Abstract

Virginia creeper (or five-leaved ivy; Parthenocissus quinquefolia) is one of the most popular and widely grown climbers worldwide. In September 2021, Virginia creeper leaves with typical rust symptom were found in an arboretum in Korea, with severe damage. Globally, there is no record of a rust disease on Virginia creeper. Using morphological investigation and molecular phylogenetic inferences, the rust agent was identified as Neophysopella vitis, which is a rust pathogen of other Parthenocissus spp. including Boston ivy (P. tricuspidata). Given that the two ivy plants, Virginia creeper and Boston ivy, have common habitats, especially on buildings and walls, throughout Korea, and that N. vitis is a ubiquitous rust species affecting Boston ivy in Korea, it is speculated that the host range of N. vitis may recently have expanded from Boston ivy to Virginia creeper. The present study reports a globally new rust disease on Virginia creeper, which could be a major threat to the ornamental creeper.

Keywords: Boston Ivy, host-jump, obligate biotroph, Pucciniales; Vitaceae

1. Introduction

Virginia creeper or five-leaved ivy (Parthenocissus quinquefolia (L.) Planch., Vitaceae) is a perennial climber plant native to eastern and central North America. This plant is used as an ornamental plant because of its ability to rapidly cover buildings and walls and its attractive red fall foliage. However, it is considered a harmful weed in the production of fruit tree orchards and Fraser fir plantations [1]. Recently, it has been widely cultivated as a house gardening, wall greening, or traffic noise barrier plant in Korea [2,3]. Another widespread climber, Boston ivy (P. tricuspidata (Siebold & Zucc.) Planch.), is native to Northeast Asia and is globally popular for buildings, fences, and walls because of its rapid climbing and high cold resistance [4,5].

Rust disease is one of the most destructive diseases of Boston ivy in China, Japan, Taiwan, and Korea [6–9]. Rust fungi (Pucciniales) are the largest obligate plant pathogen group in Basidiomycota, with many members damaging economically important crops and ornamental plants [10]. Foliar rust is a common disease of the family Vitaceae, which includes economically important grapevines (Vitis spp.) as well as ivy [11]. Vitaceae rusts have previously been classified under the genus Phakopsora, but have been recently transferred to the new genus Neophysopella [12]. In the past, the rust diseases on Vitaceae plants were attributed to a misconceived generalist, Neophysopella ampelopsidis (Dietel & Syd.) Jing X. Ji & Kakish. (originally as Phakopsora ampelopsidis Dietel & P. Syd.) [13], but [14] split the species complex into three host-specific species, namely N. ampelopsidis, N. vitis (P. Syd.) Jing X. Ji & Kakish., and N. euvitis (Y. Ono) Jing X. Ji & Kakish., each of which forms uredinial and telial stages on Ampelopsis, Parthenocissus, and Vitis, respectively. Recently, two new species, namely N. doipuiensis Okane & Y. Ono and N. tropicalis Y. Ono, Chatasiri, Pota & Okane, were reported on Ampelocissus araneosa and Vitis spp., respectively [15].

In September 2021, severe spontaneous infections with a rust fungus were found on Virginia creeper leaves at an arboretum and a roadside in Jeonju, Korea, with a high disease incidence of more than 70%. Yellow to orange rust pustules were formed on the lower leaf surface. Infected leaves gradually became brown and were early defoliated. Because no rust disease has been reported on Virginia creeper worldwide and because the causal fungus is a potential threat to the ornamental creeper as it reduces its esthetic value, we undertook the study with the aim of determining its phylogenetic position in and taxonomic relationships to vitaceous rust fungi and discussing a possible origin of this emergent disease.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Specimen collection

Three samples of the Virginia creeper rust have been deposited in the Korea University Herbarium (Table 1). To identify the causal pathogen, both morphological and molecular phylogenetic approaches were used. For comparison, five rust specimens of Boston ivy (P. tricuspidata) and three of Meliosma myriantha Siebold & Zucc. (an alternate host plant of N. vitis) were included.

Table 1.

Herbarium specimens of Neophysopella vitis used in the present study.

| Herbarium no. | Host | Date | Location | GenBank accession no. |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | LSU | ||||

| KSNUH1523 | Parthenocissus quinquefolia | 18 Sept 2021 | Jeonju arboretum, Jeonju, Korea | OM423803 | OM420272 |

| KSNUH1719 | Parthenocissus quinquefolia | 26 Oct 2021 | Jeonju arboretum, Jeonju, Korea | OM423804 | OM420263 |

| KSNUH1724 | Parthenocissus quinquefolia | 22 Oct 2021 | Deokjin-gu, Jeonju, Korea | OM423805 | OM420266 |

| KUS-F29644 | Parthenocissus tricuspidata | 3 Nov 2016 | Daeho-dong, Naju, Korea | OM423806 | OM420269 |

| KUS-F30853 | Parthenocissus tricuspidata | 31 Oct 2018 | Mt. Sarabong, Jeju, Korea | OM423807 | OM420270 |

| KSNUH1600 | Parthenocissus tricuspidata | 6 Oct 2021 | Jeonju arboretum, Jeonju, Korea | OM423808 | OM420262 |

| KSNUH1720 | Parthenocissus tricuspidata | 26 Oct 2021 | Jeonju arboretum, Jeonju, Korea | OM423809 | OM420264 |

| KSNUH1722 | Parthenocissus tricuspidata | 22 Oct 2021 | Deokjin-gu, Jeonju, Korea | OM423810 | OM420265 |

| KUS-F24957 | Meliosma myriantha | 14 Jun 2010 | Jeolmul Natural Recreation Forest, Jeju, Korea | OM423802 | OM420267 |

| KUS-F28615 | Meliosma myriantha | 21 May 2015 | Cheonjeyeon Forest, Seogwipo, Korea | OM423811 | OM420268 |

| KSNUH0433 | Meliosma myriantha | 15 May 2019 | Mt. Jeam, Boseong, Korea | OM423812 | OM420271 |

2.2. Morphological analysis

All morphological characteristics were examined using rust-infected leaves under a dissecting microscope (M205C; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany), a DIC light microscope (Axio Imager 2; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and a scanning electron microscope (S-4800 + EDS; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

2.3. Molecular phylogenetic analysis

To confirm the identity of the fungus, genomic DNA was extracted from urediniospores on infected leaves using MagListo 5 M plant Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Bioneer, Daejeon, Korea). The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and large subunit (LSU) rDNA regions were amplified using primer pairs, ITS5u/ITS4rust [16,17] and LRust1R/LRust3 [17], respectively. The PCR products were purified using AccuPrep® PCR/Gel Purification Kit (Bioneer) and sequenced by a DNA sequencing service (Macrogen, Seoul, Korea) with the primers used for amplification. The resulting sequences were edited using the DNASTAR software package (Lasergen, Madison, WI, USA) and deposited in GenBank (Table 1). Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the minimum-evolution (ME) method [18], with the default settings of the program, except for the replacement with the Tamura-Nei model. The robustness of individual branches was estimated by bootstrapping 1,000 replicates.

3. Results

3.1. Morphological characterization

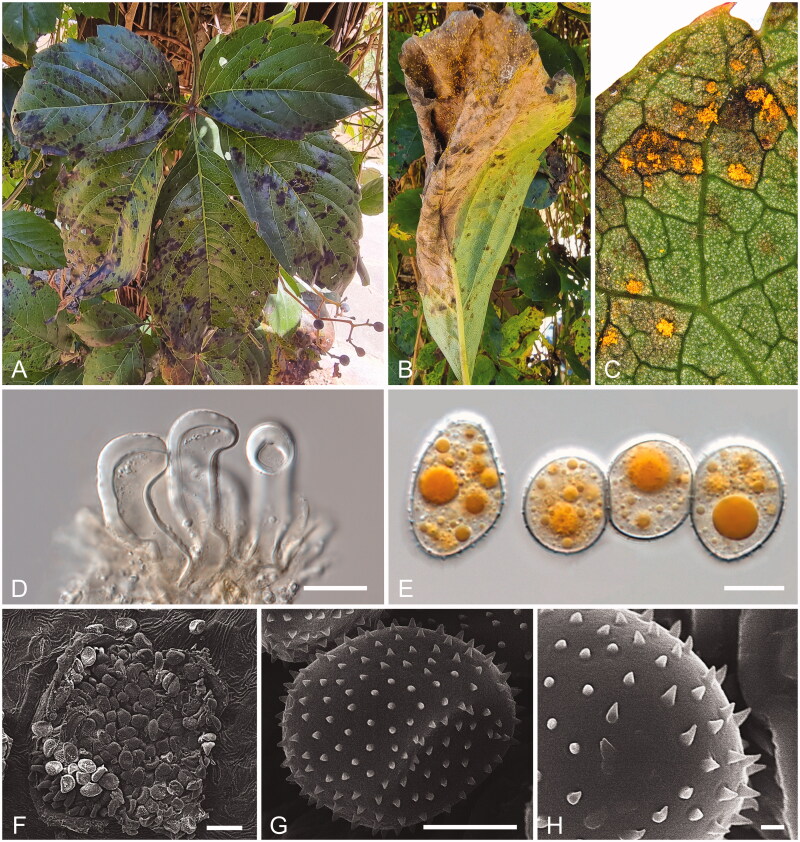

Symptoms appeared as chlorotic spots on the upper surface of infected leaves and yellow or orange rust pustules were formed on the corresponding lower surfaces (Figure 1(A,B)). Uredinia were hypophyllous, yellowish or orange-yellow, mostly scattered, rounded, surrounded by paraphyses, and 100–250 μm in diameter (Figure 1(C,F)). Uredial paraphyses were colorless, strongly incurved, and (26–)54–89(–91) μm (av. 72.0 μm) (Figure 1(D)). Their dorsal wall was obviously thicker as (3–)5–8(–9) μm (av. 7.2 μm) than the ventral wall. Urediniospores were subglobose to ovoid, (15–)17–22(–26) × (10–)13–15(–16) μm (av. 20.0 × 14.7 μm) (n = 50) and contained yellow or orange-yellow oil droplets (Figure 1(E)). The wall of the urediniospore was colorless or pale yellow, echinulate, and 1.0–2.0 μm thick (Figure 1(G,H)). Telial structure was not observed.

Figure 1.

Neophysopella vitis on Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia). (A) Infected leaves showing discoloration. (B) Rust pustules formed on the lower surface of an infected leaf. (C) Uredinia were hypophyllous and scattered. (D) Uredinial paraphyses under a differential interference contrast (DIC) microscope. (E) Urediniospores under a DIC microscope. (F) Uredinium under a scanning electron microscope (SEM). (G) Urediniospore under a SEM. (H) Echinulate wall of urediniospore under a SEM. Scale bars: D = 40 μm; E = 10 μm; F = 30 μm; G = 6 μm; H = 1 μm.

The size of the urediniospores in the Korean specimens was similar to those of other Neophysopella species parasitic to Vitaceae [14,15]. However, the dorsal wall of paraphyses was consistently thick as those of N. vitis (3.5–8.6 μm) but different from those of other species: N. ampelopsidis (2.5–5.5 μm), N. montana (0.9–4.9 μm), N. meliosmae-myrianthae (0.6–5.5 μm), N. orientalis (2.1–8.7 μm), N. meliosmae (3.0–11.9 μm), and N. hornotina (4–14 μm) [14,15,19–21]. Therefore, this pathogen was morphologically identified as N. vitis.

3.2. Molecular phylogeny

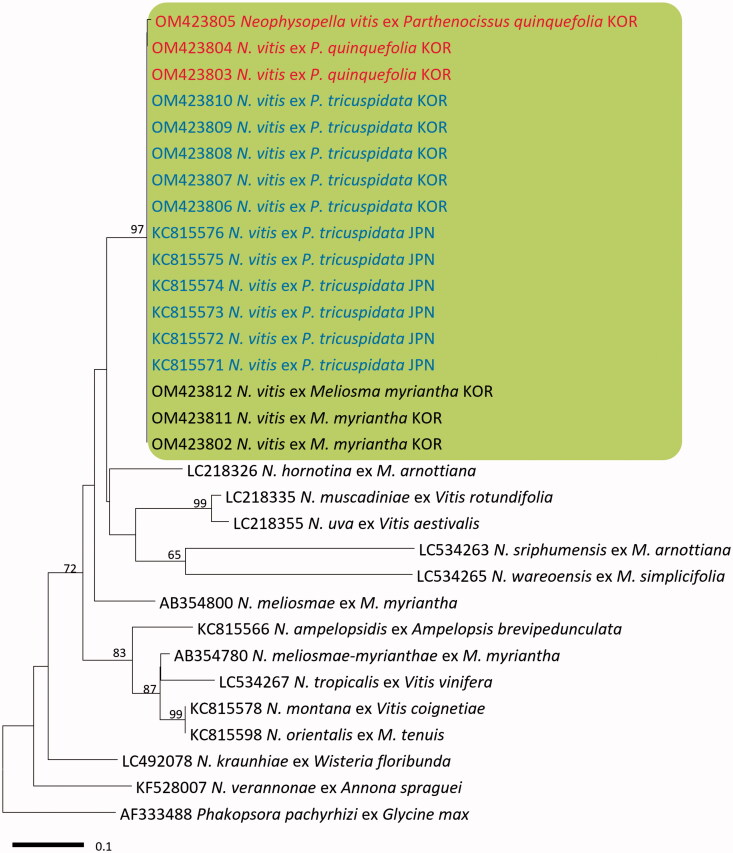

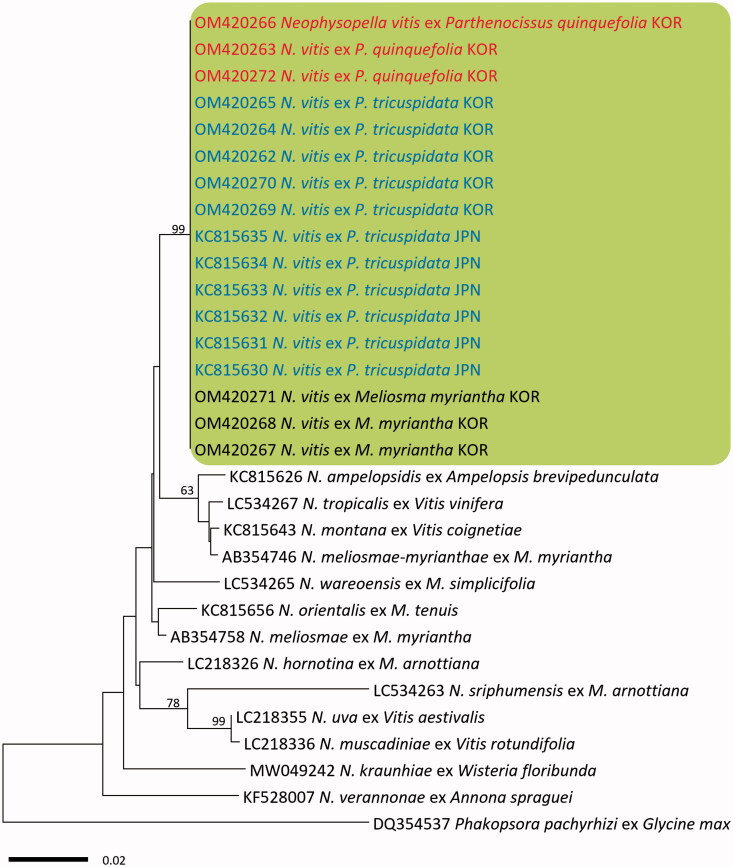

In BLASTn search, both ITS and LSU rDNA sequences of the three Virginia creeper specimens were identical to N. vitis on P. tricuspidata in Japan (KC815571–KC815576 for ITS and KC815630–KC815635 for LSU). In both minimum-evolution phylogenetic trees of ITS (Figure 2) and LSU (Figure 3) sequences, all Korean specimens originating from Virginia creeper, Boston ivy, and M. myriantha formed a well-supported clade with N. vitis sequences on P. tricuspidata in Japan with high bootstrap values of 97% (ITS) and 93% (LSU) but were distant from other Neophysopella species parasitic on other genera of Vitaceae.

Figure 2.

Minimum evolution tree of Neophysopella species inferred based on the ITS rDNA sequences. The numbers above the branches represent bootstrap values over 60%. The colored box represents Neophysopella vitis. The Korean specimens of Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) are shown in red.

Figure 3.

Minimum evolution tree of Neophysopella species inferred based on the LSU rDNA sequences. The numbers above the branches represent bootstrap values over 60%. The colored box represents Neophysopella vitis. The Korean specimens of Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) are shown in red.

4. Discussion

Two Neophysopella species have been recorded on Parthenocissus species. Neophysopella vitis is an East Asian species, parasitic on P. tricuspidata, P. heterophylla (Broome) Merr., and P. semicordata (Wall.) Planch. [14,22], but P. cronartiiformis is a South Asian species, parasitic on P. semicordata [23,24]. In the present morphological and molecular analyses, the causal pathogen on Virginia creeper rust in Korea is now confirmed as N. vitis, a common pathogen on Boston ivy in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan [9], but distinct from P. cronartiiformis. Neophysopella vitis is known as a heteroecious species that forms uredinial-telial stages on Parthenocissus and spermogonial-aecial stages on Meliosma [15]. Our phylogenetic study shows no sequence divergence between the rust samples from Parthenocissus spp. and those from M. myriantha, supporting our assumption on the life cycle connection between P. quinquefolia and M. myriantha. It is in good agreement with a previous study that the spermogonial-aecial stage of N. vitis is formed on Meliosma myriantha in Japan [20]. In Korea, M. myriantha, along with M. oldhamii, has been recorded as the aecial host plant of N. meliosmae-myrianthae (= Phakopsora meliosmae-myrianthae) [7]. To our knowledge, this is the first record of the rust affecting Virginia creeper worldwide. Given the increasing global distribution and demand of this plant, this disease poses a serious risk to the cultivation and management of Virginia creeper.

Our study shows that repeated exposure of the urediniospores of N. vitis from P. tricuspidata (a common susceptible host) onto P. quinquefolia (non-host) facilitates the establishment of genetically diverged N. vitis populations through selection to gain parasitic ability on a previously non-host plant, P. quinquefolia. Since its introduction to Korea, Virginia creeper has been propagated commercially for decades. Thus, it often grows together with Boston ivy or even on walls and buildings. It should be noted that since the rust on Boston ivy is widespread and severe throughout Korea, Virginia creeper might have been inevitably and repeatedly exposed to N. vitis urediniospores released from infected Boston ivy under various conditions. These favorable conditions may have provided numerous opportunities for the host-expansion of N. vitis to Virginia creeper. This and similar processes have certainly been occurring in an evolutionary time scale of the fungus-plant interactions, through which not only host expansion, but also speciation events, have happened in the forms of host-tracking, host-shift, or host-jump [25–29]. Our study reveals that a new disease emerges almost instantaneously through the host expansion of a rust fungus to a previously non-host plant. Given that we were unable to detect Virginia creeper rust in our long-term and nationwide monitoring, it is speculated that host expansion occurred only recently. The host expansion does not yet involve a speciation event, but factors and mechanisms underlying this process are expected to be the same or similar [26–30].

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Academy of Agricultural Science grant [PJ0149560112021] from the Rural Development Administration, Korea.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- 1.Richardson RJ, Marshall MW, Uhlig RE, et al. Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) and wild grape (Vitis spp.) control in Fraser fir. Weed Technol. 2009;23(1):184–187. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee S, Sim W.. A study on the wall plants for the improvement of the urban environment: with special reference to Seoul. J Korean Instit Landscape Architect. 1994;22:1121–1134. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jung T-G, So J-H, Lee E-J, et al. The experiment of vine for covering the traffic noise barrier. J Korean Soc Environmen Restoration Technol. 1999;2:72–82. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ckitchfield WB. Shoot growth and leaf dimorphism in boston ivy (Parthenocissus tricuspidata). Am J Botany. 1970;57(5):535–542. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin HD, Choi YJ, Hong SH, et al. Grovesinia moricola occurring on Parthenocissus tricuspidata. Korean J Mycol. 2019;47:271–274. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hiratsuka N, Chen Z.. A list of Uredinales collected from Taiwan. Trans Mycol Soc Japan. 1991;32:3–22. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho WD, Shin H-D.. List of plant diseases in Korea. 4th ed. Suwon: Korean Society of Plant Pathology; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatasiri S, Ono Y.. Phylogeny and taxonomy of the Asian grapevine leaf rust fungus, Phakopsora euvitis, and its allies (Uredinales). Mycoscience. 2008;49(1):66–74. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fungal Databases , Systematic Mycology and Microbiology Laboratory, ARS, USDA. Available at: http://nt.ars-grin.gov/fungaldatabases/. Accessed on Jan 10, 2022. [database on the Internet].

- 10.Kolmer JA, Ordonez ME, Groth JV.. The rust fungi. Encyclopedia of life sciences (ELS). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerrath J, Posluszny U, Melville L.. Taming the wild grape. Botany and horticulture in the Vitaceae. Heidelberg: Springer; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ji JX, Li Z, Li Y, et al. Life cycle of Nothoravenelia japonica and its phylogenetic position in Pucciniales, with special reference to the genus Phakopsora. Mycol Prog. 2019;18(6):855–864. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pearson RC, Goheen AC.. Compendium of grape diseases. St. Paul, Minn.: APS Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ono Y. Taxonomy of the Phakopsora ampelopsidis species complex on vitaceous hosts in Asia including a new species, P. euvitis. Mycologia. 2000;92(1):154–173. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ono Y, Okane I, Chatasiri S, et al. Taxonomy of southeast Asian-Australasian grapevine leaf rust fungus and its close relatives. Mycol Prog. 2020;19(9):905–919. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfunder M, Schürch S, Roy BA.. Sequence variation and geographic distribution of pseudoflower-forming rust fungi (Uromyces pisi s. lat.) on Euphorbia cyparissias. Mycol Res. 2001;105(1):57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beenken L, Zoller S, Berndt R.. Rust fungi on Annonaceae II: the genus Dasyspora berk. & MA curtis. Mycologia. 2012;104(3):659–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K.. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):1870–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pota S, Chatasiri S, Ono Y, et al. Taxonomy of two host specialized Phakopsora populations on Meliosma in Japan. Mycoscience. 2013;54(1):19–28. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pota S, Chatasiri S, Unartngam J, et al. Taxonomic identity of a Phakopsora fungus causing the grapevine leaf rust disease in Southeast Asia and Australasia. Mycoscience. 2015;56(2):198–204. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ono Y. Phakopsora hornotina, an additional autoecious rust species on Meliosma in the Philippines and the Ryukyu islands, Japan. Mycoscience. 2016;57(1):71–78. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuprevich V, Tranzschel V.. Cryptogamic plants of the USSR. Vol. IV, Rust fungi. No. 1, family Melampsoraceae. Moscow: The Academy of Science U.S.S.R.; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ono Y, Adhikari M, Rajbhandari K.. Uredinales of Nepal. Reports of the Tottori Mycol Instit. 1990; 28:57–75. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh A, Palni U.. Diversity and distribution of rust fungi in Central Himalayan region. J Phytol. 2011;3:49–59. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roy BA. Patterns of association between crucifers and their flower-mimic pathogens: host jumps are more common than coevolution or cospeciation. Evolution. 2001;55(1):41–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giraud T, Refrégier G, Le Gac M, et al. Speciation in fungi. Fungal Genet Biol. 2008;45(6):791–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giraud T, Gladieux P, Gavrilets S.. Linking the emergence of fungal plant diseases with ecological speciation. Trends Ecol Evol. 2010;25(7):387–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McTaggart AR, Shivas RG, van der Nest MA, et al. Host jumps shaped the diversity of extant rust fungi (Pucciniales). New Phytol. 2016;209(3):1149–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thines M. An evolutionary framework for host shifts-jumping ships for survival. New Phytol. 2019;224(2):605–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi Y-J, Thines M. Host jumps and radiation, not co-divergence drives diversification of obligate pathogens. A case study in downy mildews and Asteraceae. PloS One. 2015;10(7):e0133655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]