Abstract

Background

The identification of serious pathologies, such as spinal malignancy, is one of the primary purposes of the clinical assessment of patients with low‐back pain (LBP). Clinical guidelines recommend awareness of "red flag" features from the patient's clinical history and physical examination to achieve this. However, there are limited empirical data on the diagnostic accuracy of these features and there remains very little information on how best to use them in clinical practice.

Objectives

To assess the diagnostic performance of clinical characteristics identified by taking a clinical history and conducting a physical examination ("red flags") to screen for spinal malignancy in patients presenting with LBP.

Search methods

We searched electronic databases for primary studies (MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL) and systematic reviews (PubMed and Medion) from the earliest date until 1 April 2012. Forward and backward citation searching of eligible articles was also performed.

Selection criteria

We considered studies if they compared the results of history taking and physical examination on patients with LBP with those of diagnostic imaging (magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, myelography).

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed the quality of each included study with the QUality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS) tool and extracted details on patient characteristics, study design, index tests, and reference standard. Diagnostic accuracy data were presented as sensitivities and specificities with 95% confidence intervals for all index tests.

Main results

We included eight cohort studies of which six were performed in primary care (total number of patients; n = 6622), one study was from an accident and emergency setting (n = 482), and one study was from a secondary care setting (n = 257). In the six primary care studies, the prevalence of spinal malignancy ranged from 0% to 0.66%. Overall, data from 20 index tests were extracted and presented, however only seven of these were evaluated by more than one study. Because of the limited number of studies and clinical heterogeneity, statistical pooling of diagnostic accuracy data was not performed.

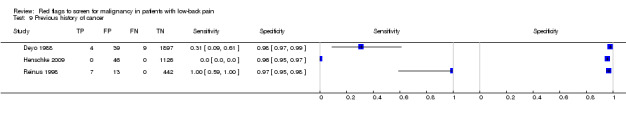

There was some evidence from individual studies that having a previous history of cancer meaningfully increases the probability of malignancy. Most "red flags" such as insidious onset, age > 50, and failure to improve after one month have high false positive rates.

All of the tests were evaluated in isolation and no study presented data on a combination of positive tests to identify spinal malignancy.

Authors' conclusions

For most "red flags," there is insufficient evidence to provide recommendations regarding their diagnostic accuracy or usefulness for detecting spinal malignancy. The available evidence indicates that in patients with LBP, an indication of spinal malignancy should not be based on the results of one single "red flag" question. Further research to evaluate the performance of different combinations of tests is recommended.

Keywords: Humans, Middle Aged, Physical Examination, Cohort Studies, Confidence Intervals, Low Back Pain, Low Back Pain/etiology, Medical History Taking, Sensitivity and Specificity, Spinal Neoplasms, Spinal Neoplasms/complications, Spinal Neoplasms/diagnosis

Plain language summary

Physician use of red flags to screen for cancer in patients with new back pain

This review describes the understanding of a common practice for checking for spinal injuries when patients come to a family practice doctor, back pain clinic or emergency room with new back pain. Doctors usually ask a few questions and examine the back to check for the possibility of a spinal tumor. The reason for this check for tumors is that the treatment is different for common back pain and tumors. Tumors are usually diagnosed with an x‐ray, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT), then treated with surgery and/or chemotherapy. Common back pain is treated with exercise, spinal manipulation, and pain relievers; x‐rays, CT and MRI scans are not useful for diagnosis. Tumors are rare, being the cause of back pain in approximately 1% of new back pain visits to family doctors. Only about 10% of these cancers are new cases; 90% are recurrences of cancers from other parts of the body (metastases).

Six family practice studies including over 6,600 back pain patients found 21 tumors (0.3%). One study on back pain diagnosed in an emergency room and one on back pain in a spine clinic included 482 and 257 patients. The family practice studies described 15 different questions and physical exam tests that have been used to screen for spinal tumors. Most of the 15 were not accurate. A previous history of cancer is a very useful indicator. Other facts that may indicate cancer are age greater than 50, no prior history of back pain, and failure to improve after one month. These are most likely useful when combined, or with other indicators such as a history of cancer. By themselves, these three questions would result in over‐testing of patients without cancer.

The worst effects of low quality red flag screening are overtreatment and undertreatment. If the tests are not accurate, patients without a tumor may get an x‐ray, MRI, bone scan or CT scan that they don’t need—unnecessary exposure to x‐rays, extra worry for the patient and extra cost. At the other extreme (and much less common), it might be possible to miss a real tumor, and cause the patient to have extra time without the best treatment.

Most of the studies were of low or moderate quality and did not use an MRI, the most accurate imaging test, to confirm the presence or absence of a tumor, so more research is needed to identify the best combination of questions and examination methods.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings'. 'Summary of Results.

|

Review question: What is the accuracy of red flags to screen for malignancy in patients presenting with low‐back pain or for lumbar examination? Patient population: Patients with low‐back pain or requiring examination of the lumbar spine when presenting to care in primary or secondary settings. Index tests: All relevant features taken during a history or physical examination. Target condition: Spinal malignancy. Reference standard: Diagnostic imaging (MRI, CT, X‐ray, bone scan), long‐term follow‐up. Study setting and total number of patients: Primary care (6 studies) 6622 patients; secondary care (1 study) 257 patients; accident and emergency (1 study) 482 patients. Main limitations: Small number of studies included; large heterogeneity between studies and index tests prevented pooling of results; descriptive analysis presented; inadequate reporting of methods. Applicability of tests in clinical practice: The strength of our recommendations is limited by the small number of studies identified on this topic. Equally important is the fact that most studies only presented the diagnostic value of individual "red flags". Our review shows that when carried out in isolation, the diagnostic performance of most tests (with the exception of a previous history of cancer) is poor. | |||

| Index test | Setting | Positive predictive value (PPV) or range of values | Post‐test probability after positive screening test result for a patient with moderate risk (0.3% pre‐test probability) disease^ |

| Age > 50 | Primary care (4 studies) | 0% to 1.8% | 0.8% |

| Secondary care (1 study) | 11.4% | 12%* | |

| Age > 70 | Primary care (1 study) | 0% | 0.3% |

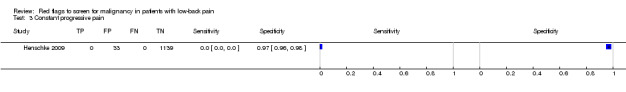

| Constant progressive pain | Primary care (1 study) | 0% | 0.3% |

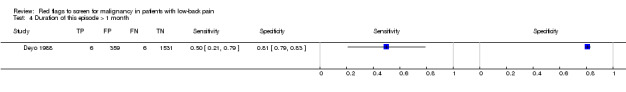

| Duration of this episode > 1 month | Primary care (1 study) | 1.6% | 0.8% |

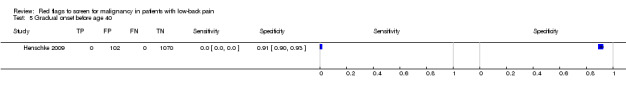

| Gradual onset before age 40 | Primary care (1 study) | 0% | 0.3% |

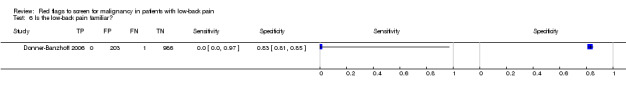

| Is the low‐back pain familiar? | Primary care (1 study) | 0% | 0.3% |

| Insidious onset | Primary care (2 studies) | 0% to 0.7% | 0.3% |

| Not improved after 1 month | Primary care (2 studies) | 1.7% to 2.0% | 0.9% |

| Previous history of cancer | Primary care (2 studies) | 0% to 9.3% | 4.6% |

| Accident & emergency (1 study) | 35% | 50%** | |

| Recent back injury | Primary care (1 study) | 0% | 0.3% |

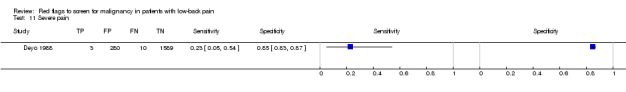

| Severe pain | Primary care (1 study) | 1.1% | 0.5% |

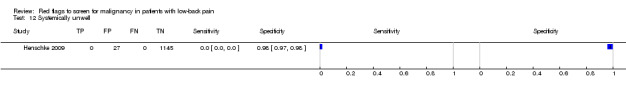

| Systemically unwell | Primary care (1 study) | 0% | 0.3% |

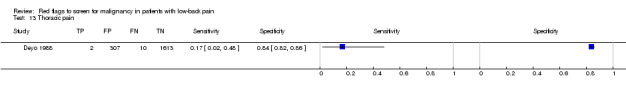

| Thoracic pain | Primary care (1 study) | 0.7% | 0.3% |

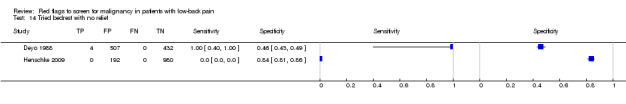

| Tried bedrest with no relief | Primary care (2 studies) | 0% to 0.8% | 0.6% |

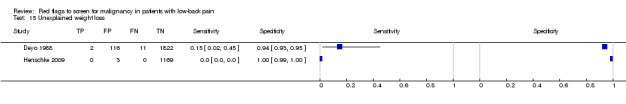

| Unexplained weight loss | Primary care (2 studies) | 1.7% | 1.2% |

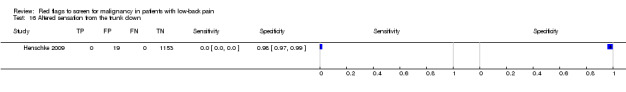

| Altered sensation from the trunk down | Primary care (1 study) | 0% | 0.3% |

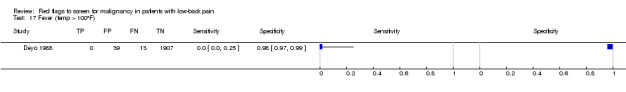

| Fever (temp > 100oF) | Primary care (1 study) | 0% | 0.3% |

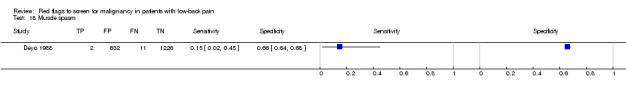

| Muscle spasm | Primary care (1 study) | 0.3% | 0.1% |

| Neurological symptoms | Primary care (2 studies) | 0% | 0.3% |

| Spine tenderness | Primary care (1 study) | 0.3% | 0.1% |

^ Where more than one study, post‐test probability is calculated using highest positive likelihood ratio

* Calculated using a pre‐test probability of 7%

** Calculated using a pre‐test probability of 1.5% CT: computed tomography MRI: magnetic resonance imaging

Background

Low‐back pain (LBP) is a common cause of disability and one of the main reasons for healthcare expenditure around the world, especially in high‐income countries. While up to 70% of people will experience at least one episode of LBP in their lifetime (Koes 2006), no specific pathology can be identified in up to 85% of patients (Deyo 1992). The difficulty in providing a definitive diagnosis has given rise to the term "non‐specific LBP", which is generally considered to be benign and can be managed in a primary care setting (Koes 2010). However, a small proportion of patients present with LBP as the initial manifestation of a more serious pathology, such as spinal malignancy, vertebral fracture, infection, or cauda equina syndrome. The prevalence of these serious spinal pathologies has been estimated to be between 1% and 5% of all primary care patients with LBP (Deyo 1992; Henschke 2009).

The identification of serious pathologies is one of the primary purposes of the clinical assessment of patients with LBP and clinical guidelines recommend awareness of "red flags" as the ideal method to accomplish this purpose (Koes 2010). "Red flags" are features from the patient's clinical history and physical examination which are thought to be associated with a higher risk of serious pathology. The presence of a "red flag" should alert clinicians to the need for further examination and in most cases, specific management (Waddell 2004). As most clinical guidelines explicitly recommend against the use of routine diagnostic imaging for patients with LBP, it is important to determine whether "red flags" can be used to aid a clinician's judgment when screening for spinal malignancy.

Target condition being diagnosed

In this review we focus on red flags for spinal malignancies. Spinal malignancies are, after vertebral fracture, the most common serious pathologies affecting the spine and are estimated to be present in around 1% of primary care patients presenting with LBP (Deyo 1992; Henschke 2009). However, given the prevalent nature of LBP, the number of patients presenting to primary care with spinal malignancy is substantial and there exists a need for effective diagnostic strategies.

The spine is much more frequently affected by metastatic disease than it is the site of primary tumours. Approximately 10% of all malignancies have symptomatic spine involvement as the initial manifestation of the disease, including multiple myeloma, non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma, and carcinoma of the lung, breast, and prostate (Sciubba 2006). Early detection and treatment of spinal malignancies are important to prevent further spread of metastatic disease and the development of complications such as vertebral fracture and spinal cord compression (Loblaw 2005). The consequences of a late or missed diagnosis of spinal malignancy necessitate the use of accurate screening tools, specifically for patients presenting with LBP. Ideally, clinicians should be able to identify the small number of patients with a higher likelihood of spinal malignancy at an early stage without subjecting a large proportion of their patients with LBP to unnecessary diagnostic testing.

Index test(s)

Clearly, the prevalence of spinal malignancy is insufficient to warrant imaging studies or laboratory tests on all patients. As a first step in identifying spinal malignancy, clinical practice guidelines generally recommend assessing for the following "red flags": a previous history of cancer, unexplained weight loss, or age greater than 50 years (Deyo 1992). However, there are few empirical data on the accuracy of these features and most clinical features considered to be "red flags" for malignancy are derived from one study (Deyo 1988). The inclusion of these features in the guidelines has often been poorly justified by reference to previous guidelines (van Tulder 2004) and unpublished data (Bigos 1994). Despite their inclusion in the guidelines, the usefulness of screening for "red flags" for malignancy in patients with LBP continues to be debated (Underwood 2009) and there remains very little information on their diagnostic accuracy and how best to use them in clinical practice.

In 2007, we published a systematic review of six studies that evaluated a total of 22 clinical features used to screen patients with LBP for malignancy (Henschke 2007). The review found that four clinical features (used in isolation) were useful to raise the probability of malignancy: a previous history of cancer (positive likelihood ratio (LR+) = 23.7), elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (LR+ = 18.0), reduced haematocrit (LR+ = 18.2), and overall clinician judgment (LR+ = 12.1) (Henschke 2007). The review also noted that the available studies were generally of poor quality, according to the criteria of the QUality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS) checklist, and very few studies were carried out in the primary care setting, where "red flags" could potentially be of most benefit. This systematic review also included results from laboratory tests and clinician judgment as "red flags" for malignancy. These laboratory tests and an overall clinician judgment are subject to referral filter and incorporation biases as they are only performed if indicated (or containing features) from the clinical history or physical examination.

Alternative test(s)

In the absence of accurate information about the diagnostic accuracy of "red flags", clinicians are left with the prospect of routine diagnostic imaging of all patients with LBP to exclude spinal malignancy. Diagnostic imaging of spinal malignancy can include plain radiography, nuclear scintigraphy (or bone scanning), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Jarvik 2002; Joines 2001; Sciubba 2006).

Due to availability and low cost, plain radiographs have usually served as an initial screening test for spinal malignancy by revealing lytic or sclerotic areas of bone, pathologic compression fractures, deformity, and paraspinal masses. The major proportion of spinal metastatic lesions are osteolytic, but up to 50% of the bone must be eroded before there is a noticeable change on plain radiographs (Sciubba 2006). Nuclear scintigraphy or bone scanning is sensitive for identifying increased metabolic activity throughout the entire skeletal system, and finds cancer at an earlier stage than plain radiography. However, the poor image resolution and low specificity of both plain radiographs and nuclear scintigraphy requires correlation with CT or MRI to exclude benign processes (Sciubba 2006).

Magnetic resonance imaging is considered the gold standard imaging modality for assessing spinal metastatic disease. It has a reported sensitivity of between 83% and 93% and specificity between 90% and 97% (when compared to autopsy or surgery) for detecting spinal malignancy (Joines 2001). Such high sensitivity is due to the fact that MRI gives superior resolution of soft‐tissue structures. Moreover, MRI provides clarity at the bone‐soft tissue interface, yielding accurate anatomic detail of bony compression or invasion of neural and paraspinal structures. The MRI protocol should include T1‐ (which highlight fat deposition) and T2‐ (which highlight liquid) weighted images and contrast‐enhanced studies, that provide axial, sagittal, and coronal reconstructions (Joines 2001; Sciubba 2006).

Rationale

In light of recently published, pertinent primary diagnostic studies (Henschke 2009) and evolving guidance for the most appropriate methods to systematically review studies of diagnostic test accuracy (Deeks 2009), we decided to update our previous systematic review using the methods recommended by the Cochrane Diagnostic Test Accuracy (DTA) Working Group. The protocol for this review was largely based upon the first DTA review published within the Cochrane Back Review Group (CBRG) (van der Windt 2010). In order to assess the diagnostic accuracy of "red flags" to identify the most common serious spinal pathologies presenting as LBP, this review will be performed concurrently with another Cochrane review on the diagnostic test accuracy of "red flags" for vertebral fracture (Henschke 2010).

Objectives

The objective of this systematic review is to assess the diagnostic performance of clinical characteristics ("red flags") identified by taking a clinical history and conducting a physical examination to screen for spinal malignancy in patients presenting with LBP, as assessed by diagnostic imaging. This information may assist clinicians to make decisions about appropriate management in patients with LBP.

Investigation of sources of heterogeneity

The secondary objective of this review is to assess the influence of sources of heterogeneity on the diagnostic accuracy of "red flags" for spinal malignancy. We aim to examine the influence of the healthcare setting (e.g. primary or secondary care), the study design (e.g. consecutive series or case‐control), and aspects of study quality as reflected in the assessment of the items of the QUADAS checklist.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Primary diagnostic studies were considered if they compared the results of taking a history and completing a physical examination for the identification of spinal malignancy in patients with LBP, with those of a reference standard. The main focus of the review was on studies using a cross‐sectional or prospective design which present sufficient data to allow calculation of estimates of diagnostic accuracy (such as sensitivity and specificity), which are reported in full publications. Case‐control studies were also considered if insufficient primary diagnostic studies were identified. If studies were reported in abstracts or conference proceedings, we retrieved the full publications where possible. Studies published in all languages were included in this review. Where necessary, appropriate translation of potentially eligible articles was sought.

Participants

Studies were included if they evaluated adult patients who presented to primary or secondary care settings for treatment of LBP or for lumbar spine examination. Longitudinal studies in which more than 10% of recruited patients had already been diagnosed with spinal malignancy as the likely cause of their LBP were excluded. This proportion was chosen based on a consensus among the review team, in an attempt to minimise referral bias.

Index tests

Studies evaluating any aspects of the history taking or physical examination of patients with LBP were eligible for inclusion. This included demographic characteristics (e.g. age, gender), the clinical history (e.g. pain intensity or a previous history of cancer), and results of the physical examination (e.g. tenderness/pain on palpation, lumbar range of motion, or muscle strength). Studies were included if the diagnostic accuracy of the individual "red flags" were evaluated in isolation, or as part of a combination. Studies in which only a "clinical diagnosis" or "global clinician judgment" (without specifying which diagnostic tools were used) were compared with a reference standard were excluded from this review. An undefined clinical judgment represents an individual clinician's diagnostic ability, rather than providing useful data on clearly defined patient characteristics.

Target conditions

All studies that reported results of the history taking or physical examination in detecting spinal malignancy in patients who presented for management of LBP were included. Where possible, we described separate results for primary tumours and secondary metastases.

Reference standards

Studies were included if "red flags" were compared with diagnostic imaging procedures such as plain radiographs, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and bone scans to confirm the presence of cancer or malignancy in the spine. Long‐term (> six months) follow‐up of patients after the initial consultation was also considered an appropriate reference standard, if suspected cases of malignancy were confirmed by medical records or specialist review.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The search strategy to be used was developed in collaboration with a medical information specialist. Relevant computerised databases were searched for eligible diagnostic studies from the earliest year possible until 1 April 2012, including MEDLINE (PubMed), OLDMEDLINE (PubMed), EMBASE (embase.com), and CINAHL (Ebsco). The search strategy for MEDLINE is presented in Appendix 1 and was adapted for EMBASE (Appendix 2) and CINAHL (Appendix 3). A previous systematic review on the diagnostic performances of "red flags" for spinal malignancy was used as a point of reference (Henschke 2007). All publications included in that review are indexed in MEDLINE, so the current search strategy was refined until all publications from the previous review were identified by the search. The strategy uses several combinations of searches related to the patient population, history taking, physical examination, and the target condition.

Searching other resources

The reference lists of all included publications were checked and all included studies were subjected to a forward citation search using Science Citation Index. A further electronic search was composed to identify relevant (systematic) reviews in MEDLINE and Medion (www.mediondatabase.nl), from which reference lists were checked. In addition, we contacted experts in the field of LBP research to identify diagnostic studies missed by the search strategy.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The selection criteria and the QUADAS checklist were first piloted on selected diagnostic studies to ensure consistency among the review team. Two review authors (NH and RO) then independently applied the selection criteria to all citations (titles and abstracts) identified by the search strategy described above. Consensus meetings were organised to discuss any disagreement regarding selection. Final selection was based on a review of full publications, which were retrieved for all studies that either met the selection criteria, or for which there was uncertainty regarding selection. The other review authors were consulted in cases of persisting disagreement.

Data extraction and management

A data extraction form was specifically designed to collect details from included studies. For each study, the characteristics of participants, index tests, reference standards, and study methods were recorded and presented in tables.

Characteristics of participants (and studies) included details on the setting (location, type of clinic); inclusion and exclusion criteria; enrolment procedures (consecutive or non‐consecutive); number of participants (including number eligible for the study, number enrolled in the study, number receiving the index test and reference standard, number for whom results are reported in the two‐by‐two table); reasons for withdrawal; patient demographics (age, gender); and duration and history of LBP.

Test characteristics included the type of index test; methods of execution; experience and expertise of the assessors; type of reference standard; and where relevant, cut‐off points for diagnosing malignancy.

Aspects of study methods were reflected in the quality assessment criteria (Appendix 4).

Data for diagnostic two‐by‐two tables (true positive, false positive, true negative, and false negative numbers) were extracted from the publications or reconstructed using information from other relevant parameters (sensitivity, specificity, or predictive values). Two review authors (NH and RO) independently extracted the data to ensure adequate reliability of collected data. Where a review author was also an author of one of the primary diagnostic studies, they were not involved in the data extraction or quality rating of this study.

Assessment of methodological quality

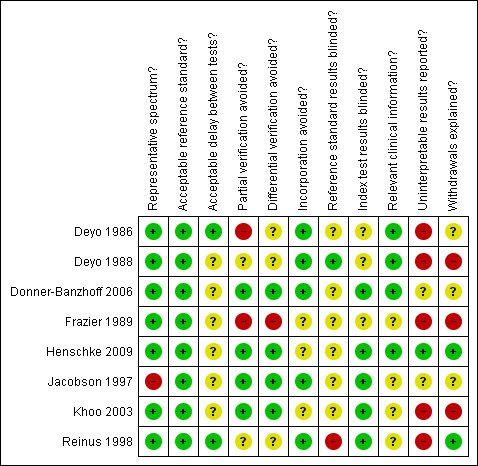

The methodological quality of each study was assessed by two review authors (NH and RO) using the QUADAS checklist (Whiting 2003). The Cochrane Diagnostic Test Accuracy Working Group recommends assessment of 11 QUADAS items that refer to internal validity (e.g. blind assessment of index and reference test, or avoidance of verification bias) (Appendix 4; Deeks 2009).

The review authors classified each item as "yes" (adequately addressed); "no" (inadequately addressed); or "unclear" (inadequate detail presented to allow a judgment to be made). Guidelines for the assessment of each item were made available to the review authors (Appendix 4). Disagreements were resolved by discussion and if necessary, by consulting a third review author (CGM).

The 11 items of the QUADAS checklist were considered individually for each study, without the application of weights or the use of a summary score to select studies with certain levels of quality in the analysis. Where possible, the influence of negative or unclear classification of important items were explored as potential sources of heterogeneity. The following items were considered for these analyses as they have been shown to affect diagnostic performance in previous research (van der Windt 2010): item one (spectrum variation / selective sample), item two (adequate reference standard), item four (verification bias), item five (same reference standard), items seven and eight (blinded interpretation of index test and reference standard), and item 11 (explanation of withdrawals).

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

Indices of diagnostic performance were extracted or derived from data presented in each primary study for each "red flag" or combination of "red flags". Diagnostic 2x2 tables were generated, from which sensitivities and specificities for each index test with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated and presented in forest plots. Positive and negative likelihood ratios with 95% CIs were also calculated for each index test.

Pooling of sensitivity and specificity results was intended if studies showed sufficient clinical homogeneity (e.g. same index test, similar definition of malignancy). However, due to the limited number of eligible studies as well as heterogeneity in the design and setting within those studies evaluating the same index test, pooling of diagnostic accuracy data was not performed. A descriptive analysis of the results, including the prevalence of spinal malignancy in the study populations along with measures of diagnostic performance is presented.

Investigations of heterogeneity

The potential influence of the healthcare setting, the study design, and aspects of study quality from the QUADAS checklist on estimates of diagnostic accuracy, can only be investigated if a sufficiently large number of studies report on the same index test and provide adequate information on the factor of interest. This was not the case in the current review, as the number of studies investigating each test was too small to allow investigation of sources of heterogeneity.

Results

Results of the search

The electronic search of the MEDLINE, CINAHL and EMBASE databases resulted in 2082 unique titles. After screening of titles and abstracts, full text copies of 66 articles were retrieved. Apart from the systematic review used as a point of reference for this search (Henschke 2007), which included six primary studies, we were unable to identify any other systematic reviews on this topic. After reviewing the full text of the 66 selected articles, both review authors (NH, RO) agreed on the inclusion of eight studies (Figure 1). Only two case‐control studies were identified, which were excluded because of poor methodology (Characteristics of excluded studies).

1.

Flow diagram of search strategy

The reference lists of these eight studies were checked and forward citation searching was performed, but this did not result in any further eligible studies. Details on the design, setting, population, reference standard and definition of the target condition are provided in the Characteristics of included studies table. Of the eight included studies, six were performed in a primary care setting (Deyo 1986; Deyo 1988; Donner‐Banzhoff 2006; Frazier 1989; Henschke 2009; Khoo 2003), one was performed in an accident and emergency department (Reinus 1998), and one was performed in a secondary care setting (Jacobson 1997). Six studies used a prospective design (Deyo 1986; Deyo 1988; Donner‐Banzhoff 2006; Henschke 2009; Khoo 2003; Reinus 1998) and two studies collected information from medical records (Frazier 1989; Jacobson 1997). Five of the included studies were on a cohort of patients presenting with LBP (Deyo 1986; Deyo 1988; Donner‐Banzhoff 2006; Frazier 1989; Henschke 2009), while three studies evaluated the diagnostic yield of imaging tests of the lumbar spine (Jacobson 1997; Khoo 2003; Reinus 1998).

The six studies conducted in primary care had a total sample size of 6622 patients, and the observed prevalence of spinal malignancy (21 cases) in the primary care studies ranged from 0% (Henschke 2009) to 0.66% (Deyo 1988). The primary diagnostic study by Henschke 2009 did not identify any cases of malignancy in 1172 consecutive cases of LBP, so sensitivity of the index tests could not be estimated for this study. In the accident and emergency setting (n = 482), the prevalence was reported as 1.45% (Reinus 1998) and in secondary care (n = 257) the prevalence was 7% (Jacobson 1997).

The reference standards used in the included studies were either diagnostic imaging (Deyo 1986; Khoo 2003; Reinus 1998; Jacobson 1997), long‐term follow‐up (Donner‐Banzhoff 2006; Henschke 2009), or a combination of both (Deyo 1988; Frazier 1989). All studies evaluated individual tests from the clinical history or physical examination. No studies provided data on a combination of tests to screen for spinal malignancy.

Methodological quality of included studies

The results of the methodological quality assessment are shown in Figure 2. Most of the included studies were performed on a representative spectrum of patients (87.5%), avoided incorporation of the index tests in the reference standard (62.5%), and performed the index test in a blinded manner (62.5%). Only one study (Henschke 2009) provided adequate reporting of uninterpretable test results and explained withdrawals from the study. There was poor reporting of the time delay between the index tests and reference standard and whether the reference standard was blinded. Overall, three of the eight included studies (Donner‐Banzhoff 2006; Henschke 2009; Reinus 1998) fulfilled six or more of the 11 methodological quality items.

2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Findings

The heterogeneity between the studies identified by the review meant statistical pooling of diagnostic accuracy data was not warranted. A descriptive analysis was performed from extracted data (2x2 tables) and sensitivity and specificity for all index tests. In total, data from 20 index tests (including two cut‐offs for age) from the clinical history and physical examination were extracted. Of these, only seven were evaluated by more than one study and only two were evaluated by more than two studies.

Only one study (Deyo 1988) discussed the diagnostic accuracy of a combination of index tests. This study reported in the discussion section that a combination of age greater than 50 years, history of cancer, unexplained weight loss, or failure to improve with conservative therapy had a sensitivity of 100% for detecting malignancy. No further data on this combination of tests were provided.

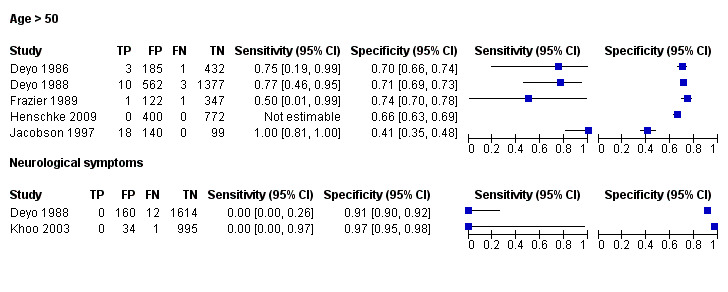

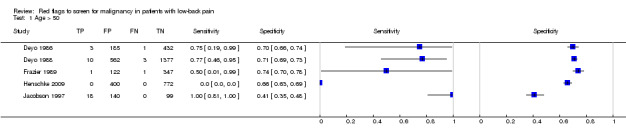

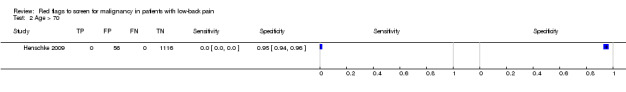

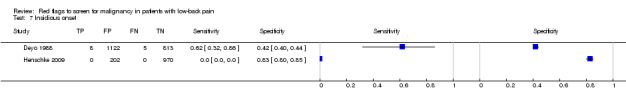

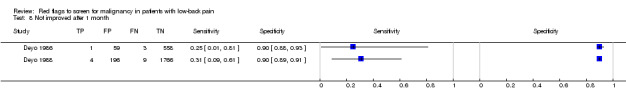

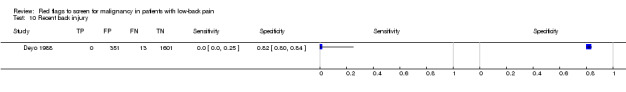

Clinical history

From seven of the included studies, 15 index tests derived from the clinical history were evaluated. Six of these tests were evaluated by more than one study. The most common index test was older age, with a cut‐off at greater than 50 years being evaluated by five studies (Deyo 1986; Deyo 1988; Frazier 1989; Henschke 2009; Jacobson 1997). Within the four primary care studies (Deyo 1986; Deyo 1988; Frazier 1989; Henschke 2009), the specificity (95% CI) of this test ranged from 0.66 (0.63 to 0.69) to 0.74 (0.70 to 0.78), the sensitivity ranged from 0.50 (0.01 to 0.99) to 0.77 (0.46 to 0.95), and the positive likelihood ratio (LR+) ranged from 1.92 to 2.65 (Figure 3). Of the remaining index tests from the clinical history, a previous history of cancer (three studies), no improvement in pain after one month (two studies), and unexplained weight loss (two studies) appeared to have high specificity across studies. Having an insidious onset of pain (two studies) or trying bed rest with no relief (two studies) had more inconsistent specificity across studies.

3.

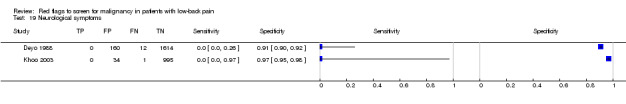

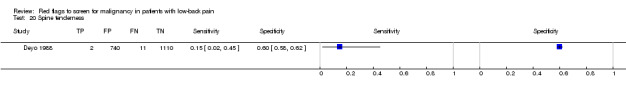

Forest plot of sensitivity and specificities for: Age > 50 and Neurological symptoms.

In the primary care setting, the post‐test probability following a positive red flag from the clinical history remained below 1% in most cases (Table 1). Unexplained weight loss (post‐test probability 1.2%) and a previous history of cancer (post‐test probability 4.6%) were the only exceptions. In the accident and emergency setting, a previous history of cancer had a LR+ of 31.67 (Reinus 1998).

Physical examination

Three included studies evaluated aspects of the physical examination (Deyo 1988; Henschke 2009; Khoo 2003). Of the five index tests, only neurological symptoms (two studies) were evaluated by more than one study. The other four index tests were altered sensation from the trunk down, fever (temp > 100oF), muscle spasm, and spine tenderness. The sensitivity was zero in both studies while the specificity ranged from 0.91 (0.90 to 0.92) to 0.97 (0.95 to 0.98).

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review aimed to summarise evidence for the accuracy of "red flags" to screen for malignancy in patients with low‐back pain (LBP). An important finding is the low prevalence reported in the included studies, with less than 1% of patients presenting to primary care with LBP being diagnosed with spinal malignancy. The results show that diagnostic performance of most "red flags" (clinical history and physical examination tests) is poor, especially when used in isolation. The exception was a previous history of cancer which had a sufficiently high positive likelihood ratio (LR+) to meaningfully increase the probability of malignancy. Only seven out of the 20 "red flags" were evaluated by more than one study. This means that there is insufficient evidence to support or refute the clinical usefulness of most "red flags" to screen for spinal malignancy in patients with LBP. There were very limited possibilities to study the influences of sources of heterogeneity in this review. Apart from the small number of studies per index test, studies did not always provide sufficient information about important study characteristics.

Factors affecting interpretation

Population and setting

The primary care setting plays a vital role in early detection of serious disease and it is there that reliable and accurate diagnostic information is needed. Most of the included studies were carried out in a primary care setting using a prospective design, evaluating "red flags" only once, at the initial consultation. However, persons presenting for a second, third, or subsequent consultation because of pain that is not resolving may not have been evaluated by the included studies. Spinal malignancy can develop in patients with established LBP and thus cannot be disregarded irrespective of the duration of LBP. Three included studies were also performed on a cohort of patients referred for diagnostic imaging of the lumbar spine, rather than on a consecutive series of patients presenting with LBP. This will likely overestimate the diagnostic accuracy results of the "red flags", as patients with LBP who are not referred for imaging will be automatically excluded.

Reference standard

The most common reference standard used was long‐term (six to 12 months) and complete follow‐up of patients. It is assumed in these cases that any spinal malignancy would manifest over time and be identified without the need for all patients to undergo diagnostic imaging. However, the use of follow‐up may result in missed cases of serious disease if the follow‐up consists of reviewing medical records or tumour registries (Deyo 1988), as patients may seek care elsewhere. There is also a possibility that spinal malignancy could develop subsequent to the initial consultation for non‐specific LBP. Despite considering studies from all settings, only two studies were identified from the accident and emergency or secondary care setting. While MRI is generally considered the "gold standard" for diagnosing spinal malignancy, no studies utilised this form of imaging as the reference standard for all patients.

Index tests

Using "red flags" to screen for serious pathologies in patients with LBP would ideally involve identifying features which, when present, raise the index of suspicion of having the disease to a level that would suggest further diagnostic work‐up. Of the four red flags endorsed in the recent American Pain Society guideline (Chou 2007) to indicate a higher likelihood of malignancy (unexplained weight loss, age > 50, failure to improve after one month, previous history of cancer) only a previous history of cancer increased the post‐test probability of malignancy beyond 2%. The other three red flags, used in isolation, have modest LR+ and in the case of older age and failure to improve after one month, have substantial false positive rates which argues against their recommended use in clinical practice. Some red flags (e.g. thoracic pain, severe pain, insidious onset) have both LR+ and LR‐ that are close to 1, suggesting that these red flags are of no value in either increasing or decreasing the likelihood of malignancy. The large number of patients with false positive "red flag" symptoms is of concern, as the presence of a "red flag" will not help the clinician in deciding whether any further investigation or treatment is needed.

In the primary care setting, screening to exclude patients who do not have malignancy is often more appropriate than identifying the few cases of malignancy. While some red flags have been endorsed because they have a very low LR‐ and so help to reduce the likelihood of malignancy, it needs to be borne in mind that the prevalence of malignancy in primary care patients with LBP is very low. The starting position is that malignancy is unlikely and with a negative test result malignancy becomes highly unlikely. A negative response to these tests would only change clinical management for clinicians who would order a diagnostic work‐up when the probability of malignancy is around 1%.

The low prevalence of spinal malignancy in patients with LBP makes it difficult to develop screening tools which are both easy to apply and accurate. Clinical guidelines usually suggest individual "red flags" and leave their interpretation up to the clinician (Koes 2010). A more effective screening tool could be recommended if data were available on how to use these "red flags" in combination with each other. When a number of positive "red flags" is used in combination, the LR+ would most likely be increased. This also becomes a more accurate reflection of what takes place in clinical practice. Additionally, as the spine is more frequently the site of metastatic disease than primary tumours, "red flags" may become more useful where the target population is not all patients seeking care for LBP but those with LBP and (for example) a history of cancer. As an example, an insidious onset of LBP in a patient aged over 50 years, with no prior history of LBP but a history of cancer, may indicate a higher likelihood of malignancy. Ideally, an effective series of "red flag" questions for spinal malignancy would highlight pertinent characteristics from the patient’s history and physical examination, and allow the clinician to forego invasive and potentially harmful tests, to identify all patients who require further assessment.

Strengths and weaknesses of the review

Despite employing a sensitive electronic search strategy, very few eligible studies were available. Poor reporting in the original publications affected the assessment of methodological quality (risk of bias) and was one of the main reasons for scoring "unclear" on some QUADAS items. Most studies were not specifically designed as diagnostic accuracy studies and so provided little information on important aspects of study design. The introduction and implementation of the STARD guidelines may improve reporting of diagnostic studies in the future (Bossuyt 2003; Smidt 2006). Assessment of quality in the current review was facilitated by defining clear guidelines for review authors on how to score individual items (Appendix 4).

Applicability of findings to the review question

Clinical practice guidelines for the management of LBP typically recommend that at the initial assessment, the need for further diagnostic work‐up for those suspected of having an underlying serious disorder (e.g. fracture, spinal malignancy) should be guided by the presence of a number of "red flag" questions (Koes 2010). The objective of this review was to provide researchers and clinicians with a clearer definition of which "red flags", and in what combination, are useful to screen for spinal malignancy, and identify in which situations it is appropriate to use them in the management of LBP. However, the strength of our recommendations is limited by the small number of studies identified on this topic. Equally important is the fact that most studies only presented the diagnostic value of individual "red flags". Our review shows that when carried out in isolation, the diagnostic performance of most tests (with the exception of a previous history of cancer) is poor. It is arguable that in clinical practice the combination of several elements of diagnostic information will contribute to estimating the likelihood of serious pathology such as malignancy.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Commonly suggested "red flags" for malignancy in clinical practice guidelines are: age > 50 years, no improvement in symptoms after one month, insidious onset, a previous history of cancer, no relief with bed rest, unexplained weight loss, fever, thoracic pain, or being systematically unwell (Koes 2010). These "red flags" are usually elicited through the initial assessment (history taking and physical examination), to decide which patients should be referred for imaging or specialist consultation. The limited evidence available suggests that only one "red flag" when used in isolation, a previous history of cancer, meaningfully increases the likelihood of cancer. "Red flags" such as insidious onset, age > 50, and failure to improve after one month have high false positive rates suggesting that uncritical use of these "red flags" as a trigger to order further investigations will lead to unnecessary investigations that are themselves harmful, through unnecessary radiation and the consequences of these investigations themselves producing false‐positive results. While the lack of evidence to support or refute the use of "red flags" is recognised, a more pragmatic solution is to consider the possibility of spinal malignancy (in light of its low prevalence in primary care) when a combination of recommended "red flags" are found to be positive.

Implications for research.

There is a need for good quality diagnostic studies of clinical tests in patients with LBP. For the identification of serious spinal pathologies, these studies should evaluate the performance of combinations of "red flags" in order to derive a diagnostic algorithm based on patient history and physical examination. The performance of such diagnostic models can be tested against appropriate reference standards in a consecutive series of patients with LBP. Appropriate standards for reporting of primary diagnostic studies should be followed and clear definitions should be given for positive results of both index tests and reference standard outcome. Due to the low prevalence of malignancy in primary care patients with LBP, further studies will need to be very large in order to have sufficient statistical power to produce precise estimates of the sensitivity and specificity of "red flags". Potentially, the quality of the evidence around diagnostic tests for such a rare condition could be improved through the use of well designed case‐control studies or mathematical modelling to identify appropriate diagnostic strategies.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Danielle van der Windt for her assistance in the development of the protocol.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

1. Index test: clinical red flags

"Medical History Taking"[mesh] OR history[tw] OR "red flag"[tw] OR "red flags" OR Physical examination[mesh] OR "physical examination"[tw] OR "function test"[tw] OR "physical test"[tw] OR ((clinical[tw] OR clinically[tw]) AND (diagnosis[tw] OR sign[tw] OR signs[tw] OR significance[tw] OR symptom*[tw] OR parameter*[tw] OR assessment[tw] OR finding*[tw] OR evaluat*[tw] OR indication*[tw] OR examination*[tw]) OR (ra[sh] OR ri[sh]))

2. Population: low‐back pain and anatomical location

(back pain[mesh] OR sciatica[mesh] OR "back ache"[tw] OR backache[tw] OR "back pain"[tw] OR dorsalgia[tw] OR lumbago[tw] OR sciatica[tw] OR Pain[mesh] OR pain[tw] OR ache*[tw] OR aching[tw] OR complaint*[tw] OR dysfunction*[tw] OR disabil*[tw] OR neuralgia[tw]) AND (Back[mesh] OR spine[mesh] OR back[ti] OR lowback[tw] OR lumbar[tw] OR lumba*[tw] OR lumbo*[tw] OR sciatic*[tw] OR ischia*[tw] OR sacroilia*[tw] OR spine[tw] OR spinal[tw] OR radicular[tw] OR "nerve root"[tw] OR "nerve roots"[tw] OR disk[tw] OR disc[tw] OR disks[tw] OR discs[tw] OR vertebra*[tw] OR intervertebra*[tw] OR Sacroiliac‐joint[mesh] OR Lumbar vertebrae[mesh])

3. Target condition: spinal malignancy

cancer*[tw] OR tumor*[tw] OR tumour*[tw] OR carcinoma*[tw] OR sarcoma*[tw] OR neoplasm*[tw] OR Neoplasms[mesh] OR adenocarcinoma*[tw] OR metastasis*[tw] OR polyp*[tw] OR Cancer Screening[mesh] OR malignan*[tw]

4. Exclusion criteria: children, case reports, animal studies

(exp Child [mesh] OR exp Infant [mesh]) NOT ((exp Child [mesh] OR exp Infant [mesh]) AND (exp Adult [mesh] OR Adolescent [mesh])) OR (Animals [mesh] NOT (Animals [mesh] AND Humans [mesh])) OR “case report”[ti]

Search combination

1 AND 2 AND 3 NOT 4

Appendix 2. EMBASE search strategy

1. Index test: clinical red flags

'medical history taking'/exp OR 'history'/de OR history OR 'red flag' OR 'red flags' OR 'physical examination'/exp OR 'physical examination' OR 'function test'/de OR 'function test' OR 'physical test' OR (clinical OR clinically AND ('diagnosis'/de OR sign OR signs OR significance OR symptom$ OR parameter$ OR assessment OR finding$ OR evaluat$ OR indication$ OR examination$)) OR 'radiography'/exp OR 'radionuclide'/exp AND [humans]/lim

2. Population: low‐back pain and anatomical location

back AND 'pain'/exp OR 'back pain' OR 'low back' AND 'pain'/exp OR 'low back pain' OR 'sciatica'/exp OR sciatica OR backache OR coccyx OR coccydynia OR dorsalgia OR 'lumbar pain' OR spondylosis OR lumbago AND [humans]/lim

3. Target condition: spinal malignancy

'cancer$' OR 'tumor$' OR 'tumour$' OR 'carcinoma$' OR 'sarcoma$' OR 'neoplasm$' OR 'neoplasms'/exp OR 'adenocarcinoma$' OR 'metastasis$' OR 'polyp$' OR 'cancer screening'/exp OR 'malignan$'

4. Exclusion criteria: children, case reports, animal studies

'case report' AND [humans]/lim

Search combination

1 AND 2 AND 3 NOT 4

Appendix 3. CINAHL search strategy

1 Index test: clinical red flags

MH "Patient History Taking" or TX history or TX "red flag" or MM “Physical examination” or TX "physical examination" or TX "physical test" or TX clinical* or MH "Diagnostic Tests, Routine" and (TX diagnosis or TX sign or TX signs or TX significance or TX symptom* or TX parameter* or TX assessment or TX finding* or TX evaluat* or TX indication* or TX examination*)

2. Population: low‐back pain and anatomical location

MH "Back Pain" or MH "Low back pain" or TX "back pain" or TX "low back pain" or MM Sciatica or TX sciatica or TX Backache or TX Coccyx or TX Coccydynia or TX Dorsalgia or TX lumbar pain or TX spondylosis or TX lumbago

3. Target condition: malignancy

MH "Neoplams" or MH "Cancer screening" or TX cancer* or TX tumor* or TX tumour* or TX tumour* or TX carcinoma* or TX sarcoma* or TX adenocarcinoma* or TX metastasis* or TX polyp* or TX malignan*

Search combination

1 and 2 and 3

Appendix 4. Guide to scoring QUADAS Quality Assessment items

| Item and Guide to classification |

|

1. Was the spectrum of patients representative of the patients who will receive the test in practice? Is it a selective sample of patients? Classify as ‘yes’ if a consecutive series of patients or a random sample has been selected. Information should be given about setting, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and preferably number of patients eligible and excluded. If a mixed population of primary and secondary care patients is used: the number of participants from each setting is presented. Classify as ‘no’ if healthy controls are used. Also, score ‘no’ if non‐response is high and selective, or there is clear evidence of selective sampling. Also, score ‘no’ if a population is selected that is otherwise unsuitable, for example, >10% patients are known to have other specific causes of LBP (severe OA, fracture, etc). Classify as ‘unclear’ if insufficient information is given on the setting, selection criteria, or selection procedure to make a judgment. |

|

2. Is the reference standard likely to classify the target condition correctly? Classify as ‘yes’ if one of: 1) plain radiography; 2) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); 3) computed tomography (CT); or 4) other imaging tests such as bone scan; is used as a reference standard. Classify as ‘no’ if you seriously question the methods used, if consensus among observers, or an unknown combination of the clinical assessment ("clinical judgment") is used as reference standard. Classify as ‘unclear’ if insufficient information is given on the reference standard to make an adequate assessment. |

|

3. Is the time period between the reference standard and the index test short enough to be reasonably sure that the target condition did not change between the two tests? Classify as ‘yes’ if the time period between clinical assessment and the reference standard is one week or less. Classify as ‘no’ if the time period between clinical assessment and the reference standard is longer than one week. Classify as ‘unclear’ if there is insufficient information on the time period between index tests and reference standard. |

|

4. Did the whole sample or a random selection of the sample receive verification using a reference standard of diagnosis? Classify as ‘yes’ if it is clear that all patients who received the index test went on to receive a reference standard, even if the reference standard is not the same for all patients. Classify as ‘no’ if not all patients who received the index test received verification by a reference standard. Classify as ‘unclear’ if insufficient information is provided to assess this item. |

|

5. Did patients receive the same reference standard regardless of the index test result? Classify as ‘yes’ if it is clear that all patients receiving the index test are subjected to the same reference standard. Classify as ‘no’ if different reference standards are used. Classify as ‘unclear’ if insufficient information is provided to assess this item. |

|

6. Was the reference standard independent of the index test (i.e. the index test did not form part of the reference standard)? Classify as ‘yes’ if the index test is not part of the reference standard. Classify as ‘no’ if the index test is clearly part of the reference standard. Classify as ‘unclear’ if insufficient information is provided to assess this item. |

| 7. Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Classify as ‘yes’ if the results of the reference standard are interpreted blind to the results of the index tests. Also, classify as ‘yes’ if the sequence of testing is always the same (i.e. the reference standard is always performed first, followed by the index test) and consequently, the reference standard is interpreted blind of the index test. Classify as ‘no’ if the assessor is aware of the results of the index test. Classify as ‘unclear’ if insufficient information is given on independent or blind assessment of the index test. |

|

8. Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Classify as ‘yes’ if the results of the index test are interpreted blind to the results of the reference test. Also, classify as ‘yes’ if the sequence of testing is always the same (i.e. the index test is always performed first, followed by the reference standard), and consequently, the index test is interpreted blind of the reference standard. Classify as ‘no’ if the assessor is aware of the results of the reference standard. Classify as ‘unclear’ if insufficient information is given on independent or blind assessment of the reference standard. |

|

9. Were the same clinical data available when the index test results were interpreted as would be available when the test is used in practice? Classify as ‘yes’ if clinical data (i.e. patient history, other physical tests) would normally be available when the test results are interpreted and similar data are available in the study. Also, classify as ‘yes’ if clinical data would normally not be available when the test results are interpreted and these data are also not available in the study. Classify as ‘no’ if this is not the case, e.g. if other test results are available that cannot be regarded as part of routine care. Classify as ‘unclear’ if the paper does not explain which clinical information was available at the time of assessment. |

|

10. Were uninterpretable / intermediate test results reported? Classify as ‘yes’ if all test results are reported for all patients, including uninterpretable, indeterminate, or intermediate results. Also, classify as ‘yes’ if the authors do not report any uninterpretable, indeterminate, or intermediate results AND the results are reported for all patients who were described as having been entered into the study. Classify as ‘no’ if you think that such results occurred, but have not been reported. Classify as ‘unclear’ if it is unclear whether all results have been reported. |

|

11. Were withdrawals from the study explained? Classify as ‘yes’ if it is clear what happens to all patients who entered the study (all patients are accounted for, preferably in a flow chart). Also, classify as ‘yes’ if the authors do not report any withdrawals AND if the results are available for all patients who were reported to have been entered in the study. Classify as ‘no’ if it is clear that not all patients who were entered completed the study (received both index test and reference standard), and not all patients are accounted for. Classify as ‘unclear’ when the paper does not clearly describe whether or not all patients completed all tests, and are included in the analysis. |

Data

Presented below are all the data for all of the tests entered into the review.

Tests. Data tables by test.

| Test | No. of studies | No. of participants |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Age > 50 | 5 | 4473 |

| 2 Age > 70 | 1 | 1172 |

| 3 Constant progressive pain | 1 | 1172 |

| 4 Duration of this episode > 1 month | 1 | 1902 |

| 5 Gradual onset before age 40 | 1 | 1172 |

| 6 Is the low‐back pain familiar? | 1 | 1190 |

| 7 Insidious onset | 2 | 3120 |

| 8 Not improved after 1 month | 2 | 2596 |

| 9 Previous history of cancer | 3 | 3583 |

| 10 Recent back injury | 1 | 1965 |

| 11 Severe pain | 1 | 1882 |

| 12 Systemically unwell | 1 | 1172 |

| 13 Thoracic pain | 1 | 1932 |

| 14 Tried bedrest with no relief | 2 | 2115 |

| 15 Unexplained weight loss | 2 | 3123 |

| 16 Altered sensation from the trunk down | 1 | 1172 |

| 17 Fever (temp > 100oF) | 1 | 1959 |

| 18 Muscle spasm | 1 | 1871 |

| 19 Neurological symptoms | 2 | 2816 |

| 20 Spine tenderness | 1 | 1863 |

1. Test.

Age > 50.

2. Test.

Age > 70.

3. Test.

Constant progressive pain.

4. Test.

Duration of this episode > 1 month.

5. Test.

Gradual onset before age 40.

6. Test.

Is the low‐back pain familiar?.

7. Test.

Insidious onset.

8. Test.

Not improved after 1 month.

9. Test.

Previous history of cancer.

10. Test.

Recent back injury.

11. Test.

Severe pain.

12. Test.

Systemically unwell.

13. Test.

Thoracic pain.

14. Test.

Tried bedrest with no relief.

15. Test.

Unexplained weight loss.

16. Test.

Altered sensation from the trunk down.

17. Test.

Fever (temp > 100oF).

18. Test.

Muscle spasm.

19. Test.

Neurological symptoms.

20. Test.

Spine tenderness.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Deyo 1986.

| Clinical features and settings | Patients seeking treatment at a walk‐in clinic (USA), with back pain as their primary complaint. 72% with LBP duration less than 1 month; first medical care for back pain in 53%. | |

| Participants | The history and physical examination was completed for 1108 patients. 487 were excluded for the following reasons: 187 had maximal pain above T12; 79 had evidence of urinary tract disease; 131 were women less than 45 years old who were not practising contraception and had not had a menstrual period within 10 days; 130 were participants in a clinical trial which constrained x‐ray ordering; and 37 had unlocated x‐ray or laboratory results (some patients had more than one exclusion criterion). The study sample was of 621 patients with mean age of 40.5 years (range 15‐86 years). | |

| Study design | Prospective longitudinal study examining actual x‐ray utilisation, and assessing the potential effects of applying selective criteria for x‐ray utilisation. | |

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | The hospital tumour registry and discharge records were used to identify patients found to have a malignancy during the six months after the initial visit, and the medical records of all febrile patients were reviewed after six months. Four cases (0.64%) of malignancy were identified. | |

| Index and comparator tests | History and physical examination data (65 items) were recorded by physicians on a standard coding form. Data available only on two index tests: patient aged > 50 years; and not improved after 1 month. | |

| Follow‐up | Missing or uninterpretable data not reported. | |

| Notes | ||

| Table of Methodological Quality | ||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Description |

| Representative spectrum? All tests | Yes | Consecutive series of patients with low‐back pain |

| Acceptable reference standard? All tests | Yes | X‐ray ‐ anteroposterior and lateral lumbar views |

| Acceptable delay between tests? All tests | Yes | 84% of reference test obtained on the day of the index test or within 6 days thereafter |

| Partial verification avoided? All tests | No | Only 311 of 621 received the x‐ray reference test |

| Differential verification avoided? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Incorporation avoided? All tests | Yes | X‐ray not part of index tests |

| Reference standard results blinded? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Index test results blinded? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Relevant clinical information? All tests | Yes | Index tests available in usual care |

| Uninterpretable results reported? All tests | No | Not reported |

| Withdrawals explained? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

Deyo 1988.

| Clinical features and settings | Patients seeking treatment at a walk‐in clinic (USA), with back pain as chief complaint. 54% were seeking medical care for back pain for the first time, and 76% had pain for less than three months. | |

| Participants | 1975 patients with a mean age of 39.5 years (range 15‐86 years, SD = 15.4). | |

| Study design | Prospective longitudinal study, consecutive participants underwent history and physical examination (index tests) at initial consultation. | |

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | To identify patients who proved to have an underlying malignancy, each name was searched for in the institutional tumour registry at least six months after the index visit. 38 participants were found in the tumour registry, of which 13 (0.66%) were deemed to be the underlying cause of LBP. | |

| Index and comparator tests | History and physical examination data (65 items) were recorded by physicians on a standard coding form. Data available on 14 index tests: age > 50 years; unexplained weight loss (more than 10 pounds in six months); previous history of cancer; sought medical care in the past month, not improving; tried bed rest but no relief; insidious onset; duration of this episode > 1 month; recent back injury (included lifting, fall, blow); thoracic pain (vs. lumbar); appeared to be in severe pain; muscle spasm; spine tenderness; neuromotor deficit; fever (temp ≥ I00°F). Discussion reports that a combination of age greater than 50 years, history of cancer, unexplained weight loss, or failure to improve with conservative therapy had a sensitivity of 100%. No further data on this combination were provided. |

|

| Follow‐up | Missing or uninterpretable data not reported. | |

| Notes | ||

| Table of Methodological Quality | ||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Description |

| Representative spectrum? All tests | Yes | Patients with LBP seeking treatment at a walk‐in clinic |

| Acceptable reference standard? All tests | Yes | Follow‐up in tumour registry for 6 months |

| Acceptable delay between tests? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Partial verification avoided? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Differential verification avoided? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Incorporation avoided? All tests | Yes | Index tests not part of follow‐up |

| Reference standard results blinded? All tests | Yes | Index test performed prior to reference standard |

| Index test results blinded? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Relevant clinical information? All tests | Yes | Index tests are part of clinical examination |

| Uninterpretable results reported? All tests | No | Not reported |

| Withdrawals explained? All tests | No | Not reported |

Donner‐Banzhoff 2006.

| Clinical features and settings | Patients with LBP, irrespective of duration or previous history, presenting to primary care (Germany). Exclusion criteria were insufficient language skills, pregnancy and isolated thoracic pain. | |

| Participants | 1353 patients with a mean age of 49 years (range 20–91 years). | |

| Study design | Consecutive patients recruited into a cluster‐randomised controlled trial evaluating strategies to improve the quality of care. 12 months after entering study, data were collected by telephone follow‐up. | |

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | At the 12‐month follow‐up, highly sensitive filter questions (not reported) related to relevant serious conditions that might have caused LBP at the time of recruitment were asked. If at least one of these was answered in the affirmative, diagnosis and/or complaints were recorded and a following telephone interview performed to gather details on healthcare utilisation (e.g. hospital treatments, medication, present complaints and impairments). A reference committee consisting of two experienced GPs and a senior medical student reviewed the evidence collected for each patient. Based on this information, patients were judged to either have a relevant condition or not (delayed‐type reference standard). One case (0.07%) of spinal malignancy was identified. | |

| Index and comparator tests | A written questionnaire at baseline included the question: "Is the low‐back pain familiar to you?" which could be answered "yes" or "no". | |

| Follow‐up | Of 1378 patients recruited, 1353 answered the question with regard to the familiarity of their LBP (index test). Of these patients, 1190 were available for follow‐up at 1 year (reference standard). | |

| Notes | ||

| Table of Methodological Quality | ||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Description |

| Representative spectrum? All tests | Yes | Patients with LBP presenting to primary care |

| Acceptable reference standard? All tests | Yes | Long‐term follow‐up |

| Acceptable delay between tests? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Partial verification avoided? All tests | Yes | All patients followed up |

| Differential verification avoided? All tests | Yes | All patients followed up |

| Incorporation avoided? All tests | Yes | Index test not part of follow‐up questionnaire |

| Reference standard results blinded? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Index test results blinded? All tests | Yes | Index test performed prior to reference standard |

| Relevant clinical information? All tests | Yes | Index test as part of clinical examination |

| Uninterpretable results reported? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Withdrawals explained? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

Frazier 1989.

| Clinical features and settings | Patients presenting with acute LBP to medical walk‐in clinics (USA). If the initial history indicated that the patient's back pain (1) had a duration of more than 60 days, (2) was above the 12th thoracic vertebra, or (3) was attributable to conditions such as urinary tract infection or pelvic inflammatory disease, the patient was excluded from the study. | |

| Participants | Clinic logs revealed 1037 patients who presented with back pain during the study period. Medical records were reviewed for 863 (83%) of these patients. Of these, 392 were excluded. The study sample included 471 patients with acute lumbosacral back pain and a mean age of 40.8 years (range 15‐90 years). | |

| Study design | Retrospective review of medical records for patients with presenting complaints of "back pain" or "sore back". Records were reviewed at least six months after the patient initially presented. | |

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Physician notes from visits up to six months after the initial visit were the source of follow‐up information. These notes were examined to determine if the initial back pain episode was ultimately attributed to vertebral cancer, osteomyelitis, vertebral fracture, or herniated disk. One case (0.21%) of spinal malignancy was identified. | |

| Index and comparator tests | Data were collected for 18 patient characteristics; available index test data only for age > 50 years. | |

| Follow‐up | Missing or uninterpretable data not reported | |

| Notes | ||

| Table of Methodological Quality | ||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Description |

| Representative spectrum? All tests | Yes | Patients presenting with low‐back pain to medical walk‐in clinics |

| Acceptable reference standard? All tests | Yes | Lumbar spine roentgenograms (x‐ray) and follow‐up of physician notes for 6 months |

| Acceptable delay between tests? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Partial verification avoided? All tests | No | Not reported if all patients received reference standard |

| Differential verification avoided? All tests | No | Not reported if all patients received follow‐up as well as x‐ray |

| Incorporation avoided? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Reference standard results blinded? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Index test results blinded? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Relevant clinical information? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Uninterpretable results reported? All tests | No | Not reported |

| Withdrawals explained? All tests | No | Not reported |

Henschke 2009.

| Clinical features and settings | Patients aged over 14 years with acute LBP who presented to a primary care provider (Australia). Participants were excluded if serious pathology had been diagnosed prior to the consultation, and the serious pathology was considered to be the cause of the current episode of low‐back pain. | |

| Participants | 1172 patients with a mean age of 44 (SD 15.1) and acute LBP who were presenting for the first consultation for that episode. | |

| Study design | Consecutive, prospective cohort study with 12 months follow‐up. | |

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | The reference standard consisted of telephone follow‐up 6 weeks, 3 months, and 12 months after the initial consultation. At each follow‐up contact, participants were asked the following question: "Low back pain is occasionally the result of a fracture, infection, arthritis, or cancer. Has a health care provider said that your back pain is caused by one of these rare diseases?". All patients with potentially serious pathology were subsequently examined by a study rheumatologist. | |

| Index and comparator tests | "Red flag" questions: age > 50; gradual onset before age 40; age > 70; unexplained weight loss; previous history of cancer; tried bed rest but no relief; insidious onset; systemically unwell; constant progressive pain; altered sensation from the trunk down. No cases of spinal malignancy were identified. | |

| Follow‐up | All patients (n = 1172) were followed up 12 months after presenting to primary care. A random sample (n = 218) was reviewed by a rheumatologist after 12 month follow‐up to confirm reference standard. | |

| Notes | ||

| Table of Methodological Quality | ||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Description |

| Representative spectrum? All tests | Yes | Consecutive sample of low‐back pain patients with clear inclusion criteria |

| Acceptable reference standard? All tests | Yes | Long‐term follow‐up of all patients |

| Acceptable delay between tests? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Partial verification avoided? All tests | Yes | All patients had long‐term follow‐up |

| Differential verification avoided? All tests | Yes | All patients received the reference standard |

| Incorporation avoided? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Reference standard results blinded? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Index test results blinded? All tests | Yes | Index test completed prior to reference standard |

| Relevant clinical information? All tests | Yes | Index tests available in usual care |

| Uninterpretable results reported? All tests | Yes | All results reported |

| Withdrawals explained? All tests | Yes | All participants completed follow‐up |

Jacobson 1997.

| Clinical features and settings | Patients without prior history of malignancy who underwent bone scans to investigate musculoskeletal complaints. Secondary referrals for bone scintigraphy (USA). | |

| Participants | 491 patients with a mean age of 56 years (range 21‐94 years). 257 (52%) had complaints of middle to lower back pain, with 99 patients younger than 50 years and 158 patients aged 50 years or older. | |

| Study design | Retrospective review of consecutive bone scintigraphy scans. | |

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Scan results were classified into 1 of the following categories: (A) no findings suggestive of malignancy; (B) equivocal; or (C) probable metastatic disease. Scans with reports classified in categories B and C were subsequently reviewed unblinded by the author to verify the original interpretations. Available radiological, histopathologic, and clinical records for all patients were reviewed to identify diagnoses of malignancy established subsequent to the scan results. 18 cases (7%) of spinal malignancy were identified. | |

| Index and comparator tests | Data only available on one index test: age > 50 years. | |

| Follow‐up | Missing or uninterpretable data not reported | |

| Notes | ||

| Table of Methodological Quality | ||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Description |

| Representative spectrum? All tests | No | Patients referred for bone scan with complaints of musculoskeletal or bone and joint pain |

| Acceptable reference standard? All tests | Yes | Bone scans were performed 2.5 to 3 hours following intravenous administration of 833 to 1018MBq of technetium Tc99m methylene diphosphonate. Images were acquired using large field‐of‐view gamma cameras and low‐energy, high‐resolution collimators. |

| Acceptable delay between tests? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Partial verification avoided? All tests | Yes | All patients received reference standard |

| Differential verification avoided? All tests | Yes | All patients received same reference standard |

| Incorporation avoided? All tests | Yes | Index tests not part of reference standard |

| Reference standard results blinded? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Index test results blinded? All tests | Yes | Index tests performed prior to reference standard |

| Relevant clinical information? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Uninterpretable results reported? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Withdrawals explained? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

Khoo 2003.

| Clinical features and settings | General practice referrals for lumbar spine radiographs were enrolled without exclusion (UK). Clinical indications for referral included low‐back pain; hip, leg, sacroiliac pain or trauma; neurological symptoms; possible malignancy; and inflammatory condition. | |

| Participants | 1030 patients with mean age of 53 years (range 10–100 years). | |

| Study design | Prospective study of consecutive referrals for lumbar spine radiograph. | |

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Two‐view lumbar spine radiographs were taken as standard ‐ an anteroposterior (AP) and a lateral view. Radiological analysis was shared between six consultant radiologists using a standard format. Two cases (0.19%) of spinal malignancy were identified. | |

| Index and comparator tests | Data only available on one index test: neurological symptoms. | |

| Follow‐up | Missing or uninterpretable data not reported. | |

| Notes | Author was contacted by review team and provided complete data on index test results. | |

| Table of Methodological Quality | ||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Description |

| Representative spectrum? All tests | Yes | Consecutive general practice referrals for lumbar spine radiograph |

| Acceptable reference standard? All tests | Yes | Two‐view lumbar spine radiographs were taken as standard ‐ an anteroposterior (AP) and a lateral view. |

| Acceptable delay between tests? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Partial verification avoided? All tests | Yes | All patients received radiographs |

| Differential verification avoided? All tests | Yes | All patients received same reference standard |

| Incorporation avoided? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Reference standard results blinded? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Index test results blinded? All tests | Yes | Performed prior to reference standard |

| Relevant clinical information? All tests | Unclear | Unclear from text |

| Uninterpretable results reported? All tests | No | Not reported |

| Withdrawals explained? All tests | No | Not reported |

Reinus 1998.

| Clinical features and settings | All patients receiving lumbosacral spine radiographs in a level II emergency department (USA) were entered in the study. | |

| Participants | 482 patients (314 women and 168 men) with a mean age of 56 years (range 17‐98 years). | |

| Study design | Prospective study of consecutive patients receiving lumbosacral radiographs. | |

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | The lumbosacral spine examination included anteroposterior, lateral, bilateral posterior oblique, and coned‐down lateral views. All examinations were interpreted by board certified radiologists who specialised in musculoskeletal radiology. Official radiography reports were used as the source of the recorded radiographic diagnoses. Seven cases (1.45%) of spinal malignancy were identified. | |

| Index and comparator tests | Data available on indications for ordering lumbosacral spine radiographs, one index test: a previous history of cancer. | |