This case series describes organ preservation trends among patients with rectal cancer in the US from 2006 to 2020.

Key Points

Question

Is the use of organ preservation in rectal cancer increasing?

Findings

In this case series of 175 545 US adults with rectal cancer treated with curative intent from 2006 to 2020, there was a statistically significant increase in the absolute annual proportion of organ preservation for patients with stage IIA to IIC disease, stage IIIA to IIIC disease, and unknown clinical stage. Increased organ preservation was associated with increased multimodal therapy without tumor resection, rather than increased transanal local excisions.

Meaning

Rectal cancer is increasingly being managed medically, and new national quality standards and core outcome sets are urgently needed to ensure high-quality care delivery responsive to these trends.

Abstract

Importance

In March 2023, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network endorsed watch and wait for those with complete clinical response to total neoadjuvant therapy. Neoadjuvant therapy is highly efficacious, so this recommendation may have broad implications, but the current trends in organ preservation in the US are unknown.

Objective

To describe organ preservation trends among patients with rectal cancer in the US from 2006 to 2020.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective, observational case series included adults (aged ≥18 years) with rectal adenocarcinoma managed with curative intent from 2006 to 2020 in the National Cancer Database.

Exposure

The year of treatment was the primary exposure. The type of therapy was chemotherapy, radiation, or surgery (proctectomy, transanal local excision, no tumor resection). The timing of therapy was classified as neoadjuvant or adjuvant.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was the absolute annual proportion of organ preservation after radical treatment, defined as chemotherapy and/or radiation without tumor resection, proctectomy, or transanal local excision. A secondary analysis examined complete pathologic responses among eligible patients.

Results

Of the 175 545 patients included, the mean (SD) age was 63 (13) years, 39.7% were female, 17.4% had clinical stage I disease, 24.7% had stage IIA to IIC disease, 32.1% had stage IIIA to IIIC disease, and 25.7% had unknown stage. The absolute annual proportion of organ preservation increased by 9.8 percentage points (from 18.4% in 2006 to 28.2% in 2020; P < .001). From 2006 to 2020, the absolute rate of organ preservation increased by 13.0 percentage points for patients with stage IIA to IIC disease (19.5% to 32.5%), 12.9 percentage points for patients with stage IIIA to IIC disease (16.2% to 29.1%), and 10.1 percentage points for unknown stages (16.5% to 26.6%; all P < .001). Conversely, patients with stage I disease experienced a 6.1–percentage point absolute decline in organ preservation (from 26.4% in 2006 to 20.3% in 2020; P < .001). The annual rate of transanal local excisions decreased for all stages. In the subgroup of 80 607 eligible patients, the proportion of complete pathologic responses increased from 6.5% in 2006 to 18.8% in 2020 (P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

This case series shows that rectal cancer is increasingly being managed medically, especially among patients whose treatment historically relied on proctectomy. Given the National Comprehensive Cancer Network endorsement of watch and wait, the increasing trends in organ preservation, and the nearly 3-fold increase in complete pathologic responses, international professional societies should urgently develop multidisciplinary core outcome sets and care quality indicators to ensure high-quality rectal cancer research and care delivery accounting for organ preservation.

Introduction

In 2020, there were nearly 45 000 new cases of rectal cancer in the US and more than 730 000 cases worldwide.1,2 For nonmetastatic rectal cancer, the ideal therapy should achieve durable oncologic outcomes while minimizing treatment sequelae and preserving the quality of life. The approaches to achieving these goals are rapidly advancing, so understanding practice patterns is essential for guiding policymakers responsible for funding research priorities and defining multidisciplinary care standards.

Most treatment options for rectal cancer are associated with short- and long-term derangements in bowel, urinary, and sexual function. Radical resection is associated with high levels of functional sequelae, and there are long-standing efforts to increase rates of organ preservation.3 Presently, select patients with clinical stage I rectal cancer can undergo local excision.4 For patients with clinical stages II or III rectal cancer, the increasing adoption of neoadjuvant therapy led to the realization that clinical or pathologic complete responses are associated with favorable oncologic outcomes.5,6 These data, supported by seminal clinical trials, challenged the notion that excision of the rectum and the adjacent lymphovascular structures, or total mesorectal excision (TME), is necessary for all patients with locally advanced rectal cancer.7,8,9 Per the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), select patients with a complete clinical response to total neoadjuvant therapy may avoid tumor resection and be managed with watch-and-wait protocols that require intensive surveillance.4 Presently, the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons and the European Society for Medical Oncology advise that watch and wait be reserved for the protocolized setting.10,11 How to deliver watch and wait outside of clinical trials, and the processes for tracking the quality of care, are unknown. For example, a recent systematic review of multidisciplinary colorectal cancer quality indicators found that 6% of quality indicators addressed neoadjuvant therapy, 31.2% related to surgery, and none applied to patients who underwent a watch-and-wait therapy.12

Total neoadjuvant therapy, sphincter-preserving surgery, and minimally invasive surgical approaches are increasing in the US, but paradigm shifts in rectal cancer care are occurring in organ preservation.13,14,15 Because there are limited national data on organ preservation, we queried the National Cancer Database (NCDB) to assess trends in rectal cancer management from 2006 through 2020, hypothesizing that there would be an increasing adoption of organ preservation and pathologic complete responses. This information is essential for policymakers establishing core outcome sets and determining whether organ preservation–specific quality indicators are needed in the rapidly advancing therapeutic landscape for rectal cancer.

Methods

Data Source

The NCDB is a nationwide, facility-based cancer registry jointly sponsored by the American Cancer Society and the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. Trained tumor registrars extract patient demographic and clinical data on all cancers diagnosed at their facility according to standardized protocols. The NCDB captures more than 70% of the annual US incident cancer cases from more than 1500 facilities. The data set is deidentified, so institutional review board approval and patient informed consent were not required. This study followed best practice recommendations for using the NCDB and the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline (eTable 1 in Supplement 1).16,17

Study Population

For this retrospective, observational study, all adults (aged ≥18 years) with rectal adenocarcinoma diagnosed between 2006 and 2020 were identified in the NCDB Participant Use Files. We limited the analysis to patients who underwent curative treatment. Therefore, patients with stage IV disease; any evidence of metastasis; treatment with palliative intent (regardless of whether it was chemotherapy, radiation, or surgery); instances where any treatment modality was withheld due to comorbidities, patient preference, or death; and who underwent destructive procedures were excluded (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1). The analysis occurred between March and April 2023, when the 2020 Participant Use File included the most recent data available.

Multimodal Management

There is low adherence to clinical practice guidelines for rectal cancer in the US.18,19 Therefore, rather than classify multimodal therapies as guideline adherent or non–guideline adherent, the type and sequencing of all therapies were identified. Procedurally, patients were classified as undergoing a proctectomy, transanal local excision, or no tumor resection. Patients who had no tumor resection or a transanal local excision were considered as undergoing organ preservation. Patients underwent chemotherapy alone, radiation alone, surgery alone, neoadjuvant radiation followed by surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy, neoadjuvant multiagent chemotherapy with radiation alone or followed by surgery, neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiation followed by surgery, and surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation (eTable 2 in Supplement 1).

Additional Variables and Definitions

Standard NCDB coding was applied for all variables. The facility-level data included type (academic/research, comprehensive community, comprehensive cancer program, integrated cancer program) and geographic region. Patient-level factors included demographics (sex, age, race and ethnicity), Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Index (0, 1, 2, ≥3), insurance status, oncologic factors (stage, tumor grade, histology), and year of diagnosis. The tumor stage was defined using the clinical American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th edition staging system. Tumor grade and histology were also assessed over time.

Statistical Analysis

The primary objective was to characterize trends in organ preservation over the study period. Secondary objectives included assessing transanal local excision utilization over time, describing the multimodal therapies used over the study period, and examining trends in pathologic complete response rates after proctectomy (ypT0N0) or local excision (ypT0NX) in the subgroup who underwent neoadjuvant therapy followed by surgery.

Descriptive statistics are presented as the mean and SD for continuous variables and frequency (percentage) for categorical variables. Distributions of categorical variables by time (2006-2008, 2009-2011, 2012-2014, 2015-2017, and 2018-2020) were compared using χ2 tests. Next, the overall, and clinical stage–specific, annual trends in the proportion of organ preservation were assessed using the Cochran-Armitage test for trend. Similarly, a subgroup analysis of patients who underwent local excision or proctectomies with available pathologic stage information was performed to assess the annual trend in ypT0N0/NX response rates. All statistics were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc), and a 2-sided α < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient Population

Overall, 290 562 patients with rectal adenocarcinoma were identified, of whom 175 545 were included (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1). The mean (SD) age of the patients was 63 (13) years, 15.9% were younger than 50 years at diagnosis, 17.4% had clinical stage I disease, 24.7% had stage IIA to IIC disease, 32.1% had stage IIIA to IIIC disease, and 25.7% had unknown stage (Table). Patients treated in more contemporary periods tended to be younger, were more likely to be a race other than White, had higher Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Index scores, were treated at academic/research facilities, and had adenocarcinoma compared with mucinous and signet ring histology (Table).

Table. Characteristics of Patients and Rectal Cancer Care by Time Perioda.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006-2008 (n = 31 613) | 2009-2011 (n = 31 943) | 2012-2014 (n = 34 976) | 2015-2017 (n = 38 290) | 2018-2020 (n = 38 723) | |

| Age, y | |||||

| <50 | 4854 (15.4) | 5045 (15.8) | 5444 (15.6) | 6104 (15.9) | 6370 (16.5) |

| 50-59 | 7465 (23.6) | 7894 (24.7) | 9229 (26.4) | 10 099 (26.4) | 10 019 (25.9) |

| 60-69 | 7941 (25.1) | 8452 (26.5) | 9674 (27.7) | 10 789 (28.2) | 11 084 (28.6) |

| 70-79 | 6861 (21.7) | 6407 (20.1) | 6520 (18.6) | 7280 (19.0) | 7313 (18.9) |

| ≥80 | 4492 (14.2) | 4145 (13.0) | 4145 (11.8) | 4018 (10.5) | 3937 (10.2) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 12 931 (40.9) | 12 909 (40.4) | 13 710 (39.2) | 15 023 (39.2) | 15 112 (39.0) |

| Male | 18 682 (59.1) | 19 034 (59.6) | 21 266 (60.8) | 23 267 (60.8) | 23 611 (61.0) |

| Race and ethnicityb | |||||

| Asian | 1074 (3.4) | 1182 (3.7) | 1525 (4.4) | 1861 (4.9) | 1952 (5.0) |

| Black | 2532 (8.0) | 2714 (8.5) | 2972 (8.5) | 3235 (8.5) | 3333 (8.6) |

| White | 27 495 (87.0) | 27 586 (86.4) | 29 892 (85.5) | 32 406 (84.6) | 32 454 (83.8) |

| Other/unknown | 512 (1.6) | 461 (1.4) | 587 (1.7) | 788 (2.1) | 984 (2.5) |

| Insurance status | |||||

| Privately insured | 14 244 (45.1) | 14 095 (44.1) | 15 652 (44.8) | 17 414 (45.5) | 17 094 (44.1) |

| Government insured | 15 782 (49.9) | 15 997 (50.1) | 17 306 (49.5) | 19 215 (50.2) | 20 027 (51.7) |

| Uninsured | 1105 (3.5) | 1404 (4.4) | 1530 (4.4) | 1124 (2.9) | 1235 (3.2) |

| Unknown | 482 (1.5) | 447 (1.4) | 488 (1.4) | 537 (1.4) | 367 (1.0) |

| Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Index | |||||

| 0 | 24 208 (76.6) | 24 444 (76.5) | 26 533 (75.9) | 29 584 (77.3) | 29 445 (76.0) |

| 1 | 5477 (17.3) | 5635 (17.6) | 6319 (75.9) | 5868 (15.3) | 5898 (15.2) |

| 2 | 1393 (4.4) | 1315 (4.1) | 1528 (4.4) | 1655 (4.3) | 1811 (4.7) |

| ≥3 | 535 (1.7) | 549 (1.7) | 596 (1.7) | 1183 (3.1) | 1569 (4.1) |

| Facility type | |||||

| Comprehensive program | 2451 (7.8) | 2319 (7.3) | 2431 (7.0) | 2763 (7.2) | 2686 (6.9) |

| Comprehensive community | 13 095 (41.4) | 12 736 (39.9) | 13 865 (39.6) | 14 521 (37.9) | 14 545 (37.6) |

| Academic/research | 9524 (30.1) | 10 151 (31.8) | 11 749 (33.6) | 13 413 (35.0) | 13 839 (35.7) |

| Integrated network | 6543 (20.7) | 6737 (21.1) | 6931 (19.8) | 7593 (19.8) | 7653 (19.8) |

| Facility location | |||||

| New England | 1885 (6.0) | 1715 (5.4) | 1947 (5.6) | 2078 (5.4) | 2082 (5.4) |

| Middle Atlantic | 4564 (14.4) | 4690 (14.7) | 5182 (14.8) | 5440 (14.2) | 5333 (13.8) |

| South Atlantic | 6594 (20.9) | 6694 (21.0) | 7039 (20.1) | 7821 (20.4) | 7954 (20.5) |

| East North Central | 5666 (17.9) | 5646 (17.7) | 6294 (18.0) | 6895 (18.0) | 6868 (17.7) |

| East South Central | 2285 (7.2) | 2337 (7.3) | 2670 (7.6) | 2844 (7.4) | 2945 (7.6) |

| West North Central | 2965 (9.4) | 2969 (9.3) | 3203 (9.2) | 3218 (8.4) | 2978 (7.7) |

| West South Central | 2143 (6.8) | 2430 (7.6) | 2755 (7.9) | 3308 (8.6) | 3685 (9.5) |

| Mountain | 1428 (4.5) | 1549 (4.9) | 1662 (4.8) | 1705 (4.5) | 1819 (4.7) |

| Pacific | 4083 (12.9) | 3913 (12.3) | 4224 (12.1) | 4981 (13.0) | 5059 (13.1) |

| AJCC 8th edition clinical stage | |||||

| I | 5492 (17.4) | 7138 (22.4) | 6760 (19.3) | 6060 (15.8) | 5143 (13.3) |

| II | 7020 (22.2) | 8994 (28.2) | 9664 (27.6) | 9238 (24.1) | 8518 (22.0) |

| III | 5740 (18.2) | 8174 (25.6) | 11 311 (32.3) | 14 328 (37.4) | 16 812 (43.4) |

| Unknown | 13 361 (42.3) | 7637 (23.9) | 7241 (20.7) | 8664 (22.6) | 8250 (21.3) |

| Histology | |||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 29 650 (93.8) | 30 123 (94.3) | 33 265 (95.1) | 36 547 (95.5) | 37 554 (97.0) |

| Mucinous | 1704 (5.4) | 1583 (5.0) | 1470 (4.2) | 1455 (3.8) | 992 (2.6) |

| Signet ring cell | 259 (0.8) | 237 (0.7) | 241 (0.7) | 288 (0.8) | 177 (0.5) |

| Differentiation (grade) | |||||

| Well | 6691 (21.2) | 6946 (21.7) | 8114 (23.2) | 9034 (23.6) | 8820 (22.8) |

| Moderately | 20 867 (66.0) | 21 184 (66.3) | 23 334 (66.7) | 25 658 (67.0) | 28 821 (74.5) |

| Poorly | 4055 (12.8) | 3813 (11.9) | 3528 (10.1) | 3598 (9.4) | 1057 (2.7) |

Abbreviation: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer.

P < .001 for all factors over time by χ2 analysis.

Within the National Cancer Database, information regarding race and ethnicity is gathered through a variety of sources, including medical records, electronic medical record billing records, and patient self-reporting. Standardized choices for race and ethnicity are used, encompassing a range of options, including Other.

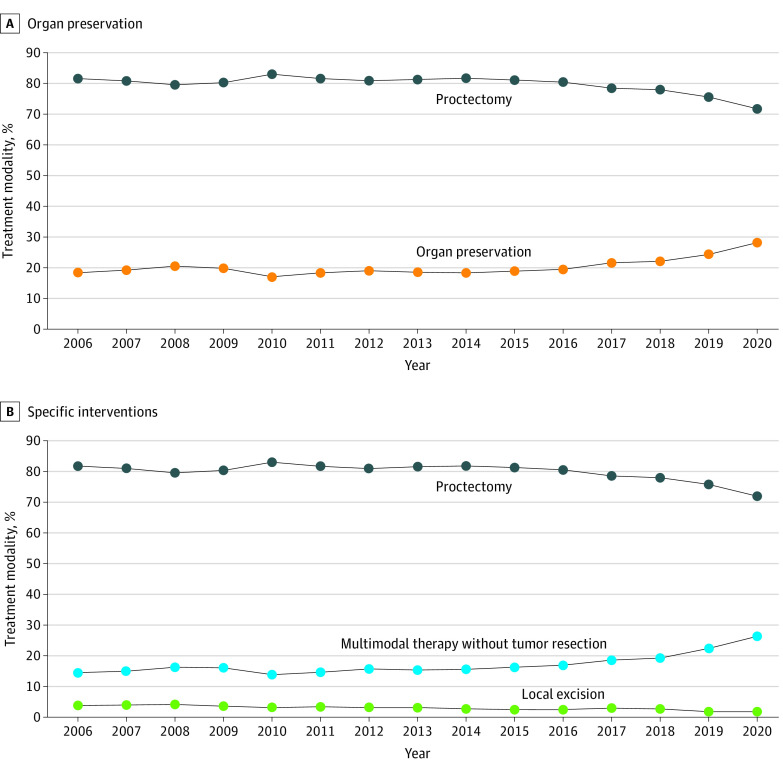

Trends in Organ Preservation

Overall, there was a statistically significant 9.8–percentage point absolute increase in the proportion of patients undergoing organ preservation, from 18.4% in 2006 to 28.2% in 2020 (P < .001; Figure 1A), representing a 53% relative increase. The pattern was associated with an 11.4–percentage point increase in patients undergoing chemotherapy and or radiation without tumor resection, from 14.5% in 2006 to 26.4% in 2020 (Figure 1B). Moreover, there was a 2.0–percentage point decline in the rate of transanal local excisions, from 3.9% in 2006 to 1.9% in 2020 (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Treatment Trends Over the Study Period (N = 175 545).

A, Organ preservation (local excision or multimodal therapy without tumor resection) vs proctectomy. B, Overall rates of proctectomy, local excision, and no tumor resection.

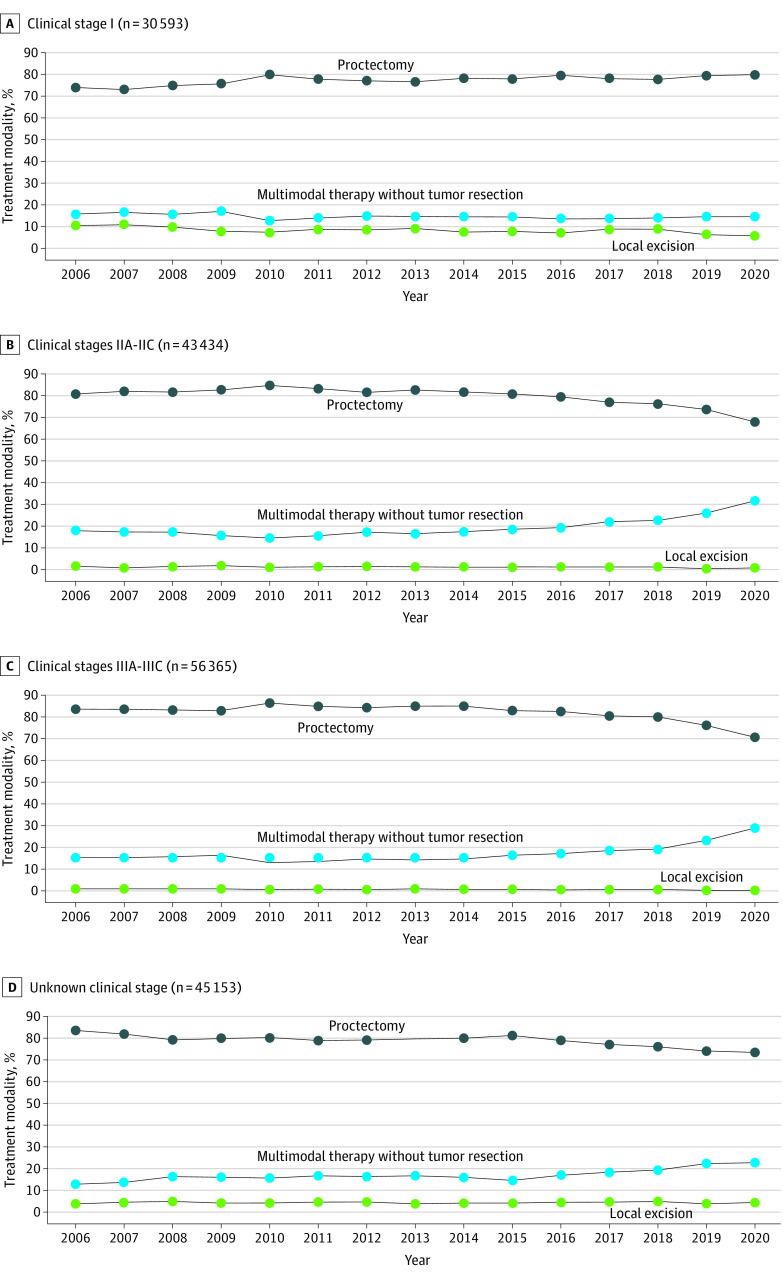

When stratified by stage, the patients with stage I disease had a 6.1–percentage point increase in the rates of proctectomies, from 73.6% in 2006 to 79.7% in 2020. Additionally, there was a 4.7–percentage point decline in the rate of transanal local excisions among patients with stage I disease. Together, there was a statistically significant decrease in the rates of organ preservation for patients with stage I disease (P < .001; Figure 2A). Patients with stage IIA to IIC disease had statistically significant increased rates of organ preservation over the study period, as the rate of chemotherapy and or radiation without tumor resection increased by 13.8 percentage points, from 18.0% in 2006 to 31.8% in 2020 for this group (P < .001; Figure 2B). Similarly, patients with stage IIIA to IIIC disease had statistically significant increased rates of organ preservation, as the rate of chemotherapy and or radiation without tumor resection among patients with clinical stage IIIA to IIIC disease increased by 13.5 percentage points, from 15.3% in 2006 to 28.8% in 2020 (P < .001; Figure 2C). The trends observed in patients with stage IIA to IIC and stage IIIA to IIIC disease were also observed among patients with unknown clinical stages (Figure 2D). The type and sequence of all therapies delivered by clinical stage are summarized in eTable 2 in Supplement 1.

Figure 2. Treatment Trends by Clinical Stage of Rectal Cancer.

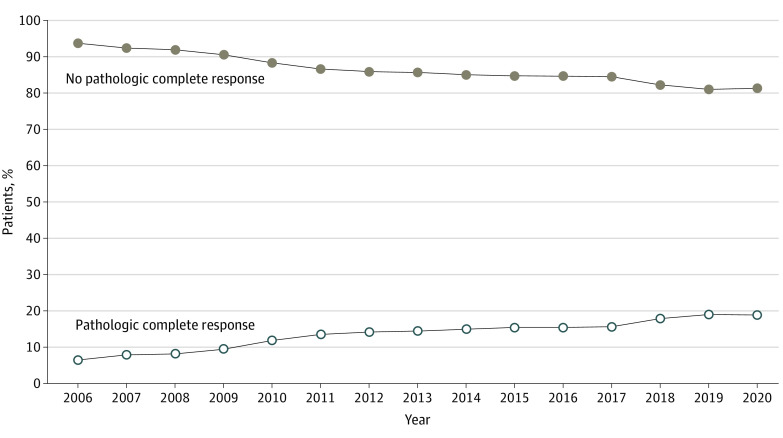

Pathologic Complete Response

There were 88 299 patients who underwent neoadjuvant therapy followed by tumor resection (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). Of these, 7692 were excluded due to unknown pathological stages, leaving a total of 80 607 patients for this subset analysis. Among the included patients, there was a statistically significant increase in the proportion of patients with ypT0N0/NX pathology over the study period, from 6.5% in 2006 to 18.8% in 2020 (P < .001; Figure 3).

Figure 3. Patients With Complete Pathologic Response (ypT0N0/NX) After Neoadjuvant Therapy.

Discussion

This study presents national practice patterns among patients with potentially curable rectal cancer in the US. From 2006 to 2020, there was a nearly 10–percentage point absolute increase in the overall rate of organ preservation for rectal cancer. The increased organ preservation rates were associated with changes in care received by patients with stage II to III disease, a group whose treatment has historically prioritized TME. Rather than increasing transanal local excision utilization, more patients with stage II to III disease are avoiding tumor resection. Additionally, in the patients who do receive neoadjuvant therapy and tumor resection, the rates of ypT0N0/NX responses increased nearly 3-fold over the study period. With the NCCN now supporting watch-and-wait approaches among select patients and 18% to 19% of patients undergoing surgery after neoadjuvant therapy having ypT0N0/NX responses, the rates of proctectomy may decrease even further for future patients as the identification of complete clinical responders improves. These data suggest that governing bodies overseeing and developing accreditation standards for rectal cancer care should urgently consider developing core outcome sets and novel quality metrics that reflect global trends toward organ preservation, particularly watch and wait.

This study differs from the existing NCDB-based literature by analyzing organ preservation and opportunities for organ preservation among patients with complete pathologic responses. Although these data cannot elucidate why organ preservation rates are increasing, it is not due to increasing transanal local excision utilization, and we excluded patients who refused or were not offered surgery due to comorbidities. Moreover, since the rates of upfront therapy, particularly multiagent chemotherapy combined with radiation, are increasing, the declining surgical rates are likely partly attributable to complete clinical responses and watch-and-wait approaches. This hypothesis is supported indirectly by the increase in ypT0N0/NX responses from 6.5% in 2006 to 18.8% in 2020. The increasing rates of complete pathologic responses parallel data from Sweden showing increased rates of complete pathologic responses from 2009 to 2020.20 Elsewhere, the 2022 National Bowel Cancer Audit noted that the rate of major rectal cancer resections declined from 54.0% in 2016 to 2017 to 48.3% in 2018 to 2019.21

Considering the declining number of patients undergoing tumor resection, analyzing the variations in the use of different treatment strategies at the national level is crucial from a policy perspective.22 The NCCN now supports a watch-and-wait approach for patients with complete clinical responses to total neoadjuvant therapy.4 The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons and the European Society of Medical Oncology recommend that watch-and-wait approaches be reserved for investigational protocols.10,11 Aligning professional society recommendations with the NCCN will likely occur over time, but currently there are no quality indicators to guide the implementation and quality of watch-and-wait–based programs outside of the investigational setting.10,11,12 Several important clinical and logistical questions from a care delivery perspective remain unanswered around the widespread implementation of organ preservation, particularly watch and wait. Identifying candidates willing and able to perform long-term intensive surveillance outside of clinical trial settings and the intensity (frequency of reassessment and what modalities should be embedded) of surveillance programs are salient questions. Furthermore, when defining the optimal surveillance approach, one must address the crucial aspect of ensuring maximum compliance with surveillance protocols to enable prompt salvage TME in cases of local tumor regrowth. Moreover, ensuring equitable deployment of watch and wait and organ preservation is essential since there is potential for exacerbating socioeconomic care disparities in the US. There is no indication that the trends observed in this study should reverse, and even if they plateau, establishing quality standards for organ preservation is a pressing issue that should involve all relevant stakeholders, including patients.

In contrast with the increasing rates of organ preservation among patients with stage II to III rectal cancer, the rate of proctectomies increased by more than 6 percentage points among those with stage I disease. In parallel to the increasing proctectomies among patients with stage I disease, the utilization of transanal local excisions decreased by nearly 5 percentage points over the study period. This trend differs from the patterns observed between 1989 and 2010, where the rates of transanal local excision in the US increased among patients with T1 and T2 tumors.23,24 The declining transanal local excision use may reflect evidence suggesting substantial quality-of-life and functional impairments associated with this approach.25 More broadly, the declining rates of organ preservation among patients with stage I disease in recent years is noteworthy because it coincided with multiple clinical trials that indicated that about half of the patients with stage I disease could achieve a complete pathologic response, and more than two-thirds of them could undergo organ preservation.26,27,28 These data seem to document a paradox in the treatment of potentially curable rectal cancer. Specifically, patients with stage I disease are increasingly undergoing proctectomies, while patients with locally advanced disease are increasingly receiving organ preservation. This finding warrants comprehensive investigation and highlights the pressing need for innovative trials like STAR-TREC that can provide crucial information about the management and outcomes of patients with early-stage rectal cancer.29

Limitations

There are limitations to consider when interpreting these findings. First, we cannot identify patients who require salvage TME, which may falsely elevate the overall proportion of organ preservation. However, these trends are consistent with European experiences and reflect the initial therapeutic course, which suggests that more patients are being managed with the intention of organ preservation.20 This reinforces the notion that there is a need for core outcome sets and quality metrics for organ preservation to ensure high-quality care delivery. Next, this analysis was focused on national trends to inform policy, so we intentionally avoided identifying patient or facility factors associated with increased odds of organ preservation. These factors, along with the potential institutional clustering, are beyond the scope of this analysis, which attempts to characterize the overall care of patients with rectal cancer in the US. Next, we did not analyze survival outcomes by treatment strategy since survival outcomes based on the NCDB do not correlate well with clinical trials, and our aim was policy oriented rather than comparative effectiveness.30,31 Lastly, given the retrospective nature of the data source and limited or missing clinical data, it is impossible to prove causal inferences. Consequently, this study intended to identify trends in the initial therapeutic courses and inform policy, to which the NCDB is well suited.22

Conclusions

In summary, results of this case series showed that rectal cancer is increasingly being managed nonsurgically. Despite the prominence of clinical treatment guidelines in influencing care delivery, wide variation in treatment strategies exist. The increasing trends toward organ preservation should spur international medical and surgical societies to collaborate with all of the relevant stakeholders to codify core outcome sets and care standards for rectal cancer care that incorporate organ preservation. Core outcome sets are important for guiding future research endeavors, and standardized quality metrics for these increasingly common clinical scenarios are needed to ensure high-quality rectal cancer care delivery.

eFigure. Derivation of the cohort

eTable 1. STROBE Statement

eTable 2. Type and sequence of multimodal therapy over time

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araghi M, Soerjomataram I, Bardot A, et al. Changes in colorectal cancer incidence in seven high-income countries: a population-based study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4(7):511-518. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30147-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peeters KC, van de Velde CJ, Leer JW, et al. Late side effects of short-course preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: increased bowel dysfunction in irradiated patients—a Dutch colorectal cancer group study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(25):6199-6206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.14.779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: rectal cancer. National Comprehensive Cancer Network . July 25, 2023. Accessed July 29, 2023. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/rectal.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.van der Valk MJM, Hilling DE, Bastiaannet E, et al. ; IWWD Consortium . Long-term outcomes of clinical complete responders after neoadjuvant treatment for rectal cancer in the International Watch & Wait Database (IWWD): an international multicentre registry study. Lancet. 2018;391(10139):2537-2545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31078-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maas M, Nelemans PJ, Valentini V, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with a pathological complete response after chemoradiation for rectal cancer: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(9):835-844. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70172-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rullier E, Rouanet P, Tuech JJ, et al. Organ preservation for rectal cancer (GRECCAR 2): a prospective, randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10093):469-479. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31056-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerard JP, Barbet N, Schiappa R, et al. ; ICONE group . Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy with radiation dose escalation with contact x-ray brachytherapy boost or external beam radiotherapy boost for organ preservation in early cT2-cT3 rectal adenocarcinoma (OPERA): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8(4):356-367. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00392-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Aguilar J, Patil S, Gollub MJ, et al. Organ preservation in patients with rectal adenocarcinoma treated with total neoadjuvant therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(23):2546-2556. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.00032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.You YN, Hardiman KM, Bafford A, et al. ; On Behalf of the Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons . The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63(9):1191-1222. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glynne-Jones R, Wyrwicz L, Tiret E, et al. ; ESMO Guidelines Committee . Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl 4):iv22-iv40. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donnelly C, Or M, Toh J, et al. Measurement that matters: a systematic review and modified Delphi of multidisciplinary colorectal cancer quality indicators. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. Published online February 1, 2023. doi: 10.1111/ajco.13917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu J, Ladbury C, Glaser S, et al. Patterns of care for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer treated with total neoadjuvant therapy at predominately academic centers between 2016-2020: an NCDB analysis. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2023;22(2):167-174. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2023.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emile SH, Horesh N, Freund MR, et al. Trends in the characteristics, treatment, and outcomes of rectal adenocarcinoma in the US from 2004 to 2019: a National Cancer Database analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(3):355-364. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.6116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aquina CT, Ejaz A, Tsung A, Pawlik TM, Cloyd JM. National trends in the use of neoadjuvant therapy before cancer surgery in the US from 2004 to 2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e211031. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.1031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344-349. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merkow RP, Rademaker AW, Bilimoria KY. Practical guide to surgical data sets: National Cancer Database (NCDB). JAMA Surg. 2018;153(9):850-851. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.0492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melucci AD, Loria A, Ramsdale E, Temple LK, Fleming FJ, Aquina CT. An assessment of left-digit bias in the treatment of older patients with potentially curable rectal cancer. Surgery. 2022;172(3):851-858. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2022.04.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu Z, Mohile SG, Tejani MA, et al. Poor compliance with adjuvant chemotherapy use associated with poorer survival in patients with rectal cancer: an NCDB analysis. Cancer. 2017;123(1):52-61. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Temmink SJD, Martling A, Angenete E, Nilsson PJ. Complete response rates in rectal cancer: temporal changes over a decade in a population-based nationwide cohort. Eur J Surg Oncol. Published online July 20, 2023. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2023.106991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Bowel Cancer Audit: annual report 2022. Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership . Accessed March 23, 2023. https://www.nboca.org.uk/content/uploads/2023/01/NBOCA-2022-Final.pdf

- 22.Bilimoria KY, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, Ko CY. The National Cancer Data Base: a powerful initiative to improve cancer care in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(3):683-690. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9747-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.You YN, Baxter NN, Stewart A, Nelson H. Is the increasing rate of local excision for stage I rectal cancer in the United States justified? a nationwide cohort study from the National Cancer Database. Ann Surg. 2007;245(5):726-733. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000252590.95116.4f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stitzenberg KB, Sanoff HK, Penn DC, Meyers MO, Tepper JE. Practice patterns and long-term survival for early-stage rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(34):4276-4282. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.1860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stijns RCH, de Graaf EJR, Punt CJA, et al. ; CARTS Study Group . Long-term oncological and functional outcomes of chemoradiotherapy followed by organ-sparing transanal endoscopic microsurgery for distal rectal cancer: the CARTS study. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(1):47-54. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.3752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lezoche E, Baldarelli M, Lezoche G, Paganini AM, Gesuita R, Guerrieri M. Randomized clinical trial of endoluminal locoregional resection versus laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for T2 rectal cancer after neoadjuvant therapy. Br J Surg. 2012;99(9):1211-1218. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Habr-Gama A, São Julião GP, Vailati BB, et al. Organ preservation in cT2N0 rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy: the impact of radiation therapy dose-escalation and consolidation chemotherapy. Ann Surg. 2019;269(1):102-107. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garcia-Aguilar J, Shi Q, Thomas CR Jr, et al. A phase II trial of neoadjuvant chemoradiation and local excision for T2N0 rectal cancer: preliminary results of the ACOSOG Z6041 trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(2):384-391. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1933-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bach SP; STAR-TREC Collaborative . Can we Save the rectum by watchful waiting or TransAnal surgery following (chemo)Radiotherapy versus Total mesorectal excision for early REctal Cancer (STAR-TREC)? protocol for the international, multicentre, rolling phase II/III partially randomized patient preference trial evaluating long-course concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus short-course radiotherapy organ preservation approaches. Colorectal Dis. 2022;24(5):639-651. doi: 10.1111/codi.16056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soni PD, Hartman HE, Dess RT, et al. Comparison of population-based observational studies with randomized trials in oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(14):1209-1216. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.01074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar A, Guss ZD, Courtney PT, et al. Evaluation of the use of cancer registry data for comparative effectiveness research. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e2011985. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.11985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Derivation of the cohort

eTable 1. STROBE Statement

eTable 2. Type and sequence of multimodal therapy over time

Data Sharing Statement