Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to identify the genetic cause of aggressive corneal vascularization in otherwise healthy children in one family. Further, to study molecular consequences associated with the identified variant and implications for possible treatment.

Methods

Exome sequencing was performed in affected individuals. HeLa cells were transduced with the identified c.1643C>A, p.(Ser548Tyr) variant in the platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta gene (PDGFRB) or wild-type PDGFRB. ELISA and immunoblot analysis were used to detect the phosphorylation levels of PDGFRβ and downstream signaling proteins in untreated and ligand-stimulated cells. Sensitivity to various receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) was determined.

Results

A novel c.1643C>A, p.(Ser548Tyr) PDGFRB variant was found in affected family members. HeLa cells transduced with this variant did not have increased baseline levels of phosphorylated PDGFRβ. However, upon stimulation with ligand, excessive activation of PDGFRβ was observed compared to cells transduced with the wild-type variant. PDGFRβ with the p.(Ser548Tyr) amino acid substitution was successfully inhibited with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (axitinib, dasatinib, imatinib, and sunitinib) in vitro.

Conclusions

A novel c.1643C>A, p.(Ser548Tyr) PDGFRB variant was found in family members with isolated corneal vascularization. Cells transduced with the newly identified variant showed increased phosphorylation of PDGFRβ upon ligand stimulation. This suggests that PDGF-PDGFRβ signaling in these patients leads to overactivation of PDGFRβ, which could lead to abnormal wound healing of the cornea. The examined TKIs prevented such overactivation, introducing the possibility for targeted treatment in these patients.

Keywords: hereditary corneal vascularization, PDGFRB, activating gene variant, receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors

In the last decade, several ligand-independent, gain-of-function variants in the platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta gene (PDGFRB) have been reported. They have been identified in individuals with a diverse range of disorders. Ocular pterygium digital keloid dysplasia (OPDKD) is associated with a temperature-sensitive, activating p.(Asn666Tyr) substitution in PDGFRβ.1 Patients typically develop extensive corneal vascularization in early childhood, followed by development of keloids on the fingers and toes later in life.1 A more severe phenotype is seen in the Penttinen type of premature aging syndrome, also associated with activating substitutions in PDGFRβ (p.(Asn666Ser) and p.(Val665Ala)) and in Kosaki overgrowth syndrome (KOGS) linked to the substitutions p.(Pro584Arg), p.(Trp566Arg), p.(Ser493Cys), and p.(Asn856Ile). In these two syndromes, multiple organs are involved. Penttinen syndrome is associated with tissue wasting leading to fragile lipodystrophic skin with ulcerations, acro-osteolysis, and corneal vascularization in early adulthood.2–5 Kosaki overgrowth syndrome is a somatic overgrowth syndrome characterized by distinctive facial features, accelerated growth with elongated hands and feet, thin and fragile skin, vascularized corneal overgrowth, white matter lesions in the central nervous system (CNS), and developmental delay.6–11 It remains unclear why these gain-of-function syndromes are so phenotypically diverse. However, molecular studies on intracellular signaling pathways indicate that each syndrome has a unique pattern of activated downstream signaling proteins.1–3,5,6,12,13

Various constitutively active gain-of-function PDGFRβ substitutions have been successfully targeted with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in in vitro studies.1,2,5,12,14,15 Several individuals carrying such substitutions have shown clinical improvement when treated with TKIs, typically imatinib.12,15 Interestingly, an individual with the p.Val665Ala PDGFRβ substitution exhibited partial clinical improvement with imatinib but showed a more favorable response to dasatinib treatment.5

In this report, we describe a novel variant in PDGFRB, c.1643C>A, p.(Ser548Tyr), found in 3 family members presenting with aggressive and early-onset corneal vascularization leading to severe visual impairment. In contrast to the other reported PDGFRB variants, individuals with the c.1643C>A, p.(Ser548Tyr) variant are otherwise healthy.16 Although the p.(Ser548Tyr) substitution was not constitutively active, ligand-induced overactivation of PDGFRβ and downstream signaling were seen after stimulation with platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF). Both ligand-induced overactivation of PDGFRβ and downstream signaling were inhibited by several TKIs.

Materials and Methods

Ethical Approval

The Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, Western Norway (IRB.no.00001872, project number 2014/59) approved the study. Informed written consent was obtained from affected individuals prior to genetic analysis. The study thus adhered to the Tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Isolation of DNA, Genotyping, and Exome Sequencing

Blood samples for genotyping were obtained and genomic DNA was isolated. We examined three DNA samples from affected family members (individual II-3, who was legally blind from central corneal scarring with associated peripheral vascularization, and individuals II-1 and III-3).16 Exome sequencing was performed using the Nextera DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, cat # 15028211) and sequenced on a NextSeq 500 sequencer (Illumina). Variants were called using GenomeAnalysisTK version 3.2-2-gec30cee,17 following the Broad institute's recommended best practice. Filtration was performed using VCFtools,18 and annotation of variants was performed using ANNOVAR.19

Transduction of Cells

HeLa cells (ATCC CCl-2) were grown in Dulbecco‘s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum. Transgenic cell preparation was performed as previously described.2 In brief, a murine retroviral vector containing the PDGFRB open-reading frame (NM_002609.3) was obtained from VectorBuilder. The PDGFRB c.wt, c.1996A>T (p.(Asn666Tyr)), or c.1643C>A (p.(Ser548Tyr)) variants were introduced using the QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit. Virus production was achieved by transfecting Phoenix-AMPHO packaging cells. Two days after transfection, the medium was harvested and HeLa cells were transduced. Two days post-infection, stably transduced cells were selected by adding 1 µg/mL puromycin.

Cell Culture and Stimulation With PDGF

Transduced HeLa cells were seeded in 6-well plates. When the cells were 80% confluent, they were serum-starved for 16 hours and stimulated with PDGF (Platelet-Derived Growth Factor from human platelets; P8147-5UG; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany; 2.5, 12.5, and 15 ng/mL in 4 mM HCl containing 0.1% BSA) for 20 minutes or with 4 mM HCl containing 0.1% BSA alone as control. According to the manufacturer, the PDGF isolated from platelets consists of approximately 70% PDGF-AB, 20% PDGF-BB, and 10% PDGF-AA. Cells were harvested in 1% NP-40, 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 137 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM activated sodium orthovanadate, 10 µg/mL Aprotinin (#4139; Tocris, Abington, United Kingdom), 10 µg/mL Leupeptin (Leupeptin hemisulfate, #1167; Tocris, Abington, United Kingdom), and stored at −80°C until immunoblot or ELISA analysis was performed.

Reduction of Temperature and Glucose Deprivation

Transduced HeLa cells were either kept at 37°C or incubated overnight at the physiological corneal temperature of 32°C.20,21 Cells transduced with retroviruses expressing the temperature-sensitive p.(Asn666Tyr) PDGFRB variant were used as controls. Cells were harvested as described above.

To examine the effect of glucose deprivation, the medium of the transduced cells was replaced with glucose-free and serum-free DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.; #11966025) for 24 hours.

Treatment With Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

Three different concentrations were used for treatment with axitinib (AG 013746), dasatinib (BMS-354825), imatinib (STI571), and sunitinib (SU11248) (all purchased from Selleckchem, Munich, Germany). First, we conducted an in-house determination of half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) to evaluate the potency of each drug in our inventory. This was done by stimulating wild-type transduced HeLa cells with PDGF (15 ng/mL), and then determining the drug concentration inhibiting half of the induced PDGFRβ phosphorylation for each TKI (Supplementary Fig. S1). In addition to these in-house concentrations, we used two other dilutions, including the one recommended by the manufacturer (if available), and the IC50 concentrations from the review article by Heldin.22 Transduced HeLa cells serum-starved for 6 hours were treated with axitinib, dasatinib, imatinib, and sunitinib dissolved in DMSO, at these concentrations (see the Table), or with DMSO alone as a control for 6 hours. Cells were stimulated with 12.5 ng/mL PDGF 20 minutes prior to harvesting.

Table.

Concentrations of the TKIs Used in this Study

| Selleckchem | Heldin Literature Review22 | Titration Studies From This Study | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Axitinib | 1.6 nM | 1.6 nM | 2 nM |

| Dasatinib | Not given* | 28 nM | 8 nM |

| Imatinib | 100 nM | 380 nM | 86 nM |

| Sunitinib | 2 nM | 10 nM | 5.6 nM |

The manufacturer does not give dasatinib IC50 for PDGFRβ. Still, the manufacturer states that dasatinib targets Abl, Src, and c-Kit with IC50 of <1 nM, 0.8 nM, and 79 nM in cell-free assays, respectively. In this study, we used 100 nM dasatinib as previously described.5

Glucose-deprived cells were treated with axitinib, dasatinib, imatinib, and sunitinib 6 hours prior to harvesting. For this experiment, only TKI concentrations from the in-house titration study were used.

ELISA and Immunoblot Analysis

ELISA and immunoblot analyses were performed as previously described.2 In brief, ELISA analysis was conducted using a DuoSet IC PDGFRβ kit (# DYC1767-2, R&D systems) in accordance with the guidelines provided by the manufacturer. In this kit, the total phosphorylation levels of PDGFRβ are measured using an immobilized antibody binding PDGFRβ and an HRP-conjugated antibody against phosphorylated tyrosine. For immunoblot analysis, protein separation was carried out using a high-resolution gel system (4–12% NuPAGE Novex Bis-Tris Gel; Life, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk (Bio-Rad), 1% glycine, and 1% BSA in PBS-T buffer (standard PBS with 0.05% Tween 20). They were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies from Cell Signalling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA) used at recommended dilutions (catalogue numbers in parentheses): phospho-Tyr70-STAT1 (#7649), STAT1 (#9172), phospho-Tyr783-PLCγ1 (#2821), PLCγ1 (#5690), phospho-Ser473-AKT (#4060), phospho-AKTThr308 (#4056), AKT (#4691), phospho-38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182; #9211), phospho-Thr202/Tyr204-MAPK3/ERK1 (#4370), and MAPK3/ERK1 (#4695). To control for equal loading, anti-GAPDH antibodies (Sigma #G99545) were used. ImageJ software was used for relative quantification of immunoblot band intensity.

Statistical Analysis and Reproducibility

Paired t-test was performed to compare PDGFRβ phosphorylation levels measured with ELISA. All results were replicated in at least three independent experiments. Representative images are shown in the figures.

Results

Clinical Examination

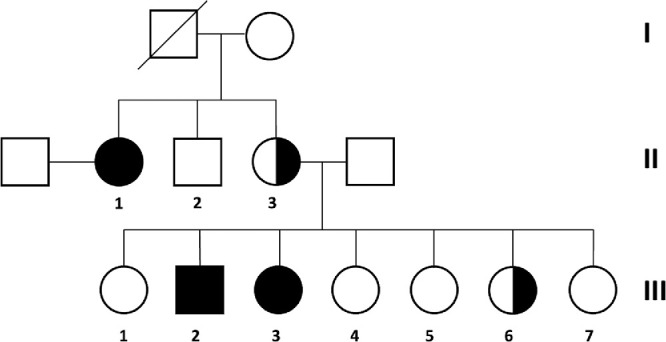

The family has been described previously.16 To summarize, aggressive corneal changes diagnosed as pterygium with extension across the visual axis appeared early in life in three otherwise healthy family members (individuals II-1, III-2, and III-3). In addition, individual II-3 had central corneal scarring with associated peripheral vascularization, and individual III-6 had dense corneal opacity, lateral rectus palsy, and unilateral horizontal nystagmus (Fig. 1).

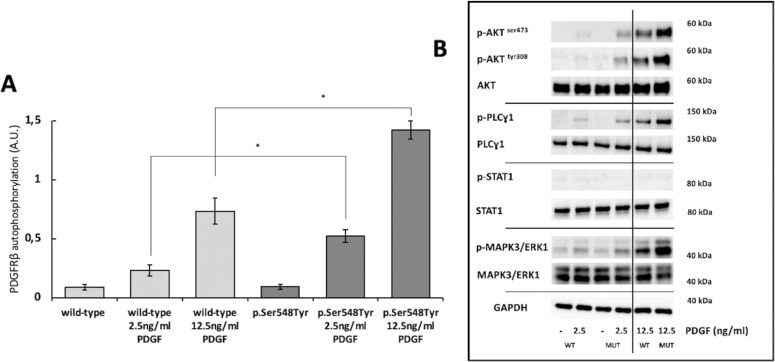

Figure 1.

Pedigree indicating affected family members. Individuals II-1, III-2, and III-3 developed pterygium in the early 20s, and at 6, and 4 years of age, respectively (fully-shaded symbols). Individuals II-1 and III-3 had a unilateral pterygium, whereas bilateral pterygium was seen in III-2. Individual II-3 was declared legally blind from central corneal scarring with associated peripheral vascularization, and III-6 had severe visual impairment due to dense corneal opacity in the left eye (half-shaded symbols). Individuals II-1, II-3, and III-3 were included in this study. The clinical data are summarized in the supplementary materials (Supplementary Table S1).

A Novel PDGFRB Variant

Exome sequencing revealed a variant in PDGFRB, NM_002609.3: c.1643C>A, p.(Ser548Tyr) shared by all 3 affected individuals. This previously unreported variant is absent in gnomAD, dbSNP, and other variant databases. Additionally, it has not been detected in in-house samples subjected to exome sequencing at the Department of Medical Genetics, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway. The missense variant changes a highly conserved amino acid located in the transmembrane domain of PDGFRβ (Supplementary Fig. S2). There is a major physicochemical difference between Ser and Tyr, and the variant was predicted to be damaging by SIFT and MutationTaster.

The PDGFRβ p.(Ser548Tyr) Substitution Does Not Cause Ligand-Independent Auto-Activation

In HeLa cells stably transduced with either the c.1643C>A, p.(Ser548Tyr), or wild-type PDGFRB vector, similar levels of both PDGFRβ and phosphorylated PDGFRβ were observed (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Fig. S3). In line with this, comparable phosphorylation levels of the examined PDGFRβ downstream signaling proteins (p-AKTSer473, p-AKTTyr308, p-PLCɣ1, p- MAPK3/ERK1, and p-STAT1) were found (Fig. 2B). This indicates that the p.(Ser548Tyr) substitution is not causing constitutive ligand-independent auto-activation of PDGFRβ.

Figure 2.

(A) Levels of phosphorylated PDGFRβ measured by ELISA analysis. The untreated wild-type and p.(Ser548Tyr) cells have comparable PDGFRβ phosphorylation levels. Upon stimulation with PDGF (2.5 ng/mL and 12.5 ng/mL), higher PDGFRβ phosphorylation levels were found in p.(Ser548Tyr) cells. Data are shown as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. Paired t-test was performed to compare wild-type and p.(Ser548Tyr) response to PDGF stimulation, * P < 0.01. (B) Representative images showing effect of ligand stimulation on PDGFRβ downstream signaling proteins. Increased levels of downstream signaling proteins, p-AKTSer473, p-AKTTyr308, and p-PLCɣ1 upon PDGF stimulation were seen in p.(Ser548Tyr) cells, whereas no such effect was seen on p-STAT1. Upon stimulation with low levels of PDGF, comparable levels of p-MAPK3/ERK1 were found, whereas at high concentration (12.5 ng/mL) increased phosphorylation levels were observed in p.(Ser548Tyr) cells. The p-AKTSer473/GAPDH, p-AKTTyr308/GAPDH, and p-PLC ɣ1/GAPDH ratios upon stimulation with 2.5 ng/mL PDGF were 4.9, 12.8, and 3.7 folds higher in p.(Ser548Tyr) cells compared to wild-type cells. All results were replicated in at least three independent experiments. ELISA analysis data point distributions, full immunoblottings, and quantification of representative images are shown in Supplementary Figures S4 and S5.

The PDGFRβ p.(Ser548Tyr) Substitution Causes Ligand-Dependent Over-Activation

When p.(Ser548Tyr) cells were stimulated with 2.5 or 12.5 ng/mL PDGF, increased levels of phosphorylated PDGFRβ (see Fig. 2A) were seen compared to wild-type cells, with a 2.2 and 1.9 fold increase, respectively. This indicated that the p.(Ser548Tyr) amino acid substitution leads to excessive PDGFRβ activation upon ligand binding.

We next examined downstream signaling proteins after ligand stimulation. Although comparable levels of p-STAT1 were found in p.(Ser 548Tyr) and wild-type cells, increased phosphorylation of p-AKTSer473, p-AKTTyr308, and p-PLCɣ1, were present in cells expressing the p.(Ser548Tyr) substitution (see Fig. 2B) at both ligand concentrations. For phospho-Thr202/Tyr-MAPK3/ERK1, a different pattern was seen. Here, comparable levels were present upon stimulation with low ligand concentration (2.5 ng/mL) in both cell types, whereas stimulation with 12.5 ng/mL PDGF led to higher levels in p.(Ser548Tyr) cells.

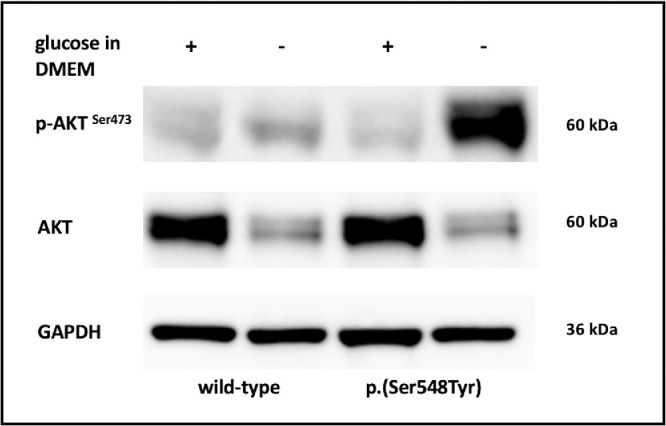

The PDGFRβ p.(Ser548Tyr) Substitution is not Temperature Sensitive but is Responsive to Glucose Deprivation

Upon prolonged glucose withdrawal (24 hours), increased levels of p-AKTSer473 were observed in p.(Ser548Tyr) cells compared to wild-type cells (Fig. 3). No difference in phosphorylation of PDGFRβ or downstream signaling protein p-AKTTyr308, p-PLCɣ1, p-ERK1/2, and p-STAT1 was found (Supplementary Fig. S6). Comparable phosphorylation levels of PDGFRβ and downstream signaling partners were observed for p.(Ser548Tyr) and wild-type cells upon exposure to the corneal physiological temperature of 32°20,21 (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Figure 3.

Representative images showing immunoblot analysis of AKT, p-AKTSer473, and GAPDH in wild type cells and cells expressing the p.(Ser548Tyr) substitution cultivated with and without glucose. The p-AKTSer473/GAPDH ratio in p.(Ser548Tyr) cells after glucose withdrawal compared with wild-type cells after glucose withdrawal, and with p.(Ser548Tyr) cells under normal glucose conditions was 5.8 folds and 14 folds higher, respectively. All results were replicated in at least three independent experiments. Full immunoblotting and quantification of representative images are shown in Supplementary Figure S6.

Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Inhibit the PDGFRβ p.(Ser548Tyr) Ligand-Dependent Over-Activation

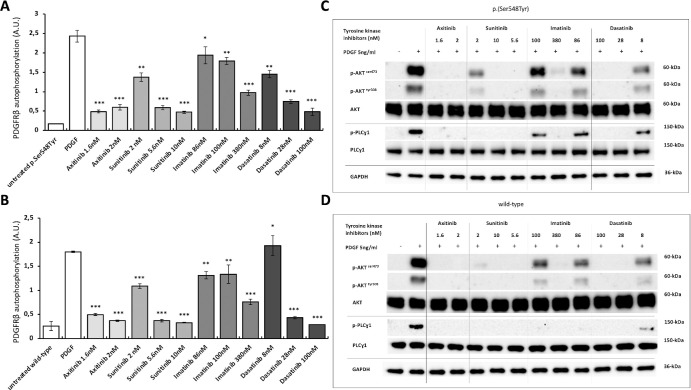

All the examined TKIs (axitinib, dasatinib, imatinib, and sunitinib) inhibited the ligand-induced activation of PDGFRβ and its downstream signaling partners both in p.(Ser548Tyr) and wild-type cells (Fig. 4). Of these, axitinib at both 1.6 nM and 2 nM concentrations reduced the phosphorylated PDGFRβ by 4.2 to 5-fold. This was more effective than imatinib achieving 1.3 and 2.5-fold reduction, respectively, at comparable concentrations (86 nM and 380 nM). Sunitinib and dasatinib reduced activation ranging from 1.8 to 5.2 and 1.5 to 5.4 fold, respectively (see Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Effect of tyrosine kinase inhibitors on PDGFRβ and downstream signaling proteins. Panels (A) and (B) show ligand-induced PDGFRβ autophosphorylation levels measured with ELISA in p.(Ser548Tyr) (A) and wild type (B) cells after incubation with four tyrosine kinase inhibitors (axitinib, dasatinib, imatinib, and sunitinib) at different concentrations. Data are shown as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. Paired t-test was performed to compare drug effect on PDGF-stimulated PDGFRβ. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, and *** P < 0.001. Panels (C) and (D) show representative images of immunoblot analysis of downstream signaling proteins in p.(Ser548Tyr) (C) and wild-type (D) cells after incubation with tyrosine kinase inhibitors at different concentrations. Axitinib, at all used concentrations, most effectively inhibited phosphorylated PDGF/PDGFRβ and downstream signaling cascades. All results were replicated in at least three independent experiments. ELISA analysis data point distributions, full immunoblottings, and quantification of representative images are shown in Supplementary Figures S9 to S11.

The increased levels of p-AKTSer473 seen upon glucose withdrawal were also inhibited with all tested TKIs (Supplementary Fig. S8).

Discussion

PDGF is an extracellular signaling molecule with a vital role during embryonal development, hematopoiesis, and wound healing.23–25 Together with factors like BMP2, BMP4, and IL-1α, PDGF signaling plays a crucial role in fibroblast chemotaxis and proliferation, influencing corneal health and injury recovery.26 PDGF binds to PDGFRα and PDGFRβ, two receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) with a nearly identical domain structure, including five extracellular immunoglobulin (Ig) loops, a helical transmembrane domain, a juxtamembrane region, and a split intracellular tyrosine kinase (TK) domain. After stimulation with PDGF, dimerization of PDGFRs triggers an auto-catalyzed trans-phosphorylation in the intracellular domain.27 The receptors’ phosphorylated tyrosine residues become specific docking platforms to recruit SH2 or PTB domains containing effector proteins.

In members of a family presenting with early-onset corneal vascularization, we found a novel missense variant in PDGFRB, c.1643C>A, p.(Ser548Tyr). The variant is located in exon 11, leading to a p.(Ser548Tyr) substitution in the PDGFRβ transmembrane domain. This exon is highly conserved among various animal species (see Supplementary Fig. S2). Patients carrying the p.(Ser548Tyr) substitution have similar corneal changes as patients with OPDKD.1 The corneal overgrowth is more aggressive than what has been reported in Penttinen type of premature aging syndrome2,5 and Kosaki overgrowth syndrome.8,9 These diseases are all caused by PDGFRB variants leading to ligand-independent activation of the kinase.

It has been shown that the transmembrane (TM) domain of RTKs contributes to the stability of full-length dimers. Thus, this part of the kinase is thought to be important for maintaining a signaling-competent dimeric receptor conformation.28–30 There is a broad spectrum of phenotypes in human diseases arising from disease-causing substitutions in the TM domain of various RTKs.29 It has been suggested that these substitutions can activate RTKs by several mechanisms, such as by altering dimerization, ligand binding, or phosphorylation.31 We observed ligand-induced overactivation of PDGFRβ and downstream signaling proteins (see Fig. 2), possibly due to altered phosphorylation of the kinase caused by the p.(Ser548Tyr) substitution.

In contrast to the previously reported PDGFRB variants, we found that the p.(Ser548Tyr) substitution is not causing constitutive ligand-independent activation (see Fig. 2). Instead, the p.(Ser548Tyr) substitution caused ligand-dependent PDGFRβ overactivation. (see Fig. 2A). In line with this, upregulation of downstream signaling proteins, AKTTyr308, AKTSer473, and PLCɣ1, were found upon ligand stimulation (see Fig. 2B). The cornea is constantly exposed to minor traumas/scratches,32,33 which can lead to the secretion of PDGF.34,35 Although speculative, individuals carrying the PDGFRB p.(Ser548Tyr) variant may have an excessive wound healing response to such minor corneal traumas, in turn leading to corneal vascularization. Details on the ocular microenvironment, such as the tear film, meibomian gland function, and the lid margins were not described in the case report16 but may be relevant for the observed phenotype.

The avascular cornea has unique environmental conditions, such as a low physiological temperature (30-32°C) and low glucose levels.36–45 A temperature-sensitive mutation in PDGFRB, p.(Asn666Tyr) is associated with corneal vascularization.1 Such a response to the physiological corneal temperature was not found in p.(Ser548Tyr) cells. Glucose starvation, however, caused an upregulation of p-AKTSer473 (see Fig. 3), in p.(Ser548Tyr) cells. Graham and co-workers described that glucose withdrawal may initiate a positive feedback loop involving the generation of reactive oxygen species and inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatases by oxidation, hence increasing tyrosine kinase signaling.46 However, the precise mechanism behind the observed increase in AKT signaling upon glucose starvation remains to be elucidated.

AKT and PLCY1 phosphorylation have important roles in PDGFRβ ligand-induced cell proliferation, differentiation, survival, growth, migration, and angiogenesis.47–49 Interestingly, the AKT signaling pathway is important for the effect of PDGFRβ p.(Asn666Tyr) associated with OPDKD, suggesting that it is important for the corneal overgrowth phenotype. In contrast, increased STAT1 signaling has been linked to tissue wasting,50 among others in Penttinen syndrome.2,5,13 Our affected family members have no degenerative features and in line with this, no STAT1 upregulation was observed (see Fig. 2B).

Individuals with activating mutations in PDGFRB are candidates for treatment with TKIs, with imatinib being the most widely used.1,2,5,12–15 However, recent studies with various gain-of-function variants in PDGFRB suggest that there are differences in the sensitivity to various TKIs.5,12–14 When examining different TKIs (axitinib, dasatinib, imatinib, and sunitinib), we observed that all four TKIs inhibited PDGFRβ activation in ligand-stimulated p.(Ser548Tyr), wild-type cells (see Fig. 4) and upregulated p-AKTSer473 after glucose deprivation (see Supplementary Fig. S8). In addition, variation in the potency of the TKIs at different concentrations was observed (see Fig. 4), with axitinib being somewhat more effective in inhibiting ligand-induced PDGFRβ phosphorylation. By using the most potent drug, clinicians could titrate the lowest drug dosage within the therapeutic window minimizing risks of side effects of the TKIs.51

Alternative treatment options for gain-of-function PDGFRB variants may include anti-PDGF antibodies or antibody-drug conjugates.52,53 A number of additional approaches for treating corneal vascularization are being explored, from targeting the VEGF-pathway to stem cell transplantation.54–56 Further research is required to decide the best treatment options for gain-of-function PDGFRB variants leading to corneal overgrowth.

In summary, we present a novel PDGFRB p.(Ser548Tyr) variant associated with severe corneal vascularization. The substitution leads to ligand-depended overactivation of the kinase and downstream signaling, in particular AKT signaling. Targeted treatment using TKIs might be an option in patient treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Unni Larsen for technical assistance.

Supported by grants from the Western Norway Regional Health Authority (911977 and 912161 to C.B.), Gidske og Peter Jacob Sørensens Forskningsfond (to T.G), Olav Raaholt og Gerd Meidel Raagholts stiftelsen (to T.G.), and Futura Fund for scientific medical research (to C.B.).

Disclosure: T. Gladkauskas, None; O. Bruland, None; L. Abu Safieh, None; D.P. Edward, None; E. Rødahl, None; C. Bredrup, None

References

- 1. Bredrup C, Cristea I, Safieh LA, et al.. Temperature-dependent autoactivation associated with clinical variability of PDGFRB Asn666 substitutions. Hum Mol Genet. Published online January 15, 2021:ddab014, doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddab014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bredrup C, Stokowy T, McGaughran J, et al.. A tyrosine kinase-activating variant Asn666Ser in PDGFRB causes a progeria-like condition in the severe end of Penttinen syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2019; 27(4): 574–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johnston JJ, Sanchez-Contreras MY, Keppler-Noreuil KM, et al.. A point mutation in PDGFRB causes autosomal-dominant Penttinen syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2015; 97(3): 465–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aggarwal B, Correa ARE, Gupta N, Jana M, Kabra M. First case report of Penttinen syndrome from India. Am J Med Genet A. 2022; 188(2): 683–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Iznardo H, Bredrup C, Bernal S, et al.. Clinical and molecular response to dasatinib in an adult patient with Penttinen syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. Published online December 11, 2021:ajmg.a.62603, doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.62603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zarate YA, Boccuto L, Srikanth S, et al.. Constitutive activation of the PI3K-AKT pathway and cardiovascular abnormalities in an individual with Kosaki overgrowth syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2019; 179(6): 1047–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Minatogawa M, Takenouchi T, Tsuyusaki Y, et al.. Expansion of the phenotype of Kosaki overgrowth syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2017; 173(9): 2422–2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Foster A, Chalot B, Antoniadi T, et al.. Kosaki overgrowth syndrome: a novel pathogenic variant in PDGFRB and expansion of the phenotype including cerebrovascular complications. Clin Genet. 2020; 98(1): 19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mutlu Albayrak H, Calder AD.. Kosaki overgrowth syndrome: report of a family with a novel PDGFRB variant. Mol Syndromol. Published online September 29, 2021: 1–7, doi: 10.1159/000517978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Takenouchi T, Yamaguchi Y, Tanikawa A, Kosaki R, Okano H, Kosaki K.. Novel overgrowth syndrome phenotype due to recurrent de novo PDGFRB mutation. J Pediatr. 2015; 166(2): 483–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gawliński P, Pelc M, Ciara E, et al.. Phenotype expansion and development in Kosaki overgrowth syndrome. Clin Genet. 2018; 93(4): 919–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rustad CF, Tveten K, Prescott TE, Bjerkeseth PO, Bredrup C, Pfeiffer HCV.. Positive response to imatinib in PDGFRB -related Kosaki overgrowth syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2021; 185(8): 2597–2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nédélec A, Guérit EM, Dachy G, et al.. Penttinen syndrome-associated PDGFRB Val665Ala variant causes aberrant constitutive STAT1 signalling. J Cell Mol Med. 2022; 26(14): 3902–3912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Arts FA, Chand D, Pecquet C, et al.. PDGFRB mutants found in patients with familial infantile myofibromatosis or overgrowth syndrome are oncogenic and sensitive to imatinib. Oncogene. 2016; 35(25): 3239–3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pond D, Arts FA, Mendelsohn NJ, Demoulin JB, Scharer G, Messinger Y.. A patient with germ-line gain-of-function PDGFRB p.N666H mutation and marked clinical response to imatinib. Genet Med. 2018; 20(1): 142–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Islam SI, Wagoner MD.. Pterygium in young members of one family. Cornea. 2001; 20(7): 708–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al.. The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010; 20(9): 1297–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Danecek P, Auton A, Abecasis G, et al.. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics. 2011; 27(15): 2156–2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H.. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010; 38(16): e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Slettedal JK, Ringvold A.. Correlation between corneal and ambient temperature with particular focus on polar conditions. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 2015; 93(5): 422–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kessel L, Johnson L, Arvidsson H, Larsen M.. The relationship between body and ambient temperature and corneal temperature. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci. 2010; 51(12): 6593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Heldin CH. Targeting the PDGF signaling pathway in the treatment of non-malignant diseases. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2014; 9(2): 69–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Andrae J, Gallini R, Betsholtz C.. Role of platelet-derived growth factors in physiology and medicine. Genes Dev. 2008; 22(10): 1276–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pierce GF, Mustoe TA, Altrock BW, Deuel TF, Thomason A.. Role of platelet-derived growth factor in wound healing. J Cell Biochem. 1991; 45(4): 319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gao Z, Sasaoka T, Fujimori T, et al.. Deletion of the PDGFR-β gene affects key fibroblast functions important for wound healing. J Biol Chem. 2005; 280(10): 9375–9389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim WJ, Mohan RR, Mohan RR, Wilson SE.. Effect of PDGF, IL-1alpha, and BMP2/4 on corneal fibroblast chemotaxis: expression of the platelet-derived growth factor system in the cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999; 40(7): 1364–1372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kelly JD, Haldeman BA, Grant FJ, et al.. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) stimulates PDGF receptor subunit dimerization and intersubunit trans-phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1991; 266(14): 8987–8992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bocharov EV, Mineev KS, Volynsky PE, et al.. Spatial structure of the dimeric transmembrane domain of the growth factor receptor ErbB2 presumably corresponding to the receptor active state. J Biol Chem. 2008; 283(11): 6950–6956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li E, Hristova K.. Role of receptor tyrosine kinase transmembrane domains in cell signaling and human pathologies. Biochemistry. 2006; 45(20): 6241–6251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li E, Hristova K.. Receptor tyrosine kinase transmembrane domains: function, dimer structure and dimerization energetics. Cell Adhes Migr. 2010; 4(2): 249–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. He L, Hristova K.. Physical–chemical principles underlying RTK activation, and their implications for human disease. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Biomembr. 2012; 1818(4): 995–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sun D, Gong L, Xie J, et al.. Toxicity of silicon dioxide nanoparticles with varying sizes on the cornea and protein corona as a strategy for therapy. Sci Bull. 2018; 63(14): 907–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kashiwagi K, Iizuka Y.. Effect and underlying mechanisms of airborne particulate matter 2.5 (PM2.5) on cultured human corneal epithelial cells. Sci Rep. 2020; 10(1): 19516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vesaluoma M, Teppo AM, Grönhagen-Riska C, Tervo T.. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB) in tear fluid: a potential modulator of corneal wound healing following photorefractive keratectomy. Curr Eye Res. 1997; 16(8): 825–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hoppenreijs VP, Pels E, Vrensen GF, Treffers WF.. Effects of platelet-derived growth factor on endothelial wound healing of human corneas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994; 35(1): 150–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cohen GY, Ben-David G, Singer R, et al.. Ocular surface temperature: characterization in a large cohort of healthy human eyes and correlations to systemic cardiovascular risk factors. Diagnostics. 2021; 11(10): 1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yang WL, Zhang L.. Normal range of temperature of cornea on ocular surface of healthy people in Pudong New District of Shanghai. J Shanghai Jiaotong Univ Med Sci. 2010; 30: 832–834. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cejková J, Stípek S, Crkovská J, et al.. UV rays, the prooxidant/antioxidant imbalance in the cornea and oxidative eye damage. Physiol Res. 2004; 53(1): 1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Delic NC, Lyons JG, Di Girolamo N, Halliday GM.. Damaging effects of ultraviolet radiation on the cornea. Photochem Photobiol. 2017; 93(4): 920–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Thoft RA. Corneal glucose concentration: flux in the presence and absence of epithelium. Arch Ophthalmol. 1971; 85(4): 467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Turss R, Friend J, Reim M, Dohlman CH.. Glucose concentration and hydration of the corneal stroma. Ophthalmic Res. 1971; 2(5): 253–260. [Google Scholar]

- 42. McCarey BE, Schmidt FH.. Modeling glucose distribution in the cornea. Curr Eye Res. 1990; 9(11): 1025–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Domingo E, Moshirfar M, Zabbo CP.. Corneal abrasion. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Li X, Kang B, Eom Y, et al.. Comparison of cytotoxicity effects induced by four different types of nanoparticles in human corneal and conjunctival epithelial cells. Sci Rep. 2022; 12(1): 155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Xiang P, He RW, Han YH, Sun HJ, Cui XY, Ma LQ.. Mechanisms of housedust-induced toxicity in primary human corneal epithelial cells: oxidative stress, proinflammatory response and mitochondrial dysfunction. Environ Int. 2016; 89–90: 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Graham NA, Tahmasian M, Kohli B, et al.. Glucose deprivation activates a metabolic and signaling amplification loop leading to cell death. Mol Syst Biol. 2012; 8(1): 589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Caglayan E, Vantler M, Leppänen O, et al.. Disruption of platelet-derived growth factor–dependent phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and phospholipase Cγ 1 activity abolishes vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration and attenuates neointima formation in vivo. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 57(25): 2527–2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Manning BD, Toker A. AKT/PKB signaling: navigating the network. Cell. 2017; 169(3): 381–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hajicek N, Keith NC, Siraliev-Perez E, et al.. Structural basis for the activation of PLC-γ isozymes by phosphorylation and cancer-associated mutations. eLife. 2019; 8: e51700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. He C, Medley SC, Kim J, et al.. STAT1 modulates tissue wasting or overgrowth downstream from PDGFRβ. Genes Dev. 2017; 31(16): 1666–1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hartmann J, Haap M, Kopp HG, Lipp HP.. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors – a review on pharmacology, metabolism and side effects. Curr Drug Metab. 2009; 10(5): 470–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chen L, Wu H, Ren C, et al.. Inhibition of PDGF-BB reduces alkali-induced corneal neovascularization in mice. Mol Med Rep. 2021; 23(4): 238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lee SJ, Kim S, Jo DH, et al.. Specific ablation of PDGFRβ-overexpressing pericytes with antibody-drug conjugate potently inhibits pathologic ocular neovascularization in mouse models. Commun Med. 2021; 1(1): 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chang JH, Garg NK, Lunde E, Han KY, Jain S, Azar DT.. Corneal neovascularization: an anti-VEGF therapy review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012; 57(5): 415–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yazdanpanah G, Haq Z, Kang K, Jabbehdari S, Rosenblatt ML, Djalilian AR.. Strategies for reconstructing the limbal stem cell niche. Ocul Surf. 2019; 17(2): 230–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lee JY, Knight RJ, Deng SX.. Future regenerative therapies for corneal disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2023; 34(3): 267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.