Summary

Background

Little is known regarding the mental health impact of having a significant person (family member and/or close friend) with COVID-19 of different severity.

Methods

The study included five prospective cohorts from four countries (Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and the UK) with self-reported data on COVID-19 and symptoms of depression and anxiety during March 2020–March 2022. We calculated prevalence ratios (PR) of depression and anxiety in relation to having a significant person with COVID-19 and performed a longitudinal analysis in the Swedish cohort to describe temporal patterns.

Findings

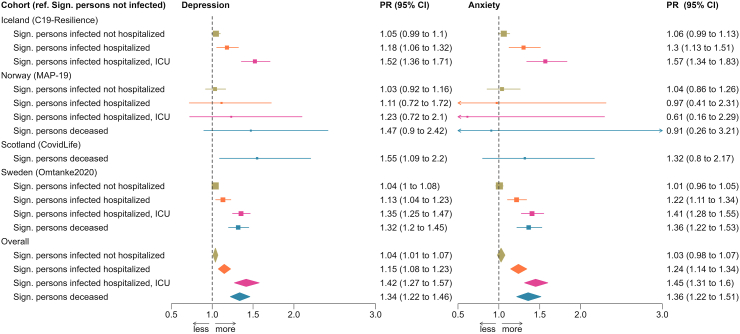

162,237 and 168,783 individuals were included in the analysis of depression and anxiety, respectively, of whom 24,718 and 27,003 reported a significant person with COVID-19. Overall, the PR was 1.07 (95% CI: 1.05–1.10) for depression and 1.08 (95% CI: 1.03–1.13) for anxiety in relation to having a significant person with COVID-19. The respective PRs for depression and anxiety were 1.15 (95% CI: 1.08–1.23) and 1.24 (95% CI: 1.14–1.34) if the patient was hospitalized, 1.42 (95% CI: 1.27–1.57) and 1.45 (95% CI: 1.31–1.60) if the patient was ICU-admitted, and 1.34 (95% CI: 1.22–1.46) and 1.36 (95% CI: 1.22–1.51) if the patient died. Individuals with a significant person with hospitalized, ICU-admitted, or fatal COVID-19 showed elevated prevalence of depression and anxiety during the entire year after the COVID-19 diagnosis.

Interpretation

Family members and close friends of critically ill COVID-19 patients show persistently elevated prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms.

Funding

This study was primarily supported by NordForsk (COVIDMENT, 105668) and Horizon 2020 (CoMorMent, 847776).

Keywords: COVID-19, Significant person, Depression, Anxiety, Cross-country study

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

A substantial mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been well documented, especially for individuals directly exposed to the disease (i.e., patients with COVID-19). Relatively little is however known regarding the mental health impact of having a significant person (family member and/or close friend) with COVID-19 of different severity. We searched PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) using combination of the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) term “severe acute respiratory syndrome related coronavirus” and the entry terms “COVID-19”, “mental health”, “depression”, “anxiety”, “family member”, and “close friends” in title or abstract until June 20th, 2023. No restriction on language or year of publication was applied. We identified 16 original research articles, which all showed an increased burden of mental ill health among the family members of COVID-19 patients. These studies are however limited methodologically as they were either case studies or specific in setting (e.g., studying family members of ICU-admitted COVID-19 patients), had a relatively small sample size, or used cross-sectional data. One study examined friends, in addition to family members. Few studies have to date used longitudinal data or examined the burden of mental ill health by different severity of COVID-19.

Added value of this study

We leveraged longitudinal data collected from 160,000 individuals in four European countries during a period of 22 months of the COVID-19 pandemic (June 2020–March 2022) and found an elevated risk of severe depressive and anxiety symptoms among individuals that had a family member or close friend diagnosed with COVID-19. We found that the risk increase of depressive and anxiety symptoms was primarily attributed to having a family member or close friend with severe COVID-19 (i.e., hospitalised, ICU-admitted, or deceased) and that the risk increase persisted during the first year after diagnosis of the patient with COVID-19. The novelty of this study lies in the inclusion of data from four countries with varying burden of the pandemic as well as different strategies in mitigating the ramifications of the pandemic and the focus on analysing acute disease severity and temporal pattern of the mental health impact.

Implications of all the available evidence

These findings motivate enhanced surveillance of family members and close friends of patients suffering severe COVID-19, or the disease of any future pandemics.

Introduction

WHO declared end to Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) global health emergency on May 5th, 2023. However, the health impact of the pandemic will inevitably continue. While most studies have focused on physical and mental health outcomes among individuals directly exposed to the pandemic, especially patients with COVID-191, 2, 3, 4 and front-line healthcare workers,5,6 families of individuals with COVID-19 might be a high-risk group for mental health problems specifically.2 Indeed, having a family member with SARS-CoV-2 infection has previously been associated with severe psychological distress7 and multiple studies have shown that having a relative suspected of or diagnosed with COVID-19 is associated with an increased risk of mental illness, including depression, anxiety, and stress-related disorders.1,2,8, 9, 10, 11

Individuals who lost a family member due to COVID-19 might be the most vulnerable.2 Bereavement has been consistently shown to increase the risk of mental illness,12,13 including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)14 and complicated grief.9,15 Bereavement due to COVID-19 might be especially complicated, because the affected have limited possibilities to bid farewell to their loved ones, gather for mourning ceremonies, or receive support in their grief.9 Verdery et al. created a prediction model indicating that every COVID-19-related death would leave approximately nine bereaved.16 Given the accumulated number of deaths due to COVID-19 to date, this would mean over 60 million COVID-19 bereaved individuals globally.

Starting in spring 2020, we leveraged five prospective cohort studies across four countries (Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and the UK) within the COVIDMENT consortium,17 with the aim to examine the prevalence of symptoms of depression and anxiety among people whose family members or close friends (hereafter referred to as “significant persons”) contracted COVID-19. We studied close friends, in addition to family members, as relatively little data exist currently on how having a close friend with COVID-19 affects mental health. We focused on analyzing symptoms of depression and anxiety by the severity of COVID-19 in the significant person, hypothesizing a dose–response relationship between severity of COVID-19 and prevalence of mental health symptoms.

Methods

Study design

The COVIDMENT network includes multiple cohort studies, which have since March 2020 collected self-reported data on COVID-19 as well as various physical and mental health measures, using semi-harmonized questionnaires.17 The following cohorts included questions on significant persons: the Icelandic COVID-19 National Resilience Cohort (C-19 Resilience), the Norwegian COVID-19 Mental Health and Adherence Study (MAP-19), the Norwegian Mother, Father, and Child Cohort Study (MoBa), the Swedish Omtanke2020 Study, and the UK-based CovidLife Study. We analyzed data collected from March 2020 to March 2022 in each of the five cohorts and performed a meta-analysis of the cohort-specific results to assess the association between having a significant person with COVID-19 and prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms. Data were collected once in MAP-19 (winter 2021/2022), twice in MoBa (both in summer 2020), thrice in C-19 Resilience (spring/summer 2020, winter 2020/2021, and summer 2021) and CovidLife (spring 2020, summer 2020, and winter 2020/2021), and up to 13 times in Omtanke2020 (monthly from June 2020 to February 2022), during the study period. Accordingly, we had repeated measures of all variables related to COVID-19 of both the participants and their significant persons, as well as depressive and anxiety symptoms of the participants.

We defined the cohort participants as exposed if they reported that a significant person had been diagnosed with COVID-19. There are also separate questions on hospitalization and admission to the ICU for COVID-19 in C-19 Resilience, MAP-19, and Omtanke2020 as well as death due to COVID-19 in MAP-19, Omtanke2020, and CovidLife. We accordingly created a categorical variable and classified the participants, whenever possible, as having “no significant person diagnosed”, “a significant person diagnosed but not hospitalized”, “a significant person diagnosed and hospitalized”, “a significant person diagnosed with ICU admission”, and “a significant person deceased due to COVID-19”, hypothesizing a greater mental health impact in relation to having a significant person with severe COVID-19, especially a COVID-19 that led to death, compared to having a significant person with mild COVID-19. As one's own diagnosis of COVID-19 might influence how a person experiences having a significant person with COVID-19, we similarly ascertained the COVID-19 status for the cohort participants themselves.

We employed two validated instruments to measure symptoms of depression and anxiety, namely the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire18 (PHQ-9) for depressive symptoms and the 7-item General Anxiety Disorder19 (GAD-7) for anxiety symptoms in the last two weeks before responding to a survey. On both instruments, a cut-off of ≥10 was used to define severe symptom load.18,19 We excluded participants who did not complete all items of the PHQ-9 and the GAD-7. Except for Omtanke2020, the study cohorts had very little item-level missingness. In Omtanke2020, if at least 80% of the items were completed, we imputed the missing items to obtain the total scores.20 Our final analysis included 162,237 participants with data on depressive symptoms and 168,783 participants with data on anxiety symptoms. Among these participants, 24,718 (15.2%) and 27,003 (16.0%) reported having a significant person with COVID-19, respectively.

In addition to the COVID-19 status of the participants themselves, we included as covariables age at enrolment (i.e., baseline), sex or gender (male or female), educational level (“no formal education”, “compulsory, upper secondary, vocational, or other education”, “Bachelor's/diploma university degree”, or “Master's or PhD”), type of enrolment (by invitation or self-recruitment), relationship status (in a relationship or single), history of psychiatric disorders (yes or no), somatic comorbidities (no comorbidity, one comorbidity, two comorbidities, or >2 comorbidities), heavy drinking (yes or no, defined as 4 drinks consumed in one sitting for women or 5 drinks for men), and calendar period of enrolment. Some of the cohorts recruited participants via invitation to previously existing studies, some recruited participants through self-enrolment, whereas others used both. We therefore used type of enrolment as a covariable because participants enrolled by invitation differ from self-enrolled participants.21 Further, as body mass index (BMI)22,23 and smoking23,24 have been associated with both COVID-19 and mental health, we also included BMI (<25, 25–30, or >30 kg/m2) and smoking (no smoker, former smoker, or current smoker) as two additional covariables. We handled the missingness in categorical covariables using a separate category “missing”. Apart from age and sex, all other information was self-reported.

This study was approved by national or regional ethics review committees in Iceland (NBC no. 20–073, 21–071), Norway (REK 14140 and 125510), Sweden (DNR 2020-01785), and the UK (20/ES/0021). All participants provided written informed consent.

Statistical analysis

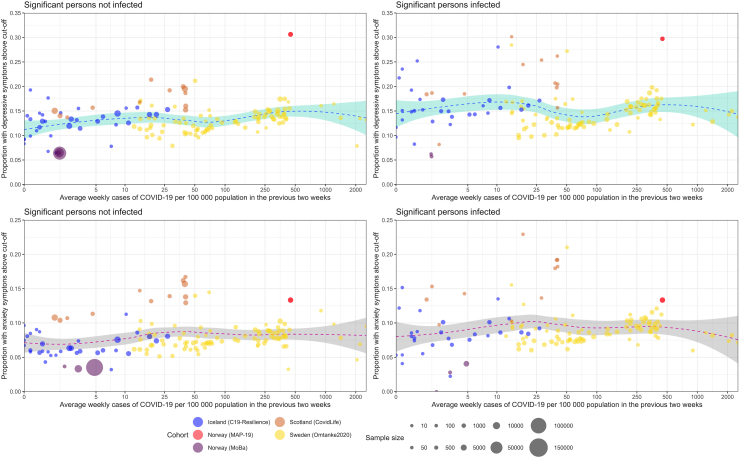

First, to appraise the association between the pandemic burden and the risk of depression and anxiety, we estimated the prevalence of severe depressive and anxiety symptoms among the cohort participants during the different calendar weeks of the study period when the respective cohort had an ongoing data collection against the burden of pandemic in the population (i.e., incidence of COVID-19 during the preceding two weeks of a specific calendar week in the corresponding country). The incidence of COVID-19 was obtained from government agencies (see Supplementary information). We calculated the weekly prevalence among participants with or without a significant person with COVID-19 separately, with marginal means using the EMMEANS R package,25 and fitted a temporal trend of the prevalence estimates using a local regression (LOESS) model.26

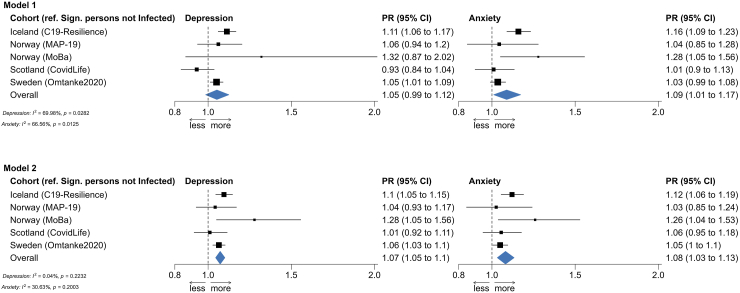

Second, to assess the association between having a significant person with COVID-19 and risk of depression and anxiety, we calculated the prevalence ratio (PR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) of severe depressive and anxiety symptoms in relation to having a significant person with COVID-19 reported in the same survey, using the robust (modified) Poisson model with adjustment for intra-individual correlation for repeated measurements. In Model 1, we adjusted for age, sex or gender, COVID-19 status of the participant, and time of data collection (except for MAP-19 where data were collected only once). In Model 2, we additionally adjusted for educational level, type of recruitment, marital status, history of psychiatric disorders, somatic comorbidities, heavy drinking, BMI, and smoking. We calculated PR in relation to having a significant person with COVID-19 as well as by COVID-19 severity of the significant person. We first performed the analyses in each cohort and then performed a random-effects model meta-analysis of the aggregated data from each cohort to estimate the overall PR, using the R package METAFOR.27 We used I2 statistic to measure the heterogeneity between cohorts.

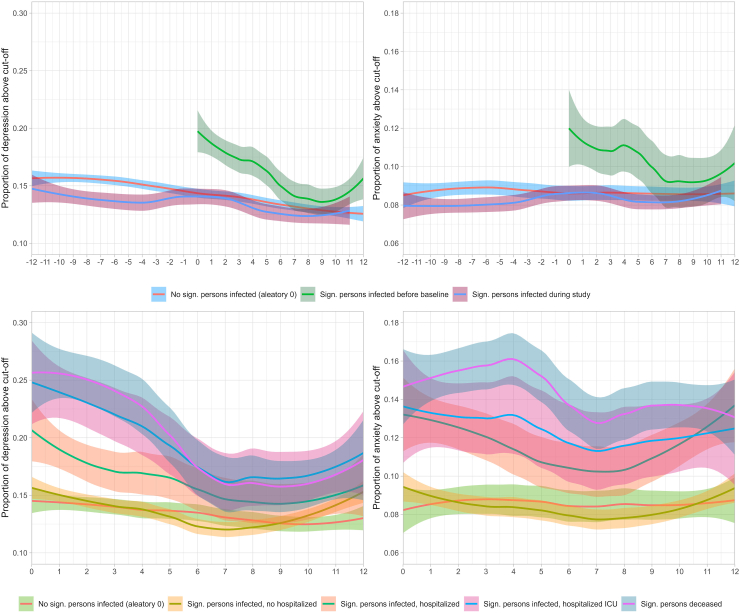

Finally, to understand the temporal relationship between having a significant person with COVID-19 and risk of depression and anxiety, we performed a separate analysis in Omtanke2020 with 13 monthly data collections. In this longitudinal analysis, for participants reporting a significant person diagnosed with COVID-19 before enrolment to the study, we defined time 0 as the month when the participant was enrolled. For participants reporting a significant person diagnosed with COVID-19 after enrolment to the study (i.e., during the study), we defined time 0 as the month when the significant person was diagnosed. Timing of COVID-19 diagnosis in relation to enrolment was considered in this analysis to assess potential selection bias, as individuals having a significant person with COVID-19 might be more inclined to participate in a COVID-19 research project as well as might demonstrate higher prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms than others. For participants not reporting a significant person with COVID-19, we selected time 0 randomly during the study period to imitate that COVID-19 could have occurred to a significant person of this group any time during the study. Choosing a random time 0 also accounts for differences in seasons and pandemic waves. For the first group, we calculated the prevalence of severe depressive and anxiety symptoms up to 12 months after time 0. For the latter two groups, we calculated the prevalence of severe depressive and anxiety symptoms up to 12 months before and up to 12 months after time 0. Among participants reporting a significant person with COVID-19, we also calculated the prevalence by disease severity (i.e., diagnosed but not hospitalized, hospitalized, ICU admitted, or deceased). The calculations were adjusted for age, sex or gender, COVID-19 status of the participant, time of data collection, and type of recruitment. The temporal trend of prevalence estimates was also smoothed using LOESS model.

Role of the funding source

The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1 show the characteristics of the study participants. The mean age at enrolment ranged from 40.0 (MAP-19) to 56.9 (CovidLife), and proportion of female ranged from 60.3% (MoBa) to 81.5% (Omtanke2020). The percentage of reporting a significant person with COVID-19 ranged from 15.0% (C-19 Resilience) to 55.2% (Omtanke2020). Participants reporting a significant person with COVID-19 showed slightly higher (bi-)weekly prevalence of depression (top) and anxiety (bottom), compared with participants not reporting such (Fig. 1). The prevalence was not however strongly related to the burden of pandemic in the population (measured with the incidence of new COVID-19 cases), regardless of the severity of COVID-19 in the significant person, evidenced by the relative evenness of the curves (Supplementary Figure S1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants by cohort.

| Iceland |

Norway |

Sweden Omtanke2020 | UK CovidLife | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-19 Resilience | MoBac |

MAP-19 | ||||

| Depression | Anxiety | |||||

| Characteristics | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| Total (N) | 22,898 | 91,950 | 98,496 | 2898 | 27,752 | 16,739 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 16,006 (69.9%) | 55,411 (60.3%) | 58,795 (59.7%) | 2326 (80.3%) | 22,614 (81.5%) | 11,172 (66.7%) |

| Male | 6892 (30.1%) | 36,539 (39.7%) | 39,701 (40.3%) | 572 (19.7%) | 5138 (18.5%) | 5567 (33.3%) |

| Age | ||||||

| Mean age (SD) | 54.4 (14.3) | 47.0 (5.2) | 47.0 (5.3) | 40.0 (14.0) | 48.7 (15.7) | 56.9 (14.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 56.0 (20.0) | 47.0 (46.0) | 47.0 (46.0) | 37.0 (21.0) | 49.0 (25.0) | 59.0 (19.0) |

| 18–29 years | 1487 (6.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 837 (28.9%) | 3809 (13.7%) | 805 (4.8%) |

| 30–39 years | 2261 (9.9%) | 5944 (6.5%) | 6742 (6.8%) | 766 (26.4%) | 5069 (18.3%) | 1551 (9.3%) |

| 40–49 years | 4075 (17.8%) | 56,000 (60.9%) | 60,002 (60.9%) | 565 (19.5%) | 5308 (19.1%) | 2298 (13.7%) |

| 50–59 years | 5879 (25.7%) | 25,578 (27.8%) | 26,855 (27.3%) | 407 (14.0%) | 5961 (21.5%) | 3725 (22.2%) |

| 60–69 years | 5885 (25.7%) | 1209 (1.3%) | 1285 (1.3%) | 237 (8.2%) | 4417 (15.9%) | 5203 (31.1%) |

| 70 years+ | 3311 (14.4%) | 57 (0.1%) | 67 (0.1%) | 86 (3.0%) | 3188 (11.5%) | 3157 (18.9%) |

| Missing | – | 3162 (3.4%) | 3545 (3.6%) | – | – | – |

| Education | ||||||

| Compulsory | 3297 (14.4%) | 1673 (1.8%) | 1894 (1.9%) | 131 (4.5%) | a | 1401 (8.4%) |

| Upper secondary, vocational or other | 7095 (31.0%) | 25,849 (28.1%) | 28,249 (28.7%) | 1001 (34.5%) | a | 5741 (34.3%) |

| Bachelor's/diploma university degree | 7179 (31.3%) | 32,248 (35.1%) | 34,169 (34.7%) | 1766 (60.9%) | a | 3973 (23.7%) |

| Master's or PhD | 5167 (22.6%) | 26,816 (29.2%) | 28,271 (28.7%) | – | a | 4298 (25.7%) |

| No formal education | – | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | – | a | 338 (2.0%) |

| Missing | 160 (0.7%) | 5364 (5.8%) | 5913 (6.0%) | – | 27,752 (100%) | 988 (5.9%) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| In a relationship | 17,522 (76.5%) | – | – | 1908 (65.8%) | 20,106 (72.4%) | 12,934 (77.3%) |

| Single | 5276 (23.1%) | – | – | 990 (34.2%) | 7508 (27.1%) | 3799 (22.7%) |

| Missing | 100 (0.4%) | – | – | – | 138 (0.5%) | 6 (<0.1%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||

| <25, Normal or low weight | 6629 (28.9%) | 30,066 (32.7%) | 30,812 (31.2%) | 1014 (35.0%) | 14,395 (51.9%) | 6534 (39.0%) |

| 25–30, Overweight | 8799 (38.4%) | 25,530 (27.8%) | 26,171 (26.6%) | 1012 (34.9%) | 8201 (29.5%) | 5895 (35.2%) |

| >30, Obese | 6884 (30.1%) | 11,697 (12.7%) | 11,990 (12.2%) | 509 (17.6%) | 3769 (13.6%) | 4215 (25.2%) |

| Missing | 586 (2.6%) | 24,657 (26.8%) | 29,523 (30.0%) | 363 (12.5%) | 1387 (5.0%) | 95 (0.6%) |

| Current smoking | ||||||

| No, never | 10,462 (45.7%) | 80,338 (87.3%) | 79,123 (80.3%) | – | 14,297 (51.5%) | 10,236 (61.2%) |

| No, former smoker | 8859 (38.7%) | – | – | – | 8459 (30.5%) | 5122 (30.6%) |

| Yes, currently | 3377 (14.7%) | 8417 (9.2%) | 8133 (8.3%) | – | 4645 (16.7%) | 1178 (7.0%) |

| Missing | 200 (0.9%) | 3195 (3.5%) | 11 240 (11.4%) | – | 351 (1.3%) | 203 (1.2%) |

| Heavy drinking | ||||||

| Yes | 5140 (22.5%) | – | – | – | 7269 (26.2%) | 13,126 (78.4%) |

| No | 17,519 (76.5%) | – | – | – | 14,950 (53.9%) | 3412 (20.4%) |

| Missing | 239 (1.0%) | 91,950 (100%) | 98,496 (100%) | – | 5533 (19.9%) | 201 (1.2%) |

| History of psychiatric disorders | ||||||

| Yes | 6501 (28.4%) | 14,563 (15.8%) | 15,642 (15.9%) | 731 (25.2%) | 9440 (34.0%) | 5386 (32.2%) |

| No | 16,064 (70.2%) | 74,135 (80.7%) | 79,213 (80.4%) | 2167 (74.8%) | 17,770 (64.0%) | 11,251 (67.2%) |

| Missing | 333 (1.4%) | 3252 (3.5%) | 3641 (3.7%) | – | 542 (2.0%) | 102 (0.6%) |

| Somatic comorbidities | ||||||

| No comorbidity | 13,419 (58.6%) | 73,323 (79.8%) | 78,358 (79.6%) | 2054 (70.8%) | 18,144 (65.4%) | 9018 (53.9%) |

| One comorbidity | 6561 (28.7%) | 13,543 (14.7%) | 14,540 (14.7%) | 844 (29.2%) | 6227 (22.4%) | 4826 (28.8%) |

| Two comorbidities | 2107 (9.2%) | 1680 (1.8%) | 1797 (1.8%) | – | 1649 (5.9%) | 1909 (11.4%) |

| >Two comorbidities | 642 (2.8%) | 241 (0.3%) | 255 (0.3%) | – | 554 (2.0%) | 944 (5.6%) |

| Missing | 169 (0.7%) | 3163 (3.4%) | 3546 (3.6%) | – | 1178 (4.3%) | 42 (0.3%) |

| Recruitment period (baseline) | ||||||

| April–June 2020 | 21,448 (93.7%) | 91,950 (100%) | 98,496 (100%) | – | 1441 (5.2%) | 16,739 (100%) |

| July–September 2020 | 261 (1.1%) | – | – | – | 10,215 (36.8%) | – |

| October–December 2020 | 511 (2.2%) | – | – | – | 10,768 (38.8%) | – |

| January–March 2021 | 636 (2.8%) | – | – | – | 1966 (7.1%) | – |

| April–June 2021 | 42 (0.2%) | – | – | – | 3357 (12.1%) | – |

| July–September 2021 | – | – | – | – | 5 (<0.1%) | – |

| October–December 2021 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| January–March 2022 | – | – | – | 2898 (100%) | – | – |

| Recruitment type | ||||||

| Social media | – | – | – | 2898 (100%) | 11,359 (40.9%) | – |

| Personal invitation from other cohort | – | 91,950 (100%) | 98,496 (100%) | – | 12 057 (43.5%) | 4609 (27.5%) |

| Missing | – | – | – | – | 4336 (15.6%) | 12,130 (72.5%) |

| Participant's COVID-19 status | ||||||

| Infected before baseline | 1017 (4.4%) | 198 (0.2%) | 194 (0.2%) | – | 1435 (5.2%) | 1683 (10.0%) |

| Infected during study | 183 (0.8%) | 9 (<0.1%) | 948 (1.0%) | 251 (8.7%) | 12,285 (44.2%) | 796 (4.8%) |

| Not infected | 21,653 (94.6%) | 91,743 (99.8%) | 97,354 (98.8%) | 2647 (91.3%) | 14,032 (50.5%) | 14,146 (84.5%) |

| Missing | – | – | – | – | – | 114 (0.7%) |

| Participant's COVID-19 severity | ||||||

| Not infected | 21,881 (95.6%) | 91,743 (99.8%) | 97,354 (98.9%) | – | 14,032 (50.5%) | 14,146 (84.5%) |

| Infected but not hospitalized | 941 (4.1%) | 184 (0.2%) | 212 (0.2%) | – | 13,594 (49.0%) | 2523 (15.1%) |

| Infected and hospitalized | 51 (0.2%) | 7 (<0.1%) | 8 (<0.1%) | – | 101 (0.4%) | 64 (0.4%) |

| Infected and with ICU admission | 25 (0.1%) | – | – | – | 25 (0.1%) | 3 (<0.1%) |

| Missing | – | 16 (<0.1%) | 922 (0.9%) | – | – | 3 (<0.1%) |

| SP's COVID-19 status and severity | ||||||

| Not infected | 19,452 (85.0%) | 91,540 (99.6%) | 95,801 (97.3%) | 1884 (65.0%) | 12,436 (44.8%) | 15,073 (90.0%) |

| Infected | 410 (0.4%)b | 2695 (2.7%)b | 1666 (10.0%)b | |||

| Infected but not hospitalized | 2886 (12.6%) | – | – | 964 (33.3%) | 12,683 (45.7%) | – |

| Infected and hospitalized | 299 (1.3%) | – | – | 23 (0.8%) | 1145 (4.1%) | – |

| Infected and with ICU admission | 261 (1.1%) | – | – | 12 (0.4%) | 610 (2.2%) | – |

| Deceased | – | – | – | 15 (0.5%) | 878 (3.2%) | – |

Education was not collected in Omtanke2020; marital status and heavy drinking were not collected in MoBa.

COVID-19 severity information was not collected in MoBa and CovidLife.

Depression and anxiety were measured at slightly different time points (a few weeks apart).

Fig. 1.

Depressive (top) and anxiety (bottom) symptoms and COVID-19 incidence across cohorts over the entire study period, stratified by infection of a significant person. COVID-19 incidence is defined as the average number of confirmed cases per week per 100,000 persons in the 2 weeks prior to participant's response to the survey. Dotted blue line represents trend with 95% confidence interval.

Fig. 2 shows the cohort-specific and pooled PRs of depression (left) and anxiety (right) in relation to having a significant person with COVID-19. In both Models 1 and 2, we found a statistically significant positive association between having a significant person with COVID-19 and a higher prevalence of severe depressive and anxiety symptoms in the pooled analyses, apart from the association for depression in Model 1. There was less heterogeneity in Model 2 than Model 1 (i.e., I2 = 70% for depression and 67% for anxiety in Model 1 and <1% for depression and 31% for anxiety in Model 2). For this reason, we present analyses based on Model 2 in Fig. 3 to show the results by COVID-19 severity of the significant person. Results on Model 1 can be found in Supplementary Figure S2. Apart from the analysis of anxiety in MAP-19, a dose–response relationship was noted in both the cohort-specific analyses and the pooled analyses, namely that the associations were strongest for having a significant person admitted to the ICU, followed by having a significant person hospitalized, for COVID-19. There was however no clear difference between having a significant person admitted to the ICU and having a significant person deceased due to COVID-19. Supplementary Figures S3 and S4 show similar results after excluding MoBa, the cohort with the largest sample size, from the analyses.

Fig. 2.

Prevalence ratio (PR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of depressive (left) and anxiety (right) symptoms in relation to having a significant person with COVID-19.

Fig. 3.

Prevalence ratio (PR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of depressive (left) and anxiety (right) symptoms in relation to having a significant person with COVID-19, analysis by disease severity.

In the Omtanke2020 cohort, the prevalence of severe depressive and anxiety symptoms was much higher among participants reporting a significant person diagnosed with COVID-19 before enrolment, compared to participants not reporting such (Fig. 4, top). Further, as a general trend, the prevalence of severe depressive and anxiety symptoms continuously decreased over time among all participants (i.e., from enrolment onward among participants reporting a significant person with COVID-19 before enrolment and from 12 months before to 12 months after time 0 in the other two groups). However, the prevalence increased slightly around time 0 (i.e., time of COVID-19 diagnosis) among participants reporting a significant person with a COVID-19 diagnosed after enrolment. Looking by COVID-19 severity, participants reporting a significant person with COVID-19 without hospitalization demonstrated comparable prevalence of severe depressive and anxiety symptoms as those not reporting a significant person with COVID-19 (Fig. 4, bottom). However, those reporting a significant person hospitalized or admitted to the ICU for COVID-19, or deceased due to COVID-19, showed higher prevalence for both outcomes during the entire 12 months after the diagnosis of the significant person than those not reporting a significant person with COVID-19 or reporting a significant person with COVID-19 not requiring hospitalization. The difference was greatest immediately after COVID-19 diagnosis and decreased with time since diagnosis. Finally, there was a lower prevalence of severe depressive symptoms among participants reporting a significant person hospitalized for COVID-19, compared with those reporting a significant person admitted to the ICU or deceased due to COVID-19. No clear pattern was, however, noted for anxiety symptoms.

Fig. 4.

Time trends of the monthly prevalence of depressive (left) and anxiety (right) symptoms among individuals with or without a significant person with COVID-19 (top) and by the disease severity of COVID-19 (bottom) in the Swedish Omtanke2020 cohort.

Discussion

In a study of over 160,000 individuals from four countries in Europe, we found an elevated prevalence of severe symptom load of depression and anxiety among individuals reporting having had a significant person (i.e., family member or close friend) diagnosed with COVID-19, particularly in cases of a critical COVID-19 illness (hospitalization, ICU, or death). This result was observed in the analysis of all individual cohorts as well as in the pooled analysis of all cohorts with data from the first 22 months of the pandemic.

Our finding of a higher prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms among individuals reporting a significant person with COVID-19 is supported by the few existing studies. One study showed a considerable risk of depression, anxiety, insomnia, and acute stress among family members and friends of patients with COVID-19 during the first wave of the pandemic in China.1 Another study showed a prevalence of depression as 15.0% and of anxiety 16.3% among 153 relatives of COVID-19 patients.28 A third study showed similarly prominent levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms between isolated COVID-19 patients and their relatives.8 Our study is, to our knowledge, the first to demonstrate that the prevalence increment in mental health symptomology is proportional to the severity of COVID-19, mainly attributable to severe illness requiring inpatient or ICU care or leading to death.

We observed that individuals reporting a significant person hospitalized, admitted to the ICU, or deceased due to COVID-19 had persistently increased risk of depressive and anxiety symptoms during the first year after the diagnosis of the significant person. Family members of COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU have been reported to exhibit a higher prevalence and a slower improvement of depressive symptoms, compared to the patients themselves.29 Half of these family members reported high levels of depressive symptoms one year later if the patient had used prolonged mechanical ventilation.29 Further, symptoms of depression and anxiety did not seem to disappear even when the patients survived after ICU care.30 Other psychiatric conditions might serve as mediating factors leading to subsequent depressive and anxiety symptoms. For example, family members have been reported to demonstrate high risk of PTSD14 and complicated grief15 following death of the patient in the ICU before the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, a higher level of prolonged grief disorder has been reported among individuals bereaved due to COVID-19,9 compared to those whose loss was due to other natural causes, regardless of ICU admission.

These findings could be attributed to multiple factors, including fast transmission of the disease (i.e., no time to prepare), feelings of guilt (e.g., having potentially spread the illness to the patient), emotional shock of not being able to care or take farewell, and fear of stigmatization.10 Other factors, not necessarily related to the illness of a significant person, may also contribute to poor mental health, such as physical symptoms of COVID-1931 or post-covid syndrome32 of the participants themselves as well as varying perceptions regarding mitigating strategies enforced in the pandemic including quarantine and use of face masks.33 On the other hand, resilience, optimism, and mindfulness are protective factors for mental health.34 Loss of a significant person from a severe illness like COVID-19 might have a greater mental health impact than having a significant person who suffered but eventually recovered from the illness. The similar results noted between having a significant person admitted to ICU for COVID-19 and having a significant person deceased due to COVID-19 are therefore unexpected. Future research is needed to understand the underlying reasons, including for instance the impact of the varying recovery course of the ICU-admitted patients. Regardless, because of the extraordinarily large number of individuals deceased and the vast number of bereaved ones they left behind, bereavement due to COVID-19 has a substantial public health impact that will carry on for a long time to come.16 Continued follow-up and surveillance are therefore needed for this risk population worldwide.

Strengths of our study include the large sample size, the long study period covering almost two years of the pandemic, the use of validated measures for depression and anxiety, and the availability of longitudinal data. Another distinct strength of the study is the cross-country design with harmonized or semi-harmonized data collection, leading to the unique opportunity of cross-validating findings between countries. A limitation of the study is the self-reported data on COVID-19, depressive and anxiety symptoms, and different covariables. However, potential measurement errors due to self-report would need to be systematic between reports on COVID-19 in a significant person and own depressive and anxiety symptoms, to explain the results of the study. The different definition of significant person between the cohorts is another limitation, yet the largely similar results across cohorts alleviate this concern. As we were unable to study the effect of having multiple significant persons with COVID-19, further studies are needed to examine the role of such experience, especially in cases of multiple severe COVID-19 cases, on depression and anxiety. Further, as in all meta-analyses, the pooled results may be affected by the slight differences in multivariable adjustments of the different cohorts (e.g., lack of information on marital status and heavy drinking in MoBa). To alleviate this concern, we compared results between Model 1 that includes only the most important covariables available in all cohorts and Model 2 that includes all covariables, as well as performed a sensitivity analysis excluding MoBa. The similar results noted between Model 1 and Model 2 as well as between the main analysis and the sensitivity analysis should have allayed this concern to some extent. Finally, the study participants are all residing in European welfare states with relatively accessible health care for all, thus the findings cannot be readily generalizable to other populations.

In conclusion, people exposed to a significant person who is critically ill with COVID-19 (i.e., required hospitalization or ICU admission, or led to death) show persistent elevations in severe symptom load of depression and anxiety.

Contributors

All authors contributed to the initial discussion of the study aims and design. The cohort-specific and pooled data analyses were designed by AL, JGH, AH, CFR, IM, LL, DLM, JJ, TA, HA, OVE, UAV and FF. AL, JGH, AH, CFR, IM, LL and DLM performed all analyses. All authors participated in the interpretation of the findings and had access to the cohort-specific and pooled results, as well as the R codes used for the analysis. AL, JGH, CC, EEJ, UAV and FF performed the literature review and drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript for critical content and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

The individual-level data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to data protection laws in each participating country.

Ethical approvals

The C-19 Resilience was approved by the National Bioethics Committee (NBC no. 20–073, 21–071) as well as the National Data Protection Authority. The establishment of MoBa was based on a license from the Norwegian Data Protection Agency and approval from The Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK). The MoBa cohort is now based on regulations related to the Norwegian Health Registry Act. The current study was approved by REK (14140). MAP-19 was approved by REK (reference: 125510) and The Norwegian Centre for Research Data (reference: 802810). The Omtanke2020 Study was approved (DNR 2020-01785) by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority on 3 June 2020. The CovidLife study was reviewed and given a favourable opinion by the East of Scotland Research Ethics Committee (Reference: 20/ES/0021, AM02, AM04, AM05, AM11).

Declaration of interests

AL received a grant from the Fredrik and Ingrid Thuring Foundation. DLM is a part-time employee of Optima Partners Ltd. EMF received payment for keynote lecture from Astra Zeneca. HA received a grant from the Research Council of Norway. PFS received a grant from the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet, award D0886501) and is a consultant and shareholder Neumora Therapeutics for work not directly related to the topics of this paper. OAA received grants from NordForsk (Grant 105668) and the European Union’s Horizon2020 Research and Innovation Programme (Grant 847776; CoMorMent) for the current project and received grants from NIH NIMH, the Research Council of Norway, the South-East Regional Health Authority, Horizon2020, Stiftelsen Kristian Gerhard Jebsen, consulting fees from Biogen, Cortechs.ai and Milken, payment or honoraria from Janssen, Lundbeck and Sunovion, and reports patent Intranasal Administration, US20160310683 A1, participation on DSMB 21 board as PI, and stock options with Cortechs.ai. UAV received grants from NordForsk (Grants 138929 and 105668). FF received grants from NordForsk, the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, the Horizon2020 programme, Swedish Research Council, Swedish Cancer Society, US CDC, US NIH, and the European Research Council. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was primarily supported with grants from NordForsk (COVIDMENT, 105668; LongCOVIDMENT, 138929), the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (2022-00579), and Horizon 2020 (CoMorMent, 847776). HA was supported by the Research Council of Norway (324620). Recruitment to CovidLife (UK) was facilitated by SHARE–the Scottish Health Research Register and Biobank. SHARE is supported by NHS Research Scotland, the University of Saskatchewan, and the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2023.100733.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Shi L., Lu Z.A., Que J.Y., et al. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with mental health symptoms among the general population in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vindegaard N., Benros M.E. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:531–542. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santomauro D.F., Herrera A.M.M., Shadid J., et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398(10312):1700–1712. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson E., Sutin A.R., Daly M., Jones A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies comparing mental health before versus during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. J Affect Disord. 2022;296:567–576. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pappa S., Ntella V., Giannakas T., Giannakoulis V.G., Papoutsi E., Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Y., Scherer N., Felix L., Kuper H. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder in health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu P., Fang Y., Guan Z., et al. The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(5):302–311. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorman-Ilan S., Hertz-Palmor N., Brand-Gothelf A., et al. Anxiety and depression symptoms in COVID-19 isolated patients and in their relatives. Front Psychiatr. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.581598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisma M.C., Tamminga A., Smid G.E., Boelen P.A. Acute grief after deaths due to COVID-19, natural causes and unnatural causes: an empirical comparison. J Affect Disord. 2021;278:54–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohammadi F., Oshvandi K., Shamsaei F., Cheraghi F., Khodaveisi M., Bijani M. The mental health crises of the families of COVID-19 victims: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22(1):94. doi: 10.1186/s12875-021-01442-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landi G., Pakenham K.I., Grandi S., Tossani E. Young adult carers during the pandemic: the effects of parental illness and other ill family members on COVID-19-related and general mental health outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6):3391. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kristensen P., Weisæth L., Heir T. Bereavement and mental health after sudden and violent losses: a review. Psychiatry. 2012;75(1):76–97. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2012.75.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stroebe M., Schut H., Stroebe W. Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet. 2007;370(9603):1960–1973. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61816-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azoulay E., Pochard F., Kentish-Barnes N., et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):987–994. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kentish-Barnes N., Chaize M., Seegers V., et al. Complicated grief after death of a relative in the intensive care unit. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(5):1341–1352. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00160014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verdery A.M., Smith-Greenaway E., Margolis R., Daw J. Tracking the reach of COVID-19 kin loss with a bereavement multiplier applied to the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(30):17695–17701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2007476117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Unnarsdóttir A., Lovik A., Fawns-Ritchie C., et al. Cohort Profile: COVIDMENT: COVID-19 cohorts on mental health across six nations. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;51(3):e108–e122. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyab234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroenke K., Spitzer R., Williams J. The PHQ-9. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spitzer R., Kroenke K., Williams J., Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.González-Hijón J., Kähler A.K., Frans E.M., et al. Stress and Health; 2023. Unravelling the link between sleep and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lovik A., González-Hijón J., Kähler A.K., et al. Mental health indicators in Sweden over a 12-month period during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord. 2023;322:108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simon G., Von Korff M., Saunders K., et al. Association between obesity and psychiatric disorders in the US adult population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(7):824. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahamat-Saleh Y., Fiolet T., Rebeaud M., et al. Diabetes, hypertension, body mass index, smoking and COVID-19-related mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Open. 2021;11(10) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wootton R., Richmond R., Stuijfzand B., et al. Evidence for causal effects of lifetime smoking on risk for depression and schizophrenia: a Mendelian randomisation study. Psychol Med. 2019;50(14):2435–2443. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719002678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lenth R., Singmann H., Love J., Buerkner P., Herve M. Emmeans: estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. R Package Version. 2008;1(1):3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cleveland W. Robust locally-weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. JASA. 1976;74:829–836. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36(3) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck K., Vincent A., Becker C., et al. Prevalence and factors associated with psychological burden in COVID-19 patients and their relatives: a prospective observational cohort study. PLoS One. 2021;16(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cameron J.I., Chu L.M., Matte A., et al. One-year outcomes in caregivers of critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(19):1831–1841. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heesakkers H., van der Hoeven J.G., Corsten S., et al. Mental health symptoms in family members of COVID-19 ICU survivors 3 and 12 months after ICU admission: a multicentre prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2022;48(3):322–331. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06615-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang C., Chudzicka-Czupała A., Tee M.L., et al. A chain mediation model on COVID-19 symptoms and mental health outcomes in Americans, Asians and Europeans. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):6481. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-85943-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Renaud-Charest O., Lui L.M., Eskander S., et al. Onset and frequency of depression in post-COVID-19 syndrome: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;144:129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.09.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang C., Chudzicka-Czupała A., Grabowski D., et al. The association between physical and mental health and face mask use during the COVID-19 pandemic: a comparison of two countries with different views and practices. Frontiers Psychiatr. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.569981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vos L.M., Habibović M., Nyklíček I., Smeets T., Mertens G. Optimism, mindfulness, and resilience as potential protective factors for the mental health consequences of fear of the coronavirus. Psychiatry Res. 2021;300 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.