Abstract

In metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC), disease volume plays an integral role in guiding treatment recommendations, including selection of docetaxel therapy, metastasis-directed therapy, and radiation to the prostate. Although there are multiple definitions of disease volume, they have commonly been studied in the context of metastases detected via conventional imaging (CIM). One such numeric definition of disease volume, termed oligometastasis, is heavily dependent on the sensitivity of the imaging modality. We performed an international multi-institutional retrospective review of men with metachronous oligometastatic CSPC (omCSPC), detected via either advanced molecular imaging alone (AMIM) or CIM. Patients were compared with respect to clinical and genomic features using the Mann-Whitney U test, Pearson’s χ2 test, and Kaplan-Meier overall survival (OS) analyses with a log-rank test. A total of 295 patients were included for analysis. Patients with CIM-omCSPC had significantly higher Gleason grade group (p = 0.032), higher prostate-specific antigen at omCSPC diagnosis (8.0 vs 1.7 ng/ml; p < 0.001), more frequent pathogenic TP53 mutations (28% vs 17%; p = 0.030), and worse 10-yr OS (85% vs 100%; p < 0.001). This is the first report of clinical and biological differences between AMIM-detected and CIM-detected omCSPC. Our findings are particularly important for ongoing and planned clinical trials in omCSPC.

Patient summary:

Metastatic prostate cancer with just a few metastases only detected via newer scanning methods (called molecular imaging) is associated with fewer high-risk DNA mutations and better survival in comparison to metastatic cancer detected via conventional scan methods.

We demonstrate that patients with oligometastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer detected via molecular imaging alone have less aggressive disease, as indicated by fewer high-risk pathogenic DNA mutations, and better overall survival in comparison to patients with oligometastasis detected via conventional imaging.

Despite several advances in systemic therapy, metastatic prostate cancer remains incurable. A growing number of studies have evaluated the role of metastasis-directed therapy (MDT) in the management of patients with a limited distribution of metastasis, termed oligometastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (omCSPC). Data from randomized trials have demonstrated that among men with omCSPC, MDT improves biochemical progression–free survival [1–3] and several additional studies are under way. Importantly, the definition of omCSPC relies on the sensitivity of the imaging used for detection and is generally considered as fewer than three to five detectable lesions.

Historically, distant prostate cancer staging has been evaluated via a bone scan and computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis (conventional imaging, CIM). More recently, advanced molecular imaging (AMIM) modalities such as 11C-choline and prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) positron emission tomography (PET) have demonstrated better sensitivity. The emergence and use of AMIM has led to “leadtime bias”, with earlier detection of the metastatic state and better prognosis than for CIM-detected disease, which has cast uncertainty on how to apply the results from recent phase 3 trials that are based on CIM. Here we compare clinical and genomic differences between AMIM-detected and CIM-detected omCSPC.

We performed an international multi-institutional retrospective review of men with metachronous omCSPC who underwent next-generation sequencing (NGS) of either their primary tumor or metastatic site. Prespecified genes and pathways of interest were determined on the basis of literature reports for mCSPC and all comparisons performed are reported here. Multiple different NGS platforms were used, so patients for whom not all genes of interest were sequenced for each gene pathway were excluded from the analysis for the respective pathway. Additional details regarding NGS and genes and pathways of interest are provided in the Supplementary material. Patients included those treated at Johns Hopkins Hospital and Ghent University, as well as those enrolled in the STOMP [2] and ORIOLE [3] clinical trials. Metachronous omCSPC was defined as up to five lesions detected on CIM (CT/radionuclide bone scan) or AMIM (PSMA, 11C-choline, or 18F-fluciclovine PET) following definitive treatment of the prostate. Patients were retrospectively categorized as having CIM-omCSPC if they had metastases detected via CIM, or AMIM-omCSPC if they had lesions detected on AMIM that were not detectable on CIM.

The primary endpoint of interest was clinical and genomic differences between CIM-omCSPC and AMIM-omCSPC. Parameters were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test and Pearson’s χ2 test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Our secondary endpoints included overall survival (OS), defined from time of initial localized prostate cancer to death from any cause, and time of oligometastasis to death from any cause censored at last follow-up. Survival analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier method and were compared using a log-rank test. A multivariable Cox regression model was built using variables selected a priori. For all analyses, p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS v28.

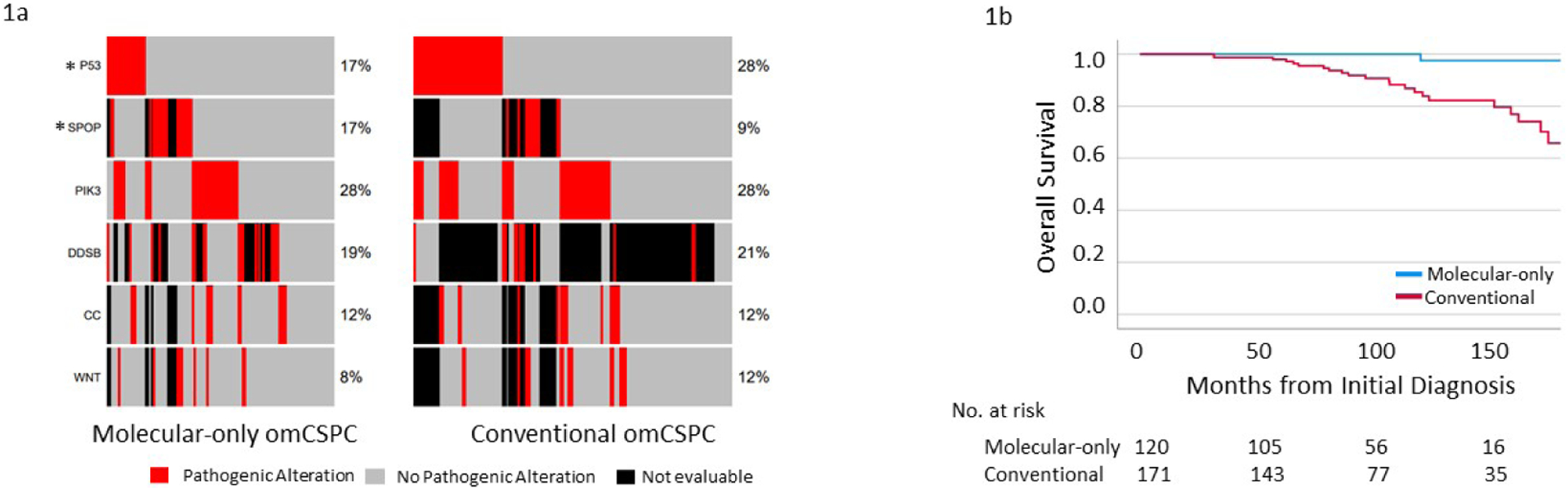

A total of 295 patients with metachronous omCSPC who underwent NGS were included in our analysis, including 123 with AMIM-omCSPC (42%) and 172 with CIM-omCSPC (58%). The median follow-up after diagnosis of localized prostate cancer for patients who survived was 92.8 mo. The time from initial prostate cancer diagnosis to oligometastatic recurrence was similar for AMIM-omCSPC and CIM-omCSPC (52.0 vs 49.2 mo; p = 0.5). Patients with CIM-omCSPC had higher Gleason grade group (p = 0.032), had higher median PSA at omCSPC (8.0 vs 1.7 ng/ml; p < 0.001), and were more likely to receive androgen deprivation therapy (ADT; 52% vs 36%; p = 0.005), but were less likely to present with pelvic lymph node–only disease (24% vs 40%; p = 0.005) or to receive MDT (37% vs 79%; p < 0.001; Table 1). Evaluation of pathogenic DNA mutations identified significantly more TP53 mutations (28% vs 17%; p = 0.030) and fewer SPOP mutations (17% vs 8.6%; p = 0.049) in the CIM-omCSPC versus the AMIM-omCSPC group (Fig. 1A). A complete list of all pathogenic alterations is provided in Supplementary Table 1. Finally, patients with CIM-omCSPC experienced significantly worse OS from localized disease according to multivariable Cox regression (hazard ratio 0.12, 95% confidence interval 0.03–0.55; p = 0.006; Supplementary Table 2) with 10-yr OS of 85% for CIM-omCSPC versus 100% for AMIM-omCSPC (p < 0.001; Fig. 1B). Similarly, patients with CIM-omCSPC experienced worse OS from the time of oligometastasis (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1).

Table 1 –

Baseline characteristics stratified by detection method

| Parameter | AMIM (n = 123) | CIM (n = 172) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median initial PSA, ng/ml (IQR) | 7.5 (5.0–13.7) | 7.5 (5.0–13.8) | 0.8 |

| ISUP Gleason grade group, n (%) | 0.032 | ||

| Grade group 1 | 6 (4.9) | 8 (4.7) | |

| Grade group 2 | 35 (29) | 21 (12) | |

| Grade group 3 | 31 (25) | 42 (24) | |

| Grade group 4 | 8 (6.5) | 29 (17) | |

| Grade group 5 | 43 (35) | 71 (41) | |

| Median time to oligometastasis, mo (IQR) | 52.0 (29.3–81.9) | 49.2 (24.2–81.2) | 0.5 |

| Median PSA at oligometastasis, ng/ml (IQR) | 1.7 (0.8–5.6) | 8.0 (2.5–15.9) | <0.001 |

| Median age at oligometastasis, yr (IQR) | 68.0 (63.0–72.0) | 66.8 (62.0–71.3) | 0.6 |

| Number of lesions, n (%) | 0.5 | ||

| 1 lesion | 61 (50) | 78 (45) | |

| 2 lesions | 32 (26) | 53 (31) | |

| 3 lesions | 22 (18) | 23 (13) | |

| 4 lesions | 7 (5.7) | 11 (6.4) | |

| 5 lesions | 1 (0.8) | 7 (4.1) | |

| Metastasis in pelvic LNs only, n (%) | 49 (40) | 42 (24) | 0.005 |

| Lung metastasis, n (%) | 2 (1.6) | 6 (3.5) | 0.3 |

| Tissue sequenced, n (%) | 0.12 | ||

| Primary tumor | 116 (94) | 145 (84) | |

| Pelvic LNs | 0 (0.0) | 5 (2.9) | |

| Distant metastasis | 3 (2.4) | 6 (3.5) | |

| Data unavailable | 4 (3.3) | 15 (8.7) | |

| Initial oligometastasis management, n (%) | |||

| Androgen deprivation therapy | 44 (36) | 90 (52) | 0.005 |

| Metastasis-directed therapy | 97 (79) | 63 (37) | <0.001 |

| Observation | 23 (19) | 38 (22) | 0.5 |

AMIM = advanced molecular imaging; CIM = conventional imaging; IQR = interquartile range; ISUP = International Society of Urological Pathology; LNs = lymph nodes; PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

Fig. 1 –

(A) Oncoplot demonstrating the mutation frequency for prostate cancer–relevant genes and pathways for oligometastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (omCSPC) detected via advanced molecular imaging alone versus conventional imaging. (B) Kaplan-Meier curves of overall survival from the time of initial diagnosis for omCSPC detected via advanced molecular-only imaging versus conventional imaging. * p < 0.05.

To the best of our knowledge, this report provides the first evidence that patients with metachronous CIM-omCSPC have more biologically aggressive disease, as indicated by TP53 enrichment, and experience worse clinical outcomes than patients with AMIM-omCSPC. These results are concordant with work by Deek et al [4] demonstrating an increase in mutation frequency for cancer driver genes with increasing amount of metastatic disease. Second, we demonstrated that AMIM-omCSPC is associated with better OS from both the time of oligometastasis and the time of initial localized prostate cancer, indicating that this represents a more indolent disease state as opposed to simply earlier detection of disease.

Incorporation of AMIM for guiding treatment decisions is controversial and has implications for ongoing clinical trials in prostate cancer [5,6]. Specifically, several randomized clinical trials in mCSPC have established a standard of care that is based on CIM-defined disease volume, and it is uncertain whether these data apply to the AMIM setting [7,8]. Prior MDT studies demonstrated that PSMA PET-guided therapy is associated with a delay in ADT initiation: the hypothesis is that this delay is because of better detection and targeting of occult metastatic disease [9]. Given the data presented here, it is unclear whether PSMA PET-guided MDT improves outcomes via detection of preferentially more indolent disease versus targeting of occult disease. This underscores the importance of further evidence on AMIM before its routine use for guiding treatment decisions such as radiation to the primary prostate tumor or use of docetaxel, as extrapolation from CIM data may be misleading [10]. Our findings are particularly important for ongoing and planned clinical trials in omCSPC (eg, NCT04037358, NCT05053152, and NCT04423211).

Our study has several limitations. First, although all patients had metachronous omCSPC, there was significant heterogeneity in how these patients were managed: approaches included observation, antiandrogen monotherapy, MDT monotherapy, and combination therapy, with notable differences in ADT and MDT rates between the groups. Although we tried to correct for these treatment differences in multivariable Cox regression, they may still have biased the survival results. This is particularly important, as our CIM-omCSPC cohort was more likely to receive ADT but had higher rates of TP53 and lower rates of SPOP mutations, which have been associated with ADT resistance and sensitivity, respectively. This imbalance of an ADT-resistant (TP53 mutant) phenotype in the group with a higher proportion of ADT use may have driven these worse clinical outcomes that cannot be fully accounted for in the present analysis Moreover, only a small proportion of patients received second-generation hormonal therapies. Second, patients with AMIM-omCSPC presented with lower PSA, meaning their metastatic disease was probably identified sooner with imaging than it otherwise would have been, leading to a potential leadtime bias. Importantly, however, if our findings were purely a result of leadtime bias, there should not be a difference in OS from the time of initial diagnosis of localized disease, as we observed here. Third, not all patients with CIM-omCSPC underwent AMIM, so we are unable to report on whether these patients had oligometastatic or polymetastatic disease on AMIM. Finally, genomic profiling was performed by multiple vendors, which may have affected how pathogenic mutations were determined and limits our ability to compare other known important genomic features such as tumor mutation burden and copy number alterations.

This is the first report on clinical and biological differences between AMIM-omCSPC and CIM-omCSPC. Patients with AMIM-omCSPC had fewer TP53 mutations and experienced better OS than patients with CIM-omCSPC. Importantly, this difference in OS is observed both from initial diagnosis of localized prostate cancer and from the time of oligometastasis, suggesting that AMIM-omCSPC may represent more indolent disease rather than a result of a leadtime bias. The presence of CIM-detected lesions should be considered when evaluating upcoming clinical trials using AMIM for staging.

Supplementary Material

Financial disclosures:

Phuoc T. Tran certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: Nicolaas Lumen has received research funding from Bayer and Janssen. Daniel Y. Song is a consultant for Isoray and BioProtect, and has received research funding from Candel Therapeutics and BioProtect. Kenneth Pienta has a leadership role with CUE Biopharma and Keystone Biopharma, has stocks/ownership interests in CUE Biopharma, Keystone Biopharma, Medsyn Biopharma, and Oncopia Therapeutics; has a consulting role for Akrevia Therapeutics, CUE Biopharma, and GloriousMed Technology; and has received research funding from Progenics. Felix Y. Feng has stocks/ownership interests in Artera; has a consulting role for Astellas Pharma, Bayer, BlueStar Genomics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Exact Sciences, Foundation Medicine, Janssen Biotech, Myovant Sciences, Novartis, Roivant, SerImmune, and Varian Medical Systems; and has received research funding from Zenith Epigenetics. Steven Joniau has a consulting role for Janssen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, and Astellas Pharma; and has received research funding from Janssen, Astellas Pharma, Ipsen, Bayer, and Ferring. Tamara Lotan has a consulting role for Janssen and has received research funding from Ventana Medical Systems, DeepBio, and AIRA Matrix. Ana Kiess has received research funding from Novartis, Merck, and Bayer. Martin Pomper has a leadership role with Precision Molecular; has stocks/ownership interests in D&D Pharmatech and PlenaryAI; has a consulting role for Jubilant Biosys, Precision Molecular, Progenics, and Reflexion Medical; has received research funding from Precision Molecular, Roche, and Sanofi; and has intellectual property interests in D&D Pharmatech and Progenics. Christopher Sweeney has stocks/ownership interests in Leuchemix; has a consulting role for Sanofi, Janssen, Astellas Pharma, Bayer, Genentech, Pfizer, and Lilly; has received research funding from Janssen Biotech, Astellas Pharma, Sanofi, Bayer, Sotio, and Dendreon; and has intellectual property interests in Leuchemix and Exelixis. Piet Ost has a consulting role for Janssen-Cilag, Bayer, Astellas Pharma, Curium Pharma, Telix Pharmaceuticals, and Novartis; and has received research funding from Varian Medical Systems and Bayer. Phuoc T. Tran has received honoraria from Reflexion Medical; has a consulting role for Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Dendreon, Janssen, Myovant Sciences, Noxopharm, Reflexion Medical, Regeneron, and Bayer Healthcare; and has received research funding from Astellas Pharma, Bayer Health, and Reflexion Medical. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor:

Phuoc T. Tran was funded by an anonymous donor, the Movember Foundation-Distinguished Gentlemen’s Ride-Prostate Cancer Foundation, the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (U01CA212007, U01CA231776, and U54CA273956), and the US Department of Defense (W81XWH-21-1-0296). The sponsors played no direct role in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Deek MP, Van der Eecken K, Sutera P, et al. Long-term outcomes and genetic predictors of response to metastasis-directed therapy versus observation in oligometastatic prostate cancer: analysis of STOMP and ORIOLE trials. J Clin Oncol 2022;40:3377–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ost P, Reynders D, Decaestecker K, et al. Surveillance or metastasis-directed therapy for oligometastatic prostate cancer recurrence (STOMP): five-year results of a randomized phase II trial. J Clin Oncol 2020;38(6 Suppl):10. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phillips R, Shi WY, Deek M, et al. Outcomes of observation vs stereotactic ablative radiation for oligometastatic prostate cancer: the ORIOLE phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2020;6:650–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deek MP, Van der Eecken K, Phillips R, et al. The mutational landscape of metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer: the spectrum theory revisited. Eur Urol 2021;80:632–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillessen S, Armstrong A, Attard G, et al. Management of patients with advanced prostate cancer: report from the Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference 2021. Eur Urol 2022;82:115–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schöder H, Hope TA, Knopp M, et al. Considerations on integrating prostate-specific membrane antigen positron emission tomography imaging into clinical prostate cancer trials by National Clinical Trials Network Cooperative Groups. J Clin Oncol 2022;40:1500–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kyriakopoulos CE, Chen YH, Carducci MA, et al. Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: long-term survival analysis of the randomized phase III E3805 CHAARTED trial. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:1080–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis ID, Martin AJ, Stockler MR, et al. Enzalutamide with standard first-line therapy in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2019;381:121–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mazzola R, Francolini G, Triggiani L, et al. Metastasis-directed therapy (SBRT) guided by PET-CT 18F-choline versus PET-CT 68Ga-PSMA in castration-sensitive oligorecurrent prostate cancer: a comparative analysis of effectiveness. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2021;19:230–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sundahl N, Gillessen S, Sweeney C, Ost P. When what you see is not always what you get: raising the bar of evidence for new diagnostic imaging modalities. Eur Urol 2021;79:565–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.