Abstract

Objective:

To assess whether the risk of persistent opioid use after surgery varies by payer type.

Background:

Persistent opioid use is associated with increased health care utilization and risk of opioid use disorder, opioid overdose, and mortality. Most research assessing the risk of persistent opioid use has focused on privately insured patients. Whether this risk varies by payer type is poorly understood.

Methods:

This cross-sectional analysis of the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative database examined adults aged 18 to 64 years undergoing surgical procedures across 70 hospitals between January 1, 2017 and October 31, 2019. The primary outcome was persistent opioid use, defined a priori as 1+ opioid prescription fulfillment at (1) an additional opioid prescription fulfillment after an initial postoperative fulfillment in the perioperative period or at least 1 fulfillment in the 4 to 90 days after discharge and (2) at least 1 opioid prescription fulfillment in the 91 to 180 days after discharge. The association between this outcome and payer type was evaluated using logistic regression, adjusting for patient and procedure characteristics.

Results:

Among 40,071 patients included, the mean age was 45.3 years (SD 12.3), 24,853 (62%) were female, 9430 (23.5%) were Medicaid-insured, 26,760 (66.8%) were privately insured, and 3889 (9.7%) were covered by other payer types. The rate of POU was 11.5% and 5.6% for Medicaid-insured and privately insured patients, respectively (average marginal effect for Medicaid: 2.9% (95% CI 2.3%–3.6%)).

Conclusions:

Persistent opioid use remains common among individuals undergoing surgery and higher among patients with Medicaid insurance. Strategies to optimize postoperative recovery should focus on adequate pain management for all patients and consider tailored pathways for those at risk.

Keywords: opioids, insurance, surgical patients, persistent opioid use, medicaid

Of the ~100,000 drug overdose-related deaths in 2021, ~75% involved opioids and 15% involved prescription opioids.1 Surgery continues to be one of the most common reasons for opioid prescribing. For both opioid-naive and opioid-exposed patients, exposure to opioids after surgery is associated with an increased risk of persistent opioid use, defined as the continued use of opioids beyond the time during which acute pain typically resolves.2–7 Persistent opioid use is widely recognized as a major source of postoperative morbidity and has been associated with increased rates of complications, development of opioid use disorder, intravenous drug use, and overdose. In addition, persistent opioid use has been associated with significantly higher health care utilization and costs in the settings of postoperative care and readmissions.8–12

Previous research has identified several risk factors for persistent opioid use, such as mental health disorders and substance use disorders.13,14 However, whether payer type is a risk factor for persistent opioid use is poorly understood, as most research assessing the risk of this complication has focused on assessing patients within specific payer populations, particularly the privately insured.15 A previous study found that the risk of persistent opioid use associated with opioid exposure after dental procedures was significantly higher among Medicaid-insured nonelderly adults compared with their privately insured counterparts, but whether these findings generalize to surgical patients is unknown.16 The opioid epidemic disproportionately affects Medicaid beneficiaries, who are prescribed pain relievers at higher rates than those with other sources of insurance.17 Understanding the variation in risk of persistent opioid use by payer type is crucial. For example, if this risk is higher among Medicaid-insured patients compared with privately insured patients undergoing surgery, this would suggest that the whole-population risk of this complication is greater than previously appreciated. Furthermore, greater attention can then be placed on the analysis of payer group outcomes, the necessity of potential clinical policy changes, and an additional understanding on the impacts of social determinants of health. In contrast, if it is lower, this would suggest that the risk of this complication has been overstated.

Using an all-payer database from Michigan patients undergoing surgery across Michigan linked to the state’s prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) database, the present study evaluated the association between payer type and persistent opioid use among adults undergoing a variety of common surgical procedures. We hypothesized that Medicaid patients would have higher rates of persistent opioid use compared with the privately insured, regardless of whether they were opioid-naive versus opioid-exposed before surgery.

METHODS

This study of de-identified data was exempted from human subjects review by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan Medical School; informed consent was not required. This manuscript confirms to the Strength in Reporting Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines.13

Data Sources

Data were obtained from the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative (MSQC). MSQC is a statewide quality improvement collaborative that maintains a clinical registry of adult patients undergoing surgery in 70 hospitals across Michigan. Data includes patient demographics, perioperative processes, and 30-day outcomes.14,15 Participating hospitals receive funding from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan to fund trained data abstractors that use standardized methods to obtain data for patients. Cases are audited regularly for accuracy and collected using a sampling algorithm designed to minimize selection bias.

We linked patients in MSQC with the Michigan Automatic Prescription System (MAPS), the state’s PDMP database. MAPS tracks all controlled substance fills in the state of Michigan. The MAPS-MSQC linkage followed a state-approved process and was performed by an independent third party, which removed all patient identifiers from the final data set. (S7 Supplementary Methods, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/SLA/E681) The linkage allowed us to identify all controlled substance prescription fills after surgery in Michigan, regardless of whether the prescription was paid for by insurance or cash and regardless of whether the prescriber worked at the hospital in which the survey was performed versus in another facility. This is a substantial advantage over insurance claims databases, which only capture prescriptions paid for by insurance, as well as traditional hospital-based registry data, which usually only capture prescriptions from prescribers at the hospital.

Patient Population

This study included adults aged 18 to 64 undergoing elective, emergent, or urgent inpatient or outpatient procedures between January 1, 2017 and October 31, 2019. Procedures included general surgery, vascular, and gynecologic procedures. We are limited to patients with the following payer types: private, Medicare (eg, nonelderly adult patients with end-stage renal disease), Medicaid, dual eligible, and uninsured. Patients were excluded if they had a reoperation within 30 days, died within 30 days of surgery, were not discharged home, or had a length of stay longer than 30 days. In addition, patients who had uncommon procedures, patients who had more than 1 match in the PDMP database, patients with an address outside Michigan, and patients with missing demographic, clinical, or opioid prescription data were excluded. We did not include patients aged 65 and older, almost all of whom were covered by Medicare, as our goal was to compare the risk of persistent opioid use by payer type.

Outcome and Explanatory Variables

The primary outcome, persistent opioid use, was defined a priori to data extraction as (1) an additional opioid prescription fulfillment after an initial postoperative fulfillment in the perioperative period or at least 1 fulfillment in the 4 to 90 days after discharge and (2) at least 1 opioid prescription fulfillment in the 91 to 180 days after discharge.18 The primary independent variable was payer type. Because almost 90% of patients were covered either by Medicaid or private insurance, the comparison between these 2 payer types was of primary interest. Covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity, tobacco use in the year before surgery, cancer status, obesity (body mass index >=30), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification, surgical procedure (Major, Major/MIS, Minor, Figure S1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/SLA/E681), elective versus emergent status, and inpatient versus outpatient status, readmission within 30 days, emergency department visits within 30 days, postoperative complications within 30 days, and neighborhood characteristics (continuous scores on disadvantage, affluence, and ethnic immigrant concentration) obtained from the National Neighborhood Data Archive (NaNDA) using patient zip code. Covariates also included preoperative opioid use in the opioid-exposed cohort. Patients with at least 1 opioid prescription in the PDMP data in the 365 days to 31 days before surgery were defined as opioid-exposed and those without opioid prescriptions during this period were defined as opioid-naive. In the subgroup analysis limited to opioid-exposed patients, we included a categorical variable for 1 of 3 opioid use patterns based on opioid prescription fills during the year before surgery: minimal (≤30 days of opioid therapy), intermittent (31–270 d of opioid therapy), and chronic (271 d or more of opioid therapy).19

Analysis

We assessed differences in characteristics of the study population by payer type using 1-way ANOVA and χ2 tests. To evaluate the association between payer type and persistent opioid use, we fitted a multilevel logistic regression model with a hospital random intercept, controlling for covariates. (Figure S2, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/SLA/E681) The reference category for the payer type was the privately insured. We repeated this analysis among opioid-naive and opioid-exposed patients. The model for the opioid-exposed patients included the categorical variable for preoperative opioid use patterns.

To facilitate the interpretation of coefficients as absolute percentage-point changes in probability rather than adjusted odds ratios, we calculated average marginal effects. For categorical variables such as payer type, average marginal effects represent the additional change in probability of the outcome that would occur if all patients had a particular payer type (eg, Medicaid insurance) relative to the reference category (ie, private insurance), holding all other covariates at their observed values.

In a sensitivity analysis, we excluded patients who did not experience any hospital readmissions or ED visits in the 30 days after surgery. (Figure S3, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/SLA/E681) We conducted this analysis because the occurrence of these utilization events might signify those patients had indications for opioids unrelated to the initial surgery (eg, a motor vehicle accident). All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute) and Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp). Two-sided P values <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Among 68,264 patients aged 18 to 64 years undergoing surgery between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2019 in the MSQC database, 28,193 (41.3%) were excluded (Fig. 1). Of the remaining 40,071 patients, 24,853 (62.0% were female) and the mean age was 45.3 years (SD 12.3). Among the 40,071 patients, 26,760 (66.8%) were privately insured, 9430 (23.5%) were Medicaid-insured, 2292 (5.7%) were Medicare-insured, 700 (1.7%) were dual eligible, and 889 (2.2%) were uninsured. In addition, 28,573 (71.3%) patients were opioid-naive. Table 1 displays other characteristics of the sample.

FIGURE 1.

STROBE figure showing inclusion and exclusion criteria for studied patients.

TABLE 1.

Cohort Demographics (First column = all patients, then by payer type)

| Total (Overall cohort) | Private | Medicaid | Medicare | Dual eligible | Uninsured | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=40,071 | N=26,760 | N=9430 | N=2292 | N=700 | N=889 | P | |

| Age, in yr, mean (SD) | 45.3 (12.3) | 46.1 (12.0) | 41.4 (12.5) | 53.4 (9.4) | 48.9 (10.0) | 40.5 (12.9) | <0.001 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||||||

| Female | 24,853 (62.0) | 16,202 (60.5) | 6436 (68.3) | 1316 (57.4) | 466 (66.6) | 433 (48.7) | <0.001 |

| Male | 15,218 (38.0) | 10,558 (39.5) | 2994 (31.7) | 976 (42.6) | 234 (33.4) | 456 (51.3) | |

| Race, n (%) | |||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 33,499 (83.6) | 23,596 (88.2) | 6843 (72.6) | 1922 (83.9) | 486 (69.4) | 652 (73.3) | <0.001 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 4571 (11.4) | 2024 (7.6) | 1947 (20.6) | 304 (13.3) | 184 (26.3) | 112 (12.6) | |

| Hispanic | 1452 (3.6) | 752 (2.8) | 518 (5.5) | 52 (2.3) | 23 (3.3) | 107 (12.0) | |

| Other | 549 (1.4) | 388 (1.4) | 122 (1.3) | 14 (0.6) | 7 (1.0) | 18 (2.0) | |

| Tobacco use | 10,567 (26.4) | 5004 (18.7) | 4135 (43.8) | 823 (35.9) | 308 (44.0) | 297 (33.4) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 1863 (4.6) | 1304 (4.9) | 360 (3.8) | 132 (5.8) | 38 (5.4) | 29 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 21,269 (53.1) | 13,997 (52.3) | 5179 (54.9) | 1273 (55.5) | 402 (57.4) | 418 (47.0) | <0.001 |

| ASA class, n (%) | |||||||

| ASA class 1 | 4321 (10.8) | 3419 (12.8) | 702 (7.4) | 26 (1.1) | 10 (1.4) | 164 (18.4) | <0.001 |

| ASA class 2–3 | 35,272 (88.0) | 23,163 (86.6) | 8596 (91.2) | 2148 (93.7) | 649 (92.7) | 716 (80.5) | |

| ASA class 4–5 | 478 (1.2) | 178 (0.7) | 132 (1.4) | 118 (5.1) | 41 (5.9) | 9 (1.0) | |

| Surgical priority, n (%) | |||||||

| Elective | 29,580 (73.8) | 20,323 (75.9) | 6693 (71.0) | 1755 (76.6) | 511 (73.0) | 298 (33.5) | <0.001 |

| Emergent/Urgent | 10,491 (26.2) | 6437 (24.1) | 2737 (29.0) | 537 (23.4) | 189 (27.0) | 591 (66.5) | |

| Surgery setting, n (%) | |||||||

| Outpatient | 18,920 (47.2) | 13,291 (49.7) | 4078 (43.2) | 993 (43.3) | 271 (38.7) | 287 (32.3) | <0.001 |

| Inpatient | 21,151 (52.8) | 13,469 (50.3) | 5352 (56.8) | 1299 (56.7) | 429 (61.3) | 602 (67.7) | |

| Surgical procedure, n (%) | |||||||

| Major | 6658 (16.6) | 4283 (16.0) | 1659 (17.6) | 464 (20.2) | 140 (20.0) | 112 (12.6) | <0.001 |

| Major MIS | 12,254 (30.6) | 8700 (32.5) | 2613 (27.7) | 622 (27.1) | 195 (27.9) | 124 (13.9) | |

| Minor | 21,159 (52.8) | 13,777 (51.5) | 5158 (54.7) | 1206 (52.6) | 365 (52.1) | 653 (73.5) | |

| Readmission | 1165 (2.9) | 605 (2.3) | 369 (3.9) | 113 (4.9) | 51 (7.3) | 27 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| ER visit | 3420 (8.5) | 1679 (6.3) | 1314 (13.9) | 244 (10.6) | 113 (16.1) | 70 (7.9) | <0.001 |

| Complications | 1199 (3.0) | 704 (2.6) | 352 (3.7) | 81 (3.5) | 38 (5.4) | 24 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| Neighborhood SES characteristics | |||||||

| Neighborhood disadvantage, mean (SD) | 0.12 (0.07) | 0.10 (0.06) | 0.15 (0.08) | 0.13 (0.07) | 0.16 (0.08) | 0.13 (0.07) | <0.001 |

| Neighborhood affluence, mean (SD) | 0.33 (0.13) | 0.35 (0.13) | 0.27 (0.11) | 0.30 (0.12) | 0.27 (0.10) | 0.30 (0.11) | <0.001 |

| Ethnic immigrant concentration, mean (SD) | 0.05 (0.05) | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.05 (0.06) | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.05 (0.05) | 0.06 (0.07) | <0.001 |

| Opioid exposure in the year prior, n (%) | |||||||

| Naive | 28,573 (71.3) | 20,149 (75.3) | 5971 (63.3) | 1293 (56.4) | 401 (57.3) | 759 (85.4) | <0.001 |

| Exposed | 11,498 (28.7) | 6611 (24.7) | 3459 (36.7) | 999 (43.6) | 299 (42.7) | 130 (14.6) | |

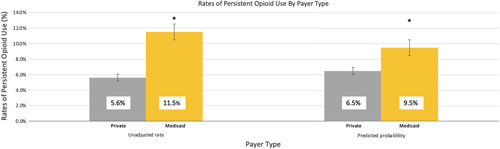

Unadjusted and predicted probabilities derived from a multilevel logistic regression model with a random intercept for hospital. Opioid-exposed patients (those with any opioid dispensing in the 365 days to 31 days before surgery) were further subclassified per preoperative dose exposure category. Minimal, Intermittent, and Chronic exposure categories were used.18

Risk of Persistent Opioid Use by Payer Type in the Overall Sample

Among the 40,071 patients, 8.3% developed persistent opioid use. Rates of persistent opioid use were highest in Medicaid (11.5%), Medicare (24.1%), and dual eligible (25.6%) populations and were lowest in privately insured patients (5.6%). After adjustment, the predicted probability of persistent opioid use for Medicaid patients was 11.5% (95% CI 10.8–12.1), compared with 6.5% (95% CI 6.1%–7.0%) in the privately insured (average marginal effect of Medicaid versus private insurance: 2.9% (95% CI: 2.3%–3.6%; Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Unadjusted rate and predicted probability of persistent opioid between patients with Medicaid and Private Health Insurance. Predicted probabilities derived from a multilevel logistic regression model with a random intercept for the hospital.

Risk of Persistent Opioid Use by Payer Type in Opioid-naive Patients

Among opioid-naive patients, the overall unadjusted rate of persistent opioid use was 2.4%. For privately insured and Medicaid-insured patients, this rate was 1.7% and 3.7%, respectively. After adjustment, the predicted probability of persistent opioid use for the privately insured was 1.9% (95% CI 1.6–2.1) and 3.1% (95% CI 2.6–3.6) for Medicaid-insured patients (average marginal effect of Medicaid versus private insurance: 1.2% (95% CI: 0.7–1.8)). (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3.

A, Rates of persistent use by payer type in opioid-naive patients. Predicted probabilities derived from a multilevel logistic regression model with a random intercept for the hospital. Opioid-naive patients were those without any opioid dispensing in the 365 days to 31 days before surgery. B, Rates of persistent use by payer type in opioid-exposed patients. Predicted probabilities derived from a multilevel logistic regression model with a random intercept for the hospital. Opioid-exposed patients were those with any opioid dispensing in the 365 days to 31 days before surgery.

The unadjusted rate of persistent opioid use was 7.7% for Medicare, 6.4% for dual eligible patients, and 1.4% for the uninsured. The average marginal effect of persistent opioid use associated with Medicare and dual eligibility was higher compared with private insurance, but the average marginal effect of persistent opioid use associated with uninsurance was lower. (Figure S5, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/SLA/E681).

Risk of Persistent Opioid Use by Payer Type in Opioid-exposed Patients

Among the opioid-exposed cohort, the overall unadjusted rate of persistent opioid use was higher in Medicaid patients (24.9%) compared with privately insured (17.4%). (Fig. 3B) When stratifying by perioperative opioid use pattern, the rate of persistent opioid use was 6.6% versus 3.9% in Medicaid and privately insured patients with minimal opioid use, 29.4% versus 26.0% in patients with intermittent opioid use, and 84.3% versus 88.6% in patients with chronic opioid use. After adjustment, the average marginal effect of Medicaid versus private insurance on the risk of persistent opioid use was 2.1% (95% CI:0.6–3.6) in the overall cohort of opioid-exposed patients, 0.9% (95% CI 0.2–1.6) in the minimal opioid use subgroup 3.6% (95% CI 1.0–6.2) in the intermittent opioid use subgroup, and 2.4% (95% CI 0.7–4.1) in the chronic opioid use subgroup. (Table 2) Similar to the opioid-naive cohort, the average marginal effect of persistent opioid use associated with Medicare and dual eligibility was higher compared with private insurance in opioid-exposed patients. The average marginal effect of persistent opioid use associated with uninsurance was also lower in this cohort. (Figure S6, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/SLA/E681).

TABLE 2.

Rate of Persistent Use in Opioid-Exposed Cohort by Payer Type

| Dose | Payer | Unadjusted rate [95% CI] | Predicted probability [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal | Private | 3.9% [3.3–4.6] | 4.9 [4.3–5.5] |

| Medicaid | 6.6% [5.4–8.0] | 5.8% [5.0–6.7] | |

| Medicare | 8.7% [5.7–12.7] | 8.7% [7.2–10.3] | |

| Dual enrollees | 19.0% [11.0–29.4] | 9.7% [7.0–12.4] | |

| Uninsured | 3.4% [0.7–9.6] | 5.1% [2.3–7.9] | |

| Overall (all payers) | 5.0% [4.5–5.6] | 5.7% [5.1–6.4] | |

| Intermittent | Private | 26.0% [24.2–27.8] | 25.4% [23.6–27.2] |

| Medicaid | 29.4% [27.1–31.8] | 29.0% [26.8–31.3] | |

| Medicare | 46.3% [41.7–50.9] | 38.5% [34.6–42.4] | |

| Dual enrollees | 43.2% [35.0–51.6] | 41.3% [34.4–48.2] | |

| Uninsured | 30.8% [17.0–47.6] | 26.3% [15.4–37.4] | |

| Overall (all payers) | 29.9% [28.5–31.2] | 28.2% [26.7–29.6] | |

| Chronic | Private | 88.6% [85.3–91.4] | 83.1% [80.5–85.8] |

| Medicaid | 84.3% [80.2–87.8] | 85.5% [83.1–88.0] | |

| Medicare | 90.1% [85.8–93.5] | 90.1% [88.0–92.2] | |

| Dual enrollees | 94.6% [86.7–98.5] | 91.1% [88.4–93.9] | |

| Uninsured | 66.7% [9.4–99.2] | 83.8% [75.8–92.8] | |

| Overall (all payers) | 87.9% [85.9–89.7] | 84.5% [82.2–86.9] |

Minimal—number of months filled =1 and preop OME <90 pills (5 mg Oxycodone pills).

Intermittent—number of months filled >=1 and number of months filled <9.

Chronic—number of filled >=9.

Unadjusted and predicted probabilities derived from a multilevel logistic regression model with a random intercept for the hospital. Opioid-exposed patients (those with any opioid dispensing in the 365 days to 31 days prior to surgery) were further subclassified per preoperative dose exposure category. Minimal, Intermittent, and Chronic exposure categories were used.18

Sensitivity Analysis

When excluding patients with hospital readmissions or emergency department visits within 30 days of surgery, results were similar to the main analysis (Figure S3, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/SLA/E681).

DISCUSSION

In this analysis of an all-payer statewide surgical registry database in Michigan, the average marginal effect of persistent opioid use was 2.9% higher in nonelderly adults with Medicaid insurance compared with their counterparts with private insurance. This association persisted regardless of preoperative opioid use pattern (opioid-naive, minimal opioid use, intermittent opioid use, and chronic opioid use). Given that the bulk of research assessing the risk of persistent opioid use after surgery has focused on variables other than payer type or were limited to the privately insured, our findings suggest the risk of persistent opioid use would be greater than previously anticipated if studies were to include all-payer types.

The principal strength of this analysis was our use of all-payer data. In contrast, the vast majority of previous studies assessing the risk of persistent opioid use after surgery have been limited to specific payer populations.4,20–24 In one of the only exceptions, members of our team calculated the risk of persistent opioid use among privately insured and Medicaid-insured patients undergoing surgery but could not compare this risk directly because the Medicaid database did not include information on state or other measures of patient geographic location.9

The etiology of the increased risk of persistent opioid use among Medicaid patients is unclear and warrants further research. One possibility is that Medicaid patients receive poorer quality of postoperative care, resulting in worse patterns of opioid prescribing.25,26 For example, Medicaid has less access to primary care and the transitions of care needed to manage pain and opioids after surgery owing to access barriers. As a result, they may simply be provided with refills rather than undergoing evaluation for poorly controlled postoperative pain.27,28 Another possibility is that Medicaid patients have a higher rate of undiagnosed risk factors for persistent opioid use than the privately insured, such as substance use disorders. Furthermore, our work focuses on prescription fulfillment and not patient-reported usage. Hence, it is possible the persistent opioid use outcome is confounded by prescription fulfillment for purposes of diversion. Regardless of the etiology, our findings have important clinical implications. While it is important to take steps to mitigate the risk of persistent opioid use in all patients, such as avoiding unnecessary opioid prescribing, ensuring that opioid prescribing is tailored to patient needs, providing counseling on opioid misuse, and encouraging safe opioid storage and disposal, our findings suggest these steps are especially important in Medicaid patients.

Although not the primary focus of this study, we found that the risk of persistent opioid use was higher among nonelderly patients covered by Medicare and patients dually covered by Medicare and Medicaid. (Figure S4, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/SLA/E681) These populations have a disproportionate burden of chronic disease, a known risk factor for persistent opioid use. Findings similarly suggest that interventions to mitigate the risk of persistent opioid use are especially important in these high-risk patient populations. In addition, the uninsured populations for the overall cohort, as well as the naive and exposed cohorts, did not have an apparent higher rate of persistent opioid use than the privately insured. Whereas uninsured patients have less access to health care, it is possible that the financial burdens of prescription medications may explain the lower rates of persistent opioid use. Further work is necessary to reproduce and elucidate these findings.

This study has many strengths, including the use of a robust, all-payer statewide surgical registry linked to the state PDMP database. In addition, unlike many prior studies of the risk of persistent opioid use after surgery, our access to data on patient zip codes allowed us to control for zip code-level measures of socioeconomic status.

However, there were limitations. First, owing to the cross-sectional nature of the analysis, we could not rule out residual confounding by unobserved factors. Second, it is unclear whether the documented variation in the risk of persistent opioid use by payer type generalizes to children or to elderly adults. Finally, owing to our reliance on data from a single state, it is unclear whether findings generalize to the United States more broadly. However, we note that our findings are consistent with a prior national analysis showing a higher risk of persistent opioid use in Medicaid-insured patients undergoing dental procedures.

CONCLUSIONS

Using a comprehensive statewide surgical registry linked to PDMP data, we found that the risk of persistent opioid use was higher when patients were covered by Medicaid compared with the privately insured. Our findings suggest that the risk of persistent opioid use after surgery is greater than previously appreciated, highlighting the urgency of avoiding unnecessary and excessive surgical opioid prescribing. Moreover, our findings suggest that interventions to prevent persistent opioid use are particularly important in Medicaid patients and that postoperative care pathways tailored to the needs of this high-risk population may be warranted.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

V.G., J.W., M.E., M.B., and C.B. receive funding from the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA042859). M.B. reports past consultations with Axial Healthcare and Alosa Health not related to this work. C.B. is a consultant for Heron Therapeutics, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Alosa Health, and the Benter Foundation, not related to this work. He also provides expert testimony. S.S. received funding from FAER to complete a medical student anesthesia research fellowship. This program is sponsored by Braun Medical Inc. and Cook Medical. K.C. received honoraria from the Benter Foundation for work outside of the current study. K.C. is supported by a career development award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant number 1K08DA048110-01). No funder or sponsor had any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. V.G. had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.annalsofsurgery.com.

Contributor Information

Sudharsan Srinivasan, Email: sudhu@med.umich.edu.

Vidhya Gunaseelan, Email: vidhyag@med.umich.edu.

Alexandra Jankulov, Email: jankulov@oakland.edu.

Kao-Ping Chua, Email: chuak@med.umich.edu.

Michael Englesbe, Email: englesbe@med.umich.edu.

Jennifer Waljee, Email: filip@med.umich.edu.

Mark Bicket, Email: mbicket@med.umich.edu.

Chad M. Brummett, Email: cbrummet@med.umich.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ahmad FB, Cisewski JA, Rossen LM, et al. Provisional drug overdose death counts. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2022. August 18, 2022. Accessed September 11. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm#citation [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bateman BT, Franklin JM, Bykov K, et al. Persistent opioid use following cesarean delivery: patterns and predictors among opioid-naïve women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:353.e1–353.e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Waljee JF, Li L, Brummett CM, et al. Iatrogenic opioid dependence in the United States: Are surgeons the gatekeepers? Ann Surg. 2017;265:728–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in US Adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:e170504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thiels CA, Anderson SS, Ubl DS, et al. Wide variation and overprescription of opioids after elective surgery. Ann Surg. 2017;266:564–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hill MV, McMahon ML, Stucke RS, et al. Wide variation and excessive dosage of opioid prescriptions for common general surgical procedures. Ann Surg. 2017;265:709–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Howard R, Fry B, Gunaseelan V, et al. Association of opioid prescribing with opioid consumption after surgery in Michigan. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:e184234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Babu KM, Brent J, Juurlink DN. Prevention of opioid overdose. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2246–2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brummett CM, Evans-Shields J, England C, et al. Increased health care costs associated with new persistent opioid use after major surgery in opioid-naive patients. JMCP. 2021;27:760–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brescia AA, Waljee JF, Hu HM, et al. Impact of prescribing on new persistent opioid use after cardiothoracic surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;108:1107–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Aalberg JJ, Kimball MD, McIntire TR, et al. Long-term outcomes of persistent post-operative opioid use: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Surg. 2022. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wilton J, Abdia Y, Chong M, et al. Purssell R. Prescription opioid treatment for non-cancer pain and initiation of injection drug use: large retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2021;375:e066965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Elm Ev, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Healy MA, Regenbogen SE, Kanters AE, et al. Surgeon Variation in Complications With Minimally Invasive and Open Colectomy. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:860–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Campbell DA Jr, Kubus JJ, Henke PK, et al. The Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative: a legacy of Shukri Khuri. Am J Surg. 2009;198(5 Suppl):S49–S55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chua KP, Hu HM, Waljee JF, et al. Persistent opioid use associated with dental opioid prescriptions among publicly and privately insured US patients, 2014 to 2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e216464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medicaid and the Opioid Epidemic. https://www.macpac.gov/publication/medicaid-and-the-opioid-epidemic/ MACPAC. Accessed November 13, 2022:

- 18. Howard R, Brown CS, Lai Y-L, et al. Postoperative opioid prescribing and new persistent opioid use: the risk of excessive prescribing. Ann Surg. 2022;277:e1225–e1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bicket MC, Gunaseelan V, Lagisetty P, et al. Association of opioid exposure before surgery with opioid consumption after surgery. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2022;47:346–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barth RJ Jr, Porter ED, Kelly JL, et al. Reasons for long-term opioid prescriptions after guideline-directed opioid prescribing and excess opioid pill disposal. Ann Surg. 2023;277:173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lawal OD, Gold J, Murthy A, et al. Rate and risk factors associated with prolonged opioid use after surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3:e207367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Waljee JF, Cron DC, Steiger RM, et al. Effect of preoperative opioid exposure on healthcare utilization and expenditures following elective abdominal surgery. Ann Surg. 2017;265:715–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stark N, Kerr S, Stevens J. Prevalence and predictors of persistent post-surgical opioid use: a prospective observational cohort study. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2017;45:700–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hilliard PE, Waljee J, Moser S, et al. Prevalence of preoperative opioid use and characteristics associated with opioid use among patients presenting for surgery. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:929–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Huang Y, Jacobson JS, Tergas AI, et al. Insurance-associated disparities in opioid use and misuse among patients undergoing gynecologic surgery for benign indications. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:565–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lockett MA, Ward RC, McCauley JL, et al. New chronic opioid use in Medicaid patients following cholecystectomy. Surgery Open Science. 2022;9:101–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Samples H, Williams AR, Olfson M, et al. Risk factors for discontinuation of buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorders in a multi-state sample of Medicaid enrollees. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;95:9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mikosz CA, Zhang K, Haegerich T, et al. Indication-specific opioid prescribing for US Patients with medicaid or private insurance, 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e204514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]