Abstract

Primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) is a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in which the brain, spinal cord, leptomeninges and/or eyes are exclusive sites of disease. The pathophysiology of PCNSL is incompletely understood, but a central role seems to immunoglobulins binding to self-proteins expressed in the CNS and alterations of genes involved in B-cell receptor, toll-like receptor and NF-κB signaling. Other factors such as T-cells, macrophages/microglia, endothelium, chemokines and interleukins probably also have important roles. Presentation varies depending on the involved regions of the CNS. Standard of care includes methotrexate-based polychemotherapy followed by age-tailored thiotepa-based conditioned autologous stem cell transplantation (HDC-ASCT), and in patients unsuitable for HDC-ASCT, consolidation with whole-brain irradiation or single-drug maintenance. Personalized treatment, primary radiotherapy and only supportive care should be considered in unift, frail patients. Despite available treatments, 15–25% of patients do not respond to chemotherapy and 25–50% relapse after initial response. Relapse rates are higher in older patients, although prognosis of relapsed patients is poor independent of age. Further research is needed to identify diagnostic biomarkers, more efficacious and less neurotoxic treatments, strategies to improve penetration of drugs into the CNS, and immunotherapies and adoptive cell therapies.

Introduction

The 2017 WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues recognized a distinct entity termed ‘primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the CNS (PCNSL)’1, which exhibits some unique biological, molecular, and clinical properties. In the 2022 edition of the WHO Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours2, this neoplasm is classified in the ‘Large B-cell lymphomas of immune-privileged sites’ group, whereas it is considered a specific entity in the International Consensus Classification of Mature Lymphoid Neoplasms3.

PCNSL is a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) occurring exclusively in the brain, spinal cord, cranial nerves, leptomeninges, and/or eyes. Most cases of relapsed disease occur in these organs, although rare cases can relapse outside the CNS. The brain parenchyma is the most common location1. PCNSL should be distinguished from lymphoma categories other than DLBCL primary arising in the CNS and from the secondary CNS lymphomas, which are diagnosed in patients with systemic DLBCL who have CNS involvement. This distinction is clearly stated in recent interventional prospective trials, whereas some former cumulative case series or retrospective studies addressing molecular, radiologic, and clinical findings as well as analyzing selected subgroups of patients often included different lymphoma categories arising in or disseminating to the CNS. Conclusions from these retrospective studies should be taken into account with caution considering that PCNSL and other CNS lymphoma categories display remarkably different biological, molecular and clinical findings.

The incidence of PCNSL has increased in the last 50 years, particularly among elderly individuals4. Nevertheless, the molecular and genetic profiles of PCNSL are poorly understood compared with those of nodal DLBCL, mostly due to its rarity and paucity of available biological samples for molecular and biological analyses. B cells are only very rarely found in CNS parenchyma, and PCNSL occurs in organs with structural, biological, and immunological characteristics that strongly influence tumor behavior and both treatment choice and efficacy5. This disorder can result in rapid impairment of neurological functions and performance status (PS is a score that estimates the patient’s ability to perform certain activities of daily living without the help of others), hindering timely diagnosis6. Diagnosis of PCNSL has improved in the past few years, leading to faster diagnosis and improved outcomes7, 8. Moreover, the molecular profile of PCNSL has been better characterized, which had a positive effect on diagnosis and recognition of potential therapeutic targets. Furthermore, consensus is increasing regarding the optimal treatments of PCNSL, which emphasizes the important role of referral centers. However, despite these advances, PCNSL still has one of the worst prognoses among all non-Hodgkin lymphomas9, although it is important to recognize that it is a curable brain tumor.

This Primer summarizes the molecular pathogenesis, diagnosis, clinical behavior, prognosis, and treatment of PCNSL in immunocompetent patients. Moreover, this Primer reviews the role of modern neuroimaging, diagnostic biomarkers, management of intraocular and leptomeningeal diseases, as well as the effects of treatment on cognitive functions and quality of life. Important ongoing clinical and biological studies and endpoints for future trials are also discussed.

Epidemiology

PCNSL comprises ~4% of all primary CNS tumors and 4–6% of all extranodal lymphomas10. The annual incidence from nationwide population-based studies is between 0.3 and 0.6 cases 100,000 persons11. Incidence in the USA has increased 5-fold from 1975 to 2017; these data are consistent with several studies in other countries11–16, although some studies found an ever higher incidence in some countries/regions, for example Finland17. The incidence of PCNSL varies significantly by age; patients >60 years of age have the highest growth in incidence over the last four decades18, 19 with an incidence of 4.32 cases per 100,000 persons in patients aged 70–79 years18. The cause of this general increase is unclear. In recent large cohorts, the median age at diagnosis of PCNSL is approximately 67 years9, 13, 16. A wide international study reported 75 cases of PCNSL diagnosed in children and adolescents, but only half of them had a DLBCL, suggesting that other lymphoma entities can arise in the CNS in this age setting, with a higher incidence among males and subjects affected by immunodeficiency syndromes20. Several studies have demonstrated a higher incidence of PCNSL in men than in women12, 14.

PCNSL is considered an AIDS-defining cancer, and incidence is 5,000-fold higher in subjects living with HIV (PLWH) compared with the general population21. The incidence of PCNSL in PLWH has decreased dramatically since the introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy in the 1990’s21 from 5 cases per 1,000 persons-year in 1991–1994 (pre-antiretroviral therapy era) to 0.32 cases per 1,000 persons-year after 1999, globally22. The prevalence of PCNSL is 6.1% in PLWH, although it is variable among geographical locations; one meta-analysis of 27 studies demonstrated a prevalence of 3.6% in India, 16.5% in the USA after 2000, 5.7% in Europe, 2.2% in East Asia, and 7.3% in South America23.

Patients receiving prolonged immunosuppressive agents (such as those undergoing solid organ transplantation or those with autoimmune disorders) are the major at-risk population for PCNSL (Patient and disease characteristics of PCNSL in immunosuppressed patients are reported in Box 1)24. Risk factors for PCNSL in those without evident immunosuppression have not been identified. Dense use of GSM cellular phone was proposed as risk factor25; however, no link between brain tumours and cellular phone use has been determined. Unconfirmed small studies have suggested an association between PCNSL and tonsillectomy or oral contraceptives use26.

Box 1. Patient and disease characteristics of PCNSL in immunocompromised individuals.

PCNSL is diagnosed early in immunocompromised subjects, with a median age of 30 years, and a male/female ratio of 7.4. Mental status changes is the most common presentation, usually with a short interval between the symptoms onset and diagnosis (median 1–2 months). Half of patients have multifocal disease, with cerebrospinal dissemination in 25% of patients22.

PCNSL is the 2nd malignancy after skin cancer in organ transplant recipients. It is usually a rapidly progressive EBV+ B-cell lymphoma, diagnosed at a median age of 23 years. PCNSL incidence is higher in Asians/Pacific Islanders than non-Hispanic whites (aIRR = 2.09); after induction immunosuppression with alemtuzumab (aIRR = 3.12), monoclonal antibodies (aIRR = 1.83), or polyclonal antibodies (aIRR = 2.03); in recipients who were EBV-seronegative at the time of transplant and at risk of primary infection (aIRR = 1.95); and within the first 1.5 years after transplant24.

Owing to its rarity, characterization of the immunobiological features of PCNSL after immunosuppression (PLWH and those receiving solid organ transplants) remains minimal. However, malignant B cells are typically positive for the lymphotropic Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which is termed EBV-associated PCNSL227. One study evaluated the genetic landscape and tumor microenvironment (TME) of 91 PCNSL patients using targeted sequencing and digital multiplex gene expression228. This study found a different pattern of genetic mutations in EBV-positive PCNSL, with no MYD88, CD79B, and PIM1 mutations found in these cases. Moreover, copy number loss was uncommon in HLA class I/II alleles of EBV-positive PCNSL (only 10% HIV-positive and 13% in PTLD), which contrast with the 43% recorded in EBV-negative PCNSL.

The microenvironment in PCNSL in immunocompromised patients with EBV infection differs from the microenvironment in non-immunosuppressed people with PCNSL. Digital gene expression analysis showed an elevated levels of TNF-a, CD68, CD163, PD-L1, PD-L2, LAG-3, and TIM-3 in EBV-positive post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD), indicative of a tolerogenic TME in this subset228. Moreover, EBV-positive HIV-positive PCNSL cases had low levels of CD4+ and macrophage markers CD68 and CD163 compared with non-HIV-related PCNSL.

Mechanisms/pathophysiology

Genetic alterations

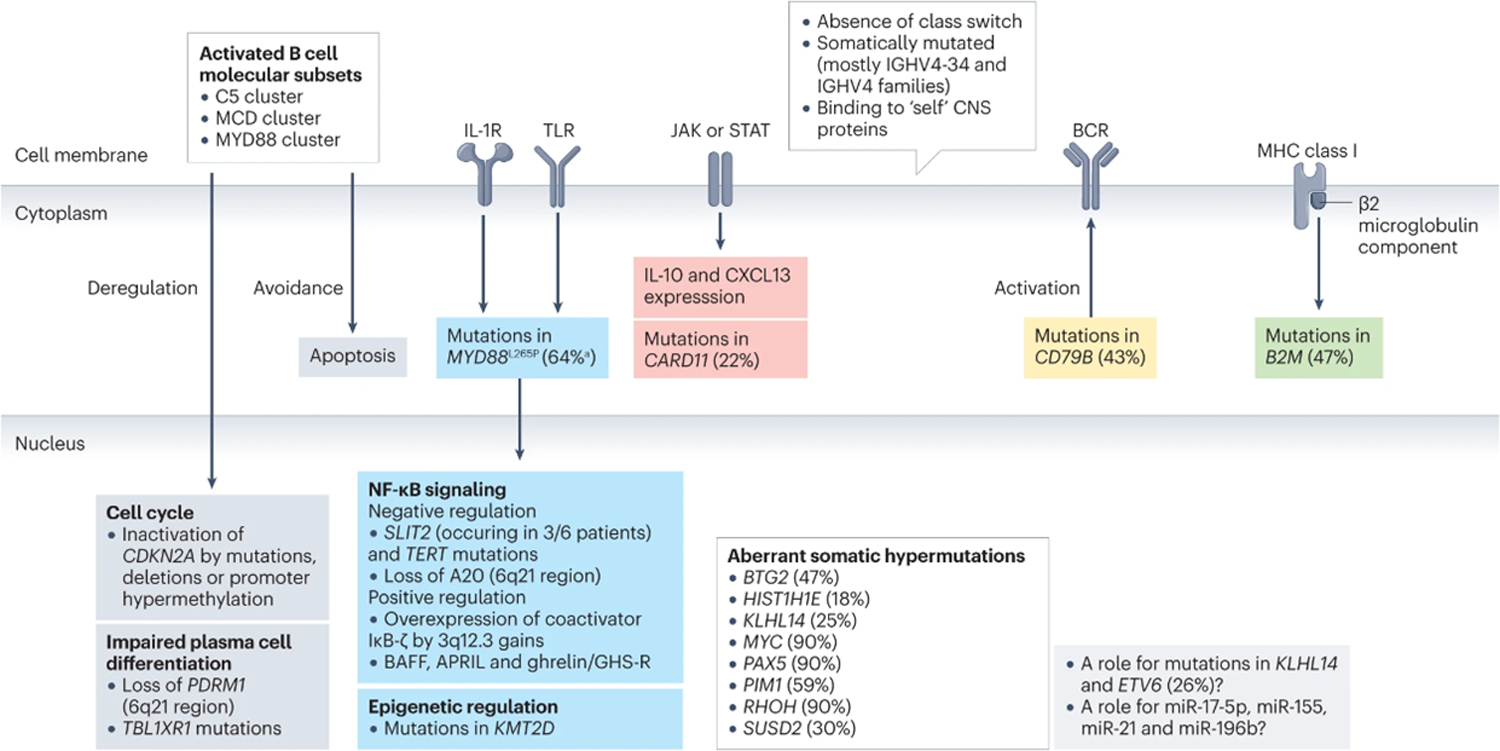

PCNSL harbour somatic mutations in genes encoding immunoglobulins, mostly involving IGHV4–3427–31. Aberrant somatic hypermutation affects other genes (Figure 3) including BTG2 (encoding a transcriptional coregulator)32, H1–4 (also known as HIST1H1E; encoding part of histone H1.4)32, KLHL14 (encoding substrate adaptor for Cullin 3 ubiquitin ligases)32, MYC (encoding a protein involved in cell cycle, cell growth, apoptosis, cellular metabolism and biosynthesis, adhesion, and mitochondrial biogenesis), PAX5 (encoding a B-cell transcription factor), PIM132 (encoding a serine-threonine kinase involved in apoptosis, cell cycle progression and transcriptional activation), RHOH (encoding a GTPase that negatively regulates cell growth and survival), or SUSD2 (encoding a negative regulator of cell cycle)28, 33–35.

Figure 3: Biological and molecular propertiers of neoplastic cells in PCNSL.

Molecular features intrinsic to neoplastic cells in PCNSL involve receptors, intracytoplasmic pathways as well as a variety of mechanism including cell cyle, cell differentiation, NF-kB signaling, somatic hypermutations, and epigenetics.

Systemic DLBCL are prognostically subdivided into germinal center B-cell like (GCB) and activated B-cell like (ABC) subgroups according to the expression profiles defining the cell of origin36. Moreover, several studies have identified a systemic DLBCL ABC subtype – known as C537, MYD88L265P and CD79B mutated (MCD)38 or MYD88 cluster39. Most PCNSL display a non-GCB phenotype40, 41 although without prognostic implications41, 42. In addition, many alterations in PCNSL are shared with the MCD cluster of the ABC subgroup. For example, the L265P mutation in MYD88 activates the B-cell receptor (BCR), toll-like receptors (TLRs) and NF-κB signaling, and synergistically with CD79B, blocks terminal B-cell differentiation, deregulates the cell cycle, and promotes immune escape and prevents apoptosis of B cells43. Similarly, mutations in KLHL1432 promote the assembly of the MY-T-BCR supercomplex (comprising MYD88, TLR9 and BCR), which activates NF-κB signaling44. Moreover, CARD11 interacts with the NF-kB complex; in fact, CARD11 gain-of-function mutations can stimulate constitutive NF-κB activity and induce proliferation of invasive B-cell lymphocytes45 and ETV632 acts as a transcriptional repressor, while its mutations predispose to both lymphoid and myeloid hematological malignancies37, 38.

Constitutive activation of the BCR/TLR/NF-κB signaling in PCNSL relies on several genetic events. Mutations in CD79B (mostly Y196N, Y196D, Y196C, Y196H and Y196S9) and MYD88 (mostly L265P) usually occur simultaneously46 along with mutations in PIM1 (encoding a protein involved in lymphomagenesis)32, 47. Recurrent gains at 3q12.3 (which occur in 45% of patients with PCNSL) induce overexpression of NFKBIZ (encoding the NF-κB co-activator IκB-ζ)39. Mutations in SLIT2 inactivate NFKBIZ and lead to negative regulation of NF-κB signaling48. TERT (encodingtelomerase reverse transcriptase, an NF-κB target and NF-κB cofactor) mutations also occur in PCNSL49. Activation of the NF-κB pathway may be caused by overexpression of BAFF (B-cell activating factor of the tumor necrosis factor family), APRIL, and ghrelin/GHS-R (growth hormone secretagogue receptor) axis50. Loss of 6q21 leads to loss of TNFAIP3 (encoding A20, a negative regulator of NF-κB) and PDRM1 (encoding for the plasma cell master regulator BLIMP1). PDRM1 can also be mutated in PCNSL, and its mutations deregulate B-cell terminal differentiation51–53. Of note, overexpression of some genes is associated with outcome; for example, high-density of phosphorylated STAT6 expression by dense clusters of tumor cells has been reported in patients experiencing worse outcome54.

PCNSL also share other features with the C5/MCD/MYD88 cluster: CDKN2A inactivation55–58, which can occur by mutations (present in 28% of CDKN2A inactivated cases), deletions or is mediated by promoter hypermethylation56, 59; the relative absence of mutations in genes encoding epigenetic regulators (EZH2, CREBBP and EP300), with the exception of KMT2D34, 57, 60; lower frequency of TP53 mutations than systemic DLBCL; and a lower rate of MYC and BCL2 rearrangements respect to systemic DLBCL61–64, whereas gains or amplifications along with overexpression of MYC and BCL2 proteins may also occur62–64. At a variance with these genes, translocations that affect BCL6 (chromosome band 3q27.3) are common in PCNSL61, 65. Moreover, ETV6 (encoding a ETS transcription factor) is inactivated in PCNSL, although its pathogenetic role is unclear39, 66, 67.

Other genetic alterations in PCNSL include recurrent amplifications involving 18q21.23, 19p13.13, 1q32.1, and 11q23.332 and recurrent deletions that involve 6p21, 6q21, 6q27, 9p21.3, 6p 25.3, 22q11.22, and 14q32.3332.

PCNSL cells can evade the immune system, mostly caused by the loss of expression of MHC class I68. This loss could be due to mutations in HLA-A, HLA-B and HLA-C32, DNA losses (6p21.32, 6q21, 8q12–12.2, 9p21.3, 3p14.2, 4q35.2, 10q23.21, and 12p13.2), or uniparental disomy69. Another cause could be somatic mutations, deletions or rearrangements of B2M, CD58, and CIITA, which encode proteins involved in immune evasion34, 39, 51, 70–72. Chromosomal translocations affecting the CD274 (encoding PDL1) locus and, much rarer, genomic amplifications of CD274 and PDCD1LG2 (encoding PDL2) have been often reported39, 55, 61; however, other studies have not found upregulation of PDL155, therefore, the role of these molecules in PCNSL is incompletely defined. In addition, upregulation of miR-17–5p, miR-155, miR-21, and miR-196b has also been found in PCNSL73–77, but the role of these micro RNAs is still under investigation.

A study using a multi-omics approach to evaluate a large series of PCNSL recognized 4 clusters (CS) of this disease32. A hypermethylated, ‘immune-cold’ profile is shared by CS1 and CS2, which differ in clinical behavior and by the presence of high activity of polycomb repressive complex 2 and loss of CDKN2A, leading to enhanced proliferative activity, in CS1. Another cluster, CS4, exhibits a ‘immune-hot’ profile, mutations enhancing JAK-STAT and NF-κb activity, and is associated with favourable outcome. CS3 is more heterogeneous by immune perspective, presenting features of both germinal-center and mature B cells, enriched with H1–4 mutations, associated with meningeal infiltration, and displays the worst outcome32. The identification of these clusters of disease could have therapeutic implications: CS1 could benefit from cyclin D-CDK4,6 and PI3K inhibitors, CS2 could be targeted with lenalidomide or other demethylating agents, CS3 could be treated with EZH2 inhibitors, and CS4 could respond to inhibitors of immune checkpoint and JAK132.

Microenvironment

The pathophysiological mechanisms of PCNSL in immunocompetent patients are incompletely understood. One reason for this is a lack of effective animal models that could be used to better investigate mechanisms of disease. The origin of these cells remains unclear; whether these tumors arise from local transformation of a peripheral B cell which migrates to the CNS or, less likely, whether they arise from a recruited B cell to the CNS during an immune reaction (such as infection) then undergoes neoplastic transformation requires further study. However, this latter proposed mechanism remains speculative given the lack of any supportive study in the literature.

Immunoglobulins expressed by neoplastic PCNSL cells bind to self-proteins expressed in the CNS, which drives chronic BCR signalling. These self-proteins are GRINL1A, ADAP2, BAIAP229, N-hyperglycosylated SAMD14, and neurabin-I31.

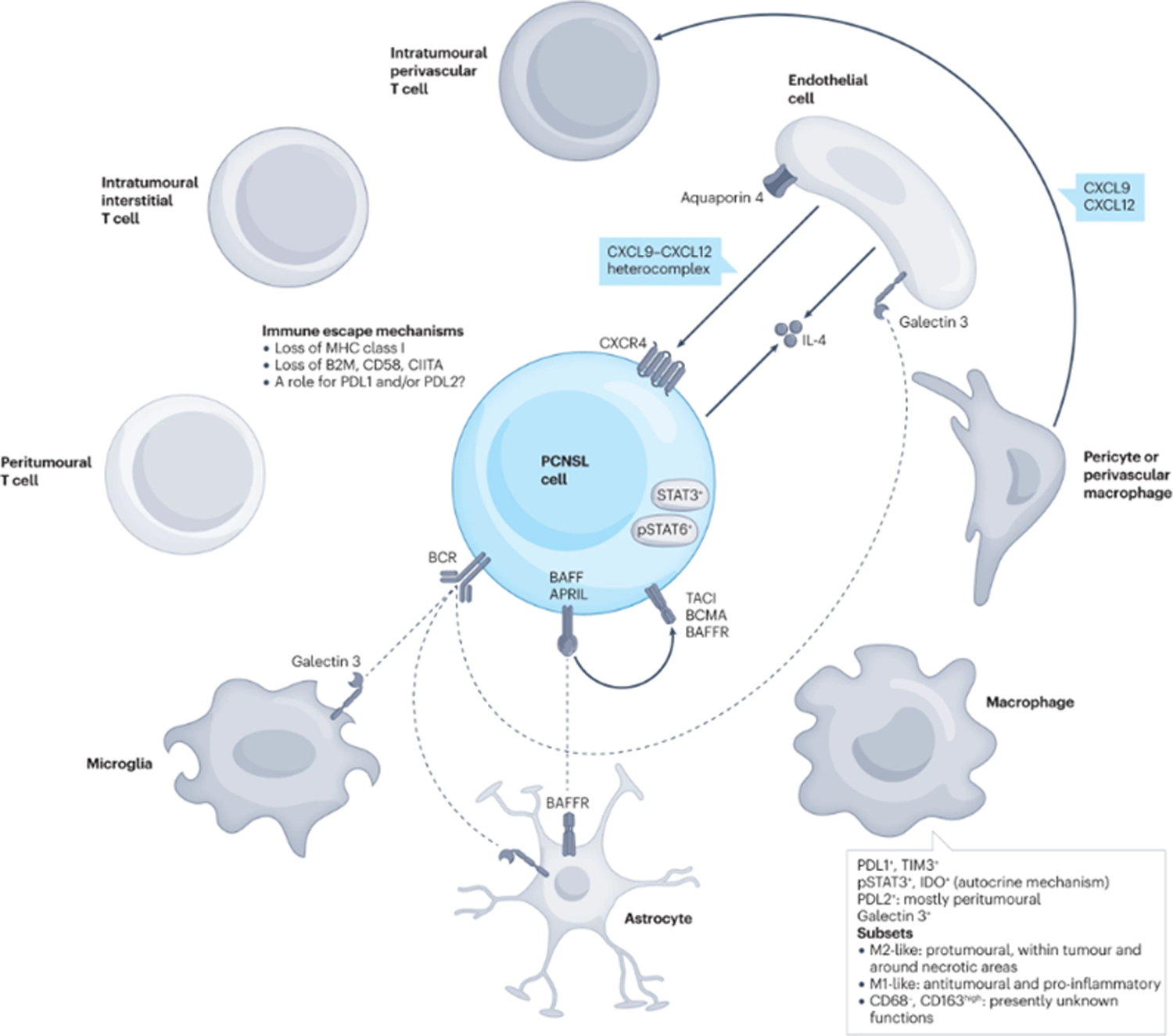

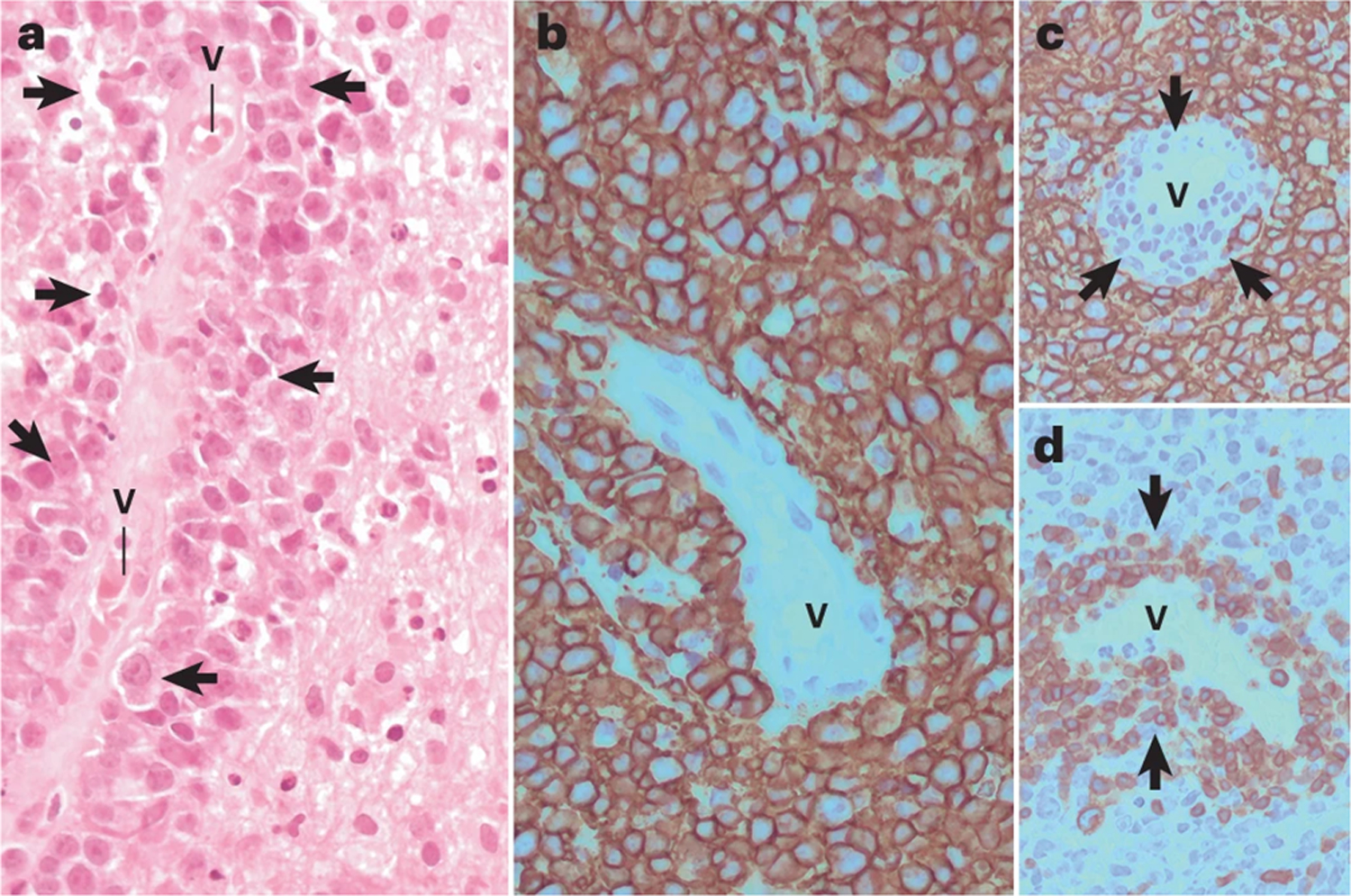

PCNSL are unique as they have a propensity to grow around blood vessels (Figure 1A), although dense, diffuse or purely interstitial growth patterns can also occur. More than 30% of patients have the classical interstitial distribution and a perivascular rim of small reactive T cells (known as reactive perivascular T cell infiltrate, RPVI) (Figure 1 B & C). RPVI can occur alone or interposed between blood vessel wall and perivascular PCNSL cells78. This interstitial distribution of T cells is not random; CD4+ T cells are mostly found around lymphomatous areas whereas CD8+ cells predominate within the tumor78. Unlike that published for systemic DLBCL involving the CNS, CD8+ T cells present in PCNSL express selectively the T cell exhaustion marker TIM-3, whereas do not differentially express similar molecules, like LAG-3, or activation markers, including OX40 and CD6939. CD4+ follicular T helper cells and FOXP3+ regulatory T cells are present, to a much lesser extent than CD8+ T cells, whereas CD56+ T cells are rare39, 55, 79, 80.

Figure 1: PCNSL histopathology.

A) Large lymphoid cells (blue arrowheads) may grow in perivascular space, forming perivascular cuffing. B) CD20 positive large B-cell here display a diffuse growth pattern. In addition to the classical interstitial distribution of reactive T cells, PCNSL exhibit, in one third of cases, a perivascular rim of small reactiveT lymphocytes (so called ‘reactive perivascular T cell infiltrate’, RPVI) is recognized (red arrows). RPVI may occur alone or interposed between blood vessel wall and perivascular lymphomatous cells and does not stain with anti-CD20 (Figure C, black arrows), whereas it is identified by anti-CD3 stain (Figure D, black arrows). V= vascular lumen.

The mechanisms underlying the localisation of neoplastic lymphocytes and RPVI in PCNSL have only been partially elucidated (Figures 2 and 3). For RPVI, CXCL-9 – which is produced by pericytes and perivascular macrophages/microglia - recruits CXCR-3+/CD8+ T cells to perivascular areas81. The tumor blood vessels also have an active role, as endothelial cell-derived CXCL-12 forms heterocomplexes with CXCL9 on the endothelial luminal surface, which can recruit CXCR-4+ neoplastic B cells around vessels to form the classical histopathological angiocentric pattern of PCNSL81.

Figure 2: Biological and molecular propertiers of microenvironment in PCNSL.

The interaction of tumor cells in PCNSL with microenviroment involves several cells (mainly T-cells, endothelial cells, macrophages, microglia, and astrocytes, as well as different receptors, cytokines and chemokines

Monocytes/macrophages also have a role in PCNSL pathogenesis although many aspects of their involvement remain obscure. Macrophages are abundant in PCNSL. Three distinct subsets of macrophages have been identified in PCNSL: M1-like, CD68+ CD163low population, which have anti-tumoral properties; M2-like CD68+ CD163high macrophages, which have pro-tumoral effects; and a CD68− CD163-high subgroup, whose significance is unknown79. M2-like macrophages are more abundant within the central portion of the lymphoma, in which they accumulate around necrotic areas of coagulative tumor necrosis79. M2 macrophages express molecules involved in immune checkpoint mechanisms (PD-L1 and TIM-3)28, 79, 82, 83, which may have important immunological therapeutic implications, although the prognostic role of PD-L1+ macrophages is debated84–86. The subsets of macrophages/microglia of PCNSL may represent different functional states; indeed, targeting these cells with ibrutinib and selinexor (a selective blocker of Exportin 1) promotes their skewing toward a pro-inflammatory M1-like phenotype and modulates PD1 and SIRPa expression on M2-like macrophages87. In contrast to other hematological malignancies, like Hodgkin lymphoma, where abundant tumor-infiltrating CD163+ histiocytes are considered a predictor of worse prognosis88, in a small retrospective PCNSL series79, the absolute amount of CD163+ M2 tumor associated macrophages had not prognostic value, whereas a low M1/M2 ratio was associated with poor outcome.

Other molecules expressed by macrophages/microglia include members of the STAT family, which are thought to be involved in PCNSL pathogenesis through two key interactions. First, STAT-3 activates the expression of PD-L1 and IDO89 via an autocrine mechanism. This property is important and could be exploited as a therapeutic strategy, as STAT3 inhibitors abrogate PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression in TAM89, 90. PD-L2+ TAMs preferentially accumulate in the peritumoral portion of PCNSL, and provides part of the rationale for the study of BTK inhibitors in patients with PCNSL18, 87. In this regard, BTK inhibitors can directly attack the survival of malignant B-cells and also increase antitumor immune reaction, since BTK protein is not only involved in malignant B-cell survival but is also required for the tumor-promoting effect of macrophages. In fact, the combined use of BTK and XPO1 inhibitors was effective in harnessing the innate immune response mediated by TAMs in allograft mouse models of PCNSL. This strategy was able to shift the innate immune response towards a more inflammatory phenotype, specifically defined by downregulation of PD-1 and SIRPα in M2 macrophages and increased proportion of M1 macrophages as well as modulation of additional M1 and M2-like properties consistent with loss of pro-tumoral M2 characteristics18, 87. Moreover, the density of CD163+ macrophages/microglia correlates with increased expression of STAT3 in neoplastic B cells, suggesting that TAM may provide pro-survival and progression signals to PCNSL82, 84.

The role of the endothelium in PCNSL pathogenesis has been addressed in a few small studies. Lymphomatous and endothelial cells are a source of IL-4, and IL-4 expression occurs selectively within PCNSL tumors91. Endothelial cells express aquaporin-4, which regulates permeability of the blood brain barrier,92 and galectin-3, which is also expressed by microglia/macrophages and astrocytes, and is recognized by the BCR of neoplastic B cells29. In addition, high expression of pSTAT6 in PCNSL tumors is associated with worse outcome54.

Other relevant microenvironment components include astrocytes (which express the BAFF-receptor)93, chemokines and interleukins94, 95.

Diagnosis, screening and prevention

Clinical presentation

Accurate diagnosis of PCNSL requires a high degree of suspicion and prompt investigation. Symptoms and manifestations of PCNSL vary depending on the involved regions of the nervous system. Commonly observed symptoms of systemic lymphoma (that is, fever of unknown origin, night sweats and weight loss) are rare in PCNSL96.

Intraparenchymal PCNSL.

The most common location of PCNSL is the brain parenchyma (reported in 92% of patients97), of which the most common clinical presentation is focal neurological deficit followed by altered mental status (Box 1). Focal neurological symptoms at presentation usually prompt brain imaging leading to rapid diagnosis. However, psychiatric or nonspecific presentations often lead to delayed diagnosis (mean 80 days from symptom onset to diagnosis)97,98.

In a study of brain magnetic resonance image (MRI) findings in 100 patients with PCNSL, solitary brain lesions were observed in 65% of patients and multiple lesions were observed in 35% of patients99. Most brain lesions in PCNSL are supratentorial (and are commonly located in the frontal lobe) rather than infratentorial, with a 3:1 ratio100. The location of brain lesions is often associated with specific clinical manifestations; for example, personality changes and motor deficits are more commonly associated with frontal lobe lesions, aphasia is associated with lesions in the parietal or temporal lobes, visual deficits with lesions in the occipital lobe and ataxia with cerebellar lesions100. Parenchymal lesions are more commonly associated with high protein concentrations in the CSF, which is currently explained by extensive damage of blood-brain barrier101.

Leptomeningeal lymphoma.

Leptomeningeal or CSF dissemination of PCNSL occurs in 0–50% of patients, with most studies reporting positive cytology or flow cytometry in ~15% of patients102, with no effect on overall survival demonstrated in a prospective study102, 103. Isolated CSF lymphoma, or primary leptomeningeal leptomeningeal is extremely rare. Most patients with leptomeningeal lymphoma (68%) present with multifocal symptoms (Box 1). CSF diagnosis of leptomeningeal lymphoma (Box 2) should prompt contrast-enhanced brain and spinal MRI104. CSF analysis in patients with leptomeningeal lymphoma typically shows normal glucose concentration, elevated protein levels (median 235 mg/dL), and increased white blood cell count.

Box 2. Clinical features of PCNSL.

Intracranial PCNSL

|

The percentages reflect the proportion of patients with these manifestations.

Lymphoma into the eyes.

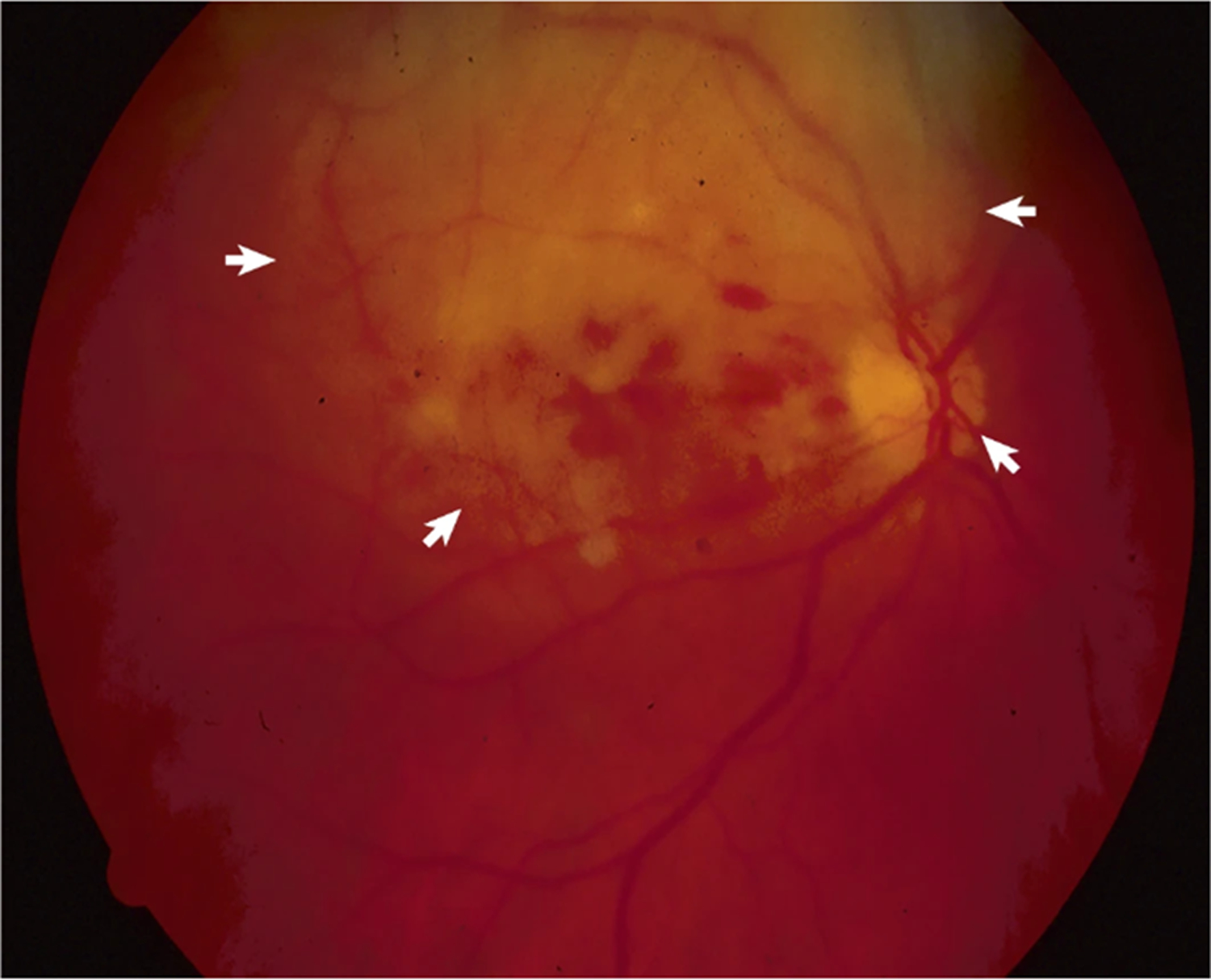

DLBCL preferentially involves structures of the posterior segment of the eye, particularly the vitreous and retina105, whereas the anterior segment of the eye is rarely affected106. Accordingly, this presentation is called vitreoretinal lymphoma (VRL), which occurs in ~15–25% of patients with PCNSL107, 108. VRL (Box 1) is usually bilateral and is sometimes diagnosed as the initial and exclusive site of disease109. In rare cases, intraocular structures can be exclusive site of lymphoma in a condition known as primary vitreoretinal lymphoma (PVRL), which can be followed by brain or CNS involvement (Figure 4). PVRL can be unilateral or bilateral and is slightly more common in women than in men107, 108,110, 111.

Figure 4: Intraocular infiltration.

Fundoscopy shows tumoral infiltration of the retina and retinal hemorrages (arrows) in a patient with primary cerebral lymphoma.

Symptoms of VRL are nonspecific (Box 1), and often patients are misdiagnosed with steroid-resistant uveitis (inflammation of the uvea)112. Of note, 33% of patients with PCNSL who have concomitant vitreoretinal infiltration do not have ocular symptoms107, 108, 113. VRL usually occurs concomitantly to lesions of the brain parenchyma, which should be assessed by contrast-enhanced brain MRI. In patients with VRL suspicion and concurrent brain lesions, diagnosis should be made on tumor tissue collected by brain biopsy to achieve a more accurate diagnosis and lymphoma characterization, whereas histopathological confirmation of intraocular infiltration is not advised98, 114; CSF cytology is positive in 35% of patients with concurrent brain and VRL108. In patients without a concurrent brain lesion (i.e., PVRL), vitrectomy is the gold standard to collect diagnostic material (see below), whereas detection of tumor cells in CSF samples is useful to confirm a difficult diagnosis108. CSF parameters are usually normal in patients with PVRL111.

In a prospective study115, the presence of concurrent VRL in patients with PCNSL was associated with an inferior prognosis. Importantly, patients with PVRL have a high risk of progression to other CNS sites, particularly the brain109, with meningeal dissemination reported in 15% of patients with PVRL111. In fact, ocular symptoms preced other CNS involvement in 31% of PCNSL patients116, and up to 69% of VRL patients will develop lymphomatous lesions in other regions of the CNS over the course of disease110, 114. Additionally, vitreoretinal involvement may be the presenting sign of relapse in PCNSL111.

Of note, retro-orbital lymphoma, which can present with proptosis (protrusion of the eyeball), is outside the CNS. Accordingly, this disorder is not considered PCNSL or PVRL and patients with suspected retro-orbital lymphoma should undergo prompt investigation for systemic lymphoma117.

Spinal cord lymphoma.

Primary spinal cord lymphoma is rare, comprising <1% of all PCNSL (Supplemental Figure 1 and Box 1). Patients with systemic lymphoma can develop leptomeningeal dissemination or epidural lesions, which can result in spinal cord or cauda equina compression; intramedullary spinal lymphoma may also rarely occur118. CSF cytology is non-diagnostic in most patients. Although spinal cord biopsy carries a high risk of important sequela (a.e., permanent motor and sensitive route damage), it may be necessary to establish diagnosis in rare cases of single intramedullary lesions considering that the diagnostic role of biomarkers remains to be defined in this rare form of PCNSL. In multifocal disease with concomitant involvement of brain and spinal cord parenchymas, biopsy of brain lesions should be preferred to spinal cord biopsy.

Imaging

Gadolinium-enhanced MRI is the standard imaging procedure to generate PCNSL suspicion, to demarcate CNS tumor extension, to define therapeutic response, to monitor PCNSL during follow-up, and to confirm tumor recurrence in affected patients. Consensus recommendations for the use of MRI and PET for diagnosis and monitoring of PCNSL are available from the International PCNSL Collaborative Group (IPCG)7. Recommendations for conventional MRI align with prior consensus recommendations for glioma119 and intracranial metastases120 and focus on standardization of image acquisition relative to timing and dosage of gadolinium-based contrast agent (GBCA) administration (Figure 5). These recommendations also emphasize the importance of volumetric acquisitions, either with gradient-echo or (ideally) spin-echo techniques, to quantify lesion size7.

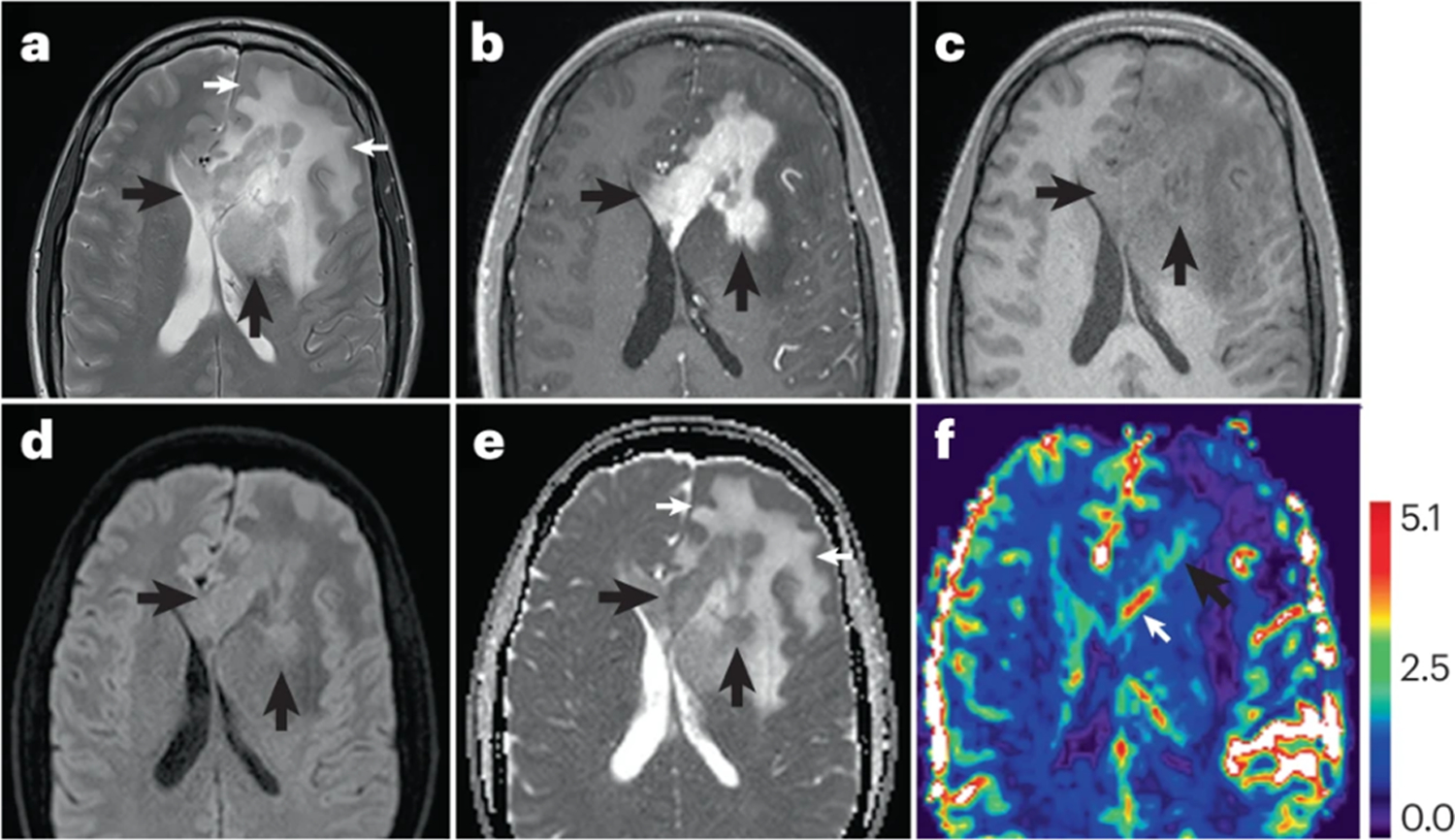

Figure 5: MRI findings in a patient with Primary CNS Lymphoma.

T2-Weighted MRI shows a relatively T2W hypointense mass (panel A, black arrows) centered along the midline within the corpus callosum, extending into the left basal ganglia, which is distinct from the hyperintensity of the extensive surrounding non-tumoral vasogenic edema (panel A, white arrows). The mass demonstrates homogeneous diffuse contrast enhancement on post-contrast T1W imaging (panel B, yellow arrows), which is confirmed on T1W pre-contrast imaging (panel C, arrows). Moreover, the mass shows characteristic restricted diffusion seen as bright signal on diffusion trace imaging (panel D, arrows) and confirmed as hypointensity on maps of Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) (panel E, black arrows). Restricted diffusion has been attributed to paucity of extracellular fluid relative to highly cellular content of these tumors. Of note, the ADC values of non-tumoral vasogenic edema are seen as hyperintense regions on ADC maps, presumably due to greater proportion of extracellullar fluid relative to tissue cellularity (panel E, white arrows). On Dynamic Susceptibility Contrast MRI maps of relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV), the mass shows areas of mild to moderately (> 2.0) elevated rCBV (panel F, black arrow), with a prominent enhancing subependymal vein (arrow).

Advanced MRI techniques, such as Diffusion Weighted Imaging (DWI) measurements of Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC),7, 121, Dynamic Susceptibility Contrast (DSC) MRI, and relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV)122, 123, may also be useful for the diagnosis of PCNSL124. Preliminary studies have also shown a potential prognostic value of both ADC125–127 and rCBV127–129, although multi-center clinical trials in patients with PCNSL are required to validate the clinical use of these techniques. These positive results have motivated efforts to promote consensus protocols for both DWI7 and DSC-MRI7, 121. Other advanced imaging methods also show promise for diagnosis of PCNSL, including brain PET and Dynamic Contrast Enhanced (DCE)-MRI7,130, 131.

Diagnosis, pathology and molecular biology

The gold standard for diagnosis of PCNSL in the brain parenchyma is stereotactic biopsy. Rare cases of primary DLBCL of the meninges, that are usually considered forms of PCNSL, are diagnosed from samples collected by surgical resection. Histopathological examination usually shows mass forming large lymphocytes arranged in solid sheets with a characteristic perivascular, angiocentric pattern at the edge of the lesion (Figure 1). Neoplastic lymphocytes are large cells containing a moderate amount of cytoplasm, round to oval vesicular (i.e. containing small fluid-filled sacs) nuclei, vesicular chromatin, and two-three small nucleoli often located adjacent to the nuclear membrane (centroblastic-like morphology), accompanied by a variable number of elements with immunoblastic-like features, that is large, rounded cells possessing moderate amounts of amphiphilic or pyrinophilic cytoplasm and characteristic, large vesicular rounded nuclei containing conspicuous nucleoli. These cells are also accompanied by a small although variable number of small reactive T cells - which can also arrange as RPVI78 - macrophages, activated microglia, reactive astrocytes, and reactive, non-neoplastic B cells. PCNSL are immunoreactive for the B cell markers CD20, CD79a and PAX5. Immunostaining for at least one of these markers (most frequently CD20) is used in routine diagnostic work-up. The ‘late germinal center immunophenotype’, including positive immunostaining for BCL6 and IRF4 (also known as MUM1), is present in 60–80% of cases132. Proliferative activity is usually very high133. Immunoreactivity for CD10 is usually found in <10% of patients133. Moreover, IgM and IgD are almost always exclusively expressed by PCNSL cells, reflecting the absence of immunoglobulin class switch in these lymphomas134.

CSF samples should be collected from all patients with suspected or confirmed PCNSL for diagnosis5 and staging (see Staging and Risk Assessment, below). However, lumbar puncture is not always safe, particularly in patients with concurrent brain masses and/or extensive perilesional oedema, which can result in intracranial hypertension and increased risk of herniation; consultation with an expert in neuro-oncology and neurosurgery may be warranted in these patients. CSF examinations include physic-chemical parameters (aspect, colour, glucose concentration, protein concentration, nuclear cells count), conventional cytology, and flow cytometry. Typically, CSF from patients with PCNSL has high leucocyte counts, normal glucose concentration, and increased protein concentration, the latter reflecting blood-brain barrier disruption. Flow cytometry allows the detection of B-cell clonality, increasing diagnostic sensitivity135. Diagnostic sensitivity and specificity could be further improved by assessment of molecular markers such as the MYD88 L265P mutation and quantification of IL-10 levels in CSF94. These biomarkers are extremely helpful to achieve PCNSL diagnosis in patients with tumor lesions that are not suitable for biopsy (e.g., brainstem) or low cellularity/poor-quality of CSF samples94.

Vitrectomy (removal of vitreous humor) is the gold standard for diagnosis of PVRL. An expert ophthalmologist should confirm intraocular involvement and exclude differential diagnoses136 both in patients with PVRL and PCNSL of the brain parenchyma and VRL. Chorioretinal biopsy is much more informative than vitrectomy but is carried out in a minority of patients because associated with a higher risk of visual sequelae. Of note, vitrectomy and chorioretinal biopsy are not mandatory to confirm vitroretinal infiltration if diagnosis of PCNSL has been carried out on brain biopsy. The sensitivity and specificity of vitrectomy could be improved by evaluation of molecular markers such as MYD88 L265P mutation and IL-10 and IL-6 levels in vitreous humor or aqueous humor samples137, 138. The molecular detection of MYD88 L265P mutations has been carried out in aqueous humor samples138; given the virtual absence of cells in these samples this approach seems very promising as it is less invasive than collection of vitreous humor and is potentially useful for response assessment and staging.

Staging and risk assessment

Patients with presumptive or histologically confirmed diagnosis of PCNSL should undergo assessments to determine the extent of disease within the CNS and to exclude systemic lymphoma139.

A gadolinium-enhanced brain MRI scan is the most sensitive radiographic study to evaluate the extent of PCNSL in the brain, intracranial meninges and cranial nerves. Owing to the possibility of changes related to biopsy and disease aggressiveness, brain MRI should be performed again after the surgical biopsy (ideally within 14 days before treatment initiation) as a baseline assessment7. Contrast-enhanced MRI of the spinal cord should be carried out in patients with symptoms of spinal involvement or those with CSF positivity.

CSF sampling, with evaluation of cell count, protein and glucose levels, and cytology, is mandatory in all patients with confirmed PCNSL to detect leptomeningeal disease, which is often asymptomatic. Diagnostic sensitivity is improved by coupling flow cytometry to conventional cytology examination140.

Visual complaints are reported by 10%−20% of PCNSL patients as sign of ocular involvement105, 116. As asymptomatic ocular involvement is frequent, every patient with PCNSL should be assessed by an expert ophthalmologist via slit-lamp examination and retinal angiography/tomography113. In patients with PCNSL diagnosed on brain biopsy and suspected vitreoretinal involvement, confirmation on vitrectomy sample is superfluous. Assessment of IL-6, IL-10 and MYD88 L265P on vitreous and aqueous humours can confirm VRL during staging137, 138.

The detection of lymphoma outside the CNS is important as both prognosis and treatment differ between primary and secondary CNS lymphomas141. Conventional staging with [18F]2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D glucose-PET (18FDG-PET) is superior to contrast enhanced CT scan, and in one study identified occult systemic lymphoma in 4–12% of patients with presumptive diagnosis of PCNSL142. Moreover, histopathological confirmation of high-uptake lesions outside the CNS is suggested if clinically feasible. Contrast-enhanced neck, chest, abdomen and pelvic CT scan should be carried out only if 18FDG-PET-scan is not available. Testicular ultrasonography, in addition to bone marrow biopsy and aspiration should also be carried out in those with PET-scan positivity or when 18FDG-PET-scan is not available. Moreover, bone marrow biopsy is indicated in those with cytopenias or those of borderline suitability for autologous stem cell transplantation to assess bone marrow reserve.

Before starting treatment, a full medical (including concomitant medication and corticosteroid use) and neurological examination should be performed as well as a baseline assessment of cardiac (echocardiography and electrocardiogram), liver and renal functions. Pulmonary assessment (thorax CT scan and pulmonary function test with spirometry and diffuse capability of CO2) should be performed only for patients with known lung disease. Blood tests (complete blood count, liver and renal function index, serology for HIV and hepatitis B and C viruses and pregnancy test) are mandatory as results of these tests can affect treatment. People with hepatitis virus infections should be carefully assessed by liver disease specialists to address indications for antiviral prophylaxis or treatment.

Two prognostic scoring systems are used to predict outcomes and stratify patients in clinical trials: the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELSG) score143 and the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) prognostic score144. The IELSG score includes age, PS, LDH serum level, CSF protein concentration, and involvement of deep areas of the CNS, whereas MSKCC prognostic score includes age and PS.

Management

Several chemoimmunotherapy combinations, and different consolidation and maintenance strategies are available for PCNSL. Prospective trials and retrospective studies have included varied study populations, some of which defined with imprecisely used criteria (particularly with regards to age and PS).

General recommendations to improve patient management are referring patients with suspected or confirmed PCNSL to centers of excellence to avoid diagnostic delay and initiate appropriate treatment. Suitable patients should also receive information on prospective clinical trials and, if trials are not available, should be treated in accordance with findings from multicenter, randomized trials. In the latter case, the eligibility criteria and study population included in the trial, and the toxicity profile of the evaluated treatments, should be carefully reviewed and considered when selecting treatments for individual patients.

PCNSL is potentially curable although minimizing the toxicities of treatment is challenging. Age and baseline PS are the main determinants of outcome, and both influence therapeutic decision making. Different upper age limits have been used in prospective trials and ‘fitness’ is often crudely defined. Age should not be exclusively used when to choosing the optimal treatment, as patients in their eighth decade of life may tolerate rationalized intensive regimens. Accordingly, other important factors such as organ function, comorbidities, frailty, risk of neurotoxicity, and patients’ priorities, should be considered when deciding treatment choice. PS is another important prognostic factor5, 139 and intensity-determining issue. In particular, patients with PCNSL and ECOG-PS >2 can experience important complications during intensified treatments that are mostly related to prolonged lodging and use of steroids, namely, severe infections, deep venous thrombosis, thromboembolism, diabetes mellitus, and other metabolic disorders.

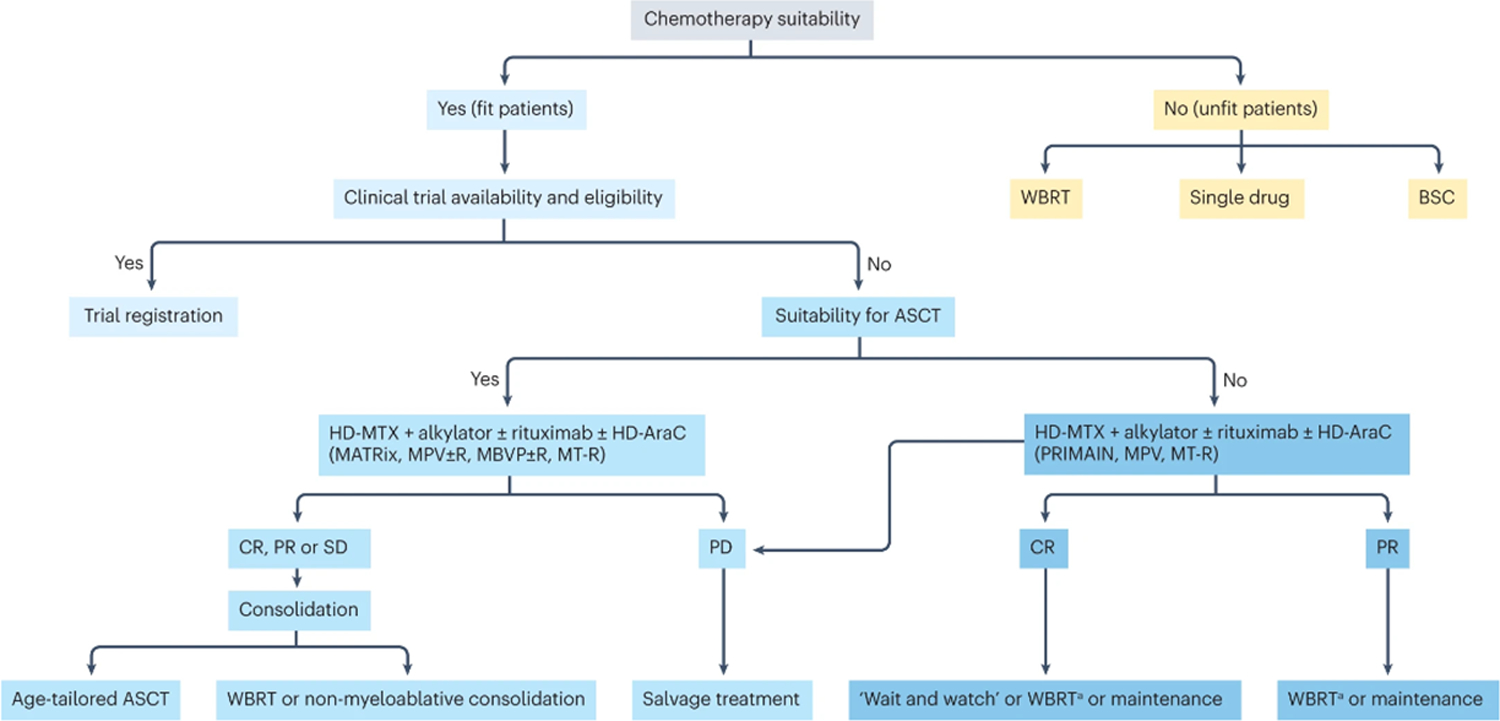

According to the use of these evaluations, patients with newly-diagnosed PCNSL can be categorized as: fit patients suitable for intensified treatments (particularly high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation (HDC-ASCT)); fit patients unsuitable for HDC-ASCT; and unfit patients who are not eligible for chemotherapy (Figure 6). Importantly, assessment of fitness for consolidation strategies, such as HDC-ASCT, should be dynamic and reviewed throughout the treatment course in specialist PCNSL centres. Moreover, the potential benefits and risks of treatments should always be discussed with patients.

Figure 6: Therapeutic flow-chart for patients with newly-diagnosed PCNSL.

A) Suitability for chemotherapy and intensified treatment (ASCT) is a complex decision that is based on several factors, including age, performance status, comorbidity, organ function, frailty, and risk of neurotoxicity among others. The clinical experience of the treating physician and patient’s wishes have important roles on treatment choice. B) Consolidation with reduced-dose whole-brain radiotherapy is an option in elderly patients with disease responsive to induction therapy-

ASCT= myeloablative chemotherapy supported by autologous stem-cell transplantation; BSC= best supportive care; CR= complete remission; HD-ARAC= high-dose cytarabine; HD-MTX= high-dose methotrexate; PD= progressive disease; PR= partial response; SD= stable disease; WBRT= whole-brain radiotherapy.

Fit patients

Intensive induction with multi-agent chemoimmunotherapy regimens containing high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX) followed by consolidation strategies (HDC-ASCT, radiotherapy and/or non-myeloablative chemotherapy) has the highest efficacy for the treatment of PCNSL in fit patients. Consolidation strategies are used to eliminate residual disease, maximize duration of response and improve quality of life. HDC-ASCT is increasingly used in this population145–147, and initial results of two international randomized trials seem to confirm its superiory compared with consolidation with non-myeloablative chemotherapy148, 149. WBRT with conventional doses is used less frequently than in previous years owing to mounting evidence of associated neurotoxicity, reduced doses and targeted radiotherapy approaches are being explored.

Induction approaches.

HD-MTX is the most important component of PCNSL induction regimens. Combining cytarabine (AraC) and HD-MTX is beneficial and led to improved response rates, progression free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS) in one international randomized trial150; as expected, grade 3–4 hematological toxicity was higher in the AraC group151. Other studies have combined HD-MTX with other drugs (Supplementary Table 1), namely, MTX/AraC; MTX/AraC plus rituximab (R-MTX/AraC); HD-MTX/HD-AraC plus rituximab and thiotepa (MATRix)152,146, 152,.153.154,155; HD-MTX plus rituximab and temozolomide (MT-R protocol)156; HD-MTX plus rituximab, procarbazine and vincristine with intrathecal MTX for patients with CSF involvement of lymphoma (R-MPV regimen)157; and HD-MTX plus teniposide, carmustine and prednisolone (MBVP protocol)147, 158. However, these regiments have not been compared in head-to-head studies, so superiority of any of these combinations has not been demonstrated. MATRix is the only exception, as the randomized trial called IELSG32 has demonstrated that the addition of rituximab and thiotepa is associated with significantly improved outcome in comparison with HD-MTX/HD-ARAC and HD-MTX/HD-AraC plus rituximab combinations.146 Nevertheless, regional preferences have influenced the selection of specific induction regimens, often based on institutional experience.

The use of rituximab in PCNSL is debated. The phase III HOVON 105/ALLG NHL 24 trial compared the MBVP protocol with MBVP plus rituximab158, followed by consolidation with HD-AraC in all patients and low-dose WBRT in patients <60 years. However, this trial found no advantage in terms of event-free survival (EFS) with rituximab addition, although there was a non-significant trend to improved PFS. An unplanned subgroup analysis showed that only patients <60 years had a significant benefit from rituximab. By contrast, the addition of rituximab to HD-MTX/HD-AraC in the IELSG32 trial was associated with a significant improvement in 5-year OS (40% compared with 28% in those who received only HD-MTX/HD-AraC)146. Benefit on survival with the addition of rituximab is independent of IELSG risk score and other prognostic variables146. A meta-analysis of the IELSG32 and HOVON 105/ALLG NHL 24 trials confirmed a PFS benefit with the addition of rituximab159 and many induction protocols continue to incorporate this agent as added toxicity is minimal.

As there are some pharmacokinetic limitations with reaching therapeutic concentrations in CSF and intraocular humors of drugs delivered intravenously, some authorities propose including intrathecal and/or intravitreal chemotherapy during induction treatment160, 161. However, evidence in support of these approaches is only from non-randomised prospective and retrospective studies, with conflicting results and sometimes with substantial toxicity162–164. Thus, intrathecal and intravitreal chemotherapies cannot be routinely recommended if appropriate systemic chemotherapy can be applied, but can be considered for patients with persistent, isolated, meningeal or VRL with insufficient response to HD-MTX-based protocols. Fit patients with PVRL should be treated with HD-MTX-based induction chemotherapy, using the same combinations proposed for other patients with PCNSL. Intravitreal MTX injections can be added if a rapid regression of intraocular disease is needed. PVRL patients with a CR or PR to HD-MTX-based induction can be eligible for consolidation with low-dose bilateral ocular irradiation, whereas the risks and benefits of consolidation with ASCT can be discussed with selected patients.

Consolidation: HDC-ASCT.

The rationale for HDC-ACST in PCNSL is the delivery of anticancer drugs that are able to cross the blood-brain-barrier, at sufficiently high doses to achieve valid therapeutic concentrations in the CNS, and overcome drug resistance. Conditioning protocols that are commonly used for treatment of systemic lymphoma (namely, the BEAM regimen comprising carmustine, etoposide, AraC, and melfalan) yielded disappointing results in PCNSL165, 166, whereas thiotepa-containing protocols have demonstrated good efficacy146, 167–170.

In a multicenter phase II trial, 79 patients received induction consisting of HD-MTX plus rituximab followed by HD-AraC plus rituximab plus Thiotepa, followed by ASCT conditioned with carmustine and thiotepa (TT-BCNU)169 and, in 10 patients who did not achieve a complete remission (CR) after HDC-ASCT, WBRT. Five-year PFS was 65% and OS was 79%. Another monoinstitutional prospective study showed similar results: noting a 2-year PFS of 79% and OS of 81% after induction with R-MPV, followed by HDC-ASCT with thiotepa, cyclophosphamide, and busulfan (TBC regimen)170. Moreover, one retrospective study demonstrated superiority of thiotepa-based conditioning owing to improved 3-year PFS (75% compared with 58% with BEAM conditioning)171. In a multivariable regression analysis, patients who received TT-BCNU had a significantly higher relapse risk, lower risk of nonrelapse mortality (NRM), and similar risk of all-cause mortality >6 months after HCT-ASCT compared with patients who received TBC conditioning171. Subgroup analyses demonstrated a higher NRM in patients aged ≥60 years who received TBC compared with those who received TT-BCNU conditioning. Decisions regarding the choice of thiotepa-based conditioning regimen is influenced by the selected induction regimen, the achieved response, the availability of the drug in each country, and patient characteristics171.

Tolerability and efficacy of HDC-ASCT in patients with newly-diagnosed PCNSL has been investigated in two randomized phase II trials. The IELSG32168 and the PRECIS167 demonstrated a similar radiographic response and 2-year PFS with consolidation with either HDC-ASCT and carmustine and thiotepa conditioning (2-year PFS 75%) or WBRT (2-year PFS 76%). Another analysis demonstrated a 7-year OS of 70% in treated with MATRix and consolidation, with no significant difference between WBRT and ASCT146. Independent prognostic factors were IELSG score, number of lesions, and induction arm. Of note, cognitive function and quality of life were improved in the ASCT arm146, and progressive decline in attention and executive functions were observed in patients treated with WBRT.

By contrast, the PRECIS study demonstrated superior EFS and cognitive function in those undergoing TBC-conditioned ASCT (2-year PFS 87%; 95% CI 77–98%) compared with patients who received WBRT (2-year PFS 63%; 95% CI 49–81%)167. Cognitive impairment was observed after WBRT, whereas cognitive functions were preserved or improved after ASCT. Moreover, an updated analysis with median follow-up of 93.8 months reported higher 8-year relapse-free survival after ASCT (94%) compared with WBRT (48%)167. Of note, severe neurotoxicity was observed in almost 50% of long-term survivors in the WBRT arm whereas minimal or no long-term neurotoxicity was observed after ASCT.

Collectively, these results demonstrate very good long-term outcomes in younger and fit patients with HCD-ASCT, and that WBRT can be avoided in a large proportion of these patients. However, these results come from prospective trials and, therefore, they cannot be extended to the overall population of patients with PCNSL.

Consolidation: radiotherapy.

Consolidating WBRT after HD-MTX-containing induction was considered standard of care to reduce risk of relapse172. However, more recently, ASCT is preferred in fit patients after HD-MTX-based chemotherapy. Nevertheless, WBRT remains an alternative approach for consolidation in fit patients with insufficient autologous stem cells harvest, those with significant toxicity after induction chemotherapy or those who refuse HDC-ASCT. The use of WBRT as a consolidation option for PCNSL has been addressed in two randomized trials. The G-PCNSL-SG-1 trial suggested that WBRT is associated with improved PFS, with no benefit in OS173. However, this non-inferiority trial did not achieve the primary endpoint and results of this study may be influenced by some methodological flaws174. Of note, consolidation WBRT is associated with delayed neurotoxicity, memory deterioration, personality change, gait disturbance, and urinary incontinence, particularly in patients >60 years167,168,175, 176. Accordingly, discussion with clinical oncology specialists regarding potential benefits and toxicity is paramount before commencing treatment.

To reduce neurotoxicity associated with WBRT, the randomized RTOG1114 trial evaluated low-dose WBRT and found an improvement in PFS with WBRT after R-MPV-A compared with R-MPV-A alone177. An intention-to-treat analysis performed after a median follow-up of 55 months found a 2-year PFS of 78% for the chemoradiotherapy group and 54% for the chemotherapy alone group177. A longer follow-up is needed to detect any difference in neurotoxicity between treatment arms.

Consolidation: non-myeloablative chemotherapy.

Non-myeloablative chemotherapy may be a valid alternative to ASCT or WBRT, and is being addressed in two randomized trials: the Alliance/CALGB51101 and MATRix/IELSG43. The Alliance trial incorporated consolidation with AraC and infusional etoposide (EA; non-myeloablative regimen) after induction with the MT-R regimen and reported a 2-year PFS of 57% and an estimated 4-year OS of 65%, with grade-4 neutropenia and thrombocytopenia in 50% of patients178. The Alliance/CALGB 51101 randomized trial demonstrated poorer PFS in patients treated with MT-R plus one course of HD-AraC and EA consolidation (2-year: 51%) compared with patients treated with MT-R plus one course of HD-AraC and HDC-ASCT with carmustine/thiotepa consolidation148(73%; p= 0.02), with similar toxicity profiles148. However, during induction, significantly more patients in the EA arm experienced progressive disease or death compared with those who received HDC-ASCT with carmustine/thiotepa. In a pre-planned secondary analysis, HDC-ASCT consolidation was associated with a non-significant trend toward improved PFS and OS compared with EA consolidation. Initial results from an international randomized phase III trial suggested significantly improved PFS and OS with HSC-ASCT with carmustine/thiotepa conditioning compared with patients receiving consolidation using rituximab, dexamethasone, etoposide, and carboplatin (R-DeVIC protocol)179,149. Indeed, 3-year PFS was 79% after HDC-ASCT and 53% after R-DeVIC (HR 0.42; p=0.0003), with 3-year OS of 86% and 71%, respectively (HR 0.47; p=0.01). The evaluation of neurocognitive functions showed no difference between arms149.

Future research should aim to optimize induction treatments to reduce toxicity and deliver most patients into effective consolidation strategies. Furthermore, the role of targeted agents should be explored in prospective trials.

Elderly or unfit patients

Elderly patients with PCNSL represent a vulnerable population with generally poor outcomes and higher susceptibility to treatment-related toxicities180. Importantly, best supportive care should be preferred in selected, frail patients when symptomatic and PS benefit is hardly achievable (Figure 6). An age of 60–65 years old has generally been considered the threshold for defining an elderly population in most studies; as the median age at diagnosis of PCNSL in the USA, Europe and Asia is 67 years, around half of all newly diagnosed PCNSL cases occur in the elderly9, 14.

The prognosis of patients with PCNSL >70 years has not substantially improved13, 18. This may be due to the relatively inferior PS of elderly patients, their higher rates of comorbidities, and the use of less aggressive and probably suboptimal treatments in this population. In a prospective cohort of diagnosed elderly patients with PCNSL treated according to published guidelines in France, (>90% received HD-MTX-containing treatment without WBRT), median survival of those aged ≥60 was 15.4 months and 5-year survival was 28%9.

Despite a limited number of prospective studies in the elderly, there is consensus to treat newly-diagnosed elderly patients with PCNSL similarly to younger patients, with MTX combined with other chemotherapies. Dose adjustments of MTX can be made based on estimated renal function; MTX doses ≤3.5 g/m2 are well tolerated in most older patients (including those >80 years)181 who have preserved renal function, when adequate supportive measures, frequent monitoring of serum MTX levels and urinary clearance are carried out182. MTX dose reduction is not necessary in fit elderly patients with normal renal function as dose intensity reductions may be associated with inferior outcomes183.

The CR rates in elderly patients who received HD-MTX range from 17 to 69%, with a median PFS of 6–16 months and a median OS of 14–37 months180. In a meta-analysis that included 783 newly-diagnosed elderly patients with PCNSL improved OS was associated with HD-MTX-based treatment180. Moreover, in a randomized phase 2 study in patients >60 with newly diagnosed PCNSL, 53% achieved CR with HD-MTX, procarbazine, vincristine, and AraC, whereas 38% achieved CR with HD-MTX and temozolomide, although this difference was not statistically significant. Of note, toxicities were similar in the two treatment arms184. Although rituximab is used in several immunochemotherapy combinations, its benefit in elderly patients is debated158.

Consolidation with WBRT is generally not used in elderly PCNSL patients owing to the associated high risk of clinical neurotoxicity and its negative effect on quality of life (see Quality of Life, below)175, 176. Preliminary results of the RTOG1114 trial suggest improved PFS with reduced-dose WBRT as consolidation after HD-MTX based immunochemotherapy in the overall PCNSL patient population; however, long-term cognitive effects have not been reported and this approach has not been specifically assessed in elderly individuals in which the risk of neurotoxicity with WBRT is higher157, 177. More research is required before reduced dose WBRT can be recommended in elderly PCNSL patients.

Alternative approaches have been studied to extend the duration of response in older patients. For example, adapted HDC-ASCT is feasible promising154. For patients unfit for HDC-ASCT as consolidation, other strategies include maintenance MTX or treatment with agents that are better tolerated in this age group including oral alkylating agents (temozolomide and procarbazine), rituximab, lenalidomide and ibrutinib185–193. One randomized, phase II trial is evaluating maintenance with lenalidomide or procarbazine in newly diagnosed patients >70 who achieved CR or PR to induction chemotherapy (FIORELLA trial; NCT03495960). Moreover, the ongoing ALLIANCE A51901 phase I trial is investigating dose escalations of lenalidomide incorporated with HD-MTX and rituximab, with and without nivolumab, followed by low-dose lenalidomide maintenance in older patients with newly-diagnosed PCNSL who are not eligible for autologous stem cell transplantation (NCT04609046). In addition, a randomized, phase III trial is evaluating maintenance therapy with HD-MTX, rituximab, and temozolomide versus observation in newly diagnosed patients >60 who achieved CR to induction chemotherapy(NCT02313389).

Oral alkylating agents (i.e., temozolomide) and local therapies (ocular irradiation or intravitreal MTX injection) are acceptable options as first-line treatment for unfit patients with PVRL or patients with PVRL and contraindications to chemotherapy.

Relapsed disease and salvage treatment

Despite therapeutic progress in the treatment of PCNSL, there are several patients who do not respond to HD-MTX-based chemotherapy (15–25%) or who experience relapse after initial response (25–50%)9, 167, 168, 194. Relapse rates are higher among older patients, but prognosis is poor independent of age with a median OS of 2 months in primary refractory disease and 3.7 months in patients who relapsed within the first year of initial therapy195. Relapses occur mainly in the CNS, often in a different site than the primary lesion and are diagnosed in around a quarter of patients undergoing surveillance MRI9, 195, 196.

Treatment of relapsed/refractory (R/R) PCNSL represents an important unmet medical need as a standard of care has not been established. Thus, clinical trial enrollement should be the preferred option for these patients if available. In clinical practice, therapeutic choice should be based on available published data taking into account patient age, functional status, organ function, comorbidities and prior treatment. Salvage chemotherapy strategies could include HD-AraC or HD-ifosfamide combined with etoposide and/or carboplatin or cisplatin, possibly with rituximab, followed by consolidative HDC/ASCT in young and fit patients with R/R PCNSL or R/R PVRL who have not previously received it. Re-challenge with HD-MTX can be effective in patients who had a prior long-lasting response to this agent146. WBRT is an alternative salvage option, but despite a relatively high response rates (74–79%), the median OS is short with this treatment (11–16 months) and it is associated with a 15%−20% risk of clinical neurotoxicity197.

Multiple novel therapeutic agents are under investigation for R/R PCNSL and R/R PVRL (Supplementary Tables 2–4), of which the oral BTK inhibitor ibrutinib (Supplementary Table 2) and the oral immunomodulatory drug lenalidomide (Supplementary Table 3) are included in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines198 based on the evidence of activity190, 199. However, despite the high response rates with these agents (up to 50%−60%) both have a relatively short duration of response (<6 months). Thus, they should be used carefully and in selected patients, and such not interfer with enrolment in clinical trials that have more promise. The risk of life-threatening toxicities, such as invasive fungal infections with Ibrutinib200, should be highlighted as it can be abrogated with prophylaxis with isavuconazole201. Both ibrutinib and lenalidomide have been evaluated or are now being addressed in combination therapy trials. Of note, efficacy and tolerance of rituximab-lenalidomide-ibrutinib (R2I) therapy in those with R/R PCNSL were reported in a retrospective case series201 and is being investigated in a prospective phase 1b/2 study (NCT03703167). The second generation BTK inhibitor tirabrutinib is benefitial in patients with R/R PCNSL, with an ORR of 67%, regardless of MYD88, CD79B, and CARD11 mutational status202. Combining BTK inhibitors - particularly ibrutinib and tirabrutinib - with HD-MTX-based regimens is also being explored as first-line treatment. Lenalidomide has also been used as a maintenance strategy in R/R PCNSL after salvage treatment with MTX or WBRT189. Pomalidomide, a third-generation immunomodulatory drug, was also investigated in a phase I study in patients with R/R PCNSL or VRL in combination with dexamethasone, and demonstrated an ORR of 48% although the median duration of response was only 4.7 months203.

Monitoring

After completion of first-line treatment, patients with PCNSL should be undergo periodic clinical examination, peripheral blood examination, gadolinium-enhanced brain MRI, and ophthalmologic visits to confirm remission, detect relapse and exclude iatrogenic sequelae. Follow-up visits should be performed every 3–4 months for the first three years, every six months for the 4th and 5th years and the yearly. The benefit of assessing neurocognitive functions in routine practice is debated. Neurocognitive function assessment requires a complete assessment of pretreatment functions by using validated cognitive functions test panel such asthat proposed by the IPCG204, and periodically repetition of the same tests to distinguish altered functions and define decline severity.

Quality of life

Preservation of neurocognitive function is important in patients with PCNSL. Quality of life can be significantly affected by various factors, including the invasive nature of the lymphoma and the choice of therapy (such as HDC-ASCT or WBRT), as such therapies have been associated with neurological complications and negative effects on quality of life146, 167, 204. Avoiding such complications and preventing impairment of neurocognitive function can therefore be challenging, particularly in elderly and frail patients with low PS before therapy143, 144. The use of aggressive high-dose chemotherapy or combined chemo-radiation as first-line or consolidation therapy might be poorly tolerated in this patient population but appropriate dose reductions and improvement in supportive care have made this approach increasingly feasible18.

Of note, focal neurological deficits and cognitive or behavioral abnormalities are present at the time of diagnosis in 50–70% of patients with PCNSL96. Most patients who respond to induction and consolidation therapy demonstrate clinical improvement and, in some patients, neurological and cognitive function can improve to levels recorded before PCNSL diagnosis. Nevertheless, progressive decline in cognitive functions remains a major concern following intensive and multimodal therapies in patients with PCNSL18, 204, 205. WBRT is linked with worse neurocognitive outcomes (Box 3), particularly with doses >40Gy and in elderly indivduals206. Moreover, combined chemoradiation therapy is associated with disabling neurotoxicity with a cumulative 5-year incidence of 25% to 35% and related mortality of 30%206. The prevalence of both treatment-related mild cognitive dysfunction and late neurotoxicity in long-term survivors is probably underestimated, as formal psychometric evaluations have not been performed in most prospective studies207.

Box 3. CSF characteristics of leptogemingeal disease in PCNSL.

Glucose levels are usually normal (median 47 mg/dL)

Elevated protein levels (median 235 mg/dL) (in 92% of patients)

Elevated white count (median 96 cells/mm3)

Lymphocytic predominance

Positive cytology (2/3 with median of 2 lumbar punctures)

Positive flow cytometry

Owing to the toxicity of PCNSL treatments, emerging treatment trends are favoring either non-radiation based consolidation strategies (such as non-myeloablative chemotherapy or HDC-ASCT) or low-dose WBRT to minimize cognitive dysfunction146, 148, 157. However, whether reduced dose WBRT lowers the risk of long-term neurotoxicity is unclear. Preliminary data suggest that long-term survivors of hematological malignancies treated with autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplantation have similar results on parameters of cognitive function and quality of life compared with the general population146, 208, 209. However, further research is needed to better characterize long-term cognitive function in patients treated with ASCT.

Outlook

Improved diagnosis

International collaboration engaging a multidisciplinary team of physicians and researchers is an essential global strategy driving clinical research in the field of PCNSL. New diagnostic tools that are generalizable and easily reproducible need to be evaluated in prospective trials. Tumor cell free-DNA or biomarkers in CSF and/or plasma show promise as complementary tools to neuroimaging94, 210. However, these approaches cannot replace histopathological diagnosis on surgical biopsy, although interest in their use in patients with surgical contraindications is growing. Progress in neuroimaging and the use of new PET tracers will permit more accurate radiological suspicion and more timely diagnosis of PCNSL. The wider adoption of the 2021 consensus on imaging assessment, modalities, and techniques will be an important step forward in this field.7 Radiomics (extracting and analyzing high-dimensional data from clinical images) is under evaluation in different CNS tumours and could improve diagnosis and more accurately define treatment response, relapse, and neurotoxicity.

New therapies

The identification of molecules and pathways involved in the pathophysiology of PCNSL that could be new treatment targets is an important step toward the development of more effective treatments for this disorder. Some targeted agents have demonstrated efficacy in patients with R/R PCNSL, although responses are short-lived responses and some treatments are associated with potential dose-limiting toxicities (Supplementary Tables 2–4). Combinations of these agents with biological and/or chemotherapeutic drugs are being assessed in clinical trials.

One of these approaches for R/R PCNSL is to block programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) (Supplementary Table 4). Anecdotal data suggest clinical efficacy of anti–PD-1 blockade (using nivolumab and pembrolizumab) in R/R PCNSL; based on these datatwo multicenter phase 2 trials addressing their use as monotherapy have been performed, although final results are pending [NCT02857426 and NCT02779101]211, 212. Another promising approach for R/R PCNSL is CAR T-cell therapy (Supplementary Table 4), which is approved for treatment of R/R systemic DLBCL. Initial, small studies suggest this strategy is feasible in patients with R/R PCNSL, with some durable responses213, 214. Moreover, case reports in PCNSL and secondary CNS lymphoma have demonstrated the safely and efficacy of CAR-T214, 215, warranting further investigation of this cell therapy in PCNSL.

Therapeutic options for systemic lymphomas are increasing and comprise innovative pharmacodynamics and new-generation drugs with lower off-targets effects and higher efficacy. The use of these therapies for PCNSL is limited by the biological and pharmacological effects of the BBB. However, one novel strategy (tumor necrosis factor-alpha coupled with NGR) aiming to permeabilize tumor vessels and increase chemotherapy penetration in the tumor area in R/R PCNSL shows promise (Supplementary Table 4)216, 217. Other approaches have been developed to improve intratumoral diffusion of anticancer drugs in neuro-oncology. However, approaches aiming to bypass the BBB by direct intratumoral administration of antineoplastic agents (like biodegradable wafers or convection-enhanced delivery) seem to be less effective in a multifocal disease like PCNSL, whereas approaches aiming to increase BBB permeability by pharmacological means, focused ultrasound or methods exploiting normal transport mechanisms, seem to be based on more sound background218. Nanoparticles are an exciting approach to facilitate drug transport into the brain. Several approaches to overcome this barrier exploiting intrinsic transport mechanisms, like adsorptive-mediated transcytosis, solute carrier-mediated transcytosis and receptor-mediated transcytosis, are being explored in preclinical and clinical studies218.

Development of animal models

Singenic and orthotopic xenograft animal models of PCNSL have been developed and have provided important insights into the pathogenesis of PCNSL, particularly interactions between tumor and immune cells, chemokines, metabolomic analyses, tropism, and cell migration87, 219–224 Moreover, animal models have been used to investigate new therapeutic agents, particularly small biologics, like BTK inhibitors, immunotherapies and cell-based therapies225, 226. Available murine models of PCNSL result from the direct intraventricular or intracerebral injection of lymphoma cell lines220. One of the limitations of these models is that the biological characteristics of cell lines differ from PCNSL tumor cells from patients, therefore, interactions between injected cells and brain microenvironment, could differ. Moreover, the composition of the microenvironment may be altered due to post-injection inflammatory changes. Despite these limitations, animal models are important tools to improve understanding of pathogenesis and to identify new therapeutic strategies in PCNSL.

Supplementary Material

Box 4. Radiation-induced neurotoxicity.

Onset of radiation-induced neurotoxicity often occurs several months or years after treatment.

It is clinically characterized by neurocognitive decline, fatigue and mood alterations.

Imaging findings show brain volume loss, cortical/subcortical atrophy and diffuse injury to myelinated fiber tracts206.

Neuropsychological examination can confirm impaired psychomotor speed, executive function, attention and memory.

Brain damage results in dementia, ataxia, and incontinence.

The median survival after the onset of neurotoxicity is <1–2 years229.

Autopsy findings may reveal a combination of myelin and axonal loss, gliosis, spongiosis, small and large blood vessel injury, and sometimes blood vessel thrombosis230.

Competing interests

AJMF has received speaker fees from Adienne, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Novartis, and Roche; was a member of advisory boards of Abbvie, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genmab, Gilead, Incyte, Juno, Novartis, PletixaPharm, and Roche; and currently receives research grants from Abbvie, Amgen, ADC Therapeutics, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Beigene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Genmab, Gilead, Hutchison Medipharma, Incyte, Janssen Research & Development, MEI Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Pharmacyclics, PletixaPharm, Protherics, Roche, and Takeda; and holds patents on NGR-hTNF-α in brain tumours and NGR-hTNF/R-CHOP in relapsed or refractory PCNSL and SNGR-hTNF in brain tumors.

KC has received speaker fees from Roche, Takeda, KITE, Gilead, Incyte, Celgene/BMS as well as Consulting fees from Roche, Takeda, Celgene, Atara, Gilead, KITE, Janssen and Incyte.

JD has been consultant for Blue Earth Diagnostics, Magnolia, and Unum Therapeutics; has received research support from Beacon Biosignals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Medimmune, Acerta Pharma, and Orbus Therapeutics; and has received royalties from Wolters Kluwer for serving as an author for UpToDate

CG has received research support from Pharmacyclics, Bayer, and Bristol Myers Squibb and has acted as a consultant for Kite, BTG, and ONO.

KHX has received consulting fees from BTG.

LSH is co-founder of Precision Oncology Insights.

GI has received speaker fees from Roche and Gilead as well as honorary as member of advisory boards of Gilead, Incyte and Roche; institutional funding for work in clinical trials from the German Ministry of Science.

LN has consulted for Ono Pharmaceutical, Genmab, and BraveBio, and has received clinical trial research support from Merck, Kazia and Astra Zeneca, and delivered Continuing Medical Education (CME) lectures for Oakstone Medical Publishing and Neurology Audio Digest.

TC has received consulting fees from Janssen-Cilag.

MP and TTB have declared no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kluin PM, Deckert M & Ferry JA in WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 300–302 (IARC, Lyon, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alaggio R et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms. Leukemia 36, 1720–1748 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campo E et al. The International Consensus Classification of Mature Lymphoid Neoplasms: a report from the Clinical Advisory Committee. Blood 140, 1229–1253 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiels MS et al. Trends in primary central nervous system lymphoma incidence and survival in the U.S. Br. J. Haematol 174, 417–424 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferreri AJ et al. Summary statement on primary central nervous system lymphomas from the Eighth International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma, Lugano, Switzerland, June 12 to 15, 2002. J. Clin. Oncol 21, 2407–2414 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Velasco R et al. Diagnostic delay and outcome in immunocompetent patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma in Spain: a multicentric study. J. Neurooncol (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barajas RF et al. Consensus recommendations for MRI and PET imaging of primary central nervous system lymphoma: guideline statement from the International Primary CNS Lymphoma Collaborative Group (IPCG). Neuro Oncol. 23, 1056–1071 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Consensus recommendations for neuroimaging of the International PCNSL Collaborative Group.

- 8.Baraniskin A & Schroers R Liquid Biopsy and Other Non-Invasive Diagnostic Measures in PCNSL. Cancers (Basel) 13, 2665. doi: 10.3390/cancers13112665 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Houillier C et al. Management and outcome of primary CNS lymphoma in the modern era: An LOC network study. Neurology 94, e1027–e1039 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dandachi D et al. Primary central nervous system lymphoma in patients with and without HIV infection: a multicenter study and comparison with U.S national data. Cancer Causes Control 30, 477–488 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haldorsen IS et al. Increasing incidence and continued dismal outcome of primary central nervous system lymphoma in Norway 1989–2003 : time trends in a 15-year national survey. Cancer 110, 1803–1814 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ostrom QT et al. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2010–2014. Neuro Oncol. 19, v1–v88 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]