Abstract

Conflicts about money and finances can be destructive for both the quality and longevity of relationships. This paper reports on a descriptive analysis of the contents of financial conflicts in two samples. Study 1 examined severe financial conflicts in social media posts (N = 1014) from reddit (r/relationships). Eight themes were identified via thematic analysis: “unfair relative contributions” “who pays for joint expenses”, “job and income”, “exceptional expenses”, “terms of financial arrangements”, “discrepant financial values”, “one-sided financial decisions”, and “perceived irresponsibility”. Study 2 examined reports of more mundane financial disagreements recalled by married individuals (N = 481). Seven themes were identified via thematic analysis: “relative contributions”, “job and income”, “different values”, “exceptional expenses”, “mundane expenses”, “money management”, and “perceived irresponsibility”. In both samples, themes could be ordered along the dimensions of “concerns about fairness” and “concerns about responsibility”. The association of relationship outcomes (perceived partner responsiveness, couple satisfaction) with each theme and demographic predictors (income, relationship length, shared finances) were explored. Independent t-tests suggested that participants who recalled disagreements fitting the themes at the extreme ends of the two dimensions (“unfair relative contributions” and “perceived irresponsibility”) reported worse relationship outcomes. In contrast, participants recalling disagreements fitting the theme of “mundane expenses” reported better relationship outcomes.

Keywords: Money, finances, relationship conflict, thematic analysis, social media

Introduction

There are disagreements and conflict in any relationship. While money and finances are not the most frequent disagreement topic in relationships, it is one of the most persistent (Papp et al., 2009) and ultimately destructive type of conflict in relationships (e.g., Dew et al., 2012). There are many possible reasons a couple might disagree about money-related decisions and many possible issues to fight about. In the present paper, we propose a framework of themes of financial conflicts in relationships, based on a thematic analysis of a large sample of social media posts seeking relationship advice and a sample of recalled financial conflicts in married couples. The identified themes of financial conflicts in relationships link to previously studied predictors of relationship satisfaction and financial harmony, but also highlight gaps in existing research.

Frequency of financial conflicts

How prevalent are conflicts about finance and money issues in relationships? Finances were the primary reason for relationship conflict in 40% of disagreements reported among people in long-term relationships (Meyer & Sledge, 2022). The perhaps most informative study on frequency of financial conflicts to date followed 100 married couples over the course of 15 days, tracking and rating 748 conflict instances over this time (Papp et al., 2009). Conflicts about money constituted 18.3% of conflicts described by husbands and 19.4% of conflicts described by wives. Thus, money and finances were not the most frequent topic of conflict. However, money conflicts were more stressful and threatening for couples than other conflict topics (Dew et al., 2012; Papp et al., 2009).

Consequences of financial conflicts

Evidence for the detrimental effects of financial conflicts for relationships abounds (S. Britt et al., 2008; S. L. Britt & Huston, 2012; Dew, 2008; Dew et al., 2012; Dew et al., 2021; Jackson et al., 2023; Kelley et al., 2018; Kerkmann et al., 2000; Wheeler & Kerpelman, 2016). In a longitudinal study of married women spanning more than 25 years, women who reported arguing “often” about money in marriage were nearly three times more likely to divorce compared to those who “sometimes” or “hardly ever” argued about money (Britt & Huston, 2012). Financial conflicts also appear to be particularly detrimental compared to other conflicts in a large sample of couples from the National Survey of Families and Households (Dew et al., 2012; Wheeler & Kerpelman, 2016). Couples rated the frequency of disagreements about various topics in their relationship, such as chores, finances, time spent together, sex, and in-law relations. Only frequency of disagreements about finances and sex were significant predictors of divorce 5–7 years later. The link between financial conflicts and divorce remained significant even when controlling for objective financial well-being (assets, debt, income of the couple; Dew et al., 2012). In sum, financial conflicts are potentially destructive for both the quality and the longevity of relationships.

Reasons for financial conflicts

When relationship partners are having “money conflicts” (Papp et al., 2009), “financial conflicts” (Saxey et al., 2022a) or “disagreements about finances” (Dew et al., 2012; Morgan et al., 2021), what exactly are they fighting about? Information about the content of financial conflicts can be important to guide research towards understudied areas of financial conflicts. Information about how different financial conflicts might be grouped within larger themes may help understanding whether one conflict experience may generalize to adjacent experiences. For individuals in relationships, learning about the range of different types of conflicts may put their personal experiences in context and normalize experiences. Knowing different types of common financial conflicts might also help people identify and label their own experiences better. Thus, there are multiple benefits to knowing the content of financial conflicts in relationships. While research has yet to detail the content of financial conflicts directly, indirect evidence points to multiple financial variables that are linked to worse relationship outcomes and which may feature in financial conflicts between partners.

Financial Stress

One financial factor linked to relationship satisfaction are the financial struggles in the couples’ life (S. Britt et al., 2008; Kelley et al., 2018; Kerkmann et al., 2000; LeBaron et al., 2020; Totenhagen et al., 2018). Subjective financial stress among married individuals reduced not only the stressed individuals’ own perceived marital quality but also showed partner effects, where wives’ financial stress reduced their husband’s marital quality and vice versa (Kelley et al., 2018). Furthermore, daily variations in subjective financial stress predicted daily relationship satisfaction (Totenhagen et al., 2018). Thus, one type of financial conflict is likely attributable to struggling to make ends meet, perhaps due to unexpected expenses, income reduction, or recent unemployment. Partners might blame each other for losing income or emotions might run high due to financial stress. This reason for conflict might be particularly prevalent in times of economic adversity. Notably, financial struggles do not always spell trouble. In two studies, specific financial stressors (e.g., inability to pay bills, eviction) increased relationship commitment (Dew et al., 2018; LeBaron et al., 2020), as long as financial family support was present.

Spending behaviors

Another financial factor linked to relationship satisfaction is the partner’s spending behavior (Britt et al., 2008; Kelley et al., 2022; Li et al., 2020; Mao et al., 2017; Ross et al., 2017; Wilmarth et al., 2021). Perceiving the partner’s spending behavior as responsible was linked to greater relationship satisfaction (Li et al., 2020). Perceiving positive partner behaviors such as spending within a budget and investing for long-term goals were linked to better relationship satisfaction (Mao et al., 2017; Totenhagen et al., 2019; Wilmarth et al., 2021) whereas seeing the partner as ‘spender’ was linked to worse marital satisfaction (Kelley et al., 2022). Thus, partners might fight over specific financial decisions or general spending patterns they see as irresponsible or negative such as lack of budgeting or saving.

Organization of finances

Another financial factor linked to relationship satisfaction and commitment is the sharing of funds and decision-making power. Greater financial integration such as pooling finances as a couple has been linked to better relationship quality (Addo & Sassler, 2010; Gladstone et al., 2022; Kenney, 2006; Lim & Morgan, 2021; Steuber & Paik, 2014). This positive effect even occurs when experimentally assigned to pool financial resources in the lab (Gladstone et al., 2022). The benefit of joint finances has been primarily explained by perceived level of investment and the resulting commitment to the relationship. However, another factor might be that joint accounts remove potential conflicts over respective contributions to expenses – when resources are shared there is no need to argue over who pays how much and how often. Thus, some financial conflicts might be about the coordination of partners' contributions to joint expenses.

(Dis)similar values

Another financial factor relevant to relationship quality is the degree to which partners view money in the same way (Archuleta et al., 2013; Mao et al., 2017; Rick et al., 2011; Romo & Abetz, 2016; Totenhagen et al., 2019). Perceiving more shared financial values between the partner and the self (e.g., agreeing with statements such as “we have similar financial goals”) was correlated with current relationship satisfaction (Archuleta et al., 2013; Mao et al., 2017) and predicted better relationship satisfaction two years later (Totenhagen et al., 2019). In studies examining couple’s actual similarity on financial values such as saving or spending orientation (‘tightwads’ vs. ‘spendthrifts’), greater differences between partner’s saving orientation was linked to worse marital well-being, and more conflict over money (LeBaron-Black et al., 2022; Rick et al., 2011). Relatedly, in semi-structured interviews of 40 individuals in long-term, committed relationships an overarching struggle underlying people’s financial talk with their partners was about “money is everything” versus “money isn’t everything” (Romo & Abetz, 2016). Specifically, participants reported being at odds with their partner over different ideas of how much importance financial success has for one’s self-worth, or how money is prioritized over other goals such as relational well-being, or the extent to which each partner endorses materialism. In sum, shared financial values and a similar outlook on financial issues appears to be a distinct feature of financial harmony, and conversely, financial conflicts might arise from discrepant financial values and different outlooks on financial issues.

The Current Research

In the present research, we examine the content of financial conflicts in relationships. We seek to answer the research question: When couples fight about money, what do they fight about? Prior research has indirectly identified a number of possible reasons for couple’s disagreements about finances: financial stress, irresponsible spending behaviors, organization of finances (joint vs. separate), and dissimilar financial values. However, our review of the literature did not show any studies that examined the content of financial relationship conflicts inductively. To address our research question in a bottom-up, descriptive design, we conducted qualitative analyses of two samples capturing financial conflict discussions. One sample captured relatively more severe conflicts and provided a large range of conflict experiences: In Study 1, we conducted a thematic analysis of social media posts about financial conflicts on a forum dedicated to relationship advice. In a second sample, we captured more mundane, minor, financial conflicts: In Study 2, we recruited married individuals and asked them to recall a recent financial conflict with their partner. We coded these recalled conflict descriptions qualitatively and also examined their link with other self-reported relationship variables correlationally.

Study 1

Given that conflict situations are an irregular occurrence (Papp et al., 2009) and financial conflicts are just a subset of these situations, it is a challenge to find a sufficiently large and diverse sample of different financial conflicts among relationship partners. To this end, we drew our data from a large diverse pool of financial conflict descriptions existing on social media advice forums. Specifically, we conducted a thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2012; Clarke et al., 2015; Terry et al., 2017) of posts on r/relationships of the social media page reddit. This particular forum specializes in relationship advice and allows anyone to post descriptions of their relationship problems, soliciting anonymous advice from other forum users. The posts analyzed in this study thus represent spontaneous financial conflict descriptions from people struggling with a conflict in their relationship. Other work has analyzed the content of reddit posts (Apostolou, 2019; Kimiafar et al., 2021) and descriptions on this social media page provide rich detail and information, as well as having the advantage of candidness due to the writer’s anonymity.

Method

Data retrieval

The data was collected using an original Python script that was connected to an open-domain access token for Reddit API (application programming interface). The search parameters of the script were restricted in several ways. First, the search engine was set to only collect posts from the “r/relationships” subforum of the Reddit website. In terms of query keyword, only posts that included the words “money” or “finance” keywords in their text were collected from the overall pool of posts available on the forum (no derivatives of these words were included as keywords). Posts were set to be collected between midnight (12:00:00) on January 1, 2021, to midnight (23:59:59) on December 31, 2021. Additionally, English was set as the primary language of communication, therefore no posts in any other languages were recorded.

Data screening

The total number of posts retrieved from r/relationships was 8,673. As this was an unmanageable number of posts to individually screen, we considered only those posts that received attention by other users, i.e., had garnered at least 10 comments (n = 3,488). Selecting for posts that received more comments ensured that we focused on posts that described an issue comprehensively and intelligibly (see Kimiafar et al., 2021, for a similar selection procedure). The average number of comments for the retained posts was 52.70 comments (SD = 80.53). These 3,488 posts were read in full by one of three coders and were screened for two eligibility criteria: Posts were included if they were about a current romantic relationship (posts about ex relationships, hypothetical future relationships, or non-romantic relationships were excluded) and if they were about a financial conflict (posts that were not about a financial conflict but mentioned money or finances coincidentally were excluded). A total of 1,014 posts were deemed eligible and formed the set of posts used in the thematic coding. These posts represent a total body of text comprising 571,070 words (average length of posts was 565.18 words, SD = 425.19).

Data coding

First, two researchers read all 1,014 eligible posts and collected a list of unique elements occurring across the described financial conflicts in relationships (i.e., “codes”). Coders did not consider existing research in their initial code compilation and took a completely data driven approach in identifying codes. This list comprised 47 initial codes. Posts were then coded using the software Nvivo. Posts were coded on a sentence-level, where any information pertaining to the poster’s financial conflict situation was assigned to the relevant code. If a sentence was deemed relevant to multiple codes, it was coded to multiple codes. Information not pertaining to a financial conflict was not coded.

In a first calibration step, three coders coded 100 posts using the initial code list. In this first calibration process, after a discussion among coders, three codes were added to the list and seven codes were folded into other codes. Several code descriptions were clarified via discussion between coders. In a second calibration step, two coders both coded 100 additional posts using the updated code list, followed by a discussion. In this calibration process, one code was added to the list and two codes were folded into other codes. After these calibrations, two coders proceeded to code the remaining posts, while continuing to discuss codes. In this coding process, two additional codes were found to be necessary; another two codes were combined into one. The final codebook included 41 codes. See Table 1 for a list of codes along with examples. Full data is available at https://osf.io/wy9tj/. As a measure of interrater reliability, Cronbach’s Kappa was computed for each code within Nvivo, showing very high reliability (agreement between coders was larger than .95 for all codes). However, this reliability estimate may be inflated by the fact that Kappa is calculated word-by-word in Nvivo and only portions of the text for each reddit posts were relevant and were coded, thus leading to high agreement on uncoded text.

Table 1.

Themes, Codes, and Examples, sorted from mostly about concerns about responsibility to mostly about concerns about fairness.

| Theme | Codes | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived irresponsibility (21.4%) | Lack of planning for the future by one partner (2.6%) | “I feel stuck, and he has absolutely NO future plan for us to 1 day afford more. If I press too much, he just says things like “well we won’t have kids then”. I told him I am happy to accept our situation but we have to figure out how to live in our means. He won’t budge.” |

| Downward trajectory in which the partner is anticipated to become increasingly irresponsible (2.3%) | “I’m afraid that years down the road, I will unintentionally hold some sort of resentment/bitterness over my husband’s financial circumstances.” | |

| Budgeting disagreements on how or whether to budget (1.2%) | “We did take a couple hours last month to outline a preliminary budget. Since then, she resists talking about it at all. I’ve been emailing her weekly expense reports to keep her informed because she won’t log into mint and check.” | |

| Personal purchases that are seen as unnecessary by one partner (3.5%) | “I tell him it’s skincare and hair care but he just laughs and tells me it’s marketing and wasting money. I don’t spend his money I buy it with my money.” | |

| Impulse purchases that were unplanned and seen as irresponsible (4.2%) | “One day we had a huge fight when he spent his entire stimulus check on bitcoins. That was the red flag but I thought he wouldn’t do something that stupid again in future.” | |

| Not saving as intended or not enough (1.2%) | “She saved up about $3000 in cash and I was super excited to move it to the savings account for our house, but she blew it ALL on expensive Christmas gifts and then went through my Christmas cards from my parents, took $400 and spent it on some hair accessories that she never even used. That really pissed me off and I was hardly able to even talk to her for a day or two.” | |

| Debt acquired before or during the relationship (3.3%) | “However, when our broker started to ask for financial information, it turned out that my husband hadn’t done his taxes in several years, and had far more debt than he had let on. I was furious!” | |

| Broken promise about a financial obligation (2.0%) | “He asked me yesterday to remind him to transfer the money for it to my account so I did and I woke up this morning to find he didn’t do it, I had to miss my appointment.” | |

| Gambling and money spent on drugs or alcohol (1.8%) | “I was going through our bank accounts and found that she has been spending hundreds of dollars on an app on her phone. We’d had that problem a few years ago, and she promised she had it taken care of and wouldn’t let that happens again.” | |

| One-sided decisions (6.9%) | Left out of the loop about financial decisions (1.4%) | “I confronted him with this money-issue yesterday, and today he came clean and told me the reason why he has been asking for money, and been reluctant to use his own is because he has been saving up for us to buy a home, and has been keeping this a secret for me, because it was supposed to be a surprize. So essentially he has been saving both his own, and my money, without asking me.” |

| Hiding or lying about expenses or income (4.1%) | “I feel like I can’t trust her anymore-- both financially, and in general, since she continued to lie about this until it ballooned to the point where we are seriously looking at starting from square 1 for our wedding fund so that she’s not getting destroyed by interest charges every month.” | |

| Sex work (1.5%) | “This morning she confronted me that during our rough patch she received advice from her friends to sell nudes to get the money we needed. I was very shocked and disappointed to hear.” | |

| Different financial values (7.5%) | Unequal financial background (e.g., socioeconomic differences) (1.3%) | “We are both from very different families, I grew up in a working class family in northern england where my parents instilled a sense of care into everything that we owned, mainly because we didn’t have a lot of money and if something broke my parents wouldn’t always be able to replace it. (…) On the other end my partner is from I guess a middle class family where, although her parents have divorced, they aren’t short of money and never have been.” |

| Different priorities in spending (6.9%) | “He is very money oriented, always talking about how much he’s earned this week from his work bonuses (which can go up to thousands) and how much he’s saved etc. (…) I barely buy myself anything but I don’t really need anything. I’m happy with a few art supplies.” | |

| Different savings attitudes regarding how much or how saving should occur (1.5%) | “The difference in this situation has surprised me though, as it’s made me realise we have two completely different mindsets financially - I would never have let all of my money go into a project - I set my boundaries even now and a majority of my savings I don’t even consider as there for use, as I see it as my future & flexibility fund" | |

| Job or income (19.1%) | Income loss or not enough income by one partner (3.8%) | “He makes quite a but less than me but he is now thinking about quitting his job and even settling for less money. I’m taking like 13 an hour. This really really bothers me because education and having a career is one of the top things I looked for in a partner.” |

| Unequal income between partners creating tension (5.6%) | “Additionally he is really sensitive around matters regarding my job. I’m a software engineer and make considerably more money than he does which isn’t a problem for me and I try to make sure I’m not emasculating him or ever holding it over my head.” | |

| Strain, unexpected expense, subsistence struggle (1.5%) | “It’s been a stressful month. I’m in the most difficult class of my nursing program. I’m not working a lot. He’s been working harder to make up for the money loss. We’re pretty broke right now. Add his employer’s insurance not kicking in on time for fertility-related appointments, my meltdown relating to that (…), and a couple petty arguments and it’s been rough. | |

| Embarrassment about partner’s job because of its low social status or low earning potential (1.4%) | “I don’t even feel comfortable introducing him to my friends and family: (i feel like I cant fully commit and be happy about our relationship (even though its definitely the best ive ever had) because I’m not sure if I want to share my future with him. I don’t want to struggle anymore and want someone who’s ready to do this with me and be on the same page.” | |

| Impending or desired career changes that might put the household’s finances in jeopardy (2.6%) | “My wife told me that she wanted me to stay home and take care of our daughter and be a stay at home dad. It does sound nice being able to stay home with the baby, but I am used to going out and working.” | |

| One partner failing to get a job, seen as not trying hard enough (2.5%) | “He has a part time job which is slow a lot of the time. He says he’s looking for work but honestly not hard enough. He wants to find a job that pays him a certain amount of money.” | |

| One partner rejecting work or a job completely (2.0%) | “We agreed that I would make more money so if/when we had kids he would stay home so we wouldn’t need to pay for day care. But until then he would get a part time job to help save for our future. (House, kids, retirement etc) The issue is we don’t have have kids and he still stays at home and games all day long with no job.” | |

| One partner discourages other partner from taking a job or extra work (0.8%) | “I’m just tired of feeling like we’re living paycheck to paycheck and I don’t want to do this anymore, but he also doesn’t want me working on the weekends.” | |

| Exceptional expenses (9.1%) | Car purchase or lease (1.3%) | “I bought a new car to fit the family better which I guess technically is a luxury vehicle. He got annoyed that I had a nice new car (...) He makes back-handed comments about my car all the time, saying things like “for 70K that car should be picking up the kids for you” etc.” |

| House purchase or committing to rental contract (1.9%) | “My wife desperately wants to buy this house. It’s actually a historic property that used to belong to her family and carries some emotional weight, so I do understand. But the problem is, it’s out of our budget. The sticker price alone would be a stretch, but it’s also not in good shape and would be expensive to maintain.” | |

| Other one-time joint expense (wedding, vacation, moving in) (3.4%) | “But really, her ideal situation is we elope and have a party after. While I want the whole 9 yards, large wedding, bachelor/bachelorette party. (...) She’s (very politely) told me she is really not willing to do that. (…) she thinks it’s a waste of money.” | |

| How to deal with a windfall of money (e.g., invest it, save it, spend it) (1.1%) | “We recently came into a windfall and are setting up trusts for our children and grandchildren. (…) We’re all on agreement on most things but he insists that the trust only applies to our biological grandchildren and not any step grandchildren or adopted grandchildren. When I insisted that all the grandchildren be treated equally, he then said then they get nothing and we donate the money.” | |

| Terms of financial arrangement (8.0%) | Dissatisfaction with the exchange-oriented nature of financial arrangements (1.6%) | “I’m so unhappy and so miserable because it just feels like we are taking tabs. We never do anything freely or out of love because something is always expected in return. It’s just tiresome.” |

| Lending/Borrowing terms between partners (1.0%) | “At this point, it’s not really about the money to me as much as it is about feeling taken advantage of. I Could have spent the $3000 on anything but decided to help her out, yet she doesn’t prioritize paying me back because she knows I don’t necessarily “need” it.” | |

| Prenup/Postnup (1.7%) | “He wants to sign a prenup before we get married and I don’t. He said he wants to protect what’s “his” but the way I see it, I’ve supported him through everything, from when we were two young kids working part time jobs to having careers.” | |

| Whether finances should be combined or kept separate (1.7%) | “My (28f) husband (27m) is very set on having separate finances. I Never agreed to it from the beginning of our relationship. But since he was unwilling to budge or find a middle ground, I gave up and kept things as is. We’re a few years into marriage and quite frankly I’m over this feeling of living with a roommate” | |

| Accepting help or giving help to family (2.0%) | “I’ve been thinking about sending my parents some of the money I make every month, so that they can live a more comfortable life. It’s not much (150-200$) but should help them to buy other stuff besides food as well. My girlfriend however is pretty sad about it and does not want me to spend money on my parents. She thinks unless they do not specifically ask for money, I should not send them any. She rather wants me to spend the money on us (for better food, clothes, furniture, etc)” | |

| Harmful withholding of funds (0.3%) | “For example right now my phone has been broken for 2 months with a severely cracked screen and my glasses were stolen out of my car about 3 months ago. (…) I have asked for money for these two things but I’m always told money’s tight or wait till my next paycheck but it never happens. He refuses to use banks so I can’t see what’s coming and going from the money he makes.” | |

| Who pays? (13.3%) | Rent/mortgage contributions (e.g., equal or proportional to income?) (5.2%) | “My boyfriend is asking me to pay half the cost of the mortgage because technically we’re two people living in this house so we should split it, even if we aren’t using the second room. He makes way more than me (like almost twice more) so I don’t feel great about the 50/50 split, and I don’t even own the house so I don’t want to pay that much for a place I don’t even own.” |

| Who should pay for relationship-enhancing activities such as dates (3.0%) | “I told her enough is enough, I would not tolerate this anymore, especially paying for meals I barely get to eat. Either she starts splitting the bill all the time or no more eating out.” | |

| Ongoing joint expenses (bills, food, pets, children) (4.5%) | “Whenever he goes out with friends I resent it because I feel like I could use the money he spends out on maybe a small bill around the house. I Feel like I get stuck paying all the bills for the house including my own personal bills and really doesn’t give me an opportunity to save money for my future.” | |

| Relative contributions (14.8%) | Lack of reciprocity in household contributions or desired purchases between the partners (5.6%) | “So during the entirety of our marriage I have always worked hard to support my wife and my son because I want to give them everything I can. I supported my wife while she was finishing school by taking on more of the bills, buy her things, and help her sometimes with her car or any other personal bills of hers even if it would put me under a lot of stress. What I’m having a hard time understanding is how come that kind of support isn’t mutual. My wife has been getting pretty lucky this year with coming up on money from her jobs but never just gives me some of that money or ask me if I could use such and such amount to help with any of my bills.” |

| Lack of unsolicited financial help, partner has to be reminded or cajoled to contribute (0.9%) | “She’s never offered to help me with payments or the insurance and she’s brushed off the conversation whenever I’ve asked her about adding her to the insurance and splitting it.” | |

| Imbalance in chores and financial contributions to the household (2.1%) | “He is also overly concerned with finances and expects us to split costs with everything, but refuses to help me with chores or anything of the sort.” | |

| Receiving too few or cheap gifts, a sense of being under-benefitted (2.1%) | “It seems like when he’s buying me gifts, his first thought is what is the cheapest thing I can get her? His gifts often break and are not what I would buy for myself but in a bad way” | |

| Receiving too many or overly expensive gifts a sense of being over-benefitted (1.3%) | “Now I know that he is someone really into brands, and Gucci and whatever, and that’s fine on him, but not on me. I told him I’m not a materialistic person, and that sentimental gifts are what bring me happiness and make me feel loved. (...) He agreed but it seemed like a “I’m just saying this to shush you but I’m still going to buy the expensive things”.” |

Note. The frequency percentage for each code refers to the percentage of coded text excerpts rather than percentage of reddit posts. Posts mentioned multiple reasons for fighting about money and one post might include multiple text excerpts assigned to the same or different codes. If a text excerpt was coded to two codes under different themes, it was counted in each theme. If a text excerpt was coded to two codes under the same theme, it was only counted once per theme. Therefore, percentages for code frequency do not add up to the percentage for the theme.

Across all steps of the coding process, an additional 26 posts were deemed ineligible upon closer reading (e.g., because they described conflicts that were not truly financial in nature or were about the form rather than the content of the discussion such as emotional escalation) leading to a total of 988 coded social media posts about a financial conflict between romantic relationship partners.

Thematic analysis

In a discussion among all three researchers, the codes were collapsed into nine themes. In a thematic review, two researchers read through all coded data extracts assigned to each theme, to determine if these data extracts formed a coherent, consistent and distinctive pattern pertaining to the theme. In this process, two themes were folded into one theme due to high overlap, resulting in eight themes. In this thematic review, coders judged that the data extracts fit the eight themes well. The list of themes can be found in Table 1. Further discussion suggested that these themes could be ordered within the dimensions of two overarching themes of “concerns about fairness” and “concerns about responsibility”.

Researcher bias

Coders were White women of middle-class Western background. One of the coders was familiar with some existing research on finances and relationship research in a general, the two main coders were naïve to existing theories and research about finances.

Results

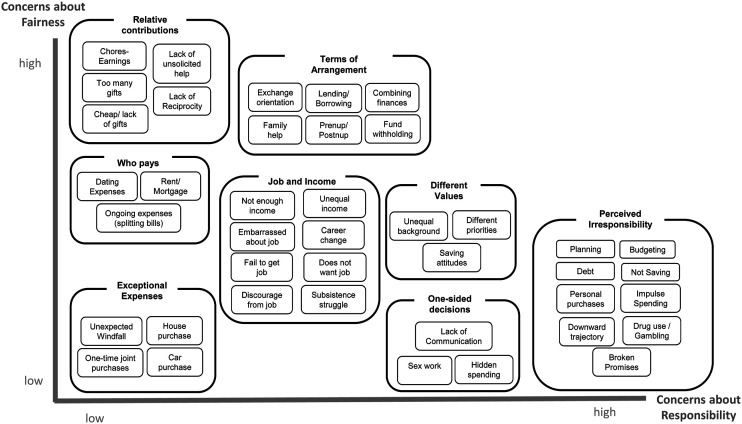

Themes and Codes are depicted in Figure 1 and described in Table 1. The eight themes each included several codes, listed in Table 1 along with examples. The frequency of text excerpts pertaining to each theme and code (i.e., the number of statements coded to the theme or code) are listed in Table 1. Themes were ordered along two dimensions: one dimension capturing “concerns about responsibility” of the partner’s financial decisions and another dimension capturing “concerns about the fairness” of financial decisions in the relationship. By far the most frequently mentioned theme was “perceived irresponsibility” by the partner (21.4% of text excerpts coded to this theme). This theme was linked to the theme of conflicts about “one-sided financial decisions” and the theme of “different financial values” between partners, with conflict description frequently touching on both of these themes. The second most frequently mentioned theme was about “jobs or income” (19.1% of text excerpts coded to this theme), which pertained to the overarching theme of irresponsibility to a lesser degree and also sometimes referenced the theme of fairness (e.g., when one partner’s lack of income impinged on the household’s financial situation). The third most frequently mentioned conflict theme was about perceived unfairness in “relative contributions” to the household (14.8% of text excerpts coded to this theme), which often co-occurred with the theme about “who pays” for joint expenses and “terms of financial arrangement”.

Figure 1.

Themes and Codes of Financial Conflict in a Social Media Sample (Study 1).

Discussion

A thematic analysis of social media posts about financial conflicts showed that the content of these posts seeking advice or describing struggles could be organized along two overarching dimensions – concerns about fairness and concerns about responsibility – and included eight themes and 41 unique conflict topics within these themes.

One advantage of examining spontaneous unsolicited financial conflict descriptions in anonymous relationship advice forums is the diversity of conflicts and the diversity of ‘participants’. It was evident from the descriptions that individuals were in vastly different life situations, relationships, and social economic situations. This diversity also prevents generalizability of findings to specific groups – some themes might only be relevant to dating couples who do not live together, some might only be relevant to long-term married couples with children. In this sample, the demographic make-up of the sample is unknown and cannot be linked to specific themes. An additional limitation to generalizability is that social media posts might specifically select for ongoing conflicts in a relationship that remain unresolved, and thus selects for more severe financial conflicts that relationship partners feel they cannot discuss with real-life friends or family or solve on their own. Thus, these types of conflicts might differ from more mundane and minor financial conflicts.

Study 2

The second study focused on more minor, mundane financial conflicts. This study also assessed demographic make up of participants, to allow for a comparison of themes with regards to relationship characteristics and conflict characteristics. This study elicited recalled financial disagreements in the recent past from one member of the couple. Recalled conflict descriptions were coded independently from the themes found in Study 1. This inductive rather than deductive process allows for the identification of different themes of conflict in this second sample. However, in an additional analysis, we also coded all disagreement descriptions according to the 41 codes and eight themes identified in Study 1, to examine applicability of these themes to this entirely different context of financial conflicts. When using the previously identified coding scheme, all themes but not all codes were represented in the data. This analysis is reported in Table OS1 in online supplements: https://osf.io/f7g2s.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited through Mturk (Huff & Tingley, 2015) from U.S. and Canadian MTurk workers for a larger study on financial attitudes and were compensated with US$1.5 (approx. $6 hourly rate). Data were collected in May to June 2022. Several precautions were taken to ensure data quality (participants had passed Cloudresearch quality checks, completed a reCAPTCHA check before beginning the study). To ensure that participants were in a committed relationship, only workers who were registered in the Cloudresearch system as ‘married or common-law’ were eligible to participate. The initial sample included 596 participants. Of these, 116 did not report a recent financial conflict (33 did not write anything, 13 reported that they never have disagreements about finances, 13 reported a financial discussion that was not a disagreement or conflict, and 57 wrote about a conflict that was not about finances) and were excluded. The eligibility was determined by two coder’s ratings of the descriptions (agreement was very high, k = .85, p < .001).

The final sample (N = 481) included 206 men and 275 women. The majority reported a heterosexual orientation (95.4% heterosexual or straight; 1% lesbian or gay, 3.3% bisexual). In line with Cloudresearch-based eligibility requirements, 96.7% were married, 1% reported being engaged, 2.3% reported they were dating. We retained these nonmarried participants as they were in long-term relationships (range: 1–8 years, M = 3 years) and were living together, thus they fit our requirement of being in a committed common-law relationship. Across the fukk sample, relationships had lasted between 11 months to 56 years (M = 16 years, SD = 10.8 years; Md = 13 years), 73.2% of the sample had children and 98.3% were living together. Participants were between 19 and 78 years old (M = 43.27 years; SD = 11.71, Md = 40) and the sample was predominantly White (80.7% White 7.5% Black or African-American, 6.2% of Asian decent, 3.7% Hispanic). Frequency distributions for age and relationship status are available in online supplements: https://osf.io/f7g2s. No information on disability status or social class was assessed. Income ranged widely but the combined income between the self and the partner was, on average, in the $90,000 to $110,000 bracket (which is similar to the 2019 US median for married couple households: $96,930). About half of the participants (59.7%) reported fully joint finances, and 40.3% reported separate or partly separate finances.

Procedure

Participants first completed a demographic survey and the 16-item Couple Satisfaction Index (Funk & Rogge, 2007) on 6-point scales. Items were averaged into a Couple Satisfaction Index (α = .96; M = 4.76, SD = .98). Participants were instructed to recall and describe a recent financial disagreement (i.e., “Now please think of a recent disagreement with your partner where you were discussing financial decisions and money habits. Please describe the disagreement briefly here”). On average, participants wrote 31.79 words (SD = 23.98). After the disagreement description, participants reported how responsive and understanding they felt their partner was during the financial disagreement (4 items, Van Erb et al., 2011, “During the discussion about this financial topic… - My partner was understanding toward me.”, “I felt supported by my partner”, “I felt I was valued in our relationship”, “My partner treated me with respect”) on a scale from Not at all (1) to The whole time (5). Items were averaged into an index of responsiveness during the conflict discussion (α = .95; M = 3.74, SD = 1.15). No other questions about the disagreement description were included in the survey. Full survey and data are available at https://osf.io/wy9tj/.

Data coding

First, two naïve raters unfamiliar with the themes and codes identified in Study 1, and two raters involved in Study 1’s thematic analysis read all 481 disagreement descriptions and collected a list of unique elements occurring across the described financial disagreements. Rater’s code lists comprised 14, 22, 25, and 28 initial codes respectively. There was a large overlap in initial codes: 19 codes were identified independently by at least three of the coders. Via discussion, these codes were compared and a final code list of 23 codes was created. See Table 2 for a list of codes along with examples. Two raters then rated which code(s) applied to each disagreement description. Multiple codes could be applied to any one conflict description. Agreement was good: Across all disagreement descriptions, the two raters assigned the identical code (out of 23 possible codes) to 76% of the descriptions. Over the course of this coding step, 48 additional disagreement descriptions were excluded because the description did not appear to be an actual conflict, or even a disagreement, but rather a discussion (e.g., “We were talking about it yesterday. There were a few layoffs at his work and we talked about cutting back a bit on spending, to be on the safe side.”). By excluding these additional descriptions, we ensure that all included descriptions describe an actual financial disagreement.

Table 2.

Themes, Codes, and Examples, sorted from mostly about concerns about fairness to mostly about concerns about responsibility.

| Theme | Code | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Relative contributions (14.5%) | Splitting recurring bills (argue about who should pay how much, using personal vs. joint accounts) (9.6%) | “I told my husband today that I’m unable to pay for our groceries as I have been because of losing food stamp benefits and increased prices. He did not offer to step in and help even tho he has four times the spare cash monthly as I do.” |

| Income: Contribution ratio (argue about relative income to contribution to expenses; fairness of contributions) (3.2%) | “I recently took a reduction in work hours resulting in a large pay cut. My partner makes substantially more than me. We are disagreeing over how much he should be contributing as I am struggling financially. This has been our biggest problem in our marriage. It has always been this way and is now worse.” | |

| Gifts (Who is responsible for purchase, decides price; within and beyond relationship) (2.3%) | “We were discussing the cost of a present. I thought that fifty dollars would be enough, but she insisted on one hundred dollars. Her views prevailed.” | |

| Job and income (8.8%) | Job issues (getting/leaving job, joint business trouble, taking time off work with loss of income) (5.5%) | “My husband got his hours cut at work and if he doesn’t work, he doesn’t get paid. He spends money all the time on wasteful things and I asked him to figure out how to make more money because he spends more than he makes. He got very upset with me and said that all I care about is money.” |

| Financial struggle/strain (making ends meet) (4.1%) | “Phones being cut off due to not paying the bill, having to borrow money to make rent, owing friends and family money.” | |

| Different values (24.2%) | Family (how much or whether to give financial help) (3.9%) | “We had a disagreement about whether or not to loan some money to a family member. He wanted to give the loan but I did not think it was a good idea.” |

| Different values (personality differences in how spending is approached, different priorities) (20.1%) | “We just received our income tax return, my partner is seeing the money as play money while I’m really wanting to put some into savings.” | |

| Exceptional expenses (29.3%) | Housing/Moving (House purchase/Sale) (6.4%) | “I want to save money longer without spending it so we can buy a nicer home. She wants to buy a new home now, before we really can afford it.” |

| One-time purchases (joint benefits; furniture or other home or shared items) (13.0%) | “Disagreed about a major purchase. Partner wanted higher-end frivolous item. I wanted basic needs equivalent.” | |

| Travel/Vacation (whether to go, how much to spend) (9.6%) | “My partner wants to go to Israel for a two week tour of the holy land. It is very expensive and we have many other more important expenses.” | |

| Unexpected expenses (how to handle unexpected expenses such as health care costs) (1.1%) | “My husband has stage 4 cancer and cannot work and we pay a lot of money out of pocket for his medical marijuana to keep him eating. We cannot afford that on just my disability alone and we often talk about the pros and cons of coninuting to use so much money on it.” | |

| Mundane expenses (24.5%) | Children’s expenses (how much to spend or whether expenses are necessary) (7.8%) | “Our daughter has her 13th birthday coming up soon and we had a disagreement on what should be spent on this party.” |

| Car-related expenses (who should pay for car/gas payments, new car) (10.7%) | “A few weeks ago, we discussed whether to purchase a second car for the home. I think it is necessary but my partner did not agree with me.” | |

| Home improvement (whether or how much to spend on home improvements such as renovation) (7.1%) | “My wife wants to have a propane insert installed in our living room while I think that money would be better spend on repairing the roof of our garage. Her and I disagree and we haven’t come to a decision on it yet.” | |

| Money management (16.9%) | Investments (how to and whether to invest) (4.1%) | “The only thing we’ve recently disagreed with about our finances is that she keeps buying cryptocurrency and i’m not convinced it’s a good long term investment. She’s less risk averse than I am financially so she’s more comfortable investing in less traditional areas.” |

| Planning for the future (argue about retirement planning, future family plans, what to save for) (3.2%) | “The only disagreements we have nowadays is a recurring disagreement over the fact that I want to save more money towards retirement than I probably need to. She understands that I am not just on track to be able to retire in less than 10 years, but I am actually far ahead of the goal I set for myself 20 years or so ago. She would like to save less now and begin to spend more, but I’m not comfortable with the idea yet.” | |

| Budgeting (staying within the budget, making a budget) (9.8%) | “We had a disagreement about how we have been spending money recently. I Create a budget based on each paycheck, and we have been exceeding the budge frequently lately.” | |

| Perceived irresponsibility (39.3%) | Fun/Personal purchases (argue about extent of or necessities of personal spending) (16.0%) | “I told her repeatedly that we were out of funds until my next paycheck. She insisted on scheduling an hair stylist appointment, despite me having no way to pay for it” |

| Impulse spending (spending beyond means or wasteful spending) (6.2%) | “We argued on the buying certain items that were wants more than needs.” | |

| Saving (argue over importance and extent of saving) (9.6%) | “He always pays his share of bills, but I am always the one to be the saver for emergencies. We have discussed the importance of him having a savings, but the conversation never goes anywhere, to my frustration.” | |

| Debt (argue over how to pay off debt, including credit card bills) (6.6%) | “I wish he would put more effort into paying off student loans. Or I wish he would take care of things faster. But we are generally on the same page. I just feel like sometimes he procrastinates” | |

| Lack of communication (hidden or not discussed purchases, shutting down conversations) (7.5%) | “She bought several things without running it by me and we didn’t have enough money in the bank.” | |

| Alcohol/Drugs/Gambling (1.6%) | “He claims I spend over $400/month on cigs and I should cut down. But when I tried to say he spends almost the exact same on alcohol, he denied he spent even close to that amount, which is a lie.” |

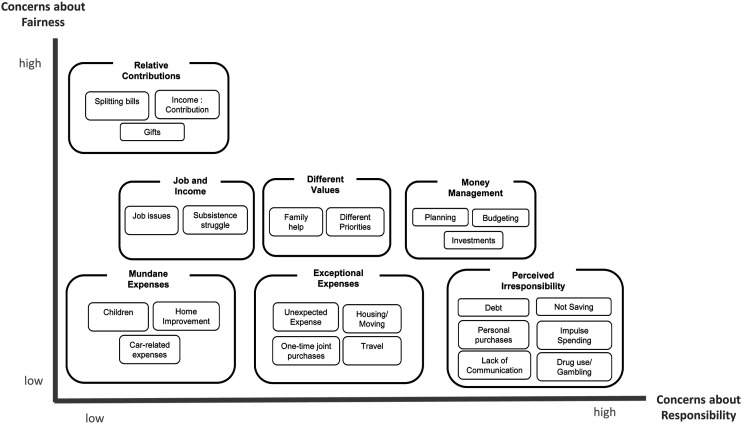

Next, codes were collapsed into larger-order themes. Seven themes were created in discussion among coders that aggregated the codes (Figure 2). As in Study 1, two overarching themes of “concerns about fairness” and “concerns about responsibility” organized the themes. Compared to Study 1, three themes did not emerge in this study: The theme of “who pays” did not emerge in this analysis, with related codes being folded into “relative contributions” and the new theme “mundane expenses”. The theme “terms of arrangement” was not present in Study 2 though some conflicts touched on codes included in this theme (Family help), which were folded into “different values” as the conflicts described therein concerned fundamental philosophy clashes. The theme “one-sided decisions” was not present in Study 2 though some conflicts concerned content included in this theme (Hidden Finances, Lack of Communication), which were folded into perceived irresponsibility”. Finally, two new themes emerged in this study: “mundane expenses” and “money management”, both of which included disagreements about minor day-to-day financial decisions.

Figure 2.

Themes and Codes of Recent Financial Disagreements in a Married Sample (Study 2).

We calculated weighted Kappas to examine the interrater reliability for each theme. Interrater agreement was substantial for “relative contributions” (k = .62), “exceptional expenses” (k = .74), “mundane expenses” (k = .78), and was on the high end of moderate for “perceived irresponsibility” (k = .58), “money management” (k = .59), “job and income” (k = .59), and was lowest, but still moderate, for “different values” (k = .41).

Results

Themes and Codes are depicted in Figure 2 and described in Table 2. The themes each included between two to six individual codes. The frequency of themes and codes are listed in Table 2 and are based on the number of disagreements that were coded as referencing each theme by either one of the coders.

We next examined whether themes of financial disagreement were associated with relationship outcomes. For each theme, we compared perceived partner responsiveness and overall relationship satisfaction between disagreements coded to the theme with disagreements not coded to the theme (see Table 3 for Means). Participants who recalled financial disagreements coded to the theme of “relative contributions”, at the high end of the dimension of concerns about fairness, reported marginally less perceived responsiveness, t (76.38) = −1.76, p = .083, d = .28, and less couple satisfaction, t (75.57) = −2.17, p = .033, d = .35. Participants who recalled financial disagreements coded to the theme of “perceived irresponsibility”, at the high end of the dimension of concerns about responsibility, reported less perceived responsiveness, t (340.38) = −2.31, p = .011, d = .23, but no less couple satisfaction overall, t (353.04) = −0.42 p = .676, d = .04. Participants who recalled financial disagreements coded to the themes e expenses”, “different values”, or “money management” did not report more or less responsiveness or couple satisfaction, all ps > .05. Participants who recalled financial disagreements coded to the theme of “job and income” reported no more or less perceived responsiveness, t (41.75) = −1.59, p = .119, d = .32, but reported less couple satisfaction overall, t (40.68) = −2.50, p = .017, d = .56. Finally, participants who recalled financial disagreements coded to the theme of “mundane expenses” reported more perceived responsiveness, t (194.38) = 2.02, p = .045, d = .22, and more couple satisfaction overall, t (216.30) = 2.42, p = .016, d = .24.

Table 3.

Relationship outcomes by financial disagreement theme (Study 2).

| Theme | Theme present in financial disagreement description? | Perceived partner responsiveness during disagreement | Couple Satisfaction Index | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Relative contributions | Present (n = 63) | 3.36 | 1.37 | 4.45 | 1.18 |

| Absent (n = 370) | 3.68 | 1.11 | 4.79 | 0.93 | |

| Job and income | Present (n = 38) | 3.30 | 1.39 | 4.25 | 1.30 |

| Absent (n = 395) | 3.67 | 1.12 | 4.79 | 0.92 | |

| Different values | Present (n = 102) | 3.52 | 1.16 | 4.66 | 1.03 |

| Absent (n = 331) | 3.67 | 1.15 | 4.76 | 0.96 | |

| Money management | Present (n = 73) | 3.85 | 1.06 | 4.85 | 0.79 |

| Absent (n = 360) | 3.59 | 1.17 | 4.72 | 1.01 | |

| Mundane expenses | Present (n = 106) | 3.82 | 1.07 | 4.92 | 0.82 |

| Absent (n = 327) | 3.57 | 1.17 | 4.68 | 1.01 | |

| Exceptional expenses | Present (n = 127) | 3.74 | 1.10 | 4.83 | 0.88 |

| Absent (n = 306) | 3.59 | 1.17 | 4.70 | 1.01 | |

| Perceived irresponsibility | Present (n = 170) | 3.47 | 1.20 | 4.76 | 0.99 |

| Absent (n = 263) | 3.74 | 1.11 | 4.72 | 0.96 | |

Note. Perceived Responsiveness measured on a 5-point scale. Couple Satisfaction measured on a 6-point scale.

Next, we examined whether demographic characteristics were associated with specific themes of financial disagreements. In logistic regressions, we entered relationship length, couple income, and joint finances (0 = partly or fully separate; 1 = fully joint) as predictors and each of the seven themes as outcome, respectively. Across all seven logistic regressions, only the models predicting “relative contributions”, “job and income”, and “different values” were significant (See Table OS2 in online supplements [https://osf.io/f7g2s] for all regression coefficients). Specifically, higher couple income predicted less presence of the theme “relative contributions”, B = −.12, SE = .04, Exp(B) = .89, p < .001, and less presence of the theme “job and income concerns”, B = −.15, SE = .05, Exp(B) = .86 p < .001. Relationship length predicted more presence of the theme “different values”, B = .002 SE = .001, Exp(B) = 1.00, p = .011. Joint versus separate finances did not predict any of the themes, however, replicating prior research (Addo & Sassler, 2010; Gladstone et al., 2022; Kenney, 2006) those with joint finances reported better relationship outcomes (perceived responsiveness: t (346.20) = 4.07, p < .001, d = .41; couple satisfaction: t (307.45) = 3.60, p < .001, d = .37).

Discussion

A thematic analysis of married individuals’ recalled financial disagreements suggests that the content of these descriptions could be organized along two overarching dimensions as the social media conflicts in the previous study – “concerns about fairness” and “concerns about responsibility”. Those financial disagreements that were at the extremes of these dimensions were associated with most detrimental relationship outcomes in this sample of married couples. Conversely, married couples that were discussing, even in disagreement, mundane everyday expenses and spending reported more positive relationship outcomes.

General Discussion

This research contributes to an understanding of the role of finances in romantic relationships, specifically financial conflicts in relationships. Information about themes of financial conflict among advice seekers on social media and about themes of financial disagreements among married couples might guide future research and might contextualize people’s own experiences. In times of economic adversities such as the widespread cost-of-living crisis and economic recession (e.g., CBC, 2022; NYT, 2023), managing these financial pressures is particularly critical. Understanding the content of financial conflicts and their links to relationship outcomes might help identify conflict severity or whether a couple should seek help. For instance, Study 2 suggests that disagreements that include references to fair contributions to household finances and disagreements that include references to perceiving the partner as irresponsible are particularly detrimental to relationships. Couples who find themselves arguing about these types of financial conflicts might be particularly in need of intervention. Conversely, Study 2 also suggested that disagreements about daily mundane expenses were associated with better relationships. This might be an indicator of beneficial relationship practices – communicating about small financial decisions might prevent more detrimental conflicts later.

There was considerable overlap between the two samples: overarching themes of fairness and responsibility were relevant in both studies, and several themes were found in both instances (“relative contributions”, “exceptional expenses”, “job and income”, “different values”, and “perceived irresponsibility”). Other themes emerged primarily in the social media sample (e.g., “who pays”; “one-sided decisions”; “terms of arrangement”) – perhaps not surprisingly, as this sample included a much wider range of types of conflicts. Two themes emerged primarily in the married sample (“mundane expenses”; “money management”) – reflecting the relatively low stakes, day-to-day disagreements that made up the financial conflict descriptions in this study. Also notable was that while developed independently of existing lines of research in the relationship literature, the themes identified do reflect previous research on related topics.

Research related to the identified themes

The theme of ‘irresponsible decisions’ as a topic of financial conflicts may reflect past research findings that positive spending behaviors – mostly defined as contributing to saving accounts – are linked to better relationship satisfaction (e.g., Li et al., 2020; Mao et al., 2017; Ross et al., 2017; Wilmarth et al., 2021). This theme might also reflect the link between partner instrumentality to goals and the closeness someone feels for that partner (e.g., Fitzsimons & Fishbach, 2010): Perceived irresponsibility in a partner might create conflict as it threatens one’s own financial goals.

The theme of ‘different values’ reflects research on the benefits of feeling similar to one’s partner (e.g., Acitelli et al., 2001), and the benefits of perceiving shared financial values (Archuleta et al., 2013; Mao et al., 2017; Totenhagen et al., 2019). One reason for this beneficial effect of similarity in financial values is that couple who share values are better able to communicate about financial issues (LeBaron-Black et al., 2022), underlining the possibility that they might have fewer or more productive disagreements about money.

The theme of “one-sided decisions” might relate to research in financial deception and secret consumption behavior. Research on relational consequences of financial secrecy has been mixed. Hiding financial decisions per se was not linked to relationship satisfaction in some studies (Garbinsky et al., 2020), and keeping minor consumer behaviors intentionally from one’s partner has been linked to feeling guilty and consequently making more prorelational decisions as consequence (Brick et al., 2022). However, financial deception in a large sample of emerging adults was linked to less relationship flourishing (Saxey et al., 2022b) and participants who reported having kept a financial secret from their partner reported less marital satisfaction (Jeanfreau et al., 2018). The ‘one-sided decisions’ theme might capture the conflicts that occur once the hidden financial behaviors come to light, whereas people who engage in financial secrecy successfully might not experience relational detriments to the same degree.

The theme “relative contributions” reflects research showing a strong overlap between conflicts about chores and conflicts about money (Dew et al., 2012) and that disagreements over money tend to spill over into other conflicts (e.g., Wheeler & Kerpelman, 2016). As expressed in the social media posts, considerations of what might be fair in a partnership take into account not only each partner’s earnings but also their contributions to the household in terms of chores. More generally, this theme is linked to social exchange theory that discusses the detrimental consequences of feeling over-benefitted or under-benefitted in a relationship (e.g., Cook et al., 2013) and unequal financial power in relationships (LeBaron et al., 2019). The topic of gift giving was a prominent concern in this theme and has been studied as a factor in relationships (e.g., Dunn et al., 2008).

The themes of ‘terms of arrangements’ and ‘who pays’ perhaps reflect conflicts that become more likely when partners keep separate finances rather than pay everything from one joint account. Thus, these themes might reflect research showing that couples who pool finances tend to report more relationship satisfaction (e.g., Addo & Sassler, 2010; Kenney, 2006) and fewer financial conflicts (Gladstone et al., 2022). The “terms of arrangement” theme also reflects work showing that discrepant financial roles (i.e., partners giving conflicting reports of who is responsible for managing finances in the relationship) are linked to more financial disagreements (Morgan et al., 2021).

The theme capturing conflicts about “income and job” perhaps reflects the detrimental influence of financials stress and economic struggles (Britt et al., 2008; Kelley et al., 2018; Kerkmann et al., 2000; LeBaron et al., 2020; Totenhagen et al., 2018; 2019). It is notable that in Study 2, the presence of this theme in financial disagreements between partners was most strongly linked to relationship outcomes, underlining the importance of financial worry in relationships.

Limitations and future directions

Process versus Content

Note that for consequences of financial conflicts it might matter less what the topic is than how partners discuss their conflict. For example, a soft versus hard start-up to conflict discussion can affect relationship satisfaction (Archuleta et al., 2013) and a hot versus calm conflict tactic might play a role in likelihood of conflict resolution (Dew & Dakin, 2011). Similarly, it might be the timing of when financial disagreements are raised that matters more than the content of these conflicts: Initiating financial discussions earlier in a relationship benefitted quality of financial communication between partners (Saxey et al., 2022a). Future studies should examine the types of conflict in relation to timing within the course of the relationship and in relation to how these conflicts are experienced by relationship partners.

Samples

The first study relied on social media posts, which are likely made as a last resort, by people at their wits’ end. Thus, they might represent extreme examples of financial conflict, once-in-a-relationship type of issues rather than every-day financial conflicts. On the one hand this aspect of the data leads us to capture a fuller range of possible financial conflicts, including those that are rare. On the other hand, this aspect of the data might bias the frequency of the identified themes. The second study examined much more mundane financial disagreements among married individuals and identified relatively different frequencies. Perceived irresponsibility was the most frequent theme in both samples, but conflicts about job and income were much more frequent in the social media sample than the married sample.

The marriage status of the sample in Study 2 also limits generalization of the findings. Married individuals are in an economically advantaged position, as marriage status is proxy for having the financial resources to get married in the first place, often indicates mainstream sexual orientation majority, and often means the household can rely on two incomes and two people’s contributions. Even across both studies, this research cannot draw conclusions about the frequency of themes of financial conflicts in other samples – its aim was limited to identify and explore the range of topics and themes.

Future research should examine the topic of financial conflicts in other populations. For example, there may be unique challenges associated with living together as unmarried couple, parenting young children, with living in separate households, or when living in larger multigenerational households. Similarly, some of the conflicts identified in both our studies might be irrelevant for some populations: negotiating prenups or house purchases might be relevant only to couples in specific phases of their life, and discussion on who pays for joint expenses might not apply to those couples who have fully joint finances.

Timing of data collection

Data was collected from 2021 (Study 1) and in 2022 (Study 2). Thus, the data collection of Study 1 occurred during the tail-end of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated economic struggles due to lay-offs, restricted hours, increased housing and grocery prices. Pandemic-associated financial hardship might have amplified financial conflicts (e.g., Schmid et al., 2021), just as conflict among partners may be more likely when experiencing hardship (Kelley et al., 2018; Kerkmann et al., 2000; LeBaron et al., 2020). Very few of the social media posts (and less than 0.01% of the elicited disagreements in Study 2) made references to the COVID-pandemic. The references were indirectly related to the financial conflict: for example, someone described having lost their job due to pandemic lay offs but the main financial conflict was the partner’s lack of effort in gaining new employment. Thus, it is unlikely that the pandemic introduced new types of conflict, but it might have amplified conflict that was already there.

Intersectionality and bias in qualitative coding

Qualitative analysis is subject to potential bias due to the rater’s perspective. Raters were White middle-class women who might have a limited perspective on issues related to money and power, due to their own privileged social position. Raters might lack understanding of the experiences and challenges faced by individuals from marginalized groups, who may face structural inequalities that affect their relationships and their financial situation. Participants in Study 2 were also primarily White with an average income comparable to the US average (i.e., not lower income) and might have reported conflicts with the limits of this experience. Future research should extend to specifically seek to understand the experiences and financial conflicts of lower income and minority groups.

Practical Implications

People in relationships might take away several messages from our studies. First, they might be relieved to find that disagreeing with the partner is not unusual (almost every participant could recall a recent financial disagreement with the partner when prompted), and that there is a vast range of conflict topics connected to finances, even if these disagreements are not about money at first glance. For example, many reddit users complained about the distribution of chores in the household as unfair in light of each partner’s financial contributions. Being aware of the underlying connection to financial concerns in some of their disagreements might help partners discuss and resolve these conflicts better. Second, as counterpart to considering financial connections more, couples who argue about individual financial decisions might consider underlying concerns more. Partners could reflect whether their deeper concerns about fairness and irresponsibility might bias their view of a specific financial disagreement. Being aware of these potentially underlying larger concerns about the partner’s attitudes might put individual financial disagreements into context. Third, as disagreements about everyday mundane financial issues were linked to more positive feelings about the partner and the relationship, people might find that discussing small everyday financial decisions with the partner can be beneficial. Staying in touch with the partner’s financial perspective through repeated discussions about day-to-day purchases might prevent the festering of small disagreements into larger concerns.

Conclusions

Discussions of money remain one of the ‘last taboos’ (Petronio, 2002) in Western culture. However, financial concerns are particularly threatening to people as they put not only psychological but physical well-being at risk (e.g., eviction, food insecurity). Financial concerns might also be particularly threatening to romantic relationships because of the interdependent nature of living in the same household, with joint expenditures. This research identifies themes to organize the topics of people’s financial struggles with their romantic partner. These themes of financial conflicts might provide a stepping-stone for future research on financial conflicts in relationships or the role of finances in relationships more generally.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for When couples fight about money, what do they fight about? by Johanna Peetz, Zoe Meloff, and Courtney Royle in Journal of Social and Personal Relationships.

Acknowledgement

We thank Thalia Charlebois, Erika Doucette, Odin Fisher-Skau, Ari Melikhova, and Sienna Miller for research assistance.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The research was funded by a grant of the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (#435-2012-1211) to the first author.

Open Research Statement: As part of IARR’s encouragement of open research practices, the authors have provided the following information: This research was not pre-registered. The data used in the research are available. The data can be obtained at https://osf.io/wy9tj/?view_only=b3ddb5db95ee4b97b65ef02c8e8db5b1. The materials used in Study 2 are available. The materials can be obtained at https://osf.io/wy9tj/?view_only=b3ddb5db95ee4b97b65ef02c8e8db5b1

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online

ORCID iDs

Johanna Peetz https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5547-0315

Zoe Meloff https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7964-2000

References

- Acitelli L. K., Kenny D. A., Weiner D. (2001). The importance of similarity and understanding of partners’ marital ideals to relationship satisfaction. Personal Relationships, 8(2), 167–185. 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2001.tb00034.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Addo F. R., Sassler S. (2010). Financial arrangements and relationship quality in low-income couples. Family Relations, 59(4), 408–423. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00612.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostolou M. (2019). Why men stay single? Evidence from reddit. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 5(1), 87–97. 10.1007/s40806-018-0163-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Archuleta K. L., Grable J. E., Britt S. L. (2013). Financial and relationship satisfaction as a function of harsh start-up and shared goals and values. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 24(1), 3–14. 10.2466/07.21.pr0.108.2.563-576 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2012). Thematic analysis. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Brick D. J., Wight K. G., Fitzsimons G. J. (2022). Secret consumer behaviors in close relationships. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13(15), 403–411. 10.1002/jcpy.1315 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Britt S. L., Huston S. J. (2012). The role of money arguments in marriage. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 33(4), 464–476. 10.1007/s10834-012-9304-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Britt S., Grable J. E., Goff B. S. N., White M. (2008). The influence of perceived spending behaviors on relationship satisfaction. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 19(1), 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- CBC . (2022). https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/canadians-shopping-rising-food-costs-1.6483250

- Clarke V., Braun V., Hayfield N. (2015). Thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods, 12(3), 222–248. [Google Scholar]

- Cook K. S., Cheshire C., Rice E. R. W., Nakagawa S. (2013). Social exchange theory. In J. DeLamater & A. Ward (Eds.), Handbook of Social Psychology (pp. 61–88). Springer Science + Business Media. 10.1007/978-94-007-6772-0_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dew J. (2008). Debt change and marital satisfaction change in recently married couples. Family Relations, 57(1), 60–71. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00483.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dew J., Barham C., Hill E. J. (2021). The longitudinal associations of sound financial management behaviors and marital quality. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 42(1), 1–12. 10.1007/s10834-020-09701-z33223786 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dew J., Britt S., Huston S. (2012). Examining the relationship between financial issues and divorce. Family Relations, 61(4), 615–628. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00715.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dew J., Dakin J. (2011). Financial disagreements and marital conflict tactics. Journal of Financial Therapy, 2(1), 23–42. 10.4148/jft.v2i1.1414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dew J., LeBaron A., Allsop D. (2018). Can stress build relationships? Predictors of increased marital commitment resulting from the 2007–2009 recession. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 39(3), 405–421. 10.1007/s10834-018-9566-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn E. W., Huntsinger J., Lun J., Sinclair S. (2008). The gift of similarity: How good and bad gifts influence relationships. Social Cognition, 26(4), 469–481. 10.1521/soco.2008.26.4.469 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons G. M., Fishbach A. (2010). Shifting closeness: Interpersonal effects of personal goal progress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(4), 535–549. 10.1037/a0018581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk J. L., Rogge R. D. (2007). Testing the ruler with item response theory: Increasing precision of measurement for relationship satisfaction with the Couples Satisfaction Index. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(4), 572–583. 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbinsky E. N., Gladstone J. J., Nikolova H., Olson J. G. (2020). Love, lies, and money: Financial infidelity in romantic relationships. Journal of Consumer Research, 47(1), 1–24. 10.1093/jcr/ucz052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone J. J., Garbinsky E. N., Mogilner C. (2022). Pooling finances and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 123(6), 1293–1314. 10.1037/pspi0000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huff C., Tingley D. (2015). “Who are these people?” Evaluating the demographic characteristics and political preferences of MTurk survey respondents. Research & Politics, 2(3), 205316801560464. 10.1177/2053168015604648 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J. B., Carrese D. H., Willoughby B. J. (2023). The indirect effects of financial conflict on economic strain and marital outcomes among remarried couples. International Journal of Stress Management, 30(1), 69–83. 10.1037/str0000277 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanfreau M., Noguchi K., Mong M. D., Stadthagen H. (2018). Financial infidelity in couple relationships. Journal of Financial Therapy, 9(1), 1–20. 10.4148/1944-9771.1159 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley H., Chandler A., LeBaron-Black A., Li X., Curran M., Yorgason J., James S. (2022). Spenders and tightwads among newlyweds: Perceptions of partner financial behaviors and relational well-being. Journal of Financial Therapy, 13(1), 1. 10.4148/1944-9771.1288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley H., LeBaron A., Hill E. J. (2018). Financial stress and marital quality: The moderating influence of couple communication. Journal of Financial Therapy, 9(2), 18–36. 10.4148/1944-9771.1176 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney C. T. (2006). The power of the purse: Allocative systems and inequality in couple households. Gender & Society, 20(3), 354–381. 10.1177/0891243206286742 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerkmann B. C., Lee T. R., Lown J. M., Allgood S. M. (2000). Financial management, financial problems and marital satisfaction among recently married university students. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 11(2), 55–65. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1355865408 [Google Scholar]

- Kimiafar K., Dadkhah M., Sarbaz M., Mehraeen M. (2021). An analysis on top commented posts in reddit social network about COVID-19. Journal of Medical Signals and Sensors, 11(1), 62–65. 10.4103/jmss.JMSS_36_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBaron A. B., Curran M. A., Li X., Dew J. P., Sharp T. K., Barnett M. A. (2020). Financial stressors as catalysts for relational growth: Bonadaptation among lower-income, unmarried couples. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 41(3), 424–441. 10.1007/s10834-020-09666-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]