Abstract

Pseudomonas fluorescens CY091 cultures produce an extracellular protease with an estimated molecular mass of 50 kDa. Production of this enzyme (designated AprX) was observed in media containing CaCl2 or SrCl2 but not in media containing ZnCl2, MgCl2, or MnCl2. The requirement of Ca2+ (or Sr2+) for enzyme production was concentration dependent, and the optimal concentration for production was determined to be 0.35 mM. Following ammonium sulfate precipitation and ion-exchange chromatography, the AprX in the culture supernatant was purified to near electrophoretic homogeneity. Over 20% of the enzyme activity was retained in the AprX sample which had been heated in boiling water for 10 min, indicating that the enzyme is highly resistant to heat inactivation. The enzyme activity was almost completely inhibited in the presence of 1 mM 1,10-phenanthroline, but only 30% of the activity was inhibited in the presence of 1 mM EGTA. The gene encoding AprX was cloned from the genome of P. fluorescens CY091 by isolating cosmid clones capable of restoring the protease production in a nonproteolytic mutant of strain CY091. The genomic region of strain CY091 containing the aprX gene was located within a 7.3-kb DNA fragment. Analysis of the complete nucleotide sequence of this 7.3-kb fragment revealed the presence of a cluster of genes required for the production of extracellular AprX in P. fluorescens and Escherichia coli. The AprX protein showed 50 to 60% identity in amino acid sequence to the related proteases produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Erwinia chrysanthemi. Two conserved sequence domains possibly associated with Ca2+ and Zn2+ binding were identified. Immediately adjacent to the aprX structural gene, a gene (inh) encoding a putative protease inhibitor and three genes (aprD, aprE, and aprF), possibly required for the transport of AprX, were also identified. The organization of the gene cluster involved in the synthesis and secretion of AprX in P. fluorescens CY091 appears to be somewhat different from that previously demonstrated in P. aeruginosa and E. chrysanthemi.

Pseudomonas fluorescens is a very large and heterogeneous group of gram-negative bacteria, which has been subdivided into five biotypes based on an array of phenotypic characteristics (26). Members of this group have been found in large numbers either as free-living saprophytes or as spoilage-causing agents of food products derived from plants or animals. A vast majority of P. fluorescens strains are mesotrophic or psychrotrophic, but some psychrophilic members have recently been isolated from Arctic glacier environments (22). Despite the difference in optimal growth conditions, the production of extracellular proteases appears to be a common feature among members of P. fluorescens (30). The production of proteases is presumably required by the free-living saprophytes for utilization of available proteins in the environment as nutritional sources. The production of proteases by spoilage-causing strains is the key event leading to the gelation of raw milk and off-flavor of dairy products (14). Although induction of fruit and vegetable spoilage by soft rot strains of P. fluorescens (sometimes referred to as P. marginalis) is attributed mainly to the production of pectate lyases (PL) (17), one study (32) has shown that proteases produced by soft rot bacteria can induce cellular death in potato and cucumber tissues.

Four classes of endoproteases have so far been identified in living organisms. These proteases are known to be involved in a wide variety of physiological functions ranging from generalized protein degradation to more specific regulation of cellular processes such as hormone activation and transport of secretory proteins (3). Three of the four endoprotease classes, serine proteases, cysteine proteases, and metalloproteases, have been identified in bacteria. However, aspartate protease has not yet been demonstrated in prokaryotes (3). So far, it has not been determined if the type of protease produced by P. fluorescens falls into one of the above four categories.

Several studies (1, 24, 31) have been conducted to investigate the biochemical properties of proteases produced by a few P. fluorescens strains associated with spoilage of milk and dairy products (1, 8, 24, 31). The results of these studies (1, 8, 31) show that calcium is essential for the activity and stability of these proteases, but the number of extracellular proteases produced by P. fluorescens is obscure. Most investigators reported that the strains they examined produced a single protease (24, 27). However, Stepaniak et al. (31) reported that P. fluorescens AFT36 produced one major protease and trace amounts of two others. We (21) recently examined the molecular regulation of extracellular enzyme production by a soft rot strain (CY091) of P. fluorescens. During the study, we isolated a group of protease-negative mutants which were shown to be induced by the insertion of Tn5 into a 7.3-kb EcoRI genomic fragment (21). It has not yet been determined if the protease-negative phenotype of these mutants was caused by the insertion of Tn5 into the structural protease gene or into the gene(s) required for the enzyme transport. Nothing is presently known about the mechanism by which P. fluorescens translocates the protease across the cell membranes. The objectives this study were to isolate and characterize the biochemical properties of the protease (designated AprX) produced by P. fluorescens CY091 and to clone and characterize the genes required for the production and secretion of AprX in strain CY091.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Pseudomonas strains were grown in minimal salt (MS) medium (17) containing K2HPO4 (0.7%), KH2PO4 (0.2%), MgSO4 · 7H2O (0.02%), and (NH4)2SO4 (0.1%). Glycerol was routinely used as the carbon source at a concentration of 0.4%. Unless otherwise indicated, CaCl2 was added to the medium at a final concentration of 1 mM. To examine the effect of divalent cations on enzyme production, strain CY091 was grown in MS medium containing one of five divalent salts (CaCl2, MgCl2, ZnCl2, SrCl2, and MnCl2). When required, the samples were prepared and the enzyme activities in the extracellular and cell-bound fractions were determined by previously described methods (18). Escherichia coli strains were grown in either Luria broth (Life Technologies Lab., Gaithersburg, Md.) or MS medium supplemented with 0.1% yeast extract and 0.1% Casamino Acids (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). To determine the optimal concentration of CaCl2 required for enzyme production, the bacterium was grown in MS medium containing various concentrations of CaCl2 (0.10 to 1.00 mM). When needed, antibiotics were added to the medium at the following concentrations (micrograms per milliliter): kanamycin, 50; rifampin, 100; and tetracycline, 25. When growth on solid medium was required, E. coli and P. fluorescens were grown in Luria agar (Life Technologies) and Pseudomonas agar F (Difco), respectively. The E. coli and P. fluorescens cultures were incubated at 37 and 28°C, respectively. To assay the spoilage-causing ability, skim milk purchased from a local store was inoculated with strain CY091, mutant J-1 (a nonproteolytic derivative of strain CY091 [21]), or strain B52 (originally isolated from milk [23]). The degrees of spoilage as indicated by gelation (14) were recorded after 10 days of incubation at 7°C.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant properties | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| P. fluorescens | ||

| CY091 | Wild type, causes soft rot in plants and gelation and off-flavor in milk | 18 |

| J-1 | Tn5-induced mutant of strain CY091, deficient in protease activity | 21 |

| B-52 | Wild type, causes spoilage of raw milk | 23 |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α, HB101 | Cloning and subcloning hosts | Life Technologies |

| Plasmids | ||

| pLAFR3 | IncP, tetracycline resistant, Cos+, Rlx+, cloning vector | B. Staskawicz |

| pRK2013 | IncP, kanamycin resistant, TraRK2+, used for triparental mating | 6 |

| pUC19 | Ampicillin resistant, subcloning vector | Life Technologies |

| pJIA, pJIC, pJID | Primary clones carrying P. fluorescens | This study |

| pJIAE | CY091 protease gene, pLAFR3 derivatives | |

| pJIE | 7.3-kb EcoRI fragment from pJIAE cloned into pLAFR3, tetracycline resistant | This study |

| pUC-JIE | 7.3-kb EcoRI fragment from pJIAE cloned into pUC19, HindIII site distal to the plac promoter, direct protease production in E. coli | This study |

| pJIH | 6.3-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment from pJIAE cloned into pLAFR3 | This study |

| pSAL21 | 2.1-kb SalI fragment from pJIH cloned into pUC19 | This study |

| pSAL12 | 1.2-kb SalI fragment from pJIH cloned into pUC19 | This study |

| pSAL29 | 2.9-kb SalI fragment from pJIH cloned into pUC19 | This study |

| pHE10 | 1.0-kb fragment from pJIE cloned into pUC19 | This study |

Enzyme purification and assays.

Strain CY091 was grown at 28°C for 72 h in MS medium containing 1 mM CaCl2. The cells were removed by centrifugation (10,400 × g for 20 min), and the supernatant was treated with ammonium sulfate. The precipitate formed at 50 to 95% saturation was collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer. Then the sample was dialyzed against the same buffer at 4°C for 18 h. The dialyzed sample was then applied to a DEAE-cellulose column (1.5 by 20 cm) which had been preequilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer. The stepwise elution was carried out with the same buffer containing 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 M NaCl. Fractions (5 ml) were collected, and each fraction was assayed for protease and PL activity and protein concentration. The protein contents were determined by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm or by the method of Bradford (4). PL activities were determined by the standard method (17), and protease activities were measured by a modification of a method previously described (12). Briefly, 0.5 ml of sample was added to 50 mg of Hide Powder Azure (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) in 1.5 ml of assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM CaCl2). The reaction mixtures were incubated at 28°C for 1 h with vigorous shaking. Then the liquid portion of the reaction mixture was decanted into microcentrifuge tubes and centrifuged at the maximum speed (13,000 × g for 5 min). The absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 595 nm. One unit of protease activity was defined as the amount of enzyme sample that caused an increase of 1 absorbance unit (U) at 28°C in 1 h.

Biochemical characterizations.

Enzyme samples were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis by the method of Laemmli (13). The Mini-Protean II apparatus and ready-made 12% polyacrylamide gels from Bio-Rad (Richmond, Calif.) were used. The thermostability and inhibition of the enzyme activity by ion chelators including EGTA and 1,10-phenanthroline were determined by the standard procedures as previously described (24, 31). Briefly, enzyme samples at initial activities of 10 to 25 U was placed in boiling water for 5 to 10 min and the activities remaining in the sample after the treatments were determined. Similarly, 5 to 10 U of protease samples were added to reaction mixtures containing 0.1 to 10.0 mM EGTA or 1,10-phenanthroline and the activities remaining in the reaction mixtures were determined to compare the differential effect of these two chelators on enzyme activities. The optimal temperature and pH for AprX activity were determined by standard procedures (1, 25). AprX samples (5 to 10 U) in the standard reaction mixture were incubated at temperatures ranging from 10 to 55°C. Similarly, equivalent amounts of ArpX were added to standard reaction mixtures with pHs from 5 to 10.

Cloning and characterization of the protease gene.

A genomic library of P. fluorescens CY091 was constructed in E. coli HB101 with pLAFR3 as a vector (21). This library was mobilized en masse into a nonproteolytic mutant, J-1 (21), with the aid of helper plasmid pRK2013 (6). Recombinant clones capable of restoring the proteolytic activity in mutant J-1 were isolated and used for further characterization. Standard procedures (28) were used for isolation of chromosome and plasmid DNAs, restriction analysis, subclonings, and preparation of competent cells for transformation. Conjugational transfers of genes between E. coli and P. fluorescens were conducted by previously described methods (6, 21).

DNA sequencing.

As described below, the aprX gene was located within a 7.3-kb genomic DNA fragment. Digestion of this fragment with SalI and HindIII resulted in the formation of four subfragments, each of which was isolated and cloned into pUC19 to form pSAL21, pSAL12, pSAL29, and pHE10. The nucleotide sequence of the insert was determined by the dideoxy chain termination method (29). Sequencing primers (18-mer) were synthesized and sequencing reactions were conducted at Labstrand Lab., Ltd. (Gaithersburg, Md.). DNA and protein sequence analyses were performed with the PC/GENE software programs (release 6.8) from IntelliGenetics, Inc. (Mountain View, Calif.).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The complete nucleotide sequence of the entire 7.3-kb fragment has been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnological Information (Bethesda, Md.), under accession no. AF004848.

RESULTS

Protease production.

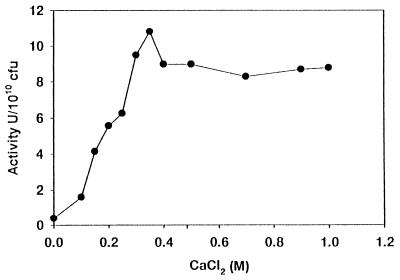

The proteolytic activity of P. fluorescens CY091, as indicated by the formation of clear zones (in the range of 3 to 7 mm in diameter) surrounding the bacterial growth, was detected in nutrient agar (Difco) supplemented with 1% gelatin or skim milk after a 3-day incubation at 28°C. High levels of protease activities ranging from 5.5 to 8.4 U per ml were also detected in MS medium containing glycerol as the sole carbon source. Production of the enzyme in the medium was not significantly enhanced by the addition of gelatin or skim milk. Since more than 89% of the protease activity was located in the culture supernatant, this enzyme, designated AprX, was an extracellular enzyme. Although production of AprX was not induced by the substrates, the presence of CaCl2 in MS medium was required. When the bacterium was grown in medium lacking CaCl2, very little or no activity was detected. However, when it was grown in medium containing 0.1 to 1.0 mM CaCl2, a nearly linear relationship between the amounts of the enzyme produced and the concentrations of CaCl2 (0.10 to 0.35 mM) included in the medium was observed (Fig. 1). The production of AprX is therefore dependent on the CaCl2 concentration, and the optimal concentration is 0.35 mM. To determine if the CaCl2 requirement could be replaced by other divalent cations, the bacterium was grown in MS medium containing one of four other divalent cations. High levels of enzyme activity, ranging from 5.6 to 8.3 U/1010 CFU, were detected in medium containing CaCl2 or SrCl2. Very low levels of activity (equivalent to the basal levels), ranging from 0.3 to 0.9 U/1010 CFU, were detected in medium containing ZnCl2, MgCl2, or MnCl2. Furthermore, more than 89% of the enzyme activity were detected in the culture supernatant when the cells were grown in medium containing CaCl2 or SrCl2, but more than 60% of the enzyme activity was retained within the cells when they were grown in medium containing ZnCl2, MgCl2, or MnCl2. The requirement for CaCl2 in AprX production and possibly in secretion is therefore highly specific. When inoculated into skim milk, the wild-type strain CY091 was able to cause the same degree of gelation as strain B52 (a strain originally isolated from milk). However, the nonproteolytic mutant (J-1) of strain CY091 did not cause gelation of raw milk. Furthermore, the purified AprX sample (described below) was capable of inducing gelation of skim milk. Thus, production of AprX by strain CY091 is required by this bacterium to cause spoilage in milk.

FIG. 1.

Effects of CaCl2 concentrations on protease production by P. fluorescens CY091 in MS medium (17).

Protease purification and characterization.

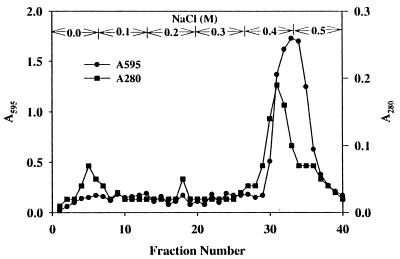

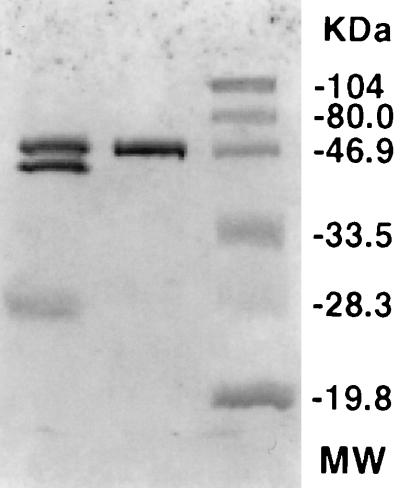

The culture supernatant of strain CY091 containing an initial protease activity of 5 to 8 U ml−1 was concentrated by ammonium sulfate precipitation. The precipitate formed at 50 to 95% saturation showed a 1.9- to 2.7-fold increase in specific activity compared to the unconcentrated supernatant. The precipitate was added to a DEAE-cellulose column and eluted by buffer containing 0.1 to 0.5 M NaCl. An example of the elution profile is illustrated in Fig. 2. Two absorption peaks at 280 nm were observed. Peak 1, showing PL activity, was detected in the buffer fractions containing 0.0 to 0.1 M NaCl, and peak 2, showing protease activity, was found in the buffer fractions containing 0.4 to 0.5 M NaCl. When analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, the sample from peak 2 exhibited a single band in the gel stained with Coomassie blue (Fig. 3). By overlay enzyme activity staining (17), the proteolytic activity of this protein band was confirmed. Based on the electrophoretic mobility, the molecular mass of this protein (AprX) was determined to be 50 kDa. The PL protein from peak 1 also exhibited a single band in the gel (data not shown), and its molecular mass (43 kDa) was close to that previously reported (18). The presence of these two major proteins, AprX and PL, in the ammonium sulfate-precipitated sample is shown in Fig. 3. The specific activity of the purified AprX sample was 63- to 75-fold greater than that of the unfractionated culture fluid. Optimal AprX activity was observed at 40 to 45°C and pH 7 to 8. When AprX samples were heated in boiling water for 10 to 30 min, approximately 20 to 30% of the protease activity remained, indicating that AprX is fairly heat stable.

FIG. 2.

Elution profile of the AprX protease of P. fluorescens CY091 from the DEAE-cellulose column. The column was eluted with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer followed by stepwise elution with buffer containing 0.1 to 0.5 M NaCl. The protease activity of each fraction, as indicated by the absorbance at 595 nm (A595), was determined under the conditions described in Materials and Methods. One unit of protease activity is defined as the amount of enzyme which causes an increase of 1 absorbance unit at 595 nm.

FIG. 3.

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of the purified AprX protease sample from P. fluorescens CY091. Molecular mass (MW) standards (in kilodaltons) are shown in the right-hand lane: phosphorylase b, 104; bovine serum albumin, 80; ovalbumin, 46.9; carbonic anhydrase, 33.5; soybean trypsin inhibitor, 28.3; lysozyme, 19.8. Purified AprX and the ammonium sulfate-precipitated sample (50 to 95% saturation) are shown in the middle and left lanes, respectively.

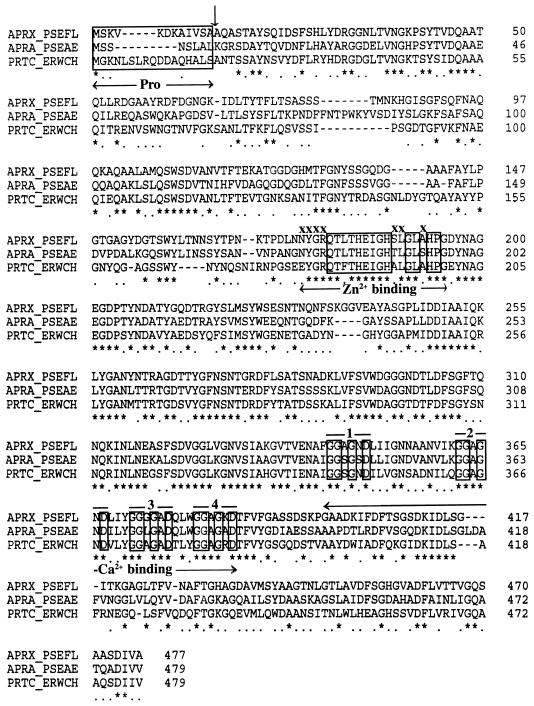

Both EGTA (a Ca2+ chelator) and 1,10-phenanthroline (a divalent-ion chelator) were examined for their effect on the activity of AprX. At least 10 mM EGTA was required to inhibit AprX activity more than 50% (Table 2), but 1 mM 1,10-phenanthroline was almost completely inhibitory (1.2% of the original activity remained). This result, in conjunction with the sequence analysis data (see Fig. 5), indicated that divalent cations, Ca2+ and Zn2+, are required for the activity and stability of the AprX enzyme.

TABLE 2.

Effects of ion chelators on activities of the AprX protease from P. fluorescens CY091a

| Inhibitor | Concn (mM) | %Activity remainingb |

|---|---|---|

| EGTA | 0.0 | 100 |

| 0.1 | 99 | |

| 1.0 | 70 | |

| 10.0 | 43 | |

| 1,10-Phenanthroline | 0.0 | 100 |

| 0.1 | 61 | |

| 1.0 | 1 | |

| 10.0 | <1 |

Enzyme samples were incubated with an inhibitor of a given concentration for 20 min at 28°C, and then the remaining activities in the samples were determined.

Each value represents the mean of three experiments. The activity in the reaction mixture containing no inhibitor was considered 100% activity.

FIG. 5.

Multiple-sequence alignment of zinc proteases from P. fluorescens CY091 (APRX_PSEFL) (this study), P. aeruginosa PA01 (APRA_PSEAE) (7), and E. chrysanthemi B374 (PRTC_ERWCH) (16).

Cloning of AprX and related transporter genes.

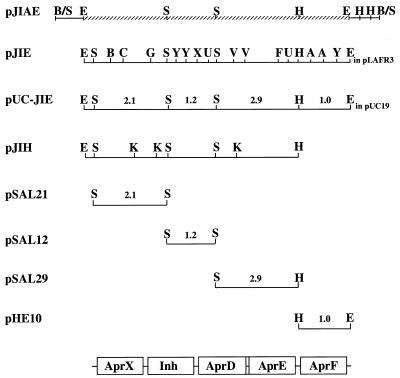

A genomic library of P. fluorescens CY091 was constructed in the broad-host-range vector pLAFR3 as previously described (21). Recombinant plasmids in approximately 2,500 E. coli cells were mobilized en masse into the nonproteolytic mutant J-1, and the resulting transconjugants were examined for restoration of protease production in this mutant. Four recombinant clones (pJIA, pJIC, pJID, and pJIAE) capable of restoring enzyme production in mutant J-1 were identified. When pJIA, pJIC, pJID, and pJIAE were each digested with EcoRI, a 7.3-kb fragment was detected in each clone. To examine if the 7.3-kb EcoRI fragment contained the aprX gene, this fragment was isolated from pJIAE and subcloned into pLAFR3 to form pJIE. After introduction into mutant J-1, pJIE was capable of directing the synthesis of wild-type levels of AprX. However, very little or no proteolytic activity was detected in E. coli cells carrying pJIE (or other primary clones). We suspected that the failure to detect enzyme activity in E. coli resulted from the poor expression of Pseudomonas native promoters (10) in E. coli. To prove this, the 7.3-kb EcoRI fragment was cloned into pUC19 at the EcoRI site immediately adjacent to the lac promoter. The resulting construct (pUC-JIE) in E. coli was indeed capable of directing the synthesis (presumably with the lac promoter) of extracellular AprX in the presence of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). To determine the minimal size of fragment required for extracellular AprX production, the 7.3-kb EcoRI fragment was digested with SalI or HindIII and the resulting subfragments (Fig. 4) were self-ligated or cloned individually into pUC19 to form a series of subclones, pJIH, pSAL21, pSAL12, pSAL29, and pHE10 (Table 1). Since none of these subclones were able to direct the production of extracellular AprX in E. coli, the entire 7.3-kb insert was assumed to be required for the production of extracellular AprX in E. coli.

FIG. 4.

Restriction map of P. fluorescens CY091 genomic DNA encoding the aprX protease gene and the aprD, aprE, and aprF genes required for enzyme secretion. The relative positions of these genes and a gene coding for a putative protease inhibitor (Inh) are indicated at the bottom. The length of the fragment in kilobase pairs is indicated above the line. Restriction enzymes: B, BamHI; S, SalI; K, KpnI; H, HindIII; E, EcoRI; C, ClaI; Y, StyI; G, BglII; U, StuI; X, XhoI; F, AflIII; A, AvaI; B/S, BamHI/Sau3A. The hatched area indicates the region where the nucleotide sequence has been determined. pJIE and pUC-JIE are derived from the insertion of the 7.3-kb EcoRI aprX+ fragment into pLAFR3 and pUC19, respectively. pJIH is a deletion subclone of pJIAE.

Analysis of DNA fragments required for production of extracellular AprX.

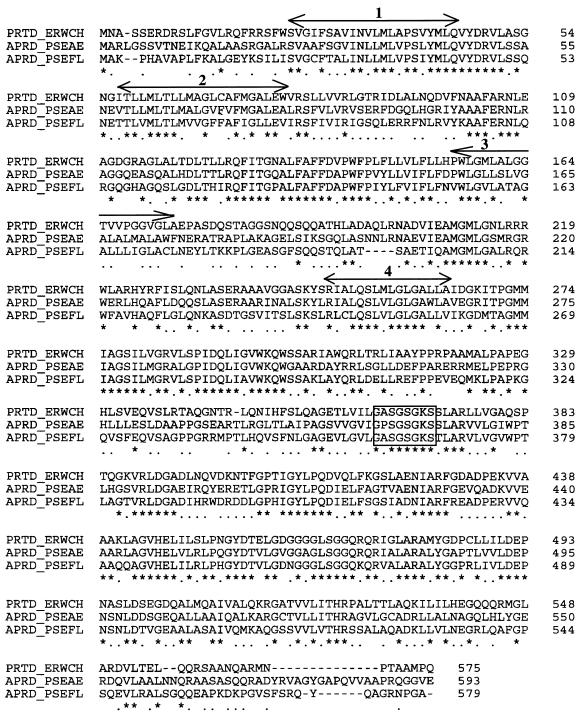

Analysis of complete nucleotide sequence of this aprX-containing 7.3-kb fragment revealed the presence of five open reading frames (ORFs), which were found sequentially on the same DNA strand. The first ORF (nucleotides [nt] 843 to 2111) was predicted to encode a protein consisting of 473 amino acids (aa). This protein showed 50 to 60% identity in amino acid sequences to the AprA protease of P. aeruginosa (7) and the PrtC, PrtB, and PrtA proteases of Erwinia chrysanthemi (9, 16). ORF1 was thus predicted to encode the structural AprX sequence of P. fluorescens CY091. The Mr of AprX, as predicted from the amino acid sequence, was in good agreement with that determined by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3). Multiple-sequence alignment of the AprX, AprA, and PrtC proteins (Fig. 5) revealed two domains that were probably associated with the binding of Zn2+ and Ca2+. The Zn2+-binding domain was characterized by a well-defined signature, xxxQTLTHEIGHxxGLxHPx, whereas the Ca2+-binding domain was characterized by the presence of four glycine-rich repeats GGxGxD. Based on the sequence analysis data (Fig. 5), AprX was predicted to be synthesized as a proenzyme containing a pro-sequence of 12 aa. Immediately following ORF1, a long hairpin structure characteristic of a rho-independent transcriptional termination sequence was identified at nt 2282 to 2305.

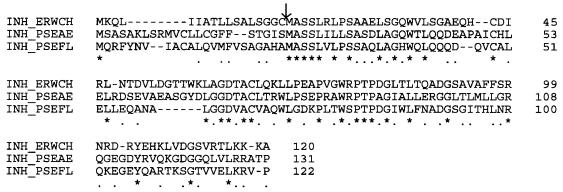

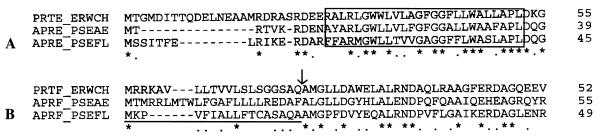

ORF2 spanned a region of 366 bp (nt 2325 to 2690) and encoded a protein consisting of 122 aa and with a molecular mass of 13.2 kDa. Sequence similarity search showed that this protein exhibited 37 to 45% identity in amino acid sequence to the protease inhibitors (Inh) previously found in E. chrysanthemi (15) and P. aeruginosa (11) (Fig. 6). The P. fluorescens Inh contained a signal peptide composed of 23 aa. Immediately following the inh gene, three additional genes designated aprD (nt 2796 to 4532), aprE (nt 4532 to 5842), and aprF (nt 5848 to 7260) were identified. The hydrophobicity analysis showed that AprD of P. fluorescens CY091 contained four hydrophobic regions and one consensus site (GxxGxGKS) for the ATP binding (Fig. 7). P. fluorescens AprD exhibited 54 to 56% identity in amino acid sequence to the AprD and PrtD proteins of P. aeruginosa and E. chrysanthemi. The hydropathy profile of AprE also revealed the presence of a long stretch of hydrophobic region (Fig. 8A) at the amino terminus. Sequence similarity analysis showed that AprE exhibited 44 to 50% identity in amino acid sequence to the AprE and PrtE proteins of P. aeruginosa and E. chrysanthemi. P. fluorescens AprF, consisting of 471 aa, was closely related to the AprF and PrtF proteins of P. aeruginosa and E. chrysanthemi. It exhibited 30 to 44% identity in amino acid sequence to its counterparts in P. aeruginosa and E. chrysanthemi. Unlike AprD and AprE, AprF was largely hydrophilic, with the exception of the sequence located at the amino terminus, where a putative signal peptide (of 17 aa) was identified (Fig. 8B). Based on the their sequence similarity to the protease secretion apparatus previously demonstrated in P. aeruginosa and E. chrysanthemi, AprDEF was predicted to constitute a secretion apparatus for the transport of AprX in P. fluorescens CY091.

FIG. 6.

Amino acid sequence alignment of the protease inhibitor (INH) from P. fluorescens CY091 (INH_PSEFL), P. aeruginosa (INH_PSEAE), and E. chrysanthemi (INH_ERWCH). The arrow indicates the predicted cleavage site of the signal peptidase.

FIG. 7.

Multiple-sequence alignment of the AprD proteins from P. fluorescens CY091 (APRD_PSEFL) and P. aeruginosa (APRD_PSEAE) and the PrtD protein from E. chrysanthemi (PRTD_ERWCH). The numbered lines above the sequence indicate the hydrophobic regions. The boxed area indicates the ATP-binding site.

FIG. 8.

Alignment and comparison of the amino-terminal sequences of the AprE (A) and AprF (B) proteins from P. fluorescens CY091 (APRE/F_PSEFL) and P. aeruginosa (APRE/F_PSEAE) and the PrtE/F proteins from E. chrysanthemi (PRTE/F_ERWCH). The boxed area in panel A represents the hydrophobic region, and the underline in panel B represents the putative signal peptide sequence. The arrow indicates the possible peptidase cleavage site.

DISCUSSION

Data presented here show that P. fluorescens CY091 produces an extracellular protease, AprX, with an estimated molecular mass of approximately 50 kDa. Although this enzyme does not play an essential role in causing soft rot of fresh fruits and vegetables (21), it is required to cause spoilage in milk and possibly in dairy products. In this study, we demonstrated that a protease-negative Tn5 mutants of strain CY091 was unable to cause gelation of raw milks. This result supports the previous suggestion that the protease is the primary factor responsible for the spoilage caused by P. fluorescens. The AprX of strain CY091 is similar in several biochemical properties, including thermostability and divalent-ion requirement, to proteases produced by other strains of P. fluorescens (1, 8, 24, 31). They are heat stable and require Ca2+ and Zn2+ for activity and/or stability. Sequence analysis of the predicted AprX protein reveals the presence of two conserved domains specific for Ca2+ and Zn2+ binding (Fig. 5). This result, in conjunction with the data obtained from biochemical studies, indicates that AprX is a metalloprotease with zinc as an integral part of the enzyme.

While investigating the protease produced by a psychrophilic strain of P. fluorescens, Margesin and Schinner (22) found that the protease produced by this strain formed multiple bands in isoelectric focusing (IEF) gels. They suggest that the multiple bands observed in the gel represent different processing forms or breakdown products of a single protease (22). In this study, we also found that the purified AprX of strain CY091 appeared as a single band in the SDS-polyacrylamide gel (Fig. 3) but formed two bands in the IEF gel (data not shown). Genetic data presented here seem to rule out the possibility that the two bands we observed in the IEF gel represent two isozymes. In this study, we found that the AprX produced by E. coli cells carrying pUC-JIE formed a single band in the SDS-polyacrylamide gel but also formed double bands in the IEF gel (data not shown). Since pUC-JIE contains only one protease structural gene, it is unlikely that recombinant E. coli cells would produce two isoforms of AprX. Like PrtC and AprA, AprX is predicted to be synthesized as a proenzyme with a pro-sequence consisting of 12 aa (Fig. 5). The pro-sequence at the N terminus of the pro-AprX protein is assumed to be removed by the autoproteolytic action of AprX (33). Based on these results, we conclude that P. fluorescens CY091 also produces a single protease, which may exist in different processed forms and display multiple activity bands in the IEF gels, as originally suggested by Margesin and Schinner (22).

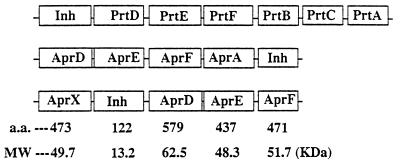

The extracellular location of AprX was indicated by the observation that more than 89% of the total protease activity produced by strain CY091 was detected in the culture supernatant. Since AprX does not contain a putative signal peptide, the translocation of this enzyme across the cytoplasmic membrane is therefore not mediated by the Sec-dependent secretion pathway. The data presented here suggests that the AprX transport is possibly mediated by an independent secretion apparatus consisting of two membrane-associated (AprD and AprE) and one periplasm-associated (AprF) proteins. The predicted amino acid residues and molecular masses of AprD, AprE, and AprF are summarized in Fig. 9. Based on their sequence homologies, the function of the AprDEF apparatus of P. fluorescens is analogous to the protease or hemolysin secretion apparatus previously demonstrated in P. aeruginosa (11), E. chrysanthemi (5), and E. coli (16, 33). Comparison of the organization of the gene operons associated with the production and secretion of proteases in P. fluorescens, P. aeruginosa, and E. chrysanthemi (Fig. 9) shows that they are somewhat different among these bacteria. In E. chrysanthemi and P. aeruginosa, the protease structural genes are located downstream of the transporter genes (aprDEF or prtDEF). However, in P. fluorescens, the aprX gene was located upstream of the inh and aprDEF transporter genes. The evolutionary significance of the difference in the organization of the protease gene operon in these organisms is unknown.

FIG. 9.

Comparison of the organization of the gene cluster involved in the synthesis and secretion of the AprX protease in P. fluorescens, the AprA protease in P. aeruginosa, and the PrtB, PrtC, and PrtA proteases in E. chrysanthemi. The predicted amino acid residues and molecular mass (MW) of each protein component in the P. fluorescens AprX gene cluster are indicated at the bottom of the figure.

Data presented here also shows that the AprX protein of strain CY091 contains a conserved domain specific for Ca2+ binding (Fig. 5). Previously, it has been shown that Ca2+ is necessary for maintaining the stability and integrity of the active site (2, 23). Barach et al. (2) reported that the presence of Ca2+ in the solution can enhance the heat resistance of the proteases from P. fluorescens MC60. In this study, we also found that Ca2+ was required not only for the optimal activity of the AprX protease but also for the production of maximal levels of the enzyme by strain CY091. The requirement of Ca2+ for AprX production by strain CY091 is specific and concentration dependent. It is unclear if Ca2+ is directly involved in the regulation of the AprX production or is simply required for stabilizing the enzyme after synthesis. We previously reported that production of another extracellular enzyme (PL) by strain CY091 also required Ca2+ (20). Since the production of both PL and AprX in P. fluorescens CY091 is mediated by a two-component (lemA and gacA) global regulatory pathway (19, 21), it is unclear if Ca2+ acts as an external or internal factor signaling the expression of the lemA and gacA genes and in turn the synthesis of PL and AprX.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the critical review and suggestions of D. Solaiman, P. Fratamico, and K. Hicks, USDA, Wyndmoor, Pa., in the final preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alichanidis E, Andrews A T. Some properties of the extracellular protease produced by the psychrotrophic bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens strain AR-11. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977;485:424–433. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(77)90178-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barach J T, Adams D M, Speck S L. Stabilization of a psychrotrophic Pseudomonas protease by calcium against thermal inactivation in milk at ultrahigh temperature. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1976;31:875–879. doi: 10.1128/aem.31.6.875-879.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bond J S, Butler P E. Intracellular proteases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:333–364. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.002001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of proteins utilizing protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delepelaire P, Wandersman C. Protease secretion by Erwinia chrysanthemi. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:9083–9089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ditta G, Stanfield S, Corbin D, Helinski D R. Broad host range DNA cloning system for Gram-negative bacteria: construction of a gene bank of Rhizobium meliloti. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:7347–7351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doug F, Lazdunski A, Cami B, Murgier M. Sequence of a cluster of genes controlling synthesis and secretion of alkaline protease in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: relationships to other secretory pathways. Gene. 1992;121:47–54. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90160-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fairbairn D J, Law B A. Proteinases of psychrotrophic bacteria: their production, properties, effects and control. J Dairy Res. 1986;53:139–177. doi: 10.1017/s0022029900024742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghigo J-M, Wandersman C. Cloning, nucleotide sequence and characterization of the gene encoding the Erwinia chrysanthemi B374 PrtA metalloprotease: a third metalloprotease secreted via a C-terminal secretion signal. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;236:135–144. doi: 10.1007/BF00279652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guzzo J, Murgier M, Filloux A, Lazdunski A. Cloning of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa alkaline protease gene and secretion of the protease into the medium by Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:942–948. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.942-948.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guzzo J, Pages J-M, Duong F, Lazdunski A, Murgier M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa alkaline protease: evidence for secretion genes and study of secretion mechanism. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5290–5297. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.17.5290-5297.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howe T R, Iglewski B. Isolation and characterization of alkaline protease-deficient mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in vitro and in a mouse eye. Infect Immun. 1984;43:1058–1063. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.3.1058-1063.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Law B A, Andrew A T, Sharpe M E. Gelation of ultra-high-temperature-sterilized milk by proteases from a strain of Pseudomonas fluorescens isolated from raw milk. J Dairy Res. 1977;44:145–148. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Letoffe S, Delepelaire P, Wandersman C. Characterization of a protein inhibitor of extracellular proteases produced by Erwinia chrysanthemi. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:79–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Letoffe S, Delepelaire P, Wandersman C. Protease secretion by Erwinia chrysanthemi: the specific secretion functions are analogous to those of Escherichia coli α-haemolysin. EMBO J. 1990;9:1375–1382. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08252.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liao C-H. Analysis of pectate lyases produced by soft-rot bacteria associated with spoilage of vegetables. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:1677–1683. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.7.1677-1683.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liao C-H. Cloning of pectate lyase gene pel from Pseudomonas fluorescens and detection of sequences homologous to pel in Pseudomonas viridiflava and Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4386–4393. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4386-4393.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liao C-H, McCallus D E, Fett W F. Molecular characterization of two gene loci required for production of the key pathogenicity factor pectate lyase in Pseudomonas viridiflava. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1994;7:391–400. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-7-0391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liao C-H, McCallus D E, Wells J M. Calcium-dependent pectate lyase production in the soft-rotting bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens. Phytopathology. 1993;83:813–818. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liao C-H, McCallus D E, Fett W F, Kang Y G. Identification of gene loci controlling pectate lyase production and soft rot pathogenicity in Pseudomonas marginalis. Can J Microbiol. 1997;43:425–431. doi: 10.1139/m97-060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Margesin R, Schinner F. Production and properties of an extracellular metalloprotease from a psychrophilic Pseudomonas fluorescens. J Biotechnol. 1992;24:207–210. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKellar R C, Cholette H. Possible role of calcium in the formation of active extracellular proteinase by Pseudomonas fluorescens. J Appl Bacteriol. 1986;60:37–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1986.tb01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell S L, Marshall R T. Properties of heat-stable proteases of Pseudomonas fluorescens: characterization and hydrolysis of milk proteins. J Dairy Sci. 1989;72:864–874. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morihara K. Production of elastase and proteinase by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1964;88:745–757. doi: 10.1128/jb.88.3.745-757.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palleroni N J. Pseudomonadaceae (Wilson, Broadhurst, Buchanan, Krumwide, Rogers and Smith 1917) In: Krieg N R, Holt J G, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 1. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1984. pp. 143–213. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel T R, Bartlett F M, Hamid J. Extracellular heat-resistant proteases of psychrotrophic pseudomonads. J Food Prot. 1983;46:90–94. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-46.2.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambrook J, Fritsch E G, Maniatis T A. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stanier R Y, Palleroni N J, Doudoroff M. The aerobic pseudomonads: a taxonomic study. J Gen Microbiol. 1966;43:159–271. doi: 10.1099/00221287-43-2-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stepaniak L, Fox P F, Daly C. Isolation and general characterization of a heat-stable proteinase from Pseudomonas fluorescens AFT 36. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982;717:376–383. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(82)90192-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tseng T-M, Mount M S. Toxicity of endopolygalacturonate trans-eliminase, phosphatidase and protease to potato and cucumber tissue. Phytopathology. 1973;64:229–236. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wandersman C. Secretion, processing and activation of bacterial extracellular proteases. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1825–1831. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]