Abstract

Objectives This study aimed to evaluate factors affecting the quality of life (QOL) of parents of children who underwent placement of a tracheostomy while in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) through postdischarge use of a standardized questionnaire, Functional Status Scale (FSS) for patients, and WHOQoL-BREF (a QOL scale) for parents.

Methods The parents were initially contacted by telephone, postdischarge, during which the standardized questionnaire was completed. The functional status of the patients was evaluated using the FSS, and the QOL of parents was determined through use of the WHOQoL-BREF scale.

Results From 2011 to 2021, tracheostomy was performed in 119 PICU patients. Overall, 93 patients were excluded due to death in 66 (56%), decannulation in 24 (20%) and, 3 (2%) were not available for follow-up. The parents of 26 (22%) patients were available for follow-up and for which the standardized questionnaire FSS and WHOQoL-BREF QOL scales were completed. The mean FSS score of the patients was elevated at 17.84. In comparison, reduced mean scores were observed for parental physical health of 20.61, psychological health of 20.57, social health of 11.15, and environmental health of 29.00. As a result, a moderate ( r < 0.80), yet significant ( p ≤ 0.004) negative correlation was found between the FSS scores of patients and the physical, social relationships, environmental, and psychological health QOL scores of parents.

Conclusion This study is unique in that, to our knowledge, it is the first to compare parental QOL with the FSS of pediatric patients who have undergone a tracheostomy while hospitalized in the PICU. Our findings indicate that the parental QOL was reduced in four areas and correlates with an elevation in FSS score (indicating a greater functional disorder) of pediatric patients who had previously undergone a tracheostomy while hospitalized in the PICU.

Keywords: pediatric tracheostomy, quality of life, Functional Status Scale

Introduction

Chronic childhood diseases are continuously increasing and have become a significant health problem in Turkey, as in many countries worldwide. The survival of patients with chronic diseases has improved with the development of medical technologies such as mechanical ventilation facilitated by the performance of a tracheostomy to enable outpatient mechanical ventilation for pediatric patients for whom the necessity has evolved in the presence of a reduction in mortality associated with critical illness for both adults and children. If a child requires a technological device to meet life preserving requirements due to a chronic disease, the child is referred to as “a technology-dependent child” or “a child with special care needs.” 1 2 The frequently used technological devices include those for respiratory support (such as tracheostomies for mechanical ventilation), nutritional support in the form of central venous catheters for parental and gastrostomy tubes for enteral routes of administration, and basic fluid and medication delivery also through catheters placed centrally or by insertion of peripherally inserted central venous catheters.

A tracheostomy is performed for ∼100,000 patients annually in the United States, of which up to 4,000 are pediatric patients. 3 Respiratory support provided at home aims to prolong the child's survival, reduce the risk of comorbidities, improve their physical and psychological status, and improve the quality of life (QOL) for not only the child but also the family. Unfortunately, not only are the costs related to maintenance of the tracheostomy and at-home respiratory support both significant, but also severe complications and subsequent nonsurvival may occur in up to 1,000 patients annually for reasons associated with the tracheostomy. 4 As a result, this subject is of particular importance to pediatric patients who survive their pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) course but are discharged with technologically dependent devices such as a tracheostomy.

It is obvious that caring for a child with a tracheostomy requires maintenance of their growth and developmental processes that will affect all family members. 5 Primary caregivers, who are commonly the child's parent(s), will be affected more often than other individuals. 6 The caregivers of technologically dependent children, such as those with tracheostomies, have been reported to encounter problems in their personal, family, and social lives. 7 It has been determined that the physical and psychological health of these primary caregivers is associated with the disability status of the child. In particular, those caring for children with a tracheostomy have been shown to experience more mental and physical difficulties compared with those providing care to nontechnologically dependent children. 8 As a result, it is essential that the QOL be monitored not only for technologically dependent children but also for their caregivers.

Scales have been developed that measure the QOL for caregivers, including those of technologically dependent children. The components of these scales include physical, occupational, social, psychological, and economic status. One such scale used to examine caregiver QOL is the WHOQoL-BREF Scale, developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), which consists of 27 items that are organized into four areas. 9 This scale is a validated method that has been shown to reliably reflect the caregiver's general health, QOL, and well-being related to their physical, social, psychological, and environment status as described in Turkey by Eser et al in 1999. 10

The Functional Status Scale (FSS) is another valuable and well-validated scale that measures functional (emotional, mental, and motor) and ongoing nutritional, respiratory, and communicative status of patients following discharge. Items are scored from 1 to 5 points, with higher scores indicating a higher functional disorder.

In summary, this study aimed to determine the factors affecting the QOL of the parents of technologically dependent children with a tracheostomy through the use of a standardized questionnaire and validated scales reflecting the functional status of patients (FSS) and QOL of their caregivers (WHO-QoL-BREF scale) following discharge from the PICU.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective observational study was conducted in a multidisciplinary eight-bed PICU that admits approximately 450 patients annually. Initial inclusion criteria for prospective patients consisted of those PICU patients for whom a tracheostomy was performed within the 10-year period from January 2011 and December 2021. Once identified, the parents of prospective patients were contacted postdischarge, by telephone, during which verbal consent was requested for participation in this study. Once consent was obtained, a standardized questionnaire was completed by the caregivers (usually parents). Questions consisted of both patient and caregiver characteristics. Patient characteristics included use of current medications; description of home care services to include educational, nutritional, physical therapy, and respiratory support; history of aspiration pneumonia; and frequency of infections. In addition, caregivers were asked respective questions about their age, marital status, education, and income level (income vs. debt); home-related questions related to location, environmental conditions, and presence of other individuals requiring simultaneous care; problems experienced following discharge to home; and logistical data that included the means by which and time taken to reach health care facilities for their child with a tracheostomy.

Patient-centered data were retrospectively obtained from the hospital records system. and consisted of demographic information, primary diagnoses, PICU and hospital length of stay, duration of mechanical ventilation (DMV), indications for performing the tracheostomy, and complications that developed during the hospital course.

Patient and caregiver data were then completed through evaluation of the functional status of the patients and the QOL of their caregivers through utilization of the FSS and WHOQoL-BREF scale, respectively. The FSS is a well-defined, quantitative, reliable, and validated scale that is reliant on objective and not subjective findings. The WHOQoL-BREF scale is a well-validated and respected tool developed by the WHO. Our study was approved by the University Hospital Ethics Committee. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical rules and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

In the defined 10-year period from 2011 to 2021, tracheostomy was performed in 119 patients, of which 93 were not eligible for inclusion: 66/93 (55.4%) patients died, 24 (20.1%) were decannulated, and the caregiver(s) of 3 (2.5%) patients could not be contacted. Of note, among nonsurvivors, 45.4% had a neurometabolic disease and 27.2% had malignancy.

The parents or caregivers of 26 patients were contacted and provided consent enabling completion of the standardized questionnaire, FSS, and QOL scale. Of these 26 patients with tracheostomy, 21 (80.8%) were males and 5 (19.2%) were females with a mean age of 102 months. The mean age of the caregivers was 37.6 years. The reported income level was below their debt for 3 (11.5%), equal to their debt for 17 (65.4%), and greater than their debt in 6 (23.1%). The education level of caregiver parents was reported as a university graduate in 15.4% and high school or lower in the remaining 84.6%. Detailed demographic data are presented in Table 1 .

Table 1. Patient and caregiver demographics.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient gender (male) | 21 | 80.8 |

| Patient age (mo), mean (SD) | 102 (88) | 85.9 |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation, d (SD) | 22 (69) | 7.2 |

| Length of stay in PICU, d, (SD) | 42 (61) | 36.6 |

| Length of stay in hospital, d, (SD) | 57 (50) | 36.0 |

| Caregiver age (y), mean (SD) | 37 (62) | 8.9 |

| Caregiver's education level | ||

| High school or less | 22 | 84.6 |

| University graduate | 4 | 15.4 |

| Income level | ||

| Income < debts | 3 | 11.5 |

| Income = debts | 17 | 65.4 |

| Income > debts | 6 | 23.1 |

| Residence location | ||

| City center | 16 | 61.5 |

| Country | 8 | 38.5 |

| Number of siblings | ||

| 1 | 7 | 26.9 |

| 2–3 | 13 | 50.0 |

| > 4 | 6 | 23.1 |

| Receiving home care services | ||

| Yes | 9 | 34.6 |

| No | 17 | 65.4 |

| Presence of others requiring care at home | ||

| Yes | 3 | 11.5 |

| No | 23 | 88.5 |

| Travel time to health care facilities | ||

| < 30 min | 18 | 69.2 |

| 30–60 min | 8 | 30.8 |

| Means of travel to health care facilities | ||

| Caregiver vehicle | 19 | 73.1 |

| Ambulance | 7 | 26.9 |

Abbreviations: PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; SD, standard deviation.

The primary diagnosis and indications for tracheostomy were identified in detail. The most common primary diagnosis for patients undergoing a tracheostomy was neuromuscular in eight (30.8%) patients and neurometabolic disease in seven (26.9%) patients. The most common indication for a tracheostomy to be performed was determined to be prolonged mechanical ventilation in 17 (65.4%) patients, which included 11 (42.3%) patients with coexisting neurological disease and 6 (23.1%) patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation but without coexisting neurological disease as outlined in Table 2 .

Table 2. Patient characteristics.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary diagnosis | ||

| Neuromuscular | 8 | 30.8 |

| Trauma | 3 | 11.5 |

| Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy | 5 | 19.2 |

| Neurometabolic | 7 | 26.9 |

| Pulmonary | 3 | 11.5 |

| Indications for tracheostomy | ||

| Upper airway obstruction | 5 | 19.2 |

| Existing neurological disease and prolonged mechanical ventilation | 11 | 42.3 |

| Prolonged mechanical ventilation | 6 | 23.1 |

| Neuromuscular disease | 4 | 15.4 |

| Respiratory support | ||

| Home mechanical ventilation and oxygen support | 10 | 38.5 |

| Home mechanical ventilation | 8 | 30.8 |

| Nasal cannula | 2 | 7.7 |

| Not receiving oxygen support | 6 | 23.1 |

| Frequency of infections | ||

| < 1/y | 9 | 34.6 |

| 1–3/y | 12 | 46.2 |

| > 3/y | 5 | 19.2 |

| Physical therapy | ||

| Yes | 7 | 26.9 |

| No | 19 | 73.1 |

| Nutritional support | ||

| Gastrostomy | 18 | 69.2 |

| Nasogastric catheter | 3 | 11.5 |

| Oral | 5 | 19.2 |

| Aspiration pneumonia | ||

| Yes | 3 | 11.5 |

| No | 23 | 88.5 |

Home care services were utilized for 9 (34.6%) patients. Respiratory support included home mechanical ventilation in 18 (69.3%) patients with both supplemental oxygen support in 10 (38.5%) patients and for 8 (30.8%) patients without supplemental oxygen support. The remainder of patients received either nasal cannula support solely in two (7.7%) patients and no oxygen support in six (23.1%) patients. Physical therapy was noted in only seven (26.9%) patients. Nutritional support was provided by gastrostomy tube in 18 patients (69.2%), followed by oral route in 5 (19.2%) patients and nasogastric catheter in 3 (11.5%) patients. Readmissions (≥1) were experienced in only five patients. The frequency of infections following discharge for these tracheotomized patients was not unexpected as 17 (65.4%) of patients had ≥1 infections per year.

The standardized questionnaire completed by caregivers revealed reduced mean scores for physical health of 20.61, psychological health of 20.57, social score of 11.15, and environmental health of 29.00. The mean FSS score of the study patients was found to be elevated at 17.84.

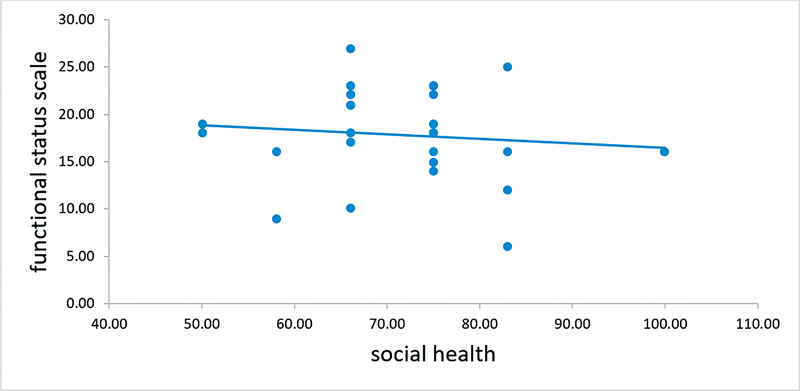

A moderate, yet significant negative correlation was determined between the FSS scores of the patients and the physical health ( r = 0.548; p = 0.004; Fig. 1 ), social relationships ( r = 0.665, p < 0.001; Fig. 2 ), environmental health ( r = 0.802, p < 0.001; Fig. 3 ), and psychological health ( r = 0.675, p < 0.001; Fig. 4 ) scores of the caregiver.

Fig. 1.

The relationship between physical health and Functional Status Scale (FSS) score.

Fig. 2.

The relationship between social health and Functional Status Scale (FSS) score.

Fig. 3.

The relationship between environmental health and Functional Status Scale (FSS) score.

Fig. 4.

The relationship between psychological health and Functional Status Scale (FSS) score.

The physical health status of the parents caring for children with a tracheostomy for greater than 1 year was significantly better than that of the parents caring for their child for less than 1 year ( p = 0.009). A statistically significant positive correlation was also found between the caregiver age and psychological health—as the caregiver age increased, so did their psychological health scores. No statistically significant correlation was noted between the caregiver education level and the health scores. Of interest, in the evaluation of economic status, the social relationship scores of caregivers with income less than their debt were found to be significantly higher than those of the caregivers with income exceeding their debt. No statistically significant correlation was determined between the patient's ventilation status and the caregiver's health scores on the QOL questionnaire. No statistically significant correlation was determined between the frequency of infection, frequency of aspiration, physical therapy status, or type of nutrition of the patients and the scores of caregivers ( p > 0.05). The presence of another person, in the same home who also required care, worsened the caregivers' psychological and environmental health scores; fortunately, this finding was not statistically significant. The psychological health scores of caregivers living in the city center were found to be lower than the scores of those not living in the city center.

Discussion

In a recent study in Turkey, Harputluoğlu et al 11 evaluated the health status of caregivers for patients requiring palliative care using the WHOQoL-BREF questionnaire. They reported that the physical health score was 19.90, the psychological health score was 19.98, the social score was 10.24, and the environmental health score was 24.59. Similarly, in a 2019 study in Japan, Mutoh et al 12 evaluated caregivers of children with cerebral palsy and indicated the physical health score to be 21.70, psychological health score to 18.00, social score to be 10.30, and environmental health score to be 25.30. Our findings are consistent with each of these two studies. Thus, it is not unreasonable to anticipate that the QOL scores are similar for parents caring for children who are either “technologically dependent” or require “special care needs.” Furthermore, several studies have determined that social health scores of caregivers receiving social support are higher than those not receiving social support. 11 13 Again, our findings are similar. In the current study, not only social scores but also physical health scores were greater for those receiving home care services than for those caregivers not receiving these services. Even though the difference was not statistically significant, the effect size was significant for social relationships (Cohen's d = 0.845) and physical health (Cohen's d = 0.806).

As a result, measures to improve caregiver health as measured by QOL scales is an important facet in the ongoing care for technological-dependent and special care need children. This is highlighted by the ongoing need for patient follow-up as indicated in 66 (55.4%) of the 119 patients in the current study. Although this rate was slightly higher than reported in the literature, it was necessary as 45.4% of the patients were afflicted with a neurometabolic disease and 27.2% suffered from malignancy. The requirement for long-term follow-up is further supported by the associated increased risk of mortality as noted in the study by Sekioka et al 14 in which children with a tracheostomy due to neurometabolic disease had an exceptionally high mortality rate of 46%. Therefore, attention to caregiver health is necessary to ensure the long-term follow-up and to reduce the associated risk of mortality for those children who require a tracheostomy.

The noted trend of an increase in chronic childhood diseases has led to the increased necessity for tracheostomy placement in pediatric patients to enable home ventilator management. As outlined in a study by Farida et al, 15 tracheostomy is often performed because of neurological diseases. This is consistent with the findings of the current study where the most common indication for tracheostomy was existing neurologic disease precipitating the need for prolonged mechanical ventilation. Our findings are further supported by two other studies conducted in Turkey, where the most common indication for tracheostomy was the need for prolonged mechanical ventilation in children with concurrent neurological disease. 16 17

We noted another benefit associated with the use of a standardized questionnaire to examine the health of caregivers for patients requiring ongoing care at home. Specifically, in the current study, parent caregivers of children with a tracheostomy with a period of care greater than 1 year were found to have better physical health compared with those caregivers with a period of care shorter than 1 year. In contrast, Harputluoğlu et al 11 noted no association between caregiver health and disease duration of patients requiring palliative care. We believe that our finding of parental adaptation to their caregiver roles is most likely attributed to their successful adjustment of lifestyle and physical conditions to accommodate their child's ongoing needs.

The presence of an additional person in the home requiring the same caregiver(s) care is an interesting facet. Tamayo et al 18 reported that a second person in the home requiring care added to the caregiver's responsibilities negatively affecting their physical, psychological, and environmental health. In the current study, even though our findings were similar, there was no statistical difference in caregiver health scores for those with and without additional patient care responsibilities in their home environment.

We were also interested in the aspect of residential home location, identified as living either within the city center or in a rural location, as regard its effect on the psychological health of caregivers. The findings of this study indicated that the psychological health scores of the caregivers living within a city center were lower than the scores of those not living within a city center. Our interpretation of this finding is the presence of greater environmental pressure for those living within city centers versus the beneficial presence of greater social support from family and friends for those residing in rural or non-city-center locations.

The most important aspect of this study was that, to our knowledge, this is the first study to compare caregiver's QOL with an FSS for those reliant on their care. The presence of high FSS scores is indicative of poor functional status of the latter. A moderately strong negative correlation was found between the FSS score of pediatric patients with a tracheostomy and caregiver QOL scores. Previous studies have compared caregiver QOL with other FSS of impaired patients once discharged home. Surender et al 19 noted that QOL was reduced for caregivers responsible for cerebral palsy patients who had greater loss of motor function and more restricted motor movement. Dobhal et al 20 revealed similar and consistent findings whereby, patient's physical independence, movements, and physical limitations were greater determinants of the caregiver's QOL as opposed to the family's economic status.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first clinical study to evaluate the QOL for caregivers with the functional status of pediatric patients under their care once discharged from the PICU to home. The QOL scores for caregivers, as measured by the WHOQOL-BREF scale, were found to be lower for caregivers of pediatric patients who received a tracheostomy for home ventilation, a finding that is likely due to a decline in the functional status of these patients as measured by the FSS. The reduction in caregiver QOL consisted of lower scores in four areas: physical health, psychological health, social health, and environmental health. We believe our findings support further prospective study to confirm our results utilizing greater numbers and wider diversity of patients. Additionally, it would be of interest to determine if relationships exist between demographic data and both caregiver QOL and patient's FSS as none were found in this study. If comparable results were found, this could facilitate guidance to more effectively utilize limited resources to provide necessary educational, psychological, and social support for the caregivers and families of pediatric patients with a lower functional status.

Conflict of Interest None declared.

Ethical Approval

The University Hospital Ethics Committee approved the study. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical rules and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient Consent

Signed informed consent statement was obtained from the parents/guardians of all patients included in this study.

Authors' Contributions

Research idea and study design were developed by Alper Koker. Data acquisition was done by Alper Koker. Data analysis/interpretation was done by Gonca Şahan Erbaşı Nalbant. Statistical analysis was done by Nazan Ulgen Tekerek. Supervision and mentorship were done by Oguz Dursun.

References

- 1.Glendinning C, Kirk S, Guiffrida A, Lawton D. Technology-dependent children in the community: definitions, numbers and costs. Child Care Health Dev. 2001;27(04):321–334. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2001.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beale H. Respite care for technology-dependent children and their families. Paediatr Nurs. 2002;14(07):18–19. doi: 10.7748/paed.14.7.18.s17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCormick M E, Ward E, Roberson D W, Shah R K, Stachler R J, Brenner M J. Life after tracheostomy: patient and family perspectives on teaching, transitions, and multidisciplinary teams. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153(06):914–920. doi: 10.1177/0194599815599525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das P, Zhu H, Shah R K, Roberson D W, Berry J, Skinner M L. Tracheotomy-related catastrophic events: results of a national survey. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(01):30–37. doi: 10.1002/lary.22453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.North American Growth in Cerebral Palsy Study . Stevenson R D, Conaway M, Chumlea W C et al. Growth and health in children with moderate-to-severe cerebral palsy. Pediatrics. 2006;118(03):1010–1018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ones K, Yilmaz E, Cetinkaya B, Caglar N. Assessment of the quality of life of mothers of children with cerebral palsy (primary caregivers) Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2005;19(03):232–237. doi: 10.1177/1545968305278857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yilmaz H, Erkin G, Nalbant L. Depression and anxiety levels in mothers of children with cerebral palsy: a controlled study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2013;49(06):823–827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brehaut J C, Kohen D E, Raina P et al. The health of primary caregivers of children with cerebral palsy: how does it compare with that of other Canadian caregivers? Pediatrics. 2004;114(02):e182–e191. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.2.e182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The WHOQOL Group . The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46(12):1569–1585. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eser E, Fidaner H, Fidaner C, Eser S, Elbi H, Göker E. WHOQOL-100 and WHOQOL-BREF psychometric properties [in Turkish] 3P Derg. 1999;7:23–41. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harputluoğlu N, Alkan Özdemir S, Yılmaz Ü, Çelik T. Evaluation of primary caregiver parents' quality of life in pediatric palliative care with the WHOQOL-Bref (TR) Turk Pediatri Ars. 2021;56(05):429–439. doi: 10.5152/TurkArchPediatr.2021.20262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mutoh T, Mutoh T, Tsubone H et al. Impact of long-term hippotherapy on the walking ability of children with cerebral palsy and quality of life of their caregivers. Front Neurol. 2019;10:834. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madani B M, Al Raddadi R, Al Jaouni S, Omer M, Al Awa M I. Quality of life among caregivers of sickle cell disease patients: a cross sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(01):176. doi: 10.1186/s12955-018-1009-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sekioka A, Fukumoto K, Miyake H et al. Long-term outcomes after pediatric tracheostomy-candidates for and timing of decannulation. J Surg Res. 2020;255:216–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2020.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farida J P, Lawrence L A, Svider P F et al. Protecting the airway and the physician: aspects of litigation arising from tracheotomy. Head Neck. 2016;38(05):751–754. doi: 10.1002/hed.23950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dursun O, Ozel D. Early and long-term outcome after tracheostomy in children. Pediatr Int. 2011;53(02):202–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2010.03208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tolunay İ, Dinçer Yıldızdaş R, Horoz ÖÖ et al. Çocuk Yoğun Bakım Ünitemizde Trakeostomi Açılan Hastalarımızın Değerlendirilmesi. J Pediatr Emerg Intensive Care Med. 2015;2:61–64. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamayo G J, Broxson A, Munsell M, Cohen M Z. Caring for the caregiver. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37(01):E50–E57. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.E50-E57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Surender S, Gowda V K, Sanjay K S, Basavaraja G V, Benakappa N, Benakappa A. Caregiver-reported health-related quality of life of children with cerebral palsy and their families and its association with gross motor function: a South Indian study. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2016;7(02):223–227. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.178657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dobhal M, Juneja M, Jain R, Sairam S, Thiagarajan D. Health-related quality of life in children with cerebral palsy and their families. Indian Pediatr. 2014;51(05):385–387. doi: 10.1007/s13312-014-0414-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]