Abstract

Custom and tradition played essential roles in developing the built environment among the Balinese Hindu society for centuries. The wisdom in managing the environment has passed through generations, as demonstrated by some ancient remnants and Old Balinese inscriptions. We observed that glorifying the mountains in this society has long been a part of protecting the hydrologic cycle. This practice even started in the pre-Hindu era, as shown by sacred megalithic features adjacent to the natural reservoir, water spring, and mountainous forest. At some point, the behavior has successfully passed through times and even developed into a more complex socio-cultural system such as subak. Nevertheless, Balinese society is now facing the threat of hydrological disasters, primarily due to a rapid change in land use. Here, we describe the importance of revealing the value behind the ancient Balinese water-management system to gain people's resilience and sustainability. Multidimensional scaling (MDS) was used to measure the sustainability index and the leverage factors affecting water tradition in Bali. We reveal that the inheritance of the Balinese people's water management tradition is generally weak in each dimension. The socio-cultural dimension score is relatively high, with a sustainability score of 71.11%, which signifies that the society still trusts their culture of water resources management to protect nature. However, the economy and ecology dimensions' score low, with sustainability scores of 56.12 and 63.34%, respectively, indicating the need for improvement in economic matters through the policy strategy. Moreover, our study also suggests that the noble value of the cultural heritage related to the water management system needs to be revitalized and disseminated to the public. Hence, the implication is not limited to conserving the natural environment and cultural heritage. It also provides a reference for the current society regarding a built environment in harmony with sustainability principles.

Keywords: Built environment, Water management, Sustainability, Multidimensional scaling, Subak

1. Introduction

The Balinese society is known for having a unique tradition that essentially affects the conservation state of their surrounding environment. Retaining harmony between the realm of belief, society, and nature has become fundamental among the Balinese society for centuries. It is evidently shown by numerous remnants and old inscriptions related to environmental management during ancient Bali. Although they live in a ‘built environment’—as any other society does—it always reflects local wisdom as a part of their commitment to natural conservation. This wisdom tends to prolong the preservation state of their surrounding environment, manifested by a distinctive strategy of modifying and managing nature until it meets a balance between people's needs and conservation [1].

One of the most prominent practices among the Balinese society that shows wisdom in developing a built environment is their traditional water management. There is an indication that the water management and glorification performed by the people of Bali have been started since the pre-Hindu era. It is shown by several megalithic discoveries (e.g., dolmen, menhir, and stone vessel) situated near a natural reservoir, water spring, upstream rivers, and mountainous forest [[2], [3], [4]]. The custom of placing a simple structure made of natural or slightly modified stones has continued in recent times. A simple formation of stones or even a single monolith is often found near a well, a conflux, a small creek, and an irrigation canal. Although separated by a long time gap, the main objective remains the same. It is a manifestation of the Balinese custom related to water glorification.

The considerations of harmony and sustainability were the fundamental philosophy of the development of several built environments of water civilization during the ancient Bali era in the 10th century, such as the management of the area of Pakerisan River as an effort of the ancient Balinese to glorify water [5,6]. When Majapahit's influence reached Bali in the 15th to 17th century, the Balinese kings built Taman Sari temple, which had religious purposes and ecologically served as an infiltration well and to keep the water supply for the subak irrigation system. The farming irrigation system known as subak is a built environment designed to manage water effectively and fairly [7,8]. The subak system is an ecological manipulation effort performed by Balinese people to preserve the sustainability of the water. However, the preservation of this system faces great challenges in socio-cultural, economic, and legal aspects [[8], [9], [10], [11]]. Subak system has a low sustainability index [12], while water frequently becomes a dilemma between tourism and agriculture as its management has not been unified yet [13].

A small amount of optimism is still alive even when an effort needs to be made before it is too late. The Balinese people's Traditional Ecology Knowledge (TEK) needs to be examined by mapping some local heritages of water management systems and realizing their sustainability, then deciding on suitable efforts to revitalize them so the people could utilize those heritages. Some previous research results proved that local knowledge plays potential roles in identifying environmental issues [14,15], supporting the technical research required to understand environmental issues and inform future policies [14,16]. Besides, the natural conservation agencies have also realized that the diversities of culture, knowledge, and practice of the traditional society also contribute to the understanding and protecting of the environment, natural resources, and biodiversity. The World Heritage Convention conducted by UNESCO in 1995 proposed a new cultural landscape category by acknowledging the complex relationship between human beings and nature in developing and protecting the landscape [17].

In this stage, the research on the built environment of water civilization examines the Balinese people's water management philosophy, reveals the sustainability values written on the artifacts discovered at the water management system sites, and scrutinizes the sustainability index status. In the matter of sustainability, there are two meanings. First, the cultural continuity that exists until today. Second, how to fulfill the needs today without sacrificing the next generation's needs fulfillment. It could be done by utilizing natural resources while also conserving the environment at the same time. People need to protect the hydrology cycle by sanctifying the area and utilizing it sustainably.

Several sites would be observed in some areas in four regions that are still utilized by people today. The four samples of the regions of Denpasar City and the regencies of Badung, Gianyar, and Tabanan were chosen since, as tourist destinations, they are prone to massive land use change. The first step of observation starts at the built environment of river management, Taman Sari, and the traditional irrigation system using a socio-cultural approach to examine the Balinese community, starting from its ideology (superstructure), traditional regulation (social structure) to its adaptation system (infrastructure) [18] and find out if they are in line with the harmonious Balinese concept of Tri Hita Karana (maintaining harmony relationship between human and God, among fellow human beings, and with the nature). This research applies the conceptual operational approach proposed by Faber et al. [19] to examine the cultural heritage sustainability aspects. Three aspects can be used as references in observing the sustainability state:

-

1.

Observing the artifact since it is physical evidence of sustainability.

-

2.

Observing the aspect of goal orientation. It is a point of reference where an object can be considered sustainable. Examining the sustainability aspect of an object of the built environment requires a cross-discipline approach with an ethnoscience method to understand and articulate the local people's knowledge.

-

3.

Studying the interactions between the built environments chosen to be the research sample are still utilized by the people or, on the contrary, needs to be revised.

To discover the level of sustainability, this research applies the Multidimensional Scalling (MDS) method [20] to find out the sustainability index and the leverage factors that create the unsustainability that requires certain treatment to fix it up.

It is understood that water problems in Bali are complicated, as stated by Stroma Cole and Mia Browne, who studied the inequality of water in Bali using a social ecology approach to point out the factors that continuously threaten the water security in Bali [13]. Water flow and its usage are complex and unpredictable. On the other hand, the economic power of tourism adds to the uncertainty. Besides, there are other factors of culture, poor management, ineffective rule enforcement, lack of monitoring from cross-discipline experts, and lack of feedback required for adaptive management. It is also worth noting that the hydrology knowledge of the Balinese people is not only an essential need but also has a sustainable spiritual meaning that is still adhered to and becomes a lifestyle. It needs to be strengthened as a good practice.

Serious efforts are required to control the speed of Balinese natural degradation due to unsustainable tourism development. Bali needs fundamental and comprehensive rearrangement. The noble values still followed and becoming a good practice can be revitalized to manage Bali's built environments, particularly those related to water management. Based on the explanation above, several research queries are formulated: How was the physical appearance of the built environments for water management created by the Balinese people in the past? What are the points of reference as a starting point that describes an object of the built environment of water civilization, the sustainable one? Last, how do the community members interact with the cultural heritage of built environments? Is it static or dynamic? What is their sustainability status?

This research aims to comprehend the fundamentals of water civilization in Bali by understanding the concepts of upstream-downstream in the built environment related to the water management. We hope that the result will provide an alternative solution for the water management problem by looking at the knowledge of the ancient Balinese society. We argue that the knowledge of the built environment in Balinese society must be transferred through generations. The continuity of certain customs, such as subak as a traditional water management system, indicates it. Furthermore, identifying the archaeological evidence related to the water management system and the built environment during the past is also described to corroborate our study.

2. Data and Method

The primary data were collected through a preliminary observation then followed by a series of descriptions to identify relevant matters in the scope of built environments for water management. We have also examined the existence of local community wisdom and its empirical meaning. The qualitative approach then applied to test the people's view toward local wisdom practiced by the cultural community to manage the water in several regions in Bali. Subsequently, more information collected through interviews, document analysis, and observations. We used a questionnaire as instrument, that given to the residents around three sites of Jatiluwih, Tirta Empul (Pakerisan watershed), and Taman Ayun Mengwi. A purposive sampling strategy was chosen because respondents' characteristics were already defined [21] to be adjusted to the purpose of this study. However, the number of residents related to the water management system and the built environment of the three sites is hardly defined, so the precise number of population is unknown.

About 90 residents were selected as our respondents, almost three times the minimum number of respondents (between 30 and 34 respondents) proposed for a non-probability sampling in an unknown/undetermined population [[22], [23], [24]]. The sustainability status is tested using the analysis method of MDS [20] to observe six influential dimensions of ecology, economics, socio-culture, human resources, technology infrastructure, and legal-institutional. Each from those five dimensions then subdivided into 10 attributes that arbitrary defined based on our preliminary observation made in the field. The steps of the ordinance process use Rapfish-modified software [25].

The respondents are selected using a cluster sampling technique to fulfill the principle of representation of each region being studied of Denpasar, Badung, Gianyar, and Tabanan. The respondents are stratified or grouped, while the types of built environments of petirtan, irrigation, and well are clustered. Next, the community members who manage each cluster's sites, visitors, and traditional rulers were chosen as research respondents. The observed modifier consists of six dimensions. Each dimension was measured with ten observational attributes. This strategy was selected since various factors affected the development of local knowledge in a certain time and space. We also look for the dynamics and strategies of the Balinese people in managing water resources to maintain sustainability, both in modern and traditional ways Besides the questionnaire, we also used observation forms (the list of observational activities), interview guides, focus group discussion (FGD), and Rapfish software to perform MDS analysis.

Most of the water built environments inherited by the people of Bali are still functional and used by the people for ritual, irrigation, and domestic purposes. This happens because the people of Bali adhere to their ancestors' teachings. In the Balinese belief system, each activity always refers to soko guru as their guidance, such as when building a house or place of worship and making water built environments. It needs to be examined if the people who inherit these traditions understand that the built environments created by their ancestors have the purpose of nature conservation.

To measure the people's understanding, the questionnaire results from the respondents are analyzed using the MDS method. Respondents answer ten questions from ten attributes of each variable. The respondents' data are collected from three built environments of water management still used by the people of Bali today. The sample is chosen randomly, comprising the management representatives, users, and related stakeholders. They need to fill in a questionnaire. The questions are related to six dimensions of socio-culture, ecology, economy, technology, facility, and legality of their institution. For each dimension, there are ten attributes asked to the respondents. From a socio-cultural perspective, there are three essential elements of ideological superstructure. First, the belief system of the Hindu society. Second, the social structure related to the domestic role of water in the Bali community and the traditional regulations that become the standards. Third, the material infrastructure of the adaptive harmonious relationship between human beings and the environment.

The people of Bali's habit of preserving nature and the environment have become a lifestyle based on the philosophical guidance of Tri Hita Karana. However, the ecological change in water civilization also happens during the rapid land use change caused by a high level of hedonism among the people. An occupational switch from farming to tourism also happens [12]. Based on the research results, what happens in the built environment sites of water civilization inherited by the people of Bali for thousands of years could be seen. Knowing the leverage factors related to water resources management in Bali is also important. Those leverage factors could be the reference when making strategies and policies on sustainable water resources management.

The sustainability analysis of water resources management is performed through several stages. First, deciding the functional attributes in water resources management includes five dimensions (ecology, economics, socio-culture, technology-infrastructure, and legal institutional). The ordination process stage uses modified RapWater software [25] to see into the territorial area [26]. The grading stage of each attribute in ordinal scale is based on the sustainability criteria of each dimension, ordination analysis based on MDS analysis, and organizing the sustainability index and status of the functions of the existing condition of water resources management reviewed in general and in each dimension [27].

The stages of MDS with general explanation are described below.

-

a.

Deciding the dimensions and attributes based on the problem.

-

b.

The data gained from questionnaire results and the real condition at the research area would be calculated using pairwise comparison based on the importance scale [28] for inter-dimensional comparison and to give a score to each attribute,

-

c.

Deciding the good and bad primary references by giving good and bad scores to each attribute.

-

d.

Making two primary points of “middle point” that are the bad and good points. Two additional primary references become the vertical reference (up and down).

-

e.

Making additional points of reference called anchors to help the ordination results.

-

f.

Making the score standardization for each attribute using the method:

Note:

= The standard score area (including the point of reference) of 1, 2, …., n in each attribute of k = 1, 2, …., p;

= The initial score area (including the point of reference) of i = 1, 2, …., n in each attribute of k = 1, 2, …., p;

= The medium score of each attribute of k = 1, 2, …., p;

= The standard deviation of the score in each attribute of k = 1,2, …p.

-

g.

Making the ordination for each attribute of every dimension. The ordination result is visualized using the horizontal and vertical axis with a rotation process so the point's position can be visualized in the horizontal axis with the sustainability index scores of 0% (bad) and 100% (good).

The sustainability index of the water resources management functions has a 1% interval to 100%. The function is sustainable if the studied system has an index score of more than 75% (>75%). The function is weakly sustainable if the index score exceeds 50% (>50%). The function is less sustainable if the index score exceeds 25% (>25%). The function is unsustainable if the index score is less than 25% [29,30].

3. Identifying the archaeological heritage of water built environment in Bali

3.1. Physical shape of the structure

Several physical structural shapes of the built environments inherited by the people of Bali are from the pre-Hindu era. Some megalithic heritages that still exist today prove that the people of Bali always glorify and protect nature. They protect their mountains, forests, wells, lakes, and rivers. Through their heritage and megalithic culture of the stone throne, they believe that the holy spirits of their leaders and ancestors bless them and protect their nature and its fertility [3,4]. This tradition nowadays is still adhered to by the people of Penebel in Tabanan to protect the Batukaru Mountain and to glorify the Tamblingan Lake as the source of life. Glorification and protection of the water resource and nature continued during the Hindu era in Bali. One of the archaeological heritages discovered in Bali, among others, is the management system of well and river known since the era of ancient Bali that is well in Pura Tirta Empul from the 10th century stated in the Manukaya Inscription dated 960 AD [31,32]. The inscription mentions that King Chandrabhayangsingha Warmmadewa repaired the dam at Tirta Empul due to damage caused by floods every year. The inscription also tells that the well was used for irrigation. Nowadays, the well of Tirta Empul is still used for subak in Kumba and Pulagan in Pejeng Village. The inscription is from the 10th – 11th century, and Bali in that era was a kingdom ruled by Warmmadewa Dynasty [31,33]. Tirta Mengening is located near Tirta Empul, and it has Pura Mangening with a prasada or temple and a sacred well inside.

Built environments built along the watershed of the Pakerisan River are stated in Tengkulak Inscription from 945 AD [34]. Several temples are built on the riverbank starting at Tirta Empul as the upstream to the downstream of Candi Mengening, Candi Gunung Kawi (from the 11th century), and Candi Pengukur Ukuran, respectively. While in the watershed of the Petanu River, there is a sacred pond called Petirtan Goa Gajah from 1022 AD [31,32]. This site has a complex of sacred ponds with six shower statues with a height of 2.30 m. The written inscriptions state the Pakerisan River more frequently than the Petanu River, yet those two have served the essential roles of providing water for religious rituals, people's domestic needs, and irrigation since the era of ancient Bali.

3.2. The ancient Bali inscription source

Since the era of Ancient Bali, water use for irrigation has been of significant and strategic importance. It can be seen from subak as a built environment for water management for irrigation has been around since the 10th century, as stated in many inscriptions using the ancient Balinese word of kasuwakan, which is the word origin of subak, the Balinese traditional irrigation system. The inscriptions mentioned some people: a water tunnel maker (undagi pangarung), a dam maker (dawuhan), and someone called makahaser or person in charge of the water management system. It is called Pekaseh in today's terms. Bebetin AI (896 AD) and Trunyan Inscription (911 AD) are the earliest inscriptions mentioning makahaser.

In the era of Ancient Bali, the community irrigation organization in Bali was given special authority by the rulers to expand their irrigation networks. This is written in several inscriptions. Celepik Inscription, released in 944 Saka or 1072 AD by King Anak Wungsu [35], stated that the people were free to use the land and to expand the irrigation networks. The Lutungan Inscription issued by King Anak Wungsu in 975 Saka or 1053 AD mentioned that the people of Lutungan Village were free to take water to irrigate their fields. The Bwahan D Inscription released by King Jayapangus in 1103 Saka or 1181 AD [36] informed that the people were free to take water and expand the irrigation system networks. Kings in that era had a great concern for the community members asked to manage the tax-free water and sacred buildings. Sembiran Inscription released in 975 AD stated that Indrapura Village and its surrounding villages were tasked to protect the pendems (graveyards), prasadas (temples), water fountains, ponds, and sacred buildings. Hence, they were tax-free, including the tax for the kings.

The forest preservation concept seemed to be known during the Ancient Bali era. Besides water preservation, the forest was also required as the hunting area for the kings. Buahan B Inscription [36], released in 1025 AD by King Maraka, stated that the residents of Bwahan Village asked permission from King Sri Dharmawangsa Wardhana Marakata Pangkajasthanotunggadewa, the son of King Dharmodayana (Udayana), to buy the forest that the king used for hunting located close their village. The king granted their wish, and they needed to pay 10 ma and 10 pilih. The length of the area they bought was 900 depa × 1100 depa (one depa equals the length from fingertip to fingertip of the outstretched arms of an adult). Fair water distribution was also recognized in the era of ancient Bali. The tool used to manage and distribute water effectively was called tembuku.

4. The ecological manipulation of the built environment for water conservation

The cultural value of several cultural heritages of the built environment inherited by the Bali people must be rediscovered and scrutinized. Strategies are required to develop holistic interpretation and a multi-disciplinary and inclusive approach [37]. Understanding the ethnoscience values inheritance requires integrating scientific knowledge and local knowledge, particularly those related to the wisdom of resource management [38]. One of the examples was the people's effort during the Perundagian Era to purify and glorify mountains as an essential part of the hydrological cycle. The people built a number of ancestral worshipping symbols, such as the stone throne, as a medium for worshipping the ancestor through glorifying the mountains that are considered the resting place for the ancestor's spirit. People glorified and worshipped the mountains as a natural power unified with ancestral spirit for the people's prosperity [3]. Therefore, when designing the spatial pattern, the Balinese elders need to keep the harmony and security of the environment by creating a vital concept of Kaja Kelod. Kaja means mountain, and kelod means the direction downstream.

Each practice of worship and development refers to the concept of Kaja Kelod that directs upstream-downstream (luan teben). The concept of Kaja Kelod, which places the direction of kaja or mountain, means that the upstream area of the mountain and forest needs to be preserved as the source of life. The water's streamline needs to be protected and guarded through the river to the downstream based on the Balinese concept of Nyegara Gunung. It is a concept of an upstream-downstream entity: sea (segara) and mountain (gunung) are unseparated entities. Each action in the mountain will affect the sea. As discovered by various scientific research on watershed river areas, upstream and downstream are two related entities [[39], [40], [41]]. Forest cover in the water catchment area upstream is essential to manage the river stream for the people living downstream [41].

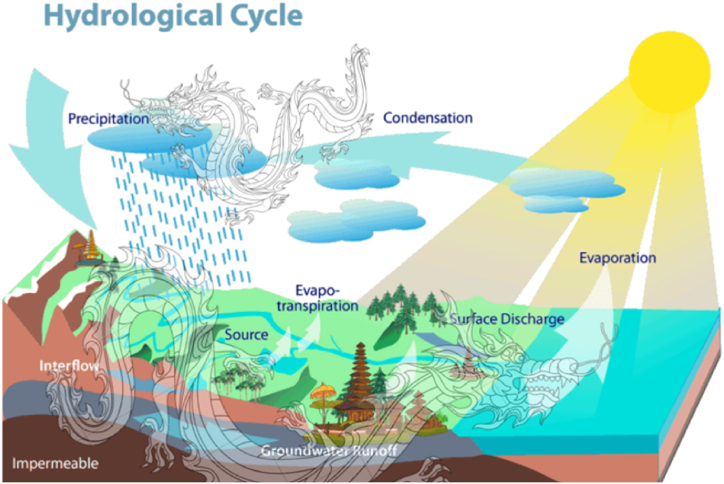

The ecological manipulation efforts done by the people to conserve the environment through belief systems and rituals put mountains as the center of the natural power of providing fertility through the water they stream. Mountains deserve to be protected and glorified to protect the hydrological cycle. The people's understanding of the hydrological cycle is manifested through the dragon symbols of Naga Basuki and Naga Taksaka. The Naga Basuki dragon symbolizes the water stream, while the Naga Taksaka dragon symbolizes clouds or air in the sky. The tail of Naga Basuki in the mythology of Manik Angkeran is pictured aiming at the sea. Therefore, it could be interpreted that Naga Basuki is the symbol of pure water coming from the mountains (jewel tail), and the polluted estuary at sea is symbolized by the head and poisonous fangs of the dragon [42] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The Balinese's understanding of hydrological cycle through symbols (picture: Gede Awantara).

This is the manifestation of the Balinese people's biocentrism concept known as the concept of Bhuana Agung (macrocosm) and Bhuana Alit (microcosm) practiced by the rituals of glorifying nature. The implementation of cosmic solidarity is that all cosmic creatures are equal [43]. Building a sustainable relationship with Earth will lead our actions according to the natural reality. Civilized society requires ethics [44].

From several great water management sites in Bali, we can see the people's socio-cultural effort to manage and protect the natural resources related to the hydrological cycle. A few archaeological sites that can be practical examples today, among others, are (a) Jatiluwih, which inherits the pre-Hindu traditions to protect mountains, lakes, and forests as parts of the hydrological cycle; (b) Tirta Empul and its watershed area which are the proofs of ancient Bali civilization effort to manage the well and the watershed area since thousand years ago until nowadays; (c) Taman Ayun which is the evidence of the Balinese kings' effort in the 15th to 17th century to manage the water for subak irrigation system for people's prosperity; (d) The downstreaming civilization of water management system in Bali is subak with a system that manages fair and sustainable water use.

4.1. The people of Jatiluwih glorify lake and forest to protect the hydrological cycle

Jatiluwih, which is famous for its traditional irrigation system, has inherited the area management of the upstream by glorifying forest and mountain practices since the Perundagian Era in the early first century. Many megalithic heritages related to water glorification are discovered in this area, and the culture is still practiced today. Besides managing the irrigation system, the traditional water management of subak also protects the ecosystem and hydrological cycle. The people are responsible for protecting and preserving the forest in Batukaru Mountain and Tamblingan Lake, which is believed to be the source of life. The making of Catur Angga Temple by the people of Bali of Pura Tamba Waras, Pura Petali, Pura Batukaru, and Pura Besi Kalung has an important objective to support the sanctity of the Batukaru Mountain and its forest. People implement their responsibility by performing rituals or taking actions to protect the area together, making the miniatures of some temples located in Tamblingan Lake in the area of Jatiluwih Village as a symbolic gesture of their responsibility toward the lake as a part of the hydrological cycle that needs protection, even if the location of the village and lake are faraway. People believe that water flowing from the rivers and wells in the Jatiluwih Village comes from Tamblingan Lake. The downstreaming effort of the hydrological cycle is for the water needs of the Tabanan people and the subak community members, particularly in the 14 areas of Subak Jatiluwih. Next, the subak community members use their system to manage water effectively and fairly. Even if Jatiluwih has many wells, the subak system manages water distribution fairly.

Similarly, the worship and ritual of wana kertih asking for forest protection, and danu kertih ritual asking for lake protection aim to keep the ecosystem balanced. There are many rituals, such as performing sacred sacrifices and lake purification and building holy sites in the wells upstream to protect their existence. Protecting nature means serving God. Jagat Kertih is an effort to preserve dynamic and productive social harmony based on truth and Tri Hita Karana, which is the foundation of the social institution of Desa Pakraman in Bali [45].

4.2. The glorification of Tirta Empul well and Pakerisan River watershed

Besides glorifying places for the king and meditation, the worshipping sites along the Pakerisan River are also used to glorify the water sourced from the wells from Batur Mountain and Lake. Protecting wells and rivers is part of the effort to keep the existence of the hydrological cycle from upstream to downstream. A more comprehensive example of the hydrological cycle can be seen at Tirta Empul. It is a pura petirtan or water temple built in the 10th century during King Jaya Singa Warmadewa era. The area of Tirta Empul is located nearest to upstream than the other temples built on the riverbank of the Pakerisan River (Fig. 2). Its development was designed hierarchically since the period of ancient Bali kings. The location of Tirta Empul was chosen nearest to the upstream, and its period was the oldest one dating back to the 10th century. Based on the hadrochemical analysis, it is found that the klebutan (well) at Tirta Empul has the same age as the sacred structures there. This indicates the ancestors' precision in selecting the location for the holy site since it is located at the oldest well in the area of Pakerisan River watershed [46].

Fig. 2.

The temples for water management along the Pakerisan River (Image: Archaeological Service Office of Bali).

The holy site was built on the riverbank to protect the area from the people that would destroy and pollute it. Hence, the area was deemed sacred so the locals would not exploit it. Garret Ardin proposed The Tragedy of the Common theory, which portrays a condition where people think that natural resources belong to all, so everyone can exploit them without any responsibility to protect their sustainability. The river border management could also indicate an effort to protect the river. The space between the riverbank temple and the river is filled with a border with a width equal to the river's width. This calculation still exists in Bali, but the width of the river border is now half of the river's width. The 10th century inscriptions also state the prohibition of building structures on the riverbank and cutting particular kinds of trees. The water circulation is managed well so its existence can be sustainably managed. This practice can be seen at Candi Mengening located near Tirta Empul. This site has a gradual pond. Water from the main well goes to the first pond through a water shower. Such water is used for ritual needs. The water next goes to the second pond, which is broader and functions as an infiltration well. Water in this pond is also distributed to several sites of subak through irrigation canals. Therefore, it could be concluded that making sacred ponds, temples, riverbank temples, and meditation sites is meant to protect the water wells, so the Pakerisan River watershed is sacred and protected from exploitation [47].

Ecologically, three elements must be examined in the hydrological cycle at Candi Mengening. First, surface runoff management is done by developing a pond as a controlling facility or runoff retainer. Based on functions, the controlling facility or runoff retainer can be categorized into storage and infiltration types. The facilities of retarding ponds and regulation ponds are examples of the storage type [48]. The principle of infiltration-type facilities is to decrease the amount of runoff water and delay the water's residence time in the ground, so the flood risk can be limited while also increasing the amount of groundwater.

The second element is vegetation. Certain trees supporting the hydrological cycle, such as hara and banyan trees, are selected. It could be observed that the vegetations in several wells and upstreams are mostly trees with strong roots. This could be seen at Mengening Gianyar, which has lush banyan trees. Such vegetation rooting would increase the soil porosity affecting the infiltration level. The higher the infiltration level, the lower the amount of surface runoff that creates erosion [49]. The effort to protect the well and forest by sanctifying the environment through the development of glorifying structures. Besides rituals, the sacred water is also for domestic needs, bathing, and subak. The subak community members use the water for irrigation. They create a sustainable management system.

One of the efforts to protect the wells upstream is by taking contributions from the subak community members who use those wells. This tradition has existed since the 10th century, as stated in Mantring C Inscription released by King Jayapangus in 1181 AD. It says that the subak community members who use the wells must offer certain things [35]. This tradition still exists today during the ritual at Pura Mengening when people bring some offerings to the temple.

Another vital element is open green space in a broad area, such as karang tuang (vacant land), alas kekeran (village forest) functioned as the catchment area. The functions of those elements are the parts of the water management pattern process in the hydrological cycle. The surface runoff water or water from the well can return to the ground through the infiltration well. The surface runoff water to the river or pond evaporated through vegetation in hutan kekeran (the sanctified forest) would be important in the hydrological cycle.

4.3. Water management applied by the King's palace through Bale Kambang (water structure)

During the era of Balinese kings in the 15th to 17th century, almost all kingdoms paid much attention to water management, particularly for irrigation, such as the Kingdom of Mengwi, which built Taman Ayun. Besides for ritual, this building was a facility for subak water management. The building has the characteristics of Bale Kambang or a building in the middle of a pond. The pond holds the water that would later be streamed to the irrigation channels in several subak networks. Bale Kambang in Bali bears similarities with Candi Tikus Temple in East Java, surrounded by a pond whose water comes from two dams of Gemitir and Karaton managed for farming irrigation [50]. The trend of those structures in the 15th to 17th century seems to be affected by Majapahit Kingdom (East Java), as seen from the mythological concept of Pemuteran Gunung Mendara Giri. The building in the middle of the pond symbolizes Mahameru Mountain, while the surrounding pond symbolizes samudra menthana. Once upon a time, Vishnu saved tirta amerta from Asura for the sake of people's prosperity. This concept becomes the point of reference in water resources management for the people.

The king positioned himself as the incarnation of god. The belief called Dewa Raja or God King has been developed since the 10th century, and its essential concept is that the kings personified themselves as the incarnation of Vishnu [51]. Hence, the kings had the responsibility to welfare the people through natural resources management, including managing water for people and farmers. Politically, this effort was made to create a legacy and strengthen the king's power and influence. Bale Kambang buildings are found in several palaces of Balinese kingdoms, such as Puri Kelungkung which built Kerta Gosa, Puri Karangasem which built Taman Tirta Gangga, and Taman Ujung as water management facilities. These include a few wells managed by the indigenous communities today and still functional, such as Taman Mumbul in Badung, and several wells preserved by the people. This water management system is still used as a model by the Balinese kings, who created a built environment of pond using the concept of Bale Kambang as a water reservoir facility to support the subak system. In this area of Taman Sari, it was also built several Pelinggih Penyawangan or worshipping sites to worship the god of fertility and Dewi Danu (the goddess who rules the lake) and also to glorify the wells. This means an invitation for the people to learn to be responsible in managing natural resources sustainably. Not only should they protect water, but they should also protect its origin, including protecting the mountains as the source of life, which play vital roles in the hydrological cycle.

4.4. Sustainable water management and distribution system using subak

The downstreaming effort of hydrological cycle management is an agricultural irrigation system called subak in Bali. This traditional system has been around for thousands of years. The Balinese people's understanding of the hydrological cycle and water resources management can be divided into macro and micro efforts. The macro effort deals with protecting and managing nature, which relates to the sustainability of water resources. The micro effort relates to the implementation of creating a sustainable built environment using the subak system. The irrigation culture still thrives based on the philosophy of harmonious relationships between human beings and nature, which later is elaborated with the concept of Tri Hita Karana to protect the harmonious relationships between human beings and God. This is implemented by activities in the built environment, such as making pura subak and pura penyawangan to glorify the wells. People inherited the traditions of glorifying the mountains and lakes by making sacred buildings to worship Dewi Danu. From a hydrogeology perspective, there is a connection through the underground water network from Tamblingan to Jatiluwih in Tabanan and from Batur Lake to Pakerisan River. It means the structures the ancestors had built are not only merely metaphysic symbols but can also have empiric meaning. The ritual of Magpag Toya (picking up the water) also has a message of conservation since before the ritual takes place, the people work together to clean up the irrigation channels and wells and take care of the surrounding vegetation.

Second, the relationship among fellow human beings. The harmony in using the water among the subak community members is based on the same standard of one tektek or traditional water measurement unit. One tektek equals the water volume that goes through the cross-section (water door) with a width of 5 cm and depth of 1 cm in a small dam to water a 35 to 50 are field. A field that size requires a tenah or a bundle of seeds weighs 25–30 kg. Hence, the size of the field is measured using tenah, while a tenah is about 35–50 are. In the past, way before the metric system was introduced, one tektek was measured using four fingers being laid. Since each person's finger size varies, the measurement would be different. The standardized measurement is meant for the effectiveness of water use so people can use the water fairly. They also have the tradition of loaning and borrowing water. The rights and responsibilities of the subak community members are regulated by traditional rules called awig-awig.

Third, related to the harmonious relationship with the environment, society makes an effort to manage the water by considering its sustainability. The steep land is made into a terrace so the land would not experience fast water runoff from the top across the slopes. Some other efforts are done by protecting the plants and forest in the upstream area and by managing the planting pattern using a traditional system called kartamasa tulak sumur (planting pattern switch system from rice to other plants). The water distribution procedures of the traditional irrigation system of subak are as follows. First, the subak community builds a dam in a river (many dams are made by the government) (1) then the water goes through tembuku (water door I) (2) to be streamed to the primary channel called telabah gde. (3) The quantity of water allowed to go to the primary channel is decided among subak communities. From the primary channel (3), the water is streamed and divided by tembuku aya (water door II) (4) to the secondary channels with the portion of water equal to the size of each tempek. Next, water from the secondary channels is divided by tembuku pemaron (water door III) (6) to the tertiary channels (7). Then, the water is divided again to the pickup channel or quarter channels called kekalen penyuangan (9) through tembuku gde (water door IV) (8). From the pickup channel, the water is streamed to the fields using temuku cerik (small dike) (10) then goes to the input channel cross section (11). The size of the input channel cross-section is based on the size of the fields of the subak community members. The remainder water can then be used to water other fields below.

5. The sustainability status of the water management tradition in Bali

5.1. Sustainability status

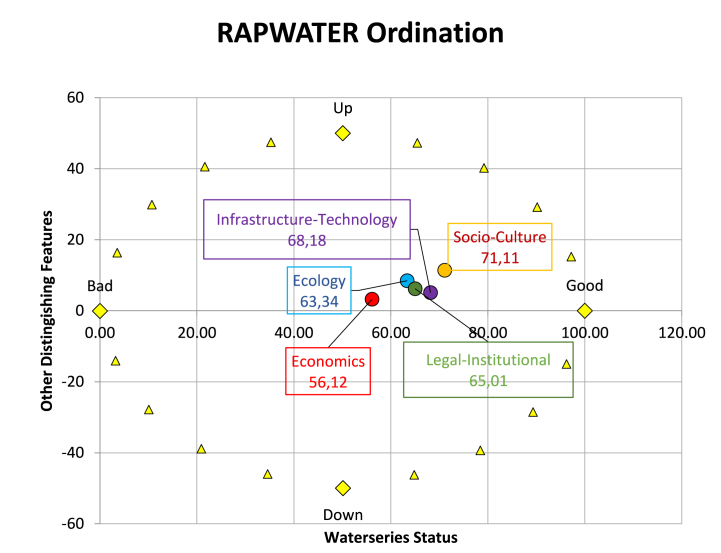

MDS analysis indicates Bali's sustainability dimension of all water civilizations is low. The ecology dimension has a sustainability score of 63.34%, the economics dimension has a sustainability score of 56.12%, the socio-cultural dimension has a sustainability score of 71.11%, the infrastructure-technology has a sustainability score of 65.01%, and the legal-institutional dimension has the sustainability score of 68.18%. All sustainability dimension scores of water civilization in Bali need improvement, particularly in ecology and economics dimensions (Fig. 3). This means the economics and ecology problems need prioritized attention. Respondents' responses show that water resources management is quite good, but the people who protect it cannot enjoy its benefits. This needs attention and improvement so that the people who protect the water resources, particularly the wells, can enjoy better benefits. Along with the rapid development in tourism, the use of resources for tourism should not be underestimated. The water users in Bali are mostly tourists, tourism developers, and investors who can be said to consume the most water resources [13].

Fig. 3.

The sustainability analysis of water resources management.

In general, enterprises in Bali that exploit nature for business have not actively supported the efforts to save Bali's natural and cultural richness. For instance, their attention in the form of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) for subak is not significant yet. The local government has helped the subak institution with a donation, but it is mostly used for physical development, such as the development of the subak hall does not directly affect the subak community members' needs. The water civilization rituals can be done quite well. Symbolically, the meaning needs to be analyzed and disseminated to the people so they can understand that their efforts through cultural and religious rituals are basically natural conservation efforts. From this understanding, the government and enterprises in Bali should be aware that the people have protected their land without ulterior motives, such as protecting subak and its culture that could attract tourists to Bali.

From a social structure perspective, awig-awig is a slice of paper with cultural power, but it means nothing when facing agrarian law. Each land use change only requires a notary and several witnesses, generally from governmental agencies. On the other hand, the irrigation system in Bali is managed by the subak community, so conflict of interest commonly happens, particularly when the enterprises shut down the water channel when performing land change use. Establishing green lines is a solution, but all parties need to consider the benefit to the landowners or farmers. An effort that could be made is to give free or discount tax to the farmers.

Subak system has a function to manage water and preserve sustainability characteristics based on traditional principles that integrate the environmental, natural, religious, and cultural components. Globalization and urbanization have made Balinese tradition, culture, and civilization economic assets. To ensure the people do not lose social control of the natural and cultural resources, by referring to the principles of Tri Hita Karana, there should be cooperative efforts to strengthen the religious values, good governance, and the economic aspects of the Balinese culture.

5.2. The leverage factors affecting sustainability

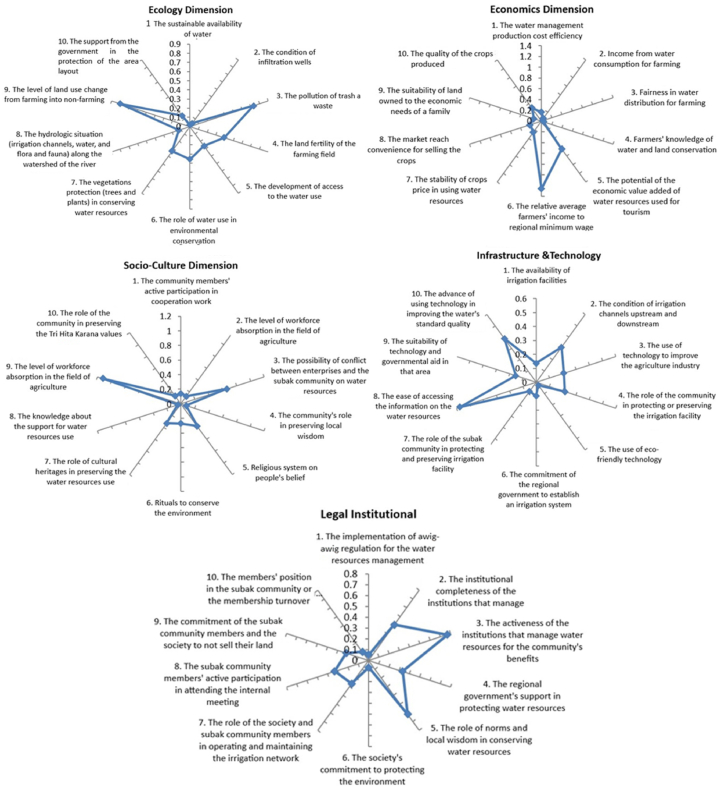

After performing sustainability analysis, the next step is to decide the affecting attributes using leverage analysis. The leverage analysis would measure the attributes that significantly affect the sustainability score so that improvement priorities can be set. The graphic of leverage analysis of each dimension is presented below.

The figure above shows several attributes strongly influencing each dimension's sustainability score (Fig. 4). Next, two attributes are chosen from each dimension with considerable influence, which would be used to decide the prioritized improvement. The attributes that influence the water civilization in Bali are: 1. The average farmers' salary is relatively small compared to the province minimum wage (Economic Dimension); 2. The potential of economic value added to the water resources use for tourism (Economic Dimension); 3. The high level of land use changes from farming to non-farming (Environmental Dimension); 4. The pollution of trash and waste (Environmental Dimension); 5. Workforce absorption (Socio-cultural Dimension); 6. The conflicts that potentially happen between enterprises and the subak communities (Socio-cultural Dimension); 7. The activeness of the institutions that manage the water resources for people's benefit (Legal-Institutional Dimension); 8. The ease in accessing the water resources (Technology-Infrastructure Dimension); 9. The roles of norms or local wisdom values in conserving the water resources (Legal-Institutional Dimension); 10. The advancement of technology to develop water's standard quality (Technology-Infrastructure Dimension). Those attributes above can be used for improvement priorities as an alternative strategy to improve the sustainability score of the water civilization in Bali so its sustainability can be well-protected.

Fig. 4.

Results of leverage analysis from each measured dimension (Ecological, Economical, Socio-Cultural, Infrastructure-Technological, and Legal-Institutional dimensions). Notice that some attributes in each dimension display higher scores than others. These attributes are the most significant leverage factors to achieve and maintain sustainability.

6. Conclusion

Conservation efforts performed by the people of Bali which prolong the age of the environment through the ecology manipulation of the built environment have been around since the pre-Hindu period. The efforts have been done through a belief system, people's socio-cultural system, and by glorifying the mountains as the center of natural power that give fertility. Water should be protected and sanctified to protect the sustainability of the hydrological cycle. The concept of kaja-kelod that puts the direction of kaja as something sacred means that mountains, as the life source of wells, must be protected. People need to protect the sustainability of the water stream from the river to the downstream. The worshipping sites built at the wells and the watershed areas are meant to protect the sustainability of water sanctity. This concept continues to be the soko guru of water management practiced by the ancient Balinese kings and the people today.

The inheritance of the Balinese people's water management tradition is generally weak in each dimension. The socio-cultural dimension score is relatively high, with a sustainability score of 71.11%. This shows that the culture of water resources management is still trusted by society to protect nature. However, the economy and ecology dimensions' score low, with the sustainability score of 56.12 and 63.34%, respectively, indicating the need for improvement in economic matters through the policy strategy. This coordinates each sustainable development dimension, so the water civilization is sustainable in the socio-cultural and other dimensions. The strategy policy is performed by fixing 10 affecting variables to improve the sustainability of the water resources management civilization in the regencies of Badung, Gianyar, and Tabanan.

The sustainable water resources management civilization is applied by improving the dimensions of Environment, Economics, and Socio-Culture through protecting the vegetation (trees and plants), solving trash and waste problems, fairly distributing the water for agriculture and domestic needs, and the improvement of environmental conservation efforts. The belief system embraced by the people is still the most essential part of society. Religious rituals, temples, and the ancestors' heritages still play important societal roles, particularly in natural conservation. However, the economic dimension is concerning. The occupational switch in society from agriculture to tourism needs special attention so it will not hamper environmental conservation.

Our study implies understanding how the built environment develops in harmony with nature based on centuries of experience. However, the challenge is to uncover the value behind an area's cultural heritage and customs. Thanks to the persistence of the Balinese people in their customs, information can be gathered and even confirmed with historical facts contained in archaeological remains and ancient inscriptions. Our study also challenges cultural heritage conservation in Bali, where ecological aspects must be considered. We understand that our study inevitably has limitations in its applicability. The area is still limited to four districts: Denpasar, Badung, Gianyar, and Tabanan. This area does not represent the entire Balinese community due to differences in demographics and physiography. However, this study can be replicated in other regions to strengthen our resilience to future water management sustainability challenges.

Funding statement

The research was funded by The National Center for Archaeological Research (PUSLIT ARKENAS in 2018–2020) and The National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN in 2022).

Data availability

No. Data will be made available on request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

I Made Geria: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Titi Surti Nastiti: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Retno Handini: Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Wawan Sujarwo: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Acwin Dwijendra: Data curation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Mohammad Ruly Fauzi: Data curation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Ni Putu Eka Juliawati: Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank all colleagues and researchers involved in this research project. We would like to thank to all people who helped us during the data collection, especially to all of our respondents and the local government in Bali for giving us support.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21248.

Contributor Information

I Made Geria, Email: madegeria0101@gmail.com.

Titi Surti Nastiti, Email: tsnastiti@yahoo.com.

Retno Handini, Email: retnohandinindandin@gmail.com.

Wawan Sujarwo, Email: wawan.sujarwo@brin.go.id.

Acwin Dwijendra, Email: acwin@unud.ac.id.

Mohammad Ruly Fauzi, Email: moha065@brin.go.id.

Ni Putu Eka Juliawati, Email: putuekajulia@gmail.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Soemarwoto O. Djambatan; Jakarta: 2004. Ekologi, Lingkungan Hidup dan Pembangunan. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gde Bagus A.A. Perkembangan peradaban di Kawasan Situs Tamblingan. Forum Arkeologi. 2013;26:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sutaba I.M. Evaluasi Hasil Penelitian Arkeologi, Pusat Penelitian Arkeologi Nasional. Ujungpandang; 1996. Masyarakat Megalitik di Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutaba I.M. Pascasarjana Universitas Hindu Indonesia; 2014. Tahta Batu Prasejarah Bali: Telaah Tentang Bentuk dan Fungsinya, Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ardika I.W., Srijaya I.W., Seriarsa I.W., Sumartika I.N., Bagus A.A.G., Rena I.G.M., Muliarsa I.W. Balai Pelestarian Peninggalan Purbakala (BP3) Bali; Denpasar: 2006. Pura Pegulingan, Tirtha Empul, dan Goa Gajah: Peninggalan Purbakala di Daerah Aliran Sungai Pakerisan dan Petanu, Gianyar. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stutterheim W.F. De Kirtya Liefrinck van der Tuuk; Singaraja (Bali): 1929. Oudheden Van Bali : Het Oude Rijk Van Pedjeng Tekst. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lansing J.S. Princeton University Press; New Jersey: 2007. Priests and Programmers, Technologies of Power in the Engineered Landscape of Bali. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lestari P.F.K., Windia W., Astiti N.W.S. Penerapan Tri Hita Karana untuk keberlanjutan sistem subak yang menjadi warisan budaya dunia: kasus subak wangaya betan, kecamatan Penebel, kabupaten tabanan. Jurnal Manajemen Agribisnis. 2015;3:22–33. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lorenzen R.P., Lorenzen S. Changing realities— perspectives on Balinese rice cultivation. Hum. Ecol. 2011;39:29–42. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41474582 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roth D. Environmental sustainability and legal plurality in irrigation: the Balinese subak. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2014;11:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2014.09.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sutawan N. Jurusan Sosial Ekonomi Pertanian Fakultas Pertanian Udayana (unpiblished); 2001. Eksistensi Subak di Bali: mampukah bertahan menghadapi berbagai tantangan, Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geria I.M., Sumardjo N., Sutjahjo S.H., Widiatmaka N., Kurniawan R. Subak sebagai benteng konservasi peradaban Bali. Amerta. 2019;37:39–54. doi: 10.24832/amt.v37i1.39-54. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cole S., Browne M. Tourism and water inequity in Bali: a social-ecological systems analysis. Hum. Ecol. 2015;43:439–450. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24762767 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fazey I., Fazey J.A., Salisbury J.G., Lindenmayer D.B., Dovers S. The nature and role of experiential knowledge for environmental conservation. Environ. Conserv. 2006;33:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S037689290600275X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petts J., Brooks C. Expert conceptualisations of the role of lay knowledge in environmental decisionmaking: challenges for deliberative democracy, environment and planning A. Econ. Space. 2006;38:1045–1059. doi: 10.1068/a37373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Innes J.E. Information in communicative planning. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 1998;64:52–63. doi: 10.1080/01944369808975956. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sillitoe P. vol. 12. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute; 2006. p. S119. (Ethnobiology and Applied Anthropology: Rapprochement of the Academic with the Practical). –S142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanderson S.K. Raja Grafindo Persada; Jakarta: 2000. Makro Sosiologi, Sebuah Pendekatan Terhadap Realita Sosial. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faber N., Jorna R., Engelen J.V. The sustainability of “sustainability” - a study into the conceptual foundations of the notion of “sustainability. J. Environ. Assess. Pol. Manag. 2005;7:1–33. doi: 10.1142/S1464333205001955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fauzi A. Gramedia Pustaka Utama; Jakarta: 2019. Teknik Analisis Keberlanjutan. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson R.S. In: Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Michalos A.C., editor. Springer Netherlands; Dordrecht: 2014. Purposive sampling; pp. 5243–5245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandeville G.K., Roscoe J.T. Journal of the American Statistical Association; 1971. Fundamental Research Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences; p. 224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Louangrath P. 2014. Sample Size Determination for Non-finite Population. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Memon M.A., Ting H., Cheah J.-H., Thurasamy R., Chuah F., Cham T.H. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling. 2020. Sample size for survey research: review and recommendations. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kavanagh P., Pitcher T.J. Implementing Microsoft Excel Software for Rapfish: a Technique for the Rapid Appraisal of Fisheries Status. University of British Columbia; Vancouver: 2004. The fisheries centre. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Budiharsono S. Pradnya Paramita; Jakarta: 2005. Teknis Analisis Pembangunan Wilayah Pesisir dan Lautan. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fauzi A. Gramedia Pustaka Utama; Jakarta: 2004. Ekonomi Sumber Daya Alam dan Lingkungan: Teori dan Aplikasi. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Satty T.L. Pustaka Binaman Pressindo; Jakarta: 1993. Pengambilan Keputusan Bagi Para Pemimpin, Proses Hierarki Analitik Untuk Pengambilan Keputusan Dalam Situasi Kompleks, PT. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Susilo S.B. Institut Pertanian Bogor (unpublished); 2003. Keberlanjutan Pembangunan Pulau-Pulau Kecil: Studi Kasus Kelurahan Pulau Panggang dan Pulau Pari Kepulauan Seribu DKI Jakarta, Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pearce D., Turner R.K. John Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 1990. Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goris R. Masa Baru; Bandung: 1954. Prasasti Bali I. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goris R. Masa Baru; Bandung: 1954. Prasasti Bali II. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Callenfels P.V.S., Epigraphia Balica I. Verhandelingen Koninklijk Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten En Wetenschappen. 1926;LXVI:70. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ginarsa K. Prasasti baru Raja Marakata, bahasa dan budaya. Majalah Ilmiah Populer. 1961;IX:3–17. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Budiastra P. Direktorat Museum Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan; Denpasar: 1980. Prasasti Banjar Celepik-Tijan Klungkung, Museum Bali. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Budiastra P. Museum Bali, Direktorat Museum Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan; Denpasar: 1979. Prasasti Pandak Badung Tabanan. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jameson J.-H., Jr. In: Public Archaeology. Merriman N., editor. Routledge; New York: 2004. Public archaeology in the United States; pp. 21–58. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rist S., Dahdouh-Guebas F. Ethnosciences––A step towards the integration of scientific and indigenous forms of knowledge in the management of natural resources for the future. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2006;8:467–493. doi: 10.1007/s10668-006-9050-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berkes F. From community-based resource management to complex systems: the scale issue and marine commons. Ecol. Soc. 2006;11:1–16. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26267815 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cumming G.S., Cumming D.H.M., Redman C.L. Scale mismatches in social-ecological systems: causes, consequences, and solutions. Ecol. Soc. 2006;11:1–21. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26267802 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fisher B., Kulindwa K., Mwanyoka I., Turner R.K., Burgess N.D. Common pool resource management and PES: lessons and constraints for water PES in Tanzania. Ecol. Econ. 2010;69:1253–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paramadhyaksa I.N.W. Makna-makna figur Naga dalam budaya tradisional Bali. Forum Arkeologi. 2011;XXIV:263–279. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor P.W. Princeton University Press; New Jersey: 1986. Respect for Nature: A Theory of Environmental Ethics. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patchett J.M., Wilhelm G.S. Conservation Research Institute Essays; 2008. The Ecology and Culture of Water; pp. 1–19.https://conservationresearchinstitute.org/files/culture/ecology_and_culture_of_water.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wiana I.K. In: Dialog Ajeg Bali: Perspektof Pengamalan Agama Hindu. Titib I.M., editor. Surabaya; Paramita: 2005. Ajeg Bali adalah tegaknya kebudayaan Hindu di Bali; pp. 141–184. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nastiti T.S., Handini R., Mahardian D., Nisrina M., Satrio, Dusita T.D., Prihatmoko H., Rema I.N., Wibowo U.P., Gede I.D.K., Riva’i M., As-Syakur A.R. Pusat Penelitian Arkeologi Nasional (tidak diterbitkan); Jakarta: 2020. Peradaban Bali Dalam Pengelolaan Sumber Daya Air Tahap II. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Geria I.M. In: Merajut Kearifan Lokal Membangun Karakter Bangsa. Sutaba I.M., editor. Balai Arkeologi Denpasar, Kementerian Pariwisata dan Ekonomi Kreatif; Denpasar: 2012. Penguatan jatidiri dalam perspektif aktualisasi arkeologi. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suripin S. Penerbit Andi; Yogyakarta: 2004. Sistem Drainase Perkotaan Yang Berkelanjutan. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Asdak C. Gadjah Mada University Press; Yogyakarta: 2007. Hidrologi dan Pengelolaan Daerah Aliran Sungai. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arifin K. Faculty of Letters, University of Indonesia; 1983. Waduk dan Kanal di Pusat Kerajaan Majapahit Trowulan Jawa Timur, Undergraduate Thesis. (unpublished thesis) [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reid A. Yayasan Obor Indonesia; Jakarta: 2011. Asia Tenggara dalam Kurun Niaga 1450-1680 (Jilid 1: Tanah di Bawah Angin) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No. Data will be made available on request.