The unprecedented decline in transplantation at the start of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic was driven by multiple factors, including constrained health care resources, limited access to testing for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), lack of consistent methods to document and communicate deceased donor testing results, and critically, the fear of disease transmission and adverse recipient outcomes.1,2 With standardization of donor testing, emergence of recipient vaccination, and increasing population prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 exposure, early experience suggested the safety of transplantation of extrapulmonary organs, including kidney allografts from donors with recovered COVID-19.3,4 Selective use of kidney allografts from SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid amplification test (NAT)–positive donors and donors who died from COVID-19 followed at some centers. In January 2023, updated guidance from the American Society of Transplantation concluded that recipients of nonlung organs from SARS-CoV-2 NAT-positive donors have short-term patient and graft survival similar to those who received organs from SARS-CoV-2 NAT-negative donors, on the basis of evidence to date.5 However, uncertainty remained because of the retrospective nature of most available reports, risk for unmeasured confounding with available controls, limited follow-up durations, and lack of granular clinical outcomes data. On this background, a carefully controlled, prospective study published in this issue of CJASN sheds new light on the outcomes of kidney transplantation from SARS-CoV-2–infected donors in contemporary practice.6

In a prospective, observational cohort study of 61 vaccinated recipients from 52 SARS-CoV-2 PCR-positive donors at three US transplant centers, Yamauchi et al. used optimal matching methods to match each recipient to three control recipients from noninfected deceased donors from January 2016 to May 2022 at the same center.6 Final cohorts were well balanced across an array of recipient and donor factors, although year of transplantation in cases and controls was not reported. Among the findings, one recipient from a SARS-CoV-2–infected donor died with graft function at 6 months, but mean 6-month recipient eGFR and patient and graft survival were not significantly different between the well-matched recipients from SARS-CoV-2–infected and noninfected donors. In subgroup analysis, recipients from COVID-19 death donors had significantly lower 6-month eGFR compared with those from SARS-CoV-2–negative donors. On the basis of the primary findings, the authors conclude that this study provides additional evidence supporting the safety and efficacy of transplanting SARS-CoV-2–infected donor kidneys.

This well-conducted study adds important information to the understanding of short-term outcomes of kidney transplant from SARS-CoV-2–infected donors compared with uninfected donors. However, there are caveats to interpretation and application of the study findings to current and future practice. The authors did considerable work to match recipient from SARS-CoV-2–infected donors to recipients from noninfected donors by 12 baseline recipient and donor factors. This process achieved good matching for the included factors, such as average Kidney Donor Profile Index, and accounted for donation after cardiac death donors (31% among both groups). Of note, the controls were retrospectively sampled, and the time of transplant (e.g., month, year) is not reported. During the rapidly evolving pandemic, mismatch in transplant date could result in differences in center COVID-19–related protocols and other practices.

Importantly, the subgroup of donors with death attributed to COVID-19 included only 15 patients. The 45 controls (three per case) were statistically similar to the cases but included numerical differences in measured factors after matching, such as recipient sex (7% versus 42% female), pretransplant dialysis duration (27% versus 13% preemptive; 0% versus 16% with dialysis >5 years), zero HLA mismatch (7% versus 0%), and donation after cardiac death (73% versus 40%). The number of characteristics compared for this sample is also a limited subset of the measured factors, leaving comparability for other characteristics unknown. Some of the factors with unknown certainty of matching in the subgroup include donor age, percentage of glomerulosclerosis, donor history of hypertension, and diabetes. Only two centers contributed to the subgroup with donor COVID-19 death, where one center used tacrolimus and the other used belatacept as the main immunosuppressive medication. Given the small number of donors with COVID-19 death from two centers, the numerical differences of several factors, and the limited matching of donor factors, concluding that kidneys from donors with COVID-19 death yield lower eGFR at 6 months compared with non-COVID-19 death requires additional confirmation in larger, controlled studies.

These new prospective data build on evidence from previous publications. A recent large, retrospective study of US transplant registry data by Ji et al. that included 2915 kidney transplant recipients from active SARS-CoV-2–positive donors found similar graft survival (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.03; 95% confidence interval, 0.78 to 1.37) and patient survival (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.17; 95% confidence interval, 0.84 to 1.66) compared with recipients from SARS-CoV-2–negative donors over 2 years of follow-up.7 One notable feature of the study by Ji et al. was donor classification according to the date of SARS-CoV-2 testing. SARS-CoV-2 NAT positivity within 1 week of the procurement date was classified as active COVID-19, while positive NAT results >7 days before procurement was defined as resolved COVID-19. In the current study by Yamauchi et al., data were not provided on the date of donor SARS-CoV-2 testing, and the mean days between start of COVID-19 symptoms and organ procurement was 26 days (interquartile range, 17–32). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines would classify many of these cases as remote, without active disease at the time of donation.8 More granular data on the period between the date of SARS-CoV-2 testing, organ procurement date, and transplant outcomes would be useful to transplant clinicians in future studies.

The new study also adds to the growing evidence on the safety of transplanting kidneys from donors with SARS-CoV-2 from a disease transmission perspective. Nine recipients in the cohort developed COVID-19, but all cases occurred beyond 10 days post-transplant and were determined not to be donor-derived. Of 45 patients who underwent SARS-CoV-2 NAT testing within 30 days of transplant, only one patient tested positive. This patient tested positive 6 days post-transplant but confirmed negative by day 12 and never developed COVID-19 symptoms. Kidneys from active COVID-19 donors have a higher risk of nonutilization compared with kidneys from SARS-CoV-2–negative donors. While the likelihood of nonuse has declined with time, from 11 times the odds in 2020 to two-fold odds in 2021, kidneys from active COVID-19 donors still had 47% higher likelihood of nonuse in 2022.7 The work by Yamauchi et al.6 supports consideration of opportunities for better utilization of these organs, at a time when optimizing the use of all available organs for patients who can benefit is a vital national priority.

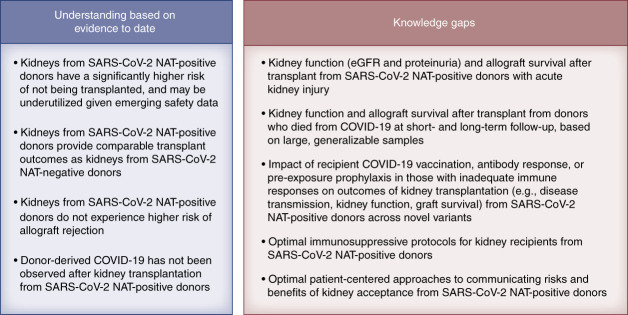

Understanding of the risks and outcomes of kidney transplantation from SARS-CoV-2–infected deceased donors has substantially advanced since the emergence of COVID-19, but many knowledge gaps remain (Figure 1). All recipients in the study by Yamauchi et al. were vaccinated before transplant, with 97% having received at least two doses of mRNA vaccines.6 The ongoing emergence of novel variants of the SARS-CoV-2 highlights the importance of prevention and adherence to current vaccinations among transplant candidates before transplant and immunosuppression.9 New variants may have increased transmissibility, high disease severity, and decreased response to treatments, and the community should advocate for inclusion of immunocompromised patients in studies of vaccines and therapeutics. Transplant providers should also carefully evaluate the kidneys from donors with COVID-19 for significant proteinuria or unexplained kidney injury before organ acceptance. Patient-centered education to effectively communicate the risks and benefits of accepting transplants from donors with COVID-19 should be developed. As COVID-19 moves from a pandemic to an endemic disease, decision making regarding acceptance of kidneys from SARS-CoV-2–infected deceased donors will remain a timely priority that must be supported by ongoing assessment of lessons learned to continue to refine future practice.10 At this time, we believe organ acceptance from donors with COVID-19 may proceed with caution for vaccinated recipients who receive patient-centered education. Ongoing data collection, analysis, and reporting from retrospective and high-quality prospective experience such as the work by Yamauchi et al.6 remain critical to guide the best use of available kidneys while protecting patient safety, even in the midst of novel and evolving public health challenges.

Figure 1.

Current understanding of the risks and outcomes of kidney transplantation from SARS-CoV-2–infected deceased donors. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; NAT, nucleic acid amplification test; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Acknowledgments

The content of this article reflects the personal experience and views of the authors and should not be considered medical advice or recommendation. The content does not reflect the views or opinions of the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) or CJASN. Responsibility for the information and views expressed herein lies entirely with the authors.

Footnotes

See related Patient Voice, “Should I Take a Transplant Kidney from a Person with COVID Infection?,” and article, “Comparison of Short-Term Outcomes in Kidney Transplant Recipients from SARS-CoV-2–Infected versus Noninfected Deceased Donors,” on pages 1383–1384 and 1466–1475, respectively.

Disclosures

T. Alhamad reports consultancy for CareDx, Natera, and Veloxis; research funding from Angion, CareDx, CSL Imagine, Eldon, Eurofins, and Natera; honoraria from CareDx, Sanofi, and Veloxis; personal fees from CareDx, Eurofins, Horizon, Natera, Sanofi, and Veloxis; advisory or leadership roles for CareDx, Europhines, Horizon, and QSANT; and speakers bureau for CareDx, Sanofi, and Veloxis. K.L. Lentine reports consultancy for CareDx, Inc., ownership interest in CareDx, Inc., and speakers bureau for Sanofi.

Funding

K.L. Lentine: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK120551) and Mid-America Transplant Foundation. T. Alhamad: Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Tarek Alhamad, Krista L. Lentine.

Methodology: Tarek Alhamad, Krista L. Lentine.

Writing – original draft: Tarek Alhamad, Krista L. Lentine.

References

- 1.Lentine KL, Mannon RB, Josephson MA. Practicing with uncertainty: kidney transplantation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;77(5):777–785. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lentine KL Singh N Woodside KJ, et al. COVID-19 test result reporting for deceased donors: emergent policies, logistical challenges, and future directions. Clin Transplant. 2021;35(5):e14280. doi: 10.1111/ctr.14280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kute VB, Fleetwood VA, Meshram HS, Guenette A, Lentine KL. Use of organs from SARS-CoV-2 infected donors: is it safe? A contemporary review. Curr Transplant Rep. 2021;8(4):281–292. doi: 10.1007/s40472-021-00343-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Axelrod DA Ince D Harhay MN, et al. Operational challenges in the COVID-19 era: asymptomatic infections and vaccination timing. Clin Transplant. 2021;35(11):e14437. doi: 10.1111/ctr.14437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Society of Transplantation (AST) Infectious Disease Community of Practice (IDCOP). SARS-CoV-2: Recommendations and Guidance for Organ Donor Testing and Evaluation; 2023. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.myast.org/sites/default/files/Donor%20Testing%20Document1.18.23.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamauchi J Azhar A Hall IE, et al. Comparison of short-term outcomes in kidney transplant recipients from SARS-CoV-2–infected versus noninfected deceased donors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023;18(11):1466–1475. doi: 10.2215/CJN.0000000000000275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ji M Vinson AJ Chang SH, et al. Patterns in use and transplant outcomes among adult recipients of kidneys from deceased donors with COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(5):e2315908. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.15908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Isolation and Precautions for COVID-19. Updated May 11, 2023. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/your-health/isolation.html [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hippen BE Axelrod DA Maher K, et al. Survey of current transplant center practices regarding COVID-19 vaccine mandates in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2022;22(6):1705–1713. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar V Leigh KA Kliger AS, et al. Kidney transplant practice in pandemic times: lessons learned for the future. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023;18(7):961–964. doi: 10.2215/CJN.0000000000000092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]