Abstract

Background & Aims

D-amino acids, the chiral counterparts of protein L-amino acids, were primarily produced and utilized by microbes, including those in the human gut. However, little was known about how orally administered or microbe-derived D-amino acids affected the gut microbial community or gut disease progression.

Methods

The ratio of D- to L-amino acids was analyzed in feces and blood from patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and healthy controls. Also, composition of microbe was analyzed from patients with UC. Mice were treated with D-amino acid in dextran sulfate sodium colitis model and liver cholangitis model.

Results

The ratio of D- to L-amino acids was lower in the feces of patients with UC than that of healthy controls. Supplementation of D-amino acids ameliorated UC-related experimental colitis and liver cholangitis by inhibiting growth of Proteobacteria. Addition of D-alanine, a major building block for bacterial cell wall formation, to culture medium inhibited expression of the ftsZ gene required for cell fission in the Proteobacteria Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, thereby inhibiting growth. Overexpression of ftsZ restored growth of E. coli even when D-alanine was present. We found that D-alanine not only inhibited invasion of pathological K. pneumoniae into the host via pore formation in intestinal epithelial cells but also inhibited growth of E. coli and generation of antibiotic-resistant strains.

Conclusions

D-amino acids might have potential for use in novel therapeutic approaches targeting Proteobacteria-associated dysbiosis and antibiotic-resistant bacterial diseases by means of their effects on the intestinal microbiota community.

Keywords: D-Amino Acid, Liver Cholangitis, Microbiome, Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Ulcerative Colitis, Colitis, Antibiotic-resistant Bacteria, ftsZ, E.coli, K. pneumoniae

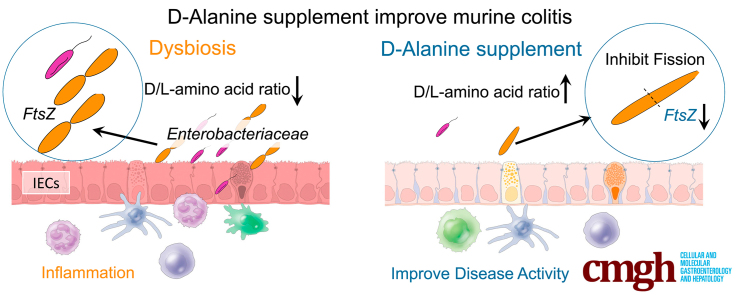

Graphical abstract

Summary.

Dysbiosis triggers intestinal inflammation; however, the mechanism by which D-amino acids affect the microbiome niche remains unknown. We found that D-amino acids ameliorate experimental colitis and cholangitis by inhibiting the growth of Proteobacteria. Supplementation with D-amino acids may have a potential therapeutic role in inflammatory bowel disease.

In mammals, L-amino acids (L-aa) are primarily used for the synthesis of proteins and functional molecules. L-aa are important for the maintenance of homeostasis, and an imbalance in L-aa leads to the development of diseases, such as various liver diseases.1, 2, 3, 4 D-amino acids (D-aa), the chiral counterparts of L-aa, are present in most organic matter but are rare in mammals,5,6 except for D-serine (D-ser), D-aspartate (D-asp), D-alanine (D-ala), and D-cysteine (D-cys). An imbalance in serum D- and L-serine has been reported in renal disease and schizophrenia,7 and modulation of D- and L-serine ratios is used as a therapy for schizophrenia.8

Unlike mammals, microbes have racemase enzymes that can convert L-aa to D-aa. Microbes utilize D-aa to synthesize cell walls that cannot be digested by mammals.9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Intestinal epithelial cells in mammals hosting gut microbes produce a D-aa oxidase enzyme that degrades D-aa, leading to a reduced burden of microbes that require this substrate.5 Although it is known that D-aa from microbes can affect mammals,5 little is known about how oral or microbial supply of D-aa affects microbes in the gut or dysbiosis-associated gastrointestinal and liver disease in humans.

Patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) with an increased complement of Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Proteobacteria experience dysbiosis.14, 15, 16, 17 In particular, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, and Enterococcus gallinarum (E. gallinarum) are increased in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)-related extraintestinal diseases such as spondyloarthritis and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC).18, 19, 20, 21 Using a murine gnotobiotic system, we have recently shown that K. pneumoniae in the feces of patients with UC-associated PSC can induce apoptosis in intestinal epithelial cells, penetrate the intestinal barrier, and participate in the production of Th17 cells in mesenteric lymph nodes.21,22 P. mirabilis has also been shown to be involved in the pathogenesis of UC-associated colitis.21,23 In recent years, an involvement of Proteobacteria in dysbiosis-related diseases has been suggested, but the precise mechanisms controlling the population size of Proteobacteria in the gut are largely unknown.

Antimicrobial therapy has been exploited to treat IBD and IBD-related diseases by regulating the numbers of Proteobacteria,24,25 but the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy is limited owing to a reduction in beneficial bacteria and the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The Centers for Disease Control recently designated carbapenem-resistant enterococci belonging to the Proteobacteria phylum as among the 3 most urgently threatening disease-causing bacteria.26

We here elucidate the mechanism by which D-aa, especially D-ala, an essential bacterial cell wall component, suppress the growth of proteobacteria. We demonstrate therapeutic potential for D-aa in IBD and IBD-related diseases in shaping the normal microbe community and without emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Results

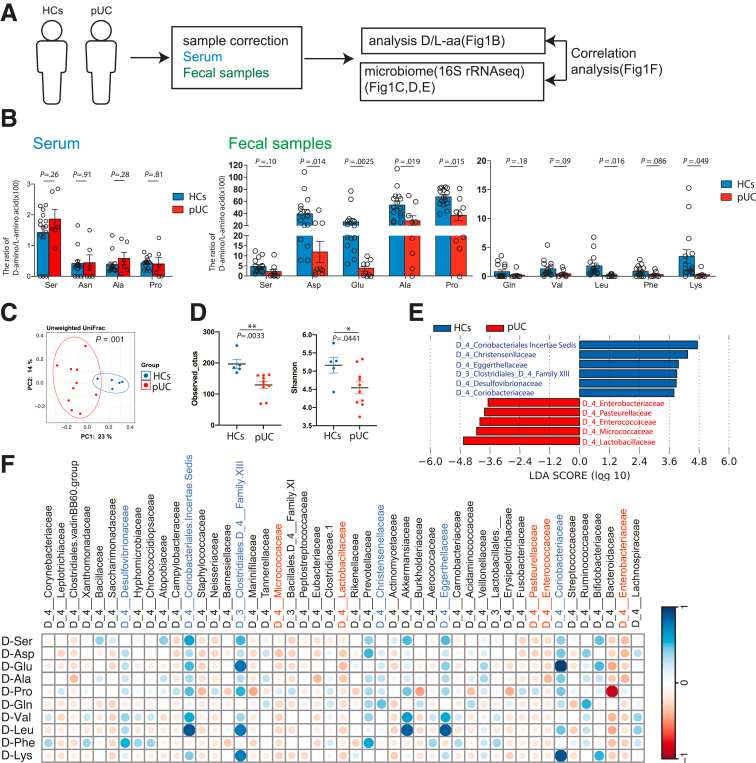

The Ratio of D-aa to L-aa in Feces was Decreased in Patients With UC

First, we analyzed the ratio of D-aa to L-aa in the serum and feces of patients with UC (pUCs) and healthy controls (HCs) (Figure 1A–B). D-ser, D-asn, D-ala, and D-pro were detected in the serum of pUCs and HCs, and the D-aa to L-aa ratio in serum was comparable between pUCs and HCs (Figure 1A). In contrast, the ratio of D-aa to L-aa was significantly lower in pUC feces as compared with HC feces, particularly for Asp, Glu, Ala, Pro, Leu, and Lys (Figure 1B). Although D-Arg, D-Met, D-Trp, and D-allo-lle have been detected in mouse feces,27 they have not previously been detected in human feces. Further, D-Pro and D-Valine have not been reported in mice but were here detected in humans (Figure 1B). The data indicate that an imbalance of D- and L-aa is a feature of UC.

Figure 1.

The ratio of D-aa to L-aa in feces is decreased in patients with active UC. (A) Experimental design. (B) The ratio of D-aa to L-aa in serum or fecal samples from HCs (n = 15) and UCs (serum, n = 6; feces, n = 9). NS, Not significant; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001 between groups; Student t-test. (C) PCoA plots of unweighted UniFrac distance of fecal microbiota from HCs and UCs. (D) Alpha and beta diversity measures. Plots are observed OTUs and Shannon indexes. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, between groups, Student t-test. (E) LDA scores higher than 2. Healthy donor group with a positive score (blue) and UC patient group with a negative score (red). (F) Correlation between the ratio of fecal D-aa to L-aa and the microbiome. Featured microbiomes from (E) are in blue (HC) and red (pUC). The strength of the correlation between each pair of variables is indicated by the diameter and color of the circles. A color code of dark blue indicates a positive correlation coefficient close to +1, and a color code of dark red indicates a negative correlation coefficient close to −1. Data are shown as standard error of the mean.

We analyzed the fecal microbial composition using 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing to determine the correlation between fecal D-aa and microbial components. As previously reported,15,28,29 pUCs have distinct bacterial communities compared with HCs, with a distinct principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) plot of Unifrac Distance (Figure 1C). The total number of observed operational taxonomic units (OTUs) and diversity of the microbes (Shannon index) in pUCs were lower than those in the HCs (Figure 1D). Lactobacillaceae, Micrococcaceae, Enterococcaceae, Pasteurellaceae, and Enterobacteriaceae were characteristic of pUC, whereas Coriobacteria and Clostridiaceae were characteristic of HC (Figure 1E). As previously reported, obligately anaerobic bacteria were enriched in HCs, whereas facultatively anaerobic bacteria, including members of Proteobacteria, were enriched in pUCs. We investigated the correlation between the microbiome composition and the fecal D-/L-aa balance (Figure 1F). We found that Clostridium group XIII, Coriobacteriaceae, Desulfovibrionaceae, Christensenellaceae, Eggerthellaceae, and Coriobacteriaeae, which were more abundant in HCs, were positively correlated with most of the individual D-/L-aa results. However, Micrococcaceae, Lactobacillaceae, Pasteurellaceae, Enterococcaceae, and Enterobacteriaceae, which were more abundant in pUCs, had a negative correlation with most of the D-/L-aa results. Collectively, the data suggest that the distinct obligate anaerobe microbiota increased in HCs suppress the distinct facultative anaerobe microbiota increased in pUCs via the bacteria-specific D-aa.

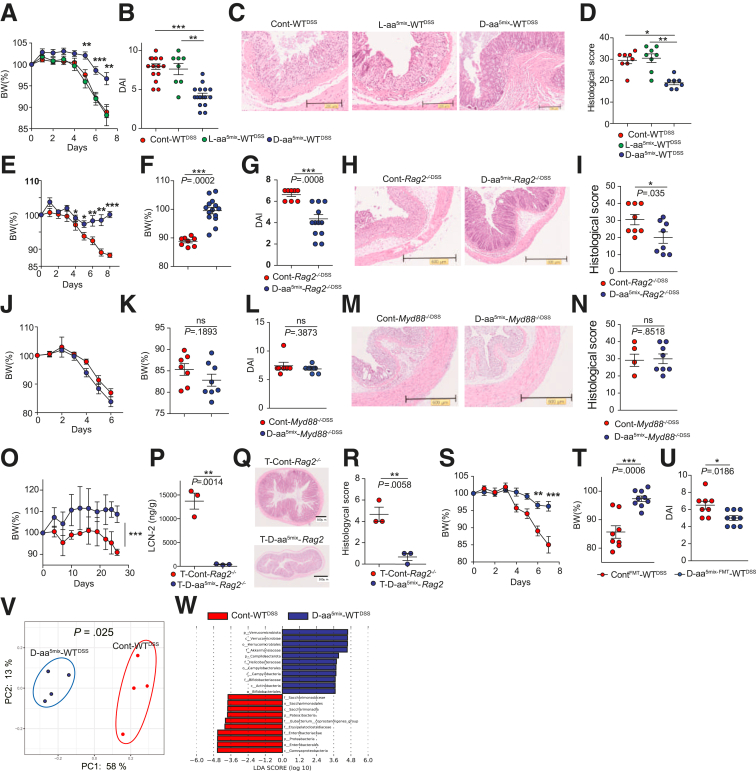

Supplementation of D-aa Ameliorates Experimental Colitis

We next determined whether manipulating the ratio of D-aa to L-aa could prevent intestinal inflammation. We selected 5 amino acids (ala, ser, glu, trp, and asn), which represent major components of D-aa in the feces and serum of humans (Figure 1A–B). We administered 1% L-aa 5-mix (L-aa5mix: L-ala, L-tryptophan, L-glutamic acid, L-serine, and L-asparagine) or 1% D-aa 5-mix (D-aa5mix: D-ala, D-trp, D-glu, D-ser, and D-asn) to mice in drinking water for 3 weeks and subsequently administered 2% dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) in drinking water for 7 days to induce chemical colitis. To reduce the cage effect, we employed littermate control mice in all experiments and shuffled them before the L-aa or D-aa perturbation. After 3 weeks of drinking water containing D-aa or L-aa, we did not observe either spontaneous colitis or inflammation in other organs such as the liver, lung, kidney, and spleen (data not shown). The total amount of the 2% DSS drinking water was comparable between L-aa5mix , D-aa5mix, and sterile water administered mice (data not shown). Mice that received D-aa5mix prior to DSS (D-aa5mix-WTDSS) had a reduced loss of body weight (BW), a lower disease activity index (DAI), and a lower histological score compared with mice in the sterile water group (Cont-WTDSS) or L-aa mix group (L-aa5mix-WTDSS) (Figure 2A–D). Next, we treated Rag2-/- mice with sterile water or 1% D-aa5mix for 3 weeks prior to 7 days of 2% DSS challenge (Cont-Rag2-/-DSS, D-aa5mix-Rag2-/-DSS). D-aa5mix-Rag2-/-DSS mice did not lose weight or develop colitis (Figures 2E–I), suggesting that the innate immune system is involved in the effect of D-aa in preventing the development of colitis. We hypothesized that D-aa supplementation ameliorates colitis through modulation of the TLR-MyD88 signal.30 To demonstrate this, we treated MyD88-/- mice with sterile water or 1% D-aa5mix water for 3 weeks prior to 7 days of 2% DSS challenge (Cont-Myd88-/-DSS, D-aa-Myd88-/-DSS). D-aa5mix-Myd88-/-DSS mice did not display ameliorated colitis compared with Cont-Myd88-/-DSS mice (Figure 2J–N), suggesting that D-aa supplementation ameliorates colitis through innate MyD88 signaling at the host side.

Figure 2.

Supplementation of D-aa ameliorate experimental colitis. (A–D) We co-housed C57BL/6J mice from the same parents until 7 weeks old before the experiment started. We then divided the mice into cages with 2 mice in each and randomly administered D-aa/L-aa. Seven-week-old C57BL/6J mice received drinking water with 1% 5-mix L-aa (L-aa5mix-WTDSS) or D-aa (D-aa5mix-WTDSS) or sterile water (Cont-WTDSS) for 3 weeks prior to 7 days of 2% DSS challenge. BW change (A), DAI score (B), H&E-stained histological sections of the colon (C), and histological scores (D) are shown. N = 14, 8, and 16 (A, B); N = 8, 8, and 8 (C, D) (Cont-WTDSS, L-aa5mix-WTDSS, D-aa5mix-WTDSS, respectively). (E–I) We co-housed Rag2-/- mice from the same parents until 7 weeks old before the experiment started. We then divided the mice into cages with 2 mice and randomly administered D-aa. Rag2-/- mice aged 7 weeks received drinking water with or without 1% D-aa5mix (Cont-Rag2-/-DSS, D-aa5mix-Rag2-/-DSS) for 3 weeks prior to 7 days 2% DSS challenge. BW change (E), percentage of BW on day 8 (F), the DAI score (G), H&E-stained histological sections from the colon (H), and histological score (I) are shown. N = 8, 14 (E, F); N = 7, 8 (G); N = 8, 8 (H, I) (Cont-Rag2-/-DSS and D-aa5mix- Rag2-/-DSS, respectively). (J–N) We co-housed Myd88-/- mice from the same parents until 7 weeks old before the experiment started. We then divided the mice into cages with 2 mice in each and randomly administered D-aa. Myd88-/- mice aged 7 weeks received drinking water 1% D-aa 5MIX (D-aa5mix-Myd88-/-DSS, n = 8), sterile water (Cont-Myd88-/-DSS, n = 7) for 3 weeks prior to 7 days 2% DSS challenge. BW change (J), percentage of BW on day 6 (K), the DAI score (L), H&E-stained histological sections of the colon (M), and histological score (N) are shown. N = 7, 8 (J–L); N = 4, 8 (M, N) (Cont-Myd88-/-DSS and D-aa5mix-Myd88-/-DSS, respectively). (O–R) We co-housed Rag2-/- mice from the same parents until 7 weeks old before the experiment started. We then divided the mice into cages with 2 mice in each and randomly administered D-aa. Rag2-/- mice aged 7 weeks transferred naive CD4+CD45RBhigh T cells received drinking water with or without 1% D-aa 5-mix for 4 weeks (T-D-aa5mix-Rag2-/-, n = 3; T-Cont-Rag2-/-, n = 3). BW change (O), fecal lipocalin-2 (LCN-2) (P), H&E-stained histological sections from colon (Q), and histological score (R) are shown. (S–U) Seven-week-old GF C57BL/6J mice received a fecal transplant from WT mice treated with or without 5-mix D-aa (ContFMT, n = 8; D-aaFMT, n = 9) following 2% DSS in drinking water. BW change (S), percentage of BW on day 7 (T), and the DAI score (U) are shown. (V, W) PCoA plots of unweighted UniFrac distance (V) and LDA scores (W) of the fecal microbiome obtained from Cont-WTDSS and D-aa5mix-WTDSS mice in Figure 2 (A). All experiments were performed in at least 2 replicates (n = 1–6, combined). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. P values were obtained via the Student t-test and analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test (A, B, D). Data are shown as standard error of the mean.

We then induced chronic colitis in a model31, 32, 33 by adoptive transfer of CD4+CD45Rbhigh naïve T cells into Rag2-/- mice treated with 1% D-aa5mix or sterile water for 3 weeks before transfer (T-Cont-Rag2-/-, T-D-aa5mix-Rag2-/-). Four weeks after T cell transfer, colitis was induced in T-Cont-Rag2-/- mice, whereas T-D-aa5mix-Rag2-/- mice did not lose weight nor develop colitis (Figure 2O–R). The data suggested that D-aa5mix supplementation suppresses both acute and chronic colitis.

To determine whether the microbiome is altered by D-aa5mix supplementation for amelioration of DSS colitis, we conducted fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) by transferring feces from wild-type (WT) mice or WT mice administered 1% D-aa5mix into germ-free (GF) mice. We then treated those mice with 2% of DSS for 7 days (ContFMT-WTDSS and D-aa5mix-FMT-WTDSS). D-aa5mix-FMT-WTDSS mice displayed ameliorated colitis compared with ContFMT-WTDSS mice (Figure 2S–U). We then compared the fecal microbe in Cont-WTDSS and D-aa5mix-WTDSS mice. As we expected D-aa5mix-WTDSS mice express different microbial composition based on PCoA plots of unweighted UniFrac analysis (Figure 2V). Cont-WTDSS mice enriched Gammaproteobacteria, Proetobacteria, and Enterobacteria, whereas D-aa5mix-WTDSS mice enriched Verrucomicrobiata (Figure 2W). Collectively, these results indicate that oral supplementation of D-aa5mix alters the intestinal bacterial community to be less pro-inflammatory.

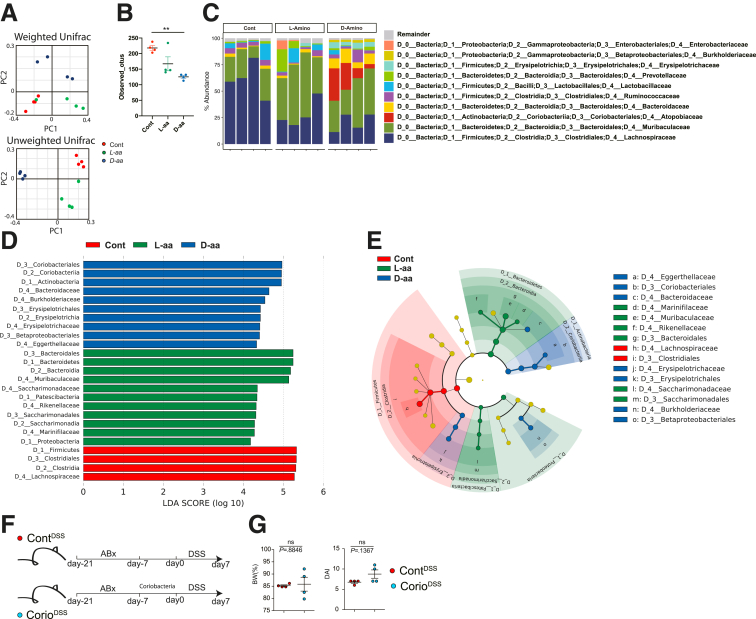

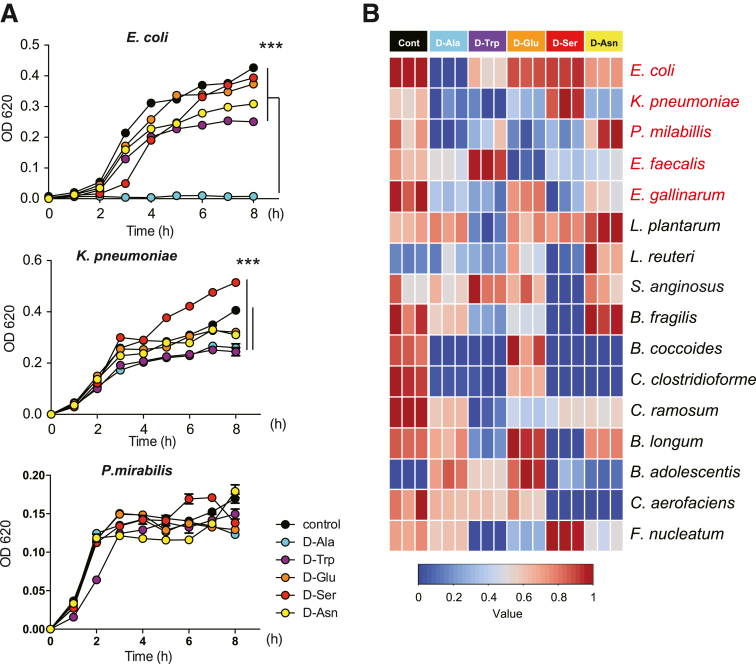

To gain insight into how the microbiome niche was altered by D-aa, we obtained feces from mice treated with sterile water, 1% L-aa5mix, or 1% D-aa5mix in their drinking water for 3 weeks before 2% DSS challenge (control, L-aa5mix, D-aa5mix mice, respectively) and performed 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing (Figure 3A–C). Weighted and unweighted analyses revealed that D-aa5mix mice altered the gut microbial composition compared with L-aa5mix mice or control mice before DSS challenge. OTUs were lower in D-aa5mix mice than in control mice (Figure 3B). Lachnospiraceae were dominant in the control mice but were reduced in the L-aa5mix and D-aa5mix mice. The L-aa5mix and D-aa5mix mice had increased Bacteroides species. The D-aa5mix mice had increased Coriobacteria (Figure 3D–E). To test whether Coriobacteria suppresses the colitis, we administered Coriobacteria for 7 days or sterile water to the antibiotic-treated WT mice and administered 2% DSS for 7 days. The BW and DAI score in mice with or without Coriobacteria were comparable (Figure 3F–G). These data suggest that Coriobacteria, which is increased in D-aa5mix mice, did not have a protective role in DSS colitis. Taken together, D-aa5mix supplementation reduces pathological Proteobacteria during DSS administration, resulting in the amelioration of colitis not due to increased Coriobacteria.

Figure 3.

D-aa altered gut microbe composition before DSS administration. (A–E) We co-housed C57BL/6J mice from the same parents until 7 weeks old before the experiment started. We then divided the mice into cages with 2 mice in each and randomly administered drinking water with or without 1% D/L-aa for 3 weeks. PCoA plots of weighted (left) or unweighted (right) UniFrac distance of 16S rRNA sequences in fecal microbiome from mice that received drinking water with or without 1% D/L-aa for 3 weeks (A). (n = 4 per group). OTUs observed (B). Microbial composition of each sample at the family level (C). LDA scores of the fecal microbiome at the family level (D). Family level phylogeny of microbiota (E). (F, G) We co-housed C57BL/6J mice from the same parents until 7 weeks old before the experiment started. We then divided the mice into cages with 2 mice in each. All mice were treated with 1% ampicillin, 1% neomycin, 1% vancomycin, and 1% metronidazole (antibiotics; Abx) for 14 days, followed by inoculation with Coriobacteria or sterile water (from day −21 to −7). All mice received drinking water for 7 days (from day−7 to 0) after inoculation with bacteria. Schema of the experiment and body weight on day 7 (G) and DAI score (n = 4 in each group, combined 2 independent experiments). P-values obtained via the Student t-test (G), analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test (A−E). Data are shown as standard error of the mean.

Supplementation of Single D-aa Ameliorates Experimental Colitis

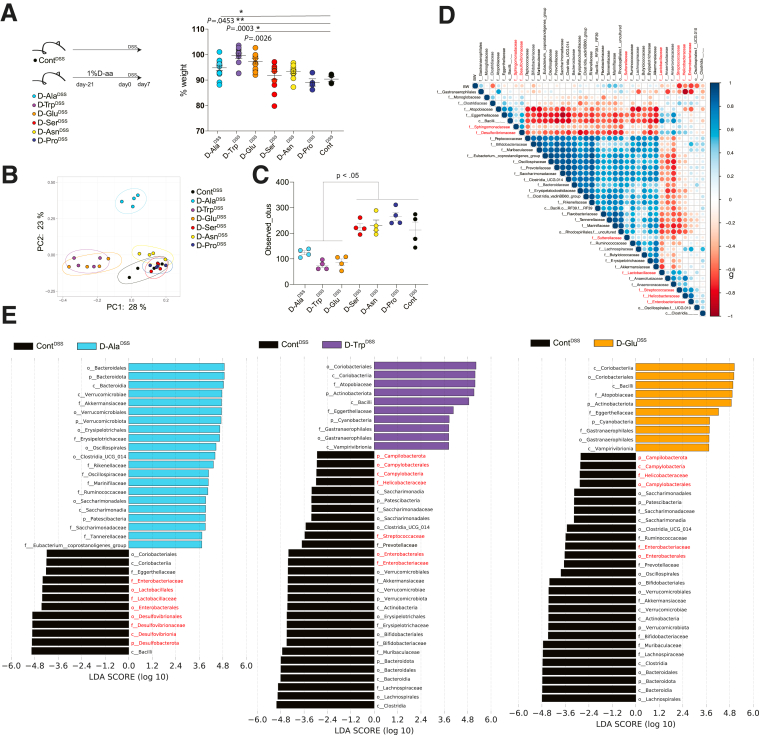

We next assessed which D-aa were involved in the suppression of colitis in vivo. We treated WT mice with 1% D-Ala, D-Trp, D-Glu, D-Ser, D-Asn, or D-Pro or without any D-aa for 3 weeks prior to 7 days of 2% DSS challenge (D-trpDSS, D-alaDSS, D-gluDSS, D-serDSS, D-asnDSS, D-proDSS, ContDSS mice). D-alaDSS, D-trpDSS, and D-gluDSS mice showed ameliorated DSS colitis compared with ContDSS mice (Figure 4A). As expected, colitis-suppressed D-alaDSS, D-trpDSS, and D-gluDSS mice showed different microbial compositions to colitis-unsuppressed D-serDSS, D-asnDSS, D-proDSS, and ContDSS mice based on PCoA plots of unweighted UniFrac analysis (Figure 4B). The total number of OTUs was significantly reduced in D-alaDSS, D-trpDSS, and D-GluDSS mice compared with that in the other groups (Figure 4C), suggesting that colitis-suppressing D-aa supplementation reduced a particular group of pathobionts. Next, we analyzed the relationship between the microbiome and BW in D-trpDSS, D-alaDSS, D-gluDSS, and ContDSS mice. BW was negatively correlated with Gammaproteobacteria: Enterobacteriaceae; sulfate-reducing Deltaproteobacteria: Desulfovibrionaceae; biofilm-forming Betaproteobacteria: Sphingomonadaceae; and facultatively anaerobic Lactobacillaceae, Streptocococcaceae, and Helicobacteraceae (Figure 4D). Consistent with these findings, the numbers of Gammaproteobacteria, Deltaproteobacteria, and other facultative anaerobic bacteria were markedly decreased in colitis-suppressed D-alaDSS, D-trpDSS, and D-gluDSS mice compared with those in ContDSS mice (Figure 4E). The results suggested that D-ala, D-trp, and D-glu supplementation suppressed colitis by reduction of facultatively anaerobic bacteria in particular, such as Proteobacteria, by a direct action of D-aa on those bacteria.

Figure 4.

D-aa altered gut microbe composition in DSS administration. (A–E) We co-housed C57BL/6J mice from the same parents until 7 weeks old before the experiment started. We then divided the mice into cages with 2 mice in each and randomly administered 1% ala, trp, glu, ser, asn, pro. Seven-week-old C57BL/6J mice received drinking water with 1% ala, trp, glu, ser, asn, pro, or control water for 3 weeks prior to 7 days of 2% DSS challenge. Schema of the experiment and body weight on day 7 (A), PCoA plots of unweighted UniFrac distance of fecal microbiome (B), and observed OTUs after 2% DSS administration are shown (C). (D) The correlation matrix was based on the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient of the abundant bacterial family with BW. The strength of the correlation between each pair of variables is indicated by the diameter and color of the circles. A color code of dark blue indicates a positive correlation coefficient close to +1, and a color code of dark red indicates a negative correlation coefficient close to −1. Featured proteobacteria are written in red. (E) LDA scores revealed significant bacterial differences in fecal microbiota between the D-aa groups (positive score) and control groups (negative score). All experiments were performed in at least 2 replicates (n = 2–4, combined). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. P values were obtained via analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test. Data are shown as standard error of the mean.

Supplementation of D-aa Ameliorates Colitis and Cholangitis Induced by Fecal Microbiota Transplantation from Patients with UC and PSC

We further examined whether D-aa ameliorates disease activity induced by human pathobionts.

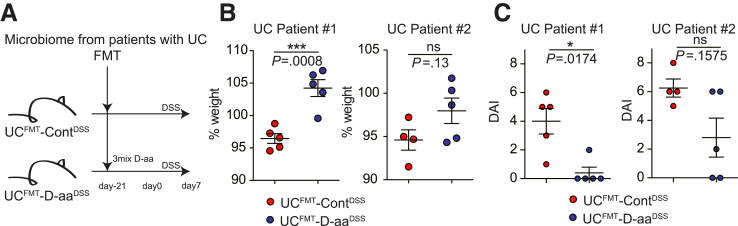

We transferred human feces obtained from pUCs (UC #1 and UC #2) to GF mice with or without 1% D-aa5-mix in drinking water prior to 7 days of 2% DSS challenge (UCFMT-ContDSS, UCFMT-D-aa5mix-DSS) (Figure 5A). UCFMT-D-aa5mix-DSS mice showed a reduced severity of DSS colitis as compared with UCFMT-ContDSS mice (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Administration of D-aa ameliorates DSS colitis in UC microbe. (A, B) UC model, GF mice were inoculated with fecal contents obtained from active UC patients (Patients #1 and #2). Then, mice received drinking water with 1% 3MIX D-aa (D-Ala, D-Trp, D-Glu) or control water. After 3 weeks of drinking water, mice were administered 2% DSS for 7 days. Study design (A) and percentage of BW on day 7 (B) are shown. DAI score is shown (C). All experiments were performed in at least 2 replicates (n = 3–6, combined). ∗∗∗P < .001. P values were obtained via the Student t-test. Data are shown as standard error of the mean.

We next assessed whether D-aa reduced the severity of cholangitis in a PSC model.21 We transferred feces obtained from a patient with PSC (pPSC) to GF mice and administered 1% D-amino acids (D-ala, D-trp, and D-glu: D-aa3mix) or sterile water for 3 weeks. Mice 3 weeks after FMT were given a diet containing 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine (DDC, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO; a chemical inducer for cholangitis) with sterile water or D-aa3mix for 2 weeks to induce cholangitis as we previously demonstrated microbiome itself from pPSC do not induce cholangitis21 (ContDDC, D-aa3mix-DDC) (Figure 6A). Total bilirubin test results and alanine amino transferase levels in the serum of D-aaDDC mice were significantly reduced compared with those in ContDDC mice (Figure 6B). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining showed that inflammatory cell infiltration was reduced in the livers of D-aa3mix-DDC mice (Figure 6C). Moreover, Sirius red staining indicated that liver fibrosis was reduced in the livers of D-aa3mix-DDC mice compared with those of ContDDC mice (Figure 6D). We then analyzed the total numbers of K. pneumoniae, P. mirabilis, and E. gallinarum, which were previously reported as pathological microbes of the Proteobacteria in pPSCa.21 As expected, the total number of the Proteobacteria K. pneumoniae and P. mirabilis was significantly lower in D-aa3mix-DDC mice than in ContDDC mice. In addition, the total number of E. gallinarum tended to decrease in D-aa3mix-DDC mice compared with that in ContDDC mice (Figure 6E).

Figure 6.

D-aa ameliorate the colitis and liver cholangitis by modulating microbiome. (A–E) UC/PSC model, GF mice, FMT from patients with PSC/UC and received drinking water with 1% 3MIX D-aa (D-Ala, D-Trp, D-Glu) or control water for 3 weeks prior to 2 weeks DCC diet (D-aaDDC, ContDDC); n = 8 for 2 independent experiments (A). Serum total bilirubin (T-Bil) level and alanine transaminase (ALT) level (B), H&E-stained histological sections from liver (C), quantitative Sirius red-positive area (D), scale bar = 200 μm (C, D), and the number of KP, P. mirabilis, and EG (E) are shown. (F) FISH staining of the colon from D-aaDDC, ContDDC mice to identify the bacterial 16S rRNA genes (red), co-stained with phalloidin (F-actin, green) and 4’, 6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, blue). Insets show higher magnification. Yellow arrowheads indicate epithelial invasion of bacteria. Scale bar = 50 μm. (G) Number of invasive bacteria in epithelial colon of D-aaDDC, ContDDC mice are shown (n = 4; 2 independent experiments. Two slides were obtained from each mouse.). (H) Mucus thickness of D-aaDDC, ContDDC mice are shown (n = 4; 2 independent experiments). Measurements were repeated 2 times. (I) SEM images of monolayered organoids after 8-hour culture K. Pneumoniae-P1 (pore-forming KP) or K. Pneumoniae JCM 1662 (non-pore-forming KP) with 1% L/D-Ala are shown. Yellow arrowheads indicate damaged intestinal epithelium with pores (>10 μm, epithelial pore). Number of pores are shown. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. P values were obtained via the Student t-test (B, D, E, G, H). Data are shown as standard error of the mean.

Pathogenic K. pneumoniae species in PSCs are known to invade the intestine via pore formation in intestinal epithelial cells.21 Therefore, we performed fluorescence in situ hybridization to detect bacterial invasion in the colon of D-aa3mix-DDC and ContDDC mice. The amount of bacterial DNA detected beneath the intestinal epithelium was reduced in D-aa3mix-DDC mice compared with that in ContDDC mice (Figure 6F–G). Importantly, the thickness of the mucus layer was comparable between D-aa3mix-DDC and ContDDC mice (Figure 6H). The data indicate that supplementation of D-aa3mix ameliorates liver cholangitis by preventing bacterial invasion into the host. We lastly assessed whether D-aa inhibits K. pneumoniae-induced epithelial pore formation.21 We cultured 2 different K. pneumoniae strains, K. pneumoniae-P1 (pore-forming strain, obtained from pPSCs), and K. pneumoniae JCM 1662 (non-pore-forming strain), with a monolayer murine colonic organoid culture with L- or D-Ala. The numbers of pores in monolayer of organoids cultured with K. pneumoniae-P1 strain were more than K. pneumoniae JCM 1662 strain (Figure 6I). K. pneumoniae-P1 strain induced epithelial pores in organoids cultured with control medium or the L-Ala group, whereas D-Ala inhibited pore formation caused by K. pneumoniae-P1 (Figure 6I).

D-aa Inhibit the Growth of Proteobacteria by Repressing ftsZ Gene Expression

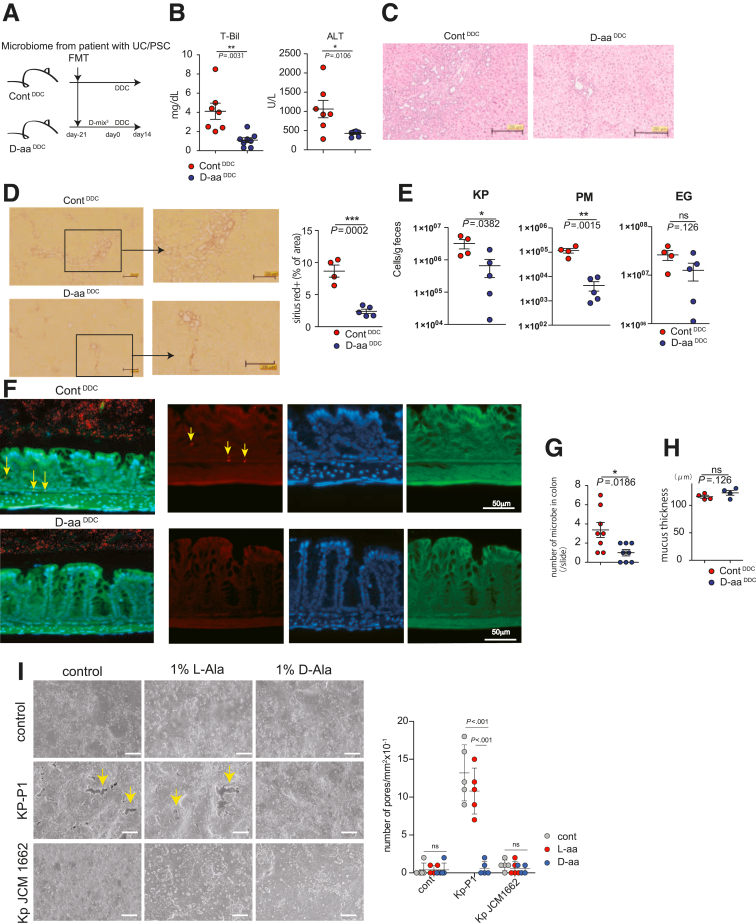

Next, we investigated how D-aa supplementation inhibits Proteobacteria. It was previously reported that Proteobacteria including E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and P. mirabilis are pathogenic in IBD. We assessed the effect of D-aa to the growth of these bacteria in addition to another pathobiont, Entercoccus galinarum21 and several well-known human probiotics.34,35 We cultured each bacterium with or without 1% D-aa, D-ala, D-trp, D-glu, D-ser, or D-asn. Although each species showed growth inhibition in the presence of specific D-aa, we noticed that the growth of the pathobiont group of Proteobacteria, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. mirabilis, and E. galinarum was more markedly suppressed in the presence of D-ala (Figure 7A–B). For the probiotic species, the effects of D-aa varied; for example, D-ser inhibited the growth of Lactobacillus reuteri but did not inhibit the growth of L. plantarum. Moreover, D-ser, but not other D-aa, facilitated the growth of Fusobacterium nucleatum, which is reported to promote colon cancer.36 With the exception of D-ala, the effect of other D-aa on E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and P. mirabilis and E. galinarum also varied. Based on these results, we have focused on the mechanism of action of D-ala, which is a major D-aa required for bacterial cell wall formation.

Figure 7.

D-Ala inhibit the growth of Proteobacteria bacteria. (A) The growth of microbiome in 1% D-aa containing medium. Each sample was collected at the indicated time points and the optical density was measured at 620 nm. ∗∗∗P < .001. P values were obtained via analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test. Data are shown as standard error of the mean. (B) Correlation between D-aa and growth of microbiota in vitro. A color code of dark blue indicates a positive correlation coefficient close to +1, and a color code of dark red indicates a negative correlation coefficient close to −1.

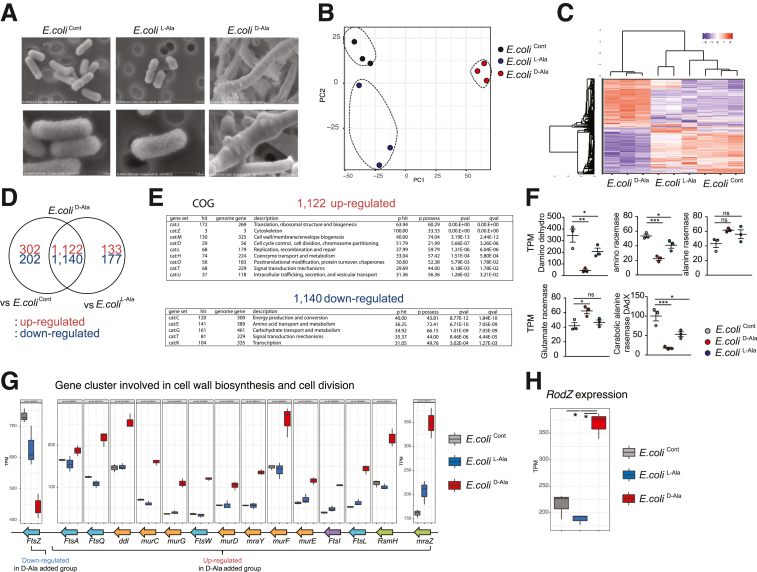

To address the molecular mechanism through which D-aa inhibits the growth of Proteobacteria, we cultured E. coli (JCM 1649) with D-ala or L-ala for 3 hours (E. coliCont, E. coliD-Ala, and E. coliL-Ala). We analyzed ultrastructure using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Figure 8A). Strikingly, E. coliD-Ala was club-shaped with a node-like structure, whereas E. coliL-Ala shapes were similar to those of E. coliCont. In a PCoA analysis of RNA expression levels (Figure 8B–C), we found that the genes expressed in E. coliD-Ala were significantly altered compared with E. coliL-Ala and E. coliCont. There were 133 upregulated and 177 downregulated genes in E. coliD-Ala compared with E. coliL-Ala and 302 upregulated and 202 downregulated genes in E. coliD-Ala compared with E. coliCont, whereas 1122 upregulated and 1140 downregulated genes were found for E. coliD-Ala compared with E. coliL-Ala and E. coliCont (Figure 8D). COG analysis indicated that cell wall membrane- and cell cycle-related genes were upregulated in E. coliD-Ala. Genes related to energy production and conversion, amino acids, carbohydrate transport, and metabolism were downregulated in E. coliD-Ala (Figure 8E), consistent with the observation that E. coliD-Ala did not grow (Figure 7A–B). The expression level of glutamate racemase in E. coliD-Ala was higher than that in E. coliCont and E. coliL-Ala, and that of alanine racemase in E. coliD-Ala was higher than that in E. coliCont and E. coliL-Ala. Other amino acid racemases, D-amino acid dehydrogenase, amino acid racemase, and catabolic alanine racemase were present in E. coliD-Ala at lower levels than in E. coliCont and E. coliL-Ala (Figure 8F).

Figure 8.

D-Ala changed the shape of E. coli with reducing ftsZ gene expression. (A) SEM images of E. coli (JCM 1649) cocultured with 1% L- or D-Ala (E. coliL-Ala/ECD-Ala) and control (E. coliCont). (B–H) Gene expression profile of each sample (B, C, D), COG pathway enrichment analysis (E). The FPKM level of each racemese gene were detected in E. coliD-Ala, E. coliCont, and E. coliL-Ala (F). Cluster of genes involved in cell wall biosynthesis and cell division (G), and RodZ expression levels (H) are shown (n = 3 in each group). P values were obtained via by analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. Data are shown as standard error of the mean.

We then investigated the expression of genes involved in cell wall biosynthesis and cell division in E. coliCont, E. coliD-Ala, and E.coliL-Ala. The expression of cell division-related operon genes mraZ to ftsA in E. coliD-Ala was significantly upregulated compared with that in E. coliCont and E. coliL-Ala. The expression level in E. coliD-Ala of ftsZ, an essential gene for the last step of cell division, was significantly downregulated compared with that in E. coliCont and E. coliL-Ala (Figure 8G). The data indicate that D-Ala inhibits gene expression affecting the last step of cell division, resulting in inhibition of E. coli growth. Moreover, the expression of RodZ gene, which is involved in determining the length of the long axis in E. coli through cytoskeletal protein control, was upregulated in E. coliD-Ala compared with E. coliCont and E. coliL-Ala (Figure 7H), suggesting that the altered gene expression results in the unique shape of E. coliD-Ala.

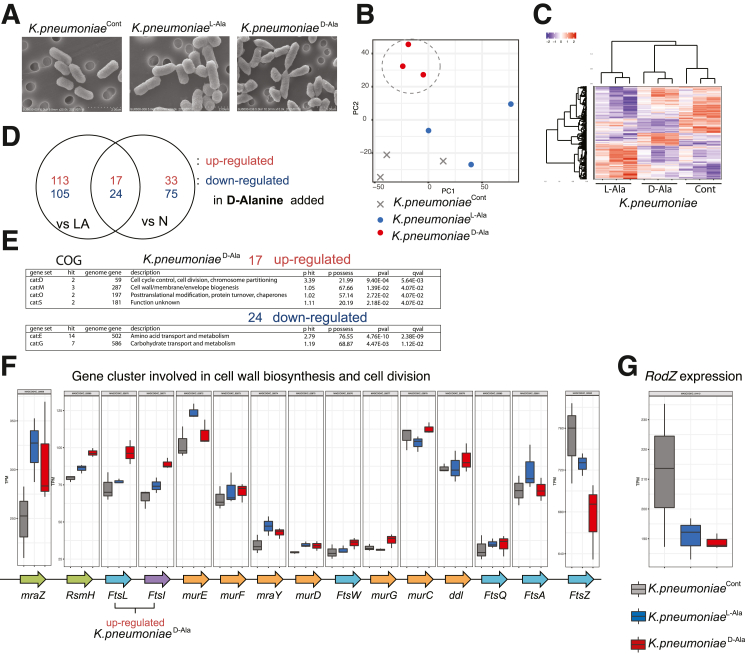

We next cultured another Proteobacteria species, K. pneumoniae, with D-ala or L-ala or without additive for 3 hours (K. pneumoniaeCont, K. pneumoniaeD-Ala, and K. pneumoniaeL-Ala) and compared gene expression levels. SEM analysis revealed that K. pneumoniaeD-Ala has an irregular cactus-leaf-like shape compared with K. pneumoniaeL-Ala and K. pneumoniaeCont (Figure 9A), but the morphological change did not resemble that of E. coliD-Ala. PCoA analysis of each K. pneumoniae group indicated that K. pneumoniaeD-Ala was distinct from K. pneumoniaeCont and K. pneumoniaeL-Ala (Figure 9B). Differential expression of genes analysis indicated that 17 genes were increased in K. pneumoniaeD-Ala as compared with K. pneumoniaecont and K. pneumoniaeL-Ala (Figure 9C–D). COG analysis suggested that genes related to cell cycle and cell wall biogenesis were significantly upregulated in K. pneumoniaeD-Ala (Figure 9E). Expression of the ftsZ gene in K. pneumoniaeD-Ala was significantly reduced compared to that in K. pneumoniaeCont and K. pneumoniaeL-Ala, similar to observations in E. coliD-Ala. Unlike in E. coliD-Ala, RodZ gene expression in K. pneumoniaeD-Ala was significantly downregulated compared to that in K. pneumoniaeCont (Figure 9F–G). Therefore, rodZ gene expression changes induced by D-ala were not constant across bacterial types, whereas ftsZ gene expression was generally reduced in both E. coli and K. pneumoniae by D-ala treatment. The data suggest that D-ala downregulation of ftsZ expression in E. coli and K. pneumoniae results in the inhibition of bacterial growth and the morphological changes.

Figure 9.

D-Ala reduces the FtsZ gene expression in K. pneumoniae. (A–G) SEM images. (A) of K. pneumonia cocultured with 1% L/D-Ala (K. pneumoniaeL-Ala/K. pneumoniaeD-Ala) and control (K. pneumoniaeCont). (B–D) Gene expression profile of each sample (KPL-Ala, KPD-Ala, KPCont). (E) COG pathway enrichment analysis. (F) Expression of genes involved in cell wall biosynthesis and cell division. (G) RodZ expression levels are shown. P values were obtained via analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. Data are shown as standard error of the mean.

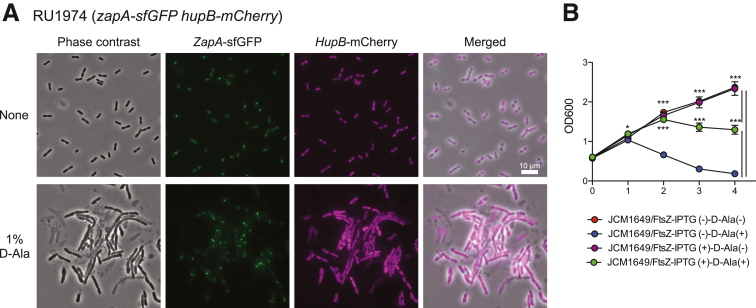

FtsZ protein is essential for bacterial division; therefore, we investigated whether D-ala treatment results in a failure to assemble the FtsZ protein at a specified location inside the bacterial cell wall. To visualize FtsZ localization, we examined the Zap-AGFP protein, which interacts with FtsZ in E. coli (Figure 10A). Zap-AGFP protein was detected normally in E. coliD-Ala, with results similar to those in E. coliCont, indicating that D-ala does not disrupt the localization of FtsZ. We next addressed whether the amount of ftsZ expression of E. coli under D-ala condition. We generated a strain of E. coli that continuously expressed the ftsZ gene after adding isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (E. coliFisZ). We cultured E. coliFisZ in the presence of D-ala (E. coliFisZ-D-Ala) and compared with E. coliCont with or without D-ala (E. coliCont-D-Ala , E. coliCont). OD600 of E. coliCont and E. coliFisZ was increased after the culture, whereas OD600 of E. coliCont-D-Ala was less compared with E. coliCont and E. coliFisZ. Interestingly, while the growth of E. coliFisZ-D-Ala was not fully recovered compared with E. coliCont and E. coliFisZ, E. coliFisZ-D-Ala partially grow in the presence of D-ala more compared with E. coliCont-D-Ala (Figure 10B). Taken together, the data suggest that D-ala inhibits FtsZ function in E. coli by reducing ftsZ gene expression, resulting in suppressed growth in E. coli.

Figure 10.

D-Ala inhibit the growth of E. coli with reducing ftsZ gene expression. (A) RU1974 cells producing Zap-A-sfGFP and HupB-mCherry were visualized by microscope. LB culture medium (upper panel), LB culture medium with 1% D-ala (lower panel). GFP and mCherry were detected by fluorescent microscope. (B) Changes in ftsZ expression in E. coli (JCM 1649) induced with IPTG and cocultured with or without 1% D-ala. The samples were collected at the indicated time points, and the optical density was measured at 600 nm. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. P values were obtained via analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test (B). Data are shown as standard error of the mean.

D-ala Inhibits the Generation and Growth of Antibiotic-resistant Bacteria

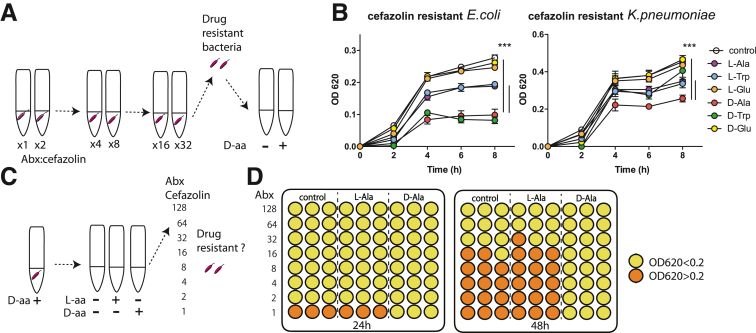

Continuous use of antibiotics in humans has led to the rise of an antibiotic resistance problem worldwide. Therefore, we investigated whether clinical usage of D-aa would inhibit the growth of antibiotic-resistant bacteria or produce resistant bacteria in a similar manner to antibiotic-resistant bacteria arising as a result of long-term antibiotic use. We generated cefazolin-resistant E. coli and K. pneumoniae cells using 48-hour cefazolin treatment (Figure 11A). We cultured them in the presence of cefazolin with L- or D-ala, -trp, and -glu. As expected, D-ala and D-trp inhibited the growth of cefazolin-resistant E. coli. D-ala also inhibited cefazolin resistance in K. pneumoniae (Figure 11B). The data indicate that D-ala has the potential to inhibit the growth of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Figure 11.

D-Ala inhibits the growth of drug-resistant bacteria and suppresses the generation of drug-resistant strains. (A) Selection for an antibiotic-resistant microbiome. (B) Growth of cefazolin-resistant E. coli and K. pneumoniae in the presence of D-aa. ∗∗∗P < .001. (C, D) Testing effects of D-Ala on the development of cefazolin resistance in E. coli; results are shown as optical density at 620 nm, color-coded above and below a value of 0.2. Three independent experiments; representative data are shown.

We then investigated whether long-term use of D-ala induced generation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (Figure 11C). We first cultured E. coli with or without D-ala or L-ala, and then cultured them with cefazolin from 48 to 96 hours. E. coli cultured with D-ala was not detected in cefazolin-resistant bacteria after 96 hours, whereas E. coli cultured with L-ala gave rise to cefazolin-resistant bacteria within the span of 48 to 96 hours post culture (Figure 11D). The data suggest that D-ala has potential to inhibit antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Discussion

In this study, we found that oral supplementation with D-aa, which is present at lower levels in the feces of pUCs, suppresses the growth and functional activity of Proteobacteria that show increased abundance in pUCs. Furthermore, this growth suppression was regulated by downregulation of gene expression for ftsZ, a critical gene in bacterial cell division. Thus, this study proposes a mechanism for D-aa-mediated symbiosis in the gut microbiota community and suggests the possibility of developing a novel treatment for dysbiosis-related diseases using D-aa supplementation or D-aa-producing probiotics (Graphical Abstract).

Gut microbes produce D-aa, including D-ala, D-asp, D-glu, and D-ser.9, 10, 11 Previously, D-aa including D-ala were shown to be increased in ex-GF mice compared with GF mice.27 Based on this background, we first established a correlation between the microbiota community and the ratio of D-aa to L-aa. Importantly, microbes detected in healthy donors have a positive correlation with the ratio of D-aa to L-aa, whereas Proteobacteria detected in pUCs have a negative correlation with the ratio of D-aa to L-aa.

It is well-known that microbes produce various beneficial metabolites (for example, short chain fatty acids such as acetate, butyrate, and propionate) with an ability to induce peripheral T regulatory cells and interleukin-10 macrophages,20 bile acids such as 3-oxo-LCA with an ability to induce T regulatory cells,37 polyamine that can induce anti-inflammatory macrophages,38 and tryptophan metabolite that can suppress intestinal inflammation.39 However, it is largely unknown how microbes themselves shape the normal symbiotic niche and prevent diseases. Because mammalian intestinal epithelial cells possess D-aa oxidase to metabolize D-aa and thereby reduce the microbial burden in the small intestine, D-aa have been thought to be harmful to mammals.40 However, we here demonstrate that D-aa, especially D-ala, inhibit the growth of Proteobacteria such as E. coli and K. pneumoniae but not the Bacteroides group, resulting in amelioration of UC-related experimental colitis and liver cholangitis. Our study suggests that supplementing specific D-aa may be a useful therapeutic approach in inhibiting harmful bacteria.

We here demonstrated that D-ala-induced inhibition of the growth of Proteobacteria is mediated by inhibition of ftsZ gene expression, associated with the last step in bacterial cell division and resulting in altered morphology of E. coli and K. pneumoniae. Importantly, overexpression of the ftsZ gene partially restored the growth of E. coli even in D-ala-containing culture medium. The downregulation of ftsZ gene is one of the candidate genes when D-ala suppresses the growth of E. coli. The ftsZ gene in E. coli is located at the distal end of a complex gene cluster comprising 17 genes involved in cell division and cell wall synthesis (dcw gene cluster).41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 Six promoters within the immediately upstream ftsA, ftsQ, and especially ddlB genes contribute to ftsZ expression.47,48 However, E. coliD-Ala expressed higher levels of dcw gene cluster ftsA, ftsQ, and ddlB, so further study will be needed to determine how D-ala reduces ftsZ gene expression without cis regulation. Although we have not determined the precise mechanism by which D-ala modulates FtsZ and subsequent cell division, the present results suggest the possibility that D-aa could be used to balance probiotics vs pathobionts to maintain symbiosis in healthy donors.

We observed that D-aa inoculation did not ameliorate DSS colitis in Myd88-/- mice. Myd88 plays a crucial role in the host defense against bacterial infections, such as Citrobacter rodentinum.49 These data suggest that D-aa inoculation modulates TLR signaling, resulting in reduced colitis. Although the precise molecular mechanism by which D-aa alters the TLR signal in the host remains unknown, we raised 2 possibilities: (1) D-aa modulates bacterial composition, resulting in altered bacterial composition ameliorating colitis via TLR signaling in the host; and (2) D-aa modulates bacterial functional genes, including ftsZ, adhesion-related, or invasion-related genes, leading to amelioration of colitis through TLR signaling. Further studies are needed to investigate whether invasive or adhesion proteins in pathogenic bacteria are controlled by D-aa.

There are only limited antibiotic and FMT therapies available for IBD and IBD-related disease such as PSC-UC.50, 51, 52, 53, 54 One reason is that, to date, there has been no efficient way to reduce harmful gut bacteria without affecting beneficial microbiota. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria may play a role in disease progression, as has been noted in Crohn’s disease.24 Our data show that D-aa supplementation suppressed inflammation in UC and PSC gnotobiotic models based on human intestinal bacteria, suppressing only harmful intestinal bacteria without generating antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Notably, we have the limitations of our study: (1) we selected E. coli and K. pneumonia and did not test other bacteria; and (2) we cultured microbes with specific concentration and duration of D-aa in vivo and in vitro, so an adequate dose should be determined when used in clinical application in humans.

Although further studies are needed to investigate the susceptibility of additional bacterial species to D-aa, determine a specific D-aa supplementation strategy, and identify D-aa-secreting microbiota that inhibit harmful bacteria in dysbiosis-related diseases, the results at hand suggest that D-aa represents a potentially useful therapeutic approach not only for various dysbiosis-inducing modern diseases but also for infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Material and Methods

Consent and Ethics Approval

Patients with UC

Blood samples and fecal samples were obtained from active patients with UC. Samples were immediately stored at −80 °C. UC was diagnosed by the criteria defined by the Research Group of Inflammatory Bowel Disease at the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare in Japan. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Keio University School of Medicine, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients with PSC/UC

Fecal samples were obtained from patients with PSC/UC. The diagnosis of PSC was made according to clinical guidelines and typical findings on cholangiography (endoscopic retrograde cholangiography and/or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography) or liver biopsy. The diagnosis of UC was based on a combination of endoscopy, histopathology, and radiological and serological investigations. The ethics committee at Keio University School of Medicine (Tokyo, Japan) approved the protocol (no. 20140211), in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants. The study is registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) clinical trial registration system (UMIN 000018068).

Animals

Male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from CLEA Japan (Tokyo, Japan). Male MyD88KO and male RAG2KO mice were purchased from JLA (Tokyo, Japan). Male GF mice were purchased from Sankyo Labo Service (Tokyo, Japan). Mice, except for GF mice, were maintained under SPF conditions. GF mice were bred and maintained in vinyl isolators. Genotyping was performed according to the protocols established for each strain by Jackson Laboratories. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Review Board for Animal Experiments at Keio University and were performed according to the institutional guidelines and home office regulations.

Induction of Colitis by DSS

We co-housed C57BL/6J, Myd88-/-, and Rag2-/- mice from the same parents until 7 weeks old before the experiment started. We then divided the mice into cages with 2 mice and randomly administered with or without 1% D-aa or L-aa. Colitis was induced by the addition of 2% (w/v) DSS (molecular weight: 36,000-50,000; MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) to the sterile drinking water given to mice. On day 6 to 7 after DSS administration, the supplementation was discontinued or changed to water for 1 to 2 days, and the mice were sacrificed. Clinical assessment of all DSS-treated animals for BW and general appearance was performed daily. SPF mice were weighed every day to determine percentage of BW loss from baseline. BW loss, stool consistency, and rectal bleeding were evaluated and scored for DAI. No weight loss was registered as 0, weight loss of 1% to 5% from baseline was assigned 1 point, weight loss of 6% to 10% from baseline was assigned 2 points, weight loss of 11% to 20% from baseline was assigned 3 points, and weight loss of more than 20% from baseline was assigned 4 points. For stool consistency, 0 points were assigned for well-formed pellets, 2 points for pasty and semiformed stools that did not adhere to the anus, and 4 points for liquid stools that adhered to the anus. For bleeding, 0 was assigned for no blood, 2 points for positive bleeding, and 4 points for gross bleeding. The colon was excised, and the length documented. The degree of inflammation and epithelial damage was determined by microscopic examination of H&E-stained sections of the colon as described below.

Adoptive Transfer of Inflammation

We co-housed Rag2-/- mice from the same parents until 7 weeks old before the experiment started. We then divided the mice into cages with 2 mice and randomly administered with or without 1% D-aa. CD4+ T cells were isolated from the spleens of C57BL/6J (Ly5.1+) mice using the anti-CD4 (L3T4) MACS magnetic separation system (Miltenyi Biotec). Enriched CD4+ T cells were stained with CD4, CD45Rb, and CD25 mAbs, and were then sorted to yield the CD4+CD25-CD45Rbhigh fraction using a FACS AriaTM (Becton Dickinson). Purified CD4+CD45Rbhigh (3.0 × 105 cells/mouse) alone were intraperitoneally injected into RAG2KO mice. Mice were sacrificed at the indicated time point after transfer.

Histology

A distal colon section after DSS-induced colitis and fixed with 10% formalin (Wako, Tokyo, Japan). The fixed samples were embedded in paraffin, and stained with H&E at Morphotechnology (Sapporo, Japan). To evaluate the severity of DSS-induced colitis, histological activity score31,33 (maximum total score, 40) was assessed as the sum of 3 parameters: extent, inflammation, and crypt damage as follows: extent: scored 0 to 3 (0, none; 1, mucosa; 2, submucosa; 3, transmural); inflammation: scored 0 to 3 (0, none; 1, slight; 2, moderate; 3, severe); crypt damage: scored 0 to 4 (0, none; 1, basal one-third lost; 2, basal two-thirds lost; 3, only surface epithelium intact; 4, entire crypt and epithelium lost) were multiplied by scores of spreads that were from 1 to 4 (1, 0–25%; 2, 26%–50%; 3, 51%–75%; 4, 76%–100%). Each multiplied score was summed and defined as a histologic score (0–40). To evaluate the severity of the adoptive transfer colitis, the most affected area of pathological specimens was assessed for a histological score as the sum of 3 criteria: cell infiltration, crypt elongation, and the number of crypt abscesses. Each was scored on a scale of 0 to 3 in a blinded fashion.

ELISA for Lipocalin-2

Lipocalin-2 was analyzed using an Lcn-2 ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Fecal Microbiome Transplantation

Feces were obtained from C57BL/6J mice and stored at −80 °C until use. The feces were dissolved in 1.5 mL phosphate buffered saline (PBS), homogenized, then filtered through a 100-μm nylon mesh strainer (Corning, Tewksbury, MA). The filtered contents were resuspended with PBS in a total volume of 2 mL, of which 150 μL per mouse was administered to GF mice in the vinyl isolator by oral gavage.

DDC-induced Experimental Hepatobiliary Inflammation and Liver Fibrosis

To induce hepatobiliary inflammation and liver fibrosis, humanized gnotobiotic mice were freely fed a 0.033% DDC-enriched diet for 14 days, followed by serological, histological, and immunological assessment.

Three-dimensional and Monolayer Culture of Human Colonic Epithelium

Human healthy colonic organoids were previously established. The ethics committee at Keio University School of Medicine (Tokyo, Japan) approved the protocol (no. 20140211). Three-dimensional colonic organoids were maintained with modified human colonic organoid (MHCO) medium, consisting of advanced Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/F12 supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin, 10 or 100 mM HEPES, 2 mM Glutamax, 1 × B-27 Supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), 10 nM gastrin I (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), 1 mM N-acetylcysteine (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 ng/mL recombinant mouse Noggin (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), 50 ng/mL recombinant mouse epidermal growth factor (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 100 ng/mL recombinant human insulin-like growth factor-1 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA), 50 ng/mL recombinant human fibroblast growth factor-basic (FGF-2) (PeproTech), 1 μg/mL recombinant human R-spondin1 (R&D, Minneapolis, MN), 500 nM A83–01 (Tocris, Bristol, UK), 10 μM Y-27632 (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan), and 20% Afamin-Wnt-3A serum-free conditioned medium. Undifferentiated medium of human colonic organoid was made by additional 3 μM SB202190 (Sigma-Aldrich) and 10 mM nicotinamide (Sigma-Aldrich) into MHCO medium. Organoids were passaged approximately every week by physical dissociation using fire-polished Pasteur pipettes. To generate monolayers derived from 3-dimensional culture of human colonic organoids, transwell culture inserts (24-well insert, 0.4 μm pore polyester membrane; Greiner bio-one, Kremsmunster, Austria) were coated with 5% Matrigel diluted with advanced Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/F12 medium and incubated at 37 °C for 30 minutes, then Matrigel solution was removed and the membrane was dried in a tissue-culture hood for 15 minutes. Human colonic organoids were cultured for 5 to 7 days before being used to plate into monolayer culture in MHCO medium. Three-dimensional cultured organoids were treated with TrypLE Express (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to dissociate into single cells. The cells were resuspended to 1 to 2 × 106 cells/mL in MHCO medium, and 200 μL of cell suspension was added into the transwell inserts. The medium was changed every 2 days until cells were growing as confluent epithelial monolayers.

Localization of Bacteria by FISH and Measurement of Mucus Thickness

Colon and ileal tissues containing fecal material were fixed with Carnoy’s solution for 3 hours. Paraffin-embedded sections were de-waxed and hydrated. The hybridization step was performed at 50 °C overnight with an EUB338 probe (5′-GCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT-3′, with an Alexa 555 label) diluted to a final concentration of 10 μg/mL in hybridization buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.9 M NaCl, 0.1% SDS, and 20% formamide). After washing for 10 minutes in wash buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and 0.9 M NaCl) and 3 times for 10 minutes in PBS, samples were stained with phalloidin-iFluor 488 (Abcam). After washing 3 times for 10 minutes in PBS, slides were mounted using Prolong antifade mounting media with DAPI (Life Technologies). Microscopic observations were performed using a BIO-REVO BZ-9000 fluorescence microscope (Keyence). Mucus thickness was measured as the distance between the top of the epithelium and the intestinal microbes in the lumen at 3 points on each slide and the calculation averaged.

Bacterial Culture

All bacterial strains were streaked from frozen stock on GAM Agar, Modified (Nissui) in an anaerobic chamber and incubated at 37 °C in the chamber. A single colony was inoculated into 5 mL of GAM broth, Modified (Nissui) and incubated anaerobically for 48 hours at 37 °C. A 100-μL volume of this culture was transferred into a fresh tube of 5-mL GAM broth and incubated at 37 °C in the chamber until the stationary phase was reached. Optical density was measured at 620 nm. Finally, absorbance was normalized between 0 and 1.0. Heatmaps were generated in R packages using gplots (v 3.0.4) and pals (v 1.6).

Isolation of Coriobacteriales Bacterium

Coriobacteriales bacterium was isolated from fecal samples of D-aa mice that were aseptically spread on GAM Agar, modified (Nissui) containing 50 mg/L Polymyxin B. The strain was cultured in an anaerobic chamber at 37 °C for 48 hours. Forty-eight colonies were suspended in 1 mL of TE buffer and boiled for 10 minutes. After centrifugation at 9000 g for 1 minute, the supernatants were used as templates for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification. Amplification was performed in a 50-mL reaction mixture containing KOD one PCR Master Mix (Toyobo), 10 pmol of each forward primer 5’-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3’ and reverse primer 5’-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3’, and 1 mL of the template. PCR was performed under the following conditions: preincubation at 95 °C for 3 minutes, 35 cycles consisting of 95 °C for 30 seconds, annealing at 55 °C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72 °C for 1.5 minutes performed, followed by a final extension step of 5 minutes at 72 °C. PCR amplicons were purified using AMPure XP. The 16S rRNA was sequenced using BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit and ABI PRISM 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The isolated bacteria were grown in GAM broth, modified (Nissui), and stored in 20% glycerol at −80 °C.

16S rRNA Metagenomic Analysis

Fecal samples were collected fresh for determination of microbial composition and stored at −80 °C. The hypervariable V3–V4 regions of the 16S rRNA gene were amplified using Ex Taq Hot Start (TaKaRa, Kusatsu, Japan) and subsequently purified using AMPure XP (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). Approximately equal amounts of each amplified DNA were then sequenced using the Miseq Reagent Kit V3 (600 cycle) and the Miseq sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequences were analyzed using the QIIME2 software package version 2019.10 (https://qiime2.org). Forward and reverse reads were joined, denoised, and chimera-checked using QIIME2 commands (“qiime dada2 denoise-paired”). Taxonomy was picked against silva-132-99-nb-classifier.qza (https://www.arb-silva.de/download/archive/qiime). Statistical analyses for alpha diversity metrics and generation of PCoA plots for beta diversity metrics were also done through QIIME2 commands (qiime diversity “core-metrics-phylogenetic,” “alpha-group-significance,” and “beta-group-significance”). Sampling depth (--p-sampling-depth) was set to the minimum number of remaining read counts among samples. PCoA was expressed by the qiime2R (v 0.99.13) and ggforce (v 0.3.1) packages in R software (v 3.6.1). Taxa-barplot was generated using R package qiime2R (v 0.99.13), phyloseq (v 1.30.0), and microbiomeR (v 0.3.2). The enriched bacteria in each group were identified by linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe); LDA values >2 were considered significant. Correlation plot was generated using R package corrplot (v 0.84).

Fecal Microbiome Quantification by Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

Quantification of K. pneumoniae was performed using the K. pneumonia-EASY genesig kit (Primerdesign Ltd, Dayton, OH), PrecisionPLUS qPCR Master Mix (Primerdesign) and the CFX96 real time system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantification of E. gallinarum and P. mirabilis was performed using KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR Master Mix (Bio-Rad) and the CFX96 real time system. The primer sets used in this study were as follows: E. gallinarum forward 5′-TTACTTGCTGATTTTGATTCG-3′ and reverse 5′-TGAATTCTTCTTTGAAATCAG-3′; P. mirabilis forward 5′-GTTATTCGTGATGGTATGGG-3′ and reverse 5′-ATAAAGGTGGTTACGCCAGA-3′

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Graph-Pad Prism software version 8.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). The results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. Groups of data were compared with parametric one-way analysis of variance test with the Turkey post hoc analysis, unpaired parametric Student t-test, except for the principal coordinate analysis for the gut microbiome. The differences in the principal coordinate analysis were analyzed with the Permanova test. The difference was considered significant when the P value was less than .05.

Amino Acids

All amino acids were purchased from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan.

Visualization of ZapA in E. coli

RU1974 cells producing ZapA-sfGFP and HupB-mCherry were grown in Luria broth (LB) medium overnight at 37 °C. The cells were diluted 100-fold in LB or LB containing 1% D-alanine and grown for 2 hours at 37 °C. Then, cells were observed by an inverted fluorescent microscope (Axio Observer, Zeiss).

ftsZ-overexpressing E. coli

The ftsZ-overexpressing strain ECFisZ was constructed as follows. The ftsZ gene, which has a FLAG tag at its C-terminus was amplified by PCR using primers (Former: CCGGAATTCATGTTTGAACCAATGGAACT and Reverse: CGCGGATCCTTACTTGTCATCGTCGTCCTTGTAGTCATCAGCTTGCTTACGCAGG) with chromosome of E. coli JCM1649 as a template, and cloned into EcoRI-BamHI site of pTB-101 derivative plasmid pTB-101-Km vector.55 The resulting plasmid pTB-FtsZ-FLAG, which encodes the FtsZ under the control of IPTG-inducible ptac promoter, was introduced into E. coli JCM1649 (ECFisZ). Bacterial growth was measured as follows. Bacterial cultures incubated overnight at 37 °C were diluted 1:50 in LB broth and subcultured for 1 hour 15 minutes at 37 °C. In the case of ftsZ overexpression, expression was induced by the addition of IPTG. After that, the bacterial cultures were cultured in the presence or absence of D-Ala. Samples were collected at indicated time points and measured optical density at 600 nm.

Cefazolin-resistant Bacteria Culture

Bacteria were aliquoted into 2 mL microcentrifuge tubes, and cefazolin was added to each at a concentration of 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, or 128 μg/mL in GAM broth liquid medium. Cells were cultured for 48 hours at 37 °C in a 96-well plate. The minimal inhibitory concentration was determined visually after 48 hours culture, then subculturing was performed in a new 96-well plate from borderline susceptible concentration (half-minimal inhibitory concentration) samples from the plate. Subculturing was repeated for multiple rounds.

Bacterial Genome Analysis

The assembled genomic sequence and the gene annotation files of Escherichia coli JCM 1649 were downloaded from NCBI (RefSeq assembly accession: GCF_003697165.2). The contigs of Klebsiella pneumoniae KP-PSC1 assembled in our previous study was downloaded from NCBI (RefSeq assembly accession: GCF_003851825.1). The gene prediction was performed for the K. pneumoniae KP-PSC1 contigs using prokka (version-1.14.0) with rnammer (version-1.2). The blastx homology searches for the CDS DNA sequences of E. coli JCM 1649 and K. pneumoniae KP-PSC1 against the KEGG (2021/02/10 downloaded)4 and the COG databases (2021/05/19 downloaded) were performed by DIAMOND (version-0.9.30; with --max-target-seqs 1 --evalue 0.00001 --id 30 --query-cover 60 --more-sensitie options). The NCBI gene annotations for E. coli JCM 1649 were extracted from the gene annotation file. The annotations for K. pneumoniae KP-PSC1 were obtained by performing the DIAMOND blastx search for the NCBI nr database (2020/02/04 downloaded). The proteome sequences of E. coli JCM 1649 and K. pneumoniae KP-PSC1 were clustered by CD-HIT (version-4.8.1; with -c 0.6 -S 60 options) to define the common proteins between the 2 strains.

Bacterial Transcriptome Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from bacterial cells in exponential phase grown aerobically in GAM broth (Nissui) at 37 °C, using NucleoSpin RNA (MACHEREY-NAGEL). Libraries for RNA sequencing were prepared with TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep (Illumina Inc) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The libraries were sequenced by HiSeq X (Illumina Inc) with the mode of 2× 150 bp. The Illumina sequencing adapters and the low-quality ends of sequenced reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic (version-0.39) with the options “ILLUMINACLIP:TruSeq3-PE-2.fa:2:30:10 LEADING:3 TRAILING:20 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15 MINLEN:30.” The low-quality reads were filtered using FASTAX-Toolkit (version-0.0.13; http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/index.html) with the options “-q 20 -p 80,” and the reads that became unpaired during this process were removed. The remaining paired reads were mapped to the mouse (mm10) and phix reference genomes using minimap2 (version-2.17-r941) with the options “-N 1 -a -x sr.” Then, the reads unmapped to the mouse and phix genomes were extracted to obtain the quality-controlled reads for the downstream analyses. The quality-controlled paired-end reads were mapped to the genomic sequence of E. coli JCM 1649 or K. pneumoniae KP-PSC1 using bowtie2 (version-2.4.2; with --local option), and the mapped read counts for each CDS were calculated by featureCounts (version-1.5.2; with -t CDS -p -B -Q 1 options). The transcripts per million of each CDS was calculated for the box-plots, and the scaled transcripts per million values were used for the principal component analysis. The differential expression analysis was performed by DESeq2 (version-1.30.1), and the P-values were corrected by the Benjamini-Hochberg method to control the false discovery rate below 5%. For the hierarchical clustering analysis with group average method, the Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated among samples/genes from the variance-stabilizing transformations values obtained from the DESeq2 output. The enrichment analysis for the differentially expressed genes was performed by the hypergeometric testing. To obtain the parameters of the hypergeometric distribution, the number of genes included in each gene set in the KEGG and the COG databases was counted for each of E. coli JCM 1649 and K. pneumoniae KP-PSC1 genomes.

Scanning Electron Microscopy for Analysis of Shapes of Bacterial Cells

Overnight culture of bacterial cells was diluted 1:100 in GAM Broth (Nissui) supplemented with 1% each amino acid and incubated aerobically at 37 °C for 3 hours. The cells were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical) solution on ice for 10 minutes, harvested by centrifugation at 4000 ×g for 2 minutes, and then resuspended in freshly prepared 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution. Bacterial suspension was spotted on a Nano Percolator membrane (JEOL). Samples were washed in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4, Muto Pure Chemicals), fixed with 1.0% osmium tetroxide (TAAB Laboratories) for 2 hours at 4 °C, and treated with a series of increasing concentrations of ethanol. The samples were dried up with a critical point dryer (CPD300, Leica Biosystems) and coated with about 2-nm thickness of osmium using a conductive osmium coater (Neoc-ST, Meiwafosis). SEM images were acquired using the SU6600 (Hitachi High Tech) at an electron voltage of 5 keV.

Bacterial Strains

E. coli JCM1649, E. faecalis JCM5803, L. plantarum JCM1149, B. coccoides JCM1395, C. clostridioforme JCM1291, C. ramosum JCM1298, B. longum JCM1217, B. adolescentis JCM1275, and C. aerofaciens JCM10188 were obtained from JCM (Japan Collection of Microorganisms). L. reuteri ATCC23272, S. anginosusATCC33397, B. fragilisATCC25285, and F. nucleatum ATCC25586 were obtained from ATCC. K. pneumoniae P1, P. milabillis P1, and E. gallinarum P1 are isolated from the patients with UC-associated PSC.21 Coriobacteria is isolated from D-aa5mix mice.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by JSR Corporation as a JKiC Strategic Project. The authors thank Yungi Kim (Keio University) for critical review of the manuscript.

Satoko Umeda and Kentaro Miyamoto contributed equally to this work.

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Satoko Umeda, MD (Data curation: Lead; Formal analysis: Lead; Methodology: Equal; Writing – original draft: Supporting)

Tomohisa Sujino, MD, PhD (Conceptualization: Lead; Data curation: Equal; Formal analysis: Equal; Funding acquisition: Lead; Investigation: Lead; Supervision: Lead; Writing – original draft: Lead)

Kentaro Miyamoto, BS (Data curation: Equal; Formal analysis: Lead; Methodology: Lead; Project administration: Equal; Writing – original draft: Supporting)

Yosuke Yoshimatsu, MD, PhD (Data curation: Supporting)

Yosuke Harada, PhD (Data curation: Supporting; Formal analysis: Supporting)

Keita Nishiyama, PhD (Data curation: Supporting)

Yoshimasa Aoto, PhD (Data curation: Supporting)

Keika Adachi, PhD (Data curation: Supporting)

Naoki Hayashi, PhD (Data curation: Supporting)

Kimiko Amafuji, PhD (Data curation: Supporting)

Nobuko Moritoki, MD, PhD (Formal analysis: Supporting)

Shinsuke Shibata, MD, PhD (Formal analysis: Supporting)

Nobuo Sasaki, PhD (Formal analysis: Supporting)

Masashi Mita, PhD (Data curation: Supporting)

Shun Tanemoto, MD, PhD (Data curation: Supporting)

Keiko Ono, MD (Formal analysis: Supporting)

Yohei Mikami, MD, PhD (Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

Jumpei Sasabe, MD, PhD (Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

Kaoru Takabayashi, MD, PhD (Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

Naoki Hosoe, MD, PhD (Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

Takahiro Suzuki, MD, PhD (Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

Toshiro Sato, MD, PhD (Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

Koji Atarashi, PhD (Data curation: Supporting)

Toshiaki Teratani, PhD (Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

Haruhiko Ogata, MD, PhD (Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

Nobuhiro Nakamoto, MD, PhD (Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

Daisuke Shiomi, PhD (Data curation: Supporting)

Hiroshi Ashida, PhD (Data curation: Supporting; Formal analysis: Supporting)

Takanori Kanai, MD, PhD (Supervision: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest These authors disclose the following: Kentaro Miyamoto is an employee of Miyarisan Pham. Yoshimasa Aoto, Keika Adachi, Naoki Hayashi, and Kimiko Amafuji are employees of JSR Corporation. Masashi Mita is the founder of KAGAMI. Inc. The remaining authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (19K22624, 20H03665, 21K18272 and 23H02899 to Tomohisa Sujino, 20H00536, 23H00425 to Takanori Kanai), the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, Japan (17929894 to Tomohisa Sujino and CREST-16813798, and JP21gm1510002 to Takanori Kanai), JST Forest (21457195 to Tomohisa Sujino), the Yakult Bioscience Research Foundation (Tomohisa Sujino, Takanori Kanai), the Keio University Medical Science Fund (Sakaguchi Memorial, Fukuzawa Memorial to Tomohisa Sujino), the Takeda Science Foundation, Japan (Tomohisa Sujino, Takanori Kanai), the Mochida Memorial Foundation (2017 and 2021, Tomohisa Sujino), GSK Japan Research Grand 2021(Tomohisa Sujino) and Miyarisan Pharm Co. Ltd. Research Grant (Takanori Kanai).

Contributor Information

Tomohisa Sujino, Email: tsujino1224@keio.jp.

Takanori Kanai, Email: takagast@keio.jp.

References

- 1.James J.H., Ziparo V., Jeppsson B., et al. Hyperammonaemia, plasma aminoacid imbalance, and blood-brain aminoacid transport: a unified theory of portal-systemic encephalopathy. Lancet. 1979;2:772–775. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)92119-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eriksson L.S., Persson A., Wahren J. Branched-chain amino acids in the treatment of chronic hepatic encephalopathy. Gut. 1982;23:801–806. doi: 10.1136/gut.23.10.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright P.D., Holdsworth J.D., Dionigi P., et al. Effect of branched chain amino acid infusions on body protein metabolism in cirrhosis of liver. Gut. 1986;27(Suppl 1):96–102. doi: 10.1136/gut.27.suppl_1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neinast M.D., Jang C., Hui S., et al. Quantitative analysis of the whole-body metabolic fate of branched-chain amino acids. Cell Metab. 2019;29:417–429.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sasabe J., Myoshi Y., Rakoff-Nahoum S., et al. Interplay between microbial d-amino acids and host d-amino acid oxidase modifies murine mucosal defence and gut microbiota. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1 doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sasabe J., Suzuki M. Distinctive roles of d-amino acids in the homochiral world: chirality of amino acids modulates mammalian physiology and pathology. Keio J Med. 2019;68:1–16. doi: 10.2302/kjm.2018-0001-IR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumashiro S., Hashimoto A., Nishikawa T. Free D-serine in post-mortem brains and spinal cords of individuals with and without neuropsychiatric diseases. Brain Res. 1995;681:117–125. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00307-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kantrowitz J.T., Malhotra A.K., Cornblatt B., et al. High dose D-serine in the treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2010;121:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lam H., Oh D.-C., Cava F., et al. D-amino acids govern stationary phase cell wall remodeling in bacteria. Science. 2009;325:1552–1555. doi: 10.1126/science.1178123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cava F., Lam H., de Pedro M.A., et al. Emerging knowledge of regulatory roles of D-amino acids in bacteria. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:817–831. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0571-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolodkin-Gal I., Romero D., Cao S., et al. D-amino acids trigger biofilm disassembly. Science. 2010;328:627–629. doi: 10.1126/science.1188628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aliashkevich A., Alvarez L., Cava F. New insights into the mechanisms and biological roles of d-amino acids in complex eco-systems. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:683. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radkov A.D., Moe L.A. Bacterial synthesis of D-amino acids. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:5363–5374. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5726-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gevers D., Kugathasan S., Denson L.A., et al. The treatment-naive microbiome in new-onset Crohn’s disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:382–392. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kostic A.D., Xavier R.J., Gevers D. The microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease: current status and the future ahead. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1489–1499. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schirmer M., Franzosa E.A., Lloyd-Price J., et al. Dynamics of metatranscription in the inflammatory bowel disease gut microbiome. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3:337–346. doi: 10.1038/s41564-017-0089-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shapiro J.M., de Zoete M.R., Palm N.W., et al. Immunoglobulin A targets a unique subset of the microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2021;29:83–93.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lunder A.K., Hov J.R., Borthne A., et al. Prevalence of sclerosing cholangitis detected by magnetic resonance cholangiography in patients with long-term inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:660–669.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deneau M.R., El Matary W., Valentino P.L., et al. The natural history of primary sclerosing cholangitis in 781 children: a multicenter, international collaboration. Hepatology. 2017;66:518–527. doi: 10.1002/hep.29204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quraishi M.N., Acharjee A., Beggs A.D., et al. A pilot integrative analysis of colonic gene expression, gut microbiota, and immune infiltration in primary sclerosing cholangitis-inflammatory bowel disease: association of disease with bile acid pathways. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:935–947. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakamoto N., Sasaki N., Aoki R., et al. Gut pathobionts underlie intestinal barrier dysfunction and liver T helper 17 cell immune response in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:492–503. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Viladomiu M., Kivolowitz C., Abdulhamid A., et al. IgA-coated E. coli enriched in Crohn’s disease spondyloarthritis promote T(H)17-dependent inflammation. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf9655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garrett W.S., Gallini C.A., Yatsunenko T., et al. Enterobacteriaceae act in concert with the gut microbiota to induce spontaneous and maternally transmitted colitis. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patterson J. Effectiveness of antibiotics as a treatment option for patients with Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:S9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Selby W., Pavli P., Crotty B., et al. Antibiotics in Crohn’s Disease Study Group. Two-year combination antibiotic therapy with clarithromycin, rifabutin, and clofazimine for Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2313–2319. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Duin D., Arias C.A., Komarow L., et al. Multi-Drug Resistant Organism Network Investigators. Molecular and clinical epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales in the USA (CRACKLE-2): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:731–741. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30755-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsumoto M., Kunisawa A., Hattori T., et al. Free D-amino acids produced by commensal bacteria in the colonic lumen. Sci Rep. 2018;8 doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36244-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zuo T., Lu X.-J., Zhang Y., et al. Gut mucosal virome alterations in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2019;68:1169–1179. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-318131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halfvarson J., Brislawn C.J., Lamendella R., et al. Dynamics of the human gut microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2 doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asquith M.J., Boulard O., Powrie F., et al. Pathogenic and protective roles of MyD88 in leukocytes and epithelial cells in mouse models of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:519–529, 529.e1-2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sujino T., Kanai T., Ono Y., et al. Regulatory T cells suppress development of colitis, blocking differentiation of T-helper 17 into alternative T-helper 1 cells. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1014–1023. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sujino T., London M., Hoytema van Konijnenburg D.P., et al. Tissue adaptation of regulatory and intraepithelial CD4⁺ T cells controls gut inflammation. Science. 2016;352:1581–1586. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ono Y., Kanai T., Sujino T., et al. T-helper 17 and interleukin-17-producing lymphoid tissue inducer-like cells make different contributions to colitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1288–1297. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.07.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lozupone C.A., Stombaugh J.I., Gordon J.I., et al. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature. 2012;489:220–230. doi: 10.1038/nature11550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]