Abstract

Background

Delayed mortality in sepsis often is linked to a lack of resolution in the inflammatory cascade termed persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome (PICS). Limited research exists on PICS in pediatric patients with sepsis.

Research Question

What is the prevalence of pediatric PICS (pPICS) in patients who died of sepsis-related causes and what associated pathogen profiles and comorbidities did they have compared with those patients without pPICS who died from sepsis?

Study Design and Methods

A retrospective study of a single institution using a de-identified database from 1997 through 2020 for all patients aged 21 years or younger who died of culture-positive sepsis from a known source and who had laboratory data available were evaluated for the presence of pPICS.

Results

Among records extracted from the institutional database, 557 patients had culture-positive sepsis, with 262 patients having pPICS (47%). Patients with pPICS were more likely to have underlying hematologic or oncologic disease or cardiac disease. In addition, patients who had pPICS showed increased odds of associated fungal infection compared with those patients who did not (OR, 2.69; 95% CI, 1.59-4.61; P < .001). When assessing laboratory criteria, having a sustained absolute lymphocyte count of < 1.0 × 103/μL was most closely associated with having pPICS compared with other laboratory parameters. Finally, the results of multivariate logistic regression analysis indicated that patients with pPICS were more common in the cardiac ICU, as opposed to the PICU (OR, 3.43; CI, 1.57-7.64; P = .002).

Interpretation

Pediatric patients who died of a sepsis-related cause have a pPICS phenotype nearly one-half of the time. These patients are more likely to be in the cardiac ICU than the pediatric ICU and have associated fungal infections. Special attention should be directed toward this population in future research.

Key Words: cardiac disease, chronic critical illness, fungal infections, immunosuppression, sepsis

FOR EDITORIAL COMMENT, SEE PAGE 1071

Sepsis, defined as a dysregulated host response to infection, continues to be a significant public health concern affecting an estimated 48 million people every year with a mortality of 17% to 25%.1, 2, 3, 4 With protocol-driven management focused on early recognition along with improvements in critical care medicine, the overall mortality rate resulting from sepsis has decreased.5 However, an emerging population with chronic critical illness (CCI) continues to be vulnerable to sepsis-related morbidity and mortality.4,6, 7, 8 CCI in adults is defined by > 8 days in the ICU and organ dysfunction with at least one of the following criteria: prolonged mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy, sepsis or severe infection, severe wounds, or multiorgan failure.7 Although most of the literature on CCI focuses on adult populations, evidence exists suggesting that CCI also occurs in pediatric patients in the ICU.9 Although definitions of CCI in pediatric patients have not been established, suggested definitions include 14 days or more in the ICU with reliance on one or more technology-dependent devices for vital function or persistent multiorgan system involvement.7,9 Confined under the umbrella of CCI is a syndrome related to the immunologic phenotype of patients who survive an initial severe insult, but later demonstrate an insidious inflammatory state termed persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome (PICS).10 First described in the surgical literature, it is now believed to contribute significantly to the mortality of patients experiencing CCI.11,12 The criteria for PICS include a prolonged ICU length of stay, elevated inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP), evidence of immunosuppression as demonstrated by a reduced absolute lymphocyte count (ALC), and a catabolic state as delineated by low albumin or weight loss.10 In adult populations, the estimated prevalence is 44% of critically ill patients.12 Many of these patients later demonstrate secondary sepsis with a late mortality of 37% in the first 6 months after discharge.8,13 Refinement and application of the PICS criteria in critically ill adults have led to the identification of this high-risk subset; however, the extrapolation of these criteria to identify high-risk children is not well established.

Take-home Points.

Study Question: What number of pediatric patients who have died of a sepsis-related cause demonstrate evidence of persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome (PICS)?

Results: Among records extracted from the institutional database, 557 patients died of a culture-positive sepsis-related cause, with 262 patients meeting at least two of three laboratory criteria for pediatric PICS (pPICS) (47%). Those with pPICS showed an increased odds of associated fungal infections (OR, 2.69; 95% CI, 1.59-4.61; P < .001).

Interpretation: Pediatric patients who died of a sepsis-related cause demonstrated pPICS nearly one-half of the time and showed unique microbial risks associated with that phenotype.

Lymphopenia, a hallmark of the PICS criteria, has long been described in the pediatric literature. Previously, it was shown that pediatric patients with multiorgan failure and persistent lymphopenia (ALC < 1.0 × 103/μL) had a fivefold risk of nosocomial infections.14 Recent data examining pediatric patients admitted to a medical or surgical ICU that assessed CRP, arm circumference, and lymphocyte percent estimated a pPICS prevalence of 4.6%.15 Although this study examined only patients admitted to a medical or surgical PICU, it was noted that the overall prevalence of pPICS was higher in the surgical cohort, suggesting a unique predisposition in patients who underwent surgery.

In this study, we sought to estimate the prevalence of pPICS in children who died of culture-positive sepsis using a large institutional database and assessed if certain pathogens were more associated with a pPICS phenotype. We further compared the demographics and comorbidities of patients identified with and without pPICS among pediatric patients who died of sepsis and assessed laboratory trends over time. These data provided new details regarding the immunophenotype of pPICS and sepsis-related mortalities in children.

Study Design and Methods

Participants

The study used a de-identified electronic health record repository of the Vanderbilt University Medical Center called the Synthetic Derivative16 and was approved by the institutional review board (Identifier: 192203). Search criteria included all deceased patients born after 1997 who had an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth or 10th Revision, code associated with sepsis or a systemic infection-related code (e-Table 1). Records were reviewed manually for inclusion and exclusion criteria and data extraction. Inclusion criteria were any patient aged 21 years or younger on admission to the children’s hospital who died in the hospital and experienced a culture-positive sepsis event during the terminal hospitalization. Exclusions included sepsis that was not proximal to death (eg, infection with the primary cause of death being brain death resulting from trauma) or incomplete documentation.

Culture-Positive Status and pPICS Classification

Culture data were extracted from narrative documentation within time-stamped discharge or death summaries, daily progress notes, and autopsy reports. As an example, a patient’s death summary would document a culture-positive event in the hospital-course narrative, but no de-identified time stamp was linked within that narrative or other notes. Although culture data were confirmed within a hospitalization period, the lack of time-stamped culture data in relationship to laboratory reports prevented specific temporal associations. The relationship of culture-positive findings to death was verified by two independent physicians (S. G. P. and R. J. S.) based on either one positive culture result within 14 days of death or positive culture results with an identifiable infectious source that contributed to death as recorded in the hospital charting. Patients with positive culture data were examined for laboratory values consistent with PICS occurring at any point during hospitalization.10 The criteria used for pPICS were at least two of the following documented within 7 days of one another by time stamps: albumin level of < 3.0 g/dL, CRP level of > 10 mg/L, ALC of < 1.0 × 103/μL, or a combination thereof. We further divided individuals for supplemental analysis into those with confirmed pPICS, meeting three of three criteria, and those with probable pPICS, having two of three laboratory values with one laboratory value not documented (e-Table 2). Patients not meeting these laboratory criteria or patients with no documented laboratory values were included in the cohort with no pPICS. Patients who survived to hospital day 14 underwent further subanalysis using the 14-day cutoff as suggested in the adult literature.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical data were described as percentages and continuous data were described as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) unless otherwise specified. The test for association between categorical variables and the pPICS phenotype was a χ2 test with Yates correction for continuity. The test for the association between continuous variables and the pPICS phenotype was the one-way analysis of variance on means assuming equal variance. The Kruskal-Wallis rank-sum test was applied for the variables where the median and IQR are shown. To evaluate the performance of laboratory variables during the total hospitalization or within the first 14 days, univariate receiver operating characteristic curve analyses were performed comparing the median laboratory value per patient for the respective laboratory categories with the presence or absence of pPICS. Nonlinear, third-order regression lines of respective median laboratory values (with 95% CI likelihood) were performed to show temporal trends in values over time. Multivariate logistic regression was conducted to assess the associations between known covariates and odds of having pPICS. Variables adjusted for in the model as identified in prior literature included sex, age, inpatient location (PICU, neonatal ICU, cardiac ICU [CICU], or other), comorbidities, infectious organism type (gram positive, gram negative, fungus, or virus), and presence of sepsis on admission.17,18 Inpatient location was treated as a factor variable with PICU as the reference group. Adjusted ORs (aORs) were estimated for each covariate. To account for potential misclassification bias of pPICS resulting from the early onset of laboratory results abnormalities, a subgroup analysis was performed for patients hospitalized for 14 days or longer.

Data were analyzed using R version 4.13 software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing),19 and graphics were generated using GraphPad Prism version 9.2.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc.). Two-tailed P values are reported with Bonferroni family-wise adjustment; P values of < 1.72 × 103 (0.05 / m, where m = 29 for the number of tests for significance) were considered statistically significant.20

Results

Participants and pPICS

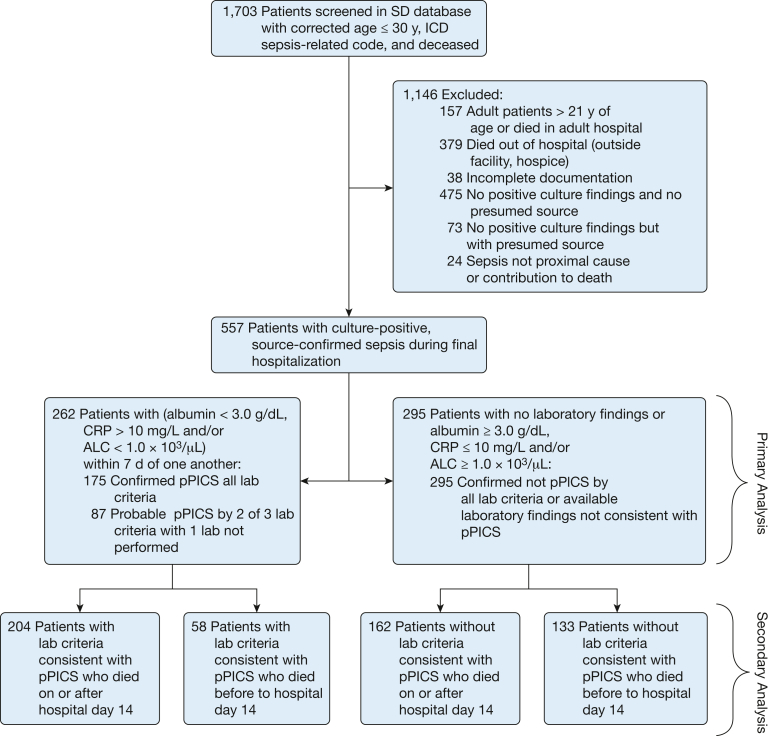

Of the 1,703 deceased patients with a sepsis-associated International Classification of Diseases code identified, 557 patients met the inclusion criteria and were identified with culture-positive, source-confirmed sepsis during the final hospitalization. Characteristics of this cohort are presented in Table 1. Of the cohort, 262 patients (47%) were classified as having pPICS, meeting at least two of the lymphopenia, elevated CRP, and hypoalbuminemia criteria (Fig 1); 175 patients (31%) met three criteria for pPICS, and 87 patients (16%) met two of three criteria (e-Table 2). The 262 patients with pPICS were older, with a median age of 0.75 year (IQR, 0.24-8.58 years) vs 0.22 year (IQR, 0.05-0.97 year) for those without pPICS (P < .001). pPICS occurred with higher frequency in patients with hematologic or oncologic disease (29% vs 17.3%) with an aOR of 3.19 (CI, 1.62-6.43; P = .001) (Table 2). Prematurity was associated negatively with the pPICS phenotype, with 28.6% in the pPICS group vs 63.1% in the non-pPICS group being born prematurely (P < .001); however, this did not remain true when adjusted for in the logistic regression. Multivariate logistic regression analysis did show that the odds of a pPICS phenotype were higher in patients admitted to the CICU relative to those admitted to the PICU (aOR, 3.43; CI, 1.57-7.64; P = .002). Of the 557 patients, 366 patients (65.7%) were hospitalized for at least 14 days and were included in a subgroup analysis. The results of this analysis agreed with the primary results in that the odds of pPICS were higher in patients with hematologic or oncologic disease relative to those without (aOR, 2.81; CI, 1.07-7.66; P = .038) and in patients admitted to the CICU relative to those admitted to the PICU (aOR, 2.95; CI, 1.13-7.83; P = .028) (Table 2). A summary of the characteristics of those with pPICS, probable pPICS, and no pPICS is provided in e-Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients With pPICS vs Those Without pPICS

| Characteristic | Total (N = 557) | pPICS (n = 262) | No pPICS (n = 295) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 288 (51.7) | 134 (51.1) | 154 (52.2) |

| Age, y | 0.40 (0.09-3.49) | 0.75 (0.24-8.58) | 0.22 (0.05-0.97) |

| Hospital length of stay, d | 25 (7-69) | 37.5 (17-86) | 17 (4-52) |

| Race | |||

| White | 354 (63.6) | 178 (67.9) | 176 (59.7) |

| Black | 92 (16.5) | 41 (15.6) | 51 (17.3) |

| Othera | 21 (3.8) | 12 (4.6) | 9 (3.1) |

| Unreported | 90 (16.2) | 31 (11.8) | 59 (20.0) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 44 (7.9) | 28 (10.7) | 16 (5.4) |

| Non-Hispanic | 413 (74.1) | 201 (76.7) | 212 (71.9) |

| Unreported | 100 (18.0) | 33 (12.6) | 67 (22.7) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Prematurity | 261 (46.9) | 75 (28.6) | 186 (63.1) |

| Genetic | 134 (24.1) | 61 (23.3) | 73 (24.7) |

| Cardiovascular | 209 (37.5) | 121 (46.2) | 88 (29.8) |

| Respiratory | 125 (22.4) | 39 (14.9) | 86 (29.2) |

| Hematologic or oncologic | 127 (22.8) | 76 (29) | 51 (17.3) |

| Neurologic | 115 (20.6) | 37 (14.1) | 78 (26.4) |

| GI | 94 (16.9) | 36 (13.7) | 58 (19.7) |

| Renal | 67 (12.0) | 23 (8.8) | 44 (14.9) |

| Endocrine | 56 (10.1) | 19 (7.3) | 37 (12.5) |

| Otherb | 64 (11.5) | 22 (8.4) | 42 (14.2) |

| No. of comorbidities | |||

| 0 | 47 (8.4) | 14 (5.3) | 33 (11.2) |

| 1 | 311 (55.8) | 153 (58.4) | 158 (53.6) |

| 2 | 137 (24.6) | 64 (24.4) | 73 (24.7) |

| ≥ 3 | 62 (11.1) | 31 (11.8) | 31 (10.5) |

| Year of hospitalization | |||

| 1997-2010 | 271 (48.7) | 123 (46.9) | 148 (50.2) |

| 2011-2020 | 286 (51.3) | 139 (53.1) | 147 (48.8) |

Data are presented as No. (%) or median (interquartile range). pPICS = pediatric persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome.

Includes Asian, Native American, and Mediterranean.

Includes burns, failure to thrive, and rheumatologic and autoimmune disorders.

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing inclusion and exclusion criteria and subphenotype breakdown. ALC = absolute lymphocyte count; CRP = C-reactive protein; ICD = International Classification of Diseases; pPICS = pediatric persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome; SD = Synthetic Derivative.

Table 2.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Characteristics Correlated With pPICS

| Parameter | Mortality on Any Day of Hospitalization (n = 557) |

Mortality on Day 14 or Later of Hospitalization (n = 366) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI | P Value | OR | CI | P Value | |

| (Intercept) | 0.45 | 0.20-0.99 | .047 | 0.93 | 0.33-2.62 | .896 |

| Sex | 0.98 | 0.66-1.46 | .920 | 0.77 | 0.46-1.26 | .301 |

| Age | 1.07 | 1.02-1.12 | .010 | 1.06 | 0.99-1.14 | .094 |

| Sepsis on admissiona | 0.87 | 0.52-1.46 | .603 | 0.86 | 0.41-1.79 | .681 |

| Inpatient location (PICU as reference) | ||||||

| NICU | 0.81 | 0.41-1.63 | .558 | 0.59 | 0.24-1.45 | .246 |

| CICU | 3.43 | 1.57-7.64 | .002 | 2.95 | 1.13-7.83 | .028 |

| Otherb | 0.49 | 0.18-1.27 | .146 | 0.55 | 0.15-1.96 | .348 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Prematurity | 0.61 | 0.35-1.08 | .090 | 0.71 | 0.36-1.44 | .335 |

| Genetic | 1.16 | 0.67-2.01 | .602 | 0.77 | 0.40-1.49 | .439 |

| Cardiovascular | 1.49 | 0.80-2.76 | .203 | 1.47 | 0.70-3.09 | .308 |

| Respiratory | 0.63 | 0.36-1.10 | .107 | 0.55 | 0.28-1.05 | .072 |

| Hematologic or oncologic | 3.19 | 1.62-6.43 | .001 | 2.81 | 1.07-7.66 | .038 |

| Neurologic | 0.46 | 0.24-0.86 | .017 | 0.60 | 0.28-1.27 | .189 |

| GI | 1.15 | 0.57-2.30 | .694 | 1.12 | 0.47-2.67 | .789 |

| Renal | 0.78 | 0.29-2.05 | .620 | 0.64 | 0.15-2.45 | .528 |

| Endocrine | 0.89 | 0.22-3.77 | .869 | 1.59 | 0.23-14.69 | .659 |

| Otherc | 0.69 | 0.28-1.68 | .414 | 1.14 | 0.33-4.06 | .836 |

| Infectious organisms | ||||||

| Gram positive | 1.20 | 0.78-1.84 | .413 | 1.22 | 0.72-2.08 | .461 |

| Gram negative | 1.32 | 0.85-2.05 | .219 | 1.03 | 0.60-1.79 | .909 |

| Fungus | 2.69 | 1.59-4.61 | < .001 | 2.03 | 1.11-3.75 | .022 |

| Virus | 1.54 | 0.86-2.78 | .152 | 1.24 | 0.58-2.73 | .583 |

CICU = cardiac ICU; NICU = neonatal ICU; pPICS = pediatric persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome.

Sepsis as documented in the admitting history and physical as a reason for admission.

Includes floor, ED, and operating room.

Includes burns, failure to thrive, rheumatologic, and autoimmune disorders.

Culture Results

Our study also identified the most common infectious organisms in the pPICS phenotype. The pPICS phenotype included 565 pathogen isolates compared with 508 isolates in the no pPICS group (Table 3), with a higher number of unique organisms and sources in the pPICS group (e-Table 3). One hundred twenty fungal isolates were detected in total with 88 isolates (73.3%) occurring in patients with pPICS and 32 isolates (26.7%) occurring in patients with no pPICS (P < .001). A multivariate logistic regression showed a more than two times odds of pPICS in patients with fungal infection relative to those without (aOR, 2.69; CI, 1.59-4.61; P < .001) (Table 2). Similar odds of fungal infections in patients with pPICS were shown in those who survived to day 14 of hospitalization (aOR, 2.03; CI, 1.11-3.75; P = .022). The complete list of organisms by immunologic phenotype is provided in e-Table 4.

Table 3.

Top 25 Organisms Isolated and OR to Presence of pPICS vs No pPICS

| Organisms Isolated | pPICS (n = 565 Isolates) | No pPICSa (n = 508 Isolates) | Totala (n = 1,073 Isolates) | OR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-negative species | ||||||

| Pseudomonas speciesb | 35 | 49 | 84 | 0.62 | 0.40-0.96 | .040 |

| Escherichia coli | 24 | 32 | 56 | 0.66 | 0.39-1.12 | .134 |

| Klebsiella speciesb | 29 | 20 | 49 | 1.32 | 0.75-2.34 | .382 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 17 | 16 | 33 | 0.95 | 0.47-1.84 | > .999 |

| Enterobacter speciesb | 17 | 16 | 33 | 0.95 | 0.47-1.84 | > .999 |

| Gram-negative rod speciesc | 10 | 19 | 29 | 0.46 | 0.22-0.96 | .059 |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 11 | 13 | 24 | 0.76 | 0.34-1.67 | .540 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 9 | 12 | 21 | 0.67 | 0.27-1.65 | .386 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 10 | 7 | 17 | 1.29 | 0.48-3.35 | .635 |

| Serratia speciesb | 13 | 3 | 16 | 3.96 | 1.16-13.12 | .023 |

| P aeruginosa | 4 | 11 | 15 | 0.32 | 0.12-1.03 | .065 |

| Total gram-negative isolates | 230 | 232 | 462 | 0.82 | 0.64-1.04 | .110 |

| Gram-positive species | ||||||

| S aureus | 40 | 44 | 84 | 0.80 | 0.51-1.25 | .364 |

| Enterococcus speciesb | 36 | 21 | 57 | 1.58 | 0.93-2.79 | .133 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 23 | 28 | 51 | 0.73 | 0.41-1.27 | .315 |

| Coagulase-negativeStaphylococcus speciesb | 23 | 27 | 50 | 0.76 | 0.42-1.31 | .385 |

| Gram-positive cocci speciesc | 12 | 21 | 33 | 0.50 | 0.25-1.02 | .075 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 16 | 13 | 29 | 1.11 | 0.54-2.24 | .852 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 7 | 8 | 15 | 0.78 | 0.30-2.16 | .796 |

| Clostridioides difficile | 9 | 5 | 14 | 1.63 | 0.57-4.36 | .430 |

| Group B Streptococcus speciesb | 2 | 11 | 13 | 0.16 | 0.04-0.65 | .009 |

| Total gram-positive isolates | 200 | 202 | 403 | 0.85 | 0.67-1.09 | .209 |

| Fungal species | ||||||

| Candida speciesb | 23 | 13 | 36 | 1.62 | 0.80-3.31 | .179 |

| Fungus not specifiedc | 11 | 3 | 14 | 3.34 | 1.04-11.25 | .061 |

| Aspergillus speciesb | 13 | 0 | 13 | Infinite | 3.15-infinite | Indeterminate |

| Total fungal isolates | 89 | 31 | 120 | 2.87 | 1.89-4.37 | < .001 |

| Viral species | ||||||

| Adenovirus | 10 | 2 | 12 | 4.55 | 1.07-20.87 | .041 |

| Herpes simplex virus 2 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 0 | 0.00-0.34 | Indeterminate |

| Total viral isolates | 51 | 48 | 99 | 1.01 | 0.67-1.50 | > .999 |

Data are presented as No., unless otherwise indicated. pPICS = pediatric persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome.

No pPICS isolates exclude two cultures with positive results for Toxoplasma gondii.

Species not specifically identified.

Genus not specifically identified.

Laboratory Trends in Patients With pPICS vs Those Without pPICS

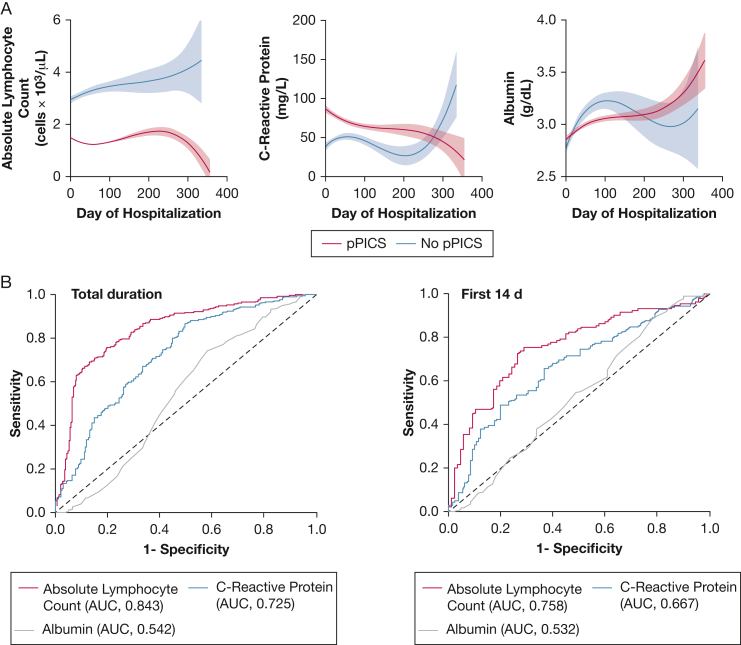

Comparison of the laboratory data from patients with pPICS compared with those without pPICS by day of hospitalization showed an expected reduced lymphocyte count in patients with pPICS that decreased over the hospital length of stay (Fig 2A). Trends in the CRP by hospital day in the pPICS vs the no pPICS group revealed the CRP level to be elevated in both groups, although with inverse trend lines. Albumin level demonstrated no similar trends by hospital day in either the pPICS or no pPICS groups, suggesting that albumin level was of limited diagnostic utility. The summation of the laboratory characteristics concerning patients classified as having pPICS vs those without pPICS is shown by receiver operating characteristic curves in Figure 2B. Because of the dynamic nature of laboratory values over time where values can alternate above and below the preestablished threshold, we took the median laboratory value for each patient throughout hospitalization and tested the performance against them being classified as having pPICS. Among the three laboratory criteria, the ALC performed the best (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, 0.84; P < .001). In comparison, CRP and albumin levels performed less well. Subgroup analysis of median laboratory values within the first 14 days of hospitalization for those who survived to day 14 or more showed similar performance as ALC in comparison with CRP and albumin for patients with pPICS. Receiver operating characteristic curves showing the correlation of ALC, CRP, and albumin levels based on pathogen type are provided in e-Figure 1.

Figure 2.

A, Nonlinear, third-order regression lines of respective median laboratory values (with 95% CI likelihood) by day of hospitalization for pPICS (red) vs no pPICS (blue). B, Receiver operating characteristic curves for absolute lymphocyte count (red), C-reactive protein (blue), and albumin (gray) for the median laboratory values for the total duration of hospitalization (left) or in the first 14 days of hospitalization for survivors to that time point (right) with associated AUCs for no pPICS (control participants) vs pPICS (patients). AUC = area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; pPICS = pediatric persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome.

Discussion

Since the development of modern critical care medicine in the 1970s, a slow but steady improvement in sepsis survival has occurred.5,21,22 However, it has become increasingly evident that many patients with sepsis die not in the early phases, but rather in the later, more protracted stages. Previously, these phases were described as a compensatory antiinflammatory response syndrome that followed the initial systemic inflammatory response syndrome. More recently, it has been recognized that the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and compensatory antiinflammatory response syndrome can occur simultaneously, and when neither process is abated successfully, PICS occurs.10 Patients with PICS have evidence of dual proinflammatory and antiinflammatory states, as seen by lymphopenia, hypoalbuminemia, and elevated acute-phase reactants, and PICS has been associated with increased late mortality.23 A majority of the literature regarding PICS pertains to adult populations, and the impact of such phenotypes in critically ill children, particularly those with sepsis, remains mostly undescribed.

In this detailed examination of > 20 years of de-identified medical records at a single institution, we identified 557 pediatric patients with culture-positive sepsis as a proximal cause of hospital-related mortality. We further classified the immunologic phenotype based on previously published laboratory classifications to estimate the occurrence of pPICS within this cohort. At our single institution, approximately 47% of patients who died of culture-positive sepsis met at least two of three pPICS laboratory criteria. This group was more likely to have cardiovascular and hematologic or oncologic diseases, indicating that clinicians should be more cognizant of this phenotype in these populations. Furthermore, although we did not find global differences in the type of gram-positive or gram-negative organisms identified between patients with pPICS vs those without pPICS, we found that patients with pPICS were more likely to have fungal infections and more total clinical isolates. It is worth noting that in a subgroup analysis, the pathogen-associated outcomes did not differ between those who died at any point vs those who died after 14 days of hospitalization. Although this study was not designed to assess the onset of immune dysfunction, the original studies in PICS showed differences in immune cell populations as early as day 7 of hospitalization.24 Additionally, a more recent pediatric study suggested that on presentation, 39% of pediatric patients with sepsis show evidence of immunoparalysis.25 Therefore, although 14 days has been considered a discriminating time point, immunologic evidence exists that the phenotype may occur much earlier in the hospital course. Nevertheless, our data provide new insight into the pPICS phenotype within the pediatric population and suggest possible roles for preventative measures in managing this unique population.

A limited number of investigations into PICS in pediatric populations exist. One study by Hauschild et al15 prospectively examined the prevalence and outcomes of pPICS in critically ill children over a 3-year period. They found the prevalence of pPICS to be approximately 4.6% in pediatric patients admitted to the ICU with an increased adjusted odds of mortality of 7.14. Patients with pPICS experienced increased length of stay, vasoactive and ventilator days, antibiotic use, and nosocomial infections. Although this is one of the few studies identified that specifically addressed pPICS, the phenomenon of an immunosuppressive state in pediatric critical illness long has been described. In the mid 2000s, it was recognized that in critically ill children, those with lymphocyte dysfunction show a significant prevalence of worsened outcomes.14 Specifically, prolonged lymphopenia for > 7 days was associated with 5.5-times greater odds of a nosocomial infection developing. Other studies confirmed worse outcomes in patients with immune dysfunction after sepsis.26, 27, 28 Our data agree with these studies and suggest that absolute lymphopenia is an important marker of systemic immune dysfunction and a potential predictor of infection.29 In comparison with lymphopenia, CRP and albumin values were less sensitive in our data. Certainly prealbumin, another marker of protein production, is likely a better discriminator of nutritional status than albumin; however, prealbumin rarely was recorded in the dataset, and more recently, even the usefulness of prealbumin has been questioned.30 Likewise, many places have augmented CRP values with procalcitonin in delineating concerns for serious infections, but both show poor predictive value regarding longitudinal outcomes.31 Other routine values obtained that may offer predictive value in critical illness outcomes include ABO blood type, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratios, and red cell distribution width.32, 33, 34 Adding these, along with better assessments of nutritional status such as creatinine height index,35 may provide for a clearer picture of the nutritional and immunologic phenotype in this population.

In contrast to the known association of nosocomial infections in PICS, the types of pathogens these patients die of are less clear. Hall et al29 showed a predominance of pathogens in immunosuppressed patients as either gram negative or fungal, although no further analysis was performed. No specific studies in pPICS have examined the type of pathogens encountered, but one survey of 180 hospitals showed the top five pathogens in patients in the ICU to be Pseudomonas aeruginosa (12.4%), Staphylococcus aureus (12.3%), coagulase-negative staphylococci (10.2%), Candida species (10.1%), and Enterobacter species (8.6%).36 Our results were strikingly similar to those findings from > 2 decades ago, suggesting that the bacterial pathogens causing infectious diseases in patients in the ICU remain the same. However, we did not find global differences in bacteria between patients with and without pPICS.37 Instead, we found significant differences in fungal-related sepsis mortality rates in the pPICS group. Although the concept of empirically providing antifungal coverage to all critically ill patients was refuted by the Empirical Antifungal Treatment in ICUS (EMPIRICUS) trial, most critical care sepsis trials are not designed to address specific phenotypes or subgroups.37 While adult studies have not shown the benefits of prophylactic fungal treatment, its use in extremely preterm infants has been shown to prevent fungal infections, suggesting that specific pediatric populations may benefit from prophylactic antifungals.38 In addition, it has been recognized in adults that lymphopenia is an independent risk factor for mortality related to candidal infections.31 Patients with pPICS likely should receive similar scrutiny and research evaluating the use of prophylactic treatment for fungal infections if they meet defined risk factors within subcohorts of patients. Additional study into reversing the immunophenotype in pPICS also is needed. Data in adults with sepsis who show evidence of immunosuppression demonstrate the use of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor may lead to improved outcomes.39, 40, 41 Currently, two ongoing multicenter trials are evaluating granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in pediatric sepsis with immunosuppression to assess phenotype reversibility.42,43 These, along with other postulated therapies such as IL-7 treatment, may lead to better ways to manage sepsis-related immunosuppression.44,45

Of the patients who demonstrated a pPICS phenotype and had underlying comorbidities, we found that hematologic or oncologic disease or cardiac disorders were most associated. This is not surprising given that data show that patients with oncologic diseases have a high burden of sepsis.46 We likewise confirmed the known observation that neonates are the most prevalent pediatric population to die of sepsis. However, when breaking down the location of sepsis-related mortalities, the highest proportion of critically ill pediatric patients who died of sepsis with a pPICS phenotype was in the CICU. Although this group showed the fewest sepsis-related deaths, approximately 78% of patients who died of sepsis in the CICU showed a pPICS phenotype during hospitalization. Why this specific population would be more susceptible is unclear, but one possibility could be related to the two-hit hypothesis in the development of PICS. The cardiopulmonary bypass necessary for the correction of congenital heart disease is known to induce a systemic inflammatory response.47 This initial hit causes changes within the innate immune system, with evidence of reduced monocyte human leukocyte antigen–DR isotype expression after bypass.48 These changes in monocyte human leukocyte antigen–DR isotype expression typically are associated with T-cell apoptosis, along with other changes within the innate and adaptive immune systems.49 Bypass, coupled with the use of antiinflammatory agents such as intraoperative corticosteroids, may contribute to the increased prevalence of pPICS observed in this study.50 Validation of these findings within the pediatric population with congenital heart disease warrants further investigation.

Our study has several important limitations. First, being a retrospective analysis of de-identified medical records, the extraction of patient data was dependent on hospital billing codes, which can have inherent variability.51 Second, the overall number of confirmed patients with pPICS and the number of patients with positive culture findings may be underestimated, given that the electronically scrubbed data source included some entries with incomplete laboratory data. We combined patients having two of the three laboratory criteria into the pPICS cohort, which may have contributed to an overestimation of the representative percent. Third, because we examined only patients who had died, no culture-positive survivor cohort could provide a comparative analysis regarding the overall prevalence of pPICS in sepsis or the pathogens present. Therefore, it should not be inferred that the prevalence of pPICS among sepsis-related mortalities is indicative of the prevalence of pPICS among patients without sepsis or sepsis survivors. Fourth, a notable limitation is the lack of temporal association between laboratory data and hospital events with culture data. This is because of an inherent limitation within the Synthetic Derivative database regarding how de-identified data are stored in the system. Specifically within the database, the time stamps of laboratory data do not correspond to culture data and the culture data can be correlated only within a hospitalization by manual chart extraction from provider notes when it was chosen to be recorded. The lack of time-stamped positive culture findings also limited our determination of clinical events in specific populations, such as correlation to immunosuppressive treatments in patients oncologic disease or chylothorax in postoperative patients with cardiac disease, which could have contributed to lymphopenia or other pPICS laboratory criteria and a sepsis event. Although we examined patients with the laboratory criteria of low ALC, elevated CRP, and low albumin with prolonged hospital stay that met the current clinical definition of pPICS, patients with hospital-acquired confounders (eg, medication-induced immunosuppression) do not necessarily have the same inherent risk factors as those who demonstrate pPICS after a newly acquired disease (eg, trauma). The descriptive nature of this study instead should guide focus on future research to more clearly delineate potential subgroups of what is otherwise a heterogeneous cohort of patients with pPICS and CCI. Fifth, because PICS in general is dynamic and patients may have intermittent periods of meeting the criteria and then not in the same hospitalization, or because no laboratory data were obtained by the treating team to determine if pPICS was present, we cannot offer specific predictive measures of laboratory cutoff values in the development of infections or pPICS on days of hospitalization. Finally, because the data presented are the result of associations within a retrospective single-center study, no wider causality should be surmised.

Interpretation

We herein estimated the prevalence of pPICS in children who died of sepsis within a tertiary children’s hospital over > 20 years. The development of pPICS occurred in approximately 47% of all patients who died of culture-positive sepsis. In addition, it was found that patients who died and demonstrated a pPICS phenotype were older, showed increased odds of mortality related to fungal infections, and demonstrated increased likelihood of having underlying hematologic or oncologic disease or cardiac disease, with the highest overall proportion occurring in patients in the CICU. Further investigations are needed to assess the overall prevalence and risks of pPICS developing as well as potentially modifiable factors that could improve outcomes in this uniquely vulnerable pediatric patient population.

Funding/Support

The data set(s) used for the analyses described were obtained from Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s BioVU, which is supported by numerous sources: institutional funding, private agencies, and federal grants. These include the National Institutes of Health-funded Shared Instrumentation Grant [Grant S10RR025141] and Clinical and Translational Science Awards [Grants UL1TR002243, UL1TR000445, and UL1RR024975]. Analysis also was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant R35 GM138191] and in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences [CTSA Grant UL1TR002243 to Vanderbilt University]. R. J. S. is supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant R35 GM138191].

Financial/Nonfinancial Disclosures

None declared.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: S. G. P. is responsible for the finished work, data, conduct of the study and decision to publish. S. G. P., S. L. V. D., and R. J. S. conceptualized and designed the study and data collection instruments, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. W. G., J. R., C. J. L., and C. K. L. performed data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation and critically revised the work for publication.

Role of sponsors: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript or its acceptance.

Additional information: The e-Figure and e-Tables are available online under “Supplementary Data.”

Footnotes

Dr Van Driest is currently affiliated with the Research Program, Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

S. G. P. and R. J. S. contributed equally as co-corresponding authors.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Evans L., Rhodes A., Alhazzani W., et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(11):1181–1247. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06506-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudd K.E., Johnson S.C., Agesa K.M., et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990–2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2020;395(10219):200–211. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32989-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleischmann-Struzek C., Mellhammar L., Rose N., et al. Incidence and mortality of hospital- and ICU-treated sepsis: results from an updated and expanded systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(8):1552–1562. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06151-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy Salem S., Graham R. Chronic illness in pediatric critical care. Front Pediatr. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.686206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin G.S., Mannino D.M., Eaton S., Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(16):1546–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jurasinski P., Schindler C.A. An emerging population: the chronically critically ill. J Pediatr Health Care. 2014;28(6):550–554. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shapiro M.C., Henderson C.M., Hutton N., Boss R.D. Defining pediatric chronic critical illness for clinical care, research, and policy. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(4):236–244. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2016-0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stortz J.A., Mira J.C., Raymond S.L., et al. Benchmarking clinical outcomes and the immunocatabolic phenotype of chronic critical illness after sepsis in surgical intensive care unit patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;84(2):342–349. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shappley R.K.H., Noles D.L., Spentzas T. Pediatric chronic critical illness: validation, prevalence, and impact in a children’s hospital. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2021;22(12):e636–e639. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000002802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mira J.C., Brakenridge S.C., Moldawer L.L., Moore F.A. Persistent inflammation, immunosuppression and catabolism syndrome. Crit Care Clin. 2017;33(2):245–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gentile L.F., Cuenca A.G., Efron P.A., et al. Persistent inflammation and immunosuppression. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72(6):1491–1501. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318256e000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stortz J.A., Murphy T.J., Raymond S.L., et al. Evidence for persistent immune suppression in patients who develop chronic critical illness after sepsis. Shock. 2018;49(3):249–258. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guirgis F.W., Brakenridge S., Sutchu S., et al. The long-term burden of severe sepsis and septic shock: sepsis recidivism and organ dysfunction. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81(3):525–532. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Felmet K.A., Hall M.W., Clark R.S.B., Jaffe R., Carcillo J.A. Prolonged lymphopenia, lymphoid depletion, and hypoprolactinemia in children with nosocomial sepsis and multiple organ failure. J Immunol. 2005;174(6):3765–3772. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauschild D.B., Oliveira L.D.A., Ventura J.C., et al. Persistent inflammation, immunosuppression and catabolism syndrome (PICS) in critically ill children is associated with clinical outcomes: a prospective longitudinal study. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2021;34(2):365–373. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roden D., Pulley J., Basford M., et al. Development of a large-scale de-identified DNA biobank to enable personalized medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84(3):362–369. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thavamani A., Umapathi K.K., Dhanpalreddy H., et al. Epidemiology, clinical and microbiologic profile and risk factors for inpatient mortality in pediatric severe sepsis in the United States from 2003 to 2014: a large population analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(9):781–788. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiss S.L., Balamuth F., Hensley J., et al. The epidemiology of hospital death following pediatric severe sepsis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18(9):823–830. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.R Core Team R: a language and environment for statistical computing. 2022. R Foundation for Statistical Computing website. Accessed March 10, 2023. http://www.R-project.org/

- 20.Armstrong R.A. When to use the Bonferroni correction. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2014;34(5):502–508. doi: 10.1111/opo.12131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luhr R., Cao Y., Soderquist B., Cajander S. Trends in sepsis mortality over time in randomised sepsis trials: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of mortality in the control arm, 2002-2016. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):241. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2528-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sehgal M., Ladd H.J., Totapally B. Trends in epidemiology and microbiology of severe sepsis and septic shock in children. Hosp Pediatr. 2020;10(12):1021–1030. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2020-0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yende S., Kellum J.A., Talisa V.B., et al. Long-term host immune response trajectories among hospitalized patients with sepsis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathias B., Delmas A.L., Ozrazgat-Baslanti T., et al. Human myeloid-derived suppressor cells are associated with chronic immune suppression after severe sepsis/septic shock. Ann Surg. 2017;265(4):827–834. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindell R.B., Zhang D., Bush J., et al. Impaired lymphocyte responses in pediatric sepsis vary by pathogen type and are associated with features of immunometabolic dysregulation. Shock. 2022;57(6):191–199. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carcillo J.A., Michael Dean J., Holubkov R., et al. The randomized comparative pediatric critical illness stress-induced immune suppression (CRISIS) prevention trial. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13(2):165–173. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31823896ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muszynski J.A., Nofziger R., Moore-Clingenpeel M., et al. Early immune function and duration of organ dysfunction in critically ill children with sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(3):361–369. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201710-2006OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Remy S., Kolev-Descamps K., Gossez M., et al. Occurrence of marked sepsis-induced immunosuppression in pediatric septic shock: a pilot study. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s13613-018-0382-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall M.W., Knatz N.L., Vetterly C., et al. Immunoparalysis and nosocomial infection in children with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37(3):525–532. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-2088-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evans D.C., Corkins M.R., Malone A., et al. The use of visceral proteins as nutrition markers: an ASPEN position paper. Nutr Clin Pract. 2021;36(1):22–28. doi: 10.1002/ncp.10588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryoo S.M., Han K.S., Ahn S., et al. The usefulness of C-reactive protein and procalcitonin to predict prognosis in septic shock patients: a multicenter prospective registry-based observational study. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):6579. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42972-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bazick H.S., Chang D., Mahadevappa K., Gibbons F.K., Christopher K.B. Red cell distribution width and all-cause mortality in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(8):1913–1921. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31821b85c6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ham S.Y., Yoon H.J., Nam S.B., Yun B.H., Eum D., Shin C.S. Prognostic value of neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio and mean platelet volume/platelet ratio for 1-year mortality in critically ill patients. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78476-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slade R., Alikhan R., Wise M.P., Germain L., Stanworth S., Morgan M. Impact of blood group on survival following critical illness: a single-centre retrospective observational study. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2019;6(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2019-000426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bistrian B.R., Mogensen K.M., Christopher K.B. Plea for reapplication of some of the older nutrition assessment techniques. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2020;44(3):391–394. doi: 10.1002/jpen.1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jarvis W.R. Epidemiology of nosocomial fungal infections, with emphasis on Candida species. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20(6):1526–1530. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.6.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Timsit J.F., Azoulay E., Schwebel C., et al. Empirical micafungin treatment and survival without invasive fungal infection in adults with ICU-acquired sepsis, Candida colonization, and multiple organ failure: the EMPIRICUS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(15):1555–1564. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.14655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferreras-Antolín L., Sharland M., Warris A. Management of invasive fungal disease in neonates and children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019;38(6S suppl 1):s2–s6. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bo L., Wang F., Zhu J., Li J., Deng X. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) for sepsis: a meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2011;15(1):R58. doi: 10.1186/cc10031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meisel C., Schefold J.C., Pschowski R., et al. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor to reverse sepsis-associated immunosuppression: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(7):640–648. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0363OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mu X., Liu K., Li H., Wang F.S., Xu R. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor: an immunotarget for sepsis and COVID-19. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18(8):2057–2058. doi: 10.1038/s41423-021-00719-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Institutes of Health Clinical Center . National Institutes of Health; 2018. GM-CSF for reversal of immunoparalysis in pediatric sepsis-induced MODS study (GRACE). NCT03769844. ClinicalTrials.gov.https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03769844 Updated February 28, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 43.National Institutes of Health Clinical Center. GM-CSF for Reversal of Immunoparalysis in Pediatric Sepsis-induced MODS (GRACE-2). NCT05266001. ClinicalTrials.gov. National Institutes of Health. Updated February 8, 2023. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05266001

- 44.Hotchkiss R.S., Moldawer L.L., Opal S.M., Reinhart K., Turnbull I.R., Vincent J.L. Sepsis and septic shock. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2 doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Daix T., Mathonnet A., Brakenridge S., et al. Intravenously administered interleukin-7 to reverse lymphopenia in patients with septic shock: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intensive Care. 2023;13(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s13613-023-01109-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watson R.S., Carcillo J.A. Scope and epidemiology of pediatric sepsis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6(3 suppl):s3–s5. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000161289.22464.C3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krispinsky L.T., Stark R.J., Parra D.A., et al. Endothelial-dependent vasomotor dysfunction in infants after cardiopulmonary bypass. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2020;21(1):42–49. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000002049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Allen M.L., Peters M.J., Goldman A., et al. Early postoperative monocyte deactivation predicts systemic inflammation and prolonged stay in pediatric cardiac intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(5):1140–1145. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200205000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hotchkiss R.S., Monneret G., Payen D. Sepsis-induced immunosuppression: from cellular dysfunctions to immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(12):862–874. doi: 10.1038/nri3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Saet A., Zeilmaker-Roest G.A., Stolker R.J., Bogers A., Tibboel D. Methylprednisolone in pediatric cardiac surgery: is there enough evidence? Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.730157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fleischmann-Struzek C., Thomas-Ruddel D.O., Schettler A., et al. Comparing the validity of different ICD coding abstraction strategies for sepsis case identification in German claims data. PLoS One. 2018;13(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.