature. 2016:536 (7616):285–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogel GF, Hess MW, Pfaller K et al. Towards understanding microvillus inclusion disease. Mol Cell Pediatr. 2016;3(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girard M, Lacaille F, Verkarre V, et al. MYO5B and bile salt export pump contribute to cholestatic liver disorder in microvillous inclusion disease. Hepatology. 2014;60(1):301–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qiu YL, Gong JY, Feng JY et al. Defects in myosin VB are associated with a spectrum of previously undiagnosed low γ-glutamyltransferase cholestasis. Hepatology. 2017;65(5):1655–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhekne HS, Pylypenko O, Overeem AW, et al. MYO5B, STX3, and STXBP2 mutations reveal a common disease mechanism that unifies a subset of congenital diarrheal disorders: A mutation update. Hum Mutat. 2018;39(3):333–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]