Abstract

BACKGROUND

Percutaneous treatment for trigeminal neuralgia is a safe and effective therapeutic methodology and can be accomplished in the form of balloon compression, glycerol rhizotomy, and radiofrequency thermocoagulation. These procedures are generally well tolerated and demonstrate minimal associated morbidity. Moreover, vascular complications of these procedures are exceedingly rare.

OBSERVATIONS

We present the case of a 64-year-old female with prior microvascular decompression and balloon rhizotomy who presented after symptom recurrence and underwent a second balloon rhizotomy at our institution. Soon thereafter, she presented with pulsatile tinnitus and a right preauricular bruit on physical examination. Subsequent imaging revealed a middle meningeal artery (MMA) to pterygoid plexus fistula and an MMA pseudoaneurysm. Coil and Onxy embolization were used to manage the pseudoaneurysm and fistula.

LESSONS

This case illustrates the potential for MMA pseudoaneurysm formation as a complication of percutaneous trigeminal balloon rhizotomy, which has not been seen in the literature. Concurrent MMA-pterygoid plexus fistula is also a rarity demonstrated in this case.

Keywords: trigeminal neuralgia, percutaneous rhizotomy, arteriovenous fistula, pseudoaneurysm

ABBREVIATION: MMA = middle meningeal artery

The percutaneous approach to the trigeminal nerve via the foramen ovale originated in the early 20th century from Taptas and Hartel in 1911 and 1913,1 respectively, with electrocoagulation developed by Rethi in 1913.2 Over the subsequent century, much advancement in the percutaneous techniques has occurred including chemodenervation, radiofrequency ablation, cryoablation, nerve blocks, Botox injections, nerve stimulation, and balloon decompression.2

Percutaneous treatment for trigeminal neuralgia is generally considered a well-tolerated procedure, with the most common complications of dysesthesia, reduced corneal reflex, paresthesias, and herpes flare.3 Each therapeutic technique in the percutaneous approach has different risk-benefit profiles.4 However, vascular complications are rare. If a case is affected, the most common vascular sequelae is a fistula between the cavernous internal carotid artery and the surrounding venous cavernous sinus.5–17 Other fistulous connections have been reported but are even more infrequent. Pseudoaneurysm formation is exceptionally rare and, to the best of our knowledge, has not been reported. Here, we report the case of a 64-year-old female who developed a pseudoaneurysm of the middle meningeal artery (MMA) as well as a fistulous connection between the MMA and pterygoid plexus as a complication of percutaneous rhizotomy.

Illustrative Case

Presentation

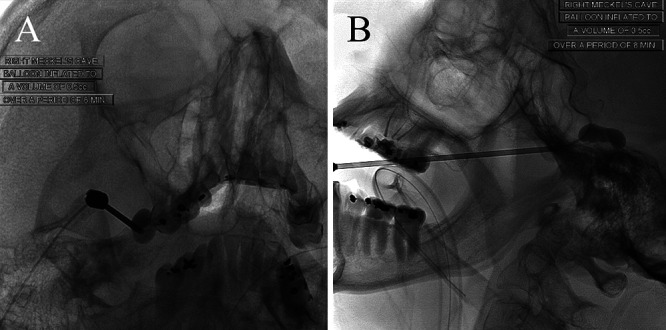

A 64-year-old female initially developed symptoms of bilateral trigeminal neuralgia 40 years prior. In addition, she was status post-right microvascular decompression 23 years prior, balloon rhizotomy 14 years prior, and oxcarbazepine treatment. She described the recurrence of pain on the right as 3–5/10, needle-like, “lightning bolt,” and stabbing. Precipitating events included talking, eating/chewing, brushing her teeth, washing her face, and wind exposure. An increase in medication was not tolerated because of sedative side effects. She underwent a right-sided percutaneous balloon rhizotomy without immediate complication (Fig. 1A and B). She tolerated the procedure well and went home the same day.

FIG. 1.

En fosse and lateral projections of a right-sided balloon rhizotomy with inflation of the balloon up to 0.5 mL for a duration of 8 minutes.

Complication

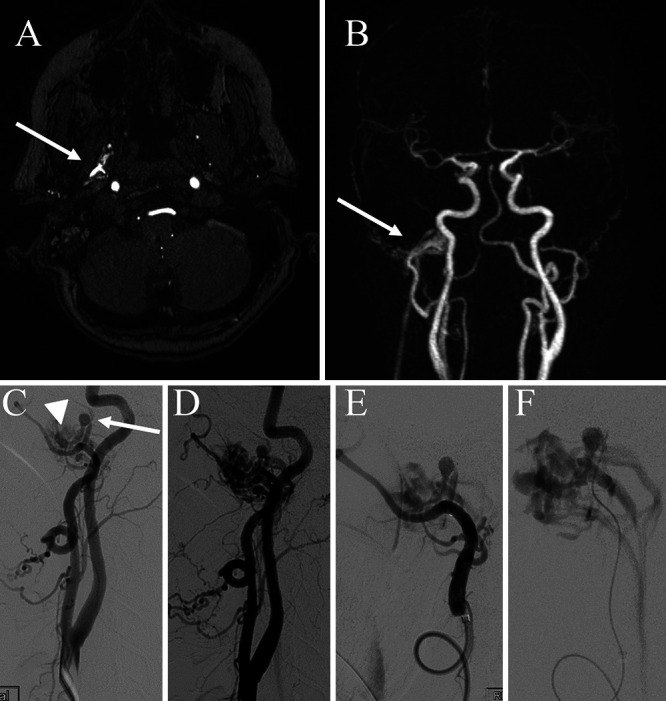

The patient reported symptoms of pulsatile tinnitus 2 weeks after the procedure and demonstrated a right preauricular bruit on a physical exam. Magnetic resonance angiography of the head demonstrated an extracranial fistulous connection of unclear etiology (Fig. 2A and B). Digital subtraction angiography was subsequently performed, which demonstrated an MMA to pterygoid plexus fistula as well as an MMA pseudoaneurysm (Fig. 2C–F).

FIG. 2.

A: Axial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrating an extracranial fistulous connection in the infratemporal fossa resulting in early filling of the pterygoid plexus (arrow). B: Reconstructed coronal maximal intensity projection (MIP) images demonstrate an extracranial carotid connection to the plexus with early filling of the venous network in the arterial phase (arrow). C: Lateral common carotid artery injection demonstrating early venous filling of the pterygoid plexus (arrowhead) and pseudoaneurysm formation arising from the MMA (arrow). D: Slightly more delayed arterial injection with more prominent venous filling. E and F: More selective injection along the internal maxillary artery and super selective injection of the pseudoaneurysm, respectively.

Management

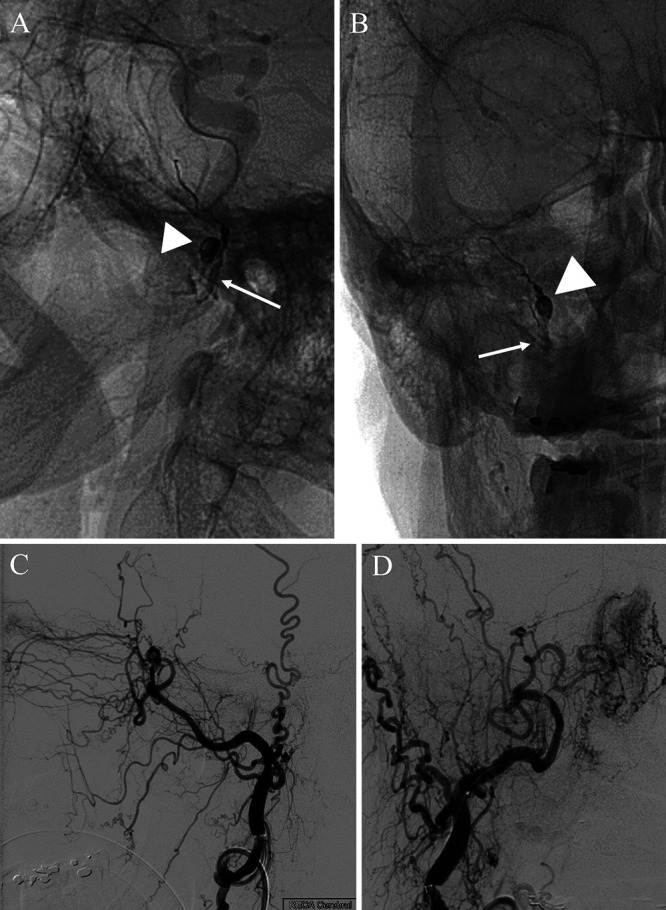

The patient was taken to the angiography suite for further characterization and definitive management. Catheterization of the MMA with microinjections opacifying the pseudoaneurysm and draining veins was performed (Fig. 2C–F). The distal intracranial MMA and its anastomosis to the ophthalmic artery were evaluated. This was followed by coil placement distal to the pseudoaneurysm (within the proximal skull base MMA and foramen spinosum) and subsequently Onyx-34 penetration casting the fistula and immediately proximal MMA supply until the internal maxillary artery was reached (Fig. 3A and B). Final images showed no residual arteriovenous fistula or pseudoaneurysm filling (Fig. 3C and D).

FIG. 3.

A and B: Lateral and frontal projections 4 months after placement of coils in the pseudoaneurysm (arrowheads) and Onyx-34 casting of the proximal MMA until the internal maxillary artery was reached (arrows). C and D: Lateral and frontal injections of the external carotid artery with interval resolution of pseudoaneurysm filling or fistulous connection.

Follow-Up

The patient was seen 5 years later in 2019 for symptoms of left trigeminal neuralgia pain. Residual right-sided numbness was endorsed. No report of tinnitus was documented.

Patient Informed Consent

The necessary patient informed consent was obtained in this study.

Discussion

Observations

We present the case of MMA pseudoaneurysm formation as a complication of percutaneous trigeminal balloon rhizotomy, which, to our knowledge, has not been seen in the literature. Additionally, the pseudoaneurysm occurred concurrently with an MMA-pterygoid plexus fistula, which has been reported only once.5 Fistula formation following rhizotomy is a rare complication, with only 19 cases of fistulous formations reported in the literature.5–17 The majority have been abnormal connections between the cavernous carotid and the surrounding venous plexus of the cavernous sinus. Seven cases have described fistulous connections involving segments of the internal maxillary artery.5,9,11,14,15,17 One connected to the venous cavernous sinus, two to the pterygoid plexus, one to the internal jugular vein, and others were not recorded. One additional nonrhizotomy-related fistulous connection during percutaneous foramen ovale manipulation has been reported between the cavernous internal carotid and the inferior petrosal sinus during foramen ovale telemetry.18

Anatomical variants are thought to be specific risk factors for fistula formation complications. The most commonly referenced anatomical variant thought to predispose patients to a fistulous complication is a primitive foramen lacerum medius in which the foramen ovale and lacerum are conjoined (reported in 4% of the population19) or a primitive foramen lacerum in which the foramen ovale, lacerum, and spinosum form one large foramen (recorded in 3% of the population18). It is thought that this variant causes inadvertent medialization of the percutaneous needle, resulting in injury to the carotid artery. Of the 14 cases reported, only the original case series by Sekhar et al.7 documents a patient with primitive foramen lacerum. Nonetheless, this is a frequent variant of caution reported in subsequent case reports.6–8,10–12 Other case reports have mentioned the foramen of Vesalius18; however, this variant is exceedingly rare.20 Additionally, our patient’s prior balloon rhizotomy likely contributed to scar formation resulting in less reliability when using the traditional anatomical markers. A similar conclusion was suggested by Langford et al.14 in a 72-year-old patient with a previous radiofrequency procedure. To our knowledge, no cases of pseudoaneurysm formation after percutaneous rhizotomy for trigeminal neuralgia have been reported. A prior instance of a pseudoaneurysm of the proximal internal maxillary artery was reported with needle injection for masticatory muscle reduction; however, the exact trajectory was not well described.21 In one rare instance, a pseudoaneurysm was reported as a late complication of Gamma Knife treatment for trigeminal neuralgia.22

Härtel’s anatomical landmarks begin 2.5 cm lateral to the corner of the mouth with the needle directed to intersect an imaginary line along the medial ipsilateral pupil and 2.5 to 3 cm anterior to the external auditory canal.23 Thus, prior to arriving at the foramen ovale, the needle must first transverse the infratemporal fossa, which houses the diffuse pterygoid plexus. This plexus extends from the ramus of the mandible to the lateral pterygoid plate, allowing for connections with the maxillary vein, deep facial vein, and inferior ophthalmic and emissary veins to the cavernous sinus.24 Simultaneously, the infratemporal fossa houses the internal maxillary artery and its branches as the artery dives behind the neck of the mandible until it reaches the pterygopalatine fossa.17 Thus, it is conceivable to have simultaneous injury to these adjacent structures and create an inadvertent fistula, as was seen in our case and twice in the literature,5,15 or an isolated injury to an arterial structure resulting in a pseudoaneurysm or both, as described in our patient.

Previously reported treatments for these fistulas have primarily been endovascular, via embolization/casting at the internal maxillary artery or branches, and one instance of open carotid clipping.8 The durability of these treatments is difficult to reliably characterize because of their infrequent use. One report of distal embolization failure for an iatrogenic fistula resulted in the need for carotid embolization. In this instance, the authors noted a very high-flow fistula in which arterial steal occurred from the left internal carotid artery to the fistula. This patient was noted to have filling of the affected hemisphere through the contralateral circulation via the anterior communicating, and after a 15-minute test occlusion demonstrated no deficits, the internal carotid artery was sacrificed proximal to the ophthalmic.12 In the largest series of cases, Li et al.17 demonstrated no vascular recurrences with a mean follow up of 20 months. Spontaneous closure has been reported, twice within 3 months and once within 3 weeks. Our patient was most recently seen in a pain clinic 5 years after treatment with persistent numbness on her affected side. No symptoms of her prior fistula or pseudoaneurysm were reported.

Lessons

Care should be utilized when conducting a percutaneous rhizotomy for trigeminal neuralgia, and one should be mindful of the vascular structures and anatomical variants that can arise. Knowledge of possible vascular complications is critical for the early diagnosis and management of these rare complications.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Ismail, Kessler. Acquisition of data: Ismail, Kessler. Analysis and interpretation of data: Ismail, Schartz, Kessler. Drafting the article: Ismail, Van Hoang, Kessler. Critically revising the article: all authors. Reviewed submitted version of manuscript: all authors. Approved the final version of the manuscript on behalf of all authors: Ismail. Administrative/technical/material support: Van Hoang, Kessler. Study supervision: Kessler.

References

- 1. Iwanaga J, Badaloni F, Laws T, Oskouian RJ, Tubbs RS. Anatomic study of extracranial needle trajectory using Hartel technique for percutaneous treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. World Neurosurg. 2018;110:e245–e248. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.10.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Xu R, Xie ME, Jackson CM. Trigeminal neuralgia: current approaches and emerging interventions. J Pain Res. 2021;14:3437–3463. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S331036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Noorani I, Lodge A, Durnford A, Vajramani G, Sparrow O. Comparison of first-time microvascular decompression with percutaneous surgery for trigeminal neuralgia: long-term outcomes and prognostic factors. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2021;163(6):1623–1634. doi: 10.1007/s00701-021-04793-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cheng JS, Lim DA, Chang EF, Barbaro NM. A review of percutaneous treatments for trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery. 2014;10(suppl 1):25–33. doi: 10.1227/NEU.00000000000001687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Champeaux C, Shieff C. Middle meningeal arteriovenous fistula following percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy. Clin Neuroradiol. 2016;26(1):103–107. doi: 10.1007/s00062-015-0390-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gatto LAM, Tacla R, Koppe GL, Junior ZD. Carotid cavernous fistula after percutaneous balloon compression for trigeminal neuralgia: Endovascular treatment with coils. Surg Neurol Int. 2017;8:36. doi: 10.4103/sni.sni_443_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sekhar LN, Heros RC, Kerber CW. Carotid-cavernous fistula following percutaneous retrogasserian procedures. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 1979;51(5):700–706. doi: 10.3171/jns.1979.51.5.0700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gökalp HZ, Kanpolat Y, Tümer B. Carotid-cavernous fistula following percutaneous trigeminal ganglion approach. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1980;82(4):269–272. doi: 10.1016/0303-8467(80)90019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lichtor T, Mullan JF. A 10-year follow-up review of percutaneous microcompression of the trigeminal ganglion. J Neurosurg. 1990;72(1):49–54. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.72.1.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lobato RD, Rivas JJ, Sarabia R, Lamas E. Percutaneous microcompression of the gasserian ganglion for trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg. 1990;72(4):546–553. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.72.4.0546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Revuelta R, Nathal E, Balderrama J, Tello A, Zenteno M. External carotid artery fistula due to microcompression of the gasserian ganglion for relief of trigeminal neuralgia. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1993;78(3):499–500. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.78.3.0499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kuether TA, O’Neill OR, Nesbit GM, Barnwell SL. Direct carotid cavernous fistula after trigeminal balloon microcompression gangliolysis: case report. Neurosurgery. 1996;39(4):853–856. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199610000-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kanpolat Y, Savas A, Bekar A, Berk C. Percutaneous controlled radiofrequency trigeminal rhizotomy for the treatment of idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia: 25-year experience with 1,600 patients. Neurosurgery. 2001;48(3):524–534. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200103000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Langford P, Holt ME, Danks RA. Cavernous sinus fistula following percutaneous balloon compression of the trigeminal ganglion. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2005;103(1):176–178. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.103.1.0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lesley WS. Endosurgical repair of an iatrogenic facial arteriovenous fistula due to percutaneous trigeminal balloon rhizotomy. J Neurosurg Sci. 2007;51(4):177–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Niu T, Kalia JS, Zaidat OO. Rare vascular complication of percutaneous balloon compression of trigeminal neuralgia treated endovascularly. J Neurointerv Surg. 2010;2(2):147–149. doi: 10.1136/jnis.2009.001164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li F, Ma Y, Zou J, et al. Endovascular treatment of rare vascular complications of percutaneous balloon compression for trigeminal neuralgia. Turk Neurosurg. 2016;26(2):215–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marshman LAG, Connor S, Polkey CE. Internal carotid-inferior petrosal sinus fistula complicating foramen ovale telemetry: successful treatment with detachable coils: case report and review. Neurosurgery. 2002;50(1):209–212. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200201000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sondheimer FK. Basal foramina and canals. In: Newton TH, Potts DG, editors. Radiology of the Skull and Brain. Mosby; 1971. pp. 287–308. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Elnashar A, Patel SK, Kurbanov A, Zvereva K, Keller JT, Grande AW. Comprehensive anatomy of the foramen ovale critical to percutaneous stereotactic radiofrequency rhizotomy: cadaveric study of dry skulls. J Neurosurg. 2019;132(5):1414–1422. doi: 10.3171/2019.1.JNS18899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim NY, Kim JY, Pyen JS, Whan K, Cho SM, Choi JW. Treatment of pseudoaneurysm of internal maxillary artery resulting from needle injury. Korean J Neurotrauma. 2019;15(2):176–181. doi: 10.13004/kjnt.2019.15.e33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pak S, Cha D, Valencia D, Askaroglu Y, Short J, Bouz P. Pseudoaneurysm as a late complication of gamma knife surgery for trigeminal neuralgia. Neurol India. 2018;66(2):514–515. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.227291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen-Gadol A. Percutaneous Rhizotomy—Placement Of Needle in the Foramen. Neurosurgical Atlas; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Golub B, Bordoni B. Neuroanatomy, pterygoid plexus. https://europepmc.org/article/nbk/nbk555896. Accessed March 1, 2023. [PubMed]