Abstract

The US Black population has higher colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence rates and worse CRC survival than the US White population, as well as historically lower rates of CRC screening. The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results incidence rate data in people diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 45 years, before routine CRC screening is recommended, were analyzed to estimate temporal changes in CRC risk in Black and White populations. There was a rapid rise in rectal and distal colon cancer incidence in the White population but not the Black population, and little change in proximal colon cancer incidence for both groups. In 2014-2018, CRC incidence per 100 000 was 17.5 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 15.3 to 19.9) among Black individuals aged 40-44 years and 16.6 (95% CI = 15.6 to 17.6) among White individuals aged 40-44 years; 42.3% of CRCs diagnosed in Black patients were proximal colon cancer, and 41.1% of CRCs diagnosed in White patients were rectal cancer. Analyses used a race-specific microsimulation model to project screening benefits, based on life-years gained and lifetime reduction in CRC incidence, assuming these Black–White differences in CRC risk and location. The projected benefits of screening (via either colonoscopy or fecal immunochemical testing) were greater in the Black population, suggesting that observed Black–White differences in CRC incidence are not driven by differences in risk. Projected screening benefits were sensitive to survival assumptions made for Black populations. Building racial disparities in survival into the model reduced projected screening benefits, which can bias policy decisions.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer and second leading cause of cancer mortality in the United States (1,2). Over the past 30 years, CRC incidence and mortality rates have declined as a result of screening, which 1) prevents CRC by detecting and removing precursor lesions before they transition to cancer and 2) reduces CRC mortality by identifying asymptomatic CRC at an earlier and more treatable stage. New treatments have also improved CRC survival (3), however, the benefits of these improvements in screening and treatment have not been equally distributed. In the United States, there are clear racial and ethnic differences in the burden of CRC, which are especially well-documented for the Black population (4). Here and throughout, reference to Black and White populations is a shorthand for populations that are segmented based on a race-attribute, a social rather than biological construct that reflects exposure to racism (5). CRC incidence rates are higher in the Black population than in the White population (6), and compared with White CRC patients, Black patients tend to be diagnosed at a younger age (6,7) and have poorer stage-specific survival, with 40% higher CRC-specific mortality rates (8-11).

Differences in CRC burden can arise through at least 2 pathways: differences in risk and differences in care (including both screening and treatment), with social determinants of health and structural racism underlying both pathways (12-16). In terms of differences in care, screening initiation has historically been lower in Black populations than in White populations, but these differences have narrowed over time (17-19) and appear to have finally been eliminated (2). Black patients and White patients in the same health system also have similar rates of timely follow-up after an abnormal stool-based test (20). At the same time, there is evidence of Black–White disparities in CRC treatment, consistent with CRC mortality differences. Compared with White patients, Black patients are less likely to be treated for CRC than White patients (3), with lower rates of surgical resection (21-23) and adjuvant chemotherapy (22), and are more likely to experience treatment delays (21,24-26).

Historical differences in screening make it difficult to estimate Black–White differences in CRC risk, because screening affects observed incidence rates. CRC arises from a generally slow-growing precursor lesion, either through the adenoma pathway (21,24,25-27) or the serrated pathway (primarily through sessile serrated lesions) (28). There is evidence that overall adenoma prevalence is similar in Black and White populations that have similar access to screening, though proximal adenomas may be more likely in the Black population (29,30). Although sessile serrated lesions are more likely in the proximal colon, current evidence indicates that sessile serrated lesions are less likely in Black populations than White populations (28).

Incidence of early onset CRC, defined as CRC diagnosed before age 50 years, provides a natural experiment for understanding Black–White differences in risk because routine screening was not recommended before age 50 years until recently. In 2009, the American College of Gastroenterology first recommended that Black people begin screening at age 45 years (31). In 2018, the American Cancer Society lowered the age for all people to begin screening to age 45 years (32), and in 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) also recommended that CRC screening begin at age 45 years (33). From 1992 to 2005, early onset CRC incidence rates were higher in US Black populations than White populations (34). During this time period, early onset CRC incidence rose rapidly in the US White population, with relatively small increases in the Black population (34). In 2010-2014, early onset CRC incidence rates were similar in Black and White populations (12.7 and 11.0 per 100 000, respectively), though the incidence rate of early onset rectal cancer was higher in the White population than the Black population (4.5 vs 4.0 per 100 000), and the incidence rate of proximal colon cancer was higher in the Black population than the White population (3.9 vs 2.4 per 100 000) (35).

Analyses compare projected screening benefits for Black and White populations in the context of secular changes CRC risk, shifts in CRC location, and Black–White disparities in CRC-specific and overall survival. First, we estimated Black–White differences in risk and cancer location using early onset CRC incidence rate data. These estimates were then used in combination with CRC-SPIN, a well-validated and calibrated CRC microsimulation model (36-38), with the goal of understanding how assumptions about test sensitivity and survival may affect projected, long-term effectiveness of CRC screening used to inform screening policy (32,33).

Methods

We estimated Black–White differences in CRC incidence rates using population-based rates from 1979 to 2018, as reported by the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program of cancer registries (39), restricted to individuals aged 20-44 years, before average-risk people become screening eligible. We analyzed SEER delay-adjusted incidence rates to account for reporting delays in recent years and excluded carcinoid tumors (included histology codes: 8000, 8001, 8010, 8020-8022, 8140, 8141, 8144, 8145, 8210, 8211, 8213, 8220, 8221, 8230, 8255, 8260-8263, 8480, 8481, 8490, 8560, 8570, 8574; additional description provided in Supplementary Materials, available online). Comparisons focused on non-Hispanic Black (hereafter, Black) and non-Hispanic White (hereafter, White) populations. Poisson regression models were used to describe incidence rates as a function of sex (female, male), race (Black, White), age (5 groups: 20-24, 25-29, 30-34, 35-39, and 40-44 years), and birth cohort (12 groups: 1937-1941, 1942-1946, 1947-1951, 1952-1956, 1957-1961, 1962-1966, 1967-1971, 1972-1976, 1977-1981, 1982-1986, 1987-1991, and 1992-1997). Regression models were stratified by tumor location (rectal, distal colon, and proximal colon) and included interactions between race and sex, and race and birth cohort. Colon cancers not assigned a proximal or distal location (C18.9) were proportionally distributed across distal and proximal locations based on the proportion of proximal colon cancers observed within each race group, age group, and year (40). Additional description of SEER data is provided in Supplementary Materials (available online).

CRC-SPIN, a microsimulation model for CRC, was used to project screening benefits after recalibrating the model to accurately project CRC incidence rates for Black and White populations aged 40-44 years in 2014-2018 (Supplementary Table S2, available online). CRC-SPIN is an all-race CRC model that simulates time to transitions through disease states (36-38). For each simulated individual, the model first generates a day of birth and a day of death. Because CRC deaths account for a small fraction of all deaths, non-CRC survival was based on overall mortality from 2017 US life tables from the National Center for Health Statistics (41). Next, the model simulates initiation of multiple adenomas using a Poisson process with risk that varies with age, sex, and birth cohort. Each adenoma is assigned a location in the large intestine, a growth rate, and a size at transition to preclinical CRC, which is used to determine the time at transition to CRC. Most adenomas do not transition within an individual’s simulated lifetime. The duration in the preclinical cancer state (sojourn time) is simulated using a Weibull distribution, with systematic differences in sojourn time for preclinical cancers in the colon and rectum based on proportional hazards assumption. Individuals can have multiple preclinical cancers, and given their location in the large intestine, the sojourn time of each is independent. CRC-specific survival assumptions incorporated in the model depend on stage and age at detection to indirectly model treatment effects (10). Differences in survival for patients with proximal colon cancer compared with distal colon cancer (42-44) were modeled by specifying a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.82 for distal vs proximal colon cancer (45).

Race-specific CRC-SPIN models were developed by starting with the calibrated all-race CRC-SPIN model (37), with model parameters set to their estimated posterior means. Next, 3 additional parameters that capture Black–White differences in adenoma risk and location were calibrated for each of the 2 race-specific models: 1) the difference in adenoma risk relative to the all-race model, 2) the percentage of adenomas located in the rectum, and 3) the percentage of adenomas located in the proximal colon. (The percentage of adenomas in the distal colon was obtained by subtraction.) Thus, differences in adenoma risk were assumed to drive Black–White differences in CRC risk. The simulated distribution of adenomas in the large intestine for each population is provided in Supplementary Table S3 (available online). The model was recalibrated using the R package imabc (46).

Simulated populations

The recalibrated race-specific CRC-SPIN models were used to project the long-term benefits of screening based on simulated lifetime outcomes for a single-age birth cohort of 10 million individuals born in 1975 that are CRC free and aged 45 years in 2020. We simulated 5 populations of 10 million each: 1 White population and 4 Black populations. The White population was simulated using estimates of CRC-specific and overall survival for a White population. The 4 Black populations were simulated under different assumptions about CRC-specific and overall survival: 1) with existing CRC-specific and overall survival disparities; 2) without CRC-specific survival disparities; 3) without overall survival disparities; and 4) with neither CRC-specific nor overall survival disparities.

Simulated screening scenarios

Two screening modalities were simulated, with screening from the ages of 45 to 75 years: 1) screening colonoscopy every 10 years and 2) annual fecal immunochemical test (FIT).

Colonoscopy is the most commonly used CRC screening test in the United States (47,48). To address variation in adenoma detection rates (49), 2 colonoscopy scenarios were simulated: a high-quality and a lower-quality scenario. The high-quality colonoscopy scenario matched assumptions made for modeling analyses used to inform USPSTF CRC screening guidelines, with lesion-specific sensitivity that was 0.75 for diminutive adenomas (between 1 and 5 mm), 0.85 for small adenomas (6-9 mm), and 0.95 for large adenomas (10 mm) and asymptomatic CRC, with 95% of exams were complete to the cecum. The lower-quality colonoscopy scenario is consistent with studies demonstrating somewhat lower adenoma detection rates (49,50), especially for diminutive adenomas, and assumed lesion-specific sensitivity that was 0.55 for diminutive adenomas, 0.70 for small adenomas, 0.90 for large adenomas, and 0.95 for asymptomatic CRC, with only 85% of exams complete to the cecum. Simulated sensitivities were estimated in 1 mm increments using Stineman interpolation (51).

Fecal immunochemical tests are a less invasive CRC screening strategy. There are many different fecal immunochemical tests in use, with different operating characteristics (ie, sensitivity to detect CRC and adenomas, and false-positive rates for people with neither adenomas nor CRC) (52). USPSTF guidelines for CRC screening were informed by modeling analyses that assumed use of the Polymedco OC FIT-CHEK with a 10 g/g positivity cutoff. The operating characteristics of this fecal immunochemical test were estimated in a sample of nearly 10 000 patients, and the test was found to have 96.4% specificity and 73.8% sensitivity for CRC (53). However, there is evidence that fecal immunochemical tests are less sensitive for stage I CRC than stage II-IV CRC (52,54,55). In addition, a recent study comparing 9 fecal immunochemical tests in 515 patients undergoing screening colonoscopy and 79 patients undergoing diagnostic colonoscopy found that, across fecal immunochemical tests, the sensitivity to detect CRC was lower for colon cancer than for rectal cancer and was lower for stage I CRC than stage II-IV CRC; sensitivity was also lower when a single vs multiple adenomas were present (52).

Two fecal immunochemical test scenarios were simulated. One fecal immunochemical test scenario assumed sensitivities that matched assumptions made for modeling analyses to inform USPSTF CRC screening guidelines (fecal immunochemical test–USPSTF ) (33). Fecal immunochemical test–USPSTF sensitivity was based on the most advanced lesion present at screening: 0.05 for diminutive adenomas, 0.15 for small adenomas, 0.22 for large adenomas, and 0.74 for asymptomatic CRC. The second fecal immunochemical test scenario assumed that sensitivity depended on cancer stage and location and on number of large adenomas, based on results reported for the OC-Sensor–fecal immunochemical test (52). The fecal immunochemical test stage and location-specific scenario assumed sensitivity for individuals with a single adenoma present at the time of screening was the same as fecal immunochemical test– USPSTF sensitivity with higher sensitivity (0.45) when 2 or more large adenomas were present. Fecal immunochemical test–stage and location-specific sensitivity for CRC was higher for rectal cancers (0.85 for stage I cancer and 0.95 for stage II-IV cancer) and lower for colon cancers (0.65 for stage I cancer and 0.70 for stage II-IV cancer) and was lower for stage I than stage II-IV CRC (52).

For the fecal immunochemical test screening scenarios, annual screening occurred until the first abnormal fecal immunochemical test. After an abnormal fecal immunochemical test, follow-up colonoscopy was simulated at 1 month. Individuals with no findings at follow-up colonoscopy (ie, the abnormal fecal immunochemical test was a false-positive result) were returned to fecal immunochemical test screening, with the next test in 10 years; otherwise, they were moved into adenoma surveillance.

Overall, 6 screening scenarios were simulated: 2 screening colonoscopy scenarios (high or lower quality) and 4 fecal immunochemical test screening scenarios (fecal immunochemical test–USPSTF and fecal immunochemical test–stage and location-specific, each with high- and lower-quality colonoscopy). For all screening scenarios, individuals were shifted into more intensive screening (ie, adenoma surveillance, based on adenomas detected at colonoscopy, as shown in Supplementary Table S6, available online) (56). Additional details about test sensitivity assumptions are provided in supplementary materials.

Projected outcomes

For each of the 5 populations, outcomes were simulated in the absence of screening and under the 6 screening scenarios. Projected screening benefit was based on life-years gained and percent reductions in lifetime overall and late stage (stage III and IV) CRC incidence.

Results

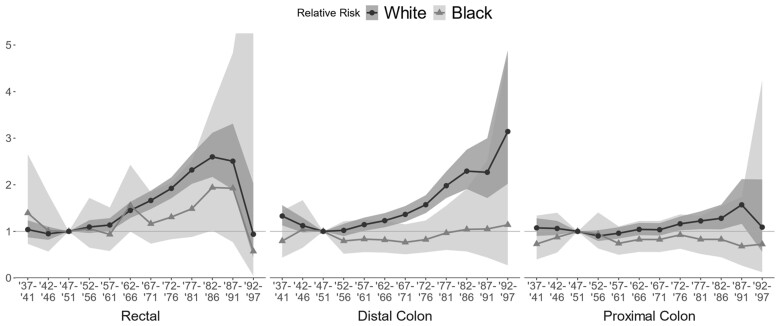

Analysis of SEER data confirmed previous findings (35). From 1979 to 2018, overall CRC incidence in people aged 20-44 years was higher in the Black population than the White population. The estimated relative risks of cancer diagnosis in the Black vs the White population were 1.19 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.88 to 1.57) for rectal cancer, 1.89 (95% CI = 1.49 to 2.37) for distal colon cancer, and 1.80 (95% CI = 1.45 to 2.23) for proximal colon cancer. Compared with the 1947-1951 birth cohort, there was evidence of strong birth cohort effects in the White population for rectal, distal colon, and proximal colon cancer, with a statistically significant increased risk of rectal and distal colon cancer for people born in 1957 and later and statistically significant increased risk of proximal colon cancer for people born in 1972 and later (Figure 1). Birth cohort effects were smaller in the Black population, and in general, relative risk increases were not statistically significant, though there was some indication of rising rectal cancer risk.

Figure 1.

Estimated birth cohort effects by race (Black–White) and CRC location, based on analysis of SEER-8 data. CRC = colorectal cancer; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

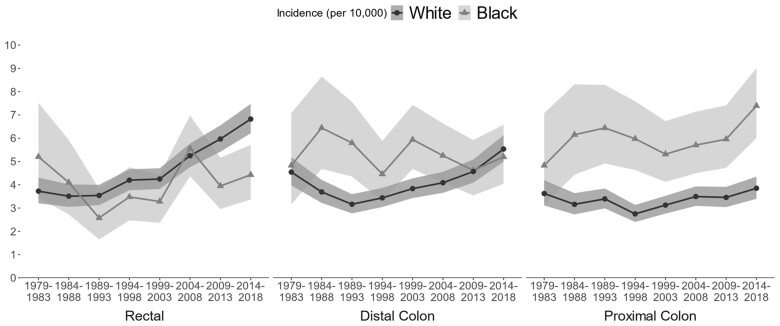

In both Black and White populations, CRC incidence rates among people aged 40-44 years rose from 1979 to 2018, and Black–White differences narrowed as CRC incidence rates rose more rapidly and consistently in the White population (Figure 2). In 2014-2018, CRC incidence per 100 000 was 17.5 (95% CI = 15.3 to 19.9) among Black individuals aged 40-44 years and 16.6 (95% CI = 15.6 to 17.6) in White individuals aged 40-44 years. At the same time, Black–White differences in the location of CRC widened (Table 1). In 1979-1983, CRC was relatively evenly distributed across the rectum, distal colon, and proximal colon, but by 2014-2018, Black CRC patients were most likely to be diagnosed with proximal colon cancer (42.3%) and least likely to be diagnosed with rectal cancer (25.3%), whereas White CRC patients were most likely to be diagnosed with rectal cancer (41.1%) and least likely to be diagnosed with proximal colon cancer (23.2%).

Figure 2.

CRC incidence per 10 000 individuals aged 40-44 years by race (Black–White) and year of diagnosis, based on analysis of SEER-8 data. CRC = colorectal cancer; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Table 1.

Distribution of CRC in Black and White populations aged 20-44 years, in earliest and most recent time periodsa

| Time period | Population | Estimated number of CRC cases | Rectal cancer | Distal colon cancer | Proximal colon cancer | Colon cancer NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979-1983 | Black population | 84 | 33.3% | 31.0% | 31.0% | 4.8% |

| White population | 589 | 30.9% | 37.7% | 30.0% | 1.3% | |

| 2014-2018 | Black population | 231 | 25.3% | 29.7% | 42.3% | 2.6% |

| White population | 1118 | 41.1% | 33.4% | 23.2% | 2.6% |

CRC = colorectal cancer; NOS = not otherwise specified.

Simulation results

Table 2 shows projected total life-years per 1000 people (after age 45 years) and life-years gained per 100 people screened for each simulated population and screening scenario. The ordering of the screening benefit across the 5 simulated populations was the same for all 6 screening scenarios. The greatest screening benefit was projected for the Black population with no overall survival disparity (Black+OS), consistent with higher CRC risk. The second greatest benefit was projected for the Black population with no survival disparity (Black+T+OS); improving CRC-specific survival (through better treatment) left fewer life-years to be gained by screening. The third greatest benefit was projected for the White population, followed by the Black population with existing overall and CRC-specific survival disparities. The least survival benefit was projected for the Black population with existing overall survival disparities but no CRC-specific survival disparity (Black+T).

Table 2.

Expected life-years per 10 000 people, beyond age 45 years, in the absence of CRC screening, and the projected life-years gained from screening per 100a

| Population |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black+OSb No overall survival disparity |

Black+T+OSc no survival disparity |

White | Black | Black+Td No CRC survival (treatment) disparity |

||

| Expected life-years after age 45 y, no screening | 356 582 | 357 038 | 356 998 | 332 181 | 332 628 | |

|

| ||||||

| Screening modality | Colonoscopy sensitivity | Life-years gained | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Colonoscopy | High | 40.9 | 36.4 | 35.8 | 35.3 | 31.8 |

| Fecal immunochemical test, stage and location-specific | High | 38.2 | 34.3 | 33.8 | 33.0 | 29.9 |

| Fecal immunochemical test, USPSTF | High | 37.8 | 34.0 | 33.4 | 32.6 | 29.6 |

| Colonoscopy | Lower | 37.5 | 33.4 | 33.0 | 32.3 | 29.1 |

| Fecal immunochemical test, stage and location-specific | Lower | 34.9 | 31.4 | 31.1 | 30.2 | 27.4 |

| Fecal immunochemical test, USPSTF | Lower | 34.5 | 31.0 | 30.6 | 29.7 | 27.0 |

Both rows and columns are ordered from most to least screening benefit. Black+OS = Black population with no overall survival disparity; Black+T+OS = Black population with no survival disparity; Black+T = Black population with no CRC survival (treatment) disparity; CRC = colorectal cancer; OS = overall survival; USPSTF = US Preventive Services Task Force.

The Black+OS population was simulated using the Black population’s estimated CRC risk, in combination with the White population’s overall mortality estimate.

The Black+T+OS population was simulated using the Black population’s estimated CRC risk, in combination with the White population’s survival CRC diagnosis, with captures treatment disparity, and the White population’s overall mortality estimate.

The Black+T population was simulated using the Black population’s estimated CRC risk, in combination with the White population’s survival CRC diagnosis, with captures treatment disparity.

The ordering of projected benefit across the 6 screening scenarios was the same for the 5 populations, with greatest benefit from high-quality colonoscopy and greater benefit from modalities that prevent CRC via screening colonoscopy and detection of precursor lesions. Screening colonoscopy was projected to have the most benefit, and fecal immunochemical test–USPSTF was projected to have the least benefit. Across simulated screening scenarios, lower-quality colonoscopy reduced screening benefit, with an average reduction of 2.9 life-years gained per 100 screened. The size of the reductions due to lower-quality colonoscopy tracked with the size of the projected screening benefit in each population, with the largest reduction (3.4 years per 100 screened) in the Black population without overall survival disparities (Black+OS) and the smallest reduction in the Black population without CRC-specific survival disparities (Black+T, 2.5 years per 100 screened).

Table 3 shows the projected lifetime CRC incidence rate after age 45 years per 10 000 and the percentage reduction in incidence rates for each simulated screening scenario and population. CRC-survival disparities do not affect projected overall incidence reductions. There was relatively little difference in the projected benefit across populations within screening scenarios. The widest range in incidence reduction across simulated populations, 1 percentage point, was projected for fecal immunochemical test–USPSTF with high-quality colonoscopy. There was an 18.9 percentage point range in the projected incidence rate reduction across screening scenarios, ranging from approximately 71% for fecal immunochemical test–USPSTF with lower-quality colonoscopy to approximately 89% for high-quality screening colonoscopy. The patterns of most to least reduction in overall CRC incidence was the same as observed for life-years gained, with the most benefit from strategies with high-quality colonoscopy.

Table 3.

Projected lifetime CRC incidence rate per 10 000 in the absence of screening, and the projected percent CRC incidence reduction because of screeninga

| Population |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black+OSb No overall survival disparity |

Black+T+OSc No survival disparity |

Black | Black+Td No CRC survival (treatment) disparity |

White | ||

| Lifetime CRC incidence after age 45 y, no screening | 788 | 787 | 701 | 699 | 774 | |

|

| ||||||

| Screening modality | Colonoscopy sensitivity | Incidence reduction | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Colonoscopy | High | 89.6% | 89.5% | 89.3% | 89.3% | 88.9% |

| Fecal immunochemical test stage and location-specific | High | 82.0% | 81.9% | 81.5% | 81.5% | 81.1% |

| Fecal immunochemical test USPSTF | High | 80.9% | 80.8% | 80.3% | 80.3% | 79.9% |

| Colonoscopy | Lower | 79.6% | 79.5% | 79.4% | 79.3% | 79.0% |

| Fecal immunochemical test stage and location-specific | Lower | 72.4% | 72.4% | 72.0% | 72.0% | 71.7% |

| Fecal immunochemical test USPSTF | Lower | 71.5% | 71.3% | 70.7% | 70.8% | 70.7% |

Both rows and columns are ordered from most to least screening benefit. Black+OS = Black population with no overall survival disparity; Black+T+OS = Black population with no survival disparity; Black+T = Black population with no CRC survival (treatment) disparity; CRC = colorectal cancer; OS = overall survival; USPSTF = US Preventive Services Task Force.

The Black+OS population was simulated using the Black population’s estimated CRC risk, in combination with the White population’s overall mortality estimate.

The Black+T+OS population was simulated using the Black population’s estimated CRC risk, in combination with the White population’s survival CRC diagnosis, with captures treatment disparity, and the White population’s overall mortality estimate.

The Black+T population was simulated using the Black population’s estimated CRC risk, in combination with the White population’s survival CRC diagnosis, with captures treatment disparity.

Projected reductions in late-stage CRC across populations were somewhat larger, with less variation across populations and screening scenarios, ranging from 90.3% to 96.3% reductions in late-stage CRC (results shown in Supplementary Table S9, available online).

Projected reductions in CRC mortality showed a somewhat different pattern, with the largest reductions in the Black populations without treatment disparities. There was greater variation in the projected CRC mortality reduction across populations and screening modalities than projected incidence reductions (results shown in Supplementary Table S10, available online).

Projected benefits of screening were similar (no different than 1.1 life-days per person) under the assumption of no survival difference for proximal and distal colon (results not shown).

Discussion

We examined whether the proximal shift in CRC observed in the Black population would impact the benefit of CRC screening, given that proximal colon cancer may be more difficult to detect using a fecal immunochemical test (52,57,58). Projected screening effectiveness was robust to differences in CRC location observed in Black and White populations. What mattered most, in terms of screening effectiveness, were assumptions about overall and CRC-specific survival. Assumptions about overall and CRC-specific survival build health-care disparities into microsimulation models, which project effects decades into the future. The impact of building existing disparities into models is especially important when projections are used to inform policy. We found that assuming ongoing disparities in overall survival could lead to underestimation of screening benefit in the Black population.

Projected screening benefit also depended on test sensitivity assumptions. Screening benefit was closely related to the ability of a test to detect precursor lesions to enable CRC prevention through their removal. Receipt of low-quality colonoscopy resulted in less benefit, consistent with findings that people who receive colonoscopy at facilities with lower adenoma detection rates are at greater risk for subsequent CRC (59).

There are several limitations to this study. The screening scenarios examined were limited to guideline-concordant receipt of care and assumed prompt evaluation of abnormal fecal immunochemical test results. Outcomes are expected to be worse when there are systematic delays in screening uptake, repeat screening, or colonoscopy to follow-up an abnormal fecal immunochemical test (60,61). Although the Black–White screening gap in staying up to date with screening has narrowed (2), information about race-specific screening behaviors needed to simulate screening as practiced is limited. Outcomes did not include quality-adjusted life-years gained or economic effects of screening. Fecal immunochemical tests require fewer colonoscopies per life-years gained, but a CRC diagnosis is more likely, reducing quality-adjusted life-years and increasing treatment costs. The model simulated minimal Black–White differences in CRC risk, reflecting the high degree of overlap in 95% confidence intervals of estimated CRC incidence. Simulating higher CRC incidence in the Black population would have resulted in somewhat greater screening benefit. Other limitations are related to the extent to which analyses incorporated the effect of lesion location. Although fecal immunochemical test sensitivity for CRC was allowed to depend on location in the large intestine and state at screening, fecal immunochemical test sensitivity for adenomas detection varied by size and number of adenomas but not by their location. The CRC-SPIN model did not include the serrated pathway. Because sessile serrated lesions are harder to detect than adenomas and may be more prevalent in White patients (62), projections may overestimate screening benefit in the White population. Finally, small differences in CRC risk were assumed to be driven by differences in adenoma prevalence but not differences in disease aggressiveness (63). Future work will examine the potential for differences in CRC incidence that arise because of more rapidly progressing disease, which could reduce screening effectiveness. However, because race is a social rather than biological construct, apparent differences in progression (ie, higher rates of interval cancers or later stage at detection) would likely reflect systematic differences in access to high-quality care (64).

In summary, these analyses find that screening is similarly effective for Black populations compared with White populations, even in the face of changing age-related risk and shifts in tumor location. If equally screened, the US Black population would have a larger CRC incidence reduction than the White population, because of slightly higher risk. This demonstrates that observed Black–White differences in CRC incidence rates are largely driven by screening disparities rather than risk differences. Finally, disparities in all-cause mortality mean that populations with higher mortality have fewer total life-years to be saved, resulting in lower projected screening benefits, potentially biasing policy analyses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The funders had no role in the conduct of this study. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Carolyn M Rutter, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Division of Public Health Sciences, Hutchinson Institute for Cancer Outcomes Research, Seattle, WA, USA.

Pedro Nascimento de Lima, RAND Corporation, Arlington, VA, USA.

Christopher E Maerzluft, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Division of Public Health Sciences, Hutchinson Institute for Cancer Outcomes Research, Seattle, WA, USA.

Folasade P May, Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Division of Digestive Diseases, Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), Los Angeles, CA, USA; Greater Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Healthcare System, Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Los Angeles, CA, USA; UCLA Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Equity, Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Caitlin C Murphy, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health, Houston, TX, USA.

Data Availability

Data used for these analyses are available to researchers via SEER, available at https://seer.cancer.gov/. R code used for APC analyses will be made available to users. Model code is not publicly available, per CISNET policy.

Author contributions

Carolyn M Rutter, PhD (Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Supervision; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing), Pedro Nascimento de Lima, PhD (Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Software; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing), Christopher E. Maerzluft, MS (Formal analysis; Software; Visualization; Writing—review & editing), Folasade P. May, MD, PhD, MPhil (Writing—review & editing), and Caitlin C. Murphy, PhD, MPH, CPH (Writing—review & editing).

Funding

CMR, PNL, and CM were supported by Grant Number U01-CA253913 from the National Cancer Institute as part of the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute. This research used resources of the Argonne Leadership Computing Facility, a DOE Office of Science User Facility supported under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. FPM was supported by National Cancer Institute R01 CA271034, VA IIR Merit I01HX003605, the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center and the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research Ablon Scholars Program. CCM was supported by National Cancer Institute R01CA242558.

Monograph sponsorship

This article appears as part of the monograph “Reducing Disparities to Achieve Cancer Health Equity: Using Simulation Modeling to Inform Policy and Practice Change,” sponsored by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health ([Comparative Modeling of Effective Policies for Colorectal Cancer Control; 3 U01 CA253913-03S1]).

Conflicts of interest

FPM has served as a consultant for Exact Sciences, Freenome, Geneoscopy, and Medtronic. CCM has served as a consultant for Freenome. All of the other authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A.. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(1):7-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siegel RL, Wagle NS, Cercek A, Smith RA, Jemal A.. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(3):233-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Miller KD, Nogueira L, Devasia T, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(5):409-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Singh S, Sridhar P.. A narrative review of sociodemographic risk and disparities in screening, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes of the most common extrathoracic malignancies in the United States. J Thorac Dis. 2021;13(6):3827-3843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chapman C, Jayasekera J, Dash C, Sheppard V, Mandelblatt J.. A health equity framework to support the next generation of cancer population simulation models. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2023;2023(62):255–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL.. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(3):211-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rahman R, Schmaltz C, Jackson CS, Simoes EJ, Jackson‐Thompson J, Ibdah JA.. Increased risk for colorectal cancer under age 50 in racial and ethnic minorities living in the United States. Cancer Med. 2015;4(12):1863-1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Irby K, Anderson WF, Henson DE, Devesa SS.. Emerging and widening colorectal carcinoma disparities between Blacks and Whites in the United States (1975-2002). Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(4):792-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alexander DD, Waterbor J, Hughes T, Funkhouser E, Grizzle W, Manne U.. African-American and Caucasian disparities in colorectal cancer mortality and survival by data source: an epidemiologic review. Cancer Biomark. 2007;3(6):301-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rutter CM, Johnson EA, Feuer EJ, Knudsen AB, Kuntz KM, Schrag D.. Secular trends in colon and rectal cancer relative survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(23):1806-1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lawrence WR, McGee-Avila JK, Vo JB, et al. Trends in cancer mortality among Black individuals in the US from 1999 to 2019. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(8):1184-1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Assari S, Hansen H.. Racial disparities and gastrointestinal cancer—how structural and institutional racism in the US health system fails Black patients. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5(4):e225676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Braveman PA, Arkin E, Proctor D, Kauh T, Holm N.. Systemic and structural racism: definitions, examples, health damages, and approaches to dismantling. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(2):171-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yearby R, Clark B, Figueroa JF.. Structural racism in historical and modern US health care policy. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(2):187-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carethers JM. Racial and ethnic disparities in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. In: Berger FG, Boland CR, ed. Novel Approaches to Colorectal Cancer. Vol. 151. Academic Press; 2021:197-229. doi: 10.1016/bs.acr.2021.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ashktorab H, Kupfer SS, Brim H, Carethers JM.. Racial disparity in gastrointestinal cancer risk. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(4):910-923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. May FP, Yang L, Corona E, Glenn BA, Bastani R.. Disparities in colorectal cancer screening in the United States before and after implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(8):1796-1804.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Burnett-Hartman AN, Mehta SJ, Zheng Y, et al. ; for the PROSPR Consortium. Racial/ethnic disparities in colorectal cancer screening across healthcare systems. Am J Prev Med 2016;51(4):e107-e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu PH, Sanford NN, Liang PS, Singal AG, Murphy CC.. Persistent disparities in colorectal cancer screening: a tell-tale sign for implementing new guidelines in younger adults. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2022;31(9):1701-1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McCarthy AM, Kim JJ, Beaber EF, et al. ; for the PROSPR Consortium. Follow-up of abnormal breast and colorectal cancer screening by race/ethnicity. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(4):507-512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Frankenfeld CL, Menon N, Leslie TF.. Racial disparities in colorectal cancer time-to-treatment and survival time in relation to diagnosing hospital cancer-related diagnostic and treatment capabilities. Cancer Epidemiol. 2020;65:101684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tramontano AC, Chen Y, Watson TR, Eckel A, Hur C, Kong CY.. Racial/ethnic disparities in colorectal cancer treatment utilization and phase-specific costs, 2000-2014. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bliton JN, Parides M, Muscarella P, Papalezova KT, In H.. Understanding racial disparities in gastrointestinal cancer outcomes: lack of surgery contributes to lower survival in African American patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30(3):529-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jones LA, Ferrans CE, Polite BN, et al. Examining racial disparities in colon cancer clinical delay in the Colon Cancer Patterns of Care in Chicago study. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27(11):731-738.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hao SB, Snyder RA, Irish W, Parikh AA.. Explaining disparities in colon cancer treatment: differential effects of health insurance by race. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;231(4):S55-S56. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bui A, Yang L, Myint A, May FP.. Race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status are associated with prolonged time to treatment after a diagnosis of colorectal cancer: a large population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(4):1394-1396.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Muto T, Bussey HJ, Morson BC.. The evolution of cancer of the colon and rectum. Cancer. 1975;36(6):2251-2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Crockett SD, Nagtegaal ID.. Terminology, Molecular features, epidemiology, and management of serrated colorectal neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(4):949-966.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rutter CM, Knudsen AB, Lin JS, Bouskill KE.. Black and White differences in colorectal cancer screening and screening outcomes: a narrative review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30(1):3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Imperiale TF, Abhyankar PR, Stump TE, Emmett TW.. Prevalence of advanced, precancerous colorectal neoplasms in Black and White populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(6):1776-1786.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, Schoenfeld PS, Burke CA, Inadomi JM; for the American College of Gastroenterology Guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2008. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104(3):739-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wolf AMD, Fontham ETH, Church TR, et al. Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(4):250-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Knudsen AB, Rutter CM, Peterse EFP, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: an updated modeling study for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1998-2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Siegel RL, Jemal A, Ward EM.. Increase in incidence of colorectal cancer among young men and women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(6):1695-1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Murphy CC, Wallace K, Sandler RS, Baron JA.. Racial disparities in incidence of young-onset colorectal cancer and patient survival. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(4):958-965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rutter CM, Savarino JE.. An evidence-based microsimulation model for colorectal cancer: validation and application. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(8):1992-2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rutter CM, Ozik J, DeYoreo M, Collier N.. Microsimulation model calibration using incremental mixture approximate Bayesian computation. Ann Appl Stat. 2019;13(4):2189-2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nascimento de Lima P, Rutter CM, Maerzluft C, Ozik J, Collier N. Robustness analysis of colorectal cancer colonoscopy screening strategies. medRxiv; 2023;2023.03.07.23286939. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.03.07.23286939v1. Accessed March 13, 2023.

- 39.National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program SEER 9 Reg Research Data, Nov 2020 Sub (1975-2018). National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program. Released May 17, 2022. https://www.seer.cancer.gov. Accessed July 8, 2022.

- 40. DeYoreo M, Rutter CM, Lee SD.. Two-stage modeling to identify how colorectal cancer risk changes with period and cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2023;192(2):230-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Arias E. United States Life Tables, 2017. National vital statistics reports: from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Natl Vital Stat Syst. 2019;68(7):1-66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ulanja MB, Rishi M, Beutler BD, et al. Colon cancer sidedness, presentation, and survival at different stages. J Oncol. 2019;2019:4315032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lee JM, Han YD, Cho MS, et al. Impact of tumor sidedness on survival and recurrence patterns in colon cancer patients. Ann Surg Treat Res 2019;96(6):296-304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang C, Wainberg ZA, Raldow A, Lee P.. Differences in cancer-specific mortality of right- versus left-sided colon adenocarcinoma: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database analysis. J Clin Oncol Clin Cancer Inform. 2017;1:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Petrelli F, Tomasello G, Borgonovo K, et al. Prognostic survival associated with left-sided vs right-sided colon cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(2):211-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rutter C, Ozik J, Collier N, Maerzluft CE. IMABC: Incremental Mixture Approximate Bayesian Computation (IMABC). 2021. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=imabc. Accessed November 11, 2022.

- 47. Austin G, Kowalkowski H, Guo Y, et al. Patterns of initial colorectal cancer screenings after turning 50 years old and follow-up rates of colonoscopy after positive stool-based testing among the average-risk population. Curr Med Res Opin. 2023;39(1):47-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shapiro JA, Soman AV, Berkowitz Z, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer in the United States: correlates and time trends by type of test. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30(8):1554-1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schottinger JE, Jensen CD, Ghai NR, et al. Association of physician adenoma detection rates with postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2022;327(21):2114-2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhao S, Wang S, Pan P, et al. Magnitude, risk factors, and factors associated with adenoma miss rate of tandem colonoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(6):1661-1674.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Stineman RW. A consistently well-behaved method of interpolation. Creat Comput. 1980;6(7):54-57. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gies A, Niedermaier T, Gruner LF, Heisser T, Schrotz-King P, Brenner H.. Fecal immunochemical tests detect screening participants with multiple advanced adenomas better than T1 colorectal cancers. Multidisciplin Digit Publish Inst. 2021;13(4):644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, et al. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(14):1287-1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Niedermaier T, Balavarca Y, Brenner H.. Stage-specific sensitivity of fecal immunochemical tests for detecting colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(1):56-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. van Turenhout ST, van Rossum LG, Oort FA, et al. Similar fecal immunochemical test results in screening and referral colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(38):5397-5403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gupta S, Lieberman D, Anderson JC, et al. Recommendations for follow-up after colonoscopy and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(3):415-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zorzi M, Hassan C, Capodaglio G, et al. Divergent long-term detection rates of proximal and distal advanced neoplasia in fecal immunochemical test screening programs. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(9):602-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Doubeni CA, Levin TR.. In screening for colorectal cancer, is the fit right for the right side of the colon? Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(9):650-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, et al. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(14):1298-1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mutneja HR, Bhurwal A, Arora S, Vohra I, Attar BM.. A delay in colonoscopy after positive fecal tests leads to higher incidence of colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36(6):1479-1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rutter CM, Inadomi JM, Maerzluft CE.. The impact of cumulative colorectal cancer screening delays: a simulation study. J Med Screen. 2022;29(2):92-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Crockett SD, Barry EL, Mott LA, Snover DC, Wallace K, Baron JA.. Predictors of incident serrated polyps: results from a large multicenter clinical trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2022;31(5):1058-1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ashing KT, Jones V, Bedell F, Phillips T, Erhunmwunsee L.. Calling attention to the role of race-driven societal determinants of health on aggressive tumor biology: a focus on Black Americans. J Clin Oncol Oncol Pract. 2022;18(1):15-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Rutter CM, May FP, Coronado GD, Pujol TA, Thomas EG, Cabreros I.. Racism is a modifiable risk factor: relationships among race, ethnicity, and colorectal cancer outcomes. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(4):1053-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data used for these analyses are available to researchers via SEER, available at https://seer.cancer.gov/. R code used for APC analyses will be made available to users. Model code is not publicly available, per CISNET policy.