Graphical abstract

Keywords: Natural deep eutectic solvents, Gardenia fruits, Ultrasound-assisted extraction, Modified multi-index synthetic weighted scoring method, Molecular networking, Low-density lipoprotein oxidation

Highlights

-

•

Crocin and geniposide, two main characteristic ingredients in gardenia fruits, were simultaneously extracted by natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES) coupled with probe-type ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE).

-

•

The optimization of simultaneous extraction conditions was performed by orthogonal experiment design coupled with a modified multi-index synthetic weighted scoring method.

-

•

Thirty-three compounds in NADES extract were identified by LC-Q-TOF-MS2 combined with a feature-based molecular networking (FBMN) workflow.

-

•

The inhibitory effects of crocin and geniposide on Cu2+-induced LDL oxidation were evaluated by analyzing the conjugated dienes generation process via the four-parameter logistic regression model.

Abstract

The simultaneous extraction of crocin and geniposide from gardenia fruits (Gardenia jasminoides Ellis) was performed by integrating natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES) and ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE). Among the eight kinds of NADES screened, choline chloride-1,2-propylene glycol was the most suitable extractant. The probe-type ultrasound-assisted NADES extraction system (pr-UAE-NADES) demonstrated higher extraction efficiency compared with plate-type ultrasound-assisted NADES extraction system (pl-UAE-NADES). Orthogonal experimental design and a modified multi-index synthetic weighted scoring method were adopted to optimize pr-UAE-NADES extraction process. The optimal extraction conditions that had a maximum synthetic weighted score of 29.46 were determined to be 25 °C for extraction temperature, 600 W for ultrasonic power, 20 min for extraction time, and 25% (w/w) for water content in NADES, leading to the maximum yields (7.39 ± 0.20 mg/g and 57.99 ± 0.91 mg/g, respectively) of crocin and geniposide. Thirty-three compounds including iridoids, carotenoids, phenolic acids, flavonoids, and triterpenes in the NADES extract were identified by LC-Q-TOF-MS2 coupled with a feature-based molecular networking workflow. The kinetics evaluation of the conjugated dienes generation on Cu2+-induced low density lipoprotein (LDL) oxidation via the four-parameter logistic regression model showed that crocin increased the lag time of LDL oxidation in a concentration-dependent manner (15 μg/mL, 30 μg/mL, 45 μg/mL) by 12.66%, 35.44%, and 73.42%, respectively. The quantitative determination for fluorescence properties alteration of the apolipoprotein B-100 exhibited that crocin effectively inhibited the fluorescence quenching of tryptophan residues and the modification of lysine residues caused by reactive aldehydes and malondialdehydes. The pr-UAE-NADES showed significant efficiency toward the simultaneous extraction of crocin and geniposide from gardenia fruits. And this study demonstrates the potential utility of gardenia fruits in developing anti-atherogenic functional food.

1. Introduction

Gardenia jasminoides Ellis (G. jasminoides) is a popular shrub in the Rubiaceae family, which is mainly cultivated in the tropical and subtropical regions including China, Japan, Korea, India, and North America [1]. Gardenia fruit, the desiccative ripe fruit of G. jasminoides, is widely used not only as a raw material of natural dye but also as a traditional Chinese herbal medicine for antiphlogistic, analgesic, antipyretic, and anti-atherogenic purposes [1]. It has also been announced as the first batch of dual-purpose plant resources used for food and medical functions in China [2]. However, the majority of gardenia fruits are solely utilized as herbal medicine in China, and a large amount of stagnant gardenia fruits need to be further processed for effective valorization [2].

Iridoid glycosides and crocetin derivatives are the main characteristic ingredients in gardenia fruits, primarily consisting of geniposide and crocin, respectively [1]. The simultaneous extraction of geniposide and crocin from gardenia fruits could be accessible using a tailor extractant [2]. To date, the optimization of the simultaneous extraction process for these two compounds from gardenia fruits has been mainly carried out by the average weighting method that converts the multi-index test problem into a single-index test problem and then uses a single-index analysis approach to comprehensively select and optimize the scheme [2]. But the distinctions and significances of indicators are disregarded in this method [3]. Thus, the optimization of extraction conditions produces a more favorable outcome for components with higher content. In comparison, barely satisfactory yields of components with lower content are probably obtained in such conditions. A more scientific evaluation strategy for the multi-index tests, namely the synthetic weighted scoring method, can effectively incorporate objective information from test results and subjective cognition on the index importance [4]. This method has been successfully applied to explore the effects of the process conditions on the results of multi-index experiments [4]. However, there have been few investigations into the use of this method to optimize the extraction procedure of the characteristic components from gardenia fruits.

At present, the simultaneous extraction of geniposide and crocin from gardenia fruits is mainly carried out by conventional organic solvents such as ethanol, methanol, or acetone, which will have a detrimental influence on the environment and raise health concerns [5]. Recently, a new green alternative to traditional solvents known as natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES), offering many advantages such as outstanding solvation capacity, biocompatibility, low vapor, sustainability, low toxicity, and ease of production, has been increasingly involved in the extractions of various bioactive compounds including polyphenols, anthocyanins, and carotenoids [6]. NADES are synthesized by mixing primary metabolites or bio-renewable materials and have a lower melting point than their components, in which one of the components serves as a hydrogen bond donor (HBD) (e.g., amino acids, carboxylic acids, sugars) and the other as a hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) (e.g., quaternary ammonium salt) [7]. Due to the compositions, NADES typically have a high viscosity, causing the mass transporting capacity to decrease. Nevertheless, this issue can be effectively avoided by adding appropriate amount of water to tailor the physicochemical properties of NADES and integrating NADES with ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) [8].

Among many extraction techniques to employ NADES as an extractant, UAE can provide improved dispersion of extraction solvent and mass transfer efficiency by inducing cavitation effects, which is suitable for NADES that possess higher viscosity compared with conventional solvents [9]. Meanwhile, UAE satisfies the demands of sustainability and environmental friendliness due to its property of minimizing solvent usage, processing time, and energy consumption [10]. According to the ultrasonic transmission equipment used, the UAE systems are mainly divided into two categories: probe-type ultrasound-assisted extraction (pr-UAE) system and plate-type ultrasound-assisted extraction (pl-UAE) system (ultrasonic cleaner, etc.). In the pr-UAE system, the ultrasound is collectively radiated into the samples by a metallic probe, which results in high energy transfer efficiency and assists in enhancing the cavitation effects [11]. In the pl-UAE system, the ultrasound is transmitted to the medium by a metal plate connected to the ultrasonic transducer. Contrary to the pr-UAE system, it always obtains a stable ultrasonic power but has a lower ultrasonic energy density [10]. The effectiveness of NADES in combination with both UAE systems for extracting natural products and valorizing by-products of the food sector has been demonstrated by many researches. Zhao et al. [9] combined NADES with the pl-UAE system, and it was showed that this approach could be a green and alternative choice for the recovery of paeoniflorin and galloyl paeoniflorin from Radix Paeoniae Rubra. Huang et al. [12] integrated NADES and pr-UAE for the effective extraction of crocins from gardenia fruits and investigated the effect of UAE conditions on the extraction of crocins through a single-factor approach. However, it is still unknown which ultrasound system is more suitable to combine with NADES for the simultaneous extraction of geniposide and crocin from gardenia fruits. Moreover, it is necessary to further optimize the extraction conditions via experimental design strategies.

Human plasma low density lipoprotein (LDL) is a heterogeneous molecule composed primarily of phospholipids, cholesterol, cholesterol esters, and the apolipoprotein (apo) B-100, as well as the predominant cholesterol carrier in the blood [13]. The oxidative modification of LDL appears to play a significant role in the etiology of atherosclerosis [14]. Multiple studies have shown that the oxidation of LDL could be restricted by various natural active substances such as polyphenols [14], and active peptides [15], and others. Besides, the methanol extract of gardenia fruits exhibited DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging activities in previous study [16]. However, the inhibitory effects of geniposide and crocin from gardenia fruits on LDL oxidation are unknown by now.

Therefore, the simultaneous extraction of crocin and geniposide from gardenia fruits was performed by integrating NADES and UAE in the present study. The following contents were investigated: (1) the synergistic extraction effects of NADES combined with pr-UAE system were compared with those of NADES combined with pl-UAE system, and the extraction conditions were optimized via orthogonal experimental design and a modified multi-index synthetic weighted scoring method; (2) the characteristic components in gardenia fruits were preliminary separated and enriched by AB-8 macroporous resin, then the LC-Q-TOF/MS2 and the feature-based molecular networking (FBMN) were conducted to identify these components of the NADES extract after purified; (3) the inhibition effects of crocin and geniposide on LDL oxidation were evaluated by the kinetics curves of the conjugated dienes (CD) generation using the four-parameter logistic (4PL) regression model and by the alterations of apo B-100 fluorescence properties. This study provided new knowledge for the deep processing of gardenia fruits and demonstrated the potential of developing novel anti-atherogenic functional food based on gardenia fruits.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and adsorbent

Compounds for NADES preparation, HPLC grade of crocin, geniposide, formic acid, and other analytical-grade reagents were all purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). AB-8 macroporous resin was purchased from Xi’an Sunresin New Materials Co., Ltd. (Shaanxi, China).

2.2. Preparation of samples

Desiccated gardenia fruits were obtained from Danxia Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Jiangxi, China). These fruits were pulverized into fine powders and passed through a 40-mesh sieve. The powders were then stored in a dry shelter for further investigations.

2.3. Preparation of NADES

The NADES were prepared through a heating and stirring method as described by Airouyuwa et al. [7] with minor modifications. The components of NADES were shown in Table 1. Briefly, HBA and HBD were mixed in sealed flasks in corresponding ratios with the addition of calculated amounts (35%, w/w) of deionized water. Then, the mixtures were heated at 90 °C with magnetic agitation until homogeneous and transparent liquids were produced. The prepared NADES were stored at 25 °C in the dark before use.

Table 1.

Abbreviations, chemical compositions, and molar ratios of NADES (35%, w/w).

| NADES | Hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) | Hydrogen bond donor (HBD) | Molar ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| CC-PG | Choline chloride | 1,2-Propylene glycol | 1:2 |

| CC-GL | Choline chloride | Glycerol | 1:2 |

| CC-TA | Choline chloride | L-Tartaric acid | 2:1 |

| CC-MA | Choline chloride | D, L-Malic acid | 2:1 |

| CC-GLU | Choline chloride | Glucose | 1:1 |

| CC-FRU | Choline chloride | Fructose | 1:1 |

| BE-PG | Betaine | 1,2-Propylene glycol | 1:2 |

| BE-TA | Betaine | L-Tartaric acid | 2:1 |

2.4. Characterization of NADES by Fourier transforms infrared spectra (FT-IR)

To characterize the structural features of the choline chloride-based NADES and the betaine-based NADES, two widely used types of the NADES, namely CC-PG and BE-PG, and their components were analyzed by Vertex 70 FT-IR Spectrophotometer (Bruker, Germany). Samples were embedded in thin potassium bromide pellets (1:200 w/w), measuring in the scanning range from 400 to 4000 cm−1 at a resolution of 4 cm−1.

2.5. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of NADES extracts

The samples were quantitatively analyzed by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) equipped with a C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm i.d., 5 µm particle size) according to the method previously described by Shang et al. [2] with modifications. The mobile phase consisted of methanol (A)-water with 0.1% formic acid solution (B) in a linear gradient program as follows: 0–5 min, 20–40% A; 5–15 min, 40–70% A; 15–27 min, 70–76% A at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The detection wavelengths were set at 240, 315, and 440 nm. The column temperature was held at 30 °C and the injection volume was 20 μL. Additionally, the R2 for standard curves of both crocin and geniposide were higher than 0.999, with the R.S.D. values of the slopes lower than 1.5%.

2.6. Screening of NADES

The NADES screening was conducted by conventional heating extraction (CHE) according to the method described by Huang et al. [12] with modifications. Briefly, 1.0 g of dried gardenia fruit powder was mixed with 40 mL of solvent. The mixture was heated to 50 °C and agitated at 120 r/min for 2 h. After centrifugation at 10,000 g for 20 min, the suspension was separated and the residue was re-extracted twice. The obtained supernatants were combined, adjusted the volume to 250 mL with deionized water, and then stored at 4 °C for HPLC analysis.

2.7. Comparisons of the extraction effects obtained by pl-UAE and pr-UAE combined with NADES

Based on the screening of NADES, the selected NADES was applied to combine with the UAE. In brief, the selected NADES with different addition of water (0%, 25%, 40%, w/w) were prepared separately. Then sample powders were mixed with NADES at various solid-to-solvent ratios (SS ratios) of 1:20, 1:30, and 1:40 (g/mL). The pl-UAE and the pr-UAE were performed on an ultrasonic bath and a cell grinder with an ultrasonic probe (6 mm diameter), respectively (Ningbo Scientz Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China), working at the same conditions (at 40 °C for 20 min, ultrasonic power of 420 W, and frequency of 20 kHz).

2.8. The optimization of Pr-UAE assisted NADES extraction conditions

2.8.1. Single-factor experiments

According to the results of the Section 2.7, the pr-UAE-NADES system was selected for extraction and parameter optimization. Single-factor experiments were conducted to study the extraction effects of four factors, including extraction temperatures (15, 25, 35 45, 55 °C), ultrasonic powers (200, 300, 400, 500, 600 W), extraction times (10, 15, 20, 25, 30 min), and water contents in NADES solutions (25, 30, 35, 40, 45%, w/w) on the yields of crocin and geniposide. The starting parameters of pr-UAE were set at 25 °C for 15 min, 400 W, 35% (w/w) water content in NADES, and 1:40 (g/mL) SS ratio.

2.8.2. Orthogonal experiments

An orthogonal experimental L9 (34) was designed based on the results of the single-factor experiments to optimize processing condition parameters. For the factors and levels following the L9 (34) orthogonal array design, kindly refer to Table 2.

Table 2.

Factors and levels of the orthogonal design L9 (34) and experimental results.

| No. | Factors (levels) |

Extraction yields |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A)Temperature (°C) | (B)Ultrasonic power (W) | (C)Extraction time (min) | (D)Water content (%) |

Y1 (mg/g) |

Y2 (mg/g) |

|

| 1 | 25(1) | 200(1) | 5(1) | 25(1) | 6.59 ± 0.10 | 43.34 ± 0.61 |

| 2 | 25(1) | 400(2) | 20(3) | 35(2) | 6.33 ± 0.07 | 45.69 ± 0.38 |

| 3 | 25(1) | 600(3) | 10(2) | 45(3) | 7.01 ± 0.03 | 55.53 ± 0.54 |

| 4 | 35(2) | 200(1) | 20(3) | 45(3) | 6.29 ± 0.07 | 43.66 ± 0.26 |

| 5 | 35(2) | 400(2) | 10(2) | 25(1) | 6.83 ± 0.08 | 51.93 ± 0.58 |

| 6 | 35(2) | 600(3) | 5(1) | 35(2) | 6.38 ± 0.07 | 49.86 ± 0.56 |

| 7 | 45(3) | 200(1) | 10(2) | 35(2) | 6.28 ± 0.11 | 47.16 ± 0.76 |

| 8 | 45(3) | 400(2) | 5(1) | 45(3) | 5.94 ± 0.03 | 43.61 ± 0.52 |

| 9 | 45(3) | 600(3) | 20(3) | 25(1) | 6.41 ± 0.05 | 49.77 ± 0.61 |

Y1 means the extraction yields of crocin, and Y2 means the extraction yields of geniposide.

2.8.3. Modified multi-index synthetic weighted scoring method

To determine the optimization of parameter combination, a modified multi-index synthetic weighted scoring method synthesizing range analysis and analysis of variance was designed and carried out, according to the method described by Feng et al. [4] with modifications. The procedure below outlined the specific steps.

In these multi-index orthogonal experiments, there were four factors marked as I = {1, 2, 3, 4}, and nine combinations marked as J = {1, 2, …, 9}. Two evaluation indexes were marked as K = {1, 2}, where k1 referred to the extraction yield of crocin, and k2 referred to the extraction yield of geniposide. The corresponding experimental results were yjk (j = 1, 2, …, 9; k = 1, 2) which constituted an assessment matrix Y = (yjk)9×2.

Z = (zjk)9×2 was the standardized assessment matrix, where the zjk was calculated as Eq. (1) to unify the order of magnitude and dimension of indexes.

| (1) |

Due to the variety of the character of each index, not all indexes are equally significant. To ensure a valid assessment, both the subjective cognition of the index importance and the objective test results were taken into account in this method.

The matrix of subjective weight was α = [0.5, 0.5] T. The matrix of objective weight was marked as β = [β1, β2]T. From the entropy assessment method, the β was calculated as Eqs. (2), (3), and (4).

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Notes, when pjk = 0, pjklnpjk = 0, the matrix of objective weight was calculated as β = [0.55, 0.45].

To accomplish the integration between subjective preference and objective information, the optimal decision model was designed as Eq. (5).

| (5) |

Reflecting preferences for both subjective and objective weights, μ (0 ≤ μ ≤ 1) was the inclination coefficient and was given a value of μ = 0.5. Eq. (5) has a particular solution that is written as Eq. (6).

| (6) |

The synthetic weights were obtained as ω = [0.53, 0.47] T.

The contribution ratios, rhoik, and rhoek reflexed the impact of factor i and error on the total fluctuation of index k and were calculated using Eqs. (7), (8).

| (7) |

| (8) |

DFik and SSik are the degrees of freedom and the sum of squares of factor i, respectively. DFTk is the sum of DFik, and SSTk is the sum of SSik. MSek is the mean square of error. Only if rhoik is greater than rhoek, the factor is considered to generate a significant impact on the indicator. For complete details of the data, kindly refer to Table S1 in Supplementary material.

The level r (r = 1, 2, 3) indicator of factor i on index k was defined as δikr, which was an operator to convert the level to values. The δikr of the optimal level was assigned as 3, and the other two levels were designated as 2 and 1 in sequence.

The synthetic weighted score of the factor i with the level r for all indexes was calculated using Eqs. (9), (10).

| (9) |

| (10) |

The synthetic weighted score of each combination was marked as Sm, where m = {1, 2, …, 81}. For the calculation results of sir and Sm, kindly refer to Tables S2 and S3 in Supplementary material.

The optimal processing parameters were verified by reanalyzing the two indicators under the optimal combination of the four factors.

2.9. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of gardenia fruit powders

To better understand the effects of different extraction methods (CHE, pl-UAE, pr-UAE) on extraction efficiency, SEM was used to examine the microscopic structures of gardenia fruit powders both before and after extraction. Briefly, the samples were rinsed with ethanol and deionized water and subsequently were dehydrated by a dryer. The desiccated samples were affixed with gold, then observed under an SEM analyzer (VEGA Ⅱ LSU, Tescan, Czech Republic) at an accelerating voltage of 20.0 kV. The magnification was set as 1000×.

2.10. Recoveries of crocin and geniposide using macroporous resin

The recoveries of crocin and geniposide were performed according to the method described by Wang et al. [17] with modifications. In brief, after pretreatment, AB-8 macroporous resin was loaded into a glass column (50 cm × 55 mm i.d.). The bed volume (BV) of the wet-packed resin was 110 mL. The crude extracts were diluted with deionized water and pumped into the resin column at a flow rate of 2 BV/h. After the adsorption equilibrium was reached, the column was sequentially eluted with water, 30%, and 80% ethanol at a flow rate of 4 BV/h. The eluents of 30% and 80% ethanol were collected as two fractions (G1 and G2) and concentrated by a rotary evaporator to remove the ethanol followed by lyophilizing for HPLC and LC/MS2 analyses.

2.11. Integration of LC-Q-TOF/MS2 analysis with molecular networking (MN) workflow

2.11.1. LC-Q-TOF/MS2 analysis

The identification of G1 and G2 was carried out using an Agilent 6545 LC-Q-TOF/MS2 system (Agilent, USA) with a C18 column (100 mm × 3.0 mm i.d., 2.7 µm particle size). Briefly, the gradient elution program consisting of two mobile phase solvents, methanol (A) and 0.1% (v/v) of formic acid in ultrapure water (B) with a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min was detailed as follows: 0–1 min, 20–40% A; 1–11 min, 40–70% A; 11–21 min, 70–100% (slope 1.0). The MS with negative ion mode was conducted as follows: scan range, m/z 100–1700; capillary voltage, − 3.5 kV; desolvation gas temperature, 350 °C; desolvation gas flow rate, 11 L/min. The collision energies were set at 15 eV for low energy and 35 eV for high energy.

2.11.2. Molecular networking (MN) analysis

MN, which has emerged as a crucial bioinformatics tool for visualizing and annotating non-targeted mass spectrometry data, goes beyond spectral matching versus reference spectra, by aligning experimental spectra against one another and linking related molecules together based on their spectral similarity. The FBMN, an improved method based on classic MN, accepts the output of feature detection and alignment tools (such as MZmine, MS-DIAL, etc.), making them directly interoperable with tools for annotation and the whole analytic pipeline [18]. According to the method described by Jouaneh et al. [19] with modifications, the analysis procedure was generalized as follows.

Raw LC-MS/MS data were converted to the.mzXML format using the ProteoWizard tool MSConvertGUI (version 3.0.22317-1e024d4, Vanderbilt University, USA) [20]. The feature-based molecular networking on the GNPS website (http://gnps.ucsd.edu) was established by MZmine workflow (MZmine 2.53 program) [21], [22]. The MS data processing workflow consisted of raw data file import, peak detection, building chromatogram using the ADAP Chromatogram Builder Module [23], chromatogram deconvolve, peak list deisotoping, feature alignment, peak list filter, and processed data file export. For the complete MZmine parameter of the workflow, kindly refer to Supplementary material (Section 1.1).

Processed files were uploaded to the GNPS website and a molecular network was created with the FBMN workflow (https://ccms-ucsd.github.io/GNPSDocumentation/featurebasedmolecularnetworking/) [24]. To visualize the data, the output was imported into Cytoscape version 3.6.1 [25]. For the complete details of this method, kindly refer to Supplementary material (Section 1.2).

2.12. LDL oxidation assays

2.12.1. Isolation of LDL

The isolation of LDL was adopted from the protocol of Papadea et al. with modifications [26]. The precipitation buffer was made up of 64 mM trisodium citrate adjusted to pH 5.04 with 5 N HCl and included 50 U/mL heparin sodium (185 USP unit/mg). Plasma samples were mixed with the precipitation reagent (1:10, v/v) and then centrifugated at 5, 000 g for 10 min at 4 °C to precipitate the insoluble LDL. The LDL precipitate was washed with 64 mM citrate buffer (pH 5.11) followed by centrifugation. The LDL pellets were resuspended in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer saline (pH 7.40) with 0.9 percent sodium chloride and were extensively dialyzed against phosphate buffer saline for 24 h at 4 °C. The isolated LDL was charged with nitrogen and stored at −20 °C for less than two weeks. The LDL concentration was determined according to the Lowry protein assay [27] with modifications.

2.12.2. Conjugated dienes (CD) evaluation

According to the method described by Fillería et al. [15] with modifications, the LDL oxidation incubation protocol followed: 196 μL LDL (332 μg/mL), 2 μL sample or buffer (control), 2 μL 1 mM CuSO4 were mixed and incubated at 37 °C for 7 h with agitation. For background correction, the blanks (devoid of LDL and CuSO4) were run for each sample. During the incubation period, CD was monitored spectrophotometrically by SpectraMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, USA) via reading the absorbance at 234 nm.

The inhibition evaluation of samples on LDL oxidation was conducted by the 4PL regression model, a sigmoidal dose–response (variable slope) model, as described by Eq. (11) that plotted ΔAbs (y) as a function of the incubation time (x).

| (11) |

Where X50 is the time at which ΔAbs = 50% ΔAmax and S is the Hill slope that is corresponding to the maximum slope on the propagation phase of lipid peroxidation, namely propagation rate.

The capacity of samples to suspend the reaction chains during the propagation phase was indicated as Protection % and calculated as Eq. (12) [28].

| (12) |

Where the Se and S0 are the slopes (S) obtained in the presence and the absence of the samples, separately.

2.12.3. Fluorescence evaluation

According to the method described by Wani et al. [29] with modifications, fluorescence intensities (Ex 350 nm, Em 400–550 nm, and Ex 390 nm, Em 400–550 nm) were read by F-7000 spectrofluorometer (Hitachi, Japan) after incubating 18 h at 37 °C to evaluate the interaction between lipid peroxidation products and lysine residues, while fluorescence intensities (Ex 280 nm, Em 300–450 nm) was recorded to assess the modification of tryptophan residues by lipid peroxidation products.

2.13. Statistical analysis

The experiments were carried out in triplicate. All the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of independent experiments. The comparisons of data between groups were done by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey post-hoc test for intergroup comparisons. Differences were regarded as statistically significant at P < 0.01.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. FT-IR characterization of NADES and selection of suitable solvent for extraction

The term “deep eutectic solvents (DES)” refers to mixtures of two or more compounds for which the eutectic point temperature presents significant negative deviations from that of an ideal liquid mixture [6]. When the DES consist of primary metabolites, it is so-called NADES. The charge delocalization occurring in the generation of intermolecular hydrogen bonds between the components of DES is predominantly responsible for the decrease in the melting point of the mixture relative to those of the raw ingredients [5]. It follows that the formation of hydrogen bonds between the HBD and HBA is crucial for the synthesis of DES/NADES. Choline chloride (CC) is the most commonly utilized HBA for the preparation of NADES due to its low cost, biocompatibility, and low toxicity [6]. Possessing structure similarity to CC, betaine (BE), namely trimethylglycine, which is a naturally occurring amino acid listed as the prevalent ingredient used in cosmetic products by the European Commission, has also been reported as an outstanding HBA for producing NADES recently [30]. Chemical structures of CC and BE were presented in Fig. 1b. To compare the differences in structural features between the CC-based NADES and the BE-based NADES, particularly the differences in the generation of hydrogen bonds during the formation of deep eutectic mixtures, the representative CC-PG, BE-PG, and their components were analyzed by FT-IR (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

FT-IR spectra of CC-PG, BE-PG, and their constituents (a), chemical structures of CC and BE (b), the effect of NADES types on crocin yields (c) and geniposide yields (d). The different letters show significant differences between groups (P < 0.01) by using Tukey’s test.

The absorbance peaks of some characteristic groups of these substances can be enumerated as follows: υO-H 3650–3100 cm−1, υC-H 3100–2800 cm−1, δC-H 1490–1350 cm−1, υC=O 1810–1690 cm−1, υC-O 1150–1000 cm−1, υsCOO− 1410–1380 cm−1, υasCOO− 1610–1550 cm−1, υC-N 960–930 cm−1 [7], [30], [31]. The broad absorption peak around 3300 cm−1 in pure components spectrums indicated the presence of intermolecular interactions [31]. Generally, the corresponding spectral bands will shift in the direction of the lower wavenumber as a result of the formation of intermolecular hydrogen bonds. [32]. Comparing the individual NADES components with the synthesized NADES mixtures, it was observed that the absorption peaks of υO-H, υC-H, υC-O, and υC=O both occurred to a redshift. Interestingly, a blueshift appeared in the peaks of υC-N in both CC-PG and BE-PG spectra, the same phenomenon was observed by Bener et al. [31]. This was because the hydrogen atom in the methyl of PG and the carbon atom in the 2-methylene of CC formed a C–H--C hydrogen bond [33]. From this, it could be assumed that the formation of the hydrogen bond triggered the electron cloud on C-H of methyl in PG to bias towards C-N of CC, increasing the C-N stretching vibration frequency, and ultimately leading to a blue shift of the absorption peak. It might be presumed to encounter a similar scenario in BE-PG.

The efficacy of an extractant is dependent on its dissolution properties [5]. NADES have the competencies of donating and accepting protons and electrons, which gives them the ability to establish a hydrogen bond with the target compounds, therefore promoting the dissolution process [7]. A series of NADES and conventional solvents (such as water, and 60% ethanol) were compared to select the best NADES for the extraction of crocin and geniposide from the gardenia fruit. As shown in Fig. 1c, the yields of crocin were found in the descending order of CC-PG ≈ 60% Ethanol > BE-PG > CC-FRU > CC-GLU ≈ CC-GL > CC-MA > BE-TA > CC-TA ≈ Water. Meanwhile, as displayed in Fig. 1d, the yields of geniposide were observed in descending order of CC-PG ≈ 60% Ethanol > BE-PG ≈ CC-MA > Water > CC-GL ≈ CC-TA ≈ BE-TA > CC-FRU ≈ CC-GLU. The highest crocin and geniposide yields (5.35 ± 0.25 mg/g and 44.38 ± 1.47 mg/g, respectively) were both obtained by CC-PG, and CC-PG was thus further utilized in the optimization procedure.

3.2. Synergistic extraction effects of integrating various UAE systems with NADES

The UAE coupled with NADES is recognized as an effective green technique for the extraction of bioactive compounds. The ultrasonics effects, being responsible for the enhancement of solid–liquid extraction performances, can be summarized as follows: (1) Improved accessibility to cells structures, owing to the intense temperature and pressure generated during the bubbles collapse that leads to the damage of cells walls and thinning of membranes layers; (2) Promoted diffusion of the solvents into the matrices, due to the generation of pores into membranes which further enlarged by hydration and swelling of the matrices; (3) Enhanced solutes diffusion, because of microscopic turbulence, shear forces, and inter-particle collision resulting from the implosion of cavitation bubbles; (4) Increased surface areas of the matrices as a result of shock waves and microjets directed towards the matrix surface [10]. The UAE systems used for collaboration with NADES could be mainly divided into the pl-UAE and the pr-UAE, depending on the ultrasonic transmission device used [9], [12]. To evaluate the synergistic extraction effect of UAE and NADES in the simultaneous extraction of crocin and geniposide from gardenia fruits, a comparison study was performed between pl-UAE and pr-UAE coupled with NADES (CC-PG).

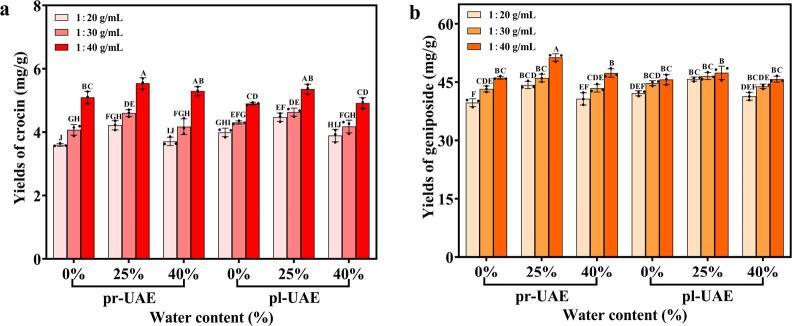

As presented in Fig. 2a & b, the yields of both crocin and geniposide gradually increased with the raises of SS ratios in both UAE systems. The possible reason for this phenomenon should be that the addition of extractants increased the effective contact areas between the extractants and the substrates, enhanced the cavitation effect, and expanded the extraction capacity, thus promoting the dissolution of the target compounds [12]. With water content varying, the yields of both crocin and geniposide first exhibited an ascending tendency to a peak, then followed by a decline. The addition of water decreased the viscosity of NADES and tailored the polarity, which improved the mass transfer of the target compounds from plant matrices to extractants. However, excessive water caused the rupture of hydrogen bonds in the supramolecular structures of NADES, which was detrimental to the extraction procedure [8]. It was noteworthy that at lower levels of water contents and SS ratios, the extraction efficiencies of both target components obtained by the pr-UAE-NADES system were lower than those obtained by the pl-UAE-NADES system. This might be because the vibration of the probe was hindered by high-viscosity NADES and there was an increasing possibility of the sample powders hitting the probe, which shortened the service life of the probe. However, with the increases of SS ratios and moistures, the extraction yields of both target ingredients obtained by the pr-UAE-NADES system were significantly higher than those obtained by the pl-UAE-NADES system. The pr-UAE-NADES system can make energy conservation more efficient due to its high energy transfer efficiency [10], and it is suited to work in circumstances of lower solvent viscosity and a higher SS ratio. As a result, the pr-UAE-NADES system was chosen for further process optimization, where the SS ratio was determined to be 1:40 (g/mL), and the optimization range of moisture contents was to be selected at 25%–45% (w/w) to guarantee the stability of the ultrasonic power during the extraction procedure and to protect the ultrasound probe.

Fig. 2.

Comparisons of the extraction effects on pl-UAE (pl) and pr-UAE (pr) integrated with NADES (CC-PG) of different water content (0%, 25%, 40%, w/w) at different SS ratios (1:20, 1:30, 1:40, g/mL): crocin yields (a) and geniposide yields (b). The different letters show significant differences between groups (P < 0.01) by using Tukey’s test.

3.3. Optimization of the extraction parameters of pr-UAE-NADES

3.3.1. Analysis of single-factor experiment results

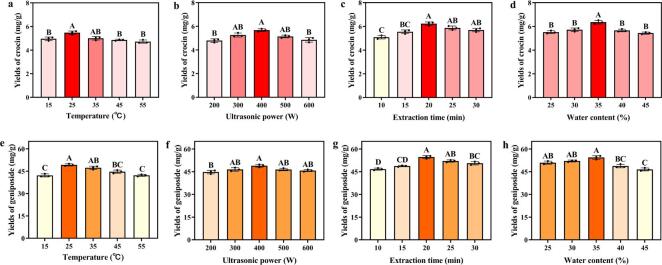

The results of the single-factor experiments, including four experimental factors (extraction temperature, ultrasonic power, extraction time, and water content in NADES) with five levels each, were shown in Fig. 3. It was demonstrated (Fig. 3a-h) that as the levels of each investigated factor raised, the extraction yields of both crocin and geniposide first increased and then decreased as the levels further increased. The increases in the extraction temperature and the ultrasonic power enhanced the cavitation effect and promoted the transmission of target compounds [12]. However, the extraction efficiencies tended to decline when the temperatures and the ultrasonic powers continued to increase, possibly owing to the structural damage of target components caused by excessive ultrahigh temperature and pressure [32]. As for the effect of ultrasonic extraction time on extraction yields, a longer duration of ultrasonic treatment caused complete cell wall rupture and more release of intracellular components [11]. However, an excessively prolonged extraction process also led to the degradation of compounds that were sensitive to heat and pressure [32]. The impact of the water content of NADES on the extraction rate has been discussed in Section 3.2. Based on the results of single-factor experiments, the orthogonal experiments were utilized to further optimize the extraction process parameters.

Fig. 3.

Single-factor experiments results of pr-UAE-NADES: effects of extraction temperatures (a, e), ultrasonic powers (b, f), ultrasonic extraction time (c, g), and water contents of NADES (CC-PG) (d, h) on crocin yields and geniposide yields, respectively. The different letters show significant differences between groups (P < 0.01) by using Tukey’s test.

3.3.2. Analysis of orthogonal experiment results using a synthetic weighted scoring method

In practical manufacturing testing, the average weighting method is primarily utilized to solve the multi-index test problem [3]. But the average weighting method disregards the distinctions and significances of indicators, and thus the analysis results are inaccurate [4]. The synthetic weighted scoring method is regarded as one of the scientific evaluation strategies for the multi-index orthogonal test results due to incorporating objective information and subject cognition [4].

The orthogonal experiment results were shown in Table 2. Range analysis produced the averages (Kij) and ranges (R) of the two indicators, the yields of crocin and geniposide, respectively (Table 3). The larger the R-value, the greater the impact of the level variation belonged to this factor on the experimental indicators. The orders of influence of the four factors were A > C > D > B on the yields of crocin and B > C > A > D on the yields of geniposide. The optimal combinations were A1B3C2D1 and A2B3C2D1, respectively.

Table 3.

Range (R) analysis obtained from orthogonal experiments.

| Indicators | Factors |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A)Temperature (°C) | (B)Ultrasonic power (W) | (C)Extraction time (min) | (D)Water content (%) | ||

| Crocin (mg/g) |

K1j | 6.64 | 6.38 | 6.30 | 6.61 |

| K2j | 6.50 | 6.37 | 6.70 | 6.33 | |

| K3j | 6.21 | 6.60 | 6.34 | 6.41 | |

| R | 0.44 | 0.23 | 0.40 | 0.28 | |

| Best level | A1 | B3 | C2 | D1 | |

| Order | A > C > D > B | ||||

| Geniposide (mg/g) |

K1j | 48.19 | 44.72 | 45.60 | 48.34 |

| K2j | 48.48 | 47.07 | 51.54 | 47.57 | |

| K3j | 46.84 | 51.72 | 46.37 | 47.60 | |

| R | 1.64 | 7.00 | 5.93 | 0.78 | |

| Best level | A2 | B3 | C2 | D1 | |

| Order | B > C > A > D | ||||

However, the results of the range analysis are biased because it is unable to distinguish whether the experimental errors or the changes in the factors and their levels are to blame for causing data fluctuations. Thus, it is necessary to analyze the variance of data. The Fisher F-test was performed to evaluate whether the factors significantly affected the experimental indicators. The larger the F-value, the more significant the influence of the factor on the experimental indicators [3]. As observed from Table 4, differences in the three repetitions of the two indicators were all insignificant (P > 0.01), suggesting that the experimental results were reproducible. The influences of all four factors on the yields of both crocin and geniposide were significant (P < 0.01). The orders of significance belonging to the four factors were C > A > D > B on the yields of crocin and B > C > A > D on the yields of geniposide. The R2 values were 0.965 and 0.987, respectively, indicating that changes in the factors and their levels can be responsible for 96.5% and 98.7% of the variation in the experimental results.

Table 4.

ANOVA analysis for experimental results from orthogonal experiments.

| Indicators | Source | SS | df | MS | F | P | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crocin (mg/g) | Repetition | 0.008 | 2 | 0.004 | 0.732 | P > 0.01 | Insignificant |

| A | 0.886 | 2 | 0.443 | 80.147 | P < 0.01 | Significant | |

| B | 0.305 | 2 | 0.153 | 27.620 | P < 0.01 | Significant | |

| C | 0.891 | 2 | 0.445 | 80.553 | P < 0.01 | Significant | |

| D | 0.378 | 2 | 0.189 | 34.163 | P < 0.01 | Significant | |

| Error | 0.088 | 16 | 0.006 | ||||

| Total | 2.556 | 26 | |||||

| R2 | 0.965 | ||||||

| Geniposide (mg/g) | Repetition | 0.002 | 2 | 0.001 | 0.003 | P > 0.01 | Insignificant |

| A | 13.772 | 2 | 6.886 | 20.028 | P < 0.01 | Significant | |

| B | 228.311 | 2 | 114.516 | 332.020 | P < 0.01 | Significant | |

| C | 187.551 | 2 | 93.775 | 272.744 | P < 0.01 | Significant | |

| D | 3.46 | 2 | 1.730 | 5.031 | P < 0.01 | Significant | |

| Error | 5.501 | 16 | 0.344 | ||||

| Total | 438.597 | 26 | |||||

| R2 | 0.987 | ||||||

SS means the sum of squares; df means the degree of freedom; MS means mean squares; Sig. means significance.

After the significant influences of factors on indicators were determined, it was necessary to further determine whether the differences between the levels of the factors were significant. Tukey’s test was adopted to analyze the levels of factors that had a significant influence on both indicators. The post-hoc multiple comparison results (Table S4 in Supplementary material) showed that neither the yields of crocin in the two levels of extraction time (C1, C3) nor the yields of geniposide in the two levels of extraction temperature (A1, A2) were significantly different (P > 0.01). Therefore, as for the yields of geniposide, the superior combination was either A1B3C2D1 or A2B3C2D1.

From the above analysis, it could be seen that determining the optimal simultaneous extraction conditions for both two indicators at once was difficult to be done only via range analysis and analysis of variance. Therefore, a modified multi-index synthetic weighted scoring method was designed and carried out as described in Section 2.8.3. According to Table S3 in Supplementary material, the optimized combination (A1B3C2D1) had a maximum synthetic weighted score of 29.46 (15.50 for the score of crocin yields, and 13.96 for the score of geniposide yields). The orthogonal experiment results were verified by reanalyzing the two indicators under the optimal combination of the four factors. And the crocin and geniposide yields (7.39 ± 0.20 mg/g and 57.99 ± 0.91 mg/g, respectively) were obtained, which were higher than the highest values in the orthogonal experiment results (7.01 ± 0.03 mg/g, 55.53 ± 0.54 mg/g) (P < 0.01) with a synthetic weighted score of 28.64 (14.72 for the score of crocin yields, 13.93 for the score of geniposide yields) and the extraction yields obtained by 60% ethanol under the same conditions (7.25 ± 0.14 mg/g, 57.23 ± 0.93 mg/g) (P > 0.01). Additionally, the optimal combination of the four factors determined by the average weighting method (A2B3C2D1) was also verified. The yields of crocin and geniposide were found to be 6.68 ± 0.26 mg/g (lower than the result of A1B3C2D1, P < 0.01) and 59.17 ± 1.07 mg/g (higher than the result of A1B3C2D1, P > 0.01), respectively. Interestingly, the synthetic weighted score of A2B3C2D1 was calculated to be 28.64 of which the score of crocin yields was 13.63 (lower than A1B3C2D1) and the score of geniposide yields was 14.10 (higher than A1B3C2D1). It could be seen that the distinctions of indicators were ignored in the average weighting method, and thus the result of optimization was one-sided. In conclusion, the modified multi-index synthetic weighted scoring method provided an effective approach for inferring complete experimental results based on results obtained by conducting the partial experimental, fully leveraging the uniformity and representativeness of orthogonal experimental design. Shang et al. [2] detected the contents of crocin and geniposide in dried gardenia fruit (8.76 ± 0.04 mg/g and 34.64 ± 0.45 mg/g, respectively). The differences in the contents may be related to the varieties and origins of gardenia used.

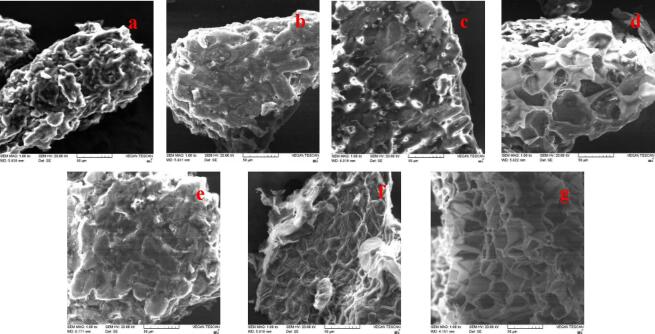

3.4. Microscopic structural analysis of gardenia fruit powders in different extraction procedures

To better understand the impacts of different extraction procedures (CHE, pl-UAE, pr-UAE) on extraction efficiencies, SEM was utilized to investigate the microscopic structures of gardenia fruit powders both before and after extraction. As presented in Fig. 4a, the gardenia fruit powders before extraction still retained a large amount of smooth fibrous structures with the primary cell structure well conserved. After 60% ethanol or CC-PG conventional heating extraction (CHE) (Fig. 4b & e), the surfaces of the dried gardenia fruits became rough with lengthy fissures. The moist texture was observed at the edge of the samples, which might be owing to the infiltration effect and erosion of the solvent to the matrices [12]. As shown in Fig. 4c-f & d-g, the gardenia fruit powders were cracked during UAE, resulting in holes, carpets, and fragmentation structures. The ultrasonic propagation into an elastic medium showed alternating strong and feeble cycles, causing bubbles to form during the disturbance phase. As a consequence of the bubble implosion, a hot spot with extremely high pressure and temperature emerged. This resulted in the disintegration of cell walls and the terrific penetration of the extraction solvent. Additionally, the cavitation effect created a dramatic shear force to advance the diffusion of compounds contained in the matrices [10]. Similar results were reported by Huang et al. [12]. In addition, compared to the pl-UAE system, the higher energy transfer efficiency in the pr-UAE system was indicated by the deeper and more densely distributed holes exposed in the powders extracted. A little difference was shown in the morphologies of powders after extraction by utilizing 60% ethanol and 25% CC-PG, suggesting that the distinctions between extraction yields obtained by ethanol and CC-PG were mainly caused by the differences in affinity between the solvent and the target compounds.

Fig. 4.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of dried gardenia fruits tissues used for different extraction procedures: without treatment (a), ethanol (60 %) based CHE (b), pl-UAE (c), and pr-UAE (d); CC-PG (25%) based CHE (e), pl-UAE (f), and pr-UAE (g).

3.5. Preliminary fractionation and enrichment of crocin and geniposide

Since NADES have quite low vapor pressure, it is exceedingly difficult to isolate target chemicals by simply evaporating. There are several possible approaches for target compounds recovery from NADES extracts, including liquid–liquid extraction with the inclusion of another solvent, solid–liquid extraction with the use of macroporous resins and solid-phase extraction, and the use of antisolvents [34], [35], [36]. Macroporous resins possess the advantages of high recovery, high extraction efficiency, excellent selectivity, and mild adsorption conditions. Thus, dynamic adsorption and desorption using AB-8 macroporous resin were adopted for the preliminary separation and enrichment of crocin and geniposide from the NADES extracts in the current study [17].

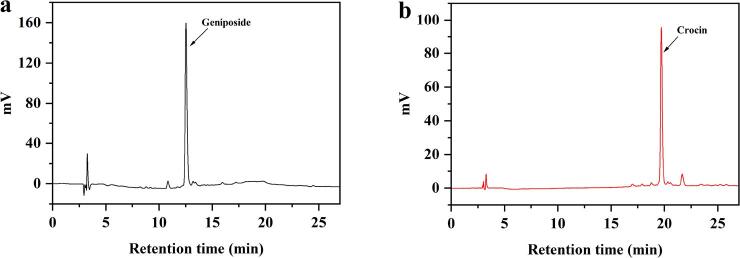

According to the HPLC quantitative analysis, most of the geniposides adsorbed could be eluted by 30% ethanol–water solution. The content of geniposides rose from 5.80% in crude extracts to 30.04% in the G1 fraction, with a recovery yield of 64.39%. The content of crocins in the 80% ethanol eluting fraction (G2 fraction) significantly increased from 0.74% in crude extracts to 6.13% in the G2 fraction, with a recovery yield of 84.62%. Chromatograms of G1 fraction and G2 fraction by HPLC were displayed in Fig. 5a & b, which suggested that geniposide was the main component in iridoid glycosides, and crocin was the primary compound in crocetin derivatives in this traditional Chinese herbal medicine [17].

Fig. 5.

HPLC chromatograms: G1 (a) at 240 nm and G2 (b) at 440 nm.

3.6. Identification of compounds in NADES extracts by LC-Q-TOF/MS2 and FBMN

After preliminary fractionation and enrichment, LC-Q-TOF/MS2 was applied for the identification and structural characterization of compounds in the G1 and G2 fractions. LC-MS2, primarily through untargeted data-dependent MS/MS methods, provides a versatile approach to identifying the composition of the natural product samples. However, a simple individual MS project usually obtains a lot of MS/MS spectra. Manually interpreting such complicated data represents one of the most challenging aspects of this research. Additionally, appropriate computational infrastructure and comprehensive software are not readily accessible. Therefore, efficient automated data processing and comparison with spectrum libraries pertinent to natural products are required to handle these data sets. Currently, innovative bioinformatics methods, notably MN, have appeared and introduced novel perspectives for assisting with the identification of compounds in complicated matrices. The Global Natural Product Social Molecular Networking web-based platform, an open-access database for tandem mass (MS/MS) spectrometry data, is a new approach that enables online dereplication and automated molecular networking for the analysis of LC-MS2-generated data sets [17], [37]. The main principle of molecular networking is the establishment of chemically similar networks by classifying specialized compounds into clusters based on MS/MS spectral similarities. The similarity of compounds is assessed using a modified cosine computation as a similarity score by comparing similarities between fragment ions, relative intensities, and m/z ratios of matched spectra. Many relevant instances revealed the application prospect of LC-MS2-based MN to discover novel biologically relevant components, illustrated the metabolite compositions of closely related species, and authenticated botanical products [19], [37]. FBMN, an improved MN approach incorporating isotope patterns, retention time, and ion mobility separation when performed [18], was applied in this study (Fig. 6). The nodes in the network represented molecules, and the edges depicted the cosine similarities between distinct MS/MS spectra (>0.50). The size of nodes was relative to ion intensities, and the width of edges indicated the strength of correlation between molecules.

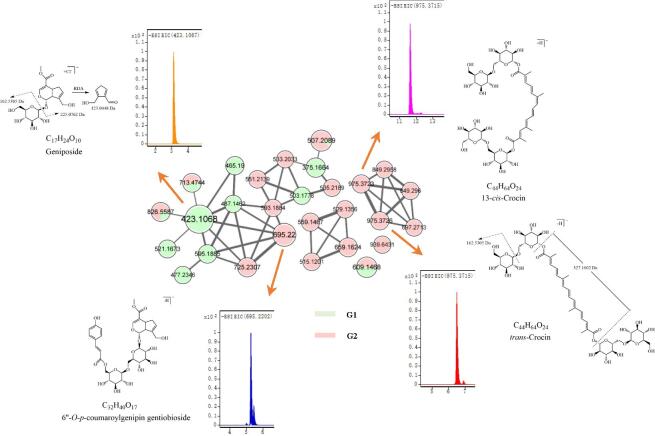

Fig. 6.

Molecular network based on LC-MS2 spectra of G1 (green) and G2 (pink) and chemical structures of trans-crocin, cis-crocin, geniposide, and 6′'-O-p-coumaroylgenipin gentiobioside with their extracted ion chromatograms. Node text indicates the m/z of the precursor ion. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

A total of 33 compounds including iridoids, carotenoids, phenolic acids, flavonoids, and triterpenes from the gardenia fruit were identified, among which 15 compounds were characterized unambiguously by MN annotation (Table 5 & Table 6). The molecular formulas of the other components were established taking into account high-accuracy quasi-molecular adduct ions such as [M−H]−, [M+Cl]−, and [M+HCOO]− within a mass error threshold at 5 ppm. Additionally, the most plausible molecular formulas were sought in chemical databases, such as PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and SciFinder (http://scifinder.cas.org). The fragmentations behaviors were employed to further confirm the structures of the compounds. The principles of fragmentation behaviors were investigated based on the spectra of reference compounds and then applied to the structural elucidation of novel derivatives with the same skeleton with marked similarity displayed by MN (Fig. 6). Finally, some compounds were verified by comparing them with the data provided in the literature.

Table 5.

Compounds identified in G1 by LC-Q-TOF/MS2.

| NO. | RT (min) | Precursor (m/z) | Formula | Mass error (ppm) | Adduct ion | Fragments (m/z) | Proposed compound | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.692 | 595.1886 | C23H34O15 | 1.05 | [M+HCOO]− | 225.0764, 123.0448 | Genipin-1-β-gentiobioside | [38] |

| 2 | 3.113 | 423.1078 | C17H24O10 | 3.42 | [M+Cl]− | 225.0762, 123.0448 | Geniposide | [16] |

| 3 | 3.296 | 519.1518 | C25H28O12 | 1.92 | [M−H]− | 475.1809, 355.1037, 211.0607, 145.0291 | 6′-O-trans-p-coumaroylgeniposidic acid | [17] |

| 4 | 3.412 | 503.1779 | C22H32O13 | 1.76 | [M−H]− | 470.0230, 223.0604 | 2-methyl-L-erythritol-4-O-(6-O-trans-sinapoyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside | [17] |

| 5 | 3.504 | 375.1661 | C17H28O9 | 0.12 | [M+HCOO]− | 113.0235, 281.1151 | Jasminoside A/E | [39] |

| 6 | 3.562 | 375.1664 | C17H28O9 | 0.91 | [M+HCOO]− | 113.0241, 281.1151 | Jasminoside A/E | [39] |

| 7 | 3.882 | 487.1464 | C21H28O13 | 1.40 | [M−H]− | 387.1306, 225.0766, 123.0451 | 10-O-succinoyl geniposide | [1] |

| 8 | 4.098 | 521.1673 | C25H30O12 | 1.63 | [M−H]− | 357.1195, 163.0399 | PubChem CID: 163190893 | PubChem |

| 9 | 4.677 | 477.2350 | C22H38O11 | 1.81 | [M−H]− | 431.2292, 269.1761 | No identified | / |

| 10 | 4.798 | 465.1902 | C21H34O9 | 1.20 | [M+Cl]− | 339.1818, 267.1489 | 10-O-acetylgeniposide | [17] |

| 11 | 4.973 | 609.1469 | C27H30O16 | 1.30 | [M−H]− | 300.0275, 271.0244 | Quercetin-3-O-rutinoside | [40] |

| 12 | 5.564 | 489.1980 | C22H34O12 | 0.51 | [M−H]− | 359.0749, 323.0984, 165.0919 | Jasminoside R | [17] |

| 13 | 5.676 | 713.4747 | C40H70O8 | −2.61 | [M+Cl]− | 546.9854, 225.1622 | No identified | / |

| 14 | 6.179 | 491.2141 | C22H36O12 | 1.42 | [M−H]− | 323.0987, 221.0667, 167.1074 | Jasminoside S/H/I | [17] |

| 15 | 6.447 | 826.5586 | C43H83O12 | −0.22 | [M+Cl]− | 225.1600 | No identified | / |

| 16 | 6.979 | 507.2089 | C21H34O11 | 1.97 | [M+Cl]− | 293.0877, 167.1074 | Jasminoside T | [17] |

RT means retention time.

Table 6.

Compounds identified in G2 by LC-Q-TOF/MS2.

| NO. | RT (min) | Precursor (m/z) | Formula | Mass error (ppm) | Adduct ion | Fragments (m/z) | Proposed compound | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.795 | 487.1460 | C21H28O13 | 0.58 | [M−H]− | 387.1276, 355.1020, 225.0768, 123.0449 | 10-O-succinoylgeniposide | PubChem |

| 2 | 4.899 | 609.1477 | C27H30O16 | 2.61 | [M−H]− | 300.0279, 271.0246, 343.0453 | Quercetin-3-O-rutinoside | [40] |

| 3 | 5.024 | 515.1201 | C25H24O12 | 1.16 | [M−H]− | 353.0880, 173.0451, 135.0441 | 4,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid | [39] |

| 4 | 5.045 | 659.1627 | C31H32O16 | 1.12 | [M−H]− | 497.1306, 335.0878, 191.0562, 161.0455 | 3,5-Di-O-caffeoyl-4-O-(3-hydroxy-3-methyl)-glutaroylquinic acid | [39] |

| 5 | 5.211 | 695.2220 | C32H40O17 | 3.92 | [M−H]− | 469.1360, 367.1025, 123.0451, 225.0768 | 6′'-O-p-coumaroylgenipin gentiobioside | [38] |

| 6 | 5.315 | 725.2307 | C33H42O18 | 1.32 | [M−H]− | 499.1453, 193.0506, 225.0763, 123.0449 | 6′'-O-trans-feruloylgenipin gentiobioside | [16] |

| 7 | 5.648 | 551.2138 | C27H36O12 | 0.72 | [M−H]− | 521.2032, 367.1034 | 6′-O-trans-sinapoyljasminoside L | [39] |

| 8 | 5.794 | 559.1445 | C27H28O13 | −2.17 | [M−H]− | 397.1146, 223.0612, 173.0456 | 4-Sinapoyl-5-caffeoylquinic acid | [40] |

| 9 | 6.006 | 529.1359 | C26H26O12 | 1.42 | [M−H]− | 367.1034, 173.0454, 137.0234 | 3′-O-feruloyl-4-O-caffeoylquinic acid | [1] |

| 10 | 6.131 | 593.1885 | C28H34O14 | 1.55 | [M−H]− | 367.1042, 205.0498, 123.0451 | 6′-trans-sinapoylgeniposide | [17] |

| 11 | 6.210 | 491.2130 | C22H36O12 | −0.81 | [M−H]− | 323.0988, 167.1078 | Jasminoside H | [16] |

| 12 | 6.502 | 975.3728 | C44H64O24 | 1.36 | [M−H]− | 651.2674, 327.1596 | Crocin-Ⅰ | [39] |

| 13 | 7.002 | 507.2089 | C22H36O13 | 1.15 | [M−H]− | 167.1077 | PubChem CID: 155530613 | PubChem |

| 14 | 7.168 | 939.6427 | C52H92O14 | 1.35 | [M−H]− | 939.6427 | No identified | / |

| 15 | 7.667 | 849.2958 | C38H54O19 | 0.55 | [M+Cl]− | 651.2659, 489.2127, 327.1600 | Crocin-Ⅱ | [39] |

| 16 | 8.046 | 535.2189 | C27H36O11 | 0.77 | [M−H]− | 325.0932, 265.0719 | 6′-O-trans-sinapoyljasminoside A | [17] |

| 17 | 8.375 | 533.2032 | C27H34O11 | 0.68 | [M−H]− | 205.0505, 165.0919 | 6′-O-trans-sinapoyljasminoside C | [17] |

| 18 | 9.582 | 697.2710 | C32H44O14 | −0.44 | [M+HCOO]− | 529.1567, 325.0929 | Crocin-Ⅲ | [41] |

| 19 | 10.698 | 987.3509 | C48H60O22 | 0.56 | [M−H]− | 825.3180, 651.2639, 327.1585 | PubChem CID: 141679037/148508070 | PubChem |

| 20 | 11.579 | 975.3723 | C44H64O24 | 0.84 | [M−H]− | 651.2666, 327.1597 | 13-cis-Crocin-Ⅰ | [39] |

| 21 | 12.599 | 849.2962 | C38H54O19 | 1.02 | [M+Cl]− | 651.2646, 489.2147, 327.1604 | 13-cis-Crocin-Ⅱ | [41] |

| 22 | 18.837 | 407.0933 | C26H15O5 | 1.97 | [M−H]− | 384.9908, 358.9757, 125.8731 | No identified | / |

| 23 | 19.587 | 333.2290 | C17H34O6 | 2.21 | [M−H]− | 275.1504, 233.1035, 175.1156 | No identified | / |

| 24 | 19.832 | 339.2329 | C23H31O2 | −0.16 | [M−H]− | 163.1129 | No identified | / |

The typical fragmentation patterns for iridoid glycosides contain the losses of a glucosyl moiety (162 Da), H2O, and retro Diels-Alder (RDA) reaction of the iridoid skeleton, generating the characteristic product ions at m/z 225, 123, and 101 [17]. The similarity of the MS/MS spectra of iridoid glycosides was reflected visually in the MN (Fig. 6), which assisted in the identification of compounds. For example, [M−H]− ions at m/z 695 displayed similar MS fragmentation patterns with genipin-1-β-gentiobioside in the MS/MS spectra (cosine score = 0.7012). Moreover, the loss fragment of 146 Da was supposed to be the discarded courmaroyl group. Therefore, it was identified as 6′'-O-p-coumaroylgenipin gentiobioside.

Successive losses of glycosides (162 Da or 324 Da) and CO2 (44 Da) are characteristic fragmentation behaviors for crocins in negative ion mode [17]. Crocins (crocetin derivatives) from the gardenia fruit mainly constituted by crocin 1–4 are almost glycosides of trans-crocetin that are high-abundant compared to cis-crocetin [17]. In the present study, the retention time of trans-crocin was obtained ahead of that of cis-crocin (Fig. 6). This pair of isomers were well identified with the assistance of FBMN, which was challenging in the conventional MN method [18].

3.7. Activity against LDL oxidation

LDL oxidation is the primary event in atherosclerosis, circulating oxidized LDL (ox-LDL) has been postulated as a marker for coronary artery disease [27]. In vitro, catalytic amounts of transition metal ions such as iron and copper were frequently used to simulate the oxidative modification of LDL in the cellular system. One of the most common approaches applied for evaluating the resistance of LDL to in vitro oxidation is the monitoring of the lag time for the generation of conjugated dienes (CD). The formation of CD indicates the initiation phase of LDL oxidation due to the polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) in the LDL lipid cores being attacked by free radicals, followed by molecular rearrangements [15]. To examine the inhibitory effects on LDL oxidation, the crocin and geniposide with high abundance profiles in the two components, respectively, were chosen to perform the CD evolution experiments.

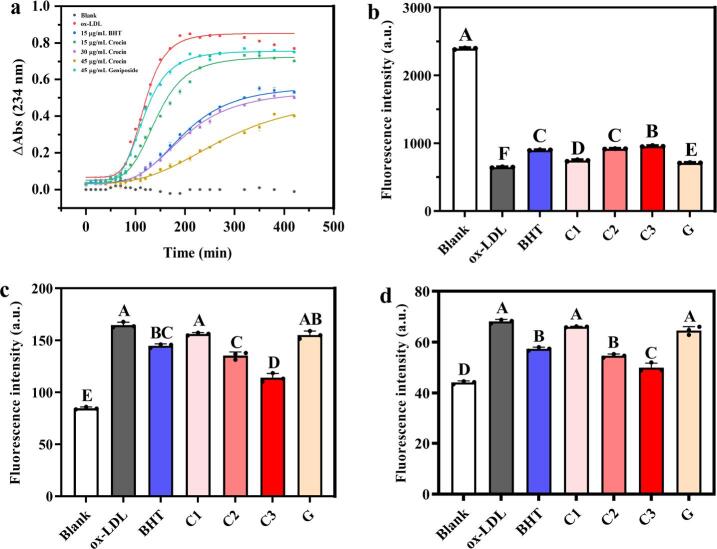

As displayed in Fig. 7a, the kinetics curves of the CD generation process demonstrated an initial lag phase (no remarkable increases in the absorbances), followed by a propagation phase with a maximum slope corresponding to the propagation rate that starts presumably after the endogenous antioxidants such as vitamin E have been exhausted; finally, a plateau phase with a slight decrease in the content of CD due to the further generation of lipid peroxidation products such as malondialdehyde (MDA) [15]. Lag time was considered as the time at which ΔAbs = 0.1 ΔAmax. To quantitatively evaluate the inhibition effects of the samples on LDL oxidation, the 4PL regression model, a widely used dose–response model, was conducted. As shown in Table 7, the additions of crocin into the LDL samples in a concentration-dependent manner (15 μg/mL, 30 μg/mL, 45 μg/mL) caused the decreases in propagation rate by 16.55%, 35.03%, and 45.25%, respectively, as well as the increases in lag time by 12.66%, 35.44%, and 73.42%. The results suggest crocin may be a potent agent in interrupting the chain of free-radical reactions in lipid peroxidation or chelating metal-ion. Wani et al. [29] found crocin was effective to inhibit the generation of malondialdehyde during LDL oxidation induced by Cu2+, which was consistent with the results of this study. In contrast, the geniposide only exhibited a slight inhibitory efficacy on the formation of CD.

Fig. 7.

The inhibition efficiency of crocin and geniposide on LDL oxidation: Conjugated dienes (CD) evolution (a), Trp fluorescence quenching (b), Lys residue oxidatively modified by reactive aldehydes (c) and malondialdehyde (d). C1: 15 μg/mL Crocin; C2: 30 μg/mL Crocin; C3: 45 μg/mL Crocin; G: 45 μg/mL geniposide. The different letters show significant differences between groups (P < 0.01) by using Tukey’s test.

Table 7.

Kinetic parameters of the 4PL regression model for the CD evolution.

| Group | PR (ΔAbs/min) | Protection (%) | X50/min | Tlag/min | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ox-LDL | 5.68 | / | 118.01 | 79 | 0.989 |

| 15 μg/mL BHT | 3.93 | 30.81 | 197.05 | 111 | 0.999 |

| 15 μg/mL Crocin | 4.74 | 16.55 | 142.35 | 89 | 0.995 |

| 30 μg/mL Crocin | 3.69 | 35.04 | 196.55 | 107 | 0.996 |

| 45 μg/mL Crocin | 3.11 | 45.25 | 280.14 | 137 | 0.994 |

| 45 μg/mL Geniposide | 4.67 | 17.79 | 116.92 | 73 | 0.997 |

PR means the propagation rate; X50 means the time at which ΔAbs = 50% ΔAmax; Tlag means the lag time.

Apo B-100 is the only protein component in LDL. Oxidative modification of apo B-100 leads to LDL shifting to recognition by scavenger receptors (ox-LDL receptors) and promoting the development of macrophage foam cells, the hallmark of the artery lesion of the fatty streak [42]. Oxidation of apo B-100 by Cu2+ forms derivatized products of oxidized amino acids, which associates their fluorescence properties altered: (1) the tryptophan (Trp) residues are oxidatively modified, resulting in quenching of fluorescence at Ex 295 nm/Em 330 nm; (2) malondialdehydes and reactive aldehydes form adducts with the lysine (Lys) residues to generate fluorophores, resulting in fluorescence absorption at Ex 390 nm/Em 460 nm and Ex 350 nm/Em 420 nm, respectively [43]. As shown in Fig. 7b-d, concentration-dependent treatments (15 μg/mL, 30 μg/mL, 45 μg/mL) of crocin in LDL samples inhibited the decline of fluorescence quenching of Trp residues and the formation of fluorophores due to oxidative modification of Lys residues, which exhibited a dose-dependent relationship (P < 0.01). However, the geniposide only exhibited a slight inhibitory efficacy on apo B-100 oxidation. These observations were in agreement with the result of the CD evaluation experiment, which suggests that crocin may protect the structure of apo B100 by inhibiting the formation of lipid peroxides that can cause further oxidative modification of the apo B100 [15].

4. Conclusion

In this study, an efficient and environmentally friendly method for the simultaneous extraction of two characteristic compounds from gardenia fruits, namely crocin and geniposide was established by UAE-NADES, and the inhibition effects of these two target compounds on LDL oxidation were evaluated. The CC-PG was selected as the suitable NADES for the simultaneous extraction of these two target compounds. Compared with pl-UAE and CHE, pr-UAE combined with CC-PG demonstrated higher extraction efficiency. The orthogonal experimental design coupled with a modified multi-index synthetic weighted scoring method was used to optimize the extraction conditions for pr-UAE-NADES. The optimum extraction conditions with a maximum synthetic weighted score of 29.46 (15.50 for the score of crocin yields, 13.96 for the score of geniposide yields) consisted of extraction temperature of 25 °C, ultrasonic power of 600 W, extraction time of 20 min, and CC-PG water content of 25% (w/w). Under the optimal parameters setting, the yields of crocin and geniposide reached 7.39 ± 0.20 mg/g and 57.99 ± 0.91 mg/g, respectively. Through LC-Q-TOF/MS2 integrated with FBMN analysis, thirty-three components in gardenia fruits were identified, including iridoids, carotenoids, phenolic acids, flavonoids, and triterpenes. Crocin showed effective inhibitions on Cu2+-induced LDL oxidation in a concentration-dependent manner, which suggest the potential of developing novel anti-atherogenic functional food based on gardenia fruits. Overall, the CC-PG coupled with pr-UAE provides a greater probability for the effective valorization of crocin and geniposide from gardenia fruits in the food and pharmaceutical industries.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yuxin Gan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Chenyu Wang: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Chenfeng Xu: Investigation. Pingping Zhang: Methodology. Shutong Chen: Investigation. Lei Tang: Methodology. Junbing Zhang: Resources. Huahao Zhang: Methodology, Funding acquisition. Shenhua Jiang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31360371), the Key Research and Development Project and Talent Foundation of Jiang Xi Province (20202BBF63012, 20192BCBL23028 and 20202ACBL215008), and the Tianjin Research Innovation Project for Postgraduate Students (2021YJSS138).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106658.

Contributor Information

Pingping Zhang, Email: zpp613@163.com.

Shenhua Jiang, Email: jiangshenhua66@163.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Chen L., Li M., Yang Z., Tao W., Wang P., Tian X., Li X., Wang W. Gardenia jasminoides Ellis: Ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry, and pharmacological and industrial applications of an important traditional Chinese medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020;257 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.112829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shang Y.F., Zhang Y.G., Cao H., Ma Y.L., Wei Z.J. Comparative study of chemical compositions and antioxidant activities of Zhizi fruit extracts from different regions. Heliyon. 2019;5 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liao M., Jin R., Ren H., Shang J., Kang J., Xin Q., Liu N., Li M. Orthogonal experimental design for the optimization of four additives in a model liquid infant formula to improve its thermal stability. Lwt. 2022;163 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2022.113495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng J., Yin G., Tuo H., Niu Z. Parameter optimization and regression analysis for multi-index of hybrid fiber-reinforced recycled coarse aggregate concrete using orthogonal experimental design. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021;267 doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaoui S., Chebli B., Zaidouni S., Basaid K., Mir Y. Deep eutectic solvents as sustainable extraction media for plants and food samples: A review. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2023;31 doi: 10.1016/j.scp.2022.100937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fu X., Wang D., Belwal T., Xu Y., Li L., Luo Z. Sonication-synergistic natural deep eutectic solvent as a green and efficient approach for extraction of phenolic compounds from peels of Carya cathayensis Sarg. Food Chem. 2021;355 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.J. Osamede Airouyuwa, H. Mostafa, A. Riaz, S. Maqsood, Utilization of natural deep eutectic solvents and ultrasound-assisted extraction as green extraction technique for the recovery of bioactive compounds from date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) seeds: An investigation into optimization of process parameters, Ultrason. Sonochem., 91 (2022) 106233, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Dai Y., Witkamp G.J., Verpoorte R., Choi Y.H. Tailoring properties of natural deep eutectic solvents with water to facilitate their applications. Food Chem. 2015;187:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.03.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao Y., Wan H., Yang J., Huang Y., He Y., Wan H., Li C. Ultrasound-assisted preparation of 'Ready-to-use' extracts from Radix Paeoniae Rubra with natural deep eutectic solvents and neuroprotectivity evaluation of the extracts against cerebral ischemic/ reperfusion injury. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022;84 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.105968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khadhraoui B., Ummat V., Tiwari B.K., Fabiano-Tixier A.S., Chemat F. Review of ultrasound combinations with hybrid and innovative techniques for extraction and processing of food and natural products. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;76 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu X., Wang D., Belwal T., Xie J., Xu Y., Li L., Zou L., Zhang L., Luo Z. Natural deep eutectic solvent enhanced pulse-ultrasonication assisted extraction as a multi-stability protective and efficient green strategy to extract anthocyanin from blueberry pomace. Lwt. 2021;144 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang H., Zhu Y., Fu X., Zou Y., Li Q., Luo Z. Integrated natural deep eutectic solvent and pulse-ultrasonication for efficient extraction of crocins from gardenia fruits (Gardenia jasminoides Ellis) and its bioactivities. Food Chem. 2022;380 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amarowicz R., Pegg R.B. Protection of natural antioxidants against low-density lipoprotein oxidation. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2020;93:251–291. doi: 10.1016/bs.afnr.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim J.-Y., Lee J.W., Lee J.S., Jang D.S., Shim S.H. Inhibitory effects of compounds isolated from roots of Cynanchum wilfordii on oxidation and glycation of human low-density lipoprotein (LDL) J. Funct. Foods. 2019;59:281–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2019.05.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.García Fillería S.F., Tironi V.A. Prevention of in vitro oxidation of low density lipoproteins (LDL) by amaranth peptides released by gastrointestinal digestion. J. Funct. Foods. 2017;34:197–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2017.04.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saravanakumar K., Park S., Sathiyaseelan A., Kim K.N., Cho S.H., Mariadoss A.V.A., Wang M.H. Metabolite profiling of methanolic extract of Gardenia jaminoides by LC-MS/MS and GC-MS and its anti-diabetic, and anti-oxidant activities. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021;14 doi: 10.3390/ph14020102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang L., Liu S., Zhang X., Xing J., Liu Z., Song F. A strategy for identification and structural characterization of compounds from Gardenia jasminoides by integrating macroporous resin column chromatography and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry combined with ion-mobility spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A. 2016;1452:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2016.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nothias L.F., Petras D., Schmid R., Duhrkop K., Rainer J., Sarvepalli A., Protsyuk I., Ernst M., Tsugawa H., Fleischauer M., Aicheler F., Aksenov A.A., Alka O., Allard P.M., Barsch A., Cachet X., Caraballo-Rodriguez A.M., Da Silva R.R., Dang T., Garg N., Gauglitz J.M., Gurevich A., Isaac G., Jarmusch A.K., Kamenik Z., Kang K.B., Kessler N., Koester I., Korf A., Le Gouellec A., Ludwig M., Martin H.C., McCall L.I., McSayles J., Meyer S.W., Mohimani H., Morsy M., Moyne O., Neumann S., Neuweger H., Nguyen N.H., Nothias-Esposito M., Paolini J., Phelan V.V., Pluskal T., Quinn R.A., Rogers S., Shrestha B., Tripathi A., van der Hooft J.J.J., Vargas F., Weldon K.C., Witting M., Yang H., Zhang Z., Zubeil F., Kohlbacher O., Bocker S., Alexandrov T., Bandeira N., Wang M., Dorrestein P.C. Feature-based molecular networking in the GNPS analysis environment. Nat. Methods. 2020;17:905–908. doi: 10.1038/s41592-020-0933-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jouaneh T.M.M., Motta N., Wu C., Coffey C., Via C.W., Kirk R.D., Bertin M.J. Analysis of botanicals and botanical supplements by LC-MS/MS-based molecular networking: Approaches for annotating plant metabolites and authentication. Fitoterapia. 2022;159 doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2022.105200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kessner D., Chambers M., Burke R., Agus D., Mallick P. ProteoWizard: open source software for rapid proteomics tools development. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2534–2536. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katajamaa M., Miettinen J., Oresic M. MZmine: toolbox for processing and visualization of mass spectrometry based molecular profile data. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:634–636. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btk039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pluskal T., Castillo S., Villar-Briones A., Oresic M. MZmine 2: modular framework for processing, visualizing, and analyzing mass spectrometry-based molecular profile data. BMC Bioinf. 2010;11:395. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myers O.D., Sumner S.J., Li S., Barnes S., Du X. One step forward for reducing false positive and false negative compound identifications from mass spectrometry metabolomics data: new algorithms for constructing extracted ion chromatograms and detecting chromatographic peaks. Anal. Chem. 2017;89:8696–8703. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b00947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.M. Wang, J.J. Carver, V.V. Phelan, L.M. Sanchez, N. Garg, Y. Peng, D.D. Nguyen, J. Watrous, C.A. Kapono, T. Luzzatto-Knaan, C. Porto, A. Bouslimani, A.V. Melnik, M.J. Meehan, W.T. Liu, M. Crusemann, P.D. Boudreau, E. Esquenazi, M. Sandoval-Calderon, R.D. Kersten, L.A. Pace, R.A. Quinn, K.R. Duncan, C.C. Hsu, D.J. Floros, R.G. Gavilan, K. Kleigrewe, T. Northen, R.J. Dutton, D. Parrot, E.E. Carlson, B. Aigle, C.F. Michelsen, L. Jelsbak, C. Sohlenkamp, P. Pevzner, A. Edlund, J. McLean, J. Piel, B.T. Murphy, L. Gerwick, C.C. Liaw, Y.L. Yang, H.U. Humpf, M. Maansson, R.A. Keyzers, A.C. Sims, A.R. Johnson, A.M. Sidebottom, B.E. Sedio, A. Klitgaard, C.B. Larson, C.A.B. P, D. Torres-Mendoza, D.J. Gonzalez, D.B. Silva, L.M. Marques, D.P. Demarque, E. Pociute, E.C. O'Neill, E. Briand, E.J.N. Helfrich, E.A. Granatosky, E. Glukhov, F. Ryffel, H. Houson, H. Mohimani, J.J. Kharbush, Y. Zeng, J.A. Vorholt, K.L. Kurita, P. Charusanti, K.L. McPhail, K.F. Nielsen, L. Vuong, M. Elfeki, M.F. Traxler, N. Engene, N. Koyama, O.B. Vining, R. Baric, R.R. Silva, S.J. Mascuch, S. Tomasi, S. Jenkins, V. Macherla, T. Hoffman, V. Agarwal, P.G. Williams, J. Dai, R. Neupane, J. Gurr, A.M.C. Rodriguez, A. Lamsa, C. Zhang, K. Dorrestein, B.M. Duggan, J. Almaliti, P.M. Allard, P. Phapale, L.F. Nothias, T. Alexandrov, M. Litaudon, J.L. Wolfender, J.E. Kyle, T.O. Metz, T. Peryea, D.T. Nguyen, D. VanLeer, P. Shinn, A. Jadhav, R. Muller, K.M. Waters, W. Shi, X. Liu, L. Zhang, R. Knight, P.R. Jensen, B.O. Palsson, K. Pogliano, R.G. Linington, M. Gutierrez, N.P. Lopes, W.H. Gerwick, B.S. Moore, P.C. Dorrestein, N. Bandeira, Sharing and community curation of mass spectrometry data with Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking, Nat. Biotechnol., 34 (2016) 828-837, http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N.S., Wang J.T., Ramage D., Amin N., Schwikowski B., Ideker T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papadea P., Skipitari M., Kalaitzopoulou E., Varemmenou A., Spiliopoulou M., Papasotiriou M., Papachristou E., Goumenos D., Onoufriou A., Rosmaraki E., Margiolaki I., Georgiou C.D. Methods on LDL particle isolation, characterization, and component fractionation for the development of novel specific oxidized LDL status markers for atherosclerotic disease risk assessment. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.1078492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oh W.Y., Ambigaipalan P., Shahidi F. Quercetin and its ester derivatives inhibit oxidation of food, LDL and DNA. Food Chem. 2021;364 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Musetti B., Gonzalez-Ramos H., Gonzalez M., Bahnson E.M., Varela J., Thomson L. Cannabis sativa extracts protect LDL from Cu(2+)-mediated oxidation. J. Cannabis Res. 2020;2 doi: 10.1186/s42238-020-00042-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wani M.J., Salman K.A., Moin S., Arif A. Effect of crocin on glycated human low-density lipoprotein: A protective and mechanistic approach. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023;286 doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2022.121958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tzani A., Kalafateli S., Tatsis G., Bairaktari M., Kostopoulou I., Pontillo A.R.N., Detsi A. Natural deep eutectic solvents (NaDESs) as alternative green extraction media for ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) Sustain. Chem. 2021;2:576–599. doi: 10.3390/suschem2040032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]