Abstract

Metastasis is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths and myeloid cells are critical in the metastatic microenvironment. Here, we explore the implications of reprogramming pre-metastatic niche myeloid cells by inducing trained immunity with whole beta-glucan particle (WGP). WGP-trained macrophages had increased responsiveness not only to lipopolysaccharide but also to tumor-derived factors. WGP in vivo treatment led to a trained immunity phenotype in lung interstitial macrophages, resulting in inhibition of tumor metastasis and survival prolongation in multiple mouse models of metastasis. WGP-induced trained immunity is mediated by the metabolite sphingosine-1-phosphate. Adoptive transfer of WGP-trained bone marrow-derived macrophages reduced tumor lung metastasis. Blockade of sphingosine-1-phosphate synthesis and mitochondrial fission abrogated WGP-induced trained immunity and its inhibition of lung metastases. WGP also induced trained immunity in human monocytes, resulting in antitumor activity. Our study identifies the metabolic sphingolipid–mitochondrial fission pathway for WGP-induced trained immunity and control over metastasis.

Cancer metastasis accounts for more than 90% of cancer-related deaths and is a major cause of cancer-related mortality in humans1. Accumulating evidence suggests that before metastasis, factors released from the primary tumors into the circulation can prime the distant organs to generate an environment that is supportive for tumor survival and growth2–4. This phenomenon has been termed as a pre-metastatic niche. Myeloid cell signatures and pathways are among the most significantly enhanced features within the pre-metastatic microenvironment5. Therefore, polarizing myeloid cells in the pre-metastatic niche toward an antitumor phenotype may provide immune surveillance to eliminate or control metastasis.

Innate immune cells are conventionally not believed to retain a memory phenotype. However, emerging evidence suggests that invertebrates, lower vertebrates and plants are able to respond adaptively to recurrent infections despite lacking the memory features afforded by the adaptive immune system. These observations have led to the development of a new concept of innate immune memory, also known as trained innate immunity or trained immunity6. Trained immunity is associated with metabolic, epigenetic and transcriptomic reprogramming, which results in an increased responsiveness to a nonspecific secondary insult7–11. The induction of trained immunity has been explored for its application in health and disease, especially infectious diseases and inflammatory conditions12–14. In addition, the concept of utilizing trained immunity as a means to control tumor progression is emerging15,16. However, the mechanisms of how a trained response is elicited by trained innate immune cells to control cancer progression or the etiology of secondary stimuli that trigger trained responses have not been well understood.

Many biological agents, including polysaccharide fungal beta-glucans, have the ability to induce trained immunity. Fungal beta-glucans from Candida albicans and Trametes versicolor and beta-glucan from Saccharomyces cerevisiae have been studied for their ability to induce trained immunity12,15,17. Although beta-glucan has been used as an immunomodulatory agent in cancer18–20, enabling trained immunity using beta-glucan for cancer treatment is just emerging.

In this study, we show that yeast-derived WGP-trained macrophages not only respond to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) as a secondary stimulus, but also elicit a trained response upon exposure to tumor cells and tumor-derived soluble factors. WGP-induced trained immunity effectively controls tumor metastasis and lung interstitial macrophages (IMs) are the primary effector cells. In addition, adoptive transfer of trained innate cells reduces tumor metastasis. The metabolic sphingolipid synthesis pathway-mediated mitochondrial fission is an underlying mechanism for WGP-mediated trained immunity and cancer metastasis inhibition. These findings highlight the use of trained immunity as an approach for cancer treatment and metastasis control.

Results

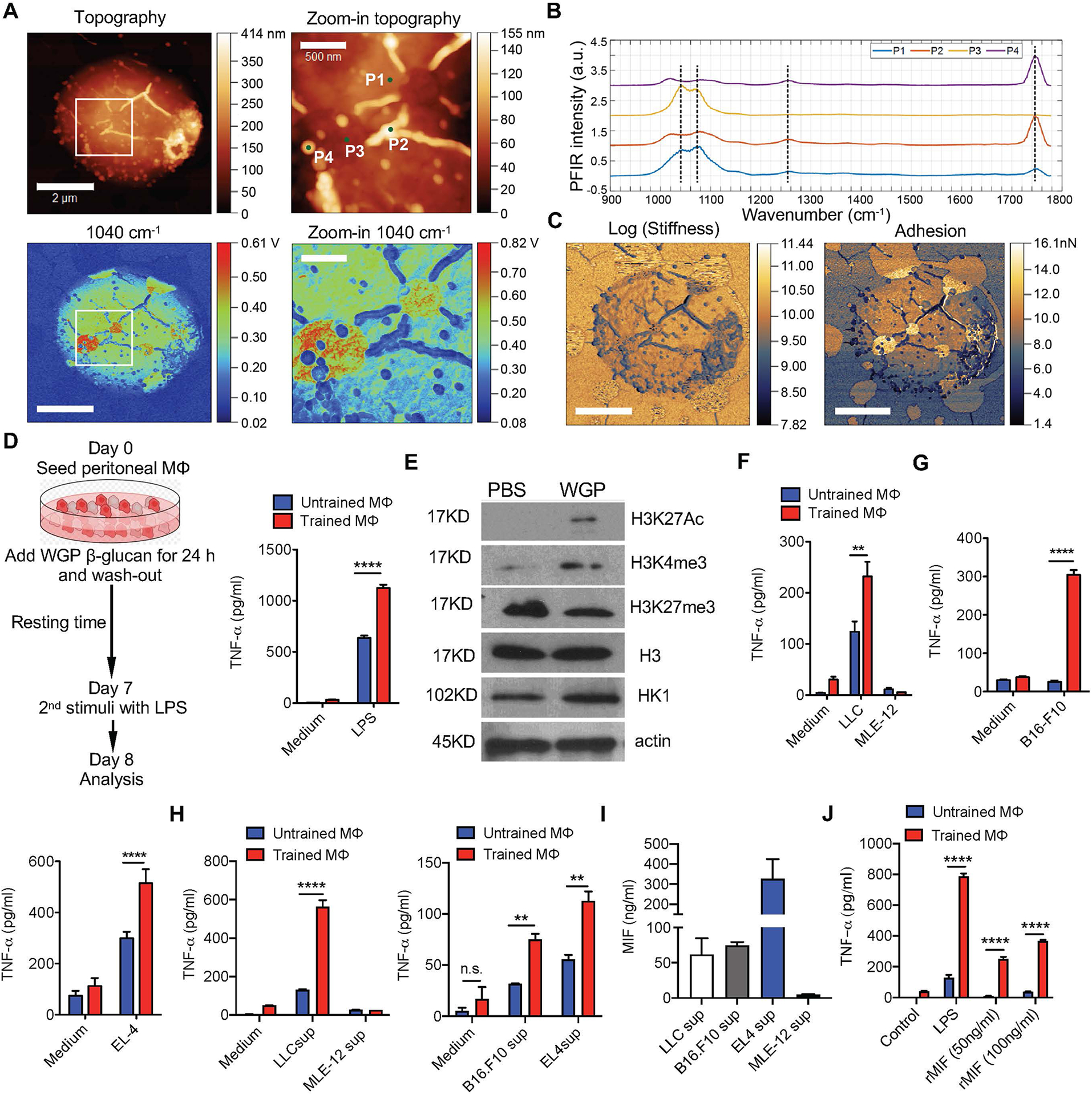

Tumor-derived factors stimulate trained responses

Before using WGP to induce trained immunity, we performed the chemical, topographical and mechanical mapping of WGP with ~6-nm resolution by combining peak force infrared (PFIR) microscopy with super-resolution fluorescence microscopy21,22 (Extended Data Fig. 1a–c). PFIR scans revealed that WGP is mainly composed of beta-glucan, as indicated by infrared (IR) peaks near 1,140–1,160 cm−1, but also displays some heterogeneous surface features (P2 and P4; Extended Data Fig. 1a) that are enriched in lipid-containing components, as indicated by the intense IR peak at ~1,750 cm−1. Using GFP-tagged Dectin-1 RAW 264.7 cells, we observed that WGP was phagocytosed by RAW cells and Dectin-1 was recruited and clustered at the site of the phagocytic cup (Extended Data Fig. 1d,e), suggesting that Dectin-1 is the critical receptor for WGP phagocytosis. We next performed an in vitro training experiment with WGP (Fig. 1a). Cytokine tumor necrosis factor (TNF) was used as a surrogate marker to measure the trained response12. WGP-trained macrophages showed an enhanced TNF production to LPS restimulation as compared to untrained macrophages (Fig. 1a), indicating that WGP induces trained immunity. This effect is dependent on Dectin-1 as the increased TNF production was abolished in Dectin-1-deficient macrophages (Fig. 1b). Macrophages treated with polystyrene beads that were the same size as WGP showed no enhanced TNF response (Fig. 1c), suggesting that the induced trained immunity is WGP specific. WGP training was also associated with metabolic reprogramming as revealed by increased hexokinase 2 (HK2) expression (Fig. 1d), consistent with previous findings10.

Fig. 1 |. WGP-induced trained immunity in macrophages.

a, Schema for WGP in vitro training assay (left). TNF production by in vitro WGP-trained (n = 6) or untrained (n = 6) peritoneal macrophages after LPS restimulation assessed by ELISA (right). b, TNF production by in vitro WGP-trained and untrained peritoneal macrophages of WT (n = 5) and Dectin-1-deficient mice (n = 5). c, TNF production by WGP-trained peritoneal macrophages versus those treated with polystyrene beads after LPS restimulation (n = 3). Untrained macrophages were used as control. d, HK2 expression in untrained (n = 3) or WGP-stimulated (n = 4) macrophages. Representative western blot and summarized densitometry data. P value was derived from an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. e, TNF production by in vitro WGP-trained or untrained peritoneal macrophages (n = 3) upon co-culture with LLC and MLE-12 cells. f, TNF production by in vitro WGP-trained or untrained peritoneal macrophages (n = 2) co-cultured with B16F10 (left) and EL4 cells (right). g, TNF production by in vitro WGP-trained or untrained peritoneal macrophages (n = 2, 3) upon LLC or MLE-12 culture supernatant (sup) restimulation (left), and B16F10 or EL4 culture supernatant restimulation (right). h, Levels of MIF (n = 2) from different cell culture supernatants measured by ELISA. i, TNF production by in vitro WGP-trained or untrained peritoneal macrophages upon rMIF restimulation (n = 4). j, TNF production by WGP-trained peritoneal macrophages from WT (n = 2) and MIF KO (n = 3) after LPS or LLC supernatant (40%) restimulation. k, TNF production by WGP-trained and untrained peritoneal macrophages upon restimulation with LLC supernatant in the presence or absence of MIF neutralizing monoclonal antibody (mAb; n = 3). l, TNF production by WGP-trained and untrained BMDMs from WT (n = 3) and CD74 KO mice (n = 3) upon restimulation with rMIF, LLC supernatant and LPS. Data are representative of two or three independent experiments and presented as the mean ± s.e.m. **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001. P values were derived from two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey’s multiple-comparison test (a–c, e–g and i–l).

Although LPS has been commonly used as a secondary stimulus to induce a trained response, it is unknown how trained responses are elicited in different health or disease states. To address whether a trained response can be induced by tumors, we co-cultured tumor cells with WGP-trained macrophages. WGP-trained macrophages induced a stronger TNF response when co-cultured with Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells, but not mouse lung epithelial cell line, MLE-12 (Fig. 1e), suggesting that tumor-specific factors stimulate the trained response. This effect was also shown by co-culturing WGP-trained macrophages with B16F10 melanoma and EL4 lymphoma cells (Fig. 1f), indicating that elicitation of the trained response is not specific to a single tumor cell type. To determine if tumor-secreted factors could act as a secondary stimulus for a trained response, LLC or MLE-12 culture supernatants were used. WGP-trained macrophages produced a significantly higher TNF when restimulated with LLC culture supernatant as compared to untrained controls or supernatants from control MLE-12 cells (Fig. 1g). B16F10 and EL4 culture supernatants also stimulated trained responses (Fig. 1g). To explore which tumor-secreted factors are responsible for this effect, we quantified one of the most widely studied tumor-secreted cytokines, macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF). The MIF levels ranged from 50 to 350 ng ml−1 in the tumor culture supernatants (Fig. 1h). When WGP-trained macrophages were restimulated with physiologically relevant concentrations of recombinant MIF (rMIF), a dose-dependent enhanced TNF response was observed (Fig. 1i). Both tumor cells and macrophages secrete MIF23, so we used macrophages from MIF knockout (KO) mice and observed that the TNF level was similar in WGP-trained MIF KO and wild-type (WT) macrophages (Fig. 1j), suggesting that tumor-secreted MIF stimulates a trained response. Addition of anti-MIF monoclonal antibody abrogated the LLC supernatant-stimulated enhanced TNF production (Fig. 1k). CD74 is considered a key receptor for MIF24. WGP-trained CD74 KO macrophages produced less TNF compared to WT counterparts upon restimulation with rMIF (Fig. 1l) and LLC supernatant (Fig. 1l). In contrast, WGP-trained WT and CD74 KO macrophages produced similar levels of TNF upon LPS restimulation (Fig. 1l). These results suggest that WGP induces trained immunity in vitro and that WGP-trained macrophages elicit a trained response upon reexposure not only to LPS but also to tumor cells and tumor-derived factors such as MIF.

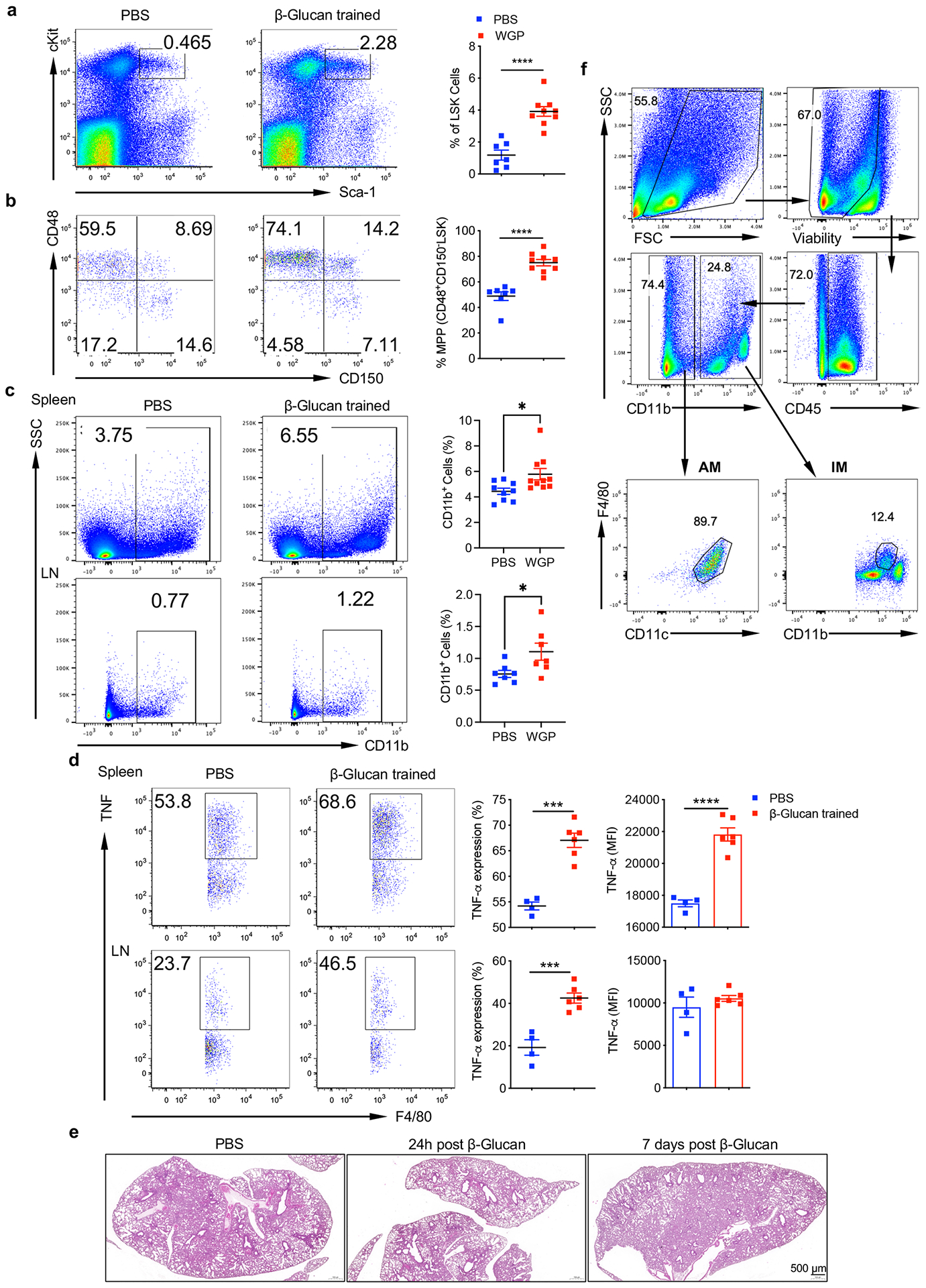

Whole beta-glucan particle in vivo treatment alters myeloid composition in the lungs

To examine whether WGP treatment in vivo could also induce trained immunity, WT C57BL/6 mice received one dose of intraperitoneal (i.p.) WGP. Given that emergency myelopoiesis is an important attribute of fungal beta-glucan and BCG-induced trained immunity25–27, we hypothesized that WGP may also stimulate bone marrow (BM) myelopoiesis and promote Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+ (LSK) hematopoietic progenitor stem cell (HPSC) expansion. BM cells harvested from in vivo WGP-trained mice showed an increased percentage of LSK HPSCs (Extended Data Fig. 2a) and CD48+CD150− LSK cells also known as multipotent progenitors (MPPs; Extended Data Fig. 2b). To evaluate whether WGP-induced BM myelopoiesis results in a systemic increase in myeloid cells and trained immunity, spleen and inguinal lymph nodes were collected. Both spleen and inguinal lymph nodes from WGP-trained mice showed an increase in CD11b+ myeloid cells (Extended Data Fig. 2c). Trained immunity was also induced in macrophages as revealed by an increased TNF expression (Extended Data Fig. 2d). However, no systemic inflammation in tissues such as the lungs was observed in WGP-trained mice (Extended Data Fig. 2e).

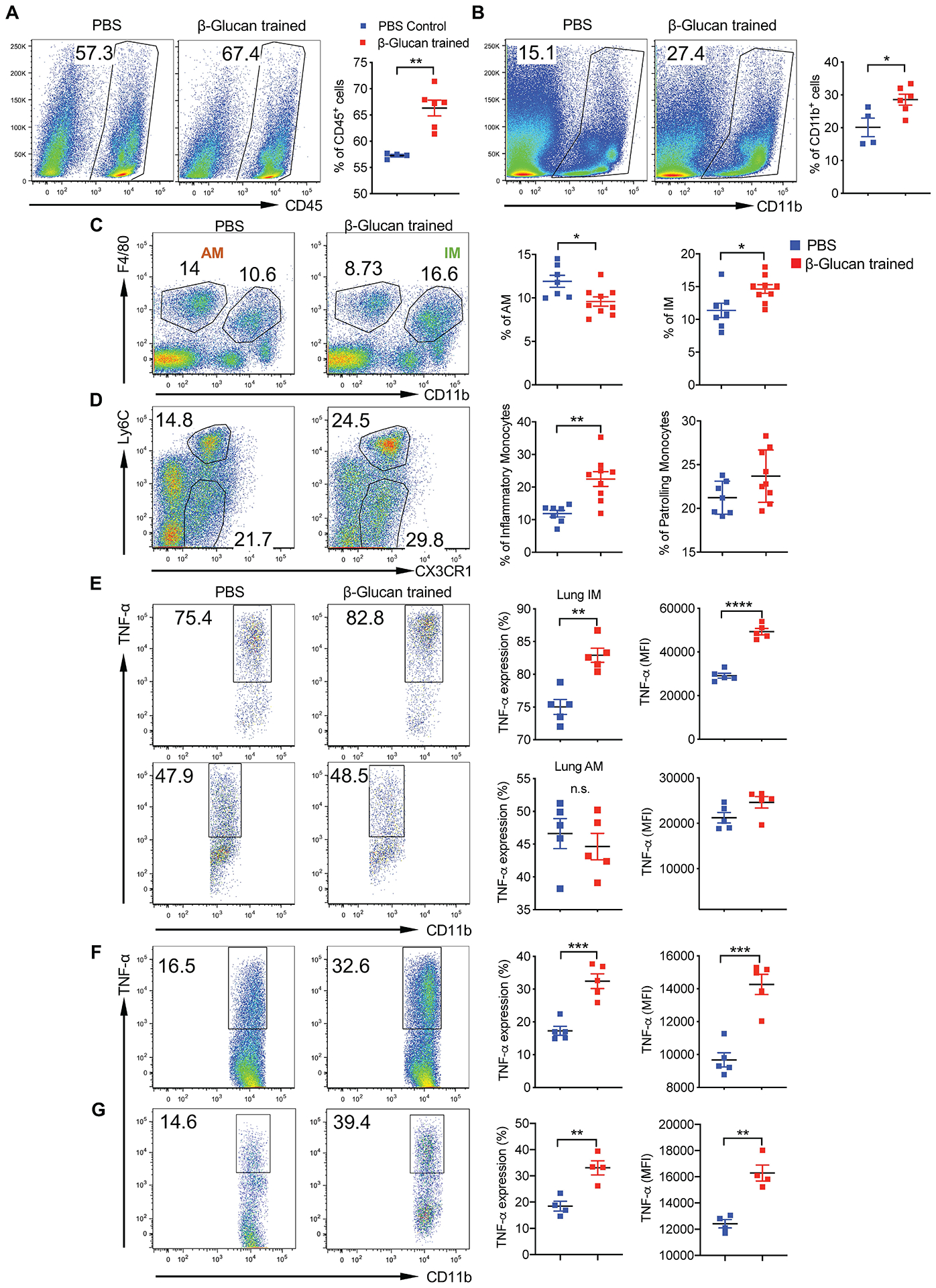

We next determined whether WGP could induce similar changes in the lung myeloid cell compartment, as the lung is a common site of tumor metastasis. Mice treated with WGP had significantly increased CD45+ (Fig. 2a) and CD11b+ cells (Fig. 2b) in the lungs compared to PBS controls. An increase in CD11b+F4/80+ IMs and a decrease in CD11b−F4/80+CD11c+ alveolar macrophages (AMs) occurred in WGP-trained mice (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 2f). We also observed a significant increase in the frequency of CD11b+Ly6ChiCX3CR1+ inflammatory monocytes and a slight increase in the frequency of CD11b+Ly6CloCX3CR1+ patrolling monocytes after WGP treatment (Fig. 2d). Lung IMs from WGP-treated mice showed an increased expression of TNF upon LPS restimulation (Fig. 2e), suggesting a trained immunity phenotype. Lung AMs, however, did not show any significant difference in TNF expression (Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2 |. In vivo whole beta-glucan particle treatment trains lung interstitial macrophages.

Six-week-old C57BL/6 mice were injected with WGP (1 mg) or i.p. PBS on day 0 and the lungs were collected on day 7. Single-cell suspensions were stained for analysis by flow cytometry. a, Frequency of total viable, CD45+ cells in the lungs of PBS (n = 4) and WGP (n = 6) trained mice. b, Frequency of CD11b+ myeloid cells in the lungs of PBS (n = 4) and WGP (n = 6) trained mice. Cells were gated on viable, CD45+ cells. c, Frequency of AMs and IMs in the lungs of PBS (n = 7) and WGP (n = 9) trained mice. Cells were gated on viable, CD45+ cells. d, Frequency of inflammatory monocytes and patrolling monocytes in the lungs of mice trained with PBS (n = 7) and WGP (n = 9). Cells were gated on viable, CD11b+ cells. e–g, Percentage and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of intracellular TNF expression in lung IMs and AMs of PBS (n = 5) and WGP (n = 5) trained mice after ex vivo stimulation with LPS (e), LLC culture supernatants (n = 5 versus 5; f) or rMIF (n = 4 versus 4; g). Representative dot plots and summarized data are shown. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. P values were determined by an unpaired two-tailed student’s t-test. Data are representative of two individual experiments and presented as the mean ± s.e.m.

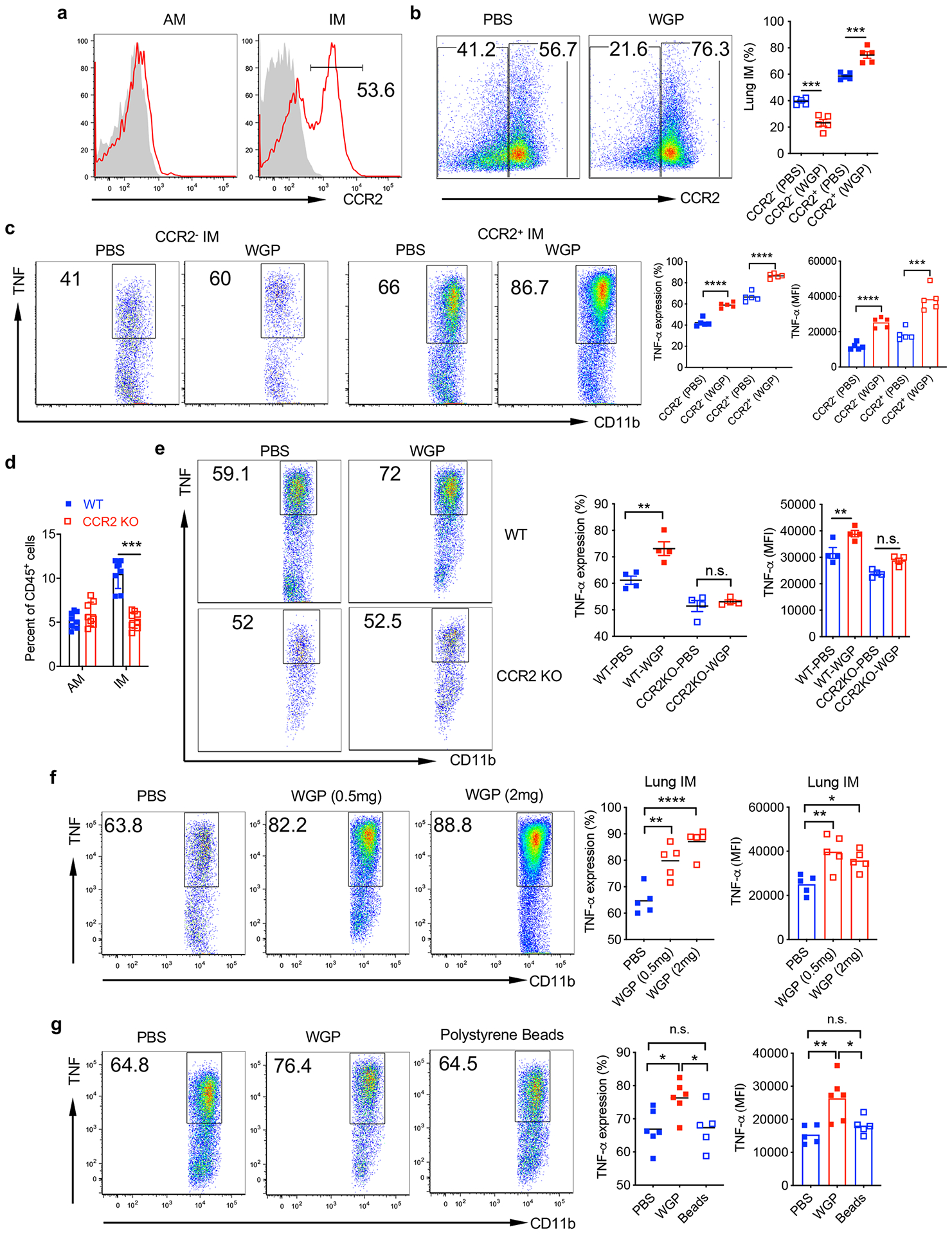

Lung IMs are heterogenous populations and contain at least two distinct subsets in the steady state28,29. CCR2+ IMs are thought to be derived from BM-originated precursors30 and constitute approximately 50% of total IMs (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Upon WGP training, the frequency of CCR2+ IMs increased while CCR2− IMs decreased (Extended Data Fig. 3b). However, both subsets from WGP-trained mice elicited a trained response (Extended Data Fig. 3c). To dissect the relationship between CCR2+ and CCR2− IMs, we used CCR2 KO mice and found that lung IMs were reduced about 50% compared to WT mice, while AMs were unchanged (Extended Data Fig. 3d). WGP-induced trained immunity was abrogated in CCR2 KO mice (Extended Data Fig. 3e), suggesting that the observed CCR2− IM trained immunity is dependent on trained CCR2+ IMs.

We next treated mice i.p. with 0.5 mg or 2 mg of WGP to determine the optimal dose. WGP training showed a significant increase in TNF expression in lung IMs. There was no substantial difference between 0.5 mg and 2 mg of WGP treatment (Extended Data Fig. 3f). Therefore, 1 mg was used for our subsequent experiments. To ensure that the lung IM trained phenotype was a result of a WGP-induced effect, polystyrene beads were i.p. injected. Lung IMs showed a significant increase in TNF expression in WGP-trained mice but not in polystyrene bead-treated mice (Extended Data Fig. 3g). We also stimulated lung IMs with LLC culture supernatants and rMIF. WGP-trained lung IMs showed higher TNF expression upon stimulation with LLC culture supernatants (Fig. 2f) and rMIF (Fig. 2g) compared to controls. These results suggest that WGP in vivo training induces myelopoiesis in the BM, resulting in a systemic increase in myeloid cells, and lung IMs—but not AMs—are trained by WGP.

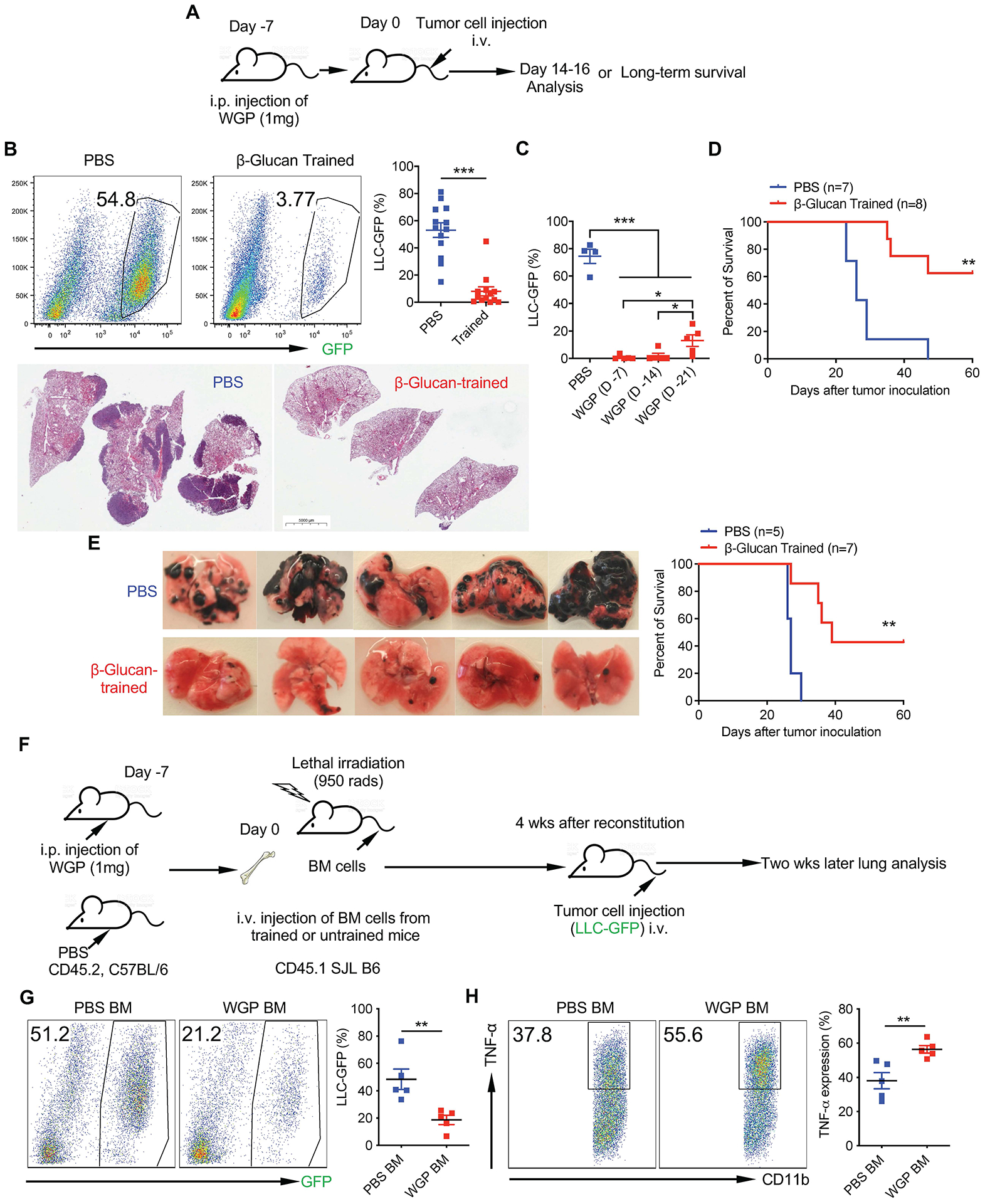

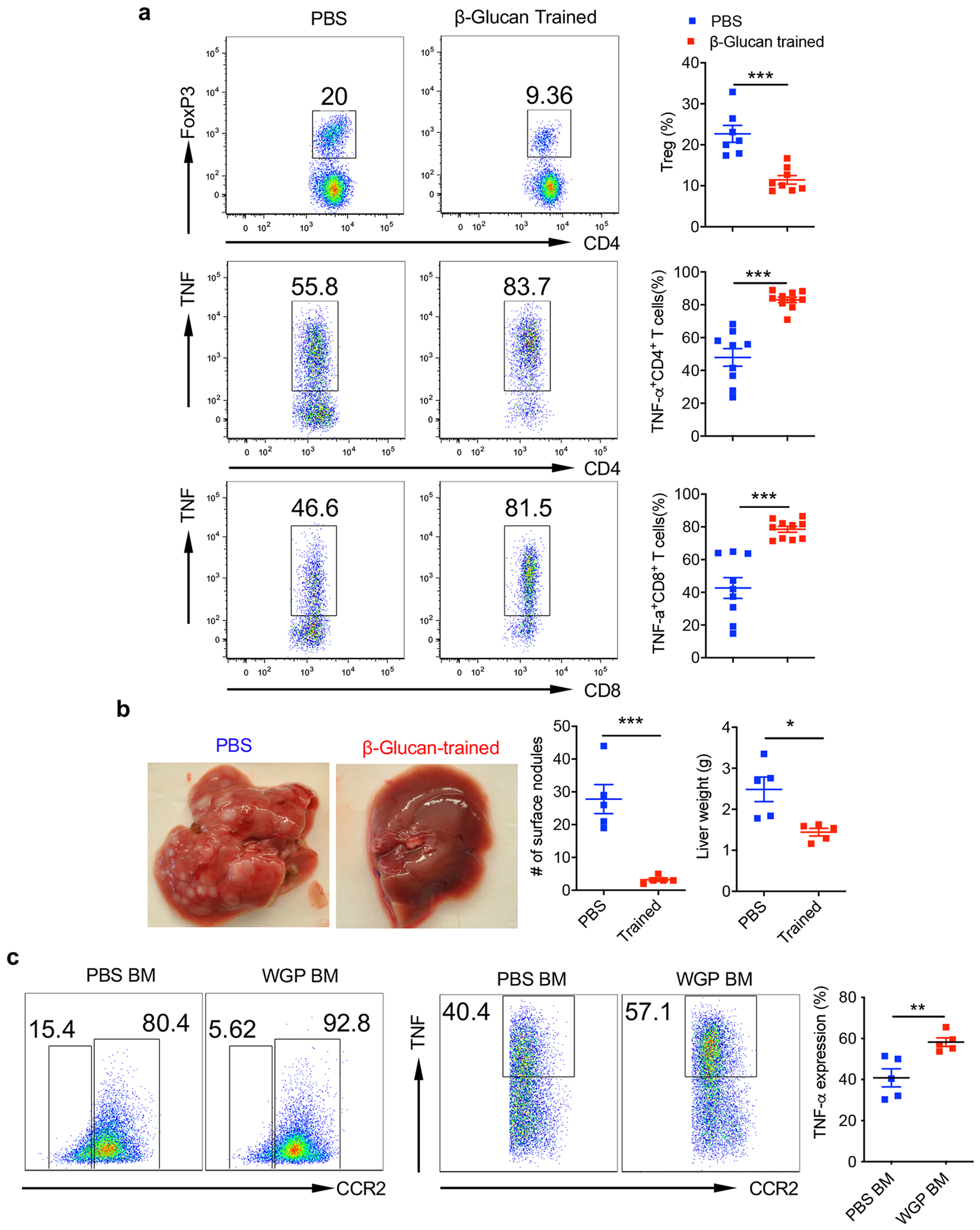

Whole beta-glucan particle-induced trained immunity reduces metastases and prolongs survival

Because WGP-trained lung IMs elicit trained responses against tumor-derived factors, we hypothesized that inducing trained immunity may control tumor metastasis in the lungs. Accordingly, mice trained with or without WGP were intravenously (i.v.) injected with GFP-tagged LLC (LLC-GFP) cells to determine tumor burden in the lungs and long-term survival (Fig. 3a). WGP-trained mice had a significantly reduced tumor burden in the lungs as compared to PBS controls. The histopathology analysis of lung sections also showed increased tumor nodules in control lung sections and few to none in the lungs of WGP-trained mice (Fig. 3b). Given that short-term memory is one of the hallmarks of trained immunity31, we set out to determine how long the WGP-mediated trained effect lasted. Mice were trained with WGP at days −7, −14 and −21 followed by LLC-GFP injection. WGP-treated mice had significantly reduced tumor burden compared to untrained mice (Fig. 3c). However, there was a marked increase in the tumor burden in mice trained at day −21 compared to the mice treated at days −7 and −14. WGP training also led to a decrease in the frequency of regulatory T (Treg) cells and an increase in the frequency of TNF-expressing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the lungs (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Long-term survival studies revealed a significantly prolonged survival in mice trained with WGP compared to PBS controls (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3 |. Whole beta-glucan particle-induced trained response inhibits metastasis.

a, Schema for in vivo WGP training and tumor challenge. b, Six-week-old C57BL/6 mice trained with PBS (n = 13) and WGP (n = 13) were injected with 0.4 × 106 LLC-GFP cells i.v. and tumor burden in the lungs was analyzed 14–16 d after tumor challenge by flow cytometry. Representative dot plots and summarized percentage of LLC-GFP cells in the CD45− population in the lungs are shown (up). Data are representative of two individual experiments combined. Histological analysis of the lungs from LLC-GFP tumor-bearing mice trained with PBS (n = 3) versus WGP (n = 3; down). c, Summarized frequencies of LLC-GFP cells in the lungs from tumor-bearing PBS versus WGP-trained mice. Mice were trained with PBS (n = 4) or WGP on days −7 (n = 5), −14 (n = 5) and −21 (n = 5), before tumor challenge. d, Long-term survival of mice trained with PBS (n = 7) versus WGP (n = 8) injected with 0.2 × 106 LLC-GFP cells i.v. on day 0. e, Six-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were trained at day −7, challenged with i.v. injections of 0.4 × 106 B16F10 tumor cells at day 0 and the lungs were collected at day 16 (left). Representative lung micrographs from PBS-trained (n = 5) versus WGP-trained (n = 5) B16F10 tumor-bearing mice. Black dots are melanoma lung metastasis nodules. Long-term survival of PBS-trained (n = 5) and WGP-trained (n = 7) mice challenged with B16F10 tumor cells (0.1 × 106; right). f, Schema for BM chimeric experiment. g, Tumor burden (LLC-GFP) from recipient mice reconstituted with BM cells from WGP-trained (n = 5) or PBS control (n = 5) mice. Representative flow plots and summarized data are shown. h, Intracellular TNF production in lung IMs from mice reconstituted with BM cells from WGP-trained or PBS control mice. Data are representative of two independent experiments and presented as the mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. P values were derived from an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test for b, g and h, a one-way ANOVA for c and a Kaplan–Meier plot for d and e.

To validate that WGP-mediated trained immunity and metastasis inhibition are not specific only to an LLC model, a melanoma lung metastasis model was used. Mice trained with WGP had substantially reduced tumor metastases compared to PBS controls (Fig. 3e). WGP training prolonged the survival of B16F10 challenged mice (Fig. 3e). We also used a liver metastasis model whereby mice were i.v. injected with EL4. Previous studies have shown that EL4 lymphoma i.v. injection leads to liver metastasis32. WGP-trained mice showed a significantly reduced number of tumor nodules that were accompanied by reduced total liver weights (Extended Data Fig. 4b), emphasizing the systemic benefit of WGP-mediated trained immunity.

As we showed that BM-derived CCR2+ IMs bear the trained immunity phenotype, we next examined whether the progenitor cells in the BM maintain their trained immunity upon adoptive transfer. To this end, BM cells from WGP-trained or untrained mice were adoptively transferred into lethally irradiated recipient mice. After BM reconstitution, mice were challenged with LLC-GFP (Fig. 3f). Mice reconstituted with BM cells from WGP-trained mice had significantly reduced tumor burden compared to those that received BM cells from untrained mice (Fig. 3g), and lung IMs maintained a trained immunity phenotype in these mice (Fig. 3h). Interestingly, the majority of lung IMs (80–90%) in the recipient mice expressed CCR2 and were derived from donors and these CCR2+ IMs exhibited trained immunity (Extended Data Fig. 4c). These data suggest that the induction of trained immunity effectively controls tumor metastasis.

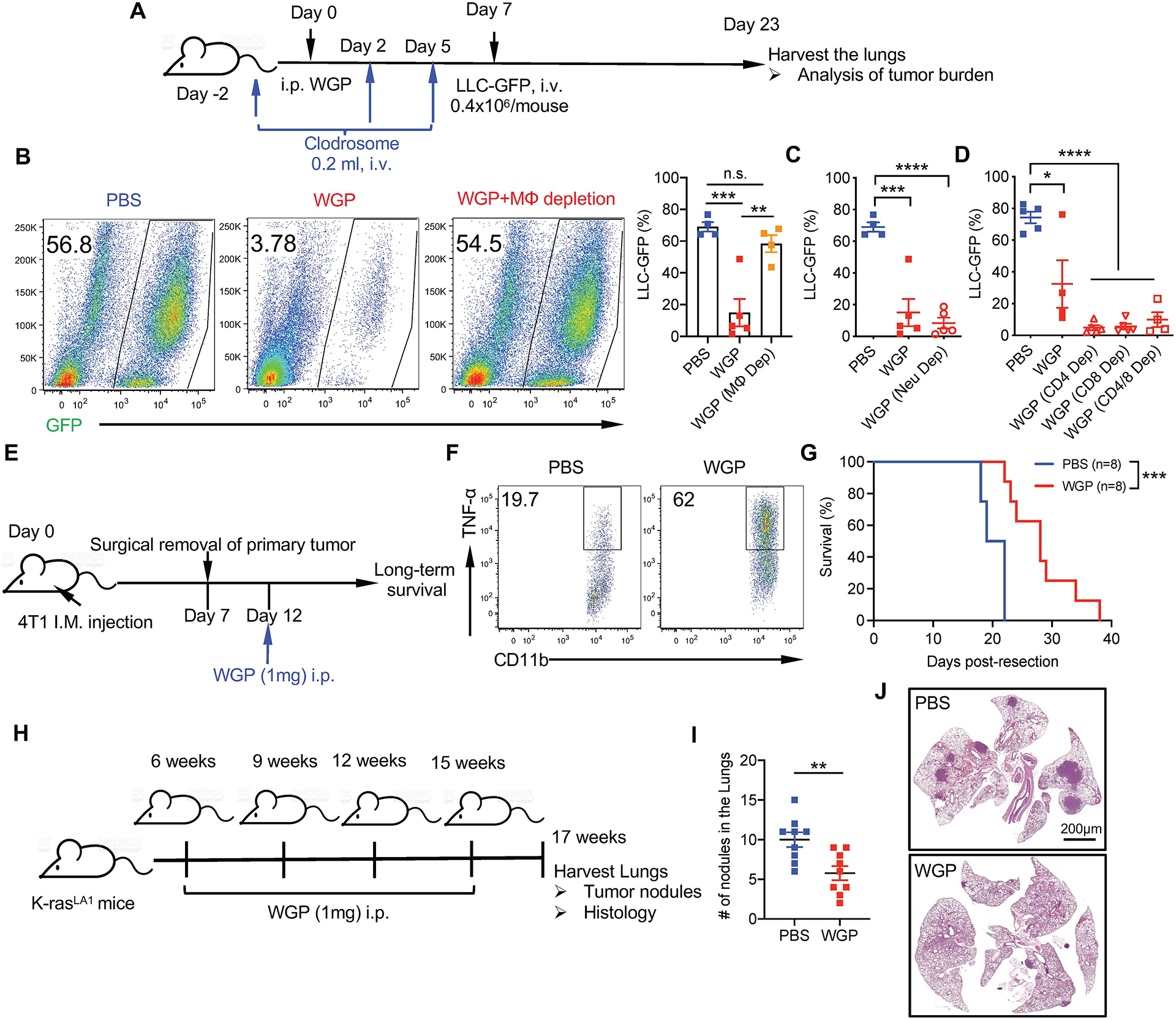

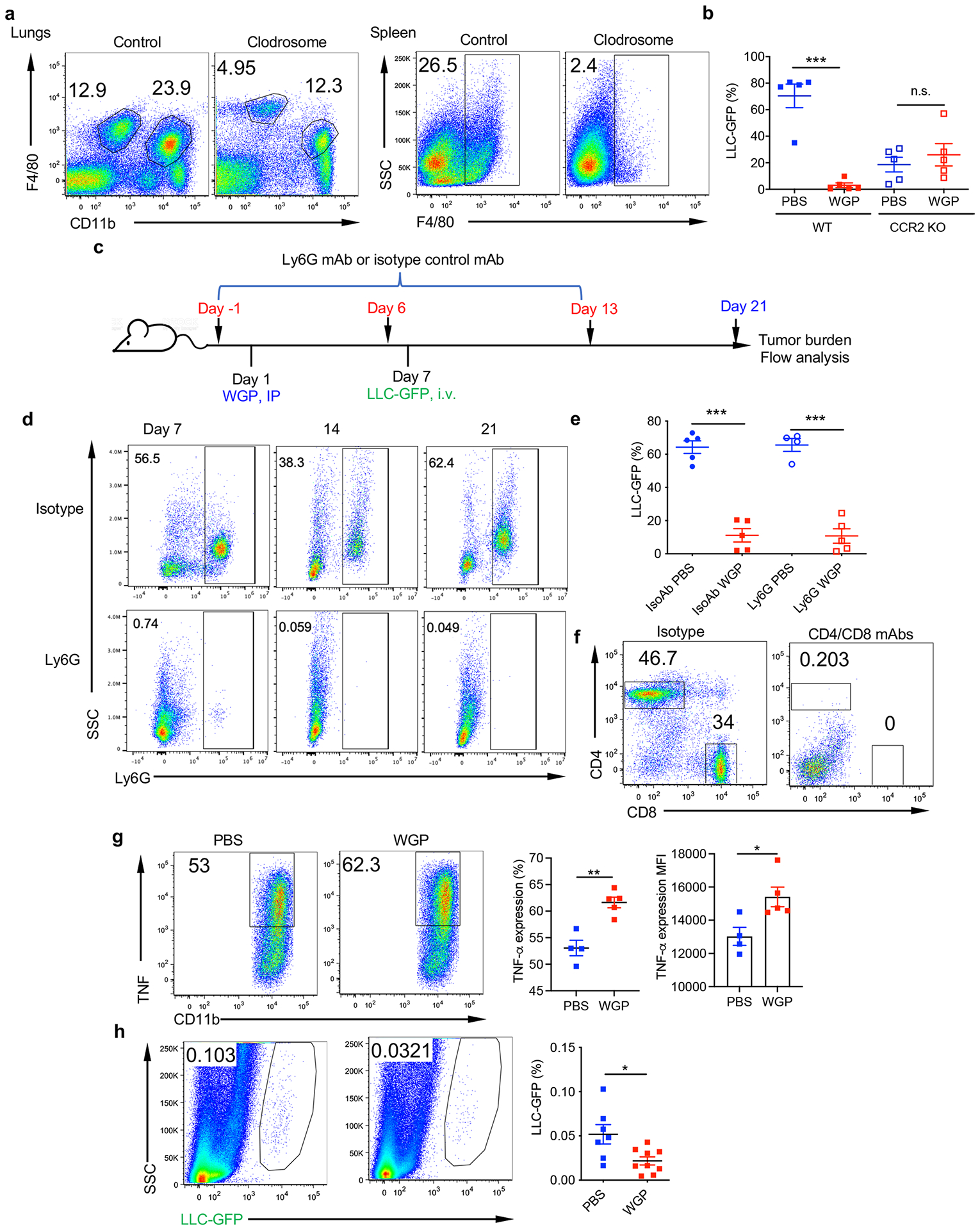

Whole beta-glucan particle-trained lung interstitial macrophages inhibit metastasis and tumor development

To determine whether WGP-trained IMs are the effector cells that control metastasis, we depleted macrophages with clodronate liposome (Clodrosome; Fig. 4a). Depletion efficiency is shown in Extended Data Fig. 5a. Depletion of macrophages resulted in significantly increased tumor burden comparable to PBS controls (Fig. 4b). In addition, WGP-mediated lung metastasis control in WT mice was abrogated in CCR2 KO mice (Extended Data Fig. 5b), suggesting that BM-originated lung IMs are the primary effector cells that control cancer lung metastasis. To determine whether neutrophils are involved in this process, as a recent study emphasized the role of trained immunity-mediated granulopoiesis in an antitumor phenotype15, neutrophils were depleted before and during WGP training. No differences were observed in the lung tumor burden between neutrophil intact and deficient WGP-trained mice (Fig. 4c). We also depleted neutrophils during the entire tumor protocol (Extended Data Fig. 5c). Neutrophils were effectively depleted (Extended Data Fig. 5d). However, depletion of neutrophils did not alter WGP-mediated lung tumor metastasis control (Extended Data Fig. 5e). To examine whether adaptive CD4+/CD8+ T cells are essential in WGP-induced trained immunity, CD4+ and/or CD8+ T cells were depleted during the WGP training period. Depletion efficiency is shown in Extended Data Fig. 5f. Depletion of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, or both, did not affect WGP-mediated lung tumor metastasis inhibition (Fig. 4d). To validate these findings, NSG mice, which lack mature T cells, B cells and NK cells, were used. WGP induced trained immunity in NSG lung IMs (Extended Data Fig. 5g). NSG mice trained with WGP had less tumor burden in the lungs compared to untrained mice (Extended Data Fig. 5h), suggesting that WGP-mediated training and metastasis control are not dependent on neutrophils and adaptive T and B cells.

Fig. 4 |. Whole beta-glucan particle-trained lung interstitial macrophages inhibit metastasis and lung cancer.

a, Schema for in vivo macrophage depletion by Clodrosome, WGP training, and tumor challenge in 6 weeks old C57BL/6 mice. b, Tumor burden in the lungs of PBS-trained (n = 4), WGP-trained (n = 5) and WGP-trained macrophage-depleted mice (n = 4) injected with 0.4 × 106 LLC-GFP cells 16 d after tumor challenge. Representative dot plots and summarized data are shown. c, Tumor burden in the lungs of PBS-trained (n = 4), WGP-trained (n = 5) and neutrophil-depleted WGP-trained (n = 5) mice. d, Tumor burden in the lungs of PBS-trained (n = 5), WGP-trained (n = 4) mice versus WGP-trained CD4+ T cell-depleted (n = 5), WGP-trained CD8+ T cell-depleted (n = 5) or WGP-trained CD4+ and CD8+ T cell-depleted mice (n = 4) mice. e, Schema for 4T1 primary mammary tumor resection and WGP treatment protocol. Six-week-old female Balb/c mice were implanted with 0.1 × 106 4T1 tumor cells on the fourth mammary pad. Tumors were surgically resected after a week and mice were treated with PBS or WGP 5 d after resection. Long-term survival was monitored. f, Intracellular TNF expression on lung IMs after ex vivo LPS restimulation of PBS and WGP-trained Balb/c mice. g, Long-term survival of PBS (n = 8) and WGP-trained (n = 8) 4T1 tumor resected Balb/c mice. h, Schema for in vivo treatment of 4T1 primary mammary cancer model. i, Representative lung histology and summarized lung tumor nodules from WGP-treated (n = 5) or untreated (n = 6) mice. j, Schema for in vivo treatment of spontaneous K-rasLA1 mice. K-rasLA1 mice were injected with WGP (1 mg, i.p.) or PBS at 6, 9, 12 and 15 weeks of age and euthanized at 17 weeks to analyze tumor development in the lungs. k, Number of lung tumor nodules of PBS (n = 9) versus WGP-treated (n = 9) K-rasLA1 mice. Combined data from three independent experiments are shown. l, Representative histology of lungs of PBS versus WGP-treated K-rasLA1 mice. Data are representative of two independent experiments and presented as the mean ± s.e.m. NS, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. P values were derived from one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple correction for b–d, a Kaplan–Meier plot for g and an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test for i and k. i.m., intramuscular.

We next used a clinically relevant model where the triple-negative breast cancer cell line 4T1 was orthotopically implanted into female Balb/c mice. When tumor size reached 2–3 mm in diameter, primary tumors were surgically excised. Mice were then treated with WGP and long-term survival was monitored (Fig. 4e). Because Balb/c mice are genetically distinct from C57BL/6 mice, we confirmed the in vivo trained phenotype of lung IMs in this strain (Fig. 4f). Mice treated with WGP showed a prolonged survival as compared to controls (Fig. 4g), indicating that WGP can be used in an adjuvant setting to reduce lung metastasis. We also used WGP in the treatment setting. Mice were first orthotopically implanted with 4T1 cells and received one dose of WGP treatment 5 d after tumor injection (Fig. 4h). WGP treatment significantly reduced lung metastasis (Fig. 4i). To further investigate the use of WGP in a therapeutic setting, we used a genetically engineered mouse model of lung cancer. K-rasLA1 mutated mice spontaneously develop lung tumor nodules starting at 4 months of age33. Taking this tumor development and the short-lived nature of WGP-mediated trained immunity into consideration, we developed a treatment protocol where K-rasLA1 mice were trained with WGP starting at 6 weeks of age and repeated every 3 weeks (9, 12 and 15 weeks). At 17 weeks, mice were euthanized to examine lung tumor nodules (Fig. 4j). WGP-treated mice had significantly fewer lung tumor nodules as compared to untreated controls (Fig. 4k). Histological analysis of the lungs also confirmed this phenotype (Fig. 4l). These results suggest a therapeutic benefit of WGP-mediated trained immunity in controlling lung tumor development and metastasis.

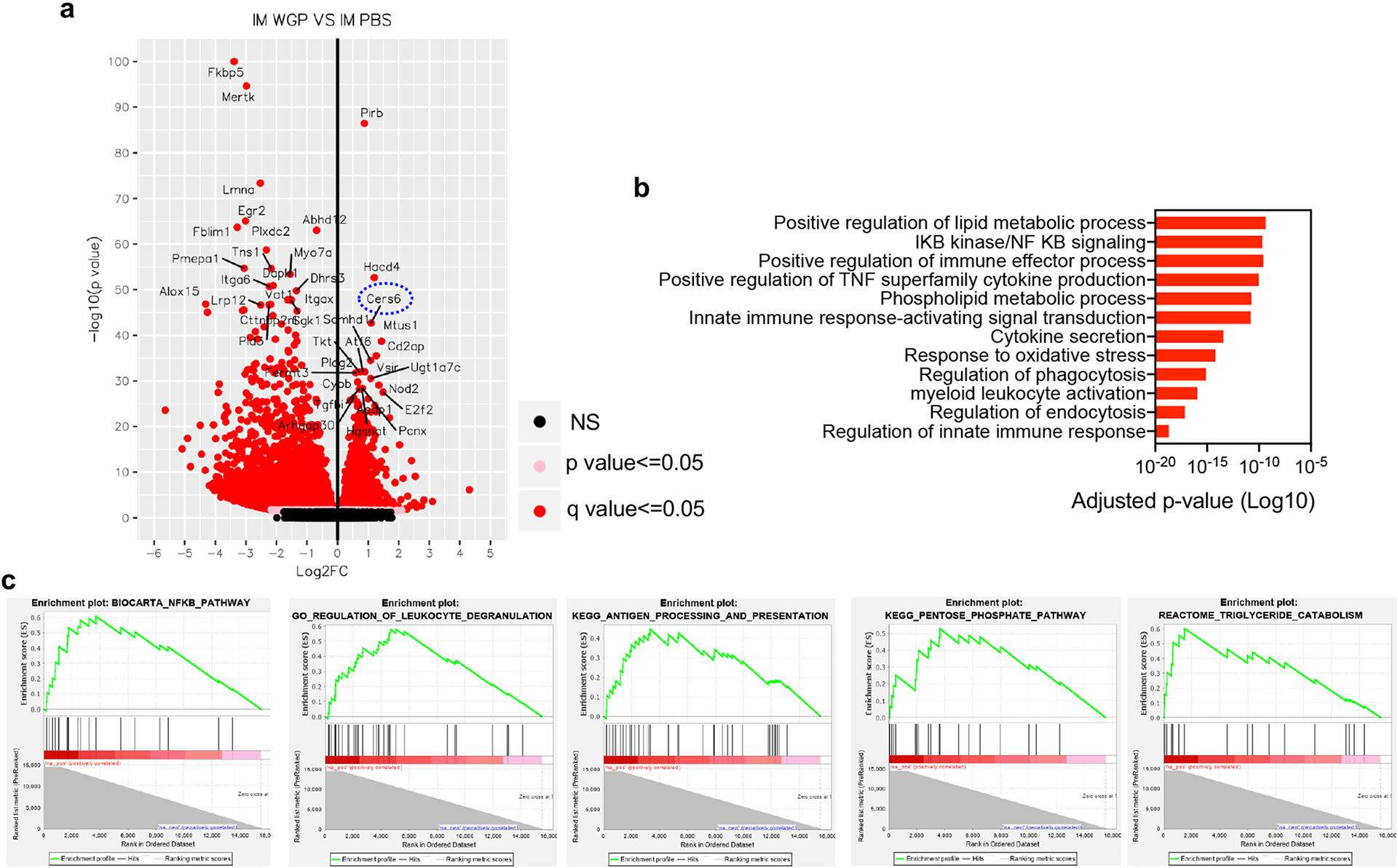

Whole beta-glucan particle training augments lung interstitial macrophage phagocytosis and cytotoxicity

To understand the mechanistic basis of WGP-induced trained immunity and inhibition of tumor metastasis, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) on lung IMs from WGP-trained or control mice. RNA-seq analysis revealed a significant number (total 3,417) of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in WGP-trained lung IMs compared to PBS controls (Extended Data Fig. 6a). Ingenuity pathway analysis highlighted pathways involved in innate immune function including phagocytosis, cytokine secretion, the NF-κB pathway and the oxidative stress and metabolic pathways (Extended Data Fig. 6b). Gene-set enrichment analysis (GSEA) also showed a significant enrichment of innate immune effector functions in IMs from WGP-trained mice (Extended Data Fig. 6c). Phagocytosis-related genes were significantly enriched in WGP-trained lung IMs (Fig. 5a). We then performed a phagocytosis assay using pHrodo-green-labeled Staphylococcus aureus. Lung IMs, but not AMs from WGP-trained mice, exhibited significantly increased phagocytosis compared to those from PBS control mice (Fig. 5b), indicating that WGP training increases lung IM phagocytic capacity.

Fig. 5 |. Whole beta-glucan particle training increases phagocytic and cytotoxic activity of lung interstitial macrophages.

a, GSEA plot for the regulation of phagocytosis and heat map for the genes related to the phagocytosis regulation pathway. NES, normalized enrichment score. b, Phagocytosis assay was performed with lung AMs and IMs from WGP-trained (n = 4) or PBS control (n = 4) mice. Phagocytosis of pHrodo-green-labeled S. aureus was analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative dot plots and summarized data are shown. c, In vitro cytotoxicity assay using sorted lung IMs from PBS control (n = 3) or WGP-trained (n = 3) mice and co-cultured with LLC cells at different ratios. Cells were cultured for 16 h and cytotoxicity was measured by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay. d, In vivo cytotoxicity assay. Six-week-old C57BL/6 PBS control (n = 5) and WGP-trained (n = 5) mice were i.v. injected with 1 × 106 LLC-GFP cells and were analyzed for the frequency of LLC-GFP cells in the lungs after 24 h. Representative dot plots and summarized data are shown. e, GSEA plot for ROS biosynthetic process and heat map for the related leading genes in the WGP-trained lung IMs. f, MitoSox Red staining for PBS and WGP-treated peritoneal macrophages. Peritoneal macrophages were treated with PBS (n = 8) or WGP (n = 9) for 24 h and then stained with MitoSox Red and analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative histogram and summarized data from two independent experiments are shown. g, Lung IMs sorted from WGP-trained mice (n = 3) were co-cultured with LLC target cells in the presence or absence of Mito-TEMPO at a 10:1 ratio. Cytotoxicity was measured by the LDH release assay. Data are representative of two independent experiments and presented as the mean ± s.e.m. For a and e, nominal P values were used to determine significance. When the nominal P value is represented as 0, this means P < .0001. The nominal P value was calculated by empirical phenotype-based permutation test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001. P values were derived from an unpaired two-tailed student’s t-test for b, d and f, a two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test for c and a one-way ANOVA for g.

We next performed a cytotoxicity assay by co-culturing sorted lung IMs with LLC cells. WGP-trained IMs exhibited increased cytotoxicity compared to untrained PBS controls (Fig. 5c). To determine if this effect occurs in vivo, PBS-trained versus WGP-trained mice were injected with LLC-GFP cells i.v. and euthanized after 24 h. WGP-trained mice showed a significantly reduced frequency of LLC-GFP cells in the lungs compared to PBS controls (Fig. 5d), suggesting that WGP-mediated training reduces tumor dissemination in the lungs.

One of the enriched pathways from our GSEA analysis was the reactive oxygen species (ROS) biosynthetic pathway (Fig. 5e). To understand if generation of ROS is an underlying mechanism for cytotoxicity of WGP-trained lung IMs, WGP-trained macrophages were detected for mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) using MitoSox Red staining. WGP treatment increased mtROS production (Fig. 5f). Addition of mitochondria-targeted antioxidant Mito-TEMPO inhibited the cytotoxicity of WGP-trained IMs (Fig. 5g). Taken together, these results suggest that WGP-induced lung IM trained immunity results in increased phagocytosis and cytotoxicity to tumor cells.

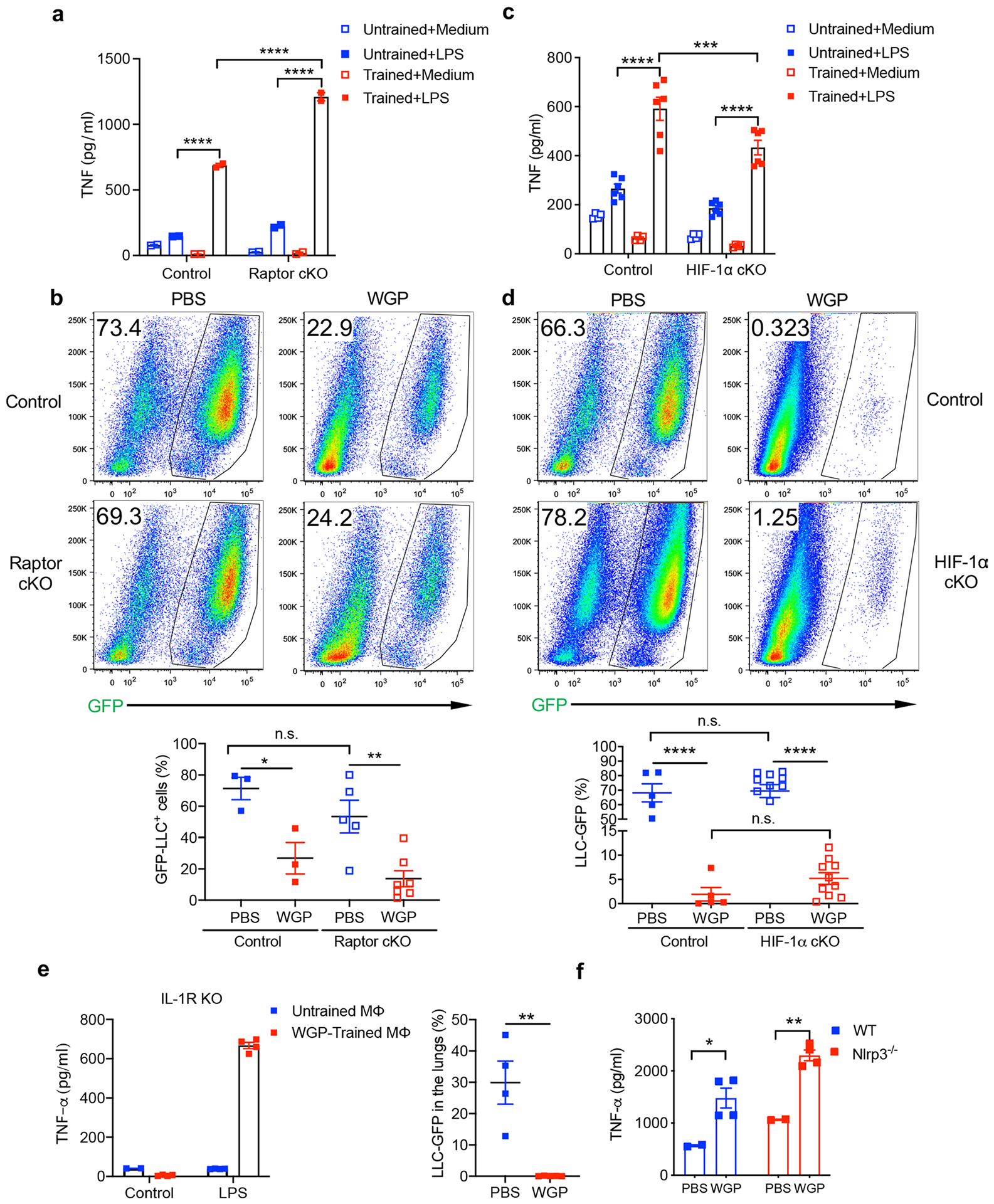

Sphingolipid synthesis is critical for lung interstitial macrophage-trained immunity

Activation of mammalian/mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) through a hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) pathway-mediated aerobic glycolysis is a well-established mechanism for inducing trained immunity10,34. We thus generated myeloid cell conditional knockout mouse (cKO) models for Raptor (mTORC1), Rictor (mTORC2) and HIF-1α. Peritoneal macrophages from Raptor cKO mice trained with WGP showed an increased TNF response after LPS restimulation (Extended Data Fig. 7a). In addition, WGP-trained control and Raptor cKO mice showed a similar level of reduced tumor burden (Extended Data Fig. 7b). Similar results were observed in Rictor cKO mice. A similar in vitro training experiment was performed using macrophages from HIF-1α cKO mice and an increased TNF response was observed in macrophages of WGP-trained HIF-1α cKO mice. However, TNF levels from WGP-trained HIF-1α cKO macrophages were lower than those in control mice (Extended Data Fig. 7c), suggesting that WGP-mediated trained immunity is partially dependent on the HIF-1α pathway. Despite this, HIF-1α cKO mice were able to reduce lung metastases upon WGP training and was comparable to WGP-trained control mice (Extended Data Fig. 7d). These data suggest that the HIF-1α pathway is not essential in WGP training-mediated metastasis inhibition.

Beta-glucan-mediated interleukin (IL)-1β signaling has also been implicated in the proliferation of HPSCs and myelopoiesis25,35,36. We performed both in vitro training and in vivo training-tumor challenge experiments using IL-1R global KO mice. Upon WGP training, macrophages from IL-1R KO mice produced higher TNF compared to untrained controls. IL-1R KO mice trained with WGP also significantly inhibited lung metastasis (Extended Data Fig. 7e), indicating that IL-1R signaling is not critical for WGP-mediated training and metastasis inhibition. Along this line, there was no significant difference in TNF levels between WGP-trained WT and Nlrp3 KO macrophages (Extended Data Fig. 7f). The Nlrp3 inflammasome pathway is upstream of IL-1β and important for the transcription and expression of IL-1β36,37. These results emphasize that WGP-mediated trained immunity is not dependent on the IL-1β–IL-1R pathway.

To examine other possible signaling pathways responsible for WGP-mediated trained immunity, we further analyzed our RNA-seq data and found that one of the most upregulated genes expressed by WGP-trained IMs is ceramide synthase 6 (Cers6; Extended Data Fig. 6a), a gene in the sphingolipid synthesis pathway. Many other genes involved in sphingolipid synthesis pathways were also upregulated in WGP-trained IMs (Fig. 6a). Quantitative PCR with reverse transcription (RT–qPCR) analysis confirmed that Cers6 and sphingosine kinase-2 (Sphk2) mRNA levels were increased in WGP-trained lung IMs (Fig. 6b). We next examined whether inhibition of ceramide synthase has any effect on WGP-mediated trained immunity. Addition of ceramide synthase inhibitor fumonisin-B1 abrogated WGP-mediated trained immunity (Fig. 6c). Ceramide can be synthesized through a de novo synthesis pathway where serine and palmitoyl-CoA undergo a series of reactions to produce ceramide or through a salvage pathway using sphingosine (Fig. 6b). Breakdown of ceramide via ceramidases yields sphingosine, which can be phosphorylated via sphingosine kinases (Sphk1 or Sphk2) to produce sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P)37,38. Addition of a specific Sphk2 inhibitor (Sphk2i) attenuated the trained responses (Fig. 6d), suggesting that production or accumulation of S1P but not ceramide itself is important for WGP-stimulated trained immunity. To further establish the role of S1P in the WGP-mediated trained immunity, we measured S1P abundance by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS). WGP-trained macrophages showed an increased S1P abundance compared to PBS controls (Fig. 6e). Macrophages trained with S1P showed higher TNF production compared to the untrained controls (Fig. 6f). S1P-trained macrophages also exhibited an enhanced mtROS production (Fig. 6g). Previous studies have shown that S1P induces mtROS through the activation/phosphorylation of dynamin-related protein-1 (Drp-1), translocation of Drp-1 to the mitochondria and subsequent mitochondrial fission38,39. Treatment with S1P resulted in increased phosphorylated Drp-1 (p-Drp-1) in macrophages (Fig. 6h). Addition of a selective Drp-1 inhibitor Mdivi-1 abrogated S1P-induced trained immunity (Fig. 6i), suggesting that mitochondrial fission may play a critical role in WGP-mediated trained immunity. However, whether such mechanisms are retained upon exposure to the tumor milieu remains unknown.

Fig. 6 |. Whole beta-glucan particle treatment activates sphingolipid synthesis in macrophages.

a, Heat map for the genes upregulated in the sphingolipid synthesis pathway in the WGP-trained lung IMs. b, Detailed schema for the sphingolipid synthesis pathway and RT–qPCR for CerS6 and Sphk2 mRNA expression in PBS (n = 4) and WGP-trained lung IMs (n = 4). c, TNF production by WGP-trained or untrained peritoneal macrophages in the presence of fumonisin-B1 (25 μM) or vehicle control DMSO. Peritoneal macrophages were trained with WGP in the presence of fumonisin-B1 or DMSO for 7 d and restimulated with LPS (n = 2 versus 3) or LLC culture supernatants (n = 3 versus 3). d, TNF production by WGP-trained (n = 2) or untrained peritoneal macrophages (n = 2) in the presence of Sphk2i (25 μM or 50 μM) or DMSO upon LPS or LLC culture supernatant restimulation. e, Representative mass spectrometry measurement of S1P in the in vitro WGP-trained or untrained peritoneal macrophages. One representative from three independent experiments with similar data. f, TNF production by S1P-trained (n = 3) versus untrained peritoneal macrophages (n = 3) after LPS or LLC culture supernatant restimulation. g, MitoSox Red staining on PBS (n = 3) versus S1P-trained peritoneal macrophages (n = 5) was analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative histogram and summarized data are shown. h, The p-Drp-1 expression in S1P-stimulated peritoneal macrophages assessed by flow cytometry. i, TNF production by S1P-trained (n = 2) versus untrained peritoneal macrophages (n = 2) in the presence of Mdivi-1 or vehicle control after LPS restimulation. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments and presented as the mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. P values were derived from an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test for b, g and h and two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test for c, d, f and i.

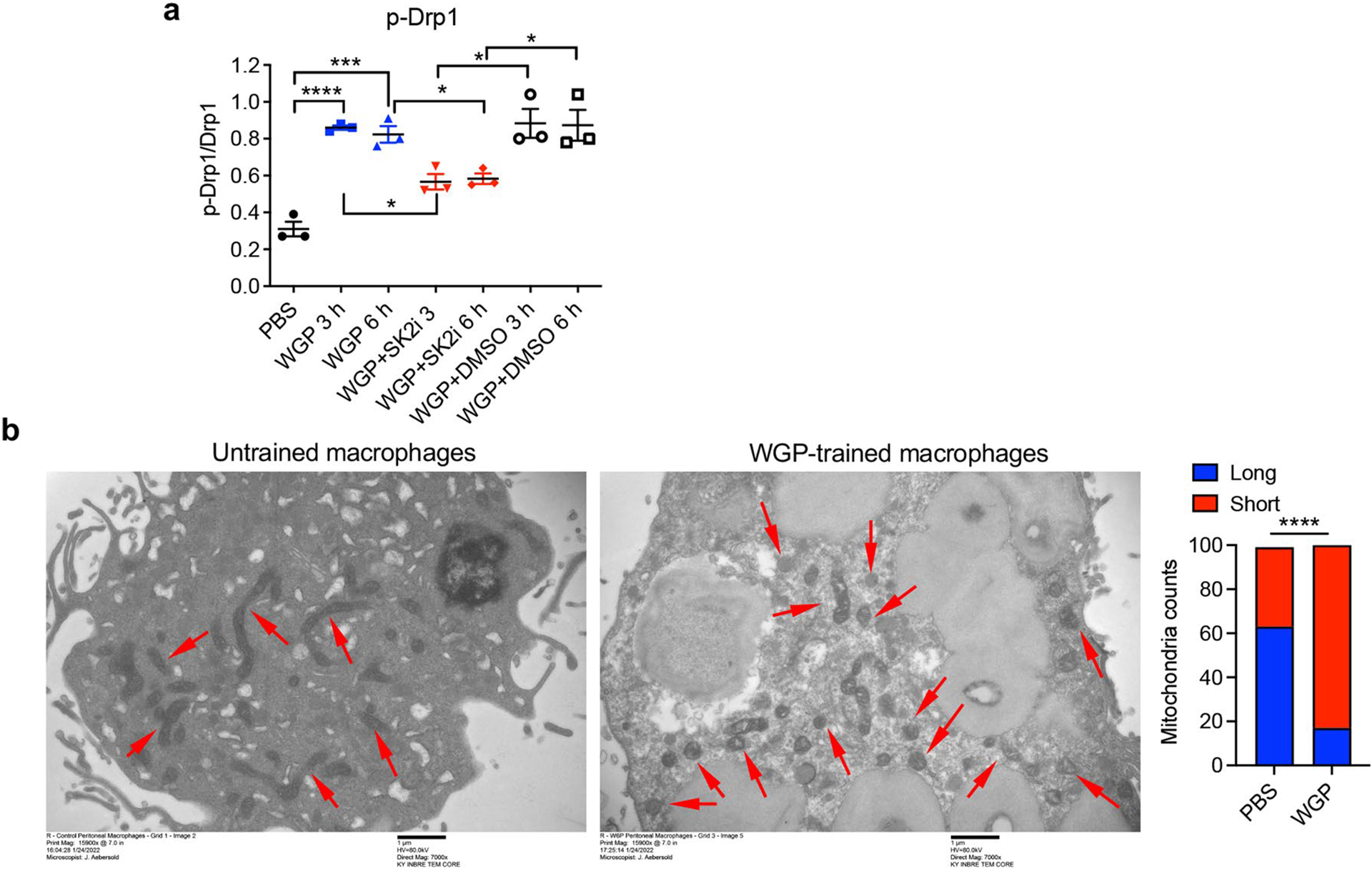

Mitochondrial fission in trained immunity and metastasis inhibition

To examine the role of mitochondrial fission in WGP-mediated trained immunity, we assessed p-Drp-1 levels in WGP-trained macrophages. WGP-trained macrophages showed a significant phosphorylation of Drp-1 (Fig. 7a and Extended Data Fig. 8a). Addition of Sphk2i decreased the level of p-Drp-1 but not total Drp-1. WGP-mediated mitochondrial fission was also detected by staining macrophages with a cell membrane permeable dye Tetra-methyl-rhodamine methyl ester (TMRM). Confocal microscopy analysis revealed that WGP training resulted in mitochondrial fragmentation. Addition of Mdivi-1 diminished WGP-induced mitochondrial fragmentation (Fig. 7b). WGP training-induced mitochondrial fission in macrophages was also revealed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM; Extended Data Fig. 8b). Inhibition of mitochondrial fission by Mdivi-1 abrogated WGP-mediated trained responses (Fig. 7c) and mtROS production (Fig. 7d) as well as cytotoxicity (Fig. 7e), which suggests critical roles of mitochondrial fission in the WGP-induced trained immunity in vitro.

Fig. 7 |. Mitochondrial fission is critical for training of lung interstitial macrophage control over metastasis.

a, Peritoneal macrophages were treated with PBS or WGP (50 μg ml−1) in the presence of Sphk2i (50 μM) or DMSO for 3 h and 6 h. The level of p-Drp-1 and total Drp-1 was determined by western blot. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments. b, Mitochondrial fission in PBS and WGP-trained versus WGP + Mdivi-1 (10 μM)-treated peritoneal macrophages. Macrophages were stained with TMRM and analyzed by confocal microscopy. The mitochondrial lengths were analyzed by ImageJ. Representative images and summarized data of one of two independent experiments are shown. Scale bar, 10 μm. c, TNF levels by PBS (n = 2) and WGP-trained peritoneal macrophages (n = 2) in the presence of Mdivi-1 (10 μM) or DMSO after LPS and LLC culture supernatant restimulation. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments. d, MitoSox Red staining on PBS (n = 2) and WGP-trained peritoneal macrophages (n = 3) in the presence of Mdivi-1 (50 μM and 75 μM) using flow cytometry. Representative histogram and summarized data from one of the two independent experiments are shown. e, Cytotoxicity of PBS (n = 3) and WGP-trained peritoneal macrophages (n = 3) in the presence of Mdivi-1 (10 μM) or DMSO co-cultured with LLC target cells at a ratio of 10:1 using the LDH release assay. f, Schema for Mdivi-1 in vivo treatment and tumor challenge. g, Tumor burden in the lungs from mice trained with or without WGP along with Mdivi-1 (n = 12, 13) or DMSO (n = 8, 11) treatment. Representative dot plots and summarized data from two independent experiments are shown. h,i, viSNE analysis of CyTOF immunophenotyping of the lungs from mice trained with or without WGP and treated with Mdivi-1 or DMSO (n = 4). All samples combined (h), combined samples from each group (i, top), and frequencies in different groups (i, bottom). j, The ratios of CD8+ T cells to F4/80+CD11b+ and CD11b+PD-L1+ myeloid cells are shown. Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. P values were derived from two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test for c; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test for d, e, g and j.

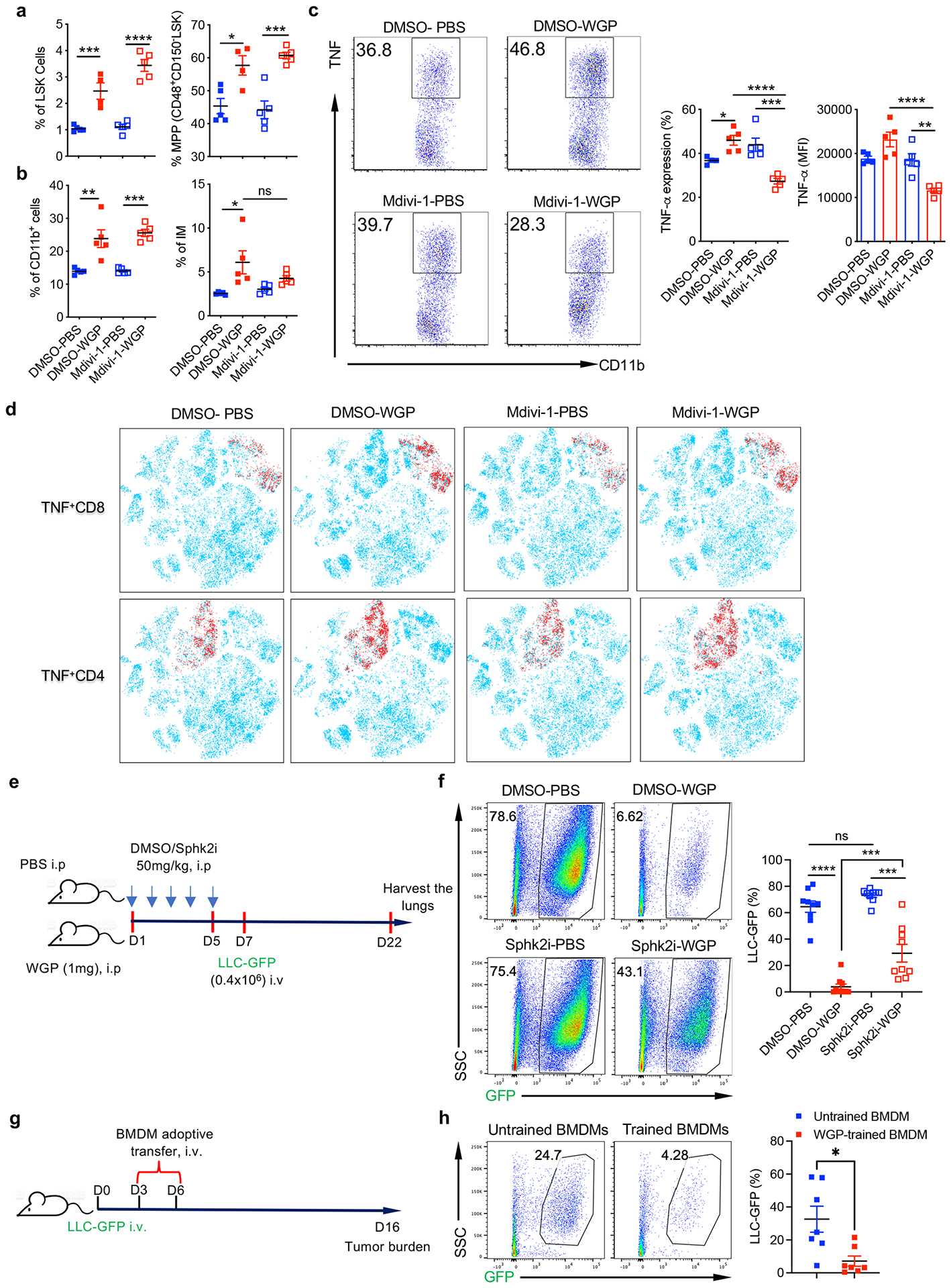

To determine the role of mitochondrial fission in WGP-mediated trained immunity in vivo, mice were trained with WGP along with treatment of Mdivi-1 or vehicle control. BM analysis revealed an expansion of both LSK cells and MPPs in WGP-trained Mdivi-1-treated and dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)-treated mice compared to respective untrained controls (Extended Data Fig. 9a). There was no significant difference between WGP-trained DMSO-treated or Mdivi-1-treated mice. Similarly, analysis of the lungs also did not show any difference in frequencies of CD11b+ cells and IMs in these mice (Extended Data Fig. 9b). Mdivi-1 treatment therefore did not affect WGP-mediated accumulation of myeloid cells in the lungs. Strikingly, the lung IM training phenotype was abrogated in WGP-trained mice treated with Mdivi-1 (Extended Data Fig. 9c).

We next examined whether inhibition of mitochondrial fission also impacts cancer lung metastasis. To this end, mice were trained with WGP along with treatment of Mdivi-1 or vehicle control followed by LLC-GFP injection (Fig. 7f). WGP-trained mice treated with vehicle control showed significantly lower tumor burdens compared to untrained mice (Fig. 7g). However, there was no difference in the tumor burden between WGP-trained mice treated with Mdivi-1 and untrained mice, suggesting that loss of lung IM training in the presence of Mdivi-1 fails to control tumor metastasis. We also profiled both innate and adaptive T cells and B cells within the lung by the mass cytometer (Fig. 7h). Although the frequencies of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were not changed in WGP-trained mice, the frequencies of PD-1+CD4+ and PD-1+CD8+ T cells were decreased, while Mdivi-1 treatment abolished this effect (Fig. 7i). In contrast, both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells produced more TNF in WGP-trained mice (Extended Data Fig. 9d). In addition, the PD-L1+/CD206+ macrophages and PD-L1+ macrophages (clusters 5 and 8) were decreased in WGP-trained mice, and this effect was abolished when mice were treated with Mdivi-1 (Fig. 7i). Consequently, the ratios of CD8+ T cells to these myeloid cells (CD11b+F4/80+ and PD-L1+CD11b+) were increased in WGP-trained mice (Fig. 7j). A similar protocol was performed with Sphk2i (Extended Data Fig. 9e). Mice trained with WGP had substantially reduced tumor burden in the lungs compared to untrained mice (Extended Data Fig. 9f). Sphk2i treatment did not change tumor burden in untrained mice compared to vehicle control-treated mice. However, Sphk2i treatment significantly increased tumor burden in the lungs compared to vehicle treatment in WGP-trained mice (Extended Data Fig. 9f), although these mice still had lower tumor burden compared to untrained mice. Taken together, these results indicate that sphingosine–mitochondrial fission is essential for WGP-mediated lung IM trained immunity and in vivo cancer metastasis control.

Mitochondrial fission is essential for bone marrow-derived macrophage-trained immunity

As inhibition of mitochondrial fission did not influence WGP-stimulated BM myelopoiesis, we next examined whether central trained immunity is impacted by mitochondrial fission inhibition. Mice trained with or without WGP received Mdivi-1 or vehicle treatment in vivo. On day 6, BM cells were harvested for bone marrow-derived macrophage (BMDM) differentiation (Fig. 8a). BMDMs differentiated from WGP-trained mice showed enhanced TNF production (Fig. 8b). Mdivi-1 in vivo treatment abrogated the trained immunity phenotype in BMDMs. We also measured oxygen consumption rate (OCR), which detects mitochondrial respiration. WGP-trained BMDMs exhibited higher basal OCR and maximal respiratory capacity compared to untrained BMDMs (Fig. 8c). Mdivi-1 treatment decreased basal OCR but did not alter maximal mitochondrial respiration or spare capacity in untrained BMDMs (Fig. 8d). In contrast, Mdivi-1 treatment drastically reduced basal OCR, proton-linked ATP production and maximal mitochondrial respiratory capacity in WGP-trained BMDMs (Fig. 8e). These results suggest that the mitochondrial fission pathway is critical in WGP-induced central trained immunity.

Fig. 8 |. Mitochondrial fission is essential for bone marrow-derived macrophage-trained immunity.

a, Schema for in vivo training, Mdivi-1 or DMSO treatment, and BMDM differentiation. Six-week-old C57BL/6 mice were trained with or without WGP along with Mdivi-1 (50 mg per kg body weight, i.p.) or DMSO treatment. BM cells were collected on day 6. b, BMDMs from different groups were stimulated with LPS or LLC supernatant (n = 5). The culture supernatants were collected to measure TNF levels by ELISA. c, In vitro WGP-trained BMDMs (n = 5) and untrained BMDMs (n = 6) were subjected to Seahorse Mito Stress Test assay. Seahorse Mito Stress Test with sequential addition of oligomycin, FCCP and antimycin A (AA)/Rot. OCR bioenergenic profiling showing relative values of parameters for representative Seahorse assay (above) is shown. d, Seahorse Mito Stress Test in untrained BMDMs in the presence of Mdivi-1 (n = 8) or vehicle control (n = 6). OCR bioenergenic profiling showing relative values of parameters for representative Seahorse assay is also shown. e, Seahorse Mito Stress Test in WGP-trained BMDMs in the presence of Mdivi-1 (n = 8) or DMSO (n = 8). OCR bioenergenic profiling showing relative values of parameters for representative Seahorse assay is also shown. f, Schema for in vitro WGP training in BMDMs and adoptive transfer. g, Lungs were collected from mice that received BMDMs from different groups and tumor burden was assessed by flow cytometry (n = 9, 8, 5 and 7). Representative flow plots and summarized data are shown. Cells were gated on the CD45− population. h, Lung single-cell suspensions were stained with CD4 and FoxP3. Representative flow plots and summarized total CD4+ and CD4+FoxP3+ Treg cell percentages are shown (n = 9, 8, 5 and 6). i, Representative flow plots and summarized data for TNF expression in lung CD4+ T cells (left) (n = 9, 7, 5 and 6) and summarized ratios of effector CD4+ T cells (TNF+CD4+) to FoxP3+ Treg cells (n = 9, 7, 5 and 5) are shown. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments and are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. P values were derived from two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple-comparison test for b, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test for c–e and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test for g–i.

We next hypothesized that these BMDMs may be used in adoptive cell therapy to control metastasis. BMDMs were trained with WGP in vitro and naïve mice that received WGP-trained or untrained BMDMs were challenged with LLC-GFP (Fig. 8f). Mice that received WGP-trained BMDMs had significantly lower tumor burden in the lungs compared to mice that received untrained BMDMs (Fig. 8g). Increased CD4+ T cells and decreased Treg cells were also noted in mice that received WGP-trained BMDMs (Fig. 8h). In addition, TNF-producing effector T (Teff) cells were increased in these mice and consequently the ratio of Teff cells to Treg cells also increased (Fig. 8i). Mdivi-1 treatment in WGP-trained BMDMs abrogated these effects, further suggesting that the mitochondrial fission pathway is essential in WGP-mediated trained immunity and subsequent tumor metastasis control. To examine whether trained BMDMs can be used in the therapeutic setting, mice were inoculated with LLC-GFP followed by transfer of WGP-trained or untrained BMDMs (Extended Data Fig. 9g). Mice that received WGP-trained BMDMs had significantly reduced tumor burden in the lungs compared to mice that received untrained BMDMs (Extended Data Fig. 9h). These data imply that trained BMDMs could be used as an adoptive cell therapy in cancer.

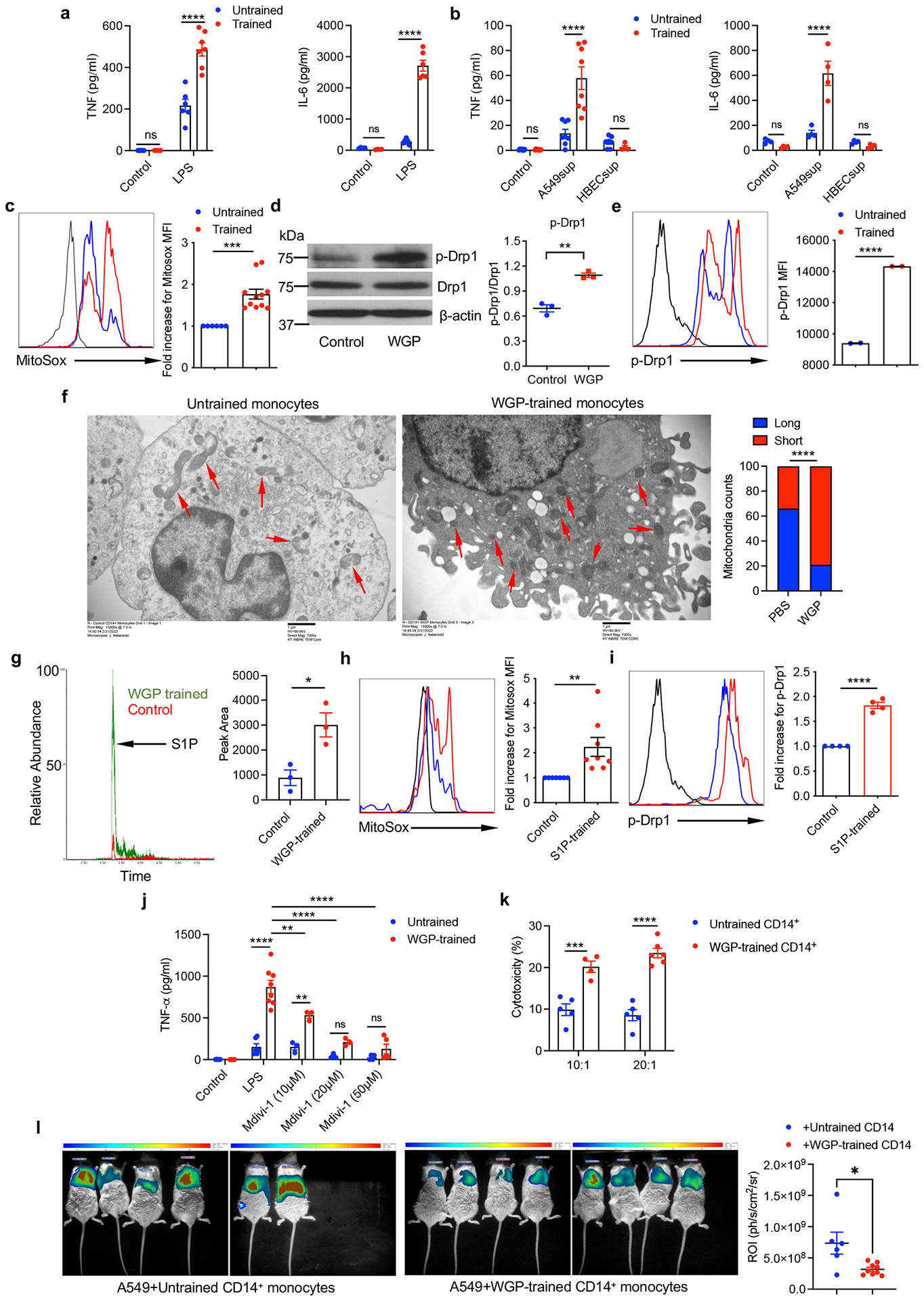

Whole beta-glucan particle induces trained immunity in human monocytes

To ascertain the human relevance of our findings, we aimed to recapitulate the phenotype using human monocytes. WGP-induced trained immunity in human CD14+ monocytes was revealed by enhanced TNF and IL-6 production upon restimulation with LPS (Extended Data Fig. 10a) or culture supernatants from human non-small-cell lung cancer cell line A549 but not from normal human bronchial epithelial cells (Extended Data Fig. 10b). WGP training in monocytes stimulated enhanced mtROS production (Extended Data Fig. 10c) and increased p-Drp-1 expression assessed by both western blot analysis and flow cytometry (Extended Data Fig. 10d,e). Mitochondrial fission in WGP-trained monocytes was also demonstrated by TEM (Extended Data Fig. 10f). We found that S1P accumulated in WGP-trained monocytes and that S1P induced enhanced mtROS production and p-Drp-1 expression in human monocytes (Extended Data Fig. 10g–i). Addition of Drp1 inhibitor Mdivi-1 abrogated WGP-mediated trained immunity (Extended Data Fig. 10j). Finally, we showed that WGP-trained monocytes exhibited significant cytotoxicity against A549 lung cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo (Extended Data Fig. 10k,l). NSG mice that received WGP-trained monocytes admixed with luciferase-tagged A549 cells had significantly lower lung tumor burden compared to mice that received untrained monocytes as assessed by in vivo bioluminescence imaging (Extended Data Fig. 10l). These results suggest that WGP induces trained immunity in human monocytes resulting in enhanced antitumor immunity.

Discussion

Trained immunity exerted by nanobiologics and beta-glucan has been reported to induce an antitumor effect in primary subcutaneous tumors15,25,39. However, the mechanisms by which innate immune cells induce a trained response upon tumor challenge and the etiology of secondary stimuli that elicit trained responses have not been well studied. In this study, we show that WGP-trained macrophages elicit a trained response upon stimulation with both tumor cells and tumor-derived factors, suggesting that the induction of trained response could be a part of the immunosurveillance mechanisms that inhibit tumor development and metastasis.

Induction of myelopoiesis by reprogramming HPSCs is a cardinal feature of beta-glucan-mediated trained immunity25,36. It is believed that cytokines GM-CSF and IL-1β and the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway are critical in beta-glucan-induced myelopoiesis25,36. We also observed myelopoiesis in the BM upon WGP treatment, leading to a systemic increase in myeloid cells. Despite inducing trained immunity systemically, no systemic inflammation was observed in these mice. We reason that this lack of systemic inflammation is because there are no secondary stimuli available to trigger a trained response. In the lung compartment, there are many myeloid cell subsets. We showed that lung IMs, but not AMs, are trained by WGP. Lung IMs are heterogeneous populations and some of these IMs are BM-derived cells and can be populated from circulating monocytes28. Because WGP training induces BM myelopoiesis, BM-derived monocytes that bear a trained immunity phenotype may traffic into the lung and differentiate into IMs. Indeed, we show that CCR2+ IMs displayed a trained immunity phenotype upon WGP treatment, which is abolished in CCR2 KO mice. This is consistent with previous reports using C. albicans infection models12. Importantly, we show that WGP-trained lung IMs elicit a vigorous trained response upon restimulation with tumor-derived factors. These data lead us to hypothesize that WGP-induced trained lung IMs may control tumor lung metastasis. We used multiple mouse metastasis models and demonstrated that WGP-induced trained immunity inhibits tumor metastasis and prolongs tumor-free survival. We also showed the benefit of the systemic effect of WGP training using a liver metastasis model. Mice reconstituted with BM cells from WGP-trained mice also showed reduced tumor burden. These data collectively support that BM-originated IMs are essential in controlling metastasis. We further used a clinically relevant lung metastasis model and a K-rasLA1 genetically engineered mouse model for spontaneous lung cancer development. Treatment with WGP resulted in prolonged survival in the 4T1 primary breast cancer resected Balb/c mice, reduced lung tumor nodules in K-rasLA1 mutated mice, and decreased lung metastasis in the primary 4T1 model. Surgical resection of primary tumors to minimize the risk of secondary organ metastases is a common practice for individuals with early-stage cancer. However, nearly 30% of women diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer will develop metastatic disease40,41. Therefore, individuals who have received surgical excision of primary tumors require adjuvant therapies to prevent occurrence of metastases42. Our data suggest that the induction of trained immunity through modalities such as WGP treatment may provide an option for these individuals.

A recent study reported that beta-glucan-induced granulopoiesis and neutrophil-mediated antitumor responses are critical in controlling primary subcutaneous tumors15. In our study, however, depletion of neutrophils during the WGP training phase or the whole-tumor protocol did not affect WGP-mediated training and metastasis control. The difference may be due to different tumor models and conformation and sources of beta-glucan. WGP is a particulate form of beta-glucan and can cluster receptors to form a ‘phagocytic synapse’, while soluble beta-glucan does not have such an effect43. In addition, depletion of T cells did not affect WGP-mediated training and metastasis control. This result is further validated in NSG mice. However, WGP training did enhance T cell responses in tumor-bearing mice. RNA-seq analysis also showed an enrichment of immune effector functions and antigen processing and presentation in WGP-trained IMs. Thus, enhanced T cell effector function could be a result of a WGP-mediated increase in macrophage antigen processing and presentation.

We demonstrate that BM-originated lung IMs are the primary effector cells that control tumor metastasis. There are several lines of evidence to support this notion. First, we used the conventional Clodrosome method to deplete macrophages, which abolished WGP-mediated lung metastasis control. Second, WGP-induced lung IM trained immunity and subsequent tumor metastasis inhibition were abrogated in CCR2 KO mice. CCR2 is predominately expressed on BM-derived macrophages. Third, WGP training in NSG mice resulted in lung IM trained immunity and lung metastasis control. Finally, we used in vitro WGP-trained BMDMs as an adoptive cell therapy and showed that mice that received WGP-trained BMDMs had significantly reduced lung tumors. Engineered cellular immunotherapies have been widely investigated in cancer44, particularly for chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells. Effective control of tumor metastasis by adoptively transferred WGP-trained BMDMs opens a new avenue of using trained immunity for cancer treatment and metastasis control. Using innate immune cells such as trained macrophages for adoptive cell therapy has an advantage over CAR T cells as they are not restricted to the major histocompatibility complex and can be manufactured off-the-shelf. However, more work is needed to develop this therapy in the future.

Induction of trained immunity has been attributed to the metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming through the HIF-1α–mTOR signaling pathway and the inflammasome-dependent IL-1β pathway10,45. Metabolites such as mevalonate and lipoproteins have been reported to induce trained immunity46,47. However, we showed that deficiency of HIF-1α, mTOR, Nlrp3 or IL-1R in myeloid cells did not affect WGP-mediated metastasis control. We established a new sphingolipid-mediated mitochondrial fission pathway that is responsible for WGP-induced trained immunity and subsequent metastasis control. We show that S1P induces trained immunity in macrophages. S1P also induces enhanced mtROS production in both mouse macrophages and human monocytes. S1P mediates macrophage differentiation, migration and survival and therefore is an important determinant of macrophage function48. Inhibition of S1P by Sphk2i treatment abolished WGP-induced trained immunity and subsequent tumor metastasis control. We also demonstrated that increased mitochondrial fission leads to an increased mtROS production, which leads to enhanced cytotoxicity. Inhibition of mitochondrial fission abolished trained immunity and metastasis control. These findings suggest that mitochondrial fission is essential in WGP-induced trained immunity and tumor metastasis control. A recent study also showed that oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced trained immunity in human monocytes depends on mitochondrial function49.

Based on these findings, we propose a new pathway for WGP-mediated trained immunity, where WGP treatment leads to an enhanced sphingolipid synthesis and subsequent accumulation of S1P in macrophages. An increase of S1P results in Drp-1 activation and mitochondrial fission, leading to an enhanced mtROS production and cytotoxicity against tumor cells. These trained macrophages elicit a trained response upon restimulation with tumor-derived factors resulting in a significant antitumor immunity that inhibits tumor progression and metastasis. Our findings highlight that the induction of trained immunity can be used as an effective approach to control cancer metastasis.

Methods

Mice

C57BL/6, Balb/c and IL-1R KO mice were from The Jackson Laboratory. HIF-1αfl/fl/LysM-cre, Raptorfl/fl/LysM-cre and Rictorfl/fl/LysM-cre mice on C57BL/6 background were generated as described previously4. MIF KO and CD74 KO mice were provided by R. Mitchell. K-rasLA1 and Nlrp3 KO mice were provided by H. Bodduluri. All these mice along with Dectin-1 KO, NSG and CCR2 KO mice were housed in a pathogen-free facility at University of Louisville at ~22 °C and 40–60% humidity with a 12-h dark/light cycle and fed with rodent diet 5010 (LabDiet). Mice were at least 6 weeks of age, and experiments were performed in accordance with relevant laws and guidelines approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Louisville (IACUC nos. 6574, 19536 and 22115).

Preparation of beta-glucan and DTAF-labeled whole beta-glucan particle

S. cerevisiae-derived particulate beta-glucan (WGP, Biothera) and 5-([4,6-dichlorotriazin-2-yl]amino) fluorescein hydrochloride (DTAF)-labeled WGP was prepared by incubating WGP (20 mg ml−1) with DTAF (2 mg ml−1; Sigma-Aldrich) in borate buffer (pH 10.8) at room temperature (RT) for 8 h with continuous shaking. The mixture was washed with cold sterile endotoxin-free DPBS (Sigma-Aldrich) for five times50. WGP contains 72% 1,3:1,6-beta-glucan as measured by beta-glucan assay kit (Megazyme, K-YBGL).

PFIR characterization of whole beta-glucan particle

A 20 μl WGP (20 μg ml−1) was dropped on a silicon wafer and dried in the air. The topography, IR absorption, stiffness and adhesion images of WGP particles were acquired using home-built PFIR microscopy. Briefly, PFIR spectral scans between 900 and 1,800 cm−1 were first performed at different locations on the WGP surface. Then PFIR signal at 1,040 cm−1, which is the characteristic signal of polysaccharides, was acquired over the entire WGP surface. During IR scanning, stiffness and adhesion properties of the WGP were simultaneously acquired.

Whole beta-glucan particle phagocytosis

GFP-dectin-1-expressing RAW 264.7 cells were plated on a 35-mm glass coverslip in complete DMEM overnight. WGP particles were added and fluorescence images were acquired using Re-scan confocal microscope equipped with a 1.64 NA ×100 TIRF objective and Hamamatsu CMOS camera. Three-dimensional fluorescence image stacks were projected to two-dimensional images based on maximum intensity using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health (NIH)).

In vitro whole beta-glucan particle training

Purified peritoneal macrophages and BMDMs were treated with WGP (25 μg ml−1) or polystyrene beads (3 μm; Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 h at 37 °C. Macrophages were washed with complete DMEM twice to remove excess WGP or polystyrene beads, complete DMEM was added and cells were incubated for 6 d. On day 7, macrophages were restimulated with different stimuli including LPS (10 or 100 ng ml−1; Sigma), tumor cells, tumor cell culture supernatants (40%) or rMIF (100 ng ml−1; provided by R. Mitchell) for 24 h. The culture supernatants were collected for TNF assay using ELISA (BioLegend, 430901). For cell culture supernatants, tumor cells including LLC, B16F10, EL4 and control cell line MLE-12 were cultured for 72 h (1 million per 4 ml of complete DMEM). The supernatants were stored at −80 °C in aliquots. MIF levels were measured by MIF ELISA kit (R&D Systems, DY1978). For anti-MIF neutralizing assay, WGP-trained and untrained peritoneal macrophages were restimulated with LLC supernatant (10%) in the presence or absence of anti-MIF neutralizing monoclonal antibody (50 and 75 μg ml−1) for 24 h. For in vitro training with S1P, peritoneal macrophages were stimulated with S1P (200 or 300 nM) for 24 h. The macrophages were washed and allowed to rest. On day 7, macrophages were restimulated with LPS or LLC culture supernatant for 24 h. For in vitro training with different inhibitors, macrophages were trained with WGP or S1P in the presence or absence of Mdivi-1 (10 μM; Sigma-Aldrich), sphingosine kinase-2 inhibitor (50 μM; Cayman Chemicals, ABC294640), Fumonisin-B1 (50 μM, Sigma-Aldrich), or the corresponding vehicle controls during training and resting periods.

In vivo whole beta-glucan particle training

Mice were i.p. injected with one dose of WGP (1 mg) on day 0 and euthanized on day 7 to assess lung, BM, spleen and lymph node phenotype. Mice treated with 1 mg polystyrene beads or PBS were used as controls. For ex vivo restimulation, cells were restimulated with LPS (10 ng ml−1), LLC culture supernatant (40%) or rMIF (100 ng ml−1) in the presence of brefeldin A (BioLegend). The cells were stained for surface markers and intracellular TNF.

Flow cytometry

Cells from lung, spleen and lymph nodes were incubated with Fc blocker for 10 min at 4 °C, and then stained with viability dye eFluor 780 (eBioscience), anti-CD45-PerCP-Cy5.5, anti-CD11b-APC, anti-F4/80-PE, anti-Ly6C-PerCP-Cy5.5, anti-Ly6G-PE, anti-CX3CR1-FITC, anti-CD4-APC, and anti-CD8-FITC (BioLegend; 1:300 vol/vol dilution) for 30 min at 4 °C. For BM phenotyping, cells were stained for anti-CD19-APC, anti-Ter119-APC, anti-CD11b-APC, anti-Ly6C/G-APC and anti-CD3-APC as lineage markers along with anti-Ly6A/E-APC-Cy7 (Sca-1), anti-CD117-PE-Cy7 (c-kit), anti-CD48-FITC and anti-CD150-PE-Cy5 (SLAM; BioLegend; 1:300 dilution) for Lin−Sca-1+c-kit+ LSK populations and Lin−Sca-1+c-kit+ CD48+CD150− MPPs. Data were collected using FACSCanto flow cytometer (BD Bioscience). The intracellular TNF (anti-TNF-PE; 1:600 dilution) and FoxP3 (anti-FoxP3-PE; 1:300 dilution) staining was performed using Fixation Buffer (BioLegend, 420801) and Foxp3 Staining Buffer Set (Thermo Fisher, 00-5523-00) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Information for all flow antibodies is provided in the Reporting Summary. Flow data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Tumor metastasis models

Mice were treated with an i.p. injection of WGP (1 mg in 200 μl PBS) or PBS on day 0, and on day 7 mice were inoculated i.v. with tumor cells (LLC-GFP, B16F10 or EL4) in 200 μl of PBS. After 14–16 d, mice were assessed for tumor development in the lungs or liver, or observed for long-term survival. For the short-term tumor protocols, mice were injected with 1 × 106 LLC-GFP cells on day 7 after WGP treatment and after 24–48 h, the frequency of LLC-GFP cells was determined by flow cytometry (gated on viable, CD45-negative population). For the 4T1 model, 6-week-old female Balb/c mice were subcutaneously implanted with 4T1 cells (0.1 × 106 cells per mouse) on the fourth mammary pad. When tumor size reached 2–3 mm in diameter, tumors were surgically resected. Five days after surgery, mice were injected with WGP (1 mg) or PBS and observed for long-term survival. In a separate set of experiments, female Balb/c mice were implanted with 4T1 tumors for primary tumor development. On day 5, mice were treated with WGP (1 mg) or PBS and euthanized 2 weeks later to analyze lung metastasis. For the spontaneous K-rasLA1 lung cancer model, 6-week-old K-rasLA1 mice were i.p. injected with WGP (1 mg) or PBS. Treatments were repeated at 9, 12 and 15 weeks of age. The mice were euthanized at 17 weeks, and tumor nodules in lungs were counted and assessed using H&E staining by 3DHISTECH’s CaseViewer. The humane endpoints of tumor-bearing mice included loss of 15% body weight or primary tumor size beyond 15 mm in diameter.

Bone marrow chimeric mice

BM cells were collected from trained (WGP 1 mg) or untrained CD45.2+ C57BL/6 mice 7 d after treatment and adoptively transferred into irradiated (950 rads) CD45.1+ B6 SJL mice (5 × 106 per mouse). BM reconstitution in recipient mice was examined by determining the ratio of CD45.2+ to CD45.1+ in lung IMs 4 weeks after adoptive transfer. Peripheral blood was used to confirm BM reconstitution by staining CD3+ T cells, CD19+ B cells, Gr-1+ neutrophils and NK1.1+ cells. Then, LLC-GFP cells (0.4 × 106) were injected i.v. into these mice and the lung metastasis burden was determined at day 14 after tumor cell injection. TNF expression by lung IMs after ex vivo LPS (1 ng ml−1) restimulation was also examined by flow cytometry.

Depletion of macrophages, T cells and neutrophils

Macrophage depletion was performed by i.v. injection of Clodrosome (Encapsula NanoSciences) at 200 μl per mouse on days −2, 2 and 5. To deplete CD4+ and/or CD8+ T cells, mice were i.p. injected with 200 μg of anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody or both on days −1 and 4 during the training period. Neutrophil depletion was performed by i.p. injection of anti-Ly6G monoclonal antibody (300 μg; Bio X cell) on days −1, 2 and 6 during the training period. Mice were trained with either PBS or WGP on day 0, and challenged with 0.4 × 106 LLC-GFP tumor cells i.v. on day 7. In a separate set of experiments, neutrophils were depleted throughout the training and tumor protocol with anti-Ly6G monoclonal antibody or isotype monoclonal antibody on days −1, 6 and 13. Mice were trained on day 0 and challenged with LLC-GFP on day 7.

RNA sequencing and RT–qPCR

RNA was extracted from purified lung IMs (viable, CD45+CD11b+F4/80+ population) of mice trained with PBS and WGP (day 7) using RNAeasy Kit (QIAGEN, 74004) and checked for integrity using Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies). Poly-A enriched mRNA-seq libraries were prepared following the Universal Plus mRNA-Seq kit standard protocol (Tecan Genomics, 0520–24) using 10 ng of total RNA. All samples were ligated with Illumina adaptors and individually barcoded. Absence of adaptor dimers and consistent library size of approximately 300 bp was confirmed using the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100. The library concentration and sequencing behavior was assessed in relation to a standardized spike-in of PhIX using a Nano MiSeq sequencing flow cell from Illumina. Around 1.8 pM of the pooled libraries with 1% PhiX spike-in was loaded on one NextSeq 500/550 75-cycle High Output Kit v2 sequencing flow cell and sequenced on the Illumina NextSeq 500 sequencer targeting 60 M 1 × 75-bp reads per sample50. Differential expression was performed using DESeq2 software51. Functional annotation analysis of the DEGs was performed using GSEA52. RNA-seq data were deposited with the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession code GSE195750. For qRT–PCR, RNA was extracted from lung IMs of PBS control mice versus WGP-trained mice using standard phenol-chloroform method.

Phagocytosis assay

Lung cells were resuspended in 100 μl antibiotic-free complete RPMI 1640 containing HEPES in non-adherent culture tubes. Particles were reconstituted as indicated in the pHrodo Green S. aureus Bioparticles Phagocytosis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, P35367), and were added to cells, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 1 h with gentle mixing every 15 min. Cells were stained with viability dye eFluor 780, anti-CD45-PerCP-Cy5.5, anti-CD11b-PE-Cy7 and anti-F4/80-APC. Phagocytosis by lung macrophages was determined by flow cytometer.

Cytotoxicity assay

Lung IMs from PBS control mice versus WGP-trained mice were co-cultured with LLC cells at different ratios in a 96-well plate. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. The supernatants were assayed for the release of LDH using the CyQUANT LDH Cytotoxicity Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher, C20300). For the cytotoxicity assay in the presence of Mdivi-1, peritoneal macrophages were in vitro trained with PBS or WGP in the presence of Mdivi-1 (10 μM) or DMSO for 6 d. The macrophages were co-cultured with LLC cells at a ratio of 10:1 followed by use of the LDH assay for cytotoxicity. In another set of experiments, IMs from the lungs of PBS versus WGP-trained mice were co-cultured with LLC cells (10:1 ratio) in the presence of Mito-TEMPO (Sigma-Aldrich) or DMSO in the cytotoxicity assay. For the human monocyte-mediated cytotoxicity assay, monocytes were trained with WGP for 24 h and then rested for 6 d. Control and WGP-trained monocytes were mixed with A549-luciferase-expressing cells at a ratio of 10:1 or 20:1 in round-bottomed 96-well plates and incubated for 16 h at 37 °C. Following incubation, the plates were centrifuged at 493g for 5 min at RT and supernatants were then harvested. The cells were then washed with PBS followed by lysis using 50 μl of 1× reporter lysis buffer (Promega) and incubation for 15–20 mins at −80 °C. The supernatants were harvested after centrifugation of the plates at 493g for 5 min at 4 °C. Around 20 μl of supernatants were mixed with 20 μl of Luciferase Assay Reagent (Promega) and Luciferase activity was measured using a luminometer (Femtomaster FB 12, Zylux). Luciferase values are measured as relative light units (RLUs). The cytotoxicity (%) was calculated using the equation: (experimental RLU − effector spontaneous RLU) / (maximum target RLU − spontaneous target death RLU) × 100.

Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species quantification

Peritoneal macrophages and human monocytes were treated with WGP or S1P with or without Mdivi-1 and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The cells were stained with MitoSOX Red dye (5 μM; Invitrogen) at 37 °C for 15 min, and washed with pre-warmed HBSS and PBS at RT. The cells were then stained with viability dye, anti-F4/80 and anti-CD14 for flow cytometry.

Confocal microscopy

Macrophages were cultured on the poly-l-lysine-treated glass coverslips and trained with WGP alone or with Mdivi-1 (10 μM). After 7 d culture, the cells were incubated with TMRM dye (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 20 min and then fixed with 4% formalin at RT for 20–30 min. After washing thrice with PBS, the glass coverslips were mounted on slides and left overnight to dry at RT or stored at 4 °C protecting from light. The slides were read using a Nikon Confocal microscope. Mitochondrial fragment lengths were measured by counting at least 100 mitochondria per sample using ImageJ.

Transmission electron microscopy

WGP-trained and untrained peritoneal macrophages and human monocytes were washed with PBS, centrifuged at 94g for 10 min, and suspended in 0.1 M phosphate buffer containing 4% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde TEM fixative followed by centrifugation and storage at 4 °C for 48 h. The pellets were then stained with osmium tetroxide, washed, dehydrated in increasing ethanol percentages, and embedded with Durcupan resin. The embedded pellets were cut using an ultramicrotome into 80-nm sections and placed on grids. The grids were further stained with uranyl acetate followed by lead citrate and finally imaged using TEM (Hitachi, HT7700).

Detection of p-Drp-1

Peritoneal macrophages and human monocytes were treated with WGP (25 μg ml−1) or S1P (1 μM) for 3–4 h. After incubation, the cells were quickly washed with cold PBS and then fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 15 min at RT and permeabilized using ice-cold 100% methanol on ice for 10 min. The cells were then stained with primary antibody (p-Drp-1; Cell Signaling, 1:50 dilution) for 1 h at RT followed by incubation with anti-rabbit IgG-FITC (BioLegend; 1:300 dilution) for 30 min at RT as instructed in the Cell Signaling phospho-stain protocol. The p-Drp-1 was analyzed using flow cytometry. For western blot, cell lysates were further denatured and ran for SDS–PAGE followed by transfer to PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% BSA in Tris buffered saline-Tween for 1 h at RT and incubated with primary anti-Drp-1, p-Drp-1 (Cell Signaling Technology; 1:1,000 dilution) and β-actin (Sigma; 1:5,000 dilution) overnight at 4 °C. The membrane was then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at RT. The blots were detected using ECL plus Western Blotting Detection System (Amersham Biosciences, RPN2232).

Sphingosine-1-phosphate quantification

S1P was extracted using a well-established method with minor modifications as described previously53. WGP-trained and untrained peritoneal macrophages or human monocytes (1 × 106) suspended in 400 μl PBS were treated with 1.5 ml of methanol/chloroform at a concentration of 2:1 vol/vol ratio and vortexed for 1 min. Induction of phase separation was then allowed by addition of 500 μl of chloroform to the mixture followed by addition of 500 μl of H2O. The bottom layer was collected and allowed for drying under gentle nitrogen flow. Around 50 μl of methanol/chloroform (1:2 concentration, vol/vol) was added to tubes for final analysis by LC–MS/MS (Waters ACQUITY UPLC Systems with 2D Technology coupled with Waters Xevo TQ-S micro triple quadrupole Mass Spectrometer). Further S1P analysis was performed using multiple reaction monitoring in positive ionization mode.

In vivo treatment with inhibitors

C57BL/6 female mice were i.p. injected with Mdivi-1 (50 mg per kg body weight), or DMSO along with suitable carriers (5% Tween-80 and 40% PEG300) starting at day 0 for 6 d. These mice were also treated with PBS or WGP at day 0. BM and lungs were collected at day 7 for phenotyping using flow cytometry. In the tumor challenge experiment, Mdivi-1/DMSO-treated PBS mice versus WGP-trained mice were i.v. injected with 0.4 × 106 LLC-GFP cells on day 9. Lungs were collected at day 27 for tumor burden analysis. For Sphk2i treatment, C57BL/6 mice were treated with i.p. injection of Sphk2i (50 mg per kg body weight) or DMSO control followed by i.p. injections of PBS or WGP (1 mg) 2–3 h later. The treatments with Sphk2i/DMSO were repeated daily for 4 additional days. Mice were then challenged with LLC-GFP tumor cells 2 d later for tumor burden analysis at day 16.

CyTOF mass cytometry

Lung single-cell suspensions were prepared as described earlier4 and ex vivo stimulated with PMA–ionomycin for 4 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. The cells were then collected, washed with PBS and transferred to sterile-capped culture tubes. Cells were then stained for viability using 5 μM cisplatin (Fluidigm) in serum-free RPMI 1640 for 5 min at RT and washed with complete RPMI 1640. Cells were stained with the surface marker antibodies for 30 min at RT and washed twice with Maxpar cell staining buffer (Fluidigm) followed by fixation with 1 ml of 1× Maxpar Fix I buffer for 30 min at RT. Upon fixation, cells were washed twice with 2 ml of 1× Maxpar Perm-S buffer for 5 min at 800g, stained for the cytoplasmic/secreted antibodies and incubated for 30 min at RT. Following incubation, cells were washed twice with 1 ml of 1×Maxpar Perm-S buffer for 5 min at 800g. The cells were then suspended in 1 ml of 1× Maxpar nuclear antigen staining buffer (Fluidigm) and incubated for 30 min at RT, washed twice with Maxpar nuclear antigen staining permeability buffer (Fluidigm) at 800g for 5 min each. Cells were stained for nuclear antigens and incubated at RT for 30 min, washed twice with Maxpar nuclear antigen staining permeability buffer and fixed with 1.6% formaldehyde for 10 min at RT. The fixed cells were then centrifuged to remove the formaldehyde at 800g for 5 min and incubated with 125 nM of intercalator iridium (Fluidigm) overnight at 4 °C. After overnight incubation, the cells were washed twice with cell staining buffer, pelleted and kept on ice until acquisition using CyTOF. Before acquisition, cells were suspended in a 1:9 solution of cell acquisition solution: EQ 4 element calibration beads (Fluidigm) and acquired using a Helios CyTOF system. Upon acquisition of the samples, the .FCS files were normalized to .fcs files and the data were then analyzed using FlowJo 10 and the FlowSOM software.

Training CD14+ monocytes in vitro

Monocytes were isolated from peripheral blood using an anti-human CD14-PE antibody (BioLegend, 325606). The monocytes were plated for 4–6 h and then treated with 25 μg ml−1 WGP for 24 h followed by a gentle wash and culture for 6 d. Cells were restimulated with LPS (100 ng ml−1), 40% A549 supernatant or human bronchial epithelial cell supernatant for 24 h. The supernatants were collected for TNF and IL-6 measurement by ELISA (BioLegend, 430201 and 430501). For another set of experiments, the monocytes were treated with Mdivi-1 (10, 20 or 50 μM) during WGP treatment and training period followed by restimulation with LPS. Supernatants were collected for TNF and IL-6 measurement.