Abstract

Background

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a rare, benign, inflammatory, self-limited, granulomatous dermatosis that affects children and young adults. The most frequent clinical form is localized GA. Deep GA generally presents as painless palpable subcutaneous nodules in the lower extremities, buttocks, hands and scalp. They may have a fast-growing firm subcutaneous mass presentation, mimicking a malignant lesion which requires an imaging evaluation. Diagnosis of deep GA can be more difficult and imaging evaluation is frequently performed, ultrasound being one of the techniques used.

Objective

To describe the US characteristics of GA in a pediatric series.

Materials and method

Descriptive, retrospective, 14-year study of all pediatrics GA cases.

Results

Twelve pediatric cases with GA. 66% females. The lesions were mainly distributed in the extremities: 50% in the lower extremities and 42% in the upper extremities, mostly with multiple lesions. A total of 45 lesions were analyzed, 8 superficial lesions and 37 deep lesions. On ultrasound, the superficial GA corresponded to hypoechoic poorly defined solid plaque like or nodular lesions, located in the dermal-epidermal plane. The deep GA presented as solid nodular, poorly defined hypoechoic lesions that compromised the deep subcutaneous-aponeurotic plane.

Conclusion

GA is an inflammatory lesion that presents as a superficial or deep palpable nodule that predominantly affects children. Superficial and deep GA present characteristic findings on US that can guide the diagnosis. The radiologist needs to know its US appearance to be able to suggest the diagnosis, especially in multiples lesions.

Keywords: Granuloma annulare, Ultrasound, Skin lesions, Soft tissue nodules

Introduction

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a rare, benign, inflammatory granulomatous dermatosis that affects children and young adults. It is self-limited, of unknown etiology [1–4] characterized by the formation of skin lesions with various clinical forms of presentation: localized GA, generalized GA, perforating GA, and deep or subcutaneous GA [1, 5]. The most frequent clinical form is localized GA, found in 80–90% of cases [5].

The generalized and localized forms are characterized by the presence of dermal papules with a tendency to form rings visible on physical examination, which vary in the breadth of their distribution [1]. In the perforating form, superficial lesions perforate the epidermis and may develop a central umbilication [1]. The diagnosis in these cases (localized GA, generalized GA, perforating GA) is usually performed on the basis of clinical examination [1, 4, 5].

Deep GA occurs more frequently in healthy young children, predominantly females [2, 3], in whom it manifests as immobile, painless subcutaneous nodules, whose diameter varies between 6 and 35 mm [4]. They are generally found in the lower extremities, especially the pretibial area, followed by the buttocks, hands and scalp [2, 3].

The presentation of deep GA can be concomitant with superficial GA in 25% of cases [1, 2]. Due to the subcutaneous location, the diagnosis of deep GA can be more difficult than that of other types of GA, and differential considerations include both benign and malignant processes [3]. In deep GA, imaging evaluation can be performed to further characterize and stage the lesion [1]. Deep GA is not known to many radiologists due to its low frequency [1, 2]. In deep GA cases, given their subcutaneous location and small size, it is frequent that clinicians recommend imaging evaluation or either directly an excisional biopsy, without radiological evaluation [1].

Ultrasound is a fast, widely available and inexpensive non-invasive procedure that can help diagnose superficial and deep GA [1, 6]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MR) is particularly useful in characterizing soft tissue masses and its use often leads to a specific diagnosis [3].

There is little literature that describes the imaging appearance in US and MR of this entity, both in its superficial and deep presentation [1]. Failure to consider GA as a tentative diagnosis often leads to US and MRI examination and in some cases to inappropriate surgical interventions [6].

Objective

The objective of this study is to describe the US characteristics of GA observed in this series, both superficial and deep, and evaluate the demographic characteristics and locations of the lesions.

Materials and method

Descriptive, retrospective, non-experimental study approved by the Institutional Review Board, who granted a waiver for informed consent in the retrospective analysis.

We identified all pediatric patients under 15 years old with diagnosis of granuloma annulare based on histology, magnetic resonance or ultrasound in our institution in a 14-year period. The inclusion criteria were to have the images of high resolution ultrasound saved in the computational medical system (PACS Agfa IMPAX®).

We collected demographic characteristics (age and sex), referral diagnoses, imaging studies, and histopathological findings in the corresponding cases.

In agreement, two radiologists with experience in pediatric and skin imaging described the US characteristics of the lesions: number of lesions, location and size. The lesions are divided into hypoechoic solid plaque like, hypoechoic solid nodular lesion on the dermal or subcutaneous plane. The presence of inner vascular vessel and inflammatory changes were also evaluated.

Results

Twelve patients were identified, between 2 and 13 years old. Average age was 5.6 years. Sixty six percent corresponded to female patients (8 cases) and 4 males. All patients were studied with US, and one with US and MRI. Four cases were confirmed by biopsy.

The lesions were mainly distributed in the extremities: 50% (6 patients) presented lesions in the lower extremities and 42% (5 patients) in the upper extremities. Other locations were thoraco-abdominal wall, lumbar dorsum and scalp.

The referral diagnoses were: nodule in four cases, small part volume increase in two cases, GA or suspected GA just in three cases, and three other diagnoses. (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

13 Year-old girl. Presented with some hand skin lesions, characterized by papules than tended to form rings on the skin

A total of 45 lesions were analyzed, 8 corresponded to superficial lesions and 37 to deep lesions on the subcutaneous or subfascial plane. Two patients presented with single lesions and 10 patients presented with multiple lesions (83%). The diameter of the lesions varied from 4 to 30 mm.

On ultrasound, the superficial GA corresponded to hypoechoic solid plaque like or nodular lesions, with poorly defined borders, located in the dermal-epidermal plane. They could lift the skin surface. Little vascularization was observed on color Doppler. No cystic lesions or calcifications were identified. (Figs. 2, 3).

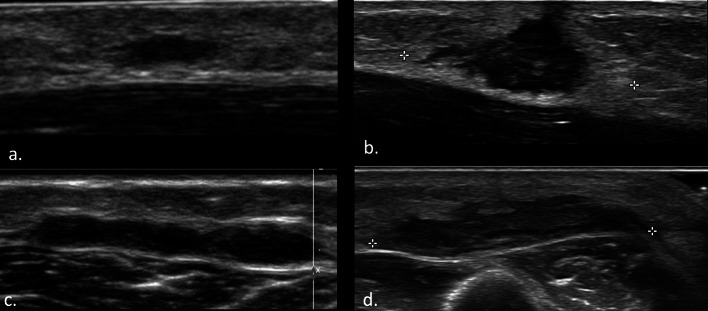

Fig. 2.

Superficial granuloma annulare: on ultrasound, they resemble hypoechoic solid plaques or correspond to nodular lesions, with poorly defined borders, located in the dermal-epidermal plane. They may lift up the skin surface. They compromise different locations: a lateral chest wall, b medial ankle, c hand, d lateral ankle

Fig. 3.

Granuloma annulare: superficial presentation. Hypoechoic nodular lesions, dermal-epidermal, poorly vascularized on color Doppler. No cystic lesions or calcifications were identified. a, b hand, c, d lateral ankle

The deep GA presented as solid nodular, hypoechoic lesions with poorly defined borders that protruded to the deep subcutaneous plane, settling on the aponeurotic plane without compromising it. They can present little internal vascularization on Doppler US. They did not present calcifications or cystic areas. In five patients the fatty subcutaneous tissue that surrounded the lesion was hyperechogenic, with peripheral vascularization in some cases (Figs. 4,5).

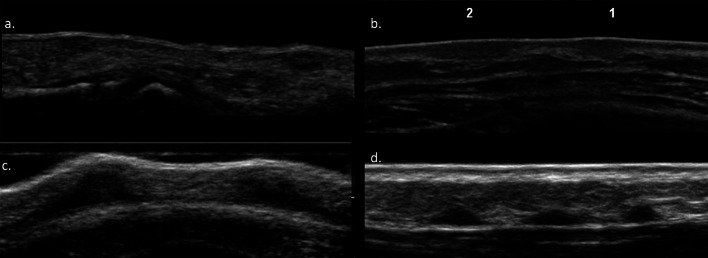

Fig. 4.

Deep granuloma annulare: solid pseudonodular, hypoechoic lesions with poorly defined borders and variable sizes. They are located in the deep subcutaneous plane, settling on the aponeurotic plane without compromising it. They may present a hyperechogenic halo around the nodule. a Pretibial, b forearm, c left leg, d hand

Fig. 5.

Granuloma annulare: multiple presentations. Superficial dermo-epidermal lesions a finger, b chest wall. Deep subcutaneous lesions c scalp occipital region, d pretibial

Two patients presented only superficial lesions and two other patients presented deep and superficial lesions at the same time.

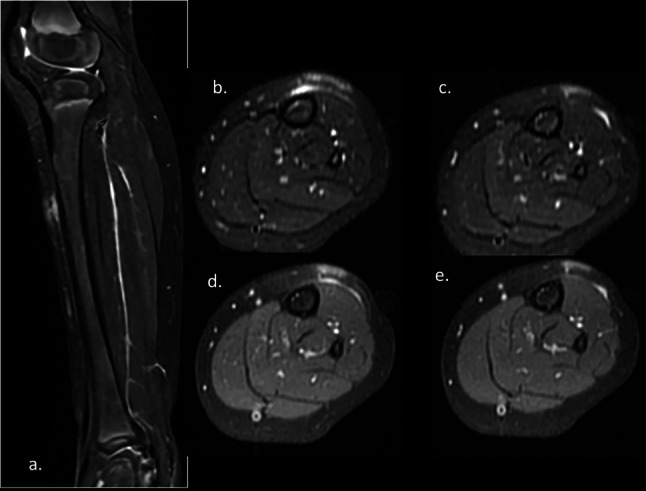

One patient with a subcutaneous lesion in the pretibial region (unilateral) was initially studied with US and later with MRI (2 months apart). This last study presented nodular lesions with a solid appearance in the subcutaneous plane of both pretibial regions, which were located adjacent to the muscular aponeurosis, without compromising it, with perilesional edema. The lesions presented irregular homogeneous borders, behaved hypointense in T1, hyperintense in T2 and in the contrast study they presented homogeneous enhancement with Gadolinium (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Deep granuloma annulare: contrast-enhanced MRI of the leg. Multiple nodular lesions in the subcutaneous layer with perilesional edema. Adjacent to the muscular aponeurosis. Hyperintense on T2 a Saggital and b, c axial T2FS. They enhance with gadolinium (d, e)

Three patients with deep GA and one patient with superficial GA were also studied with biopsies that confirmed the diagnosis. Only 33% of our patients had a biopsy and that is a weakness of our study, but in the other cases the clinical-dermatological presentation and evolution were consistent with granuloma annulare, and biopsy was not recommended by the clinician.

Discussion

Granuloma annulare generally occurs in healthy children between 2 and 5 years of age [2, 3] with a slight propensity in girls [2, 6]. The size of the lesions in our series ranged from 4 to 30 mm.

The most frequently described GA location is in the lower limbs [2]. Although they may be found in other sites: buttocks, hands, feet and scalp [1, 2]. The location of pretibial GA has been described with a frequency of 65% [3]. In our series, which included superficial and deep GA, it was 33% for pretibial location.

Of the different types of GA, those of superficial presentation (generalized or localized) are the most frequent [5]. Deep GA (subcutaneous) is a rare variant of unknown prevalence [2]. In general, deep GA presents as a painless, immobile, fast-growing mass, and most lesions regress spontaneously over months or years [1, 2, 6].

Kransdorf describes the multiple presentations of GA in up to 60% of patients. In our group, eighty three per cent of the patients had multiple lesions. The etiology of GA is unknown [1–4, 6], and the involvement of triggering events (eg, trauma, insect bites, and infections) has not been demonstrated [2, 3, 6]. The presentation of GA in monozygotic twins and siblings has been described, which suggests a familial tendency in at least some cases [1].

The description of the radiological appearance of granuloma annulare is scarce in the literature [3], both in US and in MRI [1, 5]. In 2022, Rodriguez-Garijo described three different patterns on US dermal pattern, hypodermal pattern and mixed pattern [4]. Only a few reports have described the sonographic characteristics of deep GA [6].

The imaging evaluation of these lesions depends on the clinical presentation and evolution, especially in rapidly growing lesions. The role of ultrasound as an additional non-invasive evaluation is justified in cases of unusual clinical presentation to characterize subcutaneous soft tissue mass, as well as exclusion of other cystic and vascular lesions [3, 6]. In our cases, all patients had hypoechogenic ill-defined solid lesions. The superficial lesions were located in the dermal-epidermal plane as a plaque or nodule, and the deep lesions were located in the subcutaneous subfascial tissue as a nodule. Some cases can present inflammatory changes of the fatty subcutaneous tissue that surrounds the lesions, mostly contacting with the aponeurotic plane. They were hypovascular on Doppler study, and some lesions presented peripheral vascularization, similar to that described in the literature [4, 6].

Deep GA can contact the fascia, but this lesion does not adhere to it or invade the underlying planes [6, 7]. In some cases, the deep GA presented a slightly hyperechoic halo around the nodule, in accordance with other descriptions [6, 8].

In our series of 12 patients, only one was studied with US and MRI. Although the radiological appearance in MRI of the GA [1] has been described, which is relatively characteristic in young patients, we did not find that MRI provided more information than that obtained by the ultrasonographic study performed.

Currently incisional biopsy is the standard criterion and there are no laboratory tests to help confirm the diagnosis of GA [5]. In histology, an immunologically mediated reaction has been described in which inflammation surrounds blood vessels and collagen and elastic tissue are altered [1, 2]. Subcutaneous nodules in granuloma annulare spare the epidermis and are typically characterized histologically by foci of collagen degeneration with peripheral palisade histiocytes, surrounded by a zone of reactive inflammation and fibrosis [1, 2].

The clinical and ultrasound differential diagnosis of GA in children includes other subcutaneous masses that are relatively asymptomatic, such as hemangiomas and other vascular anomalies, lymphatic malformation, lipoma, fibroma or fibromatosis, granuloma, nodular fasciitis, foreign body reaction, infection, fat necrosis [3, 6].

GA has an ultrasound presentation that can orient to the diagnosis from other differential diagnoses, especially in the presence of multiple lesions. US (performed by a trained and qualified expert in high resolution ultrasound) can help confirm the diagnosis and avoid invasive procedures or other unnecessary studies [3, 6, 9] and would even avoid inappropriate therapy [3] given its known self-limiting course.

Conclusion

GA is an inflammatory lesion that presents as a painless palpable solid nodule, superficial or deep, that predominantly affects children. Diagnosis of deep GA can be challenging because a fast-growing, firm subcutaneous mass can mimic a malignant lesion and thus further imaging evaluation is required when the clinical findings are nonspecific or do not follow a typical course.

Superficial and deep GA present on US as hypoechogenic ill defined hypovascular solid plaque or nodule on the dermal or subcutaneous plane that guide the diagnosis, even more if they are multiple lesions.

Given the benign and self-limited behavior of GA, we should know its characteristics on US to be able to suggest or support the clinical diagnosis, especially in multiples lesions, and thus avoid follow-up or more invasive procedures for its definitive diagnosis.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by [CW], [NR], [LP-M] and [XC]. The first draft of the manuscript was written by [CW and NR] and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of University del Desarrollo de Santiago. ID 1156 -2022 and ID 42 -2012.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients and parents.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kransdorf MJ, Murphey MD, Temple HT. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: radiologic appearance. Skelet Radiol. 1998;27(5):266–270. doi: 10.1007/s002560050379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reyes-Baraona F, Hasbún P, González S, Zegpi MS. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: a case report. Rev Chile Pediatr. 2017;88(5):652–655. doi: 10.4067/S0370-41062017000500013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung S, Frush DP, Prose NS, et al. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: MR imaging features in six children and literature review. Radiology. 1999;210(3):845–849. doi: 10.1148/radiology.210.3.r99mr11845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodríguez-Garijo N, Tomás-Velázquez A, Estenaga A, et al. Granuloma annulare subtypes: sonographic features and clinicopathological correlation. J Ultrasound. 2022;25:289–295. doi: 10.1007/s40477-020-00532-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corigliano M, Achenbach RE (2012) Granuloma annulare: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Argentine J Dermatol 93(4). http://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1851-300X2012000400004&lng=es&tlng=es

- 6.Vázquez-Osorio I, Quevedo A, Rodríguez-Vidal A, Rodríguez-Díaz E. Usefulness of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(3):e200–e201. doi: 10.1111/pde.13470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah SH, Callahan MJ. Ultrasound evaluation of superficial lumps and bumps of the extremities in children: a 5-year retrospective review. Pediatr Radiol. 2013;43(Suppl 1):S23–40. doi: 10.1007/s00247-012-2590-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stenzel M, Voss U, Mutze S, Hesse V. A pretibial lump in a toddler-sonographic findings in subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Ultraschall Med. 2010;31(1):68–70. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-963786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davids JR, Kolman BH, Billman GF, Krous HF. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: recognition and treatment. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13(5):582–586. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199309000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]