Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells represent a promising frontier in cancer immunotherapy. However, the current process for developing new CAR constructs is time consuming and inefficient. To address this challenge and expedite the evaluation and comparison of full-length CAR designs, we have devised a novel cloning strategy. This strategy involves the sequential assembly of individual CAR domains using blunt ligation, with each domain being assigned a unique DNA barcode. Applying this method, we successfully generated 360 CAR constructs that specifically target clinically validated tumor antigens CD19 and GD2. By quantifying changes in barcode frequencies through next-generation sequencing, we characterize CARs that best mediate proliferation and expansion of transduced T cells. The screening revealed a crucial role for the hinge domain in CAR functionality, with CD8a and IgG4 hinges having opposite effects in the surface expression, cytokine production, and antitumor activity in CD19- versus GD2-based CARs. Importantly, we discovered two novel CD19-CAR architectures containing the IgG4 hinge domain that mediate superior in vivo antitumor activity compared with the construct used in Kymriah, a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved therapy. This novel screening approach represents a major advance in CAR engineering, enabling accelerated development of cell-based cancer immunotherapies.

Keywords: cancer immunotherapy, cell therapy, protein engineering, chimeric antigen receptors

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-based cancer immunotherapy has proven successful in treating hematologic malignancies, leading to complete remission for many patients with refractory hematologic malignancies.1,2,3 CAR-based immunotherapies use synthetic receptors that redirect immune effector cells to target cancer cells on the basis of recognition of extracellular antigens.4,5,6 These receptors consist of several essential components: (1) an extracellular antigen-recognition domain, typically a single-chain variable fragment (scFv); (2) a hinge region linking the extracellular domain to the transmembrane domain; (3) a single-pass transmembrane domain; (4) one or two cytoplasmic costimulatory domains (second- or third-generation CARs, respectively) that enhance T cell activation by providing “signal two”; and (5) a cytoplasmic domain containing immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs), usually from CD3ζ, that provides “signal one” and is required for T cell activation.7,8,9,10 Each domain plays a critical role in generating effective tumor-specific activity; for instance, the choice of hinge and transmembrane domains can dramatically affect activation threshold, cytokine profile, and cytotoxicity of effector cells.11,12,13 Additionally, the scFv domain can induce antigen-independent clustering and tonic signaling, leading to exhaustion and limited in vivo persistence.14,15

Evaluating CAR domain combinations is impeded by the complex nature of these synthetic constructs and the increasingly large number of immune receptor domains they can be based on. Traditional testing strategies for new CAR architectures are limited by the time and cost of cloning and testing individual constructs. As such, only a fraction of possible domain combinations have been tested to date. To address this, high-throughput methods have been developed to study CARs, focusing on either the intracellular16,17,18,19,20 or scFv domains.21,22 These methods use next-generation sequencing (NGS) to directly sequence the domain pools or use rounds of enrichment followed by Sanger sequencing of a smaller number of individual clones. Alternatively, long-read sequencing has been used to link DNA barcodes with individual variants23 or combinations of assembled intracellular domains.20 However, these approaches suffer from low library coverage due to random assembly biases and loss of low-frequency library members after bottlenecking. Therefore, new methods are needed to effectively test full-length CAR domain combinations.

Serial barcoded DNA assembly is an attractive approach for studying protein domain combinations. This strategy has been used for combinatorial testing of single amino acid mutations in SpCas924 and all single-codon mutants of the AAV2 cap gene.25 These powerful approaches rely on ligating compatible type IIs restriction enzyme-generated overhangs between segments encoding different protein domains and are well suited for studying variants of a single protein or shuffling a group of related proteins while keeping junction amino acid residues constant. However, these methods are suboptimal for proteins composed of heterologous domains like CARs, where even small changes such as single alanine insertions can dramatically affect CAR activity.26,27 To overcome this, we developed a blunt ligation-based cloning strategy for serial barcoded DNA assembly that eliminates the requirement for compatible junctions. This approach can incorporate any desired antigen-binding domain as the final cloning step, accelerating the evaluation of CAR architectures targeting cancer antigens of interest. Using this method, we characterized 360 CAR domain combinations targeting two distinct tumor antigens: CD19 and GD2. Our results provide novel insights into how CAR architecture affects function and identify optimized domain combinations that mediate potent antitumor activity.

Results

Development of barcoded protein domain combination pooled screening

To generate libraries of barcoded CAR domain combinations, we developed an assembly strategy in which individual domains of each class are cloned together through stepwise blunt ligation reactions, and each domain is associated with a single unique barcode (Figure S1). The use of blunt-end ligation reactions enables fusion of protein-coding sequences without altering amino acid sequences at domain junctions. Consequently, each CAR in the library possesses a single predetermined DNA barcode corresponding to each of its serially assembled domains (Figure 1A). We generated a CAR library that targets B cell antigen CD19 using the FMC63 scFv and subcloned it into a retroviral vector with an internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-nerve growth factor receptor (NGFR) transduction marker. The library is composed of 180 distinct CAR constructs, each uniquely barcoded, encompassing various hinge, costimulatory, and activating domains (Figure 1B). To validate the accuracy of the assembly process, we sequenced plasmid clones and observed that approximately 80% of the generated CARs had barcodes corresponding to the expected protein domains (Figure S2A). We transduced this library into Jurkat cells,28 aiming for a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.3–0.5 to ensure that most cells undergo a single retroviral integration event. Retrovirally transduced barcoded libraries can theoretically suffer from high recombination rates between constructs, leading to inaccurate barcoding.29 We performed single-cell sorting of transduced Jurkat cells followed by Sanger sequencing of individual clones and found the barcoding accuracy to be 73% (Figure S2B). Most discrepancies between expected and sequenced barcodes were found within the costimulatory domain sequences of third-generation CARs. Additionally, there were biases in domain frequencies within the library; for example, the 4-1BB costimulatory domain had a frequency of 2%–10% instead of the theoretically expected 20% if the costimulatory domains were evenly distributed (Figure S2C). Despite these biases, we detected 88%–96% of all expected library members (Figure S2D).

Figure 1.

Establishing CAR barcoded pooled screen

(A) Schematic showing the seamless combinatorial blunt-end gene assembly protocol we developed in which sequentially cloned CAR domains simultaneously generate hundreds of distinct full CAR constructs with unique predetermined barcodes. scFv, single-chain variable fragment; Hin, hinge; TM, transmembrane; Cos, costimulatory domain; Act, activating domain. (B) Schematic showing the full list of CAR domains tested in this study, comprising 180 library members targeting CD19 and GD2 with varying hinge, costimulatory, and activating domains. (C) To test the CD19-CAR library, gammaretroviral supernatant was produced and MOI determined, then transduced into Jurkat cells at an MOI of 0.3–0.5. The transduced cells were co-cultured with Raji cells for 6 h and sorted between CD69+ and CD69− cells, and CAR barcodes were quantified via NGS. Cell activation was determined for each CAR as the log2 ratio between CD69+ and CD69− normalized reads. (D) Technical replicates of CD19 CAR library activation show reproducibility of CAR screen. (E) CD19 CAR library was screened in primary T cells as in (C) and then grouped on the basis of CD3ζ domain. The gray shaded area corresponds to two SDs from the CD3ζmt mean, shown as a horizontal bar. CARs with CD3ζWT domain have higher CD69 induction relative to CD3ζmt (p = 0.0003, Mann-Whitney test).

To assess the feasibility of pooled screening for CAR constructs, we co-cultured 20 × 106 CAR-Jurkat cells 1:1 with CD19+ Raji cells and assessed cell activation via CD69 immunofluorescence staining (Figure 1C). We isolated CD69−/NGFR+ and CD69+/NGFR+ Jurkat cells via fluorescence-activated cell sorting and then sequenced the DNA barcodes. For each CAR, we calculated the normalized barcode read ratio of CD69+ to CD69− cells, revealing that CD69 induction was reproducible between technical replicates (Figure 1D; R2 = 0.96). We repeated this experiment using primary T cells and compared CARs containing either the wild-type (WT) or mutant (mt) version of activating domain CD3ζ, which contains ITAM sequences essential for transforming antigen binding into T cell activation. The ITAM sequences are mutated in CD3ζmt, to impair T cell activation.7 As expected, CARs with the CD3ζWT domain mediated higher CD69 fold induction compared with CARs with CD3ζmt (Figure 1E). These results demonstrate that our methodology enables generation of accurately barcoded libraries of CAR domain combinations that can be used to differentiate between CARs exhibiting expected active versus inactive phenotypes in a pooled screening approach.

CAR library screening for expansion and proliferation discriminates between active and inactive CARs in primary T cells

We used an intermediate assembly step to create a second library of 180 CARs subcloning the 14g2a scFv that targets neuroblastoma antigen GD230 (Figure 1B). We transduced primary T cells with both CD19- and GD2-CAR libraries and screened for two clinically relevant phenotypes: relative expansion following four (GD2) or six (CD19) rounds of antigen stimulation, as well as cell proliferation determined by CellTrace Violet dilution sorting after two rounds of stimulation. Initial testing revealed that T cells transduced with the GD2-CAR library had limited proliferation when co-culturing with tumor cells, but addition of IL-2 to the co-culture improved this measure. Notably, both CD19- and GD2-CAR libraries demonstrated significant differences in relative expansion and proliferation between CARs containing the CD3ζWT versus CD3ζmt domain (Figures 2A–2D). Overall, the CD19-CAR library screen identified more active CARs than the GD2-based library, likely because of a combination of scFv- and tumor-specific factors.

Figure 2.

GD2- and CD19-CAR library expansion and proliferation library screens distinguish between CARs containing CD3ζWT and CD3ζmt domains

(A and B) Primary T cells were transduced with CAR libraries (A, CD19; B, GD2) and then exposed to six (CD19) or four (GD2) cycles of antigen stimulation with irradiated tumor cells in a 1:2 effector/tumor ratio every 2–3 days (CD19, Raji; GD2, CHLA-255). Cells were collected on day 0 and at the end of the repeated stimulations, and barcodes quantified via NGS. Relative expansion was calculated as the log2 normalized ratio of CAR barcode frequencies of total cells between day 0 and the last cycle, and CARs were again grouped on the basis of CD3ζ status. (C and D) T cells were transduced with CD19- and GD2-CAR libraries (C, CD19; D, GD2), stained with CellTrace Violet, and exposed to two cycles of antigen stimulation. After stimulation, CellTrace-high and CellTrace-low cells were sorted and sequenced (n = 4 donors; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney test). The gray shaded area corresponds to two SDs from the CD3ζmt mean.

Individual domain analysis reveals hinge domain effect on CAR activity depends on the scFv domain

The combinatorial nature of our screen allowed us to assess how different hinge domains affect the relative expansion and proliferation of T cells expressing CD3ζWT CARs. For CD19-CARs, constructs with the IgG4 short hinge mediated higher relative expansion and similar proliferation of transduced T cells compared with constructs with the CD8a hinge (Figures 3A and 3C). For GD2-CARs, the CD8a hinge outperformed others for both phenotypes (Figures 3B and 3D). Interestingly, constructs with the CD28 hinge performed the worst in both libraries, suggesting it is a less modular domain likely requiring its corresponding CD28 transmembrane domain for optimal activity. To further compare the IgG4 and CD8a hinges, we generated four CAR constructs with a second-generation 4-1BB costimulatory domain, varying the scFv (CD19 or GD2) and hinge domains (IgG4 or CD8a). We first measured individual CAR expression and observed that, compared with IgG4, the CD8a hinge mediated higher levels of CAR surface expression in CD19 CAR-T cells but lower expression in GD2 CAR-T cells (Figures 3E and 3F). There was no difference in IFNγ production for T cells expressing CD19-CARs with either hinge (Figure 3G). However, T cells expressing the GD2-CAR construct with the CD8a hinge mediated significantly higher IFNγ production (Figure 3H). When examining the impact of the hinges following repeated stimulation, we found no significant impact on tumor control for CD19-CARs regardless of the hinge (Figure 3I). In contrast, the GD2-CAR demonstrated better tumor control in the construct containing the CD8a hinge versus IgG4, correlating with IFNγ production (Figure 3J). To assess the role of costimulatory domains, we performed a global comparison between second- and third-generation CARs with the CD3ζWT domain on the basis of performance in the relative expansion and proliferation screens and found no significant differences between these architectures (Figure S3). An additional comparison focusing on the membrane-proximal31 costimulatory domain in each CAR identified 4-1BB as the best performing costimulatory domain; however, this was only statistically significant for the GD2 relative expansion screen (Figure S4). Unexpectedly, the CD28WT costimulatory domain performed slightly worse than 4-1BB in the proliferation screens, contrary to its well-described ability to mediate superior proliferation.5 This observation could be because CARs with CD28 costimulation secrete high levels of cytokines, dampening the ability of this domain to induce rapid proliferation in a pooled screening context because of bystander effects. In addition, we noticed many of the top-performing CARs in the proliferation screen were missing hinge and/or transmembrane domains, suggesting that the proliferation phenotype may be less accurate in identifying functional CARs. In all, these results suggest that hinge domains affect CAR function according to the scFv domain they are paired with, and they illustrate that evaluating different domain combinations can reveal new functional insights for the overall receptor.

Figure 3.

Hinge domains have different effects on CD19- and GD2-CARs

(A–D) Analysis of CD3ζWT CARs screened as described in Figure 2, grouped on the basis of hinge domain. ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0001, Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons. (E–J) CAR constructs with 4-1BB costimulatory domain and different scFv and hinge domains were cloned and tested individually in four T cell donors. (E and F) CAR median fluorescence intensity (MFI) comparison between CARs with indicated hinge domains, measured 10 days post-transduction; ∗p = 0.0390 and ∗∗p = 0.0080, paired t test. (G and H) IFNγ secretion ELISA from individual 4-1BB CARs with different hinge domains after 24 h of co-culture with tumor cells in a 1:2 effector/tumor ratio. ∗p = 0.0260, paired t test. (I and J) CAR T cells were stimulated with tumor cells every 2–3 days in an initial 1:2 effector/tumor ratio for six cycles, and residual tumor was measured using flow cytometry. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA.

CAR library screens identify both established and novel domain combinations, with a preference for the 4-1BB costimulatory domain

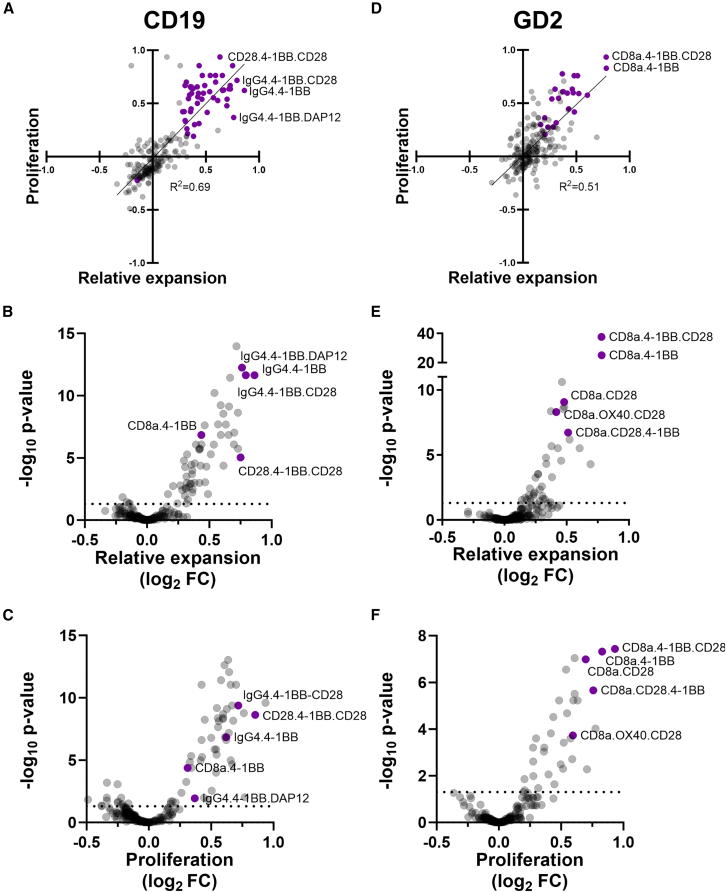

In addition to a global assessment of domain function, we also evaluated the performance of individual CAR constructs in relative expansion and proliferation screens. In both CD19-and GD2-CAR screens we found a correlation between proliferation and relative expansion results (Figures 4A and 4D). Consistent with our previous findings, CD19-CARs with the IgG4 hinge domain mediated more robust relative expansion of transduced cells, while the same was true for the CD8a hinge in GD2-CARs. For CD19-CARs in the relative expansion screen (Figure 4B), we observed that top hits included CARs with the 4-1BB costimulatory domain alone or with either DAP12 or CD28. We also identified known CAR architectures including CD8a.4-1BB, which is the structure of Kymriah, an U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved cell therapy for CD19+ malignancies.32 Interestingly, a construct containing the CD28 hinge domain also performed well on the screens. Comparing CARs between screens, the CD28.4-1BB.CD28 CAR had better proliferation, while IgG4.4-1BB.DAP12 had better relative expansion (Figures 4A–4C). For GD2, the dominant CARs identified in both screens also had the 4-1BB costimulatory domain alone or with CD28 in third-generation format, as well as the CD8a hinge paired with CD28 (Figures 4D–4F).

Figure 4.

GD2 and CD19 expansion and proliferation library screens show both novel and known CAR architectures

(A and D) Results from relative expansion and proliferation screens shown in XY plot, with constructs in purple having p values <0.05: (A) CD19-CARs and (D) GD2-CARs. Volcano plots for CAR library screen results for CD19-CAR relative expansion (B) and proliferation (C) and GD2-CAR relative expansion (E) and proliferation (F); horizontal dotted lines indicate p = 0.05, and purple circles represent CAR structures of interest.

Construct size, costimulatory domain, and viral supernatant concentration influence GD2-CAR in vitro antitumor activity

We selected a subset of hits from the GD2 proliferation and relative expansion screens and evaluated the ability of each construct to mediate antitumor activity following repeated stimulation with tumor cells. We found that T cells expressing the CD8a.4-1BB CAR controlled tumor growth more effectively than those expressing CD8a.OX40.CD28 and CD8a.CD28.4-1BB, and comparably with CD8a.4-1BB.CD28 (Figure 5A). These results show that our screening process identifies both known and novel CAR architectures that mediate potent antitumor activity in transduced T cells. The fact that the GD2-CD8a.4-1BB CAR mediated effective antitumor activity is contrary to previous observations with this construct using a gammaretroviral long terminal repeat (LTR) expression platform,30,33,34 although this CAR architecture is under clinical investigation.35 CARs are normally transduced using concentrated supernatant to maximize transduction rates, leading to multi-copy integration. However, our screens were performed using diluted viral supernatant (∼3% v/v) leading to an MOI of 0.3–0.5 to maximize single-copy integrations. In addition, the CAR library and individual constructs tested contain an IRES-NGFR sequence, which could also affect transgene expression. We tested GD2 CD8a.4-1BB CAR constructs with and without the IRES-NGFR sequence and evaluated multiple viral supernatant dilutions for transductions. We found that the transduction rate correlated with CAR surface expression, except at 100% v/v virus concentration, where expression of the construct without IRES-NGFR increased out of proportion to the transduction rate (Figure 5B), consistent with prior reports.15 The GD2 CD8a.4-1BB IRES-NGFR construct transduced with 100% v/v viral supernatant was expressed at a similar intermediate level to the construct without IRES-NGFR transduced with lower viral concentrations. This effect was specific for 4-1BB, as a GD2-CD8a.CD28 CAR achieved a similar transduction percentage but lower surface expression at high concentrations (Figure S5).

Figure 5.

GD2-4-1BB CAR antitumor activity can be optimized by lowering surface expression

(A) CAR architectures from GD2 screens were individually tested, and residual CHLA-255 tumor cells were measured after four cycles of repeated antigen stimulation. ∗∗∗p = 0.0001 and ∗∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0001, one-way ANOVA; n = 4. Data are represented as individual values and mean (horizontal line). (B) GD2-4-1BB CAR constructs with or without IRES-NGFR were transduced with 100%, 10%, or 1% v/v viral supernatant, and CAR MFI/transduction rate was evaluated at 10 days post-transduction. (C) CARs from (B) were exposed to five cycles of repeated antigen stimulation with CHLA-255 cells at an initial 1:2 effector/tumor ratio. Persisting CAR+ cells and residual tumor cells were simultaneously measured using flow cytometry. (D) PD-1/LAG3 immunofluorescence staining of T cells expressing 4-1BB CAR with or without IRES-NGFR transduced with 100%, 10%, or 1% virus v/v after three cycles of repeated antigen stimulation. Data are represented as mean ± SD. ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001 and ∗∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0001, two-way ANOVA; n = 4.

Intermediate CAR expression levels led to optimal antitumor activity regardless of the IRES-NGFR sequence, while the CAR with the highest surface expression mediated poor persistence and increased exhaustion of transduced cells (Figures 5C and 5D). To confirm that the improved activity of the IRES-NGFR construct was not sequence specific, we tested alternative bicistronic vector combinations and found that despite marginal differences in CAR surface expression, all constructs mediated comparable levels of antitumor activity (Figure S6). In addition, we found that CAR copy number was not significantly lower for the NGFR-IRES construct despite being a larger construct, suggesting an alternative mechanism for the decrease in surface expression at high virus concentrations (Figure S7). Taken together, these results suggest that our screen was able to identify CAR constructs with optimal expression levels, translating to lower levels of exhaustion and higher levels of antitumor activity.

Screen-selected GD2-CAR constructs mediate comparable levels of in vivo antitumor activity

Next, we evaluated the in vivo antitumor activity of T cells expressing the GD2-CAR with 4-1BB versus CD28 costimulatory domains. We transduced T cells with second-generation CAR constructs containing 4-1BB or CD28 and found that 4-1BB-mediated cell expansion was too low for in vivo testing, in part because of higher apoptosis levels from tonic signaling14,33 (Figures 6A and 6B). To overcome this, we tested different viral concentrations for transduction and found that a 10% v/v viral supernatant improved expansion of cells transduced with the 4-1BB CAR, although not to the same level as mediated by the CD28 CAR (Figure 6A). On the basis of this, we compared the 4-1BB CAR transduced at 10% v/v with the CD28 CAR at 100% v/v and infused the cells into NSG mice with metastatic neuroblastoma xenografts. We found that both CD28 and 4-1BB CARs mediated complete elimination of tumor progression in a model with a lower tumor burden, while the CD28 CAR mediated superior antitumor activity at a higher tumor dose (Figures 6C–6F). We included an additional group of mice treated with T cells expressing the third-generation CAR 4-1BB.CD28, another top construct identified in the GD2 screens. This construct mediated similar levels of antitumor activity to the second-generation 4-1BB CAR, further supporting the idea that the membrane-proximal costimulatory domain has a dominant effect.

Figure 6.

GD2 4-1BB CAR with optimized expression has potent in vivo antitumor activity

T cells transduced with 100%, 10%, or 1% v/v viral supernatant for constructs with either GD2 4-1BB or CD28 costimulation; after 10 days scFv+ cells (A) and annexin V+/DAPI+ cells (B) were counted. ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, and ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001, two-way ANOVA. Data are represented as mean ± SD. (C–F) NSG mice were injected intravenously with 1 × 106 (C and D) or 2 × 106 (E and F) luciferase-labeled CHLA-255 cells, then two weeks later received 2 × 106 CAR+ cells with CD28 transduced with 100% v/v viral supernatant and 4-1BB 10% v/v. Tumor growth was monitored using weekly bioluminescence imaging. Kaplan-Meier curves were generated from survival of animals in (C) and (E). ∗p = 0.0225 (log rank Mantel-Cox test).

Screen-selected CD19-CAR constructs mediate superior levels of in vivo antitumor activity

The CD19 screens yielded numerous known and novel CAR structures, and we selected a subset to characterize further. We evaluated CAR expression relative to the NGFR transduction marker in the bicistronic construct used in the screen and found that the CD28.4-1BB.CD28 CAR is expressed on fewer than 10% of transduced cells (Figure S8A), while the other constructs were expressed in more than 70% of cells. This supports the idea that the CD28 hinge is less functional in the absence of its transmembrane domain. Consistent with previous findings, we observed that the CD8a hinge mediates higher CAR surface expression compared with IgG4, with third-generation CARs having lower surface expression (Figure S8B). We further characterized these CARs in vitro, first assessing their proliferation as measured using CellTrace Violet dilution (Figure 7A). Consistent with the pooled screens, the CD28.4-1BB.CD28 CAR was the least proliferative, while 4-1BB.DAP12 was the most proliferative, although the differences were not statistically significant. Next, we evaluated in vitro persistence and antitumor activity and found that the IgG4.4-1BB and IgG4.4-1BB.CD28 CARs performed similarly to CD8a.4-1BB (structure of Kymriah), while IgG4.4-1BB.DAP12 and CD28.4-1BB.CD28 performed the worst (Figures 7B, 7C, and S9). Finally, we measured activation/exhaustion markers but do not find any significant differences between these CARs (Figure S10). These results suggest that persistence is a more reliable predictor of long-term antitumor activity than short-term proliferation and reinforce that our screen can detect known and novel CARs with therapeutic potential.

Figure 7.

Top hits from CD19 screen mediate superior in vivo antitumor activity

(A) CAR architectures from CD19 screens were individually tested, first stained with CellTrace Violet, and exposed to two cycles of antigen stimulation with Raji cells. (B) CD19-CARs were exposed to 11 cycles of antigen stimulation with Raji tumor cells at a 1:1 effector/tumor ratio every 2–3 days, then the area under the curve of the remaining CAR+ cells at the end of each cycle was calculated ( ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison; n = 4 donors). (C) Residual Raji cells after 11 cycles of tumor exposure (n = 4 donors). (D–F) NSG mice were injected intravenously with 1 × 106 luciferase-labeled CD19+ Daudi cells, then three days later received 2 × 106 CAR+ cells. Tumor growth was monitored by weekly bioluminescence imaging (D). (E) Monitoring tumor bioluminescence demonstrates both IgG4.4-1BB and IgG4.4-1BB.CD28 significantly reduce tumor progression compared with CD8a.4-1BB; ∗∗p < 0.01, two-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison. (F) Kaplan-Meier curve generated from survival of animals in (D) shows that IgG4.4-1BB leads to improved survival compared with CD8a.4-1BB; ∗p = 0.02 (log rank Mantel-Cox test).

To further assess the therapeutic potential of the top CARs identified in the CD19 screen, we used an in vivo metastatic Daudi NSG mouse model, treating with T cells transduced with IgG4.4-1BB, IgG4.4-1BB.CD28, or CD8a.4-1BB CARs. Surprisingly, both CD19-CARs with the IgG4.4-1BB architecture mediated better antitumor activity than the Kymriah construct as measured both by tumor bioluminescence and overall survival (Figures 7D–7F). We confirmed this result using CAR T cells from another donor, while noticing slight donor-dependent differences between IgG4.4-1BB and IgG4.4-1BB.CD28 (Figure S11). These results suggest that the hinge domain plays a critical role in enhancing in vivo activity, consistent with our findings from the pooled screening.

Discussion

This work describes a platform for identifying optimized CAR architectures, enabled by a novel blunt-end serial barcoded gene assembly strategy. Our CAR assembly method achieves a barcoding accuracy level of 70%–80%. Of note, the barcoding error rate only increased marginally after transducing the libraries, in contrast to prior reports,29,36 suggesting that recombination events might be specific to the construct and gene delivery system used. Moreover, we were able to assess up to 96% of expected library members despite having biases in domain distribution, a remarkable improvement over comparable methods.20

Our combinatorial screen shows that CAR domains are not modular, and their effects can vary depending on the context. For instance, the presence of the CD28 hinge had a negative impact on CAR surface expression and activity, likely due to the lack of its cognate transmembrane domain. Additionally, the effects of the CD8a and IgG4 hinge domains varied depending on the paired scFv. Shorter hinges lead to better activation and cytokine production,37 although certain antigens might require longer hinges for optimal cell activation and antitumor activity.38,39 The hinges included in our libraries were of similar lengths, indicating that factors other than size can influence hinge function. For example, we found that different scFv-hinge pairings elicit opposite effects on CAR cell surface expression and cytokine secretion. This is likely due to hinge-mediated receptor conformational changes influencing the multivariate activation dynamics downstream of T cell activation.40 Our work lays the groundwork for future screens where we can test a larger number of domains, including additional transmembrane domains such as CD28.

The top-performing CAR constructs identified in our GD2 screens featured the 4-1BB, CD28, and 4-1BB.CD28 costimulatory domains, along with the CD8a hinge. The latter two constructs have already demonstrated some activity in clinical trials,35,41 showing the translational potential of this approach. We show that low viral concentrations used for the pooled screening allow both robust expansion and antitumor activity of cells retrovirally transduced with 4-1BB CARs. Our results suggest there is a threshold level of CAR expression for triggering the deleterious LTR-mediated positive feedback loop previously described.15 The top-performing GD2 4-1BB CAR identified in our screen has a similar architecture to a CAR currently being evaluated in a phase I clinical trial for diffuse midline gliomas.35 Interestingly, expression of the CAR in the trial is controlled by a murine stem cell virus promoter, which likely mediates lower expression than our LTR-controlled CAR and allows adequate cell expansion. Optimization of CAR expression could improve expansion and antitumor activity of clinical cell therapy products, especially those that initially fail manufacturing.

The second-generation GD2 4-1BB and third-generation 4-1BB.CD28 CARs mediated similar in vivo antitumor activity. This finding aligns with the overall results from our expansion and proliferation screens, where 4-1BB had a dominant effect in the membrane-proximal position, as previously reported for the ICOS costimulatory domain.31 However, the CD28-containing GD2-CAR mediated the most potent antitumor activity in vivo compared with 4-1BB despite its relative lower performance in the pooled screens. This may be attributed to the higher levels of cytokine secretion induced by CD28,11 which is underestimated in pooled screening because of bystander effects. Furthermore, the secretion of cytokines such as IFN-γ is critical for antitumor activity against solid tumors,42 which could contribute to the superior in vivo performance mediated by the GD2 CD28 CAR. Our screening was limited to cell-intrinsic phenotypes such as persistence and proliferation rather than extrinsic factors such as cytokine secretion or cytotoxicity. Future screens that integrate results from multiple phenotypes such as cytokine production and in vivo persistence may enhance the pre-clinical predictive power of pooled CAR screening.

In the case of CD19, our testing demonstrated that the IgG4 hinge mediated superior in vivo antitumor activity compared with the clinically validated CD8a.4-1BB CAR architecture, an observation that initially emerged from the screen domain analysis. However, the IgG4 and CD8a hinge-containing CARs were individually compared in vitro, and no differences were detected between them. Pooled screening may be better suited for comparing different CAR architectures in some cases, as it may reduce the experimental variability compared with separately manipulating multiple constructs. This could be particularly true in complex, long-term experiments such as serial tumor challenges. The hinge domain can also be critical for in vivo activity; for example, the IgG4 hinge with the long CH2-CH3 spacer interacts with myeloid cells, leading to activation-induced T cell death and poor in vivo persistence.38 Future work is required to elucidate how the IgG4 short hinge used in our study mediates superior in vivo activity compared with CD8a.

In summary, our combinatorial pooled screening approach has generated new insights into CAR structural domains, in addition to novel architectures with improved antitumor activity in pre-clinical mouse models compared with known CAR constructs, underscoring the significance of screening full-length CARs. Moreover, systematic mapping of CAR domain interactions such as optimal scFv-hinge pairs can offer new design principles for iteratively improving CAR libraries. Our approach enables the study of CAR domain architectures with unprecedented detail and cost-effectiveness; once a combinatorial domain library is generated, it can be used to add any antigen-binding domain of interest, enabling the rapid development of optimized CARs targeting cancer antigens of interest. We envision that our approach could enable the development of more sophisticated CAR immunotherapy approaches, including dual or multi-specific CARs to prevent antigen escape or to selectively target tumor cells while sparing healthy tissues. Furthermore, this platform can be used to study other chimeric proteins and for DNA shuffling, thereby expanding the current toolset for protein engineering.

Materials and methods

Construct generation and library assembly

The pSTV28 plasmid (Takara Bio) was modified by addition of a zeocin selection marker and an N8 DNA barcode primer flanked by MfeI and EcoRI restriction sites, generating pSTV-BC. Domain subpools (Table S1) were codon-optimized, restriction sites were removed, and DNA fragments were synthesized using gBlocks (IDT). gBlocks were subcloned into pSTV-BC, and domain and barcode sequences were verified by Sanger sequencing, generating for each domain a plasmid with a single, unique barcode, except for CD3ζWT, which had five barcodes. Each domain subpool was first digested with either BbsI or BsaI (New England Biolabs) and heat-inactivated. Next, sticky ends were blunted with T4 polymerase and dNTPs (New England Biolabs), followed by purification using the Monarch PCR & DNA Cleanup Kit (New England Biolabs). The product was digested with either MfeI or EcoRI, then the subpool that provides the backbone was processed using Quick CIP (New England Biolabs) and the backbone and insert were gel-purified. The insert was ligated into the backbone using T4 Ligase (New England Biolabs), then 1 μL was transformed into 10-beta electrocompetent E. coli cells (New England Biolabs). Cells were plated onto LB agar plates with ampicillin and zeocin selection, colonies scraped, and plasmids extracted with GenElute HP Plasmid Maxiprep Kit (Sigma-Aldrich). These steps were repeated serially until full-length CARs were assembled. To synthesize third-generation CARs, the costimulatory domain was assembled twice. Barcoding accuracy was determined by comparing the CAR coding sequence to the expected barcode via Sanger sequencing of the CAR library from plasmids (A, n = 79), single cell Jurkat cell genomic DNA clones PCR (B, n = 43).

Cancer cell line culture

CD19+ Raji cells (a gift from Dr. Gianpietro Dotti) and CHLA-255 cells were stably transduced with a GFP construct and sorted to obtain pure populations. Raji and Daudi cells were maintained in RPMI-10 medium (RPMI-1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS] and 1% GlutaMAX; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and CHLA-255 cells in IMDM-20 (Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium [IMDM] with 20% FBS and 1% GlutaMAX). Cell lines were routinely STR-fingerprinted and tested for mycoplasma contamination.

Primary human T cell isolation and culture

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from buffy coats (Gulf Coast Regional Blood Center) with Ficoll and activated for 48 h using plate-bound OKT3 and anti-CD28 antibodies (BD Biosciences). Cells were then resuspended and used for retroviral transduction. T cells were maintained in RPMI-10 medium supplemented with 10 ng/mL IL-7 and 10 ng/mL IL-15, replenished every 48–72 hours.

Retrovirus production and transduction conditions

CAR libraries and individual CAR constructs were subcloned into empty SFG gammaretroviral vectors or SFG modified to include an IRES-NGFR sequence. 293T cells were co-transfected with SFG-CAR and packaging plasmids RD114 and pEQ-PAM3. Retrovirus supernatant was collected after 24 and 48 h, filtered with a 0.45 μM filter, and flash-frozen in an ethanol-dry ice bath. For transduction, non-tissue culture 24-well plates (Falcon) were coated with 7 μg/mL Retronectin (Takara Bio) overnight at 4°C. The plates were then washed, retrovirus supernatant was added, and plates were centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 1 h at room temperature. The supernatant was aspirated and activated T cells were added at 250,000 cells per well, followed by 10 min centrifugation at 1,000 × g. Transduced cells were expanded for 10 days prior to flow cytometry analysis and tumor co-culture assays.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Virus supernatant titer was assessed by serial dilution, and transduction efficiency was measured using NGFR staining. To assess exhaustion, CAR-T cells were stained with anti-scFv, PD-1, and LAG3 antibodies. Cell death was assessed by Annexin V-PE (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and DAPI staining. CAR surface expression was detected using anti-idiotype 1A7 for the GD2-CAR and anti-FMC63 (CustoScan) for the CD19-CAR. Samples were acquired on an IntelliCyt iQue Screener and analyzed using FlowJo version 10. Cell sorting was performed using a Sony SH800 sorter.

CD69 CAR-T cell activation assay

T cells or Jurkat cells were transduced with retroviral supernatant at low MOI (1:30 dilution), then 20 × 106 T cells transduced with the CAR library were co-cultured in a 6-well G-Rex plate (Wilson Wolf) with tumor cells in a 1:2 ratio (effector/tumor). After six hours (Jurkat) or 24 h (T), cells were stained with CD69, NGFR, and anti-scFv antibodies. CD69+/− cells were sorted using a Sony SH800 sorter.

Repeat antigen stimulation relative expansion

On day 10 post-transduction, 20 × 106 T cells transduced with CAR library were co-cultured in 6-well G-Rex plates with irradiated tumor cells 1:2 (effector/tumor) with 200 U/mL IL-2 supplementation every other day. Additional cycles of stimulation were performed with 40 × 106 irradiated tumor cells every 3–4 days for a total of four cycles for GD2 and six cycles for CD19. For individual CAR evaluations, 500,000 CAR+ T cells were co-cultured with 0.5 × 106 (Raji) or 1 × 106 (CHLA-255) tumor cells (non-irradiated, no IL-2 supplementation), then tumor cells were re-added after each cycle. Remaining tumor cells and CAR+ T cells were assessed by flow cytometry after staining with anti-scFv and DAPI and adding CountBright beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

CellTrace Violet proliferation screening

At day 10 post-transduction, 20 × 106 T cells transduced with CAR library were washed with PBS, then resuspended at 106 cells/mL to achieve a 1:1,000 dilution in CellTrace Violet. Cell suspensions were incubated in the dark for five minutes, RPMI-10 medium was added, and suspensions were transferred to a 6-well G-Rex plate. Irradiated tumor cells were added 1:2 (effector/tumor). Four days after adding tumors, a second cycle of stimulation was performed with 40 × 106 irradiated tumor cells. Three days later, cells were stained with anti-scFv and NGFR antibodies, and NGFR+ CellTrace Violet-high and CellTrace Violet-low cells were sorted using a Sony SH800 sorter.

Library sequencing and analysis

Genomic DNA from CAR-T cell donors was isolated using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (QIAGEN). Quantitative PCR was performed with the KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR Master Mix (Sigma-Aldrich) on a C1000 Touch Thermal Cycler with CFX96 Optical Reaction Module (Bio-Rad) using universal adapter primers. Sample amplification curves were monitored, and PCR was repeated while ensuring that cycle number remained in the exponential phase. Second rounds of both qPCR and PCR were performed using 1 μL of initial PCR product and sample-specific multiplex barcoded primers. Bands were gel-purified using the Monarch DNA Gel Extraction Kit (New England Biolabs) and quantified using a Qubit 4 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples were pooled at equimolar amounts and sequenced using Illumina HiSeq 2 × 150 bp dual index run averaging ∼13 million reads per donor per screen. When correcting sequencing errors, barcode conversions allowed for no more than one mismatch per 8 base barcode. For the initial testing of the CD19 library via CD69 activation, read counts were normalized per sample and ratios of CD69+ to CD69− reads were calculated for each CAR. For repeat antigen stimulation and CellTrace Violet dilution screens, four donor sample pairs for CD19 and GD2-CAR libraries were compared. DESeq2 was used to normalize reads and calculate fold change and p values comparing paired samples. For the CD3ζ WT versus mutant analysis, only CARs with >2,000 normalized reads and the expected scFv domain were analyzed. For the remaining CAR constructs, only full-length, CD3ζ WT CARs were analyzed. Graphs and group statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism 9.

IFNγ secretion

Culture supernatants were collected after 24 h of CAR-T cell co-culture with tumor cells, and IFNγ was measured using the Human IFN γ ELISA MAX Deluxe Set (BioLegend) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Absorbance was read in a Spark 10M Multimode Plate Reader (Tecan) at 450 nm wavelength.

CAR copy number analysis

Genomic DNA from four CAR-T cell donors was isolated using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (QIAGEN) 10 days after transduction. Primers specific for the anti-GD2 14g2a scFv were tested for efficiency via standard dilution, and specificity was determined using non-transduced control genomic DNA (Table S2). Standard curves were generated for both GD2 and RPL32. Quantitative PCR was performed with KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR Master Mix (Sigma-Aldrich) on a C1000 Touch Thermal Cycler with CFX96 Optical Reaction Module (Bio-Rad). Absolute copy numbers in samples were calculated using standard dilution curves from PCR products, and CAR copy number was calculated as GD2 copy number/(RPL32 copy number × 2).

In vivo mouse models

For neuroblastoma, NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice (8- to 10-week-old females; The Jackson Laboratory) were injected intravenously with 1 × 106 to 2 × 106 CHLA-255 cells engineered to express a FFluc-GFP fusion protein. Two weeks later, mice received a single intravenous injection of 2 × 106 CAR-T cells. For CD19+ lymphoma, mice were injected intravenously with 1 × 106 Daudi cells engineered to express a FFluc-GFP fusion protein. Three days later, mice received a single intravenous injection of 2 × 106 CAR-T cells. Tumor burden was monitored by recording luminescence on an IVIS Imaging system (Caliper Life Sciences). Mice were euthanized after displaying signs of high tumor burden or >10% weight loss. All animal experiments were conducted in compliance with Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) protocol AN-5194.

Data and code availability

The raw FASTQ files from NGS that support the findings of this study and additional data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the excellent technical assistance provided by the staff at the Flow Cytometry Core Laboratory of the Texas Children’s Cancer and Hematology Center and the Small Animal Imaging core facility at Texas Children’s Hospital. The authors would like to thank Dr. Maksim Mamonkin and Dr. Glenna Foight for their comments and discussion on the project. This work was supported by a grant from Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation for Childhood Cancer (to X.R.).

Author contributions

X.R., O.P., M.A.M., P.B., and Y.C. performed the molecular and immunologic experiments. C.Z. and P.S. developed computational approaches to analyze the NGS data. G.T. and G.A.B. contributed reagents and provided additional experimental support. L.G. performed the mouse injections and oversaw mouse experiments longitudinally. X.R. and L.S.M. wrote and E.J.D.P. edited the manuscript with contributions from all the authors.

Declaration of interests

X.R. and L.S.M. are co-inventors on provisional patent applications that relate to the method and resulting CARs described in this work.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.09.008.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Majzner R.G., Mackall C.L. Clinical lessons learned from the first leg of the CAR T cell journey. Nat. Med. 2019;25:1341–1355. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0564-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maude S.L., Frey N., Shaw P.A., Aplenc R., Barrett D.M., Bunin N.J., Chew A., Gonzalez V.E., Zheng Z., Lacey S.F., et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells for Sustained Remissions in Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:1507–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park J.H., Rivière I., Gonen M., Wang X., Sénéchal B., Curran K.J., Sauter C., Wang Y., Santomasso B., Mead E., et al. Long-Term Follow-up of CD19 CAR Therapy in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;378:449–459. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fesnak A.D., June C.H., Levine B.L. Engineered T cells: the promise and challenges of cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2016;16:566–581. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guedan S., Calderon H., Posey A.D., Maus M.V. Engineering and Design of Chimeric Antigen Receptors. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2019;12:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2018.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kershaw M.H., Westwood J.A., Darcy P.K. Gene-engineered T cells for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2013;13:525–541. doi: 10.1038/nrc3565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bridgeman J.S., Ladell K., Sheard V.E., Miners K., Hawkins R.E., Price D.A., Gilham D.E. CD3ζ-based chimeric antigen receptors mediate T cell activation via cis- and trans-signalling mechanisms: implications for optimization of receptor structure for adoptive cell therapy. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2014;175:258–267. doi: 10.1111/cei.12216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Stegen S.J.C., Hamieh M., Sadelain M. The pharmacology of second-generation chimeric antigen receptors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015;14:499–509. doi: 10.1038/nrd4597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensen M.C., Riddell S.R. Designing chimeric antigen receptors to effectively and safely target tumors. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2015;33:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srivastava S., Riddell S.R. Engineering CAR-T cells: Design concepts. Trends Immunol. 2015;36:494–502. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Majzner R.G., Rietberg S.P., Sotillo E., Dong R., Vachharajani V.T., Labanieh L., Myklebust J.H., Kadapakkam M., Weber E.W., Tousley A.M., et al. Tuning the antigen density requirement for CAR T-cell activity. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:702–723. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirobe S., Imaeda K., Tachibana M., Okada N. The Effects of Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) Hinge Domain Post-Translational Modifications on CAR-T Cell Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:4056. doi: 10.3390/ijms23074056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujiwara K., Tsunei A., Kusabuka H., Ogaki E., Tachibana M., Okada N. Hinge and Transmembrane Domains of Chimeric Antigen Receptor Regulate Receptor Expression and Signaling Threshold. Cells. 2020;9:1182. doi: 10.3390/cells9051182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Long A.H., Haso W.M., Shern J.F., Wanhainen K.M., Murgai M., Ingaramo M., Smith J.P., Walker A.J., Kohler M.E., Venkateshwara V.R., et al. 4-1BB costimulation ameliorates T cell exhaustion induced by tonic signaling of chimeric antigen receptors. Nat. Med. 2015;21:581–590. doi: 10.1038/nm.3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomes-Silva D., Mukherjee M., Srinivasan M., Krenciute G., Dakhova O., Zheng Y., Cabral J.M.S., Rooney C.M., Orange J.S., Brenner M.K., Mamonkin M. Tonic 4-1BB Costimulation in Chimeric Antigen Receptors Impedes T Cell Survival and Is Vector-Dependent. Cell Rep. 2017;21:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daniels K.G., Wang S., Simic M.S., Bhargava H.K., Capponi S., Tonai Y., Yu W., Bianco S., Lim W.A. Decoding CAR T cell phenotype using combinatorial signaling motif libraries and machine learning. Science. 2022;378:1194–1200. doi: 10.1126/science.abq0225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castellanos-Rueda R., Di Roberto R.B., Bieberich F., Schlatter F.S., Palianina D., Nguyen O.T.P., Kapetanovic E., Läubli H., Hierlemann A., Khanna N., Reddy S.T. speedingCARs: accelerating the engineering of CAR T cells by signaling domain shuffling and single-cell sequencing. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:6555. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34141-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodman D.B., Azimi C.S., Kearns K., Talbot A., Garakani K., Garcia J., Patel N., Hwang B., Lee D., Park E., et al. Pooled screening of CAR T cells identifies diverse immune signaling domains for next-generation immunotherapies. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022;14 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abm1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duong C.P.M., Westwood J.A., Yong C.S.M., Murphy A., Devaud C., John L.B., Darcy P.K., Kershaw M.H. Engineering T Cell Function Using Chimeric Antigen Receptors Identified Using a DNA Library Approach. PLoS ONE. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon K.S., Kyung T., Perez C.R., Holec P.V., Ramos A., Zhang A.Q., Agarwal Y., Liu Y., Koch C.E., Starchenko A., et al. Screening for CD19-specific chimaeric antigen receptors with enhanced signalling via a barcoded library of intracellular domains. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2022;6:855–866. doi: 10.1038/s41551-022-00896-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Roberto R.B., Castellanos-Rueda R., Frey S., Egli D., Vazquez-Lombardi R., Kapetanovic E., Kucharczyk J., Reddy S.T. A Functional Screening Strategy for Engineering Chimeric Antigen Receptors with Reduced On-Target, Off-Tumor Activation. Mol. Ther. 2020;28:2564–2576. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith E.L., Harrington K., Staehr M., Masakayan R., Jones J., Long T.J., Ng K.Y., Ghoddusi M., Purdon T.J., Wang X., et al. GPRC5D is a target for the immunotherapy of multiple myeloma with rationally designed CAR T cells. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019;11 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau7746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matreyek K.A., Starita L.M., Stephany J.J., Martin B., Chiasson M.A., Gray V.E., Kircher M., Khechaduri A., Dines J.N., Hause R.J., et al. Multiplex assessment of protein variant abundance by massively parallel sequencing. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:874–882. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0122-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi G.C.G., Zhou P., Yuen C.T.L., Chan B.K.C., Xu F., Bao S., Chu H.Y., Thean D., Tan K., Wong K.H., et al. Combinatorial mutagenesis en masse optimizes the genome editing activities of SpCas9. Nat. Methods. 2019;16:722–730. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0473-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogden P.J., Kelsic E.D., Sinai S., Church G.M. Comprehensive AAV capsid fitness landscape reveals a viral gene and enables machine-guided design. Science. 2019;366:1139–1143. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen X., Khericha M., Lakhani A., Meng X., Salvestrini E., Chen L.C., Shafer A., Alag A., Ding Y., Nicolaou D., et al. Rational Tuning of CAR Tonic Signaling Yields Superior T-Cell Therapy for Cancer. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.10.01.322990. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen X., Chen L.C., Khericha M., Meng X., Salvestrini E., Shafer A., Iyer N., Alag A.S., Ding Y., Nicolaou D.M., Chen Y.Y. Rational Protein Design Yields a CD20 CAR with Superior Antitumor Efficacy Compared with CD19 CAR. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2023;11:150–163. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-22-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heczey A., Liu D., Tian G., Courtney A.N., Wei J., Marinova E., Gao X., Guo L., Yvon E., Hicks J., et al. Invariant NKT cells with chimeric antigen receptor provide a novel platform for safe and effective cancer immunotherapy. Blood. 2014;124:2824–2833. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-541235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sack L.M., Davoli T., Xu Q., Li M.Z., Elledge S.J. Sources of Error in Mammalian Genetic Screens. G3 (Bethesda) 2016;6:2781–2790. doi: 10.1534/g3.116.030973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Y., Sun C., Landoni E., Metelitsa L., Dotti G., Savoldo B. Eradication of Neuroblastoma by T Cells Redirected with an Optimized GD2-Specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor and Interleukin-15. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;25:2915–2924. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guedan S., Posey A.D., Shaw C., Wing A., Da T., Patel P.R., McGettigan S.E., Casado-Medrano V., Kawalekar O.U., Uribe-Herranz M., et al. Enhancing CAR T cell persistence through ICOS and 4-1BB costimulation. JCI Insight. 2018;3 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.96976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salmikangas P., Kinsella N., Chamberlain P. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cells (CAR T-Cells) for Cancer Immunotherapy – Moving Target for Industry? Pharm. Res. 2018;35:152. doi: 10.1007/s11095-018-2436-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mamonkin M., da Silva D.G., Mukherjee M., Sharma S., Srinivasan M., Orange J.S., Brenner M.K. Tonic 4-1BB signaling from chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) impairs expansion of T cells due to Fas-mediated apoptosis. J. Immunol. 2016;196:143.7. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu X., Huang W., Heczey A., Liu D., Guo L., Wood M., Jin J., Courtney A.N., Liu B., Di Pierro E.J., et al. NKT cells co-expressing a GD2-specific chimeric antigen receptor and IL-15 show enhanced in vivo persistence and antitumor activity against neuroblastoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;25:7126–7138. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Majzner R.G., Ramakrishna S., Yeom K.W., Patel S., Chinnasamy H., Schultz L.M., Richards R.M., Jiang L., Barsan V., Mancusi R., et al. GD2-CAR T cell therapy for H3K27M-mutated diffuse midline gliomas. Nature. 2022;603:934–941. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04489-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roth T.L., Li P.J., Blaeschke F., Nies J.F., Apathy R., Mowery C., Yu R., Nguyen M.L.T., Lee Y., Truong A., et al. Pooled Knockin Targeting for Genome Engineering of Cellular Immunotherapies. Cell. 2020;181:728–744.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiao Q., Zhang X., Tu L., Cao J., Hinrichs C.S., Su X. Size-dependent activation of CAR-T cells. Sci. Immunol. 2022;7 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abl3995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hudecek M., Sommermeyer D., Kosasih P.L., Silva-Benedict A., Liu L., Rader C., Jensen M.C., Riddell S.R. The Nonsignaling Extracellular Spacer Domain of Chimeric Antigen Receptors Is Decisive for In Vivo Antitumor Activity. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015;3:125–135. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guest R.D., Hawkins R.E., Kirillova N., Cheadle E.J., Arnold J., O’Neill A., Irlam J., Chester K.A., Kemshead J.T., Shaw D.M., et al. The Role of Extracellular Spacer Regions in the Optimal Design of Chimeric Immune Receptors: Evaluation of Four Different scFvs and Antigens. [Miscellaneous Article] J. Immunother. 2005;28:203–211. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000161397.96582.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Achar S.R., Bourassa F.X.P., Rademaker T.J., Lee A., Kondo T., Salazar-Cavazos E., Davies J.S., Taylor N., François P., Altan-Bonnet G. Universal antigen encoding of T cell activation from high-dimensional cytokine dynamics. Science. 2022;376:880–884. doi: 10.1126/science.abl5311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heczey A., Courtney A.N., Montalbano A., Robinson S., Liu K., Li M., Ghatwai N., Dakhova O., Liu B., Raveh-Sadka T., et al. Anti-GD2 CAR-NKT cells in patients with relapsed or refractory neuroblastoma: an interim analysis. Nat. Med. 2020;26:1686–1690. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Larson R.C., Kann M.C., Bailey S.R., Haradhvala N.J., Llopis P.M., Bouffard A.A., Scarfó I., Leick M.B., Grauwet K., Berger T.R., et al. CAR T cell killing requires the IFNγR pathway in solid but not liquid tumours. Nature. 2022;604:563–570. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04585-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw FASTQ files from NGS that support the findings of this study and additional data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.