Abstract

The leachate collection system (LCS) and leak detection system (LDS) flow rate data from 240 cells (or a combination of cells) at 54 municipal solid-waste landfills (located in seven US states) with double-liner systems were analyzed to assess the performance of the primary liner system. The average LCS leachate collection rates for the study sites ranged from 380 L ha−1 day−1 (40.7 gal. acre−1 day−1) to 22,400 L ha−1 day−1 (2,390 gal. acre−1 day−1) on a sitewide basis, and the average LDS leachate collection rates ranged from 1.8 L ha−1 day−1 (0.2 gal. acre−1 day−1) to 577 L ha−1 day−1 (61.7 gal. acre−1 day−1) on a sitewide basis. Assuming all leachate generated is collected either by the LCS or LDS, the data suggest that the primary liner systems’ aggregated efficiency is over 98%. The collection efficiency at sites that used a composite liner (geomembrane underlain by a geosynthetic clay liner or a compacted clay liner) system was not statistically different from the sites that used only a geomembrane as the primary liner (geomembrane underlain by a permeable layer) (median of 99% for both types). Leakage rates were compared with those estimated from the equations used by the hydrologic evaluation of landfill performance (HELP) model. The comparison suggests that the equations used by the HELP model to estimate leakage through the liner overestimate the leakage rate through geomembrane primary liners but underestimate the leakage rate through composite primary liners based on the HELP-model-default defect size and suggested defect frequency. It is also possible that groundwater intrusion could contribute to a portion of the leachate collected from the LDS because leachate quality data collected from a few sites indicated the LCS leachate had a higher concentration of most constituents than the leachate collected from LDS.

Keywords: Municipal solid waste (MSW), Leachate generation rate, Liner leakage rate, Liner efficiency

Introduction

In the US, federal regulations for municipal solid-waste (MSW) landfills [Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) Subtitle D] require the installation of a low-permeability bottom liner overlain by a leachate collection system (LCS). The landfill’s LCS is comprised of a synthetic drainage net or highly permeable sand or gravel layer to promote leachate drainage to the sumps to maintain less than 30 cm of leachate head over the liner, as stipulated in the US Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) (NARA 2021). Leachate accumulation over the liner is controlled by grading the landfill’s base, so leachate intercepted by the liner flows to drainage trenches and subsequently to sumps and pump stations for removal from the landfill.

A typical MSW landfill liner system consists of either a single or double liner. A single liner consists of a geomembrane (GM) underlain by a compacted clay liner (CCL) or geosynthetic clay liner (GCL) (USEPA 1993). A double liner consists of two liner systems, referred to as the primary and secondary liner systems; the LCS of the primary liner is referred to as the LCS, whereas the LCS of the secondary liner is commonly referred to as the leak detection system (LDS); the secondary LCS is referred as LDS throughout this paper (NARA 2021). The vapor transmission through the geomembrane, pinholes (introduced during the manufacturing process), and construction defects in the geomembrane are the potential pathways for leachate to leak through the geomembrane liner (Schroeder et al. 1994).

At landfills constructed with single-liner systems, the only opportunity to assess the performance of the liner and LCS is typically through the site’s groundwater monitoring well network, which is generally required to be installed and routinely monitored for MSW landfills in the US (Podlasek et al. 2021). At facilities equipped with double liners, liner performance, and LCS collection efficiency can be more readily evaluated by comparing the leachate collection rates from the primary LCS and the LDS. Several authors have published LCS flow rates from operating and closed landfills. Morris et al. (2003), Benson et al. (2005), and Masoner et al. (2016) reported leachate collection rates from landfills included in the respective studies. However, the liner performance could not be evaluated based on the data reported by these researchers because many of the landfills were constructed with single-liner systems, or details pertaining to the liner configuration for sites with a double-liner system were not provided. Eithe and Koerner (1997) reported total LCS and LDS volumes collected from two landfill cells for an unknown duration and observed that 98% to 100% of leachate was collected through the LCS. Based on an analysis of leachate flow data from 187 double-lined cells, Bonaparte et al. (2002) reported that 90% to greater than 99% of the generated leachate volume was collected from the sites’ LCS, with the collection efficiency depending on the primary liner configuration (GM or a combination of GM/GCL or GM/GCL/CCL).

The leachate generation rate, leakage rates, and chemical composition are important inputs for designing, monitoring, and characterizing the long-term impacts of landfills. The leakage rate through a single-liner system, at best, can only be estimated using published empirical/analytical equations (e.g., Giroud and Bonaparte 1989a, b; Giroud et al. 1997; Touze-Foltz and Giroud 2003). The USEPA hydrologic evaluation of landfill performance (HELP) model, which is a commonly used tool for estimating leachate generation rate and head on the liner for landfill design and permitting in the US, uses these equations to estimate the leakage rate through the liner system. However, the measured LDS rates for landfills with a double-liner system provide a reliable estimate of the potential leakage rate through a geomembrane liner. Landfill owners and operators typically track the volume of leachate collected from the LCS and LDS (if present) throughout the active operating life and for an extended period after landfill closure. Several state environmental agencies require landfill owners/operators to routinely submit the collected LCS and LDS data and publish these on publicly accessible websites. As a result, a substantial amount of additional data have become available since the study by Bonaparte et al. (2002).

This research offers new insights into the geomembrane liner system and aims to address questions related to its efficacy, i.e., its ability to retain leachate within the landfill cell, and how well the leakage rate through the liner system can be predicted using the existing mathematical equations. Specifically, this paper examines measured data from landfill sites with double-liner systems. The leakage rates measured at these sites were compared with estimated leakage rates derived from commonly used equations used in this area of study, including those used by the HELP model. This comparison provides an opportunity to demonstrate how well these equations can predict the potential for leakage to occur through a geomembrane liner system. The findings could be of particular use to the solid-waste community in understanding leakage through landfill liners and for assessing the long-term risk of landfills and the accuracy of predicting the leakage rate through an engineered liner system using the currently available and used models/equations.

Material and Methods

Data Sources

LCS and LDS leachate volume collection records for double-lined MSW landfills were obtained from 54 sites located in seven US states: Arkansas (AR), California (CA), Florida (FL), New Hampshire (NH), New Jersey (NJ), New York (NY), and Pennsylvania (PA). The data were collected through the respective state regulatory program’s online portal or direct contact with the landfill site manager or the state environmental agencies. As new cells were added, the leachate collection area at several study sites progressively increased with time. The leachate collection volume was reported for individual cell areas at some sites, whereas for others, the reported volume corresponded to a combination of multiple cells or the entire site. Because LCS and LDS data were reported for areas that represented a combination of multiple cells for many sites, the general term “cell area” instead of “cell” is used for each unique combination of cells that LCS/LDS data were available. Leachate quality data were also collected for a few sites.

The aggregation frequency of the data reported to the regulatory agencies varied among the sites. Daily and monthly collection volumes/meter readings were reported in many cases. The monthly volumes, along with quarterly volumes, were reported for a few sites. The monthly volumes were primarily compiled for the sites with a few exceptions. Only quarterly data were available for two landfills in NJ over 1 year. Additionally, only quarterly data were available for four quarters for the PA landfill, whereas another landfill in FL only had quarterly data available over 8 years. Annual collection data could only be located for 2 years at one of the NY landfills.

When available on publicly accessible domains, information on the liner design configurations of the study landfills was also collected to assess the impact of liner configuration on the leakage rate and liner efficiency. Among the 54 study landfills, detailed liner design configurations could be obtained for 17 sites. With a few exceptions, all of the cell areas examined in this study at 10 of these landfills were equipped with a geomembrane as the primary liner over the LDS [Fig. 1(a)] (referred to herein as a geomembrane primary liner). The primary liner of most of the cell areas examined in this study at the seven other landfills consisted of a geomembrane underlain by a low-permeability GCL layer above the LDS. This liner configuration [Fig. 1(b)] is referred to herein as a composite liner. Table S1 presents pertinent liner and LCS details of these 17 sites.

Fig. 1.

Cross-section view of typical double-bottom-liner systems with parameters used for the HELP modeling for (a) geomembrane primary liner system; and (b) composite liner system.

LCS and LDS Collection Rate Estimation

The daily volumetric leachate collection rate ( L ha−1 day−1) for each site was estimated by dividing the reported LCS and LDS volumes collected over each reporting period by the number of days in that reporting period and the LCS or LDS area using Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively

| (1) |

| (2) |

where collection rate per unit area from LCS over the reporting period collection rate per unit area from LDS over the reporting period ; leachate volume collected from LCS over the reporting period ; leachate volume collected from LDS over the reporting period ; of days in the reporting period ; of LCS over the reporting period (ha); and of LDS over the reporting period (ha). The collected data were also examined for potential outliers. One of the LCS flow rates (2.21 billion L over a month from a lined area of 27.3 ha) reported for a site seemed unrealistic. This data point and the corresponding LDS flow rate were excluded from the analysis because it appeared to be a reporting or calibration error.

Time-weighted-average (referred to as weighted-average) LCS and LDS volumetric collection rates were calculated for each discrete cell area using these individual collection rates for all the available reporting periods to account for variations, if any, in the reporting period at a site using Eqs. (3) and (4), respectively

| (3) |

| (4) |

where and = time-weighted-average leachate collection rate per unit area ( L ha−1 day−1) from cell area for LCS and LDS, respectively; = number of reporting periods; and the other parameters were defined in preceding paragraphs. The site-specific average LCS and LDS flow rates were calculated by averaging the time-weighted-average flow rates of all the cell areas at the site.

The LCS efficiency of each site was calculated by dividing the total LCS volume by the sum of total LCS and LDS volumes for each reporting period for each cell area at each site [Eq. (5)]

| (5) |

where leachate collection efficiency of a cell area and all reporting periods for cell area ; leachate volume collected from LCS of the cell area during reporting period (L); and leachate volume collected from LDS of the cell area during reporting period (L). For the cell areas at 17 sites where detailed liner configurations (i.e., geomembrane or composite liner) were available, the impact of the liner configuration on LCS efficiency and leakage rate was assessed.

The data collected from the study sites were examined to iden-ify whether different contributing factors, such as precipitation or the disposal of wastes with high water content, such as sewage sludge, were strongly correlated to leachate collection rates at the study sites. Precipitation has previously been well-documented to significantly influence the landfill gas generation rate (Pelt 1993; USEPA 2008; Vu et al. 2017; Park et al. 2018; IPCC 2019; Jain et al. 2021), but information on the effect on the leachate generation rate is sparse.

Comparison of Measured and Theoretical Leakage Rates

An additional objective of this study was to assess the efficacy of the approaches/equations used by the HELP model for estimating the leakage rates through the liner, as documented by Schroeder et al. (1994). The site-estimated leakage rates were compared with those calculated using the empirical equations used by the HELP model to estimate the liner leakage rates for the two liner configurations. The HELP model background details relevant to this study are provided in the Supplemental Materials. The leakage rates through a geomembrane primary liner and a composite liner were estimated using the inputs identified in Figs. 1(a and b) at the HELP-default defect area and by varying the defect frequency. The calculated leakage rates were compared with the weighted-average leakage rates measured for the study landfills with the respective liner type (geomembrane primary liner or composite liner).

For composite liners, the leakage rates were calculated using the HELP model equations for four types of geomembrane contact quality (i.e., poor, good, excellent, or perfect) with the underlying GCL, assuming 0.3 m of head over liner and a defect area of 1 cm2 for defect frequencies ranging from one defect per 1,000 ha to 1 million defects per ha, which is equivalent to a collective defect size ranging from 10−3 to 106 cm2 ha−1.

The HELP model uses the orifice equation to estimate the leakage rate through a defect in a geomembrane primary liner, assuming a constant head over the liner. However, a major limitation of this equation is that it does not accurately represent the behavior expected for the leachate head over a defect in the geomembrane directly over a high-permeability layer. Because the leachate flow rate in the LCS is typically low, the leachate head directly over a defect in the geomembrane would be expected to exhibit a drawdown effect because the presence of a high-permeability LDS drainage layer below the geomembrane would not be able to impede the leachate flow from the LCS to the LDS below. Therefore, a lower-than-expected head over the liner defect would also suggest a lower leakage rate than estimated using the orifice equation used by the HELP model.

The leachate drawdown around the defect would depend on the leachate impingement rate into the LCS from overlying waste. Giroud et al. (1997) developed a series of equations to address this phenomenon. For geomembrane primary liners, the equation suggested by Giroud et al. (1997) was used along with the orifice equation used by the HELP model to determine which would give a more accurate representation of the leakage rates observed at the study sites. The leakage rates were calculated using 0.5 cm of head over liner and HELP-default defect area of 1 cm2 for defect frequencies ranging from one defect per 1,000 ha to 1,000 defects per hectare, which is equivalent to a collective defect area ranging from 10−3 to 103 cm2 ha−1. The geocomposite hydraulic conductivity was assumed to be 10 cm s−1 for the LDS rate estimation using the Giroud et al. (1997) equation. The leakage rate estimated using the HELP model and Giroud et al. (1997) equations were compared with the weighted-average LDS flow rate measured at the sites with a geomembrane primary liner.

The HELP model and Giroud et al. (1997) equations use the head on the liner as one of the input parameters to estimate the leakage rate through the liner. The head on the liner is typically not measured in the field, but NH state regulations require routine measurement of the head on the liner at a low point in the base of the cells where leachate is collected (NHCAR 2020). Head on liner data were available for 25 monitoring locations at six study sites in NH. A total of 33,204 head on the liner measurements at these sites were compiled over multiple years. The measurement/reporting frequency ranged from daily to weekly; only monthly averages were reported for two sites. The collected head on the liner measurements were examined in detail to determine if the assumed head on the liner value used for the LDS rate calculations using the HELP-model equation and Giroud et al. (1997) was reasonable.

Statistical Analysis

The normality of LCS and LDS flow rates and liner efficiency was checked using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The data were log-transformed if these were not normally distributed. The transformed data were compared using a -test. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test (also known as the Mann-Whitney test) was used for statistical comparisons if the log-transformed data were not normally distributed.

Results and Discussion

Data Analyzed

The leachate collection volume data from each site’s LCS and LDS were analyzed for 240 landfill cell areas (or a combination of cells) among the 54 study sites. Table 1 summarizes the number of sites/cell areas, duration of available data, and median and ranges of the site-specific average LCS and LDS flow rates for all sites within each state. The data were available from less than 1 to 21 calendar years among the 240 landfill cell areas. Over 42% of the cell areas had data available for 5 or more years, and approximately 25% of the cell areas only had data available for 1 year or less. For most of the sites, the LCS and LDS volumes were typically measured on a daily basis. Table S2 provides a more detailed breakdown of the data collected from each cell area of each site.

Table 1.

Background information on study site data and statewide distribution of average LCS and LDS leachate collection rates for all 54 study landfills

| State | Number of study sites |

Number of cell areas |

Range of years for data availability |

Time-weighted-average LCS rate ( L ha−1 day−1)a |

Time-weighted-average LDS rate ( L ha−1 day−1)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Median | Range | Median | ||||

| NY | 29 | 147 | 0.2–15.0 | 2,213 (237)–17,557 (1,877) | 5,926 (634) | 5.8 (0.6)–336 (35.9) | 39.2 (4.2) |

| FL | 11 | 42 | 0.3–16.5 | 1,104 (118)–15,469 (1,654) | 3,499 (374) | 1.8 (0.2)–212 (22.7) | 78.4 (8.4) |

| NH | 7 | 13 | 0.2–21.0 | 380 (41)–22,359 (2,390) | 4,891 (523) | 2.2 (0.2)–537 (57.4) | 138 (14.8) |

| NJ | 4 | 15 | 0.5–3.5 | 2,326 (249)–9,514 (1,017) | 5,103 (546) | 20.1 (2.1)–577 (61.7) | 218 (23.3) |

| AR | 1 | 12 | 3.6–13.1 | 3,925 (420) | 73.4 (7.8) | ||

| CA | 1 | 2 | 6.0 | 897 (96) | 8.6 (0.9) | ||

| PA | 1 | 9 | 1.0–9.5 | 1,636 (175) | 7.0 (0.7) | ||

Numbers in parentheses are flow rates in gallons per acre per day.

Leachate Collection Rates

High variability in the leachate generation rate was found among the sites examined in this study, as indicated in Table 1. The sitewide LCS collection rates ranged from 380 L ha−1 day−1 (41 gal. acre−1 day−1) to 22,359 L ha−1 day−1 (2,390 gal. acre−1 day−1). As expected, the rate of leachate collection from the LDS (i.e., leakage rate) was substantially lower than the LCS. The weighted-average leakage rates for the study sites varied from approximately 1.8 L ha−1 day−1 (0.2 gal. acre−1 day−1) to 577 L ha−1 day−1 (61.7 gal. acre−1 day−1), as indicated in Table 1.

A higher LCS collection rate would potentially result in a greater head on the liner, which would significantly impact the leakage rate through the primary liner. On the other hand, a higher LCS rate might indicate that there is more efficient leachate removal from a cell than cells with a lower LCS collection rate. Greater leachate removal efficiency results in a lower residence time of leachate above the liner and possibly a lower head on the liner. Fig. S1 presents distributions of the measured leakage rates as a function of their associated LCS collection rates, divided by quartiles. A Wilcoxon rank-sum test indicated that the median leakage rate from the cell areas with LCS rate of less than 2,766 L ha−1 day−1 (first or lower quartile) was significantly lower (p < 0.001) that the median LDS rate of cell areas with LCS rates ranging from 2,766 to 4,867 (second quartile or median) L ha−1 day−1. The liner efficiency was not significantly (p > 0.7) different between these two groups of cell areas.

The median LDS rate of the fourth group (with LCS rates ranging from the upper quartile to maximum) was not significantly (p = 0.198) different from the median LDS rate of the cell areas in the second group (with LCS rates ranging from lower quartile to median). The analysis suggests that up to a point, higher LCS flow rates result in greater LDS rates. The data suggest that beyond a point, the LCS rate does not impact the LDS rate, and the LDS rate is controlled by other factors such as defect frequency, defect size, and groundwater intrusion, as discussed subsequently.

Precipitation data for the sites are presented in Table S2. The median annual precipitation at the study sites was 1,139 mm. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test indicated that the median of the sitewide average LCS rates for sites receiving less than 1,139 mm precipitation annually was not significantly different (p = 0.1) from that for the site receiving for than 1,139 mm precipitation annually. However, the annual precipitation at all but one site was greater than 810 mm (32 in.). As a result, this observation primarily applies to landfills with greater than 810 mm (32 in.) per year of precipitation.

Similarly, when information was available on the types of waste disposed of at a site, it was found that the weighted-average LCS collection rates at the sites that accepted sewage sludge were not significantly different from the sites that did not accept sewage sludge; waste composition data were available only for NY sites. These findings, however, should not be used to conclude that precipitation or high-moisture-content waste disposal does not influence leachate generation because a majority of the sites included in this study are located in nonarid regions, and several studies in the current body of literature have suggested a positive correlation between leachate generation and precipitation (Abunama et al. 2021; Al-Yaqout 2003).

In addition to these two factors, the leachate generation and collection are likely influenced by the confluence of various design and operational factors. For example, the level of the precipitation that percolates through the landfill and the resulting leachate generation rate is expected to decrease with cell age because a larger fraction of the cell area is constituted of covered and vegetated slopes, which promote stormwater runoff. The leachate collection rate is expected to vary substantially among different cell areas, even at the same site. Older cells are expected to have a lower leachate generation rate because these are more likely to have covered and vegetated slopes to promote stormwater runoff and minimize rainfall intrusion into the landfill.

One study landfill had data available for 12 different cell areas. The leachate collection rate data for these cell areas showed appreciable variation. The average leachate collection rates for the three newest cells ranged from 3,000 to 9,000 L ha−1 day−1 (median of 7,400 L ha−1 day−1) and was appreciably higher than the average leachate collection rates (2,000 to 5,300 L ha−1 day−1 and median of 3,000 L ha−1 day−1) from the remaining nine older cells. The data from this site demonstrate that leachate collection rates may vary considerably among cell areas at the same landfill site. Several other factors, such as landfill topography, evapotranspiration, and the degree of waste compaction, may have a greater influence on the leachate generation rate (Ghiasinejad et al. 2021; Tatsi and Zouboulis 2002) but could not be assessed in this paper.

Primary Liner Efficiency

The average primary liner leachate collection efficiency () was estimated for all 240 of the cell areas except for 26 cell areas with reported primary liner areas that differed from the respective secondary liner areas. More than three-quarters of the cell areas had a collection efficiency greater than 98%, and 199 cell areas had a collection efficiency greater than 95%. The median and average collection efficiency for all the cell areas was 99% and 98%, respectively. The results were consistent with the efficiencies reported by Bonaparte et al. (2002). Bonaparte et al. (2002) reported the median and average collection efficiencies for active sites with geomembrane primary liners also to be 99% and 98%, respectively; median and average collection efficiencies for composite liners were even higher (both 100%).

To assess the possibility of temporal changes in primary liner efficiency, efficiency data for six double-lined landfill cell areas (from 6 landfill sites) with 15 or more years of leachate collection data were examined. At each of the six sites, the average efficiencies were calculated for each year. The efficiency during the first half was statistically compared with the efficiency during the second half of the duration for each site. The analysis did not indicate a significant decrease in liner efficiency over the duration (<21 years).

Impact of Liner Configuration

As indicated in Table S3, the weighted-average leakage rates among the cell areas of all 17 sites with available liner configuration details varied considerably, from 0.60 L ha−1 day−1 (0.06 gal. acre−1 day−1) to 1,350 L ha−1 day−1 (144 gal. acre−1 day−1). A geomembrane was used as the primary liner at 10 of these sites, and a composite liner was used as the primary liner for the seven other sites; only the LCS and LDS rates of the cells with known bottom-liner configurations were used for this analysis.

The median of the site-specific average leakage rate through the geomembrane primary liner was higher than the median of the site-specific average leakage rate through the composite liner, which was expected because the low permeability GCL layer in the composite liner case would impede the flow of leachate from the LCS to the LDS. However, based on a Wilcoxon rank-sum test, the median leakage rate through cell areas with a geomembrane primary liner was not significantly (p > 0.7) different from the median of the cell areas with a composite primary liner. Similarly, based on a Wilcoxon rank-sum test, the median efficiency of a geomembrane primary liner was not significantly (p > 0.15) different from the median of the cell areas with a composite primary liner. Although this suggests that liner configuration does not affect the leakage rate or the efficiency, it is possible that a substantial portion of the leachate collected from the LDS may originate from another source, such as groundwater. This possibility is discussed in a subsequent section.

The leakage rate through the composite liner among the cell areas of the seven study sites ranged from 6.1 × 10−10 to 1.6 × 10−7 cm/s. Over two-thirds of these cell areas had a leakage rate greater than the typical hydraulic conductivity of the GCL (3 × 10−9 cm/s). The leakage rate through the composite liner is expected to depend on the quality of the contact between the geomembrane and the underlying GCL, the permeability of the GCL, and the geomembrane defect frequency. Assuming that the geomembrane defect frequency is similar between the geomembrane primary and composite primary liners, a combination of the poor geomembrane and GCL contact and deterioration in GCL performance in the field (Benson et al. 2005) is likely the cause of the composite liners leakage rates that are comparable to the leakage rates through geomembrane primary liner. Future studies should consider assessing the contact quality between the geomembrane and underlying GCL/CCL achieved with current construction practices and its impact on the leakage rate through the primary liner.

Evaluation of HELP Model Leakage Rate Estimation

As discussed previously, leakage through the primary liner occurs through the following pathways: water vapor transmission through the geomembrane, pinholes (introduced during the manufacturing process), and construction defects in the geomembrane. The pinholes and defects are collectively referred to herein as flaws.

The HELP model used 1 mm as the default diameter for a pinhole and a 1 – cm2 area for a defect for calculating leakage rates through the flaws. The estimated leakage through a HELP-default size pinhole and defect is approximately six to seven orders of magnitude greater than that associated with vapor transmission through the geomembrane primary liner. The estimates suggest that vapor transmission is not the dominant leakage pathway for the primary liner system. The leakage through the primary liner is likely principally contributed by the geomembrane defects that result from the liner installation process. These are likely more prevalent than the pinholes associated with the manufacturing process, so the impact of defects was the focus of the analysis. In addition, except for the free-flow case where high-permeability layers surround the geomembrane, the HELP model used the same set of equations to estimate leakage through pinholes and defects.

A defect area of 1 cm2 was chosen because this is the fixed default area used by the HELP model. The initial defect frequency was set at 2.5 defects per hectare (one defect per acre); Schroeder et al. (1994) recommend a defect frequency of 2.5 defects per hectare (one defect per acre) to 25 defects per hectare (10 defects per acre). As shown in Fig. 2(a), the modeled leakage rate through a defect at 0.5 cm of head over the liner was about two orders of magnitude greater than the median LDS flow rate for the cell areas with a geomembrane primary liner. For composite liner conditions [Fig. 2(b)], the leakage rate at all cell areas was greater than the HELP model estimated leakage rate for all contact conditions, even at 30 cm head over the liner. Although not shown in the figure, the estimated leakage rate from vapor transmission was over an order of magnitude lower than the leakage rate through defects in excellent contact conditions.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of measured leakage rate data for cell areas from (a) 10 landfills with a geomembrane; and (b) seven landfills with a composite liner. HELP model equation estimated liner leakage rates (LDS collection rates) for different leakage pathways are shown as horizontal dashed lines for geomembrane primary liner at 0.5 cm of head on the liner and composite liner at different contact conditions (perfect, excellent, good, and poor) at 30 cm of head on the liner.

The head on the liner measurements collected at the six NH sites were examined to determine if the head values used for the HELP model equations were reasonable. All the measurements at two sites indicated zero head on the liner, which is likely because of the use of geocomposite or geonet as the drainage layer for the leachate collection systems at these sites. Over 98% of the monthly average head readings reported for a third site were reported as zero; the LCS design details were not available to review for this site. Over 80% of measurements were reported as zero for a fourth site; geocomposite was used as the LCS drainage layer for two of the cells at this site with available design details. At these four sites, less than 2% of the head measurements were greater than 0.3 m. Approximately 51% to 52% of the daily head measurements were zero for the remaining two sites; sand was used as the drainage layer for the leachate collection system for one site, but the design details were unavailable for the other site. Approximately 6% to 11% of the measurements exceeded 0.3 m at these two sites.

As expected, the reported head on the liner was lower for the sites that used a geocomposite/geonet as the drainage layer than for sites using sand as the drainage layer for the LCS. Based on the reported data, the leachate appears to drain through the geocomposite readily, and results in a head that is smaller than the geocomposite thickness, which is typically less than 1 cm (0.01 m). Nine out of the 10 sites with a geomembrane primary liner used a geocomposite as the drainage layer for the LCS, so the average head was expected to be smaller than the geocomposite thickness (<1 cm). Therefore, a head on the liner of 0.5 cm is reasonable for the sites that used geocomposite for the LCS.

Apart from the defect size and the head on the liner, the leakage rate through the primary liner is also dependent on the defect frequency. Fig. 3 presents the estimated leakage rate as a function of the number of 1 cm2 defects per unit lined area for a geomembrane primary liner for 0.5 cm (0.005 m) of head on the liner. The estimation approach used by the HELP model suggests that a single defect of 1 cm2 area per 40 ha is sufficient enough to result in the leakage rate observed at approximately 50% of the study sites with a geomembrane primary liner. As a point of comparison, Schroeder et al. (1994) suggested using 2.5 defects per hectare (one defect per acre) to 25 defects per hectare (10 defects per acre) for the leakage rate estimation. At this range of defect frequency, the HELP model leakage rate estimate from defects would be over an order of magnitude greater than the maximum weighted-average LDS rate measured for cell area with the geomembrane primary liner. The empirical equation used by the HELP model for estimating the leakage through a defect in a geomembrane primary liner overestimates the leakage rate even at a conservatively lower head of 0.005 m (0.2 in.).

Fig. 3.

LDS flow rate as a function of defect frequency through defects in a geomembrane liner as estimated by equations used in the HELP model and Giroud et al. (1997) at 0.5 cm of head on the liner and the maximum, median, and minimum of the time-weighted-average LDS flow rate observed from 48 cell areas of the 10 study landfills with a geomembrane primary liner. Hydraulic conductivity of 0.1 m/s was used for the geocomposite for estimations. The actual defect area for the site-measured data is unknown.

The equations presented by Giroud et al. (1997) were also applied to the present study to determine if these would give a better estimate of reality when compared with the observed leakage rates measured at the study landfills with a geomembrane primary liner, as illustrated in Fig. 3. With the Giroud equations, the estimated leakage rates for the maximum and median LCS flow rates were over an order of magnitude lower than the HELP model estimates and fell between the median and maximum measured leakage rate at a defect frequency of 2.5 per hectare.

Compared with the HELP model methodology (orifice equation), the Giroud equations yielded leakage rates more representative of the LDS flow rates measured at sites with a geomembrane primary liner and a geocomposite as the drainage layer for the LCS. Other empirical equations and methodologies have been developed to predict leakage through geomembrane primary liners, which may be able to give an even more accurate prediction of the site-measured data from this study upon further investigation (Abuel-Naga and Bouazza 2014; Kumari and Rakesh 2019; Rowe and Fan 2022).

Fig. 4 presents the estimated leakage rate as a function of the number of defects per unit area for a composite liner at 30 cm (0.3 m) head on the liner. In contrast to the geomembrane primary liner case, the HELP model equations were found to underestimate the leakage rate through a composite liner for all four contact conditions, even with a conservatively high head on the liner, as depicted in Fig. 4. At the HELP model default defect area (1 cm2) and HELP-suggested defect frequency of 2.5 to 25 defects per hectare, the predicted leakage rates at perfect, excellent, and good contact conditions were below the minimum leakage rate observed at sites with a composite liner. Either the HELP model equations significantly underestimate the leakage rate based on the LDS flow rates of the seven study landfills, the head over liner was significantly greater than 0.3 m, or there might be some moisture intrusion into the LDS other than leakage from the primary liner, discussed in the next section.

Fig. 4.

LDS flow rate as a function of defect frequency through defects in a composite liner as estimated by equations used in the HELP model at 30 cm of head on the liner and the maximum, median, and minimum of the time-weighted-average LDS flow rate of 27 cell areas from the seven study landfills. The actual defect area for the site-measured data is unknown.

Groundwater Intrusion Potential

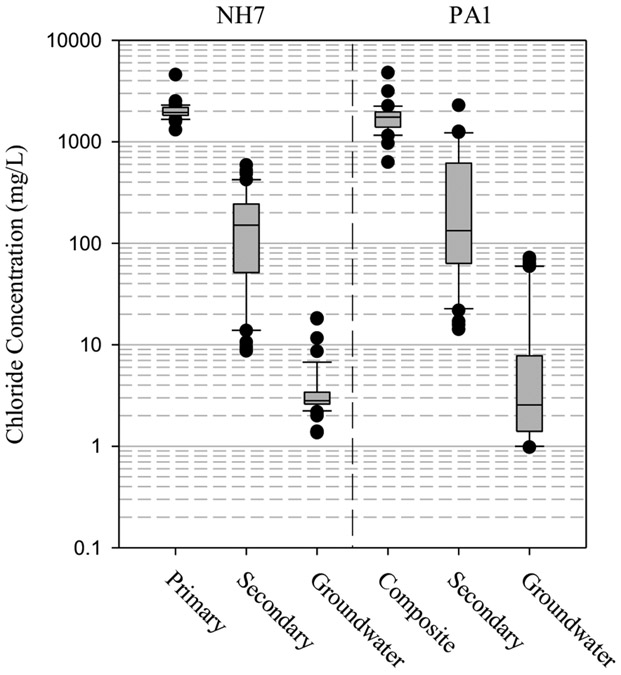

Groundwater intrusion could potentially contribute to a higher-than-expected LDS collection rate, as suggested by Bonaparte et al. (2002). Leachate and groundwater quality data were examined to assess this possibility for two of the sites in this study that had data available. It was found that leachate collected from the LDS at these two sites had a higher concentration of chloride than the underlying groundwater but a lower concentration than leachate collected from the LCS, as shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Chloride concentration distribution of LCS and LDS leachate, and background groundwater quality at sites NH7 and PA1.

Assuming that the attenuation in chloride concentration is solely attributed to dilution by groundwater (and not due to precipitation as chloride salts), the magnitude of the difference in chloride concentration suggests that leachate leakage through the primary liner represents about 1/10th of the liquids collected from the LDS for these two sites. If this is the case at other sites, it would indicate that the primary liner efficiency presented in this study is likely conservatively underestimated and actual liner efficiencies are higher, assuming that the leachate leakage, if any, through the secondary liner is insignificant.

Additionally, it would indicate that the leakage rate through the primary liner could not be deemed equivalent to the LDS collection rate because most of the LDS flow would have originated from the groundwater or another source. Even if the actual leakage through the primary liner is about 1/10th of the values reported for the study sites, the HELP model leakage rate estimation approach would still significantly overestimate the leakage through defects for sites with a geomembrane primary liner at a defect frequency ranging from 2.5 to 25 defects per hectare. However, the approach would provide a more accurate estimate of the leakage rate through defects for sites with a composite liner but still underestimate for most contact conditions.

Only the LCS and LDS leachate quality data were available for two more sites; groundwater quality data were not available for review. The constituents for which data were available included chloride, sulfate, biological oxygen demand (BOD), chemical oxygen demand (COD), pH, specific conductance, total dissolved solids (TDS), and several inorganic and organic constituents. The median concentrations for all constituents were higher in the LCS leachate except for sulfate, manganese, and 2-butanone, which were found in higher concentrations in the LDS leachate. If all leachate in the LDS originated from the LCS, then the leachate quality from both collection systems would be expected to be identical. However, the fact that the leachate from the LCS had higher concentrations of most constituents than the leachate from the LDS suggests that the LDS leachate could have been diluted with groundwater. In addition, the higher concentrations of sulfate in the LDS could indicate groundwater intrusion because sulfate is often prevalent in groundwater sources, primarily originating from the dissolution and oxidation of sulfur-containing minerals, such as gypsum and pyrite (Hassan et al. 2020). However, further investigation is needed to determine if groundwater intrusion is the true cause of these differences between the LCS and LDS leachate quality because groundwater quality data from only two sites were available and evaluated in this study.

Conclusions

The results from this investigation demonstrated that the leakage rate through a bottom-liner system varies substantially among the study sites. Although sites with a composite liner were hypothesized to exhibit a lower leakage rate than sites with a geomembrane primary liner, an analysis of the available data showed no significant difference between the two different liner types. Additionally, the leakage rate predictions from commonly used equations (HELP model) in this area of research were found to fall mostly outside of the observed data range, suggesting that additional data evaluation and/or a different set of equations may be necessary.

Supplementary Material

Practical Applications:

The findings from this investigation have practical relevance to landfill operators and researchers involved in this field of study. The results suggest that incorporating a geosynthetic clay liner (GCL) or compacted clay liner (CCL) between the LCS and LDS may not significantly impact the leakage rate through the primary liner, possibly because of the poor contact between the geomembrane and GCL due to the presence of wrinkles in the geomembrane. More data from additional sites should be evaluated before concluding that GCL underlying a geomembrane does not offer an additional benefit of minimizing leachate leakage through a geomembrane. Additionally, the inconsistency between the measured and predicted leakage rates from equations used in this field of study indicate that the models used by researchers and consultants to predict liner leakage may need to be revisited and updated to reflect the leachate leakage rates observed at MSW landfills. The authors have identified potential future research areas based on this study’s findings. A more in-depth analysis of the reasons for the inconsistency between the measured and predicted leakage rates and examining alternative equations should be considered for future research. Future research should consider collecting additional LCS, LDS, and groundwater quality data from sites with double-liner systems, which would help determine whether leachate from the LCS is the predominant component of the leachate collected from the LDS or if groundwater or another outside source of water is a larger contributor. Finally, future research should consider assessing the contact quality between the geomembrane and underlying GCL/CCL achieved with current construction practices and its impact on the leakage rate through the primary liner.

Acknowledgments

The USEPA, through its Office of Research and Development, funded and managed the research described here. This manuscript was subjected to EPA internal reviews and quality assurance approval. The research results presented in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Agency or its policy. Mention of trade names or products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

Footnotes

Supplemental Materials

There are supplemental materials associated with this paper online in the ASCE Library (www.ascelibrary.org).

Data Availability Statement

Some data (leachate collection and leak detection system flow rate, and cell footprint), models, or codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Abuel-Naga HM, and Bouazza A. 2014. “Numerical experiment-artificial intelligence approach to develop empirical equations for predicting leakage rates through GM/GCL composite liners.” Geotext. Geomembr 42 (3): 236–245. 10.1016/j.geotexmem.2014.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abunama T, Othman F, and Nilam TIT. 2021. “Comparison of landfill leachate generation and pollution potentials in humid and semi-arid climates.” Int. J. Environ. Waste Manage 27 (1): 79–92. 10.1504/IJEWM.2021.111906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Yaqout AF 2003. “Assessment and analysis of industrial liquid waste and sludge disposal at unlined landfill sites in arid climate.” Waste Manage. 23 (9): 817–824. 10.1016/S0956-053X(03)00036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson CH, Barlaz MA, Lane DT, Rawe JM, Carson D, and Tolaymat TM. 2005. State-of-the practice review of bioreactor landfills. Rep. No. EPA/600/R-09/071 Washington, DC: USEPA. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaparte R, Daniel DE, and Koerner RM. 2002. Assessment and recommendations for improving the performance of waste containment systems. Rep. No. EPA/600/R-02/099 Washington, DC: USEPA. [Google Scholar]

- Eithe AW, and Koerner GR. 1997. “Assessment of HDPE geomembrane performance in a municipal waste landfill double liner system after eight years of service.” Geotext. Geomembr 15 (4–6): 277–287. 10.1016/S0266-1144(97)10010-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiasinejad H, Ghasemi M, Pazoki M, and Shariatmadari N. 2021. “Prediction of landfill leachate quantity in arid and semiarid climate: A case study of Aradkouh, Tehran.” Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol 18 (3): 589–600. 10.1007/s13762-020-02843-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giroud JP, and Bonaparte R. 1989a. “Leakage through liners constructed with geomembranes—Part I. Geomembrane liner.” Geotext. Geomembr 8 (2): 27–67. 10.1007/s13762-020-02843-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giroud JP, and Bonaparte R. 1989b. “Leakage through liners constructed with geomembranes—Part II. Geomembrane liner.” Geotext. Geomembr 8 (5): 71–111. 10.1016/0266-1144(89)90022-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giroud JP, Khire MV, and Soderman KL. 1997. “Liquid migration through defects in a geomembrane overlain and underlain by permeable media.” Geosynth. Int 4 (3–4): 293–321. 10.1680/gein.4.0095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan M, Mohamed MH, Udoetok IA, Steiger BG, and Wilson LD. 2020. “Sequestration of sulfate anions from groundwater by biopolymer-metal composite materials.” Polymers 12 (7): 1502. 10.3390/polym12071502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). 2019. “Refinement to the 2006 IPCC guidelines for national greenhouse gas inventories” Accessed December 16, 2022. https://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2019rf/vol5.html. [Google Scholar]

- Jain P, Wally J, Townsend TG, Krause M, and Tolaymat T. 2021. “Greenhouse gas reporting data improves understanding of regional climate impact on landfill methane production and collection.” PLoS One 16 (2): e0246334. 10.1371/journal.pone.0246334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari S, and Rakesh K. 2019. “Leakage rate prediction through composite liner due to geomembrane defect using neural network.” J. Geotech. Eng 6 (Apr): 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Masoner JR, Koplin DW, Furlong ET, Cozzarelli IM, and Gray JL. 2016. “Landfill leachate as a mirror of today’s disposable society: Pharmaceuticals and other contaminants of emerging concern in final leachate from landfills in the conterminous United States.” Environ. Toxicol. Chem 16 (Aug): 2335–2354. 10.1002/etc.3219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JWF, Vasuki NC, Baker JA, and Pendleton CH. 2003. “Findings from long-term monitoring studies at MSW landfill facilities with leachate recirculation.” Waste Manage. 23 (3): 653–666. 10.1016/S0956-053X(03)00098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NARA (National Archives and Records Administration). 2021. “Standards for owners and operators of hazardous waste, treatment, storage, and disposal facilities.” Accessed December 16, 2022. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-40/chapter-I/subchapter-I/part-264. [Google Scholar]

- NHCAR (New Hampshire Code of Administrative Rules). 2020. “New Hampshire code of administrative rules: Chapter Env-Sw 800 landfill requirements.” Accessed October 20, 2022. https://www.des.nh.gov/sites/g/files/ehbemt341/files/documents/2020-01/Env-Sw%20800.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Park JK, Chong YG, Tameda K, and Lee NH. 2018. “Methods for determining the methane generation potential and methane generation rate constant for the FOD model: A review.” Waste Manage. Res 36 (3): 200–220. 10.1177/0734242X17753532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelt RL 1993. Memorandum: Methodology used to revise the model inputs in the municipal solid waste landfills input data bases (revised), to the municipal solid waste landfills docket No. A-88-09. Washington, DC: USEPA. [Google Scholar]

- Podlasek A, Jakimiuk A, Vaverková MD, and Koda E. 2021. “Monitoring and assessment of groundwater quality at landfill sites: Selected case studies of Poland and the Czech Republic.” Sustainability 13 (14): 7769. 10.3390/su13147769. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe RK, and Fan J. 2022. “A general solution for leakage through geomembrane defects overlain by saturated tailings and underlain by highly permeable subgrade.” Geotext. Geomembr 50 (4): 694–707. 10.1016/j.geotexmem.2022.03.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder PR, Dozier TS, Zappi PA, McEnroe BM, Sjostrom JW, and Peyton RL. 1994. The hydrologic evaluation of landfill performance (HELP) model: Engineering documentation for version 3. Rep. No. EPA/600/R-94/168b Washington, DC: USEPA. [Google Scholar]

- Tatsi AA, and Zouboulis AI. 2002. “A field investigation of the quantity and quality of leachate from a municipal solid waste landfill in a Mediterranean climate (Thessaloniki, Greece).” Adv. Environ. Res 6 (3): 207–219. 10.1016/S1093-0191(01)00052-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Touze-Foltz N, and Giroud JP. 2003. “Empirical equations for calculating the rate of liquid flow through composite liners due to geomembrane defects.” Geosynth. Int 10 (6): 215–233. 10.1680/gein.2003.10.6.215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- USEPA. 1993. Quality assurance and quality control for waste containment facilities. Rep. No. EPA/600/R-93/182 Washington, DC: USEPA. [Google Scholar]

- USEPA. 2008. Background information document for updating AP42 Section 2.4 for estimating emissions from municipal solid waste landfills. Rep. No. EPA/600/R-08-116 Washington, DC: USEPA. [Google Scholar]

- Vu HL, Ng KTW, and Richter A. 2017. “Optimization of first order decay gas generation model parameters for landfills located in cold semi-arid climates.” Waste Manage. 69 (Jun): 315–324. 10.1016/j.wasman.2017.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Some data (leachate collection and leak detection system flow rate, and cell footprint), models, or codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.