Abstract

Climate change affects cryosphere-fed rivers and alters seasonal sediment dynamics, affecting cyclical fluvial material supply and year-round water-food-energy provisions to downstream communities. Here, we demonstrate seasonal sediment-transport regime shifts from the 1960s to 2000s in four cryosphere-fed rivers characterized by glacial, nival, pluvial, and mixed regimes, respectively. Spring sees a shift toward pluvial-dominated sediment transport due to less snowmelt and more erosive rainfall. Summer is characterized by intensified glacier meltwater pulses and pluvial events that exceptionally increase sediment fluxes. Our study highlights that the increases in hydroclimatic extremes and cryosphere degradation lead to amplified variability in fluvial fluxes and higher summer sediment peaks, which can threaten downstream river infrastructure safety and ecosystems and worsen glacial/pluvial floods. We further offer a monthly-scale sediment-availability-transport model that can reproduce such regime shifts and thus help facilitate sustainable reservoir operation and river management in wider cryospheric regions under future climate and hydrological change.

Intensified glacier melt and discharge pulses remarkably increase summer sediment fluxes and threaten social-ecological systems.

INTRODUCTION

Climate change and cryosphere degradation have remarkably affected riverine water and sediment fluxes from polar and high-mountain regions, with varying effects seasonally and geographically (1–3). However, the responses of seasonal dynamics and regime shifts in sediment transport remain largely understudied, limited by the lack of long-term (e.g., decadal) and fine-scale (e.g., monthly to daily) hydrological records and the complexity of the underlying hydrogeomorphic processes. Shifts in the timing and magnitude of fluvial fluxes have crucial implications as they fundamentally alter the seasonal allocation of sediment, organic matter, nutrients, and pollutants, perturbing the seasonal biomass in receiving waters (4). These changes can affect year-round provision of water, food, and energy to populated and vulnerable mountain communities downstream (5, 6). Thus, disentangling the interplay between river regime shifts, climate change, and cryosphere degradation is essential to facilitate adaptation to an amplified hydrological imbalance in a warming future.

Ongoing deglaciation and increased hydrological and climatic extremes suggest that seasonal variability in river fluxes is being amplified (3, 7, 8), but only a few case studies have demonstrated explicitly the control of hydrological variability and warming-induced geomorphic changes on seasonal fluvial transport (9, 10). Changes in glacier-snow melting and precipitation regimes can affect the timing and magnitude of river discharges (11), with sediment fluxes usually assumed to change proportionately with water discharge (12). However, emerging thermally activated sediment sources and abrupt runoff surges (RSs, defined as sudden increases or pulses in the discharge) triggered by snow/ice melt and rainstorms imply exacerbated impacts of climatic and cryospheric changes on sediment transport. Accelerating glacier melt and permafrost thaw can elevate sediment availability nonlinearly by facilitating glacial/paraglacial/periglacial erosion and exposing unconsolidated sediment (1, 13, 14). Rainstorms in cold mountain regions, coincident with these readily available sediment sources, can disproportionately increase seasonal material fluxes and contribute to more frequent summer fluvial pulses (15, 16), with emerging trends already observed in cold regions such as the high Canadian Arctic and southern Andes (17, 18).

The seasonal pulse of river fluxes has manifested a range of ecological and social impacts in cryospheric regions by affecting the seasonality of biogeochemical fluxes and ecosystem productivity (19, 20), lifetime and efficiency of hydropower infrastructure (21), and seasonal freshwater-food supply (2, 18, 22). Glacier meltwater pulses and associated nutrient-rich sediment plumes control the timing of phytoplankton blooms in high-latitude coastal regions [e.g., south Greenland (20)], affecting seasonal marine productivity (4). Increased frequency and magnitude of sediment-laden flows from deglaciated mountains threaten hydropower systems by reservoir sedimentation and hydraulic turbine abrasion (21). Increased summer turbidity extremes from proglacial rivers, flanking urban centers, impair water quality and conflict with the demand for safe drinking water (2, 18). Despite these multifaceted socioecological impacts, changes in fluvial pulses in response to cryosphere degradation are poorly understood and predicted hitherto and are often underestimated because of the omission of increased sediment availability provided by changing glacial erosion and erosion from proglacial streams and permafrost disturbances (23).

Here, we leverage decadal monthly hydroclimatic observations from four distinct and pristine cryospheric basins in Tien Shan and the north Tibetan Plateau mountains, characterized as glacial, nival, pluvial, and mixed hydrological regimes (Fig. 1), to investigate regime shifts in suspended sediment transport from the 1960s to 2000s and decipher their linkage to climate change and cryosphere degradation. We assess systematically the seasonal changes in suspended sediment concentration (SSC) and identify the drivers of shifts in the sediment-transport regime by using the state-of-the-art snowmelt simulations (24) and basin-specific glacier melt simulations (25), as well as analyzing relevant climatic (temperature and rainfall) and hydrological (meltwater flow, total runoff, and runoff variability) variables. Further, we refine a sediment-availability-transport model that operates at a monthly scale (SAT-M model) (26) to simulate the shifted sediment-transport regime by considering the impacts of hydroclimatic variables on sediment availability. We demonstrate a weakened influence of snowmelt on sediment transport but find a direct control of glacial and pluvial processes on river sediment transport through intensifying RSs and flushing of available sediment sources. We highlight that a further amplified seasonal variability in river fluxes and a higher-magnitude sediment transport peak in summer have profound implications for river infrastructure, ecosystems, and floods. Our transferable SAT-M model framework can underpin the evaluation and prediction of river regime shifts under future climate change scenarios in wider cryospheric regions.

Fig. 1. Climate, discharge, and suspended sediment concentration of the studied cryospheric basins.

(A) Cryosphere coverage and decadal hydroclimatic change rates in the glacial basin (Xiehela at Tien Shan), nival basin (Qiaqiga at Tien Shan), pluvial basin (Yingluoxia at Qilian Mountain, north Tibetan Plateau), and mixed-regime basin (Qiemo at Kunlun Mountain, north Tibetan Plateau). Doughnut icons depict the rates of change of hydroclimatic variables, with temperature (red), rainfall (light blue), and relative percentage change rates of snowmelt (violet), RSs (light green), discharge (Q, dark blue) and suspended sediment concentration (SSC, brown), where clockwise denotes positive rates and counterclockwise denotes negative rates. See detailed observation records and the magnitude of trends in tables S1 and S2. (B to E) Monthly patterns of Q and SSC. The shaded area denotes SDs. Gray vertical bars denote spring and autumn.

RESULTS

Observed regime shifts in sediment transport

The overall warming and wetting climate since the 1960s has increased discharge by 3 to 28% per decade and SSC by 4 to 10% per decade in all studied river basins (Fig. 1A and table S2). The rates of change in SSC vary seasonally, associated with amplified monthly variability of SSC by 5 to 14% per decade (fig. S1). Seasonal regime shifts in sediment transport have been identified in response to changes in temperature-driven melting processes, rainfall peaking time and magnitude, seasonal transport capacity, and associated runoff variability (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Regime shifts in river suspended sediment transport driven by changing hydroclimatic conditions.

(A1 to D1) The percentage relative change rates of the hydroclimatic variables across seasons. Extreme rainfall days for each season are defined as days when daily rainfall exceeds the 95th percentile threshold. Change rates in winter are not included because the rivers are predominantly frozen (discharge and suspended sediment are near zero). The relative change rate of snowmelt is not shown for Yingluoxia because of insufficient long-term snowmelt data (1980–1987). See table S2 for detailed seasonal change rates of each variable. (A2 to D2) Changes in runoff variability in high-flow months. Monthly runoff variability is shown as dots with error bars (mean + SD). (A3 to D3) The monthly patterns and regime shifts of SSC. The shaded areas denote SDs. See Materials and Methods for definitions of runoff variability (Eq. 1) and RSs (Eq. 2). Gray vertical bars denote spring and autumn.

In spring, we observe a transition from a nival- to pluvial-dominated sediment-transport regime in the nival- and mixed-regime basins; such a regime shift is driven by progressively decreased snowmelt, increased rainstorms, and amplified RSs (Fig. 2). Spring snowmelt flow in the nival basin and mixed-regime basin decreased at a rate of 3 to 5% per decade, with snowmelt peak time shifting from April in the 1980s to March in the 2000s in the nival basin (fig. S2B and table S2). By contrast, more frequent extreme rainfall days together with the increased runoff and RSs have increased spring SSCs (Fig. 2, B and D). For the nival basin (Qiaqiga), snowmelt flow between April and June decreased significantly (8 to 31% per decade) from the 1980s to the 2000s (Fig. 2B1 and table S2). The concurrent increases of SSCs in April (31 ± 5%, mean ± SE) and June (54 ± 47%) were driven mainly by more than doubled magnitudes of runoff and its variability (Fig. 2B and table S3). For the mixed-regime basin (Qiemo), the more than doubled rainfall and extreme rainfall days have enhanced RSs and variability since the 1960s, significantly increasing spring SSC from 6.0 kg/m3 in the 1960s to 9.1 kg/m3 in the 2000s (Fig. 2D and table S3).

Summer SSCs have increased in all studied cryospheric basins at rates of 2 to 19% per decade, accompanied by increased runoff and amplified RSs and variability (Fig. 2 and table S2). In the glacial basin (Xiehela), increases in glacier meltwater and rainfall amplified RSs and variability in July by more than 50%, with a significant increase in summer SSC from 3.6 kg/m3 in the 1960s to 4.6 kg/m3 in the 1980s (Fig. 2A, fig. S3, and table S3). In the nival basin (Qiaqiga), the doubled summer SSC (P value of 0.1; table S3) from the 1980s to the 2000s can be attributed to the rapid increase in extreme rainfall days and amplified runoff variability (Fig. 2B). In the mixed-regime basin (Qiemo), glacier meltwater accounts for ~25% of the total runoff and has increased over the past decades (27). This increased glacier meltwater leads to increased runoff (6% per decade) and amplified RSs (6% per decade) and variability that collectively explain the significant increases in SSC from 9.8 kg/m3 in the 1960s to the 13.0 kg/m3 in the 2000s (Fig. 2D and table S3). The pluvial basin (Yingluoxia) experienced an insignificant increase of SSC from 0.9 kg/m3 in the 1960s to 1.1 kg/m3 in the 1980s, despite intensified summer rainstorms and increased runoff and its variability (Fig. 2C and table S3).

The autumn surge in SSCs is predominantly driven by pluvial events in the nival basin and mixed-regime basin. For instance, in the nival basin (Qiaqiga), the frequency of rainstorms has more than doubled, resulting in increases in RSs and triggering nearly threefold increases in autumn SSCs (P value of 0.1) from the 1980s to 2000s (Fig. 2B and table S3).

Theory and performance of the SAT-M model

In cryospheric basins, sediment availability can be magnified by rising temperatures, increased rainfall and meltwater, as well as amplified RSs, which can disrupt the sediment-discharge relationships. Here, we performed regression analysis and partial least-squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to assess the responses of SSC to hydroclimatic factors and measure their relative importance and direct/indirect effects on SSC. A detailed introduction of PLS-SEM and its outputs can be found in the Supplementary Materials (Text S1 and fig. S4). Notably, SSC increases linearly with the magnitude of RSs for all studied catchments, and the relationship between SSC and RSs is stronger than that between SSC and other factors (R2 from 0.59 to 0.90, first column in Fig. 3). This aligns with the results in PLS-SEM analysis that RSs display the most direct control on SSC in all studied catchments (fig. S4). Although both RSs and runoff variability capture the magnitude of runoff fluctuation and have a significant positive correlation, RSs represent more effectively the changes in sediment supply than runoff variability (first column in Fig. 3 and fig. S5), because the RS is defined to explicitly measure the magnitude of discharge pulses triggered by both rainstorms and intense glacier-snow melting (Eq. 2 in Materials and Methods). In addition, SSC increases exponentially with temperature, and such nonlinearity is more pronounced for the two glacier-affected basins (Xiehela and Qiemo). By contrast, in the pluvial basin (Yingluoxia), SSC is more sensitive to rainfall (R2 = 0.76) than to temperature. Such different impacts of climate factors are further corroborated by the values of relative importance in PLS-SEM analysis (fig. S4). For the nivally affected basins (Qiaqiga and Qiemo), spring SSCs respond sensitively to changes in snowmelt and scales as a power function of snowmelt flow (fig. S6).

Fig. 3. Best-fit relationships between SSC and hydroclimatic variables, and the performance of SAT-M and rating-curve method in reproducing seasonal sediment patterns and regime shifts.

(A1 to D1) Relationships between monthly SSC, monthly averaged temperature (T), monthly rainfall, and monthly RSs. See Materials and Methods for detailed calculations of these hydroclimatic variables. The solid black lines denote the best-fit relationships between SSC and key driving variables, fitted by least-squares estimation, with linear SSC-RS relationship and exponential relationships for SSC-T and SSC-rainfall. The shaded areas in (A1) to (D1) denote the 95% confidence intervals of the corresponding fitting curves. (A2 to D2) Hysteresis between monthly SSC and discharge (Q). (A3 to D3) The reproduced sediment regime shifts yielded by the SAT-M model (solid lines) and observed sediment regime shifts (dashed lines). The shaded areas in (A2) to (D2) and (A3) to (D3) are the estimated uncertainty (SE) in SAT-M simulations from 10-time cross-validation (see Materials and Methods). Gray vertical bars in A3 to D3 denote spring and autumn.

To reproduce the dynamic sediment transport in cryosphere-fed rivers, we built a monthly-scale sediment-availability-transport model (SAT-M model, Eq. 5 in Materials and Methods), which incorporates basin temperature, rainfall, snowmelt, and RSs to capture the time-variant sediment supply. In the SAT-M model, the basin temperature encapsulates the processes of thermally activated sediment sources from ice-rich permafrost thaw and the retreat of glaciers and thermally enhanced sediment connectivity by developing erosional gullies in unstable hillslopes (14, 26). Rainfall represents the pluvially activated sediment sources, including rainstorm-triggered mass movements from unstable slopes and reactivated proglacial sediment storage (28, 29). RSs capture the enhanced stream power and channel erosion and resuspend previously deposited sediment during meltwater/pluvial pulses and flash floods (30, 31). Because of the integration of these sediment-transport mechanisms, the SAT-M model accurately replicates the clockwise sediment-discharge hysteresis with identical seasonal patterns as observed in studied basins (middle column in Fig. 3). More specifically, warm temperatures, intense rainfall, and frequent discharge pulses indicate active erosion, which explains more readily available sediment in spring/summer (transport-limited phase; middle column in Fig. 3 and fig. S7). Conversely, the cold and dry weather condition, together with the recession of meltwater and discharge, reduces thermal/pluvial erosion, leading to the exhaustion of sediment sources toward the end of the melt season (supply-limited phase). In addition, the SAT-M model effectively captures the decadal-scale regime shifts in SSC (third column in Fig. 3) resulting from the increasing control of pluvial processes in spring and the enhanced RSs in summer.

The primary factors controlling sediment supply and transport mechanisms differ among different cryospheric basins. For example, runoff has the greatest relative importance at the glacial and pluvial basins; RSs show the largest relative importance at the nival basin; temperature shows the largest relative importance at the mixed-regime basin (fig. S4). To enhance the model transferability across the different hydrological regimes, the SAT-M model enables the objective selection of the most effective variables for the best fit (see Materials and Methods and table S4), and this flexibility enables the SAT-M model to perform satisfactorily in all studied glacial, nival, and pluvial basins [with a Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency coefficient (NSE) exceeding 0.9]. Compared with the conventional rating-curve method (RC), the SAT-M model exhibits a 0.1 to 0.3 increase in R2 and NSEs and a 2 to 4% decline in relative errors (REs) (table S4). The reliability of the SAT-M model is further demonstrated by its robust performance during both calibration and validation periods, as evidenced by 10-fold cross-validation across all studied basins (tables S5 and S6). In contrast, the performance of the conventional rating-curve method heavily depends on the calibration period, resulting in poor performance during the validation period. The simulation of SSC using the rating curve seriously distorts the pattern of sediment regime shift (fig. S8), which confirms the significant influence of temperature, rainfall, snowmelt, and RSs on sediment transport in cryospheric basins.

DISCUSSION

Toward pluvial-dominated sediment transport in spring

In spring, the combination of advanced snowmelt peak, reduced snowpack, and increased rainfall leads to a growing dependence on pluvial processes for sediment transport in nivally affected catchments (Qiaqiga and Qiemo). Snowmelt erosion and associated freeze-thaw processes in early spring can loosen and destabilize landscapes progressively and make them susceptible to subsequent sediment flushing during rainstorms and surges in runoff (29, 32) (Fig. 4). At Qiaqiga, the earlier onset of snow melting in March in the 2000s primed readily available erodible sediment (fig. S2B). This sediment was not exported immediately because the discharge needed to mobilize them was at first limited by low temperatures (e.g., below 0°C), but they were mainly mobilized and transported by subsequent pluvial pulses, giving rise to a jump in SSC in April (Fig. 2B). Reduced snow cover also enhances rainfall erosivity and facilitates pluvial sediment transport (10), until increased vegetation cover shields the erodible landscapes and decreases soil erodibility in late spring (33).

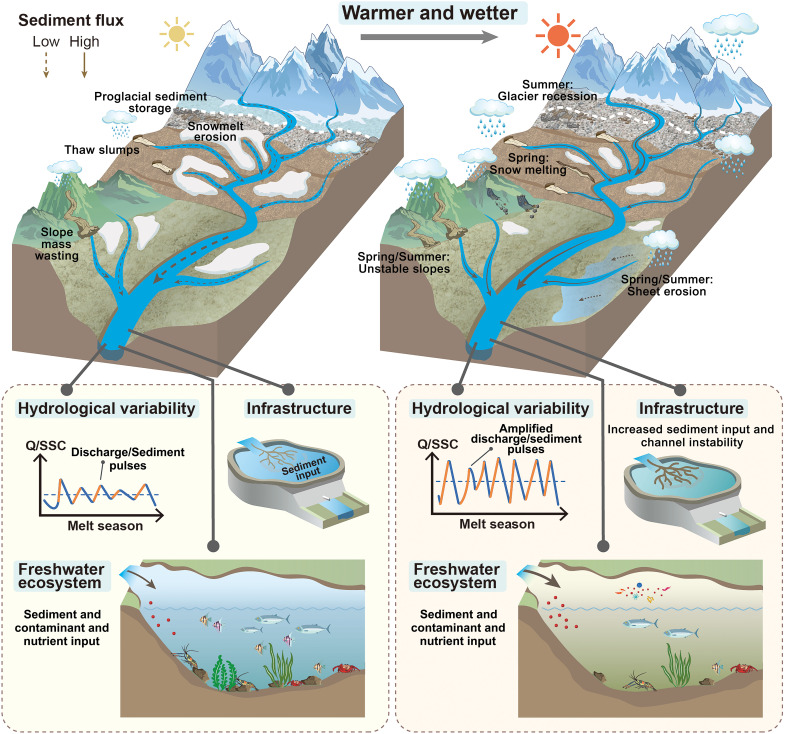

Fig. 4. Increased readily transportable sediment sources, amplified hydrological variability, and associated social-ecological impacts in a warmer and wetter climate.

Hydrogeomorphic changes in response to a warming and wetting climate are illustrated in the upper panel. Changes in hydrological variability and the impacts of sediment transport on infrastructure (e.g., dams, reservoirs, and hydropower facilities) and freshwater ecosystems are illustrated in the lower panel.

Such a transient spring erosion window can be satisfactorily reproduced by the SAT-M model simulations via incorporating temperature-dependent erosion and vegetation-constrained effective snowmelt, but it is largely underestimated by the model without snowmelt input (Fig. 3, B and D, and fig. S6). Moreover, the amplified SSC peaks in the 2000s are captured by enhanced pluvial pulses, despite the decreased snowmelt (Fig. 3, B and D).

Enhanced summer sediment transport by increased discharge pulses and sediment supply

We observed markedly increased summer SSC and sediment fluxes in the 1980s and 2000s compared to the 1960s in all studied basins. Such a regime shift and the increased proportion of sediment transport in summer are more detectable in glacial and nival catchments that are transitioning toward the pluvial regime (Fig. 2 and fig. S9). Summer SSCs are increased by a combination of multiple hydrogeomorphic drivers, including increased readily transportable sediment sources from retreating glaciers and thawing permafrost and enhanced sediment transport efficiency by rainstorms and discharge pulses (Fig. 4). The overall increased sediment supply suggests sensitive landscape responses to intensified meltwater and pluvial pulses in cryospheric regions (34).

Warming-intensified glacier melting not only has increased the summer discharge, but more importantly, has amplified runoff variability and meltwater pulses (9, 35). Meltwater pulses, together with rainstorm-triggered pluvial events, can enhance sediment connectivity by developing gullies/channels that effectively evacuate sediment from subglacial and proglacial storage and unstable valley slopes that fail after being debuttressed by rapid glacier retreat (1). Glaciers in the central Tien Shan experienced their maximum rate of mass loss during the 1980s (36) that led to a 25% increase in August discharge at Xiehela as compared to the 1960s (fig. S2A). The ~50% increase in SSC in August indicates the elevated sediment supply and disproportionate sediment transport by increased discharge pulses (Fig. 2A). In the 2000s, rainstorm-triggered discharge pulses were increasingly important and responsible predominately for increased SSC in July (Fig. 2A and fig. S2A), despite the decelerated glacial mass loss (36). At the nivally affected Qiaqiga, increased rainstorms and pluvial pulses enhanced summer sediment transport and, more interestingly, shifted the season of peak sediment transport from spring in the 1980s to summer in the 2000s (Fig. 2B and fig. S2B). At the pluvial-dominated Yingluoxia, permafrost thaw has increased thaw slumps in the upstream reaches since the 1960s (37), creating additional sediment sources. Increased rainstorms and associated RSs then transport this thermally activated sediment downstream, eventually increasing the summer SSC (Fig. 2C).

Broad social-ecological implications

The amplified hydrological variability and climate-driven shifts in seasonal sediment-transport regimes observed herein have fundamental implications for river morphology, floods, and freshwater ecosystems downstream, leading to additional stresses on the water-food-energy system.

Amplified runoff variability and summer sediment supply can reshape river morphology and thus aquatic habitats, particularly during high-magnitude RSs and flood events. In cold regions, river widening and bank collapses have become more frequent in recent decades in response to increased stream power and sediment supply (14, 38). The glacier-fed braided river systems in the Himalaya, European Alps, Alaska, and western United States have also been found to be more dynamic and geomorphically unstable when driven primarily by increased meltwater and rainstorm-related sediment transport (38–41). Despite much fewer observations of bedload, intensified discharge pulses and activated glacierized sediment sources also suggest a higher bedload flux (42), further magnifying river channel instability and migration. Such reduced river stability can severely affect human populations that depend heavily on these rivers and fisheries such as salmonid habitats.

Besides degrading water quality, increases in sediment-driven river turbidity can threaten river biotic conditions by blocking sunlight from reaching the streambed, limiting respiration and deteriorating feeding conditions of benthic macroinvertebrates and fishes, thereby decreasing habitat availability (43, 44), with severe ecological consequences (Fig. 4 and fig. S10). Elevated turbidity can disturb habitats of macroinvertebrates and fishes by filling interstitial spaces between pebble and cobbles on the riverbed, thereby reducing the flow of oxygenated water through bed sediment that is essential to the survival of their eggs (45). In the Tibetan Plateau, increased suspended sediment has been observed to decrease the zooplankton species richness in thermokarst lakes (46) and bury and smother fish eggs of Schizopygopsis microcephalus (47). These ecosystem effects of greater suspended-sediment loads can propagate extensively in the aquatic food web and further, affecting terrestrial organisms that feed on fish and aquatic invertebrates. In the high Arctic Canada and Alaska, increases in sediment evacuation and sediment pulses are reducing macroinvertebrate abundance driving macroinvertebrate drift and broadly affecting stream food webs (41, 44, 48), causing substantial ecosystem changes. Together with direct temperature- and hydrology-driven aquatic ecosystem changes as climate warms (22, 43, 49), these ecological consequences of higher sediment loads could limit human access to food sources linked to the river, as is already occurring in some North American communities (50).

The substantially increased proportion of sediment flux transported in summer (Fig. 2 and fig. S9) can jeopardize downstream hydropower and irrigation infrastructure by causing rapid reservoir sedimentation and thus reducing effective storage capacity (Fig. 4). Across Himalaya and European mountains, many thousands of dams and reservoirs are being planned or under construction at locations closer to the headwaters and glaciers (21, 51). Our results highlight that the design and operation of these dams and reservoirs should be forward looking. Their operation schemes should consider fully the amplified hydrological variability and shifts in sediment regime driven by climate change, especially changes in the timing and magnitudes of annual sediment peaks. The designed reservoir storage capacity and sediment flushing capabilities of the reservoir should be able to tackle future increases in seasonal sediment inputs.

Our SAT-M model can satisfactorily reproduce climate-driven shifts in seasonal sediment transport and increased summer SSC and amplified SSC peaks by incorporating RSs and time-varying sediment supply (Fig. 3). Given anticipated increases in flooding risks and increased variability in precipitation and runoff in cold mountain regions (2, 7, 52), the SAT-M model provides a promising simulation tool to assist in predicting sediment fluxes and peaks, optimizing sediment management of dams and reservoirs, and mitigating their downstream impacts under future climate change scenarios. By contrast, traditional sediment rating curves fail to reproduce altered seasonal patterns in sediment transport and largely underestimate the summer SSC (fig. S8). For example, summer SSC is underestimated significantly by 23% at the mixed-regime basin (Fig. 3D2 and table S4) which could misinform sediment flushing schemes and underestimate the designed reservoir capacity of planned reservoirs, likely shortening their life spans.

Summary

Our analysis demonstrates the markedly amplified hydrological variability and regime shifts in suspended sediment transport in glacial-, nival-, and pluvial-fed cryospheric basins driven by accelerated glacier melting and enhanced pluvial processes. Spring sediment fluxes are shifting from a nival- toward a pluvial-dominated regime because of less snowmelt and more erosive rainfall. Summer sediment fluxes have substantially increased because of disproportionately higher sediment transport yielded by greater glacier meltwater pulses and pluvial pulses. Such amplified hydrological variability and shifted sediment-transport regimes in cryosphere-fed rivers add additional stresses to downstream hydropower and irrigation infrastructure and ecosystems and exacerbate the damage caused by floods.

Similar shifts in sediment-transport regime are also emerging in permafrost regions of the High Arctic (3, 53) and glacierized regions of the European Alps (10) in response to intensified summer rainfall and amplified discharge fluctuations produced by glacier melting. These cases, together with our findings in Asia’s cryosphere-fed rivers, unambiguously highlight the sensitive nature of sediment transport to RSs resulting from warming-induced glacier and permafrost erosion during the early stages of deglaciation. This sensitivity of sediment transport to RSs suggests that more frequent extreme sediment events and sediment-laden floods can be expected from cryosphere degradation, particularly in the Arctic, European Alps, and high mountains of Asia, with increasing rainstorms anticipated in the future (54–56).

The SAT-M model presented herein effectively reproduces the shifted sediment-transport regime by constraining climate-driven changes in sediment supply and RSs in cryosphere-fed rivers. It provides more accurate estimates of seasonal sediment flux compared to traditional sediment rating-curve methods. As climate change and cryosphere degradation continue, hydrological variability will further increase and sediment transport will be controlled more by pluvial processes. Our SAT-M model offers a methodology framework to simulate sediment transport in response to rapid hydroclimatic changes and can be freely applied in wider cryospheric regions by selecting basin-specific drivers. This model thus has great potential to improve synergies between sediment connectivity, hydropower generation, and irrigation efficiency (e.g., in the strategically important Southwestern Rivers of the Tibetan Plateau). This will consequently help sustain sediment-related nutrients for downstream agricultural lands and facilitate the creation of hydropower and irrigation systems that are more resilient to climate change in the world’s vulnerable high-mountain areas.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Hydroclimatic data

Discharge and SSC observations from the 1960s to 2000s were collected at four hydrological stations, namely, Xiehela (glacial regime), Qiaqiga (nival regime), Yingluoxia (pluvial regime), and Qiemo (mixed regime). Discharge and suspended sediment load data are provided in the Chinese Hydrological Data Yearbook, with detailed observation periods and gap years at each station recorded in table S1 and fig. S1. Daily water level (stage) is recorded with multiple observations in a flood event. Water velocities are measured by a propeller blade current meter or acoustic Doppler current profiler at the cross section to calculate discharge and calibrate stage-discharge relationships across a wide-range of discharges. Daily mean discharge (cubic meter per second) is converted from the frequently updated site-specific stage-discharge relationship constrained by historical observations. Daily SSC (kilogram per cubic meter) is obtained by laboratory measurement of water samples collected by a depth-integrating sampler coupled with cross-sectional sampling. Hydrological variables are observed once per day in the low-flow season but more frequently (e.g., four times a day) during flood events to capture temporal variations. All the hydro measurements follow the national standards issued by the Ministry of Water Resources, China, with quality control before data release and uncertainty of sediment load observations controlled within 10%. Detailed strategies for discharge and sediment measurements can be found in (57). Although the uncertainty in SSC measuring can disturb long-term trend analysis and is a long-lasting challenge in field sediment observations, this can be mitigated by collecting water samples regularly and using consistent observation methods and instruments. To our knowledge, there are no reported changes in locations and methods for collecting water samples and measurement strategies for suspended sediment throughout the investigation period at our studied sites. In addition, we used statistical tests and presented the variability of observations to identify significant changes and trends of SSC, ensuring the reliability of our results.

Daily air temperature (degree Celsius) and daily precipitation (millimeter) data from the 1960s to 2000s were collected from eight meteorological stations distributed within or nearby to the river basins (Fig. 1 and table S1) and are available from the National Meteorological Information Center, China Meteorological Administration.

Daily snowmelt (millimeter) data from the 1980s to 2000s were derived from simulations driven by a state-of-the-art temperature index snowmelt model at a spatial resolution of 0.05° and display a good performance (24). The normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) was derived from the product of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Global Inventory Monitoring and Modeling System (GIMMS) (58), with a 15-day temporal resolution and spatial resolution of 0.083°, available at http://poles.tpdc.ac.cn/en/data/9775f2b4-7370-4e5e-a537-3482c9a83d88/.

The periods of four seasons are generally defined as spring between March and May, summer between June and August, autumn between September and November, and winter between December and February. Notably, the length of spring at Qiaqiga is adjusted as March to June; the lengths of autumn at Qiaqiga and Yingluoxia are adjusted as September to October because of their distinct climatic and hydrological characteristics.

Calculations of runoff variability, RSs, and effective snowmelt

Monthly runoff variability (RV, cubic meter per second, e.g., the SD) is used to measure the magnitude of runoff fluctuation within a month (Eq. 1). A greater variability represents a larger fluctuation and indicates more frequent discharge pulses

| (1) |

where Qi is the daily mean discharge at day i, n is the number of days within month m, and μm is the average discharge in month m.

To explicitly quantify the monthly magnitude of discharge pulses, the monthly RSs (cubic meter per second) are defined as the sum of daily discharge increases within a month (Eq. 2)

| (2) |

where RSi is the runoff surge at a given day i and RSm is the sum of daily runoff surges in month m.

Effective snowmelt is proposed in this study to incorporate the effect of vegetation cover on snowmelt erosion to some extent, calculated as division of snowmelt by the NDVI (Eq. 3). Specifically, less vegetation cover and therefore more exposed erodible landscapes can enhance snowmelt erosion in the beginning of the spring (10), expressed by increasing effective snowmelt

| (3) |

where SMi is the snowmelt flow in a month m; NDVIm is the average NDVI in month m; max(1/NDVIm) denotes the maximum of (1/NDVIm) within a hydrological year.

Sediment-availability-transport model at a monthly scale

A traditional rating curve reflects the control of discharge on suspended sediment transport (Eq. 4). However, suspended sediment transport in cryosphere-fed rivers is also governed by temperature-dependent erosion processes in glacierized and permafrost landscapes, snowmelt erosion, rainstorm-triggered mass movements from unstable hillslopes (e.g., thermokarst slopes and glacially debuttressed slopes), and enhanced channel erosion by discharge pulses (1, 28, 30) as we have previously demonstrated (Figs. 3 and 4). Such additional hydroclimatic controls, together with the sediment hysteresis effect, make rating curves ineffective in cryosphere-fed rivers

| (4) |

where SSCm and Qm are the average suspended sediment concentration (kilogram per cubic meter) and discharge (cubic meter per second), respectively in month m, and a and b are the fitting parameters. Parameters are fitted by the Levenberg-Marquardt (L-M) algorithm, which is a robust nonlinear least-squares fitting in most cases (59).

To simulate seasonal sediment transport and regime shifts in cryosphere-fed rivers affected by climate change, we developed the SAT-M model. This model incorporates the time-variant sediment availability and transport capacity regulated by thermal, fluvial, and pluvial processes and is expressed by modifying the rating curve using Eq. 5. The SAT-M model is updated from a daily-scale SAT model (26) by (i) incorporating rainfall-triggered pluvial processes, (ii) adding snowmelt processes and their interaction with vegetation cover, and (iii) simplifying model parameters and enabling users to turn on/off processes (variables) that are relevant/irrelevant for a specific study area

| (5) |

where Tm is the average monthly temperature (degree Celsius); Rm is the total monthly rainfall (millimeter); RSm is the monthly runoff surges (cubic meter per second); SMm is the monthly amount of effective snowmelt (millimeter) constrained by NDVI as Eq. 3; an and bn are the fitting parameters by the L-M algorithm.

The SAT-M model framework consists of three parts: (i) fluvial erosion processes represented by total runoff, (ii) snowmelt erosion processes represented by effective snowmelt flow, and (iii) thermal and pluvial processes related to sediment supply and erodibility encapsulated by monthly average temperature, rainfall, and RSs. While total runoff and snowmelt flow overlap, the SAT-M model incorporates snowmelt separately as it is an ephemeral and predominant erosion process in spring especially in nivally affected basins. Disabling snowmelt processes leads to underestimated spring SSCs in the nivally affected Qiaqiga and Qiemo sites (fig. S6). Because temperature, rainfall, and RSs regulate sediment supply and erodibility, they are added together in the third part of the SAT-M model. The linear effect of river surges and exponential effects of temperature and rainfall on SSC can be identified by the best-fit relationships between SSC and these variables (Fig. 3); these relationships are also aligned with observations in other glacierized and permafrost basins (26, 60–62). Greater sediment supply and erodibility increase sediment mobilization and transport at the same discharge level (26); such effects are expressed by the third term in Eq. 5 multiplied by the sum of the discharge-related fluvial term (first term, Eq. 5) and snowmelt term (second term, Eq. 5).

The concept of turning on/off relevant/irrelevant processes and enabling self-selection of the best-fit variables enhances the flexibility and portability of the SAT-M model in two aspects: (i) the model function and input variables can be configured according to basin-specific characteristics and sediment transport mechanisms, and (ii) this selection can reduce the number of required input data and parameters by switching off irrelevant processes. For example, in the pluvial Yingluoxia catchment, sediment transport is dominated by rainstorm-triggered pluvial processes with ineffective and negligible controls exerted by basin temperature and snowmelt; thus a2 in the second term and a3 in the third term of Eq. 5 are calibrated as zero (e.g., the snowmelt process and thermal process are switched off). For a specific basin, if none of these hydroclimatic variables (temperature, rainfall, and RSs) are relevant to sediment transport or not available, all corresponding parameters would be set as zero and the SAT-M model would revert to a conventional rating curve. Continuous cryosphere degradation will alter the sediment transport behavior of rivers and likely drive changes in model parameters, although the magnitude of these changes will depend on the sensitivity of the watershed to those environmental changes and the rates of landscape stabilization (1). In a predictive mode, model parameters may need to be adjusted according to alterations in basin’s physical conditions and river processes. The flexibility of the SAT-M model and the clear inclusion of physical processes in its model framework suggest its potential to be adapted to future climate scenarios.

The SAT-M model is a sediment transport model designed for cryosphere-fed rivers, incorporating multiple erosion and sediment transport processes present in glacial, nival, pluvial, and mixed-regimes.

Model evaluation and cross-validation

The accuracy of simulations from the SAT-M model and the rating-curve method and the magnitude of residuals are evaluated by the NSE (−∞ to 1), the RE, and the coefficient of determination (R2, 0 to 1). Notably, RE is defined as the sum of the difference between simulated and observed SSC divided by the sum of SSC observations. A model with NSE and R2 over 0.5 and RE less than 25% is typically considered to be an accurate model (26, 63).

The model robustness and uncertainty in simulations of the SAT-M model and the rating-curve method are determined by 10-time cross-validation. Here, to ensure sufficient data to calibrate the parameters, we split the dataset into two subsets for each time of cross-validation due to limited observations. For each cross-validation, the calibration period is a randomly selected 10 years, while the validation period is the remaining years. The details in calculation can be found in (64). Notably, the model uncertainty (Eq. 6) is calculated as the SE of the simulations from the 10-time cross-validation and the original simulation

| (6) |

where Um is the uncertainty of the estimated SSC in the month m; k is the number of model runs and is equal to 11 in this study; model runs herein include both the simulations from 10-time cross-validation and the original simulation where all data are used; SSCsim,m,i is the SSC simulation from the ith model run in the month m; is the mean of the SSC simulations from all model runs in the month m.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Duethmann and T. Bolch for providing hydrological simulations at the Xiehela station. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. government.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 92047303 and 51721006), Singapore Ministry of Education (grant no. A-0003626-00-00), National University of Singapore (NUS President’s Graduate Fellowship), and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and Cuomo Foundation.

Author contributions: T.Z. analyzed the data. T.Z. and D.L. prepared the manuscript, with contributions from all authors. All authors contributed to the figure design and the revision of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Precipitation and air temperature data were derived from China’s surface climate data daily value dataset (V3.0) and can be retrieved from the National Meteorological Information Center (http://data.cma.cn/en) or the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/en/data/52c77e9c-df4a-4e27-8e97-d363fdfce10a/). Daily snowmelt data were obtained from the published dataset (24) and can be downloaded from https://zenodo.org/record/4715786#.Yy6a0DTP1PY. NDVI data were derived from the product of NOAA GIMMS (58), available at http://poles.tpdc.ac.cn/en/data/9775f2b4-7370-4e5e-a537-3482c9a83d88/. Discharge and SSC observations can be accessed from the International Research and Training Center on Erosion and Sedimentation (http://en.irtces.org/irtces/index.htm), and the hard copy of Chinese Hydrological Data Yearbook can be found in the National Library of China. The data of the other driving factors and simulation outputs are available at https://zenodo.org/record/8139758.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Text S1

Figs. S1 to S10

Tables S1 to S6

References

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Zhang T., Li D., East A. E., Walling D. E., Lane S., Overeem I., Beylich A. A., Koppes M., Lu X., Warming-driven erosion and sediment transport in cold regions. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 832–851 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huss M., Bookhagen B., Huggel C., Jacobsen D., Bradley R. S., Clague J. J., Vuille M., Buytaert W., Cayan D. R., Greenwood G., Mark B. G., Milner A. M., Weingartner R., Winder M., Toward mountains without permanent snow and ice. Earths Future 5, 418–435 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beel C. R., Heslop J. K., Orwin J. F., Pope M. A., Schevers A. J., Hung J. K. Y., Lafreniere M. J., Lamoureux S. F., Emerging dominance of summer rainfall driving High Arctic terrestrial-aquatic connectivity. Nat. Commun. 12, 1448 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hopwood M. J., Carroll D., Browning T. J., Meire L., Mortensen J., Krisch S., Achterberg E. P., Non-linear response of summertime marine productivity to increased meltwater discharge around Greenland. Nat. Commun. 9, 3256 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Immerzeel W. W., Lutz A. F., Andrade M., Bahl A., Biemans H., Bolch T., Hyde S., Brumby S., Davies B. J., Elmore A. C., Emmer A., Feng M., Fernandez A., Haritashya U., Kargel J. S., Koppes M., Kraaijenbrink P. D. A., Kulkarni A. V., Mayewski P. A., Nepal S., Pacheco P., Painter T. H., Pellicciotti F., Rajaram H., Rupper S., Sinisalo A., Shrestha A. B., Viviroli D., Wada Y., Xiao C., Yao T., Baillie J. E. M., Importance and vulnerability of the world's water towers. Nature 577, 364–369 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viviroli D., Kummu M., Meybeck M., Kallio M., Wada Y., Increasing dependence of lowland populations on mountain water resources. Nat. Sustain. 3, 917–928 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shukla T., Sen I. S., Preparing for floods on the Third Pole. Science 372, 232–234 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Min S. K., Zhang X., Zwiers F. W., Hegerl G. C., Human contribution to more-intense precipitation extremes. Nature 470, 378–381 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lane S. N., Nienow P. W., Decadal-Scale Climate Forcing of Alpine Glacial Hydrological Systems. Water Resour. Res. 55, 2478–2492 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costa A., Molnar P., Stutenbecker L., Bakker M., Silva T. A., Schlunegger F., Lane S. N., Loizeau J.-L., Girardclos S., Temperature signal in suspended sediment export from an Alpine catchment. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 22, 509–528 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khanal S., Lutz A. F., Kraaijenbrink P. D. A., van den Hurk B., Yao T., Immerzeel W. W., Variable 21st Century Climate Change Response for Rivers in High Mountain Asia at Seasonal to Decadal Time Scales. Water Resour. Res. 57, e2020WR029266 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asselman N. E. M., Fitting and interpretation of sediment rating curves. J. Hydrol. 234, 228–248 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewkowicz A. G., Way R. G., Extremes of summer climate trigger thousands of thermokarst landslides in a High Arctic environment. Nat. Commun. 10, 1329 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li D., Overeem I., Kettner A. J., Zhou Y., Lu X., Air Temperature Regulates Erodible Landscape, Water, and Sediment Fluxes in the Permafrost-Dominated Catchment on the Tibetan Plateau. Water Resour. Res. 57, e2020WR028193 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kokelj S. V., Kokoszka J., van der Sluijs J., Rudy A. C. A., Tunnicliffe J., Shakil S., Tank S. E., Zolkos S., Thaw-driven mass wasting couples slopes with downstream systems, and effects propagate through Arctic drainage networks. Cryosphere 15, 3059–3081 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li D., Li Z., Zhou Y., Lu X., Substantial Increases in the Water and Sediment Fluxes in the Headwater Region of the Tibetan Plateau in Response to Global Warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL087745 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beel C. R., Lamoureux S. F., Orwin J. F., Fluvial Response to a Period of Hydrometeorological Change and Landscape Disturbance in the Canadian High Arctic. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 10,446-10,455 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vergara I., Garreaud R., Ayala Á., Sharp Increase of Extreme Turbidity Events Due To Deglaciation in the Subtropical Andes. J. Geophys. Res. Earth 127, (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terhaar J., Lauerwald R., Regnier P., Gruber N., Bopp L., Around one third of current Arctic Ocean primary production sustained by rivers and coastal erosion. Nat. Commun. 12, 169 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arrigo K. R., van Dijken G. L., Castelao R. M., Luo H., Rennermalm Å. K., Tedesco M., Mote T. L., Oliver H., Yager P. L., Melting glaciers stimulate large summer phytoplankton blooms in southwest Greenland waters. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 6278–6285 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li D., Lu X., Walling D. E., Zhang T., Steiner J. F., Wasson R. J., Harrison S., Nepal S., Nie Y., Immerzeel W. W., Shugar D. H., Koppes M., Lane S., Zeng Z., Sun X., Yegorov A., Bolch T., High Mountain Asia hydropower systems threatened by climate-driven landscape instability. Nat. Geosci. 15, 520–530 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bellmore J. R., Fellman J. B., Hood E., Dunkle M. R., Edwards R. T., A melting cryosphere constrains fish growth by synchronizing the seasonal phenology of river food webs. Glob. Chang. Biol. 28, 4807–4818 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferguson R. I., River Loads Underestimated by Rating Curves. Water Resour. Res. 22, 74–76 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kraaijenbrink P. D. A., Stigter E. E., Yao T., Immerzeel W. W., Climate change decisive for Asia’s snow meltwater supply. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 591–597 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duethmann D., Bolch T., Farinotti D., Kriegel D., Vorogushyn S., Merz B., Pieczonka T., Jiang T., Su B., Güntner A., Attribution of streamflow trends in snow and glacier melt-dominated catchments of the Tarim River, Central Asia. Water Resour. Res. 51, 4727–4750 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang T., Li D., Kettner A. J., Zhou Y., Lu X., Constraining Dynamic Sediment-Discharge Relationships in Cold Environments: The Sediment-Availability-Transport (SAT) Model. Water Resour. Res. 57, e2021WR030690 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fang G., Yang J., Chen Y., Li Z., Ji H., De Maeyer P., How Hydrologic Processes Differ Spatially in a Large Basin: Multisite and Multiobjective Modeling in the Tarim River Basin. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 123, 7098–7113 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiarle M., Geertsema M., Mortara G., Clague J. J., Relations between climate change and mass movement: Perspectives from the Canadian Cordillera and the European Alps. Glob. Planet. Change 202, 103499 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inamdar S., Johnson E., Rowland R., Warner D., Walter R., Merritts D., Freeze–thaw processes and intense rainfall: The one-two punch for high sediment and nutrient loads from mid-Atlantic watersheds. Biogeochemistry 141, 333–349 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hensley R., Singley J., Gooseff M., Pulses within pulses: Concentration-discharge relationships across temporal scales in a snowmelt-dominated Rocky Mountain catchment. Hydrol. Process. 36, e14700 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dean D. J., Topping D. J., Schmidt J. C., Griffiths R. E., Sabol T. A., Sediment supply versus local hydraulic controls on sediment transport and storage in a river with large sediment loads. J. Geophys. Res. Earth 121, 82–110 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iida T., Kajihara A., Okubo H., Okajima K., Effect of seasonal snow cover on suspended sediment runoff in a mountainous catchment. J. Hydrol. 428-429, 116–128 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu Y., Ouyang W., Hao Z., Yang B., Wang L., Snowmelt water drives higher soil erosion than rainfall water in a mid-high latitude upland watershed. J. Hydrol. 556, 438–448 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 34.East A. E., Stevens A. W., Ritchie A. C., Barnard P. L., Campbell-Swarzenski P., Collins B. D., Conaway C. H., A regime shift in sediment export from a coastal watershed during a record wet winter, California: Implications for landscape response to hydroclimatic extremes. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 43, 2562–2577 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slater T., Shepherd A., McMillan M., Leeson A., Gilbert L., Muir A., Munneke P. K., Noel B., Fettweis X., van den Broeke M., Briggs K., Increased variability in Greenland Ice Sheet runoff from satellite observations. Nat. Commun. 12, 6069 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhattacharya A., Bolch T., Mukherjee K., King O., Menounos B., Kapitsa V., Neckel N., Yang W., Yao T., High Mountain Asian glacier response to climate revealed by multi-temporal satellite observations since the 1960s. Nat. Commun. 12, 4133 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mu C., Shang J., Zhang T., Fan C., Wang S., Peng X., Zhong W., Zhang F., Mu M., Jia L., Acceleration of thaw slump during 1997–2017 in the Qilian Mountains of the northern Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. Landslides 17, 1051–1062 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feng D., Gleason C. J., Yang X., Allen G. H., Pavelsky T. M., How Have Global River Widths Changed Over Time? Water Resour. Res. 58, e2021WR031712 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.East A. E., Jenkins K. J., Happe P. J., Bountry J. A., Beechie T. J., Mastin M. C., Sankey J. B., Randle T. J., Channel-planform evolution in four rivers of Olympic National Park, Washington, U.S.A.: The roles of physical drivers and trophic cascades. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 42, 1011–1032 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bakker M., Antoniazza G., Odermatt E., Lane S. N., Morphological Response of an Alpine Braided Reach to Sediment-Laden Flow Events. J. Geophys. Res. Earth 124, 1310–1328 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Milner A. M., Robertson A. L., McDermott M. J., Klaar M. J., Brown L. E., Major flood disturbance alters river ecosystem evolution. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 137–141 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Micheletti N., Lane S. N., Water yield and sediment export in small, partially glaciated Alpine watersheds in a warming climate. Water Resour. Res. 52, 4924–4943 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Milner A. M., Khamis K., Battin T. J., Brittain J. E., Barrand N. E., Füreder L., Cauvy-Fraunié S., Gíslason G. M., Jacobsen D., Hannah D. M., Hodson A. J., Hood E., Lencioni V., Ólafsson J. S., Robinson C. T., Tranter M., Brown L. E., Glacier shrinkage driving global changes in downstream systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 9770–9778 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chin K. S., Lento J., Culp J. M., Lacelle D., Kokelj S. V., Permafrost thaw and intense thermokarst activity decreases abundance of stream benthic macroinvertebrates. Glob. Chang. Biol. 22, 2715–2728 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greig S. M., Sear D. A., Carling P. A., The impact of fine sediment accumulation on the survival of incubating salmon progeny: Implications for sediment management. Sci. Total Environ. 344, 241–258 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ren Z., Jia X., Zhang Y., Ma K., Zhang C., Li X., Biogeography and environmental drivers of zooplankton communities in permafrost-affected lakes on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 38, e02191 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao L., Li W., Lin L., Guo W., Zhao W., Tang X., Gong D., Li Q., Xu P., Field Investigation on River Hydrochemical Characteristics and Larval and Juvenile Fish in the Source Region of the Yangtze River. Water 11, 1342 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levenstein B., Lento J., Culp J., Effects of prolonged sedimentation from permafrost degradation on macroinvertebrate drift in Arctic streams. Limnol. Oceanogr. 66, S157–S168 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ward E. J., Anderson J. H., Beechie T. J., Pess G. R., Ford M. J., Increasing hydrologic variability threatens depleted anadromous fish populations. Glob. Chang. Biol. 21, 2500–2509 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.K. Norton-Smith, K. Lynn, K. Chief, K. Cozzetto, J. Donatuto, M. Hiza Redsteer, L. E. Kruger, J. Maldonado, C. Viles, K. P. Whyte, Climate Change and Indigenous Peoples: A Synthesis of Current Impacts and Experiences (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Farinotti D., Round V., Huss M., Compagno L., Zekollari H., Large hydropower and water-storage potential in future glacier-free basins. Nature 575, 341–344 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.R. Hock, G., C. Rasul, B. Adler, S. Cáceres, Y. Gruber, M. Hirabayashi, A. Jackson, S. Kääb, S. Kang, A. Kutuzov, U. Milner, S. Molau, B. Morin, Orlove, H. Steltzer, "High mountain areas” in IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska,K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N.M. Weyer, Eds. (IPCC, 2019), pp. 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kokelj S. V., Tunnicliffe J., Lacelle D., Lantz T. C., Chin K. S., Fraser R., Increased precipitation drives mega slump development and destabilization of ice-rich permafrost terrain, northwestern Canada. Glob. Planet. Change 129, 56–68 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bintanja R., Andry O., Towards a rain-dominated Arctic. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 263–267 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Katzenberger A., Schewe J., Pongratz J., Levermann A., Robust increase of Indian monsoon rainfall and its variability under future warming in CMIP6 models. Earth Syst. Dynam. 12, 367–386 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 56.A. Gobiet, S. Kotlarski, "Future climate change in the European Alps" in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science, A. Gobiet, S. Kotlarski, Eds. (Oxford Univ. Press, 2020), pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li D., Lu X., Overeem I., Walling D. E., Syvitski J., Kettner A. J., Bookhagen B., Zhou Y., Zhang T., Exceptional increases in fluvial sediment fluxes in a warmer and wetter High Mountain Asia. Science 374, 599–603 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pinzon J., Tucker C., A Non-Stationary 1981–2012 AVHRR NDVI3g Time Series. Remote Sens. 6, 6929–6960 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gan M., Chen C. L. P., Chen G.-Y., Chen L., On Some Separated Algorithms for Separable Nonlinear Least Squares Problems. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 48, 2866–2874 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Singh V. B., Ramanathan A. L., Suspended sediment dynamics in the meltwater of Chhota Shigri glacier, Chandra basin, Lahaul-Spiti valley, India. J. Mt. Sci. 15, 68–81 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Singh A. T., Sharma P., Sharma C., Laluraj C. M., Patel L., Pratap B., Oulkar S., Thamban M., Water discharge and suspended sediment dynamics in the Chandra River, Western Himalaya. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 129, 206 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gabet E. J., Burbank D. W., Pratt-Sitaula B., Putkonen J., Bookhagen B., Modern erosion rates in the High Himalayas of Nepal. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 267, 482–494 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mather A. L., Johnson R. L., Quantitative characterization of stream turbidity-discharge behavior using event loop shape modeling and power law parameter decorrelation. Water Resour. Res. 50, 7766–7779 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 64.P. Refaeilzadeh, L. Tang, H. Liu, "Cross-validation" in Encyclopedia of Database Systems, L. Liu, M. T. ÖZsu, Eds. (Springer US, 2009), pp. 532–538. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zheng H., Miao C., Li X., Kong D., Gou J., Wu J., Zhang S., Effects of Vegetation Changes and Multiple Environmental Factors on Evapotranspiration Across China Over the Past 34 Years. Earths Future 10, e2021EF002564 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang F., Shi X., Zeng C., Wang L., Xiao X., Wang G., Chen Y., Zhang H., Lu X., Immerzeel W., Recent stepwise sediment flux increase with climate change in the Tuotuo River in the central Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Bull. 65, 410–418 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hair J. F., Risher J. J., Sarstedt M., Ringle C. M., When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 31, 2–24 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 68.J. F. Hair Jr., G. T. M. Hult, C. M. Ringle, M. Sarstedt, N. P. Danks, S. Ray, “Evaluation of the structural model” in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook, J. F. Hair Jr., G. T. M. Hult, C. M. Ringle, M. Sarstedt, N. P. Danks, S. Ray, Eds. (Springer Cham, 2021), pp. 115–138. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wong K. K.-K., Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) techniques using SmartPLS. Mark. Bull. 24, 1–32 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Purwanto A., Sudargini Y., Partial Least Squares Structural Squation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Analysis for Social and Management Research : A Literature Review. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. Res. 2, 114–123 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nevitt J., Hancock G. R., Performance of bootstrapping approaches to model test statistics and parameter standard error estimation in structural equation modeling. Struct. Equ. Modeling 8, 353–377 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sarstedt M., Cheah J.-H., Partial least squares structural equation modeling using SmartPLS: A software review. J. Mark. Anal. 7, 196–202 (2019). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Text S1

Figs. S1 to S10

Tables S1 to S6

References