Highlights

-

•

TRPC5 induced papillary thyroid cancer metastasis and progression.

-

•

The HIF-1α/Twist pathway is involved in promoting the proliferation and invasion of papillary thyroid carcinoma.

Keywords: TRPC5, Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Proliferation, Invasion

Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to investigate the effect of TRPC5 on PTC (papillary thyroid carcinoma) proliferation and invasion.

Methods

Immunofluorescence and western blot were used to evaluate the expression of TRPC5 in paraffin sections and clinical tissues. Overexpression and silencing of TRPC5 to generate the cells for in vitro experiments. Wound-healing assay, transwell invasion assay, MTT assay, and in vivo tumorigenicity assay were used to determine cell proliferation and cell migration in vitro and in vivo. Real-time PCR was used to test the expression of TRPC5. Western blot was used to test the expression of downstream factors: E-cadherin, Vimentin, MMP-9, MMP-2, TRPC5, ZEB, Snail, and Twist.

Results

The level of TRPC5 protein expression was higher in PTC than in adjacent normal thyroid tissue. TPC-1 cells overexpressing TRPC5 were more proliferative, had longer migration distances, and increased the number of invading cells. TPC-1 cells silenced with TRPC5 had a weaker proliferation capacity, shorter migration distances, and a reduced number of invading cells. Overexpression and silencing of TRPC5 modulated E-cadherin, Vimentin, MMP-9, MMP-2, TRPC5, and Twist, but did not affect ZEB and Snail. The results of tumor formation experiments in nude mice showed that inhibition of TRPC5 expression suppressed the volume and weight of transplanted tumors.

Conclusion

TRPC5 induced papillary thyroid cancer metastasis and progression via up-regulated HIF-1α signaling in vivo and in vitro. High TRPC5 expression is a biomarker for lymph node metastasis at its early stages.

Introduction

Thyroid cancer is highly prevalent in the worldwide category and seriously affects the quality of life of patients [1,2]. There are four major types of thyroid cancer, namely papillary, follicular, medullary, and anaplastic, with papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) accounting for 85–90 % of all thyroid cancers. Along with the increased incidence, there was a significant increase in thyroid cancer incidence-based mortality in the last decade (approximately 1.1 % per year) for thyroid cancer patients and for those who were diagnosed with advanced-stage PTC or metastasized PTC (2.9 % per year) [3], [4], [5]. To date, several clinicopathological features predicting a poor prognosis of PTC patients have been identified, however, the molecular characteristics to distinguish aggressive PTC from indolent PTC are largely unknown. Lymph node metastasis of PTC was an important clinical feature of aggressive PTC [6]. It is known to occur in 5–25 % of patients and is the main cause of cancer-related death [7,8]. The mechanism for thyroid tumor metastasis is not entirely clear [9]. The mechanisms of thyroid tumourigenesis and metastasis are not fully understood. Therefore, an in-depth study of the mechanisms underlying the occurrence, development, and metastasis of PTC has important clinical value and social benefits for developing effective therapeutic measures and improving the survival rate of PTC.

TRPC5 is a member of the transient receptor potential (TRP) channel protein family, which is normally expressed exclusively in the brain [10]. As a calcium channel protein, TRPC5 transports extracellular free calcium into cells. The second messenger Ca2 + participates in the cell cycle, autophagy, apoptosis, and many other cell physiological processes [11]. It is the key factor to regulate cell migration. The TRP family has been reported that its various family members, such as TrpV2, TrpV1, and TrpM8 are involved in different human cancers [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]. Recently, it was reported that TRPC5 mediated HIF-1α to promote tumor angiogenesis in breast cancer [17]. However, the role of TRPC5 in PTC is still unknown.

In this study, we provide evidence that TRPC5 is associated with lymph node metastasis in PTC patients. First, we determined the expression of TRPC5 in clinical samples. Next, overexpression or silencing of TRPC5 in vitro to study the effect of TRPC5 on the behavioral profile of papillary thyroid cancer cells. Finally, a subcutaneous transplantation tumor model was established in nude mice to examine the effect of TRPC5 on the proliferation of papillary thyroid cancer cells in nude mice. What is more, a high level of TRPC5 promotes cell migration and proliferation through up-regulating HIF-1α, indicating it is a potential biomarker and therapeutic target in human PTC.

Materials and methods

Patients and ethics statement

Clinical samples used in the present study were obtained from the West China Hospital of Sichuan University. Focal and paracancerous tissues from patients were collected for immunofluorescence and western blot for basic medical studies. All the experiments involving animals and patients were in accordance with and approved by the Experimentation Ethics Committees of Sichuan University (2023–691), West China Hospital. We confirm that 5 patients gave written informed consent.

Experimental animals

The mice were fed freely in an specific pathogen free (SPF) laboratory under a 12-h cycle of light and dark. After one week of adaptive feeding, experimental mice were randomly divided into the control group and the sh-TRPC5 group. All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with animal management regulations of the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital (No. 2018133A).

Immunofluorescence assay

Papillary thyroid cancer tissues were collected from patients of West China Hospital. Papillary thyroid cancer tissues washed in saline, and fixed overnight in 4 % paraformaldehyde. Subsequently, the tissue was dehydrated through graded ethanol series. Next, the tissue was paraffin-embedded, and made into sections. The slides were then blocked with 2 % BSA (bovine albumin) for 30 min. After slides were washed, a primary antibody TRPC5 (1:300, ab306595, abcam, UK) was added and incubated overnight. After washing, the secondary antibody AlexaFluor-594 (1: 200, ab307167, abcam, UK) was added for 2 h. Then, the sections were washed three times with PBS for 5 min each time. Finally, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used for nuclear staining of the cells. The slides were observed and photographed with a DM2000 fluorescence microscope (Leica, Germany). The fluorescence area of the target protein TRPC5 (green) and the fluorescence area of DAPI (blue) was counted for the normalization method.

Cells and cell culture

The human PTC cell line TPC-1 used in our experiments was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. After the 3rd passage, the cells were used for experiments. The TPC-1 cell line with its modified cell lines were cultured in RAPI-1640 medium ((BI, Israel). The media was supplemented with 10 % FBS (fetal bovine serum), 100 μg/mL penicillin and 100 U/mL streptomycin at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 incubator.

Transfection assay

The lentivirus TRPC5 plasmid and the empty vector as control were purchased from Genechem (Shanghai Genechem Co., Ltd). All the procedures followed the instruction manuals. Small interfering RNA (si-RNA) duplexes kits designed to TRPC5, HIF-1α and Twist-1 (Table 1) were purchased from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. Cells were transfected with each siRNA using lipofectin 3000 (Invitrogen). After transfection for 48 h, cells were harvested and protein was isolated. 1 µL of the transfection reagent was diluted with 50 µL serum-free medium and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Diluted siRNA (base sequence) mixed with diluted transfection reagent was incubated at room temperature for 20 min to form the base sequence-liposome complexes. An 100 μL of base sequence-liposome complexes were directed to each well of the cell culture plate and the plate was then incubated at 37 °C, with 5 % CO2 for 24 ∼ 48 h.

Table 1.

Sequence of siRNA.

| Sequence (5′ → 3′) | ||

|---|---|---|

| si-TRPC5–1# | Sense | GAGAUCUACUAUAAUGUUAAC |

| Antisense | UAACAUUAUAGUAGAUCUCAG | |

| si-TRPC5–2# | Sense | GAGAGACGAUAAUAAUGAUGG |

| Antisense | AUCAUUAUUAUCGUCUCUCUG | |

| si-HIF-1α | Sense | CGAUGGAAGCACUAGACAAAG |

| Antisense | UUGUCUAGUGCUUCCAUCGGA | |

| si-Twist-1 | Sense | GGUACAUCGACUUCCUCUACC |

| Antisense | UAGAGGAAGUCGAUGUACCUG | |

Transwell invasion assay

A 0.25 % trypsin-EDTA solution with a cell density of 2 × 105/ml was used to harvest the cells. On the upper chamber membrane, 50 μl (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) of Matrigel was applied and solidified at 37 °C for 30 min. A 24-well plate was filled with 600 μl of complete medium with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), 100 μl of cell suspension was seeded on the membrane, and the plate was then incubated at 37 °C in a humidified air and 5 % CO2 environment. Transwells were collected 24 h after incubation, preserved for 30 min in −20 °C cold methanol, and then stained for 20 min at room temperature with 0.5 % crystal violet (Solarbio, Beijing, China). Under an optical microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), invasive cells were seen.

Wound-healing assay

TPC-1 cells were seeded into 12-well plates and cultured till the confluence reached 90 %. A scratch was generated with a sterile pipet tip followed by several washes to remove dislodged cells. The cells were cultured in 2 % FBS for 24 h. The width of the wound was recorded photographically every 12 h.

MTT assay

Each group of cells was seeded into 96-well plates at 5000 cells/well. Cells were incubated for 2 days, and then 10 μL MTT (5 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added. Absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a plate reader (Thermo Labsystems Multiskan MK3; Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA).

Real-time PCR

The expression of mRNA was analyzed by real-time PCR. Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen) and reverse transcribed into cDNA using a Reverse Transcriptase M-MLV (RNase H-) kit (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR were performed SsoFast supermix (Bio-rad) according to manufactors’ instructions. The primer pairs for β-actin were forward TGGAGTCCACTGGCGTCTTC, reverse GCTTGACAAAGTGGTCGTTGAG; and for TRPC5 forward CCACCAGCTATCAGATAAGG, reverse CGAAACAAGCCACTTATACCC.

Western blot

Total proteins of cells were obtained using RIPA lysis buffer with proteinase inhibitor cock-tail (Roche). Proteins were separated on a 10 % SDS-PAGE gel and then transferred to PVDF membranes. After blocking in 5 % non-fat milk at room temperature for 1 h, the membranes were incubated with designated primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. After completing the incubation of the primary antibody, the PVDF membrane was washed, and incubated the secondary antibody. Protein bands were visualized with an ECL kit. Images were collected and analyzed using the QuantityOne system. Antibody information: anti-E-cadherin (1:1000, ab231303, abcam, UK), anti-Vimentin (1: 800, ab92547, abcam, UK), anti-MMP-9 (1: 1000, ab76003, abcam, UK), anti-MMP-2 (1: 1000, ab92536, abcam, UK), anti-TRPC5 (1:500, ab240872, abcam, UK), anti-ZEB (1:1000, ab203829, abcam, UK), anti-Snail (1: 500, ab216347, abcam, UK), and anti-Twist (1:1000, ab50887, abcam, UK).

In vivo tumorigenicity assay

Females nude mice (n = 6), 5–8 weeks old, and 16–18 g were purchased from Dashuo Biological Technology (Chengdu, China). The TRPC5 knockdown (a small hairpin RNA or short hairpin RNA, sh-TRPC5) low stable transient TPC-1 cell line and the empty plasmid cell line were constructed as controls. A single-cell suspension was prepared using logarithmic growth phase TPC-1 cells at a cell density of approximately 1 × 107 cells/mL. 0.1 mL (approximately 1 × 106 cells) of the cell suspension was inoculated into the right axilla of nude mice to establish a mouse model of a subcutaneous ectopic transplantation tumor. All mice were fed in FPS conditions. The growth of the tumor was monitored every 7 days with digital calipers. sh-TRPC5 (sc-42,670-V) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.

Immunohistochemical staining

All the tissue blocks were collected and cut into paraffin sections. All the performances followed the standard protocol. The slides were incubated with the primary antibody (TRPC5 1:1000; Ki67 1: 1000) at 4 °C in a humidified chamber overnight and then treated with the GTVision III Detection System/Mo & Rb kit (gene Tech Co., Ltd). Antibody information is anti- TRPC5 (ab306595, abcam, UK), anti-Ki67 (ab15580, abcam, UK)

Statistical analyses

SPSS 22.0 software was used for the statistical analysis of the data. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation ( ± s), T test was used for comparison of means between groups, one-way ANOVA was used for comparison between multiple groups, and P < 0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference.

Results

Expression of TRPC5 in papillary thyroid cancer tissues

The expression of TRPC5 protein levels in papillary thyroid cancer samples was examined using immunofluorescence techniques, with TRPC5 being marked by green fluorescence. Compared with paracancerous tissues, dense green fluorescence was seen in cancerous tissue with densely overlapping cancer cell nuclei (Fig. 1A and B). In addition, western blot assays also showed that TRPC5 was expressed at higher levels in cancerous tissue than in paracancerous tissues (Fig. 1C and D). These experimental results imply that the overproliferation of PTC may be associated with TRPC5.

Fig. 1.

TRPC5 is highly expressed in papillary thyroid cancer tissues. A-B: Immunofluorescence detection of TRPC5 protein levels in papillary thyroid cancer tissues and adjacent normal tissues. C-D: Western blot to detect TRPC5 protein levels in papillary thyroid cancer tissues and adjacent normal tissues. T-test was used for expression differences between the two groups, # p < 0.05, ## p ˂ 0.001.

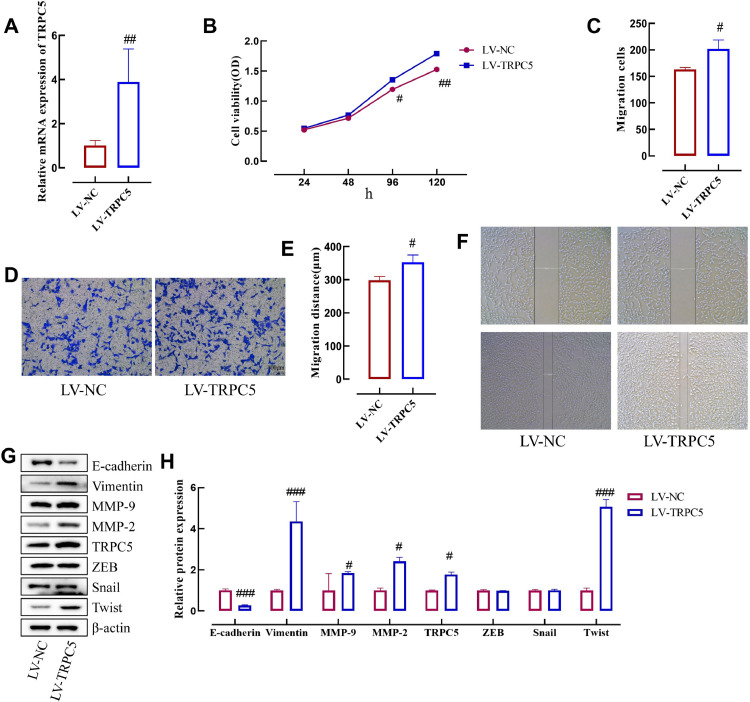

Overexpression of TRPC5 affects the behavior of TPC-1 cells

To investigate the role of TRPC5 in the development of PTC, we used a lentiviral vector to construct a cell line (TPC-1) overexpressing TRPC5. RT-qPCR showed that LV-TRPC5 induced mRNA levels of TRPC5 compared to the no-load group (LV-NC) (Fig. 2A). The results of the cell activity assay lasting 120 h showed that cells with LV-TRPC5 induced overexpression of TRPC5, were more viable and had a higher cell proliferation capacity after 48 h (Fig. 2B). The number of cell invasions was significantly increased in the LV-TRPC5 group compared to the LV-NC group, indicating that overexpression of TRPC5 induced tumor invasion (Fig. 2C and D). The rate of migration of TRPC5 overexpressing cells was significantly faster compared with the LV-NC group, suggesting that overexpression of TRPC5 induced tumor migration (Fig. 2E and F). Western blot results showed that LV-TRPC5 induced the expression of Vimentin, MMP-2, TRPC5, and Twis and inhibited E-cadherin compared to the LV-NC group, with no significant effect on ZEB and Snail (Fig. 2G and H). In conclusion, overexpression of TRPC5 can affect the behavior of TPC-1 cells by affecting proliferation and migration proteins.

Fig. 2.

Overexpression of TRPC5 induces proliferation of TPC-1 cells. A: Expression of TRPC5 mRNA. B: Effect of overexpression of TRPC5 on the viability of TPC-1 cell. C-D: Overexpressed TRPC5 affects transwell migration. E-F: Overexpression of TRPC5 affects cell migration distance (50 ×). G-H: Effects of overexpression of TRPC5 on E-cadherin, Vimentin, MMP-2, TRPC5, ZEB, Snail, and Twist. T-test was used for expression differences between the two groups, # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.001, ### p ˂ 0.0001.

Silencing of TRPC5 affects the behavior of TPC-1 cells

To measure the role of TRPC5 silencing in TPC-1 cells, we established a TRPC5-silenced TPC-1 cell model using si-TRPC5–1# and si-TRPC5–2# and evaluated it by RT-qPCR. The results showed that compared with the si-NC group, si-TRPC5–1# and si-TRPC5–2# inhibited the mRNA levels of TRPC5 (Fig. 3A). The results of the MTT cell viability assay showed that si-TRPC5–1# and si-TRPC5–2# were able to inhibit the cell viability and cell proliferation rate of TPC-1 cells after 48 h compared with the si-NC group (Fig. 3B). In addition, si-TRPC5–1# and si-TRPC5–2# inhibited the migration number of TPC-1 cells (Fig. 3C and D) and also the migration distance (Fig. 3E and F) compared with the si-NC group. Western blot assay results showed that si-TRPC5–1# and si-TRPC5–2# had opposite effects on LV-TRPC5. Compared to the si-NC group, the si-TRPC5–1# and si-TRPC5–2# inhibted the expression of Vimentin, MMP-2, TRPC5, and Twis and induced E-cadherin, with no significant effect on ZEB and Snail (Fig. 3G and H). Based on these results we found that si-TRPC5–1# and si-TRPC5–2# had comparable effects on the behavior of TPC-1 cells and that silencing of TRPC5 inhibited the proliferation of TPC-1 cells.

Fig. 3.

Silencing TRPC5 inhibits TPC-1 cell proliferation. A: Expression of TRPC5 mRNA. B: Effect of Silencing of TRPC5 on the viability of TPC-1 cell. C-D: Overexpressed TRPC5 affects transwell migration. E-F: Silencing of TRPC5 affects cell migration distance (50 ×). G-H: Effects of Silencing of TRPC5 on E-cadherin, Vimentin, MMP-9, MMP-2, TRPC5, ZEB, Snail, and Twist. # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.001, ### p ˂ 0.0001, versus si-NC group.

TRPC5 regulates the HIF-1α-Twist pathway to affect papillary thyroid cancer cells

To investigate the behavioral effects of HIF-1α-Twist on TPC-1, si-TRPC5–1#, si-HIF1-α, and si-Twist were selected as the subjects. The results of the cell activity assay showed that si-TRPC5–1#, si-HIF1-α, and si-Twist inhibited the proliferative activity of TPC-1 compared to the control (si-NC) group (Fig. 4A). As shown in Fig. 4B and C, si-TRPC5–1#, si-HIF1-α, and si-Twist inhibited the migration distance of TPC-1 compared with the control group. Transwell migration experiments showed that si-TRPC5–1#, si-HIF1-α, and si-Twist inhibited the migration distance of TPC-1 (Fig. 4D and E). Western blot assays showed that si-TRPC5–1# inhibited TRPC5, si-HIF1-α inhibited HIF1-α, and si-Twist inhibited Twist. In addition, si-TRPC5–1#, si-HIF1-α, and si-Twist induced Vimentin expression compared to the control group (Fig. 4F and G). From the above experimental results, it was found that si-TRPC5–1#, si-HIF1-α, and si-Twist all had similar effects on TPC-1.

Fig. 4.

si-TRPC5–1# affects PTC growth via the HIF-1α-Twist pathway. A: si-TRPC5–1#, si-HIF1-α, si-Twist affect TPC-1 cell viability. B-C: si-TRPC5–1#, si-HIF1-α, si-Twist affect the migration distance of TPC-1 cells (50 ×). d-E: si-TRPC5–1#, si-HIF1-α, si-Twist affect transwell migration. F-G: Changes in TRPC5, HIF1-α, Twist, and Vimentin proteins. #p<0.05, ##p<0.01, versus control group.

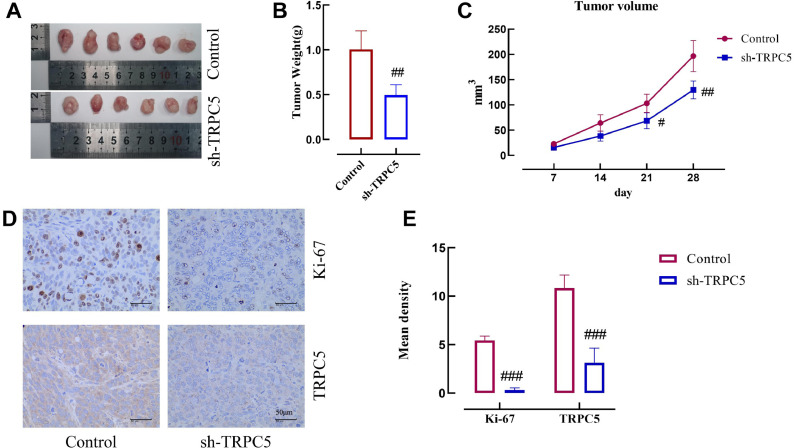

Effect of TRPC5 on PTC transplantation tumours

The effect of stable interference with TRPC5 on the proliferation of PTC was further validated using subcutaneous tumor formation assays in nude mice. As shown in Fig. 5A and B, the sh-TRPC5-interfered group showed slower tumor growth and smaller tumor mass compared with the control group. The growth curve of the tumor volume in nude mice clearly showed that the tumor bodies of TPC-1 cells with knockdown TRPC5 grew slowly (Fig. 5C). In addition, sh-TRPC5 inhibited the expression of TRPC5 and Ki67 compared with the control group. Ki67 is a proliferating cell-associated protein whose function is closely linked to mitosis and is indispensable in cell proliferation [18]. Based on the above, this suggests that in nude mice sh-TRPC5 retards tumor growth by inhibiting the TRPC5 pathway.

Fig. 5.

sh-RNA of TRPC5 inhibits the growth of PTC transplantation tumors. A: Image of the transplanted tumor. B: Statistics of transplanted tumor volume. C: Weight change of transplanted tumor mice. D: Ki67 and TRPC5 expression in the transplanted tumor. E: Ki67 and TRPC5 expression statistical results. T-test was used for expression differences between the two groups, # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.001, ### p < 0.0001.

Discussion

The diagnosis and treatment of PTC is still a hot topic, and the diagnosis of invasive PTC still faces difficulties [19]. Here, we demonstrate that TRPC5 is highly expressed in PTC. Besides, we found that TRPC5 overexpression leads to cell migration and proliferation in vitro and in vivo by up-regulating HIF-1α signaling. As far as we know, this is the first study to show that TRPC5 implicates lymph node metastasis in human papillary carcinoma.

On one hand, PTC is one of the most friendly malignant tumors, with a five-year survival rate of 96 % and a 10-year survival rate of 93 % [20]. Most PTCs remain small for a long time and co-exist with the host for a long time. Surgery and radioiodine therapy are effective treatments for well-differentiated thyroid carcinomas, however, there are restrictions when applied to ATC (anaplastic thyroid carcinoma) and radioiodine-resistant PTC [21]. In addition to lifelong thyroxine supplementation after total thyroidectomy, there may also be complications related to surgery that damage the parathyroid gland and recurrent laryngeal nerve [22]. Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury is one of the most common serious complications of thyroid surgery, which causes hoarseness in patients [23]. In severe cases, tracheotomy and even lifelong tracheostomy is necessary, which seriously affects the quality of life, and even endangers their lives of the patients. In addition, temporary or permanent hypoparathyroidism caused by surgery requires temporary or long-term intravenous calcium supplementation, which also seriously affects the daily work and life of patients undergoing surgery [21].

On the other hand, not all PTCs are low-risk cancer. It is found that some PTCs have all the characteristics of malignant tumors, such as metastasis, recurrence, and life-threatening. There are also some PTCs with obvious invasiveness, which can invade the thyroid capsule and surrounding tissues. In the early stage, there will be regional lymph node metastasis or even distant metastasis [24], [25], [26], threatening the life of patients. At present, there is no reliable method at home and abroad to accurately judge the invasion and prognosis of PTC before the operation, nor to predict which PTC will cause greater harm to patients, which needs timely treatment. Therefore, the ideal strategy is to screen PTC effectively, observe the inert PTC, and operate the highly invasive PTC in time. In this study, we determined the positive significance of blocking TRPC5 on PTC. TRPC5 was reported to be involved in glucose and lipid metabolism, and blocking TRPC5 may affect the body's glucose and lipid metabolism function [27].

Up to now, it is generally accepted that BRAFV600E (proto-oncogene) has a good negative predictive value, but the positive likelihood value is poor [28,29], that is to say, the patients with BRAFV600E negative have a high probability of low invasive thyroid cancer, but the positive BRAFV600E may not represent the patients with high invasive thyroid cancer. Therefore, BRAFV600E can be used as the diagnostic basis for inert thyroid cancer, but it can not be screened out for High-risk patients with highly invasive PTC [30], [31], [32].

In the present study, based on clinical samples we found that TRPC5 was highly expressed in cancer tissues, with statistically significant results when compared to paracancerous tissues. This implies that TRPC5 may be associated with the metastasis and progression of PTC. Interference with TRPC5 tumor growth in the animal in vivo experiments further suggests that TRPC5 is associated with the growth of papillary thyroid cancer cells. Sh-TRPC5 silences TRPC5 in animals while also suppressing Ki67 expression. Clinically, Ki67 is mainly used to mark cells in the proliferation cycle, and the higher the mark (+) rate, the faster the tumor growth [33]. Overexpression of TRPC5 in papillary thyroid cancer cells was shown to promote proliferation, migration, and invasion of cancer cells, and inhibition of TRPC5 expression also inhibited the ability of cancer cells to proliferate. Further protein assays showed that E-cadherin, Vimentin, MMP-9, and MMP-2 are involved in the behavioral processes of TPC-1 cells. E-cadherin is a tumor suppressor protein. Decreased expression of E-cadherin and increased expression of N-cadherin are the most representative molecular features of the cellular process of EMT (epithelial to mesenchymal transition) [34,35]. Previous studies have reported that inhibition of PLK1 can regulate MMP-2 and MMP-9 to suppress cell invasion in undifferentiated thyroid cancer. In addition, Wen-jing Zhang reported high expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in the peripheral blood of thyroid cancer patients [36]. ZEB [37] and Snail [38] have also been reported to be involved in the cellular EMT process. These have also been observed in thyroid carcinoma.

HIF-1α signal pathway can also communicate with multiple signal pathways in vivo, such as STAT3, RAS, Akt, Wnt, and other signal transduction pathways that can activate other oncogenic pathways or transcript factors [39], [40], [41]. HIF-1α can affect the proliferation and migration of tumor cells in many ways, such as HIF-1α induced neovascularization, extracellular matrix degradation, and bone marrow-derived cell aggregation, leading to the proliferation, invasion, and metastasis of cancer cells [42,43]. In addition, HIF-1α directly binds to and upregulates the expression of TWIST-1, an important basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor that plays an important role in the induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumor invasion and metastasis [44]. Tumor metastasis refers to the gradual acquisition of the ability of primary tumor cells to invade deeper tissues through the mucosa. Tumor cells in situ increase their invasiveness through the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process, invade surrounding tissues, migrate to blood vessels or lymphatic vessels, pass out of blood vessels, and enter the circulation system, becoming circulating tumor cells (CTCs) [45]. The process of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) can give cells many abilities such as migration and invasion, stronger survival, stem cell properties, and immune suppression. With these skills, they can metastasize [46]. Therefore, our findings suggest that TRPC5 is a regulatory factor of the HIF-1α signaling pathway in PTC, suggesting that TRPC5 may be a potential therapeutic target site for PTC.

Conclusion

Taken together, the results show that TRPC5 is highly expressed in papillary thyroid cancer tissues. Our experimental results suggest that TRPC5 protein is involved in the proliferation, metastasis, and invasion of papillary thyroid cancer cells, and that inhibition of TRPC5 protein can inhibit tumor development, but the mechanism by which TRPC5 protein affects the biological activity of papillary thyroid cancer cells needs to be confirmed by further studies.

Author contributions statement

All authors were involved in the experiments and the writing of the paper.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Support Program of Chengdu Science and Technology Agency (grant no. 2022-YF05-01447-SN). Key Research Project of Social Development Department of Sichuan Science and Technology Agency (grant no. 2022YFS0110). Popular Application Project of Health Commission of Sichuan Province (grant no. 21PJ045).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Zhang P., Guan H., Yuan S., Cheng H., Zheng J., Zhang Z., Liu Y., Yu Y., Meng Z., Zheng X., Zhao L. Targeting myeloid derived suppressor cells reverts immune suppression and sensitizes BRAF-mutant papillary thyroid cancer to MAPK inhibitors. Nat. Commun. 2022;13(1):1588. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29000-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang X., Zhang F., Li Q., Aihaiti R., Feng C., Chen D., Zhao X., Teng W. The relationship between urinary iodine concentration and papillary thyroid cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.1049423. (Lausanne) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sipos J.A., Mazzaferri E.L. Thyroid cancer epidemiology and prognostic variables. Clin. Oncol. (R. Coll. Radiol.) 2010;22(6):395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee Y.S., Lim Y.S., Lee J.C., Wang S.G., Kim I.J., Lee B.J. Clinical implication of the number of central lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid carcinoma: preliminary report. World J. Surg. 2010;34(11):2558–2563. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0749-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim H., Devesa S.S., Sosa J.A., Check D., Kitahara C.M. Trends in thyroid cancer incidence and mortality in the United States, 1974-2013. JAMA. 2017;317(13):1338–1348. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krishnan A., Berthelet J., Renaud E., Rosigkeit S., Distler U., Stawiski E., Wang J., Modrusan Z., Fiedler M., Bienz M., Tenzer S., Schad A., Roth W., Thiede B., Seshagiri S., Musholt T.J., Rajalingam K. Proteogenomics analysis unveils a TFG-RET gene fusion and druggable targets in papillary thyroid carcinomas. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):2056. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15955-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlumberger M., Tubiana M., De Vathaire F., Hill C., Gardet P., Travagli J.P., Fragu P., Lumbroso J., Caillou B., Parmentier C. Long-term results of treatment of 283 patients with lung and bone metastases from differentiated thyroid carcinoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1986;63(4):960–967. doi: 10.1210/jcem-63-4-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durante C., Haddy N., Baudin E., Leboulleux S., Hartl D., Travagli J.P., Caillou B., Ricard M., Lumbroso J.D., De Vathaire F., Schlumberger M. Long-term outcome of 444 patients with distant metastases from papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma: benefits and limits of radioiodine therapy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006;91(8):2892–2899. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hilton J.K., Rath P., Helsell C.V., Beckstein O., Van Horn W.D. Understanding thermosensitive transient receptor potential channels as versatile polymodal cellular sensors. Biochemistry. 2015;54(15):2401–2413. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thakore P., Brain S.D., Beech D.J. Correspondence: challenging a proposed role for TRPC5 in aortic baroreceptor pressure-sensing. Nat. Commun. 2018;9(1):1245. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02703-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venkatachalam K., Montell C. TRP channels. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007;76:387–417. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waning J., Vriens J., Owsianik G., Stüwe L., Mally S., Fabian A., Frippiat C., Nilius B., Schwab A. A novel function of capsaicin-sensitive TRPV1 channels: involvement in cell migration. Cell Calcium. 2007;42(1):17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monet M., Gkika D., Lehen'kyi V., Pourtier A., Vanden Abeele F., Bidaux G., Juvin V., Rassendren F., Humez S., Prevarsakaya N. Lysophospholipids stimulate prostate cancer cell migration via TRPV2 channel activation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1793(3):528–539. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monet M., Lehen'kyi V., Gackiere F., Firlej V., Vandenberghe M., Roudbaraki M., Gkika D., Pourtier A., Bidaux G., Slomianny C., Delcourt P., Rassendren F., Bergerat J.P., Ceraline J., Cabon F., Humez S., Prevarskaya N. Role of cationic channel TRPV2 in promoting prostate cancer migration and progression to androgen resistance. Cancer Res. 2010;70(3):1225–1235. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-09-2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wondergem R., Ecay T.W., Mahieu F., Owsianik G., Nilius B. HGF/SF and menthol increase human glioblastoma cell calcium and migration. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;372(1):210–215. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wondergem R., Bartley J.W. Menthol increases human glioblastoma intracellular Ca2+, BK channel activity and cell migration. J. Biomed. Sci. 2009;16(1):90. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-16-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu Y., Pan Q., Meng H., Jiang Y., Mao A., Wang T., Hua D., Yao X., Jin J., Ma X. Enhancement of vascular endothelial growth factor release in long-term drug-treated breast cancer via transient receptor potential channel 5-Ca(2+)-hypoxia-inducible factor 1α pathway. Pharmacol. Res. 2015;93:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guarneri V., Dieci M.V., Bisagni G., Frassoldati A., Bianchi G.V., De Salvo G.L., Orvieto E., Urso L., Pascual T., Paré L., Galván P., Ambroggi M., Giorgi C.A., Moretti G., Griguolo G., Vicini R., Prat A., Conte P.F. De-escalated therapy for HR+/HER2+ breast cancer patients with Ki67 response after 2-week letrozole: results of the PerELISA neoadjuvant study. Ann. Oncol. 2019;30(6):921–926. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies L., Welch H.G. Current thyroid cancer trends in the United States. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2014;140(4):317–322. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lubitz C.C., Sosa J.A. The changing landscape of papillary thyroid cancer: epidemiology, management, and the implications for patients. Cancer. 2016;122(24):3754–3759. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ElMokh O., Ruffieux-Daidié D., Roelli M.A., Stooss A., Phillips W.A., Gertsch J., Dettmer M.S., Charles R.P. Combined MEK and Pi3′-kinase inhibition reveals synergy in targeting thyroid cancer in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget. 2017;8(15):24604–24620. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma S.H., Liu Q.J., Zhang Y.C., Yang R. Alternative surgical strategies in patients with sporadic medullary thyroid carcinoma: long-term follow-up. Oncol. Lett. 2011;2(5):975–980. doi: 10.3892/ol.2011.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yin Q., Liu H., Song Y., Zhou S., Yang G., Wang W., Qie P., Xun X., Liu L. Clinical application and observation of single-port inflatable mediastinoscopy combined with laparoscopy for radical esophagectomy in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2020;15(1):125. doi: 10.1186/s13019-020-01168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orita Y., Sugitani I., Matsuura M., Ushijima M., Tsukahara K., Fujimoto Y., Kawabata K. Prognostic factors and the therapeutic strategy for patients with bone metastasis from differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Surgery. 2010;147(3):424–431. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Croucher P.I., McDonald M.M., Martin T.J. Bone metastasis: the importance of the neighbourhood. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2016;16(6):373–386. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Godbert Y., Henriques-Figueiredo B., Cazeau A.L., Carrat X., Stegen M., Soubeyran I., Bonichon F. A papillary thyroid microcarcinoma revealed by a single bone lesion with no poor prognostic factors. Case Rep. Endocrinol. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/719304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang T., Ning K., Sun X., Zhang C., Jin L.F., Hua D. Glycolysis is essential for chemoresistance induced by transient receptor potential channel C5 in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):207. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4123-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McFadden D.G., Vernon A., Santiago P.M., Martinez-McFaline R., Bhutkar A., Crowley D.M., McMahon M., Sadow P.M., Jacks T. p53 constrains progression to anaplastic thyroid carcinoma in a Braf-mutant mouse model of papillary thyroid cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A, 2014;111(16):E1600–E1609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404357111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X.J., Mao X.D., Chen G.F., Wang Q.F., Chu X.Q., Hu X., Ding W.B., Zeng Z., Wang J.H., Xu S.H., Liu C. High BRAFV600E mutation frequency in Chinese patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma increases diagnostic efficacy in cytologically indeterminate thyroid nodules. Medicine. 2019;98(28):e16343. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000016343. (Baltimore) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu C., Chen T., Liu Z. Associations between BRAF(V600E) and prognostic factors and poor outcomes in papillary thyroid carcinoma: a meta-analysis. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2016;14(1):241. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-0979-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim T.H., Park Y.J., Lim J.A., Ahn H.Y., Lee E.K., Lee Y.J., Kim K.W., Hahn S.K., Youn Y.K., Kim K.H., Cho B.Y., Park D.J. The association of the BRAF(V600E) mutation with prognostic factors and poor clinical outcome in papillary thyroid cancer: a meta-analysis. Cancer. 2012;118(7):1764–1773. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim S.J., Lee K.E., Myong J.P., Park J.H., Jeon Y.K., Min H.S., Park S.Y., Jung K.C., Koo do H., Youn Y.K. BRAF V600E mutation is associated with tumor aggressiveness in papillary thyroid cancer. World J. Surg. 2012;36(2):310–317. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1383-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen X., Zhang M., Gan H., Wang H., Lee J.H., Fang D., Kitange G.J., He L., Hu Z., Parney I.F., Meyer F.B., Giannini C., Sarkaria J.N., Zhang Z. A novel enhancer regulates MGMT expression and promotes temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma. Nat. Commun. 2018;9(1):2949. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05373-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li L., Li W. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human cancer: comprehensive reprogramming of metabolism, epigenetics, and differentiation. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015;150:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pasquier J., Abu-Kaoud N., Al Thani H., Rafii A. Epithelial to Mesenchymal transition in a clinical perspective. J. Oncol. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/792182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang X.G., Lu X.F., Jiao X.M., Chen B., Wu J.X. PLK1 gene suppresses cell invasion of undifferentiated thyroid carcinoma through the inhibition of CD44v6, MMP-2 and MMP-9. Exp. Ther. Med. 2012;4(6):1005–1009. doi: 10.3892/etm.2012.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vandewalle C., Comijn J., De Craene B., Vermassen P., Bruyneel E., Andersen H., Tulchinsky E., Van Roy F., Berx G. SIP1/ZEB2 induces EMT by repressing genes of different epithelial cell-cell junctions. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2005;33(20):6566–6578. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bao Z., Zeng W., Zhang D., Wang L., Deng X., Lai J., Li J., Gong J., Xiang G. SNAIL induces EMT and lung metastasis of tumours secreting CXCL2 to promote the invasion of M2-type immunosuppressed macrophages in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022;18(7):2867–2881. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.66854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen S., Chen J.Z., Zhang J.Q., Chen H.X., Yan M.L., Huang L., Tian Y.F., Chen Y.L., Wang Y.D. Hypoxia induces TWIST-activated epithelial-mesenchymal transition and proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells in vitro and in nude mice. Cancer Lett. 2016;383(1):73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thiery J.P., Acloque H., Huang R.Y., Nieto M.A. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139(5):871–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mittal V. Epithelial mesenchymal transition in tumor metastasis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2018;13:395–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020117-043854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu Q., DeFusco P.A., Ricci A., Jr, Cronin E.B., Hegde P.U., Kane M., Tavakoli B., Xu Y., Hart J., Tannenbaum S.H. Breast cancer: assessing response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy by using US-guided near-infrared tomography. Radiology. 2013;266(2):433–442. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12112415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saponaro C., Vagheggini A., Scarpi E., Centonze M., Catacchio I., Popescu O., Pastena M.I., Giotta F., Silvestris N., Mangia A. NHERF1 and tumor microenvironment: a new scene in invasive breast carcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018;37(1):96. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0766-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang J., Hou Y., Zhou M., Wen S., Zhou J., Xu L., Tang X., Du Y.E., Hu P., Liu M. Twist induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cell motility in breast cancer via ITGB1-FAK/ILK signaling axis and its associated downstream network. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016;71:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tejero R., Huang Y., Zou H., Friedel R. Cbmt-31. quiescent glioblastoma cells shift to an Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (Emt)-like gene program. Neuro. Oncol. 2018;20(6):vi39. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noy148.150. NovSupplEpub 2018 Nov 5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang J., Antin P., Berx G., Blanpain C., Brabletz T., Bronner M., Campbell K., Cano A., Casanova J., Christofori G., Dedhar S., Derynck R., Ford H.L., Fuxe J., García de Herreros A., Goodall G.J., Hadjantonakis A.K., Huang R.Y.J., Kalcheim C., Kalluri R., Kang Y., Khew-Goodall Y., Levine H., Liu J., Longmore G.D., Mani S.A., Massagué J., Mayor R., McClay D., Mostov K.E., Newgreen D.F., Nieto M.A., Puisieux A., Runyan R., Savagner P., Stanger B., Stemmler M.P., Takahashi Y., Takeichi M., Theveneau E., Thiery J.P., Thompson E.W., Weinberg R.A., Williams E.D., Xing J., Zhou B.P., Sheng G., E M.T.I.A. On behalf of the: guidelines and definitions for research on epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020;21(6):341–352. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0237-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.