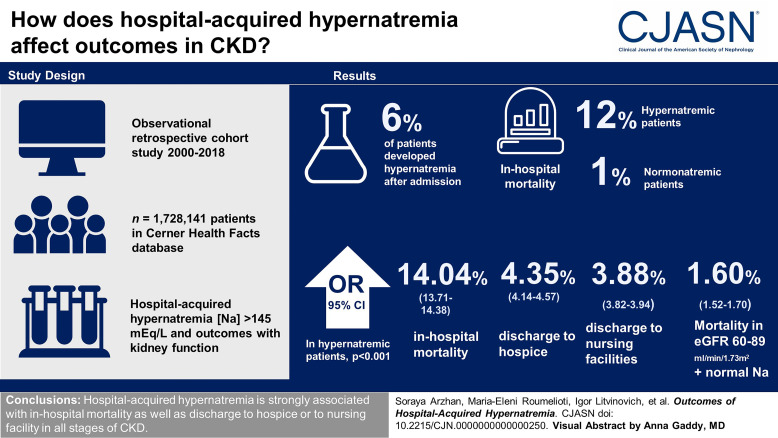

Visual Abstract

Keywords: AKI, CKD, chronic kidney failure, ESKD, GFR, hypernatremia

Abstract

Background

Hospital-acquired hypernatremia is highly prevalent, overlooked, and associated with unfavorable consequences. There are limited studies examining the outcomes and discharge dispositions of various levels of hospital-acquired hypernatremia in patients with or without CKD.

Methods

We conducted an observational retrospective cohort study, and we analyzed the data of 1,728,141 patients extracted from the Cerner Health Facts database (January 1, 2000, to June 30, 2018). In this report, we investigated the association between hospital-acquired hypernatremia (serum sodium [Na] levels >145 mEq/L) and in-hospital mortality or discharge dispositions with kidney function status at admission using adjusted multinomial regression models.

Results

Of all hospitalized patients, 6% developed hypernatremia after hospital admission. The incidence of in-hospital mortality was 12% and 1% in patients with hypernatremia and normonatremia, respectively. The risk of all outcomes was significantly greater for serum Na >145 mEq/L compared with the reference interval (serum Na, 135–145 mEq/L). In patients with hypernatremia, odds ratios (95% confidence interval) for in-hospital mortality, discharge to hospice, and discharge to nursing facilities were 14.04 (13.71 to 14.38), 4.35 (4.14 to 4.57), and 3.88 (3.82 to 3.94), respectively (P < 0.001, for all). Patients with eGFR (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) 60–89 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and normonatremia had the lowest odds ratio for in-hospital mortality (1.60 [1.52 to 1.70]).

Conclusions

Hospital-acquired hypernatremia is associated with in-hospital mortality and discharge to hospice or to nursing facilities in all stages of CKD.

Introduction

Dysnatremia is a common electrolyte imbalance in hospitalized patients. However, hypernatremia is less prevalent compared with hyponatremia.1–3 The prevalence of hypernatremia among hospitalized patients has been reported to be between 1% and 6%.4–7 Outcomes of hypernatremia have also been less studied, and most studies examined selected patient populations.1,4,8–10 In addition, there are limited studies regarding hospital-acquired hypernatremia11 and patients' kidney function at admission.

Hypernatremia can be community-acquired or hospital-acquired. In most previous studies, there have been limitations in the selection of clinical settings, such as inpatient or outpatient,1,7,12 which gave rise to variations in the estimate of the prevalence of hypernatremia.13,14 In addition, little is known about the association between hospital-acquired hypernatremia and discharge dispositions, specifically discharge to hospice and nursing facility, which are key patient-centered outcomes. Furthermore, most of the studies around hypernatremia and selected outcomes were single-center studies with limited sample sizes.

Impairment in kidney function may be related to hospital-acquired hypernatremia. It is not surprising that AKI, characterized by an abrupt reduction in kidney function, is commonly associated with electrolyte imbalances.15 A previous study by Kovesdy et al. demonstrated a linear diminish in the hypernatremia-related mortality rate with more advanced stages of CKD.2,3 Substantial knowledge gaps remain regarding prognostic implications of hospital-acquired hypernatremia as related to the level of kidney function in hospitalized patients.14

The lack of population-based evidence supports the need to evaluate the relationship of hospital-acquired hypernatremia to outcomes and discharge dispositions among hospitalized patients with various levels of acute and/or chronic kidney dysfunction. In this cohort study from a large national database of over 600 hospitals in the United States, we investigated the correlation of hospital-acquired hypernatremia and its outcomes and discharge dispositions in hospitalized patients deeming the status of kidney function and eGFR.

Methods

We conducted an observational retrospective cohort study of patients hospitalized between January 1, 2000, and June 30, 2018, using the Cerner Health Facts database. The Institutional Review Board of the University of New Mexico approved this study protocol (Institutional Review Board: 19-429).

We defined the index hospital admission as the first inpatient encounter during the study period for patients who met the following inclusion criteria: (1) age 18 years or older, (2) patients who had their first serum Na levels during admission or up to 24 hours after admission and was within normal range (135–145 mEq/L), and (3) patients who had at least one serum Na measurement >145 mEq/L (defined as hypernatremia) after hospital admission for patients who met the second inclusion criterion. The second inclusion criterion reduces the likelihood that serum Na can be affected by chronic conditions before hospital admission. For patients with more than one hospitalization during the study period, we selected the first hospitalization that met our inclusion criteria. Patients who developed hyponatremia during their hospitalization were excluded from this analysis.

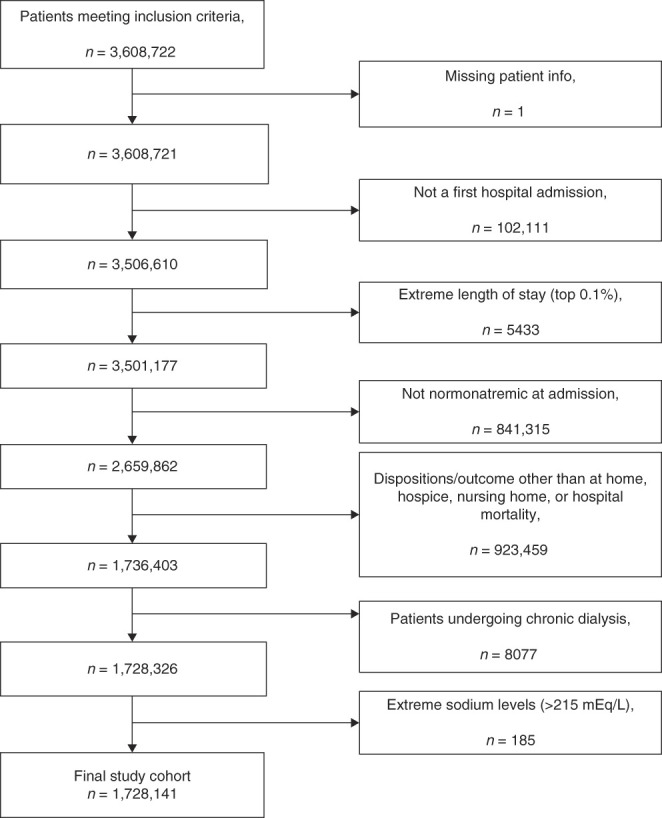

The primary outcomes were determined as in-hospital mortality, discharge disposition of hospitalized patients (hospice, nursing facility, and home), and length of stay. We excluded patients with missing eGFR and serum Na values or discharge dispositions other than home, hospice, or nursing facilities. Furthermore, we excluded patients on long-term dialysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the sample selection process and exclusion criteria. Boxes on the right side represent the exclusion criteria applied to this study.

We discretized serum Na levels into four categories: (1) normonatremia: 135–145 mEq/L (reference category); (2) mild hypernatremia: 145<Na≤150 mEq/L; (3) moderate hypernatremia: 150<Na≤155 mEq/L; and (4) severe hypernatremia: Na >155 mEq/L. The first in-hospital measured serum Na above 145 mEq/L defined the severity of hypernatremia for each patient included in the analyses. We corrected the first inpatient serum Na levels >145 mEq/L by adding 1.6 mEq/L for each 100 mg/dl above 100 mg/dl of the concomitantly measured serum glucose levels.16–18

Patient demographics, comorbidities, causes of admission, laboratory studies, and disposition status at hospital discharge were collected. Comorbidities were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9 and ICD-10 CM) codes. Laboratory tests were identified using Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes.19 The Quan–Charlson Comorbidity Index (Quan-CCI)—a comorbidity index adapted from the Charlson Comorbidity Index for administrative databases—was also calculated.20

Kidney function was estimated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation (version without race) to calculate their estimated eGFR at admission.21 We categorized eGFR levels into five different groups: eGFR ≥90 (referent category), eGFR 60–89, eGFR 30–59, eGFR 15–29, and eGFR <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2. CKD stage was ascertained by hospital-assigned ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes, including CKD stages G1–G2 (with eGFR >60 ml/min per 1.73 m2); patients with CKD stage 5/kidney failure on long-term dialysis were not included in this analysis. AKI was defined according to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes criteria22 as an increase in serum creatinine (and, hence, calculated admission eGFR) over 0.3 mg/dl within 48 hours or an increase in serum creatinine to over 1.5 times the baseline serum creatinine (and, hence, calculated admission eGFR) known or presumed to have occurred within the previous 7 days. Kidney function status was defined as having normal kidney function, CKD, AKI, or AKI on CKD on admission.

Statistical Analyses

Categorical variables were expressed as percentages, and continuous variables were summarized as mean±SD or as medians and interquartile ranges if distributions were skewed. Patient characteristics in normonatremic and different hypernatremic (mild, moderate, and severe) patient groups were compared using Kruskal–Wallis tests for continuous variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables.

The relationship between serum Na levels and multiple disposition outcomes were evaluated using multinomial logistic regression model analysis while accounting for the competing risks of in-hospital mortality and other dispositions. Discharge to home was used as the reference outcome. For a descriptive, graphical analysis, we used restricted cubic splines in the model to estimate probabilities for in-hospital mortality, discharge to hospice, and discharge to nursing facility across the continuous range of serum Na levels. Analysis models without and with covariates were fitted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and the total Quan-CCI score. A separate sensitivity analysis was performed with advanced CKD (stages 3–5) hospitalized patients with CKD diagnosis on the basis of ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes.

Potential effect modification of the relationship between eGFR and outcomes by serum Na was assessed by adding serum Na category×eGFR category interactions to models. The other potential effect modification of the relationship between kidney function status (acute versus chronic) and outcomes by serum Na was assessed by adding serum Na category×kidney dysfunction category interactions to models.

Finally, we assessed the relationships between serum Na levels and length of hospitalization (days) among those who were discharged home. The distribution was right-skewed, so log-transformed days were used in linear models of length of stay adjusted for the Quan-CCI taking an approach that followed our multinomial logistic regression analyses. We reported regression coefficients from the models to summarize the magnitude of the effect on log-transformed days. Moreover, we tested for the differential effect of eGFR and also kidney function classification on these associations. All statistical analyses were performed using R programming language (version 3.6.3).

Results

A total number of 3,608,722 patients met our inclusion criteria. The final cohort included 1,728,141 patients (Figure 1). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Of the selected study population, 6% developed hospital-acquired hypernatremia. Patients who developed hospital-acquired hypernatremia were significantly older and had lower eGFR at admission compared with patients with normonatremia (Table 1). All patient characteristics were significantly different between patients with hypernatremia and normonatremia.

Table 1.

Characteristics of hospitalized patients with normonatremia and hospital-acquired hypernatremia

| Patient Characteristics n=1,728,141 | Normonatremia n=1,622,201 | Hypernatremia n=105,940 |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 57 (±19) | 66 (±18) |

| Female | 870,386 (54) | 56,424 (53) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| Black | 220,052 (14) | 17,936 (17) |

| Asian | 24,497 (2) | 1812 (2) |

| White | 1,226,325 (76) | 76,039 (72) |

| Hispanic | 28,814 (2) | 1589 (2) |

| Native American | 13,584 (0.8) | 1342 (1) |

| Pacific Islander | 2518 (0.2) | 108 (0.1) |

| Others | 65,492 (4) | 4432 (4) |

| Quan-CCI categories, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 639,992 (40) | 20,953 (20) |

| 1–2 (mild) | 392,690 (24) | 28,511 (27) |

| 3–4 (moderate) | 162,582 (10) | 18,612 (18) |

| ≥5 (severe) | 128,303 (8) | 22,008 (21) |

| Quan-CCI score | 1.54 (±2) | 2.9 (±3) |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 68 (±27) | 55 (±26) |

| CKD-EPI eGFR | 85 (±28) | 65 (±31) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||

| CKD stages 1–4 | 42,318 (3) | 7950 (8) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 243,693 (15) | 34,965 (33) |

| Hypertension | 525,153 (32) | 39,607 (37) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 263,048 (16) | 24,391 (23) |

| Heart failure | 114,585 (7) | 18,0544 (17) |

| Liver disease | 35,597 (2) | 5029 (5) |

| Dementia | 20,500 (1) | 4270 (4) |

| Diuretic use | 281,534 (17) | 37,931 (36) |

| Leading diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| AKI | 75,702 (5) | 23,761 (22) |

| Head trauma | 22,515 (1) | 2559 (2) |

| Ischemic stroke | 35,599 (2) | 4194 (4) |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 4566 (0.3) | 1503 (1 |

| Laboratory blood tests | ||

| Glucose, mg/dl | 126 (±51) | 218 (±163) |

| Total protein, g/dl | 7.0 (±0.8) | 6.8 (±1.0) |

| Albumin, g/dl | 3.8 (±0.6) | 3.6 (±0.7) |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.1 (±0.8) | 1.5 (±1.3) |

| BUN, mg/dl | 17 (±11) | 27 (±18) |

| Osmolality, mOsm/L | 289 (±25) | 315 (±26) |

| Sodium, mEq/L | 140 (±2) | 148 (±4) |

| Potassium, mEq/L | 4.0 (±0.5) | 4.2 (±0.8) |

Continuous variables are expressed as means (±SD) and categorical variables as number of patients (n) and percentages (%). Normonatremia: [Na]: 135–145 mEq/L; hypernatremia: [Na]: >145 mEq/L, first [Na] levels >145 mEq/L corrected by adding 1.6 mEq/L for each 100 mg/dl above 100 mg/dl of the concomitantly measured serum glucose levels. Quan-CCI, Quan–Charlson Comorbidity Index; CKD-EPI, Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration.

The risk of outcomes was significantly higher for patients with hospital-acquired hypernatremia compared with hospitalized patients who remained normonatremic. The incidence of in-hospital mortality was 12% and 1% in patients with hypernatremia and normonatremia, respectively. The relative frequency of discharge to hospice in patients with hypernatremia and normonatremia was 12% and 0.6%, respectively. The relative frequency of discharge to nursing facilities in patients with hypernatremia and normonatremia was 25% and 9%, respectively. Frequencies of outcomes by hypernatremia status and eGFR/kidney condition categories are summarized in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

Natremia Status and Outcomes

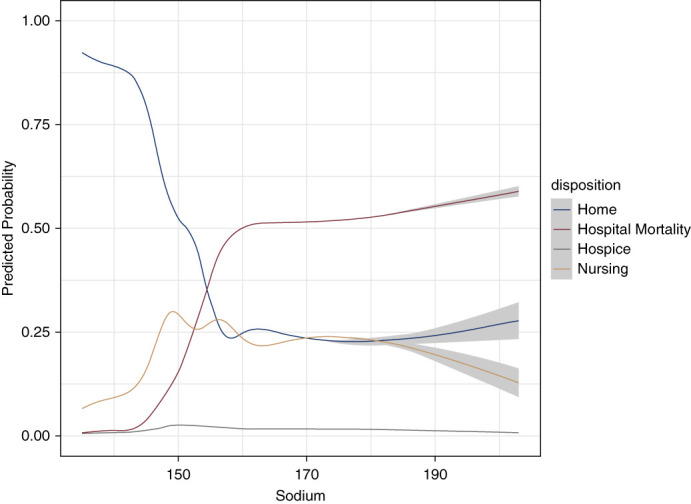

The crude probability of in-hospital mortality was lowest among patients with normonatremia and was observed to be higher for serum Na above this range (Figure 2). The estimated probability of discharge to nursing facility showed a bimodal pattern with two peaks at serum Na levels 150 and 155 mEq/L and was lower with serum Na above 155 mEq/L. The in-hospital increase in serum Na above 145 mEq/L was followed by a sharply lower probability of discharge to home. Discharge to hospice was slightly higher among patients with mild hypernatremia and then remained steady for hospitalized patients with moderate or severe hypernatremia (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Restricted cubic splines of the crude probability of in-hospital mortality, discharge to hospice, discharge to home, and discharge to nursing facility as a function of serum sodium levels during hospital stay. Estimated probabilities were derived from a multinomial logistic regression model.

For the various serum Na categories, in the adjusted multinomial logistic regression analysis, we found that the odds ratios (ORs) for in-hospital mortality became significantly higher with higher serum Na levels. Similar trends were observed for discharge to hospice and discharge to nursing facility (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relationships between serum sodium levels and outcomes stratified by eGFR

| Natremia Status | In-Hospital Mortality (n=32,591) | Discharge to Hospice (n=11,818) | Discharge to Nursing Facility (n=178,887) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | OR (95% CI)a | n (%) | OR (95% CI)a | n (%) | OR (95% CI)a | ||

| Normonatremia | 19,973 (61) | Reference | 9884 (84) | Reference | 152,298 (85) | Reference | |

| HyperNa | Mild | 6752 (21) | 5.77 (5.58 to 5.97) | 1512 (13) | 2.45 (2.31 to 2.6) | 21,600 (12) | 2.61 (2.56 to 2.67) |

| Moderate | 3295 (10) | 37.67 (35.65 to 39.81) | 334 (3) | 7.28 (6.43 to 8.24) | 3734 (2) | 6.73 (6.38 to 7.09) | |

| Severe | 2571 (8) | 179.49 (165 to 195.26) | 88 (0.7) | 12.75 (10.03 to 16.19) | 1255 (0.7) | 16.02 (14.55 to 17.63) | |

| eGFR | |||||||

| NormoNa | <15 | 1312 (4) | 10.22 (9.42 to 11.1) | 293 (3) | 1.03 (0.89 to 1.18) | 2557 (1.) | 1.12 (1.06 to 1.19) |

| 15–29 | 2833 (9) | 6.12 (5.71 to 6.56) | 731 (6) | 0.59 (0.53 to 0.66) | 9727 (5) | 1.12 (1.08 to 1.15) | |

| 30–59 | 6598 (20) | 2.61 (2.46 to 2.76) | 2616 (22) | 0.5 (0.46 to 0.54) | 47,399 (27) | 0.95 (0.94 to 0.97) | |

| 60–89 | 6058 (19) | 1.6 (1.52 to 1.7) | 3474 (29) | 0.57 (0.53 to 0.61) | 62,215 (35) | 0.9 (0.88 to 0.91) | |

| ≥90 | 3166 (10) | Reference | 2769 (23) | Reference | 30,390 (17) | Reference | |

| Mild HyperNa | <15 | 375 (1) | 15.83 (13.81 to 18.14) | 84 (0.7) | 1.25 (0.95 to 1.64) | 1085 (0.6) | 2.48 (2.26 to 2.72) |

| 15–29 | 971 (3) | 16 (14.55 to 17.6) | 216 (2) | 1.57 (1.34 to 1.84) | 3230 (2) | 2.94 (2.78 to 3.12) | |

| 30–59 | 2425 (7) | 13.02 (12.14 to 13.97) | 523 (4) | 1.27 (1.13 to 1.42) | 7983 (5) | 2.32 (2.24 to 2.41) | |

| 60–89 | 1882 (6) | 12.53 (11.65 to 13.47) | 438 (4) | 1.86 (1.66 to 2.1) | 6447 (4) | 2.36 (2.27 to 2.45) | |

| ≥90 | 1095 (3) | 13.02 (11.97 to 14.15) | 251 (2) | 2.75 (2.36 to 3.2) | 2854 (2) | 2.72 (2.59 to 2.86) | |

| Moderate HyperNa | <15 | 145 (0.4) | 55.5 (43.88 to 70.2) | 25 (0.2) | 4.93 (3.19 to 7.62) | 299 (0.2) | 5.28 (4.29 to 6.5) |

| 15–29 | 449 (1) | 65.57 (56.43 to 76.19) | 69 (0.6) | 3.19 (2.3 to 4.43) | 734 (0.4) | 6.27 (5.49 to 7.15) | |

| 30–59 | 1133 (4) | 74.28 (67.14 to 82.17) | 112 (0.9) | 2.96 (2.3 to 3.81) | 1325 (0.7) | 5.55 (5.07 to 6.07) | |

| 60–89 | 949 (3) | 93.34 (83.59 to 104.2) | 79 (0.7) | 3.98 (2.97 to 5.34) | 919 (0.5) | 5.76 (5.17 to 6.41) | |

| ≥90 | 617 (2) | 108.5 (96.35 to 122.2) | 49 (0.4) | 10.47 (7.75 to 14.15) | 457 (0.3) | 6.1 (5.33 to 6.98) | |

| Severe HyperNa | <15 | 65 (0.2) | 98.66 (65.99 to 147.5) | 11 (0.1) | 3.92 (1.33 to 11.53) | 107 (0.1) | 13.55 (9.5 to 19.3) |

| 15–29 | 245 (0.8) | 88.67 (71.14 to 110.5) | 14 (0.1) | 0.32 (0.06 to 1.8) | 205 (0.1) | 5.88 (4.7 to 7.4) | |

| 30–59 | 693 (2) | 280.61 (239.8 to 328.4) | 32 (0.3) | 5.67 (3.54 to 9.09) | 422 (0.2) | 12.43 (10.5 to 14.7) | |

| 60–89 | 830 (2) | 666.36 (561.9 to 790.2) | 22 (0.2) | 9.33 (5.21 to 16.7) | 302 (0.2) | 17.09 (14.0 to 20.9) | |

| ≥90 | 738 (2) | 718.23 (608.4 to 847.95) | 9 (0.1) | 23.39 (13.47 to 40.62) | 219 (0.1) | 27.13 (22.2 to 33.2) | |

eGFR was calculated using the race-free Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation. Patients were classified in the database according to the reported International Classification of Diseases-10 codes for kidney function. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; HyperNa, hypernatremia; NormoNa, normonatremia.

Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

In patients with hypernatremia, ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for in-hospital mortality, discharge to hospice, and discharge to nursing facilities were 14.04 (95% CI, 13.71 to 14.38), 4.35 (95% CI, 4.14 to 4.57), and 3.88 (95% CI, 3.82 to 3.94), respectively (P < 0.001, for all).

There was a significant association between serum Na categories and length of hospitalization. These relationships are summarized in Table 3. For those discharged to their homes, median length of stay was 2.8 (interquartile range, 1.9–4.2) days. Length of stay was shortest for hospitalized patients with normonatremia.

Table 3.

Relationships between serum sodium levels during hospital admission and length of hospitalization among those discharged to home stratified by eGFR

| Hypernatremia Categories | Length of Stay among those Discharged Home (n=1,345,650) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Coefficient (95% CI) | ||

| Normonatremia | 2.8 (1.9–4.1) | Reference | |

| Hypernatremia | Mild | 4.1 (2.7–6.7) | 0.33 (0.33 to 0.34) |

| Moderate | 5.0 (2.9–9.2) | 0.47 (0.45 to 0.49) | |

| Severe | 5.9 (3.5–11.4) | 0.58 (0.54 to 0.62) | |

| eGFR | |||

| Normonatremia | <15 | 3.2 (2.1–5.1) | 0.16 (0.15 to 0.18) |

| 15–29 | 3.1 (2.1–4.8) | 0.12 (0.11 to 0.14) | |

| 30–59 | 2.9 (1.9–4.3) | 0.04 (0.04 to 0.05) | |

| 60–89 | 2.7 (1.8–4.1) | −0.01 (−0.01 to 0.0) | |

| ≥90 | 2.7 (1.9–4.0) | Reference | |

| Mild hypernatremia | <15 | 4.9 (3.2–7.4) | 0.44 (0.40 to 0.47) |

| 15–29 | 4.4 (2.9–6.9) | 0.37 (0.35 to 0.40) | |

| 30–59 | 4.1 (2.7–6.5) | 0.33 (0.32 to 0.35) | |

| 60–89 | 4.1 (2.6–6.4) | 0.32 (0.31 to 0.34) | |

| ≥90 | 4.1 (2.7–6.8) | 0.35 (0.34 to 0.36) | |

| Moderate hypernatremia | <15 | 6.1 (4.0–9.6) | 0.57 (0.49 to 0.66) |

| 15–29 | 5.5 (3.2–8.9) | 0.50 (0.44 to 0.56) | |

| 30–59 | 4.2 (2.8–8.0) | 0.41 (0.38 to 0.45) | |

| 60–89 | 5.0 (2.9–10.0) | 0.50 (0.46 to 0.54) | |

| ≥90 | 5.6 (2.9–10.8) | 0.52 (0.48 to 0.57) | |

| Severe hypernatremia | <15 | 7.4 (5.1–10.3) | 0.65 (0.50 to 0.80) |

| 15–29 | 5.4 (3.9–8.8) | 0.55 (0.45 to 0.65) | |

| 30–59 | 4.9 (3.0–9.7) | 0.51 (0.43 to 0.58) | |

| 60–89 | 6.1 (3.3–13.4) | 0.62 (0.53 to 0.71) | |

| ≥90 | 7.4 (4.1–15.1) | 0.69 (0.61 to 0.77) | |

IQR, interquartile range; CI, confidence interval.

Kidney Function and Outcomes

eGFR and Outcomes

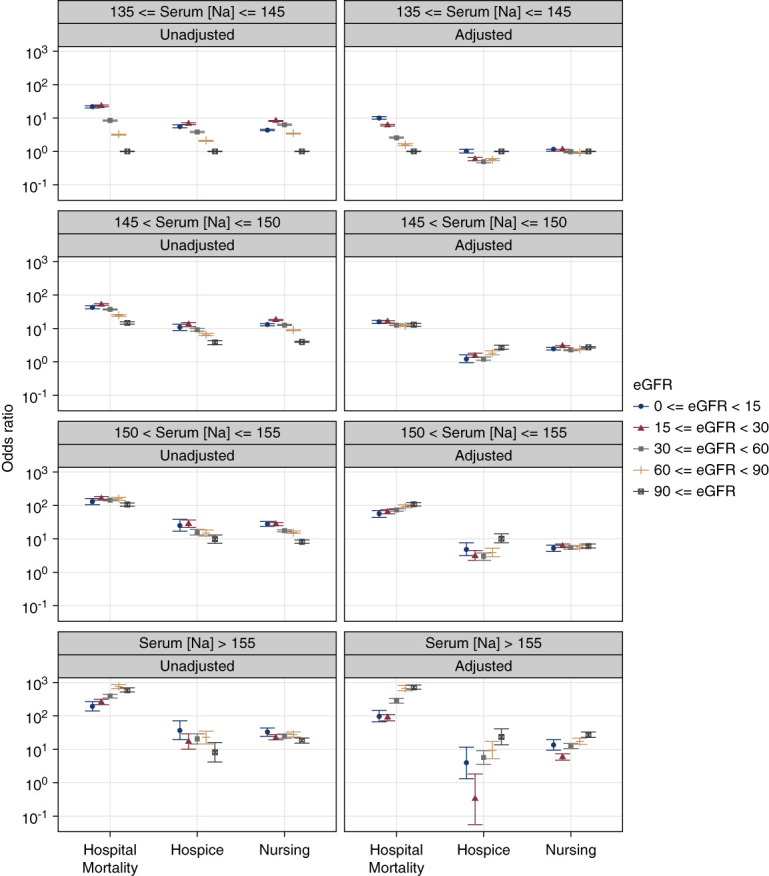

The main interaction test between eGFR levels and serum Na categories demonstrated a significant association between these two factors and in-hospital mortality. Generally, crude ORs of in-hospital mortality were higher with higher serum Na levels relative to the 135–145 mEq/L interval (reference group). However, this relationship was observed as slightly different patterns for each hypernatremic group (Figure 3, Table 2). Adjusted models showed that the ORs of in-hospital mortality became significantly higher as serum Na increased >145 mEq/L and eGFR decreased <90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 compared with the reference groups (serum Na interval and eGFR ≥90 ml/min per 1.73 m2). Different trends were observed for each serum Na category (Figure 3, Table 2).

Figure 3.

Plots of ORs for in-hospital mortality, discharge to hospice, or discharge to nursing facility associated with different intervals of serum sodium levels during hospital stay and stratified by eGFR levels. The ORs were derived from multinomial logistic regression models adjusted for age, sex, race, selected comorbidities, and reasons for hospitalization. Discharge to home and serum sodium levels of 135–145 mEq/L served as referent. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

In unadjusted models, discharge to hospice showed the same trend as for in-hospital mortality. The highest ORs in normonatremia and mild hypernatremia were observed with eGFR 15–29 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and in moderate and severe hypernatremia with eGFR <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2. In all serum Na categories, the lowest ORs of discharge to hospice were observed with eGFR ≥90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (Figure 3). Adjusted models showed different patterns in each serum Na category (Figure 3, Table 2). The highest OR was observed among discharge to hospice patients with moderate hypernatremia and eGFR ≥90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (10.478 [95% CI, 7.75 to 14.15]). In severe hypernatremia, the lowest OR for discharge to hospice was observed with eGFR 15–29 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and in mild and moderate hypernatremia with eGFR 30–59 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (Figure 3, Table 2).

Regarding discharge to nursing facilities, unadjusted and adjusted models showed an inconsistent pattern deeming eGFR categories. In adjusted models, the highest ORs were observed among patients with severe hypernatremia and eGFR ≥90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (16.02 [95% CI, 14.55 to 17.63]) (Figure 3, Table 2).

The longest length of stay was observed with eGFR <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 in all serum Na categories (Table 3, Supplemental Figure 1).

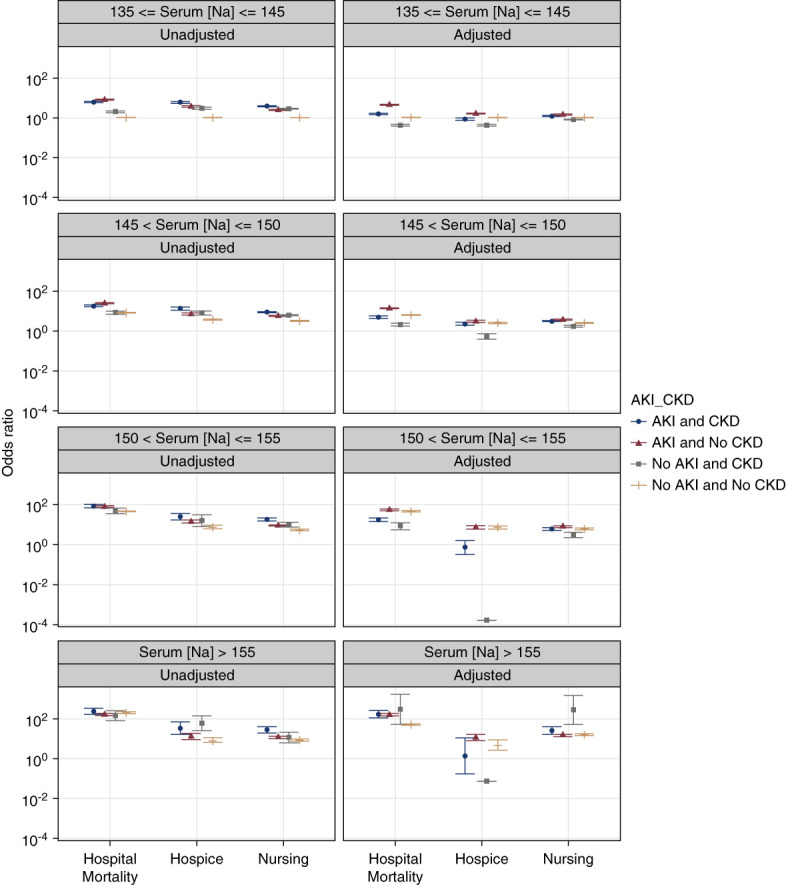

Kidney Function Classification and Outcomes

Regarding kidney function status (acute versus chronic), in crude models, the highest mortality rate in patients with normonatremia, mild hypernatremia, and moderate hypernatremia was observed among patients with AKI and without CKD.

In adjusted models, we found that among patients with severe hypernatremia, the highest in-hospital mortality rate was observed among patients with CKD (Figure 4, Table 4). The highest mortality rate in adjusted models was observed among non-CKD patients with AKI and normonatremia or mild or moderate hypernatremia. The odds of discharge to hospice and nursing facilities are presented in Figure 4 and Table 4. A sensitivity analysis of advanced CKD (stages 3–5) hospitalized patients with CKD diagnosis using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes did not reveal statistically significant differences for outcomes independent of the level of hypernatremia.

Figure 4.

Plots of ORs for in-hospital mortality, discharge to hospice, or discharge to nursing facility associated with different intervals of serum sodium levels during hospital stay stratified by kidney dysfunction status. The ORs were derived from multinomial logistic regression models adjusted for age, sex, race, selected comorbidities, and reasons for hospitalization. Discharge to home and normal serum sodium levels of 135–145 mEq/L served as referent. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Table 4.

Relationships between serum sodium levels and outcomes stratified by kidney function status

| Natremia Status | Kidney Function Status | In-Hospital Mortality (n=27,482) | Discharge to Hospice (n=10,238) | Discharge to Nursing Facility (n=153,695) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | OR (95% CI)a | n (%) | OR (95% CI)a | n (%) | OR (95% CI)a | ||

| NormoNa | Normal | 11,719 (43) | Reference | 6718 (66) | Reference | 109,546 (71) | Reference |

| CKD | 429 (2) | 0.42 (0.38 to 0.47) | 371 (4) | 0.42 (0.38 to 0.47) | 5767 (4) | 0.82 (0.79 to 0.85) | |

| AKI | 3905 (14) | 4.43 (4.26 to 4.61) | 1021 (10) | 1.63 (1.52 to 1.75) | 11,022 (7) | 1.47 (1.43 to 1.51) | |

| AKI on CKD | 692 (3) | 1.5 (1.38 to 1.63) | 384 (4) | 0.86 (0.77 to 0.96) | 3980 (3) | 1.22 (1.17 to 1.27) | |

| Mild HyperNa | Normal | 3312 (12) | 6.21 (5.95 to 6.48) | 830 (8) | 2.45 (2.27 to 2.64) | 12,334 (8) | 2.5 (2.44 to 2.57) |

| CKD | 134 (0.5) | 2.07 (1.74 to 2.46) | 74 (0.7) | 0.55 (0.39 to 0.76) | 921 (0.6) | 1.71 (1.56 to 1.88) | |

| AKI | 1929 (7) | 13.81 (13.03 to 14.64) | 321 (3) | 3.01 (2.66 to 3.40) | 4174 (3) | 3.64 (3.48 to 3.80) | |

| AKI on CKD | 355 (1) | 4.95 (4.39 to 5.59) | 147 (1) | 2.27 (1.91 to 2.70) | 1581 (1) | 3.07 (2.84 to 3.32) | |

| Moderate HyperNa | Normal | 1561 (6) | 46.97 (43.77 to 50.4) | 148 (1) | 7.33 (6.15 to 8.75) | 1697 (1) | 6.18 (5.76 to 6.63) |

| CKD | 48 (0.2) | 8.46 (5.64 to 12.7) | 9 (0.1) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 90 (0.1) | 3.14 (2.29 to 4.31) | |

| AKI | 1031 (4) | 55.59 (50.57 to 61.1) | 107 (1) | 7.39 (5.92 to 9.23) | 1107 (0.7) | 8.17 (7.44 to 8.98) | |

| AKI on CKD | 183 (0.7) | 17.59 (14.21 to 21.76) | 31 (0.3) | 0.73 (0.33 to 1.64) | 368 (0.2) | 6.09 (5.08 to 7.30) | |

| Severe HyperNa | Normal | 1374 (5) | 287.69 (258.49 to 320.19) | 30 (0.3) | 4.71 (2.58 to 8.59) | 522 (0.3) | 15.74 (13.82 to 17.93) |

| CKD | 29 (0.1) | 300.4 (53.59 to 1683.92) | 7 (0.1) | 0.07 (0.07 to 0.07) | 22 (0.0) | 282.09 (53.99 to 1473.98) | |

| AKI | 672 (2) | 160.01 (139.18 to 183.95) | 31 (0.3) | 11.6 (7.96 to 16.91) | 443 (0.3) | 14.9 (12.76 to 17.41) | |

| AKI on CKD | 109 (0.4) | 171.2 (112.47 to 260.59) | 9 (0.1) | 1.35 (0.17 to 10.72) | 121 (0.1) | 25.1 (16.27 to 38.71) | |

eGFR was calculated using the race-free Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation. Patients were classified in the database according to the reported International Classification of Diseases-10 codes for kidney function. The AKI on CKD group had an inflated eGFR because of their AKI status compared with their initial CKD classification. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; NormoNa, normonatremia; HyperNa, hypernatremia.

Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

In this diverse cohort study from a large database of over 600 hospitals in the United States, we found that 6% of patients diagnosed as normonatremic at admission developed hypernatremia during hospitalization. In our study, hospital-acquired hypernatremia was associated with higher mortality rate compared with normonatremia. Finally, patients with hospital-acquired hypernatremia had higher odds of discharge to hospice and discharge to a nursing facility.

This report confirms previous observations relating hospital-acquired hypernatremia and its severity to mortality in hospitalized patients1,4,7,10,11 and extends previous research by examining discharge dispositions. Our findings for increment of in-hospital mortality along with the increase in the severity of hypernatremia are similar to other studies.1,4,7,9–11,23 In line with our results, previous studies by Hu et al.7,23 in China and Funk et al.12 in Austria demonstrated that there are independent associations between hypernatremia and the risk of in-hospital mortality even after adjusting for potential confounding factors. This is especially true for patients admitted with dysnatremias in the intensive care unit.

Furthermore, the results of this report demonstrated that eGFR at admission was significantly lower in patients with hypernatremia compared with patients with normonatremia. Regarding the different levels of hypernatremia stratified by eGFR levels, we observed that by increasing serum Na levels and decreasing the eGFR level, the risk of outcomes was higher. However, after stratifying each hypernatremia group by eGFR, we could not observe a consistent pattern in the risk of outcomes. In mild hypernatremia groups, the highest odds of in-hospital mortality were observed with eGFR <15. For the severe hypernatremia group, the highest odds of in-hospital mortality were observed with eGFR ≥90 and the lowest odds with eGFR <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Tsipotis et al.1 showed that the highest ORs of in-hospital mortality in patients with hospital-acquired hypernatremia on admission were observed among those with eGFR 30–59 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Han et al.24 investigated the associations between serum Na levels and CKD and observed that hypernatremia in patients with CKD in the outpatient setting were both short- and long-term risk factors of mortality. Chiu et al.25 reported no significant association between hypernatremia and mortality in an outpatient population with CKD. Sun et al. also found that the stage of CKD did not seem to affect the mortality associated with hypernatremia.26 However, Kovesdy et al.2 demonstrated that more advanced CKD displayed a relatively lower mortality associated with hypernatremia compared with patients with less severe stages of CKD.

A caveat that needs attention in our work is the ascertainment of CKD classification by the use of hospitalized ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes. Back in 2000 (starting year of data retrieval for this analysis), ICD codes were relatively new and CKD as a diagnosis was underreported, especially mild CKD. Therefore, the prevalence of CKD stages 1–4 reported herein may be undercounted. Nevertheless, an existing diagnostic code for CKD may reflect that the hospitalized patient had previous care and available records, which may, in part, explain why the risk of in-hospital mortality was lower for patients with CKD and no AKI/no hypernatremia.

The fact that our inpatient study population suffered more acute conditions could be a major determinant of our findings. Furthermore, the physiologic plausibility of our findings relies on the strategic role the kidney plays in sodium and water homeostasis. In early stages of CKD, hyponatremia is more common than hypernatremia. In more advanced stages of CKD, water handling becomes more impaired and hypernatremia is more common.27 When eGFR drops below 30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, the risk of mortality seems to become the highest.14,27 The age distribution of hospital-acquired hypernatremia is usually similar to that of the general hospitalized population. Both the kidneys and the brain collaborate to regulate hospital-acquired hypernatremia. When the kidneys function relatively normal, iatrogenic or central nervous system causes should be considered. Inadequate and inappropriate prescription of fluids to patients with predictably increased water losses and impaired thirst and/or restricted free water intake may result in iatrogenic hospital-acquired hypernatremia, and the treatment is often inadequate or delayed.28,29

Regarding age, in our study, patients who developed hospital-acquired hypernatremia were older compared with patients with normonatremia. However, age was less important in the multivariable model after accounting for CKD status. It is well known that hypernatremia mostly results from net water loss reflecting pure water or hypotonic fluid loss, while thirst provides the ultimate defense against developing hypernatremia assuming the ability to access water. Therefore, hypernatremia in adults largely occurs in older patients with infirmity, cognitive deficits, or altered mental status who depend on others for their water requirements.1,30 Thirst is also suppressed in older patients. However, hypernatremia can result from hypertonic sodium gain30 during hospitalization as well and may be iatrogenic. A recent study showed that a greater volume of free water prescription was associated with progression to severe hospital-acquired hypernatremia.11 The prescribed amount of free water was considered inadequate in the context of ongoing use of sodium-rich solutions and lower total volumes during progression of hypernatremia. Finally, hypernatremia is frequently associated with increased extracellular fluid volume, even outside intensive care units.9

Our study has several strengths. First, this study is notable for its large sample size and the event quantity, which can be representative of the entire patient population of the United States. To the best of our knowledge, the association between hospital-acquired hypernatremia and its outcomes (i.e., in-hospital mortality and discharge dispositions) has not been studied systematically at a large population level. In addition, we addressed a key gap in knowledge regarding the relationship between different levels of hospital-acquired hypernatremia and selected outcomes deeming kidney function level in a large diverse population. Furthermore, we corrected [Na] for hyperglycemia, an adjustment necessary for determining the true prevalence and severity of hypernatremia.

Our study has several limitations as well. First, we were unable to include a disease severity scoring modality, such as the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation or Sequential Organ Failure Assessment. However, this study included the identification of comorbidities (including CKD) and reasons for hospitalization using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes to account for the presence of medical conditions. This may have underestimated the reported CKD prevalence. We were also able to adjust for the Quan-CCI, which has been widely used to predict survival of hospitalized and critically ill patients.20 Second, we did not look for precedence of hypernatremia by AKI or vice versa because this was not the primary aim of this study. There is also the potential of AKI misclassification because of the definition we used. This may have affected the estimated cross-associations of dysnatremia and AKI with the reported outcomes. This study took a parsimonious approach to explore how the other factors can participate in outcomes of iatrogenic hypernatremia. We did not look at patients' diagnoses. However, we looked for predictors of development of iatrogenic hypernatremia in baseline characteristics in a large group of hospitalized individuals. Some eligible patients had multiple admissions. However, they were excluded from the statistical analyses. Finally, because of the observational nature of our study, we cannot obviate the possibility of residual confounding and cannot draw any causal interpretations from our results. However, conducting large randomized controlled trials to overcome this limitation may not be easily practicable. We believe that this last limitation should not undermine the importance of the finding that hospital-acquired hypernatremia, regardless of the cause, is significantly associated with higher in-hospital mortality and discharge to nursing home or hospice.

In our study, we found that all levels of hospital-acquired hypernatremia were independently associated with higher odds of in-hospital mortality, discharge to hospice, and discharge to nursing facilities of the patients. The strength of this association suggests that hypernatremia may serve as a widely available risk factor of poor outcomes among hospitalized patients. These findings underscore the need for more awareness of hospital-acquired hypernatremia, especially among patients with advanced kidney dysfunction, and may provide the opportunity to prevent and minimize subsequent adverse outcomes. Further work focusing on prevention, duration, and rate of correction of hospital-acquired hypernatremia are crucial next steps because treatment of hypernatremia may be inadequate or delayed. Finally, physician training to promote awareness and the development of hospital-based algorithms to prevent fluid prescription errors could result in improved management and even avoidance of hospital-acquired hypernatremia.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

See related editorial, “Incident Hypernatremia in Hospitalized Patients: Risk Factor for Poor Outcomes or Merely the Shadows in Plato's Cave?,” on pages 1385–1387.

Disclosures

C.G. Bologa reports employment with and consultancy for Roivant Sciences and research funding from Givaudan Flavors. M.-E. Roumelioti reports participating in DCI quality meetings and receiving financial support. M.-E. Roumelioti's spouse reports consultancy for Baxter, Bayer, Integrity, Otsuka, and Quanta. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

S. Arzhan: Dialysis Clinics (3RGX8-FP00007518. Study ID: C4165).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Soraya Arzhan, Cristian G. Bologa, Maria-Eleni Roumelioti, Mark L. Unruh.

Data curation: Igor Litvinovich.

Formal analysis: Igor Litvinovich.

Funding acquisition: Soraya Arzhan, Mark L. Unruh.

Methodology: Soraya Arzhan, Cristian G. Bologa, Igor Litvinovich, Maria-Eleni Roumelioti.

Project administration: Mark L. Unruh.

Resources: Mark L. Unruh.

Software: Cristian G. Bologa, Igor Litvinovich.

Supervision: Maria-Eleni Roumelioti, Mark L. Unruh.

Validation: Cristian G. Bologa, Igor Litvinovich, Mark L. Unruh.

Visualization: Cristian G. Bologa.

Writing – original draft: Soraya Arzhan.

Writing – review & editing: Soraya Arzhan, Maria-Eleni Roumelioti, Mark L. Unruh.

Data Sharing Statement

All data are included in the manuscript and/or supporting information.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://links.lww.com/CJN/B809.

Supplemental Table 1. Profile of serum sodium levels and outcomes stratified by eGFR.

Supplemental Table 2. Profile of serum sodium levels and outcomes stratified by kidney dysfunction status.

Supplemental Figure 1. Plot of relationships between serum sodium levels during hospital stay and length of hospitalization among those discharged to home stratified by eGFR.

References

- 1.Tsipotis E, Price LL, Jaber BL, Madias NE. Hospital-associated hypernatremia spectrum and clinical outcomes in an unselected cohort. Am J Med. 2018;131(1):72–82.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kovesdy CP Lott EH Lu JL, et al. Hyponatremia, hypernatremia, and mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease with and without congestive heart failure. Circulation. 2012;125(5):677–684. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.111.065391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kovesdy CP. Significance of hypo- and hypernatremia in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(3):891–898. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salahudeen AK, Doshi SM, Shah P. The frequency, cost, and clinical outcomes of hypernatremia in patients hospitalized to a comprehensive cancer center. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(7):1871–1878. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1734-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turgutalp K Özhan O Gök Oğuz E, et al. Community-acquired hypernatremia in elderly and very elderly patients admitted to the hospital: clinical characteristics and outcomes. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18(12):CR729–734. doi: 10.12659/msm.883600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Girardeau Y, Jannot AS, Chatellier G, Saint-Jean O. Association between borderline dysnatremia and mortality insight into a new data mining approach. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2017;17(1):152. doi: 10.1186/s12911-017-0549-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu J Wang Y Geng X, et al. Dysnatremia is an independent indicator of mortality in hospitalized patients. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:2408–2425. doi: 10.12659/msm.902032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han SS, Bae E, Kim DK, Kim YS, Han JS, Joo KW. Dysnatremia, its correction, and mortality in patients undergoing continuous renal replacement therapy: a prospective observational study. BMC Nephrol. 2016;17(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s12882-015-0215-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Felizardo Lopes I, Dezelée S, Brault D, Steichen O. Prevalence, risk factors and prognosis of hypernatraemia during hospitalisation in internal medicine. Neth J Med. 2015;73(10):448–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waite MD, Fuhrman SA, Badawi O, Zuckerman IH, Franey CS. Intensive care unit-acquired hypernatremia is an independent predictor of increased mortality and length of stay. J Crit Care. 2013;28(4):405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ranjan R, Lo SCY, Ly S, Krishnananthan V, Lim AKH. Progression to severe hypernatremia in hospitalized general medicine inpatients: an observational study of hospital-acquired hypernatremia. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020;56(7):358. doi: 10.3390/medicina56070358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Funk GC Lindner G Druml W, et al. Incidence and prognosis of dysnatremias present on ICU admission. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(2):304–311. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1692-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liamis G, Rodenburg EM, Hofman A, Zietse R, Stricker BH, Hoorn EJ. Electrolyte disorders in community subjects: prevalence and risk factors. Am J Med. 2013;126(3):256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.06.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan S, Floris M, Pani A, Rosner MH. Sodium and volume disorders in advanced chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2016;23(4):240–246. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2015.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lombardi G, Ferraro PM, Naticchia A, Gambaro G. Serum sodium variability and acute kidney injury: a retrospective observational cohort study on a hospitalized population. Intern Emerg Med. 2021;16(3):617–624. doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02462-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120(4):c179–c184. doi: 10.1159/000339789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz MA. Hyperglycemia-induced hyponatremia--calculation of expected serum sodium depression. N Engl J Med. 1973;289(16):843–844. doi: 10.1056/nejm197310182891607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hillier TA, Abbott RD, Barrett EJ. Hyponatremia: evaluating the correction factor for hyperglycemia. Am J Med. 1999;106(4):399–403. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00055-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huff SM Rocha RA McDonald CJ, et al. Development of the logical observation identifier Names and codes (LOINC) vocabulary. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998;5(3):276–292. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1998.0050276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quan H Li B Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676–682. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arzhan S, Lew SQ, Ing TS, Tzamaloukas AH, Unruh ML. Dysnatremias in chronic kidney disease: pathophysiology, manifestations, and treatment. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:769287. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.769287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delgado C Baweja M Crews DC, et al. A unifying approach for GFR estimation: recommendations of the NKF-ASN task force on reassessing the inclusion of race in diagnosing kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022;79(2):268–288.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu B Han Q Mengke N, et al. Prognostic value of ICU-acquired hypernatremia in patients with neurological dysfunction. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(35):e3840. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000003840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han SW Tilea A Gillespie BW, et al. Serum sodium levels and patient outcomes in an ambulatory clinic-based chronic kidney disease cohort. Am J Nephrol. 2015;41(3):200–209. doi: 10.1159/000381193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chiu DYY, Kalra PA, Sinha S, Green D. Association of serum sodium levels with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in chronic kidney disease: results from a prospective observational study. Nephrology (Carlton). 2016;21(6):476–482. doi: 10.1111/nep.12634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun L, Hou Y, Xiao Q, Du Y. Association of serum sodium and risk of all-cause mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease: a meta-analysis and sysematic review. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):15949. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16242-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimizu T Terao M Hara H, et al. Dysnatremia in renal failure. Contrib Nephrol. 2018;196:229–236. doi: 10.1159/000485727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palevsky PM, Bhagrath R, Greenberg A. Hypernatremia in hospitalized patients. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124(2):197–203. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-2-199601150-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seay NW, Lehrich RW, Greenberg A. Diagnosis and management of disorders of body tonicity-hyponatremia and hypernatremia: core curriculum 2020. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(2):272–286. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adrogué HJ, Madias NE. Hypernatremia. New Engl J Med. 2000;342(20):1493–1499. doi: 10.1056/nejm200005183422006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are included in the manuscript and/or supporting information.