Abstract

A standardized, quantified assessment of furosemide responsiveness predicts acute kidney injury (AKI) in children after cardiac surgery and AKI progression in critically ill adults. The purpose of this study was to determine if response to furosemide is predictive of severe AKI in critically ill children outside of cardiac surgery. We performed a multicenter retrospective study of critically ill children. Quantification of furosemide response was based on urine flow rate (normalized for weight) measurement 0 to 6 hours after the dose. The primary outcome was presence of creatinine defined severe AKI (Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes stage 2 or greater) within 7 days of furosemide administration. Secondary outcomes included mortality, duration of mechanical ventilation and length of stay. A total of 110 patients were analyzed. Severe AKI occurred in 20% ( n = 22). Both 2- and 6-hour urine flow rate were significantly lower in those with severe AKI compared with no AKI ( p = 0.002 and p < 0.001). Cutoffs for 2- and 6-hour urine flow rate for prediction of severe AKI were <4 and <3 mL/kg/hour, respectively. The adjusted odds of developing severe AKI for 2-hour urine flow rate of <4 mL/kg/hour was 4.3 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.33–14.15; p = 0.02). The adjusted odds of developing severe AKI for 6-hour urine flow rate of <3 mL/kg/hour was 6.19 (95% CI: 1.85–20.70; p = 0.003). Urine flow rate in response to furosemide is predictive of severe AKI in critically ill children. A prospective assessment of urine flow rate in response to furosemide for predicting subsequent severe AKI is warranted.

Keywords: acute kidney injury, urine flow rate, furosemide, critically ill, pediatrics

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is common among critically ill children and is associated with worse outcomes. 1 Diagnosis of AKI is made by using either serum creatinine or urine output per the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria. 2 In a recent large multinational study, the assessment of creatinine alone for acute kidney injury (AKI) diagnosis would have resulted in nearly a third of AKI cases being missed. 1 AKI is an independent risk factor for morbidity and mortality in critically ill adults and children, 1 3 thus early identification may allow for the implementation of measures that reduce severity and thus complications. To identify patient risk early on in their intensive care unit (ICU) course, the prediction tools have attempted to risk stratify critically ill children for prediction of subsequent severe day-3 AKI. 4

Creatinine changes may vary in relation to the physiological demands of dietary and hemodynamic conditions in critically ill patients. Despite this, the elevation of creatinine meeting consensus criteria is associated with worse outcomes. A recent report revealed that AKI defined by urine output criteria was similarly associated with higher mortality compared with those without AKI. Patients who met both creatinine and urine had a significantly higher mortality than each criteria alone. 5 Assessment of urine output is important because it provides a reference for tubular handling of fluid. Early assessment of urine output could provide insight into the evolution of AKI before a patient meets AKI criteria. Quantification of urine output following administration of a medication that is not filtered by the glomerulus (i.e., furosemide), also known as the furosemide stress test (FST) may yield informative and actionable information on the evolution of AKI even in the absence of serum creatinine elevation. 6 7 8 This concept of stress testing is used to assess the reserve of an organ, and it has the potential to provide excellent diagnostic information in assessing progression of disease. Organ reserve is defined as the difference between maximal functional capacity and baseline functional capacity. The most familiar test of organ reserve is the cardiac treadmill stress test; and the FST has now been described as a study to assess renal tubular reserve. 6 In adults, the FST was prospectively assessed by measuring urine flow rate after an index dose of furosemide in adults with stage 1 and 2 AKI. A 2-hour urine output response was able to predict progression to stage 3 AKI within 14 days with excellent sensitivity and specificity. 9 Urine flow rate after furosemide has also been assessed for the prediction of AKI following pediatric cardiac surgery. 10 11 12 In these studies, lower urine flow rate was independently associated with subsequent AKI development. Quantification of urine flow rate following furosemide administration for prediction of AKI progression in other critically ill children is unknown.

The purpose of this study was to describe the use of furosemide and quantification of urine flow rate for prediction of AKI development or progression within 7 days. We hypothesized that lower urine flow rate after an index dose of furosemide would be associated with AKI development or progression.

Materials and Methods

We performed a multicenter retrospective study of children who were admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) from January to July 2015. Three urban children's hospitals were included Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center (1), The Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago (2), and Children's Hospital Colorado (3). Patients were included if they were <18 years of age and received an “index” dose of furosemide within 7 days of PICU admission. “Index” was defined as the first dose received. Patients who received continuous renal replacement therapy were included if it was initiated after the index furosemide dose. Patients were excluded if they were postcardiac surgery, less than 34 weeks' gestational age at the time of the furosemide dose, weighed <2 kg, furosemide administered at >7 days after PICU admission, use of a continuous infusion of furosemide or another type of diuretic, had greater than stage 2 chronic kidney disease, and had a history of kidney transplant. Institutional review board approval was obtained at each participating center with a waiver of informed consent.

Demographics, clinical characteristics, including Pediatric Risk of Mortality (PRISM) III scores 13 and outcomes were collected from the electronic health record. Comorbidities were classified by organ system: cardiac, respiratory, neurologic, nephrology/urologic, hematologic, oncologic, immunologic, hepato-intestinal, infectious, and endocrinologic. Patients may have a history of prior diuretic exposure, but only response to furosemide was assessed and patients were not included if they simultaneously received other diuretics. Baseline creatinine was defined as the lowest serum creatinine within 3 months prior to admission. If none was available, one was imputed assuming an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 120 mL/min/1.73m 2 and the bedside Schwartz factor (0.41) as previously described and validated. 14 A history of nonrenal transplant was recorded. Exposure to medications including nephrotoxins and vasoactive medications were captured. Nephrotoxic medications included nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (ibuprofen and ketorolac), antimicrobials (aminoglycosides, vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam, amphotericin, and antivirals), contrast, immunosuppressants, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, and methotrexate. The timing of nephrotoxin exposure to AKI development was not captured.

To characterize urine flow rate, we collected urine output data for 6 hours prior to and 6 hours after an index dose of furosemide. The presence of an indwelling bladder catheter for the purposes of this study was not required and was not captured in the case report form. The time at which the dose was administered is T 0 . Absolute hourly urine output was indexed for weight and hours (mL/kg/hour).

The dose of furosemide (“index dose”) was given per provider discretion and was recorded in milligrams per kilogram of patient bodyweight at ICU admission. Percent fluid overload (%FO) was assessed based on admission weight as previously described 15 at the time of admission, 6 hours before the dose of furosemide (T 0 -6) and at the time of furosemide (T 0 ). Time to furosemide was assessed from ICU admission to T 0 . Presence of AKI or its recovery was assessed by using the KDIGO serum creatinine criteria 2 in 7 days, which followed the dose of furosemide and classified as severe versus no AKI. The primary outcome was severe AKI defined as KDIGO stage 2 or greater after furosemide. Stage 1 AKI was classified as no AKI in the analysis, as this was not found to be associated with clinically relevant outcomes in a large multicenter pediatric AKI study, characterizing the epidemiology and outcomes of AKI in critically ill children. 1 AKI was also delineated into each AKI stage to demonstrate the progression and resolution of AKI. Secondary outcomes included duration of mechanical ventilation (MV), ICU length of stay (ICU LOS), and mortality. Duration of MV and ICU LOS were assessed from the time of MV initiation to discontinuation and ICU admission to discharge respectively.

Statistical analysis: Continuous variables were summarized as median with interquartile range (IQR) and compared by using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Categorical variables were summarized as frequency with percent and compared by using Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests as appropriate. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to determine the association between 2- and 6-hour urine flow rate and severe AKI after adjusting for confounders. An a priori list of candidate risk factors were considered in the regression analysis and included the following: age, pediatric PRISM III score, admission for sepsis, furosemide dose, history of transplant, comorbid diagnosis (categorized into the two groups: shock/medical cardiac and others such as central nervous system disease, postsurgical trauma, pain/sedation management, and respiratory failure). Confounders included in the multivariable model were selected if univariable associations indicated significance with a p -value <0.15. Furosemide dose (adjusted for weight) and urine flow rate were forced into the final model. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves analysis evaluated the ability of 2- and 6-hour urine flow rate to indicate development of severe AKI. Sensitivity, specificity, negative and positive predictive values and Youden's index were determined. The cut-off point of urine flow rate was determined based on a negative predictive value above 0.90 (indicated as clinically relevant for a physician to rule out the likelihood of subsequent severe AKI) and the Youden's index (an index weighing sensitivity and specificity equally). 16 17 After identifying the cutoff for both 2-hour and 6-hour urinary flow rate, patients were categorized into two groups based on the nearest whole number cutoff. The adjusted odds ratios comparing the two groups via multivariable logistic regression adjusting for the same confounding variables was performed. An interaction was assessed between age and ultra filtration rate (UFR). A Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed to determine the impact of urine flow rate groups with time to discharge after adjusting for severe AKI, age, PRISM-III score, and organ transplant. Multivariable logistic regression was used to determine the association of urine flow rate and severe AKI on mortality including the same confounders as described above. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) regression assessed associations of flow rate with duration of mechanical ventilation. Statistical significance level was set at α <0.05 level. Analysis was performed by using SAS software 9.4 (Cary, North Carolina, United States, and JMP. Copyright 2002–2012 SAS Institute Inc).

Results

One hundred eighteen patients received an “index” dose of furosemide. Five patients were excluded because they were >18 years and three were excluded for incomplete datasets. One hundred ten patients were included in the final analysis ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Consort flow diagram summarizing the total number of patients stratified by acute kidney injury staging at and after furosemide administration.

Twelve patients had AKI at furosemide administration (T 0 ), all of which (100%) were classified as stage 2 or 3. Twenty-two patients had severe AKI after furosemide (65%), of which five received continuous renal replacement therapy. One patient with AKI after furosemide recovered. A summary of AKI classification at and after furosemide administration are summarized in Fig. 1 .

The demographics, clinical characteristics, and outcomes of those with severe versus no AKI after furosemide are summarized in Table 1 . Patients with severe AKI after furosemide were older (median age: 169 vs. 33 months; p = 0.003). Even though a greater proportion of patients with admission diagnoses of shock (50 vs. 24%) and sepsis diagnosis (32 vs. 11%) experienced severe AKI (both p = 0.03), there was no difference in PRISM-III scores between groups ( p = 0.21). %FO on admission did not differ significantly between groups. %FO was assessed 6 hours prior to the index dose of furosemide and at the time of furosemide administration. There was no significant difference in %FO at these time points ( Table 1 ). Mechanical ventilation utilization, duration and LOS did not differ between patients with and without severe AKI. Mortality was significantly higher in those with severe AKI ( n = 7, 31.8%) compared with those without ( n = 9, 10.7; p = 0.03).

Table 1. Demographics, clinical characteristics, and outcomes of patients with and without severe acute kidney injury after furosemide.

| Overall ( n = 110) |

No/stage 1 AKI after furosemide ( n = 88) |

Severe AKI after furosemide ( n = 22) |

p -Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (mo) | 40.65 (11.93–138.49) | 33.69 (11.37–101.92) | 169.01 (31.36–196.23) | 0.003 |

| Sex (male) | 59 (53.6) | 46 (52.3) | 13 (59.1) | 0.74 |

| Weight (kg) | 17.75 (8.55–38.90) | 14.90 (8.15–29.68) | 43.45 (13.60–60.75) | 0.002 |

| Height (cm) | 98.50 (69.62–138.88) | 92.50 (68.38–129.12) | 146.20 (95.72–168.78) | 0.007 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Admission diagnosis | ||||

| Shock | 32 (29.1) | 21 (23.9) | 11 (50.0) | 0.03 |

| Respiratory failure | 59 (53.6) | 46 (52.3) | 13 (59.1) | 0.74 |

| Medical cardiac | 4 (3.6) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (13.6) | 0.03 |

| Postsurgical/trauma | 30 (27.3) | 28 (31.8) | 2 (9.1) | 0.06 |

| Central nervous system dysfunction | 7 (6.4) | 6 (6.8) | 1 (4.5) | 1.00 |

| Pain/sedation management | 7 (6.4) | 6 (6.8) | 1 (4.5) | 1.00 |

| Comorbidities (yes) | 29 (26.4) | 24 (27.3) | 5 (22.7) | 0.87 |

| Sepsis diagnosis | 16 (15.1) | 9 (10.7) | 7 (31.8) | 0.03 |

| Transplant Hx | 14 (12.7) | 11 (12.5) | 3 (13.6) | 1.00 |

| Bone marrow | 8 | 6 | 2 | |

| Liver | 3 | 3 | 0 | |

| Multvisceral | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Not reported | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Nephrotoxin Exp | 107 (97.3) | 85 (96.6) | 22 (100.0) | 0.88 |

| PRISM-III score | 7.00 (2.00–13.00) | 5 (2.00–13.00) | 10.50 (4.00–12.75) | 0.21 |

| Vasoactive support | 24 (21.8) | 15 (17.0) | 9 (40.9) | 0.03 |

| %FO (admission) | 8.05 (4.24–15.59) | 8.12 (5.97–16.03) | 6.21 (2.74–12.09) | 0.16 |

| %FO (T0–6) | 2.78 (−0.03 to 9.17) | 2.18 (−0.07 to 8.16) | 3.55 (0.32–12.09) | 0.37 |

| %FO (T0) | 6.99 (3.53–13.79) | 8.03 (4.20–14.66) | 5.61 (1.76–10.35) | 0.08 |

| Furosemide dose (mg/kg) | 0.49 (0.27–0.76) | 0.50 (0.27–0.77) | 0.37 (0.19–0.50) | 0.07 |

| UFR −6 to 0 h | 1.08 (0.60–2.47) | 1.31 (0.69–2.51) | 0.76 (0.31–1.08) | 0.02 |

| UFR −2 to 0 h | 1.05 (0–2.86) | 1.38 (0–3.33) | 0.53 (0–1.88) | 0.15 |

| UFR 2 h | 5.42 (1.61–10.49) | 6.12 (2.79–11.64) | 1.79 (0.01–4.73) | 0.002 |

| UFR 6 h | 4.61 (2.41–6.41) | 4.93 (3.41–6.58) | 2.03 (0.75–3.89) | <0.001 |

| Time from ICU admission to furosemide (d) | 1.64 (0.93–2.55) | 1.64 (0.97–2.58) | 1.63 (0.88–2.14) | 0.72 |

| Outcomes | ||||

| Mechanical ventilation (yes) | 50 (47.2) | 36 (40.9) | 14 (63.6) | 0.09 |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation (d) | 6.00 (3.00–9.75) | 6.00 (3.00–9.50) | 6.00 (3.00–10.00) | 0.99 |

| PICU LOS (d) | 9.00 (5.00–15.00) | 9.50 (5.00–15.00) | 8.00 (5.00–14.00) | 0.76 |

| CRRT | 5 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (22.7) | <0.001 |

| Mortality | 16 (15.1) | 9 (10.7) | 7 (31.8) | 0.03 |

Abbreviations: CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; PRISM-III, pediatric risk of mortality score; %FO, percent fluid overload; Hx, history; Exp, exposure; LOS, length of stay; T0–6, from 6 hours prior to the time of furosemide administration; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; T0, time of Lasix administration; UFR, urine flow rate;.

Note: Continuous variables as summarized as median with interquartile range. Categorical variables are summarized as number with percent.

Furosemide Response

The time from ICU admission to furosemide administration was not different between groups ( p = 0.72). Assessment of urine flow rate from T 0 -6 was significantly lower among those with severe AKI (median: 0.76; interquartile range [IQR]: 0.30–1.08) compared with those without AKI (median: 1.31, IQR: 0.69–2.51; p = 0.02). Assessment of urine flow rate T 0 -2 did not differ significantly different between those with and without AKI ( p = 0.15).

Assessment of urine flow rate (in mL/kg/hour) at T 0 + 2 among all patients with severe AKI was significantly lower compared with those without AKI (median: 1.79, IQR: 0.01–4.73 vs. median: 6.12, IQR: 2.79–11.64; p = 0.002). Similarly, urine flow rate in mL/kg/hour at T 0 + 6 was significantly lower among those with severe AKI (median: 2.03, IQR: 0.75–3.89 vs. median: 4.93, IQR: 3.41–6.58; p < 0.001).

Assessment of urine flow rates in patients stratified by presence or absence of AKI a furosemide and after furosemide are summarized in Fig. 2A and B . Urine flow rates in patients with no AKI (includes stage 1) after furosemide were higher than in patients with severe AKI ( Fig. 2A ). Patients with AKI at furosemide and had severe AKI after furosemide has lower urine flow rates than no AKI at both 2 and 6 hours. The urine flow rate among those with stage 3 AKI was lower than stage 2 AKI at both 2 and 6 hours ( Fig. 2B ).

Fig. 2.

Classification of AKI staging at the time of furosemide (T 0 ) and the maximal stage within 7 days after furosemide dose. ( A ) Of the 98 patients with no AKI on the day of furosemide (T 0 ), 23 developed AKI. Patients with stage two AKIs had the lowest urine flow rate after furosemide. ( B ) Of the 12 patients with AKI on the day of furosemide (T 0 ), one recovered function and 11 had persistent AKI. Patients with stage 3 AKI at and after furosemide had the lowest urine flow rate. AKI, acute kidney injury.

The optimal five cut-off points as measured by 2- and 6-hour urine flow rate were determined by using the maximum Youden's J index with NPV greater than 90%. The optimal cut point for 2-hour and 6-hour urine flow rate based on the Youden J statistic for predicting severe AKI were urine flow rate <4 mL/kg/hour and urine flow rate <3 mL/kg/hour, respectively. The sensitivity analysis for the actual cutoff value for both 2- and 6-hour urine flow rate is summarized in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 (available in the online version).

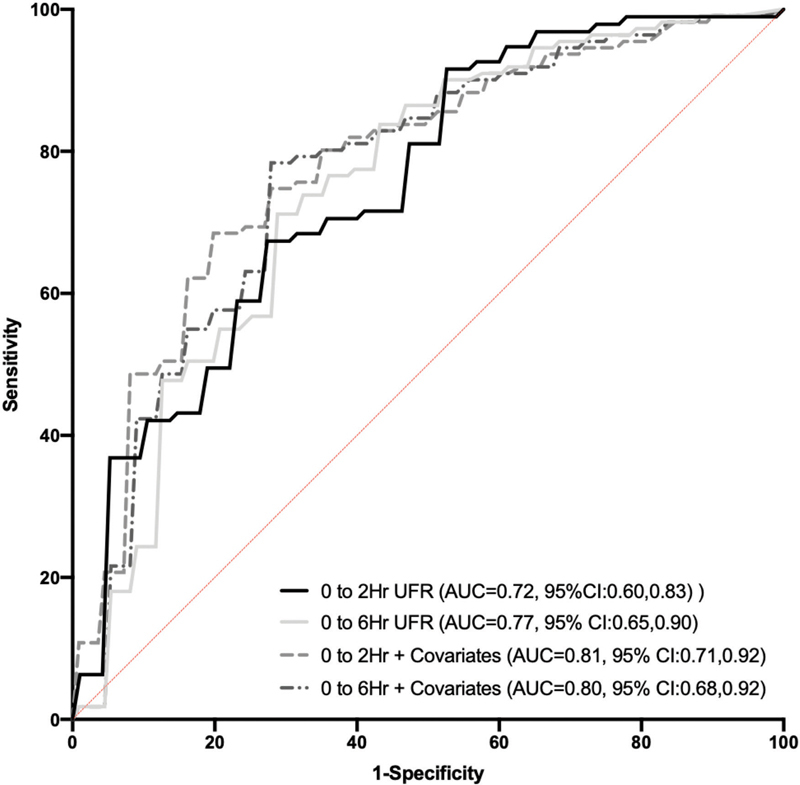

A ROC curve was constructed for severe AKI based on five separate models: (1) 2-hour urine flow rate without covariates, (2) 2-hour urine flow rate with covariates, (3) 6-hour urine flow rate without covariates, and (4) 6-hour urine flow rate with covariates. After adjustment for a priori covariates, the AUC for the 2- and 6-hour urine flow rate for predicting severe AKI were 0.81 (95% CI: 0.71–0.92) and 0.80 (95% CI: 0.68–0.92), respectively ( Fig. 3 ). The performance between the two adjusted models was not different. While age was associated with AKI in univariable and multivariable models, the interaction between age and urine flow rate was not significant suggesting than an association between urine flow rate and severe AKI is constant across the age range ( p = 0.25).

Fig. 3.

Receiver operating curve including 4 four separate models of urine flow rate for predicting severe acute kidney injury. (1) AUC for 2-hour urine flow rate = 0.70; (2) AUC for 6-hour urine flow rate = 0.76; and (3) AUC for 2-hour urine flow rate adjusting for the covariates of age, PRISM-III score, sepsis diagnosis, and weight-adjusted furosemide dose = 0.87; and (4) AUC for 6-hour urine flow rate adjusting for the covariates of age, PRISM-III score, sepsis diagnosis, and weight adjusted furosemide dose = 0.86. The models with the best performance for predicting severe acute kidney injury are the 2- and 6-hour urine flow rate after adjusting for covariates. AUC, area under the curve; PRISM-III, Pediatric Risk of Mortality Score III.

Analyses of dichotomized 2- or 6-hour urine flow rate included indicator variables of 2-hour urine flow rate <4 mL/kg/hour or 6-hour urine flow rate <3 mL/kg/hour, respectively. Associations with severe AKI were adjusted for age, indication of sepsis, and urine flow rate.

The estimated unadjusted odds of 2-hour urine flow rate of <4 mL/kg/hour predicting severe AKI after furosemide was 4.67 (95% CI: 1.66–13.12; p = 0.004). After adjusting for confounding variables, the adjusted odds of severe AKI after furosemide based on 2-hour urine flow rate was 4.3 (95% CI: 1.33–14.15; p = 0.02). The unadjusted odds of severe AKI after furosemide based on 6-hour urine flow rate was 7.78 (95% CI: 2.77–21.81; p < 0.0001). The adjusted odds of 6-hour urine flow rate for severe AKI after furosemide was 6.19 (95% CI: 1.85–20.70; p = 0.003).

Median PICU LOS was no different between urine flow rate groups at 2 and 6 hours. In the univariable Cox proportional hazard models, there was no association observed between dichotomized 2- or 6-hour urine flow rate and time to discharge. After adjusting for PRISM-III scores and indication of transplant, there was still no observed association between urine flow rate and time to discharge. Similarly, there was no association between a lower urine flow rate at 2 or 6 hours with duration of mechanical ventilation. In the unadjusted and adjusted multivariable logistic analyses, there was no association of both 2- and 6-hour urine flow rate or AKI with mortality.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that urine flow rate response to an index dose of furosemide may inform clinicians on whether AKI will develop, persist or progress among critically ill children. Urine flow rate is important because it provides a reference for tubular handling of fluid. A decrement in urine flow rate after furosemide, below a specified threshold would indicate a potential problem with fluid homeostasis. This study was able to quantify urine flow rate after furosemide and demonstrated a difference in the distribution at 2 and 6 hours in patients with severe AKI and no AKI. Similar to the adult prospective study by Chawla et al; in which patients underwent the “furosemide stress test,” 9 we were able to demonstrate subtle differences in urine flow rate in those with changing AKI stage, although we were limited by adequate power. This highlights the importance of assessing fluid homeostasis in a systematic and standardized fashion to risk stratify patients for development of or progression of AKI. This has the potential to provide informative and actionable information on the evolution of AKI for implementation of mitigative strategies.

Assessment of urine flow rate in the absence of stimulation provides a static assessment of renal function, specifically of how the kidney is performing at a single point in time, reflecting homeostasis and overall organ function, i.e. determining whether the kidneys are already impaired. The furosemide stress test provides a dynamic assessment of renal tubular health. Furosemide is a loop diuretic that is not filtered by the glomerulus, but it gains access to the tubular lumen and blocks cation-chloride transport throughout the ascending loop of Henle, preventing sodium reabsorption. In order for furosemide to increase urine output, it must be actively secreted into the proximal lumen. The functions of the thick ascending limb, luminal patency, and collecting duct must all be intact. A decrement in the response to furosemide below a predefined threshold, which suggests the evolution of progressive renal dysfunction 6 7 8 as demonstrated by 11 of the patients with no AKI at furosemide and severe AKI within the 7 day observation period after furosemide. Thus, it can be used as a functional capacitance marker identifying the amount of reserve left in the renal tubular system. Quantifying urine flow rate after furosemide in conjunction with other “tests” of renal health, including risk for AKI using the renal angina index, 4 or confirmatory testing using tubular biomarkers provide a multidimensional dynamic assessment for AKI as presented in a novel construct for a biomarker composite described by Basu et al . 18 In this construct, each parameter provides a parallel to mechanistic characteristics and biology of existing or evolving AKI. While this construct is theoretical, it highlights—in conjunction with this study—the need to prospectively study the utility of furosemide responsiveness for the prediction of AKI progression in critically ill children, where dose and timing are controlled and there is precision in quantifying urine output. The inability to quantify hourly urine output after furosemide may reflect the higher urine flow rate in patients with stage 3 versus stage 2 AKI. It is known that a single episode of AKI lowers the reserve for a subsequent episodes, 19 and increases CKD risk. 20 21 Any efforts to mitigate or reduce the severity of AKI (i.e., avoidance of nephrotoxic medications) 22 could be implemented by assessing urine flow rate following furosemide.

Unfortunately, response to furosemide in this cohort for predicting evolution, persistence, or progression of AKI was not as robust as the initial prospective adult studies. 8 9 23 Similarly, urine flow rate following furosemide for the prediction of AKI after pediatric cardiac surgery 10 11 12 also performed better than in this cohort. The reasons for this are many and may include selection bias (only studying those who received furosemide vs. its ubiquitous use after pediatric cardiac surgery or a prospective study), the timing and dose of furosemide were not standardized, and the quantification of urine output is challenging in incontinent children without indwelling bladder catheters. The reason for urine flow rate cutoff being higher in this study compared with Chawla et al 9 may be due to the intra- and intercenter practice variation as it relates to the indication and timing of furosemide administration. For example, some practitioners may elect to administer furosemide in a “last ditch effort” to avoid renal replacement therapy, while others may administer it earlier during the course of hospitalization during the incipient stages of fluid accumulation and AKI.

We noted differences in age, weight, and height among patients with severe AKI after furosemide compared with no AKI. Furthermore, age was associated with AKI in univariable and multivariable models. Because of this association, an interaction between age and urine flow rate was assessed to evaluate if renal physiology in younger patients may be different from older children after furosemide. There was no interaction between urine flow rate and age suggesting that an association between urine flow rate and severe AKI is constant across the age ranges. Another plausible explanation for the differences in patient age may be related to inherent bias in selecting who received furosemide. This highlights the need for a prospective study in which all pediatric ICU patients can be evaluated.

In this study, neither 2- or 6-hour urine flow rate nor severe AKI were associated with the clinically relevant outcomes of mechanical ventilation duration, PICU LOS, and mortality. These data are not intended to minimize the effect of severe AKI on outcomes but to characterize the effect of furosemide on urine flow rate and AKI. These data suggest that other factors, including selection bias by only including those who received furosemide, and small sample size may play a role.

The major strength of this study is that it is a multicenter investigation that encompasses a heterogeneous cohort of critically ill children who receive care under different states of clinical practice, thereby making the results generalizable to other critically ill children. Several limitations warrant discussion. This is a retrospective study, with a small sample size resulting in wide confidence intervals in logistic regression analysis. Only patients who received furosemide within the first 7 days of PICU admission were included in this study, which excludes those who may have worsened and received furosemide after that time point or were unstable. The indication for furosemide was not able to be captured from the electronic health record nor were we able to discern if urine output was affected by other factors (glycosuria, electrolyte disturbances, and syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, etc.). It was not possible to stratify the results by site as this led to a quasi-complete separation of data points when fitting regression models. The proportion of patients with a urinary bladder catheter was unknown, confounding the quantification of urine output in this cohort. Sixteen patients had no documented urine output for 0 to 2 hours after the furosemide dose, and one patient had no urine documented for the entire 6-hour period. It is unclear if this is a measure of true oliguria or the documentation of urine output that occurred less frequently. Finally, furosemide indication, dose, and administration route (affects bioavailability when oral) were not standardized between patients.

In conclusion, urine flow rate in response to furosemide was predictive of severe AKI in the 7 days following its administration. A prospective assessment of urine flow rate in response to a standardized dose of furosemide prescribed at a specific time during the ICU course and with an indwelling bladder catheter for predicting subsequent severe AKI is warranted.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Dr Ben Rosenfeld, for assisting with data collection at Northwestern University/Lurie Children's Hospital, United States.

Funding Statement

Funding J.B. disclosed that a portion of his FTE is supported by the Children's Hospital Colorado Research Institute and Pediatric Kidney Injury and Disease Stewardship Program to help with analyses and manuscript preparation. D.E.S. is funded by an NIH K08 Career development award.

Conflict of interest None declared.

Note

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee at which the studies were conducted (IRB approval number: 15–1645) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved with a waiver of informed consent.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.AWARE Investigators . Kaddourah A, Basu R K, Bagshaw S M, Goldstein S L, Investigators A. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in critically ill children and young adults. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(01):11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.KDIGO AKI Guideline Work Group . Kellum J A, Lameire N, Group K AGW. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of acute kidney injury: a KDIGO summary (Part 1) Crit Care. 2013;17(01):204. doi: 10.1186/cc11454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rewa O, Bagshaw S M. Acute kidney injury-epidemiology, outcomes and economics. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10(04):193–207. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2013.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basu R K, Zappitelli M, Brunner L et al. Derivation and validation of the renal angina index to improve the prediction of acute kidney injury in critically ill children. Kidney Int. 2014;85(03):659–667. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Assessment of Worldwide Acute Kidney Injury, Renal Angina and, Epidemiology (AWARE) Investigators . Kaddourah A, Basu R K, Goldstein S L, Sutherland S M. Oliguria and acute kidney injury in critically ill children: implications for diagnosis and outcomes. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2019;20(04):332–339. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chawla L S, Ronco C. Renal stress testing in the assessment of kidney disease. Kidney Int Rep. 2016;1(01):57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McMahon B A, Koyner J L, Novick T et al. The prognostic value of the furosemide stress test in predicting delayed graft function following deceased donor kidney transplantation. Biomarkers. 2018;23(01):61–69. doi: 10.1080/1354750X.2017.1387934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koyner J L, Chawla L S. Use of stress tests in evaluating kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2017;26(01):31–35. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chawla L S, Davison D L, Brasha-Mitchell E et al. Development and standardization of a furosemide stress test to predict the severity of acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2013;17(05):R207. doi: 10.1186/cc13015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kakajiwala A, Kim J Y, Hughes J Z et al. Lack of furosemide responsiveness predicts acute kidney injury in infants after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104(04):1388–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borasino S, Wall K M, Crawford J H et al. Furosemide response predicts acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery in infants and neonates. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018;19(04):310–317. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Penk J, Gist K M, Wald E L et al. Furosemide response predicts acute kidney injury in children after cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;157(06):2444–2451. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.12.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pollack M M, Patel K M, Ruttimann U E. PRISM III: an updated pediatric risk of mortality score. Crit Care Med. 1996;24(05):743–752. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199605000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zappitelli M, Parikh C R, Akcan-Arikan A, Washburn K K, Moffett B S, Goldstein S L. Ascertainment and epidemiology of acute kidney injury varies with definition interpretation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(04):948–954. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05431207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sutherland S M, Zappitelli M, Alexander S R et al. Fluid overload and mortality in children receiving continuous renal replacement therapy: the prospective pediatric continuous renal replacement therapy registry. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(02):316–325. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Youden W J. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1950;3(01):32–35. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::aid-cncr2820030106>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zou K H, Yu C R, Liu K, Carlsson M O, Cabrera J. Optimal thresholds by maximizing or minimizing various metrics via ROC-type analysis. Acad Radiol. 2013;20(07):807–815. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basu R K. Dynamic biomarker assessment: a diagnostic paradigm to match the AKI syndrome. Front Pediatr. 2020;7:535. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasson D C, Brinton J T, Cowherd E, Soranno D E, Gist K M. Risk factors for recurrent acute kidney injury in children who undergo multiple cardiac surgeries: a retrospective analysis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2019;20(07):614–620. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayes W. Stop adding insult to injury-identifying and managing risk factors for the progression of acute kidney injury in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2017;32(12):2235–2243. doi: 10.1007/s00467-017-3598-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sigurjonsdottir V K, Chaturvedi S, Mammen C, Sutherland S M. Pediatric acute kidney injury and the subsequent risk for chronic kidney disease: is there cause for alarm? Pediatr Nephrol. 2018;33(11):2047–2055. doi: 10.1007/s00467-017-3870-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldstein S L, Dahale D, Kirkendall E S et al. A prospective multi-center quality improvement initiative (NINJA) indicates a reduction in nephrotoxic acute kidney injury in hospitalized children. Kidney Int. 2020;97(03):580–588. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2019.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen J J, Chang C H, Huang Y T, Kuo G. Furosemide stress test as a predictive marker of acute kidney injury progression or renal replacement therapy: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2020;24(01):202. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02912-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.